1. Introduction

Integrated Agro-Industrial Parks (IAIPs) represent a transformative approach to agricultural development, with the potential to enhance productivity and competitiveness in the agribusiness sector of developing economies (Bowman & Chisoro, 2024; Urugo et al., 2024, Boru, et al., 2025),particularly in the African context. Across Africa, agriculture is largely characterized by smallholder farming, traditional practices, and a reliance on subsistence production (Ruppel, 2022).Despite these challenges, agriculture holds significant potential for economic growth and job creation, particularly when combined with industrial activities (Collier & Dercon, 2014; Palacios-Lopez et al., 2017).The continent's diverse agro-ecological conditions allow for the cultivation of a broad range of crops and livestock, offering a substantial foundation for agro-industrial processes that can add value and increase global competitiveness (World Bank, 2021).

In Ethiopia, agriculture is a cornerstone of the economy, employing approximately 65% of the labor force and contributing around 32% to the Gross Domestic Product (GDP) (NBE, 2023; ESS, 2021). The sector is primarily composed of smallholder farmers, many of whom face significant barriers to productivity, including limited access to technology, markets, and essential inputs, poor infrastructure, and vulnerability to climate change (Anbes, 2020). Recognizing the potential of agriculture as a driver of industrialization, the Ethiopian government has prioritized its integration with industrial frameworks as part of its broader development strategy. The establishment of IAIPs is seen as an effective mechanism to bridge the gap between agriculture and industry, driving innovation and sustainable economic growth.

The success of IAIPs in fostering agricultural-industrial integration depends largely on the governance structures, institutional frameworks, and the innovation ecosystems that surround them. These elements must enable effective multi-stakeholder coordination, involving smallholder farmers, agro-industrial firms, financial institutions, and research entities (Ghione et al., 2021). Such coordination is key to enhancing the innovation ecosystem, improving resource allocation, and facilitating access to technology (Belayneh & Zewdu, 2019). Through a focus on value chains, IAIPs are expected to improve the processing of agricultural products, reduce postharvest losses (PHL) (Urugo et al., 2024),and generate employment, thereby strengthening the economic linkages between agriculture and industry.

Furthermore, IAIPs are strategically designed to support Ethiopia’s broader objectives of achieving food security, boosting exports, and promoting sustainable agricultural practices (UNIDO, 2022). The integration of agriculture with agro-processing firms not only improves product quality and market access but also positions Ethiopia as a competitive player in the global market. By leveraging its agricultural strengths and linking them with industrial capabilities, IAIPs play a crucial role in transforming the agricultural sector and enhancing the country’s economic resilience (UNIDO, 2022).

Research by Ghione et al. (2021) and Sambo et al. (2021) suggests that robust governance structures within IAIPs are essential for optimizing resource allocation, facilitating access to finance, and promoting research and development. Leveraging these governance frameworks is critical for creating an environment that fosters sustainable agricultural practices and agro-industrial growth, enabling Ethiopia to effectively compete in global markets (UNIDO, 2020). The success of IAIPs in Ethiopia highlights the significance of integrated governance and institutional arrangements in driving transformative changes that enhance innovation ecosystems and foster competitive advantages in the global economy.

Despite the growing recognition of IAIPs as a key strategy for enhancing agricultural productivity and industrialization in Africa, particularly in Ethiopia, there remain several significant gaps in both the literature and practical implementation. Firstly, there is a lack of comprehensive tools to assess the effectiveness of IAIPs. As a relatively new concept in Ethiopia, policymakers remain uncertain about the strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats posed by IAIPs, particularly in terms of ensuring global competitiveness. Furthermore, this area has not attracted sufficient attention from the academic community.

Secondly, existing literature primarily addresses the economic aspects of IAIPs, such as productivity and market access (Anbes, 2020; Shabanov et al., 2021), with less emphasis on the institutional and governance dimensions crucial for their success. Effective governance structures are needed to facilitate coordination among various stakeholders, including government entities, private sector actors, and local communities. This study seeks to explore the roles and interactions of these stakeholders within the institutional and governance frameworks of IAIPs in Ethiopia. By examining stakeholder dynamics and institutional effectiveness, the research will provide valuable insights into how governance can enhance innovation ecosystems and support sustainable practices within IAIPs.

Additionally, there is a notable gap in understanding the long-term sustainability of IAIPs in relation to the institutional frameworks and innovation ecosystems that underpin them. This study aims to investigate the feedback loops between institutional frameworks, stakeholder coordination, innovation performance, and global competitiveness, highlighting how improvements in one area can influence others. Furthermore, a SWOT analysis will be employed to assess the strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats arising from the interactions of these variables within IAIPs in Ethiopia. By elucidating these connections and feedback mechanisms, this research aspires to enhance our understanding of how institutional structures, stakeholder coordination, and innovation systems can be leveraged to reinforce global competitiveness.

By addressing these gaps, this study seeks to contribute to the theoretical frameworks surrounding Integrated Agro-Industrial Parks (IAIPs) and provide valuable insights for policymakers and practitioners. These insights will assist in optimizing IAIPs, thereby promoting economic growth and fostering sustainable development both in Ethiopia and beyond. The structure of this paper is as follows:

Section 2 presents a review of the literature and conceptual frameworks,

Section 3 details the research methodology,

Section 4 discusses the findings and their implications,

Section 5 concludes with policy recommendations, and the final section covers ethical considerations and acknowledges the study's limitations.

2. Literature Reviews and Conceptual Frame

2.1. Literature Reviews

The conceptual framework for IAIPs is grounded in several theories that highlight the importance of governance (Larçon & Vadcar, 2021), multi-stakeholder coordination, and innovation ecosystems (Yigezu Wendimu, 2021). Institutional Theory posits that organizations operate within a framework of rules and norms that shape their behavior and interactions (Dong et al., 2021; Janssen & Nonnenmann, 2017). This theory helps explain how governance structures and institutional frameworks influence the effectiveness of IAIPs in facilitating stakeholder collaboration. Innovation System Theory further complements this framework, emphasizing the significance of networks and partnerships among various actors, including governments, businesses, and research institutions, in fostering technological advancements and improving productivity in agro-industrial contexts (Adamides, 2023; Asheim et al., 2011; Jenson et al., 2016). Additionally, the Sustainability Transition Theory underscores the need for eco-friendly practices and sustainable resource management within agro-industrial processes to ensure long-term viability and resilience against environmental challenges (Costa et al., 2023; Gaziulusoy & Öztekin, 2019; Horn et al., 2024). In the following paragraphs, we further elaborate on key theoretical approaches relevant to understanding IAIPs starting with Institutional theory.

Institutional theory serves as a foundational framework for understanding how formal and informal norms, rules, and practices shape organizational behavior. This theory posits that organizations, including those in IAIPs, operate within a context defined by regulatory, normative, and cognitive structures [

29] (Scott, 2001). In the context of IAIPs, the regulative pillar involves laws and regulations that govern activities, such as agricultural policies, trade agreements, and environmental laws. The normative pillar encompasses the values and expectations of stakeholders, including farmers, businesses, and government agencies. Lastly, the cognitive pillar relates to shared beliefs and understandings that influence how stakeholders perceive and engage with IAIPs. In the context of IAIPs, effective governance relies heavily on institutional arrangements that facilitate coordination and trust among stakeholders. For instance, research has indicated that well-defined roles and responsibilities, effective communication channels, and mutual accountability mechanisms are crucial for fostering coordination among various actors (Belayneh & Zewdu, 2019). Understanding these institutional dynamics can help identify best practices for enhancing the effectiveness of IAIPs in promoting agricultural productivity and competitiveness.

Innovation System Theory focuses on the interactions and networks among diverse actors involved in the innovation process (Adamides, 2023). It emphasizes the need for collaborative relationships between public and private entities, research institutions, and local communities to drive technological and organizational innovations (Lundvall, 1992). Within the framework of IAIPs, this theory highlights how innovation ecosystems can be nurtured to facilitate knowledge exchange and technology transfer. The role of innovation in IAIPs is critical, as it can enhance productivity, improve product quality, and foster competitiveness in local and global markets. Empirical evidence suggests that the success of IAIPs depends on the establishment of strong networks that enable information sharing and collaborative problem-solving (Sambo et al., 2021). Additionally, policy frameworks that support research and development, training programs for farmers, and access to financial resources are essential for creating a conducive environment for innovation in agro-industrial activities.

Governance Theory, on the other hand, addresses the processes, structures, and relationships involved in decision-making and resource allocation among stakeholders (Hassan et al., 2020). It extends beyond traditional hierarchical models of governance to embrace a more decentralized and participatory approach, acknowledging the role of multiple actors in shaping outcomes (Liu et al., 2022). In the context of IAIPs, effective governance is characterized by inclusiveness, transparency, and accountability. This theory underscores the importance of multi-stakeholder coordination in IAIPs, which involves not only governmental bodies but also private sector entities, non-governmental organizations, and local communities. The governance structures that facilitate stakeholder engagement, such as advisory boards or public-private partnerships, are essential for aligning the interests of diverse actors and ensuring that the benefits of IAIPs are equitably distributed (Morris et al., 2020). Moreover, Governance Theory emphasizes adaptive management practices that allow for continuous learning and responsiveness to changing conditions within agro-industrial contexts. This adaptive capacity is crucial for addressing the challenges posed by environmental degradation, market fluctuations, and evolving technology.

Sustainability Transition Theory explores how systems can transition towards sustainable practices and outcomes (Higgins & Richards, 2019; Pigford et al., 2018), emphasizing the need for integrating economic, social, and environmental dimensions in decision-making (Geels, 2011). In the context of IAIPs, this theory advocates for the adoption of sustainable agricultural practices that minimize environmental impacts while promoting economic growth and social equity. Research indicates that IAIPs can play a pivotal role in fostering sustainable practices by integrating value chain approaches that emphasize resource efficiency, waste reduction, and the use of renewable energy sources (Smit et al., 2020). The challenge lies in effectively aligning the goals of productivity and sustainability within the governance frameworks of IAIPs. The literature underscores the need for policies that encourage investments in eco-friendly technologies, promote sustainable land management practices, and enhance stakeholder capacity to implement sustainability initiatives.

Complex Adaptive Systems Theory provides a lens through which to view IAIPs as dynamic systems, characterized by interconnected components (Brown, 2006; Stroink, 2020). This theory hypothesizes that such systems evolve over time, adapting to environmental changes through the interactions of various actors (Simon, 1996). IAIPs can be seen as complex and adaptive systems where the interplay between agriculture, industry, and governance shapes the overall performance and resilience of the parks as well as its overall ecosystem. This theoretical perspective emphasizes the need for flexibility, innovation, and adaptive capacity within IAIPs. The interactions among stakeholders can lead to emergent behaviors that enhance or hinder the effectiveness of agro-industrial initiatives. Consequently, understanding the system dynamics and feedback loops within the park’s ecosystem can inform strategies for enhancing their resilience and responsiveness to external pressures, including market demands, environmental challenges, and technological advancements.

Empirical studies have increasingly focused on the role of governance and institutional frameworks in the establishment and management of IAIPs and their impact on agricultural productivity. For instance, a study by Belayneh and Zewdu (2019) highlighted how effective governance structures in Ethiopia's IAIPs promote coordination among stakeholders, which is essential for driving innovation and enhancing competitiveness in the agricultural sector. Furthermore, research by Sambo et al. (2021) examined the operational dynamics of IAIPs in various African countries, noting that effective multi-stakeholder coordination leads to improved resource allocation, technology dissemination, and knowledge sharing, ultimately benefiting local farming communities.

The literature also emphasizes the potential of IAIPs to foster sustainable practices. For example, a study by Smit et al. (2020) investigated the environmental management practices within IAIPs, finding that integration of eco-friendly technologies and sustainable resource management strategies is critical for minimizing the ecological footprint of agro-industrial activities. Additionally, empirical evidence from the United Nations Industrial Development Organization (UNIDO, 2020) demonstrates that IAIPs can significantly enhance the resilience of agro-food systems by promoting sustainable practices that align with global market demands.

Despite the growing body of research on IAIPs, several critical gaps remain. First, there is a need for more comprehensive studies on the specific governance structures and institutional frameworks that effectively support multi-stakeholder coordination within IAIPs, particularly in the unique socio-economic and political contexts of Ethiopia and other African nations. While many studies emphasize stakeholder coordination, fewer provide an in-depth analysis of how these frameworks can be optimized for better outcomes. Second, existing literature often overlooks the long-term sustainability implications of IAIPs. Although there is recognition of the need for sustainable practices, more research is required to assess the effectiveness of these practices in mitigating environmental risks and promoting resource efficiency within agro-industrial contexts. Lastly, there is a significant gap regarding the integration of technology and innovation within IAIPs. While some studies touch on the benefits of adopting technological advancements in agriculture, fewer provide a comprehensive examination of the barriers to technology adoption and how these can be overcome to enhance productivity and competitiveness in IAIPs.

2.2. Conceptual Framework

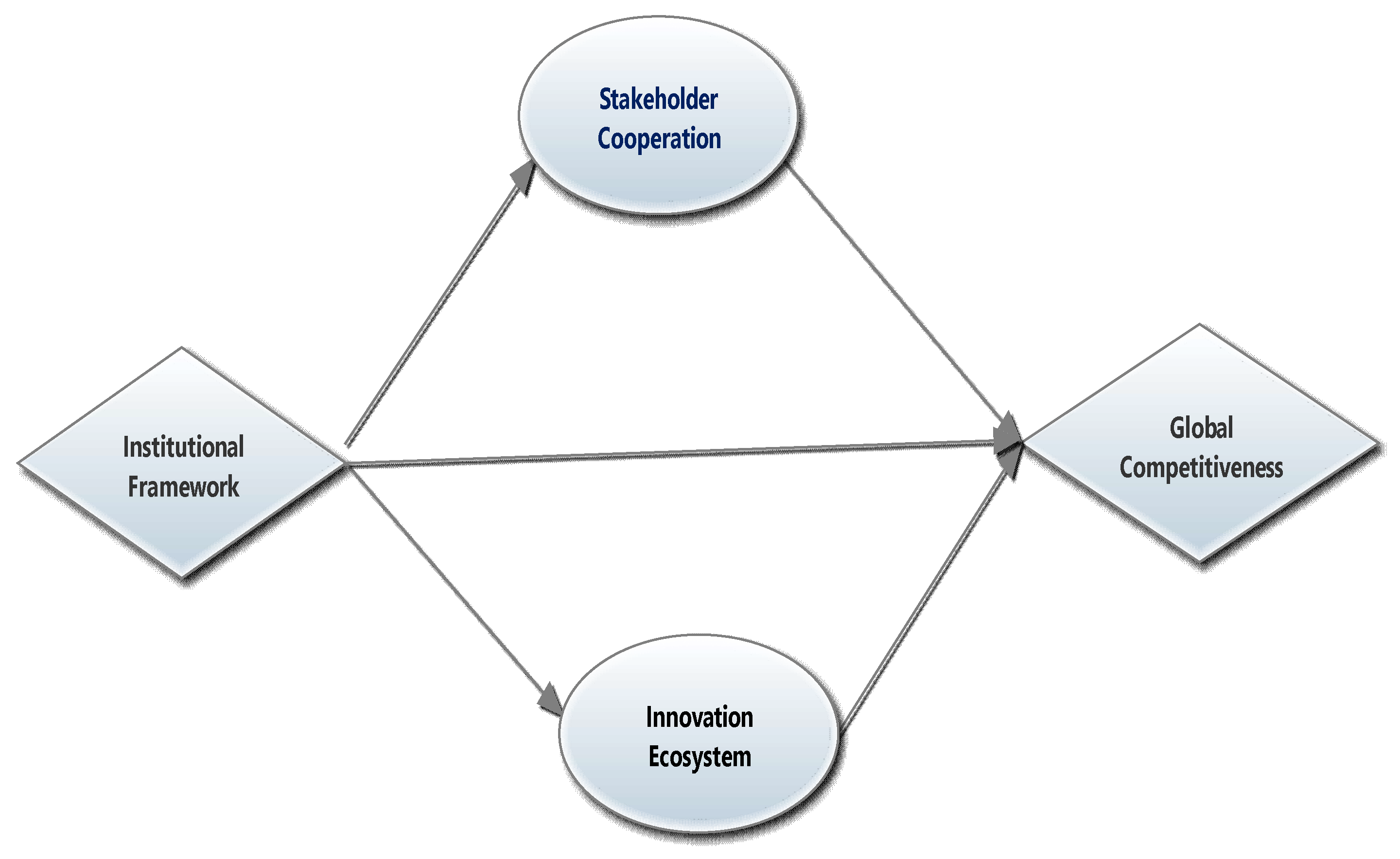

The institutional framework plays a critical role in shaping stakeholder coordination within IAIPs. Institutions—comprising formal rules, regulations, and informal norms—set the stage for interactions among various stakeholders, including government agencies, private sector, research institutions, and local communities (Aldersey-Williams et al., 2020; Barlagne et al., 2023; Ebrahimi et al., 2021). According to Romani et al. (2020), institutions provide the structure within which economic activities occur, influencing the behavior of stakeholders. Effective stakeholder coordination, facilitated by a robust institutional framework, fosters coordination and resource sharing, leading to enhanced collective approaches to innovation (Jordan et al., 2022). This synergy is vital in addressing challenges within the agro-industrial sectors, such as sustainability, food security, and technological advancements.

The relationship between stakeholder coordination and the innovation ecosystem is also pivotal in developing competitive advantages for any organization (Aldersey-Williams et al., 2020; Bowman & Chisoro, 2024). An innovation ecosystem, characterized by a network of interconnected organizations and individuals, thrives on the effective coordination of stakeholders who share knowledge, resources, and capabilities (Adner, 2006). When stakeholders work cohesively, they can better leverage their collective expertise, leading to the development of innovative agricultural technologies and practices. This coordination enhances the efficiency and effectiveness of production processes and positions the parks as hubs of innovation. By fostering a culture of coordination and creativity, the innovation ecosystem nurtured through strong stakeholder coordination contributes to the overall resilience and adaptability of the agri-food sector.

Ultimately, the interplay between institutional frameworks, stakeholder coordination, and innovation ecosystems significantly influences the global competitiveness. As outlined by Porter (1990), competitive advantage is derived from a complex interplay of factors including technological advancement, skilled workforce, and effective coordination among stakeholders. In agro-industrial parks, a supportive institutional environment in addition to facilitating the alignment of interests among diverse stakeholders it encourages innovation that meets global market demands (Helfat, 2011). Consequently, by enhancing the coordination among stakeholders and fostering a thriving innovation ecosystem, agro-industrial parks can improve their competitiveness on a global scale, driving economic growth and sustainability in the agri-food sector.

Figure 1.

Conceptual framework Source: Researchers own sketch.

Figure 1.

Conceptual framework Source: Researchers own sketch.

3. Research Methodology

3.1. Research Design

This study employs a mixed-methods approach, utilizing both qualitative and quantitative analyses to investigate the governance and institutional frameworks within IAIPs (Eisenhardt, 1989; Sanchez, 2013). Through thematic analysis and SWOT analysis, we aim to gain an in-depth understanding of the complex interactions among stakeholder coordination, the sectoral innovation system, and global competitiveness (Fiss & Zajac, 2004). In addition, we employ Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) to quantitatively assess the relationships between these variables (Henseler, Ringle, & Sinkovics, 2009). By integrating both qualitative and quantitative perspectives, this research aims to provide comprehensive insights into the role of governance in enhancing the competitiveness of IAIPs (Chin, 2010; Kock & Hadaya, 2018).

3.2. Data Collection

Data for this study was collected from two Industrial Agro-Industrial Parks (IAIPs), Bulbula and Yirgalem, involving a diverse group of stakeholders, including park managers, one-stop shop staff, private sector representatives, producers, researchers, and development partners. To ensure a comprehensive understanding of the governance dynamics at play in IAIPs operating in Ethiopia, a multi-method approach was employed for data collection (Bryman, 2016). This method integrates both qualitative and quantitative data collection techniques to offer richer insights and better triangulate findings (Denzin, 2017).

The first method involves conducting in-depth interviews with key informants, such as park managers, government officials, industry leaders, development partners, and academics. These semi-structured interviews focus on evaluating the institutional frameworks that support stakeholder coordination, innovation ecosystems, and global competitiveness (Gioia, Corley, & Hamilton, 2013). Semi-structured interviews are ideal for capturing the diversity of opinions and experiences of stakeholders while providing a consistent framework for comparison (Patton, 2002). An interview guide was developed with open-ended questions designed to promote discussion around major themes, including governance effectiveness, stakeholder engagement, and innovation barriers (Bauer & Gaskell, 2000). Each interview was audio-recorded, with participant consent, and subsequently transcribed for detailed analysis, allowing for the capture of nuanced insights (Creswell & Poth, 2017).

In addition to interviews, focus group discussions were organized to gather qualitative data from small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs), agro-industrial firms operating within the IAIPs, park administrators, government ministries, and development partners. Focus groups are valuable for examining group dynamics, exploring shared experiences, and generating diverse perspectives on complex issues like innovation challenges and multi-stakeholder coordination (Morgan, 1997). Each focus group consisted of 6-12 participants and was facilitated by a trained moderator, ensuring that all voices were heard, and discussions remained productive and on topic (Krueger & Casey, 2014). These sessions were also audio-recorded and transcribed, ensuring a comprehensive capture of perspectives to enrich the data set (Lindlof & Taylor, 2011).

Finally, a comprehensive document review was conducted, analyzing governance documents, IAIP operational frameworks, and policy-related materials on industrial park development and innovation diffusion. Document analysis allows researchers to access rich, secondary data sources that provide context and background on formal structures and policies (Bowen, 2009). The document analysis aimed to understand the vital context and background information regarding the formal structures, policies, and strategies guiding governance practices, innovation ecosystems, and global competitiveness within IAIPs (Patton, 2002). Relevant documents were systematically collected from governmental reports, industry associations, and the IAIPs themselves. A coding scheme was developed to categorize key information extracted from these documents, focusing on aspects such as governance structures, institutional effectiveness, and mechanisms supporting global competitiveness (Saldaña, 2015).

By using a combination of in-depth interviews, focus group discussions, and document analysis, this study leverages triangulation, enhancing the validity and credibility of the research findings (Flick, 2018). These methods provide a rich, multifaceted view of the governance and institutional frameworks within IAIPs, thereby offering comprehensive insights into the factors influencing their effectiveness in fostering innovation and competitiveness.

3.3. Data Analysis

The analysis of the collected data is performed using two principal methods: qualitative (thematic analysis and SWOT analysis) and inferential (PLS-SEM) analysis. Thematic analysis involves coding the interview and focus group transcripts to identify and analyze patterns and themes related to institutional capacity, governance effectiveness, and innovation ecosystems and their individual and cumulative effect on promoting global competitiveness in IAIP. Qualitative data analysis software, such as SPSS and Qualitative Data Analysis (QDA), are employed to assist in the coding process, enhancing the validity and rigor of the analysis by providing systematic categorization of themes that emerge from the data.

Complementing the thematic analysis, a SWOT analysis is conducted to evaluate the governance and institutional frameworks concerning their strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats. This analysis focuses on identifying the features of governance that support effective innovation, highlighting areas where shortcomings exist, and exploring external factors that could enhance innovation processes. Additionally, it outlines potential challenges and risks that may hinder successful coordination and innovation efforts within IAIPs. The findings from the thematic analysis and document review serves as the foundation for this SWOT analysis, offering a comprehensive view of the governance landscape and its impact on fostering an innovative ecosystem.

3.4. Econometric Model and Estimation Strategies

To model the interplay among governance, institutional frameworks, innovation ecosystem and multi-stakeholder coordination in shaping global competitiveness, we employ Structural Equation Modeling (SEM). This robust statistical technique is widely applicable and well-suited to our data, enabling us to capture the dynamics at play. SEM is extensively used for exploring complex relationships among both observed and latent variables (Fan et al., 1999; Jing et al., 2022; Kirby & Bollen, 2009; Williams et al., 2018). This methodology allows for the simultaneous testing of models with multiple dependent and independent variables, addressing complex relationships and paths within a unified framework (Jing et al., 2022; Kirby & Bollen, 2009; Rahmadi et al., 2019).

By integrating factor analysis, path analysis, and regression analysis, SEM facilitates a detailed examination of underlying constructs that may not be easily approached using direct methods (Saris et al., 1987). Moreover, it captures both direct and indirect effects among variables, providing valuable insights into the dynamics at play (Memon et al., 2021). This capacity makes SEM an ideal tool for hypothesis testing and model evaluation, offering a comprehensive understanding of how governance frameworks and institutional arrangements synergistically influence innovation ecosystems and contribute to global competitiveness.

In this study, we utilize Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) to effectively address potential challenges associated with small sample sizes. PLS-SEM is particularly advantageous in contexts where data constraints may limit the applicability of traditional SEM approaches, as it is specifically designed to handle smaller samples without compromising the robustness of results (Juliandi, 2018; Perdana et al., 2023). This method employs a predictive-oriented approach, making it suitable for exploratory research, and it excels in estimating complex models with multiple constructs and indicators (Hair et al., 2019). PLS-SEM accommodates the analysis of both latent and observed variables, enabling us to investigate complex relationships among governance frameworks, institutional factors, innovation ecosystems, and multi-stakeholder coordination. Furthermore, its ability to provide reliable results despite smaller datasets enhances our capacity to derive meaningful insights related to our objectives.

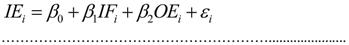

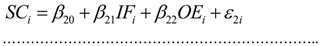

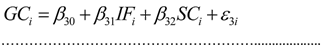

With the following short notation of Latent Variables where, Institutional Framework (IF); Innovation Ecosystem (IE); Stakeholder Coordination (SC); Global Competitiveness (GC); and Other Exogenous Variables (OE) and following Hair et al. (2019), Memon et al. (2021), and others the relationships between latent constructs (unobserved variables) and their respective observables (indicators) are specified as; We represent the structural model relationships as follows:

Where; is Path coefficients (weights) indicating the strength and direction of the relationships between the constructs. is Error terms representing the unexplained variation in each equation?

Moreover, each latent variable (l = IF, OE, IF, SC, and GE), is computed using;

Where is factor loadings for the relationship between each observed indicators and their respective latent variables; is the latent variable representing the underlying construct; is the error term associated with indicator j

In this study, innovation ecosystem is loosely defined as a dynamic network of various systems, that collaboratively facilitate and commercialize new ideas, products, and services. It includes innovation outcomes (product, process, technology, ...), access to R&D facilities, partnerships with other organizations such as universities. On the other hand, the ecosystem's effectiveness is influenced by institutional factors such as access to funding, access to skilled labor, supportive policies, and culture of creativity (Pigford et al., 2018; Liu et al., 2022). Moreover, following Ebrahimi et al. (2021) indicators including public-private partnerships (PPPs) and strategies to ensure collaboration among stakeholders including integrated platforms that facilitate knowledge sharing and communication, establishing joint research initiatives that leverage diverse expertise and resources, are considered to represent stakeholder coordination.

Table 1 details the constructs for each variable used in our model.

A single paragraph of about 200 words maximum. For research articles, abstracts should give a pertinent overview of the work. We strongly encourage authors to use the following style of structured abstracts, but without headings: (1) Background: Place the question addressed in a broad context and highlight the purpose of the study; (2) Methods: briefly describe the main methods or treatments applied; (3) Results: summarize the article’s main findings; (4) Conclusions: indicate the main conclusions or interpretations. The abstract should be an objective representation of the article and it must not contain results that are not presented and substantiated in the main text and should not exaggerate the main conclusions.

4. Findings and Discussions

This section is divided into two distinct subsections. In the first subsection, we present the findings from the inferential estimation, which employs PLS-SEM to capture the interlinkages among institutional factors, the innovation ecosystem, the governance framework, and global competitiveness in the IAIPs. The second subsection deals with qualitative analysis, utilizing both thematic analysis and SWOT analysis. The thematic analysis employed QDA to systematically categorize the qualitative data into distinct themes, allowing us to identify and highlight key patterns in the data. In the second subsection, we further examine the identified themes using the SWOT analysis, which provides a comprehensive overview of the strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats related to our subject of study.

4.1. Discussion of Econometric Results

This section presents the results of the PLS-SEM regression analysis. We begin by examining the broader relationships among the identified variables—namely, the institutional framework, innovation ecosystem, stakeholder coordination, and global competitiveness. From there, we systematically refine our approach to develop a more parsimonious model, focusing on the role of each variable in enhancing overall model performance.

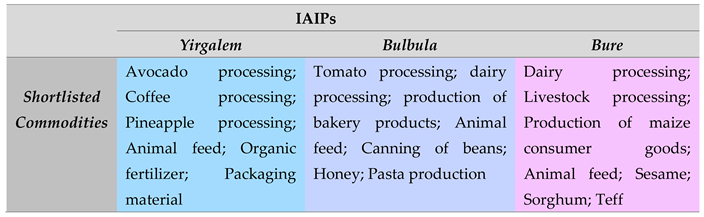

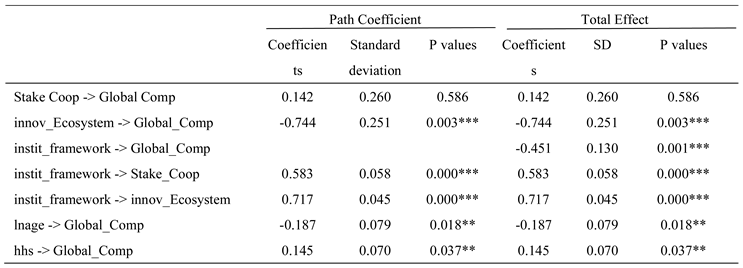

Figure 2 represents the diagrammatic illustration of our model, displaying the loading values, path coefficients, and their corresponding p-values in parentheses. A detailed definition of each construct is presented in

Table 1.

Table 2 presents a summary of quality criteria that highlight essential metrics for evaluating the latent constructs in our PLS-SEM model. The Average Variance Extracted (AVE) values indicate how well a construct captures the variance of its observed indicators, with higher values reflecting stronger construct validity. Composite Reliability (CR) assesses the internal consistency of the constructs, ensuring they accurately represent their respective concepts. Additionally, Cronbach's alpha offers further insights into the reliability of the indicators. However, we still tolerate some a Cr_alpha < 0.7 for some construct given that it is statistically significant at the 1% level suggests that, despite being below the commonly accepted threshold, the constructs still represent meaningful associations. This indicates that even though the internal consistency of the scale may not be optimal, it may still effectively capture the underlying construct, and the relationships in our SEM model are strong enough to warrant consideration despite reliability concerns. Moreover, the criticisms by Fan et al. (2016) further supports this argument, which caution against treating threshold values as strict rules and highlight an increased risk of model misspecification with high quality criteria values. Starting with complex structures, we iteratively drop some of the constructs based on the quality criteria.

The results presented in

Table 3 summarize the outer loadings for various constructs, demonstrating robust relationships between the measurement indicators and their respective constructs. The high outer loading values, (> 0.5), indicate that these indicators strongly contribute to their constructs, showcasing their reliability and significance. Most indicators for the Innovation Ecosystem and Institutional Framework also exhibit substantial loadings, reflecting their relevance in capturing the subtle aspects of innovation and governance within IAIPs. The consistently low p-values (typically below 0.01) further affirm the statistical significance of these relationships.

Table 4 presents the path coeffects and the total effects from the PLS-SEM estimation. The results indicate that significant relation between innovation Ecosystem and Global Competitiveness: The coefficient of -0.744 reveals the existing innovation ecosystem has a negative effect on global competitiveness. This finding is highly statistically significant (p < 0.01), indicating that, innovation ecosystem in the IAIPs is linked to decreased competitiveness on a global scale. This unexpected result may reflect inefficiencies or misalignments within the innovation processes that fail to yield competitive advantages, suggesting a need for a more strategic approach to innovation that aligns better with market demands. Such inefficiencies are echoed in the work of Fagerberg [93] (2005), who notes that innovation systems must be effectively aligned with market demands to foster competitiveness. Similarly, institutional Framework and Global Competitiveness (With a coefficient of -0.451) are found to go contrarily. This relationship suggests that a stronger institutional framework correlates with lower levels of global competitiveness. The result is significant (p < 0.01), implying that while strong institutions provide necessary stability, each action to realize it, might also introduce regulatory hurdles or inflexibilities that inhibit the rapid adjustments often required in the competitive global environment. This dilemma is supported by North (1990), who argues that while institutions are essential for economic performance, overly rigid frameworks can stifle innovation and responsiveness in dynamic markets.

Our findings further imply the positive influence (0.583 (p < 0.01)) from Institutional Framework to Stakeholder Coordination. It indicates a strong positive relationship between a robust institutional framework and enhanced stakeholder coordination, a notion supported by Helfat (2011). He posits that well-defined institutions facilitate cooperative interactions, which are crucial for successful innovation and competitiveness. This result emphasizes the role of effective governance structures in fostering coordination among various stakeholders, which is essential for successful innovation and competitiveness. Well-defined institutions can create an environment favorable to coordination, ultimately driving collective progress. Moreover, institutional framework is found to have a positive influence on Innovation Ecosystem in the IAIPs. The coefficient of 0.717 (p < 0.01) reflects a significant positive impact of the institutional framework on the innovation ecosystem. This finding aligns with the work of, Ebrahimi et al. (2021) who suggest that solid institutions provide essential support and resources, enhancing stakeholder coordination and overall innovative output. It supports the notion that strong institutions facilitate the creation and enhancement of an innovative environment. By providing the necessary support and resources, robust institutional frameworks can help stakeholders collaborate more efficiently, thus improving overall innovative output and capabilities.

Household size and age are the two exogenous variables in our model. Household Size has a positive relation with Global Competitiveness considering individual households (farmers, cooperatives, and processors). The positive coefficient of 0.145 (p < 0.05), indicates that an increase in household size is associated with greater global competitiveness. This effect could be attributed to larger households providing a more substantial labor force or increased consumption capacity, which in turn drives economic activity and market dynamism. On the other hand, age is found to be among the deterrent factors of Global Competitiveness. This relationship could indicate that older generations may be less adaptive to shifts in global market conditions, potentially undermining competitiveness. This result raises important questions about the implications of age dynamics in the workforce and the need for strategies that leverage the strengths of various age groups in fostering competitive advantages.

Overall, the figure emphasizes the interconnectedness of institutional frameworks, innovation ecosystem, and stakeholder coordination in enhancing the competitiveness of IAIPs in the global market. It illustrates that while innovation ecosystems are vital, their impact on competitiveness can be complex and influenced by various factors, including the effectiveness of governance structures and stakeholder engagement. The findings prompt important policy recommendations, suggesting a need to strengthen institutional frameworks and earmark resources for fostering stakeholder coordination, which can significantly drive global market competitiveness. Additionally, the negative relationship from the innovation ecosystem to global competitiveness invites further investigation into how innovation ecosystem can be practically applied to meet market needs, suggesting the need for targeted strategies.

The findings hold significant implications for practitioners, and researchers in the field of agro-industrial development. These implications can be discussed across multiple dimensions. First, the strong positive relationship between the Institutional Framework and the Innovation Ecosystem highlights the critical role of governance in fostering innovation within IAIPs. This finding implies that effective, transparent, and adaptable governance structures are essential for nurturing a conducive environment for innovation. This could involve defining clear roles, responsibilities, and processes that facilitate stakeholder engagement and streamline decision-making. Second, the moderate positive influence of Stakeholders Coordination on Global Competitiveness underscores the importance of building networks among various stakeholders, including government entities, private sector actors, development partners, and local communities. The findings suggest that for IAIPs to gain their global competitiveness, they must cultivate collaborative efforts leveraging shared resources, knowledge, and expertise. This may involve establishing formal partnerships, joint ventures, and collaborative initiatives that enhance mutual understanding and promote investment in innovation initiatives.

Moreover, the negative path coefficient from the Innovation Ecosystem to Global Competitiveness raises critical questions about the effective translation of innovative efforts into competitive advantages. This outcome suggests that while innovation is being generated, it may not be sufficiently aligned with market needs or effectively communicated to consumers. Therefore, there is a need for clearer strategies that ensure innovations are market-oriented. Practitioners should conduct market assessments to better understand the evolving demands of global markets and adjust their innovation strategies accordingly. This may involve engaging in customer feedback loops and employing agile development approaches that can quickly adapt to market changes.

In general, the implications of our findings provide important insights for developing effective governance structures, enhancing stakeholder coordination, bridging the gap between innovation and market competitiveness, and addressing factors related to the age and maturity of IAIPs. By focusing on these areas, policymakers and practitioners can significantly enhance the capacity of IAIPs to compete in the global market, fostering innovation and economic growth in the agro-industrial sector.

4.2. Qualitative Analysis and Discussion

4.2.1. Thematic Analysis

In this section, the key themes were derived from FGDs, KIIs, and government reports, utilizing QDA software.

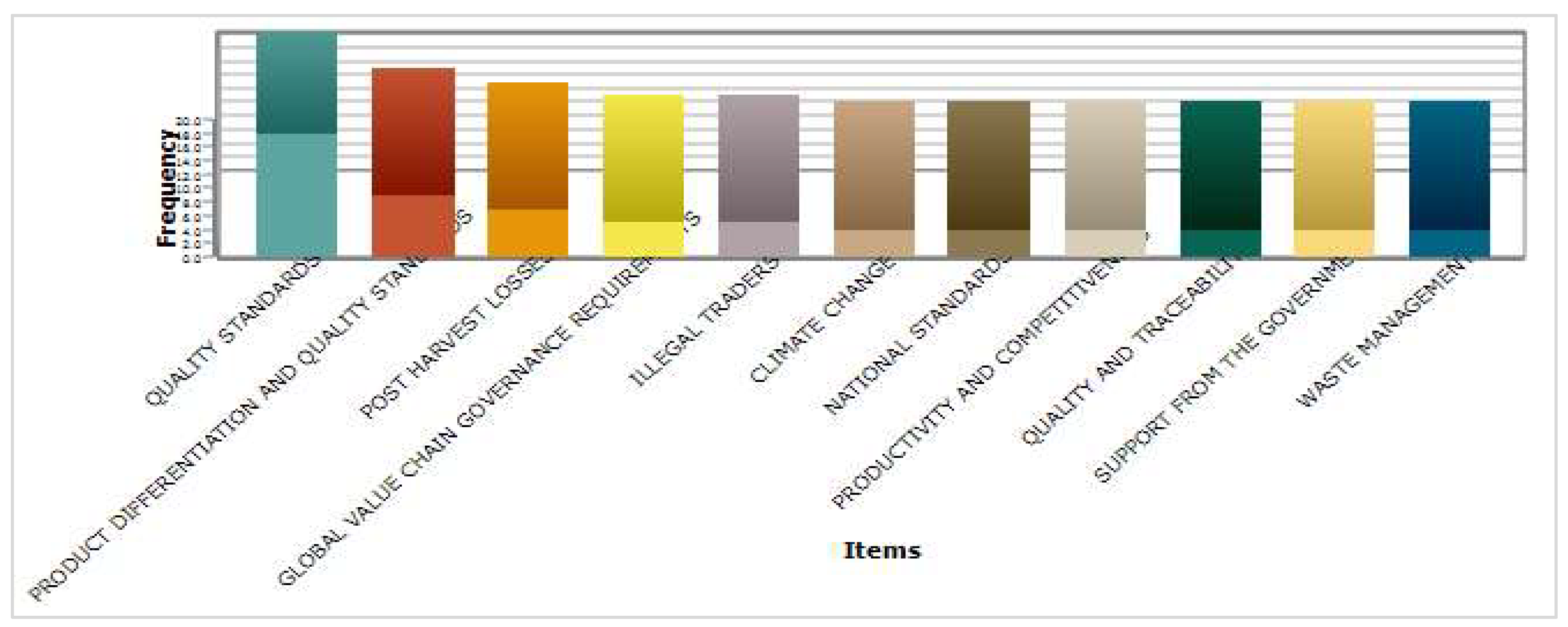

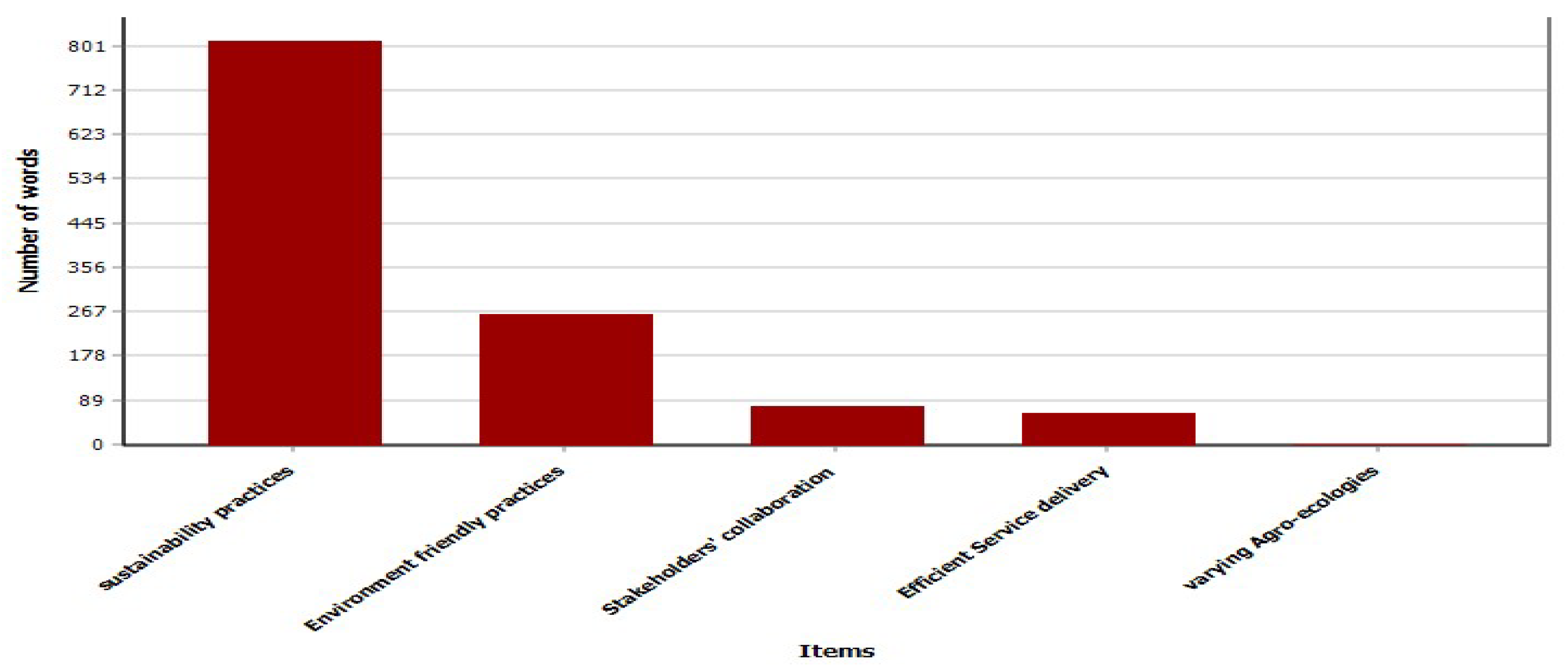

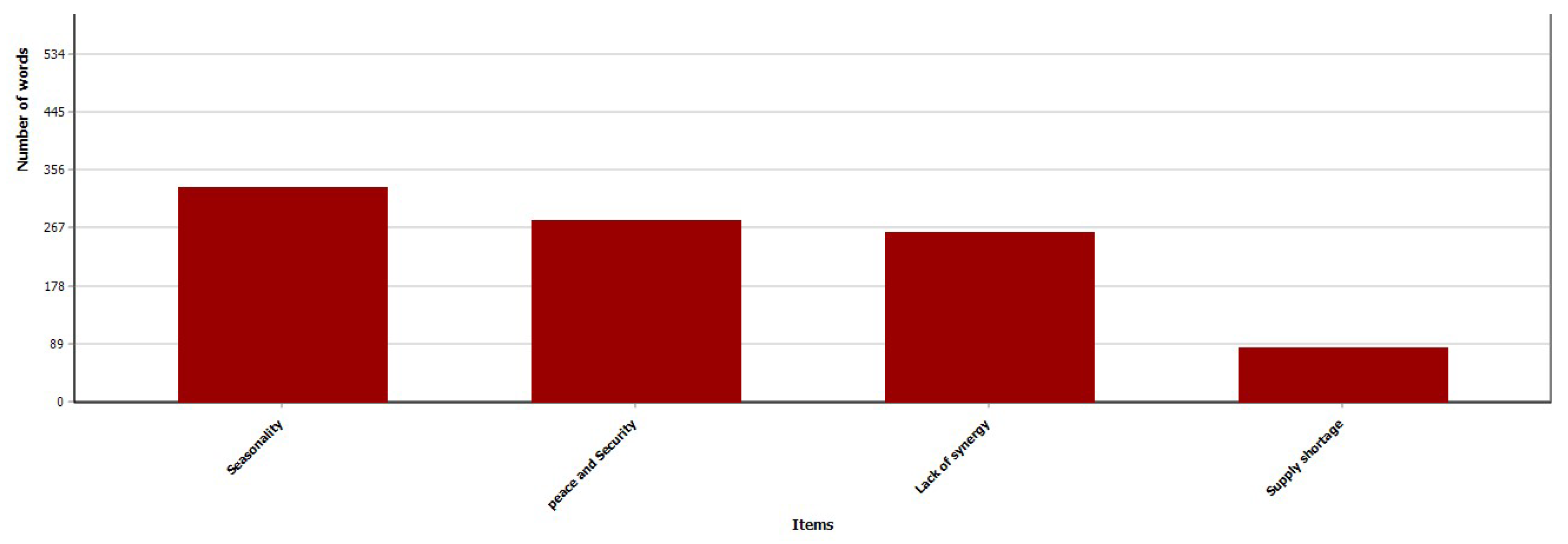

Figure 3 illustrates the broader areas (key phrases) identified, while

Figure 4 and

Figure 5 provide a more detailed breakdown of the key strengths, weaknesses, challenges, and opportunities observed in the IAIPs in Ethiopia in the process of ensuring productivity and global competitiveness. Site selection of for the IAIPs was designed to align with specific product potentials. This strategic choice is considered a significant strength and presents potential opportunities because it will provide a solid foundation for specialized agricultural development by facilitating product clustering.

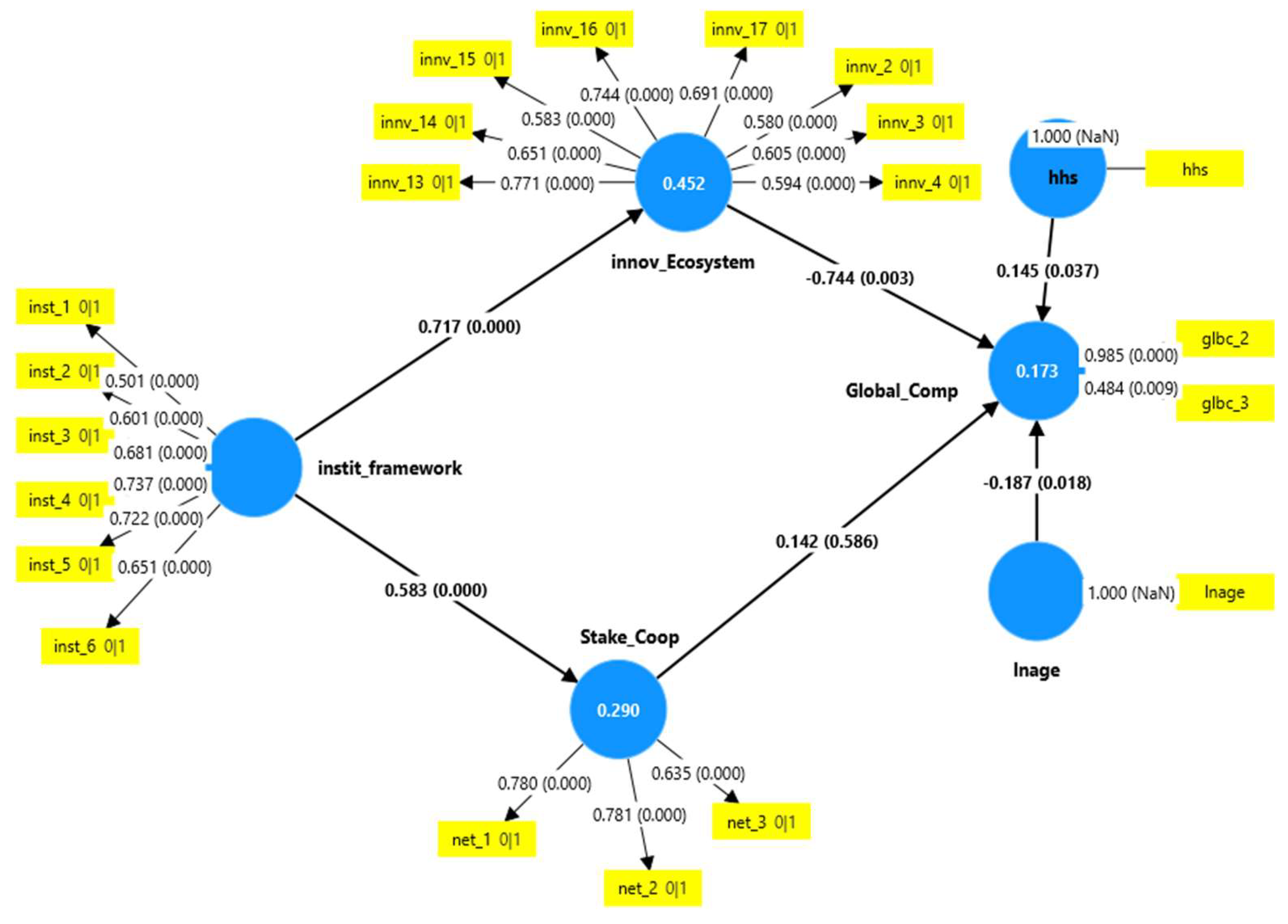

Table 5.

Shortlisted and longlisted commodity potentials in each region.

Table 5.

Shortlisted and longlisted commodity potentials in each region.

IAIPs also presents a significant opportunity for efficient specialization, product differentiation, and production clustering in the agricultural sector. Each IAIP has been strategically identified with unique commodities that highlight their individual strengths and potential contributions to the regional economy. For instance, in Yirgalem and Bulbula, five of the seven shortlisted commodities are unique to each park, while Bure features five unique products out of six shortlisted. This concentration of unique products within each park lays the groundwork for specialized production processes tailored to the specific demands of these commodities.

Moreover, the identified commodities such as avocado not only support climate-smart agricultural practices but are also available for recycling, aligning with national and international climate regulations. Furthermore, the region benefits from a relatively low-cost labor force, and partnerships with nearby academic institutions can facilitate access to research and development, further boosting productivity within the value chains. This multifaceted approach, emphasizing the linkage between infrastructure development, agricultural innovation, and market access, positions the IAIPs as a catalyst for sustainable economic growth and enhanced productivity in Ethiopia.

On the other hand, apart from the highlighted strength and potential opportunities, some weaknesses and potential threats have been underscored during the interview. Among others, persistent peace and security concerns present major challenges to sustainable investment and operational stability.

… Another important area that the government must address is peace and security, as these are crucial for building confidence among private firms to invest in the country. …. One reason private sectors hesitate to invest is due to concerns about peace and security. … Moving forward, the government needs to ensure peace and security to guarantee the safe movement of goods from production sites to final consumers. …

Moreover, the discussions from FGD indicated that current efforts concerning food safety, traceability, and product quality are still in their infancy and require considerable advancement.

… The efforts related to food safety, traceability, and product quality are still in their early stages. … Traceability systems, which are essential for tracking the origin and quality of products, are not yet fully implemented, and there are gaps in ensuring that food safety standards are consistently maintained across the supply chain. …. Food safety and traceability issue has to be underscored to ensure global competitiveness. … Quality issues with products, and challenges with traceability, making it difficult to meet market demands.

Specifically, traceability systems—crucial for monitoring the origin and quality of agricultural products—have not been fully established, resulting in inconsistencies in maintaining food safety standards throughout the supply chain. The importance of addressing these concerns is critical for achieving global competitiveness. Additionally, existing quality issues and challenges in implementing effective traceability make it difficult for producers to satisfy market demands, highlighting an urgent need for improvement in these areas.

The governance structure of development partners often faces challenges due to a lack of synergy (enhanced outcomes that can be achieved when multiple stakeholders collaborate effectively) and alignment which ensures all partners share a common understanding of goals, objectives, and strategies.

… Another area of concern in terms of governance structure is the lack of synergy and alignment. Therefore, the development partners' coordination platform needs to establish alignment to avoid overlapping tasks and ensure synergy among development partners.

In this context, a development partners' coordination platform is essential for facilitating collaboration and communication, allowing partners to coordinate their efforts and share resources efficiently. By establishing clear roles and responsibilities, the platform can help to avoid overlapping tasks and associated resource wastage. Eventually, prioritizing alignment and synergy not only enhances the effectiveness of development efforts but also maximizes the impact of collaborations, ensuring that each partner contributes uniquely and effectively to the shared objectives.

The agricultural sector is predominantly informal and not commercially oriented, which fosters a substantial informal market. Additionally, the shortage of appropriate post-harvest handling technologies, where, currently, the PHL of some commodities like avocado is as high as 40% (Urugo et al, 2024), and insufficient aggregation facilities hinders efficiency. Moreover, cooperative collection centers often lack the necessary warehousing and cold storage facilities, leading to supply seasonality and misalignments between prices paid to rural producers (very low in on-season) and the actual costs of production and transport.

4.2.2. SWOT Analysis

In this section, we conduct a SWOT analysis based on the themes identified through thematic analysis.

Table 6 summarizes landscapes in the context of IAIPs in Ethiopia characterized by various strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats (SWOT) that affect their operational efficiency and growth potential which in turn has implications on global competitiveness. Below is a discussion of each theme in the SWOT analysis, highlighting the implications for firms and local communities.

Robust infrastructure provisions, such as water, electricity, roads, and waste treatment plants, in the park are repeatedly mentioned as strengths. The presence of substantial infrastructure is a significant strength, as it enhances operational efficiency, connectivity, and overall productivity. Adequate infrastructure can facilitate smoother logistics, which is essential for attracting investment. However, there are weaknesses associated with this strength, such as the risk of underutilization and resource wastage, particularly if the infrastructure capacity exceeds current demands. Furthermore, while extensive infrastructure is advantageous, the high costs associated with maintaining this infrastructure pose a considerable threat to sustainability, requiring ongoing investment and strategic management to mitigate costs effectively. This problem becomes even more pressing if the park fails to generate sufficient payoffs over its lifetime to be self-sufficient, which is essential for ensuring long-term viability and a return on investment.

Investors in the park have been introducing climate-smart varieties of crops to improve resilience to climate change and enhances yields, which is critical for long-term sustainability and competitiveness. This strength is complemented by the interest of firms in supporting local farmers, fostering greater coordination in agricultural practices. Nonetheless, the limited access of these improved seeds and knowledge gaps among farmers concerning cultivation techniques present significant weaknesses. Additionally, while there are opportunities for better market access and sustainable practices, firms must navigate potential threats such as dependency on external seed suppliers and the risk of indigenous varieties disappearance, which could undermine local biodiversity.

Product traceability has emerged as a key criterion to ensure global competitiveness (Pakurár et al., 2015; Tessitore et al., 2022). Traceability allows tracking a product's journey and origin throughout its supply chain. This in turn enhances transparency, quality control, and compliance with regulations. Moreover, it builds consumer trust and brand loyalty in the global market as well as enables a rapid response to safety issues, ultimately strengthening companies’ competitive edge in the global market. Thus, this has been underscored during the interviews. The absence of robust systems to address quality and traceability throughout its value chain is a notable weakness in the IAIPs. This hinders both local and international market competitiveness, as insufficient attention from governmental and non-governmental organizations compounds the issue. However, this challenge also presents substantial opportunities as it pushes firms to engage in introducing traceability systems. Moreover, the varying agroecological zones of the country coupled with seasonal supply variation further complicate the traceability efforts of the private processors.

It is relatively easy to track outputs from farms within a defined 100-kilometer radius. However, challenges arise when the supply within the radius stops in off-season and products must be sourced from outside it since there is no mechanism to trace the later.

The processors’ efforts to ensure traceability for certain products, such as avocados, represent a significant strength; however, their interventions are limited to a 100-kilometer radius. This means that products sourced from outside this radius remain untraceable, particularly during the off-season when supply may extend beyond the 100-kilometer limit. On the other hand, the potential threat of regulatory pressures for compliance with traceability standards necessitates immediate attention, as failure to adapt could lead to loss of market access and reduced activity in export sectors.

Backward techniques, farmers’ limited production capacity and associated limit in agricultural supply to meet demand poses another challenge. On one hand, it encourages processors to prioritize high-quality, locally sourced ingredients, potentially enhancing market reputation. Moreover, the opportunity for processors to foster stronger community relations with farmers can lead to a more integrated supply chain. Conversely, the limited supply creates disruptions in production schedules and increases operational costs, straining firms financially and reducing their competitiveness. However, firms have the opportunity to invest in training programs that enhance farmers' abilities and encourage diversification, which would mitigate reliance on a limited number of crops. A significant threat associated with this situation is the risk to local food security and the potential for prices surge, limiting its access to the local market, especially when total supply fails to satisfy both local consumers and processors.

In addition to supply shortage, the seasonality of agricultural supplies, while posing challenges, offers firms an opportunity to leverage seasonal advantages for targeted marketing efforts. Aligning machinery maintenance schedules with off-peak agricultural seasons can minimize production disruptions, ensuring that firms are operationally ready when raw materials are available. However, the inconsistent supply of raw materials often leads to production planning difficulties and increased operational costs for firms. To counteract these weaknesses, there is an opportunity to develop storage and processing solutions to extend supply availability throughout the year, as well as to explore crop diversification strategies. That said, climate change could exacerbate these seasonal limitations, further complicating supply dynamics.

The reluctance of foreign firms to invest in the parks presents both an opportunity and a challenge. Initially, this limitation allows existing local firms to strengthen their capabilities without facing intense competition. However, the scarcity of foreign investment can restrict access to international markets, presenting a clear weakness. Specifically, the absence of foreign investors may complicate market access for domestic firms, as foreign firms typically possess better resources and networks to locate and penetrate international markets effectively. However, a strategic opportunity lies in creating targeted incentives and policies designed to attract foreign entities, coupled with strong marketing strategies to highlight the benefits of operating in the parks. The main threats include competitor countries that could lure foreign investments away and the potential for economic or political instability that may further deter investment. This low interest could partly be explained by the persisting peace and security concern. Recent peace and security concerns in the region pose significant challenges for attracting investment. The continual unrest not only disrupts operations but also contributes to a negative perception that can deter foreign investment and impact tourism, further complicating the economic landscape.

The governance structure and institutional framework surrounding IAIPs are essential for capitalizing on strengths such as infrastructure and climate-smart agricultural practices. Effective governance optimizes resource utilization, mitigates underutilization risks, and requires clear policies and transparent regulations to manage maintenance budgets, given the high costs of infrastructure upkeep. A solid institutional framework that promotes traceability systems can enhance accountability and food safety, while also improving resilience to climate change and agricultural productivity through innovative seed varieties. However, to unlock these potential benefits, it is crucial to close knowledge gaps among farmers via training and support programs. Stakeholder coordination plays a vital role in addressing the challenges related to limited agricultural supply and seasonal inputs, with firms encouraged to build direct relationships with farmers to boost engagement and productivity. As global competitiveness increasingly hinges on the ability of IAIPs to adapt to market demands and uphold high-quality production standards, addressing issues of quality, food security, and supply chain constraints is paramount. Ultimately, implementing robust traceability systems can significantly elevate product value and consumer trust, key components in enhancing the international reputation of Ethiopian agricultural products.

5. Conclusion and Policy Recommendations

5.1. Conclussion

Ethiopia's agricultural sector, as a cornerstone of its economic framework, holds substantial potential for transformation through strategic integration with industrialization. The adoption of Integrated Agro-Industrial Parks (IAIPs) serves as a critical avenue for fostering a dynamic synergy between agriculture and industry, thereby contributing to the country’s sustainable economic growth and enhancing its global competitiveness. This study provides a comprehensive evaluation of the IAIP framework by examining the underlying governance structures, institutional frameworks, stakeholder coordination mechanisms, and innovation ecosystems that support IAIPs, particularly focusing on the parks in Bulbula and Yirgalem.

Utilizing a mixed-methods approach, the study integrated quantitative data derived from surveys, government reports, and qualitative insights obtained through Focus Group Discussions (FGDs) and Key Informant Interviews (KIIs) with a diverse set of stakeholders, including farmers, cooperatives, park management teams, the Industrial Park Development Corporation (IPDC), and private investors. The analytical approach employed combined qualitative thematic analysis, Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM), and SWOT analysis, offering a holistic understanding of the factors influencing the success of IAIPs and their potential contribution to enhancing Ethiopia’s position in the global market.

The findings underscore that strong institutional framework play a pivotal role in enhancing stakeholder coordination and fostering robust innovation ecosystems within IAIPs. However, a significant gap was identified between the innovation ecosystem and stakeholder collaboration, which has had implications for Ethiopia’s global competitiveness. One of the major underlying factors is the insufficient technological adoption, particularly in the realm of digital agriculture, which is essential for streamlining the flow of information and enabling key aspects such as traceability, a crucial factor for global market integration. Furthermore, challenges such as misaligned innovation processes and rigid institutional structures appear to hinder the full realization of IAIPs' potential for global competitiveness.

The SWOT analysis identified critical strengths, such as standardized infrastructure and the introduction of climate-smart agricultural practices, which position IAIPs as promising growth hubs. However, the analysis also exposed key weaknesses, including limited private sector participation, inadequate traceability systems, and the seasonal nature of agricultural supplies, each of which presents considerable obstacles to enhancing global competitiveness. Despite these challenges, the study identified several opportunities for improving market access and fostering long-term sustainability. These opportunities, however, must be navigated carefully, given the threats posed by political instability and frequent civil unrest.

5.2. Policy Recommendations

This study emphasizes the need for adaptive governance and targeted policy frameworks that align innovation with both local and global market demands. To ensure the sustainability and competitiveness of Ethiopia’s agro-industrial sector, policies should promote research and development (R&D) within Integrated Agro-Industrial Parks (IAIPs), fostering an innovation-driven environment that keeps pace with industry trends.

Comprehensive policies should integrate governance, innovation, and stakeholder coordination, ensuring IAIPs remain responsive to market dynamics. Public-private partnerships should be emphasized to facilitate private sector involvement, critical for the financial sustainability and growth of IAIPs. Policies must also align innovation efforts with market needs, prioritizing the integration of digital agriculture tools and traceability systems, which are essential for meeting international standards and enhancing export competitiveness.

Furthermore, adaptive governance structures should enable flexible decision-making, allowing quicker responses to changing conditions. Inclusive decision-making processes involving all stakeholders, from local farmers to policymakers, are crucial to aligning IAIP goals with broader economic objectives.

Ultimately, a collaborative approach is necessary to address the challenges within Ethiopia’s agro-industrial sector. Policymakers must foster sustainable agricultural practices, improve supply systems, ensure quality, and build resilient supply chains that benefit both the processing sector and local communities, maximizing Ethiopia’s competitiveness in the global market.

Ethical Considerations and Limitations

Ethical approval for this study was obtained from the relevant research ethics committees to ensure full compliance with ethical standards and guidelines. Informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to their involvement in the study, ensuring they were fully aware of the research's objectives, their rights, and the data collection procedures. Participants were assured of the confidentiality of their responses, with all identifying information securely stored and accessible only to the research team.

This study acknowledges several limitations that may impact the reliability and generalizability of its findings. One challenge is the difficulty in accessing up-to-date data on Integrated Agro-Industrial Parks (IAIPs), which can be attributed to inconsistent data updates by relevant organizations and privacy concerns. As a result, the study may rely on outdated or incomplete datasets. Additionally, regional disparities in the development of IAIPs may result in unequal access to information and resources, complicating the generalizability of the findings across different contexts. Furthermore, the study's reliance on qualitative interview data introduces an element of subjectivity, as participants' perceptions and biases may influence their responses.

To mitigate these limitations, the study adopts a triangulation approach by integrating both qualitative and quantitative methods, drawing on diverse data sources such as governmental reports, academic literature, and cross-regional comparisons. This approach allows for a more comprehensive understanding of the subject matter and helps highlight best practices across different contexts.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: E.M.B. and J.H.; Methodology: E.M.B.; Software: E.M.B. and J.H.; Validation: E.M.B., J.H., and A.Y.A.; Formal Analysis: E.M.B.; Investigation: E.M.B. and A.Y.A.; Resources: E.M.B.; Data Curation: E.M.B.; Writing—Original Draft Preparation: E.M.B.; Writing—Review and Editing: E.M.B. and J.H.; Visualization: E.M.B. and A.Y.A.; Supervision: J.H. and A.Y.A.; Project Administration: E.M.B.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding

Informed Consent Statement

Ethical approval was obtained from the relevant research ethics committees. Informed consent was obtained from all participants, and their confidentiality was ensured throughout the research process.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available by the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

We would like to express our sincere gratitude to the Ministry of Agriculture, the Ministry of Industry of Ethiopia and Regional IPDC (Industrial Parks Development Corporations) of both Oromia and Sidama Regional States for their invaluable material and logistical support during the data collection process. Their assistance was critical to the successful completion of this research.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Adner, R. Match your innovation strategy to your innovation ecosystem. Harvard Business Review 2006, 84, 98–107. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Adamides, G. The role of innovation systems in fostering agro-industrial integration: Insights from integrated agro-industrial parks. Journal of Innovation and Sustainability 2023, 18, 145–162. [Google Scholar]

- Aldersey-Williams, M.; Barlagne, C.; Ebrahimi, N. The role of institutions in stakeholder coordination within integrated agro-industrial parks: A comparative study. Journal of Institutional and Development Studies 2020, 12, 134–146. [Google Scholar]

- Aldersey-Williams, M.; Barlagne, C.; Ebrahimi, N. Institutional frameworks and innovation ecosystems in Africa: Implications for agro-industrial integration. African Journal of Agricultural Innovation 2023, 18, 112–124. [Google Scholar]

- Anbes, A. Barriers to productivity and the challenges faced by smallholder farmers in Ethiopia. Agricultural Development Journal 2020, 18, 45–67. [Google Scholar]

- Asheim, B.T.; Boschma, R.; Cooke, P. Regional innovation systems: Theories, empirical evidence, and challenges. Regional Studies 2011, 45, 1011–1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belayneh, A.; Zewdu, E. Governance structures in integrated agro-industrial parks and their impact on agricultural productivity: A case study in Ethiopia. Agricultural Economics Review 2019, 25, 47–63. [Google Scholar]

- Belayneh, F.; Zewdu, Y. Enhancing innovation ecosystems in agro-industrial parks: A case study from Ethiopia. Innovation in Agriculture 2019, 23, 34–49. [Google Scholar]

- Bauer, M.W.; Gaskell, G. (2000). Qualitative researching with text, image, and sound: A practical handbook. SAGE Publications. [CrossRef]

- Boru, E.M.; Hwang, J.; Ahmed, A.Y. Understanding the Drivers of Agricultural Innovation in Ethiopia’s Integrated Agro-Industrial Parks: A Structural Equation Modeling and Qualitative Insights Approach. Agriculture 2025, 15, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowman, B.; Chisoro, N. The importance of innovation ecosystems in agro-industrial parks: Evidence from Africa. International Journal of Agribusiness and Innovation 2024, 29, 45–56. [Google Scholar]

- Bowman, S.; Chisoro, T. Integrated agro-industrial parks and their impact on competitiveness in developing economies. Journal of Agro-Industrial Development 2024, 8, 19–38. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, J.H. Complex adaptive systems and the emergence of global environmental sustainability. Environmental Science and Policy 2006, 9, 101–110. [Google Scholar]

- Bryman, A. (2016). Social research methods (5th ed.). Oxford University Press.

- Chin, W.W. (2010) How to write up report PLS analyses In, V.E. Vinzi, W.W. Chin, J. Henseler, & H. Wang (Eds.), Handbook of partial least squares (pp. 655–690). Springer.

- Collier, P.; Dercon, S. Agriculture as a driver of growth and job creation in Africa. World Development Perspectives 2014, 7, 11–20. [Google Scholar]

- Costa, M.; Gaziulusoy, A.I.; Öztekin, A. Sustainability transitions in agro-industrial systems: Insights from integrated agro-industrial parks. Sustainability Science 2023, 17, 175–189. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell, J.W.; Poth, C.N. (2017). Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing among five approaches (4th ed.). SAGE Publications.

- Denzin, N.K. (2017). The research act: A theoretical introduction to sociological methods (5th ed.). Aldine Transaction.

- Dong, F.; Wang, S.; Zhang, L. Institutional theory and its applications in governance frameworks: A case study of agro-industrial parks. Journal of Agricultural Economics and Policy 2021, 29, 212–227. [Google Scholar]

- Ebrahimi, N.; Barlagne, C.; Aldersey-Williams, M. Stakeholder coordination and the role of institutional frameworks in fostering innovation within agro-industrial parks. Journal of Institutional Economics 2021, 18, 215–228. [Google Scholar]

- Ebrahimi, S.; Emami, M.; Zandi, A. The role of institutional frameworks in fostering innovation ecosystems: Evidence from industrial agro-processing in developing countries. Journal of Innovation and Sustainability 2021, 13, 56–72. [Google Scholar]

- Ess, T. Economic contributions of agriculture to Ethiopia’s GDP. Ethiopian Economic Review 2021, 9, 101–115. [Google Scholar]

- Fan, W.; Williams, C.K.; Pavlou, P.A. Structural equation modeling in management research: A comprehensive review. Journal of Management Research 1999, 42, 1235–1249. [Google Scholar]

- Fagerberg, J. (2005) Innovation: A guide to the literature In, J. Fagerberg, D. Mowery, & R. Nelson (Eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Innovation (pp. 1–24). Oxford University Press.

- Fiss, P.C.; Zajac, E.J. The logic of history: Putting the past into the present in institutional analysis. Sociological Theory 2004, 22, 148–173. [Google Scholar]

- Flick, U. (2018). An introduction to qualitative research (6th ed.). SAGE Publications.

- Geels, F.W. The multi-level perspective on sustainability transitions: Responses to seven criticisms. Environmental Innovation and Societal Transitions 2011, 1, 24–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghione, G.; et al. Governance frameworks for agro-industrial integration in Ethiopia. Journal of Agricultural Policy and Governance 2021, 12, 55–70. [Google Scholar]

- Gioia, D.A.; Corley, K.G.; Hamilton, A.L. Seeking qualitative rigor in inductive research: Notes on the Gioia methodology. Organizational Research Methods 2013, 16, 15–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, R.; Saleem, S.; Ali, H. Decentralized governance in agro-industrial parks: A multi-stakeholder approach. International Journal of Governance and Policy 2020, 12, 56–73. [Google Scholar]

- Helfat, C.E. (2011). Dynamic capabilities: Understanding strategic change in organizations. Blackwell Publishing.

- Helfat, C.E. Dynamic capabilities and the organizational lifecycle. Research Policy 2011, 40, 1033–1043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, P.; Richards, S. Sustainability transitions in agro-industrial parks: The role of governance and innovation ecosystems. Environmental Policy and Governance 2019, 29, 98–110. [Google Scholar]

- Horn, A.; Masci, G.; Sabo, M. Sustainability transitions in agro-industrial parks: Integrating eco-friendly practices. Journal of Sustainable Agriculture 2024, 15, 10–22. [Google Scholar]

- Janssen, M.; Nonnenmann, M. Institutional theory and its application to governance in developing economies. International Journal of Economic Development 2017, 8, 302–314. [Google Scholar]

- Jenson, T.; King, N.; Montoro, G. Innovation networks in agro-industrial systems: Lessons from global markets. Innovation Studies Journal 2016, 11, 240–256. [Google Scholar]

- Jordan, C.; Thompson, L.; Miller, R. Innovation ecosystems and stakeholder collaboration: Enhancing sustainability in agro-industrial parks. Sustainability and Innovation Journal 2022, 9, 58–71. [Google Scholar]

- Krueger, R.A.; Casey, M.A. (2014). Focus groups: A practical guide for applied research (5th ed.). SAGE Publications.

- Larçon, J.; Vadcar, A. The role of governance in multi-stakeholder coordination in integrated agro-industrial parks. Journal of Agribusiness and Governance 2021, 19, 112–124. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.; Sun, Z.; Wang, P. Governance and the evolution of integrated agro-industrial parks: An adaptive management approach. Journal of Rural Development 2022, 26, 123–135. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.; Sun, M.; Wang, Q. Institutional factors and innovation ecosystems: The case of emerging economies. Journal of Innovation and Development 2022, 10, 232–244. [Google Scholar]

- Lundvall, B.A. (1992). National systems of innovation: Toward a theory of innovation and interactive learning. Pinter Publishers.

- Memon, M.A.; Cheah, J.H.; Chuah, F. Structural equation modeling in research. International Journal of Research in Marketing 2021, 19, 234–248. [Google Scholar]

- Morris, S.; Khan, M.; Al-Daher, M. Inclusive governance in integrated agro-industrial parks: The role of multi-stakeholder engagement. International Journal of Sustainability and Governance 2020, 14, 89–102. [Google Scholar]

- Morgan, D.L. (1997). Focus groups as qualitative research (2nd ed.). SAGE Publications.

- North, D.C. (1990). Institutions, Institutional Change, and Economic Performance. Cambridge University Press.

- NBE. (2023). National Bank of Ethiopia Annual Report. National Bank of Ethiopia.

- Pakurár, M.; Kelemen, M.; Nagy, J. The role of traceability in global competitiveness: An empirical study on the supply chain management of agricultural products. International Journal of Agricultural Science 2015, 32, 44–58. [Google Scholar]

- Patton, M.Q. (2002). Qualitative research & evaluation methods (3rd ed.). SAGE Publications.

- Pigford, A.; Liu, Z.; Zhang, F. Institutional support for innovation ecosystems: Insights from the tech sector. Journal of Technology and Innovation 2018, 7, 115–130. [Google Scholar]

- Pigford, A.; Macleod, A.; Smith, H. Sustainable transitions in agro-industrial systems: A review of the literature. Agricultural Systems 2018, 49, 49–61. [Google Scholar]

- Porter, M.E. (1990). The competitive advantage of nations. Free Press.

- Rahmadi, A.; Luthfi, A.; Susanto, A. Structural equation modeling in social science research. Journal of Social Research and Policy 2019, 15, 91–106. [Google Scholar]

- Ruppel, A. The challenges and opportunities of smallholder farming in Africa. African Development Review 2022, 14, 103–120. [Google Scholar]

- Sambo, A.; et al. Institutional frameworks for optimizing agro-industrial parks in Africa. International Journal of Sustainable Development 2021, 15, 134–148. [Google Scholar]

- Sambo, L.; Oduro, I.; Hamza, F. Multi-stakeholder coordination and innovation in integrated agro-industrial parks: Evidence from Africa. Agricultural Economics Journal 2021, 31, 50–63. [Google Scholar]

- Scott, W.R. (2001). Institutions and organizations. Sage Publications.

- Smit, C.; O'Donoghue, R.; Tewari, M. Environmental management and sustainability in agro-industrial parks: The role of eco-friendly technologies. Environmental Management and Policy 2020, 38, 89–101. [Google Scholar]

- Simon, H.A. (1996). The sciences of the artificial. MIT Press.

- Stroink, M. Complexity theory and the dynamics of agro-industrial systems: Lessons from IAIPs. Systems Research and Behavioral Science 2020, 37, 567–578. [Google Scholar]

- Tessitore, S.; Ricci, P.; Zappa, L. Enhancing product traceability and competitiveness in agro-industrial supply chains: A systematic review. Journal of Supply Chain Management 2022, 58, 1221–1235. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, D.; Evans, M.; Hooper, M. Structural equation modeling: Theory and practice in research. Journal of Research Methods 2018, 29, 50–65. [Google Scholar]

- World Bank. Agro-industrial parks and global competitiveness: The Ethiopian experience. World Bank Reports 2021, 17, 88–102. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).