Submitted:

14 June 2025

Posted:

16 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Brief Overview of the Project

- ▪

- 🔵 Blue: Low glucose (<70 mg/dL) - Hypoglycemia

- ▪

- 🟢 Green: Normal range (70–190 mg/dL) - Normoglycemia

- ▪

- 🔴 Red: High glucose (>190 mg/dL) - Hyperglycemia

1.2. Problem Statement

1.4. Structure of the Overall Paper

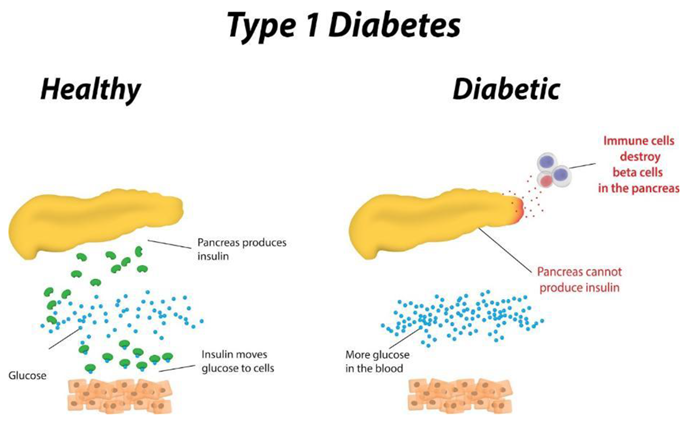

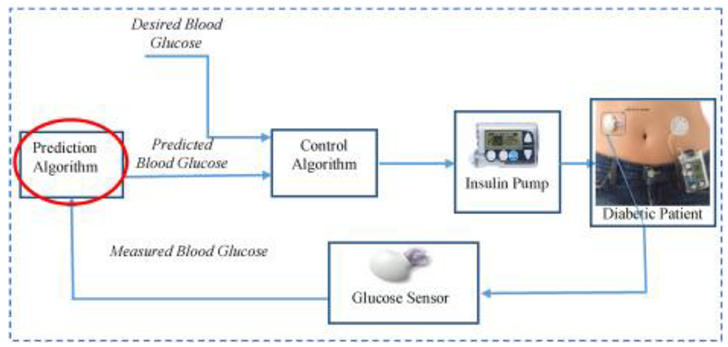

2. Introduction to Glucose Prediction Visualization Problem in Type 1 Diabetes

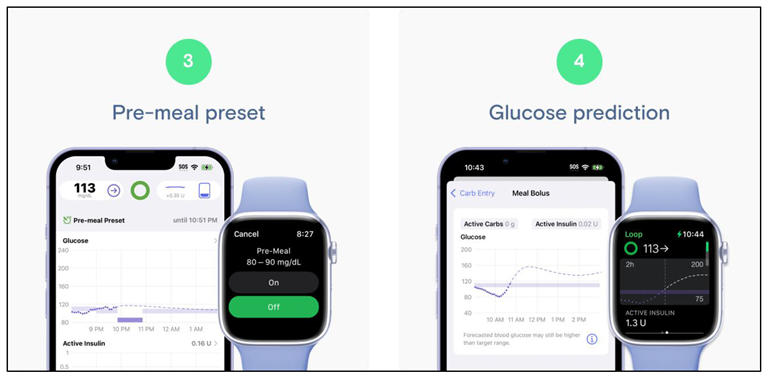

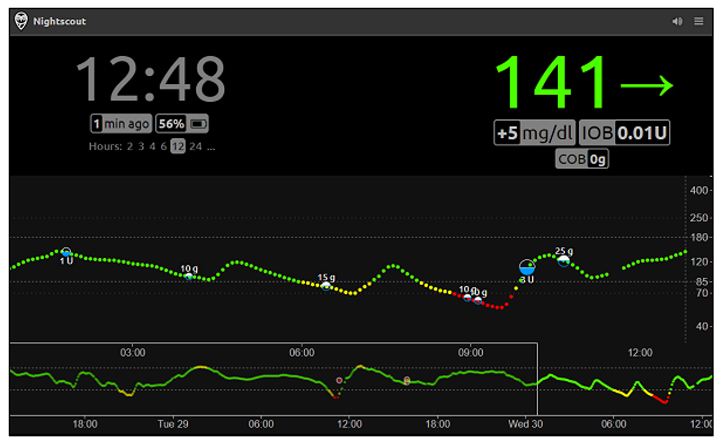

2.1. Dexcom Clarity, Tidepool, and Nightscout Interactive Dashboard

- ▪

- Dexcom Clarity is a proprietary system developed by Dexcom Inc., designed to work exclusively with Dexcom CGM devices . It provides users and healthcare providers with detailed trend analysis, daily patterns, and retrospective reports through a sleek and clinically validated interface [8].

- ▪

- Tidepool is a non-profit, open-source platform that supports data integration from multiple diabetes devices. It emphasizes accessibility, multi-device compatibility, and visual clarity, offering users various chart types (e.g., stacked bar, pie, and line graphs) to support personalized diabetes management [9].

- ▪

- Nightscout is an open-source, community-driven project that enables real-time remote access to CGM data. Unlike commercial systems, it prioritizes customizability and autonomy but lacks built-in predictive analytics and requires technical setup by the user [10].

- ▪

- Data Source Compatibility

- ▪

- Visualization and Interactivity

- ▪

- Clinical Interpretability

- ▪

- System Flexibility and Scalability

| Aspect | Dexcom Clarity | Tidepool | Nightscout | Proposed Project Differences |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Data Source Compatibility | Limited to Dexcom only devices | Supports multiple device data, but integration can be challenging due to lack of access to the public of the United Kingdom as of 26/03/2025 | Provides real-time access from connected CGM devices. However, data is not always available due to the fact it depends on real users using the system consistently. Also, Nightscout does not predict glucose data. | Uses synthetic data to simulate realistic glucose patterns available 24/7. |

| Visualization and Interactivity | Sleek interface with detailed reports and trend graphs | Provides interactive features with professional visualization yet presenting necessary information effectively. | Colour coded graphs with “just enough design” inspired architecture. However not visually appealing. | Features an interactive tree visualization and not just limited to the generic dashboard. |

| Clinical Interpretability | Presents trend analysis, and data can be shared to caregivers, clinicians, researchers and so on | Offers deep analysis of data and presents them in multiple visual formats such as line, graphs, pie charts, stacked bar charts and so on. | Visualizes raw data with little to no integrated clinical context | Enhances interpretability containing colour coded risk indicators to showcase risk zones. Suitable for all devices that have access to open html files. |

| System Flexibility and Scalability | Constrained as a proprietary ecosystem | Moderately flexible integration from Tidepool official documentation, however challenges include accessibility to certain regions. | Open-sources and flexible to adapt, however has a complicated codebase and lacks predictive glucose element. | Designed with a modular architecture, allowing future enhancements, scalability and with the potential for implementation of real-world patient data. |

- ▪

- Data Source and Implementation – Whereas existing solutions rely on real patient data, our project exclusively employs synthetic data. This not only solves ethical issues in regard to privacy concerns but also allows for controlled experimentation. Furthermore, the project is developed in Python, a language not commonly used in commercial CGM applications - demonstrating the versatility and accessibility of open-source tools.

- ▪

- Visualization Approach – Unlike traditional dashboards, the project introduces an innovative interactive tree visualization. By generating an HTML Plotly file, the tool provides a dynamic, offline-accessible visual that is suitable for multiple devices. This method bridges the gap between complex statistical forecasting and clinical interpretability, offering an intuitive means to explore glucose dynamics.

- ▪

- Methodological Focus – The project leverages a statistical-based ARIMA model for prediction, moving away from the predominant reliance on machine learning models. This choice addresses the "black box" issue common in AI approaches, thereby enhancing the transparency and interpretability of the forecasting process. This focus is especially crucial in clinical settings where understanding the underlying data patterns is essential.

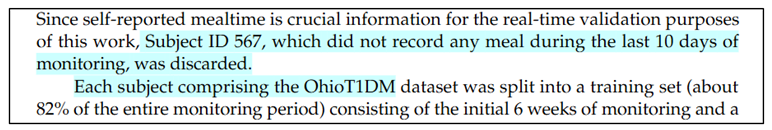

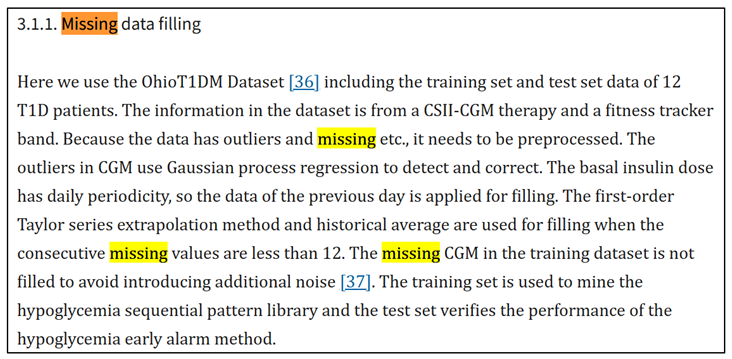

2.2. Decision Choice on Dataset Reliability

3. Introduction to Glucose Prediction Models

3.1. Physiological-Based Models also Sometimes Referred to as Mathematical-Based Models

3.2. Data-Driven Models

3.3. Hybrid Models

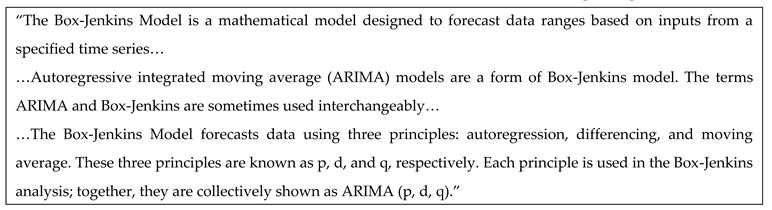

3.4. ARIMA-Based Rolling Prediction Framework

- ▪

- Auto Regressive (AR) → Uses past values to predict the future.

- ▪

- Integrated (I) → Makes the data stable (stationary).

- ▪

- Moving Average (MA) → Uses past prediction errors to improve future predictions.

- ▪

- p is how many past values to use (memory of past readings).

- ▪

- d is how many times subtract past values to make the data stable.

- ▪

- q is How much past error to consider (to correct mistakes).

- ▪

- it is a model less prone to overfitting,

- ▪

- It captures the intuition that the change in glucose from one time step to the next

- ▪

- it requires a minimal amount of data to train (only a few past points to estimate the next prediction)

4. Project Logic & Structure

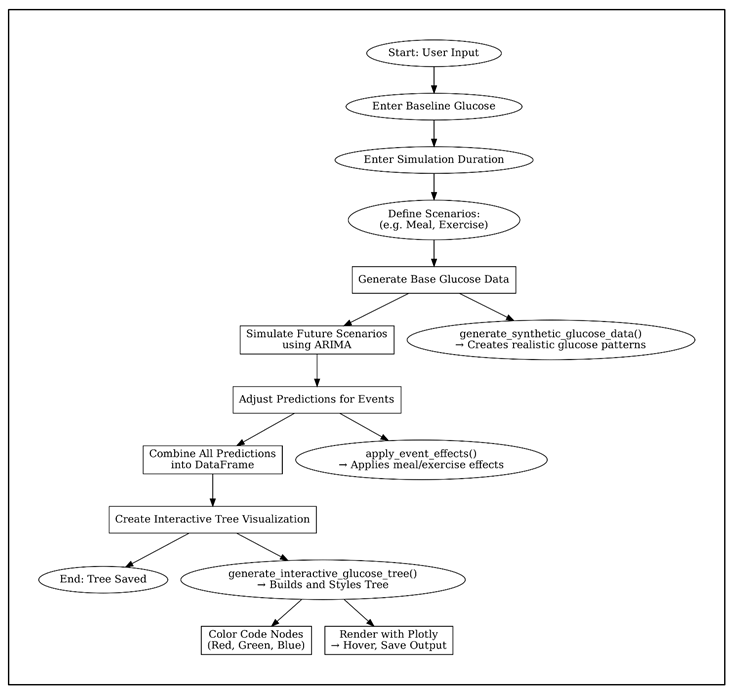

4.1. Codebase

- ▪

- ▪

- cd glucose-visual-scenario-tree

- ▪

- Which intervention keeps glucose within target the longest

- ▪

- How quickly glucose may rise post-meal

- ▪

- Which scenarios require caution (red-heavy branches)

- ▪

- The urgency of glucose correction or insulin dosing

4.2. Pseudocode Diagram

5. Final Thoughts

5.1. Possible Future Work

5.2. Conclusions

6. Additional Information

6.1. Glossary

- First,

- Zoom and filter,

- Then details on demand

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization (2024). Diabetes. [online] World Health Organization. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/diabetes.

- Plotly (2023). Plotly Python Graphing Library. [online] plotly.com. Available online: https://plotly.com/python/.

- Figure 1. (n.d.). Available at: Type 1 Diabetes Image Explanation. (n.d.). Available online: https://www.myhealthexplained.com/diabetes-information/diabetes-articles/type-1-diabetes-prevention.

- Dexcom. (2024). Dexcom G7 Sensor. [online]. Available online: https://www.dexcom.com/en-GB/dexcom-shop/g7/stp-gt-001 (accessed on 23 April 2025).

- Figure 2. (n.d.). Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S020852161830127X.

- Arxiv.org. (2021). GlucoBench: Curated List of Continuous Glucose Monitoring Datasets with Prediction Benchmarks. [online]. Available online: https://arxiv.org/html/2410.05780v1 (accessed on 7 April 2025).

- srunyon (2016). Dexcom CLARITY | Diabetes Management Software. [online] Dexcom. Available online: https://www.dexcom.com/clarity.

- Dexcom (2018). Dexcom. [online] Dexcom. Available online: https://www.dexcom.com/en-GB.

- www.tidepool.org. (n.d.). Tidepool. [online]. Available online: https://www.tidepool.org/.

- nightscout.github.io. (n.d.). What is Nightscout? - Nightscout. [online]. Available online: https://nightscout.github.io/.

- Figure 3. (n.d.). Available online: https://www.tidepool.org/blog/tidepool-loop-what-makes-us-different.

- Figure 4. (n.d.). Available online: https://www.nice.org.uk/advice/mib233/chapter/The-technology#:~:text=This%20alert%20notifies%20the%20user,alert%20can%20be%20turned%20off.

- Figure 5. (n.d.). Available at: https://nightscout.github.io. European Union (2018). General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR). [online] General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR). Available online: https://gdpr-info.eu/.

- smarthealth.cs.ohio.edu. (n.d.). OhioT1DM Dataset. [online]. Available online: http://smarthealth.cs.ohio.edu/OhioT1DM-dataset.html.

- Prendin, F.; Díez, J.-L.; Del Favero, S.; Sparacino, G.; Facchinetti, A.; Bondia, J. Assessment of Seasonal Stochastic Local Models for Glucose Prediction without Meal Size Information under Free-Living Conditions. Sensors 2022, 22, 8682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, N.; Yu, X.; Yang, T.; Zhao, Y.; Li, H. A hypoglycemia early alarm method for patients with type 1 diabetes based on multi-dimensional sequential pattern mining. Heliyon 2022, 8, e11372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zecchin, C.; Facchinetti, A.; Sparacino, G.; De Nicolao, G.; Cobelli, C. Neural Network Incorporating Meal Information Improves Accuracy of Short-Time Prediction of Glucose Concentration. IEEE Transactions on Biomedical Engineering 2012, 59, 1550–1560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, B.; Yuan, Y.; Yang, J.; Qiu, L.; Zhang, S.; Shi, J. Predicting Blood Glucose Concentration after Short-Acting Insulin Injection Using Discontinuous Injection Records. 2022, 22, 8454–8454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gzar, D.A.; Mahmood, A.M.; Abbas, M.K. A Comparative Study of Regression Machine Learning Algorithms: Tradeoff Between Accuracy and Computational Complexity. Mathematical Modelling of Engineering Problems 2022, 9, 1217–1224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gültekin, H. Time Series Analysis and Forecasting with ARIMA - Hazal Gültekin - Medium. [online] Medium. 2024. Available online: https://medium.com/@hazallgultekin/time-series-analysis-and-forecasting-with-arima-8be02ba2665a (accessed on 7 April 2025).

- Yang, J.; Li, L.; Shi, Y.; Xie, X. An ARIMA Model With Adaptive Orders for Predicting Blood Glucose Concentrations and Hypoglycemia. IEEE Journal of Biomedical and Health Informatics 2019, 23, 1251–1260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krishnamoorthy, U.; VKarthika Mathumitha, M.K.; Panchal, H.; Vijay Kumar, A. Learned prediction of cholesterol and glucose using ARIMA and LSTM models – A comparison. Results in Control and Optimization 2023, 14, 100362–100362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rancati, S.; Bosoni, P.; Schiaffini, R.; Deodati, A.; Mongini, P.A.; Sacchi, L.; Toffanin, C.; Bellazzi, R. Exploration of Foundational Models for Blood Glucose Forecasting in Type-1 Diabetes Pediatric Patients. Diabetology 2024, 5, 584–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, G. Box-Jenkins Model. [online] Investopedia. 2019. Available online: https://www.investopedia.com/terms/b/box-jenkins-model.asp.

- Chapter 44 Ben Shneiderman’s Visualization Mantra | Spring 2021 EDAV Community Contributions. (n.d.). [online] jtr13.github.io. Available online: https://jtr13.github.io/cc21/ben-shneidermans-visualization-mantra.html.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).