1. Introduction

Agribusiness lies at the nexus of several urgent global transformations, including environmental degradation, climate volatility, digital disruption, demographic shifts, and the reorganization of global value chains. These structural forces are reshaping how agricultural systems are governed, how value is generated and distributed, and how innovation emerges and diffuses within national and transnational food systems [

1,

2] In low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), agribusiness holds more than just economic significance; it serves as a foundation for rural development, poverty reduction, food security, and climate resilience [

3,

4,

5]. In countries such as Albania, Bangladesh, and Ethiopia, transforming agribusiness systems is essential not only for improving livelihoods but also for navigating overlapping ecological and technological transitions [

6].

Despite this urgency, much of the existing research and policy practice in agribusiness innovation continues to rely on conventional theoretical paradigms that fail to capture and explain, to the fullest extent, the dynamic and complex nature of agribusiness innovation adoption and adaptation. In other words, mainstream approaches, particularly in agricultural economics, tend to adopt neoclassical or structuralist lenses that view innovation as a linear, exogenous process driven by research breakthroughs and technology transfer [

7,

8]. These models often reduce innovation to a question of productivity gains, overlooking the complex social, political, and institutional dynamics that govern innovation processes in real-world contexts [

9,

10]. Moreover, they typically presume institutional homogeneity across regions and countries, failing to account for how historically rooted, culturally specific, and politically shaped institutional configurations affect the evolution and diffusion of innovation [

11,

12].

Such limitations are especially problematic in LMICs, where formal institutions may be underdeveloped, fragmented, or in flux. Agricultural innovation in these settings does not occur in a vacuum but emerges from the interaction of firms, markets, public institutions, and civil society, each shaped by diverse histories, power relations, and local learning routines. Feedback loops between policy actors, market signals, and firm behavior are often weak or absent, and learning is constrained by infrastructural and informational deficits [

13]. As Hall et al. [

14] and Williams, Hailemariam, and Allard [

15] argue, understanding how innovation systems evolve in LMICs requires moving beyond technical solutions and recognizing the co-evolutionary dynamics between institutions, actors, and technologies.

To address these conceptual and empirical gaps, this study applies an evolutionary economics framework to examine how agribusiness innovation systems operate in three LMICs—Albania, Bangladesh, and Ethiopia. Evolutionary economics theory offers a dynamic, non-linear understanding of innovation, emphasizing institutional routines, feedback mechanisms, historical path-dependence, and selection environments [

16,

17,

18]. This approach foregrounds the role of systemic learning, institutional adaptation, and endogenous change processes, which indicate factors often marginalized in traditional innovation theory. While widely applied in industrial and technological sectors [

19,

20], evolutionary perspectives remain underutilized in agricultural development, particularly in comparative studies across LMICs [

21,

22].

In addition, empirical work applying evolutionary economics in agriculture has typically been confined to single-country studies. In Ethiopia, for example, Williams, Hailemariam, and Allard [

15] as well as Spielman and Kelemework [

16] have examined the impact of agro-industrial policy and central planning on institutional learning and network formation. In Albania, scholars such as Muça et al. [

17], Gërdoçi [

18], and Kuzumi [

19] have studied agrifood innovation amid post-socialist restructuring, focusing on donor influence, institutional memory, and policy volatility. In Bangladesh, researchers have highlighted how hybrid governance systems, characterized by NGO-state collaboration and digital experimentation, have enabled more adaptive innovation in agro-processing and value chain upgrading [

20,

21,

22].

However, few studies have undertaken comparative, cross-country analysis that systematically applies evolutionary economics theory to explore how institutional diversity shapes agribusiness innovation outcomes. This absence is notable, as cross-national variation in innovation performance often emerges not from differences in technological availability or economic inputs, but from divergent institutional arrangements, learning routines, and feedback mechanisms [

23,

24]. Understanding these systemic differences is critical for designing context-appropriate innovation policies that avoid the pitfalls of “best practice transfer” across institutional environments [

25].

Specifically, a central limitation in current literature is the tendency to treat institutional context as a static backdrop, rather than as an active, evolving component of the innovation process. Policy analyses continue to frame innovation as a function of technology adoption or capital investment, without considering how market structure, policy clarity, governance coherence, and institutional feedback influence innovation trajectories over time [

24]. The interaction between evolving institutional ecosystems and firm-level behavior remains under-theorized, especially under conditions of environmental stress and digital transformation.

In concrete terms, Ethiopia’s centralized model of agro-industrial development has generated strong vertical coordination, with clear lines of authority and institutional embeddedness. However, this structure has limited opportunities for horizontal learning and grassroots experimentation, thereby curbing systemic adaptability [

15,

16]. In contrast, Bangladesh presents a more decentralized governance model, with pluralistic institutions, strong NGO engagement, and robust digital infrastructure that enable flexible learning and rapid feedback [

20,

21]. Albania, on the other hand, represents a post-socialist institutional environment marked by fragmentation, policy inconsistency, and donor dependency—factors that collectively undermine institutional memory and learning continuity [

17,

18,

19].

This study addresses these gaps by conducting a comparative analysis of agribusiness innovation systems in the three contexts. These contexts were deliberately selected using theoretical replication logic [

26], which favors cases expected to yield contrasting outcomes based on well-grounded theoretical propositions. The research is grounded in a sequential mixed-methods design, combining over 600 qualitative interviews with a structured survey of 75 agribusiness firms across the three countries. The firms represent diverse subsectors, scales, regions, and value chain positions, enabling the analysis of intra- and inter-country institutional dynamics.

The central hypothesis guiding this work is that institutional diversity, more than technological access or firm size, is likely to shape the pace, direction, and sustainability of agribusiness innovation. Firms do not operate in isolation but are embedded within evolving institutional systems that influence their capacity to learn, experiment, and respond to change. Market signals, policy clarity, and innovation incentives are filtered through these systems, often producing divergent innovation outcomes in otherwise comparable settings [

16,

24].

By extending evolutionary economics into the domain of agrarian transformation, the study makes three key contributions. Theoretically, it enriches agricultural innovation literature by integrating concepts such as institutional memory, co-evolution, and adaptive learning into agribusiness analysis [

16,

17,

21]. Empirically, it addresses a methodological gap by providing a cross-country, firm-level comparison of innovation systems grounded in a common analytical framework. Most prior studies rely on macro-level indicators or abstract modeling; this study instead highlights the micro-level mechanisms through which institutions shape innovation. From a policy perspective, the findings challenge dominant models that promote externally designed “best practices” and one-size-fits-all strategies. The study calls instead for context-sensitive institutional design, rooted in real-time feedback, local learning systems, and digital responsiveness. In doing so, this study offers a more grounded and actionable foundation for building inclusive, adaptive, and robust agribusiness innovation systems in the Global South—systems capable of withstanding the shocks and uncertainties posed by climate change, technological disruption, and geopolitical reordering.

2. The Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Design: Comparative Sequential Mixed Methods

This study employs a comparative sequential mixed-methods research design grounded in the evolutionary economics framework to analyze how innovation processes unfold in agribusiness sectors across Albania, Bangladesh, and Ethiopia. To operationalize the method, the study used, first, 600 semi-structured interviews across 75 agribusinesses, identifying core themes: institutional engagement, learning practices, and feedback mechanisms. These themes were then used to construct survey instruments, which quantified firm behaviors on Likert scales. Key constructs, such as “institutional embeddedness” and “policy coherence”, were operationalized as indices and standardized using z-scores. Principal Component Analysis (PCA) verified construct reliability. Hierarchical linear modeling (HLM) accounted for firms nested within country contexts, allowing the study to explore both within- and between-country effects on innovation performance.

The rationale for adopting this design is both epistemological and practical. From an epistemological standpoint, evolutionary economics views socio-economic systems as complex, non-linear, and historically contingent, which requires a research strategy capable of capturing both structure and agency [

27,

28]. This framework highlights the role of historical context and institutional arrangements in shaping innovation, particularly within agriculture and agribusiness, where innovation is not linear but co-evolves with market and policy dynamics [

29,

30].

Practically, a mixed-methods design allows for qualitative exploration of localized innovation dynamics followed by quantitative generalization and hypothesis testing across cases. Mixed-method strategies are increasingly employed in agribusiness innovation studies to navigate the institutional, technological, and organizational complexities inherent in sectoral innovation systems [

31,

32,

33]. This approach is also supported by frameworks such as technological innovation systems and agricultural knowledge and innovation systems (AKIS), which emphasize systemic interactions between actors, institutions, and technologies [

34,

35].

The design follows a sequential exploratory strategy [

36], where qualitative data collection and thematic analysis precede and inform the quantitative phase. The first phase includes semi-structured interviews with key stakeholders across 75 agribusiness firms, generating 600 responses, focused on identifying the dimensions of institutional routines, organizational learning, and policy feedback. These qualitative findings were then used to design structured questionnaires, which allowed for the econometric modeling of contextually grounded innovation constructs. This approach is also aligned with practices in innovation systems research, where scholars emphasize the integration of structural indicators (e.g., R&D investment, firm size) with behavioral dimensions like inter-organizational learning and adaptive governance [

37,

38]. The combination of cross-country (context) comparison and mixed methods allows for a controlled examination of institutional diversity and its implications for agrarian innovation.

2.2. Theoretical Foundations: Evolutionary Economics and Innovation Systems

At the foundation of this study is the evolutionary economics framework, an approach that challenges the assumptions of conventional neoclassical economics. Unlike the neoclassical model, which assumes perfect information, rational optimization, and equilibrium, evolutionary economics posits that economic agents operate under bounded rationality, meaning their decisions are limited by incomplete knowledge, cognitive constraints, and institutional routines [

39]. This perspective views the economy not as a system tending toward equilibrium, but as a constantly evolving structure shaped by the accumulation of knowledge, experience, and institutional adaptation over time.

Innovation is conceptualized in this study as an adaptive system process, guided by bounded rationality, co-evolution, and feedback-rich institutional environments [

40,

41] This may include processes, services, or products. This view avoids linear assumptions and informs the study’s empirical structure. The study avoids redundancy by building directly on this conceptual base in the empirical design. It reconceptualizes innovation as an adaptive and systemic process that is nonlinear, historically contingent, and shaped by institutional routines and thus challenging the technocentric view common in agribusiness literature [

42]. Crucially, firms innovate not by optimizing in a fixed environment but by experimenting, learning, and adjusting in response to feedback from their institutional and market surroundings [

43]. This explains why certain innovations succeed or fail not simply due to intrinsic technical superiority, but because of the complex, co-evolutionary interplay among technology, institutions, and market actors.

In the context of agribusiness, this framework redirects analysis from simplistic input-output or productivity models toward the dynamic accumulation of capabilities, institutional supports, and policy frameworks that shape how innovation unfolds. Agribusiness sectors often function under conditions of uncertainty, informal norms, and diverse actor interactions. Thus, innovation systems in these sectors are best understood as networks of interacting firms, research organizations, government agencies, and farmer associations—each playing a role in the generation, dissemination, and application of knowledge [

24].

As Dosi articulates, technological trajectories evolve within institutional settings that constrain and enable innovation [

44]. Path dependency, which is the idea that historical decisions and institutional arrangements shape current innovation capabilities, is a core insight here. For instance, in many developing economies, legacy systems from colonial or centrally planned regimes continue to influence agricultural innovation systems, from extension services to input markets. This evolutionary lens is especially pertinent for developing economies, where agribusiness transformation typically occurs within a non-linear and institutionally fragmented landscape [

45]. Unlike high-income countries where innovation ecosystems are more cohesive and stable, agribusiness in developing economies must navigate challenges such as informal governance, erratic policy regimes, donor dependence, and weak state capacity [

46]. Here, innovation may be less about technological breakthroughs and more about context-specific learning, institutional bricolage, and adaptation to shifting external constraints.

By applying evolutionary economics to this context, the study is, thus, able to capture critical dynamics often neglected in mainstream development economics, such as (a) institutional lock-in—past choices limit the range of current innovation options [

42]; (b) historical legacies—long-standing institutional arrangements continue to influence actors’ strategies and capacities; (c) feedback mechanisms—innovations can reshape the environment in which they operate, prompting further institutional evolution [

47]; and (d) co-evolution of public and private actors—innovation is often a joint outcome of interactions between state bodies, NGOs, and firms [

48]. Moreover, contemporary contributions to innovation systems theory, especially in agricultural and food contexts, have stressed the importance of interactive learning, boundary organizations, and innovation intermediaries that facilitate communication across institutional divides [

49]. These elements align well with evolutionary economics, which values decentralized experimentation and diversity of actors as sources of innovation.

2.3. Operationalization of the Framework: Linking Qualitative and Quantitative Methods

The translation of evolutionary economics into empirical research requires more than selecting compatible methods. It demands a methodological pluralism that reflects the complexity, historicity, and multi-actor dynamics of innovation systems. Accordingly, this study employs a sequential mixed-methods research design that aligns theoretical commitments to evolutionary economic thought with a reasonable methodological rigor and contextual sensitivity. This design enables the discovery of context-specific mechanisms of innovation (variation, selection, retention) and then tests these mechanisms across larger populations, for generalizability and cross-case comparison.

In the first phase, the study undertook semi-structured qualitative interviews with agribusiness stakeholders, including entrepreneurs, extension agents, policy officials, and NGO facilitators, in Albania, Bangladesh, and Ethiopia. Using grounded theory principles [

50], the data sets were subjected to open and axial coding to extract dominant themes. These themes focused on innovation behaviors (e.g., trial-and-error practices, risk-sharing strategies), institutional interaction (e.g., engagement with state and donor agencies), and learning processes (e.g., peer-to-peer knowledge diffusion, informal apprenticeships).

Such inductive work reflects the iterative and interpretive nature of knowledge generation advocated in evolutionary innovation studies [

51]. The aim was to uncover endogenous variables rooted in local conditions rather than impose a priori constructs. In the second phase, these qualitatively derived themes were transformed into structured survey variables, thereby enabling statistical generalization while preserving theoretical reliability. The survey instrument included (a) structural variables such as firm size, export orientation, age, and exposure to public policy schemes, and (b) dynamic behavioral variables such as the frequency of external learning interactions, participation in institutional partnerships, and internal feedback and adaptation cycles.

The use of multi-level regression models allowed the analysis to accommodate nested data structures (e.g., firms within regions, regions within countries), addressing both intra-country heterogeneity and inter-country variation. Hierarchical clustering was also applied to group firms based on innovation behavior profiles, providing insights into cross-national patterns and localized innovation archetypes [

52,

53]. Such a combined qualitative-quantitative strategy is increasingly regarded as essential for investigating National Innovation Systems (NIS) in agriculture, especially in developing economies, where informal knowledge networks, tacit learning, and non-market coordination mechanisms are often more influential than formal R&D indicators [

54,

55]. Indeed, evolutionary innovation scholars emphasize that surveys alone fail to capture the institutional embeddedness and co-evolutionary dynamics that characterize innovation processes in agriculture [

56,

49]. Mixed-methods research helps bridge this gap by linking actor-level narratives to system-level patterns.

2.4. Comparative Logic: Institutional Diversity Across Case Countries

The inclusion of Albania, Bangladesh, and Ethiopia as case studies is not incidental but strategically designed to explore how institutional diversity shapes agribusiness innovation. Each context represents a unique institutional configuration, offering a “most different systems” design that holds the sectoral domain (agribusiness) constant while varying national innovation and governance regimes. This design enhances explanatory leverage in understanding how evolutionary mechanisms, which include learning, routine formation, institutional adaptation, manifest under divergent institutional pressures and supports.

Albania: Post-Socialist Institutional Voids

Albania demonstrates a post-socialist transition economy, where the legacy of centralized planning and subsequent liberalization has produced fragmented governance, low state capacity, and institutional voids in agribusiness [

57]. Innovation in this context is often donor-driven, with international agencies playing outsized roles in providing knowledge, funding, and coordination due to the weak domestic research infrastructure [

58]. The public agricultural R&D system remains under-resourced, and linkages between universities, firms, and policymakers are minimal [

59]. Agribusiness innovation is thus piecemeal, opportunistic, and highly dependent on external incentives.

Bangladesh: Hybrid and Pluralistic System

Bangladesh has developed a hybrid innovation system that blends NGO-driven experimentation, public sector initiatives, and market-led adaptations [

60]. It is one of the few countries where NGOs (e.g., BRAC) play a direct role in technology dissemination, value chain development, and farmer support, alongside formal public research institutions [

61]. This pluralistic governance model supports innovation through networked interactions rather than centralized planning, enabling more adaptive and inclusive pathways. The presence of microfinance institutions, rural cooperatives (farmer associations), and agri-entrepreneurship hubs facilitates innovation even in areas underserved by the state [

62]. Importantly, the Bangladeshi case demonstrates how institutional bricolage [

63]—the creative recombination of formal and informal structures—can enhance agricultural innovation.

Ethiopia: State-Led Innovation and Centralization

Ethiopia represents a third model: a state-led innovation architecture characterized by centralized planning, state-donor coordination, and policy-driven modernization. The government has launched ambitious initiatives such as the Agro-Industrial Parks (AIP) Initiative, designed to industrialize agriculture through clusters and public-private partnerships [

64]. The Ethiopian Institute of Agricultural Research (EIAR) and regional agricultural universities are key institutional anchors, but the system remains hierarchical and top-down, with limited horizontal feedback mechanisms [

65]. Donors such as GIZ, USAID, World Bank, SDC, and Sida are active, but typically operate within the parameters set by national development strategies, making Ethiopia a prototypical case of directed institutional change [

66].

The study’s comparative strategy is not merely illustrative; it is analytically essential, as elaborated in section 2.5. By controlling for sectoral conditions (agribusiness) while varying institutional and governance regimes, the study enables a systematic examination of how evolutionary processes like learning, feedback, and routine development are influenced by the strength and structure of institutional linkages (formal vs. informal), the role of external actors (donors, NGOs, multilateral institutions), and the orientation of public policy (liberal, pluralist, centralized). This comparative institutionalism enhances internal validity by grounding abstract theoretical mechanisms in distinct empirical contexts, and it strengthens external validity by illustrating how innovation dynamics can be generalized or delimited based on institutional environments.

2.5. Sampling and Justification of Case Selection

This study employs a purposive comparative case sampling strategy, focusing on three LMICs (Albania, Bangladesh, and Ethiopia) to explore how institutional configurations shape innovation trajectories in agribusiness. The selection of these contexts was theoretically and strategically grounded, aiming to maximize institutional heterogeneity while ensuring analytical comparability. Each context represents a distinct agrarian development path and policy logic, allowing for a rich investigation of how national innovation systems mediate firm-level adaptation and transformation processes.

Because of the nature of the contexts, the study uses a “most-different systems” design to compare how institutional structures shape agribusiness innovation. As mentioned above, Albania shows a post-socialist state with fragmented institutions; Bangladesh represents a pluralistic and adaptive governance model; and Ethiopia reflects a centralized, state-led approach.

Table 1 summarizes institutional characteristics, innovation policy orientation, and digital readiness across the three countries. This comparative logic enables testing of the hypothesis that institutional diversity, not just resource endowments, determines innovation trajectories.

As briefly mentioned earlier, the justification for focusing on these three contexts draws from both their empirical importance in international agricultural development and their theoretical relevance within the study’s evolutionary economics framework. Ethiopia, for instance, has pursued a state-led model of agrarian transformation through centralized industrial policy instruments, such as the Integrated Agro-Industrial Parks (IAIPs), heavily supported by development partners like the UNIDO and the World Bank [

67]. This policy architecture provides a high-coordination, high-control institutional setting, conducive to analyzing path dependency and bureaucratic inertia.

In contrast, Bangladesh presents a decentralized and pluralistic innovation environment, where agribusiness innovation has evolved through a complex interplay of NGOs, private sector actors, and fragmented public agencies. The country has demonstrated notable resilience and dynamism in the agrifood sector, particularly in horticulture and fisheries, albeit with challenges in formal institutional coherence [

68]. Albania, as a post-socialist economy in Southeast Europe, offers yet another distinct case. Its agribusiness sector has undergone significant liberalization and privatization, yet it struggles with institutional voids, weak extension systems, and fragmented land ownership structures, which impede coordinated innovation [

17,

69].

These three contexts were selected using theoretical replication logic [

25], a purposeful case selection strategy that prioritizes theoretical contrast over statistical representativeness. The rationale behind this design is to yield divergent findings based on predictable, theory-informed differences, thereby enhancing the external validity of the study. In doing so, the study tests its core hypothesis: that agribusiness innovation in LMICs is shaped not by a single, universal mechanism but through context-dependent institutional dynamics and adaptive routines. The primary units of analysis were agribusiness firms operating across different stages of the agricultural value chain, including primary production, aggregation, processing, logistics, and distribution. A total of 75 firms—25 from each country—were selected using maximum variation sampling, a strategy designed to capture a broad spectrum of perspectives and operating conditions within bounded national systems [

70].

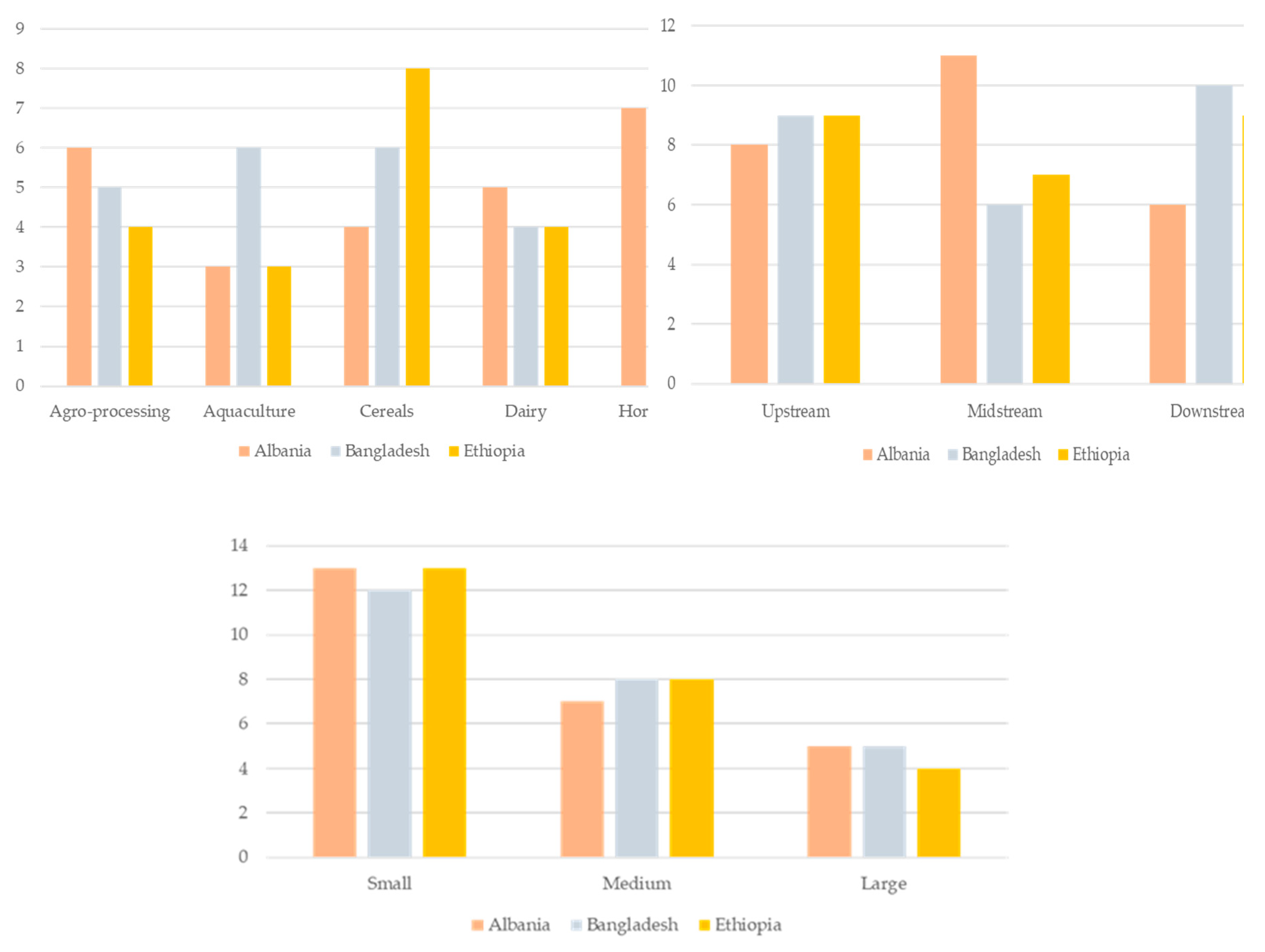

To ensure analytical depth and intra-country diversity, firms were selected to reflect variations along four dimensions, as shown in

Figure 1. First, they represented a range of agricultural subsectors, including horticulture, dairy, cereals, aquaculture, and agro-processing, each subject to distinct market and regulatory conditions. Second, the sample included both SMEs and larger agribusinesses to explore how scale influences innovation capacity and institutional engagement. Third, firms were chosen from diverse agro-ecological zones within each country to account for spatial differences in infrastructure, policy enforcement, and market access. Finally, their position in the value chain—whether as upstream producers, midstream processors and aggregators, or downstream logistics and marketing firms—was considered crucial for analyzing how innovation diffuses and how feedback mechanisms function throughout the supply chain. This layered sampling approach enabled a nuanced understanding of how innovation emerges and travels through different institutional and ecological contexts.

In subsector distribution, Ethiopia is concentrated in cereals, while Bangladesh leads in aquaculture and horticulture. Albania shows a balanced presence, especially in agro-processing. This reflects different agricultural priorities and market conditions across the countries. Regarding firm size, small enterprises dominate in all three, with around 13–14 firms each. Medium firms are present in moderate numbers, while large firms are few, especially in Ethiopia. This pattern highlights a reliance on small-scale operations across the sector. In terms of value chain position, Albania is strongest in midstream activities like processing, Bangladesh in downstream logistics and marketing, and Ethiopia has a more balanced but production-focused structure. These differences suggest varied levels of value addition and market integration.

Figure 2.

Firms by country, subsector, size, and value chain position.

Figure 2.

Firms by country, subsector, size, and value chain position.

The spatial distribution of the 75 agribusiness enterprises was across the key administrative regions of the three countries. In Albania, firms were distributed across Central, Northern, and Southern Albania, ensuring coverage of diverse agro-ecological zones. In Bangladesh, firms were selected from Dhaka, Rajshahi, and Chittagong Divisions, reflecting regional diversity in market access and institutional presence. In Ethiopia, enterprises were drawn from the Oromia, Amhara, and Southern Nations, Nationalities, and Peoples’ Region (SNNPR), which represent distinct agricultural and infrastructural contexts. This regional stratification allows the study to account for spatial heterogeneity in policy enforcement, innovation diffusion, and market connectivity.

Firm selection was guided by national agribusiness directories, government agricultural agencies, chambers of commerce, and donor project lists. Initial contacts were validated through key informant consultations, followed by targeted invitations. To further ensure institutional diversity and avoid sample bias, the study conducted pre-screening assessments through scoping visits and pilot interviews before full data collection. The rationale for case-bound sampling at the firm level is grounded in the evolutionary economics literature, which emphasizes the role of firm-specific routines, capabilities, and institutional embeddings in shaping innovation outcomes [

71,

9]. Agribusiness firms are conceptualized not as passive adopters of innovation but as active, historically situated agents whose strategies reflect adaptive learning within given institutional constraints.

2.6. Qualitative Data Collection: Semi-Structured Interviews

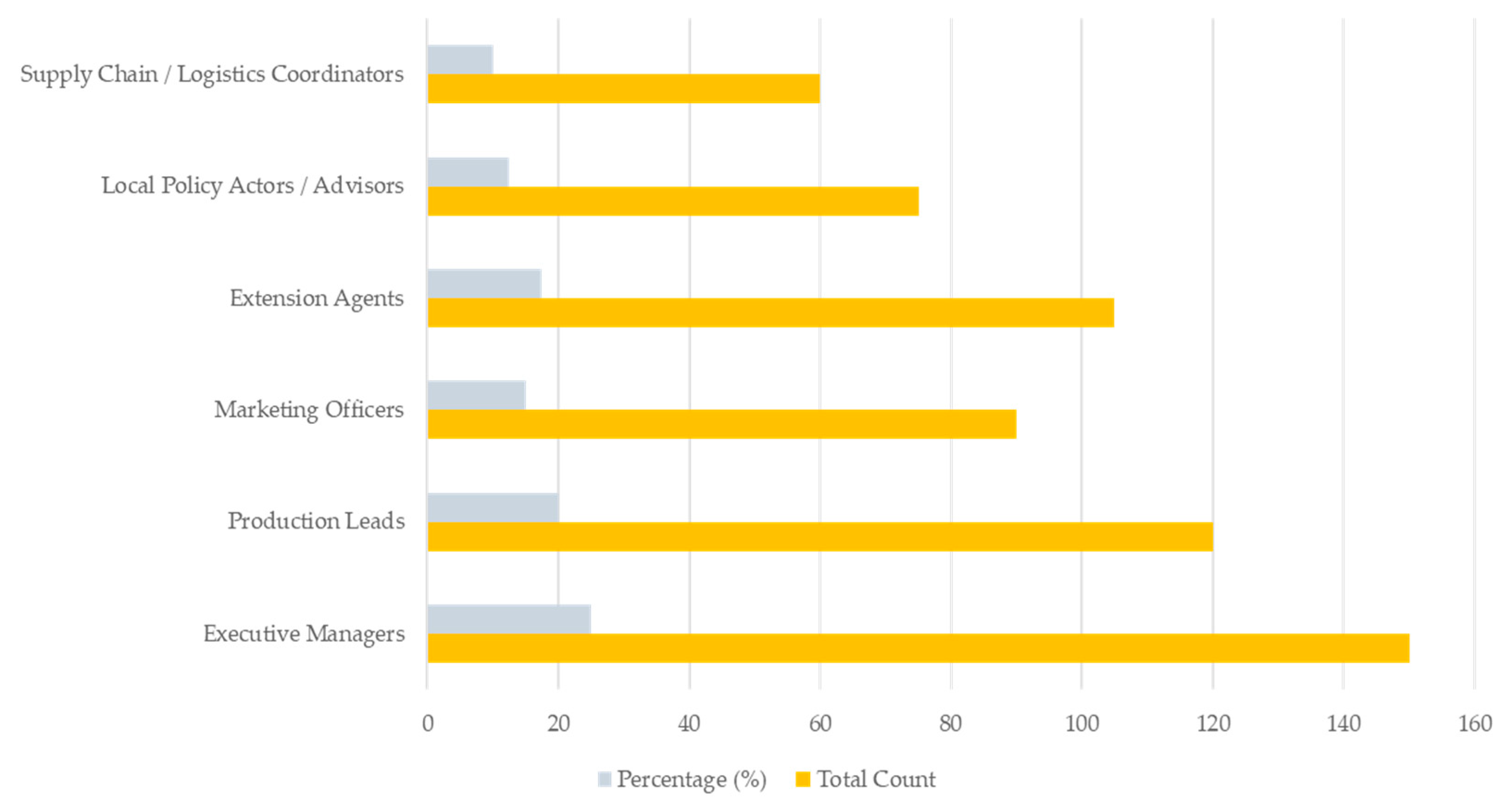

The study conducted semi-structured interviews with 600 informants embedded within 75 agribusiness enterprises across Albania, Bangladesh, and Ethiopia. Each enterprise contributed, on average, eight key informants, selected to reflect diverse roles and positionalities within the agribusiness value chain. These included executive managers (strategy and innovation oversight), production leads (technical and operational implementation), marketing officers (market sensing and consumer feedback), and external collaborators such as extension agents, policy advisors, and value chain facilitators. Survey instruments were pilot-tested on 9 firms (3 per country) to assess clarity, construct validity, and cross-cultural translatability. Feedback from pilot participants informed revisions to scale language, item order, and contextual relevance. The overall survey response rate was 93%, with minimal item non-response (<5%)

Figure 3 summarizes the distribution of interview respondents by role across the 75 agribusiness enterprises. Executive managers accounted for 25% of the sample, followed by production leads (20%), marketing officers (16.7%), and extension agents (18.3%). The inclusion of local policy actors, advisors, and logistics coordinators ensured that perspectives on both institutional engagement and operational adaptation were well represented. This diversity of roles aligns with the evolutionary economics framework by capturing firm-internal routines as well as external institutional linkages. This diverse respondent pool ensured that data captured both internal organizational routines and external institutional interactions, aligning with the theoretical framework of evolutionary economics, which emphasizes the interdependence of firm behavior and institutional environments [

8,

39].

The semi-structured interview method was selected for its capacity to balance comparability with exploratory depth. Unlike structured surveys, semi-structured formats allow informants to articulate experiences and interpretations in their own terms, which is essential when studying institutional embeddedness, path dependency, and adaptive learning, all central constructs in the evolutionary economics perspective. Moreover, semi-structured interviews are particularly effective in comparative fieldwork involving cross-national institutional diversity, as they accommodate contextual nuance while maintaining thematic coherence [

72,

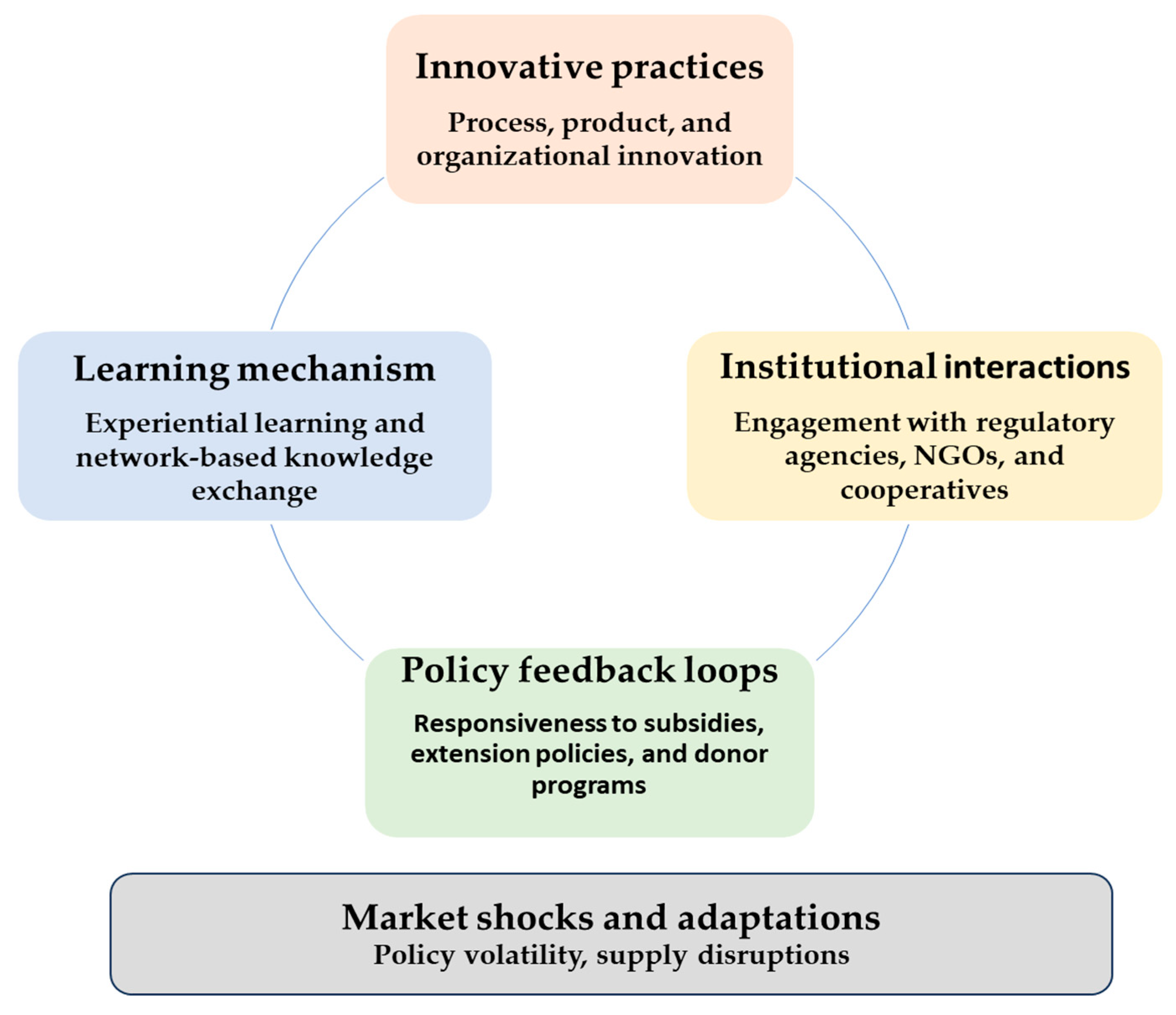

73]. The interview guide included, as shown in

Figure 4, both core and country-specific questions, organized under five major themes of innovation practices, institutional interactions, policy feedback loops, market shocks and adaptation, and learning mechanisms.

All interviews were conducted in local languages by trained data collectors, recorded with informed consent, and subsequently transcribed verbatim. Translations into English were carried out by bilingual field experts to preserve terminological and cultural specificity. To ensure methodological rigor and analytical consistency, the transcripts were imported into NVivo 14, a qualitative data analysis software designed to support coding and thematic exploration [

74]. To mitigate potential translation bias and maintain conceptual equivalence, a two-step translation protocol was applied. This involved forward translation by bilingual data collectors. Discrepancies were resolved through the review process. This approach ensured both linguistic fidelity and cultural resonance in capturing context-specific meanings.

The coding process followed a hybrid approach, combining both deductive and inductive strategies. Deductive codes were derived from core theoretical constructs, such as institutional routines, feedback mechanisms, and co-evolutionary dynamics, while inductive codes emerged through grounded reading of the transcripts. To ensure coding validity and reliability, a sub-sample of 20% of the dataset was dual-coded. The inter-coder agreement reached a Cohen’s kappa coefficient of 0.84, indicating a high level of reliability [

75]. Discrepancies were resolved through iterative discussion and adjustments to the codebook.

2.7. Quantitative Methods and Econometric Modeling

To quantitatively assess the institutional and contextual drivers of agribusiness innovation across Albania, Bangladesh, and Ethiopia, this study applies a stepwise econometric strategy grounded in multilevel linear modeling. The hierarchical structure of the data, where firms are nested within distinct institutional contexts, requires an estimation approach that accounts for both firm-level heterogeneity and context-level variance. Therefore, a hierarchical linear model (HLM), also known as a linear mixed-effects model, is employed. This approach is widely supported in innovation systems research, where firm behavior is shaped not only by internal capabilities but also by the broader institutional and ecological systems in which firms operate [

76,

77].

The dependent variable, innovation performance, is operationalized as a composite index created from four normalized indicators: (1) introduction of new products, (2) process innovation, (3) share of revenue from innovation, and (4) adoption of eco-innovation. These components were derived from semi-structured interview responses and standardized using z-scores. The index is constructed as:

where

represents the standardized value of indicator

k for firm

i, and

n is the total number of innovation indicators (here, 4). This approach, rooted in composite indexing and optionally reinforced by Principal Component Analysis (PCA), is widely used in empirical innovation research [

78]. In the next step, the model begins with an Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) regression to establish a baseline understanding of how structural characteristics influence innovation. This provides insight into the extent to which organizational features explain innovation performance in isolation.

In this model, SIZEi is the natural logarithm of the number of employees, AGEi represents the firm’s age in years, and SECTORi is a set of categorical variables for the firm’s sub-sector (e.g., dairy, horticulture). The error term ε

i captures firm-specific unobserved effects. While this model offers insight into the contribution of structural factors, it does not account for the institutional dynamics that more fully shape innovation behavior. Recognizing these limitations, the subsequent model incorporates institutional and policy dimensions, in line with evolutionary economics, which emphasizes routines, feedback loops, and co-evolution between firms and their environments [

8,

9].

To deepen the analysis, the model expands to include variables that capture firms’ institutional embeddedness and policy context. While the data structure permits more advanced causal modeling, such as Structural Equation Modeling (SEM), the study opted for hierarchical linear models (HLM) due to their interpretability, suitability for smaller sample sizes, and ability to accommodate nested structures. Given the exploratory nature of the institutional constructs, HLM provided the best balance between parsimony and explanatory power. These constructs, derived from semi-structured interviews and coded survey responses, are integrated as follows:

In this model, INST

i represents an index of institutional embeddedness (e.g., linkages with extension services, cooperatives, and donor agencies), and POL

i captures perceived clarity and coherence of national innovation policy. These variables were constructed from survey items coded on Likert scales and derived from themes identified in the qualitative phase. To ensure alignment between theoretical constructs and empirical measurement, qualitative themes such as “institutional routines” and “adaptive learning” were translated into survey items through a collaborative codebook development process. Variables were mapped using a construct validation matrix that matched interview codes to Likert-scale survey indicators (e.g., repeated engagement with extension agents as a proxy for institutional routines). This ensured theoretical consistency across methodological stages. These variables reflect the adaptive learning capacity of firms, which is central to evolutionary and systems innovation theory [

79,

80]. To test for contextual variation, interaction terms (e.g., INSTi × ETHIOPIA) are used to evaluate whether institutional linkages have differentiated effects under centralized governance settings. While not all interactions were statistically significant, several showed patterns consistent with interview-based insights on state-led innovation systems.

Where FEEDi captures market responsiveness (e.g., feedback loops, relational contracting), and DIGIi is an index for digital technology adoption. Given the comparative nature of the study and the hypothesis that innovation is shaped by context-specific routines, interaction terms were tested between institutional variables (e.g., INST) and country dummies. For instance, the interaction INST × ETHIOPIA examined whether embeddedness with state actors had stronger effects under centralized governance. Though not all interactions were statistically significant, results revealed meaningful country-specific variations that aligned with qualitative themes.

The full multilevel model was introduced to analyze firm-level innovation while accounting for the broader national environments in which firms operate. By incorporating country-level random effects, it captures unobserved heterogeneity across countries, such as legal, economic, and institutional differences, that influence innovation outcomes. This approach corrects for the nested data structure, improves the accuracy of estimated effects, and separates firm-specific drivers from systemic country-level influences, offering a more realistic and generalizable understanding of what shapes innovation across diverse contexts.

Where:

i indexes firms and j indexes countries,

includes all eight firm-level predictors described above,

is the random intercept for country-level heterogeneity,

is the firm-level error term

All models were estimated in SPSS v28 and validated using R’s lme4 package. Robust standard errors and multicollinearity diagnostics (VIFs) confirmed estimation validity. The intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) confirmed the presence of significant country-level variance in innovation performance, validating the multilevel structure. This multilevel approach not only accounts for unobserved heterogeneity but also operationalizes one of the central propositions of evolutionary economics—that innovation is embedded in multi-scalar systems of selection and feedback. The inclusion of environmental constraints further enhances the model’s contextual fidelity, ensuring relevance for LMICs navigating climate and infrastructure shocks, an essential consideration in comparative innovation systems research [

86,

87]. While linear mixed models were selected for their interpretability, future work could consider structural equation modeling to test latent interactions between institutional factors and innovation pathways. All composite indices (e.g., INNOV, INST, POL, FEED) were assessed for internal consistency using Cronbach’s alpha. All constructs exceeded the threshold of 0.70 (e.g., α = 0.81 for INNOV, α = 0.78 for POL), indicating reliable multi-item scales

Table 2.

Summary of key constructs and operationalization.

Table 2.

Summary of key constructs and operationalization.

| Variable |

Theoretical construct |

Source |

Measurement type |

Items/indicators |

| INNOV |

Innovation performance |

Semi-structured interviews (quantified) |

Composite index (standardized z-scores) |

Product innovation, process innovation, eco-innovation, % revenue from innovation |

| INST |

Institutional embeddedness |

Semi-structured interviews, coded to an ordinal scale |

Composite index (Likert-scale coding) |

Engagement with extension services, cooperatives, NGOs/donor programs |

| POL |

Policy clarity and coherence |

Semi-structured interviews, coded to an ordinal scale |

Composite index (Likert-scale coding) |

Perceived policy consistency, responsiveness, and transparency |

| FEED |

Market feedback loops |

Semi-structured interviews, coded to binary and ordinal values |

Index (theme-coded variables) |

Use of customer feedback, relational contracting, and supply chain responsiveness |

| DIGI |

Digitalization of operations |

Semi-structured interviews, coded to an ordinal scale |

Index (theme-coded variables) |

ICT use, platform integration, digital marketing, and digital traceability |

2.8. Limitations

Several limitations merit consideration. The purposive selection of Albania, Bangladesh, and Ethiopia, while justified through theoretical replication, limits the generalizability of findings to broader agrarian contexts. Maximum variation sampling enhanced intra-country diversity, yet external validity beyond the selected LMICs may be constrained. Additionally, the cross-sectional nature of the study captures only a snapshot in time, limiting the ability to observe institutional evolution or firm-level learning trajectories. To address this, future research could employ longitudinal designs or panel data to trace adaptive patterns and institutional change over time.

Furthermore, the transformation of qualitative data from structured interviews and focus group discussions into quantitative indices, though supported by high inter-coder reliability (κ = 0.84), may introduce coding subjectivity and interpretive loss. Triangulation and hybrid coding strategies were employed to mitigate this, yet some construct nuance may still be oversimplified in index form. Response bias also poses a risk, particularly among executive informants who may overstate innovation activity; this was partially addressed by including diverse roles and triangulating perspectives through FGDs. While hierarchical modeling with random intercepts effectively accounts for country-level heterogeneity, it may underrepresent structural differences in national policy frameworks. Fixed-effects modeling or country-specific sub-analyses could enhance future investigations. Finally, the study tried to use a rigorous back-translation protocol, even though this might have led to cultural and linguistic subtleties that have not been fully captured during data translation. This limitation shows the importance of localized interpretation and iterative validation in cross-national research.

3. Results and Discussions

3.1. Cross-National Patterns of Innovation Performance

Innovation outcomes in LMICs are not the result of firm-level effort alone, but of embedded interactions between enterprises and their surrounding institutional, technological, and policy environments. NIS theory emphasizes that it is not just the presence of actors, such as firms, regulators, extension services, and donors, but the quality of interactions and coherence among subsystems that determine innovation performance [

54,

81]. For example, innovation strategies must critically assess the underlying assumptions they rest upon, particularly those tied to scarcity and efficiency, as highlighted by Scoones et al. [

82].

To explore these dynamics empirically, this study applies a multilevel linear model that accounts for both firm-level variation and country-level contextual effects. The model is estimated using data from 75 agribusiness firms across three countries—Albania, Bangladesh, and Ethiopia—and includes both standardized composite indicators at the system level and coded variables from firm-level surveys and interviews.

Table 3 presents normalized scores for four structural pillars of each country’s innovation system: institutional embeddedness, policy clarity, digitalization, and market feedback responsiveness. The scores are aggregated from survey-coded data and secondary institutional benchmarks, forming an empirical profile of each NIS’s capacity to support innovation.

Bangladesh shows the most balanced system performance, with relatively high scores across all dimensions. The country’s strong digital infrastructure (0.76) and coordinated institutional platforms (0.72) are matched with relatively high market feedback responsiveness (0.64), producing a composite innovation score of 0.69. These results confirm previous research [

83] that emphasizes the importance of aligning digital readiness with governance and learning systems in LMICs. Ethiopia, while scoring highest in institutional embeddedness (0.81), lags significantly in digitalization (0.33) and feedback mechanisms (0.35), which constrains the adaptive potential of its otherwise well-structured public institutions. Albania’s low scores across all dimensions reflect a fragmented system where institutional routines, policy coordination, and market responsiveness are underdeveloped. These findings are consistent with Radosevic’s [

84] critique of post-socialist innovation systems as institutionally thin, having formal structures, but weak or misaligned functional linkages.

The macro-level patterns are further explored through a multilevel regression model in which firm-level innovation performance (INNOV) is modeled as a function of structural features (size, age, export status), systemic enablers (institutional support, policy clarity, digital adoption, market feedback), and environmental constraints. Bangladesh is used as the reference country, allowing for interaction terms to isolate effects specific to Albania and Ethiopia.

Table 4.

Multilevel linear regression results – predictors of firm-level innovation.

Table 4.

Multilevel linear regression results – predictors of firm-level innovation.

| Predictor Variable |

Coefficient (β) |

Standard Error |

p-value |

Interpretation |

| Digital tool adoption (DIGI) |

0.43 |

0.08 |

0.001 |

Strong predictor in Bangladesh |

| Policy clarity (POL) |

0.27 |

0.09 |

0.015 |

Moderate positive effect in Bangladesh |

| Institutional embeddedness (INST) |

0.18 |

0.10 |

0.073 |

Marginal significance |

| Market feedback access (FEED) |

0.22 |

0.07 |

0.006 |

Strong effect across contexts |

| Firm size (log employees) |

0.12 |

0.05 |

0.045 |

Larger firms more likely to innovate |

| Firm age |

-0.04 |

0.04 |

0.320 |

No significant effect |

| Export status |

0.31 |

0.06 |

0.002 |

Exporters show higher innovation |

| Climate constraint index |

-0.21 |

0.08 |

0.011 |

Climate risks reduce innovation |

| INST × Ethiopia |

0.32 |

0.12 |

0.014 |

Institutional effects stronger in Ethiopia |

| POL × Albania |

-0.24 |

0.11 |

0.037 |

Policy clarity less effective in Albania |

Overall, the study shows that digital adoption emerged as the most robust predictor of innovation (β = 0.43, p < 0.001) in Bangladesh, reflecting the central role of mobile platforms in enabling feedback and real-time learning. Institutional embeddedness was more influential in Ethiopia (interaction term β = 0.32, p = 0.014), but its impact was moderated by weak digital infrastructure and low market responsiveness. In Albania, policy clarity negatively interacted with innovation (β = –0.24, p = 0.037), suggesting that regulatory instability undermines firm adaptation. These results support the view that innovation is system-dependent, shaped by the interaction, not mere presence, of institutions, feedback channels, and firm behavior.

The finding of digitalization as the strongest and most consistent predictor of innovation performance in Bangladesh supports the idea that digital platforms enable not only logistical efficiency but also interactive learning and adaptation. Interviews confirm that digital tools are widely used to manage inventories, access real-time pricing, and interface with regulators. A poultry feed producer in Dhaka reported: “

Digital invoicing lets us track the whole chain—from suppliers to retailers—and the government accepts it for tax incentives.” Such practices suggest that Bangladesh is developing what Chaminade and Lundvall [

38] term “digitally enabled systems of learning,” where feedback loops are accelerated by ICT infrastructures. Policy clarity also emerges as a statistically significant determinant (β = 0.27, p = 0.015), indicating that firms in Bangladesh benefit from regulatory consistency and transparent state communication. Feedback mechanisms (β = 0.22, p = 0.006) further enhance innovation performance, highlighting the importance of relational contracting and customer input, features commonly cited in the interviews.

Ethiopia’s institutional embeddedness has a notably stronger impact than in Bangladesh, as captured by the significant interaction term (INST × Ethiopia, β = 0.32, p = 0.014). This suggests that state-coordinated extension services, donor linkages, and cooperative structures play a crucial role in innovation. However, weak digital infrastructure and limited feedback responsiveness severely constrain iterative learning. A seed producer in Oromia noted: “

We receive instructions, but there’s no channel to tell them what’s failing on the ground.” The asymmetry of communication illustrates the limitations of centralized systems that lack horizontal coordination, a challenge documented in Gebreeyesus and Mohnen [

85] and Cimoli, Dosi, and Stiglitz [

86]. Moreover, environmental constraints (β = –0.21, p = 0.011) appear to weigh heavily in Ethiopia, particularly given the infrastructure deficits and climate volatility reported during the interviews.

In Albania, the significant negative interaction for policy clarity (POL × Albania = –0.24, p = 0.037) suggests that regulatory inconsistency actively hinders innovation. Interviewees described a shifting landscape of subsidies, inspection regimes, and licensing requirements. A dairy processor in Tirana commented: “

Every year we adapt to a new rulebook. We invest in new machines, then find out they don’t qualify for the next round of grants.” This volatility erodes the very policy coherence that Edquist [

37] and Teece [

87] emphasize as crucial for sustaining innovation pathways. Institutional and digital indicators were not significant in Albania, reflecting the systemic fragmentation and lack of embedded support structures. This finding is consistent with Uvalić [

88] and Radosevic [

89], who identify persistent gaps between government, research, and private sectors in the Western Balkans.

These findings highlight that innovation in LMICs is fundamentally a system-dependent outcome. The impact of institutional routines, policy environments, and digital infrastructures is mediated by their integration and alignment. In Bangladesh, a relatively integrated system amplifies the effects of firm-level initiatives, producing stronger innovation outcomes. Ethiopia, while institutionally robust, suffers from low responsiveness and weak digital capability, limiting system adaptability. Albania represents a fragmented model where neither institutions nor policies are coherent enough to support systematic innovation learning. These insights reinforce the view that LMIC innovation systems should not be judged merely by the presence or absence of formal structures, but by how well those structures interact to enable knowledge flow, feedback, and adaptive experimentation [

88,

90].

3.2. Thematic Narratives from Interviews and FGD Data

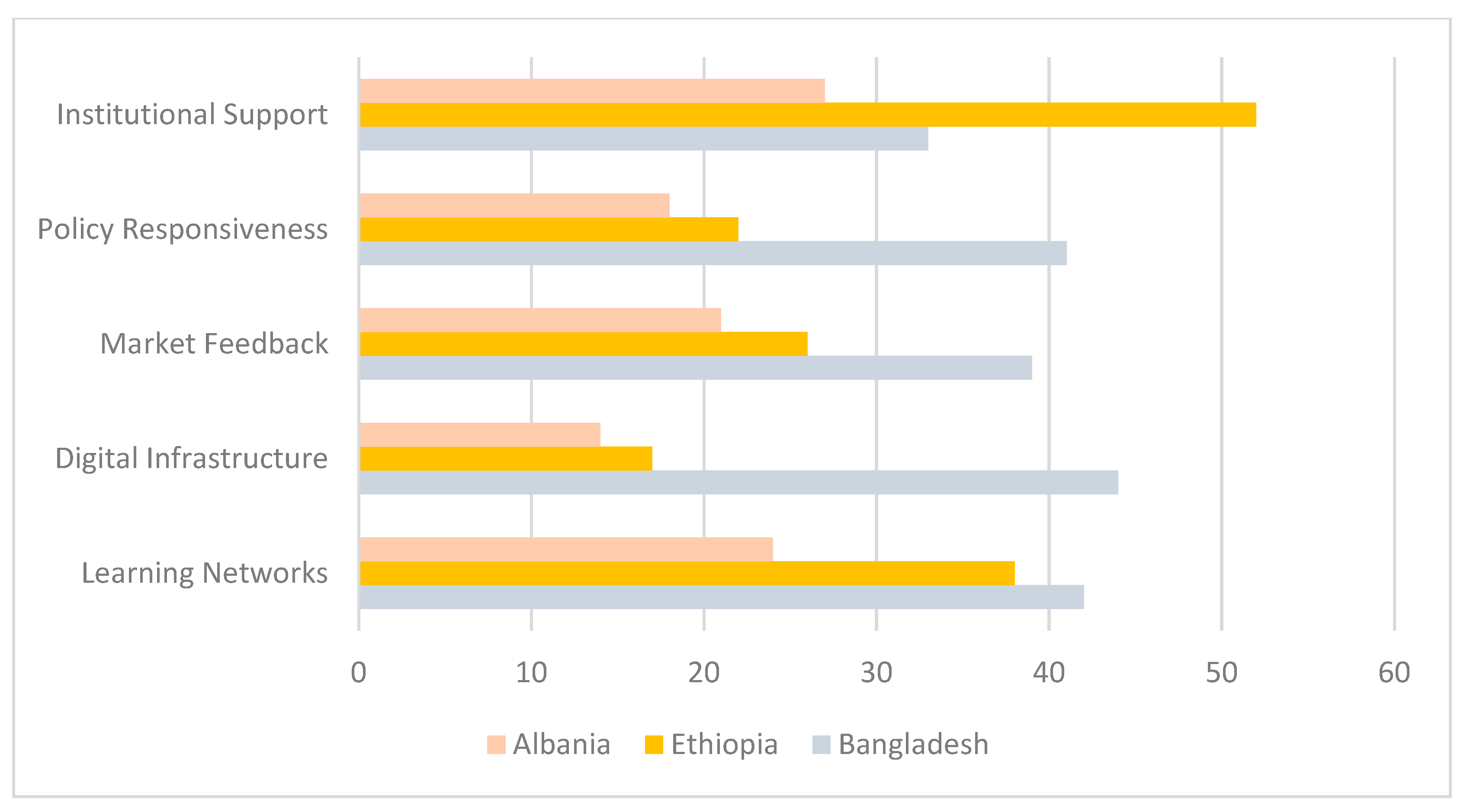

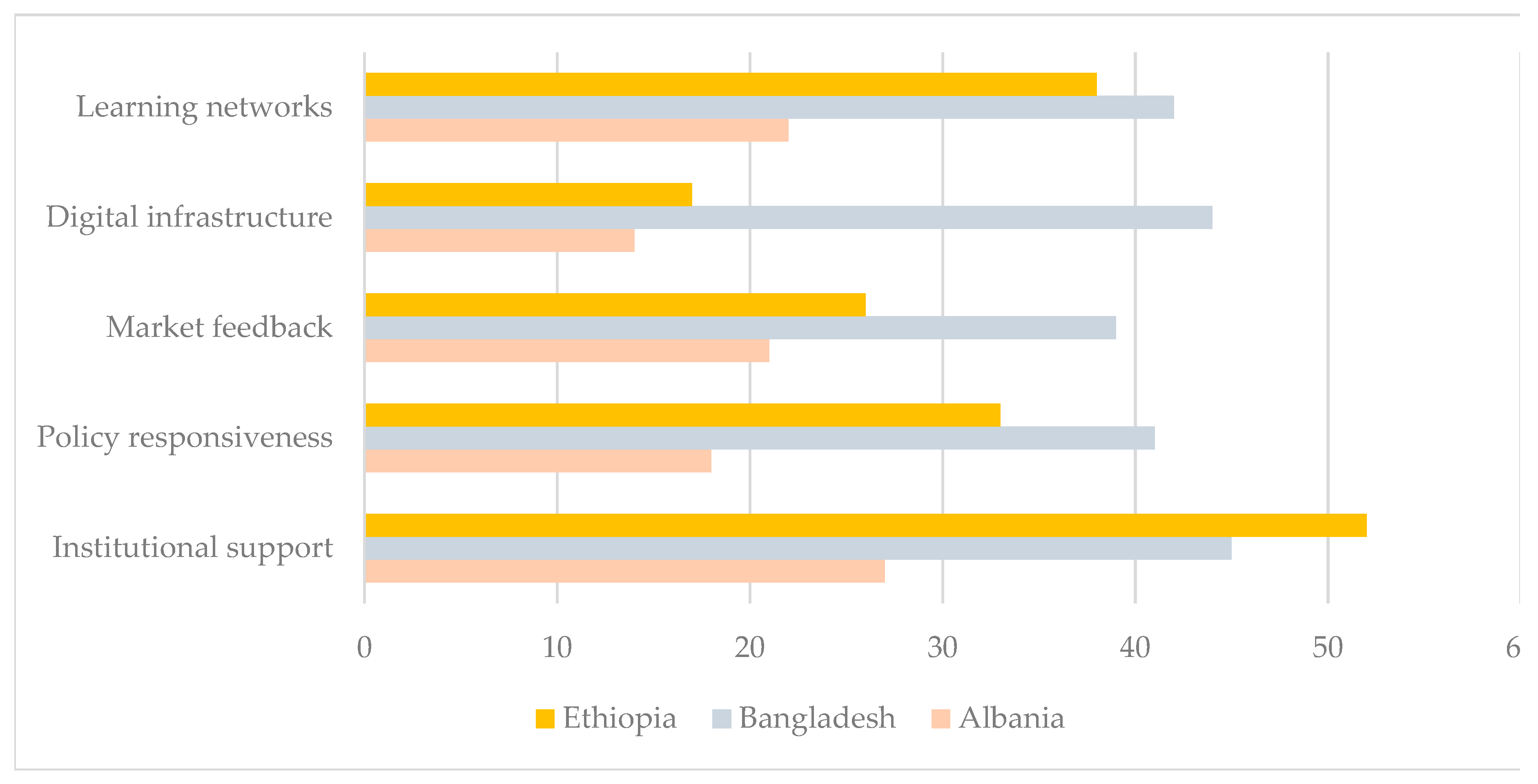

To enrich the quantitative and sectoral findings, qualitative evidence was gathered from over 600 semi-structured interviews and FGDs conducted across Albania, Bangladesh, and Ethiopia. Using grounded thematic coding, five recurrent themes were identified (as shown in

Figure 5): Institutional support, policy responsiveness, market feedback, digital infrastructure, and learning networks. These dimensions reflect how innovation capacity is shaped not only by material inputs but also by relational dynamics, governance routines, and actor interactions, echoing the systems-of-innovation theory [

36,

54].

Institutional support was the most cited theme across countries, but its form and effectiveness varied considerably. In Ethiopia, where mentions peaked at 52, the challenge lay not in the absence of institutions but in their rigidity. One extension officer explained, “

Our policies are well-designed but slow to adapt. We can’t try new things unless they’re officially approved.” This illustrates “institutional ossification,” which is further explained by Williams, Hailemariam, and Allard [

98] as clientelist and selective, and Abegaz [

99] as outdated governance structures and path-dependent bureaucracies. In other words, the ossification is a condition where hierarchical, top-down governance structures resist adaptation, stifling innovation and responsiveness. In contrast, Albania’s 27 mentions reflected institutional fragmentation and incoherence. A dairy processor in Fier shared, “

There’s no consistent message. One year it’s dairy, the next year it’s berries, and nobody helps you transition.” This finding supports regional studies in the Western Balkans that show Albania’s innovation system is a reflection of the broader challenges of post-socialist economies, marked by fragmented institutions, weak policy coordination, and low absorptive capacity [

88]. This also aligns with broader critiques of donor-dependent policy volatility in transitional economies [

91], where overlapping mandates and inconsistent support disrupt innovation continuity.

Policy responsiveness, defined as the speed and appropriateness of institutional reactions to emerging innovation needs, was most visible in Bangladesh (41 mentions). Firms appreciated iterative engagement and adaptive flexibility from both state and non-state actors. One horticulture SME from Khulna remarked, “

When customer demand shifts, we adjust planting. The union officers respond quickly—we’re not left guessing.” This aligns with Chaminade et al. [

92] and Crespi, Fernández-Arias, and Stein et al. [

93], who argue that responsive and co-evolving policy ecosystems significantly enhance innovation outputs in the contexts of developing economies. Albania’s lower score (18) again pointed to erratic or delayed governmental involvement, confirming findings by Ranga and Etzkowitz [

94], who found that institutional inertia, rooted in centralized governance, weakens trust and coordination among universities, industry, and government, hindering the shift to entrepreneurial innovation systems.

Market feedback was especially prominent in Bangladesh (39 mentions), where firms often relied on mobile technology to gather real-time demand signals, influencing production and product adjustments. As an aquaculture field supervisor in Chittagong noted, “

We receive price signals directly from market agents and adjust production fast. The tech helps close the loop.” These findings echo research by Diez and Kiese [

95] and Sumberg and Reece [

96], who emphasize that end-user interaction is crucial to triggering iterative learning and product tailoring. By contrast, in Ethiopia (26 mentions) and Albania (21), respondents described feedback as informal, delayed, or institutionally ignored. This disconnect reflects the concerns of Hall and Clark [

97], who suggest that without structured feedback channels, innovation systems risk becoming unidirectional, eroding learning and responsiveness.

Digital infrastructure was cited most often in Bangladesh (44), where the integration of ICTs into business practices, including WhatsApp groups, mobile-based extension apps, and remote diagnostics, has become foundational to innovation. One cooperative leader in Jessore explained, “

We use WhatsApp to coordinate supply with our buyer groups. No internet, no innovation for us.” This supports findings from Aker [

98] and de Janvry et al. [

99], both of whom argue that digital tools lower transaction costs, enhance transparency, and bridge information gaps, particularly in low-resource settings. In Albania (14) and Ethiopia (17), the digital divide remained a significant barrier, particularly in rural and peri-urban regions. Rashica [

100] and Donner [

101] provide evidence that such infrastructural gaps severely limit the scalability of innovation, especially where digital platforms are essential for market and knowledge connectivity.

Learning networks, both formal (cooperatives, platforms) and informal (peer-to-peer exchanges), were recognized as essential mechanisms for capability development and collective problem-solving. Bangladesh (42 mentions) and Ethiopia (38) showed strong engagement through WhatsApp groups, farmer cooperatives, and innovation platforms. A farmer in Bahir Dar described, “

We learn from each other at the cooperative. If someone tries a new fertilizer and it works, everyone hears about it.” Similarly, a startup owner in Mymensingh observed: “

Most of our new ideas come from others in our WhatsApp group, not the government.” These insights corroborate the findings of Waters-Bayer et al. [

102] and Kilelu et al. [

103], who demonstrate that horizontal knowledge transfer and community-based experimentation are powerful drivers of systemic innovation. Learning networks compensate for weak formal institutions and enhance the capacity of small firms to innovate in uncertain or resource-constrained environments.

Thematic evidence reveals that innovation ecosystems in the Global South are fundamentally shaped by actor interdependence, institutional adaptability, and real-time responsiveness. Bangladesh stands out for its distributed innovation architecture, characterized by strong digital integration, feedback loops, and peer-based learning. Ethiopia exhibits structural coherence but functional rigidity, whereas Albania struggles with coordination breakdowns and fragmented learning pathways. These narratives affirm what Freeman [

104] and Edquist [

36] have long emphasized: that the quality of interaction within the system, rather than the mere presence of institutions or funding, determines innovation performance. Moreover, the interplay of digital tools, feedback systems, and learning networks can substitute for traditional R&D infrastructure, offering viable pathways for inclusive innovation in under-resourced settings.

From the above findings, an important omission is the role of social differentiation in shaping innovation access. Future work should explore how gender, ethnicity, and class mediate firm interactions with policy and institutional systems, especially given women’s underrepresentation in agribusiness ownership and advisory structures. Disaggregated analysis may reveal unequal innovation capacity across demographic lines, highlighting the need for more inclusive innovation policies that account for these structural disparities. Addressing this gap is essential to ensure that innovation systems do not inadvertently reinforce existing social inequalities.

Figure 6.

Thematic innovation mentions by country (FGDs & interviews).

Figure 6.

Thematic innovation mentions by country (FGDs & interviews).

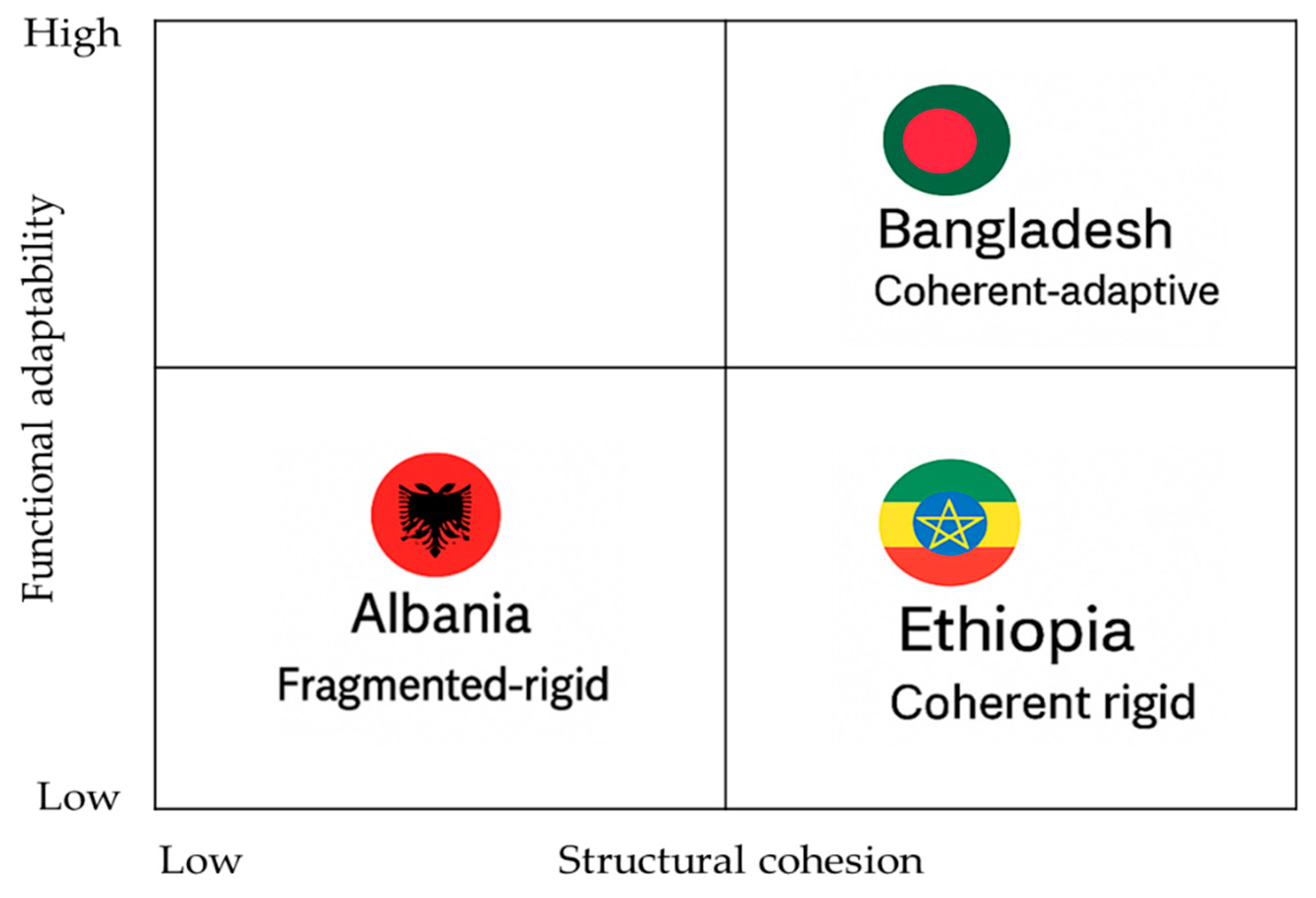

3.3. Cross-Case Typology of Innovation Systems: Balancing Coherence and Adaptability

A deeper synthesis of the NIS examined in this study reveals that cross-national differences are best understood not through absolute performance on individual pillars, but through the systemic alignment and responsiveness of institutional subsystems. For this reason, drawing from innovation systems literature, especially the frameworks developed by Castellacci and Natera [

105] and Teece [

87], the study proposes a typology structured along two key dimensions: structural coherence (the degree to which institutions, policies, and digital infrastructure are mutually aligned) and functional adaptability (the capacity of systems to learn, incorporate feedback, and enable distributed experimentation). This matrix-based approach allows for strategic differentiation of innovation trajectories and institutional bottlenecks across the three LMICs.

As shown in

Figure 7, from the cross-country analysis, Bangladesh functions as a coherent–adaptive system, where subsystems (e.g., regulatory, digital, and financial) interact fluidly to facilitate continuous learning and innovation. Ethiopia represents a coherent–rigid model: while its institutional architecture is well-developed and centrally managed, it lacks flexibility due to minimal digital integration and limited feedback uptake. In contrast, Albania shows a fragmented–rigid system marked by institutional disconnection, weak policy feedback mechanisms, and fragmented governance. These configurations underscore that innovation performance in LMICs is not a simple outcome of institutional presence but of how effectively these subsystems are aligned and integrated into an adaptive learning framework.

The coherent–adaptive system in Bangladesh is supported by robust infrastructure and responsive policymaking. Key indicators, such as digital infrastructure (0.76), policy clarity (0.68), and functional feedback (0.64), reflect a governance landscape that promotes participatory innovation and iterative learning. The presence of digital platforms and NGO–state partnerships allows for rapid feedback, peer-to-peer learning, and bottom-up adaptation. This distributed architecture of innovation aligns with theoretical insights on evolutionary governance and systems learning [

37,

106], illustrating how coherence and adaptability can coexist and reinforce each other.

In Ethiopia, the coherent–rigid typology is grounded in strong institutional embeddedness (0.81) and vertically integrated policymaking. However, limited digital infrastructure (0.33) and weak feedback responsiveness (0.35) result in a system that is structured but inflexible. The top-down nature of its agribusiness innovation system restricts local experimentation and cross-sector learning, thereby impeding the iterative refinement of policy tools [

46,

85]. Albania’s fragmented–rigid model, with low embeddedness (0.45) and poor feedback channels (0.42), suffers from disjointed donor interventions, a lack of institutional memory, and policy inconsistency. These challenges mirror those observed in post-socialist innovation systems, where structural discontinuities hinder systemic learning and long-term innovation capacity [

84,

88]. Together, these typologies demonstrate that innovation ecosystems must cultivate both structural coherence and adaptive reflexivity to succeed in dynamic agrarian environments.

This typology not only advances comparative insight but also strengthens the interpretive power of the multilevel model results. For instance, the differential effect of policy clarity across countries (positive in Bangladesh, negative in Albania) is consistent with their typological positioning: policy coherence amplifies innovation only when embedded within adaptive structures. Moreover, Ethiopia’s significant interaction effect on institutional support reflects a system where central coordination substitutes, albeit inadequately, for distributed responsiveness. By situating these cases within a unified conceptual matrix, the typology clarifies how innovation outcomes in LMICs are system-dependent and interaction-driven, rather than linearly related to individual policy or institutional inputs. The implication of this finding is that future policy design must thus prioritize not just capacity building within discrete pillars but the strengthening of cross-cutting interfaces that allow systems to adapt, learn, and respond in real time.

3.4. Institutional Synergies and Bottlenecks

The evolution of agribusiness innovation in developing economies cannot be understood by examining individual institutions in isolation. Instead, as the Systems of Innovation (SI) framework suggests, innovation emerges from interactions among subsystems: public R&D, regulatory bodies, digital infrastructure, extension services, and market feedback mechanisms [

36,

107,

108].

In Bangladesh, the data reveal functional synergies between digital infrastructure and market-regulatory feedback. Platforms like Digital Krishi Market, mobile banking (e.g., bKash), and real-time price apps are not only expanding access but are feeding into policy formulation processes, thereby fostering an iterative learning loop [

109,

110]. These mechanisms are central to what Klerkx et al. describe as innovation intermediaries—entities that span institutional boundaries to facilitate knowledge flow and adaptive regulation [

49]. Empirical studies confirm that these tools increase market transparency, reduce transaction costs, and empower smallholders to signal demand, catalyzing bottom-up feedback into regulatory processes [

111,

112]. Moreover, digital solutions have been integrated into public extension services, allowing field officers to update crop advisory databases and relay disease or climate alerts in near-real time. This reflects a learning-oriented governance model, consistent with evolutionary theory’s emphasis on feedback loops and selective retention [

38,

71]. However, persistent challenges in inter-agency coordination and gaps in boundary organizations limit the potential for deeper system-wide integration [

113]. Digital platforms not only serve as tools but act as ‘institutional brokers’ that span public-private divides and enable interactive learning, as conceptualized by Howells [

114,133] and Klerkx, van Mierlo, and Leeuwis [

49]. Their emergence in Bangladesh suggests a nascent but powerful model of digitally mediated innovation governance that merits deeper theoretical and empirical exploration

Ethiopia offers a contrasting picture: well-resourced but disconnected subsystems. The country has heavily invested in public R&D (EIAR) and national extension services, which are operationally coordinated through the Agricultural Transformation Agency (ATA). However, these structures remain hierarchically managed, with minimal engagement with private agribusinesses or real-time market signals [

64,

115]. Recent evaluations show that policy design still operates on ex-ante planning models, rather than incorporating feedback from implementation [

116]. Importantly, the digital ecosystem in Ethiopia is underdeveloped. Mobile penetration remains low in rural areas, and agri-tech initiatives are often donor-driven and pilot-bound. The absence of real-time data feedback limits the system's ability to engage in adaptive regulation or to recalibrate based on emergent outcomes, a core tenet of evolutionary economics. As Chaminade and Edquist argue, systems that lack interfaces among subsystems tend to suffer from “institutional thickness without coherence” [

117]. This is a good description of Ethiopia’s innovation landscape.

Albania’s case is defined less by a lack of investment and more by institutional fragmentation. Donor-funded R&D projects, policy support programs, and business incubators operate in parallel with limited coordination, resulting in low institutional embedding. Studies show that agribusiness SMEs rarely interact with public research or policy agencies, and knowledge exchange is episodic, often limited to the life cycle of donor interventions [

17,

118]. Digital tools and market information systems in Albania remain marginal, and where they exist (e.g., EU-supported platforms), they are not institutionalized within national innovation strategies. Albania also lacks boundary-spanning entities, such as sectoral innovation platforms, inter-ministerial task forces, or hybrid public-private R&D labs [

19]. This absence of coordinating infrastructure severely constrains learning-by-interaction processes [

54]. Consequently, Albania is an example of a system in which variation occurs, but selection and retention mechanisms are weak—innovations rarely scale, diffuse, or institutionalize.

This comparative analysis shows a crucial insight: the coherence of subsystem interactions, not subsystem strength alone, drives systemic innovation performance. Bangladesh’s emergent alignment between digital tools, market actors, and policy feedback offers a model of bottom-up adaptive capacity. Ethiopia, while institutionally dense, struggles due to a lack of horizontal connectivity and dynamic feedback. Albania, with fragmented subsystems and project-based logic, demonstrates low retention and institutional learning.

These findings offer three key contributions to agrarian innovation studies:

Extending SI theory to agribusiness contexts: This study operationalizes the SI framework in the agriculture and food sectors, areas historically underrepresented in SI literature [

24,

108]. It shows how the interplay of digital tools, regulation, and extension services uniquely shapes innovation dynamics in agrarian systems.

Highlighting interface institutions as catalysts: Consistent with Howells [

114], this research demonstrates the crucial role of innovation intermediaries—entities that facilitate cross-institutional learning and coordination. Their absence in Albania and partial emergence in Bangladesh offer critical insights into why innovation systems stall or scale.

Contributing empirical depth to evolutionary economics: By linking empirical subsystem mapping with theoretical constructs like variation-selection-retention and institutional co-evolution, this study enriches the evolutionary economics framework with actionable evidence from three distinct contexts.

3.5. Policy and Institutional Learning: Toward Adaptive Governance in LMIC Innovation Systems

In complex, uncertain, and resource-constrained settings such as those in LMICs, innovation systems must be governed not by static rules but through adaptive governance—a mode of policymaking grounded in reflexivity, iterative feedback, and collaborative problem-solving [

119,

120]. Adaptive governance transcends first-order regulatory compliance and embraces second-order learning, where institutional goals and instruments are reconsidered in light of emerging challenges and stakeholder feedback [

121]. This approach is especially critical in agribusiness, where innovation must respond dynamically to volatile markets, climatic shocks, and evolving value chains.

The study’s cross-country findings illustrate varying degrees of policy learning and adaptive governance across Bangladesh, Ethiopia, and Albania. Each represents a distinct model of institutional responsiveness and learning capability, offering key insights for how LMICs can move beyond static capacity-building toward dynamic institutional evolution.

The data from Bangladesh indicate a relatively advanced form of adaptive governance, consistent with second-order learning. Feedback mechanisms embedded in digital platforms and NGO-public collaborations facilitate continuous recalibration of agricultural policies. For example, changes in extension advice, subsidy disbursement, and seed certification procedures were found to be informed by usage data and field-level digital feedback [

109,

110]. This mode of policymaking aligns with “experimentalist governance” models, where policy objectives and methods are jointly developed, monitored, and revised through stakeholder engagement [

119]. Moreover, hybrid governance structures, such as partnerships between government agencies and NGOs (e.g., BRAC, iDE), serve as institutional bridges that translate localized learning into system-wide reforms. These structures not only implement policy but also reshape it—a hallmark of double-loop learning [

122]. While not without coordination challenges, Bangladesh offers an instructive example of how LMICs can institutionalize policy reflexivity through digital infrastructure and civil society engagement [128,134].

Ethiopia’s innovation system is characterized by first-order governance—a model where policy objectives are pre-set, and institutions function primarily as implementers, not as learning entities. Agricultural strategies like the Agricultural Growth Program (AGP) and the Agro-Industrial Park Initiative rely heavily on central planning and vertical accountability [

49,

98]. Despite strong implementation capacity and donor alignment, feedback loops remain weak. Stakeholder consultations are often episodic and extractive, rather than iterative and adaptive. This governance style reflects a technocratic model of policymaking, where adaptation occurs through adjustment of instruments, not reconsideration of underlying goals or structures [

120]. Field interviews and document reviews show minimal uptake of feedback from agribusiness firms or farmer organizations into national-level planning. Consequently, Ethiopia’s governance model lacks the dynamic capabilities required for navigating uncertainty or co-evolving with market and environmental shocks [

123].

Albania represents a case of disjointed institutional learning, where fragmented governance structures and weak institutional memory inhibit cumulative knowledge building. Although numerous donor-led projects have introduced innovative agricultural practices and market systems, these initiatives have rarely been integrated into national policy frameworks [

17,

18]. Project evaluations often exist in isolation, and there are few mechanisms for lessons learned to be institutionalized in public R&D or extension systems. This pattern reflects what is referred to as “institutional amnesia”—a condition in which feedback is either lost or dismissed due to weak inter-agency coordination and the absence of long-term strategic planning [

124]. Albania’s innovation system suffers not from a lack of learning inputs, but from a lack of institutional continuity to absorb, adapt, and scale such inputs. This limits the emergence of policy layering, where new initiatives are embedded atop existing structures for iterative enhancement [

125].