Submitted:

16 June 2025

Posted:

17 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Traditional Cytogenetics Meets Bioinformatics/ Genomics

Classical Cytogenetics

Advanced Cytogenomics in Specific Diseases Like Brain and Cancer

Databases and Tools for the Visualization and Analysis of Cytogenomics Dataset

Chromosomal Aberration and Karyotyping Databases

Copy Number Variation (CNV) & Structural Variant Databases

Cytogenomic Mutation and Specific Disease Databases

Popular Variant Calling Tools

GATK (Genome Analysis Toolkit)

DeepVariant

Samtools

Genome Browsers and Popular Visualization Tools

| Tool | Applications | Limitations |

|---|---|---|

| UCSC Genome Browser | Comparative genomics and GWAS | Limited support for private datasets |

| Ensemble genome browser | Functional genomics and variant annotation and prioritization | Computationally expensive, some features also require scripting |

| NCBI Genome Data Viewer | Clinical cytogenetics, Human reference genome analysis and gene expression studies | Limited visualization compared to UCSC and Ensembl |

| CytoScape | Chromosomal interaction studies and structural variation visualization | More suited for network analysis than full genome visualization |

| IGV | SV, CNV and chromosomal aberration visualization | High memory usage, not ideal for comparative genomics |

| Circos | Cancer genomics and chromosome mapping | Limited automation(no inbuilt GUI) and less interactivity |

| ChromoPainter | Population genetics and evolutionary studies | Requires preprocessed data and parameter tuning is challenging |

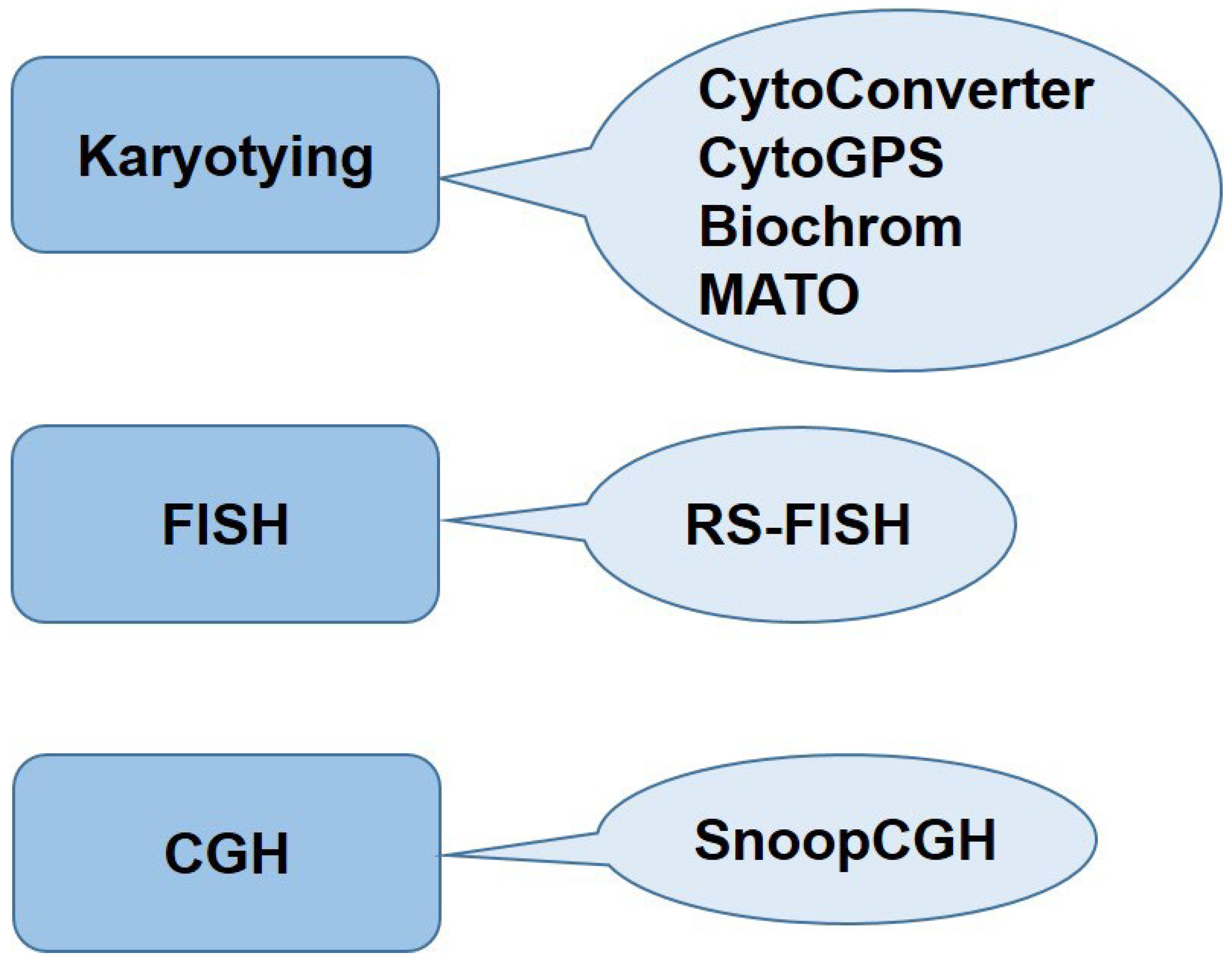

Cytogenomics Data Analysis Tools

| Tool | Language/ Implementation |

Features | Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| MATO/KaryoType | VB .NET framework Windows and MAC as well as Github source code |

Karyotype characterization and chromosome measurement | Plant and animal cytogenetics for measuring chromosome lengths, ideogram construction, evolutionary studies. |

| CytoConverter | Web based and R-package | Karyotype conversion into genomic coordinates, reporting net gain and loss of genetic material | Clinical genetics, Cancer research and Precise mapping of chromosomal aberrations |

| CytoGPS | Grammar Parser with Antlr. Web based, RCytoGPS (R version) |

Parses ISCN-based karyotype into machine readable text | Detection of complex structural variations, Personalized medication |

| Biochrom | Javascript, Web based, Image Processing and Deep Learning |

Downstream chromosome segmentation and classification | Prenatal diagnostics, automated detection of chromosomal abnormalities in fetal screening, rare genetic syndromes, and tumor cytogenetics. |

CytoConverter

CytoGPS

Biochrom

MATO

RS-FISH

SnoopCGH

Conclusions

References

- Akkari, Y.M.N.; Baughn, L.B.; Dubuc, A.M.; Smith, A.C.; Mallo, M.; Dal Cin, P.; Diez Campelo, M.; Gallego, M.S.; Granada Font, I.; Haase, D.T.; et al. Guiding the global evolution of cytogenetic testing for hematologic malignancies. Blood 2022, 139, 2273–2284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ribeiro, I.P.; Melo, J.B.; Carreira, I.M. Cytogenetics and Cytogenomics Evaluation in Cancer. Int J Mol Sci 2019, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferguson-Smith, M.A. History and evolution of cytogenetics. Mol Cytogenet 2015, 8, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Richer, C.L.; Murer-Orlando, M.; Drouin, R. R-banding of human chromosomes by heat denaturation and Giemsa staining after amethopterin-synchronization. Can J Genet Cytol 1983, 25, 261–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.; Chen, J. Chromosome Bandings. Methods Mol Biol 2017, 1541, 59–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liehr, T. International System for Human Cytogenetic or Cytogenomic Nomenclature (ISCN): Some Thoughts. Cytogenet Genome Res 2021, 161, 223–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, A. Proposed standard system of nomenclature of human mitotic chromosomes. N Engl J Med 1960, 262, 1245–1246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wegner, R.-D. Diagnostic cytogenetics; Springer Science & Business Media: 2013.

- Yunis, J.J. High resolution of human chromosomes. Science 1976, 191, 1268–1270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, M.; Butler, M.G. Prader-Willi syndrome and atypical submicroscopic 15q11-q13 deletions with or without imprinting defects. Eur J Med Genet 2016, 59, 584–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooley, L.D.; Morton, C.C.; Sanger, W.G.; Saxe, D.F.; Mikhail, F.M. Section E6.5-6.8 of the ACMG technical standards and guidelines: chromosome studies of lymph node and solid tumor-acquired chromosomal abnormalities. Genet Med 2016, 18, 643–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikhail, F.M.; Heerema, N.A.; Rao, K.W.; Burnside, R.D.; Cherry, A.M.; Cooley, L.D. Section E6.1-6.4 of the ACMG technical standards and guidelines: chromosome studies of neoplastic blood and bone marrow-acquired chromosomal abnormalities. Genet Med 2016, 18, 635–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cherry, A.M.; Akkari, Y.M.; Barr, K.M.; Kearney, H.M.; Rose, N.C.; South, S.T.; Tepperberg, J.H.; Meck, J.M. Diagnostic cytogenetic testing following positive noninvasive prenatal screening results: a clinical laboratory practice resource of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics (ACMG). Genet Med 2017, 19, 845–850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Varon R, D.I., Chrzanowska KH. Nijmegen Breakage Syndrome. 1999 May 17 [Updated 2023 Nov 30]. In: Adam MP, Feldman J, Mirzaa GM, et al., editors. GeneReviews. GeneReviews [Internet]. Seattle (WA): University of Washington, Seattle 1993.

- Taylor, A.M. Chromosome instability syndromes. Best Pract Res Clin Haematol 2001, 14, 631–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sutherland, G.R.; Baker, E. The clinical significance of fragile sites on human chromosomes. Clin Genet 2000, 58, 157–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bridge, J.A. Advantages and limitations of cytogenetic, molecular cytogenetic, and molecular diagnostic testing in mesenchymal neoplasms. J Orthop Sci 2008, 13, 273–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vajen, B.; Hanselmann, S.; Lutterloh, F.; Kafer, S.; Espenkotter, J.; Beening, A.; Bogin, J.; Schlegelberger, B.; Gohring, G. Classification of fluorescent R-Band metaphase chromosomes using a convolutional neural network is precise and fast in generating karyograms of hematologic neoplastic cells. Cancer Genet 2022, 260-261, 23–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walter, W.; Haferlach, C.; Nadarajah, N.; Schmidts, I.; Kuhn, C.; Kern, W.; Haferlach, T. How artificial intelligence might disrupt diagnostics in hematology in the near future. Oncogene 2021, 40, 4271–4280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pardue, M.L.; Gall, J.G. Molecular hybridization of radioactive DNA to the DNA of cytological preparations. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1969, 64, 600–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinkel, D.; Straume, T.; Gray, J.W. Cytogenetic analysis using quantitative, high-sensitivity, fluorescence hybridization. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1986, 83, 2934–2938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riegel, M. Human molecular cytogenetics: From cells to nucleotides. Genet Mol Biol 2014, 37 (Suppl. 1), 194–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shakoori, A.R. Fluorescence In Situ Hybridization (FISH) and Its Applications. Chromosome Structure and Aberrations 2017, 343–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, E. Technical review: In situ hybridization. Anat Rec (Hoboken) 2014, 297, 1349–1353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yi Ning, A.R. , Smith, A. C. M., Macha, M., Precht, K., Riethman, H., Ledbetter, D. H., Flint, J., Horsley, S., Regan, R., Kearney, L., Knight, S., Kvaloy, K., & Brown, W. R. A. A complete set of human telomeric probes and their clinical application. National Institutes of Health and Institute of Molecular Medicine collaboration. Nat Genet 1996, 14, 86–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ried, T.; Schrock, E.; Ning, Y.; Wienberg, J. Chromosome painting: a useful art. Hum Mol Genet 1998, 7, 1619–1626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayani, J.; Squire, J.A. Advances in the detection of chromosomal aberrations using spectral karyotyping. Clin Genet 2001, 59, 65–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bejjani, B.A.; Shaffer, L.G. Clinical utility of contemporary molecular cytogenetics. Annu Rev Genomics Hum Genet 2008, 9, 71–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazaryan-Petersen, L.; Eisfeldt, J.; Pettersson, M.; Lundin, J.; Nilsson, D.; Wincent, J.; Lieden, A.; Lovmar, L.; Ottosson, J.; Gacic, J.; et al. Replicative and non-replicative mechanisms in the formation of clustered CNVs are indicated by whole genome characterization. PLoS Genet 2018, 14, e1007780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suttorp, J.; Luhmann, J.L.; Behrens, Y.L.; Gohring, G.; Steinemann, D.; Reinhardt, D.; Neuhoff, N.V.; Schneider, M. Optical Genome Mapping as a Diagnostic Tool in Pediatric Acute Myeloid Leukemia. Cancers (Basel) 2022, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahajpal, N.S.; Mondal, A.K.; Fee, T.; Hilton, B.; Layman, L.; Hastie, A.R.; Chaubey, A.; DuPont, B.R.; Kolhe, R. Clinical Validation and Diagnostic Utility of Optical Genome Mapping in Prenatal Diagnostic Testing. J Mol Diagn 2023, 25, 234–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forde, B.M.; Bergh, H.; Cuddihy, T.; Hajkowicz, K.; Hurst, T.; Playford, E.G.; Henderson, B.C.; Runnegar, N.; Clark, J.; Jennison, A.V.; et al. Clinical Implementation of Routine Whole-genome Sequencing for Hospital Infection Control of Multi-drug Resistant Pathogens. Clin Infect Dis 2023, 76, e1277–e1284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, R.; Kim, S.; Oh, B.B.; Yu, W.S.; Kim, C.W.; Hur, H.; Son, S.Y.; Yang, M.J.; Cho, D.S.; Ha, T.; et al. Clinical application of whole-genome sequencing of solid tumors for precision oncology. Exp Mol Med 2024, 56, 1856–1868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mody, R.J.; Wu, Y.M.; Lonigro, R.J.; Cao, X.; Roychowdhury, S.; Vats, P.; Frank, K.M.; Prensner, J.R.; Asangani, I.; Palanisamy, N.; et al. Integrative Clinical Sequencing in the Management of Refractory or Relapsed Cancer in Youth. JAMA 2015, 314, 913–925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Das, K.; Tan, P. Molecular cytogenetics: recent developments and applications in cancer. Clin Genet 2013, 84, 315–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dimashkieh, H.; Wolff, D.J.; Smith, T.M.; Houser, P.M.; Nietert, P.J.; Yang, J. Evaluation of urovysion and cytology for bladder cancer detection: a study of 1835 paired urine samples with clinical and histologic correlation. Cancer Cytopathol 2013, 121, 591–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balciuniene, J.; Ning, Y.; Lazarus, H.M.; Aikawa, V.; Sherpa, S.; Zhang, Y.; Morrissette, J.J.D. Cancer cytogenetics in a genomics world: Wedding the old with the new. Blood Rev 2024, 66, 101209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Honore, N.; Galot, R.; van Marcke, C.; Limaye, N.; Machiels, J.P. Liquid Biopsy to Detect Minimal Residual Disease: Methodology and Impact. Cancers (Basel) 2021, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Firth, H.V.; Richards, S.M.; Bevan, A.P.; Clayton, S.; Corpas, M.; Rajan, D.; Van Vooren, S.; Moreau, Y.; Pettett, R.M.; Carter, N.P. DECIPHER: Database of Chromosomal Imbalance and Phenotype in Humans Using Ensembl Resources. Am J Hum Genet 2009, 84, 524–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitelman F, J.B.a.M.F.E. Mitelman Database of Chromosome Aberrations and Gene Fusions in Cancer. 2025.

- Sayers, E.W.; Beck, J.; Bolton, E.E.; Bourexis, D.; Brister, J.R.; Canese, K.; Comeau, D.C.; Funk, K.; Kim, S.; Klimke, W.; et al. Database resources of the National Center for Biotechnology Information. Nucleic Acids Res 2021, 49, D10–D17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacDonald, J.R.; Ziman, R.; Yuen, R.K.; Feuk, L.; Scherer, S.W. The Database of Genomic Variants: a curated collection of structural variation in the human genome. Nucleic Acids Res 2014, 42, D986–992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karczewski, K.J.; Francioli, L.C.; Tiao, G.; Cummings, B.B.; Alfoldi, J.; Wang, Q.; Collins, R.L.; Laricchia, K.M.; Ganna, A.; Birnbaum, D.P.; et al. The mutational constraint spectrum quantified from variation in 141,456 humans. Nature 2020, 581, 434–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sondka, Z.; Dhir, N.B.; Carvalho-Silva, D.; Jupe, S.; Madhumita; McLaren, K.; Starkey, M.; Ward, S.; Wilding, J.; Ahmed, M.; et al. COSMIC: a curated database of somatic variants and clinical data for cancer. Nucleic Acids Res 2024, 52, D1210–D1217. [CrossRef]

- Tomczak, K.; Czerwinska, P.; Wiznerowicz, M. The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA): an immeasurable source of knowledge. Contemp Oncol (Pozn) 2015, 19, A68–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, J.; Aksoy, B.A.; Dogrusoz, U.; Dresdner, G.; Gross, B.; Sumer, S.O.; Sun, Y.; Jacobsen, A.; Sinha, R.; Larsson, E.; et al. Integrative analysis of complex cancer genomics and clinical profiles using the cBioPortal. Sci Signal 2013, 6, pl1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Landrum, M.J.; Chitipiralla, S.; Brown, G.R.; Chen, C.; Gu, B.; Hart, J.; Hoffman, D.; Jang, W.; Kaur, K.; Liu, C.; et al. ClinVar: improvements to accessing data. Nucleic Acids Res 2020, 48, D835–D844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinreich, S.S.; Mangon, R.; Sikkens, J.J.; Teeuw, M.E.; Cornel, M.C. [Orphanet: a European database for rare diseases]. Ned Tijdschr Geneeskd 2008, 152, 518–519. [Google Scholar]

- DePristo, M.A.; Banks, E.; Poplin, R.; Garimella, K.V.; Maguire, J.R.; Hartl, C.; Philippakis, A.A.; del Angel, G.; Rivas, M.A.; Hanna, M.; et al. A framework for variation discovery and genotyping using next-generation DNA sequencing data. Nat Genet 2011, 43, 491–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poplin, R.; Chang, P.C.; Alexander, D.; Schwartz, S.; Colthurst, T.; Ku, A.; Newburger, D.; Dijamco, J.; Nguyen, N.; Afshar, P.T.; et al. A universal SNP and small-indel variant caller using deep neural networks. Nat Biotechnol 2018, 36, 983–987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danecek, P.; Bonfield, J.K.; Liddle, J.; Marshall, J.; Ohan, V.; Pollard, M.O.; Whitwham, A.; Keane, T.; McCarthy, S.A.; Davies, R.M.; et al. Twelve years of SAMtools and BCFtools. Gigascience 2021, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raney, B.J.; Barber, G.P.; Benet-Pages, A.; Casper, J.; Clawson, H.; Cline, M.S.; Diekhans, M.; Fischer, C.; Navarro Gonzalez, J.; Hickey, G.; et al. The UCSC Genome Browser database: 2024 update. Nucleic Acids Res 2024, 52, D1082–D1088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newman, V.; Moore, B.; Sparrow, H.; Perry, E. The Ensembl Genome Browser: Strategies for Accessing Eukaryotic Genome Data. Methods Mol Biol 2018, 1757, 115–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ono, K.; Fong, D.; Gao, C.; Churas, C.; Pillich, R.; Lenkiewicz, J.; Pratt, D.; Pico, A.R.; Hanspers, K.; Xin, Y.; et al. Cytoscape Web: bringing network biology to the browser. Nucleic Acids Res 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thorvaldsdottir, H.; Robinson, J.T.; Mesirov, J.P. Integrative Genomics Viewer (IGV): high-performance genomics data visualization and exploration. Brief Bioinform 2013, 14, 178–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krzywinski, M.; Schein, J.; Birol, I.; Connors, J.; Gascoyne, R.; Horsman, D.; Jones, S.J.; Marra, M.A. Circos: an information aesthetic for comparative genomics. Genome Res 2009, 19, 1639–1645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lawson, D.J.; Hellenthal, G.; Myers, S.; Falush, D. Inference of population structure using dense haplotype data. PLoS Genet 2012, 8, e1002453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iourov, I.Y.; Vorsanova, S.G.; Yurov, Y.B. Systems Cytogenomics: Are We Ready Yet? Curr Genomics 2021, 22, 75–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirzaghaderi, G.; and Marzangi, K. IdeoKar: an ideogram constructing and karyotype analyzing software. Caryologia 2015, 68, 31–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armstrong, K.C.; Craig, I.L.; Merritt, C. Hordeum chilense (2n = 14) computer-assisted Giemsa karyotypes. Genome 1987, 29, 683–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, D.M.; Myers, P.Z.; Reyna, D.L. CHROMPAC III: an improved package for microcomputer-assisted analysis of karyotypes. J Hered 1984, 75, 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGurk, J.; Rivlin, K. A BASIC computer program for chromosome measurement and analysis. Journal of Heredity 1983, 74, 304–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilbert, C.W. A computer programme for the analysis of human chromosomes. Nature 1966, 212, 1437–1440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oud, J.L.; Kakes, P.; De Jong, J.H. Computerized analysis of chromosomal parameters in karyotype studies. Theor Appl Genet 1987, 73, 630–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukui, K. Standardization of karyotyping plant chromosomes by a newly developed chromosome image analyzing system (CHIAS). Theor Appl Genet 1986, 72, 27–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reeves, A. MicroMeasure: a new computer program for the collection and analysis of cytogenetic data. Genome 2001, 44, 439–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- König, C.; and Ebert, I. Computer-aided quantitative analysis of banded karyotypes, exemplified in C-banded Hyacinthoides italica s.l. (Hyacinthaceae). Caryologia 1997, 50, 105–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiller, B.; Bradtke, J.; Balz, H.; Rieder, H. CyDAS: a cytogenetic data analysis system. Bioinformatics 2005, 21, 1282–1283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; LaFramboise, T. CytoConverter: a web-based tool to convert karyotypes to genomic coordinates. BMC Bioinformatics 2019, 20, 467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abrams, Z.B.; Zhang, L.; Abruzzo, L.V.; Heerema, N.A.; Li, S.; Dillon, T.; Rodriguez, R.; Coombes, K.R.; Payne, P.R.O. CytoGPS: a web-enabled karyotype analysis tool for cytogenetics. Bioinformatics 2019, 35, 5365–5366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abrams, Z.B.; Tally, D.G.; Abruzzo, L.V.; Coombes, K.R. RCytoGPS: an R package for reading and visualizing cytogenetics data. Bioinformatics 2021, 37, 4589–4590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thinh, N.H.; Son, N.H.H.; Huong, P.T.V.; Nhung, N.T.C.; Ram, D.T.; Minh, N.T.B.; Ha, L.M. A Web-based Tool for Semi-interactively Karyotyping the Chromosome Images for Analyzing Chromosome Abnormalities. Proceedings of 2020 7th NAFOSTED Conference on Information and Computer Science (NICS), 26-27 Nov. 2020; pp. 433–437. [Google Scholar]

- Uttamatanin, R.; Yuvapoositanon, P.; Intarapanich, A.; Kaewkamnerd, S.; Phuksaritanon, R.; Assawamakin, A.; Tongsima, S. MetaSel: a metaphase selection tool using a Gaussian-based classification technique. BMC Bioinformatics 2013, 14 Suppl 16, S13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Wang, Q.; Zhang, Z.; He, X.; Yu, Y. MATO: An updated tool for capturing and analyzing cytotaxonomic and morphological data. The Innovation Life 2023, 1, 100010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altınordu, F.; Peruzzi, L.; Yu, Y.; He, X. A tool for the analysis of chromosomes: KaryoType. TAXON 2016, 65, 586–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahry, E.; Breimann, L.; Zouinkhi, M.; Epstein, L.; Kolyvanov, K.; Mamrak, N.; King, B.; Long, X.; Harrington, K.I.S.; Lionnet, T.; et al. RS-FISH: precise, interactive, fast, and scalable FISH spot detection. Nat Methods 2022, 19, 1563–1567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schindelin, J.; Arganda-Carreras, I.; Frise, E.; Kaynig, V.; Longair, M.; Pietzsch, T.; Preibisch, S.; Rueden, C.; Saalfeld, S.; Schmid, B.; et al. Fiji: an open-source platform for biological-image analysis. Nat Methods 2012, 9, 676–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Almagro-Garcia, J.; Manske, M.; Carret, C.; Campino, S.; Auburn, S.; Macinnis, B.L.; Maslen, G.; Pain, A.; Newbold, C.I.; Kwiatkowski, D.P.; et al. SnoopCGH: software for visualizing comparative genomic hybridization data. Bioinformatics 2009, 25, 2732–2733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milan, S. Karyotyping Software: 5 Best to map your Chromosomes. 2023.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).