Biological computing was created by nature without a user’s guide attached, so our basic difficulty is that "engineers want to

design systems; neuroscientists want to

analyze an existing one they little understand" [

70]. We must never forget, especially when experimenting to imitate neuronal learning using recurrence and feedback: "Neurons ensure the

directional propagation of signals throughout the nervous system. The

functional asymmetry of neurons is supported by cellular compartmentation: the cell body and dendrites (somatodendritic compartment) receive synaptic inputs, and the axon propagates the action potentials that trigger synaptic release toward target cells." [

71] We must recall the functional asymmetry and the networked nature (slow, distributed processing) when discussing the biological relevance of a method, such as backpropagation.

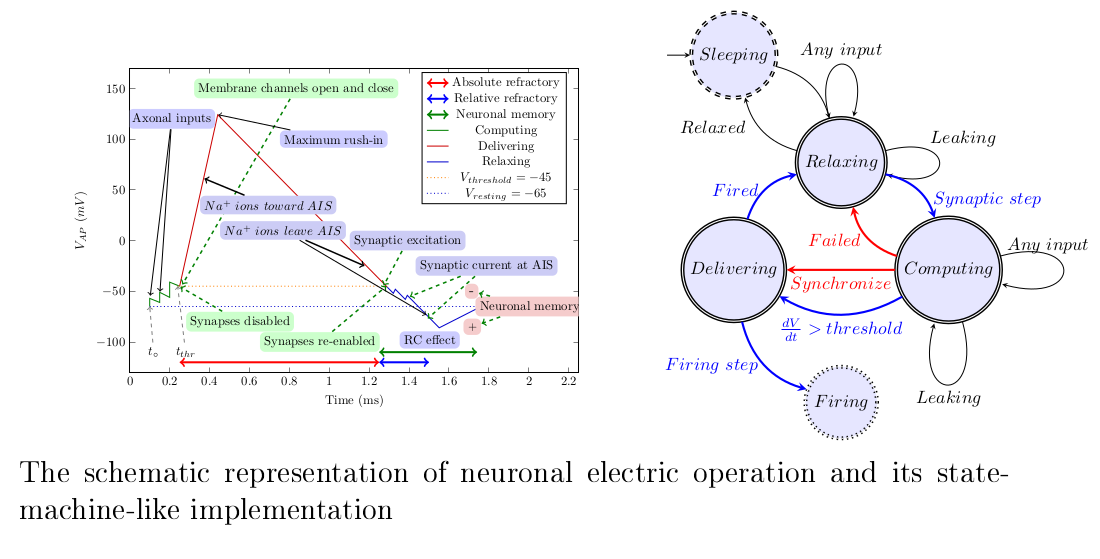

Figure 1.

The conceptual graph of the action potential. (Figure 10 from [

10]).

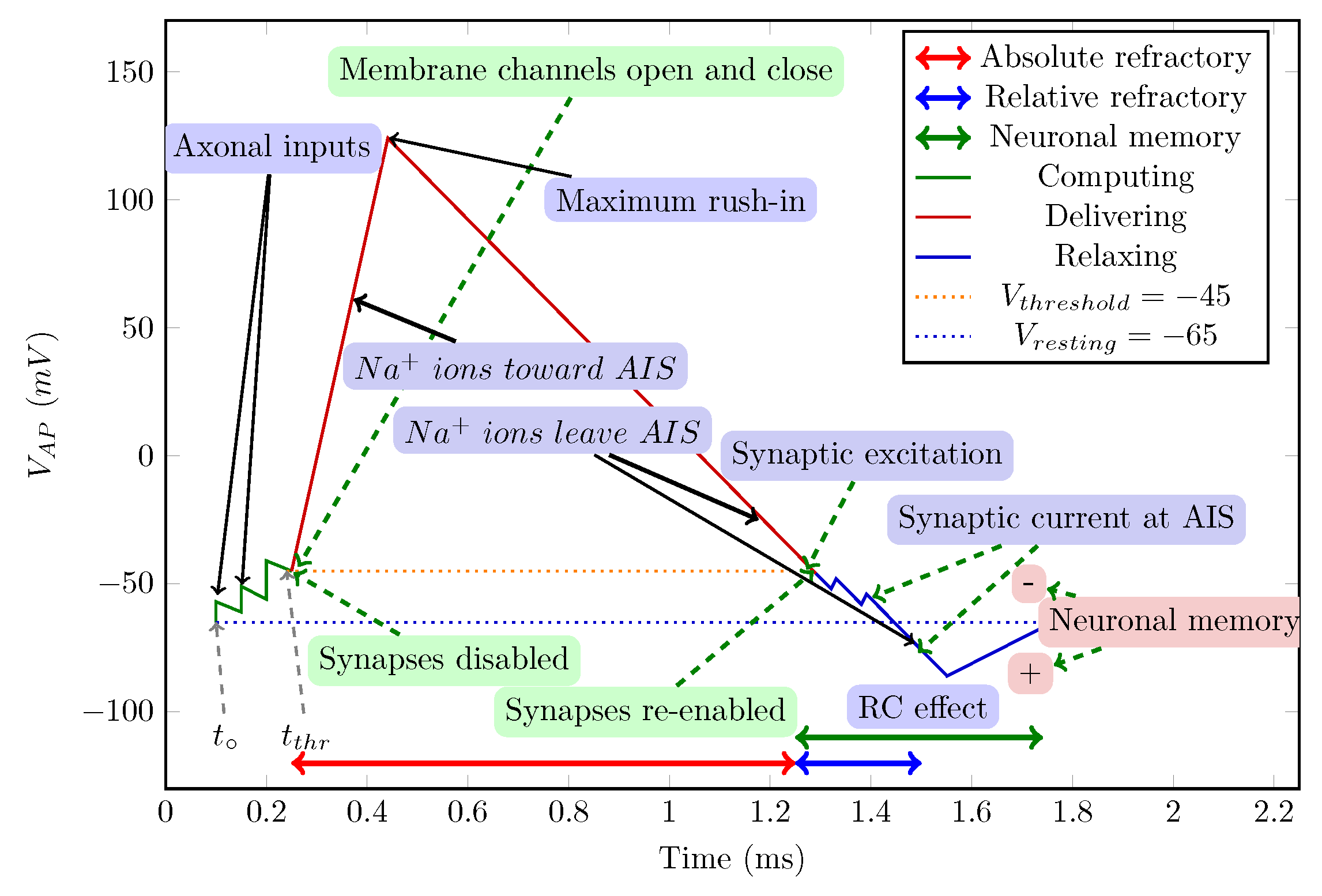

Figure 2.

The model of a neuron as an abstract state machine. (Figure 9 from [

10]).

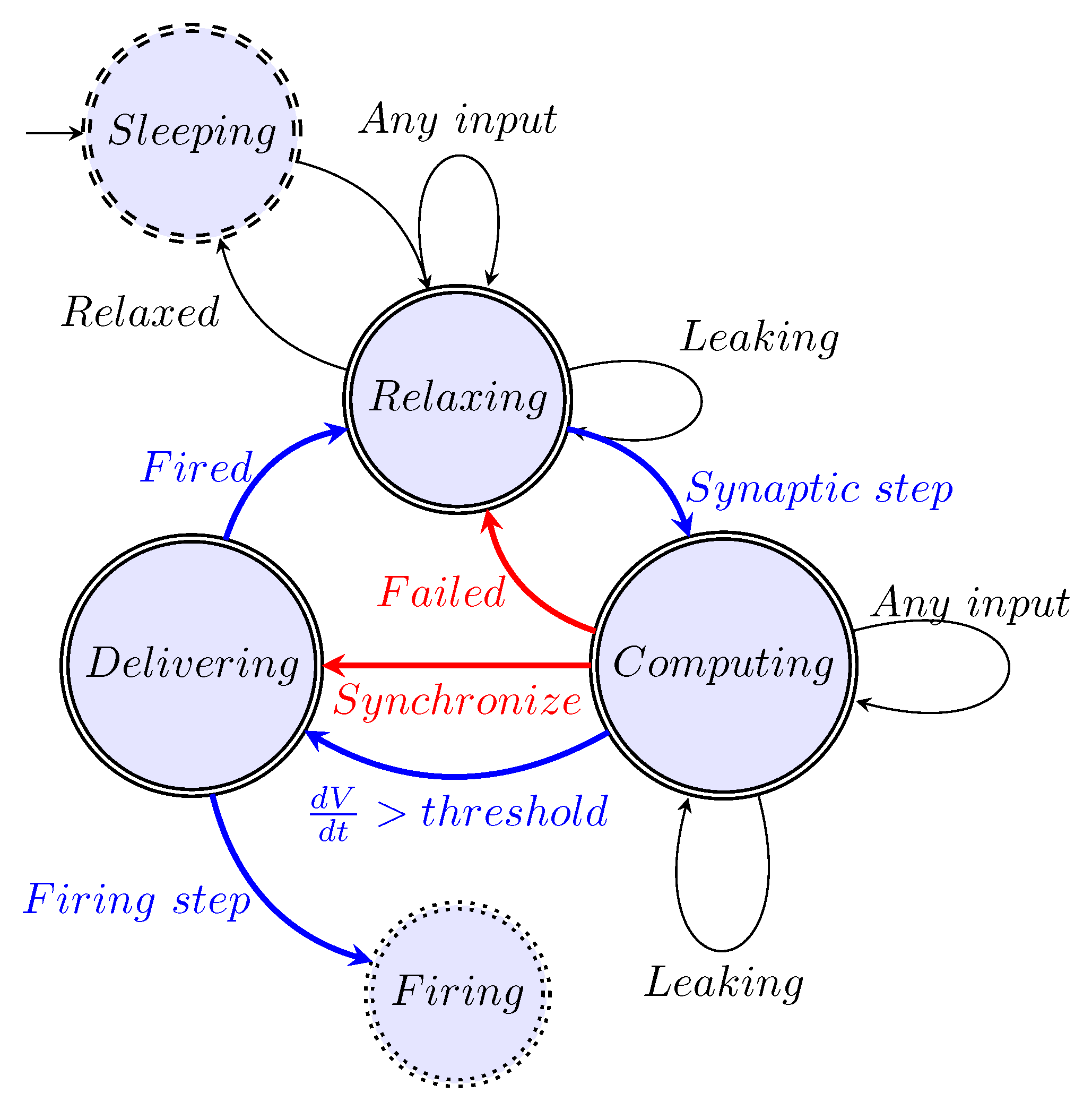

Figure 3.

How the physical processes describe membrane’s operation. The rushed-in

ions instantly increase the membrane’s charge, and then the membrane’s capacity discharges (producing an exponentially decaying voltage derivative). The ions are created at different positions on the membrane, so they take different times to reach the AIS, where the current produces a peak in the voltage derivative.The resulting voltage derivative —the sum of the two derivatives (since the AIS current is outward) —drives the oscillator. Its integration produces the membrane potential.When the membrane potential reaches the threshold voltage, it switches the synaptic currents off or on. (Figure 11 from [

10]).

4.2. Stage Machine

Figure 2 illustrates our abstract view of a neuron, in this case, as a "stage machine". The double circles are

stages (

states with event-defined periods and internal processing) connected by bent arrows representing

instant stage transitions. At the same time, at some other abstraction level, we consider them

processes that have a temporal course with their

event handling. Fundamentally, the system circulates along the blue pathway and maintains its state (described by a single stage variable, the membrane potential) using the black loops. However, sometimes it takes the less common red pathways. It receives its inputs cooperatively (controls the accepted amount of its external inputs from the upstream neurons by gating them by regulating its stage variable). Furthermore, it actively communicates

the time of its state change (

not its state as assumed in the so-called neural information theory) toward the downstream neurons.

In any stage, a "leaking current" (see Eq. (

3)) changing the stage variable is present;

the continuous change (the presence of a voltage gradient) is fundamental for a biological computing system. This current is proportional to the stage variable (membrane current); it is

not identical to the fixed-size "leaking current" assumed in the Hodgkin-Huxley model [

74]. The event that is issued when stage "Computing" ends and "Delivering" begins separates two physically different operating modes: inputting payload signals for computing and inputting "servo" ions for transmitting (signal transmission to fellow neurons begins and happens in parallel with further computation(s)).

The neuron receives its inputs as ’Axonal inputs’. For the first input in the ’Relaxing’ stage, the neuron enters the ’Computing’ stage. The time of this event becomes the base time used for calculating the neuron’s "local time". Notice that to produce the result, the neuron cooperates with upstream neurons (the neuron gates its input currents). One of the upstream neurons opens computing, and the receiving neuron terminates it.

The figure also reveals one of the secrets of the marvelous efficiency of neuronal computing. The dynamic weighting of the synaptic inputs, plus adding the local memory content, happens analog, per synapse, and the summing happens at the jointly used membrane. The synaptic weights are not stored for an extended period. It is more than a brave attempt to accompany (in the sense of technical computing) a storage capacity to this time-dependent weight and a computing capacity to the neuron’s time measurement.

4.2.1. Stage ’Relaxing’

Initially, a neuron is in the ’Relaxing’ stage, which is the ground state of its operation. In this stage, the neuron (re-)opens its synaptic gates. (We also introduce a ’Sleeping’ (or ’Standby’) helper stage, which can be imagined as a low-power mode [

75] in the electronic or state maintenance mode of biological computing or "creating the neuron" in biology, a "no payload activity" stage.) The stage transition from "Sleeping" also

resets the internal stage variable (the membrane potential) to the value of the resting potential. In biology, a "leaking" background activity takes place: it changes (among others) the stage variable toward the system’s "no activity" value.

The ion channels generating an intense membrane current are closed. However, the membrane’s potential may differ from the resting potential. The membrane voltage plays the role of an accumulator (with a time-dependent content): a non-zero initial value acts as a short-term memory in the subsequent computing cycle. A new computation begins (the neuron passes to the stage ’Computing’) when a new axonal input arrives. Given that the computation is analog, a current flows through the AIS and the result is the length of the period to reach the threshold value. The local time is reset when a new computing cycle begins, but not when eventually the resting potential is reached. Notice that the same stage control variable plays many roles: the input pulse writes a value into the memory (the synaptic inputs generate voltage increment contributions which decay with time, so the different decay times set a per-channel memory value while simultaneously the weighted sum is calculated).

4.2.2. Stage ’Computing’

The neuron receives its inputs as ’Axonal inputs’. For the first input in the "Relaxing" stage, the neuron enters the "Computing" stage. The time of this event is the base time used for calculating the neuron’s "local time". Notice that to produce the result, the neuron cooperates with upstream neurons (the neuron gates its input currents). One of the upstream neurons opens computing, and the receiving neuron terminates it.

The figure also reveals one of the secrets of the marvelous efficiency of neuronal computing. The dynamic weighting of the synaptic inputs, plus adding the local memory content, happens analog, per synapse, and the summing happens at the jointly used membrane. The synaptic weights are not stored for an extended period. It is more than a brave attempt to accompany (in the sense of technical computing) a storage capacity to this time-dependent weight and a computing capacity to the neuron’s time measurement.

While computing, a current flows out from the neuronal condenser, so

the arrival time of its neural input charge packets (spikes) matters. All charges arriving when the time window is open increase or decrease the membrane’s potential. The neuron has memory-like states [

76] (implemented by different biophysical mechanisms). The computation can be restarted, and its result also depends on the actual neural environment and neuronal sensitivity. Although the operation of neurons can be described when all factors are known, because of the enormous number of factors and their time dependence (including ’random’ spikes), it is much less deterministic (however, not random!) than the technical computation.

The inputs considered in the computation (those arriving within the time window), their weights and arrival times change dynamically between the operations. On the one hand, this change makes it hard to calculate the result; on the other hand, it is accompanied by the learning mechanism, it enables the implementation of higher-order neural functionality, such as redundancy, rehabilitation, intuition, association, etc. Constructing solid electrolytes enables the creation of artificial synapses [

77], and many biological facilities in reach, with the perspective of having a thousand times faster neurons, provide facilities for getting closer to the biological operation.

The external signal triggers a stage change and simultaneously contributes to the value of the internal stage variable (membrane voltage). During regular operation, when the stage variable reaches a critical value (the threshold potential), the system generates an event that passes to the "Delivering" stage and "flushes" the collected charge. In that stage, it sends a signal toward the environment (to the other neurons connected to its axon). After that period, it passes to the "Relaxing" stage without resetting the stage variable. From this event on, the "leaking" and the input pulses from the upstream neurons contribute to its stage variable.

4.2.3. Stage ’Delivering’

In this stage, the result is ready: the time between the arrival of the first synaptic input and reaching the membrane’s threshold voltage was already measured. No more input is desirable, so the neuron closes its input synapses. Simultaneously, the neuron starts its ’servo’ mechanism: it opens its ion channels, and an intense ion current starts to charge the membrane. The voltage on the membrane quickly rises, and it takes a short time until its peak voltage is reached. The increased membrane voltage drives an outward current, and the membrane voltage gradually decays. When the voltage drops below the threshold voltage, the neuron re-opens its synaptic inputs and passes to the stage ’Relaxing’: it is ready for the next operation. The signal transmission to downstream neurons happens in parallel with the recent "Delivering" stage and the subsequent "Relaxing" (and maybe "Computing") stages.

The process "Delivering" operates as an independent subsystem ("Firing" ): it happens simultaneously with the process of "Relaxing", which, after some period, usually passes to the next "Computing" stage.

The stages "Computing" and "Delivering" mutually block each other, and the I/O operations happen in parallel with them. They have temporal lengths, and they must follow in the well-defined order "Computing"⇒" Delivering"⇒"Relaxing" (a "proper sequencing" [

23]). Stage "Delivering" has a fixed period, stage "Computing" has a variable period (depends mainly on the upstream neurons), and the total length of the computing period equals their sum. The (physiologically defined) length of the "Delivering" period limits the neuron’s firing rate; the length of "Computing" is usually much shorter.

4.2.4. Extra Stages

There are two more possible stage transitions from the stage "Computing". First, the stage variable (due to "leaking") may approach its initial value (the resting potential), and the system passes to the " Relaxing" stage; in this case, we consider that the excitation Failed. This happens when the leaking is more intense than the input current pulses (the input firing rate is too low, or a random firing event started the computing). Second, an external pulse [

78] “Synchronize” may have the effect of forcing the system (independently from the value of the stage variable) to pass instantly to the "Delivering" stage and, after that, to the "Relaxing" stage. (When several neurons share that input signal, they will go to the "Relaxing" stage simultaneously: they get synchronized, a simple way of synchronizing low-precision asynchronous oscillators.)

4.2.5. Synaptic Control

As discussed, controlling the operation of its synapses is a fundamental aspect of neuronal operation. It is a gating and implements an ’autonomous cooperation’ with the upstream neurons. The neuron’s gating uses a ’downhill method’: while the membrane’s potential is above the axonal arbor’s (at the synaptic terminals), the charges cannot enter the membrane. When the membrane’s voltage exceeds the threshold voltage, the synaptic inputs stop and restart only when the voltage drops below that threshold again; see the top inset of

Figure 3. The synaptic gating makes interpreting neural information and entropy [

6] at least hard.

4.2.6. Timed Cooperation of Neurons

The length of the axons between the neurons and the conduction velocity of the neural signals entirely define the time of the data transfer (in the millisecond range); all connections are direct. The transferred signal starts the subsequent computation as well (asynchronous mode). "A preconfigured, strongly connected minority of fast-firing neurons form the backbone of brain connectivity and serve as an ever-ready, fast-acting system. However, the full performance of the brain also depends on the activity of very large numbers of weakly connected and slow-firing majority of neurons." [

79]

In biology, the inter-neuronal transfer time is much longer than the neuronal processing time. Within the latter, the internal delivery time ("forming a spike") is much longer than the computing (collecting charge from the presynaptic neurons) itself. Omitting the computing time aside from transmission time would be a better approximation than the opposite, as included in the theory.

The arguments and the result are temporal; the neural processing is analog and event-driven [

39].

Synaptic charges arrive when the time window is open, or artificial charges increase or decrease the membrane’s potential. A neuron has memory-like states [

76], see also

Figure 1 (implemented by different biophysical mechanisms). The computation can be restarted, and its result also depends on the actual neural environment. When all factors are known, the operation can be described. However, because of the enormous number of factors, their time dependence, the finite size of the neuron’s components, and the finite speed of ions (furthermore, their interaction while traveling on the dendrites), it is much less deterministic (however, not random!) than the technical computation. We learned that it is hard to describe the neuron’s behavior mathematically and to model it electronically. The inputs considered (those arriving within the time window) in the computation, their weights, and arrival times change between the operations, making it hard to calculate the result on the one hand. On the other hand (accompanied by the learning mechanism), it enables the implementation of higher-order neural functionality, such as intuition, association, redundancy, and rehabilitation.

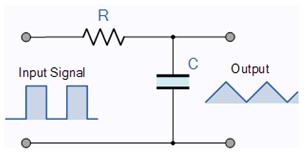

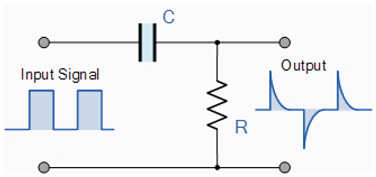

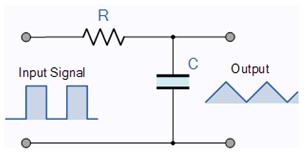

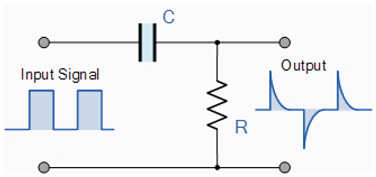

4.4. Mathematics of Spiking

The so-called equivalent circuit of the neuron is a differentiator-type

oscillator circuit [

10,

80,

94] as proved by direct neuroanatomical evidence [

71,

81,

82,

83,

84] (it is erroneously claimed in biophysics that it is an integrator-type oscillator; it is true only for the resting state). The corresponding circuits, their filtering ability, signal forms, and the mathematical form of their description are shown in

Table 1. These circuits assume, among others, ’instant interaction’, discrete (non-distributed) electrical components, ideal wires, electrons as charge carriers, constant battery voltage, constant capacitance, constant resistance, and no thermodynamic consequence effects. Neither of them is (strictly) valid for biological circuits. However, these classical circuits are closest to them. The synaptic currents can increase the membrane’s voltage above its threshold, so an intense current starts that suddenly increases the membrane’s voltage to a peak voltage, and then the condenser discharges through the

circuit. The circuit produces a damped oscillation, and after a longer time, the membrane voltage returns to its resting value. While the membrane’s voltage is above its threshold value, the synaptic inputs are inactive (the analog inputs are gated).

|

|

| The RC Integrator |

The RC differentiator |

|

|

| Low Pass Filter |

High Pass Filter |

|

|

Although using an "equivalent circuit" is not perfect for biological circuits, in our model, the neuron is represented as a constant capacity condenser and a constant resistance . The charge carriers are slow (typically positive) ions, which are about 50,000 times heavier than electrons (furthermore, they cannot form a "free ion cloud"), while the electrostatic force between the carriers is the same as in the case of electrons. Due to the slow ions, the "instant interaction" model used in the theory of electricity cannot be used. The ions can move only using the “downhill” method (toward decreasing potential), but the potential must be interpreted as the sum of the electric and thermodynamic potentials.

Concerning

Figure 1, given that slow ion currents deliver the charge on the membrane’s surface, the charge propagation takes time, and so after the charge-up process, the synaptic inputs reach the output of the circuit about tenths of a millisecond later. Their arrival (the voltage gradients they produce) provides input for the next computing cycle. A potential that resides above the resting potential implements a neuron-level memory.

Although the implementation of a neuronal circuit works with ionic currents with many differences, the operation can align (to some measure) with the instant currents of physical electronics when using current generators of special form. The input currents in a biological circuit is the sum of a large rush-in current through the membrane in an extremely short time and much smaller gated synaptic currents arriving at different times through the synapses. Those currents generate voltage gradients, and the output voltage measured on the output resistor is

The figures were generated using

and

. In our ’net’ electric model, it is easy to modify the parameters in steps of solving the differential equation. Note that this solution enables one to take into account the changes in the electric parameters due to mechanical and thermodynamic effects [

85,

94]. The input voltage gradients are voltage-gated; the logical condition is

(the temporal gating, see also Eq.(

7) and

Figure 3, is implemented through voltage gating). The sum of the input gradients that the currents generate, plus the voltage gradient of the output current generates through the AIS [

71,

84]. The latter term can be described as

That is

According to Eq.(

1), the circuit sums up all derivatives of the gradients, including the one the oscillator generates through the AIS. So a composite signal appears at the output resistor (not to mention that the synaptic inputs are gated: they are not effective during the stage ’Delivering’). This differentiator circuit natively produces positive and negative voltages for rising and falling edges of the input voltages. For the resting state, the ’no gradient’ case, of course, produces ’no output voltage’. According to Eq.(

3), the voltage drop on the AIS is proportional to the voltage above the resting state, so there is no ’leakage current’ in the resting state; with far-reaching biological consequences [

94]. In the transient state, the integrating effect of the condenser forms the output signal to behave as ’polarized’ and ’hyperpolarized’ parts of the neural signal (see the bottom inset in

Figure 3), without needing to hypothesize any current in the opposite direction. It is a native feature of the correct

sequential circuit; the

parallel circuit cannot produce similar behavior and requires ad hoc non-physical hypotheses.

The input currents (although due to slightly differing physical reasons for the different current types) are usually described by an analytic form

where

is a current amplitude per input,

and

are timing constants for current in- and outflow for the given contributing current, respectively. They are (due to geometrical reasons) approximately similar for the synaptic inputs and differ from the constants valid for the rush-in current. The corresponding voltage derivative is

To implement such an analog circuit with a conventional electronic circuit, voltage-gated current injectors (with time constants of around

) are needed. Notice that the currents have a range of validity of interpretation as described. The input (synaptic) currents are interpreted only in "Computing"; the rush-in current flows only from the beginning of "Delivering" while the outward current (see Eq.(

3)) is persistent but depends on the membrane’s potential.

In the simplest case, the resulting voltage derivative comprises only the rush-in contribution described by Eq (

6) and the AIS contribution described by Eq. (

3). The gating implements a dynamically changing temporal window and dynamically changing synaptic weights. The appearance of the first arriving synaptic gradient starts the “Computing” stage. The appearance of the rush-in gradient starts the “Delivering” stage. The charge collected in that temporal window is

The total charge is integrated in a mathematically entirely unusual way: the upper limit depends on the result. Notice that artificial neural networks (including "spiking neural networks") entirely overlook this point: Notice that artificial neural networks (including "spiking neural networks") entirely overlook this point: integration is continuous (all summands are used), and the result reduces to a logical variable. Also, it is not considered that the AIS current decreases the membrane’s voltage and charge between incoming spikes.

This omission also has implications for the algorithm. The only operation that a neuron can perform is that unique integration. It is implemented in biology by gating the inputs to the computing units, as shown in Eq.(

2). In the "Computing" stage, synaptic inputs are open; in the "Delivering" stage, they are closed (the inputs are ineffective). It produces multiple outputs (in the sense that the signal may branch along its path) in the form of a signal with a temporal course. Although it has many (several thousand) inputs, a neuron uses only about a dozen of them in a single computing operation, appropriately and dynamically weighting and gating its inputs [

79].

The result of the computation is the reciprocal of the weighted sum, and it is represented by the time when a spike is sent out (

when that charge on the membrane’s fixed capacity leads to reaching the threshold). Any foreign (artificial, such as clamping) current influences the rate of charge collection and, therefore, the

value; its time course also contributes to the overall gradient. The neuron (through the integration time window) selects which ones out of its upstream neurons can contribute to the result. The individual contributions are a bargain between the sender and the receiver: the neuron decides when a contributing current terminates, but an upstream neuron decides when it begins.

The beginning of the time window is set by the arrival of a spike from one of the upstream neurons, and it is closed by the neuron when the charge integration results in a voltage exceeding the threshold. The computation (a weighted summation) is performed on the fly, excluding the obsolete operands. (The idea of AIMC [

86] almost precisely reproduces the charge summation except for its timing.)

Figure 3 (resulted by our simulator [

80]) shows how the described physical processes control a neuron’s operation. In the middle inset, when the membrane’s surface potential, see Eq.(

1), increases above its threshold potential due to three step-like excitations opens the rush-in ion channels instantly (more details in [

10,

80]), and creates an exponentially decreasing, step-like voltage derivative that charges up the membrane. The step-like imitated synaptic inputs resemble the real ones: the synaptic inputs produce smaller, rush-in-resemblant (see Figure 10 in [

87]), voltage gradient contributions. When integrated as Eq. (

1) describes the resulting voltage gradient that produces the Action Potential (AP) shown in the lower inset. Crossing the threshold level controls the gating signal. as shown in the top inset.

Notice how nature implemented "in-memory computing" by weighted parallel analog summing. The idea of AIMC [

86] quite precisely reproduced the idea, except that it uses a "time of programming", instead of the "time of arrival" the biological system uses. The "time of programming" depends on technical transfer characteristics. In general, that time is measured on the scale of computing time rather than simulated time.

Notice nature’s principles of reducing operands and noise: the less important inputs are omitted by timing. The rest of the signals are integrated over time. The price paid is a straightforward computing operation: the processor can perform only one type of operation. Its arguments, result, and neuronal-level memory are all time-dependent. Furthermore, the operation excludes all but (typically) a dozen neurons from the game. It is not necessarily the case that the same operands, having the same dynamic weights, are included in consecutive operations. It establishes a chaotic-like operation [

88] at the level of the operation of neuronal assemblies [

48,

72,

89], but also enables learning, association, rehabilitation, and similar functionalities. Since the signal’s shape is identical, integrating them in time means multiplying them by a weight (depending non-linearly on time), and the deviation from the steady-state potential represents a (time-dependent) memory. The significant operations, the dynamic weighting, and the dynamic summing are performed strictly in parallel. There are attempts to use analog or digital accelerators (see [

86,

90]), but they work at the expense of degrading either the precision or the computing efficiency. Essentially, this is why, from the point of view of technical computation, “we are between about 7 and 9 orders of magnitude removed from the efficiency of mammalian cortex” [

35].

4.6. Operating Diagrams

Figure 3 (produced by the simulator) shows how the described physical processes control a neuron’s operation. In the middle inset, when the membrane’s surface potential increases above its threshold potential due to three step-like excitations opening the ion channels,

ions rush in instantly and create an exponentially decreasing, step-like voltage derivative that charges up the membrane. The step-like imitated synaptic inputs are reminiscent of the real ones: the incoming Post-Synaptic Potential (PSP)s produce smaller, rush-in-resemblant, voltage gradient contributions. The charge creates a thin surface layer current that can flow out through the AIS. This outward current is negative and proportional to the membrane potential above its resting potential. In the beginning, the rushed-in current (and correspondingly, its potential gradient contribution) is much higher than the current flowing out through the AIS, so for a while, the membrane’s potential (and so: the AIS current) grows. When they get equal, the AP reaches its top potential value. Later, the rush-in current gets exhausted, and its potential-generating power drops below that of the AIS current; the resulting potential gradient changes its sign, and the membrane potential starts to decrease.

In the previous period, the rush-in charge was stored on the membrane. Now, when the potential gradient reverses, the driving force starts to decrease the charge in the layer on the membrane, which, by definition, means

a reversed current; without foreign ionic current through the AIS. This is a

fundamental difference between the static picture that Hodgkin and Huxley hypothesized [

74]

and biology uses, and the dynamic one that describes its behavior. The microscopes’ resolution enabled one to discover AIS only two decades after their time; their structure and operation could be studied only three more decades later [

71]. In the past two decades, it has not been built into the theory of neuronal circuits. The correct equivalent electric circuit of a neuron is a serial oscillator in the transient state, and a parallel oscillator in the resting state (see [

10,

80]), and its output voltage in the transient state is defined dynamically by its voltage gradients instead of static currents (as physiology erroneously assumes). In the static picture, the oscillator is only an epizodist, while in the time-aware (dynamic) picture, it is a star.

Notice also that only the resulting Action Potential Time Derivative (APTD) disappears with time. Its two terms are connected through the membrane potential. As long as the membrane’s potential is above the resting value, a current of variable size and sign will flow, and the output and input currents are not necessarily equal: the capacitive current changes the game’s rules.

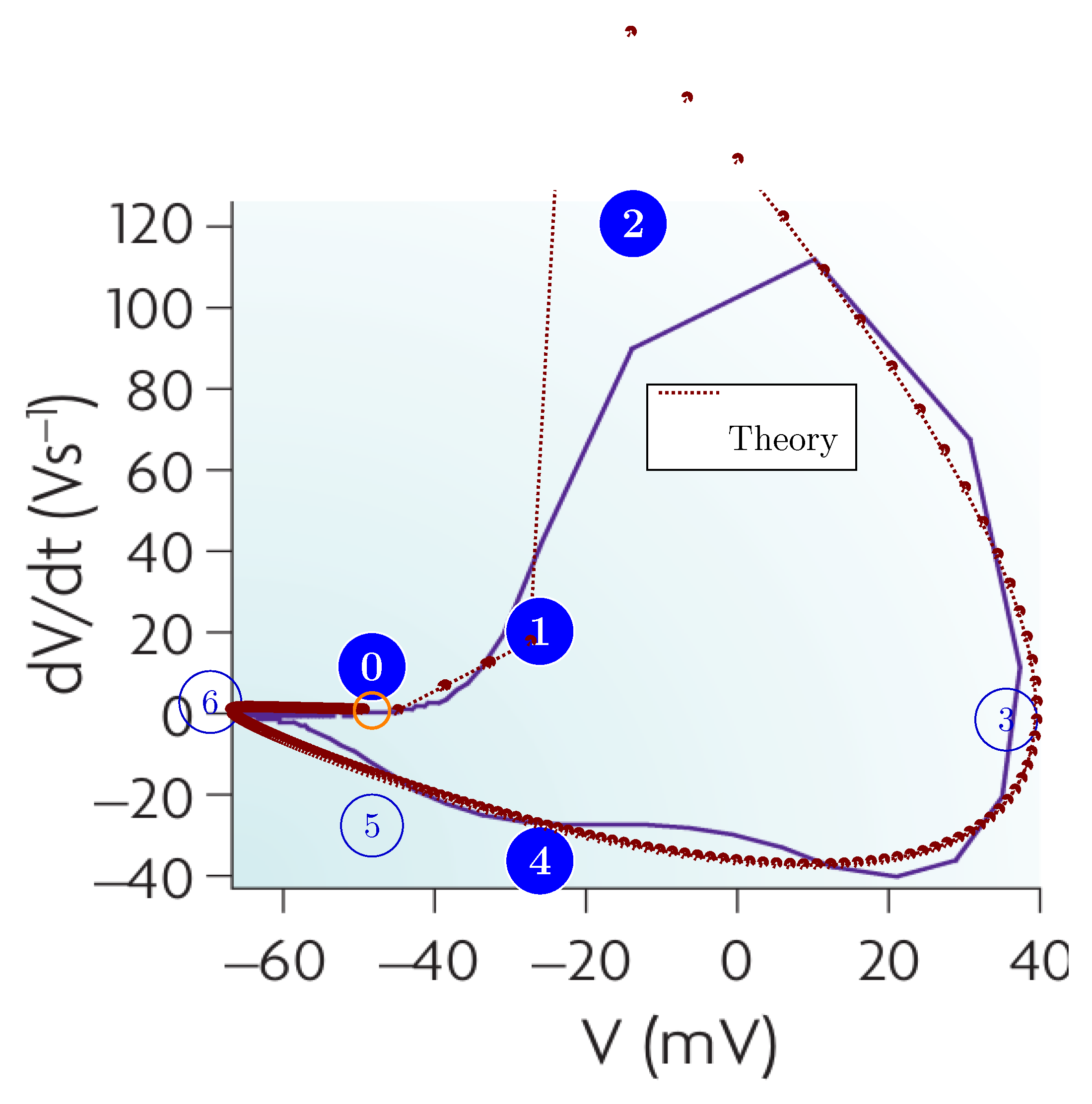

Figure 4 (resulting from our simulator [

80]) shows the phase diagram between the membrane’s potential and its voltage gradient, compared to the measured diagram from [

91],

Figure 2.d. In this parametric figure, the time parameter is derived from both experimental and simulated data. The sampling base distance is not equidistant in time. On the blue experimental line, the measurement times are marked by joint broken-line segments. On the red theoretical diagram line, the marks indicate the points where the simulated value was calculated (the time is adjusted to the actual gradient). As discussed, the improper measurement periods act as averaging over improperly selected time intervals. On the right side of the figure, the broken line, although rough, properly follows the time course of the theoretical diagram line. The measurement periods are slightly above the optimal, around 0.1 milliseconds. However, this is not the case in the middle of the figure. Here, the time distance of the sampling points is about

, and the rush-in of the

ions causes a drastically different gradient value. This fine time resolution enables us to track the effect, whereas the "long" measurement resolution period yields an improper average and masks the effect that drives neuronal operation. The effect clearly demonstrates the need for a gradient-aware algorithm and an integration step; furthermore, it shows that voltage gradients control neuronal operation.

The top inset shows how the membrane potential controls the synaptic inputs. Given the ions from the neuronal arbor [

92,

93] can pass to the membrane using the ’downhill’ method, but they cannot do so if the membrane’s potential is above the threshold. The upper diagram line shows how this gating changes in time’s function.

Figure 4.

The diagram describing the Action Potential in the

phase diagram. A parametric figure showing the correspondence between the membrane’s potential, see Eq. (

1) and its gradient, see Eq. (

3). The theory’s diagram line perfectly describes the experimental data (see [

91], Figure 2.d) where the distance between the sampling data points is adequate.

Figure 4.

The diagram describing the Action Potential in the

phase diagram. A parametric figure showing the correspondence between the membrane’s potential, see Eq. (

1) and its gradient, see Eq. (

3). The theory’s diagram line perfectly describes the experimental data (see [

91], Figure 2.d) where the distance between the sampling data points is adequate.

4.7. Implications of the Model and the Algorithm

All former models and simulators lack a proper physical basis.As Hodgkin and Huxley (HH) correctly noted, the physical picture they had tentatively in mind when they attempted to give meaning to their mathematical equations describing their observations was wrong. Their followers never attempted to validate or replace the mechanisms they hypothesized; only different mathematical formulas were suggested to have fewer (or just another) contradictions with the observations. No other simulator works with a correct physical background. They parametrize some mathematical functions, but they lack the physical processes underlying them. Neither of those parameters can be described from the first principles/ scientific laws.

The concept of scalability has different readings when speaking about different times and different compositions of processing and communication times. The net computing activity grows linearly with the number of simulated neurons. SystemC is based on single-thread, user-level scheduling (although there are extensions for taking advantage of operating system (OS)-level multi-threading). This way it avoids using time-wasting I/O instructions, system-level processor and thread scheduling.

A neuron operates in tight cooperation with its environment (the fellow neurons, with outputs distributed in space and time). We must never forget that "the basic structural units of the nervous system are individual neurons" [

17], but neurons "are linked together by dynamically changing constellations of synaptic weights" and "cell assemblies are best understood in light of their output product" [

6,

72]. To understand the operation of their assemblies and higher levels, we must provide an accurate description of single-neuron operation. Unlike the former models and algorithms, Eq.(

7) expresses this observation, called ’synaptic plasticity’. Neurons process information autonomously, but in cooperation with their environment. They receive multiple inputs at different offset times from different upstream neurons at different stages. The earliest input defines the beginning of the time window, and the neuron (based on the result of the analog integration) defines the end of the time window. The time window defines the synaptic weight used in the operation for received synaptic inputs. Not only the synaptic weights but also the contributors may change from cycle to cycle. Unlike any former model or mathematical formula, our model natively explains synaptic plasticity, and the algorithm can implement it.

Learning is a very complex mechanism, and nature uses time windows of different widths (ranging from fractions of a millisecond to minutes) to implement it. Although not fully discussed, some hints are given by the author in [

10] (and will be given in forthcoming papers). The paper did not intend to define such features. The present model deals with the elementary operation of a single neuron, although it mentions one possible implementation of memory.

"Synaptic interactions" is a concept that is the consequence of the concept of ’instant interaction’. Synaptic inputs, which provide parallel contributions in biology, and are processed by analog parallel computing units, can only be handled by sequential processing in technical computing. This way, technical implementations unavoidably work with values of different time arguments when handling different inputs. To avoid that, the implementation must "freeze" the time. In our perfectly timed implementation, we use a simulated biological time scale. We use "intended" time, and truly simultaneous events that are independent from the technical implementation, actual workload, and so on. In non-perfect implementations, either a linear mapping is tacitly assumed or a timestamp (containing a wall-clock time or processor-clock time) attempts to "freeze" the time, always comprising distortions from foreign computing activities. This means that when imitating biological activity by processing sequentialized parallel input, the ’instant interaction’ algorithm must somehow correct for the (non-biological) effect. A fictitious method must consider that the other inputs somehow (that "will happen at the same time, but not yet processed") distorts the result. Synapses are one-way objects; their interactions are parallel in biology, and some artefact had to be created to simulate their sequential imitation.