1. Introduction

As an important pillar of the agricultural economy, waterfowl breeding plays a key role in meeting market demand, promoting breed improvement and biodiversity conservation. With the development of breeding technology, improving the reproductive efficiency of waterfowl has become a research focus. Cryopreservation of duck semen is the most practical method for long-term preservation of its genetic resources [

1,

2], and it is also one of the most important steps in artificial insemination technology [

3], and has been widely used in mammals [

4,

5], but still faces challenges in the field of poultry [

6]. Avian spermatozoa are extremely sensitive to temperature changes due to their unique morphology, structure and biochemical properties [

7,

8], and are prone to plasma membrane rupture, acrosome damage and oxidative stress during the freezing process, leading to a significant decrease in vitality and fertilization ability [

9]. To a certain extent, the development of poultry semen cryopreservation technology is limited, resulting in the technology is still in the experimental stage [

10], and is inapplicable for commercial application and the protection of genetic information and resources [

11]. Therefore, optimizing the freezing procedure of avian semen and elucidating the mechanism of freezing damage are essential to break through the technological bottleneck.

In contrast to mammals, poultry spermatozoa have an elongated morphology, minimal cytoplasmic content, and a plasma membrane rich in polyunsaturated fatty acids [

12,

13,

14]. This structure facilitates the movement of spermatozoa in the female reproductive tract, but makes them highly susceptible to physical and biochemical damage during freezing [

15]. Physical damage is mainly caused by the formation of intracellular ice crystals, especially in the “ice crystal danger zone” between -15°C and -60°C, where the mechanical stress of ice crystals can directly lead to rupture of the plasma membrane and damage to the acrosome structure (16-18]. Biochemical damage is closely related to freezing-induced oxidative stress. In cold environments, dysfunction of the mitochondrial respiratory chain leads to the overproduction of reactive oxygen species such as superoxide radicals (O

2-) and hydrogen peroxide [H

2O

2] [

19]. When the concentration of these oxidation products exceeds the regulatory range of the cell’s own antioxidant defense mechanisms, a series of oxidative damages are induced, including pathological changes such as lipid peroxidation of biological membranes [

20,

21], oxidative breaks in genetic material, and alterations in protein structure [

22,

23]. In addition, this process leads to impaired sperm energy metabolism, reduced ATP synthesis and loss of sperm motility [

24,

25]. It has been found that the levels of malondialdehyde (MDA), a marker of lipid peroxidation, are significantly elevated and the activity of superoxide dismutase (SOD) is significantly decreased in spermatozoa after cryopreservation treatment compared to fresh sperm samples, suggesting that oxidative stress is a central mechanism leading to sperm damage during sperm cryoinjury [

26,

27].

Although some studies have mitigated oxidative damage through the addition of exogenous antioxidants, such as astaxanthin [

3], apigenin [

28], Mito-TEMPO [

29] and so on, the optimization of the freezing procedure itself is still neglected. Freezing rate, as a key parameter, needs to be balanced between ice crystal formation and osmotic pressure damage. Rapid cooling (>50℃ /min), while inhibiting intracellular ice crystals, may lead to membrane lipid phase change, while slow cooling (<10℃ /min) prolongs the exposure of cells to hyperosmotic environments and exacerbates reactive oxygen species (

ROS) accumulation [

23,

30]. Currently, programmed freezing studies on chicken semen have demonstrated that a multi-stage warming strategy, such as an initial slow descent to avoid cold shock and a later rapid descent to reduce ice crystals, can improve sperm vitality to more than 50% [

31]. However, there is a paucity of studies on duck semen, and most of the available literature follows the chicken semen freezing protocol. Therefore, in this study, four differentiated freezing procedures (P1-P4) were designed for Jinding ducks, and systematically compared their effects on sperm vitality, vitality, mortality, antioxidant enzyme activity, lipid peroxidation marker content, and total antioxidant capacity, with the aim of investigating the mechanisms of different freezing protocols on the regulation of sperm quality through the oxidative stress pathway, and to provide theoretical basis for the standardization of semen cryopreservation technology in ducks. The purpose of this study is to investigate the regulation mechanism of sperm quality through oxidative stress in different freezing protocols and to provide theoretical basis for standardization of duck semen cryopreservation technology.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Ethics Statement

This research plan has been approved by the Animal Protection and Utilization Committee of Jiangsu Poultry Science Institute (China; approval no. CAC-JIPS01342). All possible efforts were made to reduce the animals’ suffering to the minimum.

2.2. Animals and Groups

In this study, 45 healthy 43-week-old Jinding male ducks with consistent body weight and condition provided by the National Domesticated Animal Germplasm Resource Bank (2025) were selected, and all individuals were trained by artificial massage method for 2 weeks to ensure that qualified semen could be collected stably. During the training period, the experimental ducks were housed in a single cage in a stepped cage and fed full-value feed according to the nutritional standards for laying ducks, with free access to water. Before the experiment, 45 male ducks were randomly divided into a fresh semen control group (CK) and four freezing procedure treatment groups (P1-P4), with three replicates in each group and three ducks in each replicate. Their breeding followed the specification for healthy poultry production (GB/T32148-2015).

2.3. Preparation of Semen Dilutions

Beltsville Poultry Semen Extender (BPSE) diluent was used, which was prepared as follows: accurately weighed D-fructose 0.5 g, monosodium glutamate 0.867 g, magnesium chloride hexahydrate 0.034 g, sodium acetate 0.43 g, sodium citrate 0.064 g, potassium dihydrogen phosphate 0.065 g, disodium hydrogen phosphate 0.4732 g, N-trimethyl-2-aminoethanesulfonic acid 0.195 g, and gradient dissolution using ddH2O. After the solutes were completely dissociated, the mixture was volume-determined to a final 100 mL, the pH of the solution was adjusted to 7.2-7.4, and the solution was stored at 4°C for spare use.

2.4. Semen Collection and Pretreatment

The semen collection interval was 48 hours, and three repetitions were performed. The time of semen collection was fixed at 9:00 a.m. daily, and semen samples were obtained by a combination of dorsal-abdominal massage and cloacal stimulation. Qualified samples had to meet the following conditions: milky white color and homogeneous texture, without fecal or urine contamination. After collection, semen samples were quickly transferred to a 15 mL sterile centrifuge tube, gently mixed with an equal volume of BPSE diluent pre-cooled at 4°C, and equilibrated at 4°C for 1 h without being exposed to any heat shocks and sunlight. Then, the diluted semen was mixed with an equal volume of 8% dimethylacetamide (DMA) (92% dilution + 8% DMA) and equilibrated at 4℃ for 30 min.

2.5. Semen Freezing and Thawing

The equilibrated semen was dispensed into 0.25 mL wheat tubes, and four freezing procedures were performed using a programmed cryostat (Thermo Fisher, item number TSCM17PV) (

Table 1). Upon completion of the program, the wheat tubes were quickly transferred to liquid nitrogen and stored for 1 h. The wheat tubes were thawed using a 37°C water bath for 30 s, followed immediately by sperm vitality testing.

2.6. Semen Quality Testing

The detection method was in accordance with the method of testing methods of poultry semen quality (NY/T 4047-2021). Sperm vitality and motility were detected using a fully automated sperm analyzer (Nanjing Songjing Tianlun Biotechnology Co., Ltd., item number MDO300A).

2.7. Measurement of Oxidative Stress Indicators

According to the results of semen quality test, the oxidative stress indicators of the control group and the two groups with the highest and lowest sperm motility and vitality were measured. Semen samples were taken and the following indicators were measured: total SOD, CAT, GSH-Px activity, and MDA, T-AOC content, which were detected by using the kit of Nanjing Jiancheng Bioengineering Research Institute Co. Ltd., and the results were standardized to protein concentration.

2.8. Data Processing and Analysis

The experimental data were expressed as mean ± standard deviation and were analyzed by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) using SPSS 20.0 software and differences between groups were tested by Tukey HSD method with the level of significance set at P < 0.05. Graphs were drawn using GraphPad Prism 9.0.

3. Results

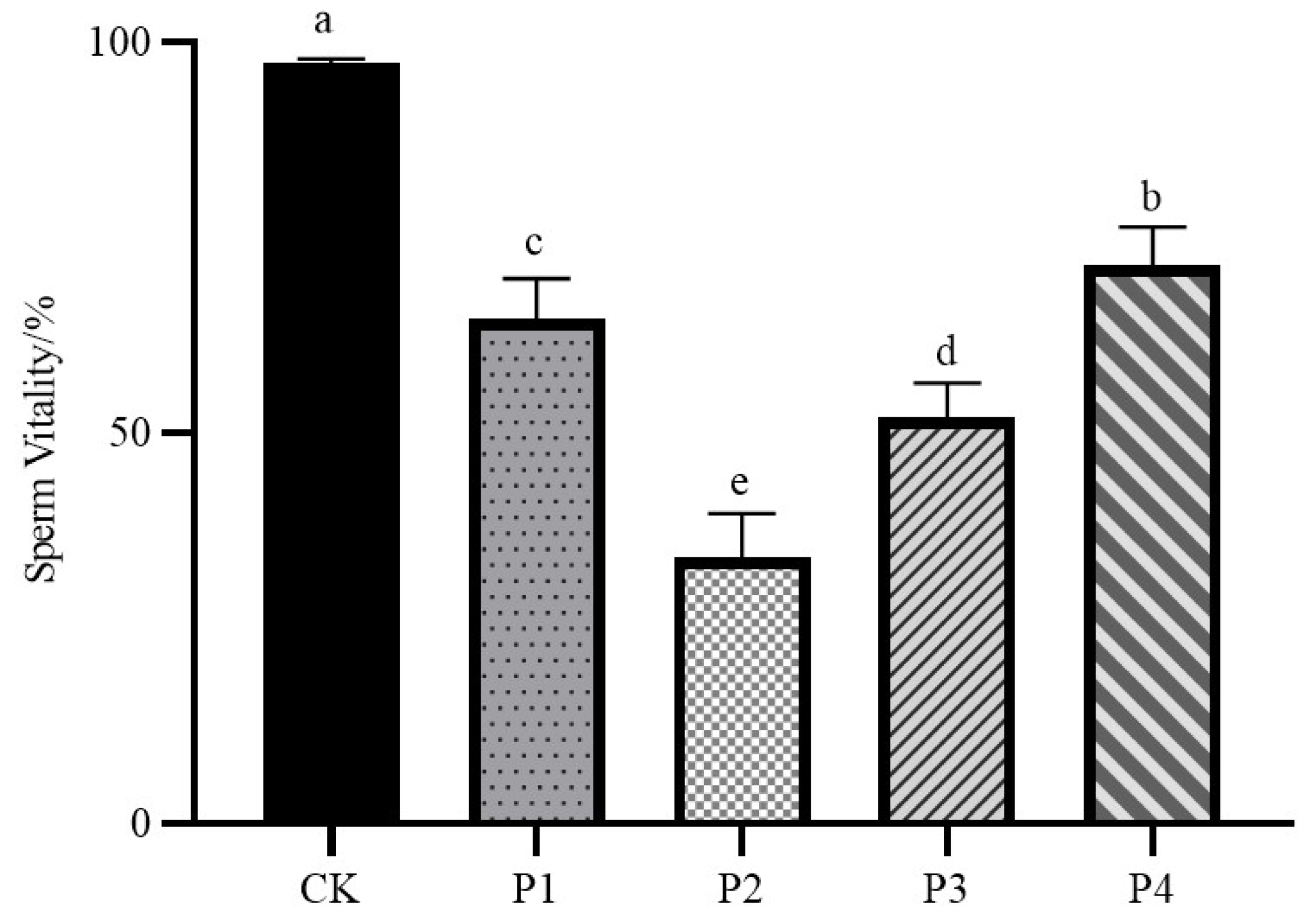

3.1. Sperm Vitality

As shown in

Figure 1, the sperm vitality of the fresh semen control group was 97.4%, which was significantly different from that of all four freezing procedure treatment groups (

P < 0.05); the sperm vitality of the P4 group was the highest among the four freezing procedure treatment groups, which was 71.41%; the sperm vitality of the P2 group was the lowest among the four freezing procedure treatment groups, which was 34.28%; and the mean sperm vitality of the P1 group and the P3 group were in the middle of the range, which were respectively were 65.56% and 53.41%, respectively.

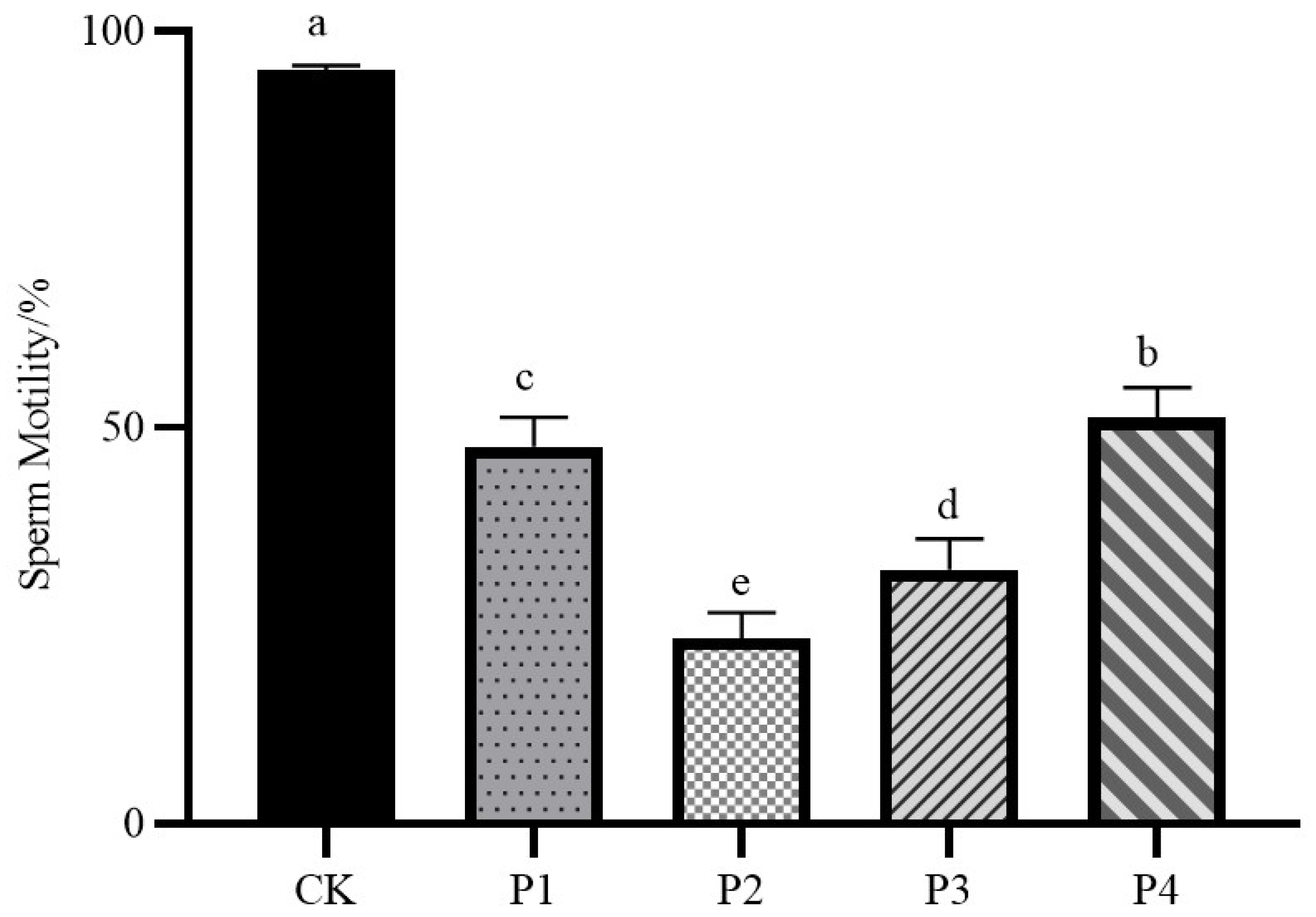

3.2. Sperm Motility

As shown in

Figure 2, the sperm motility of the fresh semen control group was 95.2%, which was significantly different from that of the four freezing procedure treatment groups (

P < 0.05); the sperm motility of the P4 group was the highest among the four freezing procedure treatment groups, 51.73%; the sperm motility of the P2 group was the lowest among the four freezing procedure treatment groups, 22.69%; and the sperm motility of the P1 group and the P3 group were in the middle of the average, respectively were 46.99% and 31.76%.

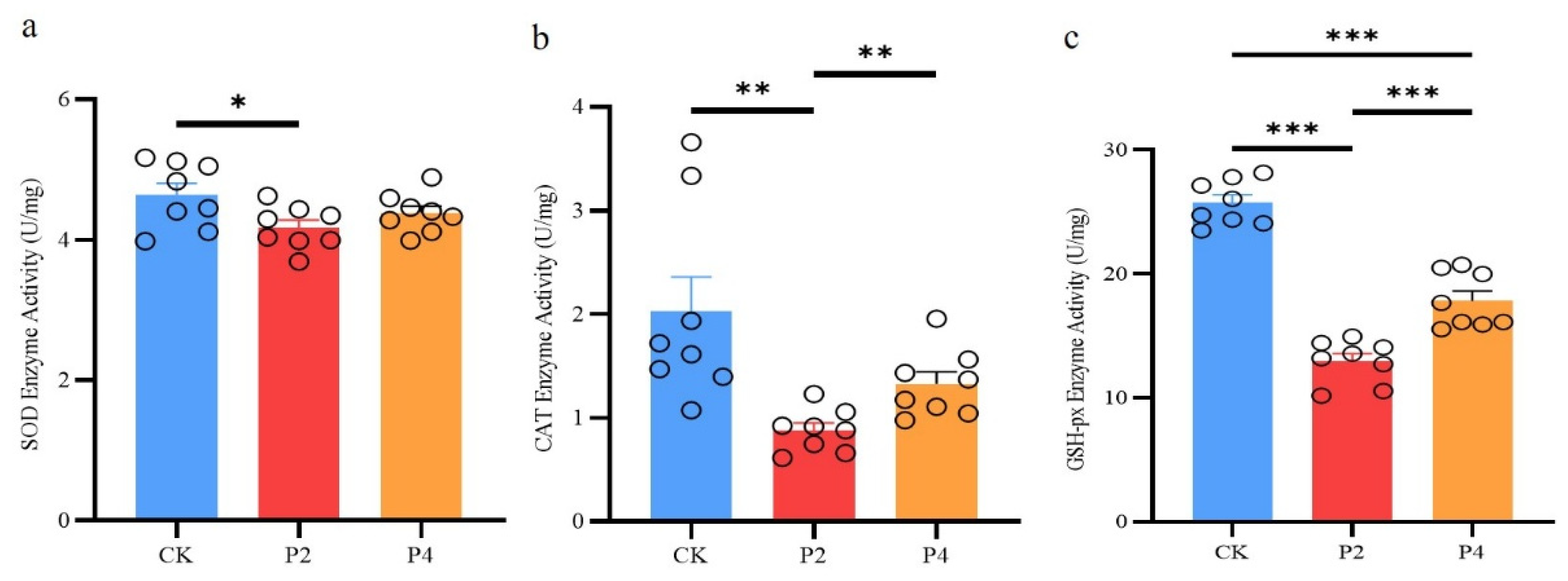

3.3. Superoxide Dismutase (SOD)

As shown in

Figure 3a, compared with the control group, the SOD activity was significantly reduced in the P2 group (

P < 0.05), while there was no significant difference in the P4 group (

P > 0.05).

3.4. Catalase (CAT)

As shown in

Figure 3b, CAT activity was significantly decreased in the P2 group (

P < 0.05) and not significantly altered in the P4 group when compared to the control group (

P > 0.05); but CAT activity was significantly increased in the P4 group when compared to the P2 group (

P < 0.05).

3.5. Glutathione Peroxidase (GSH-Px)

The results showed that GSH-Px activity was significantly decreased in both P2 and P4 groups compared to the control group, but GSH-Px activity in the P4 group was significantly higher than that in the P2 group (

P < 0.05) (

Figure 3c).

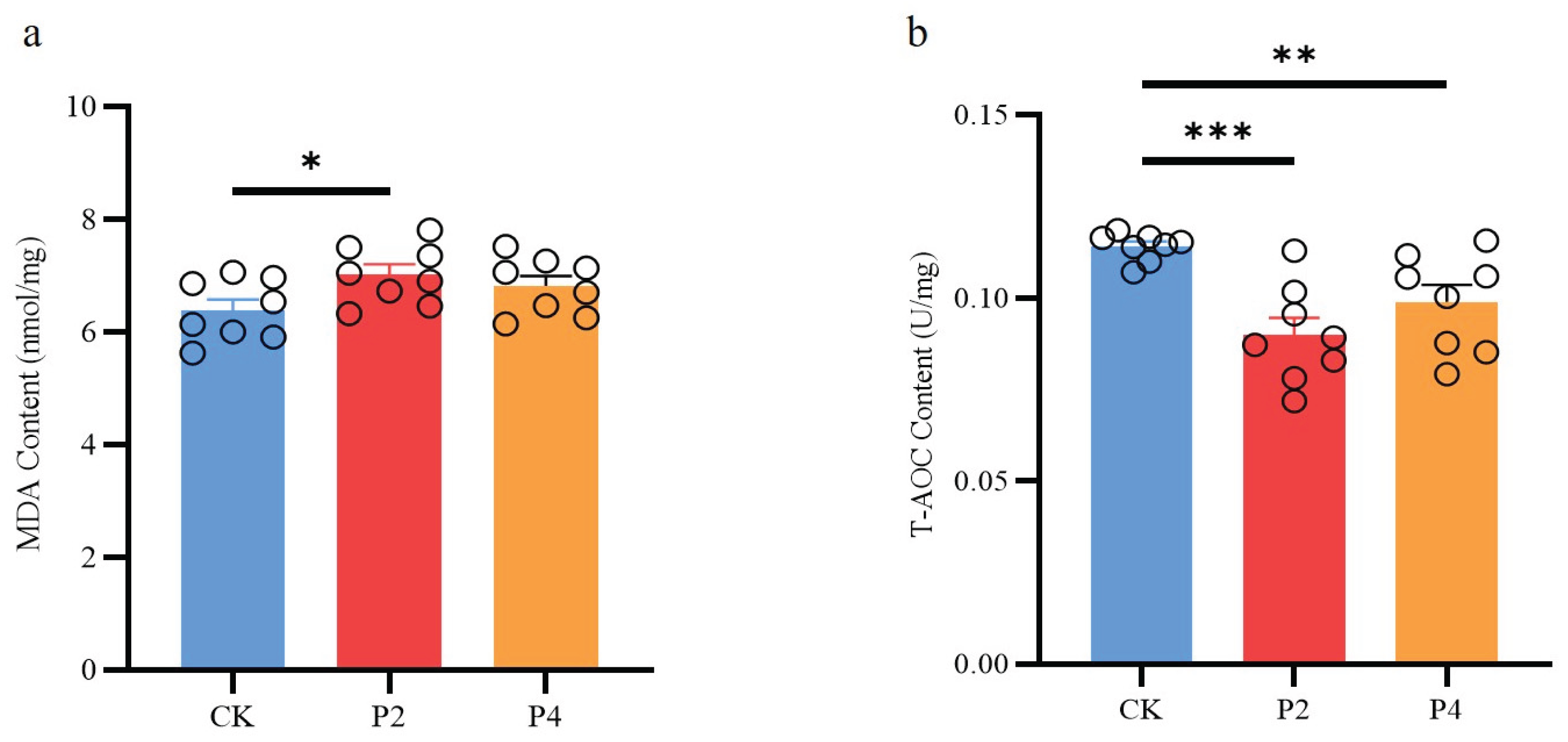

3.6. Malondialdehyde (MDA) and Total Antioxidant Capacity (T-AOC)

The results of this study showed that compared with the control group, the MDA level in the P2 group increased significantly (

P < 0.05), while there was no significant change in the P4 group (

P > 0.05) (

Figure 4a); the T-AOC content in both the P2 and P4 groups decreased significantly (

P < 0.05), but the decreasing trend in the P4 group was lower than that in the P2 group (

Figure 4b).

4. Discussion

In this study, we systematically compared the effects of four differentiated freezing procedures on sperm vitality, motility and oxidative stress indexes in Jinding ducks, revealing the critical roles of freezing rate and cooling strategy on sperm quality by modulating the oxidative stress pathway. The results confirmed that freezing program P4 performed optimally in maintaining sperm vitality and motility, while freezing program P2 led to a significant decrease in sperm vitality and motility. Physical and biochemical damage to spermatozoa during cryopreservation is a central factor in the reduction of their vitality [

15,

32]. Procedure P4 used a two-stage cooling strategy, with an initial slow descent to -35℃ at 7℃ /min followed by a rapid descent to -140℃ at 60℃ /min. This protocol achieved an optimized effect by balancing ice crystal generation with osmotic pressure damage. In the initial slow descent phase, the cells were gradually dehydrated to reduce the internal free water content, which in turn effectively inhibited ice crystal production; the subsequent rapid descent phase shortened the spermatozoa’s exposure to the hyperosmotic environment and reduced the risk of ROS accumulation, which is consistent with the optimization of the multi-stage variable temperature strategy in chicken and drake semen freezing studies [

7,

11]. Procedure P2 used a multi-stage slow descent, which, although aimed at avoiding cold shock, resulted in increased mitochondrial dysfunction due to prolonged exposure. Mitochondria, as the main source of ROS, undergo leakage of the electron transport chain by the absence of their membrane potential, causing the accumulation of superoxide anion (O

2−) [

33,

34,

35]. The results of the study showed that the P2 group had significantly higher MDA content and significantly lower activities of the antioxidant enzymes SOD, CAT and GSH-Px, suggesting that oxidative stress was the main driver of their sperm damage. In contrast, the MDA content of the P4 group did not change significantly and the CAT activity was significantly higher than that of the P2 group, suggesting that its cooling strategy effectively alleviated the lipid peroxidation reaction.

The synergistic effect of the cryoprotectant DMA should not be overlooked. DMA, as a permeable protectant, reduces cryoinjury by lowering the freezing point and stabilizing the membrane structure [

36,

37]. However, its protective effect is highly dependent on matching the cooling rate. The rapid terminal cooling of program P4 may reduce the interference of DMA with membrane lipids by shortening its contact time with spermatozoa and reducing its potential toxicity, whereas the slow-cooling process of program P2 may lead to over-permeation of DMA within the cell, triggering an osmotic pressure imbalance [

38]. In addition, sperm vitality in the P2 group was significantly lower than that in the chicken study, despite the use of a similar retardation protocol, which may be due to the fact that the plasma membrane of duck spermatozoa is rich in polyunsaturated fatty acids [

39], which are more sensitive to ROS attack.

The dynamic balance of the antioxidant system during the freezing process is crucial for sperm survival [

31]. But the capacity of sperm to synthesize antioxidants is limited [

40]. The antioxidant defense system basically relies on the enzymes present in seminal plasma. Among the main enzymes are glutathione peroxidase (GSH-Px), superoxide dismutase (SOD) and catalase (CAT) [

4]. In this study, we found that the SOD activity in the P4 group was not significantly different from that of fresh semen, suggesting that this freezing procedure effectively inhibited O

2- production; whereas the CAT activity was significantly higher than that in the P2 group, indicating that the scavenging ability of H

2O

2 was preserved. This result is consistent with the physiological function of the SOD-CAT cascade reaction [

41], in which SOD converts O

2- to H

2O

2 and oxygen [

42], and CAT or GSH-Px further breaks it down into harmless water and oxygen [

43]. However, GSH-Px activity remained significantly lower in the P4 group than in the control group, suggesting that the glutathione system may be difficult to fully recover during freezing. The regeneration of glutathione as an important non-enzymatic antioxidant depends on the supply of NADPH, and the mitochondrial dysfunction caused by freezing may limit the efficacy of this pathway [

44], and in the future, the addition of exogenous glutathione to the dilution solution may be considered to compensate for the lack of endogenous antioxidant system.

In summary, the present study confirmed that freezing procedures significantly affected the sperm quality of Jinding ducks by regulating the oxidative stress pathway, in which procedure P4 was outstanding in inhibiting ROS production and maintaining antioxidant enzyme activities due to its optimized cooling rate and staging strategy. This finding provides a reference for the standardization of duck semen cryopreservation technology, and helps to promote the conservation of waterfowl genetic resources and the industrial application of artificial insemination technology.

5. Conclusion

In this study, we evaluated the effects of four freezing procedures (P1-P4) on the cryopreservation effect and oxidative stress pathway of spermatozoa from Golding ducks. Program P4 (7°C/min slow descent to -35°C, followed by 60°C/min rapid descent to -140°C) was the most effective, significantly enhancing sperm quality, and its staged cooling strategy effectively reduced ROS accumulation, antioxidant enzyme activities, and mitigated lipid peroxidation damage. The study confirmed that P4 optimized the freezing effect by regulating the oxidative stress pathway, which provided a theoretical basis for the standardization of duck semen cryopreservation.

Author Contributions

Methodology, writing reviewing and editing, Zhicheng Wang; investigation, Haotian Gu; supervision, Chunhong Zhu; writing original draft preparation, Yifei Wang; visualization, Hongxiang Liu; data curation, Weitao Song; formal analysis, Zhiyun Tao; resources, Wenjuan Xu; project administration, Shuangjie Zhang; funding acquisition, Huifang Li. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This project was supported by the Natural Science Foundation of Yangzhou Municipality (YZ2023167), the JBGS Project of Seed Industry Revitalization in Jiangsu Province, China (JBGS [2021]111), the Open Fund of Jiangsu Provincial Key Laboratory of Poultry Genetic & Breeding (JQLAB-ZZ-202204), the Key R&D Program of Shandong Province, China (2024LZGCQY002).

Institutional Review Board Statement

This research plan has been approved by the Animal Protection and Utilization Committee of Jiangsu Poultry Science Institute (China; approval no. CAC-JIPS01342).

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data in this study can be obtained upon reasonable request to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank The National Germplasm Center of Domestic Animal Resources providing the experimental ducks. The authors also thank International Science Editing for the editing of this manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors state that there are no conflicts of interest.

References

- Taskin, A.; Ergun, D.; Ergun, F. Effects of different concentrations of honeysuckle (Lonicera iberica M. Bieb.) and barberry (Berberis vulgaris L.) extracts in cryopreserving of duck semen on sperm quality. Eur. Poult. Sci. (eps) 2023, 87, 16–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Li, Y.; Zong, Y.; Mehaisen, G.M.K.; Chen, J. Poultry genetic heritage cryopreservation and reconstruction: advancement and future challenges. J. Anim. Sci. Biotechnol. 2022, 13, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Telnoni, S.P.; Dilak, H.I.; Arifiantini, I.; Nalley, W.M. Manila duck (Cairina moschata) frozen semen quality in lactated ringer’s egg yolk-astaxanthin with different concentrations of DMSO. Anim. Reprod. 2024, 21, e20230015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yánez-Ortiz, I.; Catalán, J.; Rodríguez-Gil, J.E.; Miró, J.; Yeste, M. Advances in sperm cryopreservation in farm animals: Cattle, horse, pig and sheep. Anim. Reprod. Sci. 2022, 246, 106904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oldenhof H, Wolkers WF, Sieme H. Cryopreservation of Semen from Domestic Livestock: Bovine, Equine, and Porcine Sperm. Cryopreservation and Freeze-Drying Protocols. Methods in Molecular Biology 2021. p. 365-77.

- Partyka, A.; Niżański, W. Advances in storage of poultry semen. Anim. Reprod. Sci. 2022, 246, 106921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janosikova, M.; Petricakova, K.; Ptacek, M.; Savvulidi, F.G.; Rychtarova, J.; Fulka, J. New approaches for long-term conservation of rooster spermatozoa. Poult. Sci. 2022, 102, 102386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zong, Y.; Li, Y.; Sun, Y.; Mehaisen, G.M.K.; Ma, T.; Chen, J. Chicken Sperm Cryopreservation: Review of Techniques, Freezing Damage, and Freezability Mechanisms. Agriculture 2023, 13, 445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tselutin, K.; Seigneurin, F.; Blesbois, E. Comparison of cryoprotectants and methods of cryopreservation of fowl spermatozoa. Poult. Sci. 1999, 78, 586–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zong, Y.; Li, Y.; Sun, Y.; Han, X.; Yuan, J.; Ma, L.; Ma, H.; Chen, J. Mitochondrial aspartate aminotransferase (GOT2) protein as a potential cryodamage biomarker in rooster spermatozoa cryopreservation. Poult. Sci. 2024, 104, 104690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, M.; Cao, J.; Yu, Z.; Liu, H.; Yang, F.; Huang, S.; He, J.; Yan, H. New semen freezing method for chicken and drake using dimethylacetamide as the cryoprotectant. Poult. Sci. 2021, 100, 101091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olexikova, L.; Miranda, M.; Kulikova, B.; Baláži, A.; Chrenek, P. Cryodamage of plasma membrane and acrosome region in chicken sperm. Anat. Histol. Embryol. 2018, 48, 33–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thananurak, P.; Chuaychu-Noo, N.; Phasuk, Y.; Vongpralub, T. Comparison of TNC and standard extender on post-thaw quality and in vivo fertility of Thai native chicken sperm. Cryobiology 2020, 92, 197–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mehaisen, G.M.; Partyka, A.; Ligocka, Z.; Niżański, W. Cryoprotective effect of melatonin supplementation on post-thawed rooster sperm quality. Anim. Reprod. Sci. 2020, 212, 106238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohammad, M.S.; Mardenli, O.; Al-Tawash, A.S.A. Evaluation of The Cryopreservation Technology of Poultry Sperm: A Review Study. IOP Conference Series Earth and Environmental Science 2021, 735, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zong, Y.; Sun, Y.; Li, Y.; Mehaisen, G.M.; Yuan, J.; Ma, H.; Ni, A.; Wang, Y.; Hamad, S.K.; Elomda, A.M.; et al. Effect of glycerol concentration, glycerol removal method, and straw type on the quality and fertility of frozen chicken semen. Poult. Sci. 2022, 101, 101840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazur, P. Freezing of living cells: mechanisms and implications. Am. J. Physiol. Physiol. 1984, 247, C125–C142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feyzi, S.; Sharafi, M.; Rahimi, S. Stress preconditioning of rooster semen before cryopreservation improves fertility potential of thawed sperm. Poult. Sci. 2018, 97, 2582–2590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masoudi, R.; Sharafi, M.; Shahneh, A.Z.; Kohram, H.; Nejati-Amiri, E.; Karimi, H.; Khodaei-Motlagh, M.; Shahverdi, A. Supplementation of extender with coenzyme Q10 improves the function and fertility potential of rooster spermatozoa after cryopreservation. Anim. Reprod. Sci. 2018, 198, 193–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salih, S.A.; Daghigh-Kia, H.; Mehdipour, M.; Najafi, A. Does ergothioneine and thawing temperatures improve rooster semen post-thawed quality? Poult. Sci. 2021, 100, 101405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Najafi, A.; Mehdipour, M.; Mohammadi, H.; Mehdipour, Z.; Khorrami, B.; Nazari, M. Effect of tempol and straw size on rooster sperm quality and fertility after post-thawing. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahin, M.A.; Khalil, W.A.; Saadeldin, I.M.; Swelum, A.A.-A.; El-Harairy, M.A. Comparison between the Effects of Adding Vitamins, Trace Elements, and Nanoparticles to SHOTOR Extender on the Cryopreservation of Dromedary Camel Epididymal Spermatozoa. Animals 2020, 10, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmed, H.; Jahan, S.; Riaz, M.; Ijaz, M.U.; Wahab, A. Improving the quality and in vitro fertilization rate of frozen-thawed semen of buffalo (Bubalus bubalis) bulls with the inclusion of vitamin B12 in the cryopreservation medium. Anim. Reprod. Sci. 2021, 229, 106761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, JA. Avian semen cryopreservation: what are the biological challenges? Poultry Science. 2006, 85, 232–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamali Sangani A, Masoudi AA, Vaez Torshizi R. Association of mitochondrial function and sperm progressivity in slow- and fast-growing roosters. Poultry Science. 2017, 96, 211–9. [CrossRef]

- Mehdipour, M.; Kia, H.D.; Martínez-Pastor, F. Poloxamer 188 exerts a cryoprotective effect on rooster sperm and allows decreasing glycerol concentration in the freezing extender. Poult. Sci. 2020, 99, 6212–6220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Najafi, A.; Kia, H.D.; Mehdipour, M.; Hamishehkar, H.; Álvarez-Rodríguez, M. Effect of quercetin loaded liposomes or nanostructured lipid carrier (NLC) on post-thawed sperm quality and fertility of rooster sperm. Theriogenology 2020, 152, 122–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Najafi, A.; Mohammadi, H.; Sharifi, S.D.; Rahimi, A. Apigenin supplementation substantially improves rooster sperm freezability and post-thaw function. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Masoudi, R.; Asadzadeh, N.; Sharafi, M. Effects of freezing extender supplementation with mitochondria-targeted antioxidant Mito-TEMPO on frozen-thawed rooster semen quality and reproductive performance. Anim. Reprod. Sci. 2021, 225, 106671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rui, B.R.; Shibuya, F.Y.; Kawaoku, A.J.; Losano, J.D.; Angrimani, D.S.; Dalmazzo, A.; Nichi, M.; Pereira, R.J. Impact of induced levels of specific free radicals and malondialdehyde on chicken semen quality and fertility. Theriogenology 2017, 90, 11–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leão, A.P.A.; de Souza, A.V.; Mesquita, N.F.; Pereira, L.J.; Zangeronimo, M.G. Antioxidant enrichment of rooster semen extenders – A systematic review. Res. Veter- Sci. 2021, 136, 111–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le MT, Nguyen TTT, Nguyen TT, Nguyen TV, Nguyen TAT, Nguyen QHV, et al. Does conventional freezing affect sperm DNA fragmentation? Clinical and Experimental Reproductive Medicine. 2019, 46, 67–75. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rizwan, H.; Pal, S.; Sabnam, S.; Pal, A. High glucose augments ROS generation regulates mitochondrial dysfunction and apoptosis via stress signalling cascades in keratinocytes. Life Sci. 2020, 241, 117148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Masoudi, R.; Sharafi, M.; Pourazadi, L. Improvement of rooster semen quality using coenzyme Q10 during cooling storage in the Lake extender. Cryobiology 2019, 88, 87–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ighodaro, O.M.; Akinloye, O.A. First line defence antioxidants-superoxide dismutase (SOD), catalase (CAT) and glutathione peroxidase (GPX): Their fundamental role in the entire antioxidant defence grid. Alex. J. Med. 2018, 54, 287–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seifi-Jamadi, A.; Ahmad, E.; Ansari, M.; Kohram, H. Antioxidant effect of quercetin in an extender containing DMA or glycerol on freezing capacity of goat semen. Cryobiology 2017, 75, 15–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laura, Y.; Harimurti, S. Effect of Different Levels of Dimethylacetamide (DMA) on Sperm Quality of Bangkok Rooster Chicken and Sperm Survivability in Reproductive Tract of Hen. Pak. J. Nutr. 2017, 16, 144–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holt, W. Basic aspects of frozen storage of semen. Anim. Reprod. Sci. 2000, 62, 3–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Surai, P.; Blesbois, E.; Grasseau, I.; Chalah, T.; Brillard, J.-P.; Wishart, G.; Cerolini, S.; Sparks, N. Fatty acid composition, glutathione peroxidase and superoxide dismutase activity and total antioxidant activity of avian semen. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. Part B: Biochem. Mol. Biol. 1998, 120, 527–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortega-Ferrusola C, Martin Muñoz P, Ortiz-Rodriguez JM, Anel-López L, Balao da Silva C, Álvarez M, et al. Depletion of thiols leads to redox deregulation, production of 4-hydroxinonenal and sperm senescence: a possible role for GSH regulation in spermatozoa. Biology of Reproduction 2019, 100, 1090–107.

- Ancuelo AE, Landicho MM, Dichoso GA, Sangel PP. Superoxide Dismutase (SOD) Activity in Cryopreserved Semen of Itik Pinas-Khaki (Anas platyrhynchos L.). Tropical Animal Science Journal. 2021, 44, 138–45.

- Partyka, A.; Łukaszewicz, E.; Niżański, W. Lipid peroxidation and antioxidant enzymes activity in avian semen. Anim. Reprod. Sci. 2012, 134, 184–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Surai F, P. Antioxidant Systems in Poultry Biology: Superoxide Dismutase. Journal of Animal Research and Nutrition 2016, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilodeau, J.-F.; Blanchette, S.; Gagnon, C.; Sirard, M.-A. Thiols prevent H2O2-mediated loss of sperm motility in cryopreserved bull semen. Theriogenology 2001, 56, 275–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).