2.1. The Hubble Parameter and the Total Energy Density

As mentioned above, the Hubble parameter (H(t)) is given by Equation (1). A range of estimations for the H(t) for present time (H

0) based on observation data and their analysis [

13,

14] is:

H0 ≈ (2,17÷2.37) × 10-18 sec-1

The above value seems to correlate rather well with the age of Universe (t

0 ≈ 4.4 x 10

17 sec) (e.g., [

5]):

a value well within the range given above.

It is logical to examine to what degree such an observation might not be a coincidence. Therefore, we are introducing the following two key hypotheses:

1st Key Hypothesis: The Hubble parameter is proposed to be given for the whole universe time by the following equation:

where t is the elapsed time after the Big Bang.

In consistency with above hypothesis, we introduce the additional key hypothesis.

2st Key Hypothesis: The concept of dark energy remains as the repulsive gravity constituent directly related to the attractive gravity constituents (e.g., matter, radiation). Such a hypothesis introduces a dynamic form of dark energy expressed through the dark energy density

Thus, the total energy density (ρ) consists of the sum of the attractive gravity constituents

(mainly matter (

and radiation

and the repulsive gravity constituent (i.e., dark energy

Equation (4) underlines the assumption that in the present concept, the universe exists due to the balancing coexistence of gravity attractive and gravity repulsing forces pointing out towards the 3rd Newton Law of Motion [

12] concept.

The key questions here are: (a) to what degree such a concept meets the reality and (b) can it generate new knowledge useful to lead to new considerations on Universe nature and evolution?

We concentrate first at the total density evolution.

Let us consider the original first Friedmann equation for the total energy density (ρ):

Equation (5) can be used to estimate the present time value (

) using the

value of Equation (2).

a value rather close to the critical density given in literature (e.g., [

5]):

The solution of Equation (5), taken into consideration Equation (3), gives the following simple relationship for the total density as a function of time:

where

is the time when Equation (7) starts to apply and

is the corresponding density.

is most likely to relate to the Planck time scale (

) which is widely regarded as the transition point from a quantum gravitational epoch, to a classical, expanding universe and when the general relativity starts to apply. In that case, it is plausible to assume

. It is reminded that

is given by the relationship [

15].

We can apply Equation (7) with ρ and t of the present time and estimate

setting

as estimated from Equation (8), The result has as follows:

We can compare now this value with the Planck energy density scale. Recall that the Plank Energy density scale is given by the relationship:

It is clear that and are comparable!

This result is quite interesting if one takes also into consideration, that Planck energy density is directly related to the vacuum energy density

arising from quantum fluctuations of fields in space, when confined within the Planck regime. It is derived by summing the zero-point energies of quantum fields up to the Planck scale [

16].

Thus, the above findings have led to the following proposal for the universe energy density estimation:

It should be underlined that Equation (12) expresses a very important finding i.e., it seems to resolve the cosmological constant problem controversy as mentioned above. Before proceeding and trying to have a better understanding, let us examine the problem in the inverse way. Recall from above, that and Thus we can estimate the ratio: . On the other hand, by taken the estimations: sec and we obtain: . If we try to fit those two ratios into a power function with exponent n , the solution is clear: n= -2, reproducing Equation (7). It should be also undelined that by setting n= -2 we end up, through the Friedmann Equation (5), to the 1st hypothesis Equation (3).

The conclusion that can be derived here is that, if the abovementioned two hypotheses are proved to be valid, the cosmological constant problem does not exist anymore. It can be interpreted also that, if the above quantum field theory is adopted , this important finding can be considered as a first step towards the validity of the present theory.

2.2. The Universe Expansion and Total Energy

If we can derive the second derivative of R(t) expressing the Universe acceleration. We find the interesting result:

Equation (13) marks a significant departure from the present understanding on university acceleration. As discussed before, the latter seems to be widely supported but without full universal acceptance. It is worth noting, that Nielsen et al. [

3] have revisited the existing evidence for the universe accelerated expansion by analyzing the dataset of Type Ia SuperNovae (SN Ia) [

17]. A key conclusion was that the data were quite consistent with a constant rate of universe expansion.

The solution of Equation (13) gives the universe expansion:

Let us recall the original 2nd Friedmann Equation dealing with Universe acceleration:

This leads to following relation for the pressure:

To what degree Equation (16) makes sense, it is discussed later.

First, in order to get the whole picture, we consider the Friedmann energy conservation equation

Recall that the universe total energy (E) can be approximated:

Substituting

given by Equation (17), we end up with the following relation regarding universe energy rate (ER):

Equation (20) indicates that the universe energy evolution is controlled by the pressure P and consequently by the factors shaping up this pressure. Negative pressure is directly related to the energy inflow, contributing to the universe expansion.

Substituting now the pressure given by Equation (16) in the Equation (20), we obtain for the energy rate (ER):

Taking into consideration Equations (5), (14) and (21) we can express and estimate ER as follows:

This result is also interesting: ER is a constant. If this is true, energy is pumped into the universe with a constant rate. In other words, the universe evolution is characterized by an additional global constant (ER): the expectation value of the universe inflow Energy Rate (ER).

It should be noted, in addition, that the relation (22) is expected to be valid up to the Planck epoch.

Recall that the Planck time scale (

) is given by Equation (8) whereas the Planck energy scale (

) is given by the relationship [

17]:

The relations (8) and (23) can lead to the following scaling for ER:

The above relationship, if it is true, is quite significant at least for the following reasons:

- a)

The Universe seems to have its roots within its Planck regime exporting vacuum energy at a rate ER.

- b)

The expectation value of ER is continuous and constant i.e., another new universal constant dictating the Universe dynamics.

It would be interesting to investigate further, whether this vacuum energy is exported to universe in the form of energy ‘ bursts’ with a frequency .

We are closing this topic by estimating the universe total energy evolution starting from Equation (24):

In obtaining Equation (25) we have made the plausible assumption that the initial energy is scaled by the Planck energy .

2.3. Universe Composition and Pressure

We have to go back to Equation (16) addressing the pressure vs density relationship. It is reminded that the current state-of-the art suggests that at the present time, the universe is composed mainly by matter and dark energy. Keeping in mind that (a) the present study is concentrating more on setting rather refine the present concept and (b) seeking for first order approximations drawn from the state of the art, we can claim that at the present time the matter energy density (

) is given by the relationship

, which implies for the dark energy density

:

It is widely accepted that the matter related pressure is negligible and therefore, the universe total pressure mainly consists of the dark energy related pressure. Thus, for the present time:

Concerning the value of , the observation data analysis based on the cosmological constant approximates .

In the frame of the present concept and taking into consideration Equations (4) and (27) we propose:

It should be noted that there have been data past analyses considering

as a variable suggesting higher values up to

[

18]. In addition, they have been theoretical approaches considering a dynamic behavior of dark energy, like the quintessence (e.g., [

19]), in which

is a variable with values always greater than -1.

Furthermore, concerning Equation (28), a remark that could be made here, is the similarity to a fluid with a motion obeying Bernoulli theorem [

20]. It is noticed that such a theorem is applicable to steady, inviscid and isentropic flows. However, Equation (28) has been derived from the present universe properties, a universe grown enough, allowing probably to characterize transient and non-isentropic effects as marginal. This remark could make sense for one trying to get further insight into the nature of dark energy.

Departing from the present time and moving backwards to the early universe, we are entering the regime where the main attractive gravity constituent is mainly radiation. Taking into consideration that in this case,

we can estimate from Equation (16), the dark energy density for early universe:

If this is the case, we can observe that as we move from early universe to the universe of today, a mild decrease of the dark energy content from 0.8 to 0.7 is taking place. This finding needs further investigation, especially how the inflow energy is transformed to the various universe components over time.

It should be also underlined the key role of the dark energy, in ensuring a sustainable expansion of the universe, acting as a reactive force to gravity force, in conceptual agreement with the 3rd Newton Law of motion. The corresponding forcing symmetry is expressed through the conservation of

‘universe total pressure (PT)’ defined as follows:

2.4. The Hubble Tension Problem

It is also worth examining to what degree the present theory affects the Hubble tension problem mentioned in

Section 1. Looking for a representative set of observation data to work with, we ended up with the data presented in [

21]. It is a collection of data covering a good range of redshift z=0.07- 3.30. It is noted that the application of Equation (3), leads to the following simple relationship for the Hubble parameter H(z):

It is reminded that value of is given in Equation (2).

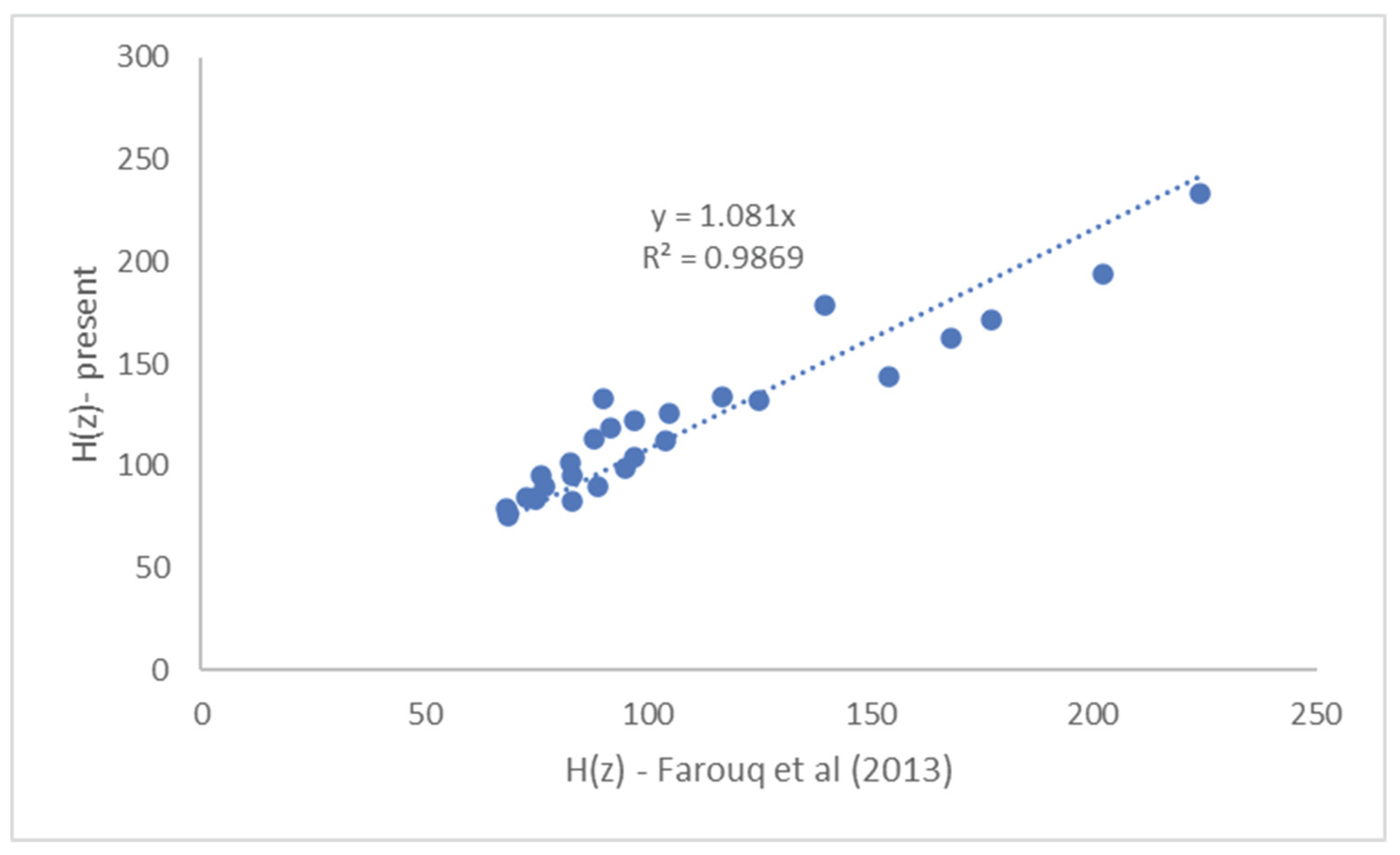

Figure 1 compares the presently produced H(z) values against the corresponding mean values reported in [

21]. The results are quite comparable if one takes into consideration that the present model shows an average overprediction over 8% which is well within the reported uncertainties. It is noticed that the H(z) data [

21] give an uncertainty which in terms of standard deviation over mean ratio, exceeds the 18%.

In conclusion the obtained results seem to confront with success the Hubble tension problem since it does not appear as a problem under the present theory. The recommendation is the present approach to be seriously considered for further observation data analysis