Submitted:

08 February 2025

Posted:

10 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

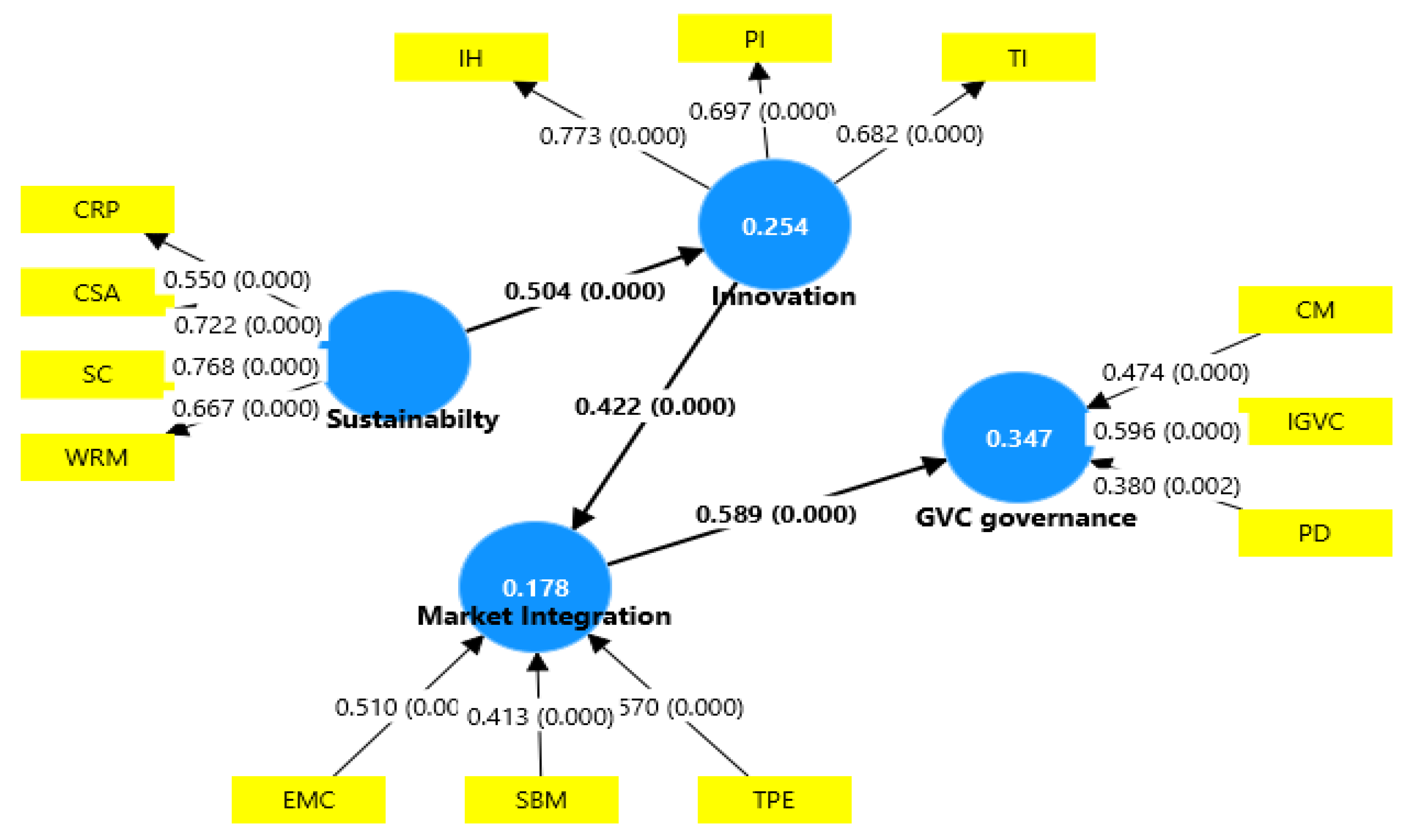

This study investigates the interconnections between sustainability practices, innovation, market integration, and Global Value Chain (GVC) governance within Ethiopia’s Integrated Agro-Industrial Parks (IAIPs). It addresses key challenges faced by IAIPs in promoting sustainability, fostering innovation, and achieving global market integration, providing insights into how sustainability-driven innovation can enhance market access and competitiveness. A quantitative, deductive research design was adopted, utilizing a stratified sampling technique across two IAIPs, Bulbula and Yirgalem. Data were collected through questionnaires from 160 respondents, and Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) was used to examine the direct and indirect relationships among sustainability, innovation, market integration, and GVC governance. The findings demonstrate that sustainability practices significantly promote innovation (β = 0.504, p < 0.001), which in turn boosts market integration (β = 0.422, p < 0.001) and strengthens GVC governance (β = 0.589, p < 0.001). Mediation analysis indicates that innovation partially mediates the effect of sustainability on market integration, while both innovation and market integration fully mediate sustainability’s impact on GVC governance. This research underscores the critical role of sustainability-driven innovation in improving market integration and GVC governance in IAIPs, suggesting that incorporating sustainability practices can enhance global competitiveness. The findings provide valuable insights for policymakers and industry stakeholders seeking to strengthen IAIPs' global market position.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

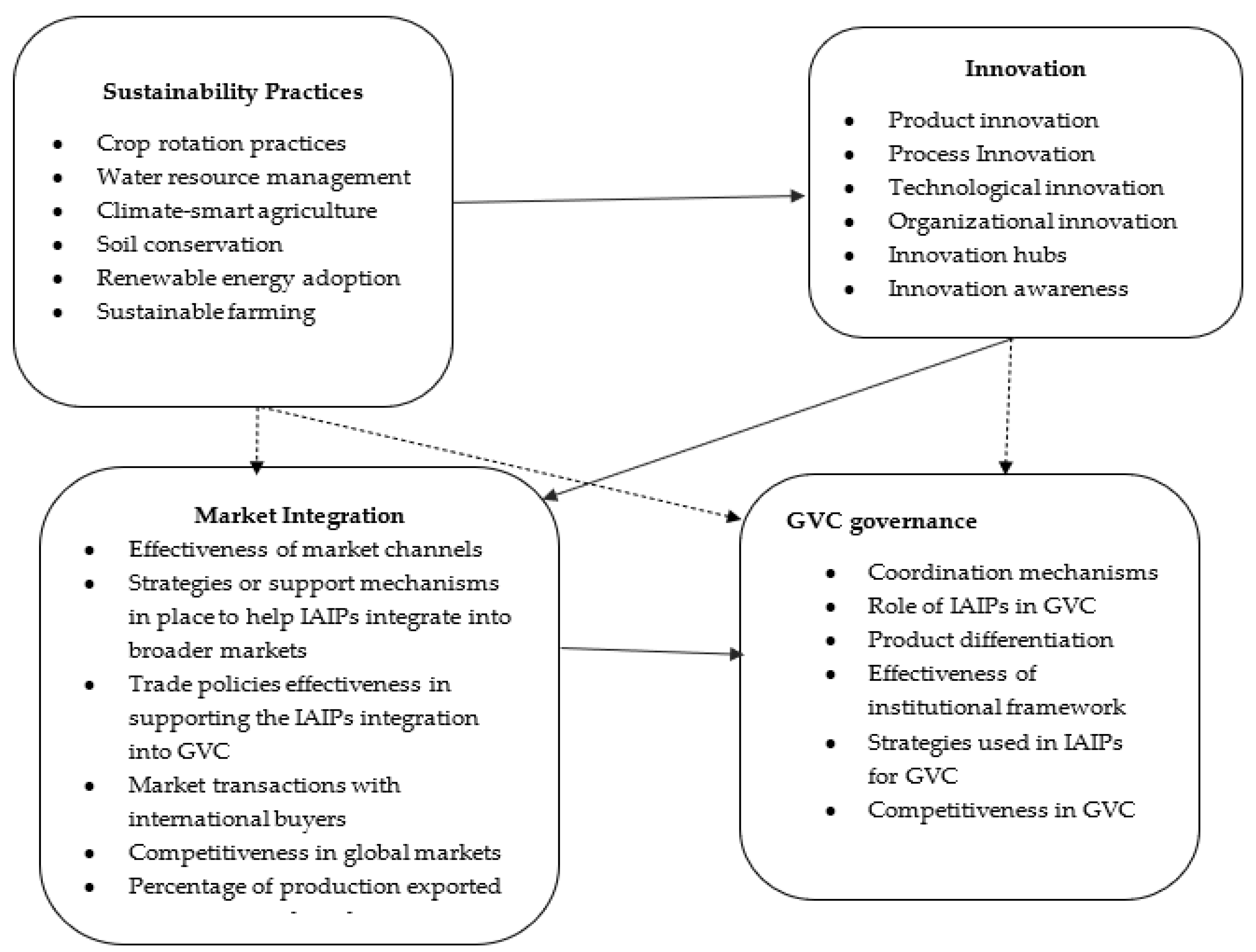

2.1. Theory and Hypothesis

2.1.1. Grounding Theory

2.1.2. Research Hypotheses

2.2. Research Design and Approach

2.3. Data Collection Methods

2.3.1. Sampling Method

2.3.2. Survey Instrument

2.3.3. Measurement of Constructs

2.4. Method of Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Assessment of Measurement (Outer) model

3.1.1. Reflective Constructs

3.1.2. Formative Constructs

3.2. Assessment of Structural Model

4. Discussion

5. Implications and Conclusions

5.1. Theoretical Implications and Contributions

5.2. Practical Implications

5.3. Study Limitations and Future Research

5.4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bait, M., Shikha, P., & Adhikari, P. (2022). Agro-industrial parks: A new pathway to industrialization in developing countries. International Journal of Agro-Economics, 30(4), 57-67.

- Boru, E.M.; Hwang, J.; Ahmed, A.Y. (2025b). Understanding the Drivers of Agricultural Innovation in Ethiopia’s Integrated Agro-Industrial Parks: A Structural Equation Modeling and Qualitative Insights Approach.

- Abobatta, W., & Fouad, H. (2024). Agro-industrial parks as a key strategy for economic development in Ethiopia. Journal of Development Studies, 50(3), 134-145.

- Barros, F., Silva, D., & Pereira, P. (2023). Industrial ecology principles and their role in sustainable agro-industrial parks. Environmental Systems and Sustainability, 12(1), 21-33.

- Brasesco, R., Souza, L., & Lima, M. (2019). Sustainable development in agro-industrial parks: Case studies from Latin America. Agricultural Economics Research, 25(6), 345-358.

- National Bank of Ethiopia (NBE). Annual Report on Economic Performance and Outlook; NBE: Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, 2023.

- Ethiopian Statistical Service (ESS). Labour Force and Migration Survey Key Findings: Employment by Major Industrial Divisions; ESS: Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, 2021.

- Balcha, E., & Serbeh-Yiadom, E. (2014b). Technological barriers and opportunities in Ethiopian agro-industrial development. African Journal of Innovation and Sustainability, 22(1), 67-81.

- Kassahun, T., Tesfaye, A., & Woldemariam, M. (2024). The role of IAIPs in enhancing value addition and export capacity in Ethiopia. Journal of Agribusiness, 15(2), 78-90.

- Zhang, M., Liu, J., & Zhang, X. (2018). Ethiopia’s agricultural transformation and its role in Africa’s economic growth. African Journal of Agricultural Economics, 27(3), 211-223.

- Guteta, K., & Worku, S. (2023). Agro-industrial park development in Ethiopia: An analysis of early-stage successes and challenges. International Journal of African Development, 42(2), 108-121.

- Haregewoin, B. (2022). Integrating Ethiopia’s agro-industrial parks into global value chains. Journal of International Business and Development, 33(1), 99-112.

- Sachs, J. D. (2015). Sustainability challenges in agro-industrial development: Global perspectives. Sustainability Science, 28(4), 176-190.

- Gebeyehu, G. (2017). Agro-industrial development in Ethiopia: A policy perspective. Ethiopian Journal of Industrial Economics, 39(3), 145-159.

- Gebremariam, S., & Feyisa, M. (2019). Challenges in Ethiopia’s agro-industrial integration and market access. Journal of African Trade, 24(4), 67-80.

- Mengistu, K. (2022). Infrastructure gaps and their impact on Ethiopia’s agro-industrial integration into global markets. Journal of Infrastructure and Economic Development, 16(1), 34-47.

- Whitfield, L., Doepke, W., & Mutisi, M. (2020). Governance and competitiveness in global value chains: The role of innovation and market integration. Global Economy Review, 17(3), 215-227.

- da Silva Medina, F., & Pokorny, J. (2022). The role of agro-industrial development in addressing food security and poverty. Journal of Development Policy, 51(2), 129-141.

- Jagemma, K., & Worku, D. (2021). Agro-industrial development and its impact on economic growth in Ethiopia. African Economic Development Review, 29(3), 56-70.

- Zakshevsky, V., Babkina, A., & Kadochnikov, V. (2019). Sustainability practices in global value chains: Lessons for agro-industrial sectors. Sustainable Development Journal, 15(4), 249-263.

- Supriyono, T. (2018). Sustainable development practices in agro-industrial parks. Sustainability Studies, 13(2), 110-120.

- Atosina, R., Talib, T., & Hennig, L. (2021). Enhancing market integration through regulatory frameworks in agro-industries. Global Market Development Review, 29(5), 76-89.

- Aydarov, D., Ghosh, P., & Smith, T. (2019). Improving competitiveness in the agro-industrial sector: A focus on global value chain integration. Journal of Agricultural Economics, 71(4), 209-223.

- Śledzik, K. (2013). The role of innovation in enhancing the competitiveness of agro-industrial firms. Journal of Economic Development, 19(2), 58-71.

- Madyda, P., & Dudzik-Lewicka, M. (2014). Innovation and competitive advantage in agro-industrial businesses. Agricultural Economics, 61(4), 45-60.

- Rambe, P., & Khaola, M. (2022). Technological innovation and its impact on competitiveness in the agro-industrial sector. International Journal of Technology and Management, 34(2), 212-227.

- Odoyo, O. (2013). Automation and digitalization in agro-processing: Benefits for Ethiopian businesses. Technology and Innovation, 11(5), 153-169.

- Barbier, E. B. (2020). Good governance and the success of global value chains: A review. Sustainable Development Review, 40(3), 97-110.

- Dekebo, F., & Kebede, D. (2023). Governance structures in global value chains: Insights for Ethiopian agro-industrial parks. Global Development and Governance Journal, 31(1), 67-82.

- Ferede, D. (2016). Overcoming barriers to market access in Ethiopia: Policy and infrastructural challenges. African Development Review, 28(4), 289-300.

- Albarracín-Gutiérrez, S., Manatovna, L., & Ramos, A. (2024). Examining the interrelationship between sustainability, innovation, and market integration in agro-industrial parks. International Journal of Agro-Industry, 38(2), 211-224.

- Balcha, E., & Serbeh-Yiadom, E. (2014a). The Ethiopian agricultural transformation agenda: Strategic alignment with agro-industrial parks. Ethiopian Development Journal, 18(2), 102-116.

- Gereffi, G., Humphrey, J., & Sturgeon, T. (2005). The governance of global value chains. Review of International Political Economy, 12(1), 78-104.

- Barney, J. (1991). Firm resources and sustained competitive advantage. Journal of Management, 17(1), 99-120.

- Rogers, E. M. (1962). Diffusion of innovations. Free Press.

- John, K. (2020). Governance and global value chains: A framework for the integration of developing economies. Development Policy Journal, 10(3), 25-38.

- Taher, M. (2012). Resource-based view of competitive advantage in the context of emerging markets. Business Economics Journal, 24(4), 134-145.

- Kabue, M., & Kilika, J. (2016). Resource-based view and competitive advantage in developing markets. International Journal of Business & Strategy, 28(2), 56-73.

- Purba, M. (2023). Resource-based view and innovation adoption: Lessons from emerging markets. Journal of Emerging Business Strategies, 16(1), 45-59.

- Virgin, H., Mayer, J., & Malik, S. (2022). Sustainability practices in agro-industrial parks: A resource-based perspective. Sustainability Practices Review, 15(4), 201-220.

- Caputo, A., Papalambros, P., & Bassi, A. (2016). Innovation diffusion in business: Insights from diffusion of innovations. Business & Technology Journal, 22(4), 187-204.

- Greenacre, L., Jannasch, D., & O’Keefe, M. (2012). Adoption of innovation: The role of information dissemination and user-centered design. Technology Management Review, 39(2), 118-130.

- Cooper, D. R., & Schindler, P. S. (2014). Business research methods (12th ed.). McGraw-Hill.

- Creswell, J. W. (2017). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approach (5th ed.). SAGE Publications.

- Kothari, C. R. (2004). Research methodology: Methods and techniques (2nd ed.). New Age International.

- Doucet, M., Karcher, S., & Spector, B. (1994). Sampling methods in research: Principles, techniques, and applications. Wiley.

- Schofield, T. (2006). Stratified sampling and quantitative research. Journal of Research Methods, 4(2), 34-44.

- Singh, J., & Mangat, P. (1996). Sampling techniques in research. Cambridge University Press.

- Bryman, A., & Bell, E. (2015). Business research methods (4th ed.). Oxford University Press.

- Dillman, D. A., Smyth, J. D., & Christian, L. M. (2014). Internet, phone, mail, and mixed-mode surveys: The tailored design method (4th ed.). Wiley.

- Fink, A. (2017). How to conduct surveys: A step-by-step guide (6th ed.). SAGE Publications.

- Sekaran, U., & Bougie, R. (2016). Research methods for business: A skill-building approach (7th ed.). Wiley.

- Chin, W. W. (1998). The partial least squares approach to structural equation modeling. In G. A. Marcoulides (Ed.), Modern methods for business research (pp. 295-336). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- Hair, J. F., Hult, G. T. M., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2014). A primer on partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM). Sage Publications.

- Cohen, L., Manion, L., & Morrison, K. (2018). Research methods in education (8th ed.). Routledge.

- Hassini, E., Surti, C., & Hachicha, W. (2012). The role of sustainability in green supply chain management. Journal of Supply Chain Management, 48(3), 11-22. [CrossRef]

- Teece, D. J. (2010). Business models, business strategy and innovation. Long Range Planning, 43(2-3), 172-194. [CrossRef]

- Schumpeter, J. A. (1942). Capitalism, socialism, and democracy (3rd ed.). Harper & Row.

- Narver, J. C., & Slater, S. F. (1990). The effect of a market orientation on business profitability. Journal of Marketing, 54(4), 20-35 . [CrossRef]

- Hair, J. F., Hult, G. T. M., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2017). A primer on partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) (2nd ed.). Sage Publications.

- Willaby, H., Stewart, D., & Rich, M. (2015). Small sample sizes and PLS-SEM: Approaches for robust results. Journal of Business Research, 68(7), 1585-1595. [CrossRef]

- Becker, J.-M., Klein, K., & Wetzels, M. (2012). Hierarchical latent variable models in PLS-SEM: Guidelines for using reflective-formative type models. Long Range Planning, 45(5-6), 359-394. [CrossRef]

- Hanafiah, M. (2020). Multicollinearity diagnostic in PLS-SEM. International Journal of Research in Business and Social Science, 9(3), 58-70.

- Fornell, C., & Bookstein, F. (1982). Two structural equation models: LISREL and PLS applied to consumer exit-voice theory. Journal of Marketing Research, 19(4), 440-452. [CrossRef]

- Hair, J. F., Hult, G. T. M., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2019). A primer on partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) (3rd ed.). Sage Publications.

- Henseler, J., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2015). A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 43(1), 115-135. [CrossRef]

- Diamantopoulos, A., & Winklhofer, H. (2001). Index construction with formative indicators: An alternative to scale development. Journal of Marketing Research, 38(2), 269-277. [CrossRef]

- Hair, J. F., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2011). PLS-SEM: Indeed, a silver bullet. Journal of Marketing Theory and Practice, 19(2), 139-152. [CrossRef]

- Sarstedt, M., Ringle, C. M., & Hair, J. F. (2022). Partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM): A comprehensive guide for research and applications. Springer.

- Haji-Othman, Y., & Yusuff, R. (2022). Assessing the reliability and validity of reflective measurement models: A case study on market intelligence and innovation adoption. Journal of Business Research, 138, 275-288. [CrossRef]

- Diacono, M., Montemurro, F., & Mininni, G. (2021). Crop rotation for soil health and sustainable agriculture: A review of the research evidence. Agriculture, 11(3), 215. [CrossRef]

- Alsaeed, A., Al-Farrah, K., & Al-Mashaqbeh, I. (2022). Water resource management for sustainable agricultural practices: The role of precision irrigation and conservation strategies. Agricultural Systems, 193, 103338. [CrossRef]

- Buytaert, W., Aerts, J., & Willems, P. (2012). Water resource management in the context of climate change and agricultural sustainability. Journal of Hydrology, 464, 53-63. [CrossRef]

- Sami, A., Raza, A., & Qamar, F. (2021). Technological innovations in sustainable agriculture: Challenges and opportunities for enhancing efficiency in crop production. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 28(3), 3041-3053. [CrossRef]

- Xing, Y., & Wang, S. (2024). Process and technological innovations in agriculture: Addressing environmental impact through sustainable practices. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 178, 121499. [CrossRef]

- Afthanorhan, A., Chin, W. W., & Islam, R. (2016). The assessment of structural model in PLS-SEM. Journal of Applied Structural Equation Modeling, 2(2), 45-67.

- Pavlov, A., & Tsarenko, Y. (2021). Application of PLS-SEM for evaluating structural models: Insights for academic and applied research. Journal of Marketing Analytics, 4(3), 45-58.

- Shi, M., Liu, Y., & Zhang, Y. (2018). Assessing the overall fit of structural equation models using PLS-SEM: A case study. Journal of Applied Business Research, 34(4), 695-704.

- Hu, L., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 6(1), 1-55.

- Hair, J. F., & Alamer, A. (2022). PLS-SEM for marketing research: Key insights and challenges. Journal of Business Research, 58(1), 50-65. [CrossRef]

- Ringle, C. M., Sarstedt, M., & Straub, D. W. (2020). A critical look at the use of PLS-SEM in marketing research. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 48(2), 245-266. [CrossRef]

- Joseph, M., Liao, S., & Chang, W. (2022). Evaluating the predictive relevance of structural equation models: Guidelines and applications. Journal of Business Research, 145, 111-123. [CrossRef]

- Kadirova, N. (2024). Sustainability and innovation: Catalysts for competitiveness in emerging markets. Sustainability, 16(4), 1349. [CrossRef]

- Kavi, S. (2024). Sustainability-driven innovation in global value chains: A systematic review. Journal of Cleaner Production, 327, 129541. [CrossRef]

- Repeshko, A. (2022). Innovation and market integration: Key drivers of international competitiveness. Journal of International Business and Economics, 25(2), 112-125. [CrossRef]

- Domazet, I., Novak, S., & Markovic, M. (2022). Innovation as a driver of market integration in emerging economies. International Journal of Innovation Management, 26(6), 1250045. [CrossRef]

- Alfaro, L., López, E., & Navarro, S. (2019). The role of market integration in global value chains. Journal of International Business Studies, 50(7), 1263-1280. [CrossRef]

- Egger, D., Kuc, S., & Wang, Z. (2021). Market integration and governance in global value chains: Evidence from emerging markets. Journal of World Business, 56(1), 1-14. [CrossRef]

- Khan, M. A., & Mubin, S. (2019). The impact of sustainability-driven innovation on market integration and global value chains. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16(22), 4349. [CrossRef]

- Rushchitskaya, E., Lysenko, S., & Taran, M. (2024). Global value chain governance: The role of sustainability-driven innovation. Journal of Business Research, 133, 224-232. [CrossRef]

- Jiao, X., Zhao, X., & Li, J. (2019). Market integration, innovation, and governance in global supply chains. Asia Pacific Journal of Management, 36(2), 289-311. [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y. (2024). Market integration and governance in global value chains: A study of Chinese firms. International Business Review, 33(1), 101-117. [CrossRef]

- Lee, J., & Gereffi, G. (2021). Market integration and innovation in global value chains: Evidence from the electronics industry. Global Networks, 21(2), 334-355. [CrossRef]

- Lema, R., Vázquez, M., & Thomas, H. (2019). Sustainable practices and innovation: Pathways to improved global value chain governance. Sustainability, 11(19), 5286. [CrossRef]

| Reflective Constructs | Items | Outer Loadings | AVE | CR |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sustainability | CRP | 0.550 | 0.564 | 0.774 |

| CSA | 0.722 | |||

| SC | 0.768 | |||

| WRM | 0.667 | |||

| Innovation | IH | 0.773 | 0.516 | 0.761 |

| PI | 0.697 | |||

| TI | 0.682 |

| Fornell-Larcker Criterion | Innovation | Sustainability |

|---|---|---|

| Innovation | (0.718) | |

| Sustainability | 0.504 | (0.682) |

| Formative Construct | Indicator | Outer Weight | Significance (p-value) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Market Integration | EMC | 0.510 | 0.000 |

| SBM | 0.413 | 0.000 | |

| TPE | 0.570 | 0.000 | |

| MTA | 0.068 | 0.616 | |

| CGM | 0.277 | 0.051 | |

| PPE | -0.085 | 0.454 | |

| GVC Governance | CM | 0.474 | 0.000 |

| IGVC | 0.596 | 0.000 | |

| PD | 0.380 | 0.002 | |

| EIF | -0.029 | 0.883 | |

| SIAIP | 0.033 | 0.820 | |

| CGVC | 0.028 | 0.833 |

| Path/Hypothesized Relationship | Path Coefficient (β)/Effect | t-value | p-value | Decision (Supported?) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sustainability→Innovation | 0.504 | 10.122 | <0.001 | Yes (Direct effect) |

| Innovation→Market Integration | 0.422 | 6.901 | <0.001 | Yes (Direct effect) |

| Market Integration→GVC Governance | 0.589 | 11.861 | <0.001 | Yes (Direct effect) |

| Sustainability→Innovation→Market Integration | 0.213 | 5.168 | <0.001 | Yes (Mediation) |

| Innovation→Market Integration→GVC Governance | 0.248 | 5.514 | <0.001 | Yes (Mediation) |

| Sustainability→Innovation→Market Integration→GVC Governance | 0.125 | 4.400 | <0.001 | Yes (Full Mediation) |

| Construct | Q² Predict | PLS-SEM RMSE | PLS-SEM MAE | LM RMSE | IA RMSE | PLS Loss | IA Loss |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GVC Governance | 0.096 | 0.962 | 0.802 | 1.404 | 1.336 | 1.404 | 1.467 |

| Innovation | 0.224 | 0.888 | 0.737 | 1.100 | 1.153 | 0.198 | 0.216 |

| Market Integration | 0.112 | 0.952 | 0.795 | 1.033 | 1.039 | 1.288 | 1.333 |

| Overall | 0.057 | 1.404 | 1.467 | 1.317 | 1.322 | 0.964 | 1.005 |

| Path | Endogenous Construct | Effect Size (f²) | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sustainability→Innovation | Innovation | 0.341 | Medium effect |

| Innovation→Market Integration | Market Integration | 0.216 | Medium effect |

| Market Integration→GVC Governance | GVC Governance | 0.532 | Large effect |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).