Optimizing Muscle Hypertrophy and Mobility through Deep Stretch and Optimal Resistance Exercises

Traditional resistance training has long prioritized load progression and volume as the primary drivers of muscle hypertrophy (Schoenfeld, 2010). However, as our understanding of biomechanics and physiology evolves, research suggests that hypertrophy is influenced by more than just lifting heavier weights. Factors such as exercise execution, range of motion, and muscle length at peak tension significantly impact muscle growth (Warneke et al., 2023). While bodybuilders have instinctively utilized deep stretches in their training for decades, scientific research is only now beginning to confirm the hypertrophic benefits of this practice (Maeo et al., 2023).

Similarly, mobility training has often been treated as a separate discipline, distinct from strength and hypertrophy-focused training. Conventional mobility routines emphasize passive stretching or dynamic drills that may improve flexibility but lack the mechanical tension necessary for meaningful muscle adaptation (Behm et al., 2021). This has led to a widespread misconception that mobility and hypertrophy are opposing goals—when in reality, properly structured resistance training can enhance both simultaneously. Research indicates that stretching under load increases muscle length and enhances joint function, making it a valuable tool for mobility development (Kubo et al., 2021).

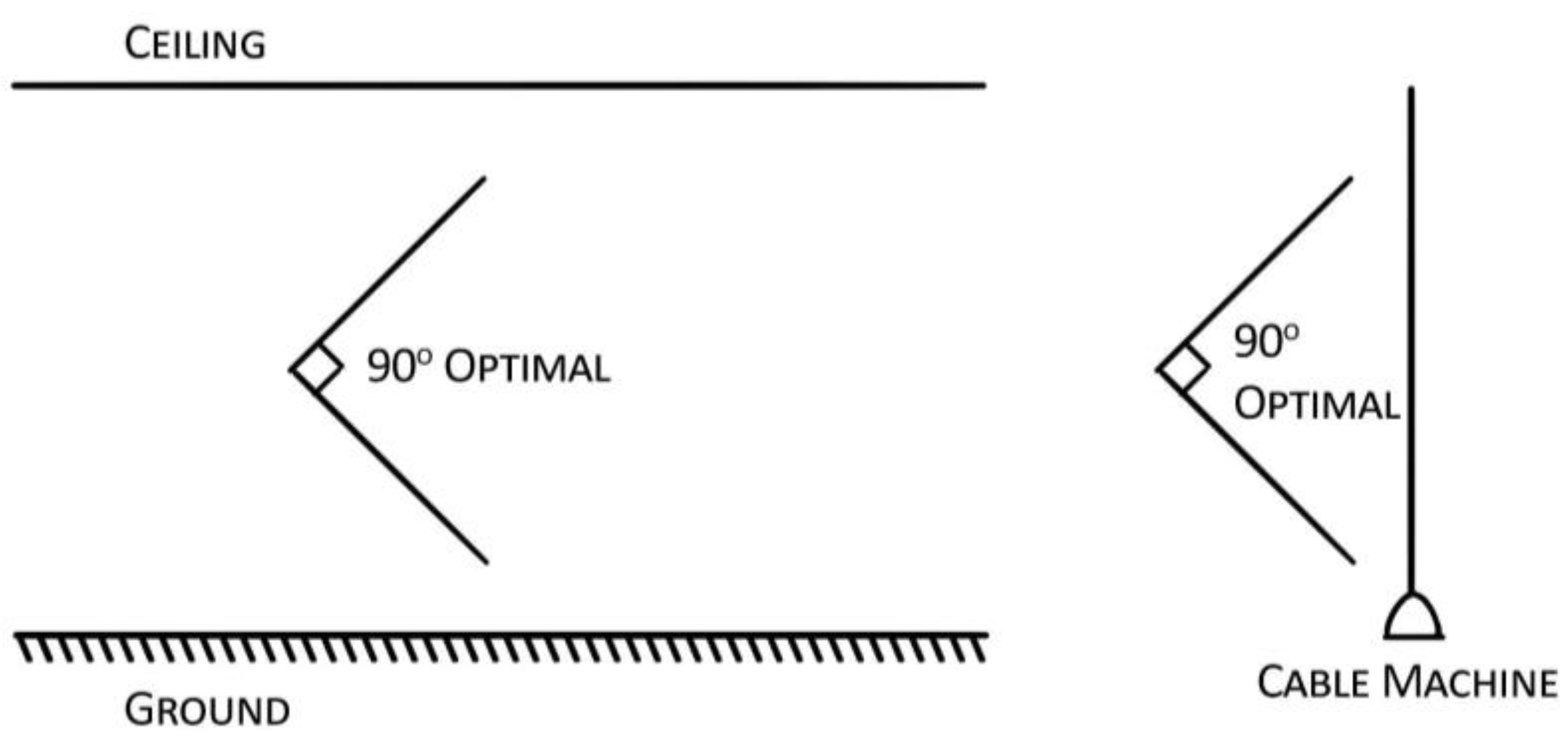

To bridge this gap, this paper explores how resistance training can be optimized to improve both muscle hypertrophy and mobility through a strategic approach that prioritizes deep muscle stretch and optimal resistance angles. As illustrated in

Figure 1, positioning the resistance at an optimal 90-degree angle relative to the force source—specifically within a range of 45 to 135 degrees—maximizes tension on the muscle throughout its range of motion. By understanding the biomechanics behind these principles and applying them to exercise selection and execution, individuals can maximize both muscular development and joint function. This framework redefines how resistance training can be structured, offering a more comprehensive approach to strength, size, and movement quality.

Deep Stretch in Resistance Training

A deep stretch in resistance training refers to positioning a muscle in its lengthened state under tension before initiating contraction. Unlike passive stretching, where the muscle is elongated without resistance, a deep stretch occurs when external load is applied at the muscle’s extended position, creating mechanical tension (McMahon et al., 2014). This approach has gained attention due to its implications for both muscular hypertrophy and mobility, as it forces the muscle to work through its full range of motion under resistance.

During movement, a muscle generates force through three primary phases: eccentric (lengthening), isometric (holding), and concentric (shortening) (Schoenfeld et al., 2021). The eccentric phase, particularly when emphasizing a deep stretch, induces high levels of mechanical stress, which plays a key role in muscle remodeling and adaptation (Warneke et al., 2023). Furthermore, maintaining a deep stretch under tension stimulates the muscle-tendon unit, leading to long-term adaptations that improve flexibility and joint mobility (Kubo et al., 2021)

The ability to train at long muscle lengths is critical for both muscle growth and functional movement. Research indicates that hypertrophy is maximized when muscles are loaded in their lengthened position due to increased mechanical tension and muscle fiber recruitment (Maeo et al., 2023). Additionally, stretching under resistance improves mobility by increasing the active range of motion (ROM), which enhances joint function and movement efficiency (Behm et al., 2021). These dual benefits make deep stretch training a highly effective approach for individuals seeking both muscular development and improved mobility.

In the following sections, we will explore how a deep stretch contributes specifically to hypertrophy and mobility, detailing the physiological mechanisms and practical applications of this method.

Deep Stretch and Muscular Hypertrophy

Muscle hypertrophy is primarily driven by mechanical tension, metabolic stress, and muscle damage (Schoenfeld, 2010). Among these mechanisms, mechanical tension is considered the most crucial, as it directly stimulates muscle fibers to grow by increasing intracellular signaling for protein synthesis (Wackerhage et al., 2019). Recent research suggests that stretch-mediated hypertrophy, where muscles experience sustained tension at long lengths, may be one of the most effective ways to induce muscle growth (Warneke et al., 2023). This concept challenges traditional resistance training, which often focuses on mid-range movements, by emphasizing the importance of training muscles at their lengthened positions.

Stretch-mediated hypertrophy occurs when muscle fibers are placed under load in an extended position, increasing mechanical stress and promoting greater activation of high-threshold motor units (McMahon et al., 2014). Compared to training at shorter muscle lengths, performing resistance exercises at long muscle lengths has been shown to produce superior hypertrophic adaptations (Kassiano et al., 2023). In a systematic review and meta-analysis, Pedrosa et al. (2023) demonstrated that resistance exercises performed in a lengthened position resulted in greater muscle hypertrophy than those performed at shorter muscle lengths, even when total training volume was equated. These findings suggest that stretching under load increases sarcomerogenesis, the process by which muscle fibers add sarcomeres in series, ultimately leading to greater muscle length and cross-sectional area (Kassiano et al., 2023). This adaptation is particularly evident in movements such as deep squats, Romanian deadlifts, and overhead triceps extensions, where muscles experience sustained tension in their stretched position.

The eccentric phase of resistance exercises, which involves lengthening a muscle under load, has been shown to produce high levels of mechanical tension and muscle damage, both of which contribute to hypertrophy (Schoenfeld et al., 2017). Deep stretch during the eccentric phase increases passive tension within the muscle, leading to greater force production during subsequent contractions (Warneke et al., 2023). This increased tension is thought to enhance muscle activation and recruitment, particularly when resistance is aligned at optimal angles, such as the 90-degree force vector illustrated in

Figure 1. Research indicates that aligning resistance with the muscle’s natural force curve allows for more consistent tension throughout the range of motion, further maximizing hypertrophic adaptations (Pedrosa et al., 2023).

Multiple studies have compared training at long versus short muscle lengths, consistently showing superior muscle growth in lengthened position training (Kassiano et al., 2023; Pedrosa et al., 2023). For instance, Pedrosa et al. (2023) found that training the quadriceps with deep squats resulted in significantly greater hypertrophy compared to partial squats, despite both protocols utilizing similar loads. Likewise, research on hamstring development has shown that exercises like the Romanian deadlift, which place the muscle under deep stretch, lead to greater hypertrophy than conventional deadlifts that emphasize mid-range loading (Kassiano et al., 2023). These findings suggest that deep stretch training not only improves muscle growth but may also contribute to enhanced mobility by increasing the active range of motion in key movement patterns.

The practical application of these findings is critical for optimizing hypertrophy in resistance training. To fully leverage deep stretch hypertrophy, resistance training programs should incorporate exercises that place muscles in a lengthened state under load, emphasize the eccentric phase with slow and controlled movements, and train at optimal angles that maintain consistent tension across the range of motion. Additionally, progressive overload within the deep stretch range should be prioritized to ensure continuous adaptation over time. By integrating these principles, resistance training can maximize hypertrophic potential while simultaneously improving mobility, a concept that will be explored in the following section.

Deep Stretch and Mobility

Mobility is a critical component of physical performance, encompassing a joint’s ability to move freely through its full range of motion while maintaining control and stability. Unlike flexibility, which refers to passive elongation of a muscle, mobility involves both active movement and strength within extended ranges (Behm et al., 2021). Traditional mobility training often emphasizes dynamic stretching and joint mobilization drills; however, recent research suggests that deep stretch resistance training may be one of the most effective ways to enhance both mobility and functional movement patterns (Kubo et al., 2021). By placing muscles and joints under load in their lengthened position, deep stretch training can increase both muscle extensibility and neuromuscular control, leading to long-term improvements in movement capacity.

One of the primary mechanisms through which deep stretch contributes to mobility is by inducing adaptations in the muscle-tendon unit. When muscles are loaded at long lengths, the connective tissues, such as tendons and fascia, experience mechanical stress, leading to increased tissue compliance over time (Kubo et al., 2021). This process enhances the ability of the muscle to elongate while maintaining tension, allowing for greater movement efficiency and injury resilience. Research indicates that training with an emphasis on long muscle lengths improves not only passive range of motion but also active control of that range, which is crucial for mobility-dependent activities such as squatting, lunging, and overhead reaching (McMahon et al., 2014).

Another key factor in mobility enhancement through deep stretch training is the role of eccentric loading. The eccentric phase of an exercise—where the muscle lengthens under load—has been shown to increase muscle fiber length by stimulating sarcomerogenesis, or the addition of sarcomeres in series (Pedrosa et al., 2023). This structural adaptation not only contributes to hypertrophy but also enhances the muscle’s ability to generate force at extended positions, effectively expanding the functional range of motion (Kassiano et al., 2023). For example, deep squats performed with controlled eccentric loading have been shown to increase hip and ankle mobility by progressively strengthening muscles at their longest lengths, reducing movement restrictions over time (Warneke et al., 2023).

Furthermore, training at long muscle lengths under resistance has been linked to improvements in neuromuscular coordination, another critical component of mobility. When a muscle is repeatedly exposed to high levels of mechanical tension in a stretched position, the nervous system adapts by improving motor unit recruitment and intermuscular coordination (Schoenfeld et al., 2017). These adaptations enhance movement efficiency, reducing compensatory patterns and improving stability across joints. As a result, individuals who incorporate deep stretch resistance training into their regimen may experience greater ease in performing complex movements that require both strength and mobility, such as Olympic weightlifting, gymnastics, and functional fitness exercises.

The practical implications of these findings suggest that deep stretch training can serve as both a hypertrophy and mobility stimulus when integrated into resistance training programs. Exercises such as Romanian deadlifts, deep squats, overhead triceps extensions, and incline dumbbell curls all place muscles in their lengthened position under load while simultaneously reinforcing joint control. Additionally, by aligning resistance with the muscle’s optimal force curve, as illustrated in

Figure 1, trainees can ensure consistent tension across the range of motion, maximizing both strength and mobility adaptations. Given these benefits, deep stretch training offers a highly efficient method for improving both muscular development and movement capacity, challenging traditional views that separate hypertrophy training from mobility work.

Optimal Resistance Angles in Resistance Training

The concept of optimal resistance angles in resistance training refers to aligning the force applied to a muscle with its most mechanically efficient position for generating tension. Traditional resistance training often focuses on movement patterns without considering the biomechanics of how muscles generate force at different angles. However, research suggests that the angle at which resistance is applied significantly impacts both muscle activation and hypertrophy outcomes (Schoenfeld, 2010). By understanding how to position resistance optimally throughout an exercise, individuals can maximize mechanical tension while minimizing inefficiencies in force production.

Resistance is most effectively applied when it aligns perpendicular to the muscle’s primary line of force, which generally occurs at a 90-degree angle relative to the source of resistance (Wackerhage et al., 2019). This principle is particularly relevant when using free weights, cables, and machines, as variations in body positioning and equipment setup can dramatically alter the muscle’s ability to maintain tension. As illustrated in

Figure 1, the optimal resistance range typically falls between 45 and 135 degrees relative to the resistance source, ensuring that tension remains high throughout the range of motion while preventing unnecessary joint strain.

The implications of training with optimal resistance angles extend beyond hypertrophy, as they also play a crucial role in mobility and joint function. Research indicates that muscles trained at mechanically advantageous angles experience greater force output and improved neuromuscular efficiency, leading to enhanced movement quality and injury prevention (Kubo et al., 2021). Additionally, aligning resistance with the muscle’s strongest force curve can improve joint stability and movement mechanics, reducing compensatory patterns that contribute to joint wear and muscular imbalances (Behm et al., 2021).

In the following sections, the role of optimal resistance angles will be explored in the context of both hypertrophy and mobility. The hypertrophy discussion will focus on how training at mechanically efficient angles increases muscle recruitment, maximizes mechanical tension, and enhances stretch-mediated hypertrophy. The mobility discussion will examine how optimizing resistance angles reduces strain on joints, improves active range of motion, and enhances functional movement patterns. Together, these principles offer a refined approach to resistance training that integrates both strength and mobility into a cohesive framework.

Optimal Resistance Angles and Muscular Hypertrophy

Muscle hypertrophy is largely driven by mechanical tension, which is maximized when resistance is applied in alignment with a muscle’s most efficient force production capacity (Schoenfeld, 2010). The concept of optimal resistance angles refers to positioning resistance so that peak tension occurs at the point where the muscle is best positioned to generate force. This principle is particularly relevant in resistance training, as improper force alignment can lead to reduced muscle activation, inefficient load distribution, and suboptimal hypertrophic adaptations (Wackerhage et al., 2019). Research suggests that the most effective resistance occurs when the muscle is working against a force that is applied perpendicular to its primary line of pull, which typically falls within the 45- to 135-degree range relative to the resistance source (Pedrosa et al., 2023).

One of the key reasons optimal resistance angles enhance hypertrophy is their role in maintaining consistent mechanical tension throughout the movement. Traditional resistance training often results in fluctuations in tension, with certain phases of an exercise experiencing significantly less resistance. For example, in a standing dumbbell lateral raise, peak resistance occurs when the arms are parallel to the floor due to the force of gravity, but resistance diminishes near the start and end of the movement. In contrast, a cable lateral raise, when set at the appropriate angle, maintains more consistent tension throughout the range of motion, leading to greater muscle activation and increased time under tension, both of which contribute to hypertrophy (Kassiano et al., 2023).

Another critical factor in hypertrophy is the relationship between muscle length and resistance alignment. When resistance is applied at an optimal angle, muscles experience greater activation at long muscle lengths, a key factor in stretch-mediated hypertrophy (McMahon et al., 2014). Studies have demonstrated that exercises performed with optimal force alignment at longer muscle lengths lead to superior hypertrophy compared to exercises that emphasize mid-range or shortened positions (Warneke et al., 2023). For example, Pedrosa et al. (2023) found that training the quadriceps with deep squats, where resistance remains high at greater knee flexion angles, resulted in more muscle growth than partial squats, where resistance diminishes before reaching full depth.

Research also indicates that aligning resistance optimally reduces unnecessary joint strain while increasing the efficiency of muscle recruitment (Behm et al., 2021). When resistance is misaligned, secondary muscle groups and joint structures absorb more of the force, reducing the load placed on the target muscle. This phenomenon is evident in free weight vs. cable resistance training, where cables allow for more precise manipulation of resistance angles to maintain consistent loading patterns (Kubo et al., 2021). By ensuring resistance remains perpendicular to the muscle’s natural line of pull, trainees can maximize hypertrophic stimuli while minimizing joint stress, making optimal resistance alignment particularly valuable for long-term progress and injury prevention.

The practical applications of these findings suggest that training with optimal resistance angles should be a fundamental consideration in program design. Exercises should be selected and modified to maintain consistent resistance throughout the range of motion, particularly in stretched positions where mechanical tension is highest. Adjusting resistance via body positioning, equipment selection, and exercise variation can further enhance hypertrophic outcomes by maximizing tension at the most mechanically advantageous points of movement. As discussed in the following section, these same principles that optimize hypertrophy also contribute to improved mobility by reinforcing joint function and neuromuscular efficiency.

Optimal Resistance Angles and Mobility

Mobility is often thought of as a passive trait, primarily influenced by flexibility, but recent research suggests that active mobility is significantly influenced by strength and neuromuscular control at extended ranges of motion (Behm et al., 2021). While traditional mobility work focuses on stretching and joint mobilization, resistance training at optimal angles can enhance mobility by reinforcing strength, stability, and control throughout a joint’s full range of motion (Kubo et al., 2021). Aligning resistance with the muscle’s most mechanically efficient position—typically within the 45- to 135-degree range relative to the resistance source—ensures that tension is distributed optimally throughout the movement. This leads to both greater joint stability and an expanded active range of motion, which are critical for functional mobility.

One of the key mechanisms through which optimal resistance angles enhance mobility is by promoting consistent muscle activation throughout an exercise’s entire range of motion (McMahon et al., 2014). When resistance is misaligned, certain portions of the movement may receive insufficient mechanical tension, leading to imbalances in strength and mobility across different joint angles. For example, in free-weight Romanian deadlifts, the hamstrings experience high tension at the bottom position but minimal resistance near full extension due to gravitational force limitations. In contrast, when the same movement is performed using cables or resistance bands aligned at an optimal angle, the hamstrings maintain consistent loading throughout the entire movement, reinforcing strength in both stretched and contracted positions. This approach has been shown to improve eccentric control, muscle-tendon elasticity, and joint stability, all of which contribute to enhanced mobility (Pedrosa et al., 2023).

Another critical factor in mobility is neuromuscular coordination and proprioception. Training with optimal resistance angles allows for more precise control of joint movement, reducing the risk of compensatory patterns that lead to mobility restrictions and injury over time (Kassiano et al., 2023). For instance, in overhead pressing movements, resistance applied at an inefficient angle can place excessive strain on the shoulder joint, forcing secondary muscles to compensate for the lack of mechanical advantage. By adjusting resistance to align with the shoulder’s natural force curve, the movement becomes more stable and controlled, allowing the joint to move through its full range safely and effectively. This is particularly relevant for individuals recovering from injuries or those looking to prevent joint degradation through proper movement mechanics (Warneke et al., 2023).

Additionally, joint stability is enhanced when muscles are strengthened at their end ranges, which is a fundamental principle of mobility development (Schoenfeld et al., 2017). Training at optimal resistance angles ensures that muscles experience mechanical tension even in stretched positions, reinforcing strength at extended joint angles. This adaptation is particularly beneficial for athletic performance and injury prevention, as many sport-specific movements—such as sprinting, jumping, and cutting—require high force production at extreme joint positions (Pedrosa et al., 2023). For example, deep squats with properly aligned resistance have been shown to improve ankle, knee, and hip mobility, as they allow the joints to adapt under controlled load while maintaining proper structural alignment (Kubo et al., 2021).

The integration of optimal resistance angles into mobility training challenges conventional approaches that separate strength training from mobility work. Rather than viewing mobility as purely flexibility-based, this framework highlights the importance of resistance applied at mechanically advantageous angles to reinforce strength, neuromuscular control, and joint function across a full range of motion. As a result, training at optimal resistance angles provides a dual benefit—enhancing both hypertrophy and mobility—making it a highly efficient approach for improving overall movement capacity while reducing the risk of movement-related dysfunctions.

Muscle Types and Their Relationship to Deep Stretch and Optimal Resistance Angles

Understanding muscle function in the context of deep stretch and optimal resistance angles requires an examination of how different muscle groups respond to mechanical tension across various movement patterns. While all muscles operate based on the principles of force production and length-tension relationships, they can be categorized into three primary types based on their biomechanical properties and functional movement roles. These categories—bidirectional muscles, neutral-stretched muscles, and active-stretched muscles—help determine the most effective exercise selection and resistance application for maximizing both hypertrophy and mobility.

Bidirectional muscles allow for movement in both forward and backward directions from a neutral resting position, meaning they can achieve deep stretches on one end of the movement and strong contractions on the other. Examples include the deltoids, pectorals, lats, and glutes, which function dynamically through multi-directional movement patterns. Neutral-stretched muscles, on the other hand, experience their natural stretch in a fully extended position, such as the quadriceps and biceps, where the muscle reaches peak elongation without needing external force to move it into a stretched state. Lastly, active-stretched muscles require external positioning or specific movement adjustments to achieve a deep stretch under load. These include muscles such as the hamstrings and triceps, which do not naturally enter a stretched position without intentional positioning and movement adjustments.

Recognizing these three muscle classifications allows for a more targeted approach to resistance training, ensuring that exercises are selected and executed in a way that optimally loads each muscle group at the correct angles and in the most mechanically advantageous positions. In the following sections, each muscle type will be examined in detail, along with specific exercises that align with the deep stretch and optimal resistance angle principles discussed earlier. By structuring exercises according to the unique characteristics of these muscle types, training programs can more effectively maximize hypertrophy, mobility, and overall movement efficiency.

Bidirectional Muscles

Bidirectional muscles are those that facilitate movement in both forward and backward directions from a neutral position, allowing for a deep stretch on one end of the movement and a strong contraction on the other. These muscles play a critical role in multi-directional movement patterns, making them essential for both hypertrophy and mobility. Because they operate across a wide range of motion, training them effectively requires exercises that maximize mechanical tension throughout both the stretched and contracted phases while ensuring that resistance is applied at an optimal angle.

Muscles in this category include the deltoids, pectorals, latissimus dorsi, trapezius, abdominals, forearms, calves, and glutes. These muscles contribute to movements such as pressing, pulling, shrugging, and rotational patterns, where proper alignment of resistance angles and deep stretch loading can significantly enhance both muscle growth and functional range of motion. Since bidirectional muscles experience a full stretch in one direction and a forceful contraction in the opposite, the selection of exercises should emphasize both ends of this movement spectrum to optimize training adaptations.

The following sections will detail specific exercises for bidirectional muscles, demonstrating how to incorporate deep stretch principles and optimal resistance angles to maximize hypertrophy and mobility. Each exercise is structured to align with the biomechanics of the muscle group, ensuring that training remains effective, safe, and efficient.

Chest Flys (Thoracic Muscles)

The dumbbell chest fly is a highly effective exercise for targeting the pectoralis major, allowing for a deep stretch at the bottom of the movement while maintaining an optimal resistance curve throughout the range of motion. When performed with free weights, resistance is primarily dictated by gravity, making the stretched position at the bottom of the movement, as seen in

Figure 2, the most mechanically challenging. To begin, the lifter lies flat on a bench with a dumbbell in each hand, arms fully extended above the chest. The eccentric phase involves lowering the dumbbells in a wide arc while keeping a slight bend in the elbows, allowing the chest muscles to lengthen under tension. Once the dumbbells reach the lowest position, where the pectorals experience maximum stretch, as seen in

Figure 3, the lifter initiates the concentric phase by bringing the weights back together in a controlled manner. Because gravity provides minimal resistance at the top of the movement, tension diminishes as the dumbbells approach the starting position. As a result, while the dumbbell chest fly is excellent for deep stretch-mediated hypertrophy, it lacks consistent tension throughout the entire movement.

The cable chest fly, by contrast, maintains constant resistance throughout the entire range of motion, making it a more biomechanically efficient alternative. Unlike free weights, which rely on gravity, the cable pulley system provides resistance in a horizontal plane, ensuring that the chest remains under tension in both the stretched, as seen in

Figure 4, and contracted positions, as seen in

Figure 5. The setup involves standing between two cable pulleys set at chest height, holding the handles with arms extended outward. The lifter then steps forward slightly to create an initial pre-stretch, allowing for immediate activation of the pectorals. The movement mirrors that of the dumbbell fly, with the arms moving through a wide arc before returning to the starting position. However, because the cables maintain resistance throughout the entire range, the top portion of the movement—where tension is lost in free-weight variations—still provides substantial mechanical load. This continuous tension enhances both hypertrophy and mobility by reinforcing strength at both the stretched and contracted muscle lengths, making the cable fly a superior choice for overall pectoral development while still leveraging the deep stretch benefits of the dumbbell variation.

Front Raises (Anterior Deltoids)

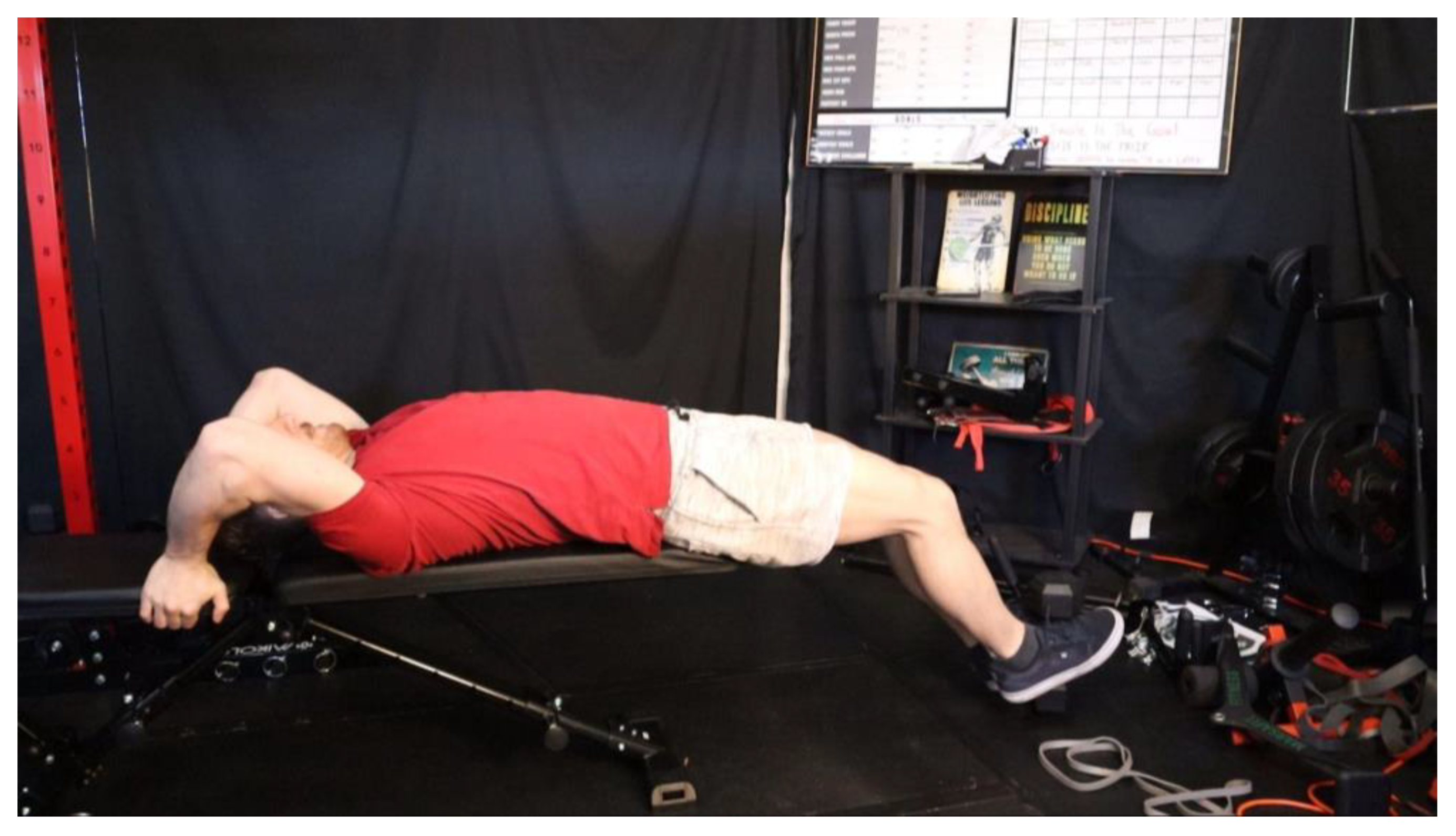

The dumbbell front raise primarily targets the anterior deltoid, allowing for a deep stretch when performed in a lying position. Unlike the traditional standing variation, which experiences resistance fluctuations due to gravity, the lying front raise maintains a stronger stretch component at the bottom of the movement. To begin, the lifter lies face-up on a flat bench with a dumbbell in each hand, arms fully extended toward the floor, as seen in

Figure 6. The concentric phase involves lifting the dumbbells in front of the body until the arms reach a 45-degree angle, keeping a slight bend in the elbows while focusing on controlled movement. The eccentric phase is particularly important, as the lifter slowly lowers the dumbbells back toward the floor, emphasizing a deep stretch in the anterior deltoid, as seen in

Figure 7. At the lowest point, the deltoid remains under high mechanical tension, making this variation highly effective for stretch-mediated hypertrophy. However, similar to the dumbbell chest fly, resistance diminishes at the top of the movement, where the deltoid is least engaged due to the effects of gravity.

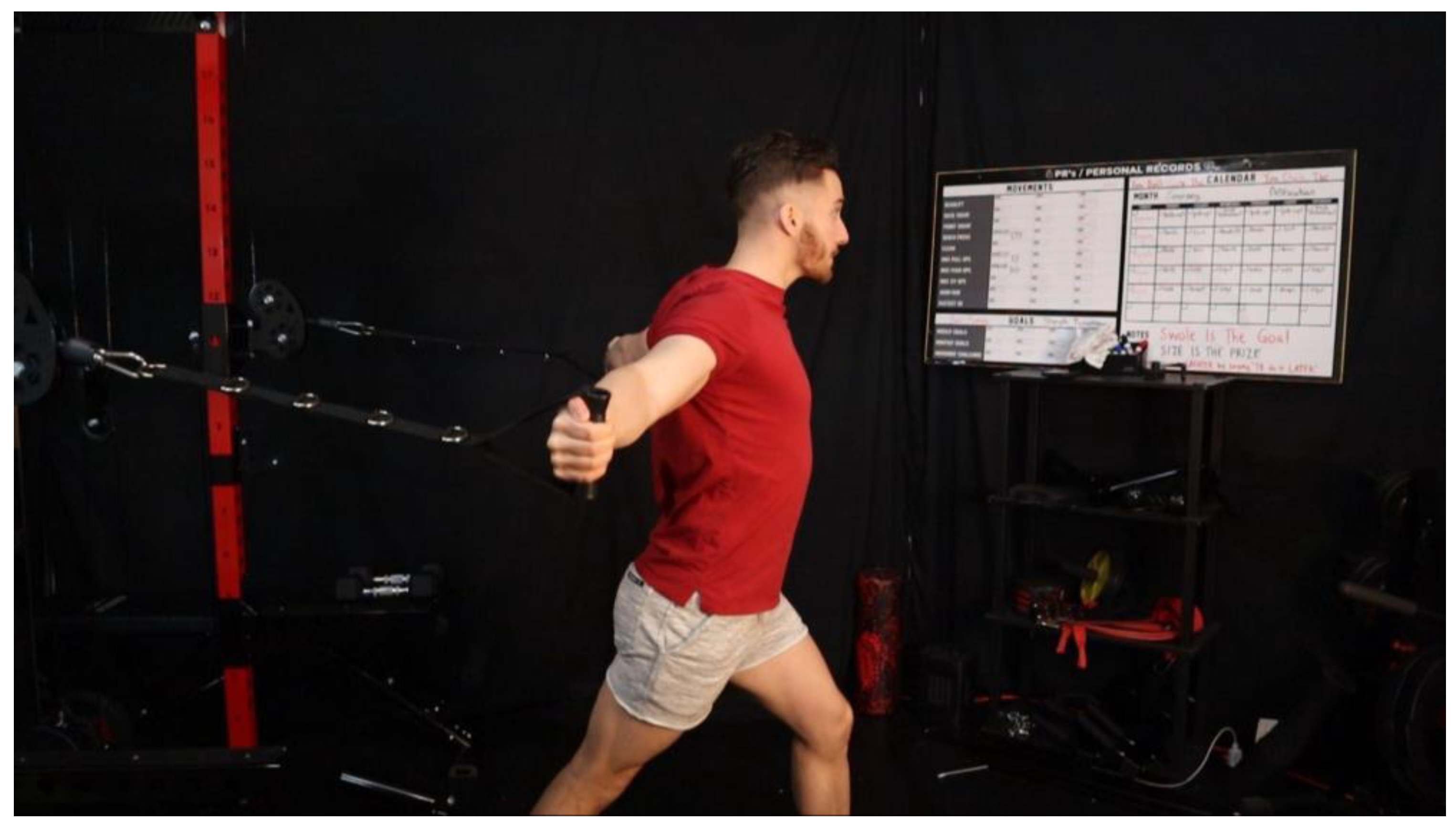

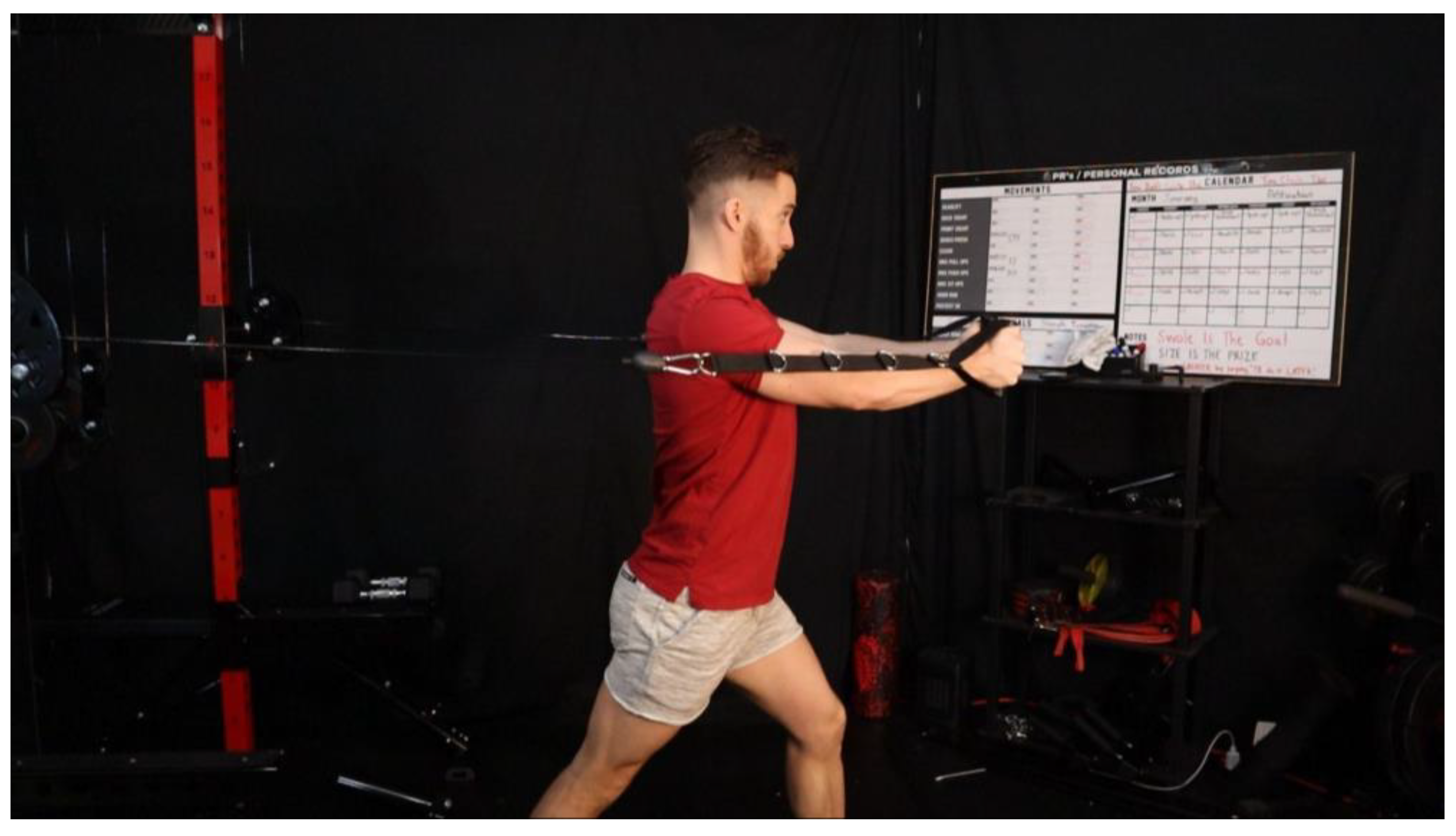

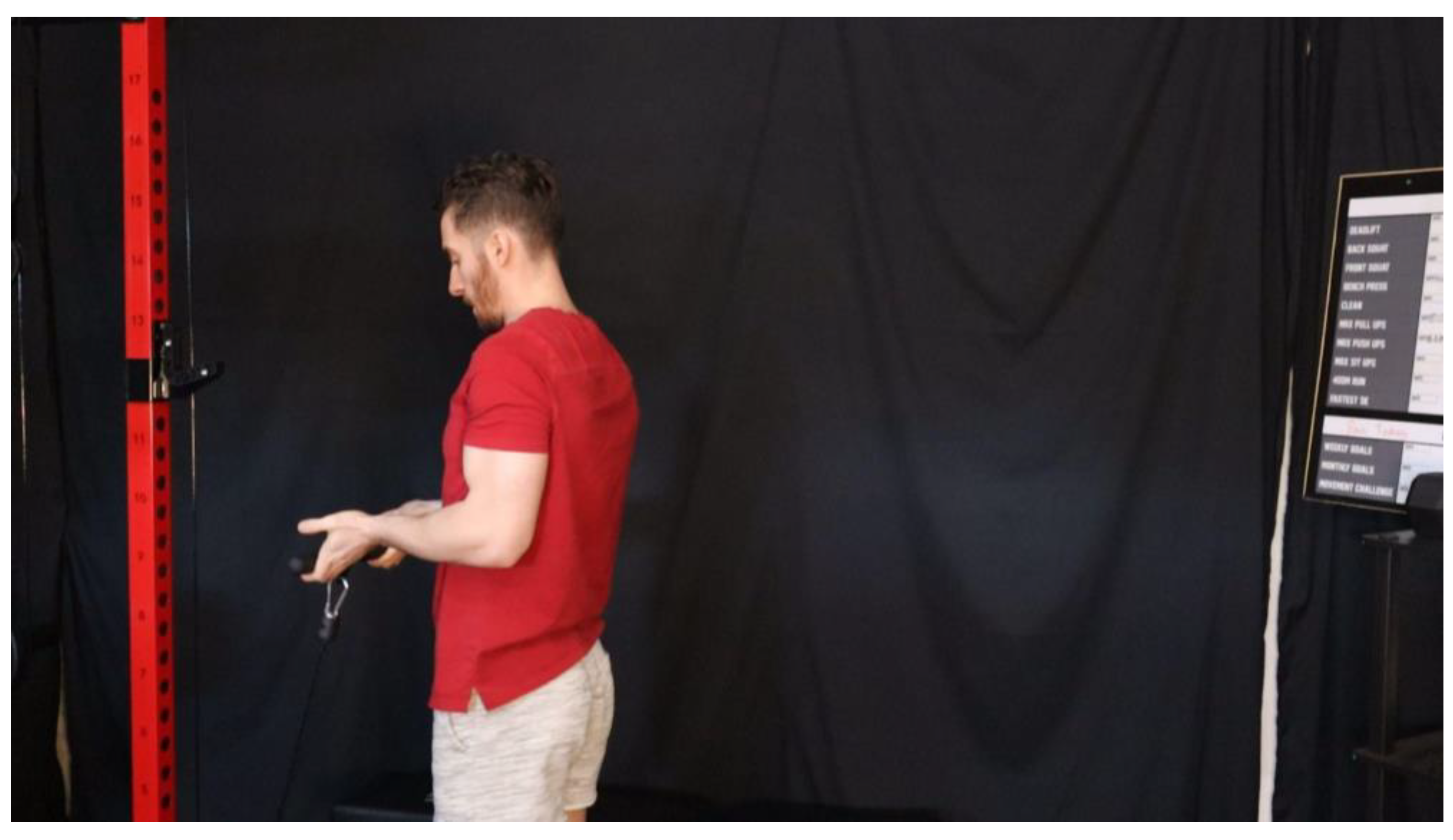

In contrast, the cable front raise maintains consistent resistance throughout the range of motion, ensuring the anterior deltoid remains under tension in both the stretched, as seen in

Figure 8, and contracted positions, as seen in

Figure 9. To perform the movement, the lifter stands facing away from the cable machine, holding a handle with each hand while the pulleys are set at hand height. By stepping forward slightly, the initial pre-stretch of the deltoids is established before initiating the raise. The movement follows the same pattern as the dumbbell version, with the concentric phase involving a smooth forward raise and the eccentric phase lowering the arms back to the stretched position. Unlike the free-weight variation, where resistance drops at the top, the cable machine maintains tension throughout the movement, making it more effective for maximizing hypertrophy and mobility. Additionally, the ability to adjust cable height and body positioning allows for precise control over resistance angles, ensuring that the anterior deltoid is consistently challenged at its strongest mechanical points.

Lateral Raises (Lateral Deltoids)

The dumbbell lateral raise targets the lateral deltoid, playing a key role in shoulder width and overall upper body aesthetics. When performed in a lying position, this exercise allows for a deep stretch at the start of the movement, enhancing hypertrophic adaptations. To begin, the lifter lies sideways on a flat bench, holding a dumbbell in the working hand with the arm fully extended in front of the body, as seen in

Figure 10. The concentric phase involves raising the dumbbell in an arc away from the body until the arm reaches approximately 45 degrees relative to the torso, ensuring the lateral deltoid remains the primary mover. The eccentric phase is performed slowly, lowering the dumbbell back toward the front of the body to achieve a deep stretch in the stretched position, as seen in

Figure 11. Because gravity provides the highest resistance when the arm is parallel to the ground, tension is lost near the top of the movement, making this variation most effective for its stretch-mediated benefits rather than full-range tension consistency.

The cable lateral raise, however, ensures consistent resistance throughout the entire movement, making it a more mechanically efficient option for continuous tension. To set up, the lifter stands next to a cable machine with the pulley set at hand height, grabbing the handle with the working arm. By positioning the body slightly away from the machine, the stretched position, as seen in

Figure 12, is established before beginning the movement. The concentric phase involves lifting the arm in a wide arc until it reaches shoulder height, while the eccentric phase focuses on controlled lowering back to the fully stretched position, as seen in

Figure 13. Unlike free weights, the cable’s resistance remains constant throughout the movement, keeping the lateral deltoid under tension at both its shortest and longest muscle lengths. This feature makes the cable lateral raise superior for hypertrophy and mobility, as it reinforces both isometric strength at peak contraction and eccentric loading in the stretched position. Additionally, slight adjustments in body positioning and cable angle allow for precision in targeting the deltoid at optimal resistance angles, ensuring maximal muscle activation.

Rear Delt Flys (Posterior Deltoids)

The dumbbell rear delt fly is a key movement for targeting the posterior deltoid, which plays a crucial role in shoulder stability, posture, and upper body balance. When performed in a lying position, this exercise emphasizes a deep stretch at the start, optimizing tension in the posterior deltoid fibers. The lifter begins by lying sideways on a flat bench, holding a dumbbell in the working hand with the arm fully extended in front of the body, as seen in

Figure 14. The concentric phase consists of lifting the dumbbell in an arc away from the body until the arm is perpendicular to the torso, ensuring full engagement of the rear deltoid fibers. During the eccentric phase, the dumbbell is slowly lowered back to the stretched position, as seen in

Figure 15, where the posterior deltoid experiences maximum elongation under tension. However, similar to other free-weight variations, gravity dictates the resistance curve, meaning that peak tension occurs in the mid-range of the movement while the top and bottom positions lose resistance.

The cable rear delt fly provides consistent resistance throughout the entire range of motion, making it a more effective alternative for hypertrophy and mobility development. To perform this variation, the lifter stands sideways next to a cable machine, with the pulley set at shoulder height. The working arm reaches across the body to grip the handle, creating the pre-stretched position, as seen in

Figure 16, before initiating the movement. The concentric phase involves pulling the handle away from the body in a wide arc, maintaining a slight bend in the elbow to isolate the rear deltoid. The eccentric phase is performed under control, slowly returning the arm to the stretched position, as seen in

Figure 17. Unlike free weights, the cable maintains tension across the entire range, ensuring that the rear deltoid remains activated from the beginning to the end of the movement. Additionally, subtle adjustments in body positioning and cable angle allow for precise resistance alignment, maximizing both stretch-mediated hypertrophy and active joint mobility.

Pullovers (Latissimus Dorsi)

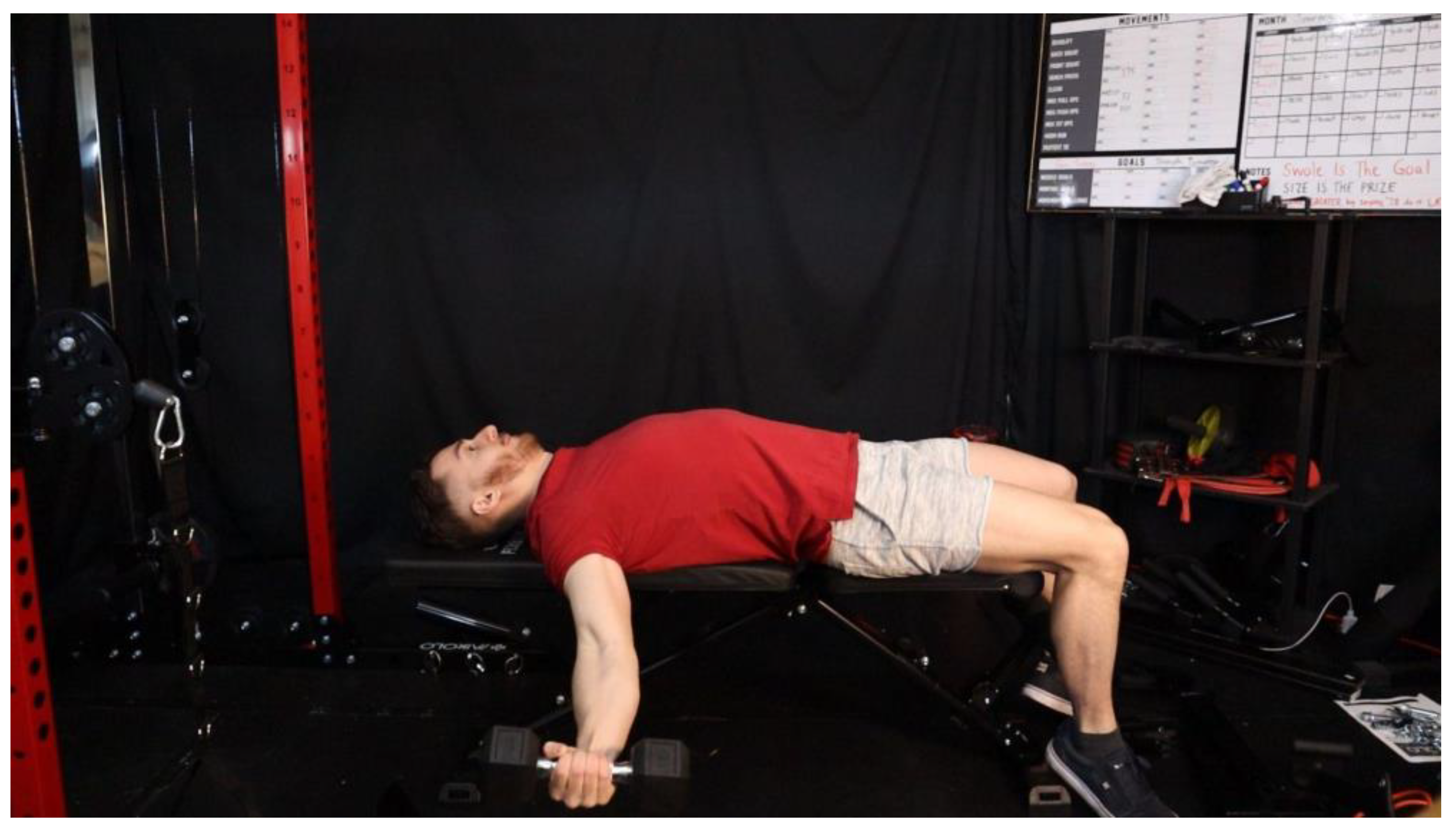

The dumbbell pullover is a highly effective exercise for developing the latissimus dorsi, emphasizing a deep stretch that promotes both hypertrophy and mobility. Unlike traditional rowing movements, which primarily target the mid-range of lat activation, the pullover allows for elongation of the lats under load, reinforcing strength in the fully stretched position. To begin, the lifter lies flat on a bench, holding a single dumbbell with both hands and extending the arms overhead toward the floor, as seen in

Figure 18. The eccentric phase involves lowering the dumbbell in a controlled arc behind the head, ensuring that the lats reach full extension while maintaining tension. At the bottom of the movement, as seen in

Figure 19, the muscle experiences maximum stretch, which enhances sarcomerogenesis and improves mobility in overhead positions. The concentric phase consists of bringing the dumbbell back toward the starting position, focusing on engaging the lats rather than relying on the chest or triceps. However, since gravity primarily acts downward, tension significantly decreases near the top of the movement, making this variation less effective for sustained resistance across the full range of motion.

The cable straight-arm pulldown offers a mechanically superior alternative, maintaining constant resistance throughout the movement. To perform this variation, the lifter stands facing a cable machine, using a straight bar or rope attachment with the pulley set at its highest point. By slightly leaning forward, the lifter creates an initial pre-stretch, as seen in

Figure 20, before beginning the movement. The concentric phase involves pulling the bar downward in a controlled arc, keeping the arms straight but not locked, until the hands reach the thighs, maximizing lat engagement. The eccentric phase consists of slowly returning the bar to the stretched position, as seen in

Figure 21, while maintaining control to ensure tension remains on the lats. Unlike the dumbbell variation, where tension diminishes at the top, the cable pullover keeps the lats activated throughout the entire range of motion, making it a more effective choice for hypertrophy and mobility. Additionally, adjusting body positioning and resistance angles allows for a more precise alignment with the muscle’s strongest force curve, ensuring optimal recruitment of the lat fibers in both the stretched and contracted positions.

Retraction Shrugs (Trapezius)

The dumbbell retraction shrug, also referred to as a back shrug, specifically targets the lower and mid-trapezius, emphasizing scapular retraction rather than the traditional upward shrugging motion associated with upper trapezius development. This movement is highly effective for improving postural strength, shoulder stability, and scapular control, making it beneficial for both hypertrophy and mobility. To begin, the lifter lies face-down on a flat or incline bench, holding a dumbbell in each hand with the arms extended toward the floor, as seen in

Figure 22. The concentric phase involves pulling the shoulder blades back and together, elevating the dumbbells slightly by retracting the scapulae without excessive arm movement. Unlike traditional shrugs, where the focus is on elevating the shoulders, this variation ensures that the mid and lower trapezius remain the primary movers. The eccentric phase consists of slowly returning the scapulae to the stretched position, as seen in

Figure 23, allowing the traps to lengthen under control. However, because gravity provides minimal resistance at the fully retracted position, this variation is most effective for reinforcing the stretch component rather than maintaining peak contraction tension.

The cable retraction shrug provides a more consistent resistance curve, ensuring that the trapezius remains engaged throughout the entire range of motion. To perform this variation, the lifter stands facing a cable machine, gripping two handles with the pulleys set at shoulder height. By slightly stepping backward, the lifter creates an initial pre-stretch, as seen in

Figure 24, before beginning the movement. The concentric phase involves pulling the handles backward, retracting the scapulae fully while keeping the arms extended. Unlike the dumbbell version, where resistance decreases at the top of the movement, the cable ensures continuous tension, maximizing muscle activation at full retraction. The eccentric phase consists of slowly returning to the stretched position, as seen in

Figure 25, while resisting the pull of the cable, reinforcing controlled scapular mobility. Additionally, slight adjustments in body positioning can fine-tune resistance angles, allowing for optimal trap activation while minimizing excessive arm involvement. This makes the cable retraction shrug a superior option for both hypertrophy and mobility, particularly for improving postural endurance and scapular control in overhead and pulling movements.

Crunches (Superior Rectus Abdominis)

The decline dumbbell crunch is a highly effective exercise for targeting the upper portion of the rectus abdominis, emphasizing spinal flexion and deep abdominal contraction. Unlike traditional crunches, which are often performed with limited range of motion, this variation enhances the stretch component by allowing the torso to extend past the edge of a bench or declined surface. To perform this movement, the lifter positions themselves on a decline bench, ensuring that their upper back and shoulders extend past the edge. Holding a dumbbell close to the chest, the movement begins with the torso fully extended downward, as seen in

Figure 26, creating a deep stretch in the upper abs. The concentric phase involves curling the torso upward toward the knees, ensuring that the abs, rather than momentum, drive the movement. At the top of the crunch, the lifter achieves full contraction of the abdominal muscles before slowly lowering back down to the stretched position, as seen in

Figure 27, in a controlled eccentric phase. Because gravity provides the highest resistance at the bottom, this variation is particularly effective for stretch-mediated hypertrophy, reinforcing both core strength and mobility in deep spinal flexion.

The cable decline crunch introduces a constant resistance component, making it a biomechanically superior alternative for sustained tension across the full range of motion. To perform this variation, the lifter lies on a decline bench or allows their upper back to extend past a flat bench, holding a rope attachment connected to a high pulley cable close to the head. Similar to the dumbbell variation, the movement starts in the fully extended position, as seen in

Figure 28, where the abs experience a deep stretch under load. The concentric phase involves curling the torso forward, bringing the chest toward the knees while maintaining continuous tension on the abs. Unlike free weights, where resistance diminishes at the top, the cable ensures tension remains constant, even in the contracted position, as seen in

Figure 29. The eccentric phase is performed slowly and under control, returning the torso to the stretched position to reinforce eccentric loading. Additionally, the ability to adjust cable height and resistance levels allows for precise loading progression, ensuring that the upper abs are effectively challenged in both their lengthened and shortened states. This makes the cable decline crunch a superior option for hypertrophy, mobility, and core endurance, particularly for individuals looking to develop a stronger, more resilient abdominal wall while reinforcing optimal spinal movement mechanics.

Reverse Crunches (Inferior Rectus Abdominis)

The decline dumbbell reverse crunch is an effective exercise for targeting the lower abdominal muscles, particularly the rectus abdominis. Unlike traditional leg raises, which involve significant hip flexor activation, the reverse crunch shifts the emphasis to the lower abs by minimizing hip flexor involvement and maximizing spinal flexion. To begin, the lifter lies on a decline bench, gripping the bench for stability while holding a dumbbell between the feet. The movement starts with the legs fully extended downward, as seen in

Figure 30, creating a deep stretch in the lower abdominal region. The concentric phase involves bringing the knees toward the chest, curling the pelvis upward to fully engage the lower abs. Unlike exercises where the legs remain straight, this variation ensures that spinal flexion rather than hip flexion is the primary driver of the movement. The eccentric phase consists of slowly lowering the legs back down to the stretched position, as seen in

Figure 31, while maintaining control, ensuring that tension remains on the lower abs rather than shifting to the hip flexors. Because gravity provides significant resistance at the bottom of the movement, the decline dumbbell reverse crunch is particularly effective for developing strength at long muscle lengths, reinforcing both hypertrophy and mobility in the lower abdominal region.

The cable decline reverse crunch provides a more consistent resistance curve, ensuring that the lower abs remain under tension throughout the movement. To perform this variation, the lifter lies on a decline bench with the feet attached to a low pulley cable via ankle straps or a specialized attachment. Similar to the dumbbell version, the movement begins with the legs fully extended downward, as seen in

Figure 32, allowing the abs to experience a deep stretch under resistance. The concentric phase consists of pulling the knees toward the chest, engaging the lower abs to curl the pelvis upward rather than simply lifting the legs. The eccentric phase is performed in a controlled manner, extending the legs back to the stretched position, as seen in

Figure 33, while resisting the pull of the cable. Unlike the free-weight version, where resistance diminishes at the top, the cable variation ensures that tension remains constant throughout the entire movement, maximizing lower abdominal activation. Additionally, subtle adjustments in body positioning and bench angle allow for precise resistance alignment, ensuring optimal lower ab recruitment without excessive hip flexor involvement. This makes the cable decline reverse crunch a superior option for sustained tension, progressive overload, and mobility development, particularly for athletes and individuals looking to improve core control and lower abdominal strength.

Forearm Curls (Wrist Flexors)

The dumbbell forearm curl is an essential exercise for targeting the wrist flexors and extensors, contributing to grip strength, forearm hypertrophy, and wrist mobility. Unlike compound pulling movements, which engage the forearms indirectly, forearm curls provide direct isolation of these muscles, ensuring consistent mechanical tension and progressive overload. To perform this variation, the lifter holds a dumbbell in each hand with the forearms resting on a flat surface such as a bench or their own thighs, allowing the wrists to extend downward into a stretched position, as seen in

Figure 34. The concentric phase consists of curling the wrists upward, squeezing the forearm flexors to lift the dumbbells, achieving peak contraction at the top. The eccentric phase is performed slowly and under control, returning to the fully stretched position, as seen in

Figure 35, to maximize time under tension in the lengthened muscle state. Because gravity dictates resistance, peak tension occurs in the mid-range, while resistance diminishes slightly at the top and bottom of the movement. This variation is particularly effective for building forearm mass and improving wrist mobility, though it lacks constant resistance across the full range of motion.

The cable forearm curl provides a more consistent resistance curve, ensuring continuous muscle activation throughout the movement. To set up, the lifter stands facing a cable machine with the pulley set at a low position, gripping a straight bar or individual handles with palms facing upward. By stepping slightly back, the lifter establishes an initial pre-stretch in the forearm flexors, as seen in

Figure 36, before beginning the movement. The concentric phase consists of curling the wrists upward, focusing on controlled movement to fully activate the forearm flexors. Unlike the dumbbell version, where resistance diminishes at the top, the cable maintains tension throughout the entire range, including the contracted position, as seen in

Figure 37. The eccentric phase is performed slowly, allowing the forearms to lengthen under tension, reinforcing strength at long muscle lengths. Additionally, subtle adjustments in cable angle and grip positioning allow for precision in targeting the forearm muscles, ensuring optimal hypertrophy and mobility adaptations. The cable forearm curl is particularly beneficial for improving wrist stability, making it a superior choice for athletes, lifters, and individuals seeking to enhance grip endurance while reinforcing joint control in wrist flexion movements.

Calf Raises (Triceps Surae Complex)

The dumbbell calf raise is a fundamental exercise for developing the gastrocnemius and soleus muscles, which contribute to ankle stability, lower leg hypertrophy, and functional movement efficiency. Because the calves are highly endurance-based muscles, training them with full-range movements and stretch-mediated resistance is essential for optimal growth. To perform this variation, the lifter stands on a raised platform with the balls of the feet positioned on the edge, allowing the heels to drop downward into a fully stretched position, as seen in

Figure 38. Holding a dumbbell in each hand, the concentric phase consists of pressing through the balls of the feet to lift the heels as high as possible, ensuring full contraction of the calf muscles. The eccentric phase is performed slowly and under control, lowering the heels back to the stretched position, as seen in

Figure 39, to maximize tension in the lengthened muscle state. Because gravity provides the highest resistance at the bottom of the movement, this variation is particularly effective for stretch-mediated hypertrophy. However, like other free-weight exercises, resistance diminishes at the top, making it less effective for maintaining consistent tension in the contracted position.

The cable calf raise provides a more mechanically efficient alternative, maintaining constant tension throughout the entire movement. To perform this variation, the lifter stands on a raised platform, gripping a cable handle attached to a low pulley for added resistance. The starting position, as seen in

Figure 40, ensures that the heels are fully lowered, placing the calves in a deeply stretched position under tension. The concentric phase involves pressing through the balls of the feet, elevating the heels while maintaining upright posture and control. Unlike the dumbbell version, where resistance drops at peak contraction, the cable system ensures continuous loading even at the top of the movement, as seen in

Figure 41, reinforcing hypertrophy and strength development across the full range of motion. The eccentric phase consists of slowly lowering the heels back to the stretched position, emphasizing progressive overload and mobility adaptations. Additionally, adjustments in cable angle and resistance positioning allow for precise targeting of the gastrocnemius and soleus, making the cable calf raise a superior option for maximizing hypertrophy, mobility, and ankle stability.

The Complexity of Training the Gluteal Muscles

The gluteal muscles, comprising the gluteus maximus, gluteus medius, and gluteus minimus, play pivotal roles in various hip movements, including extension, abduction, and internal and external rotation. Their extensive involvement in these fundamental movements means that the glutes are naturally engaged during numerous compound exercises, such as squats, deadlifts, and lunges, which are staples in most resistance training programs.

The gluteus maximus, being the largest muscle in the human body, plays a significant role in maintaining upright posture and propelling the body forward during locomotion. Its activation is inherent in many daily activities and standard lower-body exercises, making it challenging to isolate without overlapping with other muscle groups.

Given these factors, this paper does not include specific isolated exercises for the gluteal muscles. Instead, it acknowledges that well-structured compound movements within a balanced resistance training program sufficiently target the glutes, promoting both strength and hypertrophy.

Neutral-Stretched Muscles

Neutral-stretched muscles are those that naturally experience their stretch in a neutral or extended position, meaning they do not require external positioning beyond their anatomical resting state to achieve maximum elongation under tension. Unlike bidirectional muscles, which benefit from movement both forward and backward from a neutral position, neutral-stretched muscles are fully lengthened at rest and contract primarily through a single-plane movement pattern. This category includes the biceps and quadriceps, which both reach their natural stretch when fully extended at the elbow and knee, respectively.

Because these muscles are already in a stretched position at rest, training them effectively requires proper resistance alignment to ensure consistent mechanical tension throughout the range of motion. Exercises for these muscles should emphasize eccentric control and deep-stretch loading, ensuring that hypertrophic adaptations are maximized without excessive reliance on momentum or joint strain. Additionally, optimal resistance angles play a crucial role in maintaining tension at both stretched and contracted positions, reinforcing strength across the full range of motion.

The following sections will explore specific exercises for neutral-stretched muscles, detailing how to incorporate deep stretch principles and optimal resistance angles to maximize hypertrophy and mobility. By structuring exercises according to the biomechanics of these muscle groups, training programs can ensure efficient strength development and functional movement capacity.

Bicep Curls (Biceps Brachii)

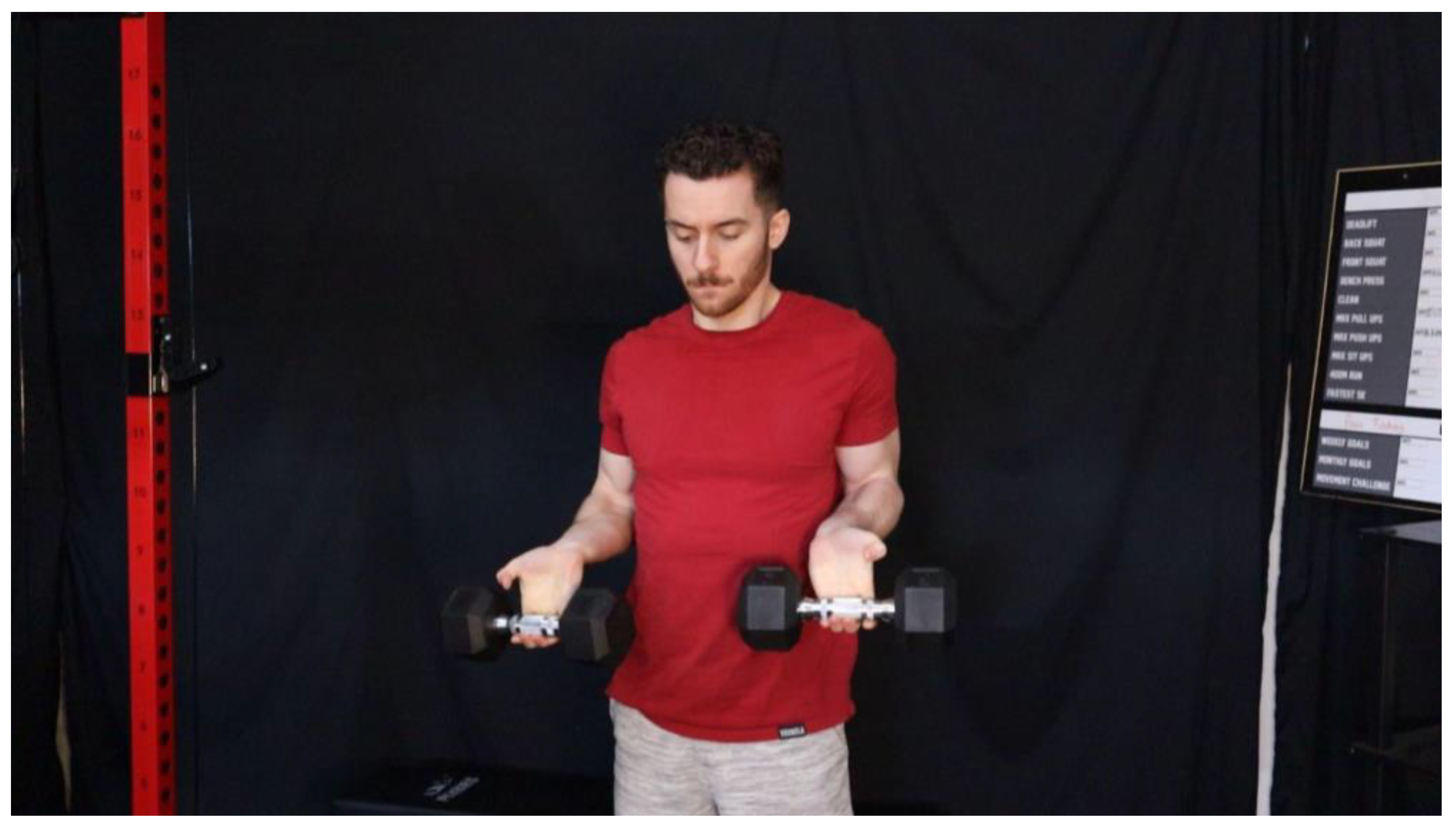

The dumbbell bicep curl is a fundamental exercise for biceps brachii development, leveraging a natural stretch at full elbow extension while promoting hypertrophy and mobility through a full range of motion. Unlike bidirectional muscles, which require external positioning for an enhanced stretch, the biceps naturally achieve maximum elongation when the arm is fully extended. To optimize tension throughout the movement, the lying dumbbell bicep curl is performed with the lifter lying flat on a bench, allowing the arms to extend toward the floor, as seen in

Figure 42. The concentric phase consists of curling the dumbbells toward the chest, ensuring that the elbows remain stationary and do not drift forward, which would reduce tension on the biceps. At the top of the movement, the biceps reach full contraction before the eccentric phase begins, where the arms are slowly lowered back to the fully stretched position, as seen in

Figure 43. Because gravity provides resistance primarily in the mid-range, the top and bottom portions of the movement experience reduced tension, making this variation particularly effective for stretch-mediated hypertrophy but less ideal for consistent resistance throughout the entire movement.

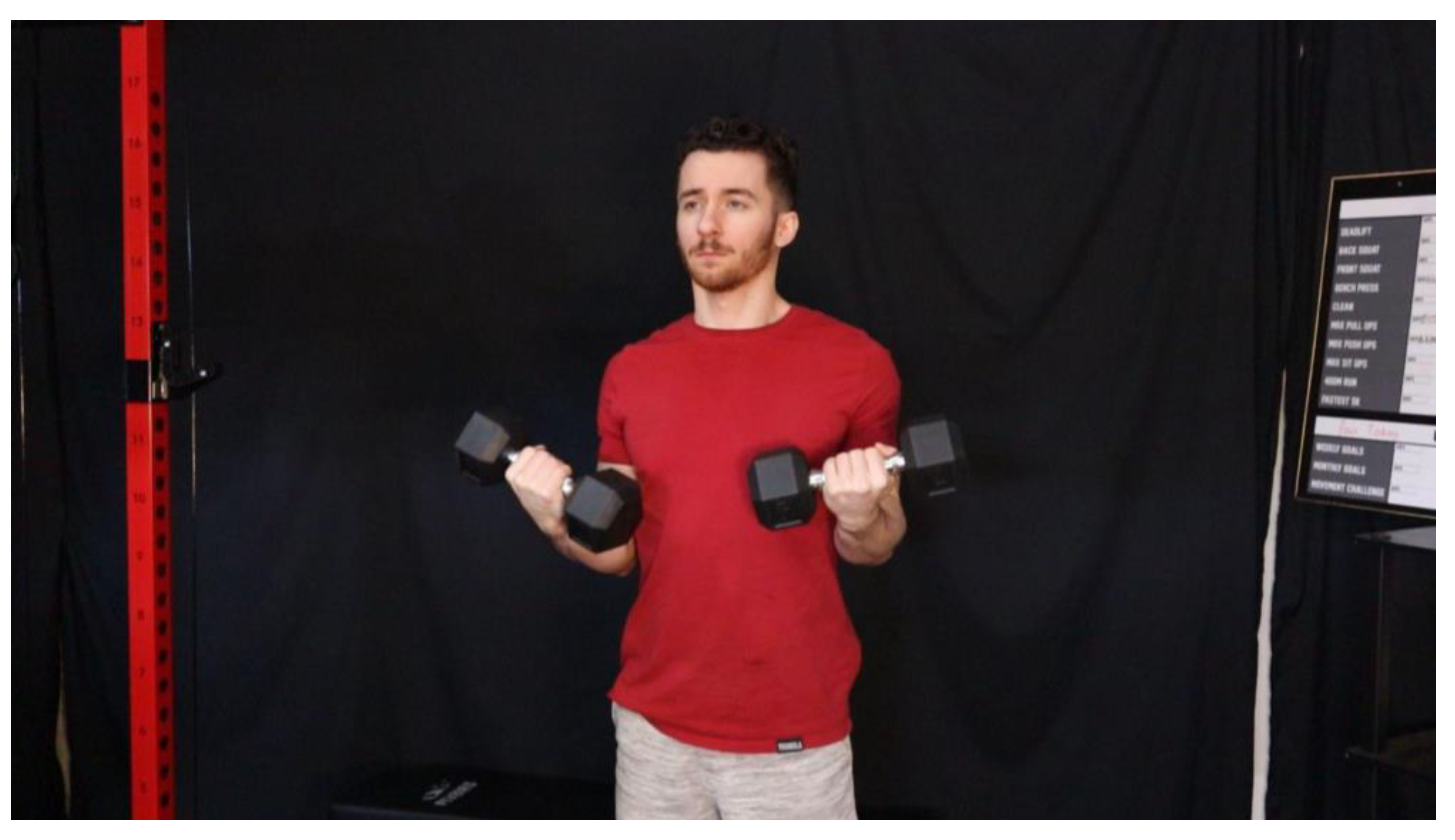

The cable bicep curl provides a more mechanically efficient alternative, ensuring that the biceps remain under constant tension throughout the movement. To perform this variation, the lifter stands between two cable machines, gripping the handles with the pulleys set at hand height. By stepping forward slightly, the lifter creates an initial pre-stretch in the biceps, as seen in

Figure 44, before beginning the movement. The concentric phase consists of curling the handles toward the chest, keeping the elbows locked in place to maximize biceps activation. Unlike free weights, where tension is lost at full contraction, the cable system maintains resistance in both the stretched and contracted positions, ensuring continuous muscle activation at every phase of the movement. The eccentric phase is performed slowly and under control, returning the arms to the fully extended position, as seen in

Figure 45, while resisting the pull of the cables. Additionally, adjustments in stance and cable height allow for precise resistance alignment, ensuring optimal recruitment of the biceps in both the lengthened and shortened positions. This makes the cable bicep curl a superior option for maximizing hypertrophy, reinforcing mobility, and improving elbow joint stability.

The Complexity of Training the Hamstrings

The hamstrings present unique challenges in resistance training due to their dual-function nature, as they act as both hip extensors and knee flexors. Unlike many other muscle groups that operate within a single-joint movement pattern, the hamstrings cross both the hip and knee joints, requiring multi-angle engagement to fully activate all portions of the muscle. This structural complexity makes it difficult to design exercises that effectively incorporate deep stretch principles and optimal resistance angles without excessive compensation from surrounding muscle groups.

Another factor complicating hamstring training is the biomechanical differences between its individual muscle heads. The biceps femoris (long head) is more involved in hip extension, working alongside the gluteus maximus, while the semimembranosus and semitendinosus play a larger role in knee flexion. Because these functions are often trained separately—hip extension through deadlifts and Romanian deadlifts, and knee flexion through leg curls—many training programs fail to optimize full-length tension across all muscle heads simultaneously. Additionally, traditional hamstring exercises often involve significant glute and lower back engagement, making it difficult to isolate the hamstrings without shifting tension away from the target muscles.

The length-tension relationship of the hamstrings further complicates their training. Since they are actively stretched at both the hip and knee, finding exercises that maximize deep stretch loading without inducing excessive strain on the lower back or knee joints requires precise body positioning and resistance alignment. Exercises that emphasize knee flexion under load, such as lying leg curls, tend to focus on the shortened range of motion, while hip extension-based movements, such as Romanian deadlifts, bias the lengthened position but may not fully engage the knee flexion function. This discrepancy makes it difficult to apply both stretch-mediated hypertrophy principles and optimal resistance angles within a single movement pattern.

Due to these challenges, hamstring exercises must be carefully selected and modified to ensure consistent tension throughout the range of motion while preventing excessive reliance on the glutes or lower back. The integration of cable-based movements or modified machine exercises can help create a more precise resistance curve, ensuring that the hamstrings experience both optimal stretch and full contraction without excessive compensation. In the following sections, potential solutions and movement modifications will be explored to address these biomechanical complexities, allowing for more effective hypertrophy and mobility adaptations in hamstring training.

Active-Stretched Muscles

Active-stretched muscles are those that require external positioning or specific movement adjustments to achieve a deep stretch under load. Unlike bidirectional muscles, which naturally stretch in one direction and contract in the other, or neutral-stretched muscles, which reach their stretch in an extended position, active-stretched muscles do not enter a fully lengthened state without deliberate positioning. This makes training them for hypertrophy and mobility more complex, as the stretch-mediated hypertrophy response depends on proper exercise selection and execution.

Muscles in this category include the hamstrings, triceps, and certain forearm muscles, all of which require strategic positioning to place them under deep mechanical tension at long muscle lengths. For example, the hamstrings must be lengthened through both hip flexion and knee extension, while the triceps require shoulder flexion to reach their most elongated state. Because these muscles do not experience a passive stretch in their resting position, exercises must be designed to ensure that the resistance curve aligns with their strongest mechanical points, optimizing both hypertrophy and mobility development.

In the following sections, specific exercises for active-stretched muscles will be explored, demonstrating how to apply deep stretch principles and optimal resistance angles to maximize both muscle growth and functional movement capacity. By carefully structuring these movements, training programs can more effectively target full-range strength adaptations, ensuring that active-stretched muscles develop both size and flexibility while reducing injury risks.

Triceps Extensions (Triceps Brachii)

The dumbbell overhead triceps extension is one of the most effective exercises for targeting the long head of the triceps, which is the only portion of the triceps that crosses the shoulder joint. Unlike other triceps exercises that emphasize mid-range contraction, the overhead variation places the triceps under deep stretch, maximizing stretch-mediated hypertrophy and mobility. To perform this exercise, the lifter sits or stands while holding a dumbbell with both hands, positioning it behind the head with elbows fully flexed, as seen in

Figure 46. The concentric phase consists of extending the elbows, pressing the dumbbell upward until the arms are fully straightened. At the top of the movement, the triceps are fully contracted before beginning the eccentric phase, where the dumbbell is slowly lowered back to the stretched position, as seen in

Figure 47. Because gravity provides peak resistance in the stretched phase, this variation is particularly effective for long-head triceps development. However, tension diminishes at full lockout, making it less effective for maintaining continuous resistance in the shortened position.

The cable overhead triceps extension offers a more consistent resistance curve, ensuring that tension remains constant throughout the movement. To perform this variation, the lifter faces away from a cable machine, gripping a rope or straight bar attachment with the pulley set at its lowest position. The starting position, as seen in

Figure 48, requires the lifter to step forward slightly, creating an initial pre-stretch in the triceps before beginning the movement. The concentric phase consists of extending the elbows, pressing the cable handle overhead while maintaining a controlled range of motion. Unlike the dumbbell version, where resistance is lost at full extension, the cable system ensures tension remains even at the top, as seen in

Figure 49, making it a superior option for hypertrophy and joint stability. The eccentric phase is performed slowly, allowing the triceps to fully lengthen under load, reinforcing strength at long muscle lengths. Additionally, adjustments in cable height and stance positioning allow for precise resistance alignment, ensuring optimal triceps activation while reducing excessive elbow strain. This makes the cable overhead triceps extension a highly effective choice for those looking to develop size, mobility, and joint stability in the long head of the triceps.

The Complexity of Training the Quadriceps

The quadriceps are one of the most powerful muscle groups in the body, primarily responsible for knee extension and playing a critical role in locomotion, stability, and force generation. Unlike many other muscle groups, the quadriceps are highly active in almost all lower-body movements, including squatting, lunging, jumping, and sprinting. This constant engagement makes isolating specific portions of the quadriceps challenging, as most compound lower-body exercises inherently train them without the need for specialized movements.

One of the main complexities in targeting the quadriceps optimally is their biarticular nature, particularly with the rectus femoris, which crosses both the hip and knee joints. While the vastus lateralis, vastus medialis, and vastus intermedius function exclusively as knee extensors, the rectus femoris plays a role in both hip flexion and knee extension, making its full activation dependent on proper hip positioning. This complexity means that placing the quads under deep stretch while maintaining optimal resistance angles is difficult, as most knee extension movements inherently shorten the rectus femoris at the hip, limiting stretch-mediated hypertrophy.

Additionally, traditional quad-focused exercises such as squats and leg presses provide consistent loading throughout the range of motion, reducing the need for dedicated isolation work beyond what is already included in a well-structured program. Unlike muscles such as the hamstrings or triceps, which require external positioning to achieve a fully lengthened state, the quadriceps naturally stretch under loaded knee flexion, making most common lower-body exercises sufficient for hypertrophy and mobility adaptations.

Given these biomechanical factors, this paper will not include specific quadriceps-focused exercises, as their deep stretch and optimal resistance angle principles are already applied in compound movements. Instead, training programs should focus on proper squat depth, controlled eccentric loading, and knee positioning to maximize quad development without excessive joint strain. Future research and program design may explore more advanced methods for isolating specific quadriceps heads, but for the purposes of this framework, compound lower-body movements remain the most effective approach.

The Necessity of Exercise Variety for Optimal Muscle Hypertrophy

While the exercises discussed in this paper provide targeted approaches to muscle growth, relying exclusively on a fixed set of movements can limit overall hypertrophy and functional strength development. Muscles adapt over time to repeated stimuli, which can lead to stagnation if training variables are not adjusted. This principle, often referred to as the need for variation in resistance training, suggests that incorporating a diverse range of exercises is essential for preventing plateaus and continuing progress (Kraemer et al., 2002). Without regular variation, the neuromuscular system becomes more efficient at performing the same movement patterns, resulting in reduced muscular stimulus and diminishing hypertrophic responses.

Another key factor in maximizing muscle growth is engaging different muscle fibers and movement angles. Research indicates that varying exercises, particularly those that modify joint angles, resistance curves, and muscle activation patterns, can lead to more comprehensive hypertrophy (Schoenfeld, 2016). For example, altering grip positions or stance widths during resistance exercises can shift the emphasis to different regions of a muscle, ensuring balanced development. This variation is particularly important for preventing muscular imbalances, which can increase the risk of injury and reduce overall strength performance (Fleck & Kraemer, 2014).

Exercise variety also enhances neuromuscular adaptation, improving the efficiency of muscle activation and coordination. Repeating the same movement patterns can lead to over-reliance on dominant muscle fibers while underutilizing others. By introducing different exercises and movement patterns, resistance training can enhance motor unit recruitment and neuromuscular efficiency, contributing to greater force production and improved athletic performance (Fleck & Kraemer, 2014). Additionally, progressive overload, which is essential for continued hypertrophy, is more effectively implemented when new stimuli are introduced. By incorporating novel exercises and movement variations, the muscles are subjected to unfamiliar stress, promoting continued adaptation and muscle fiber recruitment (Kraemer et al., 2002).

While deep stretch and optimal resistance angle exercises are highly effective, they should not be the sole focus of a hypertrophy-based program. A well-structured resistance training regimen should incorporate a balance of compound movements, isolation exercises, unilateral work, and multi-planar training to ensure comprehensive muscle development, joint stability, and functional strength. This multi-faceted approach prevents adaptation-related stagnation while ensuring that muscles are challenged from multiple angles and in different movement patterns. By continuously modifying exercise selection, individuals can optimize muscle hypertrophy while reducing the risk of overuse injuries and muscular imbalances.

Conclusions

Maximizing muscular hypertrophy and mobility requires a strategic approach that integrates deep stretch loading and optimal resistance angles into resistance training. Research has demonstrated that training muscles in their lengthened position under load leads to superior hypertrophy compared to traditional mid-range training, making deep stretch exercises a valuable tool for those looking to optimize muscle growth (Maeo et al., 2023; Warneke et al., 2023). Additionally, aligning resistance with a muscle’s strongest mechanical advantage, typically within the 45- to 135-degree range relative to the resistance source, ensures that tension remains consistent across the full range of motion, further enhancing both hypertrophy and joint function (Pedrosa et al., 2023).

While the exercises detailed in this paper are highly effective for targeting specific muscle groups using these principles, no single exercise or method should be relied upon exclusively. A well-rounded hypertrophy program must incorporate varied exercises, movement patterns, and progressive overload strategies to prevent adaptation and training plateaus (Kraemer et al., 2002; Schoenfeld, 2016). Additionally, understanding the complexity of certain muscle groups, such as the hamstrings and quadriceps, highlights the need for thoughtful exercise selection and resistance application to ensure full-length tension while minimizing compensation patterns and injury risks.

By applying these principles, individuals can develop stronger, more resilient muscles while enhancing mobility and joint health. Resistance training should not be viewed solely as a means of increasing muscle size but as a tool for improving functional strength, movement efficiency, and longevity. Future research and practical application should continue to explore the relationship between deep stretch, resistance angles, and long-term musculoskeletal health, refining training methodologies for optimal results in both hypertrophy and movement capacity.

References

- Behm, D. G., Alizadeh, S., Trajano, G. S., & Button, D. C. (2021). Continuous versus intermittent stretch training on range of motion: A systematic review with meta-analysis. Frontiers in Physiology, 12, 654425. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphys.2021.654425. [CrossRef]

- Kubo, K., Ikebukuro, T., Yata, H., Tomita, M., & Okada, M. (2021). Effects of static and dynamic stretching programs on the viscoelastic properties of human tendon structures in vivo. Journal of Applied Physiology, 130(2), 383-392. https://doi.org/10.1152/japplphysiol.00772.2020. [CrossRef]

- Maeo, S., Otsuka, S., Murakami, T., Kobayashi, D., & Kudoh, C. (2023). Effect of training with lengthened partial repetitions on muscle size and strength. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise, 55(2), 278-286. https://doi.org/10.1249/MSS.0000000000003018. [CrossRef]

- Schoenfeld, B. J. (2010). The mechanisms of muscle hypertrophy and their application to resistance training. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 24(10), 2857-2872. https://doi.org/10.1519/JSC.0b013e3181e840f3. [CrossRef]

- Warneke, K., Lohmann, L. H., Lima, C. D., Hollander, K., Konrad, A., Zech, A., Nakamura, M., Wirth, K., Keiner, M., & Behm, D. G. (2023). Physiology of stretch-mediated hypertrophy and strength increases: A narrative review. Sports Medicine, 53(11), 2055-2075. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40279-023-01898-x. [CrossRef]

- McMahon, G. E., Morse, C. I., Burden, A., Winwood, K., & Onambélé, G. L. (2014). Impact of range of motion during ecologically valid resistance training protocols on muscle size, subcutaneous fat, and strength. European Journal of Applied Physiology, 114(4), 822-833. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00421-014-2814-3. [CrossRef]

- Kassiano, W., Santos, W., Schoenfeld, B. J., & Willardson, J. M. (2023). Resistance training at long muscle lengths: An evidence-based approach for inducing muscle hypertrophy. Sports Medicine, 53(3), 469-486. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40279-023-01879-0. [CrossRef]

- Pedrosa, J., Rocha, L., Almeida, L., & Pinto, R. (2023). Muscle hypertrophy and strength adaptations to training at long vs. short muscle lengths: A systematic review and meta-analysis. European Journal of Sport Science, 23(4), 687-699. https://doi.org/10.1080/17461391.2023.2163507. [CrossRef]

- Schoenfeld, B. J., Ogborn, D., & Krieger, J. W. (2017). Dose-response relationship between weekly resistance training volume and increases in muscle mass: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Sports Sciences, 35(11), 1073-1082. https://doi.org/10.1080/02640414.2016.1210197. [CrossRef]

- Wackerhage, H., Schoenfeld, B. J., Hamilton, D. L., Lehti, M., & Hulmi, J. J. (2019). Stimuli and sensors that initiate skeletal muscle hypertrophy following resistance exercise. Journal of Applied Physiology, 126(1), 30-43. https://doi.org/10.1152/japplphysiol.00685.2018. [CrossRef]

- McMahon, G. E., Morse, C. I., Burden, A., Winwood, K., & Onambélé, G. L. (2014). Impact of range of motion during ecologically valid resistance training protocols on muscle size, subcutaneous fat, and strength. European Journal of Applied Physiology, 114(4), 822-833. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00421-014-2814-3. [CrossRef]

- Kassiano, W., Santos, W., Schoenfeld, B. J., & Willardson, J. M. (2023). Resistance training at long muscle lengths: An evidence-based approach for inducing muscle hypertrophy. Sports Medicine, 53(3), 469-486. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40279-023-01879-0. [CrossRef]

- Pedrosa, J., Rocha, L., Almeida, L., & Pinto, R. (2023). Muscle hypertrophy and strength adaptations to training at long vs. short muscle lengths: A systematic review and meta-analysis. European Journal of Sport Science, 23(4), 687-699. https://doi.org/10.1080/17461391.2023.2163507. [CrossRef]

- Kassiano, W., Santos, W., Schoenfeld, B. J., & Willardson, J. M. (2023). Resistance training at long muscle lengths: An evidence-based approach for inducing muscle hypertrophy. Sports Medicine, 53(3), 469-486. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40279-023-01879-0. [CrossRef]

- Pedrosa, J., Rocha, L., Almeida, L., & Pinto, R. (2023). Muscle hypertrophy and strength adaptations to training at long vs. short muscle lengths: A systematic review and meta-analysis. European Journal of Sport Science, 23(4), 687-699. https://doi.org/10.1080/17461391.2023.2163507. [CrossRef]

- Fleck, S. J., & Kraemer, W. J. (2014). Designing resistance training programs (4th ed.). Human Kinetics.

- Kraemer, W. J., Adams, K., Cafarelli, E., Dudley, G. A., Dooly, C., Feigenbaum, M. S., ... & Triplett-McBride, T. (2002). American College of Sports Medicine position stand. Progression models in resistance training for healthy adults. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise, 34(2), 364-380.

- Schoenfeld, B. J. (2016). Science and development of muscle hypertrophy. Human Kinetics.

Figure 1.

Optimal resistance angles pertaining to free weight exercises and cable exercise. Note. The figure on the left demonstrates the optimal resistance for free weight exercises. The figure on the right demonstrates the optimal resistance for cable exercises.

Figure 1.

Optimal resistance angles pertaining to free weight exercises and cable exercise. Note. The figure on the left demonstrates the optimal resistance for free weight exercises. The figure on the right demonstrates the optimal resistance for cable exercises.

Figure 2.

Position 1 of the dumbbell chest fly.

Figure 2.

Position 1 of the dumbbell chest fly.

Figure 3.

Position 2 of the dumbbell chest fly.

Figure 3.

Position 2 of the dumbbell chest fly.

Figure 4.

Position 1 of the cable chest fly.

Figure 4.

Position 1 of the cable chest fly.

Figure 5.

Position 2 of the cable chest fly.

Figure 5.

Position 2 of the cable chest fly.

Figure 6.

Position 1 of the dumbbell lying front raise.

Figure 6.

Position 1 of the dumbbell lying front raise.

Figure 7.

Position 2 of the dumbbell lying front raise.

Figure 7.

Position 2 of the dumbbell lying front raise.

Figure 8.

Position 1 of the cable front raise.

Figure 8.

Position 1 of the cable front raise.

Figure 9.

Position 2 of the cable front raises.

Figure 9.

Position 2 of the cable front raises.

Figure 10.

Position 1 of the dumbbell lying lateral raises.

Figure 10.

Position 1 of the dumbbell lying lateral raises.

Figure 11.

Position 2 of the dumbbell lying lateral raises.

Figure 11.

Position 2 of the dumbbell lying lateral raises.

Figure 12.

Position 1 of the cable lateral raises.

Figure 12.

Position 1 of the cable lateral raises.

Figure 13.

Position 2 of the cable lateral raises.

Figure 13.

Position 2 of the cable lateral raises.

Figure 14.

Position 1 of the dumbbell lying rear delt fly.

Figure 14.

Position 1 of the dumbbell lying rear delt fly.

Figure 15.

Position 2 of the dumbbell lying rear delt fly.

Figure 15.

Position 2 of the dumbbell lying rear delt fly.

Figure 16.