Submitted:

13 June 2025

Posted:

17 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

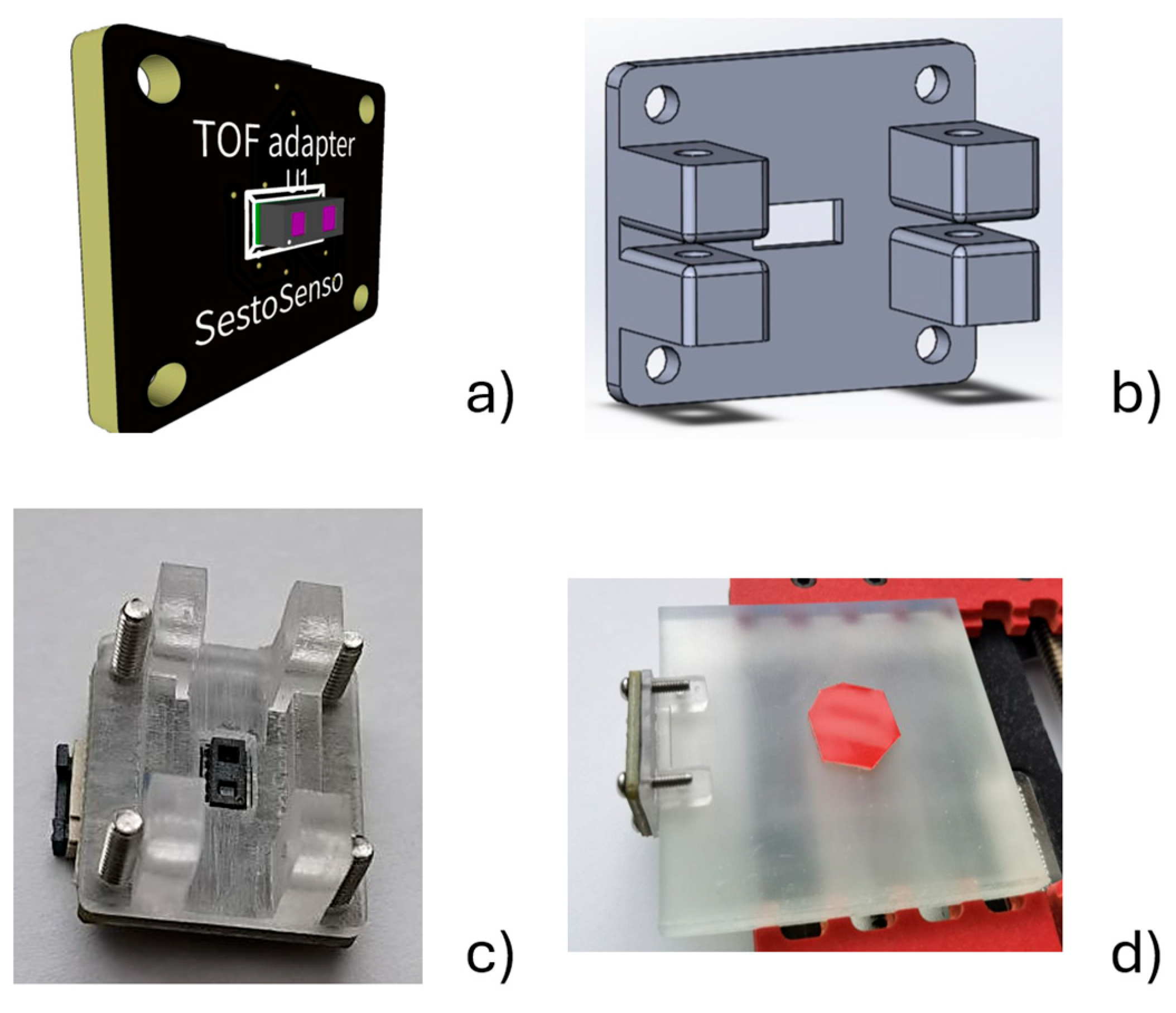

2.1. Sample Prepartion

2.2. Optical Characterazation

2.3. Measurements with ToF

3. Results and Discussion

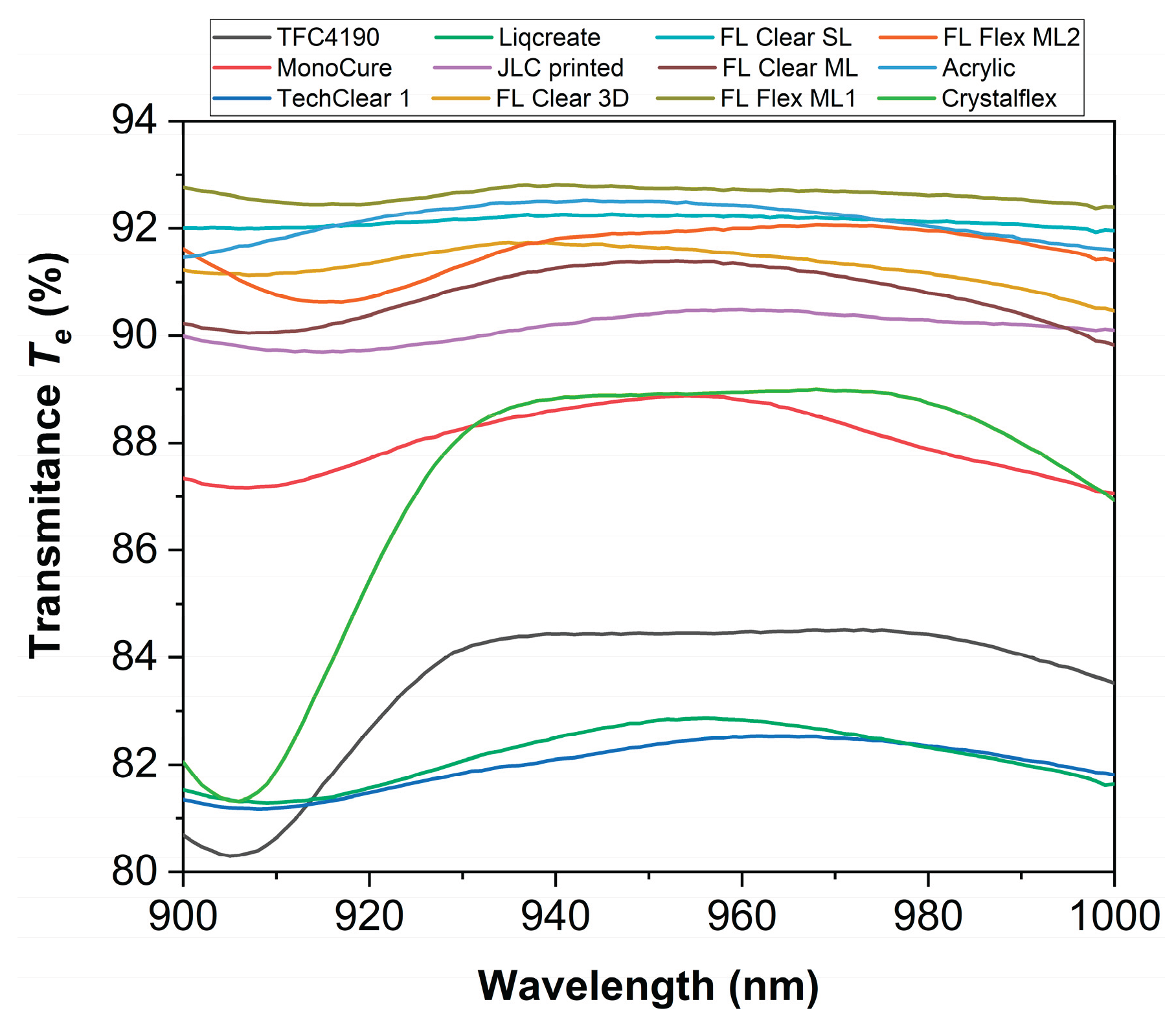

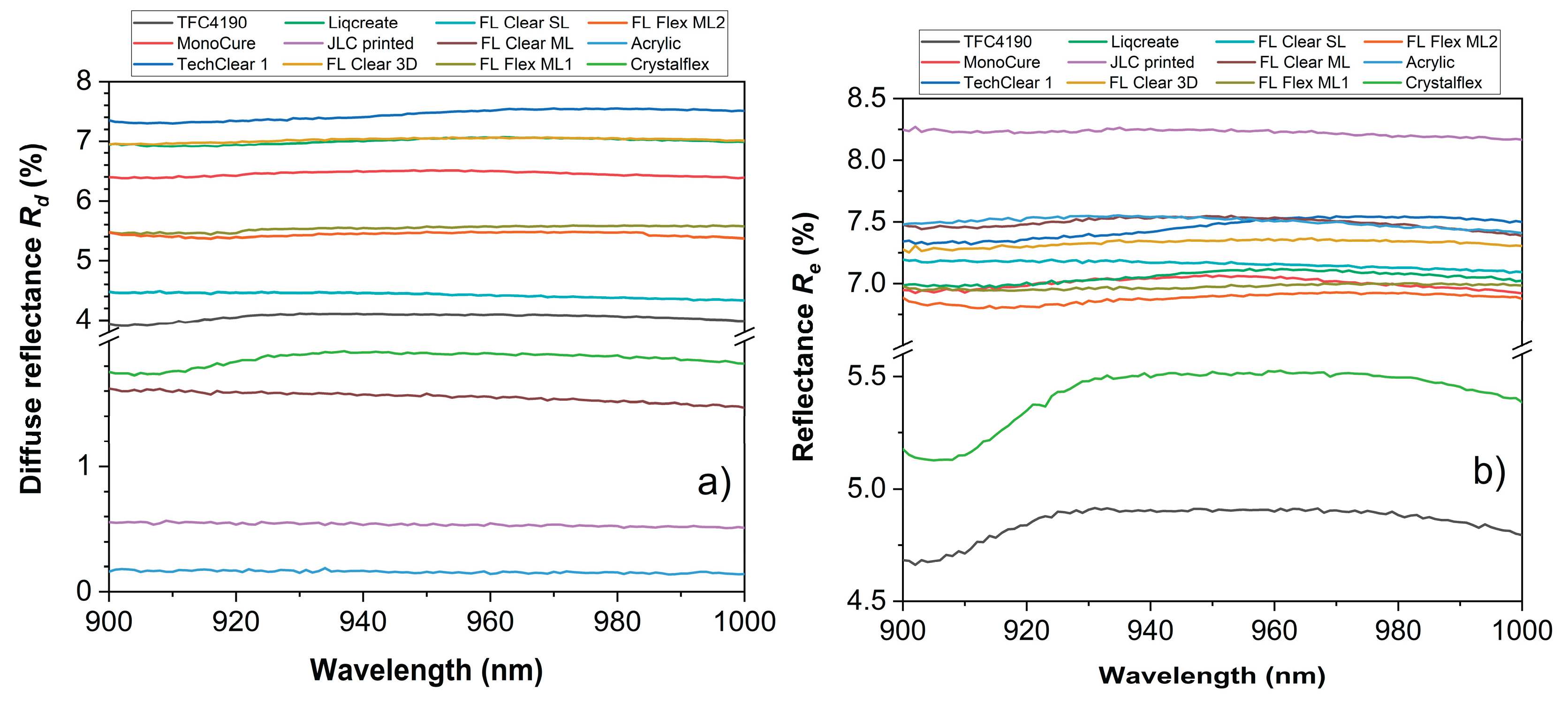

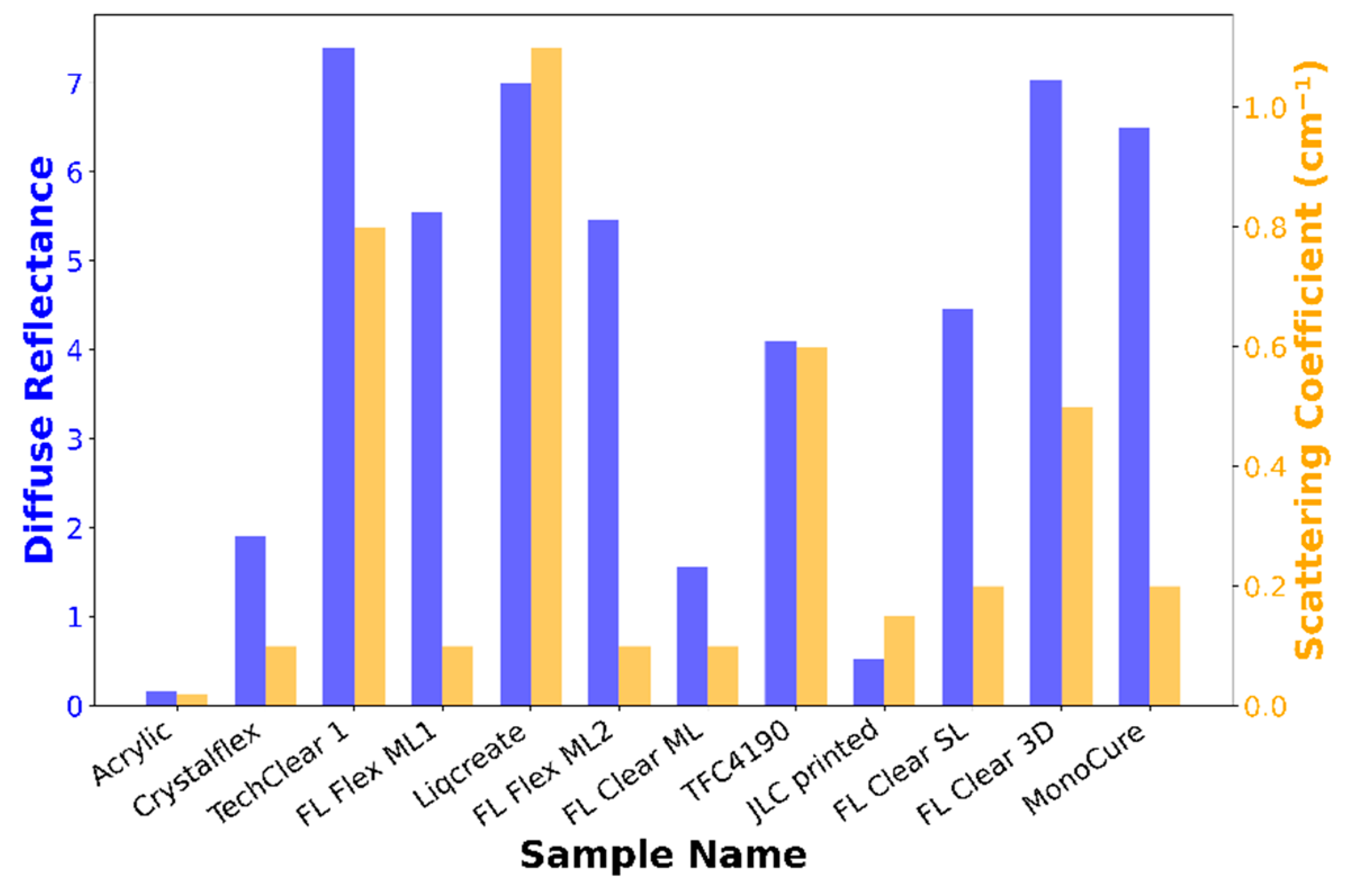

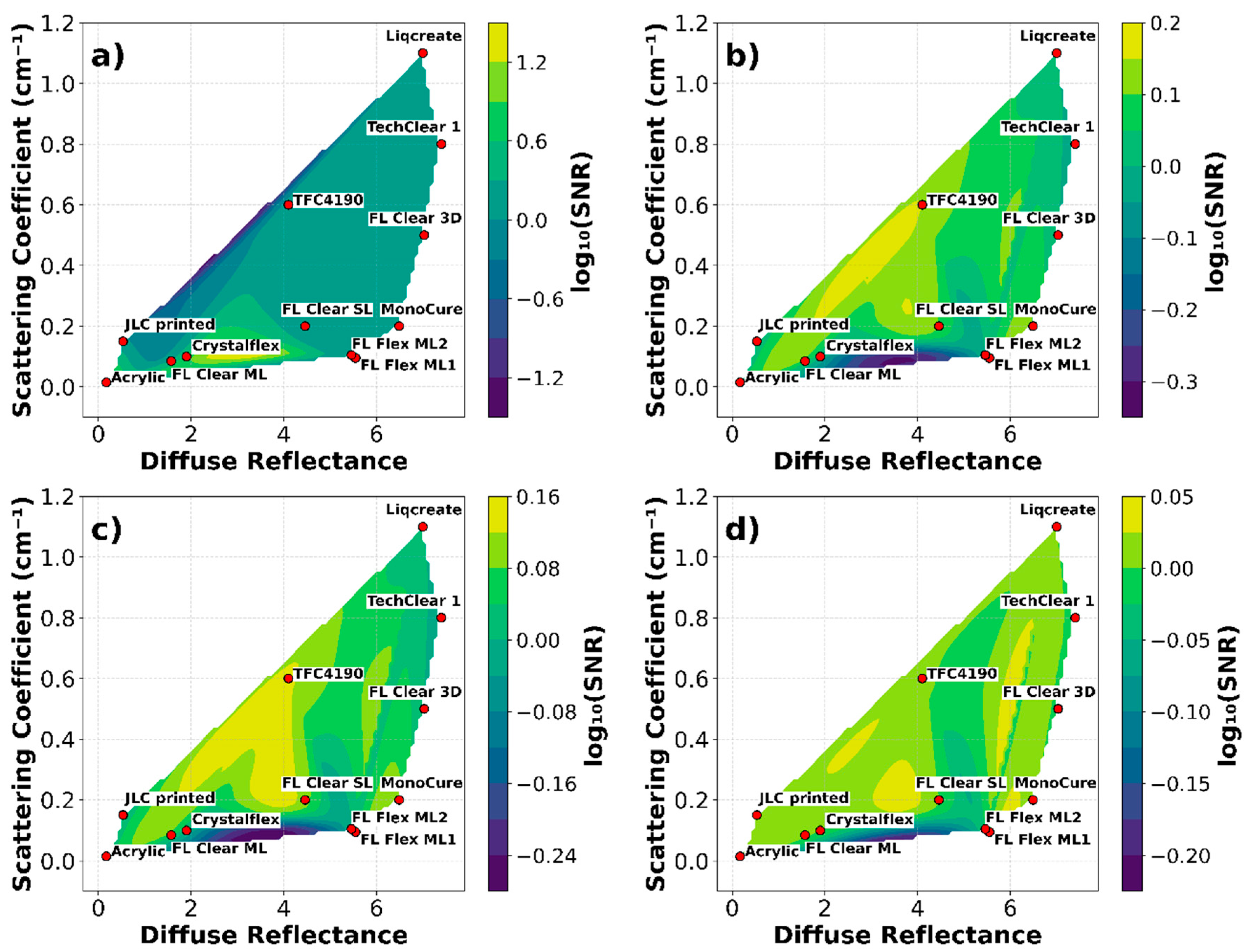

3.1. Optical Characterization

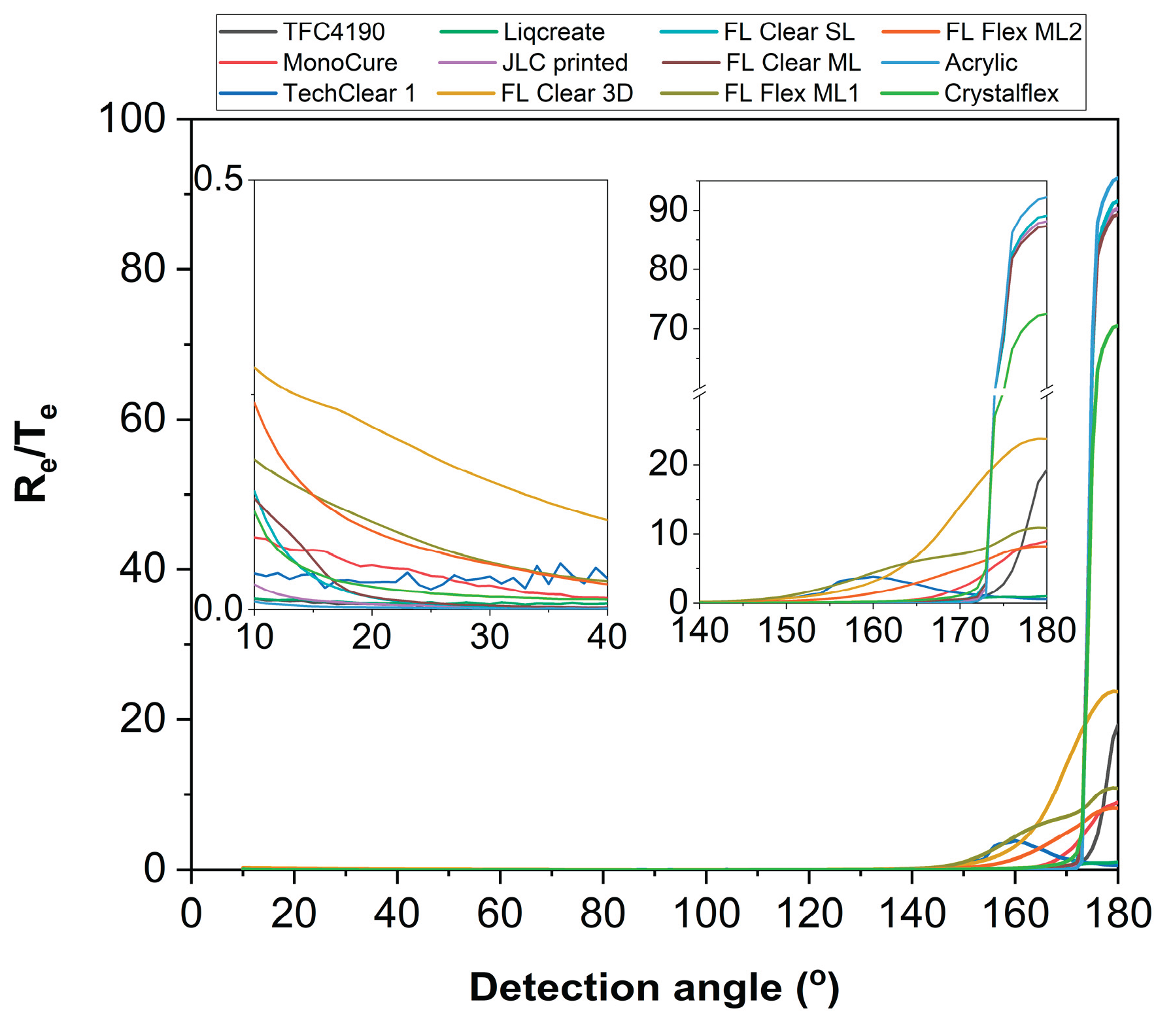

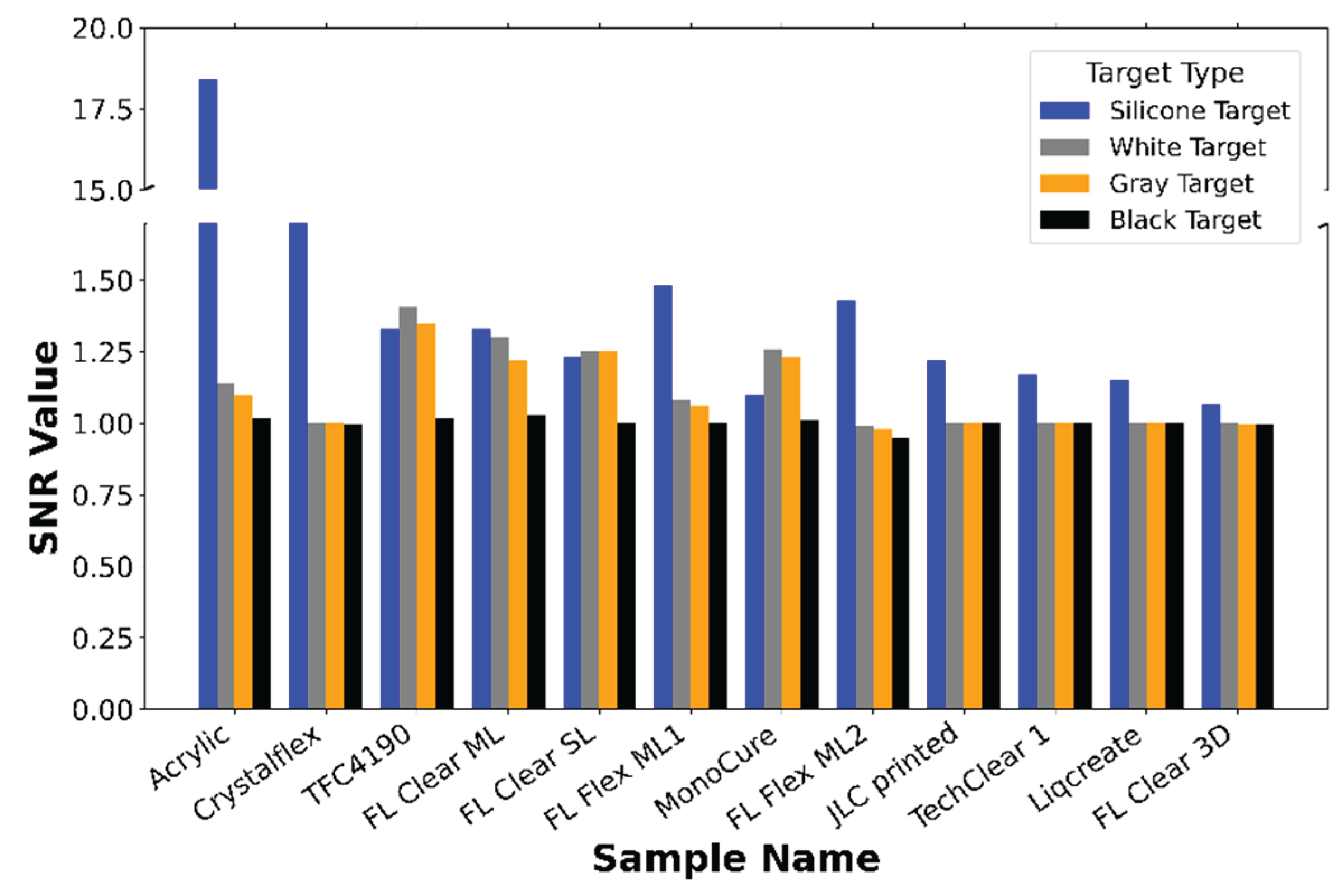

3.2. ToF Measurements

4. Conclusions

- Low-scattering, optically transparent materials (e.g., Acrylic, FL Clear ML) are optimal for FTIR-based contact sensing.

- High-scattering, moderately reflective materials (e.g., TechClear 1, Liqcreate) are more effective for near-proximity sensing.

- Black targets exhibit reduced detectability due to intrinsic optical limitations.

Supplementary Materials

Acknowledgements

Abbreviations

| CCD | Charge-coupled device |

| DRA | Diffuse reflectance accessory |

| FTIR | Frustrated total internal reflection |

| LiDAR | Light detection and ranging |

| MCML | Monte Carlo Multi-Layered |

| SE | Spectroscopic ellipsometry |

| ToF | Time-of-flight |

| TIR | Total internal reflection |

| UMA | Universal measurement accessory |

References

- Bacher, E.; Cartiel, S.; García-Pueyo, J.; Stopar, J.; Zore, A.; Kamnik, R.; Aulika, I.; Ogurcovs, A.; Grube, J.; Bundulis, A.; Butikova, J.; Kemere, M.; Munoz, A.; Laurenzis, M. OptoSkin: Novel LIDAR Touch Sensors for Detection of Touch and Pressure within Waveguides. IEEE Sens. J. 2024, 24, 33268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maekawa, H.; Tanie, K.; Komoriya, K. A Finger-Shaped Tactile Sensor Using an Optical Waveguide. In Proceedings of the IEEE Systems, Man and Cybernetics Conference, Le Touquet, France; 1993; Volume 5, pp. 403–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Begej, S. Planar and Finger-Shaped Optical Tactile Sensors for Robotic Applications. IEEE J. Robot. Autom. 2002, 4, 472–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heo, J.-S.; Kim, J.-Y.; Lee, J.-J. Tactile Sensors Using the Distributed Optical Fiber Sensors. In Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on Sensing Technology, Taipei, Taiwan; 2008; pp. 486–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ito, Y.; Kim, Y.; Nagai, C.; Obinata, G. Shape Sensing by Vision-Based Tactile Sensor for Dexterous Handling of Robot Hands. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Automation Science and Engineering, Toronto, ON, Canada; 2010; pp. 574–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lepora, N.F.; Ward-Cherrier, B. Superresolution with an Optical Tactile Sensor. In Proceedings of the IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS), Hamburg, Germany; 2015; pp. 2686–2691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.T.; Choi, H.; Shin, E.; et al. Graphene-Based Optical Waveguide Tactile Sensor for Dynamic Response. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 16118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, D.; Hu, J.; Li, Y.; Wang, S.; Liu, H. Polymer-Based Optical Waveguide Triaxial Tactile Sensing for 3-Dimensional Curved Shell. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 2022, 7, 3443–3450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Duong, L.; Ho, V.A. Large-Scale Vision-Based Tactile Sensing for Robot Links: Design, Modeling, and Evaluation. IEEE Trans. Robot. 2021, 37, 390–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, U.; Yuan, W. In-Hand Pose Estimation with Optical Tactile Sensor for Robotic Electronics Assembly. Tech. Rep., Robotics Institute, Carnegie Mellon University. 2022. https://uksangyoo.github.io/assets/pdf/Siemens_Electronics_Assembly.

- Wang, K.; Du, S.; Kong, J.; Zheng, M.; Li, S.; Liang, E.; Zhu, X. Self-Powered, Flexible, Transparent Tactile Sensor Integrating Sliding and Proximity Sensing. Materials 2025, 18, 322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H.; Ma, L.; Nie, Q.; Hu, X.; Li, X.; Min, R.; Wang, Z. Optical Tactile Sensor Based on a Flexible Optical Fiber Ring Resonator for Intelligent Braille Recognition. Opt. Express 2025, 33, 2512–2528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoffmann, V.; Paredes-Valles, F.; Cavinato, V. From Soft Materials to Controllers with NeuroTouch: A Neuromorphic Tactile Sensor for Real-Time Gesture Recognition. arXiv 2025. [CrossRef]

- Lyu, C.; Li, P.; Zhang, J.; Du, Y. Fiber Optic Sensors in Tactile Sensing: A Review. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2025, 74, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Chen, W.; Qian, H.; Wu, D.; Chen, R. ThinTact: Thin Vision-Based Tactile Sensor by Lensless Imaging. IEEE Trans. Robot. 2025, 41, 1139–1154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, A.; Wilson, A.; Man, T.; et al. Vision-Based Tactile Sensor Design Using Physically Based Rendering. Commun. Eng. 2025, 4, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Do, W.K.; Jurewicz, B.; Kennedy, M. DenseTact 2.0: Optical Tactile Sensor for Shape and Force Reconstruction. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), London, UK; 2023; pp. 12549–12555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Sheikh, S.S.; Hanana, S.M.; Al-Hosany, Y.; Soudan, B. Design and Implementation of an FTIR Camera-Based Multi-Touch Display. In Proceedings of the 5th IEEE GCC Conference & Exhibition, Kuwait; 2009; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, G. A Review of Technologies for Sensing Contact Location on the Surface of a Display. J. Soc. Inf. Disp. 2012, 20, 413–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wattanaparinton, R.; Takemura, K. Vision-Based Tactile Sensing Using Multiple Contact Images Generated by Re-Propagated Frustrated Total Internal Reflections. In Proceedings of the IEEE SMC, Prague, Czech Republic; 2022; pp. 962–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tompkins, C.G. Optical Methods of Imaging In-Plane and Normal Load Distributions Between Contacting Bodies. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Nottingham, Nottingham, UK, 2023. https://eprints.nottingham.ac.uk/id/eprint/73436.

- Fan, N.X.; Xiao, R. Reducing the Latency of Touch Tracking on Ad-Hoc Surfaces. Proc. ACM Hum.-Comput. Interact. 2022, 6, 489–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elegoo. SATURN 2. Available online: https://eu.elegoo.com/products/elegoo-saturn-2-8k-10-inches-mono-lcd-3d-printer (accessed on 2 June 2025).

- Formlabs. Form 3B+ vs. Form 2: Comparing Formlabs Dental Desktop 3D Printers. 2022. Available online: https://dental.formlabs.com/blog/form-3b-form-2-comparison/ (accessed on 2 June 2025).

- Foschum, F.; Bergmann, F.; Kienle, A. Precise Determination of the Optical Properties of Turbid Media Using an Optimized Integrating Sphere and Advanced Monte Carlo Simulations. Part 1: Theory. Appl. Opt. 2020, 59, 3203–3215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bergmann, F.; Foschum, F.; Zuber, R.; Kienle, A. Precise Determination of the Optical Properties of Turbid Media Using an Optimized Integrating Sphere and Advanced Monte Carlo Simulations. Part 2: Experiments. Appl. Opt. 2020, 59, 3216–3226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oregon Medical Laser Center. MCML - Monte Carlo Modeling of Light Transport in Multi-Layered Tissues. Available online: https://omlc.org/software/mc/mcml/index.html (accessed on 2 June 2025).

- Aulika, I.; Paulsone, P.; Laizane, E.; Butikova, J.; Vembris, A. Spatial Mapping of Optical Constants and Thickness Variations in ITO Films and SiO₂ Buffer Layers. Opt. Mater. X 2025, 26, 100408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sample | Rd, % | μs, cm-1 | g, cm-1 | Rs, % | Re, % | Ts, % | Te, % | n |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

TFC4190 Type 19 Sample 1 |

4.10 | 0* 0.6** |

0.99* 0.993** |

4.87 | 4.92 | 84.58 | 84.40 | 1.401 |

| MonoCure3D Pro Crystal Clear 2 | 6.49 | 0.2 | 0.931 | 6.96 | 7.05 | 87.88 | 88.60 | 1.483 |

|

TechClear 6123 Sample 1 (TechClear 1) |

7.40 | 0.8 | 0.874 | 7.32 | 7.4 | 82.23 | 82.1 | 1.537 |

| Liqcreate - Clear Impact 2 | 7.00 | 1.1 | 0.911 | 7.02 | 7.05 | 82.54 | 82.50 | 1.523 |

| JLC printed | 0.53 | 0.15 | 0.998 | 8.05 | 8.25 | 90.51 | 90.21 | 1.519 |

| FormLabs Clear – 3D printed (FL Clear 3D) | 7.03 | 0.5 | 0.940 | 7.63 | 7.34 | 91.01 | 91.72 | 1.497 |

| FormLabs Clear – Single layer (FL Clear SL) | 4.46 | 0.2 | 0.996 | 7.52 | 7.17 | 91.78 | 92.25 | 1.497 |

| FormLabs Clear – Multi layer (FL Clear ML) | 1.57 | 0.1 | 0.995 | 7.51 | 7.53 | 91.04 | 91.25 | 1.497 |

| FormLabs Flexible –Multi layer 1 (FL Flex ML1) | 5.55 | 0.1 | 0.934 | 7.28 | 6.96 | 92.42 | 92.80 | 1.482 |

| FormLabs Flexible –Multi layer 2 (FL Flex ML2) | 5.46 | 0.1 | 0.926 | 7.11 | 6.87 | 91.40 | 91.80 | 1.482 |

| Acrylic glass | 0.17 | 0.02 | 0.998 | 7.26 | 7.54 | 92.32 | 92.49 | 1.483 |

| Crystalflex | 1.9 | 0.1 | 0.995 | 5.00 | 5.50 | 88.06 | 88.20 | 1.398 |

| *For glossy area, **For opaque area | ||||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).