1. Introduction

Subsurface currents are one of the essential climate variables defined by the Global Climate Observing System or GCOS (

https://gcos.wmo.int/en/essential-climate-variables). In situ measurements can be made by Eulerian methods where instruments are on fixed moorings, or Lagrangian methods where instruments are surface or subsurface buoys ‘anchored’ in a water mass, the trajectory of which can be followed by satellites. This study concentrates on the Eulerian method where measurements are made with Doppler effect acoustic instruments that can be standalone or vessel-mounted. The assessment of uncertainties in current measurements made by these instruments, is a task that has been unsatisfactorily or at best incompletely solved to date, because of the inherent complexity of the measurement principle and also because of multiple factors contributing to the velocity uncertainty. This paper proposes a method to fill this gap.

Standalone instruments can be single-points or profilers that is to say, they can measure the velocity of water masses in a single layer or in several layers from the seabed or from the surface. They can be mounted on mooring cages deployed on the seabed or on mooring lines. On mooring lines or on the seabed they can be inclined compared to the vertical position. This inclination must be corrected to retrieve the vertical and the horizontal components of the current, and for this purpose they are equipped with tilt sensors. The direction and the amplitude of currents is retrieved at first, in the instrument body by at least three slanted beams that make a vectoral measurement of the velocity and then in the Earth framework by a matrix calculation that uses measured tilt angles and angular directions. For standalone instruments, the angular direction in relation to the magnetic North, is retrieved with a magnetic compass, and the direction in relation with the true North is retrieved by applying a correction of magnetic declination. For vessel mounted instruments, the direction and inclination are given by the inertial navigation system of the boat.

The velocity measured by standalone current-meters and current profilers can be calibrated, and an estimate of their measurement uncertainties can be made in hydrodynamic channels [

1] or by carrying out inter-comparisons at sea as it was carried out in 2012 [

2] or in rivers [

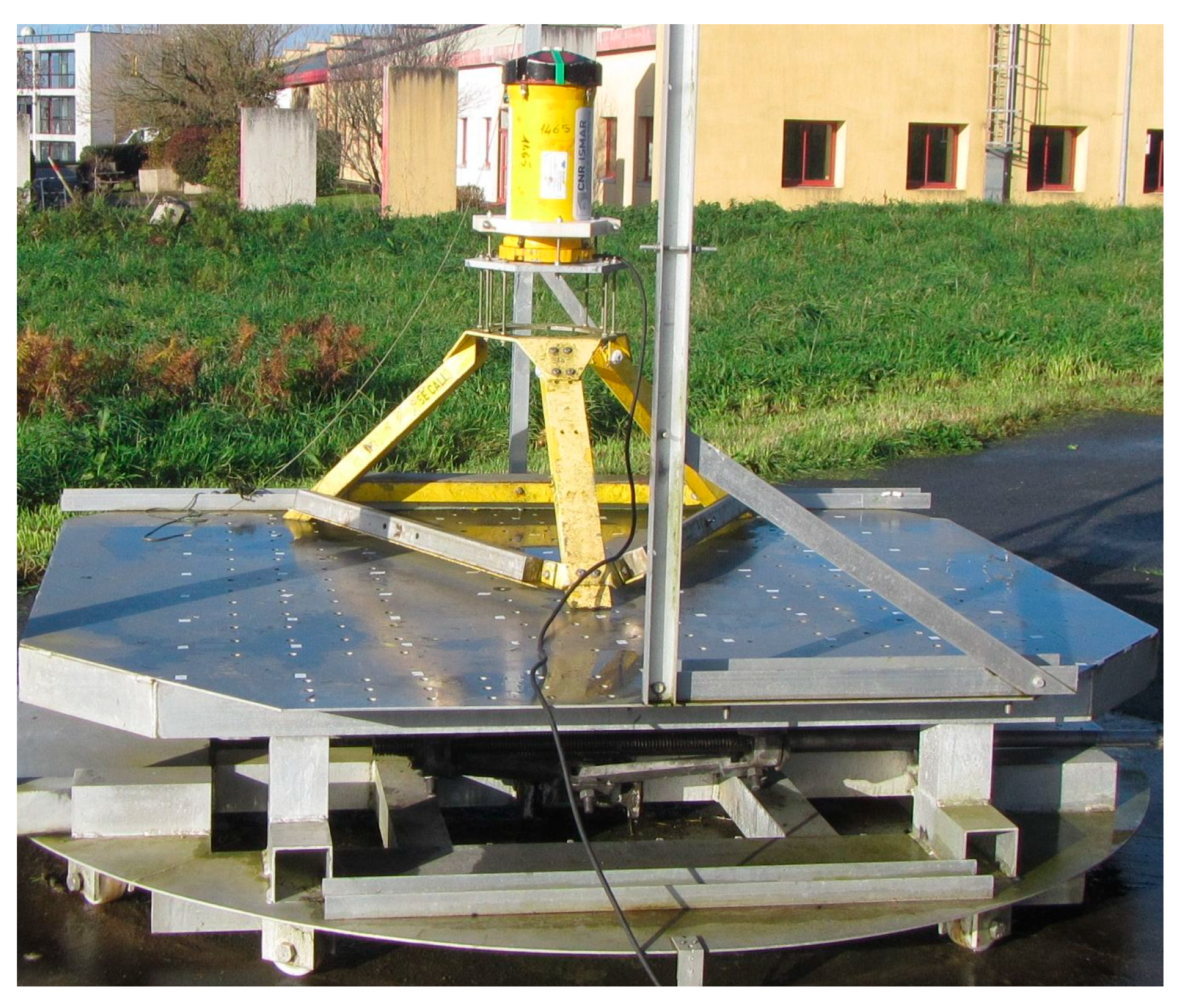

3], but these inter-comparisons are expensive, difficult to organize, and they allow only one part of the velocity range of instruments to be tested. In addition, these two methods do not allow an estimation of errors of each sensor of the instrument separately and the calibration uncertainty can be hardly determined. In 2007 a first publication described a method to calibrate the compass of current-meters [

4], and in 2014, a second publication described a method to calibrate the compass and the tilt sensors of these instruments [

5] (see

Figure 1). In 2020, a third publication described a method to detect the Doppler effect measurement errors made by the transducers of current-meters and profilers, and it quantified the uncertainty of this calibration [

6]. It should be noted that in 2015, another method was published by von Appen to correct compass errors linked to nearby metal masses, and applied to ADCP-equipped (Acoustic Doppler Current Profiler) buoys deployed in Greenland [

7]. In 2023, another publication demonstrated the impact of different elements of moorings, on the accuracy of compass measurements, and it opened the way to best practices [

8].

However, if the uncertainties of direction and velocity measurements can be assessed by these techniques, a method is missing to propagate the uncertainties they quantify, on the current measurements made in situ. The “Guide to the expression of uncertainty in measurement” or GUM [

9] edited by the BIPM, proposes a method based on the law of variance composition to assess a combined measurement uncertainty from a physical relation called measurement model. This model must describe the impact of the variations of input quantities on a single output quantity. The supplement 2 to the GUM [

10] edited in 2011 or JCGM102: 2011, proposes a standardized method that can be applied to measurement models having any number of input and output quantities. The multi-beams Doppler current-meters and profilers respond to this kind of measurement model. Each acoustic transducer is sensitive to the same input variables and the velocities components

U,

V,

W calculated in the earth framework are sensitive to the same measured velocities and direction quantities. The difficulty lies in the assessment of the standard uncertainties of the input variables.

This publication proposes to apply the JCGM102: 2011 method to evaluate the impact on current measurements of uncertainties on the input quantities that participate to standalone Doppler current-meters and profiler’s measurement, in the case of four-beam current profilers. Numerical applications and simulations based on two commonly used instruments, are given to validate the theoretical developments.

2. Operating Principles of Doppler Current-Meters and Profilers

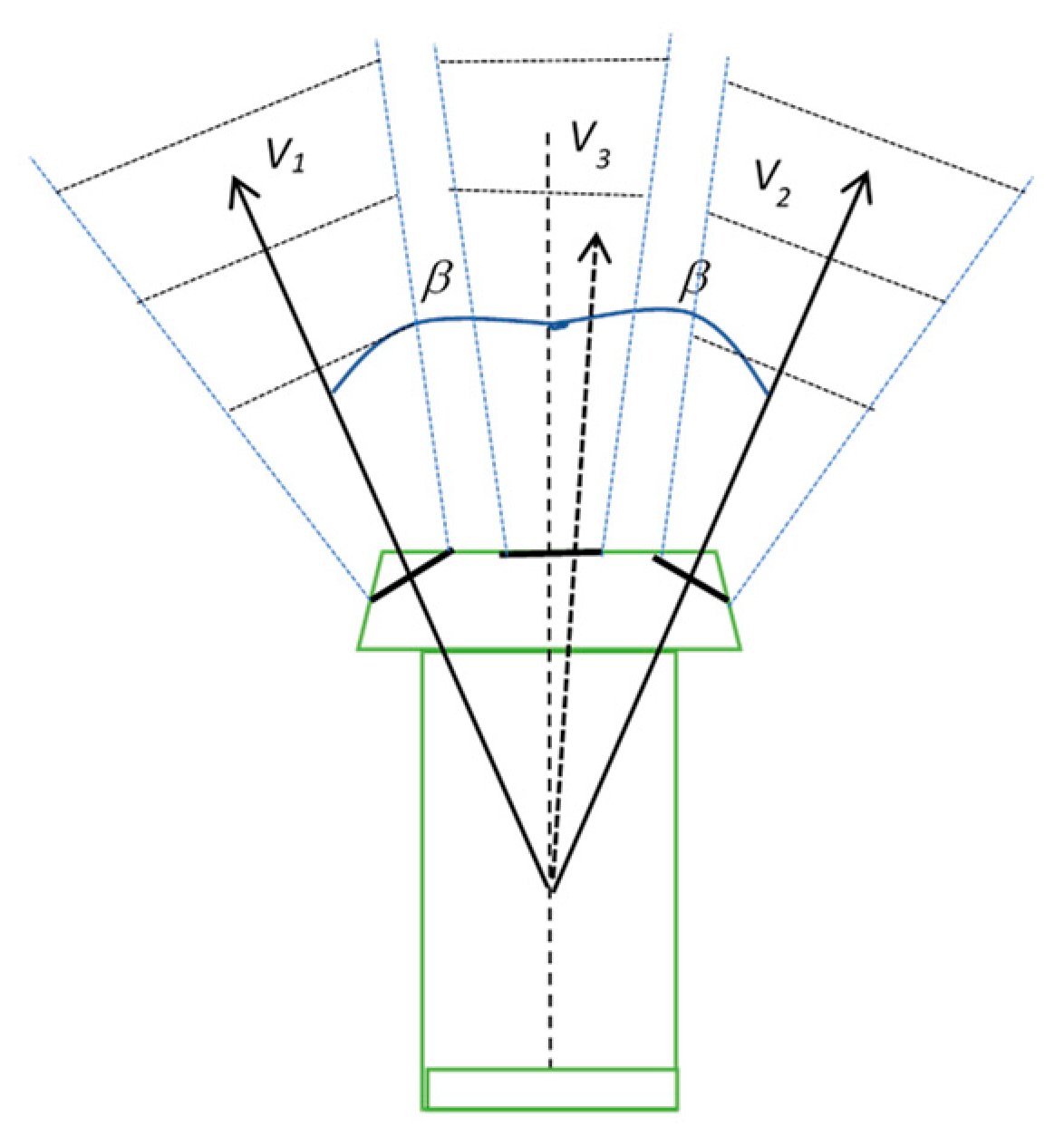

Current-meters and profilers compute velocities (

V1, V2, V3) obtained by Doppler shifts measurements in their beam axes (radial velocities). The transducers are tilted 20 °, 25 ° or 45 ° (angle

β).

β is the Janus angle or slant angle which is accurately determined by the manufacturer (

Figure 2). Most of recent instruments are equipped with a fourth transducer used as rescue when the signal detection is too much degraded for one of the other beams.

Speeds (V1, V2, V3) or (V1, V2, V3, V4) are obtained after the detection of echoes resulting from the reflection of acoustic pulses on the successive layers of particles. To improve measurement trueness, pulses are repeated at a frequency fr. Some instruments can be used in narrowband or broadband mode. A narrowband instrument transmits a single tone burst and uses an autocovariance function to measure the phase or the frequency shift of the return pulses. It is worth noting that broadband techniques so that averaging improve the detection limits of pings in the noise and the profiling range of measurements or the conditions of detection in waters with low levels of particles.

The document [

11] gives formulas to calculate the low limits of the velocity measurement uncertainties of narrow and broadband systems, along the beam path. For a single ping and a narrowband system, the standard deviation

σNB of the horizontal velocity component can be obtained by the Formula (1):

where

f0 is the transmit frequency in Hz and

D the depth cell length in m. For a broadband system, the standard deviation

σBB of the horizontal velocity component can be obtained by the relationship (2):

where

R is the correlation at the time

TL.

R = 0.5 for a 2-pulses system.

TL is the time separating the transmission of two pulses in a 2-pulses system and

c the speed of sound. In this case, the autocorrelation function results are a major peak centred on zero and two side peaks centred on

± TL.

In order to obtain the velocities (

Vx, Vy, Vz) in the referential of the instrument, manufacturers provide transfer matrix that can take different forms according to the orientation given to transducers.

Figure 3 compares the enumeration of transducers and the orientation of rotation axis for the instruments Nortek Signature profiler and Teledyne RD Instruments Workhorse ADCP.

The matrix (3) can be used in the case of Nortek Signature profilers which head orientation is given in

Figure 3:

In the case when the beam angle can vary independently for each beam, the angle

β can be declined in different values

β1,

β2 or

β3. For Teledyne RDI ADCP’s, this matrix takes another form. According to RDI Instruments (1998), for a convex transducer head we have:

The first three rows are the generalized inverse of the beam directional matrix representing the components of each beam in the instrument coordinate system. The last row representing the error velocity, is orthogonal to the other three rows and has been normalized so that its magnitude (root-mean-square) matches the mean of the magnitudes of the first two rows. This normalization has been chosen so that in horizontally homogeneous flows, the variance of the error velocity will indicate the portion of the variance of each of the nominally-horizontal components (X and Y) attributable to instrument noise (short-term error). If one beam is marked bad due to low correlation or fish detection, then a three-beam solution is calculated by the ADCP. If, for example, the beam 4 is bad, the term is replaced by a 0 value which is equivalent to a 3-beam solution.

Current-meters are equipped with ‘flux-gate’, ‘Hall effect’ or magneto-resistive compasses to retrieve the amplitude of current components (

U,

V,

W) in reference to the magnetic North (angle

α), and considering the magnetic declination at the place of measurements, in relation to the true North. Moreover, their inclination is corrected thanks to a tilt sensor measuring roll angles

θ and pitch angles

Ψ. For vessel-mounted instruments, these data come from the attitude sensors of the boat. According to [

12], between 1 and 12 equations can be found to describe a rotation in the three dimensions.

Teledyne RD Instruments describes an inverse rotation matrix to retrieve the values of components (

U, V, W), in its document of 1998, upgraded in 2010 [

13]. For profilers installed on boats, they use the names starboard

S, forward

F, and mast

M, instead of pitch, roll, and heading for the axes. If the beam 3 is aligned with the keel on the forward side of the ADCP, for the downward-looking orientation, these axes are identical to the instrument axes:

S =

X,

F =

Y,

M =

Z. For the upward-looking orientation,

S = -

X,

F =

Y,

M = -Z. In earth coordinates, the roll, pitch, and heading angles correspond to

Y axis,

X axis and

Zaxis(downward looking). This description corresponds to the right schematic of

Figure 3. To retrieve the components (

U,

V,

W), they use the following rotation matrix [

6]:

Velocities

V1,

V2,

V3 and

V4 of matrix (3) and (4) are obtained after the detection of echoes resulting from the reflection of pulses on successive layers of particles that are carried along by the currents. This displacement creates a frequency shift

δfi (

i ∈{1, 2, 3, 4}) called Doppler shift. Echoes are measured continuously, allowing the size of measurement cells in the water column to be determined (

Figure 2), considering the value of the speed of sound in seawater

c and the duration

tp of pulses. The lowest uncertainty that can be obtained for the measurements of (

V1, V2, V3, V4) is limited by the standard deviation of the Doppler noise

σδ, which is inversely proportional to

tp. This noise is generated by the random displacement of particles, the multiple echoes and the detection limits of the instrument electronics. Different techniques exist to extract the signal from the noise and to improve the detection limit (see [

14], or [

15], or [

11], or [

16]). If

f0 is the emitted frequency, the measured radial velocity is obtained by the Doppler effect relationship:

In this relation,

c is programmed in the instrument by the user or calculated by a relation using temperature, pressure measurements and sometimes a value of practical salinity.

4. Numerical Applications and Results

There are so many different current-meters and current profilers and so many ways of configuring and using them, that it is impossible to obtain a unique numerical result representing the measurement uncertainty that can be expected from these instruments. In order to see how the relationships of the section 3 can be applied and in order to give an order of magnitude of the final uncertainties that can be found, numerical applications have been made based on a Nortek Signature 500 kHz and on a 600 kHz RD Instrument Workhorse Sentinel. These instruments have frequencies in the average of the frequency range of the commercially available instruments and they are widely used in oceanography.

The Nortek Signature 500 kHz has a slant angle

β = 25 °. The uncertainty

uβ on the determination of this slant angle is unknown, but the standard ISO 2768 [

19] determines classes of tolerances on angles in mechanical parts manufacturing. The higher class allows to define angles to 0° 5′ or 0.083 ° (0.0014 rad). This value will be taken as an example to define the uncertainty

uβ, but without any real knowledge of what can be obtained by manufacturers.

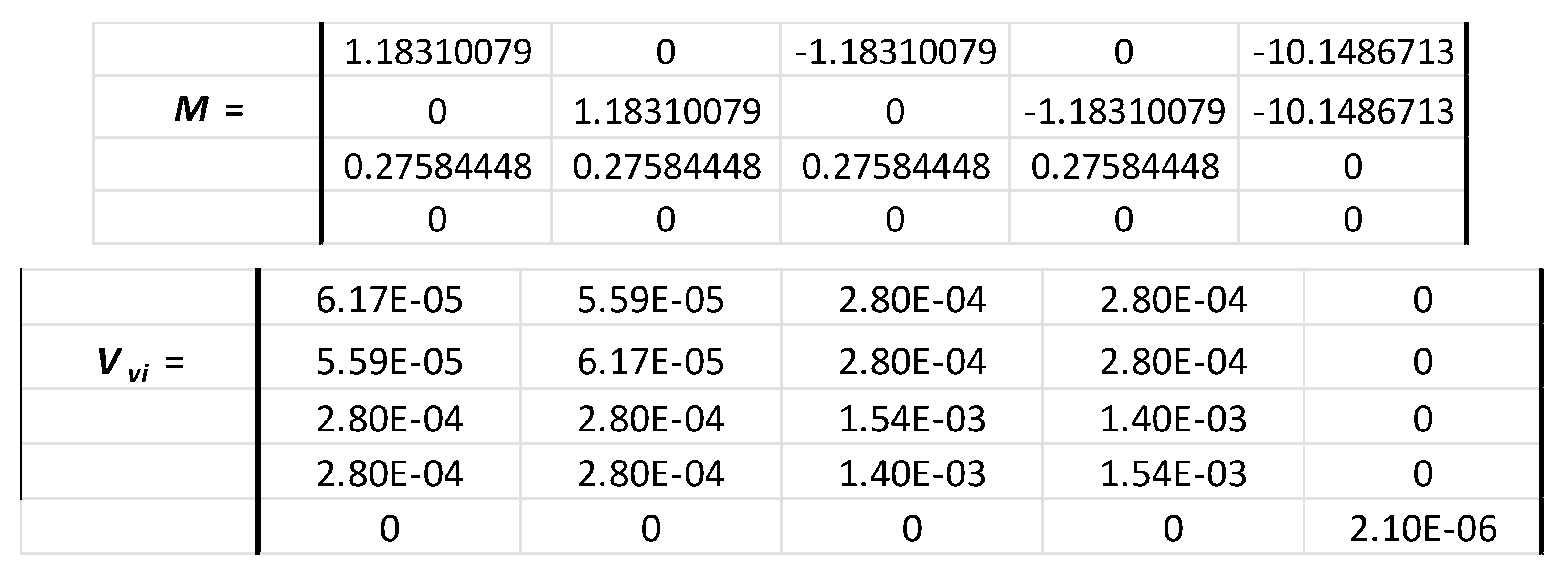

With V1 = -1 m/s, V2 = 1 m/s, V3 = - 5 m/s and V4 = 5 m/s, we have uV1 = uV2 = 0.008 m/s, and uV3 = uV4 = 0.039 m/s by considering a maximal uncertainty of 20 m/s on the speed of sound c. That gives the matrix:

and uVx = uVy = 0.041 m/s, and uVz = 0.025 m/s, with Vx = 4.732 m/s, Vy = 1.183 m/s and Vz = - 1.379 m/s. If we consider now that β is perfectly determined and has no uncertainty, the values of uVx and uVy become a little bit smaller: uVx = uVy = 0.038 m/s, and we have always uVz = 0.025 m/s. Therefore, this calculation shows that the uncertainties on the measured speeds are slightly sensitive to the slant angle of beams and that the smallest uncertainty allowed on the manufacturing has a small impact on the horizontal measured velocities. That highlights the necessity for manufacturers to compensate it with adjusted values of β in matrix (3) and (4), and to communicate about it.

If the heading, roll and pitch angles are taken to be 0 °,

U =

Vx,

V =

Vy and

W =

Vz. Using the calibration platform described in [

8] or [

5], the typical standard uncertainties that can be obtained on heading, roll and pitch angles are:

uα = 0.59 °,

uθ = 0.21 ° and

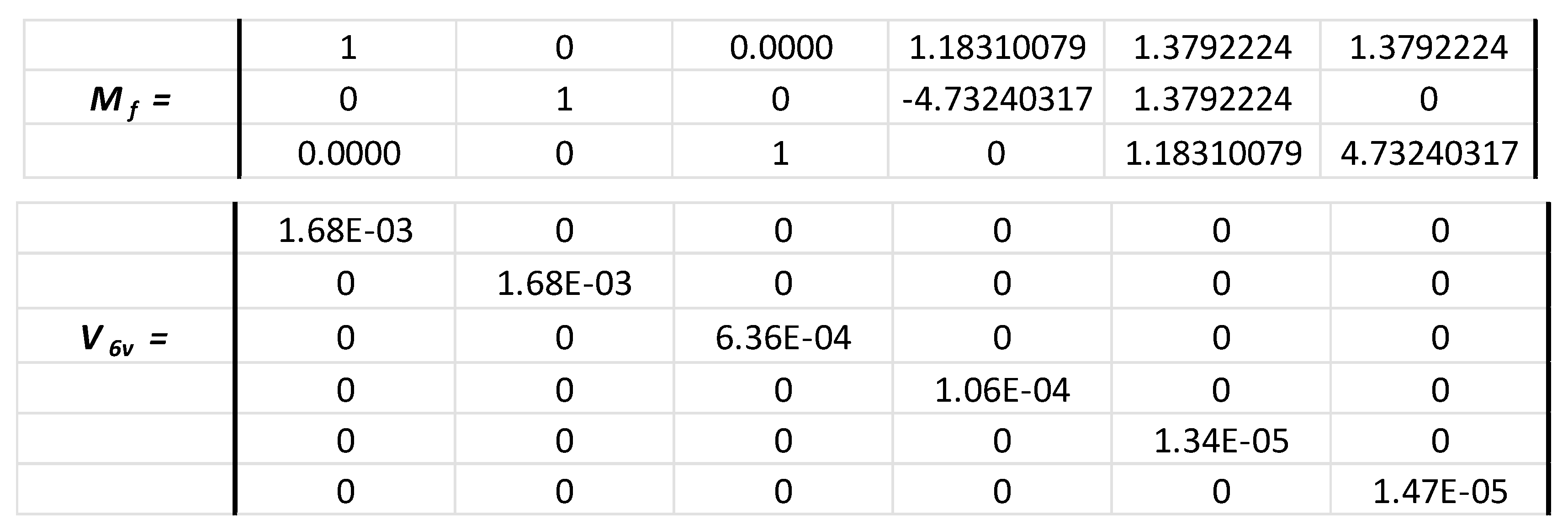

= 0.22 °. That gives the matrix:

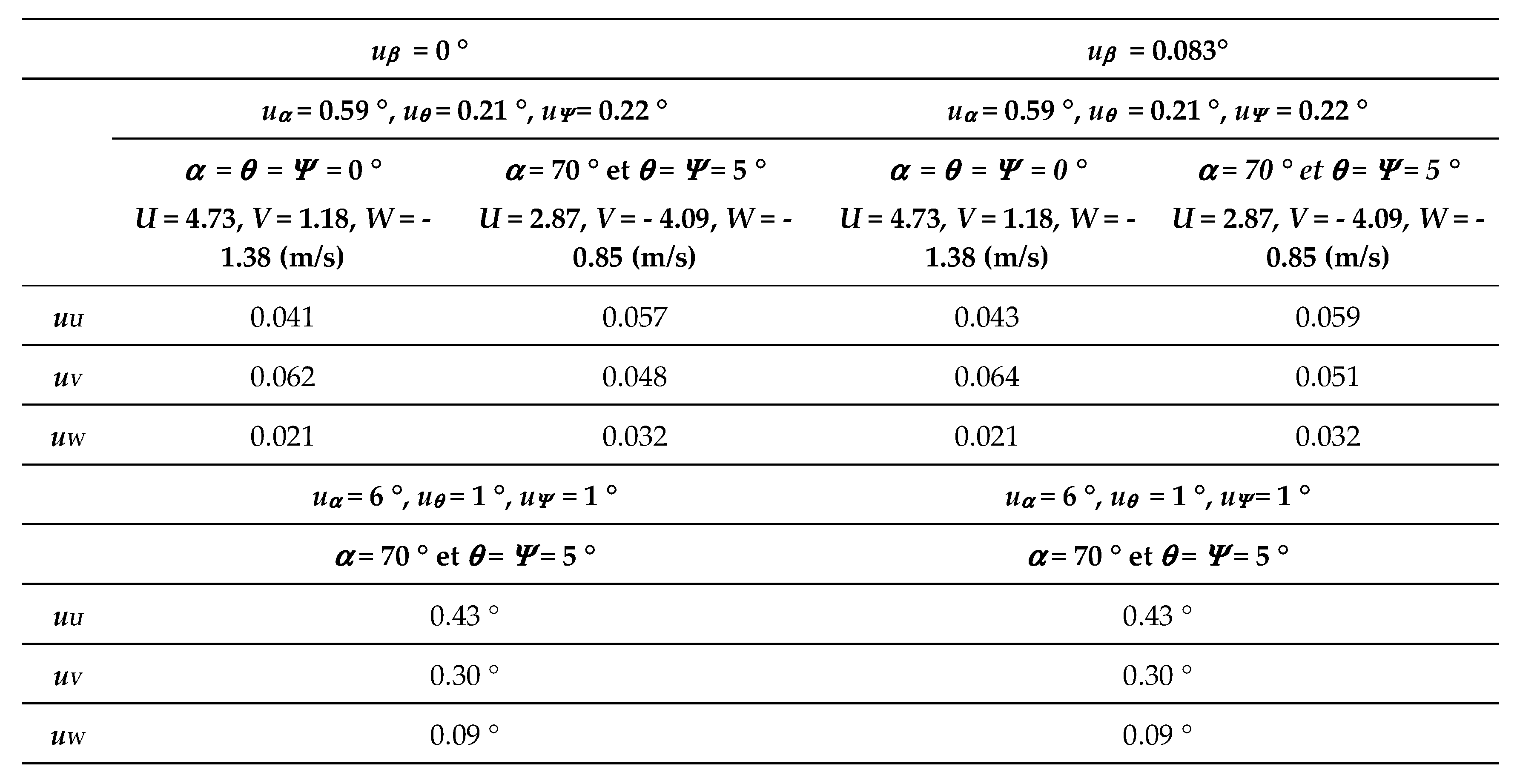

The relationship (15) gives uU = 0.043 m/s, uV = 0.064 m/s and uW = 0.021 m/s. In the case when uβ = 0 °, uU = 0.041 m/s, uV = 0.062 m/s and uW = 0.021 m/s.

If now the profiler is turned by α = 70 ° and tilted by θ = = 5 °, the values of U, V and W are different (U = 2.87 m/s, V = - 4.09 m/s and W = - 0.85 m/s) so that their measurement uncertainties: uU = 0.059 m/s, uV = 0.051 m/s and uW = 0.032 m/s. If uβ = 0 °, uU = 0.057 m/s, uV = 0.048 m/s and uW = 0.032 m/s.

Bias are often found on compass and tilt sensors after several years of using. Let us suppose that these biases are not corrected and considered as uncertainties, and that uα = 6 °, uθ = 1 ° and = 1 ° which are error values currently found. In this case, the calculation gives: uU = 0.43 m/s, uV = 0.30 m/s and uW = 0.09 m/s. If uβ = 0 °, the uncertainties remain the same: uU = 0.43 m/s, uV = 0.30 m/s and uW = 0.09 m/s. The uncertainties on U and V are very large and dominated by the compass uncertainty. They represent 15 % and 7 % of the measured value. To check their trueness, we just need to look at how U, V and W vary when α, θ and go respectively from 70 ° to 76 ° and from 5 ° to 5.8 °. The differences obtained by using the matrix (5) is δU = 0.42 °, δV = 0.28 ° and δW = 0.08 ° which is very close of values found for uU, uV and uW.

This simulation shows the importance of correcting the compass and tilt sensors errors to make these uncertainties equivalent to the calibration uncertainties. All these results are resumed in

Table 2.

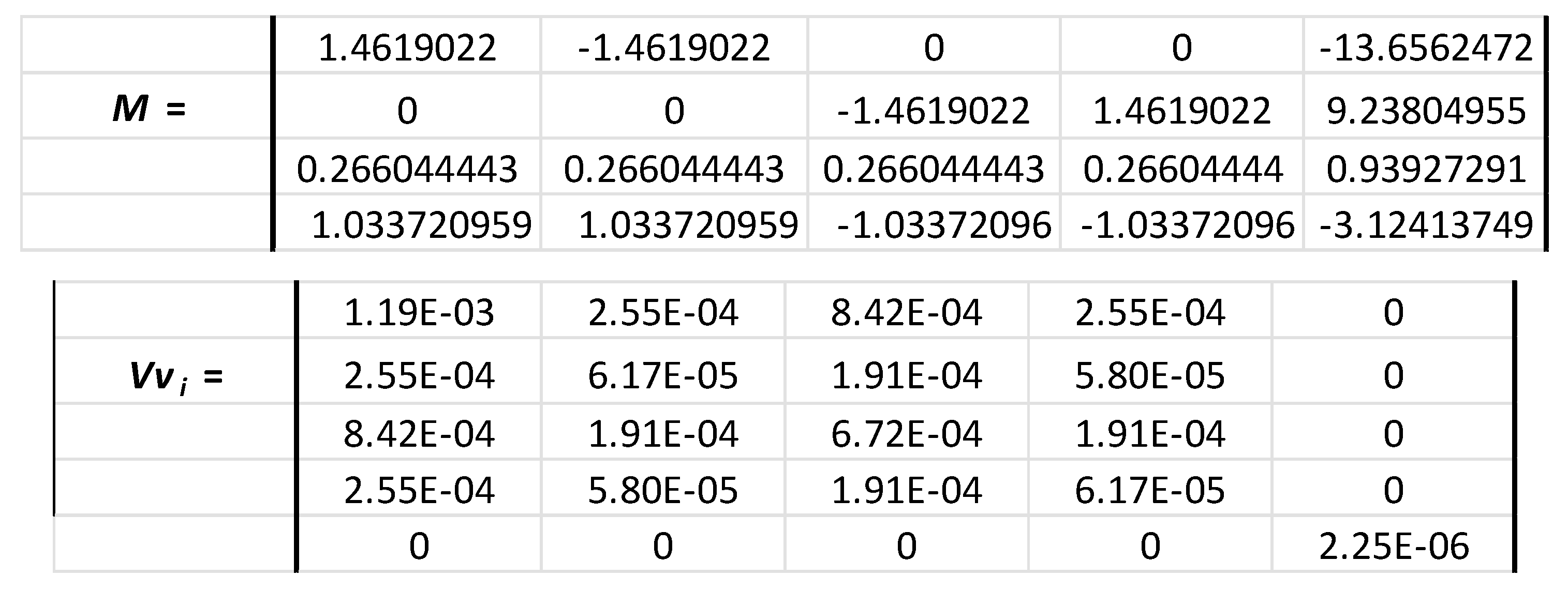

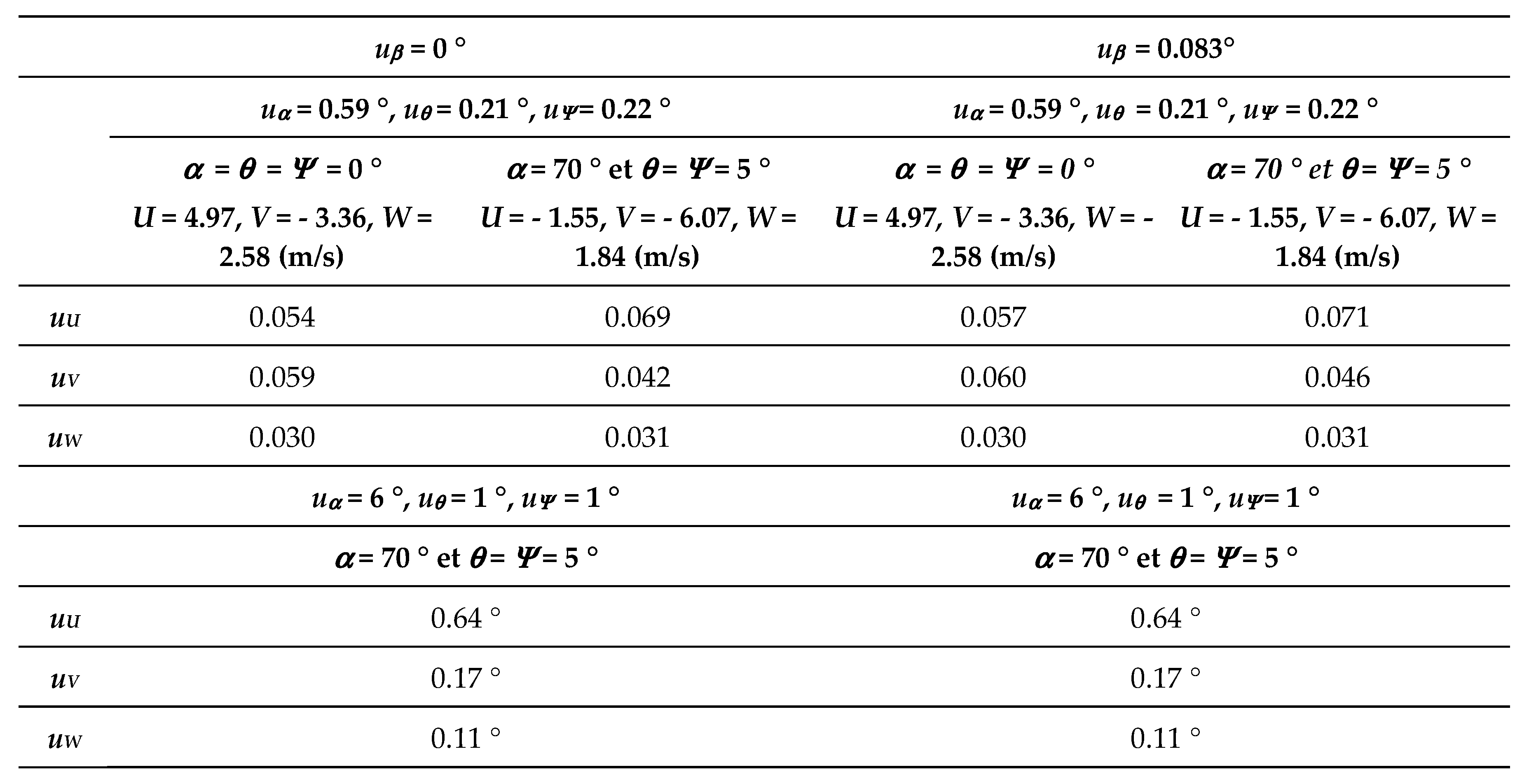

The same numerical applications can be made on RD Instrument Workhorse Sentinel. The specifications of the 600 kHz are the closest of the 500 kHz Signature. For this instrument, β = 20 °. With V1 = 4.4 m/s, V2 = 1 m/s, V3 = 3.3 m/s and V4 = 1 m/s, we have uV1 = 0.036 m/s, uV3 = 0.026 m/s, and uV2 = uV4 = 0.008 m/s by considering again a maximal uncertainty of 20 m/s on the speed of sound c. That gives the matrix:

and uVx = 0.045 m/s, uVy = 0.030 m/s, uVz = 0.020 m/s and uVe = 0.015 m/s, with Vx = 4.97 m/s, Vy = - 3.36 m/s, Vz = 2.58 m/s and Ve = 1.14 m/s. If we consider now that β is perfectly determine and has no uncertainty, like for the Signature, the values of uVx, uVy are smaller and uVz is unchanged: uVx = 0.040 m/s, uVy = 0.027 m/s, uVz = 0.020 m/s and uVe = 0.014 m/s.

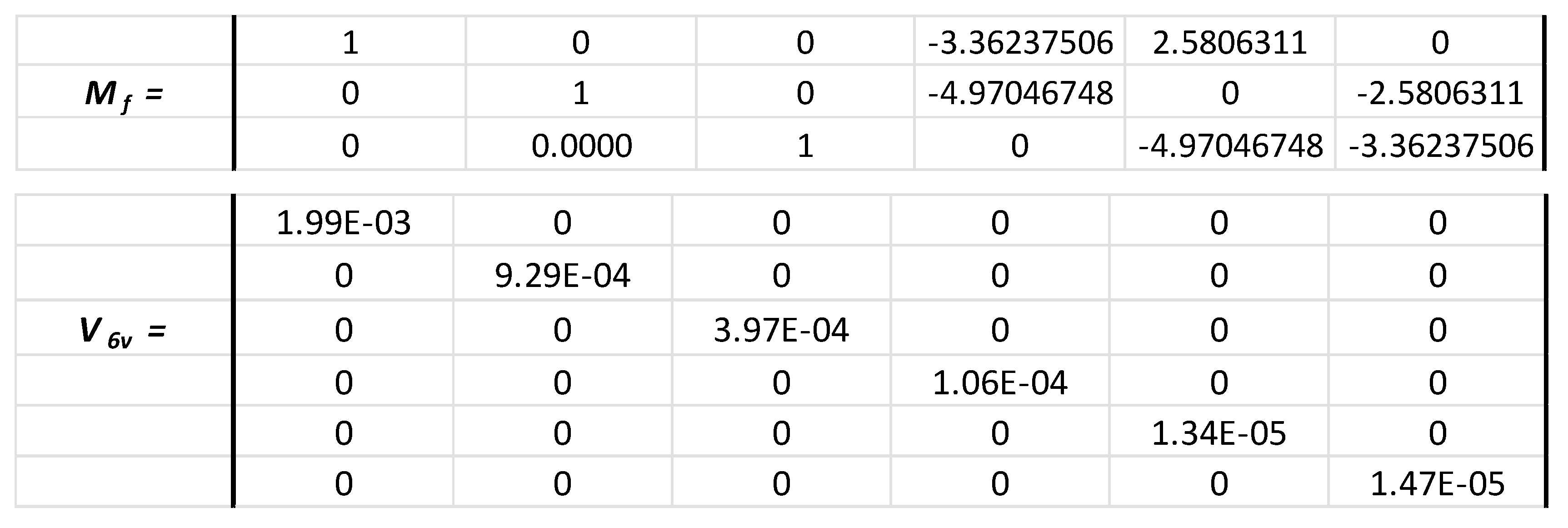

If the heading, roll and pitch angles are taken to be 0 °, U = Vx, U = Vy and W = Vz. Using the previous heading, roll and pitch uncertainty values (uα = 0.59 °, uθ = 0.21 ° and = 0.22 °), that gives the matrix:

We have again uU = 0.057 m/s uV = 0.060 m/s but uW = 0.030 m/s. In the case when uβ = 0 °, uU = 0.054 m/s, uV = 0.059 m/s and uW = 0.030 m/s. These values are of the same order of magnitude as those obtained with the Signature.

If now the profiler is turned by α = 70 ° and tilted by θ = = 5 °, the values of U, V and W are different (U = - 1.55 m/s, V = - 6.07 m/s and W = + 1.84 m/s) and the uncertainties on U, V and W are distributed differently: uU = 0.071 m/s, uV = 0.046 m/s and uW = 0.031 m/s. If uβ = 0 °, uU = 0.069 m/s, uV = 0.042 m/s and uW = 0.031 m/s.

Let us suppose again that

uα = 6 °,

uθ = 1 ° and

uΨ = 1 ° which are error values currently found. In this case, the calculation gives:

uU = 0.637 m/s,

uV = 0.172 m/s and

uW = 0.112 m/s. If

uβ = 0 °,

uU = 0.63

7 m/s,

uV = 0.170 m/s and

uW = 0.112 m/s. The uncertainties on

U and

V are again very large and dominated by the compass uncertainty. They represent respectively 4

1 %, 3 % and 6 % of the measured value. To check their trueness, we just need to look at how

U,

V and

W vary when

α,

θ and

go respectively from 70 ° to 76 ° and from 5 ° to 5.8 °. The differences obtained by using the matrix (6) is

δU = 0.64 °,

δV = 0.16 ° and

δW = 0.13 ° which is very close of values found for

uU,

uV and

uW. All these results are resumed in

Table 3. This simulation demonstrates again the importance of correcting the compass and tilt sensors errors to make these uncertainties equivalent to the calibration uncertainties.

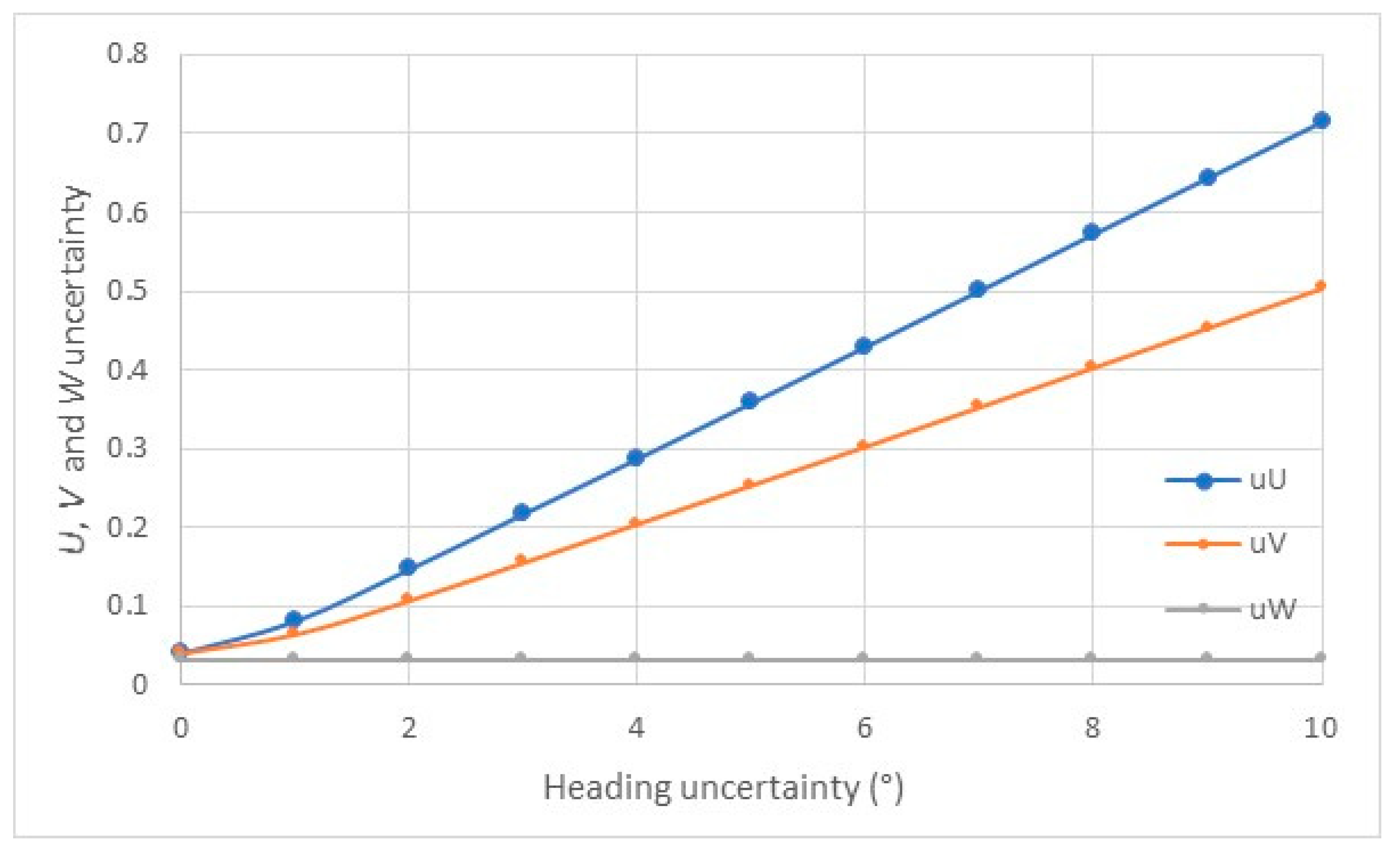

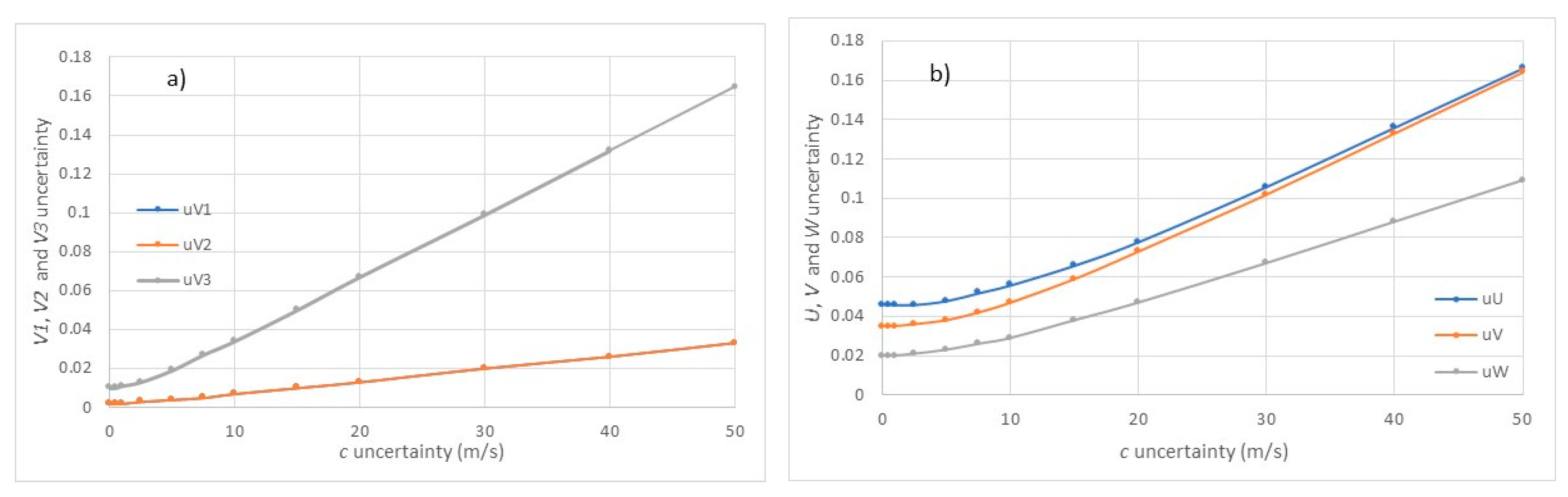

In order to illustrate the possibilities of simulation offered by this method, four graphs have been plotted (

Figure 4,

Figure 5 and

Figure 6). The first one (

Figure 4) shows the evolution of

U,

V and

W uncertainties when the uncertainty on the heading increases from 0 to 10 °, for the values used in

Table 1:

α = 70 ° and

θ = Ψ = 5 °, U = 2.87 m/s

, V = - 4.09 m/s

, W = - 0.85 m/s,

uθ = 0.21 °,

uΨ = 0.22 °. As expected,

uW remains constant and

uU and

uV increase linearly.

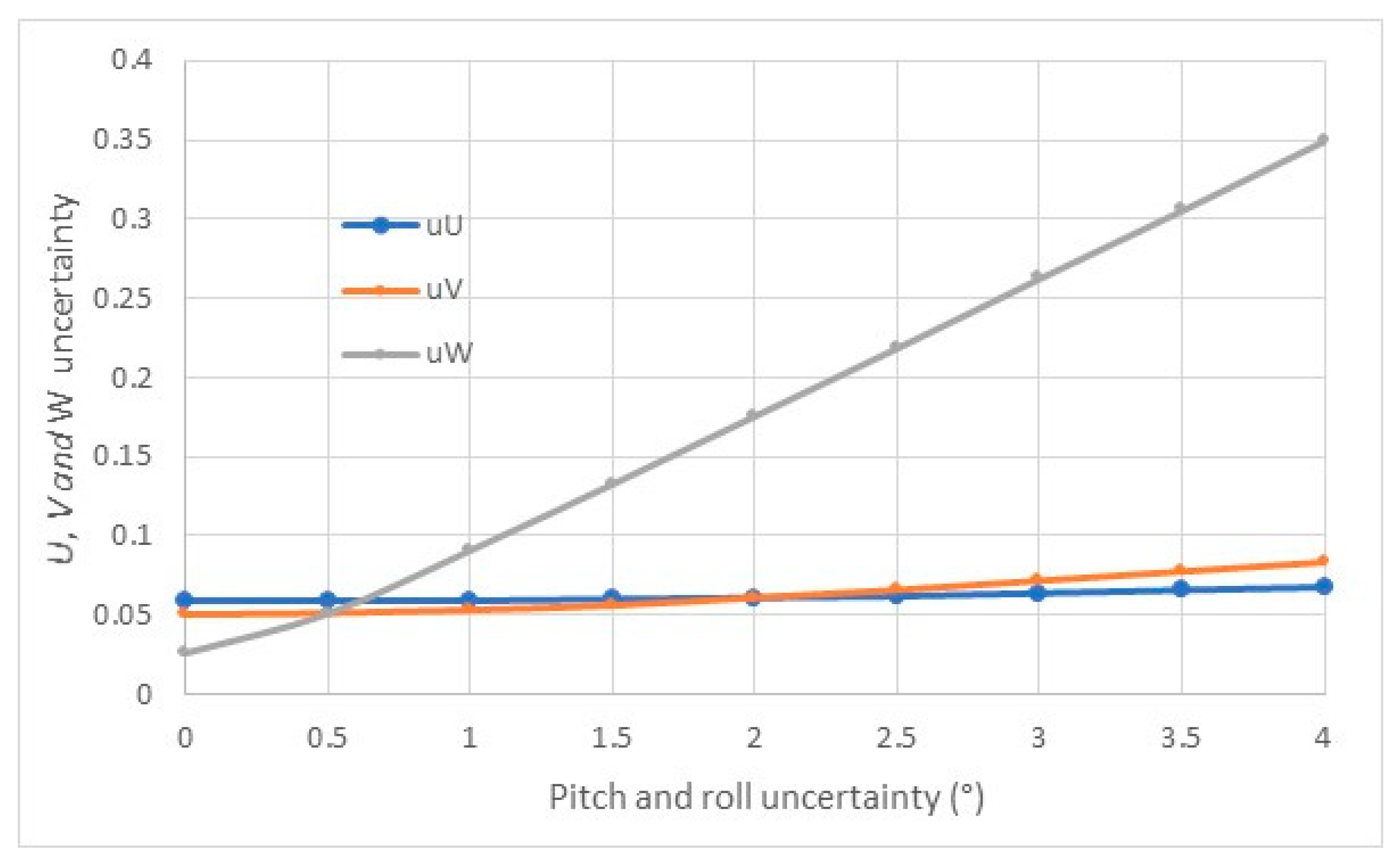

The second one, (

Figure 5) shows the evolution of

U,

V and

W uncertainties when the uncertainties on the roll and pitch measurements increase of the same value from 0 to 4 °, again for the values used in

Table 1:

α = 70 ° and

θ = Ψ = 5 °, U = 2.87 m/s

, V = - 4.09 m/s

, W = - 0.85 m/s,

uα= 0.59 °. As expected, the uncertainties on

U and

V evolve moderately and the uncertainty on

W increases linearly.

To quantify the effect of a large uncertainty on the speed of sound, we have plotted the evolution of the uncertainties in

V1,

V2 and

V3 (

Figure 6a) and the evolution of the uncertainties in

U,

V and

W, as a function of the uncertainty in

c (

Figure 6b). When the relative uncertainty

uVi/

Vi increases from 0.2 to 3.3 % as

uc increases from 0 to 50 m/s, the relative uncertainty

uU/

U increases from 1.2 % to 5.7 %, which corresponds to a 4.5 % increase, and

uW/

W increases from 2.3 % to 12.8 %, which corresponds to a 10.5 % increase.