Submitted:

08 January 2025

Posted:

09 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

The human brain is a marvel of evolutionary engineering, a system of astonishing complexity and efficiency. Its ability to process vast amounts of information and withstand disruptions is largely due to the elaborate networks of neurons and synapses. The efforts of modern science to replicate this natural efficiency through the development of artificial neural systems is, in essence, an attempt to externalize and actualize the implicit potential of nature’s order. This challenge has long eluded traditional computational models. Artificial Neural Networks despite their sophistication, are energy-intensive and cumbersome, requiring vast amounts of memory and processing power to account for the temporal variability of events that unfold over varying durations and intensities. These systems, while useful, often fall short of capturing the full complexity of nature’s patterns. Enter Spiking Neural Networks, a new class of bio-inspired models that draw directly from the brain’s way of processing information. Unlike conventional neural networks, which operate continuously, SNNs rely on discrete spikes, closely mimicking the time-based behavior of biological neurons. This ability to handle time-varying information efficiently mirrors the brain’s rhythms and offers a more energy-conscious solution to understanding dynamic systems.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

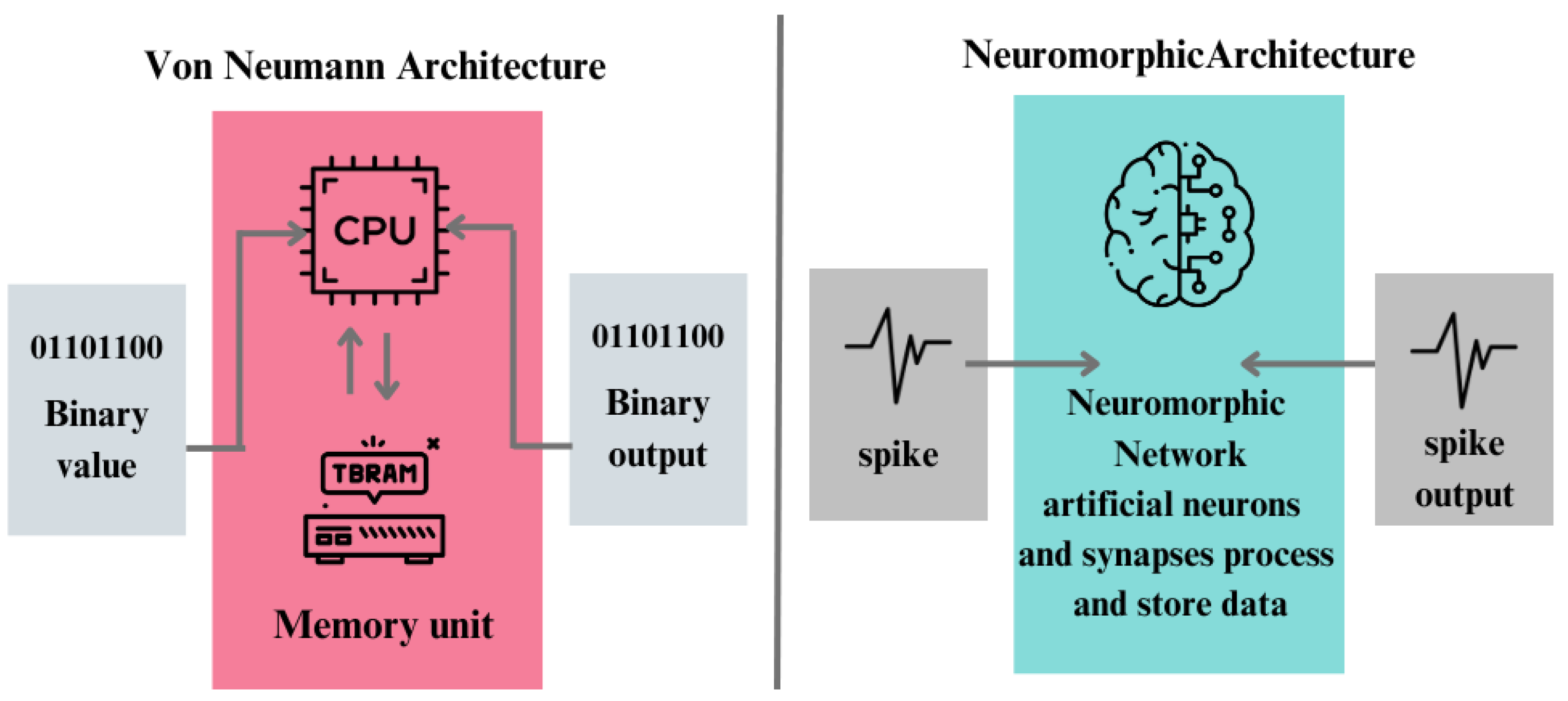

2. Neuromorphic Computing vs Biological Neuromorphic Systems

- Neuromorphic sensors: By imitating the structure and function of neurons in electronic devices, neuromorphic engineering opens up a new avenue for research into brain design. The goal of this effort is to use the brain’s effective computing architecture for next-generation artificial systems. This method is exemplified by neuromorphic microchips, which mimic biological sensing and spike-based neural processing to enable nervous system-like event-driven computing. Mostly silicon-based, these devices use transistors to simulate brain circuits because of similar physics, which makes computational primitives easier to implement. The address-event representation (AER), which transmits spikes together with address and timing information off-chip to enable flexible connection and low-latency event-driven computing, is essential to their operation ([14]). Event-based neuromorphic vision sensors offer low energy consumption, low latency, high dynamic range, and high temporal resolution, revolutionizing visual sensing in autonomous vehicles ([20]).

- Neuromorphic software: The current AI algorithms diverge significantly from the complexities of biological neurons and synapses. Biological neurons exhibit traits beyond simple non-linear functions; they spike, possess leakiness, memory, stochasticity, and the ability to oscillate and synchronize. Moreover, they are spatially extended, with distinct functional compartments integrating signals from various areas. Similarly, biological synapses are more than analog weights; they function as leaky memories with diverse time scales and state parameters governing their modifications. Some synapses are highly stochastic, transmitting only a fraction of received spikes. Often overlooked components of the brain, such as dendrites and astrocytes, and are also necessary in neural computation and regulation. Integrating these nuanced properties into artificial neural networks is what constitutes neuroporphic software ([21]).

- Neuromorphic hardware:The rise of deep networks and recent corporate interest in brain-inspired computing has sparked widespread curiosity in neuromorphic hardware, which aims to mimic the brain’s biological processes using electronic components. The potential of neuromorphic hardware lies in its ability to implement computational principles with low energy consumption, employing the intrinsic properties of materials and physical effects. Initially pioneered by Carver Mead, this field focused on exploiting transistor leakage current’s exponential dependence on voltage. In recent years, researchers have utilized a variety of physical phenomena to mimic synaptic and neuronal properties. Neuromorphic hardware systems offer novel opportunities for neuroscience modeling, benefiting from parallelism for scalable and high-speed neural computation. However, despite the emerging memory technologies, such as flash memory and solid-state memory, that are enabling neuromorphic computing and bio-inspired learning algorithms like back-propagation, there’s a gap between the communities of software simulator users and neuromorphic engineering in neuroscience. ([22,23]).

3. Applications of SNNs

-

Event-based Vision Sensors

- –

- In recent years, researchers have combined event-based sensors with spiking neural networks (SNNs) to develop a new generation of bio-inspired artificial vision systems. These systems demonstrate real-time processing of spatio-temporal data and boast high energy efficiency. [24] utilized a hybrid event-based camera along with a multi-layer spiking neural network trained using a spike-timing-dependent plasticity learning rule. Their findings indicate that neurons autonomously learn from repeated and correlated spatio-temporal patterns, developing selectivity towards motion features like direction and speed in an unsupervised manner. This motion selectivity can then be harnessed for predicting ball trajectories by using a simple read-out layer consisting of polynomial regressions and trained under supervision. Thus, their study illustrates the capability of an SNN, coupled with inputs from an event-based sensor, to extract pertinent spatio-temporal patterns for processing and predicting ball trajectories.

- –

- [25] propose a fully event-based image processing pipeline integrating neuromorphic vision sensors and spiking neural networks (SNNs) to enable efficient vision processing with high throughput, low latency, and wide dynamic range. Their approach focuses on developing an end-to-end SNN unsupervised learning inference framework to achieve near-real-time processing performance. By employing fully event-driven operations, they significantly enhance learning and inference speed, resulting in over a 100-fold increase in inference throughput on CPU and near-real-time inference on GPU for neuromorphic vision sensors. The event-driven processing method supports unsupervised spike-timing-dependent plasticity learning of convolutional SNNs, enabling higher accuracy compared to supervised training approaches when labels are limited. Furthermore, their method enhances robustness for low-precision SNNs by reducing spiking activity distortion, leading to higher learning accuracy compared to regular discrete-time simulated low-precision networks.

- –

- [26] introduce Dynamic Vision Sensors (Event Cameras) for gait recognition, offering advantages like low resource consumption and high temporal resolution. To address challenges posed by their asynchronous event data, a new approach called Event-based Gait Recognition (EV-Gait) is proposed. This method utilizes motion consistency to remove noise and employs a deep neural network for gait recognition from event streams.

- –

- [27] introduce the neuromorphic vision sensor as a novel bio-inspired imaging paradigm capable of reporting asynchronous per-pixel brightness changes known as ’events’ with high temporal resolution and dynamic range. While existing event-based image reconstruction methods rely on artificial neural networks or hand-crafted spatiotemporal smoothing techniques, this paper pioneers the implementation of image reconstruction via a deep spiking neural network architecture. Leveraging the computational efficiency of SNNs, which operate with asynchronous binary spikes distributed over time, the authors propose a novel Event-based Video reconstruction framework based on a fully Spiking Neural Network (EVSNN), using Leaky-Integrate-and-Fire (LIF) and Membrane Potential (MP) neurons. They observe that spiking neurons have the potential to retain useful temporal information (memory) for completing time-dependent tasks.

-

Bioinformatics

- –

- Spiking neural networks (SNNs) are beginning to impact biological research and biomedical applications due to their ability to integrate vast datasets, learn arbitrarily complex relationships, and incorporate existing knowledge. Already, SNN models can predict, with varying degrees of success, how genetic variation alters cellular processes involved in pathogenesis, which small molecules will modulate the activity of therapeutically relevant proteins, and whether radiographic images are indicative of disease. However, the flexibility of SNNs creates new challenges in guaranteeing the performance of deployed systems and in establishing trust with stakeholders, clinicians, and regulators, who require a rationale for decision making. We argue that these challenges will be overcome using the same flexibility that created them; for example, by training SNN models so that they can output a rationale for their predictions. Significant research in this direction will be needed to realize the full potential of SNNs in biomedicine [28].

- –

- Because interactions are important in biological processes, such as protein interactions or chemical bonds, this data is often represented as biological networks. The proliferation of such data has spurred the development of new computational tools for network analysis. [29] explore various domains in bioinformatics where NNs are commonly applied, including protein function prediction, protein-protein interaction prediction, and in silico drug discovery. They highlight emerging application areas such as gene regulatory networks and disease diagnosis, where deep learning serves as a promising tool for tasks like gene interaction prediction and automatic disease diagnosis from data. By extension, SNNs could be a great alternative to deep learning in these domains.

- –

- As biotechnology advances and high-throughput sequencing becomes prevalent, researchers now possess the capability to generate and analyze extensive volumes of genomic data. Given the large scale of genomics data, many bioinformatics algorithms rely on machine learning techniques, with recent emphasis on deep learning, to uncover patterns, forecast outcomes, and characterize disease progression or treatment [30]. The progress in deep learning has sparked significant momentum in biomedical informatics, leading to the emergence of novel research avenues in bioinformatics and computational biology. Deep learning models offer superior accuracy in specific genomics tasks compared to conventional methodologies, using SNNs in these domain could prove to be a great alternative.

-

Neuromorphic Robotics

- –

- Initially, robots were developed with the primary objective of simplifying human life, particularly by undertaking repetitive or hazardous tasks. While they effectively fulfilled these functions, the latest generation of robots aims to surpass these capabilities by engaging in more complex tasks traditionally executed by intelligent animals or humans. Achieving this goal necessitates drawing inspiration from biological paradigms. For instance, insects demonstrate remarkable proficiency in solving complex navigation challenges within their environment, prompting many researchers to emulate their behavior. The burgeoning interest in neuromorphic engineering has motivated the presentation of a real-time, neuromorphic, spike-based Central Pattern Generator (CPG) applicable in neurorobotics, using an arthropod-like robot as a model. A Spiking Neural Network was meticulously designed and implemented on SpiNNaker to emulate a sophisticated, adaptable CPG capable of generating three distinct gaits for hexapod robot locomotion. Reconfigurable hardware facilitated the management of both the robot’s motors and the real-time communication interface with the SNN. Real-time measurements validate the simulation outcomes, while locomotion trials demonstrate that the NeuroPod can execute these gaits seamlessly, without compromising balance or introducing delays. ([?])

-

Brain-Computer Interfaces

- –

- [31] claim that Brain-Inspired Spiking Neural Network (BI-SNN) architectures offer the potential to extract complex functional and structural patterns over extensive spatio-temporal domains from data. Such patterns, often represented as deep spatio-temporal rules, present a promising avenue for the development of Brain-Inspired Brain-Computer Interfaces (BI-BCI). The paper introduces a theoretical framework validated experimentally, demonstrating the capability of SNNs in extracting and representing deep knowledge. In a case study focusing on the neural network organization during a Grasp and Lift task, the BI-BCI successfully delineated neural trajectories of visual information processing streams and their connectivity to the motor cortex. Deep spatiotemporal rules were then utilized for event prediction within the BI-BCI system. This computational framework holds significance in uncovering the brain’s topological intricacies, offering potential advancements in Brain-Computer Interface technology.

-

Space Domain Awareness

- –

- With space debris posing significant threats to space-based assets, there is an urgent need for efficient and high-resolution monitoring and prediction methods. This study presents the outcomes of the NEU4SST project, which explores Neuromorphic Engineering, specifically leveraging event-based visual sensing combined with Spiking Neural Networks (SNNs), as a solution for enhancing Space Domain Awareness (SDA). The research focuses on event-based visual sensors and SNNs, which offer advantages such as low power consumption and precise high-resolution data capture and processing. These technologies enhance the capability to detect and track objects in space, addressing critical challenges in the Space domain. [32] propose an approach with potential to enhance SDA and contribute to safer and more efficient space operations. Continued research and development in this field are essential for unlocking the full potential of Neuromorphic engineering for future space missions.

4. Fundamentals of Spiking Neural Networks

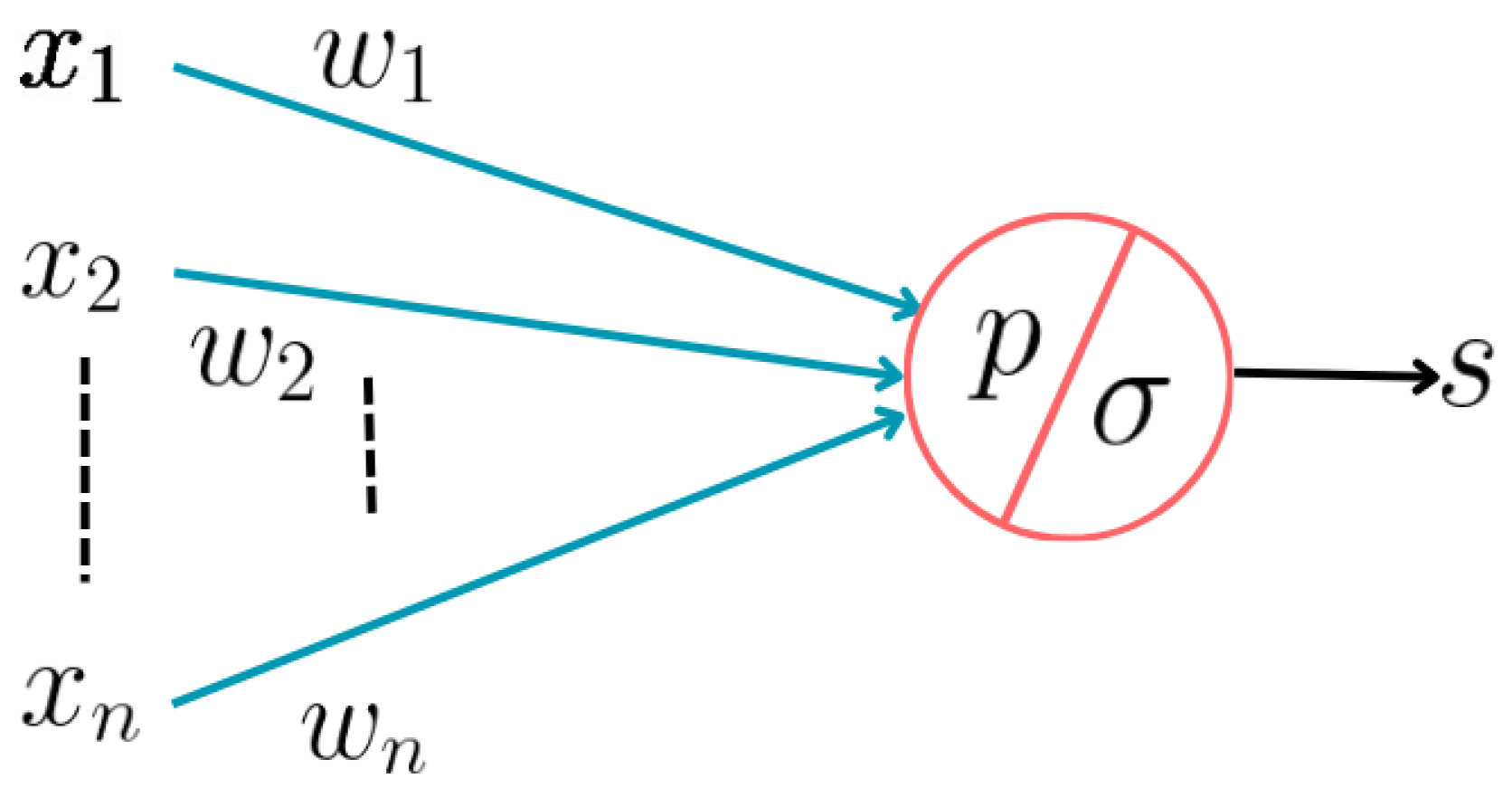

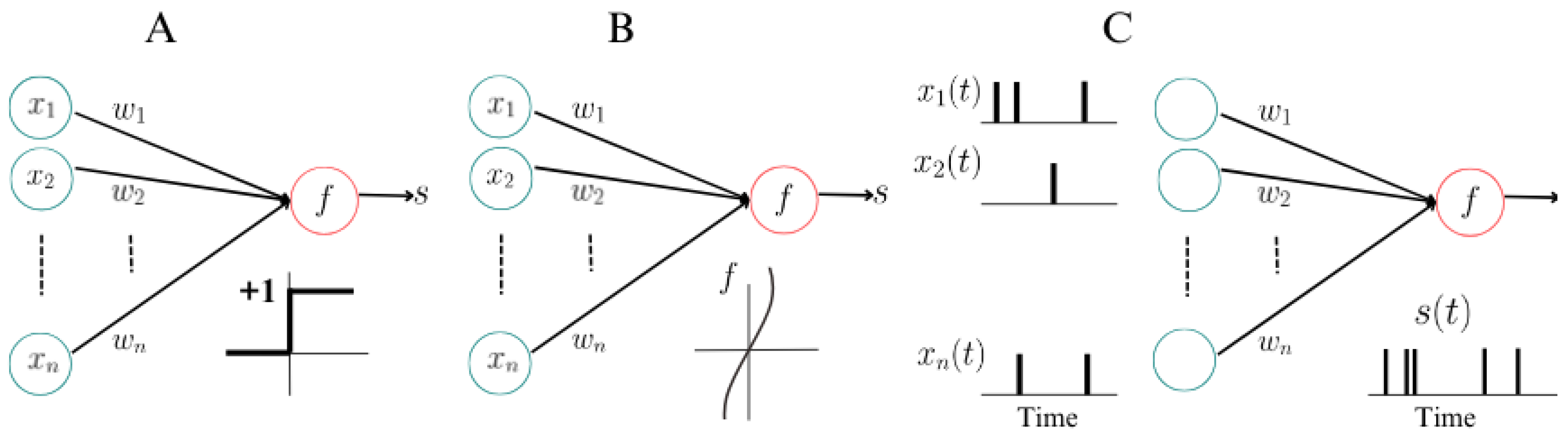

- First Generation: Starting from their examination of key neuronal characteristics, McCulloch and Pitts aimed to represent the functional framework rather than the physical structure of neurons, essential for their functioning. They delineated five key functions: stimulus reception , stimulus weighting (synaptic coefficients , computation of the weighted stimulus sum , establishment of a stimulation threshold for transmission initiation, and stimulus output , as seen in Figure 2. Their model emphasizes the sequential arrangement of these functions, focusing only on their conceptual representation rather than the integration of factors fulfilling these functions. It’s important to note that this model represents abstract functions rather than observable phenomena, lacking any depiction of the neuronal cell’s internal material structure, which contributes to explaining the neuronal response to stimuli ([34]). Examples include multilayer perceptrons, Hopfield nets, and Boltzmann machines. They are universal for computations with digital input and output and can compute boolean functions.

- Second Generation: Computational units apply activation functions with a continuous set of possible output values to a weighted sum of inputs. This generation includes feedforward and recurrent sigmoidal neural nets, as well as networks of radial basis function units. They can compute boolean functions with fewer gates than first-generation models and handle analog input and output.

- Third Generation: This generation employs spiking neurons, or integrate-and-fire neurons, as computational units, inspired by experimental evidence indicating that many biological neural systems use the timing of single action potentials to encode information. These models reflect acumen from neurobiology research and aim to capture the timing of neural spikes for information processing.

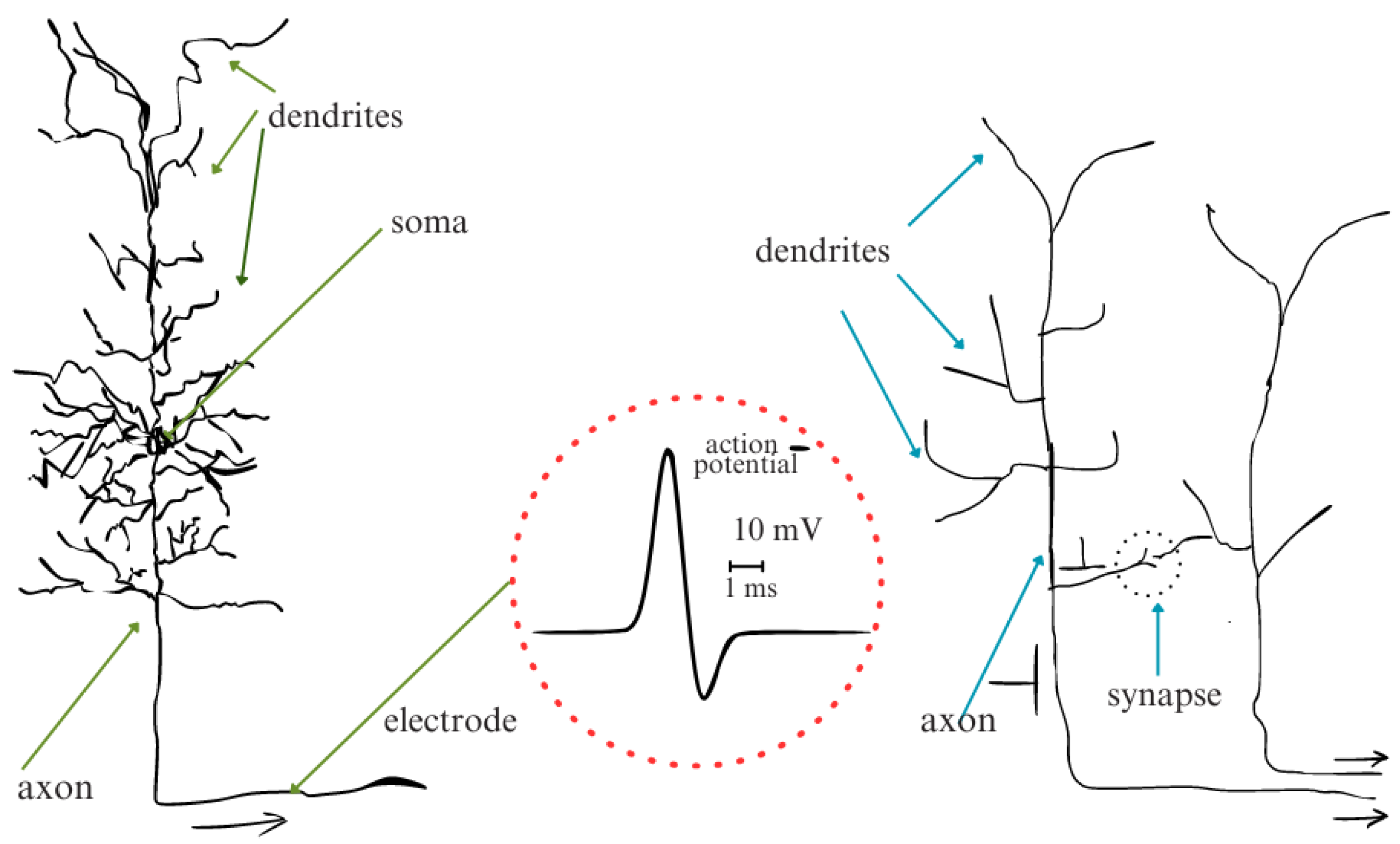

4.1. Spiking Neurons

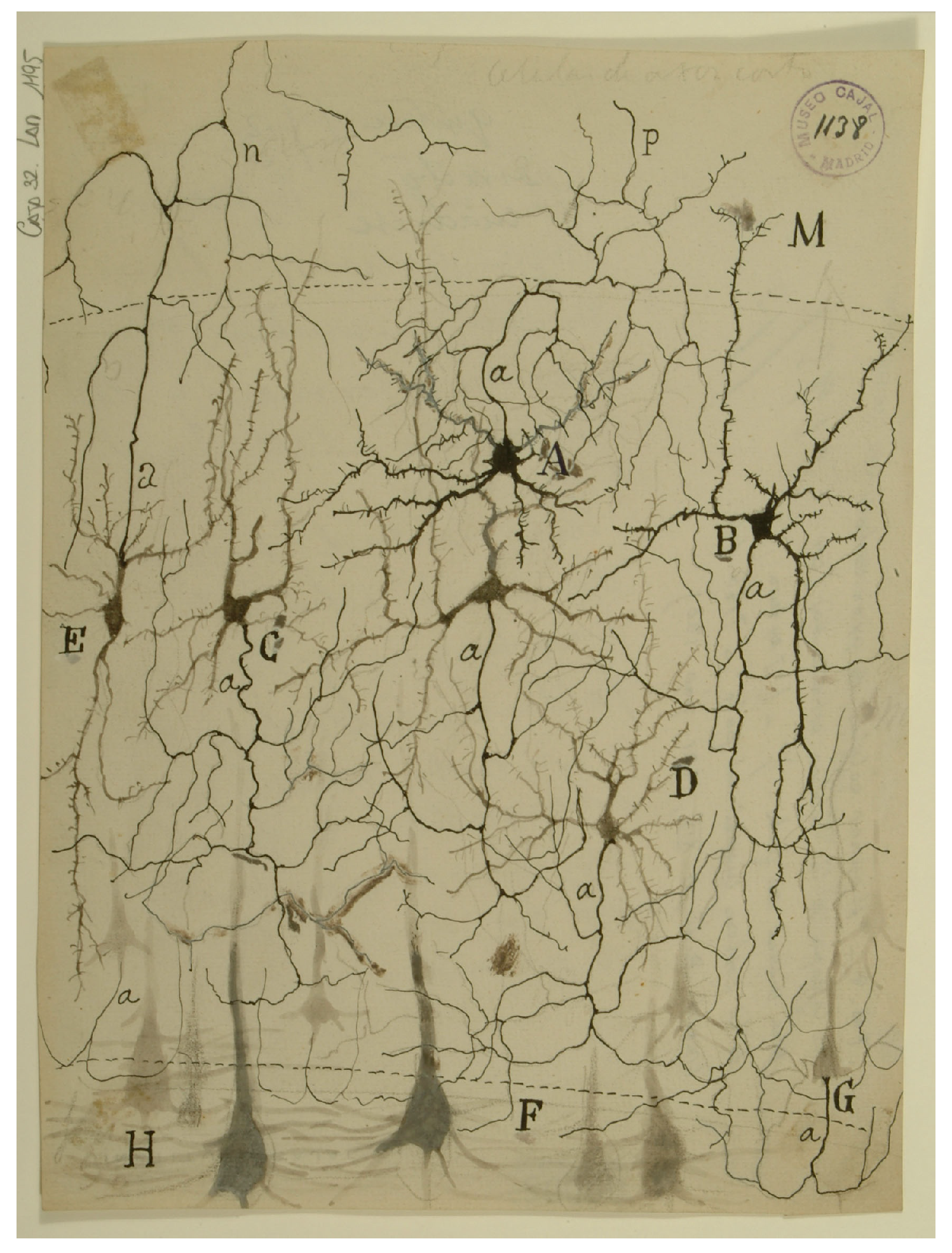

4.2. Biological Neuron Model

4.2.1. Neuronal Elements

4.2.2. The Synapse

4.2.3. Networks of Neurons

4.2.4. Postsynaptic Potentials

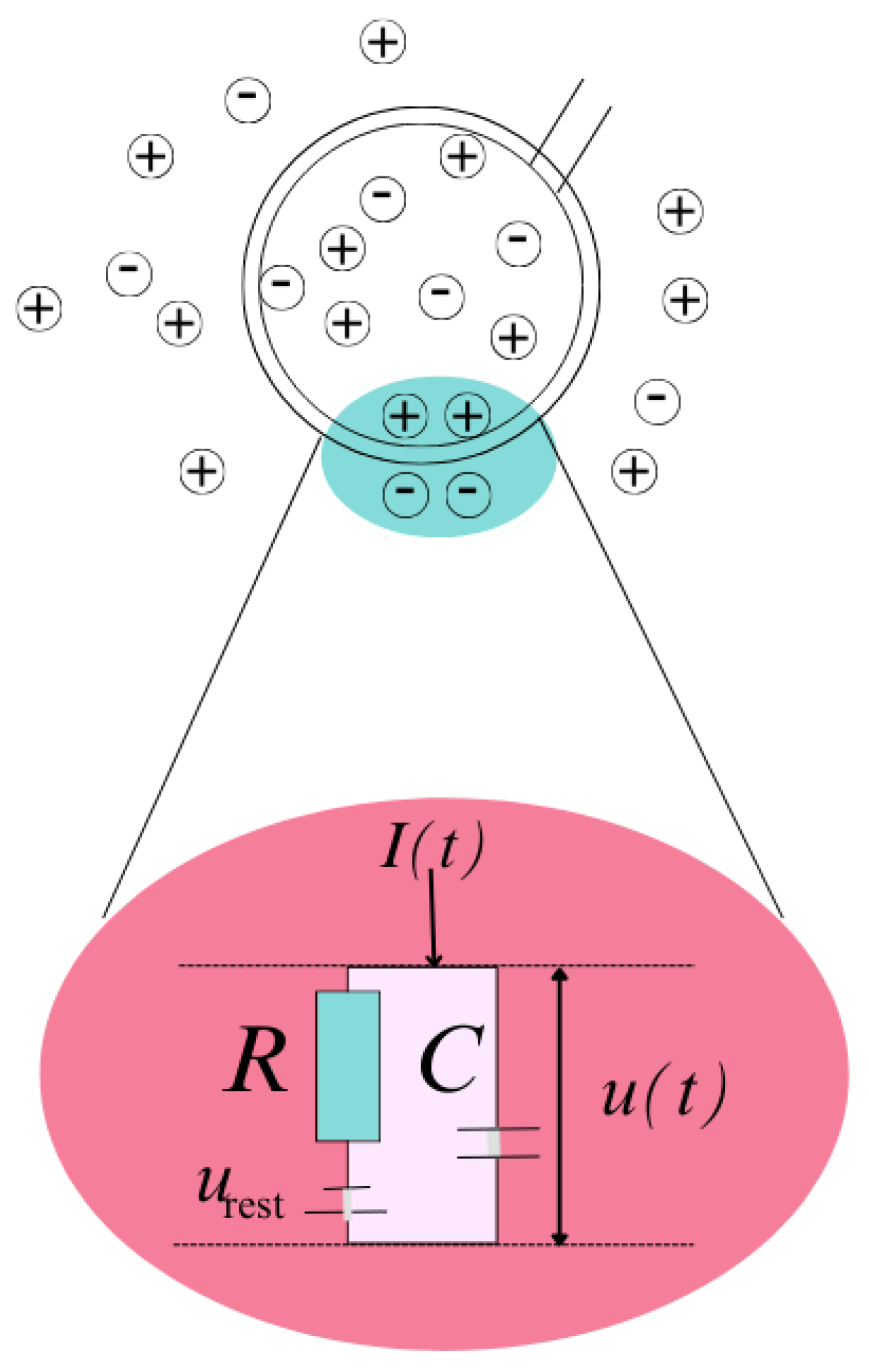

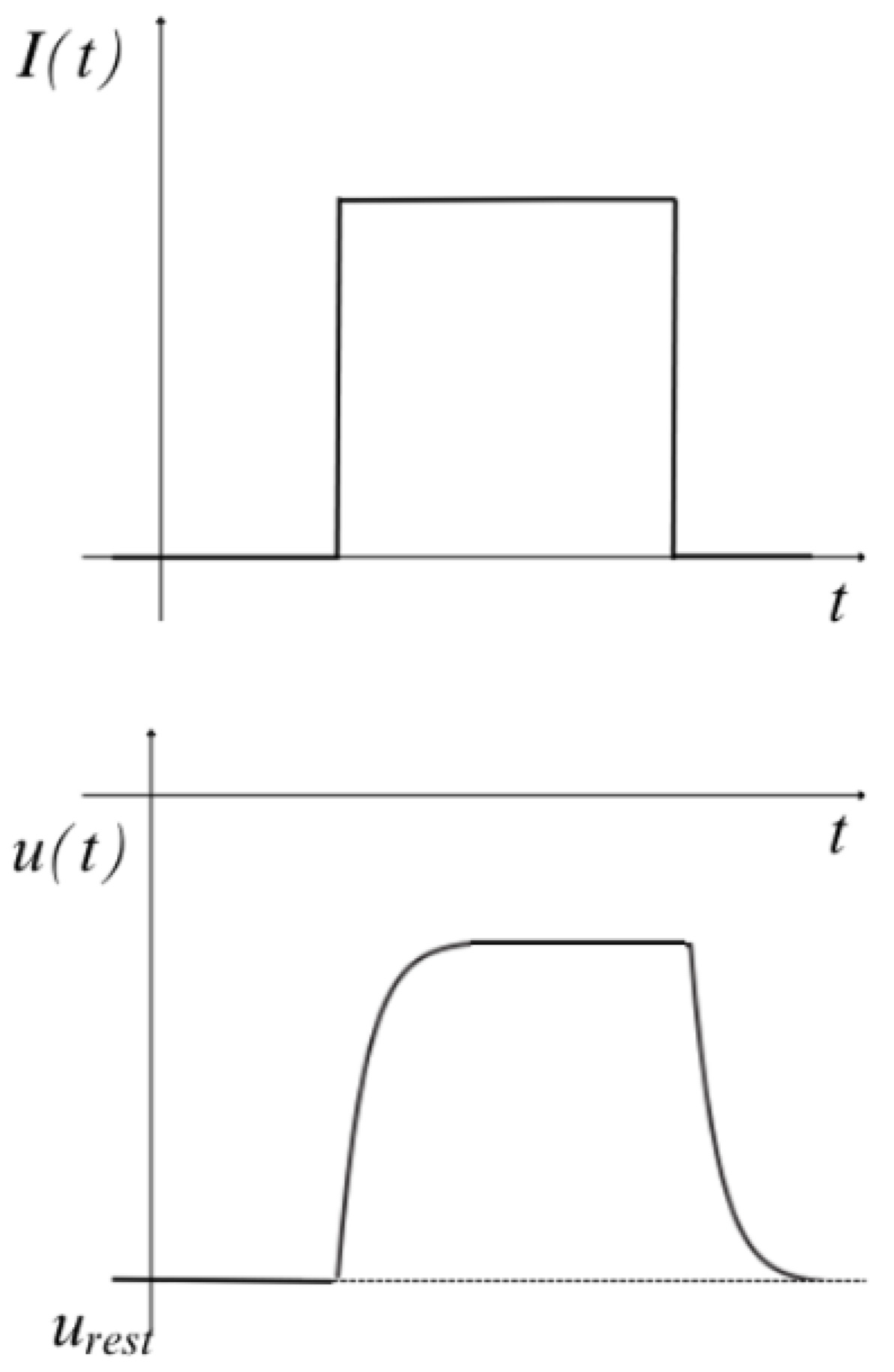

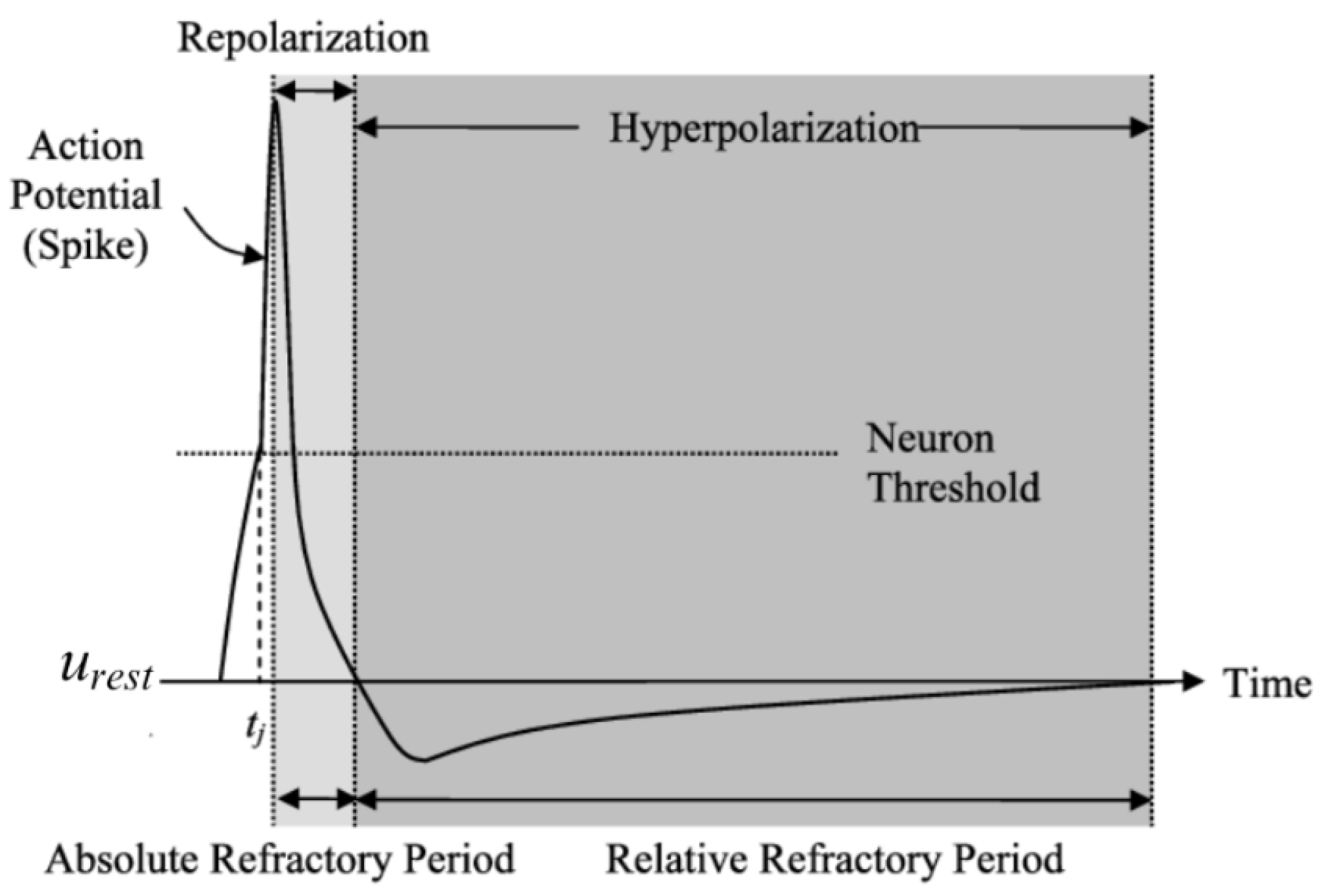

4.2.5. Integrate and Fire Model

- a differential equation that describes the evolution of the membrane potential

- a threshold that defines the point where the membrane potential becomes a "fired" state

4.2.6. Electrical Theory Principles

4.2.7. The Threshold for Spike Firing

4.2.8. Limitations of LIF Model

- Integration of inputs is linear and independent of the state of the receiving neurons.

- No memory of previous spikes is retained after a spike generation. Let’s examine these limitations and how they will be resolved in the extended leaky integrate-and-fire model.

- Being deterministic, LIF neurons fail to capture the stochastic behavior inherent in biological neurons, leading to an oversimplification of neural activity.

- The input current is assumed to be linear, which means that the response (the integrate-and-fire potential) is determined only by the value of the stimulus and not by the history of previous stimuli ([40]).

- The model does not capture the slow processes in the neuron that are responsible for input adaptation (changes in membrane conductances).

- The membrane Potential is always reset to the same value after a spiking event, irrespective of the state of the neuron.

- LIF neurons struggle to accurately reproduce detailed spiking dynamics, such as adaptation and bursting, limiting their applicability in certain contexts.

- The spatial structure of the cell, including the nonlinear interactions between different branches of the cell, is not taken into account.

- The neurons are not just isolated but embedded into a network and receive multiple inputs from other neurons across all their synapses. If a few inputs arrive on the same branch of the neuron within a few milliseconds (ms), the first input triggers a change in the membrane potential that could affect the response to the subsequent inputs. This kind of non-linear response can also lead to saturation or amplification of the response depending on the kind of currents that are involved.

- The LIF neuron model describes the membrane potential of a neuron, but does not include the actual changes in membrane voltage and conductances driving the action potential ([54].

4.2.9. Other Models

4.2.10. Spike Encoding and Decoding

- 1)

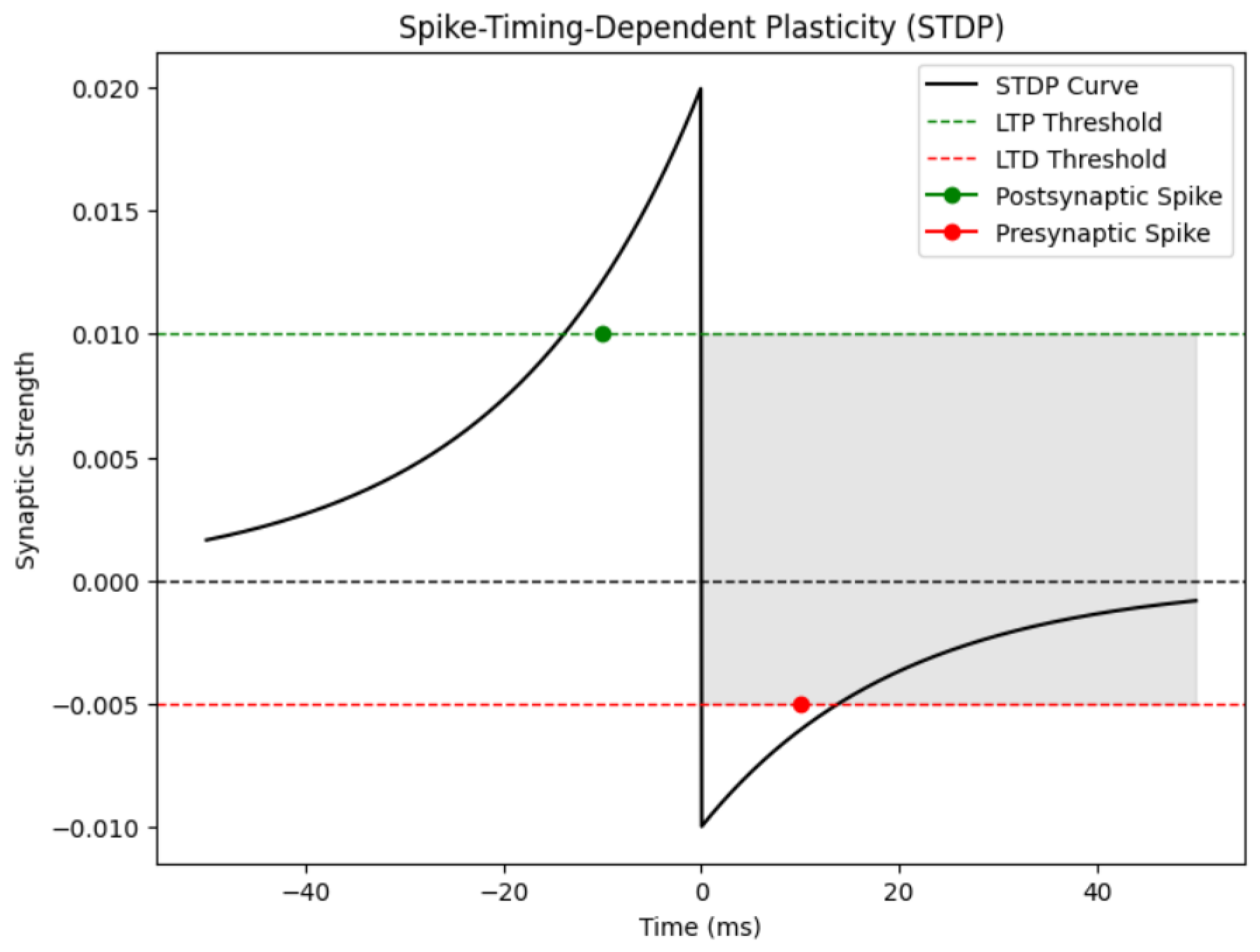

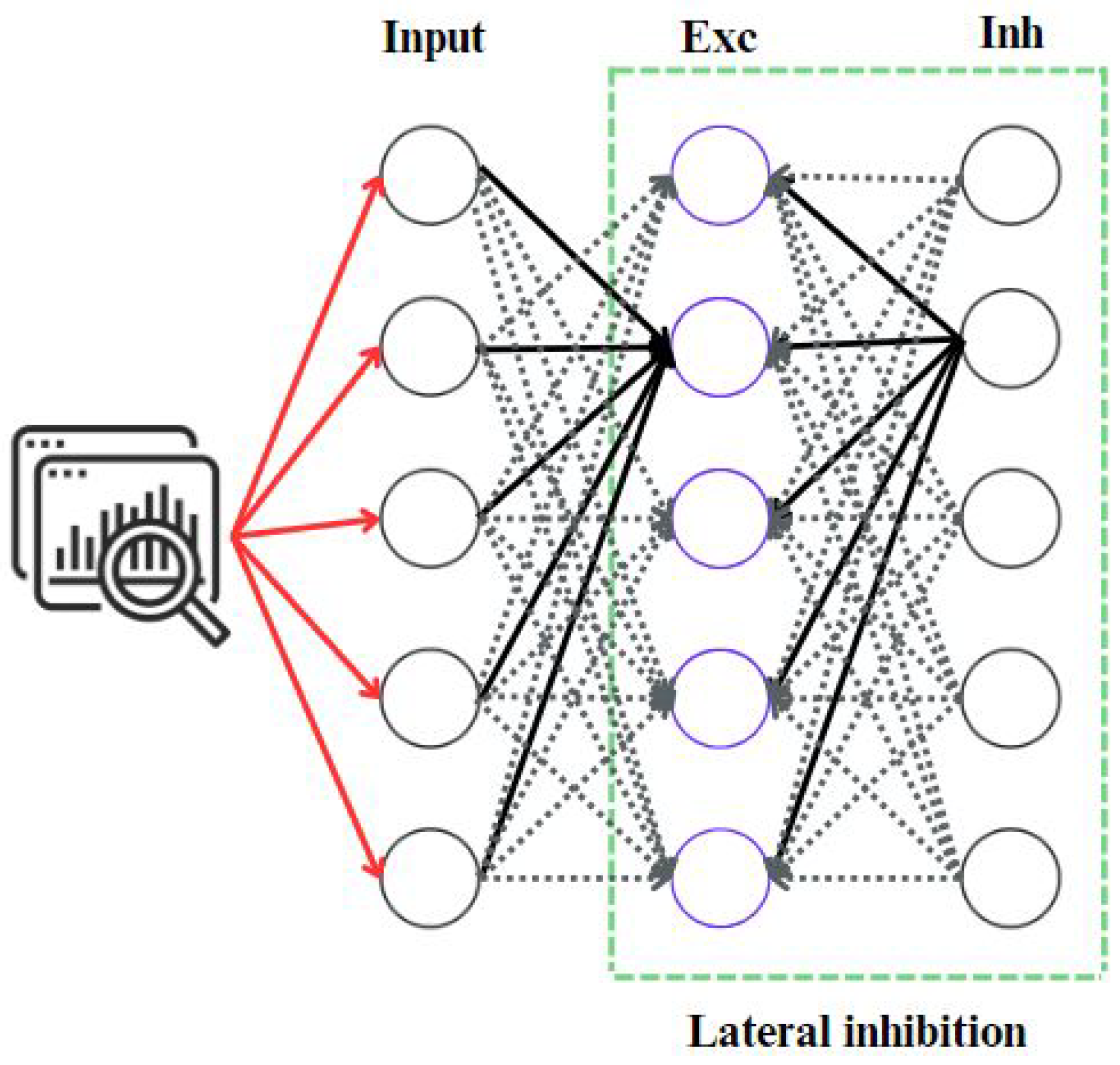

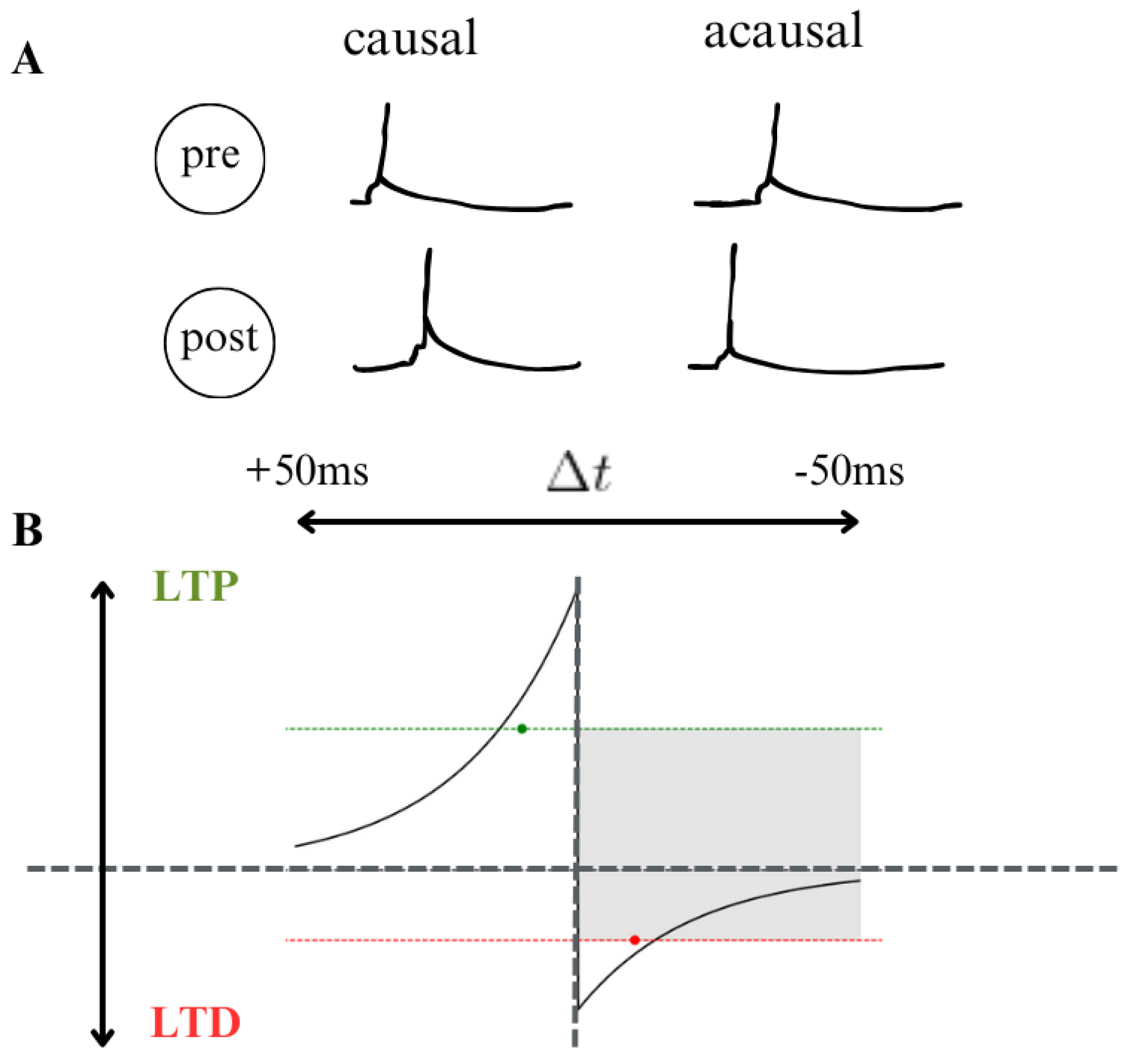

- Spike Timing Dependent: Electrical activity plays an important role in shaping the structure and function of neural circuits over an organism’s lifespan ([71,72]). Changes in sensory experiences that disrupt normal patterns of activity can lead to significant remodeling of neural networks and alterations in neural response properties. Learning and memory processes are also thought to rely on activity-dependent modifications in neural circuits. Recent discoveries regarding spike timing-dependent plasticity (STDP) have garnered significant interest among researchers and theorists, particularly in understanding cell type-specific temporal windows for long-term potentiation (LTP) and long-term depression (LTD). Beyond the conventional correlation-based Hebbian plasticity, STDP offers new avenues for exploring information encoding, circuit plasticity, and synaptic learning mechanisms. Key questions arise regarding the dependence of activity-induced modifications at GABAergic synapses on the precise timing of pre and postsynaptic spiking, the presence of STDP in neuronal excitability and dendritic integration, and the impact of complex neuronal spiking patterns, including high-frequency bursts, on STDP. Additionally, researchers seek to elucidate how STDP influences the operation of neural circuits and higher brain functions, such as sensory perception. Understanding the cellular mechanisms underlying such functional plasticity has been a longstanding challenge in neuroscience ([73]). Hebb’s influential postulate on the cellular basis of learning proposed that repeated or persistent activation of one neuron by another leads to structural or metabolic changes that enhance the efficiency of synaptic transmission between them([74]). Experimental findings supporting this postulate came with the discovery of long-term potentiation (LTP), initially observed in the hippocampus and later identified in various neural circuits ([75]), including cortical areas, the amygdala, and the midbrain reward circuit ([76,77]). LTP is typically induced by high-frequency stimulation of presynaptic inputs or by pairing low-frequency stimulation with strong postsynaptic depolarization. Conversely, long-term depression (LTD) is induced by low-frequency stimulation, either alone or paired with mild postsynaptic depolarization ([78,79]). Together, LTP and LTD enable bidirectional modification of synaptic strength in an activity-dependent manner, making them plausible candidates for the synaptic basis of learning and memory. In other studies, the induction of LTP and LTD has been found to be influenced by specific types of neural activity ([80]). See Figure 10.

- 2)

- Phase Encoding: Phase encoding refers to a neural coding strategy where information is represented not only by the number of spikes (spike count) but also by the precise timing of spikes relative to the phase of ongoing network oscillations. In the study conducted on the primary visual cortex of anesthetized macaques, researchers found that neurons encoded rich naturalistic stimuli by aligning their spike times with the phase of low-frequency local field potentials (LFPs). The modulation of both spike counts and LFP phase by the presented color movie indicated that they reliably conveyed information about the stimulus. Particularly, movie segments associated with higher firing rates also exhibited increased reliability of LFP phase across trials. Comparing the information carried by spike counts to that carried by firing phase revealed that firing phase conveyed additional information beyond spike counts alone. This extra information was used for distinguishing between stimuli with similar spike rates but different magnitudes. Thus, phase encoding allows primary cortical neurons to represent multiple effective stimuli in an easily decodable format, enhancing the brain’s ability to process and interpret sensory information. [81] explored the concept of phase encoding in neural responses to visual stimuli by analyzing the relationship between spike times and the phase of ongoing local field potential (LFP) fluctuations. The research involved recording neural signals in the primary visual cortex of anesthetized macaques while presenting a color movie. The power of the LFP spectrum was found to be highest at low frequencies (<4 Hz) during movie presentation, indicating the modulation of LFP phase by the visual stimulus. To investigate the potential encoding of information beyond spike count, the study examined the phase at which spikes occurred relative to LFP fluctuations. By labeling spikes based on their phase quadrant, the researchers sought to predict visual features more effectively than through spike counts alone. Results suggested that phase coding could enhance stimulus discrimination, especially in scenarios where spike rates were comparable. Analysis of LFP-phase reliability and spike-phase relationships demonstrated the potential of phase-of-firing coding to convey additional information about visual stimuli. The study utilized Shannon information analysis to quantify the amount of information conveyed by spike times relative to LFP phase. Results indicated that phase-of-firing coding in the 1–4 Hz LFP band provided 54% more information about the movie compared to spike counts alone. This finding suggests that phase encoding may play a significant role in representing visual information in the primary visual cortex, offering a novel perspective beyond traditional spike-count coding. Increasing evidence suggests that ongoing oscillations’ phases are necessary in neural coding, yet their overall importance across the brain remains unclear. [82] investigated single-trial phase coding in eight distinct regions of the human brain —four in the temporal lobe and four in the frontal lobe—by analyzing local field potentials (LFPs) during a card-matching task. Our findings reveal that in the temporal lobe, classification of correct/incorrect matches based on LFP phase was notably superior to classification based on amplitude and nearly equivalent to using the entire LFP signal. Notably, in these temporal regions, the mean phases for correct and incorrect trials aligned before diverging to encode trial outcomes. Specifically, neural responses in the amygdala suggested a mechanism of phase resetting, while activity in the parahippocampal gyrus indicated evoked potentials.

- 3)

- Rate Encoding: is a prevalent coding scheme employed in neural network models. In this scheme, each input pixel is interpreted as a firing rate and is transformed into a Poisson spike train with the corresponding firing rate. The input pixels undergo scaling by a factor , typically set to four for optimal classification and computational efficiency. This scaling ensures that the firing rates are limited between 0 and 63.75 Hz. The generation of Poisson spike trains involves comparing the scaled pixels with random numbers to determine the occurrence of spikes.

- 4)

-

Population Encoding: In any effective democracy, the influence of individual neurons is minimal; what truly matters is the collective activity of populations of neurons. For instance, in tasks like controlling eye and arm movements, or discerning visual stimuli in the primary visual cortex, the precision achieved far surpasses what could be expected from the responses of individual neurons. This is unsurprising, as single neurons provide limited information, necessitating some form of averaging across populations to obtain accurate sensory or motor information. However, the precise mechanisms underlying this averaging process in the brain, particularly how population codes are utilized in complex computations (like translating visual cues into motor actions), remain incompletely understood ([83]). This type of encoding is also referred to as frequency encoding.A significant challenge in comprehending population coding arises from the inherent noise in neurons: even when presented with the same stimulus, neuronal activity exhibits variability, making population coding inherently probabilistic. Consequently, a single noisy population response cannot precisely determine the stimulus; instead, the brain must compute an estimate of the stimulus or a probability distribution over potential stimuli. The accuracy of stimulus representation and the impact of noise on computations depend heavily on the nature of neuronal noise, particularly whether the noise is correlated among neurons. The encoding perspective examines how correlations impact the amount of information in a population code. This question lacks a straightforward answer, as correlations can increase, decrease, or leave the information unchanged, depending on their structure. While this may seem disappointing, it emphasizes the importance of understanding correlation details. General statements about correlations always helping or hurting are ruled out. To assess the impact of correlations on the information content within a population code, it’s essential to evaluate the information contained in the correlated responses, represented as I, and juxtapose it against the information that would be present if the responses were uncorrelated, denoted as . The term originates from the practice of decorrelating responses in experiments by shuffling trials. The difference between these two measures, denoted as , serves as a metric for gauging the influence of correlations on the information content within a population code. This method is significant because it allows for the quantification of information, enabling computation from empirical data.. This approach relies on quantifiable information computed from data. Understanding the impact of correlations on information can be illustrated using a two-neuron, two-stimulus example. Despite its small size, this example retains key features of larger population codes. By plotting correlated and uncorrelated response distributions and analyzing their features, we gain better understanding of the relationship between signal, noise, and information in pairs of neurons. The figure illustrates correlated and uncorrelated response distributions using ellipses to represent 95% confidence intervals ([83]).

- 5)

- Burst coding: Burst coding is a neural information transmission strategy that involves sending a burst of spikes simultaneously, enhancing synaptic communication reliability. Existing studies have shown that burst coding relies on two key parameters: the number of spikes and the inter-spike interval within the burst ([84,85]). Initially, input pixel intensities are normalized between zero and one. For each input pixel P, the burst’s spike count is determined by a function that incorporates a maximum spike count and the pixel intensity. Additionally, the is computed based on a function that considers the maximum and minimum interval values and , respectively, adjusted according to the spike count. Initially, the input pixels undergo normalization within the interval from zero to one. Concerning an input pixel denoted as where is the ceiling function, and is the maximum number of spikes. The Inter-Spike Interval is given as follows:where and are the maximum and minimum intervals, respectively. This scheme ensures that larger pixel intensities yield bursts with shorter and more spikes. The chosen parameter values, including , , and , align with biological norms to maintain biological plausibility ([86]).

4.3. Learning Rules in SNNs

4.3.1. Unsupervised Learning

4.3.2. Supervised Learning

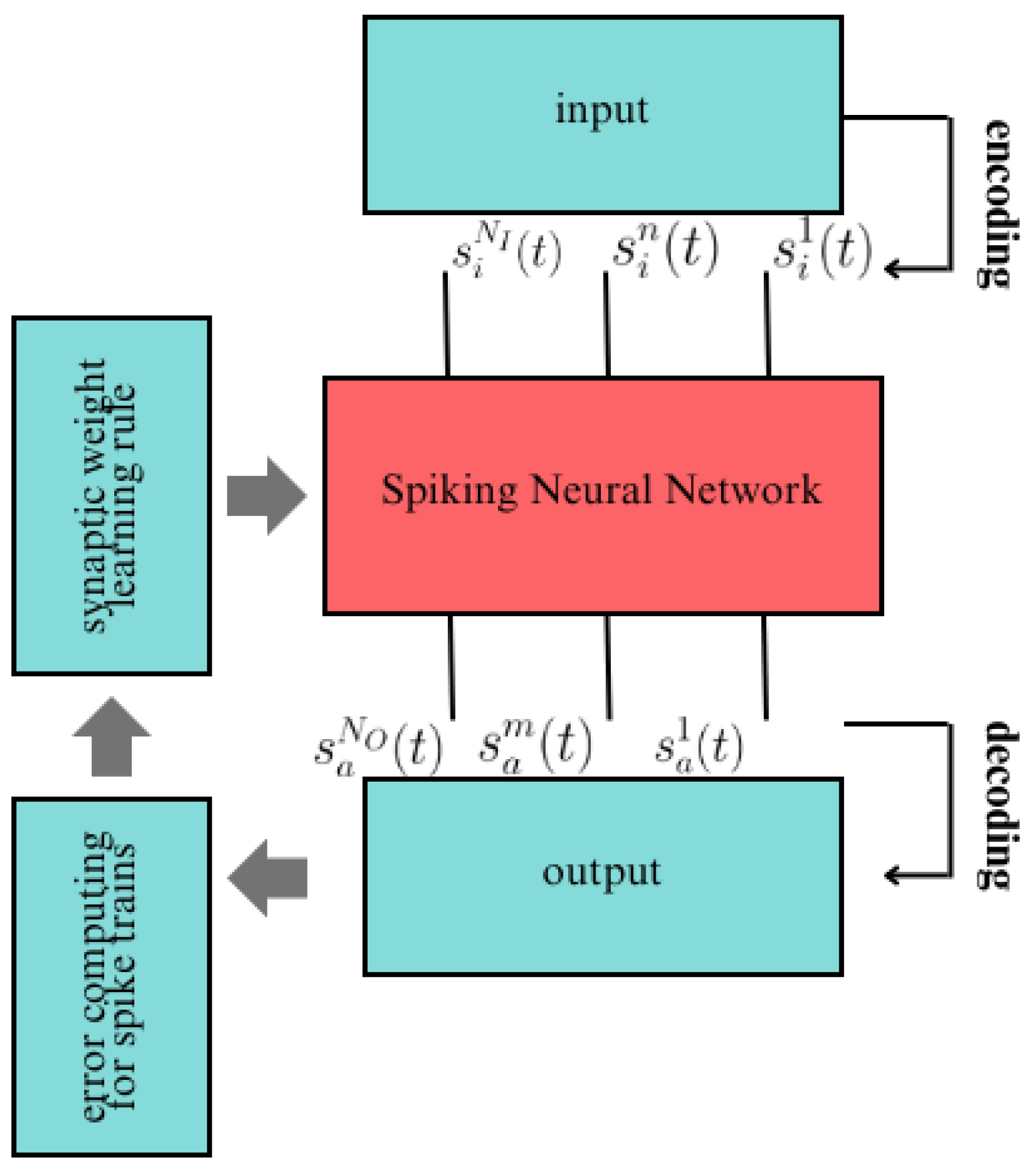

- Representing the input data as spike trains, denoted as , within the set of spike trains achieved through specific coding methods.

- The spike trains are fed into the SNN, followed by employing a particular simulation strategy to execute the network. Consequently, the resultant output spike trains within the set are obtained.

- In accordance with the target output spike trains within the set , the error function is computed, and subsequently, the synaptic weights are adjusted .

- Checking whether the error of the SNN, derived from the learning process, has reached a predefined minimum threshold or if the upper limit of learning epochs has been surpassed. If the termination condition is not met, the learning process is reiterated. Following supervised learning, the output spike trains from the network are decoded using a designated decoding methodology.

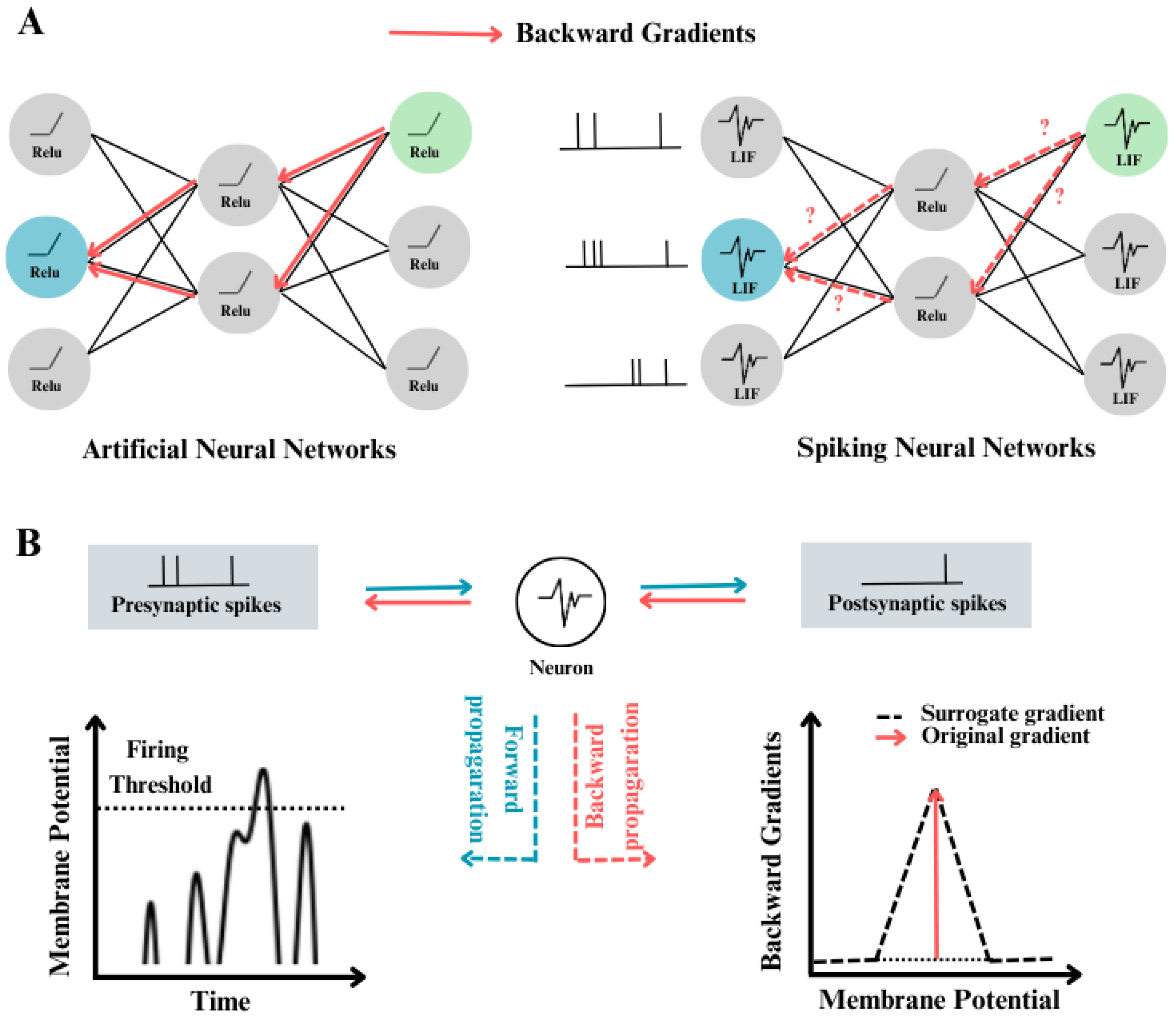

4.3.3. Training SNNs

- ANN-SNN Conversion: exemplified by works such as [101,102], use ideas from artificial neural networks to transform ReLU activation into spike activation mechanisms, to enable the generation of SNNs. [103], for instance, identify maximum activation in the training dataset to facilitate direct module replacement for SNN conversion. In contrast, [104] employ a soft-reset mechanism and eliminate leakage during conversion, proving effective in achieving accurate conversions. [107] have further refined conversion techniques by decomposing conversion errors, adjusting bias terms, and introducing calibration methods. Although conversion yields fast and accurate results, achieving near-lossless conversion demands substantial time steps (>200) to accumulate spikes, potentially leading to increased latency. [?] suggest a conversion-based training approach employing a "soft reset" spiking neuron, termed the Residual Membrane Potential (RMP) spiking neuron, which closely emulates the functionality of the Rectified Linear Unit (ReLU). Unlike conventional "hard reset" mechanisms that reset the membrane potential to a fixed value at spiking instants, the RMP neuron maintains a "residual" potential above the firing threshold. This approach mitigates the loss of information typically encountered during the conversion from Artificial Neural Networks to Spiking Neural Networks (SNNs). Methods for converting ANNs to SNNs have achieved performance in deep SNNs that is comparable to that of the original ANNs. These methods offer a potential solution to the energy-efficiency challenges faced by ANNs during deployment ([105]).

- Direct training of SNNs: as opposed to conversion methods, aims to reduce time steps and energy consumption by using gradient-descent algorithms. Notably, researchers have developed various strategies to address the non-differentiability of spike activation functions, akin to quantization or binarization neural networks ([106??], or adder neural networks ([107]. Achieving remarkable performance on datasets like CIFAR10, among others, has been demonstrated by works such as [108]. Some approaches resort to probabilistic models [109] or binary stochastic models ([110]) to approximate gradients, while others utilize rate-encoding networks ([111,112]) to quantify spike rate as information magnitude. For instance, [113] enhance the leaky integrate-and-fire (LIF) model to an iterative LIF model and introduce the STBP learning algorithm, while [114] propose the tdBN algorithm to balance gradient norms and smooth loss functions in SNN training, thus facilitating large-scale model optimization ([115]).

5. Methodology

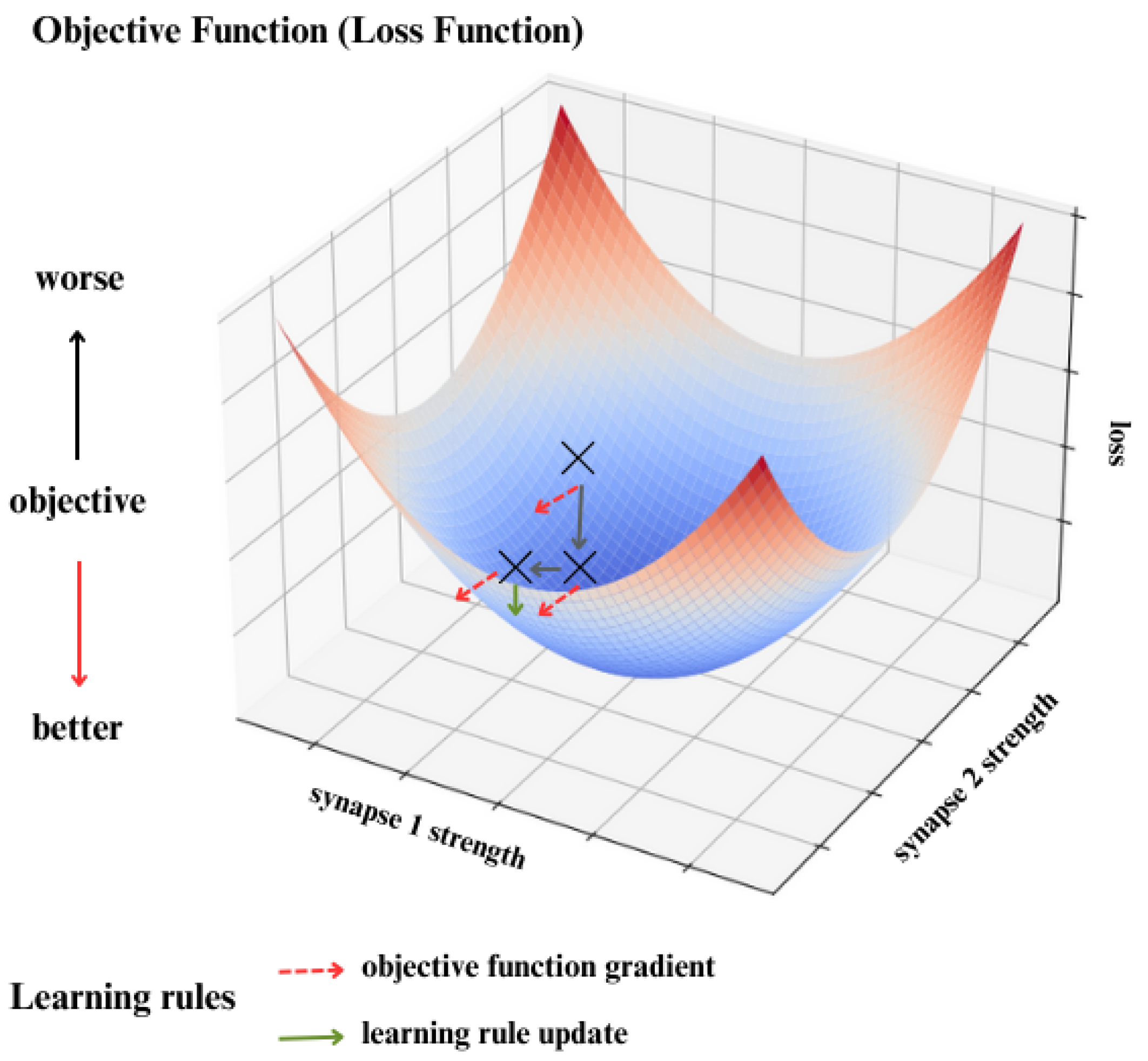

5.1. Objective Functions

5.2. Learning Rules

- is the membrane potential at time ,

- is the membrane potential at the previous time step ,

- is the membrane time constant,

- is the resting membrane potential,

- is the membrane resistance,

- is the input current at time , and

- is the time interval between consecutive input spikes and .

- is the time difference between the latest output spike time and the present input spike time ,

- is the maximum duration of the refractory period.

- is the synaptic weight of the i-th synapse for the present p-th input spike,

- is a dynamic weight controlling the refractory period.

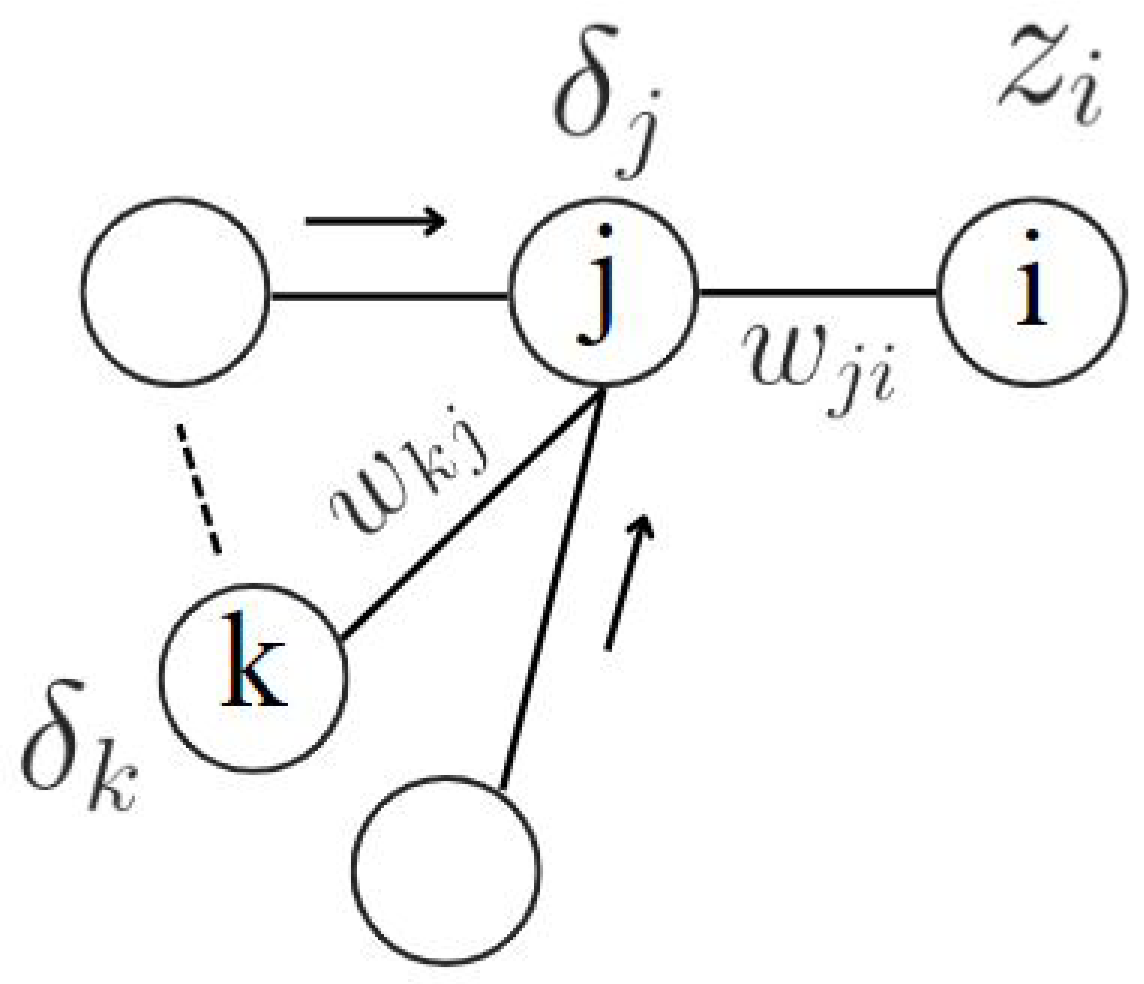

- Compute the Derivative of with respect to based on Equation 24:where is the error gradient for neuron j in layer , and is the activation of neuron i in layer l.

- Aggregate Gradients Across All Patterns:where is the error gradient for neuron j in layer for pattern n, and is the activation of neuron i in layer l for pattern n.

- Update the Parameters Using the Aggregated Gradients:where is the learning rate, and is the total derivative of the error function E with respect to .

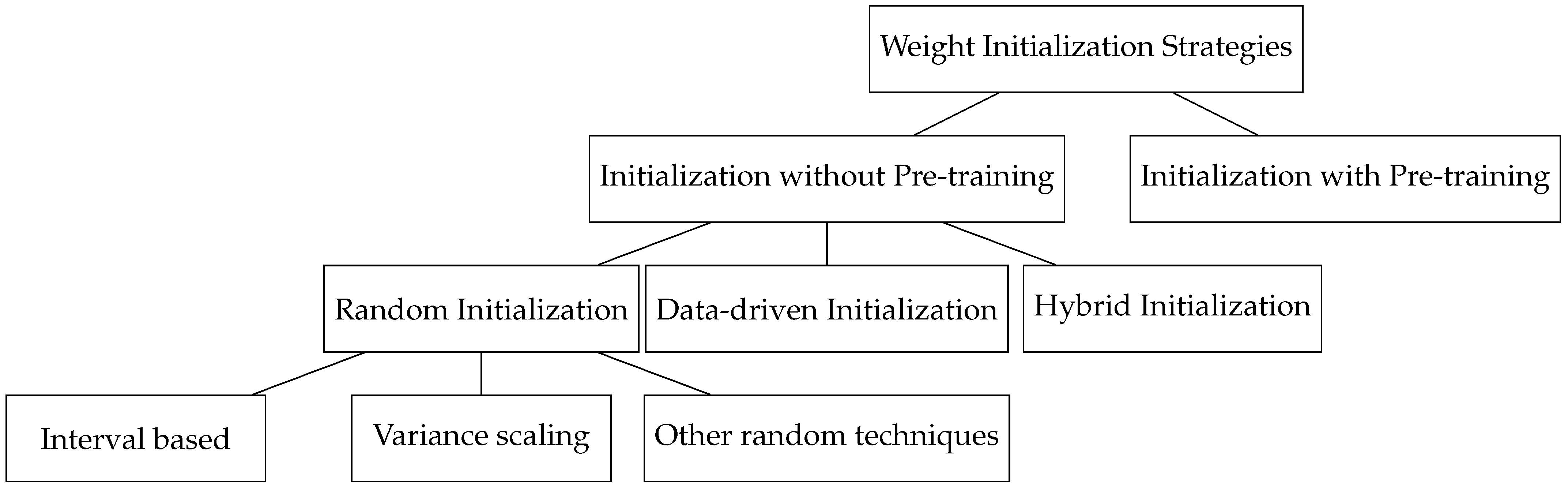

5.3. Weight Initialization

- Training from Scratch: This method entails setting up the network and using optimization methods to train it. For effective calculation, this method makes use of GPUs, FPGAs, or TPUs in conjunction with optimized libraries like CUDA, cuDNN, MKL, and OpenCL.

- Transfer Learning: Initializes and refines pre-trained models for use with certain tasks or datasets. This method works well for using previously learned characteristics and adjusting to fresh data.

-

Initialization without pre-training:

- Random initialization: This category investigates techniques that select weights from random distributions.

- Interval based initialization: This category explores techniques that choose initial weights within an optimal derived range.

- Variance scaling based initialization: This category examines various schemes where weights are scaled to maintain the variance of inputs and output activations.

- Other: This category includes random initialization techniques not covered in interval-based or variance scaling approaches.

- Data-driven initialization: This category focuses on initializing network weights derived from the training data.

- Hybrid: This category explores techniques that combine random and data-driven initialization approaches.

- Initialization with pre-training: This category explores methods where the initialization point is defined by an unsupervised approach for a supervised training algorithm ([147]).

- Random Initialization: Initialize the weights randomly from a specified distribution, for instance, uniform or normal distribution ([148]). For example:where a and b are the lower and upper bounds of the uniform distribution, and and are the mean and variance of the normal distribution.

- Xavier/Glorot Initialization: This method scales the initial weights based on the number of input and output neurons ([149]). For a uniform distribution:where is the number of input neurons and is the number of output neurons.

-

He Initialization: Similar to Xavier initialization, but optimized for ReLU activation functions ([150]):These initialization strategies set the starting values of weights in the network and provide a good starting point for training. The choice of initialization method can significantly impact the convergence and performance of the neural network during training, thus it is important to carefully choose an initializing tactic.

5.4. Weight Regularization

5.5. Weight Normalization

| Algorithm 1: Batch Normalization |

|

5.5.1. Threshold Regularization

6. Conclusion

References

- Wickens, A. A History of the Brain: From Stone Age surgery to modern neuroscience. Psychology Press. 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocca, J. brain, 2019. [CrossRef]

- Gross, C. , History of Neuroscience: Early Neuroscience; 2017. [CrossRef]

- Persaud, T.; Loukas, M.; Tubbs, R. A History of Human Anatomy; Charles C. Thomas, Publisher, Limited, 2014.

- Green, C.D. Where did the ventricular localization of mental faculties come from? Journal of the history of the behavioral sciences 2003, 39 2, 131–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammad, M., I. K.M.B.Q.M.A.M..A.A.

- Mazengenya, P.; Bhika, R. The Structure and Function of the Central Nervous System and Sense Organs in the Canon of Medicine by Avicenna. Archives of Iranian Medicine 2017, 20, 67–70. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Sur, M.; Rubenstein, J. Patterning and Plasticity of the Cerebral Cortex. Science 2005, 310, 805–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Celesia, G. Alcmaeon of Croton’s Observations on Health, Brain, Mind, and Soul. Journal of the History of the Neurosciences 2012, 21, 409–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benedum, J. [Importance of the brain in body-soul discussion from the history of medicine perspective]. Zentralblatt fur Neurochirurgie 1995, 56 4, 186–92. [Google Scholar]

- McCarley, R.; Hobson, J. The neurobiological origins of psychoanalytic dream theory. The American journal of psychiatry 1977, 134 11, 1211–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kucewicz, M.; Cimbalnik, J.; Cimbalnik, J.; Matsumoto, J.; Brinkmann, B.; Bower, M.R.; Vasoli, V.; Sulc, V.; Sulc, V.; Meyer, F.; et al. High frequency oscillations are associated with cognitive processing in human recognition memory. Brain : a journal of neurology 2014, 137 Pt 8, 2231–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herculano-Houzel, S. The remarkable, yet not extraordinary, human brain as a scaled-up primate brain and its associated cost. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 2012, 109 Suppl 1, 10661–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.C.; Delbruck, T. Neuromorphic sensory systems. Current Opinion in Neurobiology 2010, 20, 288–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, K.; Jaiswal, A.R.; Panda, P. Towards spike-based machine intelligence with neuromorphic computing. Nature 2019, 575, 607–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barney, N.; Lutkevich, B. What is neuromorphic computing?: Definition from TechTarget, 2023.

- van de Burgt, Y.; Melianas, A.; Keene, S.; Malliaras, G.; Salleo, A. Organic electronics for neuromorphic computing. Nature Electronics 2018, 1, 386–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kempter, R.; Gerstner, W.; van Hemmen, J.V. Hebbian learning and spiking neurons. Physical Review E 1999, 59, 4498–4514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, D.; Shen, J.; Gu, Z.; Zhang, M.; Zhu, X.; Xu, X.; Xu, Q.; Shen, Y.; Pan, G. Darwin: A neuromorphic hardware co-processor based on spiking neural networks. Journal of Systems Architecture 2017, 77, 43–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.; Cao, H.; Conradt, J.; Tang, H.; Rohrbein, F.; Knoll, A. Event-Based Neuromorphic Vision for Autonomous Driving: A Paradigm Shift for Bio-Inspired Visual Sensing and Perception. IEEE Signal Processing Magazine 2020, 37, 34–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marković, D.; Mizrahi, A.; Querlioz, D.; Grollier, J. Physics for neuromorphic computing. Nature Reviews Physics 2020, 2, 499–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brüderle, D.; Müller, E.; Davison, A.P.; Müller, E.B.; Schemmel, J.; Meier, K. Establishing a Novel Modeling Tool: A Python-Based Interface for a Neuromorphic Hardware System. Frontiers in Neuroinformatics 2008, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, C.H.; Lim, S.; Woo, S.; Kang, W.M.; Seo, Y.T.; Lee, S.; Lee, S.; Kwon, D.; Oh, S.; Noh, Y.; et al. Emerging memory technologies for neuromorphic computing. Nanotechnology 2018, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Debat, G.; Chauhan, T.; Cottereau, B.; Masquelier, T.; Paindavoine, M.; Baurès, R. Event-Based Trajectory Prediction Using Spiking Neural Networks. Frontiers in Computational Neuroscience 2021, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.; Panda, P. Optimizing Deeper Spiking Neural Networks for Dynamic Vision Sensing. Neural networks : the official journal of the International Neural Network Society 2021, 144, 686–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Du, B.; Shen, Y.; Wu, K.; Zhao, G.; Sun, J.; Wen, H. EV-Gait: Event-Based Robust Gait Recognition Using Dynamic Vision Sensors. 2019 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR) 2019, pp. 6351–6360. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, L.; Wang, X.; Chang, Y.; Li, J.; Huang, T.; Tian, Y. Event-based Video Reconstruction via Potential-assisted Spiking Neural Network. 2022 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR) 2022, pp. 3584–3594. [CrossRef]

- Wainberg, M.; Merico, D.; Delong, A.; Frey, B. Deep learning in biomedicine. Nature Biotechnology 2018, 36, 829–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muzio, G.; O’Bray, L.; Borgwardt, K. Biological network analysis with deep learning. Briefings in Bioinformatics 2020, 22, 1515–1530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koumakis, L. Deep learning models in genomics; are we there yet? Computational and Structural Biotechnology Journal 2020, 18, 1466–1473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumarasinghe, K.; Kasabov, N.; Taylor, D. Deep learning and deep knowledge representation in Spiking Neural Networks for Brain-Computer Interfaces. Neural networks : the official journal of the International Neural Network Society 2020, 121, 169–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kirkland, P.; Clemente, C.; Macdonald, M.; Caterina, G.D.; Meoni, G. Neuromorphic Sensing and Processing for Space Domain Awareness. IGARSS 2023 - 2023 IEEE International Geoscience and Remote Sensing Symposium 2023, pp. 4738–4741. [CrossRef]

- Maass, W. Networks of spiking neurons: The third generation of neural network models. Neural Networks 1997, 10, 1659–1671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franck, R.; Masuy-Stroobant, G.; Lories, G.; Vaerenbergh, A.M.; Scheepers, P.; Verberk, G.; Felling, A.; Callatay, A.; Verleysen, M.; Peeters, D.; et al. The Explanatory Power of Models, Bridging the Gap between Empirical and Theoretical Research in the Social Sciences; 2002. [CrossRef]

- McCulloch, W.S.; Pitts, W. A logical calculus of the ideas immanent in nervous activity. Bulletin of Mathematical Biophysics 1943, 5, 115–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavanaei, A.; Ghodrati, M.; Kheradpisheh, S.R.; Masquelier, T.; Maida, A. Deep Learning in Spiking Neural Networks. Neural networks : the official journal of the International Neural Network Society 2018, 111, 47–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh-Dastidar, S.; Adeli, H. Spiking Neural Networks. Int. J. Neural Syst. 2009, 19, 295–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maass, W. To Spike or Not to Spike: That Is the Question. Proc. IEEE 2015, 103, 2219–2224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maass, W. Lower bounds for the computational power of networks of spiking neurons. Neural Comput. 1996, 8, 1–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerstner, W.; Kistler, W.M.; Naud, R.; Paninski, L. Neuronal Dynamics: From Single Neurons to Networks and Models of Cognition; Cambridge University Press, 2014.

- Ramón y Cajal, S. Histologie du système nerveux de l’homme & des vertébrés; Vol. v. 1, Paris, Maloine, 1909-11; p. 1012. https://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/bibliography/48637.

- Völgyi, K.; Gulyássy, P.; Háden, K.; Kis, V.; Badics, K.; Kékesi, K.; Simor, A.; Győrffy, B.; Toth, E.; Lubec, G.; et al. Synaptic mitochondria: a brain mitochondria cluster with a specific proteome. Journal of proteomics 2015, 120, 142–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carrillo, S.; Harkin, J.; McDaid, L.; Pande, S.; Cawley, S.; McGinley, B.; Morgan, F. Advancing Interconnect Density for Spiking Neural Network Hardware Implementations using Traffic-Aware Adaptive Network-on-Chip Routers. Neural Networks 2012, 33, 42–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrante, M.A. Chapter 10 - Neuromuscular electrodiagnosis. In Motor System Disorders, Part I: Normal Physiology and Function and Neuromuscular Disorders; Younger, D.S., Ed.; Elsevier, 2023; Vol. 195, Handbook of Clinical Neurology, pp. 251–270. [CrossRef]

- Connors, B.; Long, M.A. Electrical synapses in the mammalian brain. Annual review of neuroscience 2004, 27, 393–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Häusser, M. Synaptic function: Dendritic democracy. Current Biology 2001, 11, R10–R12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peters, A.; Palay, S. The morphology of synapses. Journal of Neurocytology 1996, 25, 687–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haydon, P. Glia: listening and talking to the synapse. Nature Reviews Neuroscience 2001, 2, 185–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brette, R.; Gerstner, W. Adaptive exponential integrate-and-fire model as an effective description of neuronal activity. Journal of neurophysiology 2005, 94 5, 3637–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansel, D.; Mato, G.; Meunier, C.; Neltner, L. On Numerical Simulations of Integrate-and-Fire Neural Networks. Neural Computation 1998, 10, 467–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh-Dastidar, S.; Adeli, H. A new supervised learning algorithm for multiple spiking neural networks with application in epilepsy and seizure detection. Neural networks : the official journal of the International Neural Network Society 2009, 22 10, 1419–31.

- Brunel, N.; van Rossum, M. Quantitative investigations of electrical nerve excitation treated as polarization: Louis Lapicque 1907 · Translated by:. Biological Cybernetics 2007, 97, 341–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, A.V. Excitation and Accommodation in Nerve. Proceedings of The Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 1936, 119, 305–355. [Google Scholar]

- Burkitt, A. A Review of the Integrate-and-fire Neuron Model: I. Homogeneous Synaptic Input. Biological Cybernetics 2006, 95, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gerstein, G.L.; Mandelbrot, B.B. RANDOM WALK MODELS FOR THE SPIKE ACTIVITY OF A SINGLE NEURON. Biophysical journal 1964, 4, 41–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uhlenbeck, G.E.; Ornstein, L.S. On the Theory of the Brownian Motion. Phys. Rev. 1930, 36, 823–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knight, B.W. Dynamics of Encoding in a Population of Neurons. The Journal of General Physiology 1972, 59, 734–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kryukov, V.I. Wald’s Identity and Random Walk Models for Neuron Firing. Advances in Applied Probability 1976, 8, 257–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuckwell, H. On stochastic models of the activity of single neurons. Journal of Theoretical Biology - J THEOR BIOL 1977, 65, 783–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An analysis of Stein’s model for stochastic neuronal excitation. Biological cybernetics 1982, 45, 107–114. [CrossRef]

- Lánský, P. On approximations of Stein’s neuronal model. Journal of Theoretical Biology 1984, 107, 631–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al, H.; Af, H. A quantitative description of membrane current and its application to conduction and excitation in nerve. Bulletin of Mathematical Biology 1952, 52, 25–71. [Google Scholar]

- Li, M.; Tsien, J.Z. Neural code-Neural Self-information Theory on how cell-assembly code rises from spike time and neuronal variability. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 2017, 11, 236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerstner, W.; Kreiter, A.K.; Markram, H.; Herz, A.V. Neural codes: firing rates and beyond. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1997, 94, 12740–12741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Azarfar, A.; Calcini, N.; Huang, C.; Zeldenrust, F.; Celikel, T. Neural coding: A single neuron’s perspective. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2018, 94, 238–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adrian, E.D.; Zotterman, Y. The impulses produced by sensory nerve endings. J. Physiol. 1926, 61, 465–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johansson, R.S.; Birznieks, I. First spikes in ensembles of human tactile afferents code complex spatial fingertip events. Nat. Neurosci. 2004, 7, 170–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ponulak, F.; Kasinski, A. Introduction to spiking neural networks: Information processing, learning and applications. Acta Neurobiol. Exp. (Wars.) 2011, 71, 409–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Keefe, J.; Recce, M.L. Phase relationship between hippocampal place units and the EEG theta rhythm. Hippocampus 1993, 3, 317–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeldenrust, F.; Wadman, W.J.; Englitz, B. Neural coding with bursts—current state and future perspectives. Front. Comput. Neurosci. 2018, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buonomano, D.V.; Merzenich, M.M. Cortical plasticity: from synapses to maps. Annual review of neuroscience 1998, 21, 149–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karmarkar, U.; Dan, Y. Experience-Dependent Plasticity in Adult Visual Cortex. Neuron 2006, 52, 577–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caporale, N.; Dan, Y. Spike timing-dependent plasticity: a Hebbian learning rule. Annual review of neuroscience 2008, 31, 25–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hebb, D. O. The organization of behavior: A neuropsychological theory. New York: John Wiley and Sons, Inc., 1949. 335 p. $4.00. Sci. Educ. 1950, 34, 336–337. [Google Scholar]

- Bliss, T.V.P.; Gardner-Medwin, A.R. Long-lasting potentiation of synaptic transmission in the dentate area of the unanaesthetized rabbit following stimulation of the perforant path. The Journal of Physiology 1973, 232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Artola, A.; Singer, W. Long-term depression of excitatory synaptic transmission and its relationship to long-term potentiation. Trends in Neurosciences 1993, 16, 480–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Artola, A.; Singer, W. Artola, A. & Singer, W. Long-term potentiation and NMDA receptors in rat visual cortex. Nature 330, 649-652. Nature 1987, 330, 649–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dudek, S.M.; Bear, M.F. Bidirectional long-term modification of synaptic effectiveness in the adult and immature hippocampus. J. Neurosci. 1993, 13, 2910–2918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirkwood, A.; Bear, M.F. Hebbian synapses in visual cortex. J. Neurosci. 1994, 14, 1634–1645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bliss, T.V.; Collingridge, G.L. A synaptic model of memory: long-term potentiation in the hippocampus. Nature 1993, 361, 31–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montemurro, M.; Rasch, M.; Murayama, Y.; Logothetis, N.; Panzeri, S. Phase-of-Firing Coding of Natural Visual Stimuli in Primary Visual Cortex. Current Biology 2008, 18, 375–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopour, B.A.; Tavassoli, A.; Fried, I.; Ringach, D. Coding of Information in the Phase of Local Field Potentials within Human Medial Temporal Lobe. Neuron 2013, 79, 594–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Averbeck, B.; Latham, P.; Pouget, A. Neural correlations, population coding and computation. Nature Reviews Neuroscience 2006, 7, 358–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izhikevich, E.M.; Desai, N.S.; Walcott, E.C.; Hoppensteadt, F.C. Bursts as a unit of neural information: selective communication via resonance. Trends Neurosci. 2003, 26, 161–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eyherabide, H.G.; Rokem, A.; Herz, A.V.M.; Samengo, I. Bursts generate a non-reducible spike-pattern code. Front. Neurosci. 2009, 3, 8–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, W.; Fouda, M.E.; Eltawil, A.M.; Salama, K.N. Neural Coding in Spiking Neural Networks: A Comparative Study for Robust Neuromorphic Systems. Frontiers in Neuroscience 2021, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- .

- Markram, H.; Gerstner, W.; Sjöström, P.J. A History of Spike-Timing-Dependent Plasticity. Frontiers in Synaptic Neuroscience 2011, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markram, H.; Lübke, J.; Frotscher, M.; Sakmann, B. Regulation of Synaptic Efficacy by Coincidence of Postsynaptic APs and EPSPs. Science (New York, N.Y.) 1997, 275, 213–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- qiang Bi, G.; ming Poo, M. Synaptic Modifications in Cultured Hippocampal Neurons: Dependence on Spike Timing, Synaptic Strength, and Postsynaptic Cell Type. Journal of Neuroscience 1998, 18, 10464–10472, [https://www.jneurosci.org/content/18/24/10464.full.pdf]. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, S.; Sjöström, P.; Turrigiano, G. Rate and timing in cortical synaptic plasticity. Philosophical transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B, Biological sciences 2003, 357, 1851–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, R.; Olshausen, B.; Lewicki, M. Probabilistic Models of the Brain: Perception and Neural Function 2002.

- Doya, K.; Ishii, S.; Pouget, A.; Rao, R.P.N. Bayesian Brain: Probabilistic Approaches to Neural Coding; The MIT Press, 2007.

- Kording, K.; Wolpert, D. Bayesian integration in sensorimotor learning. Nature 2004, 427, 244–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nessler, B.; Pfeiffer, M.; Maass, W. STDP enables spiking neurons to detect hidden causes of their inputs. In Proceedings of the Proc. of Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems (NIPS). MIT Press, 2010, pp. 1357–1365. 23rd Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems ; Conference date: 08-12-2009 Through 12-12-2009.

- Nessler, B.; Pfeiffer, M.; Buesing, L.; Maass, W. Bayesian Computation Emerges in Generic Cortical Microcircuits through Spike-Timing-Dependent Plasticity. PLOS Computational Biology 2013, 9, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klampfl, S.; Maass, W. Emergence of Dynamic Memory Traces in Cortical Microcircuit Models through STDP. Journal of Neuroscience 2013, 33, 11515–11529, [https://www.jneurosci.org/content/33/28/11515.full.pdf]. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bishop, C. Neural Networks For Pattern Recognition; Vol. 227, 2005. [CrossRef]

- Youngeun, K.; Priyadarshini, P. Visual explanations from spiking neural networks using inter-spike intervals. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 19037. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.; Lin, X.; Dang, X. Supervised learning in spiking neural networks: A review of algorithms and evaluations. Neural Networks 2020, 125, 258–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, B.; Srinivasan, G.; Roy, K. RMP-SNN: Residual Membrane Potential Neuron for Enabling Deeper High-Accuracy and Low-Latency Spiking Neural Network. 06 2020, pp. 13555–13564. [CrossRef]

- Sengupta, A.; Ye, Y.; Wang, R.; Liu, C.; Roy, K. Going Deeper in Spiking Neural Networks: VGG and Residual Architectures. Frontiers in Neuroscience 2018, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rueckauer, B.; Lungu, I.A.; Hu, Y.; Pfeiffer, M. Theory and tools for the conversion of analog to spiking convolutional neural networks 2016.

- Han, B.; Roy, K. , Deep Spiking Neural Network: Energy Efficiency Through Time Based Coding; 2020; pp. 388–404. [CrossRef]

- Yamazaki, K.; Vo-Ho, V.K.; Bulsara, D.; Le, N. Spiking neural networks and their applications: A review. Brain Sci. 2022, 12, 863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Dong, X.; Wang, W. Additive Powers-of-Two quantization: An efficient non-uniform discretization for neural networks 2019. arXiv:cs.LG/1909.13144.

- Chen, H.; Wang, Y.; Xu, C.; Shi, B.; Xu, C.; Tian, Q.; Xu, C. AdderNet: Do we really need multiplications in deep learning? 2019. arXiv:cs.CV/1912.13200.

- Amir, A.; Taba, B.; Berg, D.; Melano, T.; McKinstry, J.; Di Nolfo, C.; Nayak, T.; Andreopoulos, A.; Garreau, G.; Mendoza, M.; et al. A Low Power, Fully Event-Based Gesture Recognition System. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2017; pp. 7388–7397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brea, J.; Senn, W.; Pfister, J.P. Matching Recall and Storage in Sequence Learning with Spiking Neural Networks. Journal of Neuroscience 2013, 33, 9565–9575, [https://www.jneurosci.org/content/33/23/9565.full.pdf]. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bengio, Y.; Léonard, N.; Courville, A. Estimating or propagating gradients through stochastic neurons for conditional computation 2013. [arXiv:cs.LG/1308.3432]. arXiv:cs.LG/1308.3432.

- Lee, J.H.; Delbruck, T.; Pfeiffer, M. Training deep spiking neural networks using backpropagation 2016. [arXiv:cs.NE/1608.08782]. arXiv:cs.NE/1608.08782.

- Neftci, E.; Augustine, C.; Paul, S.; Detorakis, G. Event-Driven Random Back-Propagation: Enabling Neuromorphic Deep Learning Machines. Frontiers in Neuroscience 2017, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Deng, L.; Li, G.; Zhu, J.; Shi, L. Spatio-Temporal Backpropagation for Training High-Performance Spiking Neural Networks. Frontiers in Neuroscience 2017, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, H.; Wu, Y.; Deng, L.; Hu, Y.; Li, G. Going deeper with directly-trained larger spiking neural networks 2020. [arXiv:cs.NE/2011.05280]. arXiv:cs.NE/2011.05280.

- Li, Y.; Guo, Y.; Zhang, S.; Deng, S.; Hai, Y.; Gu, S. Differentiable Spike: Rethinking Gradient-Descent for Training Spiking Neural Networks. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems; Ranzato, M.; Beygelzimer, A.; Dauphin, Y.; Liang, P.; Vaughan, J.W., Eds. Curran Associates, Inc., 2021, Vol. 34, pp. 23426–23439.

- Goodfellow, I.; Bengio, Y.; Courville, A. Deep Learning; MIT Press, 2016. http://www.deeplearningbook.org.

- Kell, A.; Yamins, D.; Shook, E.; Norman-Haignere, S.; McDermott, J. A Task-Optimized Neural Network Replicates Human Auditory Behavior, Predicts Brain Responses, and Reveals a Cortical Processing Hierarchy. Neuron 2018, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bashivan, P.; Kar, K.; Dicarlo, J. Neural population control via deep image synthesis. Science 2019, 364, eaav9436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- .

- Bohte, S.M.; Kok, J.N.; La Poutré, H. Error-backpropagation in temporally encoded networks of spiking neurons. Neurocomputing 2002, 48, 17–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Natschläger, T.; Ruf, B. Pattern analysis with spiking neurons using delay coding. Neurocomputing 1999, 26-27, 463–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xin, J.; Embrechts, M. Supervised learning with spiking neural networks. 02 2001, Vol. 3, pp. 1772 – 1777 vol.3. [CrossRef]

- McKennoch, S.; Liu, D.; Bushnell, L. Fast Modifications of the SpikeProp Algorithm. 01 2006, Vol. 16, pp. 3970 – 3977. [CrossRef]

- Silva, S.; Ruano, A. Application of Levenberg-Marquardt method to the training of spiking neural networks. 11 2005, Vol. 3, pp. 1354– 1358. [CrossRef]

- Schrauwen, B.; Campenhout, J. Extending SpikeProp. 08 2004, Vol. 1, p. 475. [CrossRef]

- Booij, O.; Nguyen, H. A gradient descent rule for spiking neurons emitting multiple spikes. Information Processing Letters 2005, 95, 552–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiete, I.R.; Seung, H.S. Gradient learning in spiking neural networks by dynamic perturbation of conductances. Physical review letters 2006, 97 4, 048104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dembo, A.; Kailath, T. Model-free distributed learning. IEEE Transactions on Neural Networks 1990, 1, 58–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vieira, J.; Arévalo, O.; Pawelzik, K. Stochastic gradient ascent learning with spike timing dependent plasticity. BMC Neuroscience 2011, 12, P250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choudhary, K.; DeCost, B.; Chen, C.; Jain, A.; Tavazza, F.; Cohn, R.; Park, C.W.; Choudhary, A.; Agrawal, A.; Billinge, S.J.L.; et al. Recent advances and applications of deep learning methods in materials science. Npj Comput. Mater. 2022, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baydin, A.G.; Pearlmutter, B.A.; Radul, A.A.; Siskind, J.M. Automatic differentiation in machine learning: a survey. Journal of machine learning research 2018, 18, 1–43. [Google Scholar]

- Jadon, A.; Patil, A.; Jadon, S. A comprehensive survey of regression based loss functions for time Series Forecasting 2022. [arXiv:cs.LG/2211.02989]. arXiv:cs.LG/2211.02989.

- Zhang, Z.; Sabuncu, M.R. Generalized cross entropy loss for training deep neural networks with noisy labels 2018. [arXiv:cs.LG/1805.07836]. arXiv:cs.LG/1805.07836.

- Rosset, S.; Zhu, J.; Hastie, T. Margin maximizing loss functions. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 16th International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems, Cambridge, MA, USA, 2003; NIPS’03, p. 1237–1244.

- Duda, R.O.; Hart, P.E. Pattern classification and scene analysis. In Proceedings of the A Wiley-Interscience publication; 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Kline, D.M.; Berardi, V.L. Revisiting squared-error and cross-entropy functions for training neural network classifiers. Neural Computing & Applications 2005, 14, 310–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiete, I.; Seung, H. Gradient learning in spiking neural networks by dynamic perturbation of conductances. Physical review letters 2006, 97 4, 048104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Yılmaz, E.; Zhang, M.; Li, H.; Tan, K.C. Deep Spiking Neural Networks for Large Vocabulary Automatic Speech Recognition. Frontiers in Neuroscience 2020, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bastos, A.M.; Usrey, W.; Adams, R.A.; Mangun, G.R.; Fries, P.; Friston, K.J. Canonical Microcircuits for Predictive Coding. Neuron 2012, 76, 695–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, X.; Qu, H.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, Y. First Error-Based Supervised Learning Algorithm for Spiking Neural Networks. Frontiers in Neuroscience 2019, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Widrow, B.; Lehr, M. 30 years of adaptive neural networks: perceptron, Madaline, and backpropagation. Proceedings of the IEEE 1990, 78, 1415–1442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masquelier, T.; Guyonneau, R.; Thorpe, S. Competitive STDP-Based Spike Pattern Learning. Neural computation 2009, 21, 1259–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, J.; Delbrück, T.; Pfeiffer, M. Training Deep Spiking Neural Networks Using Backpropagation. Frontiers in Neuroscience 2016, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rozell, C.J.; Johnson, D.H.; Baraniuk, R.G.; Olshausen, B.A. Sparse coding via thresholding and local competition in neural circuits. Neural Comput. 2008, 20, 2526–2563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fair, K.L.; Mendat, D.R.; Andreou, A.G.; Rozell, C.J.; Romberg, J.; Anderson, D.V. Sparse Coding Using the Locally Competitive Algorithm on the TrueNorth Neurosynaptic System. Frontiers in Neuroscience 2019, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yam, J.Y.F.; Chow, T.; Leung, C. A new method in determining initial weights of feedforward neural networks for training enhancement. Neurocomputing 1997, 16, 23–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narkhede, M.V.; Bartakke, P.; Sutaone, M. A review on weight initialization strategies for neural networks. Artificial Intelligence Review 2021, 55, 291–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sussillo, D.; Abbott, L.F. Random Walk Initialization for Training Very Deep Feedforward Networks. arXiv: Neural and Evolutionary Computing 2014.

- Glorot, X.; Bengio, Y. Understanding the difficulty of training deep feedforward neural networks. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the Thirteenth International Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Statistics; Teh, Y.W.; Titterington, M., Eds., Chia Laguna Resort, Sardinia, Italy, 13–15 May 2010; Vol. 9, Proceedings of Machine Learning Research, pp. 249–256.

- He, K.; Zhang, X.; Ren, S.; Sun, J. Delving deep into rectifiers: Surpassing human-level performance on ImageNet classification 2015. arXiv:cs.CV/1502.01852.

- Srivastava, N.; Hinton, G.; Krizhevsky, A.; Sutskever, I.; Salakhutdinov, R. Dropout: A Simple Way to Prevent Neural Networks from Overfitting. Journal of Machine Learning Research 2014, 15, 1929–1958. [Google Scholar]

- Ioffe, S.; Szegedy, C. Batch Normalization: Accelerating Deep Network Training by Reducing Internal Covariate Shift 2015.

- Garbin, C.; Zhu, X.; Marques, O. Dropout vs. batch normalization: an empirical study of their impact to deep learning. Multimedia Tools and Applications 2020, 79, 12777–12815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afshar, S.; George, L.; Tapson, J.; van Schaik, A.; Chazal, P.; Hamilton, T. Turn Down that Noise: Synaptic Encoding of Afferent SNR in a Single Spiking Neuron. IEEE transactions on biomedical circuits and systems 2014, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rumelhart, D.E.; Zipser, D. Feature discovery by Competitive Learning. Cogn. Sci. 1985, 9, 75–112. [Google Scholar]

- Diehl, P.U.; Neil, D.; Binas, J.; Cook, M.; Liu, S.C.; Pfeiffer, M. Fast-classifying, high-accuracy spiking deep networks through weight and threshold balancing. In Proceedings of the 2015 International Joint Conference on Neural Networks (IJCNN); 2015; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Objective Function | Description, Use Cases, Advantages, Disadvantages, References | Equations |

|---|---|---|

| Mean Squared Error (MSE) | Measures the average of the squares of the differences between predicted and actual values. Commonly used in regression tasks for its simplicity and convexity, making it easy to optimize. However, it can be sensitive to outliers and may not be suitable for classification tasks [132]. | , where is the actual output and is the predicted output. |

| Cross Entropy Loss | Measures the difference between two probability distributions for classification tasks. Useful for multi-class classification and robust against class imbalance. However, it can suffer from vanishing gradients in deep networks [133]. | , where is the true label and is the predicted probability. |

| Margin Loss | Incorporates a margin parameter to penalize predictions within a specified margin. Used in tasks like binary classification with imbalanced classes. Tuning the margin parameter may require domain knowledge [134]. | , where m is the margin, is the true class, and is the predicted score. |

| Approach | Description | Key Resources |

|---|---|---|

| Training from Scratch | The network is initialized appropriately and trained using a suitable optimization algorithm. Deep learning frameworks offer predefined functions for weight initialization and allow custom initialization methods. Specialized hardware (GPUs, FPGAs, TPUs) and optimized libraries (CUDA, cuDNN, MKL, OpenCL) are used for efficient training from scratch. | GPUs, FPGAs, TPUs, CUDA, cuDNN, MKL, OpenCL |

| Transfer Learning | A deep neural network is initialized with weights from a pre-trained model and fine-tuned for a new dataset. This approach is useful for taking advantage of pre-learned features and adapting to smaller datasets. | Pre-trained models, fine-tuning techniques |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).