Submitted:

16 June 2025

Posted:

17 June 2025

Read the latest preprint version here

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

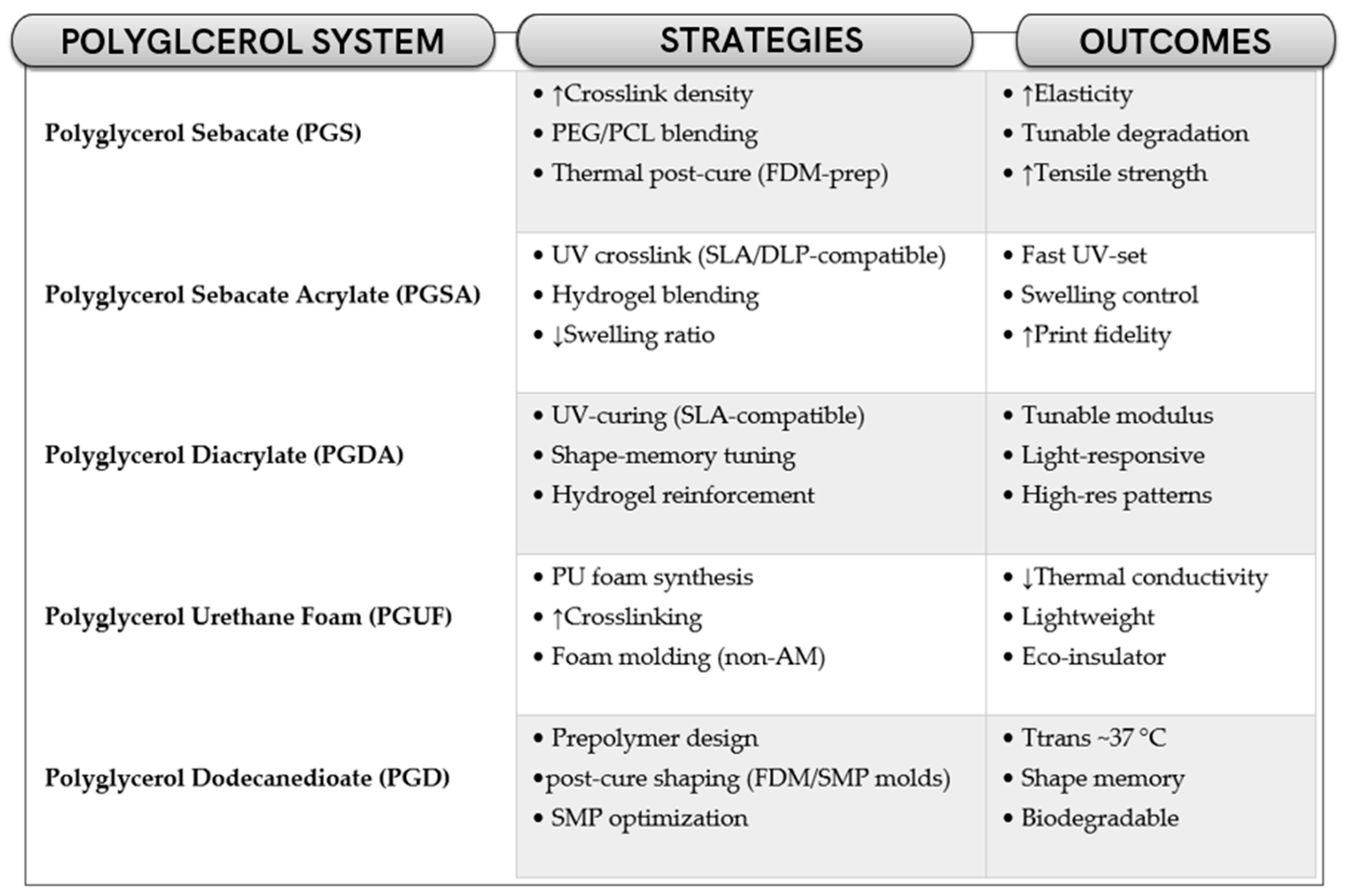

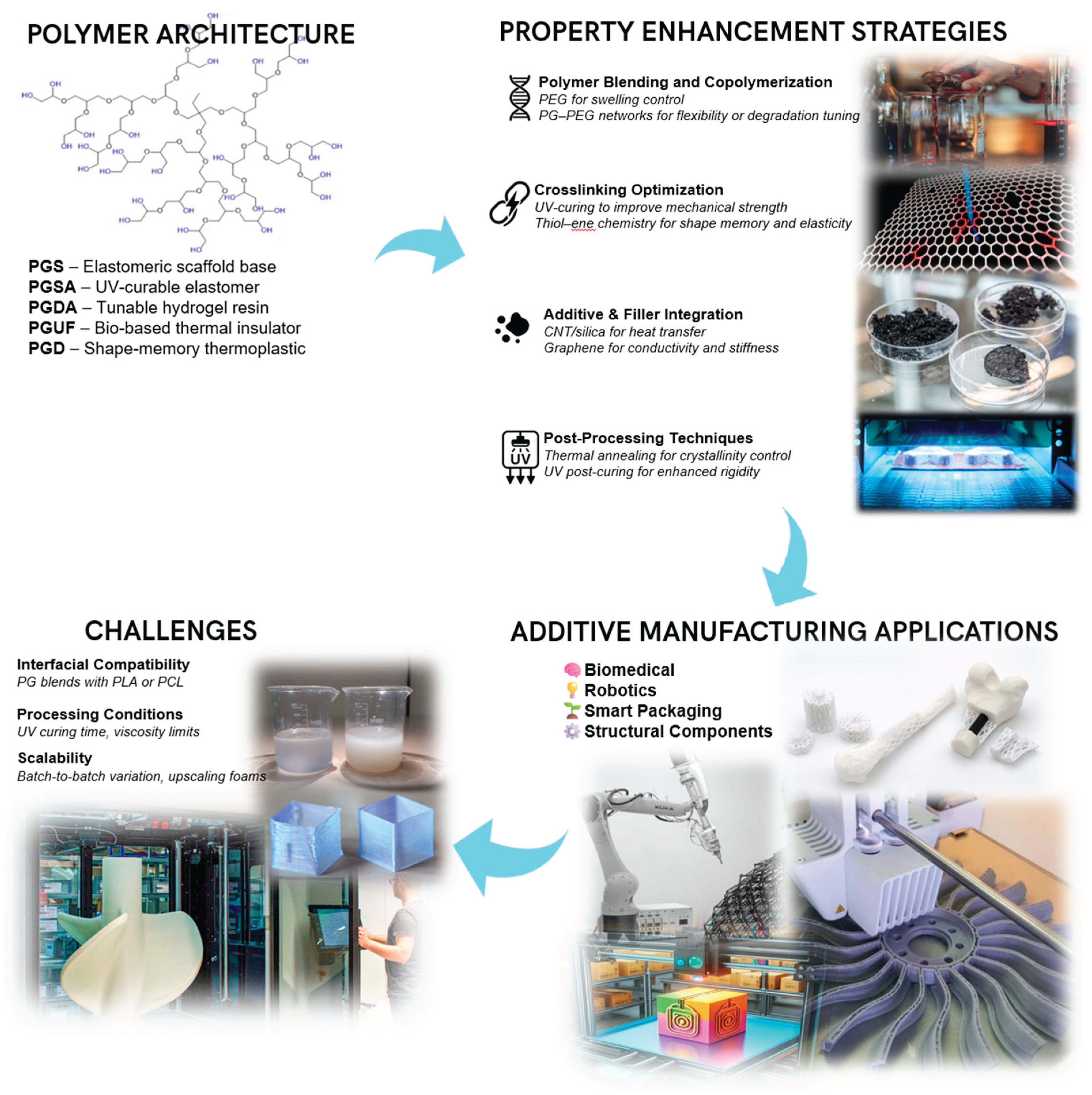

2. Structure–Property Relationships in a Polyglycerol System

2.1. Overview of Linear, Hyperbranched, and Dendritic Architectures

2.2. Molecular Weight, Branching, and Functional Group Influence on Modulus, Toughness, and Glass Transition Temperature

2.3. Strategies to Enhance Mechanical Strength: Crosslinking, Copolymerization, and Filler Addition

3. Thermal Stability and Processing Considerations

3.1. Thermal Decomposition Profiles

3.2. Suitability for High-Temperature Printing Platforms

3.3. Fire Retardancy and Insulation Potential

4. Mechanical Performance in 3D Printed Forms

4.1. Mechanical Properties in AM

4.2. Influence of Printing Parameters on Anisotropy and Layer Bonding

4.3. Comparative Performance with PLA, PCL, PEGDA, and Other Polymers

4.4. Shape Retention, Creep Resistance, and Dynamic Loading Performance

5. Structural and Functional Enhancements

5.1. Reinforcement with Inorganic Filler

5.1.1. Silica Reinforcement

5.1.2. Graphene Reinforcement

5.1.3. Nanoclay Reinforcement

5.1.4. Effects of Hybrid Reinforcement

5.2. Dual-Network Systems (DNS) and Interpenetrating Polymer Networks (IPNs)

5.3. Mechanically Adaptive Polyglycerol Networks

5.4. Interface Engineering in Multi-Material Printing

6. Case Studies and Applications

6.1. Printed Structural Scaffolds with Load-Bearing Potential

6.2. PG-based thermal insulating panels

6.3. Soft Robotics and Actuators Requiring Elasticity and Temperature Resilience

6.4. Printable Adhesives and Damping Components

7. Challenges and Opportunities

7.1. Processing–Performance Tradeoffs

7.2. Poor Thermal Conductivity vs. Insulation Needs

7.3. Engineering Crystallinity or Semi-Crystalline Domains

7.4. Summary of Design Strategies and Pathways

7.5. Future Directions: High-Throughput Synthesis, Computational Design, and Hybrid Architectures

8. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Advincula, R.C.; Dizon, J.R.C.; Caldona, E.B.; Viers, R.A.; Siacor, F.D.C.; Maalihan, R.D.; Espera, A.H. On the Progress of 3D-Printed Hydrogels for Tissue Engineering. MRS Communications 2021, 11, 539–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baumers, M.; Beltrametti, L.; Gasparre, A.; Hague, R. Informing Additive Manufacturing Technology Adoption: Total Cost and the Impact of Capacity Utilisation. 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fritschle, T.; Kaess, M.; Weihe, S.; Werz, M. Investigation of the Thermo-Mechanical Modeling of the Manufacturing of Large-Scale Wire Arc Additive Manufacturing Components with an Outlook Towards Industrial Applications. JMMP 2025, 9, 166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maalihan, R.D. Modelling the Toughness of Nanostructured Polyhedral Oligomeric Silsesquioxane Composites Fabricated by Stereolithography 3D Printing: A Response Surface Methodology and Artificial Neural Network Approach. MSF 2022, 1053, 41–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maalihan, R.D.; Briones, L.I.B.; Canarias, E.P.; Lanuza, G.P. On the 3D Printing and Flame Retardancy of Expandable Graphite-Coated Polylactic Acid. Materials Today: Proceedings 2023, S2214785323048125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maalihan, R.D.; Aggari, J.C.V.; Alon, A.S.; Latayan, R.B.; Montalbo, F.J.P.; Javier, A.D. On the Optimized Fused Filament Fabrication of Polylactic Acid Using Multiresponse Central Composite Design and Desirability Function Algorithm. Proceedings of the Institution of Mechanical Engineers, Part E: Journal of Process Mechanical Engineering 2024, 09544089241247454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calabia, R.O.A.; Gomez, J.E.D.; Lasala, I.M.; Ligsay, C.M.A.; Maalihan, R.D.; Aquino, A.P.; Sangalang, R.H. Epoxidised Philippine Natural Rubber for Tough and Versatile 3D Printable Resins: A Mixture Design and Neural Network Approach. J Rubber Res 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.; Miller, J.; Vezza, J.; Mayster, M.; Raffay, M.; Justice, Q.; Al Tamimi, Z.; Hansotte, G.; Sunkara, L.D.; Bernat, J. Additive Manufacturing: A Comprehensive Review. Sensors 2024, 24, 2668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riccio, C.; Civera, M.; Grimaldo Ruiz, O.; Pedullà, P.; Rodriguez Reinoso, M.; Tommasi, G.; Vollaro, M.; Burgio, V.; Surace, C. Effects of Curing on Photosensitive Resins in SLA Additive Manufacturing. Applied Mechanics 2021, 2, 942–955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos, A.; Angel, V.G.; Siqueiros, M.; Sahagun, T.; Gonzalez, L.; Ballesteros, R. Reviewing Additive Manufacturing Techniques: Material Trends and Weight Optimization Possibilities Through Innovative Printing Patterns. Materials 2025, 18, 1377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porcarello, M.; Bonardd, S.; Kortaberria, G.; Miyaji, Y.; Matsukawa, K.; Sangermano, M. 3D Printing of Electrically Conductive Objects with Biobased Polyglycerol Acrylic Monomers. ACS Appl. Polym. Mater. 2024, 6, 2868–2876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeh, Y.-C.; Highley, C.B.; Ouyang, L.; Burdick, J.A. 3D Printing of Photocurable Poly(Glycerol Sebacate) Elastomers. Biofabrication 2016, 8, 045004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruther, F.; Roether, J.A.; Boccaccini, A.R. 3D Printing of Mechanically Resistant Poly (Glycerol Sebacate) (PGS)-Zein Scaffolds for Potential Cardiac Tissue Engineering Applications. Adv Eng Mater 2022, 24, 2101768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atari, M.; Labbaf, S.; Javanmard, S.H. Fabrication and Characterization of a 3D Scaffold Based on Elastomeric Poly-Glycerol Sebacate Polymer for Heart Valve Applications. Journal of Manufacturing Processes 2023, 102, 350–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pouyan, P.; Cherri, M.; Haag, R. Polyglycerols as Multi-Functional Platforms: Synthesis and Biomedical Applications. Polymers 2022, 14, 2684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fijten, M.W.M.; Kranenburg, J.M.; Thijs, H.M.L.; Paulus, R.M.; Van Lankvelt, B.M.; De Hullu, J.; Springintveld, M.; Thielen, D.J.G.; Tweedie, C.A.; Hoogenboom, R.; Van Vliet, K.J.; Schubert, U.S. Synthesis and Structure−Property Relationships of Random and Block Copolymers: A Direct Comparison for Copoly(2-Oxazoline)s. Macromolecules 2007, 40, 5879–5886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, E.; Robson, A.J.; Crisp, A.R.; Cockshell, M.P.; Burzava, A.L.S.; Ganesan, R.; Robinson, N.; Al-Bataineh, S.; Nankivell, V.; Sandeman, L.; Tondl, M.; Benveniste, G.; Finnie, J.W.; Psaltis, P.J.; Martocq, L.; Quadrelli, A.; Jarvis, S.P.; Williams, C.; Ramage, G.; Rehman, I.U.; Bursill, C.A.; Simula, T.; Voelcker, N.H.; Griesser, H.J.; Short, R.D.; Bonder, C.S. Study of the Structure of Hyperbranched Polyglycerol Coatings and Their Antibiofouling and Antithrombotic Applications. Adv Healthcare Materials 2024, 2401545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khandare, J.; Mohr, A.; Calderón, M.; Welker, P.; Licha, K.; Haag, R. Structure-Biocompatibility Relationship of Dendritic Polyglycerol Derivatives. Biomaterials 2010, 31, 4268–4277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zamboulis, A.; Nakiou, E.A.; Christodoulou, E.; Bikiaris, D.N.; Kontonasaki, E.; Liverani, L.; Boccaccini, A.R. Polyglycerol Hyperbranched Polyesters: Synthesis, Properties and Pharmaceutical and Biomedical Applications. IJMS 2019, 20, 6210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Zhang, G. Recent Advances in the Properties and Applications of Polyglycerol Fatty Acid Esters. Polymers 2025, 17, 879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajan, K.; Samykano, M.; Kadirgama, K.; Harun, W.S.W.; Rahman, Md. M. Fused Deposition Modeling: Process, Materials, Parameters, Properties, and Applications. Int J Adv Manuf Technol 2022, 120, 1531–1570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daminabo, S.C.; Goel, S.; Grammatikos, S.A.; Nezhad, H.Y.; Thakur, V.K. Fused Deposition Modeling-Based Additive Manufacturing (3D Printing): Techniques for Polymer Material Systems. Materials Today Chemistry 2020, 16, 100248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keul, H.; Möller, M. Synthesis and Degradation of Biomedical Materials Based on Linear and Star Shaped Polyglycidols. J. Polym. Sci. A Polym. Chem. 2009, 47, 3209–3231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, W.Y.; Kim, Y.M.; Ahn, H.; Moon, H.C. Block versus Random: Effective Molecular Configuration of Copolymer Gelators to Obtain High-Performance Gel Electrolytes for Functional Electrochemical Devices. J. Mater. Chem. C 2020, 8, 17045–17053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janiszewska, N.; Basinska, T.; Gadzinowski, M.; Slomkowski, S.; Makowski, T.; Awsiuk, K. Impact of Polyglycidol Block Architecture in Polystyrene-b-Polyglycidol Copolymers on the Properties of Thin Films and Protein Adsorption. Applied Surface Science 2024, 669, 160458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Son, S.; Park, H.; Shin, E.; Shibasaki, Y.; Kim, B. Architecture-controlled Synthesis of Redox-degradable Hyperbranched Polyglycerol Block Copolymers and the Structural Implications of Their Degradation. J. Polym. Sci. Part A: Polym. Chem. 2016, 54, 1752–1761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, A.; Müller, S.S.; Frey, H. Beyond Poly(Ethylene Glycol): Linear Polyglycerol as a Multifunctional Polyether for Biomedical and Pharmaceutical Applications. Biomacromolecules 2014, 15, 1935–1954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Q.; Zhang, T.; An, J.; Wu, Z.; Zhao, Y.; Dai, X.; Zhang, X.; Li, C. Block versus Random Amphiphilic Glycopolymer Nanopaticles as Glucose-Responsive Vehicles. Biomacromolecules 2015, 16, 3345–3356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paulus, F.; Schulze, R.; Steinhilber, D.; Zieringer, M.; Steinke, I.; Welker, P.; Licha, K.; Wedepohl, S.; Dernedde, J.; Haag, R. The Effect of Polyglycerol Sulfate Branching On Inflammatory Processes. Macromolecular Bioscience 2014, 14, 643–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Yang, Y.; Shu, X.; Wang, Y.; Ran, Q.; Liu, J. Tailoring Polycarboxylate Architecture to Improve the Rheological Properties of Cement Paste. Journal of Dispersion Science and Technology 2019, 40, 1567–1574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, T.; Xu, X.; Guo, L.; Tang, H.; Diao, T.; Gan, Z.; Zhang, G.; Yu, Q. Efficient Tumor Accumulation, Penetration and Tumor Growth Inhibition Achieved by Polymer Therapeutics: The Effect of Polymer Architectures. Biomacromolecules 2017, 18, 217–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maddock, R.M.A.; Pollard, G.J.; Moreau, N.G.; Perry, J.J.; Race, P.R. Enzyme-catalysed Polymer Cross-linking: Biocatalytic Tools for Chemical Biology, Materials Science and Beyond. Biopolymers 2020, 111, e23390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- García-Astrain, C.; Avérous, L. Synthesis and Evaluation of Functional Alginate Hydrogels Based on Click Chemistry for Drug Delivery Applications. Carbohydrate Polymers 2018, 190, 271–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy, N.; Reddy, R.; Jiang, Q. Crosslinking Biopolymers for Biomedical Applications. Trends in Biotechnology 2015, 33, 362–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oryan, A.; Kamali, A.; Moshiri, A.; Baharvand, H.; Daemi, H. Chemical Crosslinking of Biopolymeric Scaffolds: Current Knowledge and Future Directions of Crosslinked Engineered Bone Scaffolds. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2018, 107, 678–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yue, K.; Trujillo-de Santiago, G.; Alvarez, M.M.; Tamayol, A.; Annabi, N.; Khademhosseini, A. Synthesis, Properties, and Biomedical Applications of Gelatin Methacryloyl (GelMA) Hydrogels. Biomaterials 2015, 73, 254–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piszko, P.; Kryszak, B.; Szustakiewicz, K. Influence of Cross-Linking Time on Physico-Chemical and Mechanical Properties of Bulk Poly(Glycerol Sebacate). Acta Bioeng Biomech 2022, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godinho, B.; Gama, N.; Ferreira, A. Different Methods of Synthesizing Poly(Glycerol Sebacate) (PGS): A Review. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2022, 10, 1033827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balser, S.; Zhao, Z.; Zharnikov, M.; Terfort, A. Effect of the Crosslinking Agent on the Biorepulsive and Mechanical Properties of Polyglycerol Membranes. Colloids and Surfaces B: Biointerfaces 2023, 225, 113271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiraishi, K.; Yokoyama, M. Toxicity and Immunogenicity Concerns Related to PEGylated-Micelle Carrier Systems: A Review. Science and Technology of Advanced Materials 2019, 20, 324–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, K.; Quichocho, H.-B.; Black, S.P.; Bramson, M.T.K.; Linhardt, R.J.; Corr, D.T.; Gross, R.A. Lipase-Catalyzed Poly(Glycerol-1,8-Octanediol-Sebacate): Biomaterial Engineering by Combining Compositional and Crosslinking Variables. Biomacromolecules 2022, 23, 2150–2159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, Y.-S.; Hu, M.-H.; Jan, J.-S.; Hu, J.-J. Incorporation of Glutamic Acid or Amino-Protected Glutamic Acid into Poly(Glycerol Sebacate): Synthesis and Characterization. Polymers 2022, 14, 2206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Najafi-Shoa, S.; Roghani-Mamaqani, H.; Salami-Kalajahi, M.; Azimi, R.; Gholipour-Mahmoudalilou, M. Incorporation of Epoxy Resin and Carbon Nanotube into Silica/Siloxane Network for Improving Thermal Properties. J Mater Sci 2016, 51, 9057–9073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, J.; Ding, X.; Stowell, C.E.T.; Wu, Y.-L.; Wang, Y. Slow Degrading Poly(Glycerol Sebacate) Derivatives Improve Vascular Graft Remodeling in a Rat Carotid Artery Interposition Model. Biomaterials 2020, 257, 120251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosalia, M.; Rubes, D.; Serra, M.; Genta, I.; Dorati, R.; Conti, B. Polyglycerol Sebacate Elastomer: A Critical Overview of Synthetic Methods and Characterisation Techniques. Polymers 2024, 16, 1405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerativitayanan, P.; Gaharwar, A.K. Elastomeric and Mechanically Stiff Nanocomposites from Poly(Glycerol Sebacate) and Bioactive Nanosilicates. Acta Biomaterialia 2015, 26, 34–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenbalm, T.N.; Teruel, M.; Day, C.S.; Donati, G.L.; Morykwas, M.; Argenta, L.; Kuthirummal, N.; Levi-Polyachenko, N. Structural and Mechanical Characterization of Bioresorbable, Elastomeric Nanocomposites from Poly(Glycerol Sebacate)/Nanohydroxyapatite for Tissue Transport Applications. J Biomed Mater Res 2016, 104, 1366–1373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashraf, M.A.; Peng, W.; Zare, Y.; Rhee, K.Y. Effects of Size and Aggregation/Agglomeration of Nanoparticles on the Interfacial/Interphase Properties and Tensile Strength of Polymer Nanocomposites. Nanoscale Res Lett 2018, 13, 214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rostamian, M.; Kalaee, M.R.; Dehkordi, S.R.; Panahi-Sarmad, M.; Tirgar, M.; Goodarzi, V. Design and Characterization of Poly(Glycerol-Sebacate)-Co-Poly(Caprolactone) (PGS-Co-PCL) and Its Nanocomposites as Novel Biomaterials: The Promising Candidate for Soft Tissue Engineering. European Polymer Journal 2020, 138, 109985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeinedini, A.; Shokrieh, M.M. Agglomeration Phenomenon in Graphene/Polymer Nanocomposites: Reasons, Roles, and Remedies. Applied Physics Reviews 2024, 11, 041301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colijn, I.; Schroën, K. Thermoplastic Bio-Nanocomposites: From Measurement of Fundamental Properties to Practical Application. Advances in Colloid and Interface Science 2021, 292, 102419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Govindaraj, P.; Sokolova, A.; Salim, N.; Juodkazis, S.; Fuss, F.K.; Fox, B.; Hameed, N. Distribution States of Graphene in Polymer Nanocomposites: A Review. Composites Part B: Engineering 2021, 226, 109353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vogt, L.; Ruther, F.; Salehi, S.; Boccaccini, A.R. Poly(Glycerol Sebacate) in Biomedical Applications—A Review of the Recent Literature. Adv Healthcare Materials 2021, 10, 2002026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.; Hong, A.T.-L.; Naskar, N.; Chung, H.-J. Criteria for Quick and Consistent Synthesis of Poly(Glycerol Sebacate) for Tailored Mechanical Properties. Biomacromolecules 2015, 16, 1525–1533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ben, Z.Y.; Samsudin, H.; Yhaya, M.F. Glycerol: Its Properties, Polymer Synthesis, and Applications in Starch Based Films. European Polymer Journal 2022, 175, 111377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barra, G.; Guadagno, L.; Raimondo, M.; Santonicola, M.G.; Toto, E.; Vecchio Ciprioti, S. A Comprehensive Review on the Thermal Stability Assessment of Polymers and Composites for Aeronautics and Space Applications. Polymers 2023, 15, 3786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kroll, D.M.; Croll, S.G. Influence of Crosslinking Functionality, Temperature and Conversion on Heterogeneities in Polymer Networks. Polymer 2015, 79, 82–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krumins, E.; C. Lentz, J.; Sutcliffe, B.; Sohaib, A.; L. Jacob, P.; Brugnoli, B.; Crucitti, V.C.; Cavanagh, R.; Owen, R.; Moloney, C.; Ruiz-Cantu, L.; Francolini, I.; M. Howdle, S.; Shusteff, M.; J. Rose, F.R.A.; D. Wildman, R.; He, Y.; Taresco, V. Glycerol-Based Sustainably Sourced Resin for Volumetric Printing. Green Chemistry 2024, 26, 1345–1355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, G.; Cao, Z.; Hopkins, M.; Lyons, J.G.; Brennan-Fournet, M.; Devine, D.M. Nanofillers Can Be Used to Enhance the Thermal Conductivity of Commercially Available SLA Resins. Procedia Manufacturing 2019, 38, 1236–1243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akman, R.; Ramaraju, H.; Hollister, M.; Verga, A.; Hollister, S.J. Thermal Post-Processing of 3D-Printed Poly(Glycerol Dodecanedioate) Controls Mechanics and Shape Memory Properties. Polymer Science & Technology 2025, 1, 132–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ao-Ieong, W.-S.; Chien, S.-T.; Jiang, W.-C.; Yet, S.-F.; Wang, J. The Effect of Heat Treatment toward Glycerol-Based, Photocurable Polymeric Scaffold: Mechanical, Degradation and Biocompatibility. Polymers 2021, 13, 1960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- I. p, M.; B, W.; Tamrin; H, I.; J.a, M. Thermal and Morphology Properties of Cellulose Nanofiber from TEMPO-Oxidized Lower Part of Empty Fruit Bunches (LEFB). Open Chemistry 2019, 17, 526–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golbaten-Mofrad, H.; Salehi, M.H.; Jafari, S.H.; Goodarzi, V.; Entezari, M.; Hashemi, M. Preparation and Properties Investigation of Biodegradable Poly (Glycerol Sebacate- Co -gelatin) Containing Nanoclay and Graphene Oxide for Soft Tissue Engineering Applications. J Biomed Mater Res 2022, 110, 2241–2257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gan, P.G.; Sam, S.T.; Abdullah, M.F.B.; Omar, M.F. Thermal Properties of Nanocellulose-reinforced Composites: A Review. J of Applied Polymer Sci 2020, 137, 48544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abudula, T.; Gzara, L.; Simonetti, G.; Alshahrie, A.; Salah, N.; Morganti, P.; Chianese, A.; Fallahi, A.; Tamayol, A.; Bencherif, S.A.; Memic, A. The Effect of Poly (Glycerol Sebacate) Incorporation within Hybrid Chitin–Lignin Sol–Gel Nanofibrous Scaffolds. Materials (Basel) 2018, 11, 451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, S.; Cook, W.D.; Chen, Q. Physical Characterization of Poly(Glycerol Sebacate)/Bioglass® Composites. Polymer International 2012, 61, 17–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Zhang, X.; Liu, X.; Guan, X.; Zhang, C.; Niu, Y. Polyglycerol-Based Organic-Inorganic Hybrid Adhesive with High Early Strength. Materials & Design 2017, 117, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yousefi Talouki, P.; Tamimi, R.; Zamanlui Benisi, S.; Goodarzi, V.; Shojaei, S.; Hesami Tackalou, S.; Samadikhah, H.R. Polyglycerol Sebacate (PGS)-Based Composite and Nanocomposites: Properties and Applications. International Journal of Polymeric Materials and Polymeric Biomaterials 2023, 72, 1360–1374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, S.H.; Yang, S.K. Water-Soluble Polyglycerol-Dendronized Poly(Norbornene)s with Functional Side-Chains. Soft Matter 2019, 15, 9452–9457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Zhang, Q.; Wen, X.; Wang, G.; Gong, X.; Shi, X. Dual Covalent Cross-Linking Networks in Polynorbornene: Comparison of Shape Memory Performance. Materials 2021, 14, 3249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esteruelas, M.A.; González, F.; Herrero, J.; Lucio, P.; Oliván, M.; Ruiz-Labrador, B. Thermal Properties of Polynorbornene (Cis- and Trans-) and Hydrogenated Polynorbornene. Polym. Bull. 2007, 58, 923–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levin, M.; Tang, Y.; Eisenbach, C.D.; Valentine, M.T.; Cohen, N. Understanding the Response of Poly(Ethylene Glycol) Diacrylate (PEGDA) Hydrogel Networks: A Statistical Mechanics-Based Framework. Macromolecules 2024, 57, 7074–7086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno-Castellanos, N.; Cuartas-Gómez, E.; Vargas-Ceballos, O. Functionalized Collagen/Poly(Ethylene Glycol) Diacrylate Interpenetrating Network Hydrogel Enhances Beta Pancreatic Cell Sustenance. Gels 2023, 9, 496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piszczyk, Ł.; Strankowski, M.; Danowska, M.; Hejna, A.; Haponiuk, J.T. Rigid Polyurethane Foams from a Polyglycerol-Based Polyol. European Polymer Journal 2014, 57, 143–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piszczyk, Ł.; Strankowski, M.; Danowska, M.; Haponiuk, J.T.; Gazda, M. Preparation and Characterization of Rigid Polyurethane–Polyglycerol Nanocomposite Foams. European Polymer Journal 2012, 48, 1726–1733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uram, K.; Leszczyńska, M.; Prociak, A.; Czajka, A.; Gloc, M.; Leszczyński, M.K.; Michałowski, S.; Ryszkowska, J. Polyurethane Composite Foams Synthesized Using Bio-Polyols and Cellulose Filler. Materials 2021, 14, 3474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, K.; Wang, L.; Zhang, K.; Ramaraju, H.; Hollister, S.J.; Fan, Y. Biodegradation Behavior Control for Shape Memory Polyester Poly(Glycerol-Dodecanoate): An In Vivo and In Vitro Study. Biomacromolecules 2023, 24, 2501–2511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramaraju, H.; Solorio, L.D.; Bocks, M.L.; Hollister, S.J. Degradation Properties of a Biodegradable Shape Memory Elastomer, Poly(Glycerol Dodecanoate), for Soft Tissue Repair. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0229112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramaraju, H.; Massarella, D.; Wong, C.; Verga, A.S.; Kish, E.C.; Bocks, M.L.; Hollister, S.J. Percutaneous Delivery and Degradation of a Shape Memory Elastomer Poly(Glycerol Dodecanedioate) in Porcine Pulmonary Arteries. Biomaterials 2023, 293, 121950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akman, R.; Ramaraju, H.; Hollister, S.J. Development of Photocrosslinked Poly(Glycerol Dodecanedioate)—A Biodegradable Shape Memory Polymer for 3D-Printed Tissue Engineering Applications. Adv Eng Mater 2021, 23, 2100219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, A.; Rahimian Koloor, S.S.; Alshehri, A.H.; Arockiarajan, A. Carbon Nanotube Characteristics and Enhancement Effects on the Mechanical Features of Polymer-Based Materials and Structures – A Review. Journal of Materials Research and Technology 2023, 24, 6495–6521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabet, M. Advanced Developments in Carbon Nanotube Polymer Composites for Structural Applications. Iran Polym J 2025, 34, 917–946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fenta, E.W.; Mebratie, B.A. Advancements in Carbon Nanotube-Polymer Composites: Enhancing Properties and Applications through Advanced Manufacturing Techniques. Heliyon 2024, 10, e36490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, B.; Ma, Y.; Wang, L.; Guo, Z.; Zhong, X.; Wu, T.; Liu, Y.; Wu, H. Thermal Decomposition Mechanism Investigation of Hyperbranched Polyglycerols by TGA-FTIR-GC/MS Techniques and ReaxFF Reactive Molecular Dynamics Simulations. Biomass and Bioenergy 2023, 168, 106675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalid, M.Y.; Al Rashid, A.; Arif, Z.U.; Ahmed, W.; Arshad, H.; Zaidi, A.A. Natural Fiber Reinforced Composites: Sustainable Materials for Emerging Applications. Results in Engineering 2021, 11, 100263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navarro, L.; Gamboa, A.; Minari, R.J.; Vaillard, S.E. Tailoring the Properties of Poly(Glycerol Sebacate-Co-Itaconate) Networks: A Sustainable Approach to Photocurable Biomaterials. Journal of Polymer Science 2025, pol.20250138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neumann, N.; Abels, G.; Koschek, K.; Boskamp, L. Crosslinked Hyperbranched Polyglycerol-Based Polymer Electrolytes for Lithium Metal Batteries. Batteries 2023, 9, 431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Risley, B.B.; Ding, X.; Chen, Y.; Miller, P.G.; Wang, Y. Citrate Crosslinked Poly(Glycerol Sebacate) with Tunable Elastomeric Properties. Macromolecular Bioscience 2021, 21, 2000301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kou, Y.; Wang, S.; Luo, J.; Sun, K.; Zhang, J.; Tan, Z.; Shi, Q. Thermal Analysis and Heat Capacity Study of Polyethylene Glycol (PEG) Phase Change Materials for Thermal Energy Storage Applications. The Journal of Chemical Thermodynamics 2019, 128, 259–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Zhi, C.; Lin, Y.; Bao, H.; Wu, G.; Jiang, P.; Mai, Y.-W. Thermal Conductivity of Graphene-Based Polymer Nanocomposites. Materials Science and Engineering: R: Reports 2020, 142, 100577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katheng, A.; Prawatvatchara, W.; Chaiamornsup, P.; Sornsuwan, T.; Lekatana, H.; Palasuk, J. Comparison of Mechanical Properties of Different 3D Printing Technologies. Sci Rep 2025, 15, 18998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, Y.J.; Kim, H.N.; Kim, D.Y. A Study on Effects of Curing and Machining Conditions in Post-Processing of SLA Additive Manufactured Polymer. Journal of Manufacturing Processes 2024, 119, 511–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krumins, E.; Lentz, J.C.; Sutcliffe, B.; Sohaib, A.; Jacob, P.L.; Brugnoli, B.; Cuzzucoli Crucitti, V.; Cavanagh, R.; Owen, R.; Moloney, C.; Ruiz-Cantu, L.; Francolini, I.; Howdle, S.M.; Shusteff, M.; Rose, F.R.A.J.; Wildman, R.D.; He, Y.; Taresco, V. Glycerol-Based Sustainably Sourced Resin for Volumetric Printing. Green Chem. 2024, 26, 1345–1355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krumins, E.; George, K.; Taresco, V.; Sun, X.; Hoggett, S.; Duncan, J.; Cuzzucoli Crucitti, V.; Segal, J.; Irvine, D.J.; Khlobystov, A.; Wildman, R. Sustainable and Electrically Conductive Poly(Glycerol) (Meth)Acrylate Resins for Stereolithography and Volumetric Additive Manufacturing. In Smart Materials for Opto-Electronic Applications 2025; Rendina, I., Petti, L., Sagnelli, D., Nenna, G., Eds.; SPIE: Prague, Czech Republic, 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loterie, D.; Delrot, P.; Moser, C. High-Resolution Tomographic Volumetric Additive Manufacturing. Nat Commun 2020, 11, 852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohd Sabee, M.M.S.; Itam, Z.; Beddu, S.; Zahari, N.M.; Mohd Kamal, N.L.; Mohamad, D.; Zulkepli, N.A.; Shafiq, M.D.; Abdul Hamid, Z.A. Flame Retardant Coatings: Additives, Binders, and Fillers. Polymers 2022, 14, 2911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Troitzsch, J.H. Fire Performance Durability of Flame Retardants in Polymers and Coatings. Advanced Industrial and Engineering Polymer Research 2024, 7, 263–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.-Y.; Hwang, J.V.; Ao-Ieong, W.-S.; Lin, Y.-C.; Hsieh, Y.-K.; Cheng, Y.-L.; Wang, J. Study of Physical and Degradation Properties of 3D-Printed Biodegradable, Photocurable Copolymers, PGSA-Co-PEGDA and PGSA-Co-PCLDA. Polymers 2018, 10, 1263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gürbüz, B.; Balikci, E.; Baran, E.T. Electrospun Scaffolds for Heart Valve Tissue Engineering. Explor BioMat-X. 2025, 2, 101331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, F.E.; Kelly, D.J. Tuning Alginate Bioink Stiffness and Composition for Controlled Growth Factor Delivery and to Spatially Direct MSC Fate within Bioprinted Tissues. Sci Rep 2017, 7, 17042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, J.; Duongthipthewa, A.; Xu, X.; Liu, M.; Xiong, Y.; Zhou, L. Interlayer Bonding Improvement of PEEK and CF-PEEK Composites with Laser-Assisted Fused Deposition Modeling. Composites Communications 2024, 45, 101819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pugalendhi, A.; Ranganathan, R.; Ganesan, S. Impact of Process Parameters on Mechanical Behaviour in Multi-Material Jetting. Materials Today: Proceedings 2021, 46, 9139–9144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adarsh, S.H.; Nagamadhu, M. Effect of Printing Parameters on Mechanical Properties and Warpage of 3D-Printed PEEK/CF-PEEK Composites Using Multi-Objective Optimization Technique. J. Compos. Sci. 2025, 9, 208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battistelli, C.; Seriani, S.; Lughi, V.; Slejko, E.A. Optimizing 3D -Printing Parameters for Enhanced Mechanical Properties in Liquid Crystalline Polymer Components. Polymers for Advanced Techs 2024, 35, e70037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- P, T.T.; S, V.K.; B, T.M. Effect of Layer Thickness on the Tensile and Impact Behaviour of SLA-Printed Parts. IJRASET 2024, 12, 1848–1852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsueh, M.-H.; Lai, C.-J.; Wang, S.-H.; Zeng, Y.-S.; Hsieh, C.-H.; Pan, C.-Y.; Huang, W.-C. Effect of Printing Parameters on the Thermal and Mechanical Properties of 3D-Printed PLA and PETG, Using Fused Deposition Modeling. Polymers 2021, 13, 1758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahimah Abdul Hamid; Siti Nur Hidayah Husni; Teruaki Ito; Barbara Sabine Linke. Effect of Printing Orientation and Layer Thickness on Microstructure and Mechanical Properties of PLA Parts. MJCSM 2022, 8, 11–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kontaxis, L.C.; Zachos, D.; Georgali-Fickel, A.; Portan, D.V.; Zaoutsos, S.P.; Papanicolaou, G.C. 3D-Printed PLA Mechanical and Viscoelastic Behavior Dependence on the Nozzle Temperature and Printing Orientation. Polymers 2025, 17, 913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farkas, A.Z.; Galatanu, S.-V.; Nagib, R. The Influence of Printing Layer Thickness and Orientation on the Mechanical Properties of DLP 3D-Printed Dental Resin. Polymers 2023, 15, 1113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shergill, K.; Chen, Y.; Bull, S. An Investigation into the Layer Thickness Effect on the Mechanical Properties of Additively Manufactured Polymers: PLA and ABS. Int J Adv Manuf Technol 2023, 126, 3651–3665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guidetti, X.; Balta, E.C.; Nagel, Y.; Yin, H.; Rupenyan, A.; Lygeros, J. Stress Flow Guided Non-Planar Print Trajectory Optimization for Additive Manufacturing of Anisotropic Polymers. Additive Manufacturing 2023, 72, 103628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cicek, U.I.; Johnson, A.A. Multi-Objective Optimization of FDM Process Parameters for 3D-Printed Polycarbonate Using Taguchi-Based Gray Relational Analysis. Int J Adv Manuf Technol 2025, 137, 3709–3725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zohdi, N.; Yang, R. (Chunhui). Material Anisotropy in Additively Manufactured Polymers and Polymer Composites: A Review. Polymers (Basel) 2021, 13, 3368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moetazedian, A.; Gleadall, A.; Han, X.; Ekinci, A.; Mele, E.; Silberschmidt, V.V. Mechanical Performance of 3D Printed Polylactide during Degradation. Additive Manufacturing 2021, 38, 101764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Berry, D.B.; Song, Z.; Kiratitanaporn, W.; Schimelman, J.; Moran, A.; He, F.; Xi, B.; Cai, S.; Chen, S. 3D Printing of a Biocompatible Double Network Elastomer with Digital Control of Mechanical Properties. Adv Funct Materials 2020, 30, 1910391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, X.; Lv, X.; Tian, Q.; AlMasoud, N.; Xu, Y.; Alomar, T.S.; El-Bahy, Z.M.; Li, J.; Algadi, H.; Roymahapatra, G.; Ding, T.; Guo, J.; Li, X. Silica Binary Hybrid Particles Based on Reduced Graphene Oxide for Natural Rubber Composites with Enhanced Thermal Conductivity and Mechanical Properties. Adv Compos Hybrid Mater 2023, 6, 141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, X.; Chen, Y.; Chao, C.A.; Wu, Y.; Wang, Y. Control the Mechanical Properties and Degradation of Poly(Glycerol Sebacate) by Substitution of the Hydroxyl Groups with Palmitates. Macromolecular Bioscience 2020, 20, 2000101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Jin, K.; Wang, L.; Fan, Y. A Review: Optimization for Poly(Glycerol Sebacate) and Fabrication Techniques for Its Centered Scaffolds. Macromolecular Bioscience 2021, 21, 2100022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Halpern, J.M.; Urbanski, R.; Weinstock, A.K.; Iwig, D.F.; Mathers, R.T.; Von Recum, H.A. A Biodegradable Thermoset Polymer Made by Esterification of Citric Acid and Glycerol. J Biomedical Materials Res 2014, 102, 1467–1477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, R.; Kundu, D. Structural and Transport Properties of Norbornene-Functionalized Poly(Vinyl Alcohol) “Click” Hydrogel: A Molecular Dynamics Study. ACS Sustainable Chem. Eng. 2023, 11, 10812–10824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fortelny, I.; Ujcic, A.; Fambri, L.; Slouf, M. Phase Structure, Compatibility, and Toughness of PLA/PCL Blends: A Review. Front. Mater. 2019, 6, 206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Wang, C.; Gao, G.; Yin, X.; Pu, X.; Shi, B.; Liu, Y.; Huang, Z.; Wang, J.; Li, J.; Yin, G. MBG/PGA-PCL Composite Scaffolds Provide Highly Tunable Degradation and Osteogenic Features. Bioactive Materials 2022, 15, 53–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flaig, F.; Ragot, H.; Simon, A.; Revet, G.; Kitsara, M.; Kitasato, L.; Hébraud, A.; Agbulut, O.; Schlatter, G. Design of Functional Electrospun Scaffolds Based on Poly(Glycerol Sebacate) Elastomer and Poly(Lactic Acid) for Cardiac Tissue Engineering. ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng. 2020, 6, 2388–2400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molina, B.G.; Ocón, G.; Silva, F.M.; Iribarren, J.I.; Armelin, E.; Alemán, C. Thermally-Induced Shape Memory Behavior of Polylactic Acid/Polycaprolactone Blends. European Polymer Journal 2023, 196, 112230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.-Y.; Hwang, J.V.; Ao-Ieong, W.-S.; Lin, Y.-C.; Hsieh, Y.-K.; Cheng, Y.-L.; Wang, J. Study of Physical and Degradation Properties of 3D-Printed Biodegradable, Photocurable Copolymers, PGSA-Co-PEGDA and PGSA-Co-PCLDA. Polymers 2018, 10, 1263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Migneco, F.; Huang, Y.-C.; Birla, R.K.; Hollister, S.J. Poly(Glycerol-Dodecanoate), a Biodegradable Polyester for Medical Devices and Tissue Engineering Scaffolds. Biomaterials 2009, 30, 6479–6484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fortelny, I.; Ujcic, A.; Fambri, L.; Slouf, M. Phase Structure, Compatibility, and Toughness of PLA/PCL Blends: A Review. Front. Mater. 2019, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalili, M.H.; Williams, C.J.; Micallef, C.; Duarte-Martinez, F.; Afsar, A.; Zhang, R.; Wilson, S.; Dossi, E.; Impey, S.A.; Goel, S.; Aria, A.I. Nanoindentation Response of 3D Printed PEGDA Hydrogels in a Hydrated Environment. ACS Appl. Polym. Mater. 2023, 5, 1180–1190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shundo, A.; Aoki, M.; Yamamoto, S.; Tanaka, K. Impact of Cross-Linking on the Time–Temperature Superposition of Creep Rupture in Epoxy Resins. Soft Matter 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sencadas, V.; Sadat, S.; Silva, D.M. Mechanical Performance of Elastomeric PGS Scaffolds under Dynamic Conditions. Journal of the Mechanical Behavior of Biomedical Materials 2020, 102, 103474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.; Shim, J.-S.; Lee, D.; Shin, S.-H.; Nam, N.-E.; Park, K.-H.; Shim, J.-S.; Kim, J.-E. Effects of Post-Curing Time on the Mechanical and Color Properties of Three-Dimensional Printed Crown and Bridge Materials. Polymers 2020, 12, 2762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bulanda, K.; Oleksy, M.; Oliwa, R. Polymer Composites Based on Glycol-Modified Poly(Ethylene Terephthalate) Applied to Additive Manufacturing Using Melted and Extruded Manufacturing Technology. Polymers 2022, 14, 1605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Wang, W.; Zhang, Z.; Xu, L.; Li, P. Study of the Glass Transition Temperature and the Mechanical Properties of PET/Modified Silica Nanocomposite by Molecular Dynamics Simulation. European Polymer Journal 2016, 75, 36–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeasmin, F.; Mallik, A.K.; Chisty, A.H.; Robel, F.N.; Shahruzzaman, Md.; Haque, P.; Rahman, M.M.; Hano, N.; Takafuji, M.; Ihara, H. Remarkable Enhancement of Thermal Stability of Epoxy Resin through the Incorporation of Mesoporous Silica Micro-Filler. Heliyon 2021, 7, e05959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Gutbrod, S.R.; Bonifas, A.P.; Su, Y.; Sulkin, M.S.; Lu, N.; Chung, H.-J.; Jang, K.-I.; Liu, Z.; Ying, M. 3D Multifunctional Integumentary Membranes for Spatiotemporal Cardiac Measurements and Stimulation across the Entire Epicardium. Nat. Commun. 2014, 5, 3329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alamfard, T.; Lorenz, T.; Breitkopf, C. Glass Transition Temperatures and Thermal Conductivities of Polybutadiene Crosslinked with Randomly Distributed Sulfur Chains Using Molecular Dynamic Simulation. Polymers 2024, 16, 384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, C.; Gerhard, E.; Lu, D.; Yang, J. Citrate Chemistry and Biology for Biomaterials Design. Biomaterials 2018, 178, 383–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eqra, R.; Moghim, M.H.; Eqra, N. A Study on the Mechanical Properties of Graphene Oxide/Epoxy Nanocomposites. Polymers and Polymer Composites 2021, 29, S556–S564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atif, R.; Shyha, I.; Inam, F. Mechanical, Thermal, and Electrical Properties of Graphene-Epoxy Nanocomposites—A Review. Polymers (Basel) 2016, 8, 281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suwanphiphat, S.; Kitsawat, V.; Panpranot, J.; Siri, S.; Yang, J.-Y.; Chuang, C.-H.; Liao, Y.-C.; Phisalaphong, M. Enhancing Electrical Conductivity and Mechanical Properties of Natural Rubber Composites with Graphene Fillers and Chitosan. ACS Appl. Polym. Mater. 2025, acsapm.5c00675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Ma, Y.; Yan, C.; Xu, H.; Liu, D.; Chen, G.; Shi, P.; Hu, J.; Gao, C. Improved Interfacial Shear Strength of CF/PA6 and CF/Epoxy Composites by Grafting Graphene Oxide onto Carbon Fiber Surface with Hyperbranched Polyglycerol. Surface & Interface Analysis 2021, 53, 831–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marouazi, H.E.; van der Schueren, B.; Favier, D.; Bolley, A.; Dagorne, S.; Dintzer, T.; Janowska, I. Great Enhancement of Mechanical Features in PLA Based Composites Containing Aligned Few Layer Graphene (FLG), the Effect of FLG Loading, Size and Dispersion on Mechanical and Thermal Properties. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, G.; Yi, H.; Yao, Y.; Li, C.; Li, Z. Thermally Conductive Graphene Films for Heat Dissipation. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2020, 3, 2149–2155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.; Bao, J.; Ye, H.; Wang, N.; Yuan, G.; Ke, W.; Zhang, D.; Yue, W.; Fu, Y.; Ye, L.; Jeppson, K.; Liu, J. The Effects of Graphene-Based Films as Heat Spreaders for Thermal Management in Electronic Packaging. In 2016 17th International Conference on Electronic Packaging. In 2016 17th International Conference on Electronic Packaging Technology (ICEPT); IEEE: Wuhan, China, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, H.; Zhang, Z.; Li, Z.; Peng, L.; Yang, G.; Zhao, T.; Zhang, Y.; Huang, G.; Cui, C. Silver/Graphene Oxide Composite with High Thermal/Electrical Conductivity and Mechanical Performance Developed through a Dual-Dispersion Medium Method. Journal of Materials Research and Technology 2024, 33, 8211–8221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maalihan, R.D.; Pajarito, B.B.; Advincula, R.C. 3D-Printing Methacrylate/Chitin Nanowhiskers Composites via Stereolithography: Mechanical and Thermal Properties. Materials Today: Proceedings 2020, 33, 1819–1824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uddin, Md. N.; Hossain, Md. T.; Mahmud, N.; Alam, S.; Jobaer, M.; Mahedi, S.I.; Ali, A. Research and Applications of Nanoclays: A Review. SPE Polymers 2024, 5, 507–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwaśniewska, A.; Chocyk, D.; Gładyszewski, G.; Borc, J.; Świetlicki, M.; Gładyszewska, B. The Influence of Kaolin Clay on the Mechanical Properties and Structure of Thermoplastic Starch Films. Polymers 2020, 12, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- (149) Ghaffari, T.; Barzegar, A.; Hamedi Rad, F.; Moslehifard, E. Effect of Nanoclay on Thermal Conductivity and Flexural Strength of Polymethyl Methacrylate Acrylic Resin. J Dent (Shiraz) 2016, 17, 121–127. [Google Scholar]

- Vahabi, H.; Batistella, M.A.; Otazaghine, B.; Longuet, C.; Ferry, L.; Sonnier, R.; Lopez-Cuesta, J.-M. Influence of a Treated Kaolinite on the Thermal Degradation and Flame Retardancy of Poly(Methyl Methacrylate). Applied Clay Science 2012, 70, 58–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abulyazied, D.E.; Ene, A. An Investigative Study on the Progress of Nanoclay-Reinforced Polymers: Preparation, Properties, and Applications: A Review. Polymers (Basel) 2021, 13, 4401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Yang, P.; Sun, W. Effects of Kaolinite on Thermal, Mechanical, Fire Behavior and Their Mechanisms of Intumescent Flame-Retardant Polyurea. Polymer Degradation and Stability 2022, 197, 109842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ray, S.S.; Tersur Orasugh, J.; Temane, L.T. Application of Polymer-Nanoclay in Flame Retardant Systems. In Nanoclays; Springer Nature Switzerland: Cham, 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Lv, X.; Tian, Q.; AlMasoud, N.; Xu, Y.; Alomar, T.S.; El-Bahy, Z.M.; Li, J.; Algadi, H.; Roymahapatra, G.; Ding, T.; Guo, J.; Li, X. Silica Binary Hybrid Particles Based on Reduced Graphene Oxide for Natural Rubber Composites with Enhanced Thermal Conductivity and Mechanical Properties. Adv Compos Hybrid Mater 2023, 6, 141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kopnar, V.; Carlyle, L.; Liu, E.; Khaenyook, S.; O’Connell, A.; Shirshova, N.; Aufderhorst-Roberts, A. Addressing the Stiffness–Toughness Conflict in Hybrid Double-Network Hydrogels through a Design of Experiments Approach. Soft Matter 2025, 21, 3604–3612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patil, N.A.; Joshi, K.; Lee, J.; Strawhecker, K.E.; Dunn, R.; Lawton, T.; Wetzel, E.D.; Park, J.H. Additive Manufacturing of Thermoplastic Elastomer Structures Using Dual Material Core-Shell Filaments. Additive Manufacturing 2024, 82, 104044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, P.; Zhao, Z.; Xu, D.; Zhu, J.; Sun, A.; Wei, L.; Li, Y. Hyperbranched Polyurethane Co-Crosslinked with Epoxy Resin Achieves Strong Bonding at Both Room Temperature and Ultra-Low Temperatures. Colloids and Surfaces A: Physicochemical and Engineering Aspects 2025, 707, 135949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.Y.; Xiang, H.P.; Fan, L.F.; Zhang, M.Q. Shape Memory Elastomers: A Review of Molecular Structures, Stimulus Mechanisms, and Emerging Applications. Polymer Science & Technology 2025, polymscitech.4c00035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wick, C.D.; Peters, A.J.; Li, G. Simulation Study of Shape Memory Polymer Networks Formed by Free Radical Polymerization. Polymer 2023, 281, 126114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Wei, Q.; Zhang, J. Light-Responsive Shape Memory Polymer Composites. European Polymer Journal 2022, 173, 111314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, M.; Tronci, G.; Pask, C.M.; Russell, S.J. Nonwoven Reinforced Photocurable Poly(Glycerol Sebacate)-Based Hydrogels. Polymers 2024, 16, 869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inverardi, N.; Toselli, M.; Scalet, G.; Messori, M.; Auricchio, F.; Pandini, S. Stress-Free Two-Way Shape Memory Effect of Poly(Ethylene Glycol)/Poly(ε-Caprolactone) Semicrystalline Networks. Macromolecules 2022, 55, 8533–8547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Zhou, Y.; Chen, H.; Zheng, Y.; Liu, J.; Bao, Y.; Shan, G.; Yu, C.; Pan, P. Shape Memory Networks With Tunable Self-Stiffening Kinetics Enabled by Polymer Melting-Recrystallization. Advanced Materials 2025, 2500295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfau, M.R.; McKinzey, K.G.; Roth, A.A.; Graul, L.M.; Maitland, D.J.; Grunlan, M.A. Shape Memory Polymer (SMP) Scaffolds with Improved Self-Fitting Properties. J. Mater. Chem. B 2021, 9, 3826–3837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Yu, R.; Guo, B. Shape-Memory and Self-Healing Polymers Based on Dynamic Covalent Bonds and Dynamic Noncovalent Interactions: Synthesis, Mechanism, and Application. ACS Appl. Bio Mater. 2021, 4, 5926–5943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, S.; Sun, Y.; Ma, C.; Duan, G.; Liu, Z.; Ma, C. Recent Advances in Dynamic Covalent Bond-Based Shape Memory Polymers. e-Polymers 2022, 22, 285–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roh, S.; Nam, Y.; Nguyen, M.T.N.; Han, J.-H.; Lee, J.S. Dynamic Covalent Bond-Based Polymer Chains Operating Reversibly with Temperature Changes. Molecules 2024, 29, 3261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramaraju, H.; McAtee, A.M.; Akman, R.E.; Verga, A.S.; Bocks, M.L.; Hollister, S.J. Sterilization Effects on Poly(Glycerol Dodecanedioate): A Biodegradable Shape Memory Elastomer for Biomedical Applications. J Biomed Mater Res 2023, 111, 958–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, S.M.; Fletcher, G.K.; Monroe, M.B.B.; Wierzbicki, M.A.; Nash, L.D.; Maitland, D.J. Shape Memory Polymer Foams Synthesized Using Glycerol and Hexanetriol for Enhanced Degradation Resistance. Polymers 2020, 12, 2290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saunoryte, E.; Navaruckiene, A.; Grauzeliene, S.; Bridziuviene, D.; Raudoniene, V.; Ostrauskaite, J. Glycerol Acrylate-Based Photopolymers with Antimicrobial and Shape-Memory Properties. Polymers 2024, 16, 862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaky, S.H.; Lee, K.W.; Gao, J.; Jensen, A.; Verdelis, K.; Wang, Y.; Almarza, A.J.; Sfeir, C. Poly (Glycerol Sebacate) Elastomer Supports Bone Regeneration by Its Mechanical Properties Being Closer to Osteoid Tissue Rather than to Mature Bone. Acta Biomaterialia 2017, 54, 95–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, R.; Maparathne, S.; Chinwangso, P.; Lee, T.R. Review of Shape-Memory Polymer Nanocomposites and Their Applications. Applied Sciences 2025, 15, 2419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez-Rexach, E.; Smith, P.T.; Gomez-Lopez, A.; Fernandez, M.; Cortajarena, A.L.; Sardon, H.; Nelson, A. 3D-Printed Bioplastics with Shape-Memory Behavior Based on Native Bovine Serum Albumin. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2021, 13, 19193–19199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goh, G.L.; Lee, S.; Cheng, S.H.; Goh, D.J.S.; Laya, P.; Nguyen, V.P.; Han, B.S.; Yeong, W.Y. Enhancing Interlaminar Adhesion in Multi-Material 3D Printing: A Study of Conductive PLA and TPU Interfaces through Fused Filament Fabrication. MSAM 2024, 3, 2672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pahari, S.; Melenka, G.W. Analysis of the Interface Properties of Multi-Material Fused Filament Fabricated (FFF) Printed Polymer Composite Structures. International Journal of Adhesion and Adhesives 2025, 104074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, L.; Zeng, G.; Xu, J.; Han, M.; Wang, Z.; Li, T.; Long, M.; Wang, L.; Huang, W.; Wu, Y. Development of Poly(Glycerol Sebacate) and Its Derivatives: A Review of the Progress over the Past Two Decades. Polymer Reviews 2023, 63, 613–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aleemardani, M.; Johnson, L.; Trikić, M.Z.; Green, N.H.; Claeyssens, F. Synthesis and Characterisation of Photocurable Poly(Glycerol Sebacate)-Co-Poly(Ethylene Glycol) Methacrylates. Materials Today Advances 2023, 19, 100410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, S.; Dou, W.; Zeng, X.; Chen, X.; Gao, Y.; Liu, H.; Li, S. Recent Advances in the Degradability and Applications of Tissue Adhesives Based on Biodegradable Polymers. IJMS 2024, 25, 5249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kruszynski, J.; Nowicka, W.; Pasha, F.A.; Yang, L.; Rozanski, A.; Bouyahyi, M.; Kleppinger, R.; Jasinska-Walc, L.; Duchateau, R. Tuning the Adhesive Strength of Functionalized Polyolefin-Based Hot Melt Adhesives: Unexpected Results Leading to New Opportunities. Macromolecules 2025, 58, 2894–2904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyata, T.; Sato, Y.K.; Kawagoe, Y.; Shirasu, K.; Wang, H.-F.; Kumagai, A.; Kinoshita, S.; Mizukami, M.; Yoshida, K.; Huang, H.-H.; Okabe, T.; Hagita, K.; Mizoguchi, T.; Jinnai, H. Effect of Inorganic Material Surface Chemistry on Structures and Fracture Behaviours of Epoxy Resin. Nat Commun 2024, 15, 1898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomez-Lopez, A.; Grignard, B.; Calvo, I.; Detrembleur, C.; Sardon, H. Accelerating the Curing of Hybrid Poly(Hydroxy Urethane)-Epoxy Adhesives by the Thiol-Epoxy Chemistry. ACS Appl. Polym. Mater. 2022, 4, 8786–8794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takao Ota. Effect of Silane Coupling Agent Concentration on Interfacial Properties of Basalt Fiber Reinforced Composites. JMSE-A 2023, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, K.; Zhou, J.; Han, S.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, W.; Fan, C. Silane Coupling Agent Enhances Recycle Aggregate/Asphalt Interfacial Properties: An Experimental and Molecular Dynamics Study. Materials Today Communications 2024, 39, 108681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azani, M.-R.; Hassanpour, A. UV-Curable Polymer Nanocomposites: Material Selection, Formulations, and Recent Advances. J. Compos. Sci. 2024, 8, 441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, W.; Zu, Z.; Huang, Y.; Xiang, H.; Liu, X. UV-Curing 3D Printing of High-Performance, Recyclable, Biobased Photosensitive Resin Enabled by Dual-Crosslinking Networks. Additive Manufacturing 2024, 91, 104352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azani, M.-R.; Hassanpour, A. UV-Curable Polymer Nanocomposites: Material Selection, Formulations, and Recent Advances. J. Compos. Sci. 2024, 8, 441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, X.; Liu, Y.; Mo, S.; Zhai, L.; He, M.; Fan, L.; Wang, Y.; Zhao, W.; Wang, G. 3D Printed Sequence-Controlled Copolyimides with High Thermal and Mechanical Performance. Composites Part B: Engineering 2024, 273, 111262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mushtaq, R.T.; Rehman, M.; Bao, C.; Wang, Y.; Khan, A.M.; Sharma, S.; Anwar, S. Enhanced Biomechanical Compatibility of 3D-Printed Polylactic Acid Lattice Structures: Synergizing Mechanical, Topography, and Microstructural Properties for Trabecular Bone Mimicry. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2025, 144373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vatankhah, E.; Abasnezhad, M.; Nazerian, M.; Barmar, M.; Partovinia, A. Thermal Energy Storage and Mechanical Performance of Composites of Rigid Polyurethane Foam and Phase Change Material Prepared by One-Shot Synthesis Method. J Polym Res 2022, 29, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, G.-Z.; Palencia, J.L.D.; Wang, D.-Y. Fully Bio-Based Poly (Glycerol-Itaconic Acid) as Supporter for PEG Based Form Stable Phase Change Materials. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omisol, C.J.M.; Aguinid, B.J.M.; Abilay, G.Y.; Asequia, D.M.; Tomon, T.R.; Sabulbero, K.X.; Erjeno, D.J.; Osorio, C.K.; Usop, S.; Malaluan, R.; Dumancas, G.; Resurreccion, E.P.; Lubguban, A.; Apostol, G.; Siy, H.; Alguno, A.C.; Lubguban, A. Flexible Polyurethane Foams Modified with Novel Coconut Monoglycerides-Based Polyester Polyols. ACS Omega 2024, 9, 4497–4512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calderon, M.J.P.; Dumancas, G.G.; Gutierrez, C.S.; Lubguban, A.A.; Alguno, A.C.; Malaluan, R.M.; Lubguban, A.A. Producing Polyglycerol Polyester Polyol for Thermoplastic Polyurethane Application: A Novel Valorization of Glycerol, a by-Product of Biodiesel Production. Heliyon 2023, 9, e19491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Ma, B. Ultraviolet-Follow Curing-Mediated Extrusion Stabilization for Low-Yield-Stress Silicone Rubbers: From Die Swell Suppression to Dimensional Accuracy Enhancement. Polymers (Basel) 2025, 17, 811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nijst, C.L.E.; Bruggeman, J.P.; Karp, J.M.; Ferreira, L.; Zumbuehl, A.; Bettinger, C.J.; Langer, R. Synthesis and Characterization of Photocurable Elastomers from Poly(Glycerol- Co -Sebacate). Biomacromolecules 2007, 8, 3067–3073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Q.-Z.; Bismarck, A.; Hansen, U.; Junaid, S.; Tran, M.Q.; Harding, S.E.; Ali, N.N.; Boccaccini, A.R. Characterisation of a Soft Elastomer Poly(Glycerol Sebacate) Designed to Match the Mechanical Properties of Myocardial Tissue. Biomaterials 2008, 29, 47–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sundback, C.; Shyu, J.; Wang, Y.; Faquin, W.; Langer, R.; Vacanti, J.; Hadlock, T. Biocompatibility Analysis of Poly(Glycerol Sebacate) as a Nerve Guide Material. Biomaterials 2005, 26, 5454–5464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsushita, S.; Kajita, S.; Mori, K. Enhanced Adhesion and Resolution of Negative Photoresists on Copper Substrates with Polyglycerin-Based Methacrylate. J. Photopol. Sci. Technol. 2024, 37, 411–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Żołek-Tryznowska, Z.; Tryznowski, M.; Królikowska, J. Hyperbranched Polyglycerol as an Additive for Water-Based Printing Ink. J Coat Technol Res 2015, 12, 385–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subramani, R.; Mohammed Ahmed Mustafa; Ghadir Kamil Ghadir; Hayder Musaad Al-Tmimi; Zaid Khalid Alani; Rusho, M. A.; Rajeswari, N.; D. Haridas; A. John Rajan; Avvaru Praveen Kumar. Exploring the Use of Biodegradable Polymer Materials in Sustainable 3D Printing. Appl. Chem. Eng. 2024, 7, 3870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.Y.; Kim, H.; Kim, H.-J.; Chung, C.J.; Choi, Y.J.; Kim, S.-J.; Cha, J.-Y. Thermo-Mechanical Properties of 3D Printed Photocurable Shape Memory Resin for Clear Aligners. Sci Rep 2022, 12, 6246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tarhini, A.A.; Tehrani-Bagha, A.R. Graphene-Based Polymer Composite Films with Enhanced Mechanical Properties and Ultra-High in-Plane Thermal Conductivity. Composites Science and Technology 2019, 184, 107797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, H.; Sung, M.; Choi, J.; Lee, H.; Prabakaran, L.; Kim, J.W. Ultralight, Robust, Thermal Insulating Silica Nanolace Aerogels Derived from Pickering Emulsion Templates. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2024, 16, 9255–9263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghazali, H.S.; Askari, E.; Ghazali, Z.S.; Naghib, S.M.; Braschler, T. Lithography-Based 3D Printed Hydrogels: From Bioresin Designing to Biomedical Application. Colloid and Interface Science Communications 2022, 50, 100667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Luo, Z.; Bao, Y. Trends in Photopolymerization 3D Printing for Advanced Drug Delivery Applications. Biomacromolecules 2025, 26, 85–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, Y.-L.; D’Amato, A.R.; Yan, A.M.; Wang, R.Q.; Ding, X.; Wang, Y. Three-Dimensional Printing of Poly(Glycerol Sebacate) Acrylate Scaffolds via Digital Light Processing. ACS Appl. Bio Mater. 2020, 3, 7575–7588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schittecatte, L.; Geertsen, V.; Bonamy, D.; Nguyen, T.; Guenoun, P. From Resin Formulation and Process Parameters to the Final Mechanical Properties of 3D Printed Acrylate Materials. MRS Communications 2023, 13, 357–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.; Lee, S.-J.; Park, K.-M.; Jung, T.-G. Biomechanical and Biological Assessment of Polyglycelrolsebacate-Coupled Implant with Shape Memory Effect for Treating Osteoporotic Fractures. Bioengineering (Basel) 2023, 10, 1413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Bartolo, A.; Melchels, F.P.W. Prolonged Recovery of 3D Printed, Photo-Cured Polylactide Shape Memory Polymer Networks. APL Bioeng 2020, 4, 036105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makowska, S.; Szymborski, D.; Sienkiewicz, N.; Kairytė, A. Current Progress in Research into Environmentally Friendly Rigid Polyurethane Foams. Materials 2024, 17, 3971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaikade, D.S.; Sabnis, A.S. Polyurethane Foams from Vegetable Oil-Based Polyols: A Review. Polym Bull (Berl) 2023, 80, 2239–2261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleh Alghamdi, S.; John, S.; Roy Choudhury, N.; Dutta, N.K. Additive Manufacturing of Polymer Materials: Progress, Promise and Challenges. Polymers 2021, 13, 753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, K.; Li, H.; Liang, M.; Li, Y.; Wang, L.; Fan, Y. Relationship between Mechanical Load and Surface Erosion Degradation of a Shape Memory Elastomer Poly(Glycerol-Dodecanoate) for Soft Tissue Implant. Regenerative Biomaterials 2023, 10, rbad050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baudis, S.; Behl, M. High-Throughput and Combinatorial Approaches for the Development of Multifunctional Polymers. Macromol. Rapid Commun. 2022, 43, 2100400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karuppusamy, M.; Thirumalaisamy, R.; Palanisamy, S.; Nagamalai, S.; El Sayed Massoud, E.; Ayrilmis, N. A Review of Machine Learning Applications in Polymer Composites: Advancements, Challenges, and Future Prospects. J. Mater. Chem. A 2025, 13, 16290–16308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| PG Type | Modifier | Thermal Indicator | Observed Change | Application |

| Poly(glycerol tartrate) hydrogel | Cellulose nanofibers | T₅% (onset of 5 % weight loss): increased from ~230 °C (PGT alone) to ~250 °C with CNF | +20 °C — improved thermal stability and adsorption | Heavy metal adsorption, environmental cleanup [62,63,64] |

| Poly(glycerol sebacate) electrospun fiber | Chitin-lignin sol–gel + 15 % PGS | Tₘ decreased from 9.6 °C to ~66 °C (peak attributed to sol–gel), T_c ~49.7 °C; mechanical strength ↑ from ~1.2 MPa to ~3.1 MPa | Slight reduction in melting/crystallization temps; mechanical and antibacterial boost | Wound-healing scaffolds [65,66] |

| Polyglycerol-based polyurethane adhesive | Sodium silicate (waterglass) | Thermally stable below ~260 °C with Tₘ ~280 °C (TGA onset ≈ 260 °C) | +~40 °C early strength stability; flame resistance | Grouting & structural adhesives [67] |

| PGS biodegradable composite with gelatin + GO | Gelatin, graphene oxide | T₅% increased from ~250 °C to ~270–280 °C | +20–30 °C; enhanced thermal & mechanical performance | Tissue engineering scaffolds [68] |

| Polynorbornene network | Crosslinked polynorbornene | Tₘ/GTT >310 K (≈37 °C); decomposition of blends at ≳320 °C | High thermal stability; decomposition onset >320 °C | Shape-memory; damping materials [69,70,71] |

| PEG-PG diacrylate network | Poly(ethylene glycol) diacrylate | T₅% >360 °C in semi-IPN/hydrogel networks | Strong network thermal stability (T₅% ≳360 °C) | PEMs, tissue engineering [72,73] |

| Polyglycerol urethane foam | Rigid PU foam from polyglycerol polyol | Multi-stage T₅% ~250–350 °C; second stage ~400–600 °C | Typical PU thermogram; urethane bonds decompose at ≳250 °C | Thermal insulation, lightweight bio-foam [74,75,76] |

| Polyglycerol dodecanedioate | Poly(glycerol dodecanedioate) (PGD) | Shape memory T_trans ≈ 37 °C; degradation onset ~200–250 °C | Transition near body temp; thermally stable for biomedical use | Minimally invasive devices, SMPs [60,77,78,79,80] |

| Property | PLA | PCL | PEGDA | Polyglycerol (PGS) |

| Tensile Modulus | 2000-3000 MPa [114] | 300-400 MPa [115] | 1-10 MPa [116] | 0.05-1.5 MPa [12] |

| Elongation at Break | 4-10% [114] | 300-1000% [114] | 5-15% [116] | 200-450% [12] |

| Glass Transition (Tg) | 55-65°C [114] | (-65)-(-60)°C [114] | (-20)-0°C [116] | (-40)-(-10)°C [116] |

| Degradation Rate* | 12-24 months [114] | 24-36 months [114] | PEGDA is typically non-degradable under physiological conditions, though degradable variants have been synthesized through labile linkers. | 1-6 months [12] |

| AM Printability | Excellent [114] | Good [115] | Excellent [116] | Moderate-Good [12] |

| Material Modification | Glass Transition Temperature (ΔTg) vs. Baseline | Maximum Service Temperature | Key Effect |

| Unmodified PGS (baseline) | Tg ≈ −20°C to −10°C [88,119] | 40-50°C [88,119] | Reference |

| Citrate crosslinking | +15-20°C (Tg ≈ −5°C to +10°C) [88] | 60-70°C [88] | Enhanced thermal resistance |

| Norbornene functionalization | +10-15°C (Tg ≈ 0°C to +5°C) [120] | 55-65°C [120] | Improved UV curability |

| PCL blending (20-40 wt%) | +5-10°C (Tg ≈ −15°C to 0°C) [121] | 50-60°C [121] | Balanced elasticity |

| Property | PLA/PCL Blends | PEGDA Systems | Polyglycerol Systems |

| Shape-recovery ratio | 94-99% [124] | 75-90% [125] | 100% [126] |

| Creep strain | 6-10% [127] | 10-18% [128] | 3-8% [126] |

| Recovery stress (MPa) | 12.85 [124] | Not reported | 0.180-0.250 [79] |

| Sample | System | Trigger Stimulus | Recovery Time (s) | Shape Fixing Ratio (%) | Shape Recovery Ratio (%) |

| PGS Elastomer | Poly(glycerol sebacate) | Heat (50 °C) | Not reported |

98% |

97% |

| PGS/Silica Nanocomposite | PGS + Silica Nanoparticles | Heat (60 °C) | ~20 | Not reported | 100% |

| Polynorbornene Network | Norbornene-modified Polymer | Heat (45 °C) | Not reported | >99% | >90% |

| PEG-PG Diacrylate | Polyglycerol Diacrylate Network | UV (365 nm) | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported |

| Polyglycerol Urethane Foam | Polyglycerol–Isocyanate Foam | Compressive Release | ~2400 | 99.2% ± 0.2% | 99.3% ± 0.8% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).