1. Introduction

Forest ecosystems cover about 30% of the Earth’s land surface and store more than 80% of the terrestrial carbon, contributing to the stabilisation of ecological processes on a global scale (Bonan, 2008; Friedlingstein et al., 2019; Xu et al., 2024). However, tree mortality and forest dieback have increased over the last decades (Hansen et al., 2013; Berner et al., 2017). Forest wildfires are among the most important factors of these severe impacts (Hicke et al., 2015; Zhao et al., 2023; Webb et al., 2024). As a result, wildfire events with high severity reshape the global distribution of forests and alter the carbon stock dynamics on a global scale (Hicke et al., 2012; Hicke et al., 2013; Earles et al., 2014).

Increased incidence of forest fires, especially when at extreme severity (Abatzoglou et al., 2019), poses serious threats to the structure and functioning of forest ecosystems. This reduces forest biodiversity and productivity as well as leads to large carbon emissions and severe hydrological impacts in the burned forests (Phillips et al., 2022; Jones et al., 2024; Xu et al., 2024). Generally, the time for forest recovery after a severe wildfire is long. As a consequence, their capacity to play the common ecosystem functions (e.g., carbon storage) is lost for a long time (Yue et al., 2016; Lindenmayer and Taylor, 2020). Moreover, extreme drought events driven by global change trends trigger forest wildfires with high severity and impacts (Field et al., 2016; van Oldenborgh et al., 2021; Jain et al., 2022; Zheng et al., 2023). Recurring and highly-impacting wildfires may be precursors to changing fire conditions on a global scale (Li et al., 2023). Annually, the total burned area affected by forest fires worldwide is approximately 67×106 ha (van Lierop et al., 2015). For example, in Australia between 2019 and 2020, the area burned by fire was more than double compared to the historical record since 1930. In this environment, carbon emissions due to fire were the highest since 2003 (Canadell et al., 2021; van der Velde et al., 2021). In South America, fire emissions increase about 1.5 to 2.8 times during seasons of severe drought compared to other years (Ye et al., 2022). Boreal forests of North America, dominated by coniferous forests, are one of the most important Earth’s biomes, accounting for about 30% of the total area of forests in the World. Therefore, this large extent of boreal forests plays a significant role in regulating the global carbon cycle (Mack et al., 2021; Xi et al., 2024). And in this environment of the Northern Hemisphere, wildfires have severely affected the structure and functioning of forest ecosystems (Lenton et al., 2008; Tamarin-Brodsky et al., 2020; Zheng et al., 2023). A recent study has shown that carbon emissions from boreal fires reached the highest value since 2000, specifically due to the increasing occurrence and severity of wildfires. Forest fires in boreal biomes release about 10 to 20 times more carbon per unit burned area compared to other forest ecosystems (Zheng et al., 2023). However, the wildfire effects in boreal forests have attracted less attention compared to tropical forests, and there is scarce research focusing on fire-related mortality in boreal forests (Sánchez-Pinillos et al., 2022; Xi et al., 2024). Studies about the spatio-temporal dynamics and occurrence of wildfires in boreal forests affected by wildfires are essential to understanding forest dynamics and carbon-climate relationships. The latter gives forest managers feedback for predicting ecosystem’s resilience to climate change and insights for developing more effective management strategies. In other words, there is a need to identify, also by a low-resolution study, which fire-affected areas are able to more rapidly recover after fire disturbance (Lindenmayer and Taylor, 2020). This knowledge may also improve our ability to introduce fire-induced forest mortality into process-based ecosystem models (Trumbore et al., 2015; Hood et al., 2018).

To fill this gap, this study assesses the spatio-temporal patterns of wildfire-induced mortality of boreal forests together with its potential drivers in Canada and Alaska. The specific objectives of this study are: (i) to evaluate the forest areas burned in the region over the period 2003-2020; (ii) to quantify tree mortality in the same period and area; and (iii) to identify the potential factors determining forest mortality among key wildfire attributes, including size, duration and burned area.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Collection

2.1.1. Burned Area and Fire Regime

Data about the extent of burned area between 2003 and 2020 were acquired from the Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS) Aqua and Terra MCD64A1 with 500-meter resolution. This coarse resolution was deliberately chosen to avoid excessive computational effort for this large-scale study.

Individual fire events for the same period (2003 to 2020) were extracted from the Global Fire Atlas (GFA) database. This database was built at a daily and 500-meter spatial resolution using geographical data from MODIS Collection 6 MCD64A1 (Giglio et al., 2018; Abatzoglou et al., 2019). The quality of information in this database regarding fire regime (size, duration, and spread rate) was verified in previous studies (Abatzoglou et al., 2019).

2.1.2. Forest Mortality

Forest mortality at the annual scale (2003 to 2022) in the Global Forest Change (GFC) was extracted from Landsat satellite data at 30-meter resolution (version 1.7) (Hansen et al., 2013). This data was used to calculate the forest area in 2000 (AreaForest).

Due to the different resolution compared to data of burned area, the pixels at 30-meter resolution annual were upscaled to a 500-meter sinusoidal grid. Finally, the data of forest mortality was expressed as the percentage of area with forest loss at the largest resolution (AreaForestLoss).

2.1.3. Land Cover and Forest Types

Forest areas and types for each year were identified using the land cover map prepared by the European Space Agency’s (ESA) (300-meter resolution, period 2002 to 2019) within the Climate Change Initiative (CCI) (period 2002-2019). In more detail, all land cover types labeled as “tree cover” were considered as forests. The forest types were classified as follows: evergreen coniferous forest (ENF), deciduous coniferous forest (DNF), evergreen broadleaf forest (corrected to EBF for discrimination with from ENF), deciduous broadleaf forest (DBF), and mixed forest (i.e., a mixture of broadleaf and coniferous forest types). The forest type was identified from the map updated to the year preceding the fire event (

Table 1).

2.2. Data analysis

2.2.1. Identification and Calculation of the Burned Area

The pixels related to burned area were matched to those related to fire over time if both of the following two conditions occurred: i) the center of the forest area pixel was located inside the burned area; and ii) the date of forest area was between the start and end dates of the fire.

2.2.2. Calculation of Forest Mortality Due to Wildfire

In this study, according to (Zhao et al., 2023), “forest mortality” (M) in a given period is defined as the ratio of the area of forest loss by the total area. The values of forest mortality (‘M

t’) for a given year ‘t’ were calculated for pairs of two consecutive years (i.e., ‘t’ to ‘t+2’) after the fire year (‘t’) (Liu et al., 2019).

where

is the total area (in 2000) and

,

, and

are the areas of forest loss at the years ‘t’, ‘t+1’ and ‘t+2’.

2.2.3. Spatial-Temporal Patterns of Burned Area and Forest Mortality

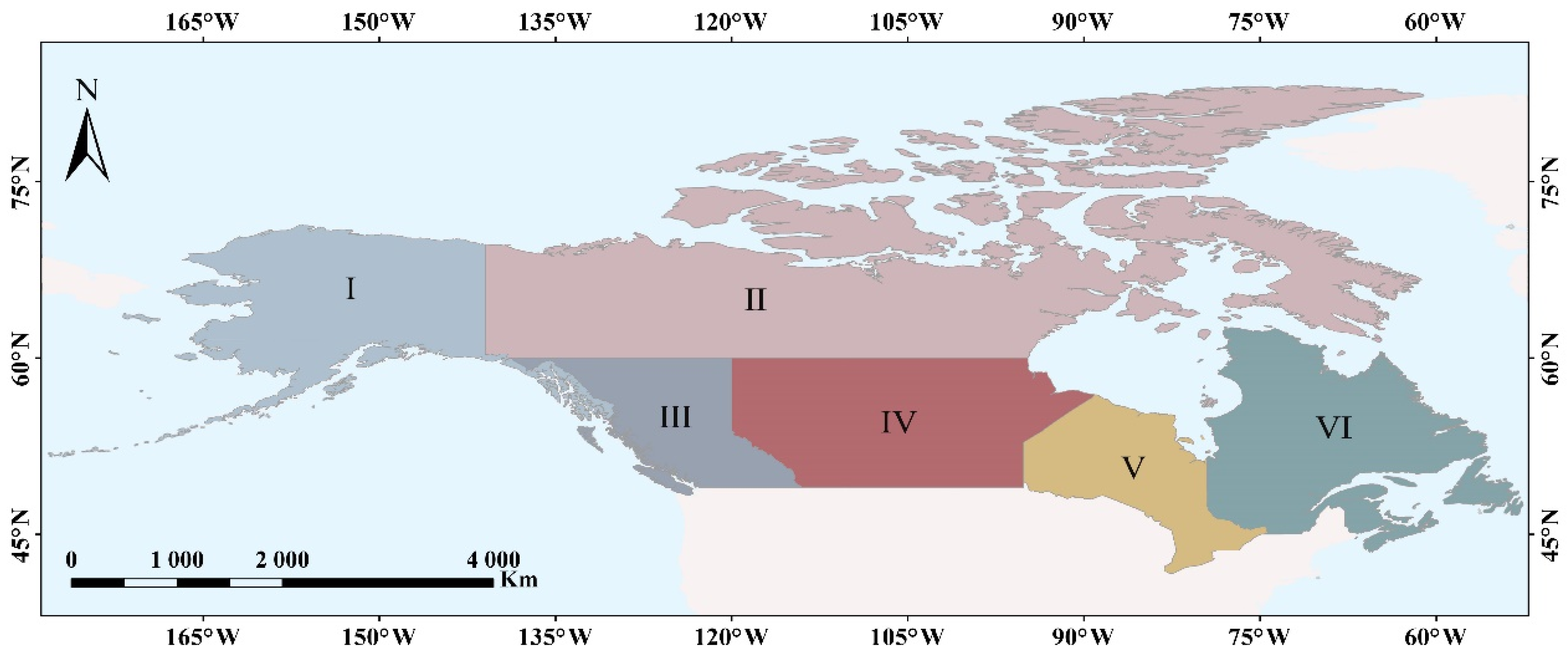

The data of burned area forest mortality due to wildfire was compared in the temporal (annual and monthly scales, between 2003 and 2020 and spatial (0.5°× 0.5° grid cell) domains to explore the spatial and temporal patterns. The spatial domain was classified into the following regions of Alaska and Canada: I) Alaska; II) Northern Canada; III) Western Canada; IV) Central Canada; V) Ontario, Canada; and VI) Eastern Canada (

Figure 1).

2.2.4. Statistical Processing

Pearson analysis was applied to identify correlations (expressed as correlation coefficient ‘r’) between forest mortality, fire characteristics and burned area. The ‘r’ coefficients were calculated by generalized linear models (GLM) using the “glm” function in the “stats” package of the R software.

3. Results

3.1. Spatio-Temporal Patterns of Burned Area

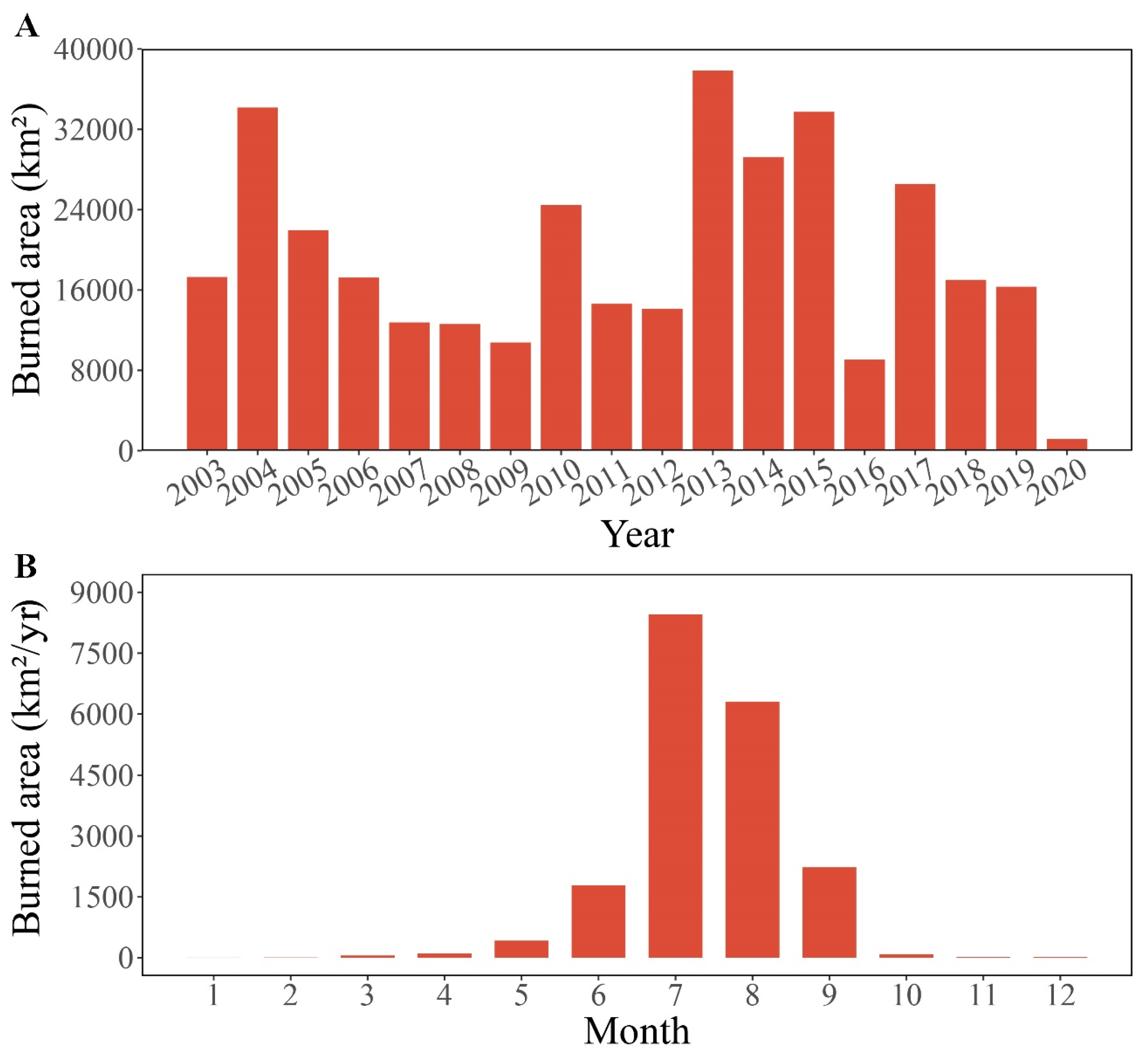

The average burned area of North American boreal forests was 19501 km

2/yr (2003-2020). This area always exceeded 8000 km

2/yr, except in 2000 (1160 km

2/yr), with a peak of 37870 km

2/yr in 2013 (

Figure 2A). The evolutionary trend of the burned area over time shows a high seasonality, since the highest extent (about 98% of the total burned area) is concentrated in summer and early autumn (

Figure 2B).

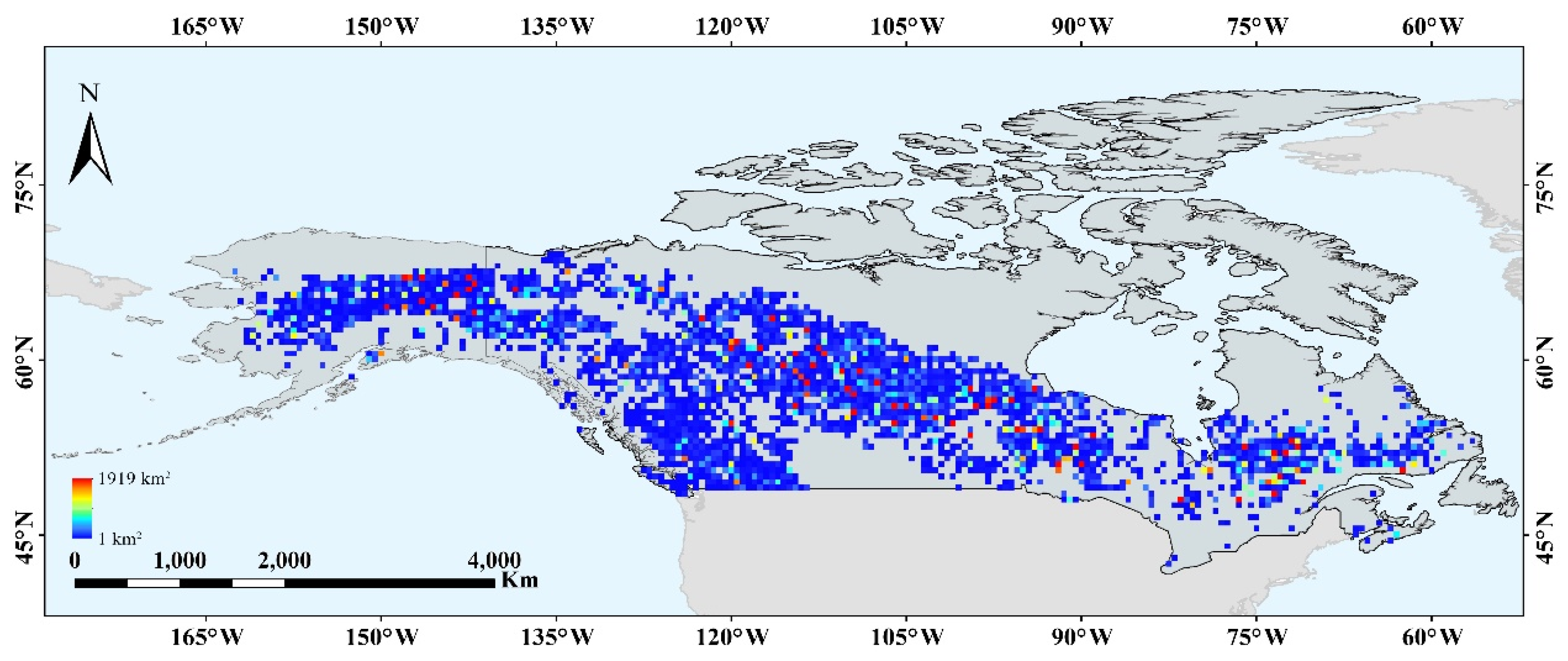

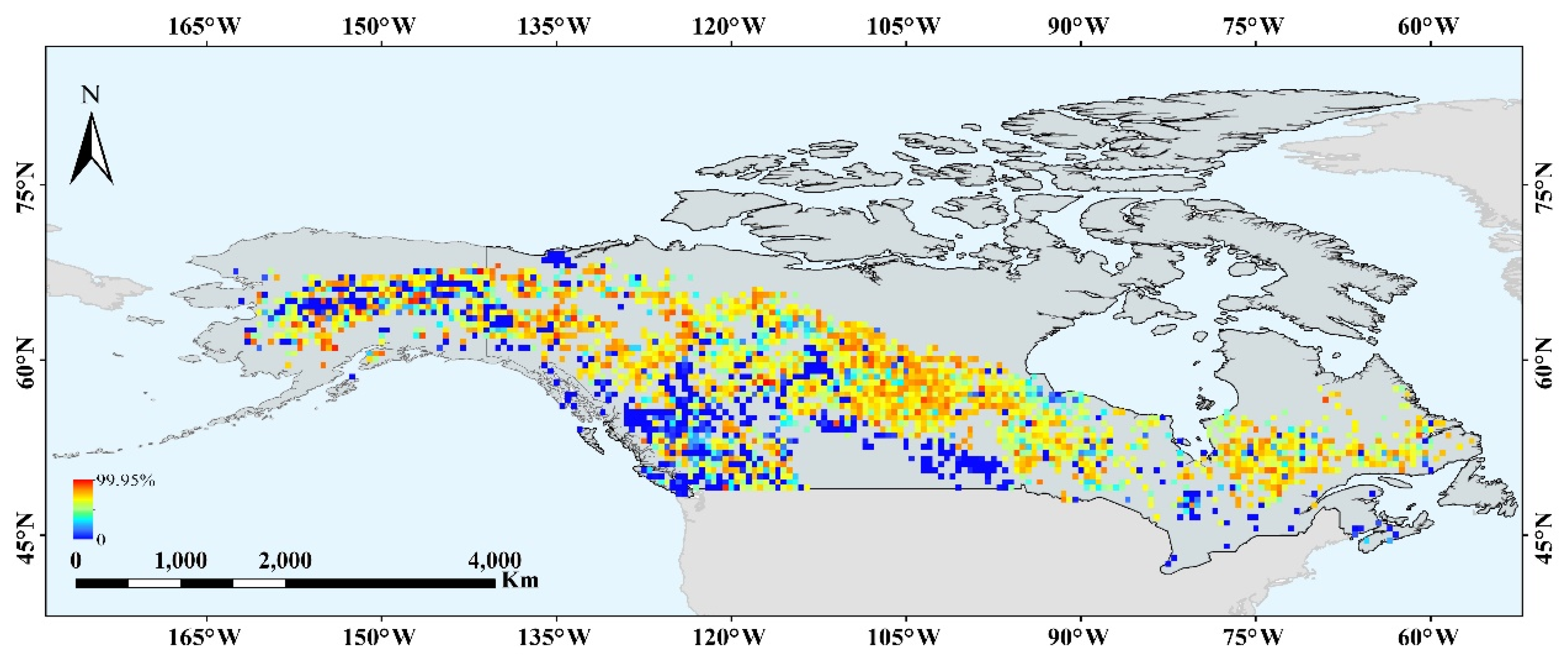

The spatial distribution of forest fires in the region is uneven, mainly occurring in Central, Northern, and Eastern Canada (regions II, III and IV), and Alaska, all being dominated by a forest cover (

Figure 3). Central Canada alone accounted for 39% of the burned area in the study area, while Ontario showed the lowest percentage (4.5%) (

Table 2).

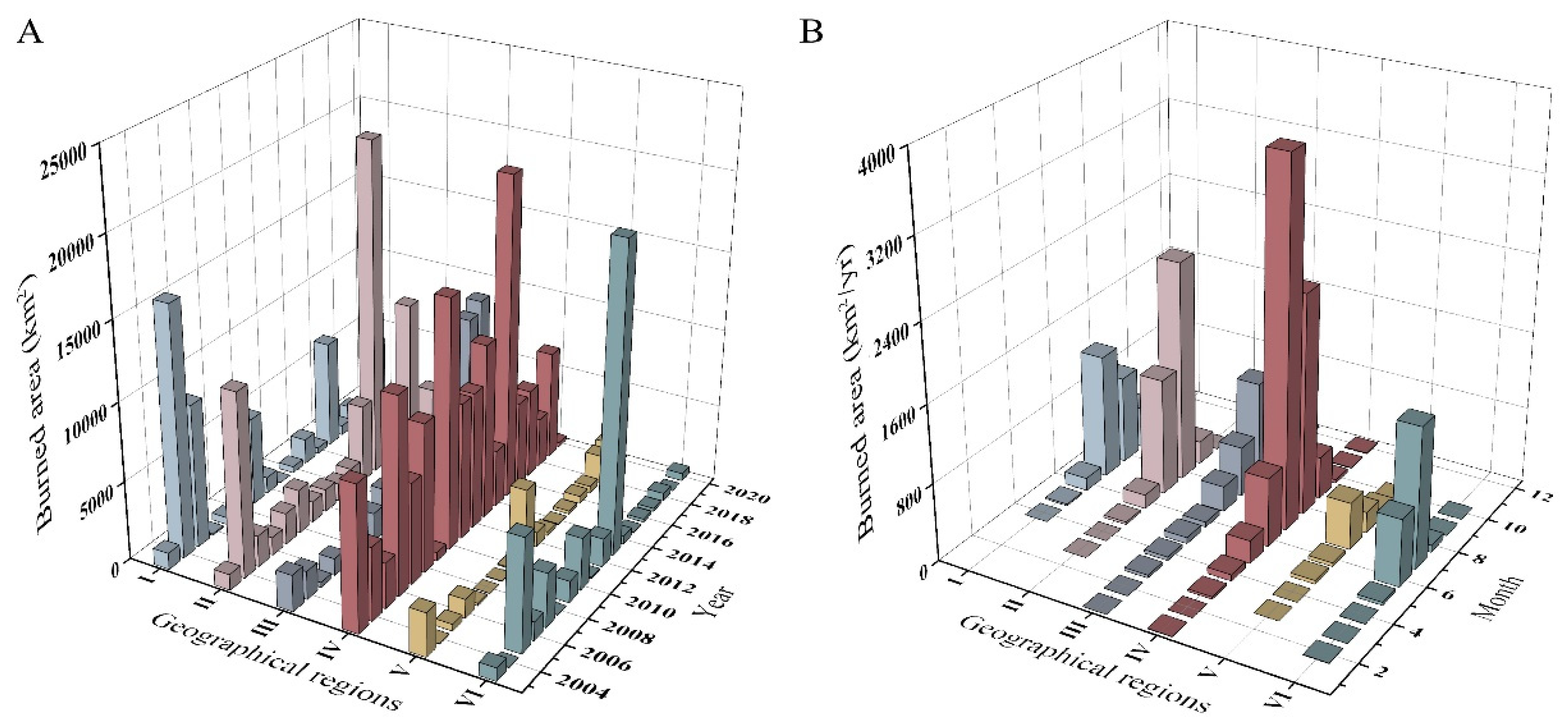

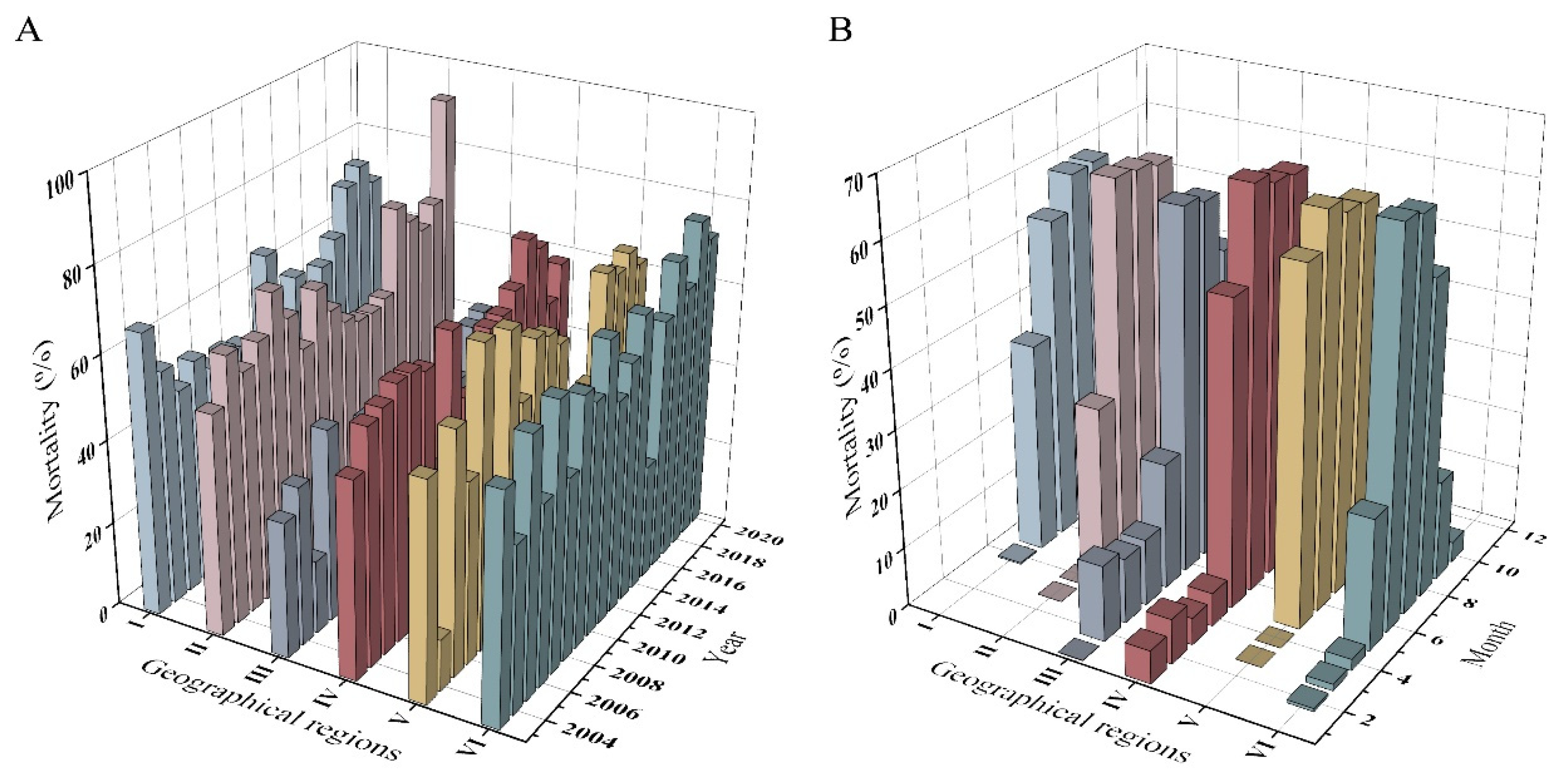

The analysis of the inter-annual variations of the burned area in the geographical regions shows large forest fires in Central Canada every year during the study period. Peaks of this value are evident also in Northern (5013 km

2 in 2013) and in Eastern Canada (3071 km

2 in 2014) (

Figure 4A). The seasonal trends of burned areas were largely similar in the study area since wildfires were concentrated in June to September in all regions with the highest peak in July (Central Canada) (

Figure 4B).

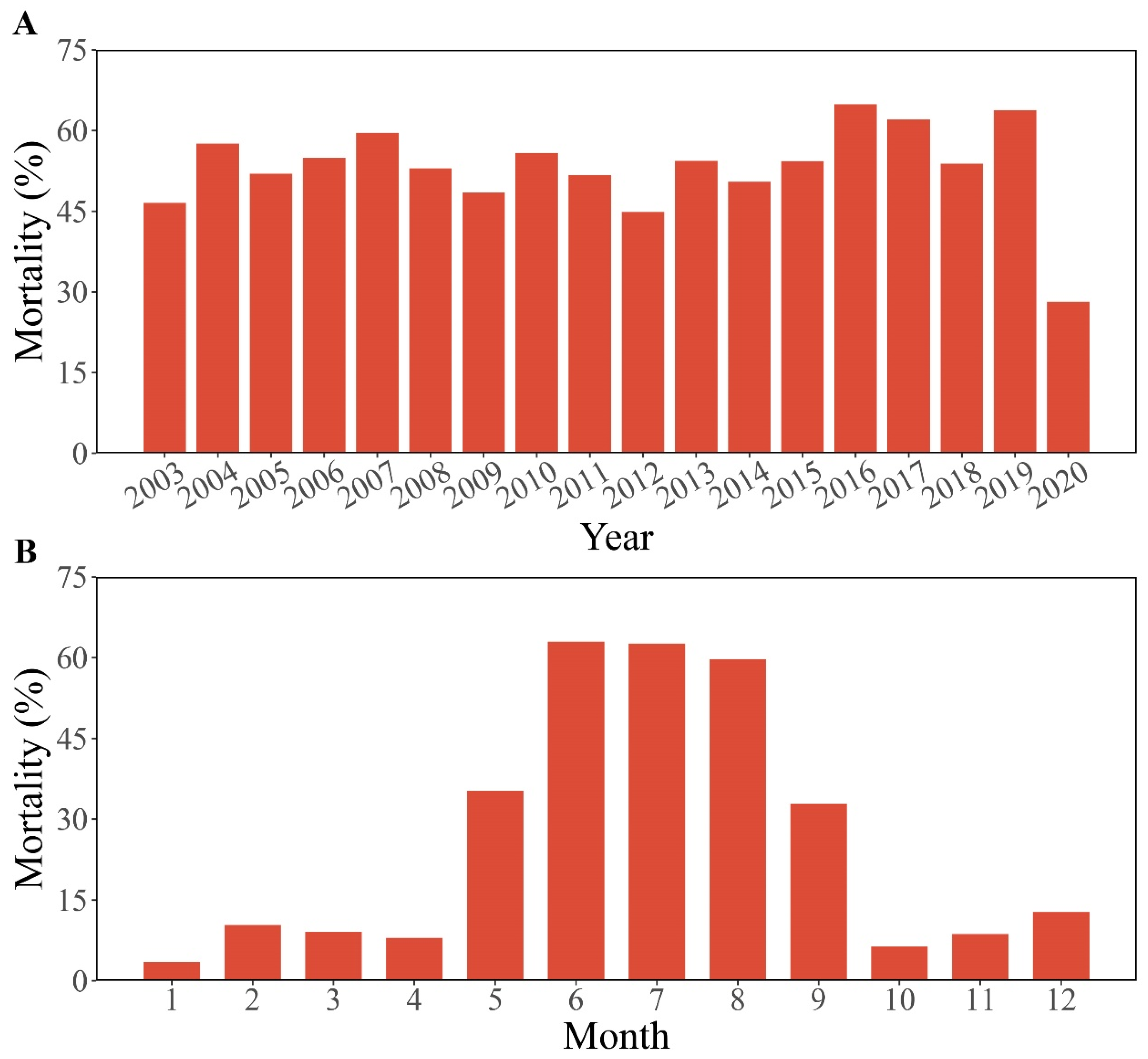

3.2. Spatio-Temporal Patterns of Forest Mortality

Forest mortality due to wildfire in the study area was on average 53.1% (2003-2020). The highest values were recorded in 2016 (64.9%), 2017 (62.1%) and 2019 (63.8%), all exceeding 40%, except in 2020 (28.2%) (

Figure 5A). The intra-annual seasonal trend overlaps the trend of burned areas (higher between June and September). The average mortality during this period was 50.7%, and lower than 13% in the other months with a minimum in January (3.5%) (

Figure 5B).

Forest mortality in the study area exceeded 50% for most regions (

Figure 6), except Western Canada (30.7%) (

Table 2). The average forest mortality in each region was above 51%, and the highest peak was recorded in Northern Canada (91%, 2020). The annual and seasonal variations were not noticeably different over the study area, and a relatively low inter-annual variability was recorded in Western Canada (

Figure 7A). Forest mortality was predominantly concentrated in the May to September and exceeded 60% in all geographical regions. It is worth noting that, in some regions (Western and Central Canada), forest mortality was noticeable also in some months (January to April) (

Figure 7B).

3.3. Correlations Among Forest Mortality, Fire Characteristics and Burned Area

The generalized linear model revealed a significant (

p < 0.001) influence of fire size and duration as well as their interaction on forest mortality, while burned area played a minor role (

p = 0.316) in driving the latter variable (

Table 3). There was a high and positive correlation between fire size and duration (r = 0.81) as well as these characteristics and burned area (r > 0.49). The coefficients of correlations between the fire characteristic on one side, and forest mortality on the other side was much lower but significant (r > 0.18). No significant correlation (r = 0.07) was revealed between the burned area and forest mortality (

Figure 8).

4. Discussion

Previous studies have found that the factors triggering the occurrence of fires are different in time and space, and must be ascribed to both natural and anthropogenic factors as well as to climate variability (Aakala et al., 2018). This study has explored the spatio-temporal patterns of burned areas and forest mortality due to a 18-year recurrence of forest wildfires in North America.

About the temporal variability of effects, this study has shown that, between 2003 and 2020, the burned area and fire-driven forest mortality were both extremely high, over 8000 km2/yr and 40%, respectively, with very few exceptions. Almost all forest wildfires (nearly 98%) occurred in the drier season, leading to the highest tree mortality during this period. The lower occurrence of fire in the cooler seasons may be explained by the increase of albedo (winter and spring), which leads to climate cooling with a consequent fire occurrence (Randerson et al., 2006; Rogers et al., 2013). In contrast, higher temperatures and drier air in summer noticeably increase the fire hazard, also enhanced by the accumulation of dead fuel (de Groot et al., 2013) (Zhao et al., 2021). This makes forests more vulnerable to high-intensity fires and results in higher forest mortality. The high forest mortality in the monitoring period is due to the predominance of crown fires, typical of the environments in North America (Stocks et al., 2004; de Groot et al., 2013). These high-intensity fires burn a fuel amount per unit area that is several times larger than in the case of surface fires (Wooster and Zhang, 2004). It is well known that the accumulation of fuel loads tends to increase fire occurrence (Mutch, 1970), and, as a consequence, trees are easily killed by these wildfires (Rogers et al., 2013; Rogers et al., 2015). Therefore, the increases in temperature and dryness combined with high-intensity crown fires are the main causes of tree mortality during the May to September.

The study has also shown that the severe forest fires in the study area are mainly concentrated in Central Canada (approx. 40% of the total burned area), but the fire-driven forest mortality was higher in other regions compared to the latter. However, the overall forest loss was high across all regions, with the exception of Western Canada, where the impacts of fire – both burned area and mortality – were the lowest. The generally high forest mortality may be related to the simpler forest structural complexity compared to tropical rainforests, which could result in a higher probability of fire occurrence (Heinselman, 1981). Compared with other biomes, boreal forests in North America have lower species diversity (Rogers et al., 2015), and the forests are dominated by coniferous species (Ribeiro-Kumara et al., 2020), including Picea mariana, Pinus banksiana, and Picea glauca (Rogers et al., 2013; Zhao et al., 2021). Due to their lower water content, and higher thickness and flammability of leaves, coniferous species are easier to burn than broad-leaved species (Kasischke et al., 2010). Thus, coniferous forests are more likely to experience fires compared to mixed forests with a high proportion of deciduous species (Cumming, 2001). For example, the probability of fire occurrence in pure coniferous forests is about 24 times higher than in pure broad-leaved forests in the boreal environment (Astrup et al., 2018). In Canada, pure coniferous stands account for over 60% of the total forest area, and more than half of forest fires are dominated by high-intensity crown fires (Stocks et al., 2004; de Groot et al., 2013), which usually lead to the rapid death of these conifer species.

Our findings indicate that, in North America, post-fire forest mortality is mainly influenced by fire size and duration. Fire combustion unleashes a substantial amount of energy (Wooster and Zhang, 2004; de Groot et al., 2013; Hantson et al., 2022), which consequently prolongs the fire duration. This energy could also increase the probability of death of heat-damaged trees, and long-term high temperatures could also kill trees directly (Zhang et al., 2017; Zhao et al., 2023). Additionally, the increased frequency of long-term droughts has led to more frequent fires. Coupled with heatwaves, they have increased the probability of fire occurrence across all forest biomes (Clarke et al., 2020). Wildfires in forests with high intensity and severity may last for months (Cansler and McKenzie, 2014; Laurent et al., 2019), leading to extremely high tree mortality. Under the current climate change scenario, the rising frequency of heatwaves and extreme drought events is increasing the likelihood of larger, longer-duration, and higher-intensity fires in the boreal forests of North America, ultimately driving higher rates of forest mortality.

5. Conclusions

Using satellite-based data, the spatial and temporal patterns of burned area and fire-driven forest mortality were explored in North America (Alaska and Canada) over a 18-year period. The relationships between this mortality and fire regime factors and burned area were also analyzed.

Both the burned area and mortality was high, over 8000 km2/yr and 40%, respectively. Forest fires mainly occurred in May to September and one region (Central Canada) accounted for 40% of the burned area. The less affected region was Western Canada. The fire size and duration were the main drivers of the high forest mortality.

Overall, the study indicates to forest managers and authorities which areas and time period are the most sensitive to the detrimental effects of forest wildfire in boreal forests of North America.

Funding

This work was funded by National Natural Science Foundation of China (32201543), Natural Science Foundation of Guangxi Province (2021AC19325).

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, upon reasonable request.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Aakala, T., Pasanen, L., Helama, S., Vakkari, V., Drobyshev, I., Seppä, H., Kuuluvainen, T., Stivrins, N., Wallenius, T., Vasander, H., Holmström, L., 2018. Multiscale variation in drought controlled historical forest fire activity in the boreal forests of eastern Fennoscandia. Ecological Monographs 88, 74-91. [CrossRef]

- Abatzoglou, J.T., Williams, A.P., Barbero, R., 2019. Global Emergence of Anthropogenic Climate Change in Fire Weather Indices. Geophysical Research Letters 46, 326-336. [CrossRef]

- Astrup, R., Bernier, P.Y., Genet, H., Lutz, D.A., Bright, R.M., 2018. A sensible climate solution for the boreal forest. Nature Climate Change 8, 11-12. [CrossRef]

- Berner, L.T., Law, B.E., Meddens, A.J.H., Hicke, J.A., 2017. Tree mortality from fires, bark beetles, and timber harvest during a hot and dry decade in the western United States (2003–2012). Environmental Research Letters 12, 065005.

- Bonan, G.B., 2008. Forests and Climate Change: Forcings, Feedbacks, and the Climate Benefits of Forests. Science 320, 1444-1449.

- Canadell, J.G., Meyer, C.P., Cook, G.D., Dowdy, A., Briggs, P.R., Knauer, J., Pepler, A., Haverd, V., 2021. Multi-decadal increase of forest burned area in Australia is linked to climate change. Nature Communications 12, 6921. [CrossRef]

- Cansler, C.A., McKenzie, D., 2014. Climate, fire size, and biophysical setting control fire severity and spatial pattern in the northern Cascade Range, USA. Ecological Applications 24, 1037-1056. [CrossRef]

- Clarke, H., Penman, T., Boer, M., Cary, G.J., Fontaine, J.B., Price, O., Bradstock, R., 2020. The Proximal Drivers of Large Fires: A Pyrogeographic Study. Frontiers in Earth Science 8. [CrossRef]

- Cumming, S.G., 2001. FOREST TYPE AND WILDFIRE IN THE ALBERTA BOREAL MIXEDWOOD: WHAT DO FIRES BURN? Ecological Applications 11, 97-110.

- de Groot, W.J., Cantin, A.S., Flannigan, M.D., Soja, A.J., Gowman, L.M., Newbery, A., 2013. A comparison of Canadian and Russian boreal forest fire regimes. Forest Ecology and Management 294, 23-34. [CrossRef]

- Earles, J.M., North, M.P., Hurteau, M.D., 2014. Wildfire and drought dynamics destabilize carbon stores of fire-suppressed forests. Ecological Applications 24, 732-740. [CrossRef]

- Field, R.D., van der Werf, G.R., Fanin, T., Fetzer, E.J., Fuller, R., Jethva, H., Levy, R., Livesey, N.J., Luo, M., Torres, O., Worden, H.M., 2016. Indonesian fire activity and smoke pollution in 2015 show persistent nonlinear sensitivity to El Niño-induced drought. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 113, 9204-9209. [CrossRef]

- Friedlingstein, P., Jones, M.W., O’Sullivan, M., Andrew, R.M., Hauck, J., Peters, G.P., Peters, W., Pongratz, J., Sitch, S., Le Quéré, C., Bakker, D.C.E., Canadell, J.G., Ciais, P., Jackson, R.B., Anthoni, P., Barbero, L., Bastos, A., Bastrikov, V., Becker, M., Bopp, L., Buitenhuis, E., Chandra, N., Chevallier, F., Chini, L.P., Currie, K.I., Feely, R.A., Gehlen, M., Gilfillan, D., Gkritzalis, T., Goll, D.S., Gruber, N., Gutekunst, S., Harris, I., Haverd, V., Houghton, R.A., Hurtt, G., Ilyina, T., Jain, A.K., Joetzjer, E., Kaplan, J.O., Kato, E., Klein Goldewijk, K., Korsbakken, J.I., Landschützer, P., Lauvset, S.K., Lefèvre, N., Lenton, A., Lienert, S., Lombardozzi, D., Marland, G., McGuire, P.C., Melton, J.R., Metzl, N., Munro, D.R., Nabel, J.E.M.S., Nakaoka, S.I., Neill, C., Omar, A.M., Ono, T., Peregon, A., Pierrot, D., Poulter, B., Rehder, G., Resplandy, L., Robertson, E., Rödenbeck, C., Séférian, R., Schwinger, J., Smith, N., Tans, P.P., Tian, H., Tilbrook, B., Tubiello, F.N., van der Werf, G.R., Wiltshire, A.J., Zaehle, S., 2019. Global Carbon Budget 2019. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 11, 1783-1838.

- Giglio, L., Boschetti, L., Roy, D.P., Humber, M.L., Justice, C.O., 2018. The Collection 6 MODIS burned area mapping algorithm and product. Remote Sensing of Environment 217, 72-85. [CrossRef]

- Hansen, M.C., Potapov, P.V., Moore, R., Hancher, M., Turubanova, S.A., Tyukavina, A., Thau, D., Stehman, S.V., Goetz, S.J., Loveland, T.R., Kommareddy, A., Egorov, A., Chini, L., Justice, C.O., Townshend, J.R.G., 2013. High-Resolution Global Maps of 21st-Century Forest Cover Change. Science 342, 850-853. [CrossRef]

- Hantson, S., Andela, N., Goulden, M.L., Randerson, J.T., 2022. Human-ignited fires result in more extreme fire behavior and ecosystem impacts. Nature Communications 13, 2717. [CrossRef]

- Heinselman, M.L., 1981. Fire intensity and frequency as factors in the distribution and structure of northern ecosystems [Canadian and Alaskan boreal forests, Rocky Mountain subalpine forests, Great Lakes-Acadian forests, includes history, management; Canada; USA].

- Hicke, J.A., Allen, C.D., Desai, A.R., Dietze, M.C., Hall, R.J., Hogg, E.H., Kashian, D.M., Moore, D., Raffa, K.F., Sturrock, R.N., Vogelmann, J., 2012. Effects of biotic disturbances on forest carbon cycling in the United States and Canada. Global Change Biology 18, 7-34. [CrossRef]

- Hicke, J.A., Meddens, A.J.H., Allen, C.D., Kolden, C.A., 2013. Carbon stocks of trees killed by bark beetles and wildfire in the western United States. Environmental Research Letters 8, 035032. [CrossRef]

- Hicke, J.A., Meddens, A.J.H., Kolden, C.A., 2015. Recent Tree Mortality in the Western United States from Bark Beetles and Forest Fires. Forest Science 62, 141-153. [CrossRef]

- Hood, S.M., Varner, J.M., van Mantgem, P., Cansler, C.A., 2018. Fire and tree death: understanding and improving modeling of fire-induced tree mortality. Environmental Research Letters 13, 113004. [CrossRef]

- Jain, P., Castellanos-Acuna, D., Coogan, S.C.P., Abatzoglou, J.T., Flannigan, M.D., 2022. Observed increases in extreme fire weather driven by atmospheric humidity and temperature. Nature Climate Change 12, 63-70. [CrossRef]

- Jones, M.W., Veraverbeke, S., Andela, N., Doerr, S.H., Kolden, C., Mataveli, G., Pettinari, M.L., Le Quéré, C., Rosan, T.M., van der Werf, G.R., van Wees, D., Abatzoglou, J.T., 2024. Global rise in forest fire emissions linked to climate change in the extratropics. Science 386, eadl5889. [CrossRef]

- Kasischke, E.S., Verbyla, D.L., Rupp, T.S., McGuire, A.D., Murphy, K.A., Jandt, R., Barnes, J.L., Hoy, E.E., Duffy, P.A., Calef, M., Turetsky, M.R., 2010. Alaska’s changing fire regime — implications for the vulnerability of its boreal forestsThis article is one of a selection of papers from The Dynamics of Change in Alaska’s Boreal Forests: Resilience and Vulnerability in Response to Climate Warming. Canadian Journal of Forest Research 40, 1313-1324. [CrossRef]

- Laurent, P., Mouillot, F., Moreno, M.V., Yue, C., Ciais, P., 2019. Varying relationships between fire radiative power and fire size at a global scale. Biogeosciences 16, 275-288. [CrossRef]

- Lenton, T.M., Held, H., Kriegler, E., Hall, J.W., Lucht, W., Rahmstorf, S., Schellnhuber, H.J., 2008. Tipping elements in the Earth’s climate system. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 105, 1786-1793.

- Li, T., Cui, L., Liu, L., Chen, Y., Liu, H., Song, X., Xu, Z., 2023. Advances in the study of global forest wildfires. Journal of Soils and Sediments 23, 2654-2668. [CrossRef]

- Lindenmayer, D.B., Taylor, C., 2020. New spatial analyses of Australian wildfires highlight the need for new fire, resource, and conservation policies. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 117, 12481-12485. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z., Chen, M., Guo, Y., Wang, X., Zhang, L., Zhou, J., Li, H., Shi, Q., 2019. Self-assembly of cationic amphiphilic cellulose-g-poly (p-dioxanone) copolymers. Carbohydrate Polymers 204, 214-222. [CrossRef]

- Mack, M.C., Walker, X.J., Johnstone, J.F., Alexander, H.D., Melvin, A.M., Jean, M., Miller, S.N., 2021. Carbon loss from boreal forest wildfires offset by increased dominance of deciduous trees. Science 372, 280-283. [CrossRef]

- Mutch, R.W., 1970. Wildland Fires and Ecosystems--A Hypothesis. Ecology 51, 1046-1051.

- Phillips, C.A., Rogers, B.M., Elder, M., Cooperdock, S., Moubarak, M., Randerson, J.T., Frumhoff, P.C., 2022. Escalating carbon emissions from North American boreal forest wildfires and the climate mitigation potential of fire management. Science Advances 8, eabl7161. [CrossRef]

- Randerson, J.T., Liu, H., Flanner, M.G., Chambers, S.D., Jin, Y., Hess, P.G., Pfister, G., Mack, M.C., Treseder, K.K., Welp, L.R., Chapin, F.S., Harden, J.W., Goulden, M.L., Lyons, E., Neff, J.C., Schuur, E.A.G., Zender, C.S., 2006. The Impact of Boreal Forest Fire on Climate Warming. Science 314, 1130-1132. [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro-Kumara, C., Köster, E., Aaltonen, H., Köster, K., 2020. How do forest fires affect soil greenhouse gas emissions in upland boreal forests? A review. Environmental Research 184, 109328. [CrossRef]

- Rogers, B.M., Randerson, J.T., Bonan, G.B., 2013. High-latitude cooling associated with landscape changes from North American boreal forest fires. Biogeosciences 10, 699-718. [CrossRef]

- Rogers, B.M., Soja, A.J., Goulden, M.L., Randerson, J.T., 2015. Influence of tree species on continental differences in boreal fires and climate feedbacks. Nature Geoscience 8, 228-234.

- Sánchez-Pinillos, M., D’Orangeville, L., Boulanger, Y., Comeau, P., Wang, J., Taylor, A.R., Kneeshaw, D., 2022. Sequential droughts: A silent trigger of boreal forest mortality. Global Change Biology 28, 542-556. [CrossRef]

- Stocks, B.J., Alexander, M.E., Lanoville, R.A., 2004. Overview of the International Crown Fire Modelling Experiment (ICFME). Canadian Journal of Forest Research 34, 1543-1547. [CrossRef]

- Tamarin-Brodsky, T., Hodges, K., Hoskins, B.J., Shepherd, T.G., 2020. Changes in Northern Hemisphere temperature variability shaped by regional warming patterns. Nature Geoscience 13, 414-421. [CrossRef]

- Trumbore, S., Brando, P., Hartmann, H., 2015. Forest health and global change. Science 349, 814-818. [CrossRef]

- van der Velde, I.R., van der Werf, G.R., Houweling, S., Maasakkers, J.D., Borsdorff, T., Landgraf, J., Tol, P., van Kempen, T.A., van Hees, R., Hoogeveen, R., Veefkind, J.P., Aben, I., 2021. Vast CO2 release from Australian fires in 2019–2020 constrained by satellite. Nature 597, 366-369. [CrossRef]

- van Lierop, P., Lindquist, E., Sathyapala, S., Franceschini, G., 2015. Global forest area disturbance from fire, insect pests, diseases and severe weather events. Forest Ecology and Management 352, 78-88. [CrossRef]

- van Oldenborgh, G.J., Krikken, F., Lewis, S., Leach, N.J., Lehner, F., Saunders, K.R., van Weele, M., Haustein, K., Li, S., Wallom, D., Sparrow, S., Arrighi, J., Singh, R.K., van Aalst, M.K., Philip, S.Y., Vautard, R., Otto, F.E.L., 2021. Attribution of the Australian bushfire risk to anthropogenic climate change. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 21, 941-960.

- Webb, E.E., Alexander, H.D., Paulson, A.K., Loranty, M.M., DeMarco, J., Talucci, A.C., Spektor, V., Zimov, N., Lichstein, J.W., 2024. Fire-Induced Carbon Loss and Tree Mortality in Siberian Larch Forests. Geophysical Research Letters 51, e2023GL105216. [CrossRef]

- Wooster, M.J., Zhang, Y.H., 2004. Boreal forest fires burn less intensely in Russia than in North America. Geophysical Research Letters 31. [CrossRef]

- Xi, Y., Zhang, W., Wei, F., Fang, Z., Fensholt, R., 2024. Boreal tree species diversity increases with global warming but is reversed by extremes. Nature Plants 10, 1473-1483. [CrossRef]

- Xu, T.-L., Yang, R.-Q., Zaw, Z., Fu, P.-L., Panthi, S., Bräuning, A., Fan, Z.-X., 2024. Growth-climate relationships of four tree species in the subtropical evergreen broad-leaved forests in Southwest China. Dendrochronologia 85, 126186. [CrossRef]

- Ye, T., Xu, R., Yue, X., Chen, G., Yu, P., Coêlho, M.S.Z.S., Saldiva, P.H.N., Abramson, M.J., Guo, Y., Li, S., 2022. Short-term exposure to wildfire-related PM2.5 increases mortality risks and burdens in Brazil. Nature Communications 13, 7651. [CrossRef]

- Yue, C., Ciais, P., Zhu, D., Wang, T., Peng, S.S., Piao, S.L., 2016. How have past fire disturbances contributed to the current carbon balance of boreal ecosystems? Biogeosciences 13, 675-690. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q., Shao, M.a., Jia, X., Wei, X., 2017. Relationship of Climatic and Forest Factors to Drought- and Heat-Induced Tree Mortality. PLOS ONE 12, e0169770. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J., Wang, J., Meng, Y., Du, Z., Ma, H., Qiu, L., Tian, Q., Wang, L., Xu, M., Zhao, H., Yue, C., 2023. Spatiotemporal patterns of fire-driven forest mortality in China. Forest Ecology and Management 529, 120678. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J., Wang, L., Hou, X., Li, G., Tian, Q., Chan, E., Ciais, P., Yu, Q., Yue, C., 2021. Fire Regime Impacts on Postfire Diurnal Land Surface Temperature Change Over North American Boreal Forest. Journal of Geophysical Research: Atmospheres 126, e2021JD035589. [CrossRef]

- Zheng, B., Ciais, P., Chevallier, F., Yang, H., Canadell, J.G., Chen, Y., van der Velde, I.R., Aben, I., Chuvieco, E., Davis, S.J., Deeter, M., Hong, C., Kong, Y., Li, H., Li, H., Lin, X., He, K., Zhang, Q., 2023. Record-high CO2 emissions from boreal fires in 2021. Science 379, 912-917.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).