Submitted:

13 June 2025

Posted:

17 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Industry Standard Approaches

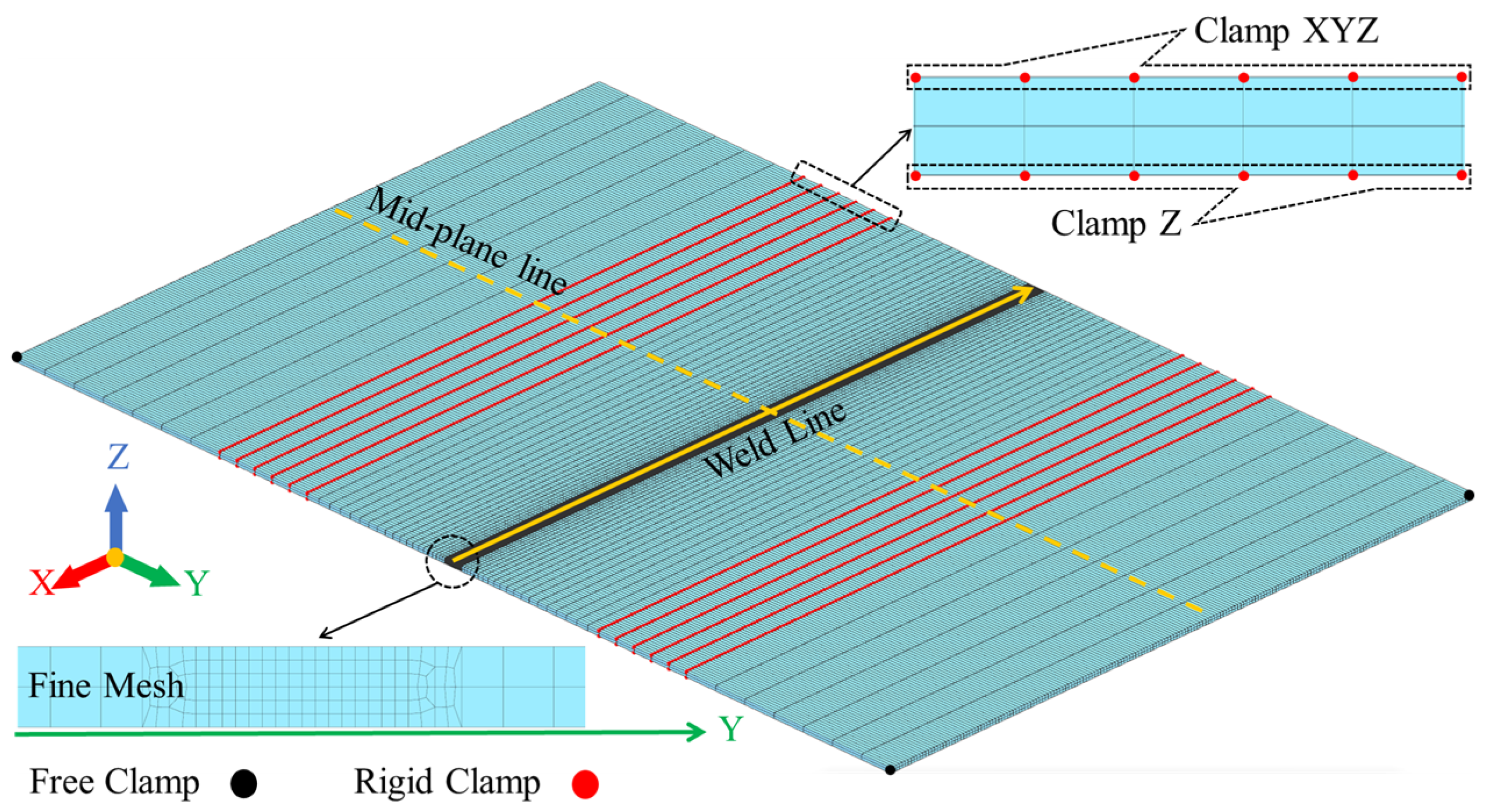

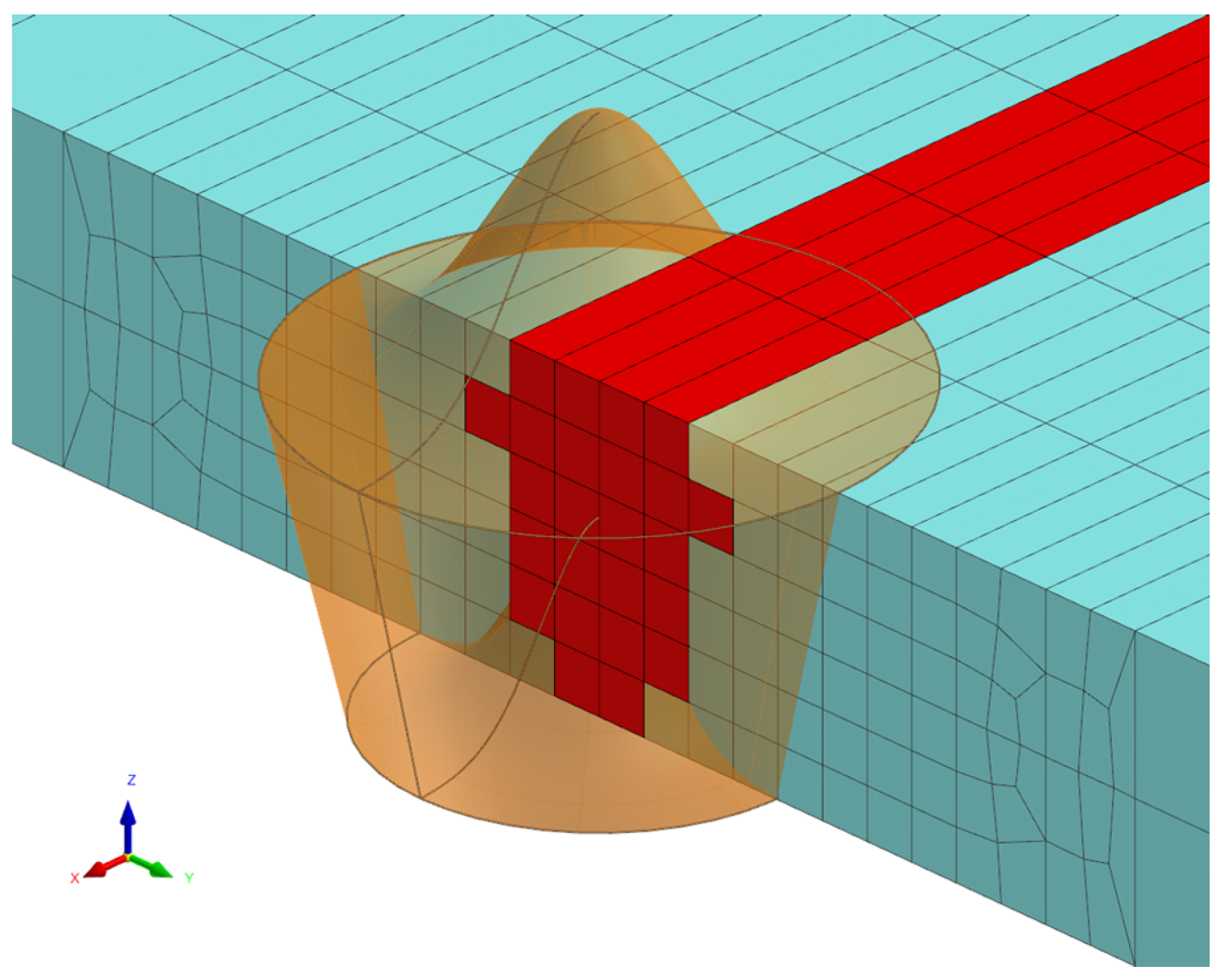

2.1. Numerical Model

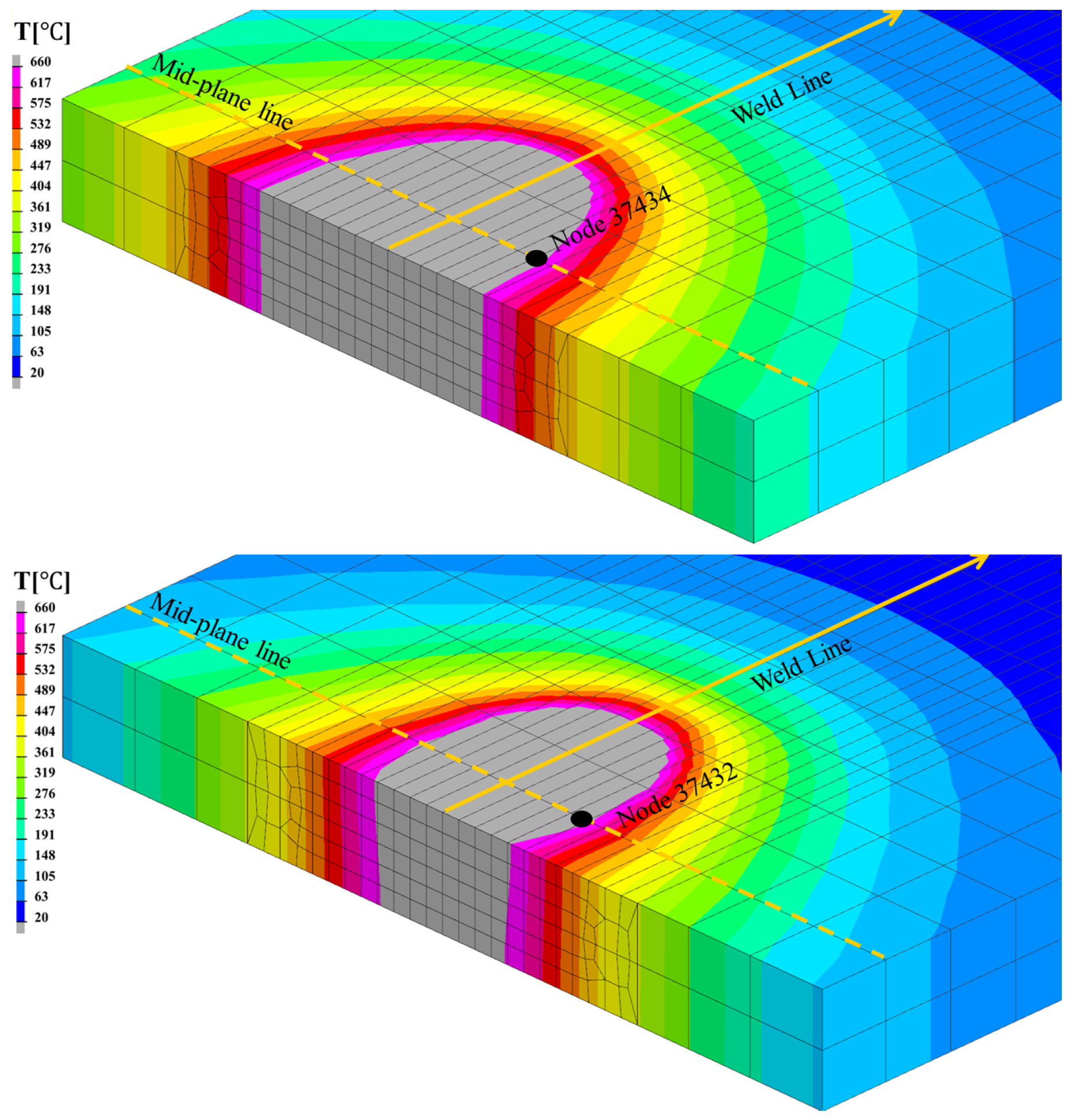

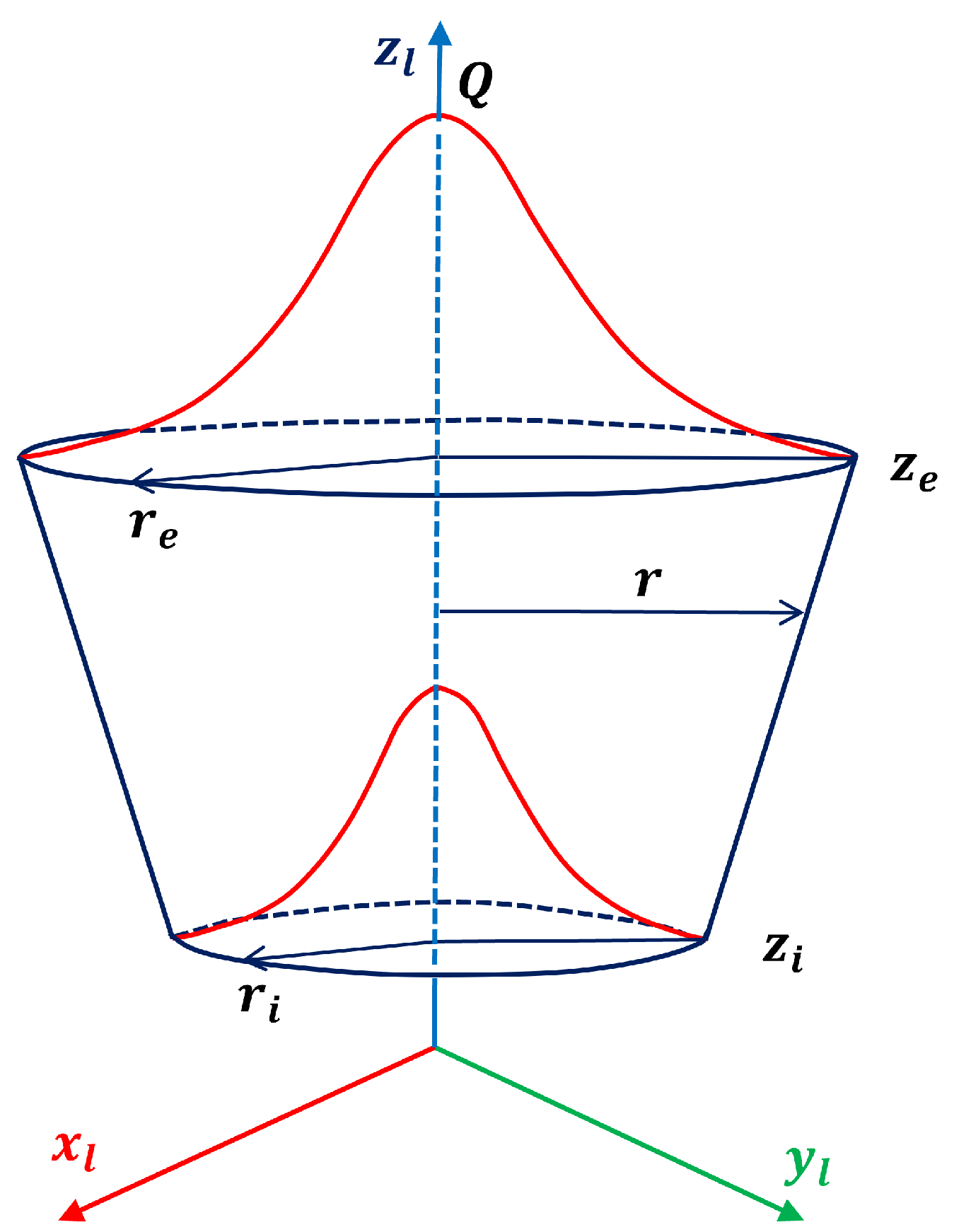

2.2. Iterative Calibration via Moving Heat Source

2.3. Imposed Thermal Cycle

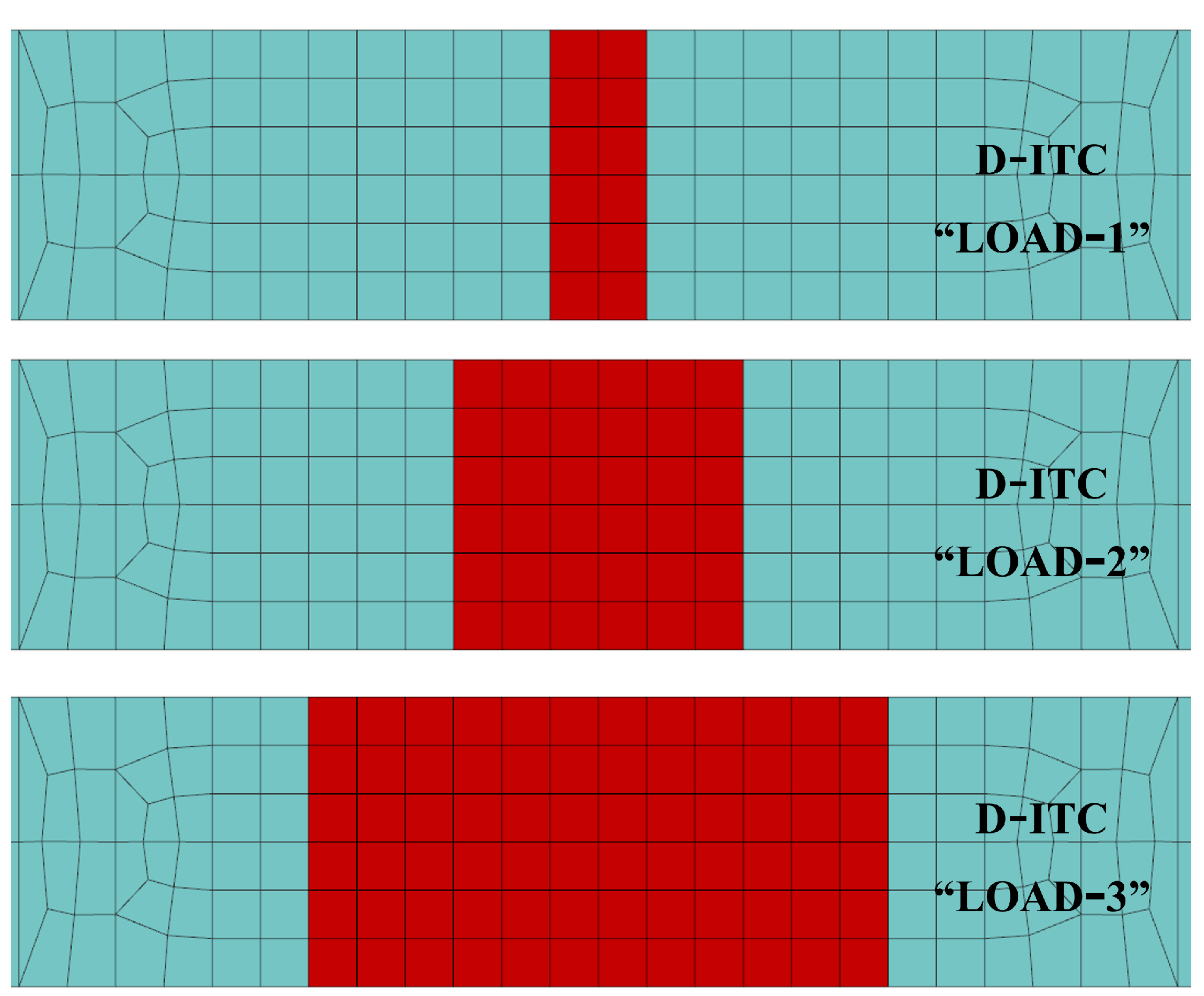

3. Direct Imposed Thermal Cycle Method

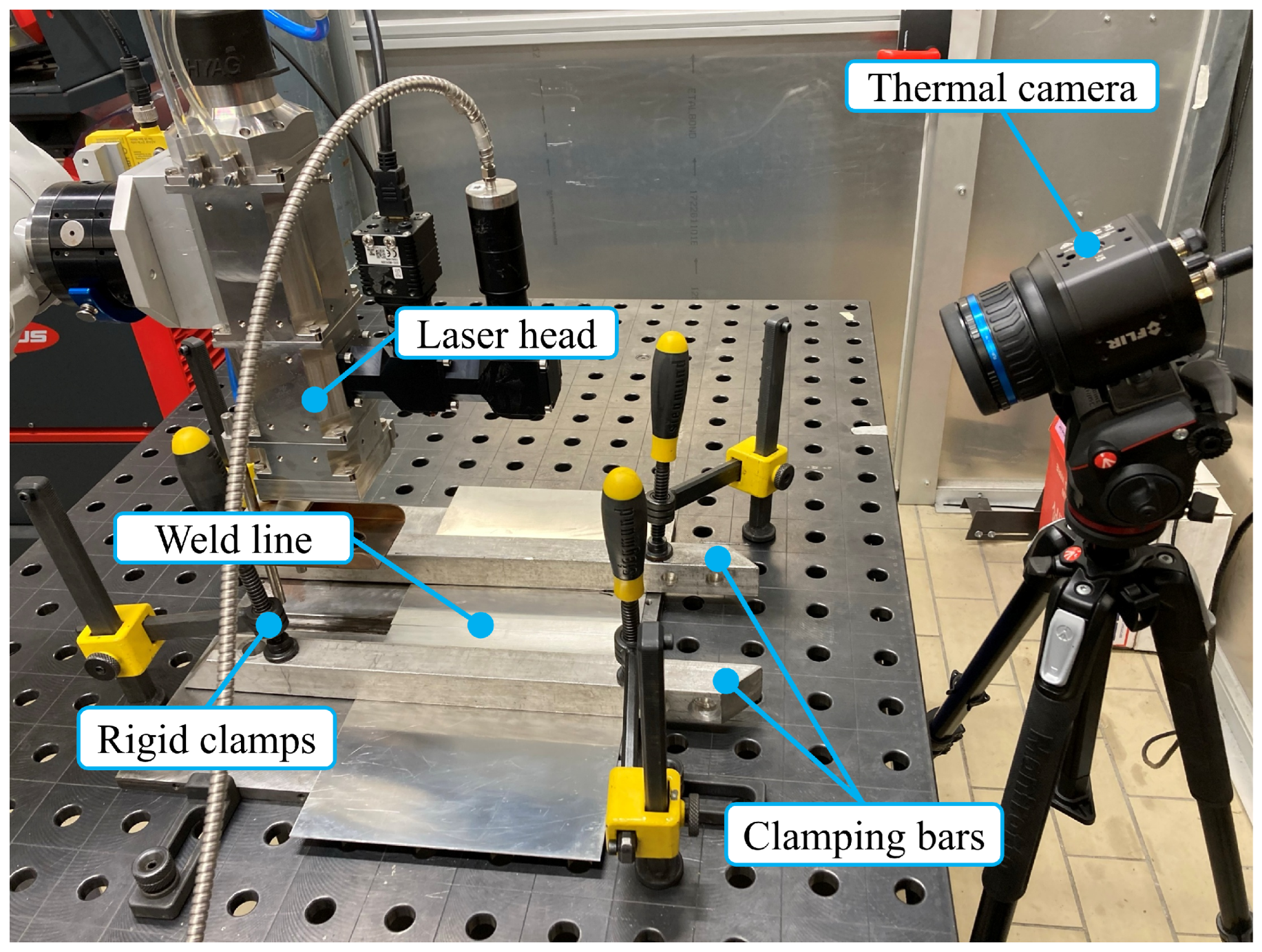

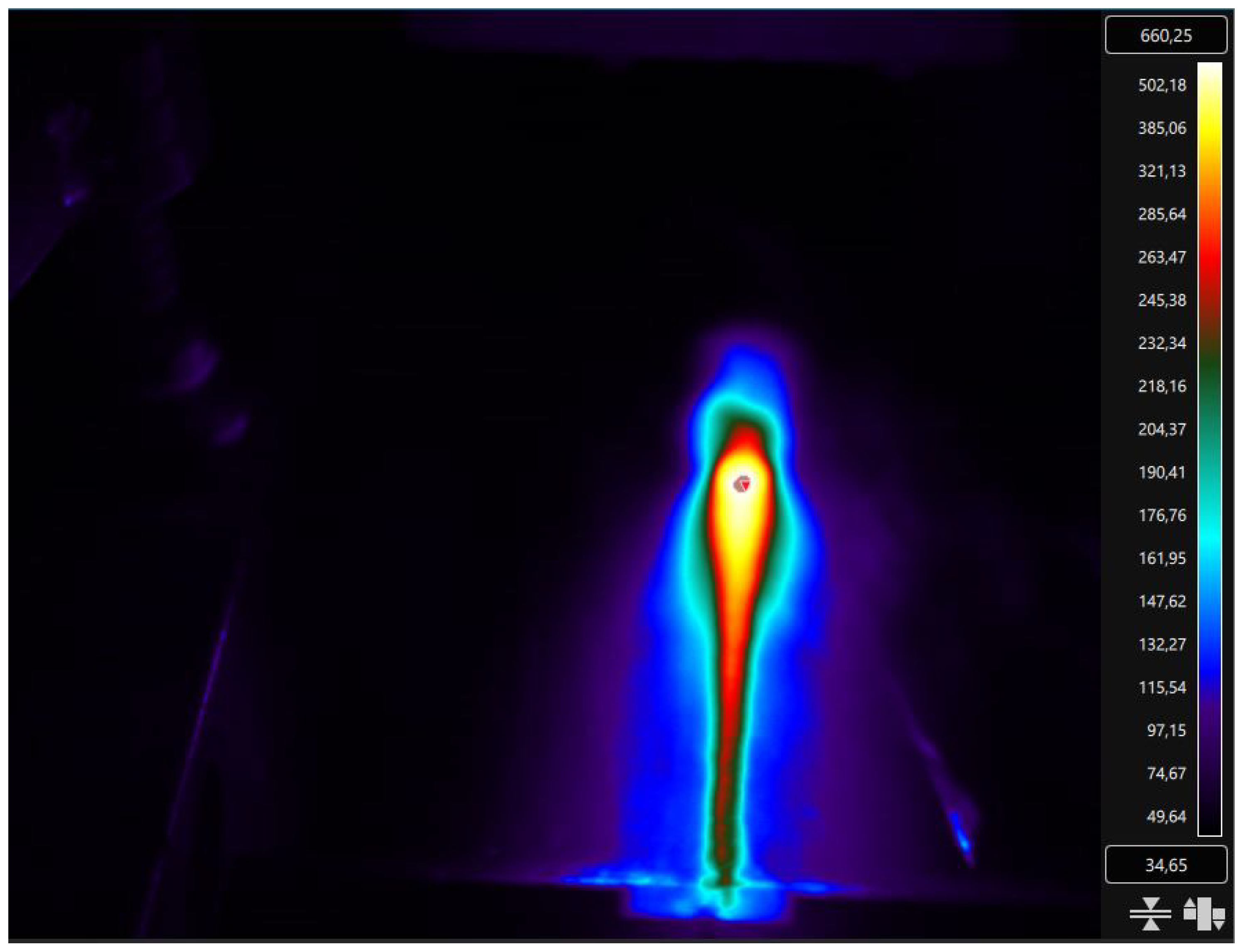

3.1. IR Camera Monitoring

4. Experimental Results

4.1. Materials and Experimental Methodology

4.2. Numerical Solver

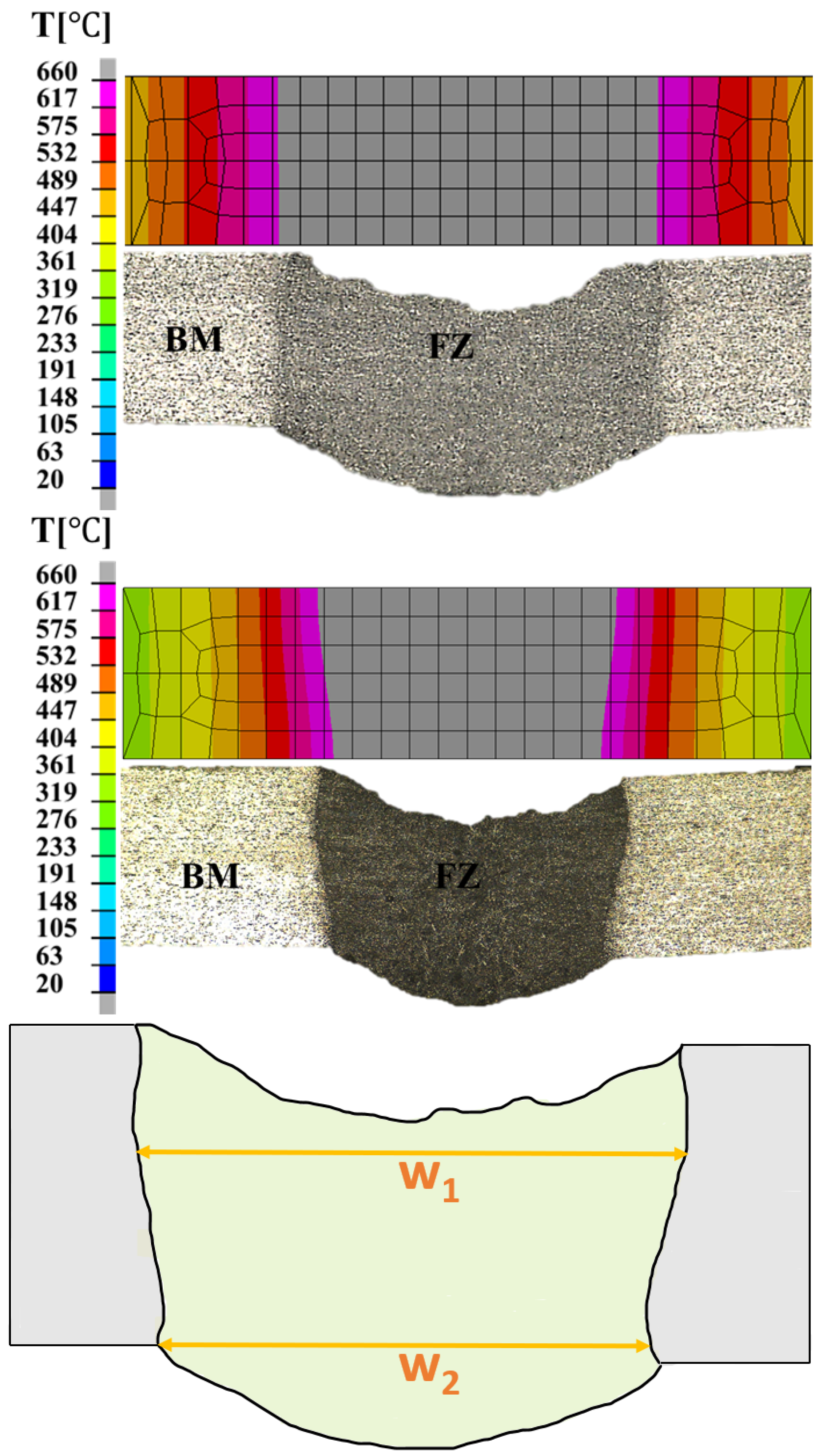

4.3. Cross-Section Comparison

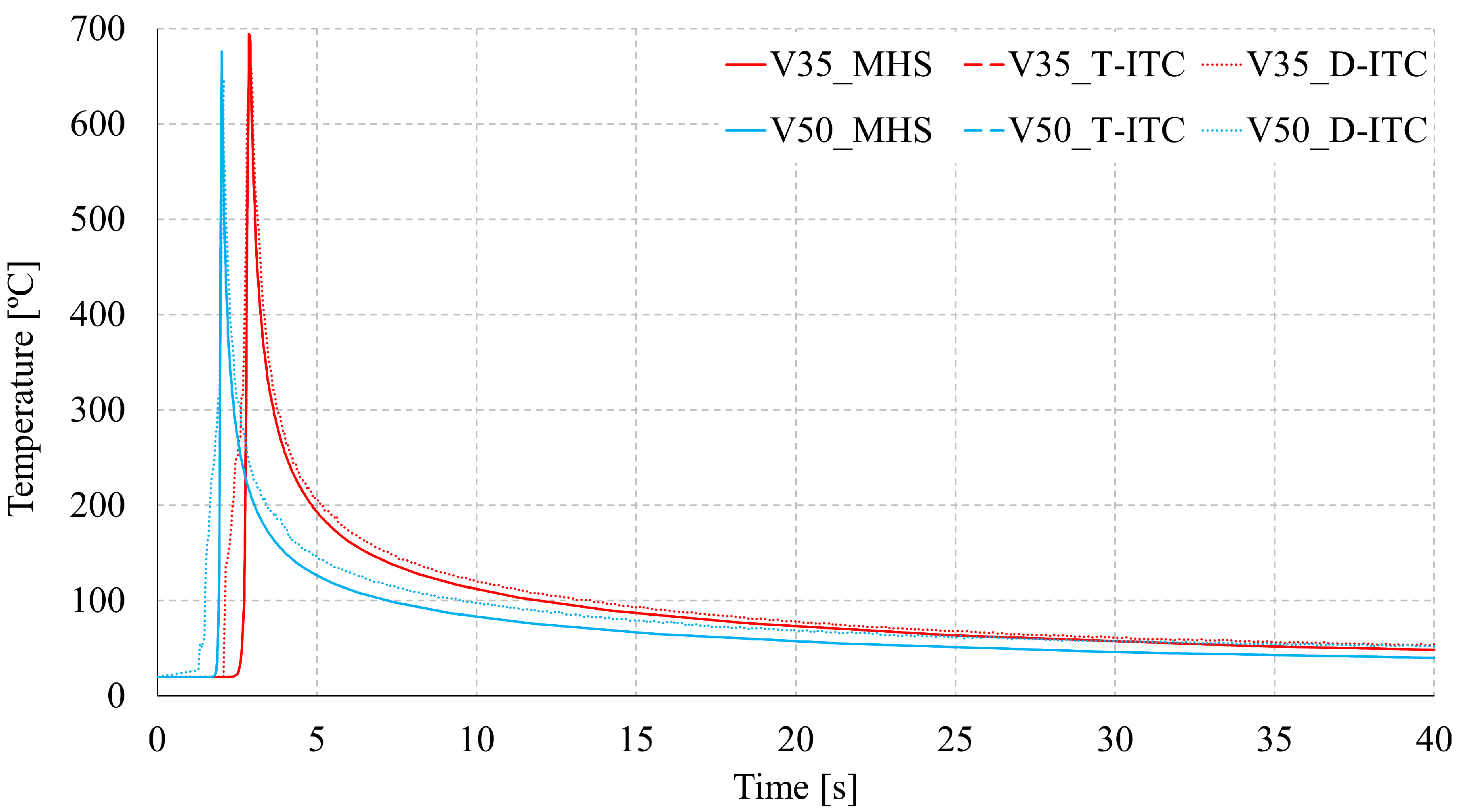

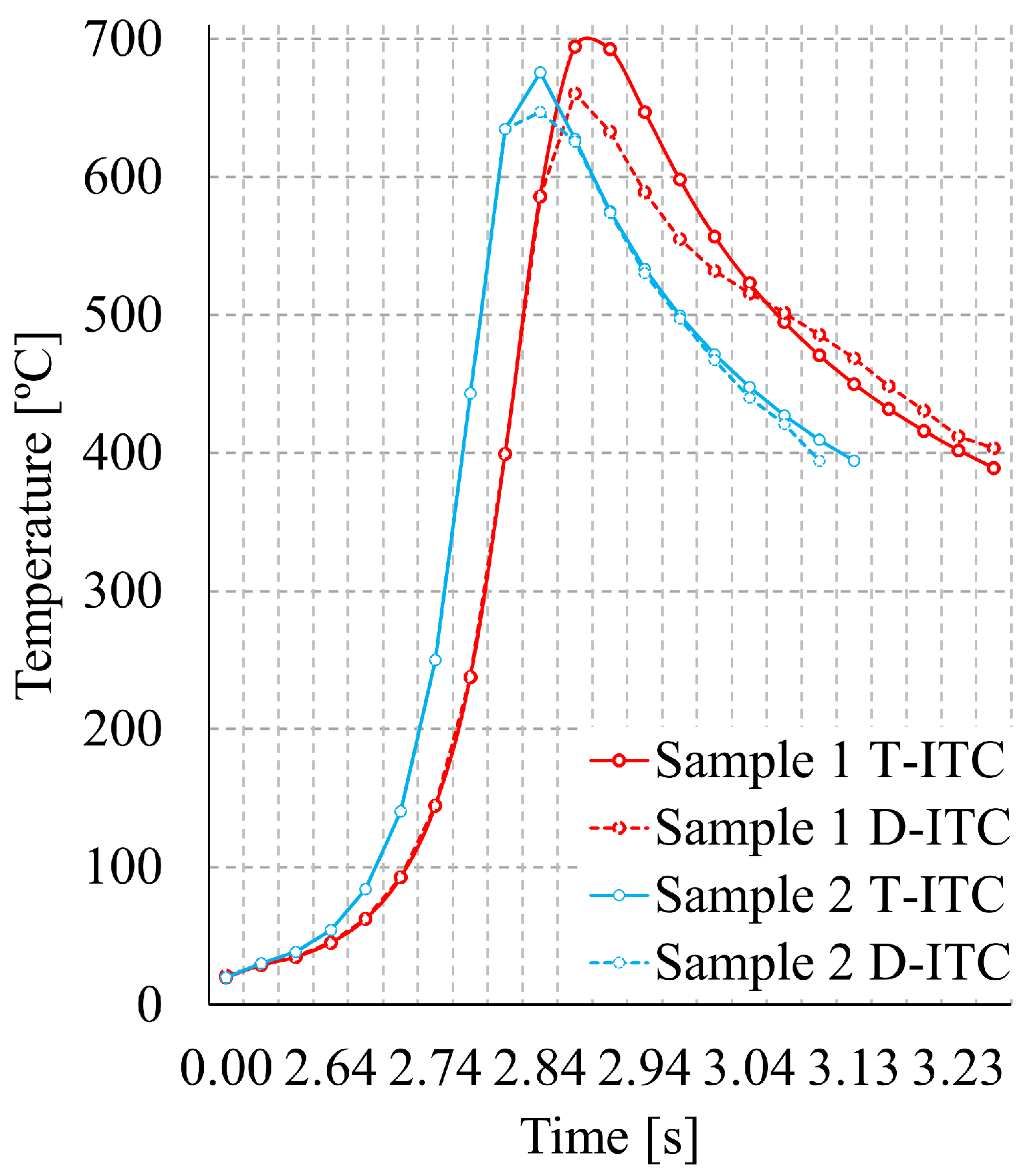

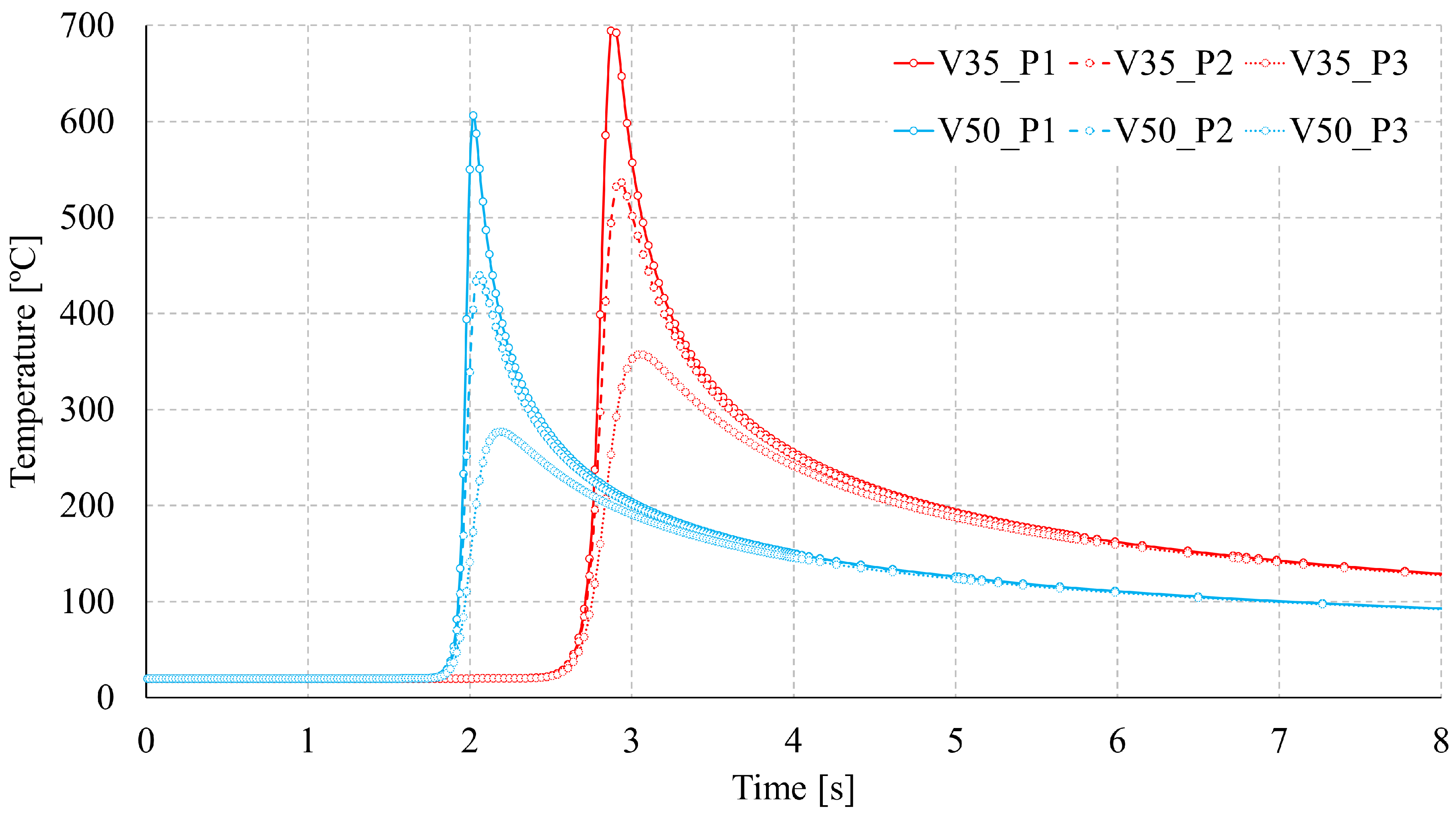

4.4. Thermal Analysis Results

| Sample | FEM (mm) | Experiment (mm) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| W1 | W2 | W1 | W2 | |||

| 1 | 3.22 | 3.18 | 3.20 | 3.20 | ||

| 2 | 2.65 | 2.30 | 2.64 | 2.29 | ||

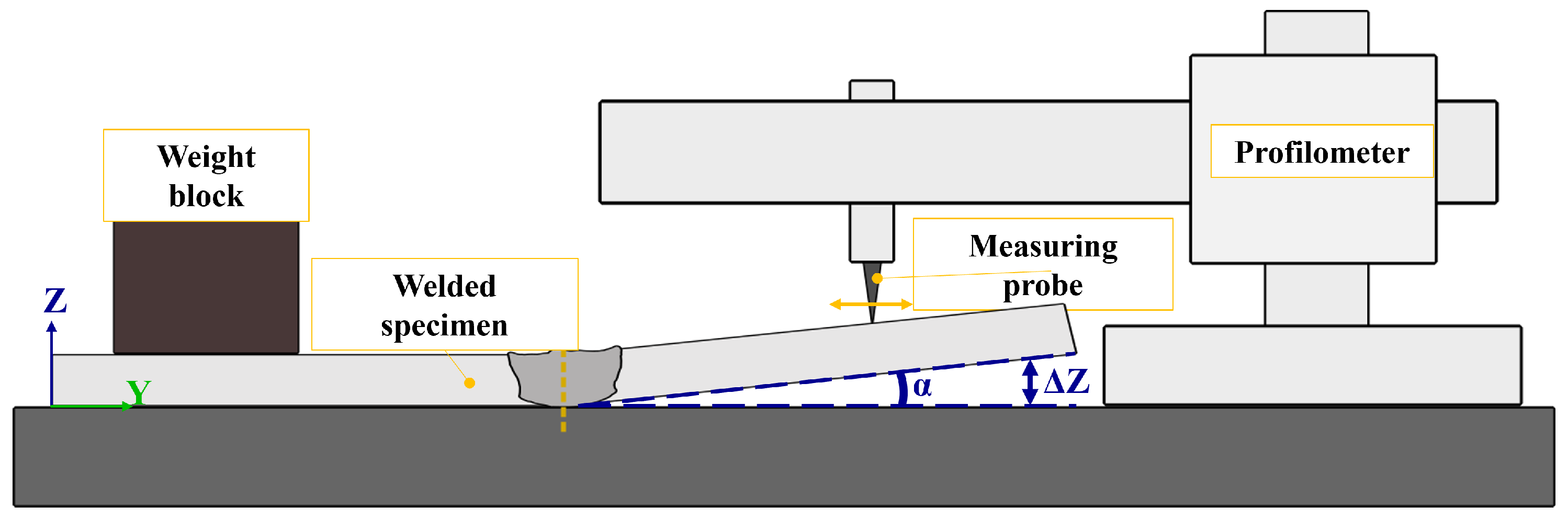

4.5. Mechanical Analysis Results

5. Conclusions

Declaration of Competing Interest

Data availability

Acknowledgments

References

- Zhang, W.; Xu, J. Advanced lightweight materials for Automobiles: A review. Materials & Design 2022, 221, 110994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basile, D.; Sesana, R.; De Maddis, M.; Borella, L.; Russo Spena, P. Investigation of Strength and Formability of 6016 Aluminum Tailor Welded Blanks. Metals 2022, 12, 1593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aminzadeh, A.; Silva Rivera, J.; Farhadipour, P.; Ghazi Jerniti, A.; Barka, N.; El Ouafi, A.; Mirakhorli, F.; Nadeau, F.; Gagné, M.O. Toward an intelligent aluminum laser welded blanks (ALWBs) factory based on industry 4.0; a critical review and novel smart model. Optics & Laser Technology 2023, 167, 109661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bunaziv, I.; Akselsen, O.M.; Ren, X.; Nyhus, B.; Eriksson, M. Laser Beam and Laser-Arc Hybrid Welding of Aluminium Alloys. Metals 2021, 11, 1150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stavridis, J.; Papacharalampopoulos, A.; Stavropoulos, P. Quality assessment in laser welding: a critical review. The International Journal of Advanced Manufacturing Technology 2018, 94, 1825–1847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Wang, Y.; Yin, X.; Zhang, Z. Laser welding simulation of large-scale assembly module of stainless steel side-wall. Heliyon 2023, 9, e13835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anca, A.; Cardona, A.; Risso, J.; Fachinotti, V.D. Finite element modeling of welding processes. Applied Mathematical Modelling 2011, 35, 688–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kik, T. Calibration of Heat Source Models in Numerical Simulations of Welding Processes. Metals 2024, 14, 1213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohan, A.; Franciosa, P.; Dai, D.; Ceglarek, D. A novel approach to control thermal induced buckling during laser welding of battery housing through a unilateral N-2-1 fixturing principle. Journal of Advanced Joining Processes 2024, 10, 100256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chuang, T.C.; Lo, Y.L.; Tran, H.C.; Tsai, Y.A.; Chen, C.Y.; Chiu, C.P. Optimization of Butt-joint laser welding parameters for elimination of angular distortion using High-fidelity simulations and Machine learning. Optics & Laser Technology 2023, 167, 109566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, H.; Zeng, X.; Cui, Y.; Zou, D. Numerical and experimental study of residual stress in multi-pass laser welded 5A06 alloy ultra-thick plate. Journal of Materials Research and Technology 2024, 28, 4116–4130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pyo, C.; Kim, J.; Kim, Y.; Kim, M. A study on a representative heat source model for simulating laser welding for liquid hydrogen storage containers. Marine Structures 2022, 86, 103260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murua, O.; Arrizubieta, J.; Lamikiz, A.; Schneider, H. Numerical simulation of a laser beam welding process: From a thermomechanical model to the experimental inspection and validation. Thermal Science and Engineering Progress 2024, 55, 102901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, T.; Bennett, C. An automated inverse method to calibrate thermal finite element models for numerical welding applications. Journal of Manufacturing Processes 2019, 47, 263–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Speka, M.; Matteï, S.; Pilloz, M.; Ilie, M. The infrared thermography control of the laser welding of amorphous polymers. NDT & E International 2008, 41, 178–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagavathiappan, S.; Lahiri, B.; Saravanan, T.; Philip, J.; Jayakumar, T. Infrared thermography for condition monitoring – A review. Infrared Physics & Technology 2013, 60, 35–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razza, V.; Santoro, L.; De Maddis, M. Gradient-based image generation for thermographic material inspection. Applied Thermal Engineering 2025, 268, 125900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santoro, L.; Sesana, R.; Molica Nardo, R.; Curá, F. Infrared in-line monitoring of flaws in steel welded joints: a preliminary approach with SMAW and GMAW processes. The International Journal of Advanced Manufacturing Technology 2023, 128, 2655–2670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santoro, L.; Razza, V.; De Maddis, M. Frequency-based analysis of active laser thermography for spot weld quality assessment. The International Journal of Advanced Manufacturing Technology 2024, 130, 3017–3029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santoro, L.; Razza, V.; De Maddis, M. Nugget and corona bond size measurement through active thermography and transfer learning model. The International Journal of Advanced Manufacturing Technology 2024, 133, 5883–5896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santoro, L.; Sesana, R. A pilot study using flying spot laser thermography and signal reconstruction. Optics and Lasers in Engineering 2025, 188, 108901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sesana, R.; Santoro, L.; Curà, F.; Molica Nardo, R.; Pagano, P. Assessing thermal properties of multipass weld beads using active thermography: microstructural variations and anisotropy analysis. The International Journal of Advanced Manufacturing Technology 2023, 128, 2525–2536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brüggemann, G.; Mahrle, A.; Benziger, T. Comparison of experimental determined and numerical simulated temperature fields for quality assurance at laser beam welding of steels and aluminium alloyings. NDT & E International 2000, 33, 453–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menaka, M.; Vasudevan, M.; Venkatraman, B.; Raj, B. Estimating bead width and depth of penetration during welding by infrared thermal imaging. Insight - Non-Destructive Testing and Condition Monitoring 2005, 47, 564–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hellinga, M.C.; Huissoon, J.P.; Kerr, H.W. Identifying weld pool dynamics for gas metal arc fillet welds. Science and Technology of Welding and Joining 1999, 4, 15–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasilev, M.; MacLeod, C.N.; Loukas, C.; Javadi, Y.; Vithanage, R.K.W.; Lines, D.; Mohseni, E.; Pierce, S.G.; Gachagan, A. Sensor-Enabled Multi-Robot System for Automated Welding and In-Process Ultrasonic NDE. Sensors 2021, 21, 5077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, H.L.; Van Nguyen, A.; Duy, H.L.; Nguyen, T.H.; Tashiro, S.; Tanaka, M. Relationship among Welding Defects with Convection and Material Flow Dynamic Considering Principal Forces in Plasma Arc Welding. Metals 2021, 11, 1444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, C.; Cheon, J.; Tang, X.; Na, S.J.; Cui, H. Molten pool behaviors and their influences on welding defects in narrow gap GMAW of 5083 Al-alloy. International Journal of Heat and Mass Transfer 2018, 126, 1206–1221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filyakov, A.E.; Sholokhov, M.A.; Poloskov, S.I.; Melnikov, A.Y. The study of the influence of deviations of the arc energy parameters on the defects formation during automatic welding of pipelines. In Proceedings of the IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering, 2020, Vol. 966. [CrossRef]

- Aucott, L.; Huang, D.; Dong, H.B.; Wen, S.W.; Marsden, J.A.; Rack, A.; Cocks, A.C.F. Initiation and growth kinetics of solidification cracking during welding of steel. Scientific Reports 2017, 7, 40255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, Y.; Yang, M.; Chang, B.; Du, D. Filter-PCA-Based Process Monitoring and Defect Identification During Climbing Helium Arc Welding Process Using DE-SVM. IEEE Transactions on Industrial Electronics 2023, 70, 7353–7362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Accardi, E.; Chiappini, F.; Giannasi, A.; Guerrini, M.; Maggiani, G.; Palumbo, D.; Galietti, U. Online monitoring of direct laser metal deposition process by means of infrared thermography. Progress in Additive Manufacturing 2024, 9, 983–1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Li, X.; Gao, M. Effects of circular oscillating beam on heat transfer and melt flow of laser melting pool. Journal of Materials Research and Technology 2020, 9, 9271–9282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Q.; Rong, Y.; Shao, X.; Jiang, P.; Gao, Z.; Cao, L. Optimization of laser brazing onto galvanized steel based on ensemble of metamodels. Journal of Intelligent Manufacturing 2018, 29, 1417–1431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirapeix, J.; García-Allende, P.; Cobo, A.; Conde, O.; López-Higuera, J. Real-time arc-welding defect detection and classification with principal component analysis and artificial neural networks. NDT & E International 2007, 40, 315–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Chen, Z.; Zhang, C.; Xi, J.; Le, X. Weld Defect Detection Based on Deep Learning Method. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE 15th International Conference on Automation Science and Engineering (CASE); 2019; pp. 1574–1579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkar, S.S.; Das, A.; Paul, S.; Mali, K.; Ghosh, A.; Sarkar, R.; Kumar, A. Machine learning method to predict and analyse transient temperature in submerged arc welding. Measurement 2021, 170, 108713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergman, T.L.; Lavine, A.S.; Incropera, F.P.; DeWitt, D.P. Fundamentals of Heat and Mass Transfer, 8th Edition; John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 2018.

- Kik, T. Computational Techniques in Numerical Simulations of Arc and Laser Welding Processes. Materials 2020, 13, 608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unni, A.K.; Vasudevan, M. Computational fluid dynamics simulation of hybrid laser-MIG welding of 316 LN stainless steel using hybrid heat source. International Journal of Thermal Sciences 2023, 185, 108042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vargas, J.A.; Torres, J.E.; Pacheco, J.A.; Hernandez, R.J. Analysis of heat input effect on the mechanical properties of Al-6061-T6 alloy weld joints. Materials & Design (1980-2015) 2013, 52, 556–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marques, E.S.V.; Silva, F.J.G.; Pereira, A.B. Comparison of Finite Element Methods in Fusion Welding Processes—A Review. Metals 2020, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, H.; Gery, D.; Carlier, A.; Maropoulos, P. Prediction of welding distortion in butt joint of thin plates. Materials & Design 2009, 30, 4126–4135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinoth, A.; Sivasankari, R. Numerical Simulation Studies in Tungsten Inert Gas Welding of Inconel 718 Alloy Sheet. Journal of Materials Engineering and Performance 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kožar, I.; Rukavina, T.; Ibrahimbegović, A. Method of Incompatible Modes – Overview and Application. GRAĐEVINAR 2018, 70, 19–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

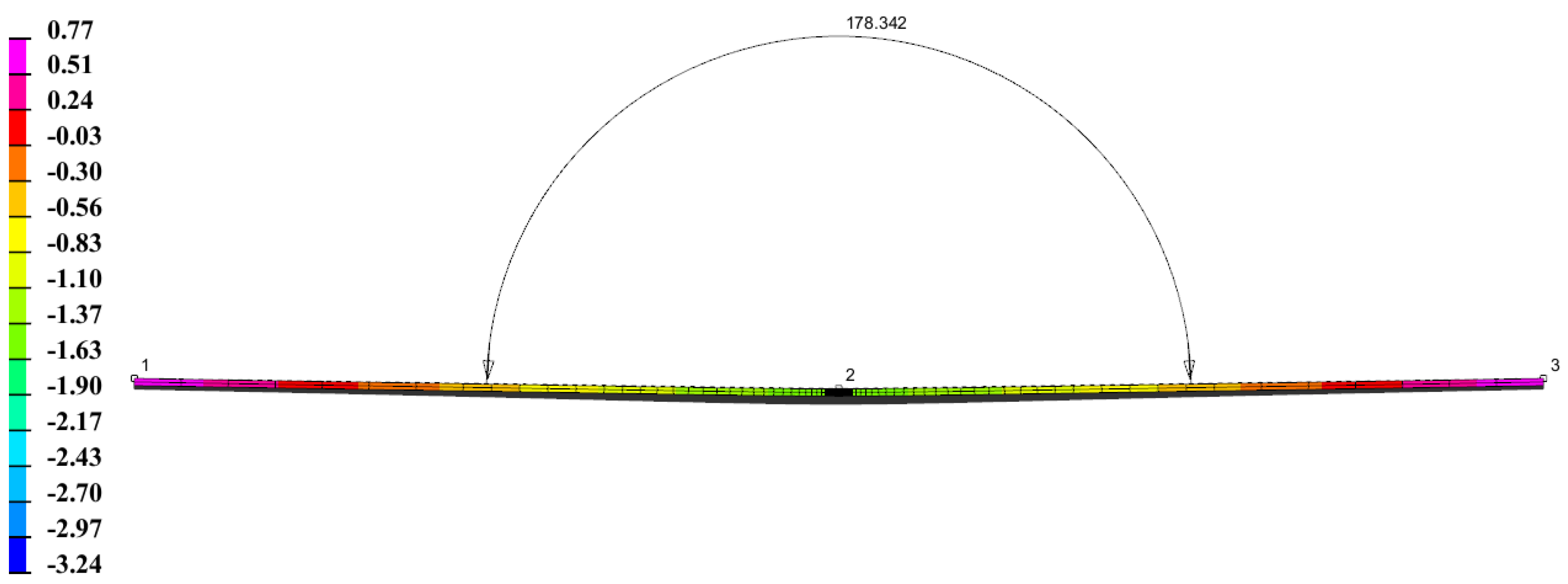

| Sample | Model | Angle (°) | Error (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | MHS | 177.98 | 0.15 |

| T-ITC | 177.97 | 0.15 | |

| D-ITC | 177.92 | 0.18 | |

| Experiment | 178.24 | ||

| 2 | MHS | 178.43 | 0.22 |

| T-ITC | 178.37 | 0.25 | |

| D-ITC | 178.34 | 0.27 | |

| Experiment | 178.82 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).