Submitted:

13 June 2025

Posted:

17 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Source: Ungdata Survey

2.2. Sample

2.3. Measures

2.4. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

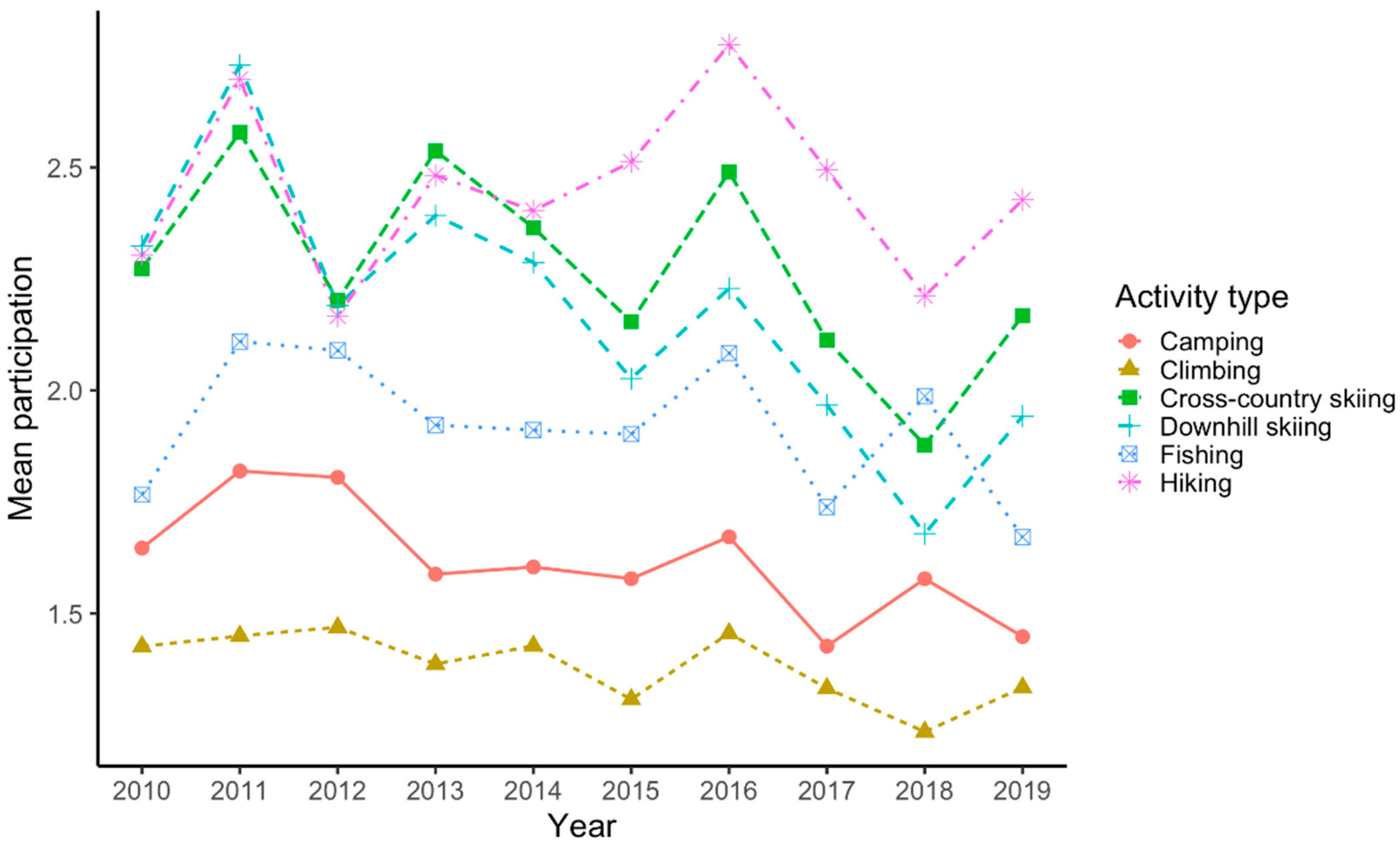

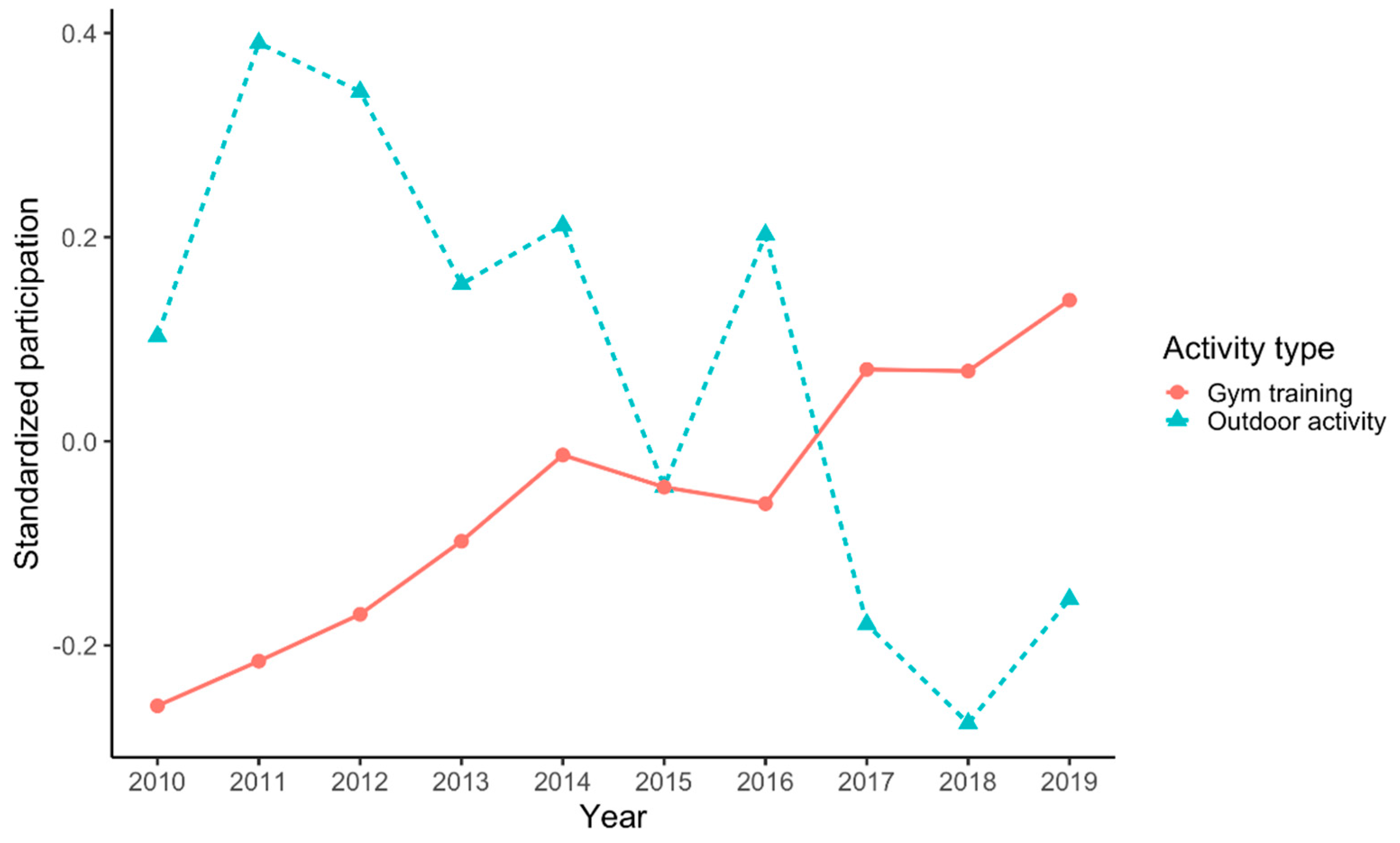

3.1. Descriptive Trends

3.2. Multilevel regression

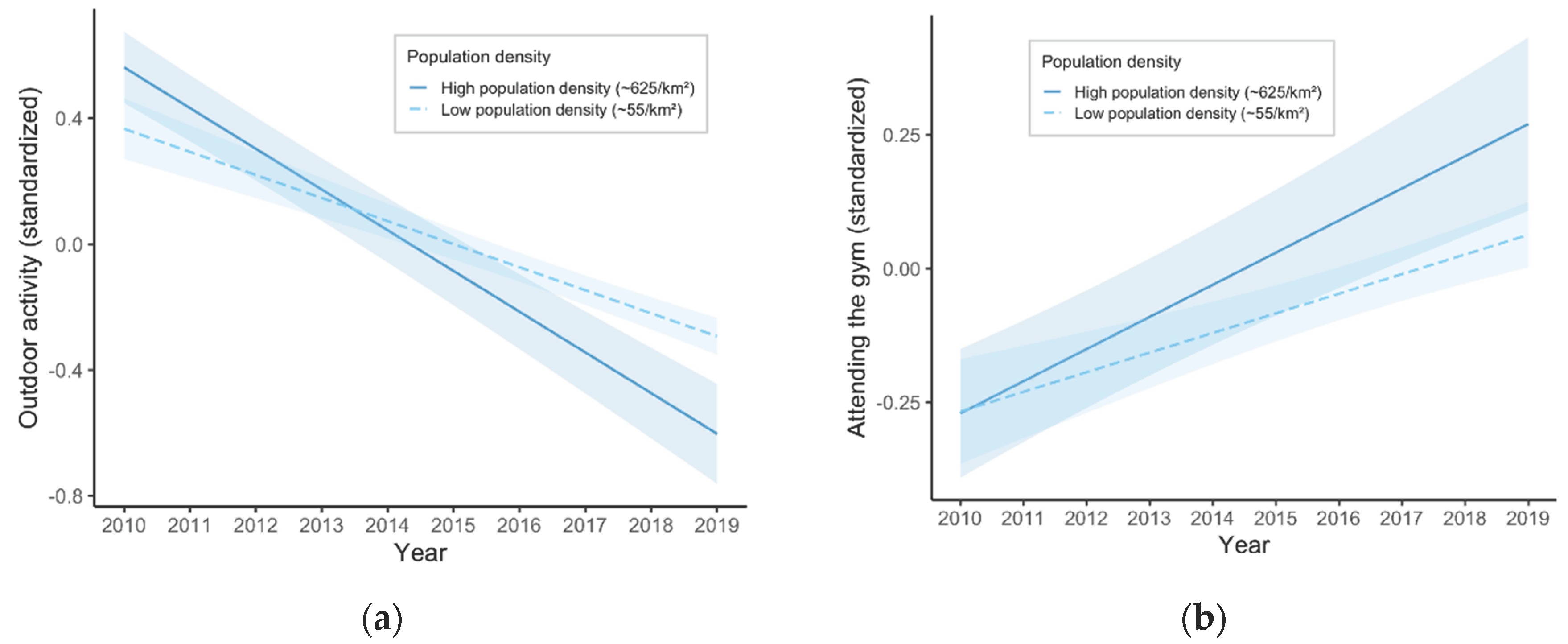

3.2.1. Outdoor Recreation

3.2.2. Gym Training

4. Discussion

4.1. Main Findings

4.2. Population Density as Moderator

4.3. Associations with Individual Characteristics

4.4. Strengths and Limitations

4.5. Implications and Future Directions

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- United Nations, World urbanization prospects: The 2018 revision (st/esa/ser. a/420). United Nations, New York, 2019.

- Statistics Norway. Land use and land cover. 2022 12.09.2022]; Available from: https://www.ssb.no/en/natur-og-miljo/areal/statistikk/arealbruk-og-arealressurser.

- Frank, L.D., P. Engelke, and T.L. Schmid, Health and community design: the impact of the built environment on physical activity. Choice Reviews Online 2004, 41, 41–2837.

- Shah, J. , et al. , New age technology and social media: adolescent psychosocial implications and the need for protective measures. Current Opinion in Pediatrics 2018, 31, 148–156. [Google Scholar]

- Friluftsliv i Norge. Regjeringen.no, 2021.

- Wilson, E.O., Biophilia. 1986: Harvard university press.

- Ulrich, R.S., et al., Stress recovery during exposure to natural and urban environments. Journal of Environmental Psychology 1991, 11, 201–230. [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, R. and S. Kaplan, The experience of nature: A psychological perspective. 1989: Cambridge university press.

- Wells, N.M. and G.W. Evans, Nearby Nature. Environment and Behavior. 2003, 35, 311–330.

- Roberts, H., et al., The effect of short-term exposure to the natural environment on depressive mood: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Environmental Research. 2019, 177, 108606.

- Nguyen, L. and J. Walters, Benefits of nature exposure on cognitive functioning in children and adolescents: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Environmental Psychology 2024, 96, 102336. [CrossRef]

- Ulset, V., et al., Time spent outdoors during preschool: Links with children's cognitive and behavioral development. Journal of Environmental Psychology 2017, 52, 69–80.

- Ulset, V.S., et al., Link of outdoor exposure in daycare with attentional control and academic achievement in adolescence: Examining cognitive and social pathways. Journal of Environmental Psychology 2023, 85, 101942. [CrossRef]

- Säfvenbom, R., W. Belinda, and J.P. and Agans, ‘How can you enjoy sports if you are under control by others?’ Self-organized lifestyle sports and youth development. Sport in Society 2018, 21, 1990–2009. [CrossRef]

- Eriksen, I.M., et al., Stress og press blant ungdom. Erfaringer, årsaker og utbredelse av psykiske helseplager. 2017: Oslo Metropolitan University-OsloMet: NOVA.

- von Soest, T., et al., Adolescents’ psychosocial well-being one year after the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic in Norway. Nature Human Behaviour 2022, 6, 217–228. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laverty, J. and J. Wright, Going to the gym: The new urban ‘It’space, in Young people, physical activity and the everyday. 2010, Routledge. pp. 54–68.

- Redzovic, S., I. Johansen, and T. Bonsaksen, Profiling adolescent participation in wildlife activities and its implications on mental health: evidence from the Young-HUNT study in Norway. Frontiers in Public Health 2025, 13.

- Vaage, O.F. Adolescent Time Use Trends in Norway. Loisir et Société / Society and Leisure 2005, 28, 443–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pergams, O.R.W. and P.A. Zaradic, Evidence for a fundamental and pervasive shift away from nature-based recreation. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2008, 105, 2295–2300. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frøyland, L.R., Ungdata–Lokale ungdomsundersøkelser. Dokumentasjon av variablene i spørreskjemaet. Nova, 2017.

- Schmalbach, B., et al., Psychometric Properties of Two Brief Versions of the Hopkins Symptom Checklist: HSCL-5 and HSCL-10. Assessment 2019, 28, 617–631.

- Didkan, K. MODIS/Terra Vegetation Indices 16-Day L3 Global 250m SIN Grid V061 [Data set]. NASA EOSDIS Land Processes DAAC. 2021 2022-09-13].

- Dadvand, P., et al., Surrounding greenness and pregnancy outcomes in four Spanish birth cohorts. Environ Health Perspect 2012, 120, 1481–1487. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gascon, M., et al., Normalized difference vegetation index (NDVI) as a marker of surrounding greenness in epidemiological studies: The case of Barcelona city. Urban Forestry & Urban Greening 2016, 19, 88–94.

- Dervo, B.K., et al., Friluftsliv i Norge anno 2014–status og utfordringer. 2014.

- Bakken, A. and Å. Strandby, Idrettsdeltakelse blant ungdom – før, under og etter koronapandemien [Sports participation among adolescents - before, during and after the COVID-19 pandemic]. 2023, Velferdsforskningsinstituttet NOVA.

- Lyons, R., et al.,The relationship between urban greenspace perception and use within the adolescent population: A focused ethnography. Journal of Advanced Nursing 2023, 80, 2869–2879.

- Kleppang, A.L., et al., The association between physical activity and symptoms of depression in different contexts – a cross-sectional study of Norwegian adolescents. BMC Public Health 2018, 18, 1368.

| Outdoor Recreation | Gym Training | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Predictors | Estimates | CI | p | Estimates | CI | p |

| Intercept (baseline level) | 0.59 | 0.50 – 0.69 | <0.001 | -0.32 | -0.42 – -0.23 | <0.001 |

| Depressive symptoms | -0.07 | -0.08 – -0.06 | <0.001 | 0.02 | 0.01 – 0.03 | <0.001 |

| Gender (1 = boy, 2 = girl) | -0.04 | -0.05 – -0.03 | <0.001 | -0.05 | -0.05 – -0.04 | <0.001 |

| Grade level (proxy for age) | -0.13 | -0.14 – -0.11 | <0.001 | 0.31 | 0.30 – 0.32 | <0.001 |

| Vegetation density (NDVI) | 0.07 | 0.03 – 0.11 | 0.001 | -0.00 | -0.05 – 0.04 | 0.904 |

| Gym training | 0.10 | 0.09 – 0.11 | <0.001 | |||

| Population density | 0.25 | 0.10 – 0.40 | 0.001 | -0.03 | -0.18 – 0.13 | 0.737 |

| Year (centered at 2010) | -0.11 | -0.12 – -0.10 | <0.001 | 0.05 | 0.04 – 0.06 | <0.001 |

| Interaction: Year × Population density | -0.06 | -0.08 – -0.03 | <0.001 | 0.02 | -0.00 – 0.05 | 0.063 |

| Outdoor recreation | 0.09 | 0.08 – 0.09 | <0.001 | |||

| Random Effects | ||||||

| σ2 | 0.96 | 0.84 | ||||

| τ00 | 0.02 municipality | 0.03 municipality | ||||

| ICC | 0.02 | 0.03 | ||||

| N | 75 municipality | 75 municipality | ||||

| Observations | 45627 | 45627 | ||||

| Marginal R2 / Conditional R2 | 0.100 / 0.120 | 0.106 / 0.134 | ||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).