Submitted:

16 June 2025

Posted:

17 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

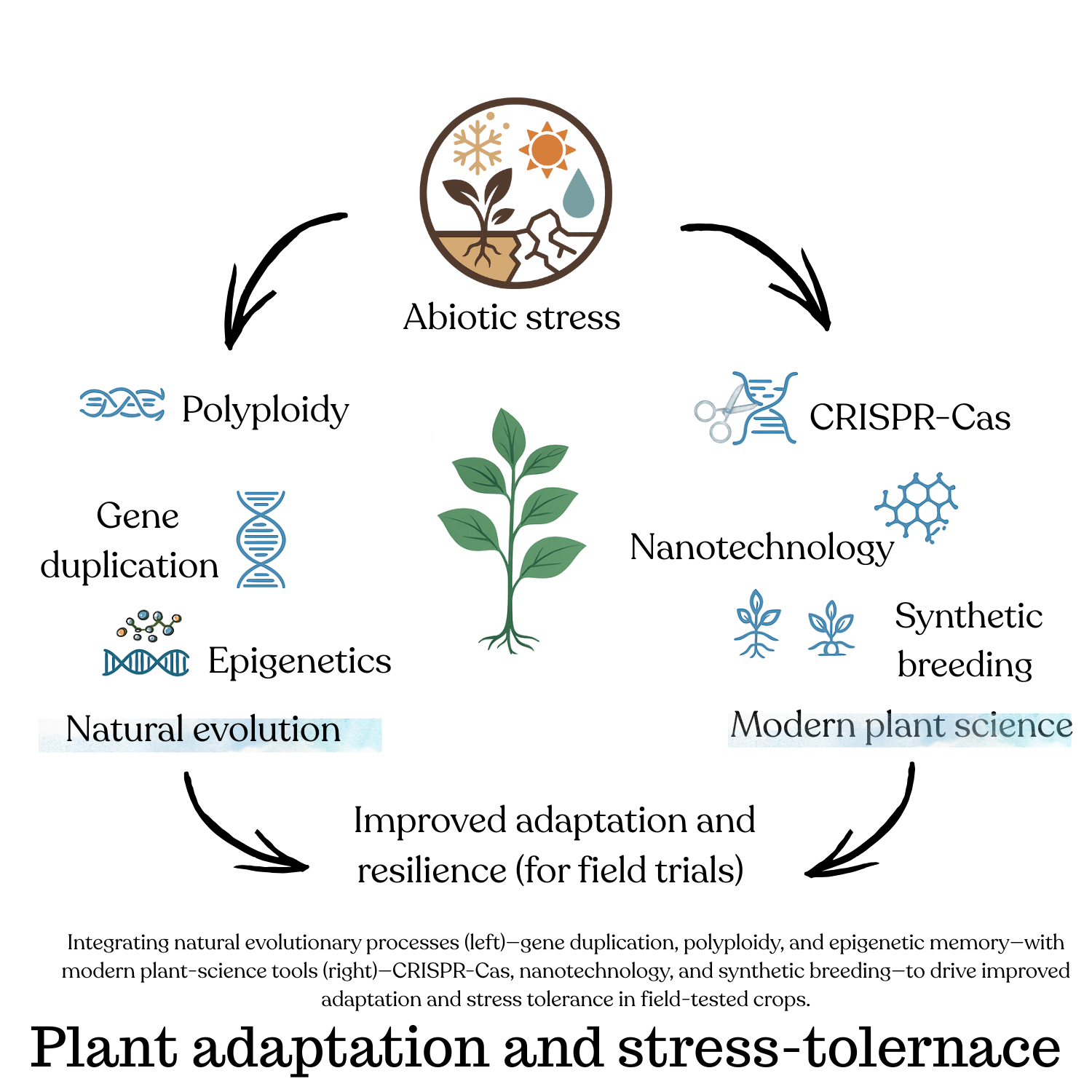

1. Introduction

2. Evolutionary Mechanism for Plant Adaptation

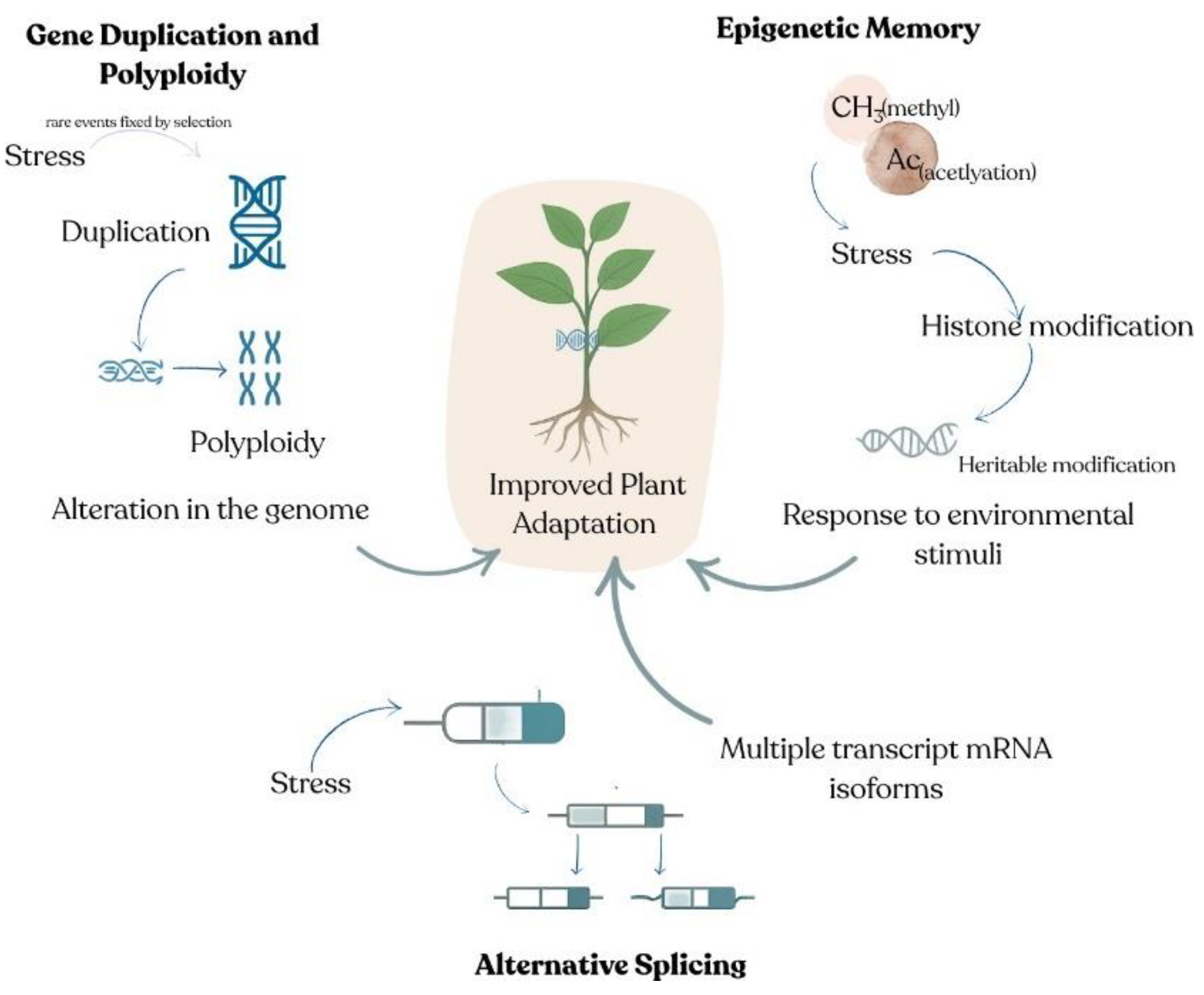

2.1. Gene Duplication and Polyploidy

-

Pros:

- Extra gene copies provide protection against mutations and maintain required functions.

- Polyploidy-derived homologues enhance the stress-coping mechanisms and improve metabolic balance.

-

Cons:

- Entire genome duplications are difficult to induce precisely.

- Polyploid breeding systems require complex crossovers and linkage drags.

-

Unknown:

- How do gene duplicates and homeolog expressions perform under field environmental challenges and their stability in those varied circumstances?

2.2. Epigenetic Memory

-

Pros

- Stress-induced epigenetic memory is passed on to the next generation and provides transgenerational priming.

- Modifications are reversible, meaning once the stress subsides, plants can reset.

-

Cons

- Methylation due to stress memory markers can revert unpredictably, reducing stability in the long run.

- Current tools lack accuracy and cannot target the epialleles in plants.

-

Unknown

- How long can the epigenetic stress memory markers last across generations and be stable under an uncontrolled field environment?

2.3. Alternative Splicing

| Pros | ||

| • | Stress-induced epigenetic memory is passed on to the next generation and provides | |

| transgenerational priming. | ||

| • | Modifications are reversible, meaning once the stress subsides, plants can reset. | |

| Cons | ||

| • | Methylation due to stress memory markers can revert unpredictably, reducing stability in the long run. | |

| • | Current tools lack accuracy and cannot target the epialleles in plants. | |

| Unknown | ||

| • | How long can the epigenetic stress memory markers last across generations and be stable under an uncontrolled field environment? | |

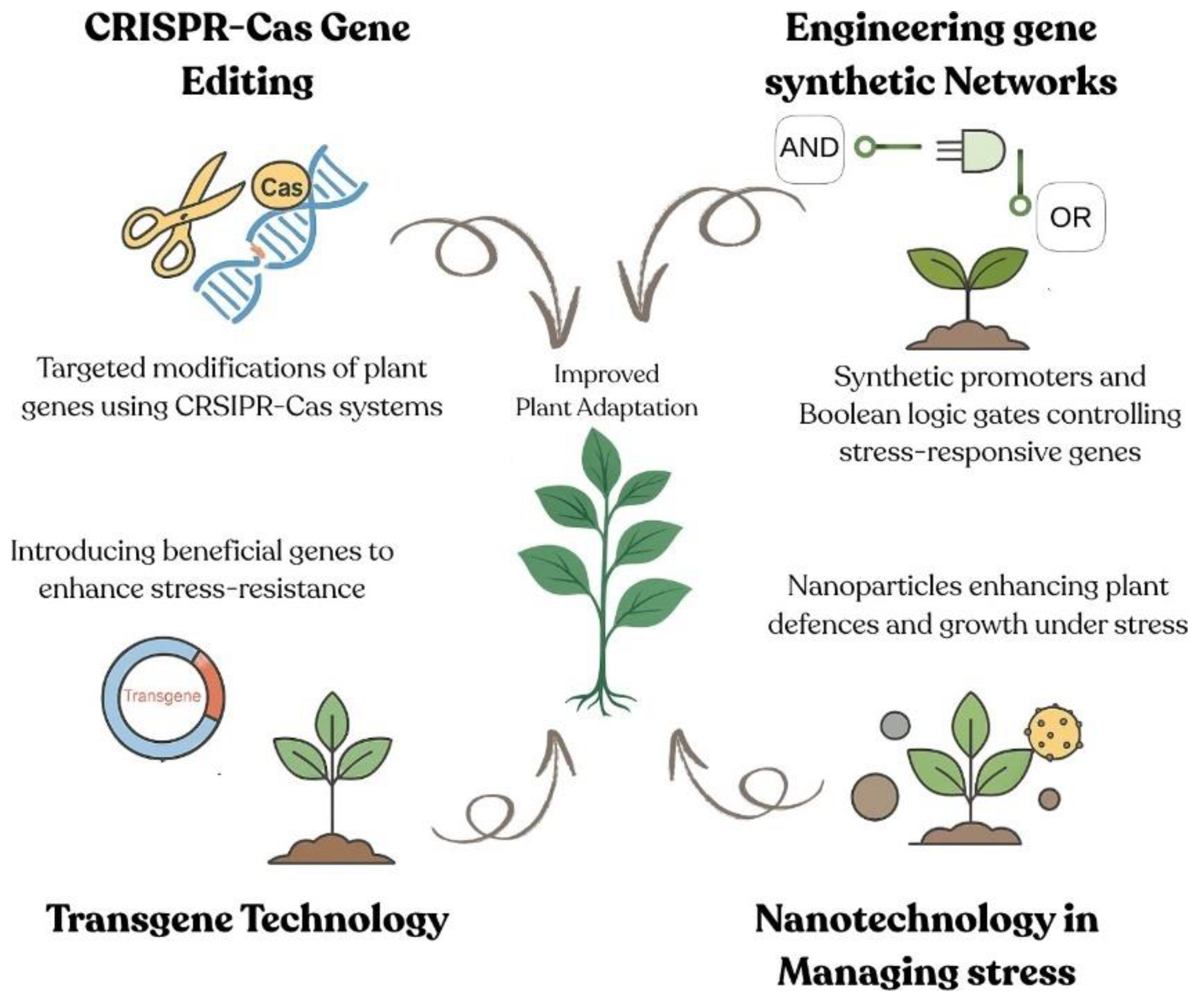

3. Engineering Strategies for Stress Tolerance in Plants

3.1. CRISPR-Cas Gene Editing

| Pros | ||

| • | Base and prime editors modify single nucleotides with minimal double-strand breaks | |

| and reduce genomic instability. | ||

| • | Transient delivery methods (e.g.,Cas9 RNPs or viral vectors) avoid stable incorporation | |

| of foreign DNA. | ||

| Cons | ||

| • | At low frequencies, screening of off-target mutations is required. | |

| • | Efficient delivery of edits into monocots like wheat and maize is challenging. | |

| Unknown | ||

| • | How do targeted gene edits affect the regulatory mechanism under abiotic stress? | |

3.2. Engineering Gene Networks

| Pros | ||

| • | Boolean logic gates enable the expression of stress-tolerant genes under specific envi- | |

| ronmental signals. | ||

| • | Modular circuits help in the rapid swapping of sensors and outputs. | |

| Cons | ||

| • | Under non-stress conditions, synthetic circuits might slow the growth due to metabolic load. | |

| • | The data on synthetic circuit function in polyploid crop genomics is limited. | |

| Unknown | ||

| • | How do these circuits function in large-scale field plots under fluctuating environmental stress signals? | |

3.3. Transgene Technology

| Pros | ||

| • | Under laboratory and greenhouse conditions, transgenes provide a high level of | |

| expression of specific resilience genes. | ||

| • | With well-characterized promoters, the trait stability expressions are possible. | |

| Cons | 150 | |

| • | Approvals from regulatory boards and the public vary depending on regions. | |

| • | Over generations, transgenic silencing occurs and leads to reduced trait stability. | |

| Unknown | ||

| • | How do introduced transgenes and native genes interact with each other under stress conditions in field settings? | |

3.4. Nanotechnology in Managing Stress

-

Pros

- Nanoparticles deliver nutrients or signalling molecules directly into plant cells with ease and hence enhance the functions of specific targeted activity.

- Engineered design allows the controlled release of particles under specific abiotic stress conditions.

-

Cons

- The specific size and dose of nanoparticles suitable for soil types and crops are yet to be identified.

- Toxicity to nontarget organisms and soil microbes is the biggest concern.

-

Unknown

- What happens to nanoparticles over time in an agricultural ecosystem, and how do they interact with nutrient cycles and microbes or other organisms and their potential effects on them? This is an example of a quote.

4. Integration of Evolutionary Mechanism and Engineered Strategies

5. Gaps in Current Research

5.1. Limited Field Validations

5.2. Limited Understanding of Isoform-Specific Functions

5.3. Underutilisation of Wild Relatives

5.4. Ineffective Interaction Across Disciplines

5.5. Regulatory Acceptances

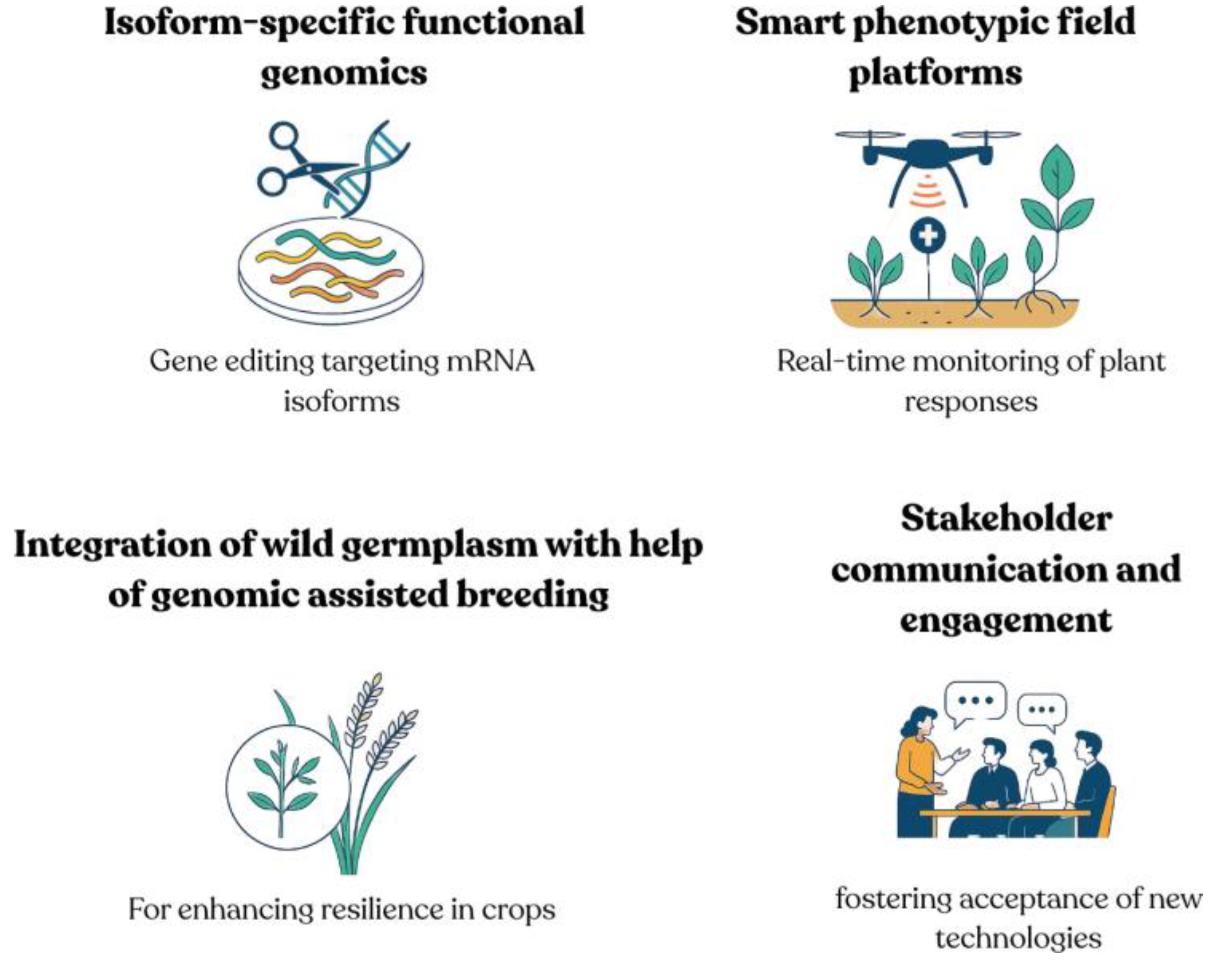

6. Future of Resilient Crop Design

6.1. Isoform-Specific Functional Genomics

- Most gene editing strategies include knockout or overexpression of target genes. However, with assistance from alternative splicing, multiple mRNA isoforms can be produced from a single gene, which can serve as an adaptive mechanism under stress [7]. These isoforms can have different functions and be used to design crops with improved efficacy instead of whole-genome modification; this approach minimises off- target modifications and enhances stress adaptation while preserving native regulation. For example, in rice, OsDREB2B gene isoforms can confer heat tolerance independent of the DREB pathway [8].– Further field trials needed to be conducted on rice and wheat under controlled drought conditions to identify specific tissue expressions and the resilience correlation of stress-responsive isoforms, such as DREB2B or SR proteins.

- Future work: which stress-responsive isoforms can yield stability under abiotic stresses needs to be studied in field conditions to understand their survival rates over two or more seasons.

6.2. Integration of Wild Germplasm with the Help of Genomic-Assisted Breeding

-

Wild relatives of any plant varieties have a vast range of gene pools, which have been developed over the years with the help of natural selection under express environ- mental conditions. Their integration into modern-day commercial or non-commercial crops can enhance resilience with the desired speed and specificity needed for improv- ing crop traits. These integrations can be achieved by the following methods:

- -

- AI haplotype mapping uses a diverse variety of genome library data to mine specific stress-resilient alleles. For example, use of AI-augmented haplotype map- ping to identify superior drought-responsive haplotypes in > 1000 rice accessions to increase yield in water-deficit field trial conditions with > 80 percent predictive accuracy [22].

- -

- With rapid-generation advancement (speed breeding) along with genomic selection (GS) allele stacking, genes can be transferred from one species to another and improve their allele efficiency. For example, use of both speed breeding and GS cycles for early detection of drought-tolerant alleles via GS panels in wheat [10].

- -

- Through CRISPR-Cas, we can edit gene lines to recreate important or beneficial wild alleles by bypassing linkage completely instead of just crossing. For example, with base editors of CRISPR-Cas9 we can reconstruct beneficial domesticated alleles via precise nucleotide substitutions, minimising double-strand breaks and linkage drag, while preserving stress-resistant wild traits [15].

- -

- For example, in wild barley, genes of salt tolerance can be mapped and edited into modern varieties without traditional breeding approaches and improve their salinity [26].

- Future work: the targeted editing of transcripts such as m6A needed further understanding of how to accelerate the recovery from abiotic stresses.

6.3. Development of Smart Phenotypic Field Platforms

-

Real-world applications are more complex and fluctuating compared to laboratory conditions. To address this issue, the implementation of smart field testing is required, with the combinational use of nanotechnology, sensors, and artificial intelligence (AI) not just for labs but for regional institutions globally, which can transform field trials into more adaptive and effective centres for testing:

- -

- In-plant and soil nanosensors can enable continuous real-time tracking of ROS, ABA, ion fluxes, etc. For example, carbon-dot-embedded graphene nanosheets de- tect ROS fluctuation [5]; dual-functional sensors based on charged gold nanorods (AuNRs) are used to detect ABA levels [28]; and the use of electrochemical nanosensors along with metal-decorated carbon nanotube electrodes detects real-time soil nitrate (NO3-) fluxes limited to parts per billion (ppb) range [12].

- -

- Drone imaging and AI models can detect stress signatures with the help of canopy temperatures and spectral shifts. For example, thermal imaging of stom- atal closure in wheat fields [4]; the combination of thermal, multispectral, and hyperspectral sensors and drones with VNIR can detect the temperature shifts with <1 m resolution, and AI helps in predicting the water stress with 85 percent accuracy and vegetation index abnormalities [21].

- -

- We can equip plants with engineered environmental sensing synthetic switches combined with sensors and regulators to respond to any external signals (e.g., controlled stress-oscillation circuits to detect ROS and ABA levels [11]).

- Future work: how the delivery system of stress-protective genes with tissue-specific promoters can help in improving resilience without any permanent transformative changes.

6.4. Stakeholder Communication and Engagement

- Any research is never autonomous of its intended target group. A transparent com- munication is needed between all farmers, policymakers, regulators, and the public in understanding the benefits and risks of bringing technologies together for crop improvement. Collaborative networks needed to be established with experts from genomics, data science, agronomy, and social sciences, to develop integrated, innovative and regulatory frameworks for increased acceptance towards crop varieties.

7. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bailey-Serres, J.; Parker, J.E.; Ainsworth, E.A.; Oldroyd, G.E.D.; Schroeder, J.I. Genetic Strategies for Improving Crop Yields. Nature 2019, 575, 109–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belcher, M.S.; Vuu, K.M.; Zhou, A.; Mansoori, N.; Agosto Ramos, A.; Thompson, M.G.; Scheller, H.V.; Loqué, D.; Shih, P.M. Design of Orthogonal Regulatory Systems for Modulating Gene Expression in Plants. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2020, 16, 857–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brophy, J.A.N.; Magallon, K.J.; Duan, L.; Zhong, V.; Ramachandran, P.; Kniazev, K.; Dinneny, J.R. Synthetic Genetic Circuits as a Means of Reprogramming Plant Roots. Science 2022, 377, 747–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, J.M.; Grant, O.M.; Chaves, M.M. Thermography to Explore Plant–Environment Interactions. J. Exp. Bot. 2013, 64, 3937–3949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Demirer, G.S.; Zhang, H.; Matos, J.L.; Goh, N.S.; Cunningham, F.J.; Sung, Y.; Chang, R.; Aditham, A.J.; Chio, L.; Cho, M.J.; Staskawicz, B.; Landry, M.P. High Aspect Ratio Nanomaterials Enable Delivery of Functional Genetic Material without DNAIntegration in Mature Plants. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2019, 14, 456–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El-Saadony, M.T.; Saad, A.M.; Soliman, S.M.; Salem, H.M.; Desoky, E.M.; Babalghith, A.O.; El-Tahan, A.M.; Ibrahim, O.M.; Ebrahim, A.A.M.; Abd El-Mageed, T.A.; Elrys, A.S.; Elbadawi, A.A.; El-Tarabily, K.A.; AbuQamar, S.F. Role of Nanoparticles inEnhancing Crop Tolerance to Abiotic Stress: A Comprehensive Review. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 946717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filichkin, S.; Priest, H.D.; Megraw, M.; Mockler, T.C. Alternative Splicing in Plants: Directing Traffic at the Crossroads ofAdaptation and Environmental Stress. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2015, 24, 125–135. [Google Scholar]

- Ganie, S.A.; Reddy, A.S.N. Stress-Induced Changes in Alternative Splicing Landscape in Rice: Functional Significance of SpliceIsoforms in Stress Tolerance. Biology 2021, 10, 309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallusci, P.; Dai, Z.; Génard, M.; Gauffretau, A.; Leblanc-Fournier, N.; Richard-Molard, C.; Vile, D.; Brunel-Muguet, S. Epigenetics for Plant Improvement: Current Knowledge and Modeling Avenues. Trends Plant Sci. 2017, 22, 610–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jighly, A.; Lin, Z.; Pembleton, L.W.; Cogan, N.O.I.; Spangenberg, G.C.; Hayes, B.J.; Daetwyler, H.D. Boosting Genetic Gain inAllogamous Crops via Speed Breeding and Genomic Selection. Front. Plant Sci. 2019, 10, 1364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.; Lister, R. Synthetic Gene Circuits in Plants: Recent Advances and Challenges. Quant. Plant Biol. 2025, 6, e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kundu, M.; Krishnan, P.; Chobhe, K.A.; Manjaiah, K.M.; Pant, R.P.; Chawla, G. Fabrication of Electrochemical Nanosensor forDetection of Nitrate Content in Soil Extract. Journal of Soil Science and Plant Nutrition 2022, 22, 2777–2792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lassoued, R.; Macall, D.; Smyth, S.; Phillips, P.; Hesseln, H. Risk and Safety Considerations of Genome Edited Crops: ExpertOpinion. Curr. Res. Biotechnol. 2019, 1, 100011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Yang, D.L.; Huang, H.; Zhang, G.; He, L.; Pang, J.; Lozano-Durán, R.; Lang, Z.; Zhu, J.K. Epigenetic Memory MarksDetermine Epiallele Stability at Loci Targeted by De Novo DNA Methylation. Nat. Plants 2020, 6, 661–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Yang, X.; Yu, Y.; Si, X.; Zhai, X.; Zhang, H.; Dong, W.; Gao, C.; Xu, C. Domestication of Wild Tomato Is Accelerated byGenome Editing. Nat. Biotechnol. 2018, 36, 890–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.; Zhang, L.; Wei, X.; Datta, T.; Wei, F.; Xie, Z. Polyploidization: A Biological Force That Enhances Stress Resistance. Int. J.Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 1957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Q.; Zong, Y.; Xue, C.; Wang, S.; Jin, S.; Zhu, Z.; Wang, Y.; Anzalone, A.V.; Raguram, A.; Doman, J.L.; Liu, D.R.; Gao, C. PrimeGenome Editing in Rice and Wheat. Nat. Biotechnol. 2020, 38, 582–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.J.; Fu, J.D.; Tang, Y.M.; Yu, T.F.; Yin, Z.G.; Chen, J.; Zhou, Y.B.; Chen, M.; Xu, Z.S.; Ma, Y.Z. GmNFYA13 Improves Salt and Drought Tolerance in Transgenic Soybean Plants. Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 11, 587244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Panchy, N.; Lehti-Shiu, M.; Shiu, S.H. Evolution of Gene Duplication in Plants. Plant Physiol. 2016, 171, 2294–2316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Leal, D.; Lemmon, Z.H.; Man, J.; Bartlett, M.E.; Lippman, Z.B. Engineering Quantitative Trait Variation for CropImprovement by Genome Editing. Cell 2017, 171, 470–480.e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, H.; Sidhu, H.; Bhowmik, A. Remote Sensing Using Unmanned Aerial Vehicles for Water Stress Detection: A ReviewFocusing on Specialty Crops. Drones 2025, 9, 241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ]ref-journal Singh, P.; Sundaram, K.T.; Vinukonda, V.P.; Venkateshwarlu, C.; Paul, P.J.; Pahi, B.; Gurjar, A.; Singh, U.M.; Kalia,S. ; Kumar, A.; Singh, V.K.; Sinha, P. Superior Haplotypes of Key Drought-Responsive Genes Reveal Opportunities for theDevelopment of Climate-Resilient Rice Varieties. Commun. Biol. 2024, 7, 89. [Google Scholar]

- Soleymani, S.; Piri, S.; Aazami, M.A.; Salehi, B. Cerium Oxide Nanoparticles Alleviate Drought Stress in Apple Seedlings byRegulating Ion Homeostasis, Antioxidant Defense, Gene Expression, and Phytohormone Balance. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 11805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thiebaut, F.; Hemerly, A.S.; Ferreira, P.C.G. A Role for Epigenetic Regulation in the Adaptation and Stress Responses ofNon-Model Plants. Front. Plant Sci. 2019, 10, 246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usman, B.; Nawaz, G.; Zhao, N.; Liao, S.; Liu, Y.; Li, R. Precise Editing of the OsPYL9 Gene by RNA-Guided Cas9 NucleaseConfers Enhanced Drought Tolerance and Grain Yield in Rice (Oryza sativa L.) by Regulating Circadian Rhythm and AbioticStress Responsive Proteins. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 7854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varshney, R.K.; Singh, V.K.; Kumar, A.; Powell, W.; Sorrells, M.E. Can Genomics Deliver Climate-Change Ready Crops? Curr.Opin. Plant Biol. 2018, 45, 205–211. [Google Scholar]

- Zafar, S.A.; Zaidi, S.S.; Gaba, Y.; Singla-Pareek, S.L.; Dhankher, O.P.; Li, X.; Mansoor, S.; Pareek, A. Engineering Abiotic StressTolerance via CRISPR/Cas-Mediated Genome Editing. J. Exp. Bot. 2020, 71, 470–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Li, W.; Zhang, H.; Wang, S.; Li, X.; Naqvi, S.M.Z.A.; Hu, J. Dual-Functional SERRS and Fluorescent Aptamer Sensor for Abscisic Acid Detection via Charged Gold Nanorods. Front. Chem. 2022, 10, 965761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).