Submitted:

14 May 2025

Posted:

16 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- -

- Which outdoor activities are Norwegian children engaged in, how often, and what are the main changes?

- -

- What are the main constraints for children’s nature engagement, and what are the main changes?

- -

- What kind of demographic and social variables may explain the observed pattern of constraints?

2. Constraints to Children’s Use of Nearby Nature

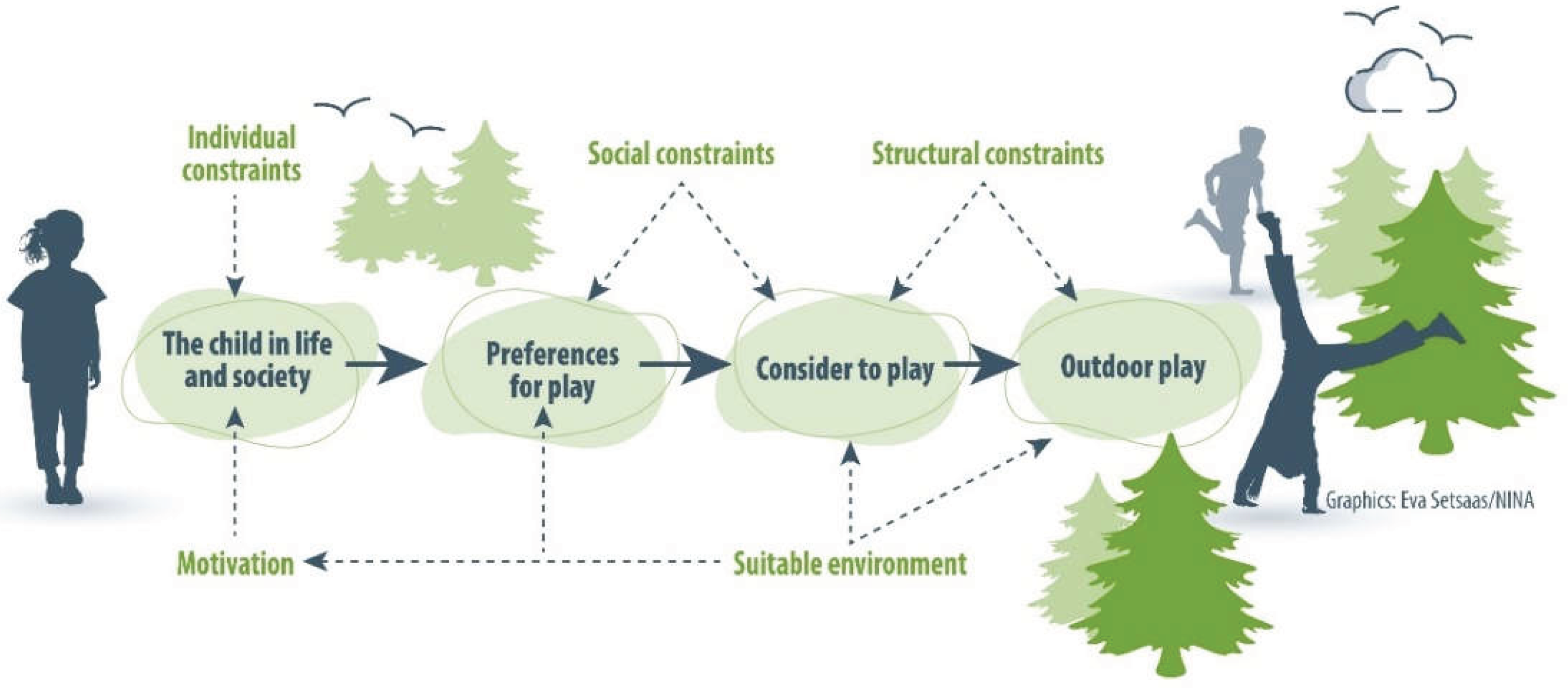

2.1. An ecological Model for Studying Constraints for Outdoor Play

- Individual, called intra-personal (and especially psychologically speaking), such as self-image, interests-preferences, age, stage of life, own physical health, knowledge, disability, anxiety, fear, attitudes, and own norms.

- Social, called inter-personal, such as social circle, lack of play companion, family responsibilities, and a social network for outdoor play.

- Structural, both related to the private and to the external environment, such as the socio-cultural, economy, transportation, time constraints, physical access to playing areas, distance to and quality of outdoor space. Institutional constraints (e.g., fee, restrictions) are included in this category, but are consider less important in Norway due to common rights of access.

2.2. Motivation and Individual/Intrapersonal Constraints

2.3. Social/Interpersonal Constraints

2.4. Structural Constraints and Environmental Quality

3. Material and Methods

3.1. Target Population, Sampling Technique, and Sample

3.2. Questionnaire and Measurement Methods

3.3. Data Processing and Analyses

3.4. Ethics Approval

4. Results

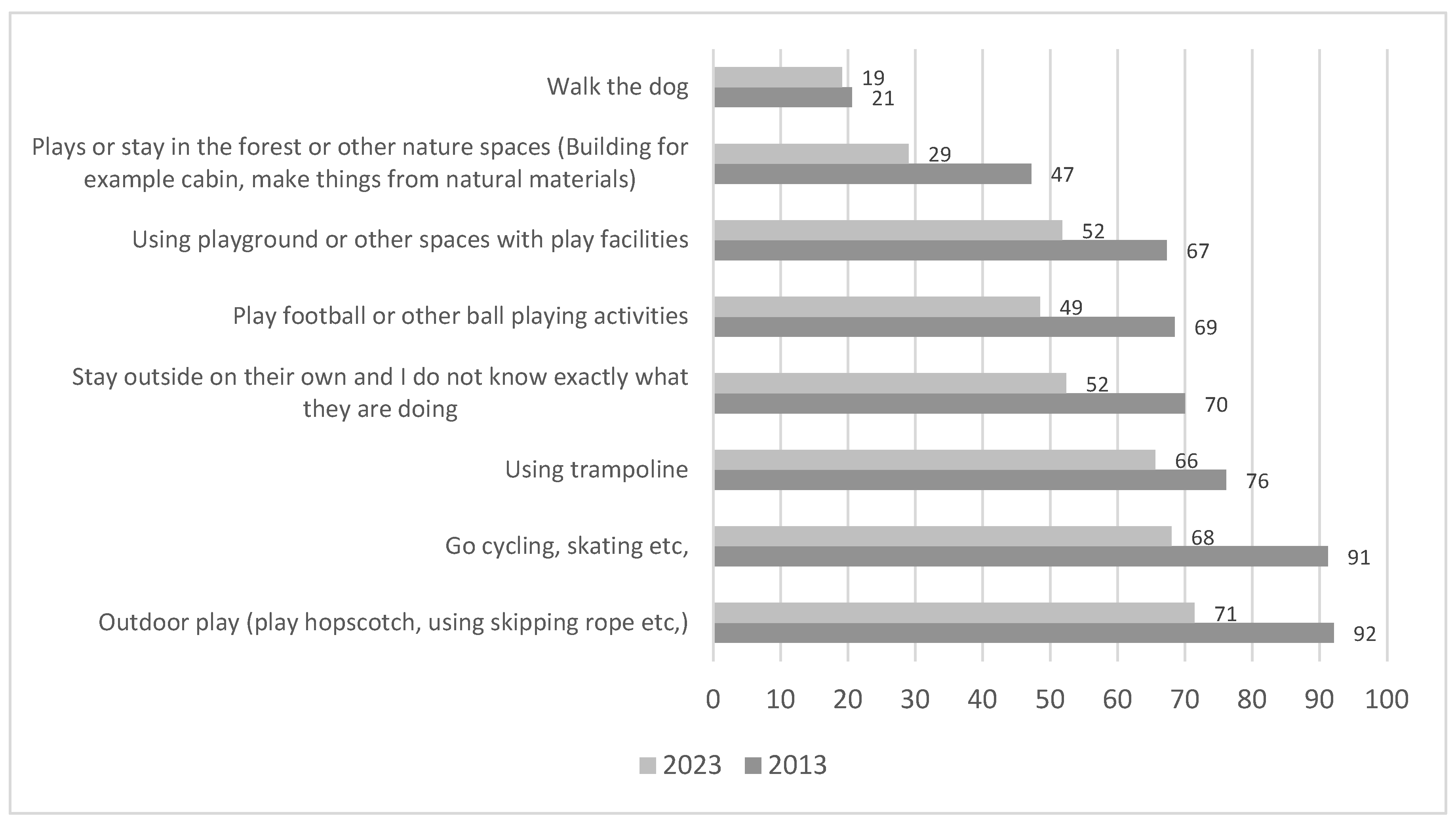

4.1. Changes in Children Outdoor Use in Different Neighbourhood Settings

4.2. Changes in Parents’ Experiences of Constraints for Children and Youth to Be Outdoor in Natural Settings

4.3. Constraints to Be Outdoor Associated with Demographic, Socio-Economic, and Social Variables

5. Discussion and Conclusion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hofferth, S. Changes in American children’s time, 1997-2003. Electronic International Journal of Time Use Research 2009, 6, 26–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mullan, K. 2018. “A child’s day: Trends in time use in the UK from 1975 to 2015.” The British Journal of Sociology 70(3): 997–1024. [CrossRef]

- Gill, T. 2014. “The benefits of children’s engagement with nature: A systematic literature review.” Children Youth and Environments 24(2): 10-34. [CrossRef]

- Chawla, L. 2015. “Benefits of nature contact for children.” Journal of Planning Literature 30(4): 433-452. [CrossRef]

- Tillmann, S., D. Tobin, W. Avison, and J. Gilliland. 2018. «Mental health benefits of interactions with nature in children and teenagers: a systematic review.” J. Epidemiol. Community Health 72 (10): 958–966. [CrossRef]

- Rantala, O. , and R. Puhakka, R. 2020. “Engaging with nature: nature affords well-being for families and young people in Finland.” Children’s Geographies 18(4): 490–503. [CrossRef]

- Chawla, L., K. Keena, I. Pevec, and E. Stanley 2014. “Green schoolyards as havens from stress and resources for resilience in childhood and adolescence.” Health & place 28: 1-13. [CrossRef]

- McCormick, R. 2017. “Does access to green space impact the mental well-being of children: A systematic review.” Journal of Pediatric Nursing 37: 3-7. [CrossRef]

- Vella-Brodrick, D. A. , and K. Gilowska. 2022. “Effects of nature (greenspace) on cognitive functioning in school children and adolescents: A systematic review.” Educational Psychology Review 34(3): 1217-1254. [CrossRef]

- Sandberg, M. 2012. ”De är inte ute så mycket. Den bostadsnära naturkontaktens betydelse och utrymmet i storstadsbarns vardagsliv.” PhD thesis, Institutionen för kulturgeografi och ekonomisk geografi. Göteborg: Handelshögskolan.

- Fasting, M.L. 2012. ”Vi leker ute!”: en fenomenologisk hermeneutisk tilnærming til barns lek og lekesteder ute.» PhD thesis, Fakultet for samfunnsvitenskap og teknologiledelse, Pedagogisk institutt. Trondheim: NTNU.

- Prince, H. Allin, E. B. H. Sandseter, and E. Ärlemalm-Hagsér. 2013. “Outdoor play and learning in early childhood from different cultural perspectives (Editorial).” Journal of Adventure Education & Outdoor Learning 13(3): 183–188. [CrossRef]

- Parker, R. , and S. Al-Maiyah. 2022. “Developing an integrated approach to the evaluation of outdoor play settings: rethinking the position of play value.” Children’s Geographies 20(1): 1–23. [CrossRef]

- UNICEF 1989. https://www.unicef.org/child-rights-convention.

- Brockman, R., R. Jago, K.R. Fox. 2011. “Children’s active play: self-reported motivators, constraints and facilitators.” BMC public health 11: 1-7.

- Soga, M., T. Yamanoi, K. Tsuchiya, T.F. Koyanagi, and T. Kanai, T. 2018. “What are the drivers of and barriers to children’s direct experiences of nature?” Landscape and Urban Planning 180: 114-120. [CrossRef]

- Skar, M. , and E. Krogh, E. 2009. “Changes in children’s nature-based experiences near home: from spontaneous play to adult-controlled, planned and organised activities.” Children’s Geographies 7(3): 339-354. [CrossRef]

- Skar, M. C. Wold, L.C., V. Gundersen, and L. O’Brien. 2016. “Why do children not play in nearby nature? Results from a Norwegian survey.” Journal of Adventure Education & Outdoor Learning 16(3): 239-255. [CrossRef]

- Larson, L. R., R. Szczytko, R., E.P. Bowers, L.E. Stephens, L. E., K.T. Stevenson, and M.F. Floy. 2019. “Outdoor time, screen time, and connection to nature: Troubling trends among rural youth?” Environment and Behaviour 51: 966–991. [CrossRef]

- Moore, S. A., G. Faulkner, R.E. Rhodes, M. Brussoni, T. Chulak-Bozzer, L.J. Ferguson, R. Mitra, N. O’Reilly, J.C. Spence, L.M. Vanderloo, and M.S. Trembl. 2020. “Impact of the COVID-19 virus outbreak on movement and play behaviours of Canadian children and youth: A national survey.” International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity 17:85. [CrossRef]

- Nathan, A., P. George, M. Ng, E. Wenden, P. Bai, Z. Phiri, and H. Christian. 2021. “Impact of COVID-19 restrictions on Western Australian children’s physical activity and screen time.” International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18: 2583. [CrossRef]

- Van Truong, M., M. Nakabayashi, and T. Hosaka. 2022. “How to encourage parents to let children play in nature: Factors affecting parental perception of children’s nature play.” Urban Forestry & Urban Greening 69: 127497. [CrossRef]

- Venter, Z., H. Figari, O. Krange, and V. Gundersen. 2022. “Environmental justice in a very green city: Spatial inequality in exposure to urban nature, air pollution and heat in Oslo, Norway.” Science of Total Environment. [CrossRef]

- Waite, S., F. Husain, B. Scandone, E. Forsyth, and H. Piggott, H. 2023. “‘It’s not for people like (them)’: structural and cultural constraints to children and young people engaging with nature outdoor schooling.” Journal of Adventure Education and Outdoor Learning 23(1): 54-73. [CrossRef]

- Barron, C., A. Beckett, M. Coussens, A. Desoete, N. Cannon Jones, H. LynchM. Prellwitz, and D. Fenney Salkeld. 2017. “Constraints to play and recreation for children and young people with disabilities: Exploring environmental factors.” De Gruyter Open Poland.

- Loebach, J. Sanches, J. Jaffe, and T. Elton-Marshall. 2021. “Paving the way for outdoor play: Examining socio-environmental constraints to community-based outdoor play.” International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18(7): 3617. [CrossRef]

- Arvidsen, J., T. Schmidt, S. Præstholm, S. Andkjær, A.S. Olafsson, J.V. Nielsen, and J. Schipperijn. 2022. “Demographic, social, and environmental factors predicting Danish children’s greenspace use.” Urban Forestry & Urban Greening 69: 127487. [CrossRef]

- Sallis, J. F. B. Cervero, W. Ascher, W., K.A. Henderson, M.K. Kraft, and J. Kerr. 2006. “An ecological approach to creating active living communities.” Annual Review of Public Health 27: 297–322. [CrossRef]

- Shaw, B., M. Bicket, B. Elliott, B. Fagan-Watson, E. Mocca, and M. Hillman.2015. “Children’s independent mobility: an international comparison and recommendations for action.” Policy Studies Institute.

- Skar, M., V. Gundersen, and L. O’Brien. 2016. “How to engage children with nature: Why not just let them play?” Children’s Geographies 14(5): 527-540. /: https. [CrossRef]

- Gundersen, V., M. Skår, L. O’Brien, L.C. Wold, and G. Follo. 2016. «Children and nearby nature: A nationwide parental survey from Norway.” Urban Forestry & Urban Greening 17: 116-125. [CrossRef]

- Statistics Norway. 2023. https://www.ssb.no/utdanning/barnehager/statistikk/barnehager (Retrieved 15.11.2023).

- Almeida, A., V. Rato, V., and Z.F. Dabaja. (2023). Outdoor activities and contact with nature in the Portuguese context: a comparative study between children’s and their parents’ experiences. Children’s Geographies 21(1): 108–122. [CrossRef]

- Morris, K. A. Arundell, L., Cleland, V., & Teychenne, M. (2020). Social ecological factors associated with physical activity and screen time amongst mothers from disadvantaged neighbourhoods over three years. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity 2020, 17, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crawford, D. W., E. L. Jackson, and G. Godbey. 1991. “A hierarchical model of leisure constraints.” Leisure Sciences 13: 309-320. [CrossRef]

- Walker, G. J. and R.J. Virden. 2005. Constraints on Outdoor Recreation. In: Jackson, E.L. (red.) 2005. Constraints to leisure (s. 201-219). State College, PA: Venture Publishing.

- Kyttâ, M., M. Oliver, E. Ikeda, E. Ahmadi, I. Omiya, and T. Laatikainen. 2018. “Children as urbanites: mapping the affordances Children’s Geographies and behavior settings of urban environments for Finnish and Japanese children.” Children’s Geographies. 16 (3): 319–332. [CrossRef]

- Morrissey, A. M. Scott, C., & Wishart, L. (2015). Infant and toddler responses to a redesign of their childcare outdoor play space. Children Youth and Environments 2015, 25(1), 29–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padilla-Walker, L. M., S. A. Hardy, and K.J. Christensen. 2011. “Adolescent hope as a mediator between parent-child connectedness and adolescent outcomes.” The Journal of Early Adolescence 31(6): 853-879. [CrossRef]

- Brussoni, M. L. Olsen, I. Pike, and D.A. Sleet. 2012. “Risky play and children’s safety: Balancing priorities for optimal child development.” International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 9(12): 3134–3148. [CrossRef]

- Foster, S. Villanueva, L. Wood, H. Christian, and B. Giles-Corti. 2014. “The impact of parents’ fear of strangers and perceptions of informal social control on children’s independent mobility.” Health & Place 26: 60–68. [CrossRef]

- Sandseter, E. B. H. 2012. “Restrictive safety or unsafe freedom? Norwegian ECEC practitioners’ perceptions and practices concerning children’s risky play.” Childcare in Practice 18(1): 83–101. [CrossRef]

- Fjortoft, I. 2004. “Landscape as playscape: The effects of natural environments on children’s play and motor development.” Children, Youth and Environments 14:23–44. [CrossRef]

- Sandseter, E. B. H. , and L.E.O. Kennair. 2011. “Children’s risky play from an evolutionary perspective: The anti-phobic effects of thrilling experiences.” Evolutionary Psychology 9(2): 257–284. [CrossRef]

- Nordbakke, S. 2019. “Children’s out-of-home leisure activities: changes during the last decade in Norway.” Children’s Geographies 17(3): 347-360. [CrossRef]

- Wold, L.C., T. B. Broch, O.I. Vistad, S.K. Selvaag, V. Gundersen, and H. Øian. 2022. Barn og unges organiserte friluftsliv. Hva fremmer gode opplevelser og varig deltagelse? NINA Rapport 2084. Norsk institutt for naturforskning.

- Borge, A.I.H. Nordhagen, and K.K. Lie. 2003. “Children in the environment: Forest day-care centers.” The History of the Family 8: 605–618. [CrossRef]

- Nilsen, A. H. , and C.M. Hägerhäll. 2012. ”Impact of space requirements on outdoor play areas in public kindergartens.” Nordic Journal of Architectural Research 24(2).

- Karsten, L. 2005. “It all used to be better? Different generations on continuity and change in urban children’s daily use of space.” Children’s Geographies 3(3): 275-290. [CrossRef]

- Harper, N. J. 2017. “Outdoor risky play and healthy child development in the shadow of the “risk society”: A forest and nature school perspective.” Child & Youth Services 38(4): 318-334. [CrossRef]

- Sandseter, E. B. H. , and O.J. Sando. 2016. “We don’t allow children to climb trees”: how a focus on safety affects Norwegian children’s play in early-childhood education and care settings.” American Journal of Play 8(2): 178-200.

- Sandseter, E. B. H. 2007. “Risky play among four-and five-year-old children in preschool.” Conference “Vision into practice: Making quality a reality in the lives of young children” 248-256. Dublin.

- The Norwegian Media Authority (2023) Retrieved February 2024.

- Fan, W. , & Z. Yan. 2010. “Factors affecting response rates of the web survey: A systematic review.” Computers in Human Behavior 26: 132–139. [CrossRef]

- Sammut, R. , Griscti, O., and I. J. Norman. 2021. “Strategies to improve response rates to web surveys: A literature review.” International Journal of Nursing Studies 123, Article 104058. [CrossRef]

- Holloway, S. L. and H. Pimlott-Wilson, H. 2014. “Enriching children, institutionalizing childhood? Geographies of play, extracurricular activities, and parenting in England.” Annals of the Association of American Geographers 104(3): 613-627. [CrossRef]

- Chawla, L. 2002. “Insight, creativity thoughts on the environment”: integrating children and youth into human settlement development.” Environment and Urbanization 14(2): 11-22. [CrossRef]

- Chawla, L. 2007. “Childhood experiences associated with care for the natural world: A theoretical framework for empirical results.” Children, Youth and Environments 17(4): 144-170. [CrossRef]

- Larson, L. R. W. Whiting, J. W., and G.T. Green. 2011. “Exploring the influence of outdoor recreation participation on pro-environmental behaviour in a demographically diverse population.” Local Environment 16: 67-86. [CrossRef]

- Wold, L.C., M. Skar, and H. Øian. 2020. Barn og unges friluftsliv. NINA Rapport 1801. Norsk institutt for naturforskning.

- Van Heel, B. F., R. J. G. van den Born, and M.N. C. Aarts. 2023. “Everyday childhood nature experiences in an era of urbanisation: an analysis of Dutch children’s drawings of their favourite place to play outdoors.” Children’s Geographies 21(3): 378–393. [CrossRef]

| Survey details | Response options |

|---|---|

| A. Questions about children outside use in different neigbourhood settings | |

| What are your children doing outside in the nearby environment in their leisure time, and how often? | [dropdown, 5 categories:

|

| B. Demographic characteristics | |

| Parent: Age and gender,Income, Education, Sole parent, Ethnicity, Post code, Family structure, Number of children, | [dropdown, age - continues] [dropdown, gender] [dropdown, income, 16 categories] [dropdown, education, 6 categories] [dropdown, sole parent, yes/no] [dropdown, ethnicity, 7 categories] [dropdown, family structure, 3 categories] [dropdown, number of children, specify] [dropdown, rural vs. urban living, 4 categories] |

| Child: Age and gender Rural vs. urban living |

[dropdown, age - continues] [dropdown, gender] [dropdown, urban-rural, 4 categories] [dropdown, postal code, specify] |

| C. Constraints for nature use To what extent do you agree or disagree that the following statements are a hindrance for the child to visit nature or green spaces? |

[dropdown, Likert scale 1–5, 1= completely disagree, 5 = completely agree, 19 statements]

|

| To what extent do you agree or disagree that the following statements are a hindrance for the child to visit nature or green spaces? | Year | N | Mean | Std. Deviation | Std. Error Mean | Test statistics |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Distance to nature and other green areas is too far | 2013 | 3162 | 1,74 | 1,153 | 0,020 | t3587=-7,346; *p<.000; 2023>2013 WW: t3325=-6,903; *p<.000; 2023>2013 |

| 2023 | 426 | 2,18 | 1,356 | 0,066 | ||

| The child is too busy in leisure time (organized sports and leisure activities) | 2013 | 3163 | 2,56 | 1,212 | 0,022 | t3586=-7,692; *p<.000; 2023>2013 WW: t3325=-8,545; *p<.000; 2023>2013 |

| 2023 | 426 | 3,04 | 1,236 | 0,060 | ||

| I/we parents are concerned about traffic | 2013 | 3166 | 2,51 | 1,312 | 0,023 | t3591=-2,470; p=.014; 2023≈2013 WW: t3325=-0,520; *p=.603; 2023≈2013 |

| 2023 | 427 | 2,68 | 1,302 | 0,063 | ||

| There is too much bad weather | 2013 | 3155 | 2,03 | 1,123 | 0,020 | t3581=-5,438; *p<.000; 2023>2013 WW: t3325=-5,199; *p<.000; 2023>2013 |

| 2023 | 427 | 2,35 | 1,227 | 0,059 | ||

| School homework takes too much time | 2013 | 3166 | 2,53 | 1,135 | 0,020 | t3591=-5,438; p=.619; 2023≈2013 WW: t3325=-0,620; *p=.535; 2023≈2013 |

| 2023 | 427 | 2,49 | 1,216 | 0,059 | ||

| Too high expenses to reach attractive nature and green areas | 2013 | 3159 | 1,34 | 0,743 | 0,013 | t3585=-6,874; *p<.000; 2023>2013 WW: t3325=-7,508; *p<.000; 2023>2013 |

| 2023 | 427 | 1,61 | 0,891 | 0,043 | ||

| Too high demand for equipment, cloths, shoes etc. | 2013 | 3172 | 1,51 | 0,860 | 0,015 | t3597=-5,974; *p<.000; 2023>2013 WW: t3325=-7,508; *p<.000; 2023>2013 |

| 2023 | 427 | 1,78 | 0,952 | 0,046 | ||

| The child has poor motoric skill | 2013 | 3170 | 1,24 | 0,701 | 0,012 | t3595=-5,584; *p<.000; 2023>2013 WW: t3325=-5,883; *p<.000; 2023>2013 |

| 2023 | 427 | 1,45 | 0,898 | 0,043 | ||

| The child prefers being indoors | 2013 | 3162 | 2,48 | 1,226 | 0,022 | t3587=-9,225; *p<.000; 2023>2013 WW: t3325=-10,554; *p<.000; 2023>2013 |

| 2023 | 427 | 3,07 | 1,279 | 0,062 | ||

| The nature and green areas are poorly facilitated | 2013 | 3139 | 1,58 | 0,920 | 0,016 | t3564=-4,250; *p<.000; 2023>2013 WW: t3325=-4,571; *p<.000; 2023>2013 |

| 2023 | 427 | 1,78 | 1,057 | 0,051 | ||

| The child uses so much time on data and other screens that to be outside is downgraded | 2013 | 3166 | 2,34 | 1,221 | 0,022 | t3590=-7,284; *p<.000; 2023>2013 WW: t3325=-9,030; *p<.000; 2023>2013 |

| 2023 | 426 | 2,80 | 1,339 | 0,065 | ||

| The child does not want to play outdoors in nature | 2013 | 3159 | 2,08 | 1,107 | 0,020 | t3584=-9,278; *p<.000; 2023>2013 WW: t3325=-10,962; *p<.000; 2023>2013 |

| 2023 | 427 | 2,61 | 1,192 | 0,058 | ||

| The child lacks friends who want and have time to visit nature and green areas | 2013 | 3141 | 2,21 | 1,166 | 0,021 | t3566=-9,276; *p<.000; 2023>2013 WW: t3325=-10,590; *p<.000; 2023>2013 |

| 2023 | 426 | 2,77 | 1,259 | 0,061 | ||

| I/we parents find it unsafe in nature and green areas | 2013 | 3159 | 1,45 | 0,858 | 0,015 | t3585=-5,263; *p<.000; 2023>2013 WW: t3325=-4,224; *p<.000; 2023>2013 |

| 2023 | 427 | 1,69 | 1,002 | 0,048 | ||

| I/we parents lack a social network that could increase activity with the child outside | 2013 | 3154 | 1,85 | 1,138 | 0,020 | t3579=-7,762; *p<.000; 2023>2013 WW: t3325=-7,602; *p<.000; 2023>2013 |

| 2023 | 427 | 2,31 | 1,263 | 0,061 | ||

| I/we parents prioritize playing and other activities indoors above being outside | 2013 | 3159 | 1,93 | 1,029 | 0,018 | t3584=-6,533; *p<.000; 2023>2013 WW: t3325=-6,619; *p<.000; 2023>2013 |

| 2023 | 427 | 2,28 | 1,123 | 0,054 | ||

| I/we parents have a time schedule filled up with job, activities, sports, and other things and to motivate the child to be outside is downgraded | 2013 | 3162 | 2,22 | 1,108 | 0,020 | t3587=-5,519; *p<.000; 2023>2013 WW: t3325=-5,713; *p<.000; 2023>2013 |

| 2023 | 427 | 2,54 | 1,174 | 0,057 | ||

| I/we parents find school work more important than motivating the child to be outside in nature and other green areas | 2013 | 3156 | 2,28 | 1,097 | 0,020 | t3580=-3,656; *p<.000; 2023>2013 WW: t3325=-3,777; *p<.000; 2023>2013 |

| 2023 | 426 | 2,48 | 1,133 | 0,055 | ||

| I/we parents find participation in sports and other leisure activities more important than motivating the child to be outside in nature and other green areas | 2013 | 3146 | 2,18 | 1,081 | 0,019 | t3571=-2,951; *p=.003; 2023>2013 WW: t3325=-2,797; *p<.000; 2023>2013 |

| 2023 | 427 | 2,34 | 1,020 | 0,049 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).