1. Introduction

Plant protection products (PPP), more commonly known as pesticides, are a group of chemicals that are used in agriculture to protect crops from damage and illness by eliminating or repelling pests (Pathak et al., 2022).

It is estimated that arthropods alone are responsible for damaging around 18 – 26% of crops each year, equating to a global economic loss of 470 billion US dollars (Culliney, 2014). Therefore, pesticides have played a significant role in enhancing crop yield and producing good-quality food at affordable prices (Kim et al., 2017; Pathak et al., 2022). They have also been an essential tool in dealing with demographic growth as well as improving human life expectancy, livestock productivity and workforce efficiency (Tudi et al., 2021).

Pesticides are commonly grouped based on their target pest. These include insecticides, herbicides and fungicides amongst others. Additionally, pesticides can be classified according to their origin and chemical structure. Firstly, they are categorised as natural or synthetic (Sharma et al., 2020). Natural pesticides such as nicotine and pyrethrum are naturally occurring compounds produced by living organisms (Pathak et al., 2022). In contrast, synthetic pesticides are man-made and these are the ones most extensively used in agriculture (Sharma et al., 2020). Synthetic pesticides can be further divided into inorganic or organic. Inorganic pesticides include copper, sulfur and arsenic while organic ones include organochlorines, organophosphates, carbamates, pyrethroids and triazoles (Sharma et al., 2020; Tudi et al., 2021). Organochlorines are aliphatic or aromatic compounds containing chlorine atoms while organophosphates are ester compounds derived from phosphoric acid (Hassaan & El Nemr, 2020; Lizeth et al., 2022). Carbamates are ester compounds derived from dimethyl N-methyl carbamic acid (Hassaan & El Nemr, 2020). Pyrethroids are synthetic derivatives of pyrethrum (Dar & Kaushik, 2022), which are divided into two classes, class I pyrethroids are made up of the carboxylic ester cyclopropane and class II pyrethroids contain an additional cyano group (Dar & Kaushik, 2022). Finally, triazoles contain a five-membered, three-nitrogen-containing heterocyclic aromatic ring system (Matin et al., 2022).

Pesticides can be detrimental to both the environment and human health, particularly if they are misused or abused (Tudi et al., 2021). For example, the detrimental effects of organochlorines have been well-documented since the publication of Rachel Carson’s ‘Silent Spring’ in 1962 (Epstein, 2014). Due to their persistent and lipophilic characteristics, organochlorines can accumulate in the fatty tissue of animals and human bodies and remain stable in water, sediments, plants and soil (Taiwo, 2019).

For this reason, international and national organisations such as the European Union (EU) have implemented legislation concerning agricultural pesticide use and pesticide-detectable limits in food to safeguard human health and the environment. The approval of pesticides in the EU is overseen by the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) pesticide unit, which conducts a peer-reviewed, consumer risk assessment to evaluate the safety of each pesticide (Álvarez et al., 2023). EFSA assesses and establishes regulatory thresholds for pesticide residues in food and animal feed (referred to as maximum residue levels or MRLs) and evaluates whether pesticides (when used correctly) have a direct or indirect effect on human or animal health as well as on non-target organisms (EFSA, 2024).

Additionally, the European Commission provides a pesticide database that contains information on active substances that are either approved or not approved for use in agriculture (Commission, 2022). As of 2024, the EU pesticide database lists over 1481 pesticides, 440 of which are approved for use (Commission, 2022). Among these chemicals are glyphosate, propamocarb, deltamethrin and tebuconazole (

Table 1), with:

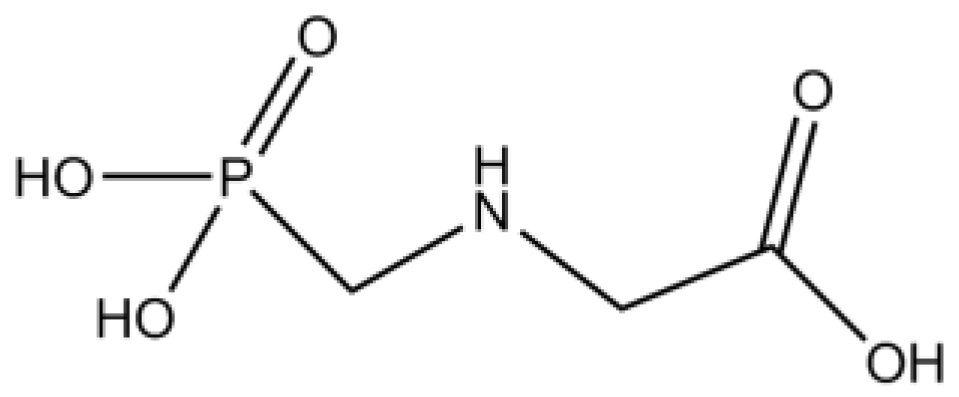

Glyphosate being an organophosphate, approved for use until 2033

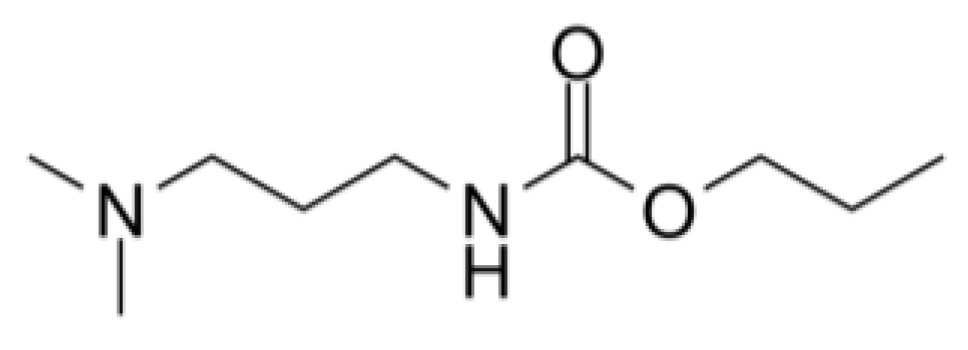

Propamocarb being a carbamate, approved for use until 2025

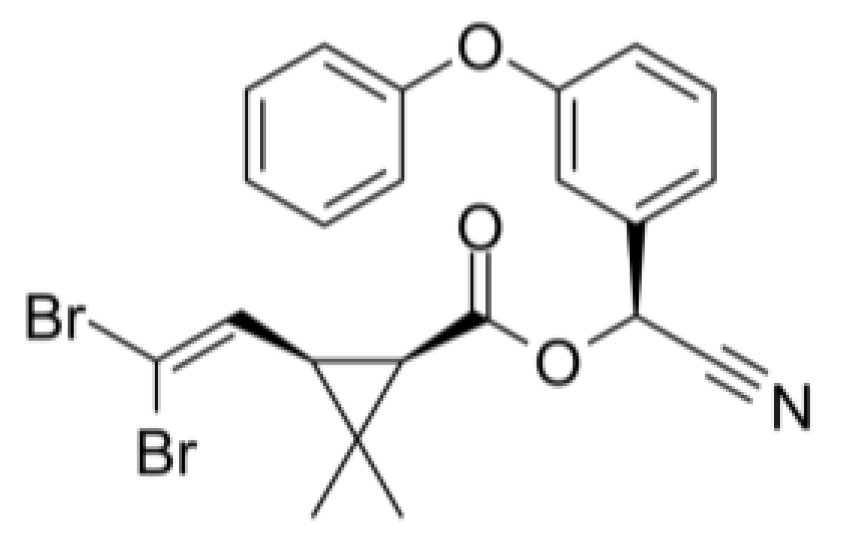

Deltamethrin being a pyrethroid, approved for use until 2026

Tebuconazole being a triazole, also approved for use until 2026.

Nevertheless, there remain uncertainties on human health especially when it comes to the effects of pesticides resulting from long-term, low-dose exposure of not only the parent pesticides but also their degradation products. Additionally, certain decisions on the approval of pesticides are based on limited human observational studies or experimental evidence (Álvarez et al., 2023; EFSA, 2014, 2015).

Therefore, the purpose of this manuscript is to provide an up-to-date, comprehensive review on the use, degradation, exposure and effects on gut health of these four EU-approved pesticides, glyphosate, propamocarb, deltamethrin and tebuconazole.

2. Pesticide Use in Agriculture and Their Modes of Action

Glyphosate is a popular, broad-spectrum organophosphate herbicide that controls a wide variety of monocotyledonous and dicotyledonous plants (Kanissery et al., 2019). It is generally used as a post-emergent herbicide and is applied to the foliar parts of the plant (Kanissery et al., 2019). Following plant uptake, it is then translocated to regions of active growth and inhibits the activity of 5-enol-pyruvyl-shikimate-3-phosphate synthase (EPSPS), an essential enzyme in the shikimic acid pathway (Kanissery et al. 2019). In this way, glyphosate prevents the biosynthesis of aromatic amino acids such as tyrosine, tryptophan and phenylalanine (Kanissery et al., 2019). This inhibits protein synthesis and secondary metabolites, causing the plant to die within 1 to 3 weeks.

Propamocarb is a systemic fungicide that is applied as a foliar or soil treatment as well as hydroponically (EFSA, 2006). It is used to treat and prevent early and late blights and is particularly used to control potato late blight (López-Ruiz et al., 2020). Propamocarb is thought to affect lipid biosynthesis and disrupt the cell membrane of fungal cells, though only a limited number of studies are available on the mode of action of propamocarb (Hu et al., 2007).

Similarly, tebuconazole is a broad-spectrum, systemic fungicide effective against soil-borne and foliar fungal disease in various crops (Muñoz-Leoz et al., 2011). Tebuconazole has been shown to inhibit sterol 14a-demethylase activity, a member of the cytochrome P450 superfamily, depleting ergosterol in fungal cell membranes (Lamb et al., 2001). Therefore, it affects cell membrane integrity and inhibits fungal growth and spore germination (Dong, 2024).

Deltamethrin controls a broad range of ectoparasites such as lice, ticks and flies (Lu et al., 2019). It has three chiral centers and may have up to eight potential stereoisomers, with only one of them having insecticidal activity (Aiello et al., 2021). Active deltamethrin is the S configuration at the alpha-benzyl carbon with a 1-R-cis configuration at the cyclopropane ring [1R, cis, alpha S] (Aiello et al., 2021). This isomer primarily targets voltage-gated sodium channels, increasing their opening time, and ultimately overstimulating the nervous system causing paralysis (Zhu et al., 2020). Voltage-gated calcium channels and voltage-gated chloride channels are also secondary targets of deltamethrin (Zhu et al., 2020). Thus, deltamethrin destabilises the cell membrane resting potential and dysregulates transepithelial transport (Zhu et al., 2020).

3. Transformation and Degradation of Pesticides

Once released into the environment, pesticides can be chemically transformed into other metabolites through abiotic or biotic means affecting their chemical properties, persistence and susceptibility to leaching (Muñoz-Leoz et al., 2011; Pimentel & Burgess, 2012). Pesticides are prone to photodegradation by UV rays, thermolysis, microbial degradation and metabolic transformation by plants or animals producing different chemical compounds.

For example, glyphosate is degraded to aminomethylphosphonic acid (AMPA) by bacteria such as Pseudomonas species (Gimsing et al., 2004; Kanissery et al., 2019). AMPA accounts for more than 90% of all reported glyphosate degradation products, which include sarcosine and glycine (Kanissery et al., 2019; Martins-Gomes et al., 2022). Like glyphosate, AMPA is very water soluble but is more persistent than glyphosate (Martins-Gomes et al., 2022). AMPA can be taken up by plants and can also be phytotoxic (Gomes et al., 2016, 2022). In aqueous conditions, glyphosate can also form the metabolite hexamethylphosphoramide (HMPA) and in glyphosate-tolerant crops, the metabolites N-acetyl glyphosate and N-acetyl AMPA have also been detected in addition to both glyphosate and AMPA (Álvarez et al., 2023).

Similarly, propamacarb is degraded into multiple products, with 2-hydroxypropamocarb and N-oxide propamocarb being two minor metabolites that were detected in cucumber, tomato, potato and spinach after foliar application of propamocarb (Bellisai et al., 2023; WHO, 2006). Other metabolites that were detected in soil, water and crops include propamocarb oxozoline and propamocarb n-desmethyl (López-Ruiz et al., 2019, 2020). In another study, Myresiotis et al. (2012) found that propamocarb can be degraded by the bacterial strain B. amyloliquefaciens IN937a and B. pumilus SE34, however, the identity of the degradation products was not investigated. Nonetheless, the parent compound remains the main residue (Bellisai et al., 2023).

Tebuconazole can be degraded into a range of metabolites. A total of 51 tebuconazole metabolites excluding conjugates have been identified in soil, water, crops and animals (Dong, 2024). The metabolites hydroxy-tebuconazole and tebuconazole-m-hydroxy were detected in small amounts in grapes (EFSA, 2014). In contrast, in wheat, peanut kernels and other rotational crops, tebuconazole was extensively metabolised to form triazole derivative metabolites (TDMs), which are common for several triazole fungicides. These include 1,2,4-triazole, triazole alanine, triazole lactic acid and triazole acetic acid (EFSA, 2014). In natural light-exposed photolysis studies, tebuconazole formed the metabolites, HWG 1608-lactone (5-Tert-butyl-5-(1,2,4-triazol-1-ylmethyl) oxolan-2-one), HWG 1608-pentanoic acid (4-Hydroxy-5,5-dimethyl-4-(1,2,4-triazol-1-ylmethyl) hexanoic acid) and 1,2,4-triazole (EFSA, 2014). Nevertheless, there is uncertainty whether these metabolites can be found in the environment (EFSA, 2014). Additionally, EFSA recognises unchanged tebuconazole to be the main compound (Brancato et al., 2018; EFSA, 2014).

Deltamethrin is also extensively degraded in the environment since several soil bacterial and fungal strains use pyrethroids as a carbon source (Singh et al., 2022). The degradation products of deltamethrin that are reported in the literature are 2-hydroxydeltamethrin, 4-hydroxydeltamethrin, α-hydroxy-3-phenoxybenzeneacetonitrile, 3-phenoxybenzaldehyde, 2-hydroxy-4-methoxybenzophenone, 3-phenoxybenzoic acid (3-PBA) and cis-decamethrinic acid (Aiello et al., 2021; Zhu et al., 2020). 3-PBA is one of the most frequently observed pyrethroid contamination indicators (Bragança et al., 2019; Cycon & Piotrowska-Seget, 2016). It is common for cypermethrin, cyhalothrin, permethrin and deltamethrin (Bragança et al., 2019). However, according to EFSA (2015), deltamethrin is the predominant residue detected in fruit, pulses, oilseeds and cereals accounting for up to 77% of total residues (EFSA, 2015). Finally, in animal studies, cis-(2,2-dibromovinyl)-2,2-dimethylcyclopropane-1-carboxylic acid (cis-DBCA) was identified as a selective metabolite of deltamethrin (Barr et al., 2010). Cis-DBCA together with trans-DBCA and 3-PBA is considered a useful exposure biomarker in human biomonitoring studies (Barr et al., 2010).

4. Human Exposure to Pesticides

Glyphosate, AMPA, deltamethrin, propamocarb and tebuconazole have been detected in drinking water, fruits, vegetables, legumes, honey, cereals, infant formula, alcoholic beverages and animal products (Bellisai et al., 2023; Muñoz et al., 2023b; Nijssen et al., 2024; Nougadère et al., 2020). Thus, the general public is exposed to low doses of these pesticides continuously through the environment (Solomon, 2016).

Human pesticide biomonitoring studies have detected pesticide biomarkers including their biotransformation products in urine, blood and breast milk (Connolly et al., 2020). For example, the Survey on PEstiCIde Mixtures in Europe (SPECIMEn) by Ottenbros et al. (2023b), analysed 2088 urine samples from adults and children from various European countries. The study detected 40 pesticide biomarkers in urine samples, including synthetic pyrethroids, propamocarb, and tebuconazole. The most frequently detected pesticides were acetamiprid (a neonicotinoid) and chlorpropham (a carbamate ester). Additionally, in most urine samples, at least two different pesticides were detected in the same sample with up to 10 co-occurring pesticides for some samples. Children typically had higher pesticide exposure due to their higher food intake per kg of body weight (b.w.). In another study, 37 pesticide metabolites were detected in urine samples from Dutch and Swiss populations, including acetamiprid, chlorpropham, and propamocarb (Ottenbros et al., 2023a).

Nijssen et al. (2024) studied the relationship between pesticide residues in food and their metabolites in urine collected within 24 hours of food intake. The study involved 35 adults in the Netherlands who provided food and urine samples. Food samples contained 5-21 pesticide residues, with deltamethrin (median of 22 ng/g up to a maximum concentration of 79 ng/g) being one of the most frequently detected. Propamocarb was detected in 26% of the samples (median of 6.1 up to 151 ng/g). The pyrethroid metabolites 3-PBA and 2,2-dichlorovinyl)-2,2-dimethylcyclopropane-1-carboxylic acid (DCCAA) were detected in low frequencies in food, while the specific deltamethrin metabolite, DBCA was not detected at all. Urine samples contained 65 metabolites corresponding to 28 pesticides, with up to 40 metabolites detected in a single sample. The most frequently detected parent pesticides in urine were acetamiprid, chlorpyrifos, propamocarb, synthetic pyrethroids, and tebuconazole. Additionally, DBCA was detected in 94% of urine samples in the range of 0.06–3.12 ng/mL, likely due to deltamethrin's widespread use in homes and as a veterinary medicine. Similarly, 3-PBA also showed a high detection frequency in urine (0.05–1.21 ng/mL). Some pesticides, such as tebuconazole, had higher detection frequencies in urine than in food, suggesting alternative exposure routes or prior dietary exposure (Nijssen et al., 2024).

Similarly, the European Human Biomonitoring Initiative (HBM4EU) study, analysed human exposure levels of pyrethroids and glyphosate (among other pesticides) in several European countries between 2000 and 2022. The results indicated a widespread exposure to these pesticides marked by the presence of 3-PBA (with a median of 0.23 - 0.24 ug/L), glyphosate (0.14– 7.36 ug/L) and AMPA (0.06 ug/L to 2.63 ug/L) in urine samples. The study observed that 3-PBA was more frequently detected in recent years, reflecting the increased use of pyrethroids in agriculture. Other metabolites of pyrethroid exposure that were detected included DCCAA and DBCA (Andersen et al., 2022).

In another investigation, 95.1% of urine samples from Portuguese children were positive for glyphosate (0.87 – 4.35 ug/L), with higher levels detected in children living near agricultural areas and consuming home-grown foods treated with herbicides (Ferreira et al., 2021). Likewise, Hyland et al. (2023) examined the effect of a conventional versus organic diet on 40 pregnant women in Idaho. They found that urinary glyphosate levels were detected in 76.9% of samples from women consuming a conventional diet (0.11 – 0.30 ug/L) and 71.8% (0.10 – 0.26 ug/L) from those consuming an organic diet. The small percentage decrease in glyphosate levels between the two groups indicates that the participants were exposed to glyphosate from other sources, or it highlights limitations in the research study such as participants not strictly adhering to the specific diet. Moreover, among participants living near fields, no difference in urinary glyphosate levels was detected between the two diet groups, indicating that other sources of exposure are more significant (Hyland et al., 2023).

Similarly, Grau et al. (2022) measured urinary glyphosate levels in 6795 French participants. Glyphosate was detected in 99.8% of urine samples (0.075 - 7.36 ng/ml) with higher levels detected between May and September. Male participants and younger individuals had higher average glyphosate levels than female participants and older participants. Smoking and consumption of tap and spring water, beer and fruit juice were associated with higher glyphosate levels, while significant consumption of organic food and filtered water were linked to lower levels (Grau et al., 2022).

One investigation aimed to assess exposure to glyphosate in bystanders (exposed to glyphosate through air, water and food) and in pesticide applicators using published studies up to 2014 and other unpublished reports (Solomon, 2016). According to the author, the general population is exposed to 0.000005 – 0.000063 mg/kg b.w./day while occupationally-exposed people are exposed to 0.000013 – 0.064 mg/kg b.w./day (Solomon, 2016).

Corcellas et al. (2012) analysed 56 human breast milk samples from Spain, Brazil, and Colombia for 13 pyrethroids and found a range of 1.45 and 24.2 ng/g. In Spain, deltamethrin was detected in the range of 0.09 to 0.71 ng/g (Corcellas et al., 2012). Then, Klimowska et al. (2020) evaluated long-term exposure to deltamethrin in 14 non-occupationally exposed, Polish volunteers by measuring metabolites in urine samples over one year. The metabolite 3-PBA was detected in 81% of samples (0.1 - 11.9 ng/ml), while cis-DBCA (0.1 - 14.5 ng/ml) was detected in 44.7% of samples. The study estimated that the median and maximum daily intake of deltamethrin was 20.4 ng/kg and 1400 ng/kg b.w., respectively, which is much lower than the acceptable daily (ADI) intake of 0.01 mg/kg b.w. (Bellisai et al., 2022; Klimowska et al., 2020).

Finally, Oerlemans et al. (2018) assessed tebuconazole exposure in young infants (3 – 29 months of age) in the Netherlands by measuring the metabolite TEB-OH in disposable diapers. Three out of seven diapers collected from seven children were positive for the metabolite (with a mean of 0.72 ± 0.36 ng/mL), and these were all collected from children who consumed solid food rather than breast milk or bottled milk. This suggests that tebuconazole or its metabolites are not likely to be released into human breast milk.

5. The Effect of Pesticides on Gut Health

It is known that pesticides can potentially harm human health with some degradation products being more toxic than their parent compound resulting in higher health risks. Although most pesticide residual concentrations have rarely crossed the threshold level in human biomonitoring studies, their effects on human health should still be investigated especially if there is long-term exposure. For this reason, EFSA performs consumer risk assessments concerning pesticide residues found in foods of plant and animal origin (EFSA, 2023). Other studies have also investigated the impact of pesticides on human health, some of which focus on pesticide doses concordant with the No Observed Adverse Effect Level (NOAEL) or the ADI.

Table 2 lists the NOAEL of glyphosate, propamocarb and deltamethrin according to EFSA. Specific NOAELs for tebuconazole could not be found.

Gastrointestinal (G.I.) or gut health, though not precisely defined in medicine, generally refers to the well-being of the entire G.I. tract, excluding organs like the liver and pancreas (Bischoff, 2011). The gut lining consists of three primary layers, collectively known as the gut barrier. These include the biological barrier (formed by intestinal microflora), the immune barrier (composed of gut-associated immune cells) and the mechanical barrier (made up of epithelial and endothelial cells) (Assimakopoulos et al., 2018). Effective digestion and nutrient absorption, the absence of G.I. diseases such as inflammatory disorders and cancer, normal composition and vitality of the gut microbiome, a robust mucosal immune system, and a properly functioning enteric nervous system, all compromise a healthy G.I. tract (Bischoff, 2011). The G.I. tract is essential not only for food processing and nutrient uptake but also for neurochemistry, immune regulation, and energy balance (Bischoff, 2011). Disruptions in the G.I. barrier can thus lead to various diseases, both within the gut and beyond, such as metabolic disorders (including obesity, type 2 diabetes (T2D) and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), autoimmune diseases, neurodevelopmental disorders, and cancer (Bischoff, 2011).

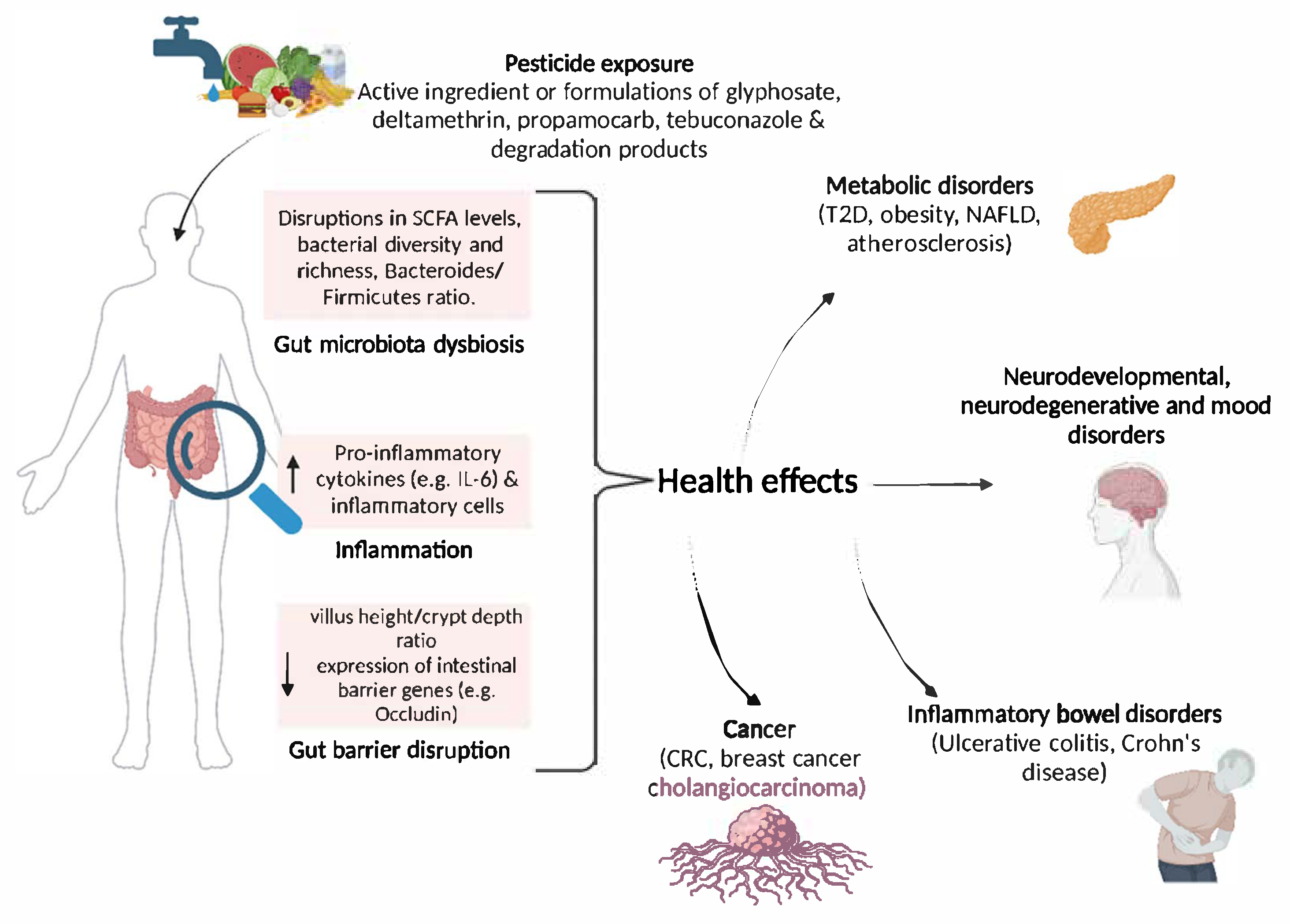

Recent research has explored the relationship between gut health and various diseases. Consequently, the adverse effects of environmental chemicals, such as pesticides, on human physiology may be mediated through the gut. Additionally, some studies have focused on the impact of pesticides on gut health, particularly examining their influence on the gut microbiome. This section will look at the documented effects of glyphosate, deltamethrin, propamocarb and tebuconazole on gut microbiota, gut inflammation, metabolism and cancer and gut-brain axis focusing on long-term, low-dose exposure effects. It will examine these effects on various models (animal, human epidemiological and in vitro studies) recorded in the last 10 years, to best inform potential health outcomes. These are also summarised in

Figure 1.

5.1. Gut Microbiota

The human gut microbiota is a community of more than a trillion microorganisms (bacteria, archaea and unicellular eukaryotes) that reside mostly in the ileum and colon (Li & Andrew, 2017). The gut microbiome refers to the collection of all genomes of the microbiota present in the gut (Das & Nair, 2019).

Despite significant inter-individual variability, a core gut microbiome shared by healthy adults has been identified, indicating its role in maintaining overall health (D’Argenio & Salvatore, 2015). The most common type of microorganisms that reside in the gut are mostly anaerobic bacteria with the main phyla present being Firmicutes (38.8%), Bacteroidetes (27.8%), Actinobacteria (8.2%) and Proteobacteria (2.1%) (Das & Nair, 2019; Li & Andrew, 2017; Shen et al., 2018). Beneficial gut microbiota among the Firmicutes include Lactobacillus and members of Clostridial Clusters IV and XIVa, including genera such as Roseburia and Butyricicoccus (Elson & Cong, 2012; Fu et al., 2019; Li et al., 2023a). These bacteria are important in the digestion of complex carbohydrates, synthesis of essential amino acids and vitamins, modulation of the efficacy of xenobiotics, protection against pathogens, fat storage and behaviour development (D’Argenio & Salvatore, 2015). The gut microbiota including both the Firmicutes and Bacteroides secrete short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) such as butyrate, acetate and propionate which affect the phenotype of enteric cells, act as tumour suppressors and modulate the enteric neuroendocrine and immune systems (Fu et al., 2019, Shen et al., 2018, Zafar & Saier, 2021).

Gut dysbiosis is the state where the composition of the microbiome is marked by reduced bacterial diversity, loss of specific populations, increased pathogenic organisms, and imbalances in SCFAs. (Das & Nair, 2019). This causes gut inflammation, dysregulation in energy balance and gut permeability which leads to health problems both within and beyond the gut.

Pesticides have been shown to induce gut dysbiosis, with the extent of impact dependent on the dosage and duration of exposure (

Table 3). Glyphosate's safety is attributed to the absence of the aromatic synthesis shikimate pathway in mammalian cells. However, this pathway is present in many commensal microorganisms, raising concerns about glyphosate's potential impact on the gut microbiota. Research indicates that 54% of gut bacterial species are sensitive to glyphosate (Puigbò et al., 2022). Bacteria with sensitive copies of the EPSPS enzyme include Faecalibacterium, Bifidobacterium, and Citrobacter (Puigbò et al., 2022). Unexpectedly, Bifidobacterium—a bacterium crucial not only for butyrate production but also for the synthesis and liberation of B vitamins and polyphenols and essential for immune homeostasis (among other roles)—was found to increase following Roundup exposure in rats (Mao et al., 2018). Conversely, both Bifidobacterium and Lactobacillus levels decreased following glyphosate exposure (Lehman et al., 2023; Mao et al., 2018). Additionally, Lehman et al. (2023) noted that SCFA production was lower in the glyphosate-exposed group than in the control group. However, the evidence in human studies is less clear. In a study of 65 UK twin pairs, glyphosate urinary levels were linked to increased species richness and certain fatty acid metabolites but did not significantly alter overall microbial composition or shikimate pathway gene abundance (Mesnage et al., 2022).

In another study, Nielsen et al. (2018) highlight the protective role of the diet in mitigating pesticide-induced dysbiosis. The researchers found that without supplemental aromatic amino acids, the minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) of Glyfonova® (a glyphosate formulation) in E.coli cells was 0.08 mg/mL. Adding phenylalanine, tyrosine, and tryptophan increased the MIC to 10-20 mg/mL. In vivo, 4-week-old male Sprague Dawley rats received water, glyphosate at 2.5 or 25 mg/kg b.w./day, or Glyfonova® at 25 mg/kg b.w./day. The Glyfonova® group showed higher bacterial diversity in the caecum and colon compared to controls. Additionally, no significant effects on alpha diversity or bacterial community composition were observed in the glyphosate-treated groups. The study concluded that sufficient levels of aromatic amino acids in the intestines likely mitigated glyphosate's effects (Nielsen et al., 2018).

Deltamethrin exposure in male mice increased the abundance of Bacteroides while decreasing Lactobacillus (Ma et al., 2023). It also reduced the diversity and richness of the gut microbiota (Ma et al., 2023). In contrast, the deltamethrin-exposed female mice showed higher bacterial richness and dose-dependent changes in gut microbiota composition (Li et al., 2023b). A loss of beneficial bacteria was also noted for propamocarb exposure in mice characterised by a loss of Roseburia and Butyricicoccus populations (Jin et al., 2021). Tebuconazole administration resulted in an increase in beneficial Lactobacilli populations in mice. However, one study also reported a rise in Helicobacter levels (Ku et al., 2023; Liu et al., 2021).

5.2. Inflammation

Pesticide-induced gut dysbiosis may cause gut inflammation and lead to IBD which includes ulcerative colitis (UC) and Crohn’s disease (CD). For example, Roundup exposure induced an increase in Veillonella levels in rats, a bacterium that is elevated in patients with CD (Mao et al., 2018; Pittayanon et al., 2020). Similarly, a reduction in Akkermansia, as observed in female mice exposed to Roundup, has been associated with an increased risk of UC (Pittayanon et al., 2020). Additionally, the reduction of SCFA production observed in glyphosate exposed mice likely affects inflammation (Lehman et al., 2023).

Several studies have specifically examined the impact of alterations in gut microbiota on gut inflammation. For instance, Lehman et al. (2023) observed that mice exposed to 10 μg/ml of glyphosate for 90 days exhibited an increase in CD4+ IL17A+ cells (Th17) in the colonic lamina propria, elevated serum levels of Lipocalin-2, a marker of gut inflammation, and a higher faecal pH. The study by Tang et al. (2020) further illustrated that glyphosate exposure (50 & 500 mg/kg, 35 days) in rats, enhanced the gene expression of the proinflammatory cytokines interleukin (IL)-1β, IL-6 and tumour necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) in different segments of the small intestine. This was coupled with a decrease in villus height/crypt depth ratio, hence reducing the digestive and absorptive capacity of the intestines (Tang et al., 2020).

In a study involving female BALB/c mice, intragastric administration of deltamethrin at a dose of 0.2 mg/kg/day over 8 weeks led to a significant reduction of colon length and an increase in colon inflammation even after a 2-week withdrawal period (Ma et al., 2024). Furthermore, deltamethrin exposure induced cellular senescence in the colonic epithelial cells, through the activation of the p53 signalling pathway (Ma et al., 2024). Further investigations showed that mice with experimentally induced colitis exhibited an even greater reduction in colon length and increased inflammation upon deltamethrin exposure, suggesting that deltamethrin could aggravate conditions such as ulcerative colitis (Ma et al., 2024). Notably, quercetin—a flavonoid commonly found in fruits and vegetables—demonstrated significant potential in mitigating many of the adverse effects associated with deltamethrin, once again underscoring the protective role of dietary components, highlighting the need for a more holistic approach in evaluating the effects of pesticide exposure.

Ma et al. (2023) demonstrated that deltamethrin inhibits the expression of Peroxiredoxin 1 (PRDX1) while simultaneously promoting its phosphorylation in human colon adenocarcinoma cells (HCT-116 cells). PRDX1 is a key enzyme involved in the antioxidant response. This dual effect induces oxidative stress and apoptosis, thereby contributing to colon injury (Ma et al., 2023).

In the study by Meng et al. (2022), involving male ICR mice, the effects of low-dose (0.3 mg/L) and high-dose (3 mg/L) tebuconazole exposure over 12 weeks were investigated. The study revealed that both low-dose and high-dose tebuconazole exposure caused marked structural damage and inflammatory cell infiltration in colon tissue. Tebuconazole exposure significantly upregulated the gene expression of immune-inflammatory genes, including TNFα and IL-6 in both dosage groups. Concurrently, tebuconazole exposure significantly inhibited the expression of key intestinal barrier genes, such as Occludin, suggesting compromised barrier integrity. Furthermore, tebuconazole (3 mg/L) exacerbated the severity of experimentally induced colitis in the mice. This was evidenced by increased colonic structural damage, heightened infiltration of inflammatory cells, and significant alterations in the expression of genes associated with inflammation and intestinal barrier function. Moreover, horizontal caecal contents transfer from mice treated with a high dose of tebuconazole to recipient mice resulted in colonic inflammation and a compromised intestinal barrier, mirroring the inflammatory response observed in the high-dose tebuconazole treatment group, showing that tebuconazole promoted colonic inflammation in mice in a gut microbiota-dependent manner. In their study, Liu et al. (2021) investigated the effects of tebuconazole exposure on three-week-old male Kunming mice, administered at a dose of 1.35 mg/kg b.w./day for 13 weeks. The pesticide exposure led to the accumulation of lipopolysaccharides (LPS) produced by gut microbiota in the serum, triggering systemic inflammation. This was shown by a nearly 10-fold elevation in serum TNF-α levels, and increased levels of IL-6 and IL-1β. This inflammation compromised the intestinal barrier, further facilitating the translocation of LPS from the gut into the bloodstream. This compromised barrier function further exacerbated inflammation and was associated with subsequent metabolic disruptions (Liu et al., 2021).

Jin et al. (2021) investigated the effects of a 20 mg/L dose of propamocarb on male C57BL/6 J and Apolipoprotein E (ApoE) −/− mice fed either a control or high-fat diet over 24 weeks. Propamocarb exposure resulted in elevated levels of inflammatory genes, including IL-1β, TNF-α, Intercellular Adhesion Molecule 1 (ICAM-1), and vascular cell adhesion molecule 1 (VCAM-1), in the aortas of treated C57BL/6 J mice together with increased serum levels of IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF-α. Similarly, propamocarb exposure in ApoE−/− mice led to higher mRNA levels of inflammation-related genes in the aorta, with notable increases in serum inflammatory factors such as IL-1α, IL-1β, interferon gamma (IFN-γ), and TNF-α. Additionally, propamocarb significantly induced the expression of inflammatory pathway proteins cluster of differentiation (CD)36, NF-κB, VCAM-1, and ICAM-1 in the aortas of ApoE−/− mice. These findings indicate that propamocarb exacerbates aortic inflammation, accelerating atherosclerosis development in both wild-type and ApoE−/− mice (Jin et al., 2021).

5.3. Metabolic Disorders

Many studies have shown that dysbiosis of the gut bacteria, inflammation and gut barrier disruption can lead to metabolic disorders such as obesity, NAFLD and T2D (Li & Andrew, 2017). For example, a decrease in butyrate-producing bacteria, such as Roseburia intestinalis as seen with propamocarb exposure in male C57BL/6J mice, is associated with higher adiposity, insulin resistance, and inflammation, increasing the risk of developing obesity, T2D and cardiovascular disorders (Le Chatelier et al., 2013; Li & Andrew, 2017; Jin et al., 2021). Indeed, Jin et al., (2021) demonstrated that exposure to propamocarb resulted in significant elevations in serum total cholesterol, triglycerides, and low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol, while high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL) levels were reduced, particularly in wild-type mice fed a high-fat diet. Propamocarb also induced lipid accumulation in the liver and upregulated cholesterol synthesis-related genes, even in mice on a normal diet. In the high-fat diet model, propamocarb significantly increased the mRNA levels of genes involved in cholesterol transport in the ileum. Additionally, propamocarb exposure also led to the induction of three bacterial groups (Peptostreptococcaceae, Ruminococcaceae, and Clostridiales_VadinBB60_group) that are closely associated with atherosclerosis. In ApoE−/− mice, propamocarb exposure led to a pronounced increase in atherosclerotic plaque area, with more severe plaques observed in the aortic arch. Additionally, propamocarb exposure significantly elevated macrophage numbers and aggregation. These findings, coupled with the observed increase in inflammation, suggest that propamocarb exposure initiated early signs of atherosclerosis in wild-type mice across different dietary conditions and accelerated atherosclerosis progression in ApoE−/− mice which could be related to gut dysbiosis.

Similarly, Liu et al. (2021) noted a shift in the Firmicutes-to-Bacteroidetes ratio in tebuconazole-exposed mice, a microbial imbalance linked to metabolic disorders. The exposed mice exhibited impaired glucose regulation and the presence of lipid droplets in the liver. The study also observed increased serum levels of fatty acids, lysophosphatidylcholine (a pro-inflammatory factor involved in atherosclerosis), ceramide and phosphatidylethanolamine (both associated with cardiovascular disease and insulin resistance) alongside a decrease in phosphatidylcholine (known to reduce blood lipids) in the exposure groups. Notably, treatment with faecal microbiota transplantation (FMT) effectively restored insulin sensitivity and increased the production of beneficial gut metabolites such as butyrate (Liu et al., 2021).

The impact of tebuconazole and propamocarb on metabolic health extends beyond the gut. For example, Kwon et al. (2021) suggested a potential correlation between exposure to tebuconazole and NAFLD. In their study, HEPG2 liver cells exposed to different concentrations of tebuconazole (20, 40, and 80 µM) for 24 hours exhibited an increase in lipid accumulation. Furthermore, treatment with 40 and 80 μM of the fungicide resulted in dysregulated expression of genes and proteins important in lipid metabolism and export. Additionally, treatment of tebuconazole also caused a decrease in mitochondrial membrane potential causing mitochondrial dysfunction (Kwon et al., 2021). Similarly, Meng et al. (2022) found that exposure to tebuconazole caused significant changes in three metabolic pathways involved in glycolipid metabolism, amino acid metabolism and tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle.

Exposure to propamocarb at 0, 1, 3, and 10 mg/L for 10 weeks, induced bile acid metabolic disorder in C57BL/6J mice, characterised by decreased gene expression of enzymes involved in bile acid synthesis and transportation (Wu et al., 2018b). This resulted in an observed increase in total hepatic bile acids and serum bile acids especially in the mice treated with 10 mg/L of propamocarb (Wu et al., 2018b). Additionally, chronic propamocarb exposure in mice led to decreased hepatic triglycerides and lower mRNA levels of genes important in glycolysis such as pyruvate kinase, lipid synthesis including Sterol regulatory element-binding protein 1c (Srebp1c) and Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor (Ppar)-γ transcription factors and lipid transportation such as fatty acid transport protein 2 (Fatp2) resulting in reduced metabolic efficiency (Wu et al., 2018b). Likewise, the study by Zhang et al. (2019) on adult male zebrafish exposed to 100 and 1000 μg/L of propamocarb for 7 days revealed significant disruptions in glucose and lipid metabolism. The exposed fish showed decreased lipid accumulation, triglycerides, total cholesterol, pyruvate, and glucose levels. Key genes involved in glucose metabolism, such as hexokinase 1 and pyruvate kinase, and lipid synthesis and transport, including Ppar-α, diacylglycerol acyltransferase (Dgat), and fatty acid synthase (Fas) were downregulated. Furthermore, metabolomic analysis indicated changes in the TCA cycle, sugar fermentation, together with amino acid and nucleotide metabolism.

In human studies, the link between pesticide exposure and metabolic disorders has also been investigated. Qi et al. (2023) found a positive link between high urinary glyphosate and increased risk of diabetes in 2535 U.S. adult participants. Similarly, in 2492 U.S. and Colombian individuals, high urinary glyphosate levels were also positively linked with a higher risk of T2D (Li et al., 2023c). Further analysis revealed that glyphosate is negatively associated with levels of HDL cholesterol, potentially leading to metabolic disorders (Li et al., 2023c). In another study, high urinary AMPA and glyphosate residues in childhood were associated with increased markers of liver inflammation and a 50% greater risk of developing metabolic disorders in young adulthood (Eskenazi et al., 2023).

A metabolome-wide study of 2012 participants also found a positive association between deltamethrin and the risk of diabetes (Jia et al., 2023). Serum deltamethrin was positively linked to higher levels of phosphatidylcholine, lysophosphatidylcholine and phosphatidylethanolamines, all known to be associated with metabolic disorders (Jia et al., 2023). Similarly, associations between pyrethroid exposure and the prevalence of diabetes (both types 1 and 2) were investigated in 3906 U.S. participants. The study found that higher urinary 3-PBA concentrations are positively linked to an increased risk of diabetes (Park et al., 2019). Another study on 7896 U.S. participants concluded that high urinary 3-PBA levels were associated with higher odds of obesity in females but not in males, suggesting that deltamethrin may have endocrine disruption effects in females (Zuo et al., 2022). In contrast, a study on male C57BL/6J mice found that deltamethrin does not promote obesity or insulin resistance (Tsakiridis et al., 2023). Exposure to 0.01 mg/kg b.w./day for 16 weeks reduced fat mass, improved glucose tolerance and significantly increased physical activity in the mice (Tsakiridis et al., 2023). Thus, it seems that the relationship between deltamethrin and obesity is complex and can vary depending on sex and species.

5.4. Cancer

While a comprehensive examination of the mechanisms linking gut dysbiosis, inflammation, and metabolic disturbances to cancer is beyond the scope of this review, an overview of each can effectively highlight the pathways through which pesticide exposure may contribute directly or indirectly to carcinogenesis or cancer progression. It is important to note that further research is necessary to establish a definitive connection between pesticide exposure and cancer through these mechanisms.

Alterations in gut microbial composition can lead to inflammation, modulation of the tumour microenvironment, and the release of oncogenic N-nitroso compounds (Jiang et al., 2021; Mishra et al., 2024; Wu et al., 2024). The microbiota profiles of patients with gastric and colorectal cancer (CRC) differ significantly from those of healthy individuals. For example, Helicobacter pylori is often the predominant bacterial species found in the stomachs of many gastric and oesophageal cancer patients (Yu et al., 2017). An increase in this bacterial species was observed with tebuconazole exposure in mice (Ku et al., 2023). Similarly, an increased abundance of mucosal-associated bacteria, including Clostridium septicum, Bacteroides fragilis, Escherichia coli and Fusobacterium nucleatum has been shown to contribute to the pathogenesis of CRC (Flemer et al., 2017). Indeed, the overuse of antibiotics has been significantly associated with an increased risk of developing colorectal adenomas, further supporting the role of gut microbiota in cancer development (Cao et al., 2017).

Pesticides have been demonstrated to promote inflammatory processes and metabolic disturbances. Chronic inflammation is recognised as a significant risk factor for the development of CRC, particularly for patients with IBD (Ullman & Itzkowitz, 2011). Several mechanisms link inflammation to carcinogenesis, including increased oxidative stress which may produce mutations and DNA damage and the production of proinflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α and IL-6 (Rubin et al., 2012; Ullman & Itzkowitz, 2011). These cytokines contribute to the growth of neoplasia by activating signalling pathways that promote tumour cell proliferation and survival (Ullman & Itzkowitz, 2011). Metabolic disorders, such as obesity, are characterised by chronic inflammation, which places affected individuals at a heightened risk for cancer (Mendonca et al., 2015). Furthermore, hyperglycaemia, dyslipidaemia, hypercholesterolaemia and low levels of HDL have all been linked to an increased risk of CRC development and progression (Ulaganathan et al., 2018; van Duijnhoven et al., 2011; Vulcan et al., 2017; Zaytseva et al., 2021).

Xie et al. (2024) conducted an extensive literature review to investigate the relationship between pesticide exposure and the risk of developing CRC. The study aimed to evaluate the association between different modes of pesticide exposure— environmental or occupational—and various types of pesticides, such as fumigants, fungicides, herbicides, and insecticides. Due to the limited data on the link between environmental exposure and CRC, the research primarily focused on occupational exposure. The findings indicate that certain classes of pesticides, particularly herbicides and insecticides used in occupational settings, may increase the risk of colon or rectal cancer (Xie et al., 2024). Additionally, other researchers and regulatory bodies have specifically examined any cancer-causing properties of glyphosate, deltamethrin, propamocarb, and tebuconazole.

The carcinogenicity of glyphosate is controversial. EFSA does not consider glyphosate as a carcinogen stating that current epidemiological findings do not associate glyphosate exposure with cancer-related health effects (Álvarez et al., 2023). Similarly, Wang et al. (2022) did not find any plausible evidence that glyphosate exposure leads to increased cancer risk unless administered in high doses. However, in 2015 the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) considered glyphosate as “probably carcinogenic to humans” with “limited evidence of carcinogenicity in humans” but “sufficient evidence of carcinogenicity in experimental animals” (IARC, 2018). Additionally, IARC also concluded that there was strong evidence for genotoxicity both for glyphosate and its formulations (IARC, 2018). On the other hand, using a weight-of-evidence approach, Greim et al. (2015) evaluated fourteen carcinogenicity studies in rodents and found no evidence of carcinogenicity related to glyphosate exposure (Greim et al., 2015).

Since then, using the IARC carcinogenicity assessment criteria as described in Smith et al. (2016), Rana et al. (2023) conducted a systematic review of scientific data up to August 2021. The authors focused on understanding how glyphosate and its formulation might cause cancer providing evidence from various types of exposure (both acute and chronic) and exposure routes. Therefore, while this analysis may offer potential insights into the carcinogenic potential of the pesticide, it is challenging to analyse the impact of glyphosate exposure in real-world scenarios. The study concluded that glyphosate-based formulations were found to have a higher genotoxic effect than glyphosate. Enhanced inflammation was particularly noted for occupation, acute, sub-acute or sub-chronic glyphosate exposure. Additionally, the analysis found supporting evidence that glyphosate induces oxidative stress and epigenetic alterations (Rana et al., 2023).

Agostini et al. (2020) summarised several epidemiological studies that have reported a link between glyphosate exposure and cancer risk. This link was primarily found in individuals who use glyphosate occupationally or have close family members who work with pesticides (Agostini et al., 2020). Of note, AMPA was also associated with increased cancer risk (Agostini et al., 2020).

Karalexi et al. (2021), Navarrete-Meneses & Pérez-Vera. (2019), and van Maele-Fabry et al. (2019) highlight that several epidemiological studies suggest an association between maternal or childhood exposure to pyrethroids and congenital leukaemia, including acute lymphoblastic leukaemia (ALL) and acute myeloid leukaemia (AML) (Karalexi et al., 2021; Navarrete-Meneses & Pérez-Vera, 2019; van Maele-Fabry et al., 2019). However, no study has yet investigated if there is a specific link between deltamethrin exposure and childhood leukaemia or any other cancer type.

In agricultural workers, carbamates were linked with an increased risk of CNS tumours (Piel et al., 2019). In contrast, occupational tebuconazole exposure was associated with a decreased risk of prostate cancer in men (Juliette et al., 2023).

Several studies in various cancer cell lines have also examined the effect of pesticides in vitro to identify mechanisms through which pesticides may cause carcinogenesis or promote cancer progression. For instance, exposure to glyphosate at the ADI (0.5 ug/ml) in HEPG2 liver cancer cells for 24 hours decreased total antioxidant capacity in the cells with a statistically significant decrease in glutathione peroxidase activity (Kašuba et al., 2017). However, exposure to glyphosate did not influence the levels of reactive oxidative species (ROS) formation and decreased lipid peroxidation levels (Kašuba et al., 2017). This shows that while glyphosate may affect the cellular antioxidant defence system, it does not increase oxidative stress in the short term in liver cancer cells.

In another investigation, A172 glioblastoma cells were exposed to Roundup, glyphosate and AMPA at 0.5 mg/L for 6 hours (Bianco et al., 2023). Both glyphosate and Roundup treatments produced larger colony-forming units (CFUs), while AMPA exposure led to an increased number of CFUs. All three pesticides enhanced the MAPK and AKT pathways, induced DNA damage, cell cycle arrest and compromised the redox system, leading to increased ROS and reactive nitrogen species (kuRNS) levels (Bianco et al., 2023). However, since glyphosate is unlikely to cross the blood-brain barrier at typical exposure levels, it is improbable that glyphosate promotes glioblastoma progression in the general population (Martinez & Al-Ahmad, 2019; Winstone et al., 2022). Then again, the study's findings are specific to a 6-hour exposure period, and the effects of chronic exposure remain unknown.

Rana et al. (2023) also noted that the supporting evidence classifies glyphosate as an endocrine disruptor that can alter hormone signalling by disrupting aromatase activity. In turn, this leads to disruption in oestradiol levels, which can lead to diseases such as breast cancer (Rana et al., 2023). A study by Munoz et al. (2023b) investigated the effects of glyphosate on oestrogen receptor (ER) signalling and breast cancer cell proliferation. The researchers treated MCF-7 and T47D breast cancer cell lines with 1x10-3 M glyphosate for 1 hour and observed increased phosphorylation of ER-α at Ser118 and Ser104/106. Further analysis revealed that glyphosate mimics the effects of oestrogen, inducing ER-α phosphorylation and activation, which in turn influences the expression of oestrogen-responsive genes. Additionally, treatment with 1x10-3 M and 1x10-5 M glyphosate for 120 hours significantly increased cell proliferation in MCF-7 and T47D cells, comparable to the effects of 17β-estradiol (E2) treatment. Similarly, glyphosate treatment at concentrations ranging from 10-13 to 10-7 M over 48 hours induced cell proliferation under oestrogen withdrawal conditions in the cholangiocarcinoma cell line, HuCCA-1 (Sritana et al., 2018). This proliferative effect was specific to HuCCA-1 cells expressing ERα, distinguishing it from other cholangiocarcinoma cell lines lacking ERα expression. Mechanistic investigations highlighted glyphosate's involvement in non-genomic oestrogen signalling pathways, including the induction of Extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) and Vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 2 (VEGFR2) protein expressions, along with modulation of the Mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase (MEK) signalling pathway (Sritana et al., 2018).

Other groups report that although glyphosate may not be directly oncogenic, it can still influence cancer risk by affecting the epigenome, particularly by inducing DNA methylation changes and histone modifications (Rossetti et al., 2021). For example, in one study, treatment of a non-malignant human breast cell line (MCF-10A) with 10-11 M of glyphosate for 21 days caused a reduction in global DNA hypomethylation, which was linked to the Ten-Eleven Translocation Methylcytosine Dioxygenase 3 (TET3) pathway (Duforestel et al., 2019). This effect when coupled with the overexpression of miR-182-5p promoted mammary tumour formation in mice (Duforestel et al., 2019). Similarly, treatment with 0.5 – 100 uM of glyphosate for 24 hours significantly decreased global DNA methylation in human peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) (Woźniak et al., 2020). The authors also found a significant decrease in methylation at the promoter of P21 alongside a significant increase in methylation at the TP53 promoter across all doses. However, these effects on gene expression were only evident in cells exposed to the highest concentrations of glyphosate. Specifically, there was an upregulation of P21 gene expression alongside a downregulation of TP53 gene expression observed only in cells exposed to 100 uM of glyphosate (Woźniak et al., 2020). Considering the previous study, it remains unclear whether similar changes in gene expression would have occurred if cells were exposed to lower doses of glyphosate over an extended duration. A second study by Wozniak et al. (2021) investigated the expression of genes involved in epigenetic modification associated with DNA and histone regulation, which could influence gene expression patterns in PBMCs. The authors illustrated that incubation of PBMCs with glyphosate (0.5 – 100 uM) and AMPA (10 and 250 uM) for 24 hours caused a significant increase in the DNA methyltransferases DNMT1 and DNMT3A in cells treated with 100 uM of glyphosate. While not statistically significant, the authors also observed an increase in the protein methyltransferases EHMT1 in glyphosate-treated cells (0.5 and 10 uM) and EHMT2 in AMPA-treated cells (0.5 and 10 uM). Additionally, a significant increase in the histone deacetylase HDAC3 in glyphosate-treated cells across all concentrations and cells treated with 250 uM of AMPA was also noted (Woźniak et al., 2021). There is also evidence that glyphosate exposure can induce epigenetic changes in the germ line, which increase the risk of obesity, prostate, kidney and ovarian diseases in subsequent generations (Kubsad et al., 2019; Rossetti et al., 2021)

Deltamethrin has been investigated as an anti-cancer agent in various cancer cell lines (Kumar et al., 2015). Exposure to deltamethrin concentrations ranging from 0.01 to 1 µM for 18 hours resulted in a substantial reduction in the viability of Jurkat-J6 (T-lymphocyte) cells (Sharma et al., 2018). Furthermore, exposure to these concentrations for 3 hours caused notable oxidative stress and triggered apoptosis within 6 hours of treatment (Sharma et al., 2018). Similarly, Chi et al. (2014) showed that deltamethrin treatment (20 – 100 uM) for 24 hours decreases the viability of OC2 human oral cancer cells. This treatment (20 – 60 uM for 24 hours) also triggered apoptosis in a concentration-dependent manner. Further investigation revealed that while deltamethrin elevated intracellular calcium levels, its cytotoxic effects were mediated through apoptotic pathways independent of calcium signalling (Chi et al., 2014).

Likewise, the anti-cancer activity of tebuconazole in human cancer cells has also been documented. Othmene et al. (2021 & 2022) showed that tebuconazole treatment (20 – 120 uM for 24 hours) of the colon adenocarcinoma cell line HCT-116 decreases its viability in a concentration-dependent manner. Tebuconazole was shown to exert its cytotoxic effects through apoptosis, oxidative stress and an increase in endoplasmic reticulum stress (Othmène et al., 2021 & 2022). Tebuconazole was also found to decrease the viability of HEPG2 liver cancer cells with statistically significant results at 50 μM treatment for 24 or 48 h and 25 uM for 48 hours (Leite et al., 2024). A loss of mitochondrial membrane potential was attributed to the observed cytotoxicity (Leite et al., 2024).

5.5. The Gut-Brain Axis

The involvement of the gut microbiota in the host brain function has generated considerable interest in recent years (Lu et al., 2024). The microbial community communicates with the brain through quorum sensing or the release of active substances and secondary metabolites from nutrient digestion which include neurotransmitters, vitamins and SCFAs (Lu et al., 2024). These affect host nerve growth development and regulation and are thus also closely related to neurological diseases including mood, neurodevelopmental and neurodegenerative disorders (Ashique et al., 2024; Lu et al., 2024).

Some studies in

Table 3 further explored the impact of pesticide-induced gut microbiota changes, especially to neurological diseases like autism spectrum disorders (ASD). For instance, a reduction in Prevotella species in male pups has been correlated with elevated urinary homocysteine levels (Hu et al., 2021). Prevotella is known to synthesise folate, which is crucial for converting homocysteine into methionine or cysteine. A decrease in Prevotella leads to reduced folate production, resulting in increased homocysteine levels, both of which have been associated with ASD (Hu et al., 2021). In a systematic literature review, Argou-Cardozo and Zeidán-Chuliá (2018) investigated the potential interrelation between Clostridium bacteria colonization in the gut and ASD. The authors not only identified Clostridium bacteria as a possible etiological factor of ASD but also highlighted that glyphosate exposure is a significant predisposing factor linked to the increased presence of this bacterium, thus linking glyphosate exposure to the development of ASD.

Depression and anxiety are also linked to changes in the gut microbiome. Buchenauer et al. (2023) found that glyphosate exposure during gestation and weaning led to depression- and anxiety-like behaviours, as well as social deficits in female offspring. These behavioural changes were associated with impaired tryptophan metabolism and reduced serotonin synthesis due to alterations in the gut microbiota. Similarly, zebrafish with altered microbiomes exhibited higher SCFA levels, which may explain the observed elevated serotonin and dopamine levels in the brain, leading to altered anxiety and social behaviours (Bellot et al., 2024). Additionally, in deltamethrin-exposed mice, specific gut bacteria were linked to depressive behaviour, inflammation, and reduced serotonin levels. Faecal microbiota transplantation from these mice to pseudo-sterile mice replicated these depressive behaviours and inflammatory responses, underscoring the gut microbiota's role in deltamethrin-induced neurotoxicity (Li et al., 2023b).

Cognitive function impairments have also been linked to gut dysbiosis. Wu et al. (2023) hypothesised that these alterations impair synaptic and cognitive functions through the release of immune factors. Their study demonstrated that probiotic pretreatment significantly reduced the elevation of IL-1β and TNF-α in the blood, brain, and intestine caused by tebuconazole exposure. Probiotics also restored tebuconazole-attenuated brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) expression and prevented the reduction of synaptophysin (SYP), postsynaptic density protein 95 (PSD-95), and glutamate AMPA and NMDA receptor subunits, resulting in improved behavioural performance in tebuconazole-exposed mice compared to controls.

Research has shown that exposure to glyphosate, propamocarb, deltamethrin and tebuconazole leads to changes in the composition of gut microbiota, gut inflammation and gut barrier disruptions. This has several health effects within the gut such as in the case of inflammatory disorders and beyond including metabolic and neurodevelopmental disorders as well as cancer. Image created using Biorender.

6. Limitations and Considerations

The health impacts of pesticides, particularly under low-dose, chronic conditions, remain controversial. Study results vary according to species, sex, age, dosage, and formulation. The studies included herein are marked by several limitations.

First, the majority of the available data is obtained from animal models. The doses used here are at or just below the NOAEL, which are still considerably high and may not accurately reflect those encountered by humans, especially considering the urinary concentrations of pesticides observed in human biomonitoring studies. For example, Solomon (2016) argues that the general population's exposure to glyphosate is much lower than EFSA’s ADI of 0.5 mg/kg body weight and thus there is no considerable risk from glyphosate exposure when used normally in agriculture (Solomon, 2016).

Secondly, the physiology and biochemistry of animal models may not be identical to those in humans and therefore may not accurately represent pesticide-induced human health effects. For example, rats metabolise deltamethrin much more rapidly than humans, thus, the doses administered to rats are not directly comparable to those for humans (Pitzer et al., 2021). Moreover, pesticides administered to animals are typically dissolved in water, which may affect their solubility and bioavailability differently compared to when they are delivered with food. Additionally, models of the human microbiota, such as mice, are also dominated by the same two phyla, Firmicutes and Bacteroidetes (Turner, 2018). However, several genera specific to humans are absent in these models, making direct comparisons to human microbiota challenging (Turner, 2018). This challenge is further compounded by significant inter-individual differences in gut microbiota composition among humans, as well as variations within the same individuals over time (Turner, 2018). These factors can affect the reproducibility of such studies (Turner, 2018). Nonetheless, to account for diversity, this study utilised various animals at different developmental stages (Turner, 2018).

Finally, most human-relevant data come from epidemiological studies that investigated the link between pesticide exposure and human health. These are based on observational data and population-based statistics. Such studies must also be approached with caution. They suffer from several limitations including exposure and outcome measurement errors as well as selection and recall bias (Moser et al., 2022). Additionally, epidemiological data does not prove a cause-and-effect relationship (Moser et al., 2022).

7. Conclusions and Perspectives

This review commenced with an examination of the use, degradation, and human exposure to glyphosate, deltamethrin, propamocarb, and tebuconazole. It then transitioned to an analysis of the documented effects of these pesticides on gut health, specifically focusing on gut microbiota, inflammation, metabolism, cancer, and the gut-brain axis. The observed health effects differed depending on whether the formulation or the active ingredient was examined, particularly in the case of glyphosate. Although this review primarily aimed to focus on glyphosate exposure, studies involving its formulations were also included to provide a more comprehensive analysis.

The review underscores the interconnected nature of these health effects, particularly highlighting how gut microbiota dysbiosis can trigger a cascade of adverse outcomes across a spectrum of diseases and conditions, including IBD, metabolic disorders, cancer, and neurodevelopmental issues. Furthermore, these effects have the potential for transgenerational impact, illustrating the broader implications of pesticide exposure on long-term health. Several mechanistic insights into the observed health effects, beyond gut microbiota dysbiosis, include the induction of pro-inflammatory markers, oxidative stress, and cell death. Additional mechanisms involve the disruption of glucose and lipid homeostasis, promotion and progression of atherosclerotic plaques, alterations in metabolic pathways, modulation of oncogenic signalling pathways, and epigenetic modifications.

Several key areas for future research have been identified as being essential. Firstly, the extensive range of degradation products and metabolites of these pesticides, although not the major metabolites, may still result in low-level human exposure, necessitating further studies on their health effects. Long-term studies are required to evaluate the health effects of individual pesticides, including the potential risk of CRC in environmental exposure settings. Other areas for future work include the role of glyphosate in inducing oxidative stress in cancer cells, its chronic effects on the epigenome, and how it influences the expression of tumour suppressor genes. Further research should also explore the broader impacts of glyphosate on other epigenomic and epiproteomic aspects, including protein post-translational modifications such as phosphorylation and methylation since these have an impact on protein activation and gene regulation respectively. Insights into the effects of pesticides on human gut microbiota are also needed. Furthermore, future studies should focus on the complex interactions between pesticide-induced gut dysbiosis, inflammation, metabolism, and cancer, particularly G.I. cancers.

It is important to consider everything holistically, examining the interplay between diet, sex, age, health status and pesticide metabolism, exposure, and effects in humans. Finally, it is crucial to investigate the effects of low-dose, long-term exposure and the combined impacts of multiple pesticides to achieve a comprehensive risk assessment.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Kimberly Fenech and Byron Baron; writing—original draft preparation, Kimberly Fenech.; writing—review and editing, Kimberly Fenech; Byron Baron; visualization, Kimberly Fenech.; supervision, Byron Baron.; project administration, Byron Baron; funding acquisition, Kimberly Fenech. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research work disclosed in this publication is partially funded by the ENDEAVOUR II Scholarships Scheme. The project may be co-funded by the ESF+ 2021 – 2027.

Acknowledgments

During the preparation of this manuscript/study, the author(s) used [ChatGPT, 3.5] for the purposes of [grammar, language, manuscript structure]. The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| 3-PBA |

3-phenoxybenzoic acid |

| ADI |

Acceptable daily intake |

| ALL |

acute lymphoblastic leukaemia

|

| ALP |

Alkaline phosphatase |

| AML |

acute myeloid leukaemia

|

| AMPA |

aminomethylphosphonic acid |

| ApoE |

Apolipoprotein E |

| ASD |

Autism spectrum disorders |

| b.w. |

Body weight |

| BDNF |

brain-derived neurotrophic factor

|

| CD |

Crohn’s disease |

| CD |

Cluster of differentiation |

| CFU |

Colony forming unit |

| Cis-DBCA |

cis-(2,2-dibromovinyl)-2,2-dimethylcyclopropane-1-carboxylic acid |

| DCCAA |

2,2-dichlorovinyl)-2,2-dimethylcyclopropane-1-carboxylic acid |

| Dgat |

diacylglycerol acyltransferase |

| DNMT1 |

DNA methyltransferase 1 |

| DNMT3a |

DNA methyltransferase 3a |

| EFSA |

European Food Safety Authority |

| EHMT1 |

Euchromatic histone-lysine N-methyltransferase 1 |

| EHMT2 |

Euchromatic histone-lysine N-methyltransferase 2 |

| EPSPS |

5-enol-pyruvyl-shikimate-3-phosphate synthase |

| ER |

Oestrogen receptor |

| ERK |

Extracellular signal-regulated kinase

|

| EU |

European Union

|

| Fas |

Fatty acid synthase |

| Fatp2 |

fatty acid transport protein 2 |

| FMT |

Faecal microbiota transplantation |

| G.I. |

Gastrointestinal |

| HDL |

High density lipoprotein |

| HMPA |

hexamethylphosphoramide |

| IARC |

International Agency for Research on Cancer

|

| IBD |

Inflammatory bowel disease |

| ICAM-1 |

Intercellular adhesion molecule 1 |

| IFN-γ |

Interferon gamma |

| IL |

Interleukin |

| LDL |

Low density lipoprotein |

| LPS |

lipopolysaccharide |

| MEK |

Mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase

|

| MIC |

Minimum inhibitory concentration |

| MRL |

Maximum residue level |

| NAFLD |

non-alcoholic fatty liver disease |

| NOAEL |

No Observed Adverse Effect Level |

| PBMC |

peripheral blood mononuclear cells

|

| Ppar |

Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor |

| PPP |

Plant protection products |

| PRDX1 |

Peroxiredoxin 1 |

| PSD-95 |

postsynaptic density protein 95

|

| RNS |

Reactive nitrogen species |

| ROS |

Reactive oxygen species |

| SCFA |

short-chain fatty acids

|

| Srebp1c |

Sterol regulatory element-binding protein 1c |

| SYP |

synaptophysin

|

| T2D |

Type 2 diabetes |

| TCA |

Tricarboxylic acid |

| TDM |

triazole derivative metabolite |

| TET3 |

Ten-Eleven Translocation Methylcytosine Dioxygenase 3

|

| TNF- α |

Tumour necrosis factor alpha |

| UC |

Ulcerative colitis |

| VCAM-1 |

vascular cell adhesion molecule 1 |

| VEGFR2 |

Vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 2

|

| 3-PBA |

3-phenoxybenzoic acid |

| ADI |

Acceptable daily intake |

| ALL |

acute lymphoblastic leukaemia |

| ALP |

Alkaline phosphatase |

References

- Agostini, L. P., Dettogni, R. S., dos Reis, R. S., Stur, E., dos Santos, E. V. W., Ventorim, D. P., Garcia, F. M., Cardoso, R. C., Graceli, J. B., & Louro, I. D. (2020). Effects of glyphosate exposure on human health: Insights from epidemiological and in vitro studies. Science of The Total Environment, 705, 135808. [CrossRef]

- Aiello, F., Simons, M. G., van Velde, J. W., & Dani, P. (2021). New Insights into the Degradation Path of Deltamethrin. Molecules (Basel, Switzerland), 26(13), 3811. [CrossRef]

- Álvarez, F., Arena, M., Auteri, D., Binaglia, M., Castoldi, A. F., Chiusolo, A., Crivellente, F., Egsmose, M., Fait, G., Ferilli, F., Gouliarmou, V., Nogareda, L. H., Ippolito, A., Istace, F., Jarrah, S., Kardassi, D., Kienzler, A., Lanzoni, A., Lava, R., … Villamar-Bouza, L. (2023). Peer review of the pesticide risk assessment of the active substance glyphosate. EFSA Journal, 21(7), 08164. [CrossRef]

- Andersen, H. R., Rambaud, L., Riou, M., Buekers, J., Remy, S., Berman, T., & Govarts, E. (2022). Exposure levels of pyrethroids, chlorpyrifos and glyphosate in EU—an overview of human biomonitoring studies published since 2000. Toxics (Basel), 10(12), 789. [CrossRef]

- Argou-Cardozo, I., & Zeidán-Chuliá, F. (2018). Clostridium Bacteria and Autism Spectrum Conditions: A Systematic Review and Hypothetical Contribution of Environmental Glyphosate Levels. Medical Sciences, 6(2), 29. [CrossRef]

- Ashique, S., Mohanto, S., Ahmed, M. G., Mishra, N., Garg, A., Chellappan, D. K., Omara, T., Iqbal, S., & Kahwa, I. (2024). Gut-brain axis: A cutting-edge approach to target neurological disorders and potential synbiotic application. Heliyon, 10(13), e34092. [CrossRef]

- Assimakopoulos, S. F., Triantos, C., Maroulis, I., & Gogos, C. (2018). The Role of the Gut Barrier Function in Health and Disease. Gastroenterology Research, 11(4), 261–263. [CrossRef]

- Barr, D. B., Olsson, A. O., Wong, L.-Y., Udunka, S., Baker, S. E., Whitehead, R. D., Magsumbol, M. S., Williams, B. L., & Needham, L. L. (2010). Urinary Concentrations of Metabolites of Pyrethroid Insecticides in the General U.S. Population: National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 1999-2002. Environmental Health Perspectives, 118(6), 742–748. [CrossRef]

- Bellisai, G., Bernasconi, G., Brancato, A., Cabrera, L. C., Castellan, I., Ferreira, L., Giner, G., Greco, L., Jarrah, S., Leuschner, R., Magrans, J. O., Miron, I., Nave, S., Pedersen, R., Reich, H., Robinson, T., Ruocco, S., Santos, M., Scarlato, A. P., … Verani, A. (2022). Modification of the existing maximum residue level for deltamethrin in maize/corn. EFSA Journal, 20(7), 07446. [CrossRef]

- Bellisai, G., Bernasconi, G., Carrasco Cabrera, L., Castellan, I., del Aguila, M., Ferreira, L., Santonja, G. G., Greco, L., Jarrah, S., Leuschner, R., Perez, J. M., Miron, I., Nave, S., Pedersen, R., Reich, H., Ruocco, S., Santos, M., Scarlato, A. P., Theobald, A., … Verani, A. (2023). Modification of the existing maximum residue level for propamocarb in honey. EFSA Journal, 21(11), 08422. [CrossRef]

- Bellot, M., Carrillo, M. P., Bedrossiantz, J., Zheng, J., Mandal, R., Wishart, D. S., Gómez-Canela, C., Vila-Costa, M., Prats, E., Piña, B., & Raldúa, D. (2024). From dysbiosis to neuropathologies: Toxic effects of glyphosate in zebrafish. Ecotoxicology and Environmental Safety, 270, 115888. [CrossRef]

- Bianco, C. D., Ourique, F., dos Santos, D. C., Pedrosa, R. C., Kviecisnki, M. R., & Zamoner, A. (2023). Glyphosate-induced glioblastoma cell proliferation: Unraveling the interplay of oxidative, inflammatory, proliferative, and survival signaling pathways. Environmental Pollution, 338, 122695. [CrossRef]

- Bischoff, S. C. (2011). “Gut health”: a new objective in medicine? BMC Medicine, 9(1), 24. [CrossRef]

- Bragança, I., Lemos, P. C., Delerue-Matos, C., & Domingues, V. F. (2019). Pyrethroid pesticide metabolite, 3-PBA, in soils: method development and application to real agricultural soils. Environmental Science and Pollution Research International, 26(3), 2987–2997. [CrossRef]

- Brancato, A., Brocca, D., de Lentdecker, C., Ferreira, L., Greco, L., Jarrah, S., Kardassi, D., Leuschner, R., Lythgo, C., Medina, P., Miron, I., Molnar, T., Nougadere, A., Pedersen, R., Reich, H., Sacchi, A., Santos, M., Stanek, A., Sturma, J., … Villamar-Bouza, L. (2018). Modification of the existing maximum residue levels for tebuconazole in olives, rice, herbs and herbal infusions (dried). EFSA Journal, 16(6), 5257. [CrossRef]

- Buchenauer, L., Haange, S.-B., Bauer, M., Rolle-Kampczyk, U. E., Wagner, M., Stucke, J., Elter, E., Fink, B., Vass, M., von Bergen, M., Schulz, A., Zenclussen, A. C., Junge, K. M., Stangl, G. I., & Polte, T. (2023). Maternal exposure of mice to glyphosate induces depression- and anxiety-like behavior in the offspring via alterations of the gut-brain axis. Science of The Total Environment, 905, 167034. [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y., Wu, K., Mehta, R., Drew, D. A., Song, M., Lochhead, P., Nguyen, L. H., Izard, J., Fuchs, C. S., Garrett, W. S., Huttenhower, C., Ogino, S., Giovannucci, E. L., & Chan, A. T. (2017). Long-term use of antibiotics and risk of colorectal adenoma. Gut, gutjnl-2016-313413. [CrossRef]

- Chi, C.-C., Chou, C.-T., Liang, W.-Z., & Jan, C.-R. (2014). Effect of the pesticide, deltamethrin, on Ca 2+ signaling and apoptosis in OC2 human oral cancer cells. Drug and Chemical Toxicology, 37(1), 25–31. [CrossRef]

- Commission, E. (n.d.). Maximum Residue Levels. https://food.ec.europa.eu/plants/pesticides/maximum-residue-levels_en [Accessed August 2024].

- Commission, E. (2022). EU Pesticides Database. Https://Food.Ec.Europa.Eu/Plants/Pesticides/Eu-Pesticides-Database_en. https://food.ec.europa.eu/plants/pesticides/eu-pesticides-database_en.

- Connolly, A., Coggins, M. A., & Koch, H. M. (2020). Human biomonitoring of glyphosate exposures: State-of-the-art and future research challenges. Toxics (Basel), 8(3), 60. [CrossRef]

- Corcellas, C., Feo, M. L., Torres, J. P., Malm, O., Ocampo-Duque, W., Eljarrat, E., & Barceló, D. (2012). Pyrethroids in human breast milk: Occurrence and nursing daily intake estimation. Environment International, 47, 17–22. [CrossRef]

- Culliney, T. W. (2014). Crop Losses to Arthropods. In Integrated Pest Management (pp. 201–225). Springer Netherlands. [CrossRef]

- Cycon, M., & Piotrowska-Seget, Z. (2016). Pyrethroid-Degrading Microorganisms and Their Potential for the Bioremediation of Contaminated Soils: A Review. Frontiers in Microbiology, 7, 1463. [CrossRef]

- Dar, M. A., & Kaushik, G. (2022). Chapter 1 - Classification of pesticides and loss of crops due to creepy crawlers. In Pesticides in the Natural Environment (pp. 1–21). Elsevier Inc. [CrossRef]

- D’Argenio, V., & Salvatore, F. (2015). The role of the gut microbiome in the healthy adult status. Clinica Chimica Acta, 451, 97–102. [CrossRef]

- Das, B., & Nair, G. B. (2019). Homeostasis and dysbiosis of the gut microbiome in health and disease. Journal of Biosciences, 44(5), 117. [CrossRef]

- Dong, B. (2024). A comprehensive review on toxicological mechanisms and transformation products of tebuconazole: Insights on pesticide management. The Science of the Total Environment, 908, 168264. [CrossRef]

- Duforestel, M., Nadaradjane, A., Bougras-Cartron, G., Briand, J., Olivier, C., Frenel, J.-S., Vallette, F. M., Lelièvre, S. A., & Cartron, P.-F. (2019). Glyphosate Primes Mammary Cells for Tumorigenesis by Reprogramming the Epigenome in a TET3-Dependent Manner. Frontiers in Genetics, 10. [CrossRef]

- EFSA. (2006). Conclusion regarding the peer review of the pesticide risk assessment of the active substance propamocarb. EFSA Journal, 4(7), 78. [CrossRef]

- EFSA. (2009). Potential developmental neurotoxicity of deltamethrin - Scientific Opinion of the Panel on Plant Protection Products and their Residues (PPR). EFSA Journal, 7(1), 921. [CrossRef]

- EFSA. (2014). Conclusion on the peer review of the pesticide risk assessment of the active substance tebuconazole. EFSA Journal, 12(1), 3485. [CrossRef]

- EFSA. (2015). Review of the existing maximum residue levels for deltamethrin according to Article 12 of Regulation (EC) No 396/2005. EFSA Journal, 13(11), 4309. [CrossRef]

- EFSA. (2023). Pesticides. https://www.efsa.europa.eu/en/topics/topic/pesticides#:~:text=A%20major%20part%20of%20EFSA’s,focuses%20on%20these%20active%20substances.

- EFSA. (2024). Pesticides. https://www.efsa.europa.eu/en/topics/topic/pesticides[Accessed August 2024].

- Elson, C. O., & Cong, Y. (2012). Host-microbiota interactions in inflammatory bowel disease. Gut Microbes, 3(4), 332–344. [CrossRef]

- Epstein, L. (2014). Fifty years since Silent Spring. Annual Review of Phytopathology, 52, 377–402. [CrossRef]

- Eskenazi, B., Gunier, R. B., Rauch, S., Kogut, K., Perito, E. R., Mendez, X., Limbach, C., Holland, N., Bradman, A., Harley, K. G., Mills, P. J., & Mora, A. M. (2023). Association of Lifetime Exposure to Glyphosate and Aminomethylphosphonic Acid (AMPA) with Liver Inflammation and Metabolic Syndrome at Young Adulthood: Findings from the CHAMACOS Study. Environmental Health Perspectives, 131(3), 37001. [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, C., Duarte, S. C., Costa, E., Pereira, A. M. P. T., Silva, L. J. G., Almeida, A., Lino, C., & Pena, A. (2021). Urine biomonitoring of glyphosate in children: Exposure and risk assessment. Environmental Research, 198, 111294. [CrossRef]

- Flemer, B., Lynch, D. B., Brown, J. M. R., Jeffery, I. B., Ryan, F. J., Claesson, M. J., O’Riordain, M., Shanahan, F., & O’Toole, P. W. (2017). Tumour-associated and non-tumour-associated microbiota in colorectal cancer. Gut, 66(4), 633–643. [CrossRef]

- Fu, X., Liu, Z., Zhu, C., Mou, H., & Kong, Q. (2019). Nondigestible carbohydrates, butyrate, and butyrate-producing bacteria. Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition, 59(sup1), S130–S152. [CrossRef]