Submitted:

14 May 2025

Posted:

15 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

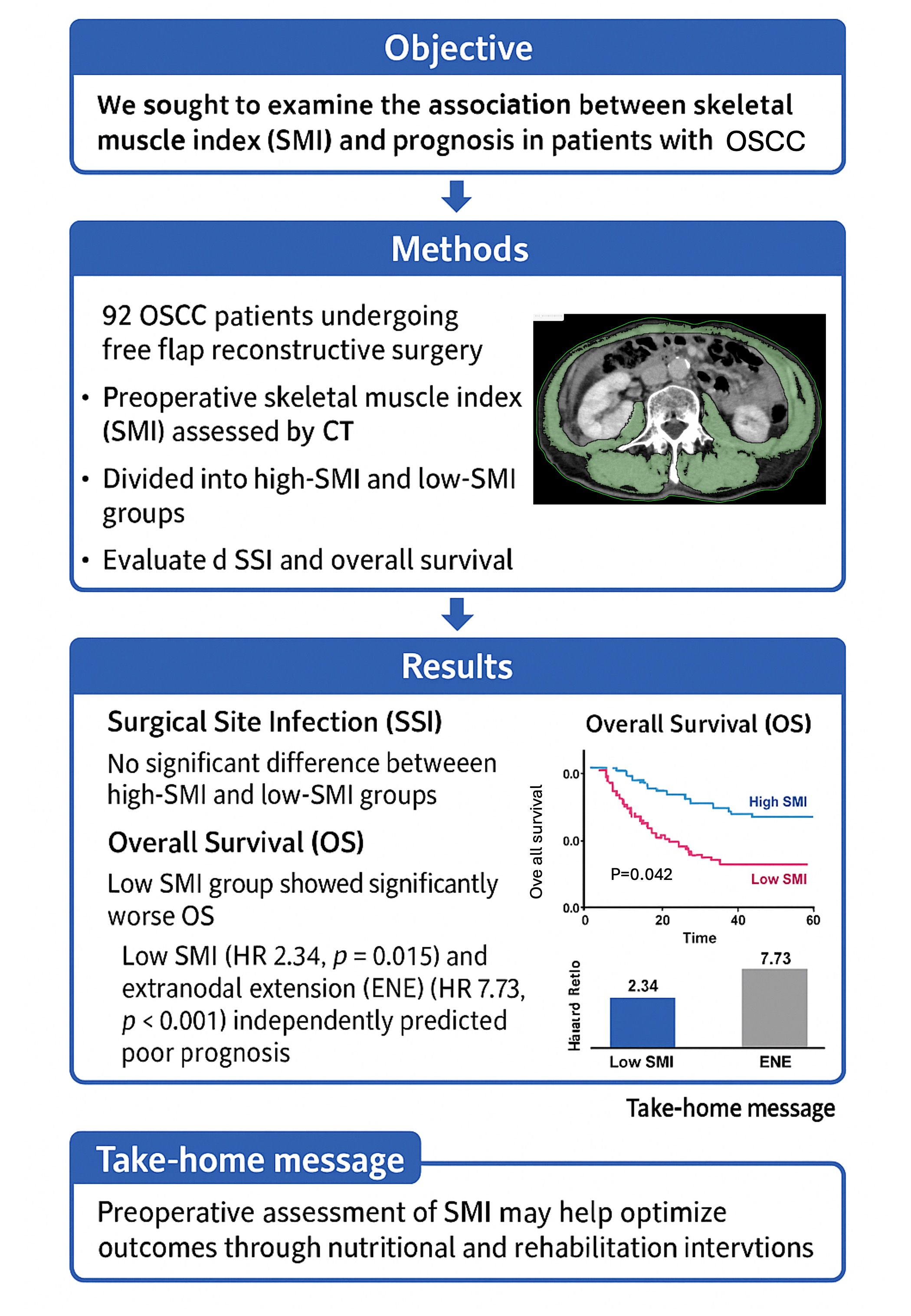

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Sample

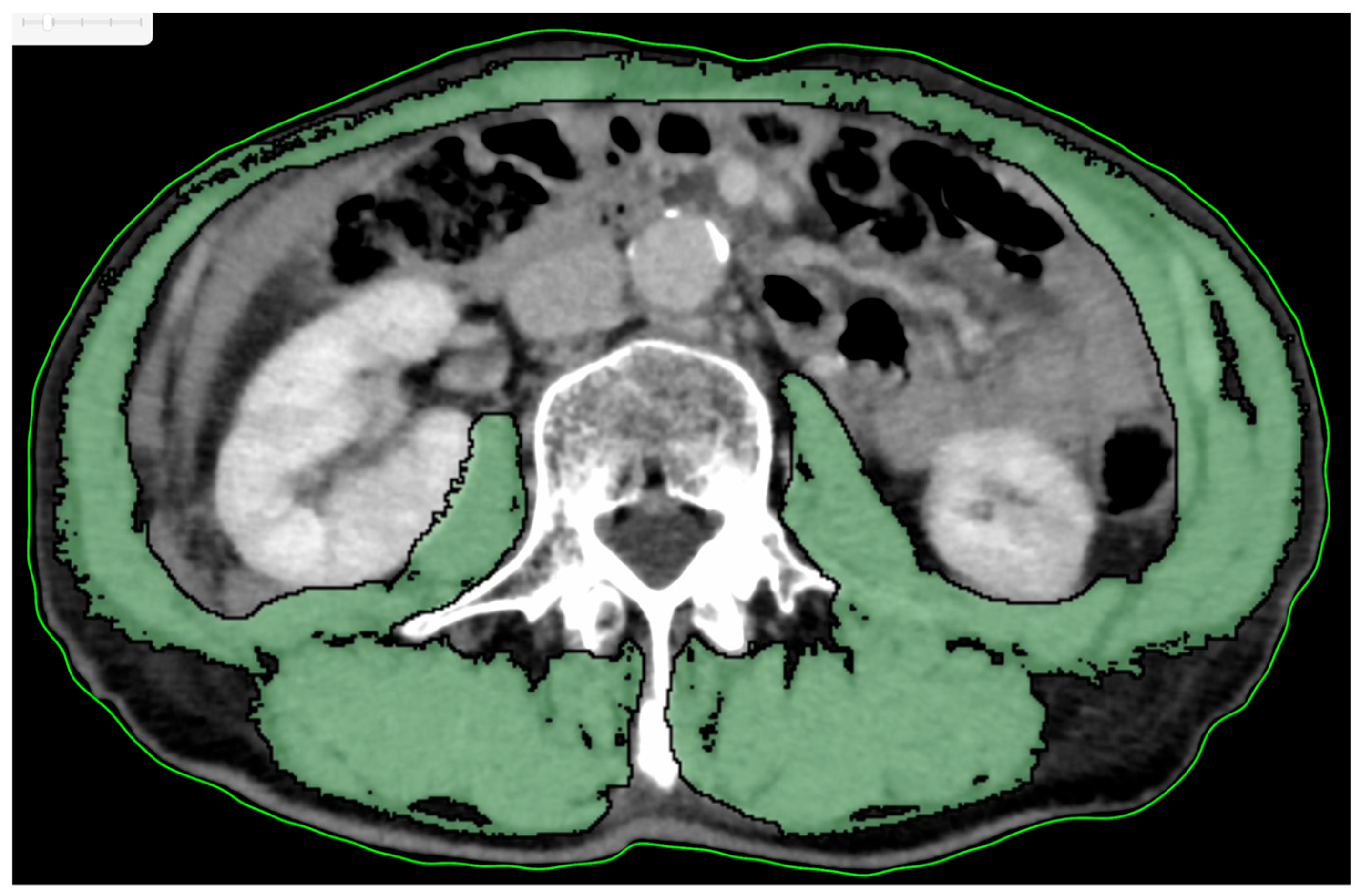

2.2. Study Variables

2.3. Data Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Patient Characteristics

3.2. Clinical Characteristics of the Patients Included in the Study Dichotomized with SMI Cutoff Value

3.3. Association Between Clinical Factors and OS and DFS

3.4. Cox Multivariate Regression Analysis

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ansari, E.; Chargi, N.; van Gemert, J.T.M.; van Es, R.J.J.; Dieleman, F.J.; Rosenberg, A.J.W.P.; Van Cann, E.M.; de Bree, R. Low skeletal muscle mass is a strong predictive factor for surgical complications and a prognostic factor in oral cancer patients undergoing mandibular reconstruction with a free fibula flap. Oral Oncol 2020, 101, 104530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Makiguchi, T.; Yamaguchi, T.; Nakamura, H.; Yamatsu, Y.; Hirai, Y.; Shoda, K.; Kurozumi, S.; Ibaragi, S.; Harimoto, N.; Motegi, S.I.; Shirabe, K.; Yokoo, S. Evaluation of overall and disease-free survival in patients with free flaps for oral cancer resection. Microsurgery 2020, 40, 859–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Graves, J.P.; Daher, G.S.; Bauman, M.M.J.; Moore, E.J.; Tasche, K.K.; Price, D.L.; Van Abel, K.M. Association of sarcopenia with oncologic outcomes of primary treatment among patients with oral cavity cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Oral Oncol 2023, 147, 106608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Makiguchi, T.; Yamaguchi, T.; Nakamura, H.; Suzuki, K.; Harimoto, N.; Shirabe, K.; Yokoo, S. Impact of skeletal muscle mass volume on surgical site infection in free flap reconstruction for oral cancer. Microsurgery 2019, 39, 598–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chargi, N.; Breik, O.; Forouzanfar, T.; Martin, T.; Praveen, P.; Idle, M.; Parmar, S.; de Bree, R. Association of low skeletal muscle mass and systemic inflammation with surgical complications and survival after microvascular flap reconstruction in patients with head and neck cancer. Head Neck 2022, 44, 2077–2094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ansari, E.; Ganry, L.; Van Cann, E.M.; de Bree, R. Impact of low skeletal muscle mass on postoperative complications in head and neck cancer patients undergoing free flap reconstructive surgery – A systematic review and meta-analysis. Oral Oncol 2023, 147, 106598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bernier, J.; Domenge, C.; Ozsahin, M.; Matuszewska, K.; Lefèbvre, J.L.; Greiner, R.H.; Giralt, J.; Maingon, P.; Rolland, F.; Bolla, M.; Cognetti, F.; Bourhis, J.; Kirkpatrick, A.; van Glabbeke, M.; European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Trial 22931. Postoperative irradiation with or without concomitant chemotherapy for locally advanced head and neck cancer. N Engl J Med 2004, 350, 1945–1952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cooper, J.S.; Pajak, T.F.; Forastiere, A.A.; Jacobs, J.; Campbell, B.H.; Saxman, S.B.; Kish, J.A.; Kim, H.E.; Cmelak, A.J.; Rotman, M.; Machtay, M.; Ensley, J.F.; Chao, K.S.; Schultz, C.J.; Lee, N.; Fu, K.K.; Radiation Therapy Oncology Group 9501/Intergroup. Postoperative concurrent radiotherapy and chemotherapy for high-risk squamous-cell carcinoma of the head and neck. N Engl J Med 2004, 350, 1937–1944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakamura, H.; Makiguchi, T.; Yamaguchi, T.; Suzuki, K.; Yokoo, S. Impact of sarcopenia on postoperative surgical site infections in patients undergoing flap reconstruction for oral cancer. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2020, 49, 576–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maeda, N.; Shirakawa, Y.; Tanabe, S.; Sakurama, K.; Noma, K.; Fujiwara, T. Skeletal muscle loss in the postoperative acute phase after esophageal cancer surgery as a new prognostic factor. World J Surg Oncol 2020, 18, 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonavolontà, P.; Improta, G.; Dell'Aversana Orabona, G.; Goglia, F.; Abbate, V.; Sorrentino, A.; Piloni, S.; Salzano, G.; Iaconetta, G.; Califano, L. Evaluation of sarcopenia and sarcopenic obesity in patients affected by oral squamous cell carcinoma: A retrospective single-center study. J Craniomaxillofac Surg 2023, 51, 7–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ansari, E.; Chargi, N.; van Es, R.J.J.; Dieleman, F.J.; Van Cann, E.M.; de Bree, R. Association of preoperative low skeletal muscle mass with postoperative complications after selective neck dissection. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2022, 51, 1389–1393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mangram, A.J.; Horan, T.C.; Pearson, M.L.; Silver, L.C.; Jarvis, W.R. Guideline for Prevention of Surgical Site Infection, 1999. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Hospital Infection Control Practices Advisory Committee. American journal of infection control 1999, 27, 97–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vangelov, B.; Bauer, J.; Moses, D.; Smee, R. The effectiveness of skeletal muscle evaluation at the third cervical vertebral level for computed tomography-defined sarcopenia assessment in patients with head and neck cancer. Head Neck 2022, 44, 1047–1056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoon, J.K.; Jang, J.Y.; An, Y.S.; Lee, S.J. Skeletal muscle mass at C3 may not be a strong predictor for skeletal muscle mass at L3 in sarcopenic patients with head and neck cancer. PLoS One 2021, 16, 0254844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Swartz, J.E.; Pothen, A.J.; Wegner, I.; Smid, E.J.; Swart, K.M.; de Bree, R.; Leenen, L.P.; Grolman, W. Feasibility of using head and neck CT imaging to assess skeletal muscle mass in head and neck cancer patients. Oral Oncol 2016, 62, 28–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bril, S.I.; Wendrich, A.W.; Swartz, J.E.; Wegner, I.; Pameijer, F.; Smid, E.J.; Bol, G.H.; Pothen, A.J.; de Bree, R. Interobserver agreement of skeletal muscle mass measurement on head and neck CT imaging at the level of the third cervical vertebra. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol 2019, 276, 1175–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamahara, K.; Mizukoshi, A.; Lee, K.; Ikegami, S. Sarcopenia with inflammation as a predictor of survival in patients with head and neck cancer. Auris Nasus Larynx 2021, 48, 1013–1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sandmael, J.A.; Bye, A.; Solheim, T.S.; Stene, G.B.; Thorsen, L.; Kaasa, S.; Lund, J.Å.; Oldervoll, L.M. Feasibility and preliminary effects of resistance training and nutritional supplements during versus after radiotherapy in patients with head and neck cancer: A pilot randomized trial. Cancer 2017, 123, 4440–4448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wobith, M.; Weimann, A. Oral Nutritional Supplements and Enteral Nutrition in Patients with Gastrointestinal Surgery. Nutrients 2021, 13, 2655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variable | Total no. of patients |

Low SMI No. of patients (%) n=47 |

High SMI No. of patients (%) n=45 |

P-value† | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex |

Male Female |

59 33 |

30(63.8) 17(36.2) |

29(64.4) 16(35.6) |

0.951 |

| Age (years) |

<65 ≥65 |

37 55 |

14(29.8) 33(70.2) |

23(51.1) 22(48.9) |

0.037* |

| BMI (kg/m2) |

<18.5 ≥18.5 |

11 81 |

8(17.0) 39(83.0) |

3(6.7) 42(93.3) |

0.199 |

| Tabaco consumption | Ever Never |

45 47 |

25(53.2) 22(46.8) |

20(44.4) 25(55.6) |

0.401 |

| Alcohol consumption | Present Absent |

44 48 |

24(51.1) 23(48.9) |

20(44.4) 25(55.6) |

0.525 |

| Primary site |

Tongue Lower gingiva Buccal mucosa Floor of the mouth Upper gingiva |

41 35 8 7 1 |

25(53.2) 15(31.9) 3(6.4) 4(8.5) 0(0) |

16(35.6) 20(44.4) 5(11.1) 3(6.7) 1(2.2) |

0.368 |

| Clinical T classification |

T2 T3 T4a T4b |

17 15 47 13 |

9(19.1) 9(19.1) 24(51.1) 5(10.6) |

8(17.8) 6(13.3) 23(51.1) 8(17.8) |

0.722 |

| Clinical N classification | N0 N1 N2b N2c N3b |

41 11 35 4 1 |

25(53.2) 3(6.4) 15(31.9) 3(6.4) 1(2.1) |

16(35.6) 8(17.8) 20(44.4) 1(2.2) 0(0) |

0.140 |

| Stage classification | II III IVa IVb |

9 11 58 14 |

5(10.6) 7(14.9) 29(61.7) 6(12.8) |

4(8.9) 4(8.9) 29(64.4) 8(17.8) |

0.760 |

| Histological grade |

G1 G2 G3 |

49 34 9 |

21(44.7) 19(40.4) 7(14.9) |

28(62.2) 15(33.3) 2(4.4) |

0.122 |

| Preoperative radiotherapy | Present Absent |

6 86 |

3(6.4) 44(93.6) |

3(6.7) 42(93.3) |

1.000 |

| Pathological N classification | N0 N1 N2b N2c N3b |

51 13 18 1 9 |

27(57.4) 7(14.9) 10(21.3) 0(0) 3(6.4) |

24(53.3) 6(13.3) 8(17.8) 1(2.2) 6(13.3) |

0.657 |

| Surgical site infection | Present Absent |

11 81 |

5(10.6) 42(89.4) |

6(13.3) 39(86.7) |

0.690 |

| Delirium | Present Absent |

27 65 |

15(31.9) 32(68.1) |

12(26.7) 33(73.3) |

0.581 |

| Postoperative pneumonia | Present Absent |

21 71 |

8(17.0) 39(83.0) |

13(28.9) 32(71.1) |

0.175 |

| Primary recurrence | Present Absent |

14 78 |

9(19.1) 38(80.9) |

5(11.1) 40(88.9) |

0.283 |

| Neck recurrence | Present Absent |

11 81 |

8(17.0) 39(83.0) |

3(6.7) 42(93.3) |

0.199 |

| Distant metastasis | Present Absent |

20 72 |

13(27.7) 34(72.3) |

7(15.6) 38(84.4) |

0.159 |

| Free flap type | ALT FF RAMF |

37 31 24 |

23(48.9) 13(27.7) 11(23.4) |

14(31.1) 18(40.0) 13(28.9) |

0.210 |

| Variable (continuous) |

Low SMI Median (range) |

High SMI Median (range) |

P-value†† | ||

| HCU duration | (days) | 7 (4-10) | 7 (5-12) | 0.411 | |

| Hospital stay duration | (days) | 38(22-152) | 36(19-98) | 0.537 | |

| PS | 0 (0-1) | 0 (0-1) | 0.692 | ||

| ASA |

2 (1-3) | 2 (1-3) | 0.540 | ||

| Bleeding count | (mL) | 374(126-1,031) | 510(70-1,278) | 0.004** | |

| Operative time | (hour: minute) | 11:05(8:24-15:15) | 11:47(8:20-15:31) | 0.133 | |

| Albumin | (mg/dL) | 4.2(3.3-5.1) | 4.2(3.2-4.8) | 0.820 | |

| NLR | 2.74 (1.09-11.70) |

2.39 (0.93-15.23) |

0.246 | ||

| LMR | 4.38 (1.14-11.15) |

5.43 (1.81-8.80) |

0.060 | ||

| PLR | 149.54 (73.03-529.79) |

134.81 (34.52-291.06) |

0.193 | ||

| PNI | 116.90 (63.01-228.00) |

127.45 (89.50-222.00) |

0.119 | ||

| MAR | 88.64 (0-200.00) |

90.24 (34.55-160.98) |

0.919 | ||

| CAR | 0.0200 (0.0063-0.1921) |

0.0136 (0.0063-0.6641) |

0.379 |

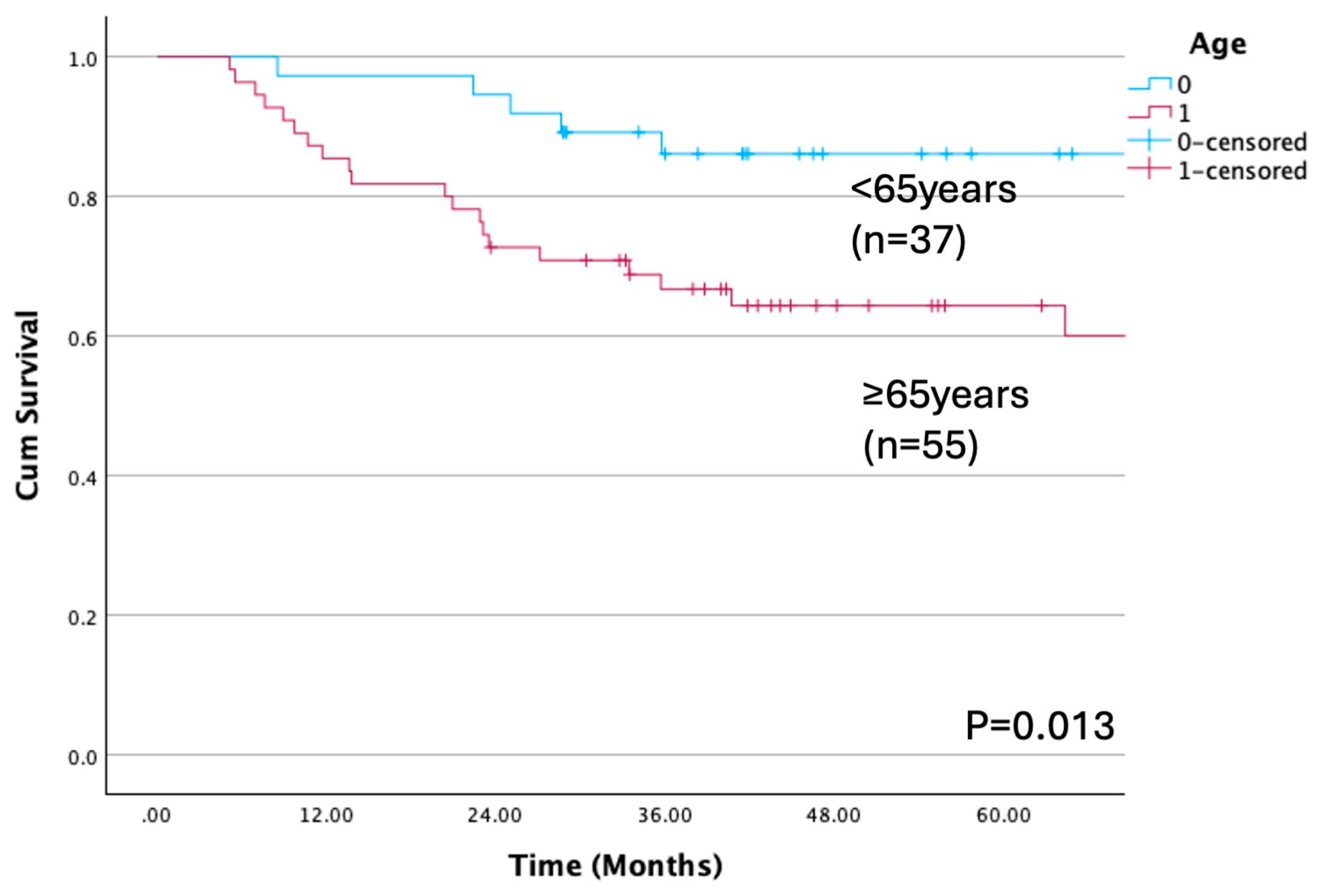

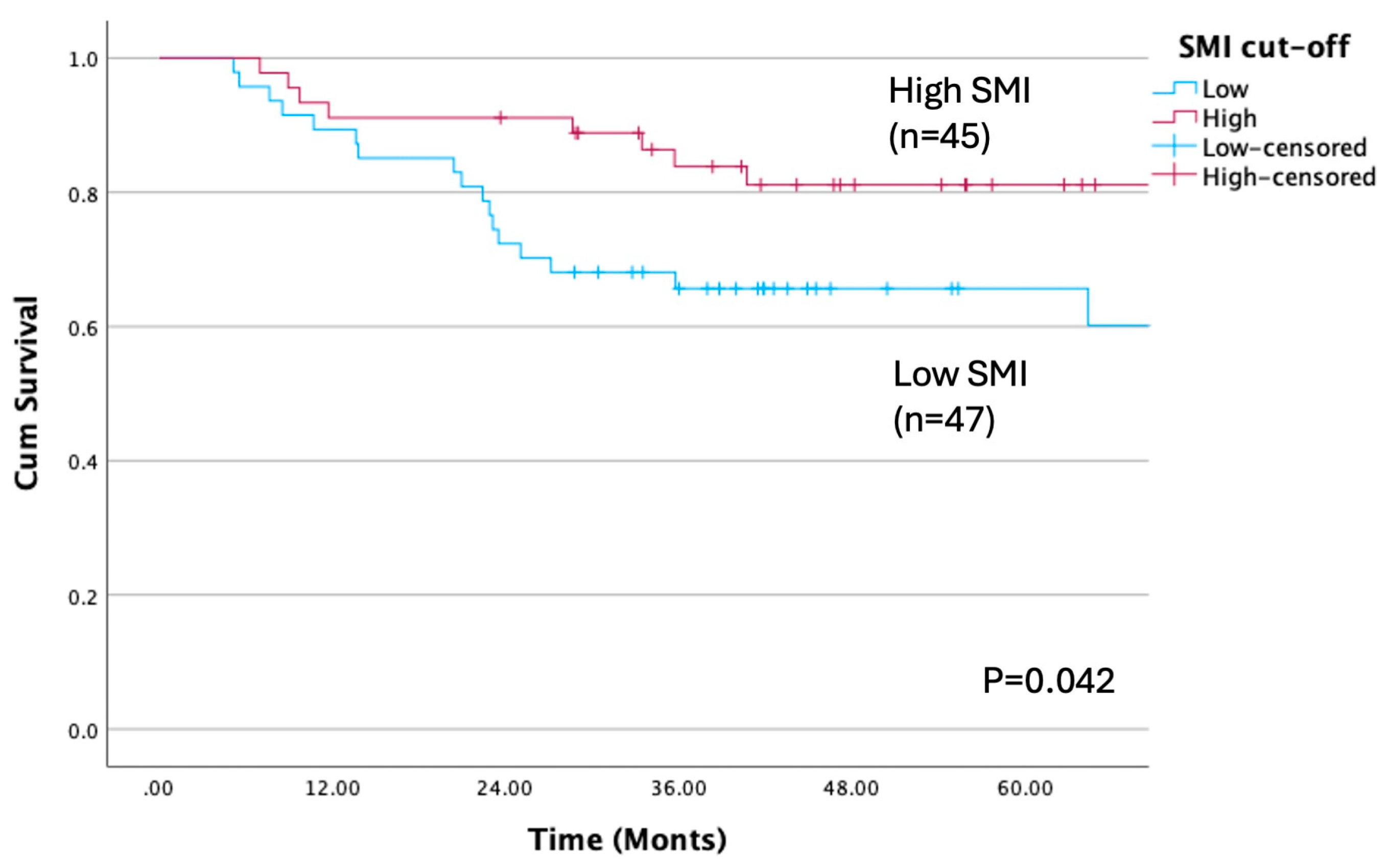

| Variables | No. of patients (%) | OS (%) | P † | DFS (%) | P † | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | ≥65 | 55(59.8) | 60.1 | 0.013* | 58.0 | 0.057 |

| (years) | <65 | 37(40.2) | 86.1 | 78.4 | ||

| Sex | Male | 59(64.1) | 68.4 | 0.658 | 66.1 | 0.665 |

| Female | 33(35.9) | 74.8 | 67.3 | |||

| BMI (kg/m2) | <18.5 | 11 (12.0) | 54.5 | 0.051 | 54.5 | 0.231 |

| ≥18.5 | 81 (88.0) | 73.2 | 68.1 | |||

| SMI | High | 45(48.9) | 81.1 | 0.042* | 81.4 | 0.070 |

| Low | 47(51.1) | 60.2 | 65.4 | |||

| Tobacco consumption | Ever | 45(48.9) | 74.3 | 0.535 | 64.4 | 0.601 |

| Never | 47(51.1) | 68.4 | 68.7 | |||

| Alcohol consumption | Ever | 44(47.8) | 76.3 | 0.442 | 68.2 | 0.804 |

| Never | 48(52.2) | 66.5 | 65.2 | |||

| Diabetes melitus | Present | 21(22.8) | 71.4 | 0.929 | 66.7 | 0.965 |

| None | 71(77.2) | 70.2 | 66.5 | |||

| Cardiovascular disease | Present | 7( 7.6) | 47.6 | 0.284 | 57.1 | 0.442 |

| None | 85(92.4) | 73.3 | 67.3 | |||

| Cerebrovascular disease | Present | 8( 8.7) | 87.5 | 0.320 | 100 | 0.062 |

| None | 84(91.3) | 69.0 | 63.3 | |||

| History of cancer | Present | 16(17.4) | 80.2 | 0.400 | 80.8 | 0.241 |

| None | 76(82.6) | 69.0 | 63.6 | |||

| Preoperative radiotherapy | Present | 6( 6.5) | 66.7 | 0.829 | 83.3 | 0.381 |

| Absent | 86(93.5) | 70.8 | 65.3 | |||

| Primary site | Tongue | 41 (44.6) | 67.5 | <0.001** | 63.4 | <0.001** |

| Lower gingiva | 35 (38.1) | 100 | 100 | |||

| Buccal mucosa | 8 (8.7) | 75.0 | 0 | |||

| Floor of the mouth | 7 (7.6) | 0 | 42.9 | |||

| Upper gingiva | 1 (1.1) | 100 | 100 | |||

| Clinical T classification | T2 | 17 (18.5) | 74.9 | 0.871 | 64.7 | 0.904 |

| T3 | 15 (16.3) | 80.0 | 64.0 | |||

| T4a | 47 (51.1) | 67.8 | 68.0 | |||

| T4b | 13 (14.1) | 68.4 | 61.5 | |||

| Clinical N classification | N0 | 41 (44.6) | 77.4 | 0.014* | 78.0 | 0.018* |

| N1 | 11 (12.0) | 77.9 | 53.0 | |||

| N2b | 35 (38.0) | 70.4 | 65.7 | |||

| N2c | 4 (4.3) | 25.0 | 25.0 | |||

| N3b | 1 (1.1) | 0 | 0 | |||

| Clinical stage classification | II | 9 (9.8) | 77.8 | 0.803 | 66.7 | 0.830 |

| III | 11 (12.0) | 72.7 | 54.5 | |||

| IVA | 58 (63.0) | 71.6 | 70.6 | |||

| IVB | 14 (15.2) | 63.5 | 57.1 | |||

| Pathological surgical margin (mm) | ≥5 | 51 | 73.3 | 0.059 | 69.0 | 0.076 |

| <5 | 34 | 73.5 | 67.6 | |||

| Positive | 5 | 0 | 20.0 | |||

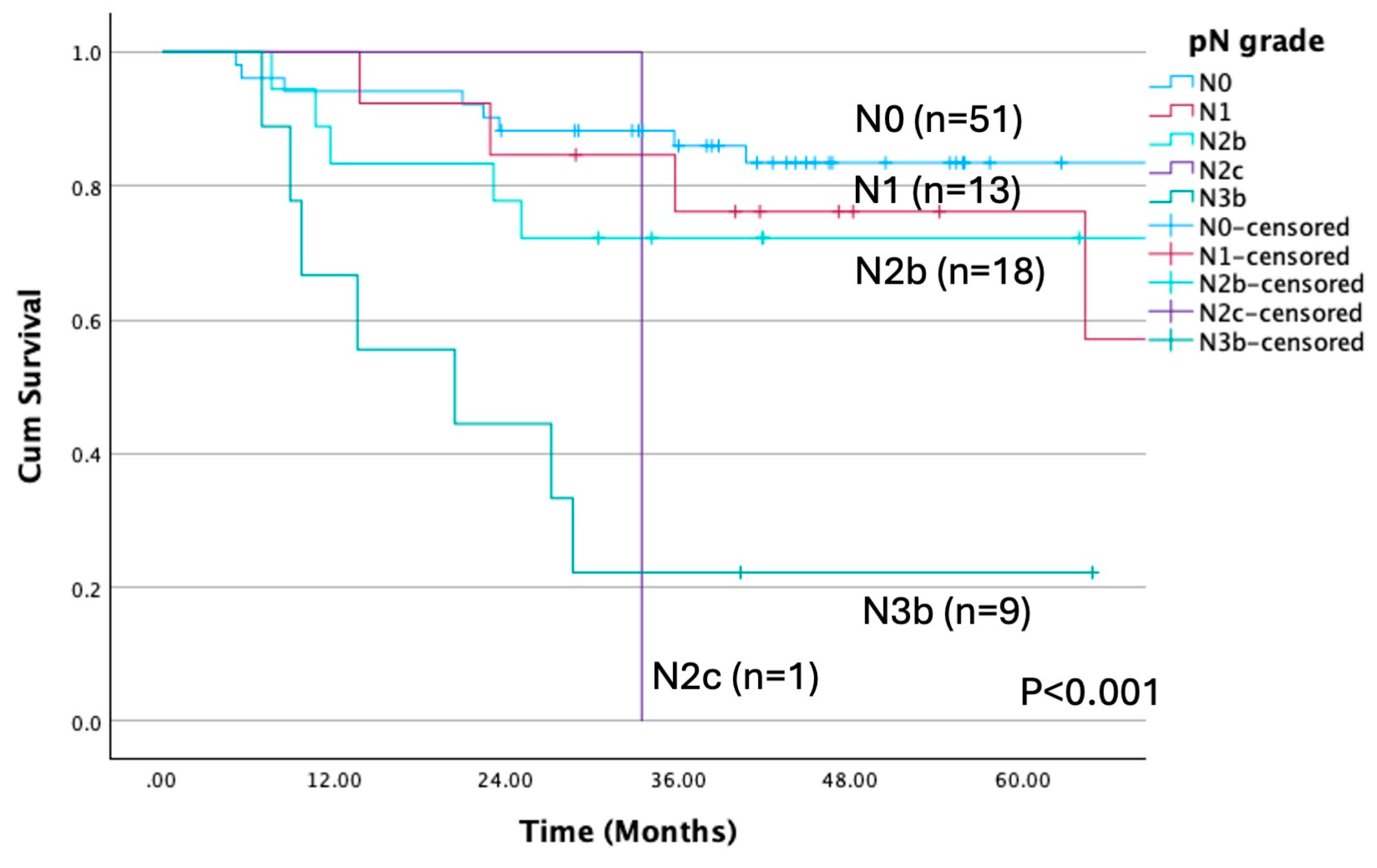

| pN classification | N0 | 51 (55.4) | 83.4 | <0.001** | 86.2 | <0.001** |

| N1 | 13 (14.1) | 57.1 | 61.5 | |||

| N2b | 18 (19.6) | 72.2 | 42.9 | |||

| N2c | 1 (1.1) | 0 | 0 | |||

| N3b | 9(9.8) | 22.2 | 22.2 | |||

| pN | N1-3b | 41(44.6) | 55.8 | 0.007** | 42.5 | <0.001** |

| N0 | 51(55.4) | 83.4 | 86.2 | |||

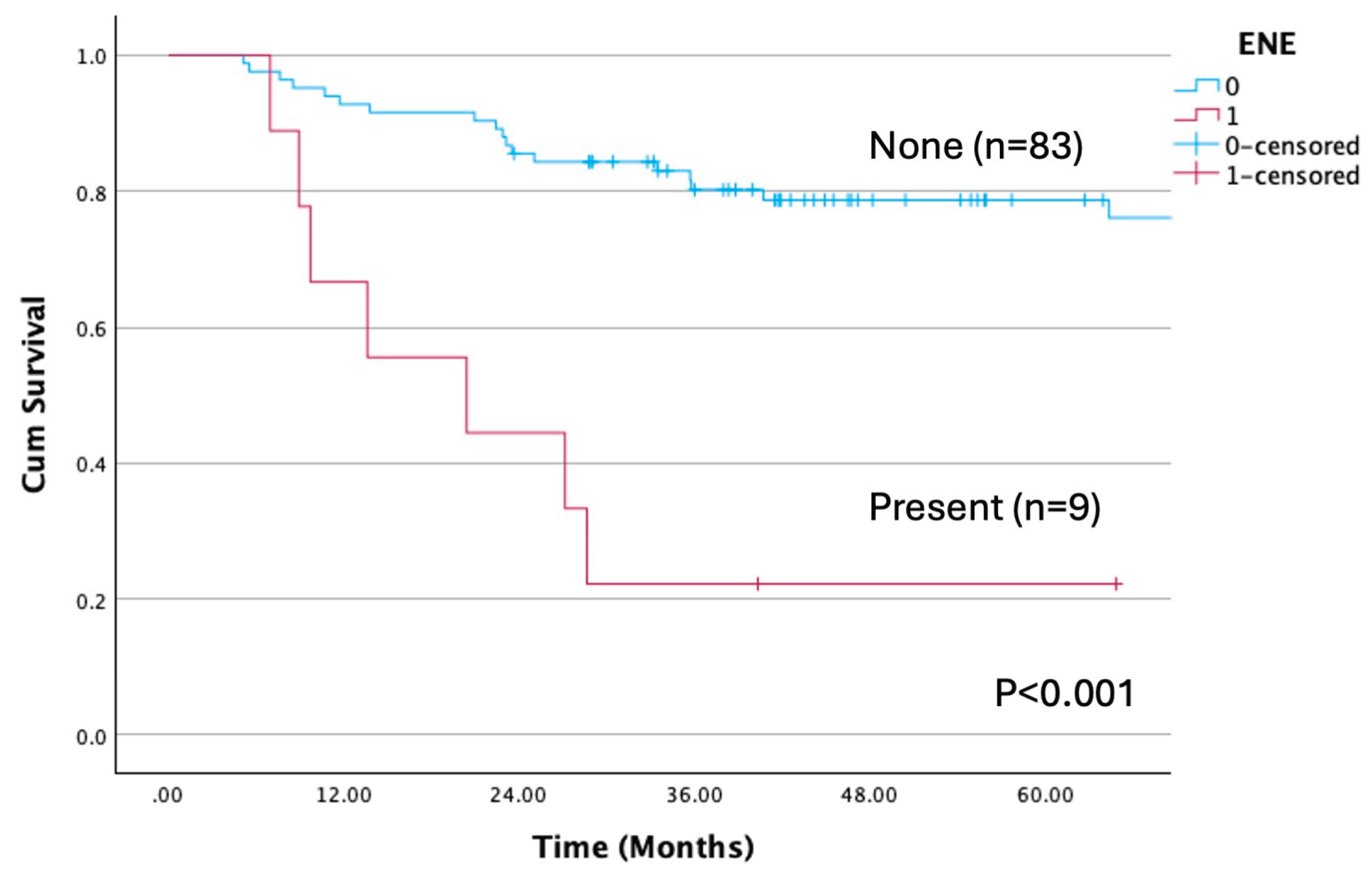

| ENE | Present | 9(9.8) | 22.2 | <0.001** | 22.2 | <0.001** |

| None | 83(90.2) | 76.1 | 71.3 | |||

| Histological grade | G1 | 49(53.3) | 74.9 | 0.829 | 69.3 | 0.974 |

| G2 | 34(37.0) | 67.1 | 63.0 | |||

| G3 | 9 (9.8) | 66.7 | 66.7 | |||

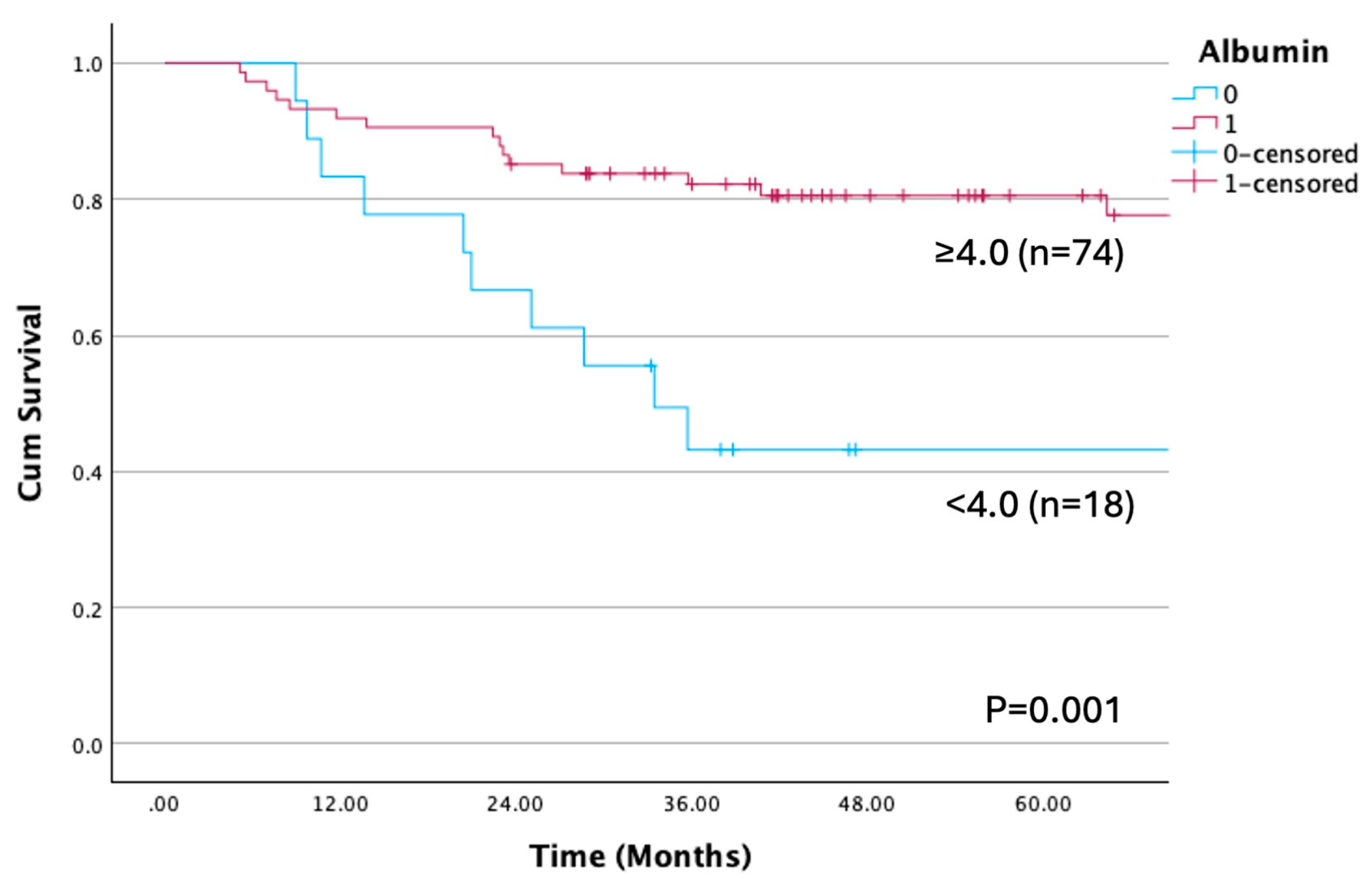

| Albumin | <4.0 | 18(19.6) | 43.2 | 0.001** | 44.4 | 0.018* |

| (mg/dL) | ≥4.0 | 74(80.4) | 77.7 | 72.0 |

| Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | HR (95% CI) | P values † | HR (95% CI) | P values † |

| Age (years) | 3.225 (1.209-8.602) | 0.019* | ||

| ≥65 vs. <65 | ||||

| SMI | ||||

| Low vs. High | 2.339 (1.008-5.429) | 0.048* | 2.900(1.226-6.862) | 0.015** |

| pN | ||||

| N0 vs. N1-3b | 3.008 (1.297-6.976) | 0.010* | ||

| ENE | ||||

| Present vs. Absent | 6.147 (2.527-14.949) | <0.001** | 7.727 (3.083-19.368) | <0.001** |

| Albumin (mg/dL) | ||||

| <4.0 vs. ≥4.0 | 3.429 (1.532-7.676) | 0.003** |

| Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | |||

| Variables | HR (95% CI) | P values † | HR (95% CI) | P values † |

| pN | ||||

| N0 vs. N1-3b | 4.445 (1.903-10.379) | <0.001* | 4.248 (1.813-9.953) | <0.001** |

| ENE | ||||

| Present vs. Absent | 3.384 (1.435-7.980) | 0.005** | ||

| Albumin (mg/dL) | ||||

| <4.0vs. ≥4.0 | 2.294 (1.069-4.921) | 0.033* | 2.039 (0.944-4.406) | 0.070 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).