1. Introduction

Activation of the immune response following cryotherapy was first described by Shulman et al. in the 1960s, they observed that the transplantation of autologous frozen tumors resulted in the release of large amounts of antigens, triggering an immune reaction [

1]. Moreover, Soanes et al. reported the regression of distant metastases in patients with prostate cancer treated with cryoablation at the primary site [

2]. These phenomena are related to structural changes in proteins after freezing, resulting in the exposure of more immunogenic epitopes and enhancement of their immunogenicity [

3]. Although immune tolerance, which can be exploited by tumor cells to escape from the host immune system, is essential for preventing hyper-reactions to self-antigens, cryotherapy may provide a means to elicit a more robust immune response against tumors [

3].

The abscopal effect is a phenomenon in which radiotherapy causes regression of the targeted tumor and shrinks tumors at metastatic sites [

4]. This effect occurs through the activation of systemic antitumor immune responses triggered by radiation [

4]. The abscopal effect has been reported in several malignant tumors, such as malignant melanoma and non-small cell lung cancer [5-7], with various types of local treatment, including cryotherapy [

8,

9].

Cryotherapy for bone tumors is initiated as a reconstruction method for bone tumors of the extremities [

10,

11]. It has been experimentally proved that tumor cells in the tumor-bearing bone are completely killed by immersion in liquid nitrogen for 20 min [

12]. Currently, autografts of frozen bone are considered safe and effective and are widely utilized [

10,

11]. This technique was utilized for spinal metastatic or primary bone tumors; after total en bloc spondylectomy (TES), anterior spinal column reconstruction is performed with frozen tumor-containing bone autografts (second-generation TES) with the intention to activate cryo-immunity [

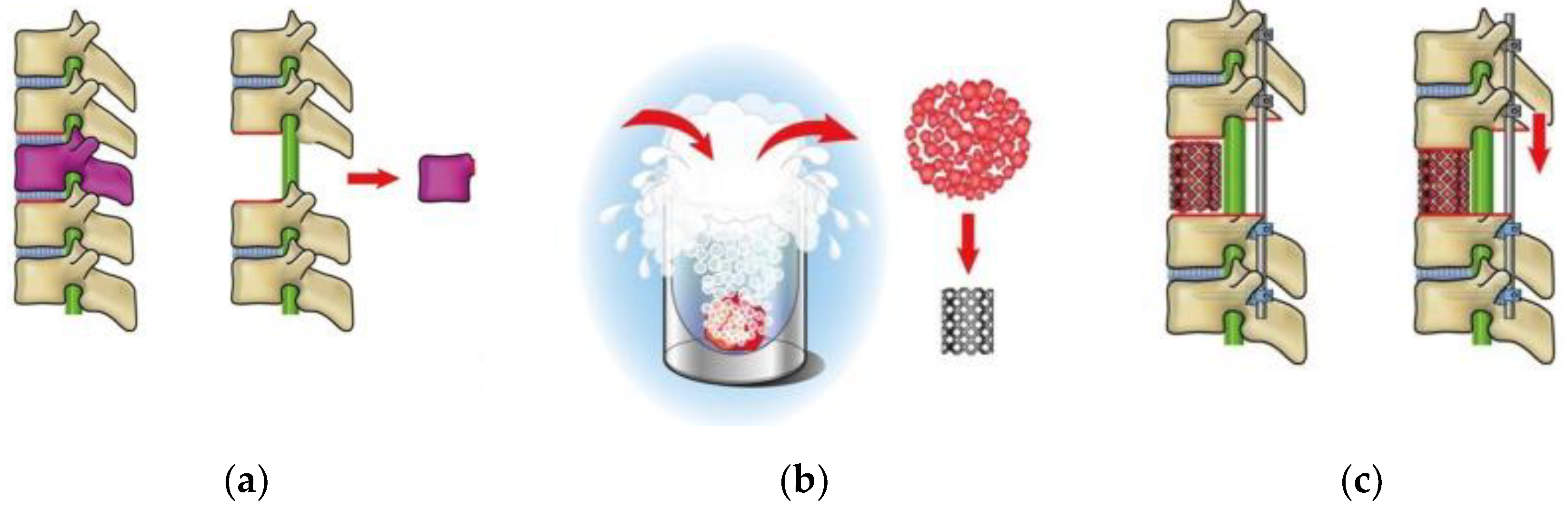

12] (

Figure 1). A case series analysis of patients who received second-generation TES reported that among 51 patients, 24 (47.1%) had no growth or emergence of metastatic lesions [

13]. Additionally, four patients, two each with breast cancer and thyroid cancer, experienced spontaneous regression of metastatic lesions or a decrease in tumor markers without chemotherapy [

13].

This prospective study investigated immune activation following second-generation TES, focusing on changes in the T-cell receptor (TCR) repertoire after surgery. In this case report, the methodology was described, and a representative case was presented as a preliminary result of an ongoing prospective study.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Patient

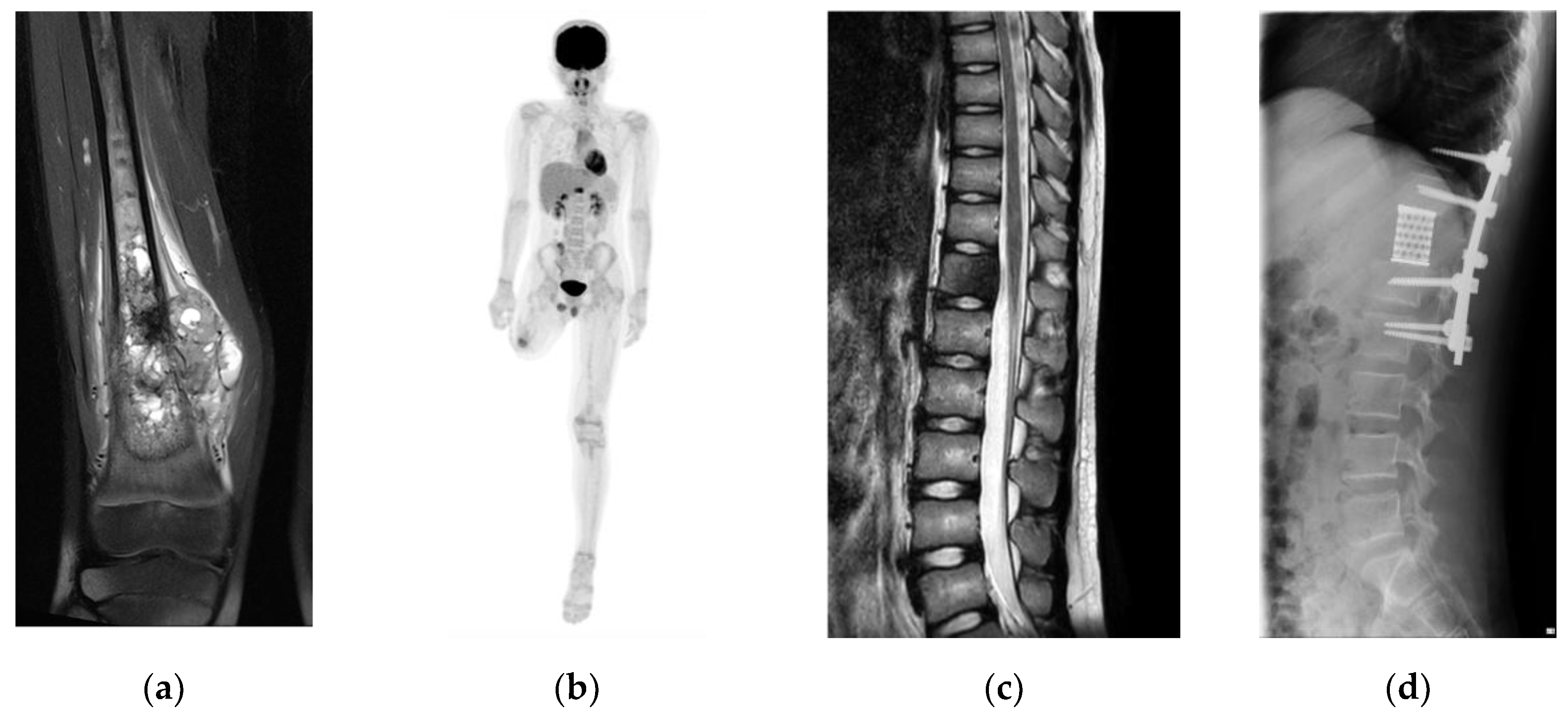

A 10-year-old boy was diagnosed with conventional osteosarcoma of the right distal femur. The patient underwent perioperative chemotherapy with tumor resection. Three years later, the patient underwent above-knee amputation due to recurrence at the surgical site. Seven months later, a solitary metastasis in the 12

th thoracic spine was pointed at 14-years-old. To achieve a disease-free status and prevent possible invasion of the spinal canal, second-generation TES was planned (

Figure 2).

2.2. Tumor Resection and Reconstruction

Second-generation TES was performed with the patient in the prone position under general anesthesia. A midline incision was made to expose the posterior surface of the thoracic vertebrae. The bases of the 12th ribs were cut bilaterally. The spinous process and inferior articular facet of the 11th thoracic vertebra were resected. Surgical thread wire saws were inserted from both sides of the 12th thoracic vertebral foramen, and the vertebral arch and transverse processes of the 12th thoracic vertebra were extracted. The 12th thoracic nerve roots were resected bilaterally. The anterior surface of the 12th thoracic vertebra was gently separated from the surrounding tissues. After inserting pedicle screws and setting-rods to stabilize the vertebral column (covering the 10–11th thoracic and 1–2nd lumbar vertebrae), the 12th thoracic vertebra was resected en bloc. The tumor-containing vertebral body was crushed into small pieces, frozen with liquid nitrogen (−196°C for 20 min), then packed into a cage and used for reconstruction as a vertebral body following spinal shortening. The total operative time was 322 min, and the total blood loss was 311 mL.

2.3. RNA Extraction and the Assessment of Integrity for the Sequence

RNA was extracted from whole blood using the PAXgene Blood RNA System (Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA) just before second-generation TES and 3 months postoperatively. The concentration and quality were tested using a NanoDrop 2000 spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). Agilent 2100 (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA) was used for the precise evaluation of RNA integrity, which was assessed based on the RNA Integrity Number value and flatness of the electropherogram baseline.

2.4. Immunome Sequencing Method

5’ rapid amplification of cDNA ends was performed for reverse transcription. The reverse transcription products were amplified using PCR and purified using DNA magnetic beads. The terminal repair was performed using End Prep Enzyme Mix (QIAGEN, Venro, Netherlands) with sequencing adapters at both ends. Subsequently, clean DNA beads were purified and amplified using the P5 and P7 primers. The PCR products were cleaned using beads, validated using Qsep100 (Bioptic, Taiwan, China), and quantified using Qubit3.0 Fluorometer (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA). Libraries with different indices were multiplexed and loaded onto an Illumina MiSeq/Novaseq instrument according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA). Sequencing was conducted using a 2 × 250 or 2 × 300 paired-end configuration, and image analysis and base calling were conducted using the MiSeq Control Software/Novaseq Control Software on the MiSeq/Novaseq instrument (Illumina).

2.5. Data Analysis

Raw FASTQ files were first subjected to a quality assessment (

Table A1). Adapters and bases with poor quality scores (Q-value <20) were removed using Cutadapt (V1.9.1) to generate clean data (trimmed data). FLASH (version 2.2.00) was used to merge paired-end reads. The merged sequences were blasted against the International ImMunoGeneTics (IMGT) reference database to identify the best match between germline V(D)J genes and sequences in the complementarity determining region 1 (CDR1), CDR2 and CDR3. V(D)J recombination is a unique mechanism of genetic recombination that occurs only in developing lymphocytes during the early stages of T- and B-cell maturation [

15,

16]. This mechanism results in many V(D)J combinations, engednring a highly diverse repertoire of immunoglobulins and T-cell receptor combinations. After obtaining the clone and CDR sequence information, customized scripts were written to perform the following statistical analyses: For diversity analysis, CDR3, an important region for antigen recognition[

17], resulting from V(D)J recombination, was analyzed using rank-abundance curves. Additionally, the richness[

18] of CDR3 types was analyzed using the abundance-based coverage estimator (ACE) [

19], Chao1 [

19], Shannon [

20], and Simpson indices [

21].

3. Results

3.1. VJ Gene Recombinations

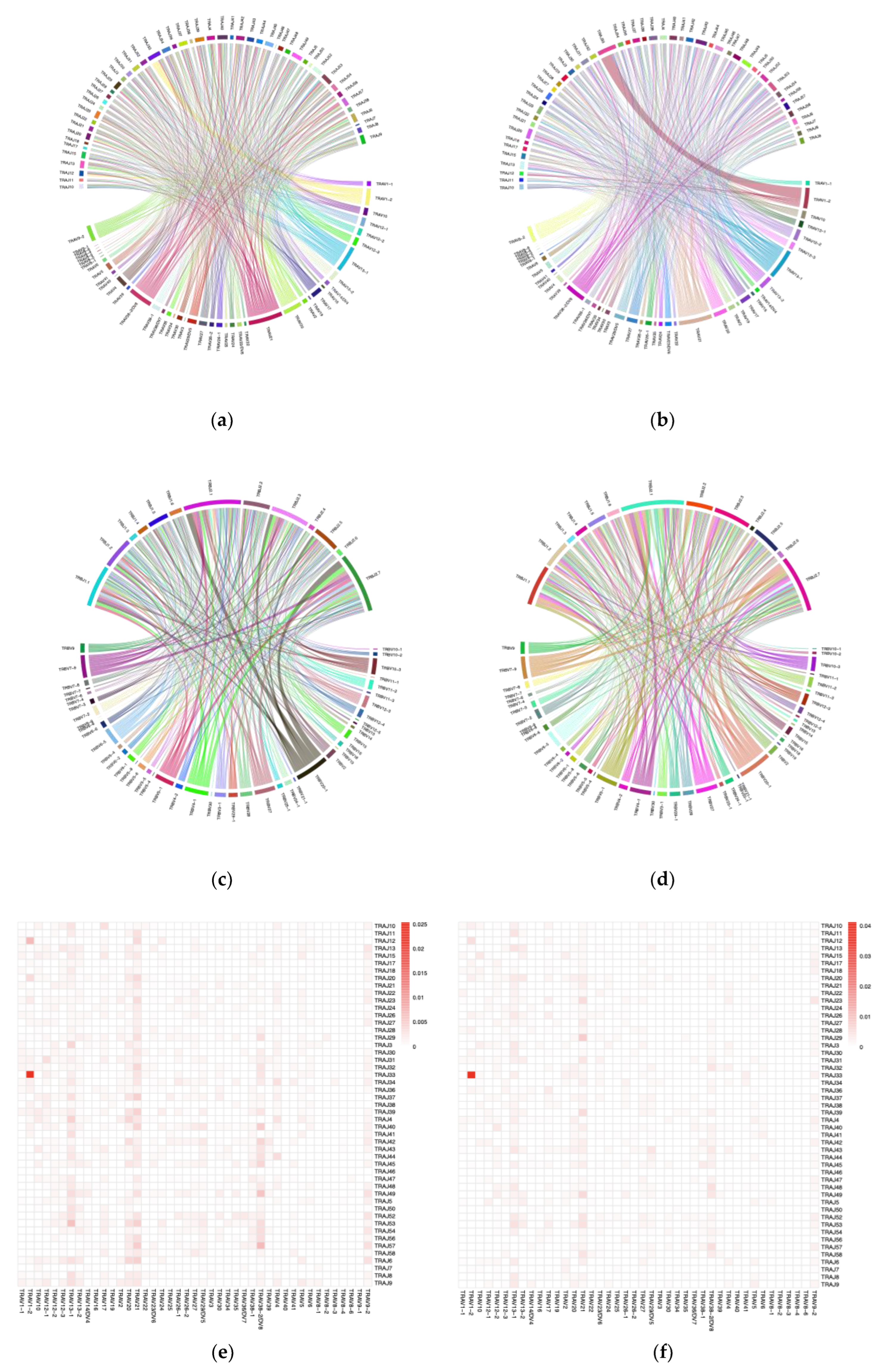

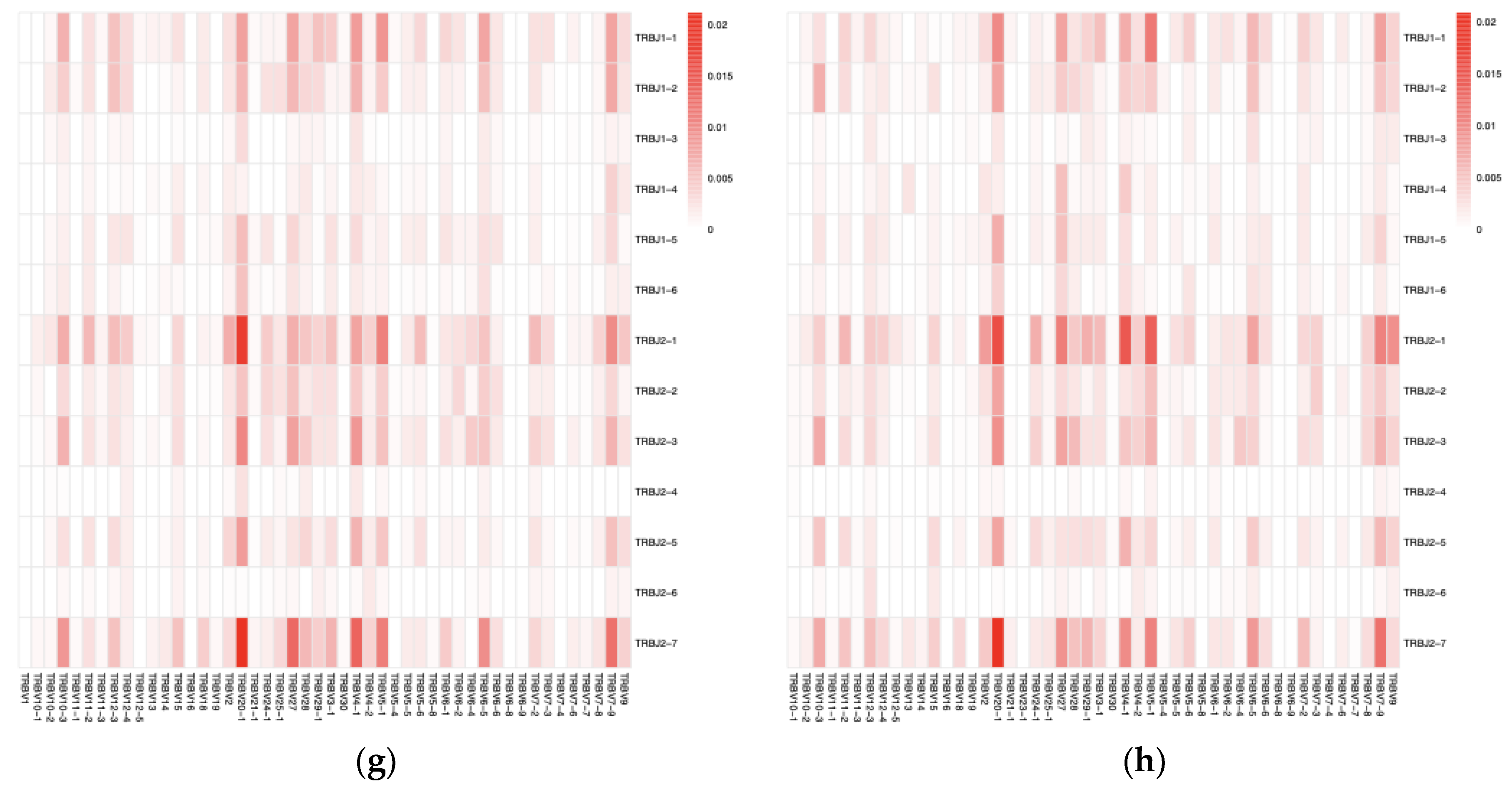

The merged sequences were BLASTed against the IMGT reference database to identify the best match for the germline VJ genes. The abundance of clones after mapping and clustering was calculated for each chain type at various time points. The Circo plots illustrate the interaction between TRAV–TRAJ or TRBV–TRBJ gene segments, where the connecting lines represent the pairing frequency of specific segments, with thicker lines indicating more common combinations (

Figure 3 a–d). The heatmaps revealed the dominant pairing genes between TRAV–TRAJ or TRBV–TRBJ, indicating clonal expansion and a favored V-J gene combination in the dataset (

Figure 3 e–h). Analysis of the full-length sequence and abundance of the identified VJ region in each sample is shown in

Supplemental Table S1.

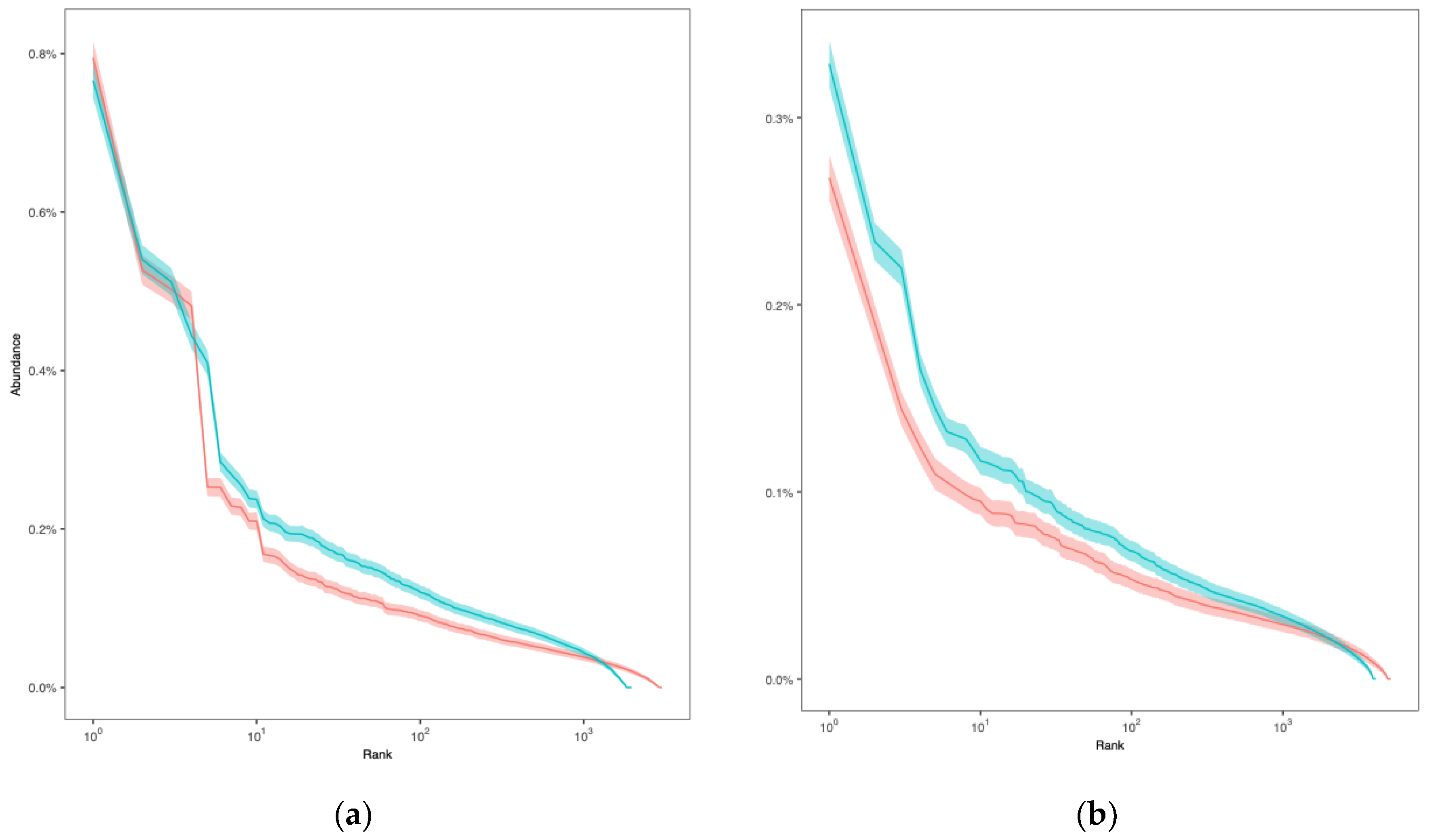

3.2. Diversity Analysis

The rank-abundance curves showed that the diversity of the CDR3 α chain in the preoperative period exhibited a higher level of repertoire diversity and richness compared to that during the postoperative period (

Figure 4a). Specifically, the preoperative CDR3 α chain had approximately 2,967 unique clonotypes, whereas the postoperative sample had approximately 1,865. The ACE and Chao1 indices, which estimate total unseen diversity, were also higher in the preoperative CDR3 α chain. The Shannon index was 11.085 for the preoperative CDR3 α chain, slightly exceeding the postoperative value, indicating a more balanced distribution of clones. Both samples demonstrated high Simpson indices (close to 1), implying that overall diversity remained high. Likewise, the diversity of the CDR3 β chain in the preoperative period exhibited a higher level of immune repertoire diversity compared to that during the postoperative period (

Figure 4b). The preoperative CDR3 β chain had approximately 5,070 unique clonotypes, higher than the 4,050 clonotypes in the postoperative sample. The ACE and Chao1 indices were also higher in the preoperative CDR3 β chain, suggesting that the preoperative repertoire was more extensive and included many rare clones. The Shannon index for the preoperative period (11.974) was slightly higher than that of the postoperative period (11.630), indicating a more even distribution of clones in the preoperative period. Both samples showed high Simpson indices (close to 1), indicating that diversity was high and no single clone dominated either repertoire (

Table 1).

3.3. Patient’s Outcome

The patient remained disease-free for 1 year following second-generation TES; however, a solitary metastasis was noted in the right lower lobe. The patient received a lobectomy and is currently disease-free (2 years after second-generation TES).

4. Discussion

This case report presents preliminary results from a prospective study of immunologic alterations following second-generation TES, focusing on the repertoire of TCRs. The findings demonstrated that the repertoires of the CDR3 regions of the TCR α and β chains decreased after surgery, suggesting that more selective clones may have emerged and influenced immune responses.

TCRs are transmembrane glycoprotein heterodimers mainly formed by the combination of α and β chains [

22]. The genes encoding the α (

TRA) and β (

TRB) chains consist of multiple non-continuous segments, including variable (V), diversity (D) segments, and joining (J) segments [

22], and TCRs acquire their diversity through V(D)J recombination [

22]. Diversity in humans is approximately 2 × 10

7 different clonotypes [

23]. With exposure to various antigens, the diversity of the TCR repertoire dynamically changes throughout its life but generally it decreases with aging [

24].

The tumor microenvironment (TME) contains numerous immune-related cells, and cytotoxic T cells play a central role [

25]. In the TME, tumor antigens are presented by antigen-presenting cells, resulting in the clonal expansion of T cells and restriction of the TCR repertoire [

26]. The relationship between TCR repertoire and prognosis has been studied in various tumors [

27,

28]. Campana et al. analyzed TCR repertoires based on colorectal cancer datasets from the Cancer Genome Atlas and found that patients with numerous TCR repertoires tended to have longer overall survival compared to those with fewer TCR repertoires [

29]. Moreover, based on an analysis of patients with metastatic breast cancer, lymphopenia before chemotherapy and lower TCR diversity were independent predictors of prognosis [

30]. Thus, the loss of TCR diversity is believed to result from the aggressiveness of tumors and may lead to immune system failure [

22].

Tumor mutation burden (TMB) influences the TCR repertoire, as higher values often lead to increased tumor clonality [

22]. Tumors with higher TMB levels produce more tumor neoantigens with high affinity for the human leukocyte antigen, thereby increasing their chances of being recognized by T cells [

22]. Notably, a study suggested that patients with higher TMB and clonality respond better to immunotherapies, especially in tumors with mismatch repair deficiency (MMR-d) or high microsatellite instability (MSI), due to increased tumor neoantigen production, thereby promoting tumor-specific lymphocyte infiltration and activation [

31]. Additionally, in colorectal cancer, MSI-high/MMR-d tumors show higher T-cell infiltration and more clonally expanded TCR repertoires that proliferate further after immunotherapy [

32].

Matzinger et al. reported that when tumor tissue is frozen, necrosis primarily occurs in the center of the tumor. In contrast, apoptosis mainly occurs in the periphery of the tumor, depending on the freezing temperature [

33]. In necrotic tissue, various molecules, including DNA, RNA, and damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs) are released from ruptured cells as danger signals [

33]. High mobility group box protein 1 (HMGB1), heat shock proteins, calreticulin, and GP96 have been identified as DAMPs, and HMGB1 is considered a key factor in activating CD8+ T cells through the innate immune system via Toll-like receptor-4 [

34]. Furthermore, necrotic tissue creates a cytokine-rich environment—such as interleukin (IL)-2, interferon (IFN)-γ, tumor necrosis factor-α, and IL-12—that induces CD8+ T-cell responses, and is presumably in a state conducive to immune reactions against the antigens released from frozen tissue [

35]. The TME surrounding the transplanted frozen tissue enhances T-cell activation by tumor neoantigens, with epitopes altered by freezing, potentially resulting in the clonal proliferation of T cells. The results of the current case report indicate a decrease in repertoire diversity after second-generation TES, which may have been caused by reactions to frozen tissue transplantation.

Immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) suggestively enhance the abscopal effect [

36]. According to a case report on patients with melanoma treated with cytotoxic T-lymphocyte antigen-4 inhibitors, the radiotherapy of thoracic spinal lesions reduced other metastatic tumors and increased NY-ESO-1 antibodies, a key factor in mediating the abscopal effect, was observed during radiotherapy [

36]. Analysis of the TCR repertoire is critical to predicting the efficacy of ICIs [

37]. Analysis of blood samples from patients with melanoma who received nivolumab revealed increased TCR clonality after ICI treatment was observed in both peripheral and tumor tissues [

37]. Similarly, a randomized controlled study of neoadjuvant ipilimumab and nivolumab for early-stage colon cancer showed that ICI responders had higher baseline CD8+PD-1+ T-cell infiltration and TCR clonality [

38]. Similar to radiotherapy, cryotherapy destroyed tumor tissue and increased tumor antigens potentially leading to a synergistic immune response, especially when combined with ICI [

39]. Thus, frozen tissue transplantation used in second-generation TES may enhance antitumor effects when combined with ICIs.

As the results are based on a single case report, it is difficult to gain a comprehensive understanding of the changes in TCR repertoires. Additionally, control data from patients who did not undergo frozen tissue transplantation are necessary for a meaningful comparison. Furthermore, the effects of cryoimmunization may vary depending on factors such as the type of primary lesion, amount of transplanted tissue, and subsequent treatments. To the best of our knowledge, this study is the first to employ TCR repertoire analysis following second-generation TES. Further validation and verification studies are planned.

5. Conclusions

Through TCR repertoire analysis, this study demonstrated that the transplantation of frozen tumor-containing autologous bone grafts has an impact on the immune system. This study is expected to serve as a foundation for the development of treatments that enhance immune activation.

6. Patents

Not applicable.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1. Full-length sequence of each sample; Figure S1. High-resolution figures.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.A., H.M.; methodology, H.A.; software, H.A.; validation, H.A.; formal analysis, H.A.; investigation, H.A., R.T., K.M, H.M.; resources, H.A., H.M.; data curation, H.A., R.T., K.M, H.M..; writing—original draft preparation, H.A.; writing—review and editing, H.A., H.K., R.T., N.S., K.K., K.Y., M.Y., K.M., S.S., A.A., C.E., and H.M..; visualization, H.A., R.T.; supervision, C.E., H.M.; project administration, H.A., H.K..; funding acquisition, H.A., H.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by JSPS KAKENHI Grant Number 20K09485 and 20K18006.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Nagoya City University Hospital (protocol code 60-21-0032; date of approval: October 11, 2021).

Informed Consent Statement

Written informed consent has been obtained from the patient to publish this paper.

Data Availability Statement

We provide details regarding where data supporting reported results in a supplemental data set.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully thank Tomoko Koshimae for the management of this study. During the preparation of this manuscript, the authors received support from Editage for proofreading services. The immunosequencing was outsourced to Genomics from Azenta Life Sciences (Waltham, MA, USA). The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ACE |

Abundance-based Coverage Estimator |

| CDR |

Complementarity Determining Region |

| DAMPs |

Damage-Associated Molecular Patterns |

| HMGB |

High Mobility Group Box Protein |

| ICI |

Immune Checkpoint Inhibitor |

| IFN |

Interferon |

| IL |

Interleukin |

| IMGT |

International ImMunoGeneTics |

| MMR-d |

Mismatch Repair-deficient |

| MSI |

Microsatellite Instability |

| TCR |

T-cell Receptor |

| TES |

Total En Bloc Spondylectomy |

| TMB |

Tumor Mutation Burden |

| TME |

Tumor Microenvironment |

| TRA |

T-cell Receptor α Chain |

| TRB |

T-cell Receptor β Chain |

Appendix A

Table A1.

Sequence quality.

Table A1.

Sequence quality.

| Sample |

Total reads |

Total bases |

Average length |

Q20 |

Q30 |

GC% |

N% |

TCR α chain

(preoperative) |

3157530 |

938871105 |

297.34 |

96.84 |

88.23 |

48.11 |

0.08 |

TCR β chain

(preoperative) |

3261872 |

967060609 |

296.47 |

96.92 |

88.66 |

53.89 |

0.08 |

TCR α chain

(postoperative) |

3120218 |

928251874 |

297.5 |

96.84 |

88.17 |

48.08 |

0.08 |

TCR β chain

(postoperative) |

4182078 |

1235268425 |

295.37 |

97.06 |

89.22 |

54.42 |

0.08 |

References

- Shulman, S.; Yantorno, C.; Bronson, P. Cryo-immunology: a method of immunization to autologous tissue. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med. 1967, 124, 658–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soanes, W.A.; Ablin, R.J.; Gonder, M.J. Remission of metastatic lesions following cryosurgery in prostatic cancer: immunologic considerations. J Urol. 1970, 104, 154–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gulley, J.L.; Madan, R.A.; Pachynski, R.; Mulders, P.; Sheikh, N.A.; Trager, J.; Drake, C.G. Role of Antigen Spread and Distinctive Characteristics of Immunotherapy in Cancer Treatment. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2017, 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mole, R.H. Whole body irradiation; radiobiology or medicine? Br J Radiol. 1953, 26, 234–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Golden, E.B.; Demaria, S.; Schiff, P.B.; Chachoua, A.; Formenti, S.C. An abscopal response to radiation and ipilimumab in a patient with metastatic non-small cell lung cancer. Cancer Immunol Res. 2013, 1, 365–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Dong, Y.; Kong, L.; Shi, F.; Zhu, H.; Yu, J. Abscopal effect of radiotherapy combined with immune checkpoint inhibitors. J Hematol Oncol. 2018, 11, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandra, R.A.; Wilhite, T.J.; Balboni, T.A.; Alexander, B.M.; Spektor, A.; Ott, P.A.; Ng, A.K.; Hodi, F.S.; Schoenfeld, J.D. A systematic evaluation of abscopal responses following radiotherapy in patients with metastatic melanoma treated with ipilimumab. Oncoimmunology. 2015, 4, e1046028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kodet, O.; Němejcova, K.; Strnadová, K.; Havlínová, A.; Dundr, P.; Krajsová, I.; Štork, J.; Smetana, K., Jr.; Lacina, L. The Abscopal Effect in the Era of Checkpoint Inhibitors. Int J Mol Sci. 2021, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mole, R.H. The effect of x-irradiation on the basal oxygen consumption of the rat. Q J Exp Physiol Cogn Med Sci. 1953, 38, 69–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsuchiya, H.; Wan, S.L.; Sakayama, K.; Yamamoto, N.; Nishida, H.; Tomita, K. Reconstruction using an autograft containing tumour treated by liquid nitrogen. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2005, 87, 218–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takeuchi, A.; Tsuchiya, H.; Setsu, N.; Gokita, T.; Tome, Y.; Asano, N.; Minami, Y.; Kawashima, H.; Fukushima, S.; Takenaka, S.; et al. What Are the Complications, Function, and Survival of Tumor-devitalized Autografts Used in Patients With Limb-sparing Surgery for Bone and Soft Tissue Tumors? A Japanese Musculoskeletal Oncology Group Multi-institutional Study. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2023, 481, 2110–2124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murakami, H.; Demura, S.; Kato, S.; Nishida, H.; Yoshioka, K.; Hayashi, H.; Inoue, K.; Ota, T.; Shinmura, K.; Yokogawa, N.; et al. Increase of IL-12 following reconstruction for total en bloc spondylectomy using frozen autografts treated with liquid nitrogen. PLoS One. 2013, 8, e64818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murakami, H.; Demura, S.; Kato, S.; Yoshioka, K.; Hayashi, H.; Inoue, K.; Ota, T.; Shinmura, K.; Yokogawa, N.; Fang, X.; et al. Systemic antitumor immune response following reconstruction using frozen autografts for total en bloc spondylectomy. Spine J. 2014, 14, 1567–1571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishii, T.; Murakami, H.; Demura, S.; Kato, S.; Yoshioka, K.; Fujii, M.; Igarashi, T.; Tsuchiya, H. Invasiveness Reduction of Recent Total En Bloc Spondylectomy: Assessment of the Learning Curve. Asian Spine J. 2016, 10, 522–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roth, D.B. V(D)J Recombination: Mechanism, Errors, and Fidelity. Microbiol Spectr. 2014, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hozumi, N.; Tonegawa, S. Evidence for somatic rearrangement of immunoglobulin genes coding for variable and constant regions. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1976, 73, 3628–3632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazzotti, L.; Gaimari, A.; Bravaccini, S.; Maltoni, R.; Cerchione, C.; Juan, M.; Navarro, E.A.-G.; Pasetto, A.; Nascimento Silva, D.; Ancarani, V.; et al. T-Cell Receptor Repertoire Sequencing and Its Applications: Focus on Infectious Diseases and Cancer. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2022, 23, 8590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, E.K.; Caruso, T.; Buscot, F.; Fischer, M.; Hancock, C.; Maier, T.S.; Meiners, T.; Müller, C.; Obermaier, E.; Prati, D.; et al. Choosing and using diversity indices: insights for ecological applications from the German Biodiversity Exploratories. Ecol Evol. 2014, 4, 3514–3524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein-Jöbstl, D.; Schornsteiner, E.; Mann, E.; Wagner, M.; Drillich, M.; Schmitz-Esser, S. Pyrosequencing reveals diverse fecal microbiota in Simmental calves during early development. Front Microbiol. 2014, 5, 622. [Google Scholar]

- Spellerberg, I.F.; Fedor, P.J. A tribute to Claude Shannon (1916–2001) and a plea for more rigorous use of species richness, species diversity and the ‘Shannon–Wiener’ Index. Global Ecology and Biogeography. 2003, 12, 177–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simpson, E.H. Measurement of Diversity. Nature. 1949, 163, 688–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aran, A.; Garrigós, L.; Curigliano, G.; Cortés, J.; Martí, M. Evaluation of the TCR Repertoire as a Predictive and Prognostic Biomarker in Cancer: Diversity or Clonality? Cancers (Basel). 2022, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arstila, T.P.; Casrouge, A.; Baron, V.; Even, J.; Kanellopoulos, J.; Kourilsky, P. A direct estimate of the human alphabeta T cell receptor diversity. Science. 1999, 286, 958–961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Attaf, M.; Huseby, E.; Sewell, A.K. αβ T cell receptors as predictors of health and disease. Cellular & Molecular Immunology. 2015, 12, 391–399. [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi, H.; Yoshimatsu, G.; Faustman, D.L. The Roles of TNFR2 Signaling in Cancer Cells and the Tumor Microenvironment and the Potency of TNFR2 Targeted Therapy. Cells. 2022, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, I.H.; Lee, S.B.; Jeong, B.K.; Park, J.; Kim, H.; Lee, G.; Cha, S.M.; Lee, H.; Gong, G.; Kwon, N.J.; et al. T cell receptor clonotype in tumor microenvironment contributes to intratumoral signaling network in patients with colorectal cancer. Immunol Res. 2024, 72, 921–937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, H.; Hanaoka, K.; Wada, H.; Kojima, D.; Watanabe, M. The Current Status of T Cell Receptor (TCR) Repertoire Analysis in Colorectal Cancer. Int J Mol Sci. 2025, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porciello, N.; Franzese, O.; D'Ambrosio, L.; Palermo, B.; Nisticò, P. T-cell repertoire diversity: friend or foe for protective antitumor response? J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2022, 41, 356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campana, L.G.; Mansoor, W.; Hill, J.; Macutkiewicz, C.; Curran, F.; Donnelly, D.; Hornung, B.; Charleston, P.; Bristow, R.; Lord, G.M.; et al. T-Cell Infiltration and Clonality May Identify Distinct Survival Groups in Colorectal Cancer: Development and Validation of a Prognostic Model Based on The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) and Clinical Proteomic Tumor Analysis Consortium (CPTAC). Cancers (Basel). 2022, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manuel, M.; Olivier, T.; Thomas, B.; Gilles, C.; Anais, C.; Gilles, P.; Tioka, R.; Audrey, G.; Solène, P.; Jean-François, M.; et al. Lymphopenia combined with low TCR diversity (divpenia) predicts poor overall survival in metastatic breast cancer patients. OncoImmunology. 2012, 1, 432–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahin, I.H.; Akce, M.; Alese, O.; Shaib, W.; Lesinski, G.B.; El-Rayes, B.; Wu, C. Immune checkpoint inhibitors for the treatment of MSI-H/MMR-D colorectal cancer and a perspective on resistance mechanisms. British Journal of Cancer. 2019, 121, 809–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akiyama, Y.; Kondou, R.; Iizuka, A.; Miyata, H.; Maeda, C.; Kanematsu, A.; Ashizawa, T.; Nagashima, T.; Urakami, K.; Shimoda, Y.; et al. Characterization of the Immunological Status of Hypermutated Solid Tumors in the Cancer Genome Analysis Project HOPE. Anticancer Res. 2022, 42, 3537–3549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matzinger, P. Tolerance, danger, and the extended family. Annu Rev Immunol. 1994, 12, 991–1045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Janopaul-Naylor, J.R.; Shen, Y.; Qian, D.C.; Buchwald, Z.S. The Abscopal Effect: A Review of Pre-Clinical and Clinical Advances. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2021, 22, 11061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdo, J.; Cornell, D.L.; Mittal, S.K.; Agrawal, D.K. Immunotherapy Plus Cryotherapy: Potential Augmented Abscopal Effect for Advanced Cancers. Front Oncol. 2018, 8, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Postow, M.A.; Callahan, M.K.; Barker, C.A.; Yamada, Y.; Yuan, J.; Kitano, S.; Mu, Z.; Rasalan, T.; Adamow, M.; Ritter, E.; et al. Immunologic correlates of the abscopal effect in a patient with melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2012, 366, 925–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inoue, H.; Park, J.H.; Kiyotani, K.; Zewde, M.; Miyashita, A.; Jinnin, M.; Kiniwa, Y.; Okuyama, R.; Tanaka, R.; Fujisawa, Y.; et al. Intratumoral expression levels of PD-L1, GZMA, and HLA-A along with oligoclonal T cell expansion associate with response to nivolumab in metastatic melanoma. Oncoimmunology. 2016, 5, e1204507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chalabi, M.; Fanchi, L.F.; Dijkstra, K.K.; Van den Berg, J.G.; Aalbers, A.G.; Sikorska, K.; Lopez-Yurda, M.; Grootscholten, C.; Beets, G.L.; Snaebjornsson, P.; et al. Neoadjuvant immunotherapy leads to pathological responses in MMR-proficient and MMR-deficient early-stage colon cancers. Nat Med. 2020, 26, 566–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yonezawa, N.; Murakami, H.; Demura, S.; Kato, S.; Miwa, S.; Yoshioka, K.; Shinmura, K.; Yokogawa, N.; Shimizu, T.; Oku, N.; et al. Abscopal Effect of Frozen Autograft Reconstruction Combined with an Immune Checkpoint Inhibitor Analyzed Using a Metastatic Bone Tumor Model. Int J Mol Sci. 2021, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).