Submitted:

14 June 2025

Posted:

17 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Key Points

- Accurate Antarctic backscattering measurements with unwarmed instruments were limited to periods of minimal icing and low frazil content

- Accurate frazil characterization requires algorithms compatible with measured backscattering data and ice’s elastic solid rheology

- Valid Icing-free period characterizations and data on instrument depth and backscattering strength imply maximal evening/morning frazil growth

1. Introduction

2. Methods and Data

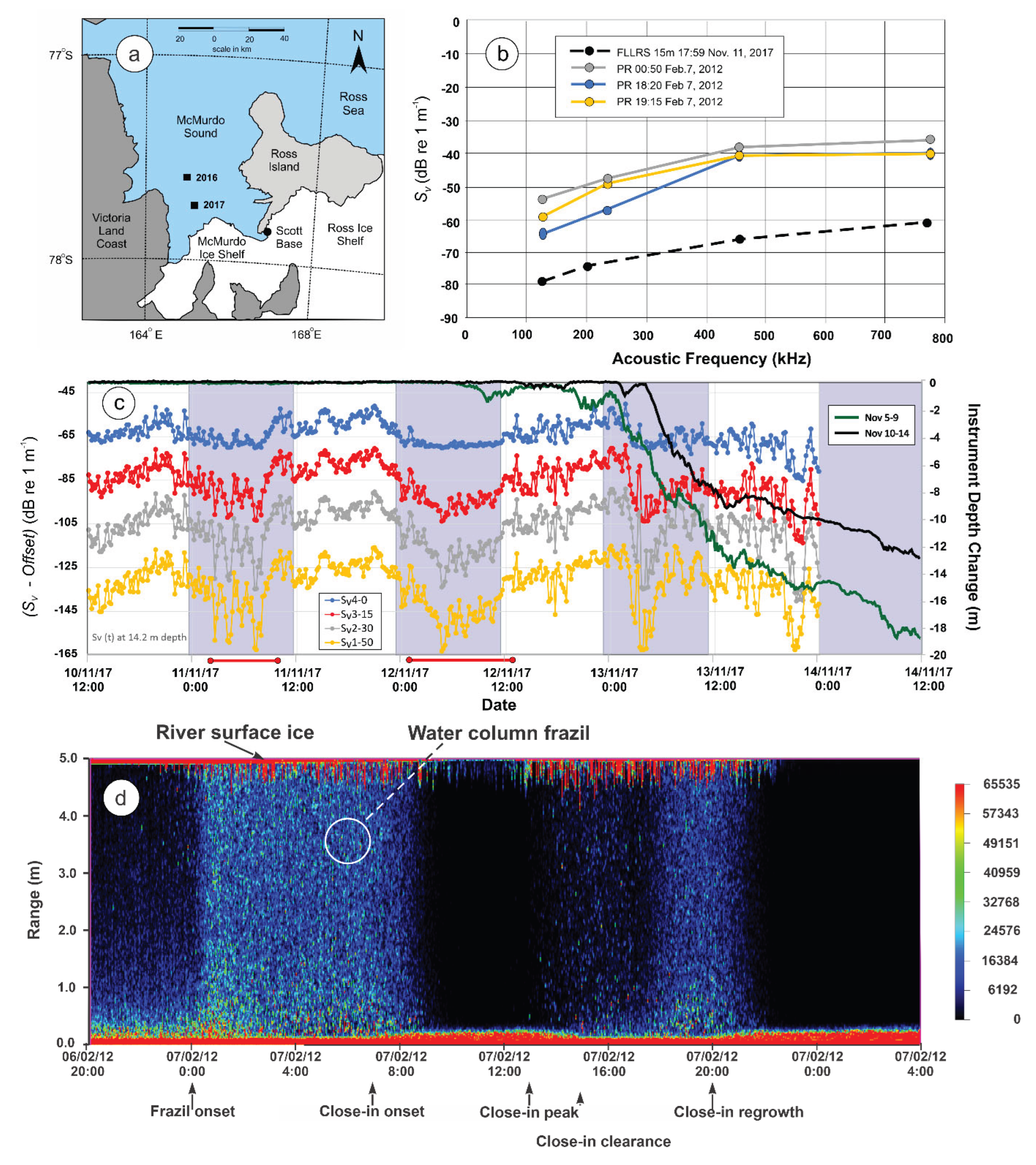

2.1. Basic Elements of the Frazer et al. Study

2.2. Potential Data Anomalies

2.3. Acoustic Backscattering Measurements in Rivers: Relevance to Frazer et al. (2020) Results

3. Analyses

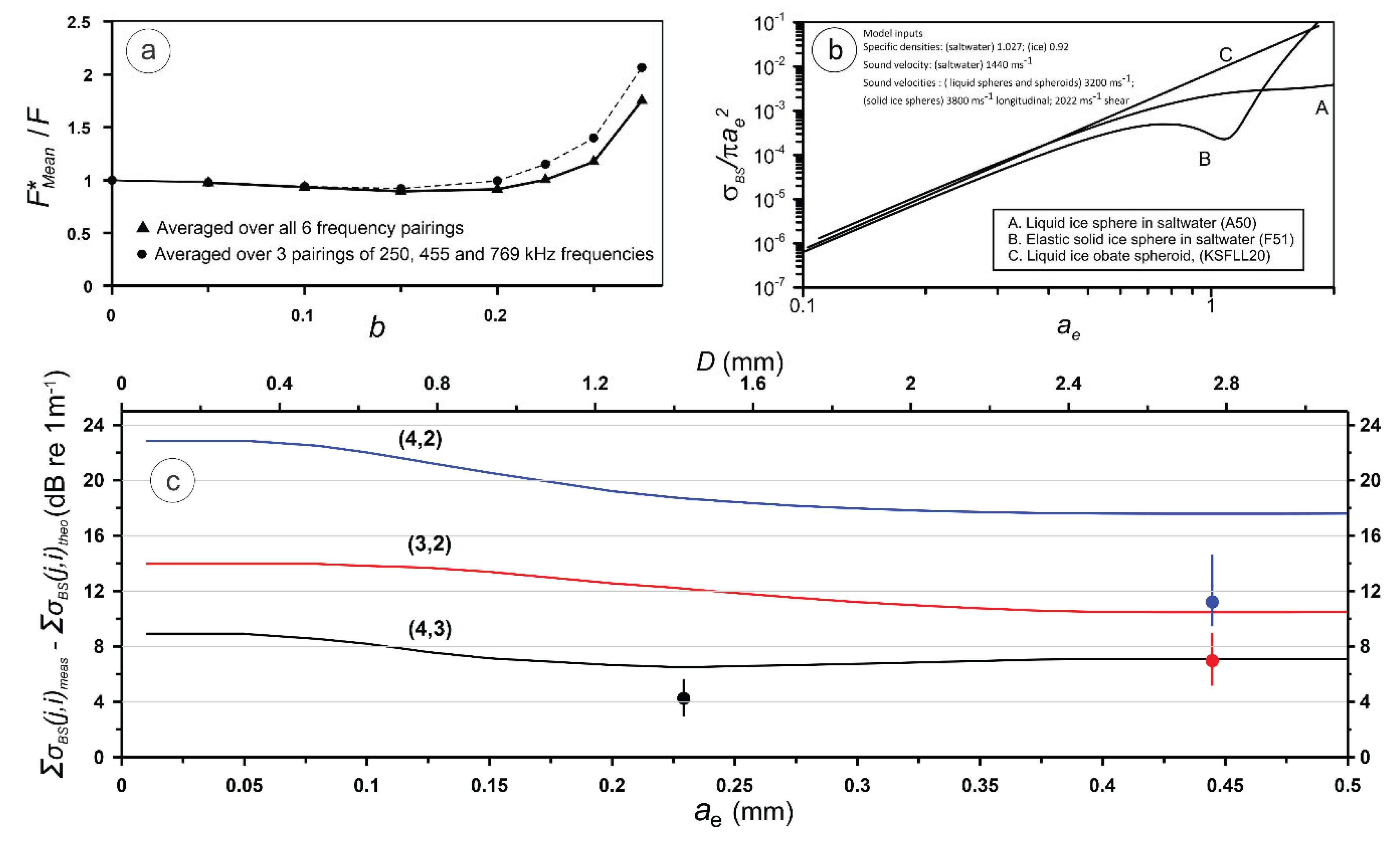

3.1. Evaluations of Frazil Content Estimation Algorithms

3.2. Evaluating the Kungl et al., (2020) Characterization Algorithm

4. Results

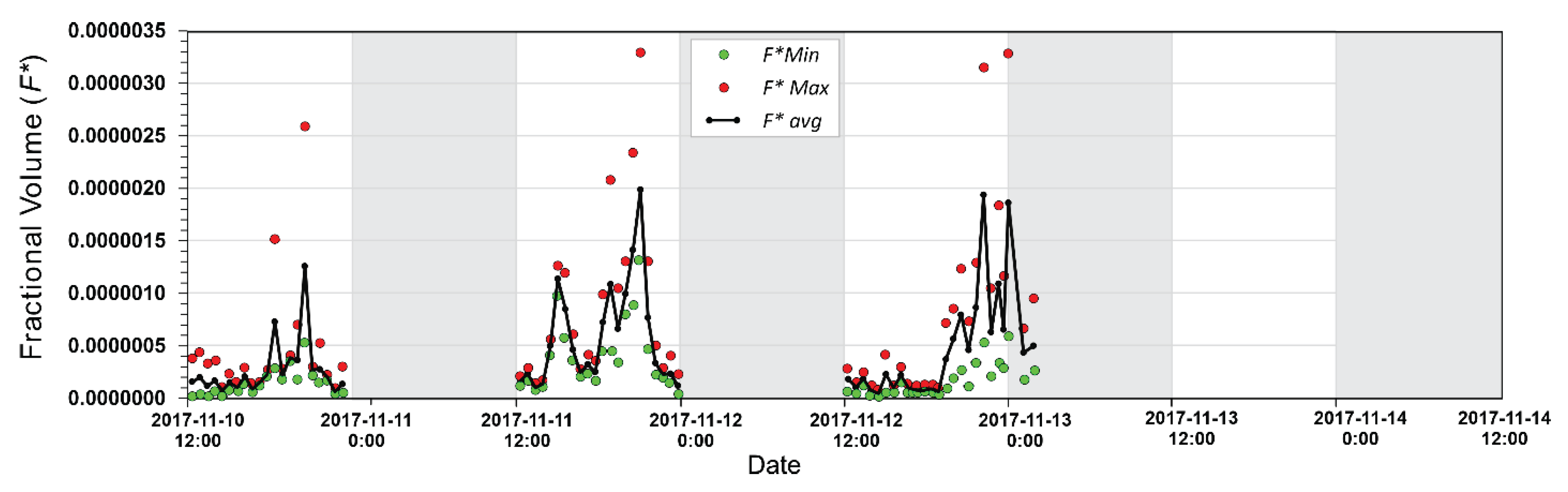

4.1. Recalculated Postnoon Frazil Fractional Volumes

4.2. Implications for Daily Frazil Production

5. Summary and Conclusions

References

- Ashton, G.D. (1986). Frazil ice. In: Theory of Multiphase Flow, Academic Press N.Y., 271-289.

- Anderson, V.C. (1950). Sound scattering from a fluid sphere. J. Acoust. Soc., 22, 426-431. [CrossRef]

- Burke, J.E. (1968). Scattering by penetrable spheroids, J. Acoust. Soc., 43, 871–875. [CrossRef]

- Daly, S.F. (1984). Frazil ice dynamics. USACE CRREL Monograph 84-1, Hanover, NH. 86 p.

- Faran, J.J. Jr. (1951). Sound scattering by solid cylinders and spheres. J. Acoust. Soc., 23, 405-418. [CrossRef]

- Frazer, E. K, Langhorne, P.J., Leonard, G.H., Robinson, N.J., & Schumayer, D. (2020). Observations of the size of frazil ice in an ice shelf waterplume. Geophysical Research Letters, 47 e2020/GL090498. [CrossRef]

- Ghobrial. T.R., Loewen, M.R. & Hicks, F.E. (2012). Characterizing suspended frazil ice in rivers using upward looking sonars. Cold Reg. Sci Technol. 86, 113-126. [CrossRef]

- Ghobrial. T.R. & Loewen, M.R. (2021). Continuous in situ measurements of anchor ice formation, growth, and release The Cryosphere, 15, 49–67 . [CrossRef]

- Hay, A. E, and Sheng, J. 1992: Vertical profiles of suspended sand concentrations and size from multifrequency acoustic backscatter. J. Geophys. Res. 97 (10), pp 1566-1567. [CrossRef]

- Hughes, K. G., Langhorne, P. J., Leonard, G. H., & Stevens, C. L. (2014). Extension of an Ice Shelf Water plume model beneath sea ice with application in McMurdo Sound, Antarctica. Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans, 119, 8662–8687. [CrossRef]

- Kungl, A.F., Schumayer, D., Frazer, E.K., Langhorne,& P.J., Leonard, G.H. (2020). An oblate spheroid model for multi-frequency acoustic back-scattering of frazil ice. Cold Regions Science and Technology 177 (2020)103122. [CrossRef]

- Langhorne,P.J., Hughes, K. G., Gough, A. J., Smith, I. J., Williams, M. J. M., Robinson, N. J., & Haskell, T. G. (2015). Observed platelet ice distributions in Antarctic sea ice: An index for ocean-ice shelf heat flux. Geophysical Research Letters, 42, 5442–5451. [CrossRef]

- Lewis, E. L., & Perkin, R. G. (1985). The winter oceanography of McMurdo Sound, Antarctica. Oceanology of the Antarctic Continental Shelf, 145–165, American Geophysical Union, . [CrossRef]

- Lewis, E. L., & Perkin, R. G. (1986). Ice pumps and their rates. Journal of Geophysical Research, 91(C10), 11756. [CrossRef]

- Marko, J.R. & Jasek, M. (2010a). Sonar detection and measurements of ice in a freezing river I: Methods and data characteristics. Cold Reg. Sci. Technol. 63, 121-134. [CrossRef]

- Marko, J.R. & Jasek, M. (2010b). Sonar detection and measurements of ice in a freezing river II: Observations and results on frazil ice. Cold Reg. Sci. Technol. 63, 135-153. [CrossRef]

- Marko, J. R., Jasek, M., & Topham, D. R. (2015). Multifrequency analyses of 2011–2012 Peace River SWIPS frazil backscattering data. Cold Regions Science and Technology, 110, 102–119. [CrossRef]

- Marko, J. R. & Topham, D.R. (2015). Laboratory measurements of acoustic backscattering from polystyrene pseudo- ice particles as a basis for quantitative frazil characterization. Cold Reg. Sci. Technol. 112, 66-86. [CrossRef]

- Marko, J. R. & Topham, D.R. (2021).Analyses of Peace River shallow water ice profiling sonar data and their implications for the roles played by frazil ice and in situ ice growth in freezing rivers. The Cryosphere, 15, 2473-2489. [CrossRef]

- McFarlane, V., Loewen, M., & Hicks, F. (2014). Laboratory measurements of the rise velocity of frazil ice particles. Cold Regions Science and Technology, 106–107, 120–130. [CrossRef]

- McFarlane, V., Loewen, M. & Hicks, F. (2017). Measurements of the size distributions of frazil ice particles in three Alberta rivers. Cold Reg. Sci. Technol. 142, 100-117. [CrossRef]

- Pietrovich, V.V. (1956). Formation of depth-ice. Translated from Priroda 9: 94-95 by Defense Research Board, D,S.J.S., Department of National Defense, Canada, T235R.

- Robinson, N. J., Leonard, G., Frazer, E., Langhorne, P., Grant, B., Stewart, C., & De Joux, P. (2020): Temperature, salinity and acoustic backscatter observations and tidal model output in McMurdo Sound, Antarctica in 2016 and 2017 - links to original files [Dataset]. PANGAEA, . [CrossRef]

- Smedsrud, L. H., & Jenkins, A. (2004). Frazil ice formation in an ice shelf water plume. Journal of Geophysical Research, 109, C03025. [CrossRef]

- Stanton, T.K, Wiebe, P.H., Chu, D. (1998). Differences between sound scattering by weakly scattering spheres and finite-length cylinders with applications to sound scattering by zooplankton. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 103 (1). https://doi.org:10.1029/92JC01240.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).