1. Introduction

Gluten-free noodle addresses the growing demand from consumers with celiac disease and gluten intolerance. In South America, Brazil leads this market segment, which is anticipated to expand at an annual growth rate of approximately 10.7% through 2025 [

1]. To achieve high-quality gluten-free noodle, flours must exhibit excellent hydration capacity, elasticity, and stability, while the noodle itself should possess an ideal al dente texture with desirable cohesion and resistance, emphasizing optimal hardness, elasticity, and chewiness [

2].

Extrusion cooking technology was selected as a pre-treatment step in the development of gluten-free noodles due to its ability to cook and homogenize ingredients in a continuous process, resulting in a pre-cooked flour. This flour was subsequently shaped into noodles using a cold extrusion machine. The extrusion cooking process enhances the functional properties of gluten-free flours by promoting starch gelatinization and modifying protein structures, which contributes to improved texture and greater product stability. Furthermore, this technique reduces processing time and is widely used in large-scale industrial food production [

3].

Previous research [

4,

5] explored the potential of extruded cereal-legume flour mixtures for gluten-free noodle production. Bouasla, Wójtowicz and Zidoune (2016) [

4] investigated pre-cooked rice-based noodle enriched with legume flours (yellow peas, chickpeas, and lentils) at concentrations of 10, 20, and 30%, extruded at temperatures ranging from 70 to 100 °C. The inclusion of legume flours improved nutritional quality, reduced noodle expansion and brightness, increased firmness and adhesiveness, and resulted in acceptable sensory quality with minimal cooking losses. Similarly, Suo et al. (2022) [

5] focused on gluten-free multigrain noodle enriched with chickpeas, noting significant increases in protein and fiber content, darker color, improved softness, reduced adhesiveness, lower soluble solid losses during cooking, and higher resistant starch content, suggesting beneficial effects on postprandial glycemic responses.

Blending cereal and legume flours is fundamental for enhancing gluten-free noodle’s nutritional and technological characteristics. Rice flour provides the necessary starch structure, while fiber and protein chickpea flour acts as a gluten substitute, significantly improving dough elasticity and nutritional value. This combination also positively influences the sensory acceptance of the final noodle product [

6].

Japanese rice (

Oryza sativa L.) is known for its delicate flavor and characteristic sticky texture after cooking, making it ideal for various traditional culinary preparations. Its economic significance stems from specialized agricultural practices, advanced cultivation techniques, and the selection of specific varieties adapted to regional climate and soil conditions [

7].

Chickpeas (

Cicer arietinum L.) are widely valued for their nutritional attributes, including high levels of protein, fiber, vitamins, and minerals. Regular consumption of chickpeas offers numerous health benefits, such as improved digestive health, better glycemic control, and enhanced cardiovascular wellness (Begum et al., 2023). Economically, chickpeas support substantial agricultural sectors in countries like India and Turkey. In Brazil, although domestic production is still incipient, the country imported 7.2 thousand tons of chickpeas in 2019. Nevertheless, there has been a gradual increase in initiatives to promote national cultivation, and the cultivated area is expected to become increasingly significant in the coming years [

8].

The moisture content used during cold extrusion, applied as a pre-cooking step to produce the gluten-free flour, significantly influenced the resulting noodle texture, expansion, and cooking characteristics. Moisture levels of 24%, 27%, and 30% were selected based on previous studies, which showed that moisture below 24% results in brittle structure, while levels above 30% compromise dough cohesion and final texture [

9].

Extrusion temperature is another critical parameter impacting gluten-free noodle quality, as it affects starch gelatinization and protein modification. The temperatures of 80°C, 100°C, and 120°C were strategically selected to optimize these transformations and achieve optimal noodle structure and texture. Temperatures below 80°C may inadequately gelatinize starch, while those above 120°C risk degrading the product’s components and compromising overall quality [

10].

This study hypothesizes that specific combinations of flour proportions, moisture levels, processed under extrusion cooking varied temperatures will yield extruded flours with desirable technological characteristics for shaping in cold extrusion, resulting in gluten-free noodle with excellent texture, elasticity, and satisfactory cooking performance. The objective is to develop gluten-free cooked flours by extrusion cooking considering varied proportions of chickpea and Japanese rice flours (20%/80%, 30%/70%, and 40%/60%), feed moisture contents (24, 27, and 30%), and barrel temperatures in the third heating zone (80, 100, and 120 °C) that were fusilli noodle shaped in a cold extruder. The technological and rheological properties of the extruded flours were evaluated as well as the functional and textural quality of the fusilli type noodle produced by cold extrusion.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Production of Raw Flours

Short-grain Japanese rice was purchased from Momiji (São Paulo, Brazil), and chickpeas were kindly donated by Indústria de Alimentos Granfino® (Nova Iguaçu, Brazil). The grains were milled into grits (≤1.400 mm) using an LM3600 disc mill. The resulting raw flours were packaged in hermetically sealed plastic bags and stored under refrigeration (~7°C) for a maximum of 7 days prior use. Before preparing the mixtures, the moisture content of the raw Japanese rice flours (13.39 ± 0.05%) and chickpea flours (11.36 ± 0.01%) was determined. The flours were mixed in the proportions 20/80, 30/70 and 40/60 (dry basis). The moisture content of the 20/80 and 40/60 mixtures was adjusted to 24% and 30%, and the 30/70 mixture to 27%. The mixtures were left to stand for 16 h at room temperature to equilibrate the moisture content. After this period, the moisture contents of the mixtures were verified: 20/80-24% (23.56 ± 0.05%), 40/60-24% (23.71 ± 0.17%), 20/80-30% (29.69 ± 0.07%), 40/60-30% (29.93 ± 0.01%) and 30/70-27% (26.02 ± 0.22%). The decrease in moisture content was less than 1%, which ensured compliance with the experimental design. The centesimal composition of the mixed flours was evaluated for moisture content, total proteins (nitrogen conversion factor for rice and products of 5.95) and ash [

11]. The determination of total lipids [

12].

2.2. Production of Pre-Cooked Flours by Extrusion

Extruded flours were produced following a 2³ factorial experimental design, complemented by four central points. The studied factors and their actual levels are detailed in

Table 1. Factor X1 represents the proportion of chickpea flour (%) combined with Japanese rice. Factor X2 corresponds to the adjusted moisture content (%), and factor X3 refers to the barrel temperature in the third zone. The moistened flour blends were allowed to equilibrate for 16 h before extrusion. The five conditioned flour mixtures were processed using a 19/20 DN single-screw extruder (Brabender, Duinsburg, Germany) attached to a torque rheometer PlastiCorder LabStation (Brabender, Duinsburg, Germany), equipped with a screw of compression ratio 2:1, running at 150 rpm at a constant feed rate of 4 kg/h. The feed rate was manually adjusted by varying the speed of the vertical feeder to accommodate variations in moisture content (

Table 1).

The extruder die featured a 4 mm diameter outlet. The first two heating zones were maintained at 50°C and 80°C, respectively. The third heating zone, defined as factor X3 in the experimental design, was adjusted according to the conditions described in

Table 1. Freshly extruded samples, which showed no significant expansion, were immediately cut and dried at 60°C in a fan-forced oven. The dried samples were then milled using a LM3600 disc mill and sieved through laboratory mesh sieves to obtain flour with particle size ≤ 1.400 mm. The resulting flours were packaged in hermetically sealed plastic bags and stored under refrigeration (~7°C) for up to three months until further analysis.

2.3. Properties of the Extrusion and Drying Process

The mass flow rate (

, kg/h) was measured at the beginning and at the end of each treatment, and together with the recorded torque (

, N·m), that were used to determine the specific mechanical energy (

SME, kJ/kg) delivered to the material being extruded (Equation (1)) [

13]. The moisture content of the extrudates collected and after drying was determined by the AOAC method 925.09 [

14].

2.4. Properties of Pre-Cooked Flours by Extrusion

The pre-cooked flours by extrusion were characterized by the technological properties: water absorption index (WAI) and water solubility index (WSI) (Equations (2) and (3)) [

15].

The instrumental color of the flours was determined using a colorimeter (Konica Minolta, CR-5, Tokyo, Japan). The color parameters were according to the CIELAB scale: chromaticity coordinates (a* and b*) and lightness (L*).

2.5. Noodle Production

The ingredients for the noodles were prepared using 300 g of pre-cooked extruded flour. The flour (100%) was first mixed with salt (1%) in an M5A planetary mixer for 3 minutes. Water (36%) was then gradually added over 7 minutes, based on the water absorption characteristics of each treatment. The kneading process lasted approximately 20 minutes. The dough was then shaped into fusilli-type noodles using a Noodleia cold extruder (Pastaia 2, ITALVISA, Tatuí, Brazil). After shaping, the noodles were dried in an SL102 tray dryer, cooled to room temperature, packed in airtight plastic bags, and stored under refrigeration (~7°C) for up to three months.

2.6. Pasting Properties (RVA)

The paste viscosity properties of samples were evaluated using a Rapid Visco Analyzer model RVA-4 (Newport Scientific Pty Ltd., Warriewood, Australia), employing the Standard Analysis 1 profile. Analyses were conducted with 3 g of flour samples corrected to 14% moisture (wet basis).

The parameters obtained included peak viscosity (PV), indicating the maximum viscosity during heating; trough viscosity (TV), the minimum viscosity during the holding phase; final viscosity (FV), measured at the end of the cooling period; breakdown viscosity (BV = PV – TV), representing the stability of swollen granules under heat and shear; and setback viscosity (SV = FV – TV), reflecting the tendency of starch molecules to retrograde during cooling.

2.7. Noodle Cooking Tests (Nct)

Cooking tests AACC method 16-50 [

16] consisted of cooking 10 g of noodle in 140 mL of boiling distilled water. Every 15 s after 5 min of cooking, a sample was taken to check for the presence of raw material in the central axis. The optimum cooking time (t

c) of a treatment was established when there were no visual traces of raw material (total starch gelatinization) (Equation (4)):

The volume of the raw and cooked noodle (N

v) at the optimum time was determined by water displacement. The mass of the set was recorded in a 200 mL graduated cylinder filled with water up to the top. After removing half of the water, the sample was inserted, completing the volume with the remaining water up to the top. The displaced volume corresponds to the volume of the sample (Equation (5)):

The loss of soluble solids (

) was determined by evaporation in an oven at 105 °C of 25 mL of the cooking water until constant mass was obtained (Equation (6)). Wheat noodles samples were used for comparison purposes.

2.8. Texture Profile Analysis of Noodles

The cooked noodles at the optimum cooking time (tc) were subjected to two compression cycles with a TA-XT Plus texture analyser (Stable Micro System, Surrey, UK) equipped with a load cell of 5 kg. The cylindrical probe, with a base of 50 mm in diameter, descended at 1 mm/s until deforming the sample by 50% of its initial height, with an interval of 5 seconds between cycles. The force curves were recorded by the Exponent software version 6.1.11.0. The texture parameters extracted from the force profile were: hardness (HA), elasticity (EL), cohesiveness (CO), gumminess (GO) and chewiness (CW).

2.9. Statistical Analysis

Data obtained according to the 2

3 factorial geometry with 4 increased central points can generate predictive response surfaces (Equation (7)):

Where Y is the response evaluated in the properties: 1) during the extrusion-drying process, 2) of the extruded flour, or 3) of the noodle formulated with extruded flour. xi represents the main effect of a study factor at coded levels, xi xj represents the interaction effect between two study factors, βi and βij represent respectively linear and interaction coefficients of the model, which will be obtained by regression analysis. This analysis aims to minimize the experimental error of the model (ϵ) and for this purpose the Statistica software (StatSoft, Tulsa, USA) was used.

3. Results and Discussions

3.1. Proximal Composition of Blends

Regarding the proximal composition of chickpea/rice flour blends (20/80, 30/70, and 40/60), significant changes were observed. Protein content increased from 9.84% (20/80) to 11.32% (40/60), reflecting the higher protein level in chickpea flour (15.74%) when compared to rice flour (~8.37%). Conversely, carbohydrates progressively decreased from 74.32% to 70.94%, due to chickpea flour’s lower carbohydrate content (60.82%) compared to rice flour (~77.69%). Ash content rose notably from 1.39% (20/80) to 1.71% (40/60), indicating higher mineral content in chickpea flour (2.66%) versus rice flour (~1.08%). The Total Energy Value (TEV) slightly decreased from 364.75 kcal/100g (20/80) to 354.16 kcal/100g (40/60), reflecting chickpea flour’s lower energy (322.38 kcal/100g) relative to rice flour (~375.34 kcal/100g).

3.2. Extrusion-Drying Process and Properties of Extruded Flours

Table 1 presents the experimental design with the treatment codes and the respective process parameters during extrusion and drying, as well as the hydration properties and instrumental color values of the extruded flours.

3.3. Pasting Properties of Raw Ingredients

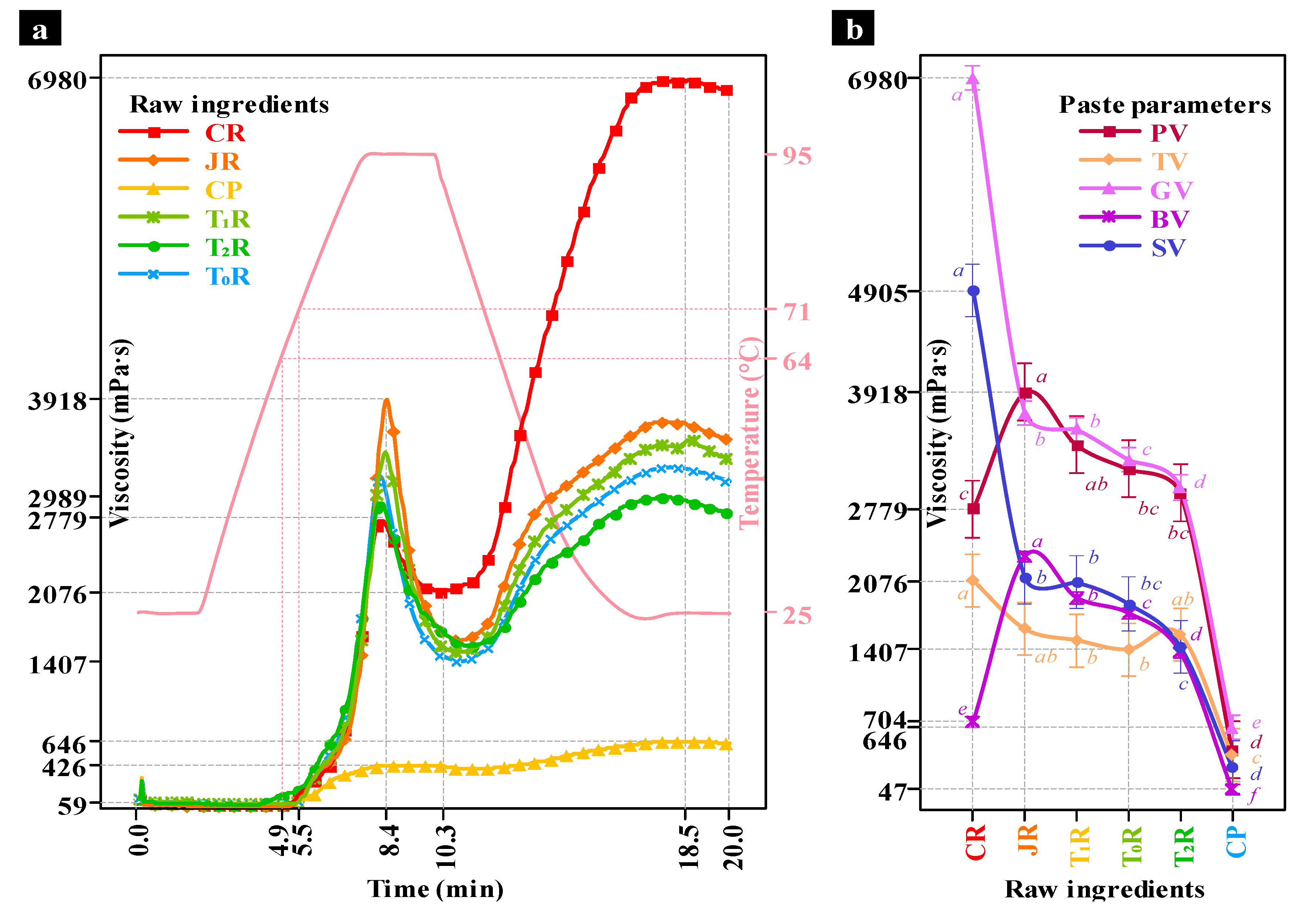

Figure 1 presents the RVA curves of the raw ingredients and the feed materials for extrusion based on Japanese rice (JR), as chickpea whole particles (CP) was added.

Determining paste viscosity is essential to understand the effect of extrusion processing on the starch behaviour, under cyclic hydrothermal conditions, achievable through rapid visco-analyzer (RVA).

Figure 1 illustrates viscosity profiles obtained with RVA for commercial rice (CR), whole chickpea particles (CP), Japanese rice (JR), and their mixtures. CR exhibited the highest peak viscosity (6980 mPa s), which is an indication of typical high-water absorption leading to great starch swelling, hence viscous paste formation. CP had significantly lower viscosity (426 mPa s), suggesting limited water absorption and different thermal behavior. Mixtures of JR and CP showed intermediate values, with viscosity decreasing as chickpea content increased, which may be attributed in part to the dilution effect of starch, since it has other components such as protein rather starch granules. Samples T₁R (20% CP), T₀R (30% CP), and T₂R (40% CP) clearly demonstrated the chickpea diluting effect on rice paste viscosity.

Figure 1b confirms these trends in specific viscosity parameters. CR again displayed significantly higher peak viscosity (PV), breakdown viscosity (BV), and gelation viscosity (GV), indicating strong stability and gel-forming ability after cooling. In contrast, CP exhibited lower parameters, indicating reduced paste stability post-thermal treatment. Statistical analysis (Tukey) confirms significant differences between treatments, emphasizing the chickpea negative impact on viscoelastic properties, which was more pronounced at higher concentrations. Such findings are crucial for optimizing extruded product characteristics regarding texture and viscosity.

Extrusion involved five flour mixtures using a single-screw extruder at a constant 4 kg/h feed rate, with feeder screw speeds adjusted between 8 and 19 rpm, in order to compensate for moisture variations. Experimental designs considered varied moisture content, extrusion temperature of the final heating zone, and flour proportions, ensuring controlled variables and reproducibility.

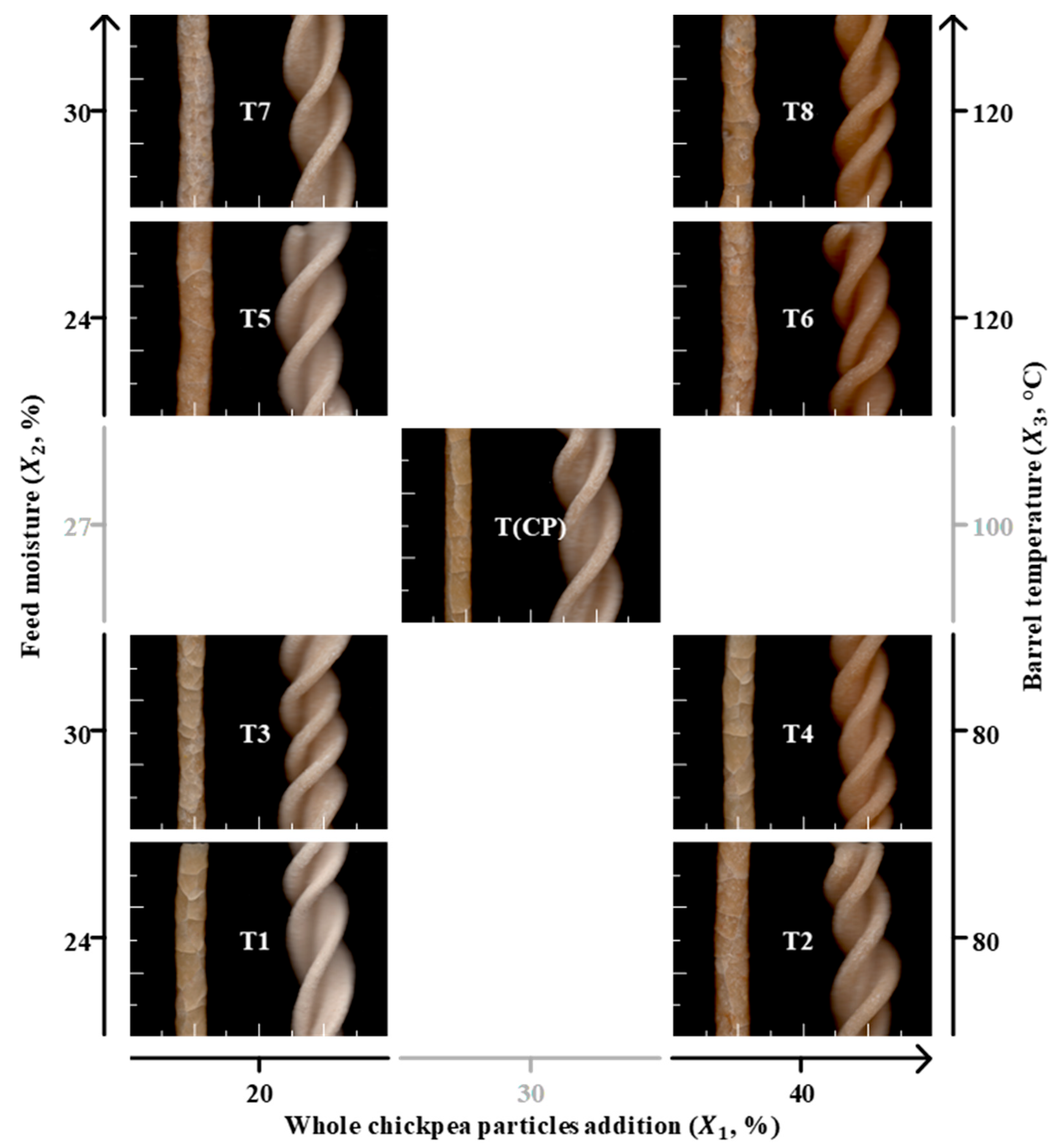

The color and structure of fusilli-type noodles, produced using pre-cooked extruded flour in a cold pasta extruder, were notably influenced by the moisture content used during the initial extrusion step. Treatments T4 and T8, processed with 30% feed moisture, resulted in darker-colored noodles. This darker appearance is likely associated with enhanced dispersion and retention of pigments from the chickpea flour, as well as the occurrence of Maillard reactions facilitated by higher moisture levels. Although starch conversion may contribute to changes in texture, the observed color alterations are more plausibly linked to subsequent dough formation and processing in the pasta machine, rather than solely to starch modification during extrusion [

17].

Extrusion temperature significantly affected the characteristics of the noodles. Higher temperatures, such as 120 °C in treatments T6 and T8, resulted in a darker color due to pigment stabilization through interactions with proteins, fibers, and lipids. Additionally, elevated temperatures intensified Maillard browning reactions between reducing sugars and amino acids. These conditions also promoted greater starch gelatinization, which contributed to the entrapment of pigments and proteins within the matrix, thereby modifying both the visual appearance and texture of the final product [

18].

The chickpea flour proportion significantly influenced noodle attributes. Increased chickpea content (40% in T2, T4, T6, T8) led to darker products due to inherent pigments like polyphenols and carotenoids reacting with starches and proteins during extrusion. Chickpea’s higher protein content improved noodle texture and structural integrity, forming starch-protein and protein-lipid complexes, enhancing hydration, elasticity, and firmness [

19].

The extrusion process facilitated starch-protein-lipid network formation, particularly amylose and amylopectin forming hydrogen bonds, significantly affecting hydration, texture, and nutritional properties. Thus, moisture, temperature, and ingredient proportions are critical in defining gluten-free noodle’s sensory, nutritional, and functional attributes, essential for optimized product quality [

20].

3.4. Characterization of Extruded Products by Extrusion

Table 1, and

Figure 2, summarizes results the feeder speeds and the semi-randomized order of treatments, designed considering the practical constraints of adjusting barrel temperature rapidly in the final heating zone. This approach allowed isolated assessment of input variables such as moisture content and feeder speed without immediate interference from temperature variations. Each extrusion trial was identified by a unique code indicating the flour proportions, mixture moisture level, and the set temperature of the extruder’s last heating zone.

Table 1 outlines these parameters and their controlled variations, ensuring comparability and minimizing external influences among treatments.

As shown in

Figure 2, moisture content, extrusion temperature, and chickpea flour proportion significantly influenced the technological and sensory attributes of fusilli-type noodles. Moisture content had a direct impact on product color and structure. Specifically, treatments T4 and T8, processed with 30% moisture, exhibited a darker color due to enhanced starch conversion and stronger interactions among water, proteins, and fibers. Higher moisture levels also promoted Maillard reactions, intensifying pigmentation and improving the retention and distribution of chickpea-derived pigments within the extruded matrix [

17].

Similarly, increasing the extrusion temperature affected both the color and structural characteristics of the noodles. Elevated temperatures, such as the 120 °C applied in treatments T6 and T8, contributed to a darker appearance. This effect is likely related to enhanced pigment fixation via complexation with proteins, fibers, or lipids, as well as increased Maillard reactions between reducing sugars and proteins. Additionally, more extensive starch conversion under these conditions supported the entrapment of pigments and proteins, influencing visual appeal and textural properties [

18].

The chickpea flour proportion also played a crucial role in determining the final characteristics. Increasing its content to 40% (as in treatments T2, T4, T6, and T8) led to darker noodles, attributed to the higher presence of polyphenols, carotenoids, and other natural pigments. These compounds interacted with starch and proteins during extrusion. Moreover, chickpea proteins contributed to improved noodle texture by forming protein-starch and protein-lipid complexes, enhancing hydration capacity, elasticity, and dough firmness [

19].

Extrusion processing enabled the formation of a structural network among starch, proteins, and lipids through gelatinization, allowing amylose and amylopectin chains to develop new interactions. The inclusion of chickpea proteins reinforced these interactions, significantly affecting water absorption and retention, binding strength, and structural stability. These molecular associations may also alter the nutritional profile of the noodles by influencing digestibility and nutrient bioavailability through the formation of complexes among proteins, fibers, and lipids [

20].

Consequently, moisture content, extrusion temperature, and flour composition are critical factors determining the technological and sensory quality of gluten-free noodle. Higher moisture and temperature conditions promoted pigment retention and product darkening, while increased chickpea flour proportion reinforced starch-protein interactions, influencing texture, structure, and nutritional quality. These interactions underline the importance of optimizing these parameters to achieve noodle products with enhanced sensory appeal and consumer acceptance [

21].

3.5. Noodles Characterization

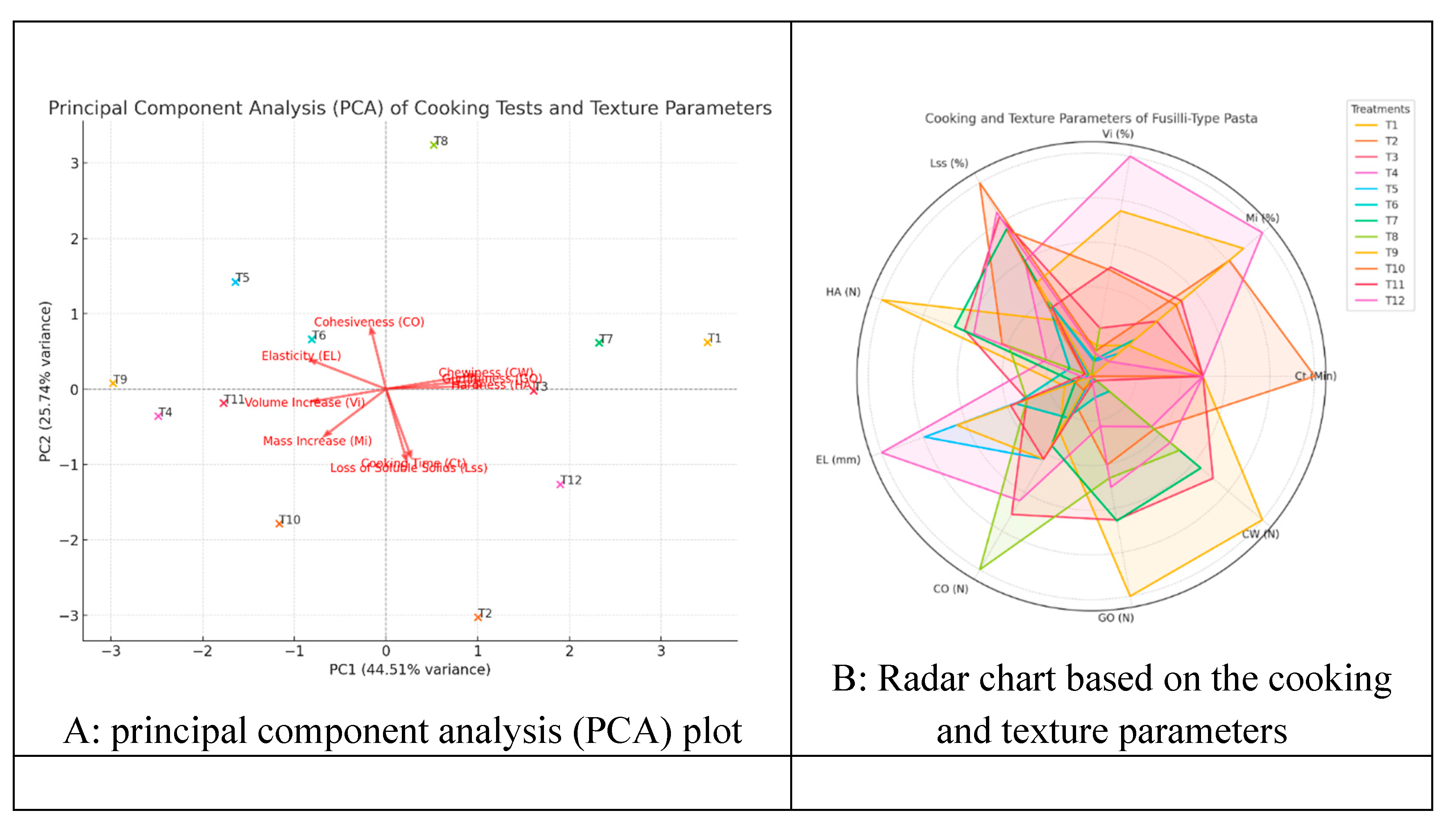

Table 2 summarizes the cooking tests and texture parameters evaluated in the cooked noodles.

Effects of cooking tests and texture parameters (

Table 2) on noodle samples:

a. Cooking Properties Analysis such as optimum cooking time (Ct), mass increase (Mi), volume increase (Vi), and loss of soluble solids (Lss) are essential for evaluating noodle quality. Optimum Ct varied between 9-11 min; T2 required the longest time (11 min), attributed to higher chickpea content requiring extended hydration and gelatinization. Most treatments cooked in 9-10 min indicated effective starch conversion caused by extrusion, by reducing cooking duration (22).

Mass increase (Mi) and volume increase (Vi) reflect water absorption capacity. T4 (173.40%) and T9 (169.90%) showed the highest Mi, while T7 had the lowest (140.07%). Higher Mi suggests greater water absorption due to hydrophilic components (starch, fibers (hemicellulose)). Vi was highest in T4 (205.04%) and lowest in T7 (147.07%), indicating superior hydration and expansion for T4. Loss of soluble solids (Lss), indicative of noodle integrity, was highest in T2 (11.40%) and T3 (10.15%), signifying weaker starch-protein interactions. T8 had the lowest Lss (5.11%), reflecting better structure retention during cooking [

23].

b. Texture Profile Analysis: hardness [HA], elasticity [EL], cohesiveness [CO], gumminess [GO], and chewiness [CW]) critically influenced noodle quality and sensory preference, especially for pasta al dente perception. As hardness (HA) measured at compression force, T1 (29.17 N) and T7 (20.15 N) exhibited the highest hardness, indicating firmer texture. T9 (4.12 N) and T5 (4.56 N) had the lowest hardness, indicating softer textures. Hardness differences relate to starch conversion and protein denaturation, probably influenced by chickpea proteins [

24].

As elasticity (EL) would be define as the noodle ability to recover shape after deformation, it was higher in T4 (2.30 mm) and T9 (2.22 mm), and lower in T2 (0.88 mm). High elasticity relates to effective amylose, amylopectin, and protein cross-linking, were essential for keeping the fusilli shape post-cooking [

10].

Cohesiveness (CO) defined as the internal binding force, ranged between 0.84 (T8) and 0.71 (T12). Higher cohesiveness indicates stronger molecular interactions, enhancing noodle structural integrity. Gumminess (GO) and chewiness (CW) reflect firmness and chewing resistance. Highest gumminess was recorded in T1 (21.09 N) and T7 (15.64 N), correlating with hardness, while T9 (3.02 N) and T10 (3.15 N) had the lowest values. Chewiness was highest in T1 (19.70 N) and T3 (14.09 N), lowest in T10 (3.02 N) and T9 (3.11 N), confirming a soft bite [

4].

c. Concerning the correlation between cooking and texture parameters, it was observed higher mass and volume increase as T4 and T9, typically displayed softer textures, suggesting excessive hydration that compromised noodle firmness. Loss of soluble solids (Lss) inversely correlated with cohesiveness as showed in treatments T2 and T12, since they presented high Lss and exhibited lower cohesiveness probably due to starch leaching that weakened their structural integrity. Hardness positively correlated with chewiness, indicating that firmer noodle requires greater chewing effort [

17].

d. The influence of processing parameters was observed among treatments affected by moisture content, extrusion temperature, and ingredient formulation: higher moisture during extrusion enhances hydration but may reduce structural integrity [

18]. Lower hardness in T9 and T5 indicates excessive starch conversion, resulting in softer texture. Higher temperatures strengthen starch-protein interactions, which may have caused starch breakdown, thus affecting firmness [

10]. Treatments produced at elevated temperatures (e.g., T4, T8) exhibited improved elasticity and cohesiveness in detriment of increasing gumminess when starch breakdown was excessive during extrusion cooking. As for ingredient formulation, chickpea-to-rice flour ratios influenced protein-starch matrix interactions. It has been reported that chickpea proteins increased elasticity and cohesiveness but excessive amounts raised soluble solids loss, negatively impacting structural integrity [

22].

Optimal texture in gluten-free noodle thus requires balancing hydration, processing parameters, and ingredient composition. Treatments T1, T3, and T7 displayed firmer textures, indicating better protein-starch interactions and adequate level of starch gelatinization. Softer textures observed in T5 and T9 could affect consumer preferences. Moderated hydration, controlled cooking, and optimized protein-starch ratios are critical for achieving high quality, desirable noodle texture and stability [

25].

Figure 3 highlights treatment variations visually regarding cooking time, mass and volume increases, and texture parameters. Principal component analysis (PCA) and Radar charts (

Figure 3) illustrate the impacts of cooking and texture parameters, emphasizing the intricate balance required between formulation and processing to achieve desirable gluten-free noodle characteristics [

17].

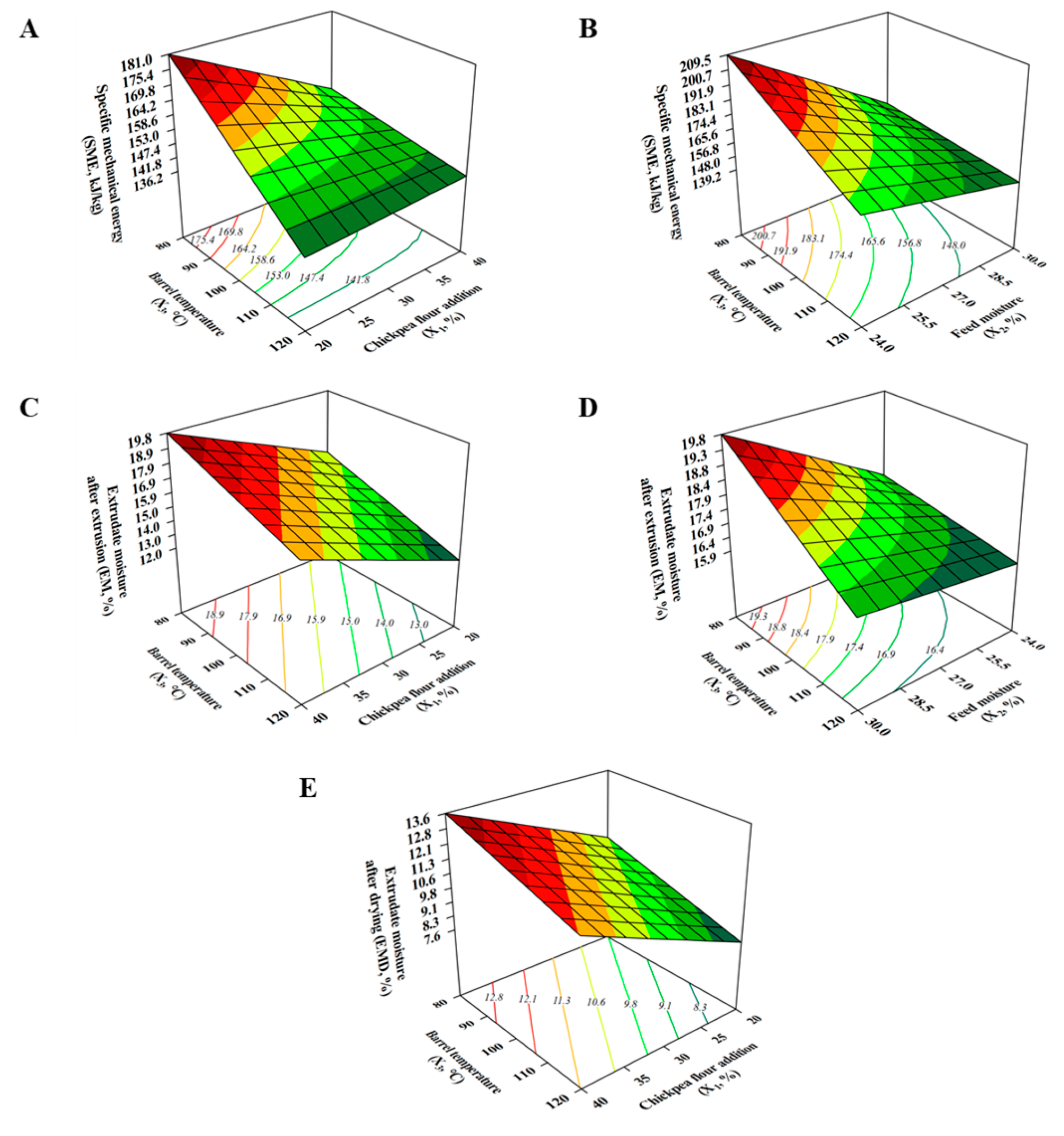

3.6. Statistical Analysis and Figure 4, Figure 5 and Figure 6 Display Response Surface Plots for the Properties of Extruded Flours and Noodles

Figure 4A-B demonstrate that chickpea addition (X₁), process moisture (X₂), and barrel temperature (X₃) inversely influenced specific mechanical energy (SME). X₁ significantly impacted SME only at low temperatures (80 °C), while X₂ effects were clearer at this temperature. X₃ strongly influenced SME at low X₁ and X₂. SME ranged from 136.2 to 209.5 kJ/kg, peaking at 20% chickpea, 24% moisture, and 80 °C, and minimizing at 20% chickpea, 30% moisture, and 120 °C. Composition, particularly fiber, protein, and moisture levels greatly influenced SME [

24]. High temperatures reduced melt viscosity, varying with fiber content, moisture, and heating levels [

17]. At 80°C, elevated viscosity due to fibers and water reduced mechanical energy applied [

26].

Figure 4C-D reveal that chickpea addition (X₁) and moisture content (X₂) directly affected extrudate moisture (EM), particularly at low temperatures (80 °C). Temperature (X₃) inversely affected EM at high moisture (30%). EM ranged from 12.44% (20% chickpea, 24% moisture, 120 °C) to 20.07% (40% chickpea, 30% moisture, 80 °C). Extrudate moisture depends on water retention by fiber and protein content and initial moisture. Lower temperature favored moisture retention by reducing vaporization, while high temperature increased vaporization, lowering moisture content [

2].

Figure 4E indicates that chickpea (X₁) directly influenced moisture content after drying (EMD), whereas temperature (X₃) inversely affected it. EMD ranged from 6.9% (20% chickpea, 120°C) to 15.27% (40% chickpea, 80°C). Higher fiber and protein contents at lower temperatures increased moisture retention, demanding more drying energy due to density and water-retaining capacity [

26].

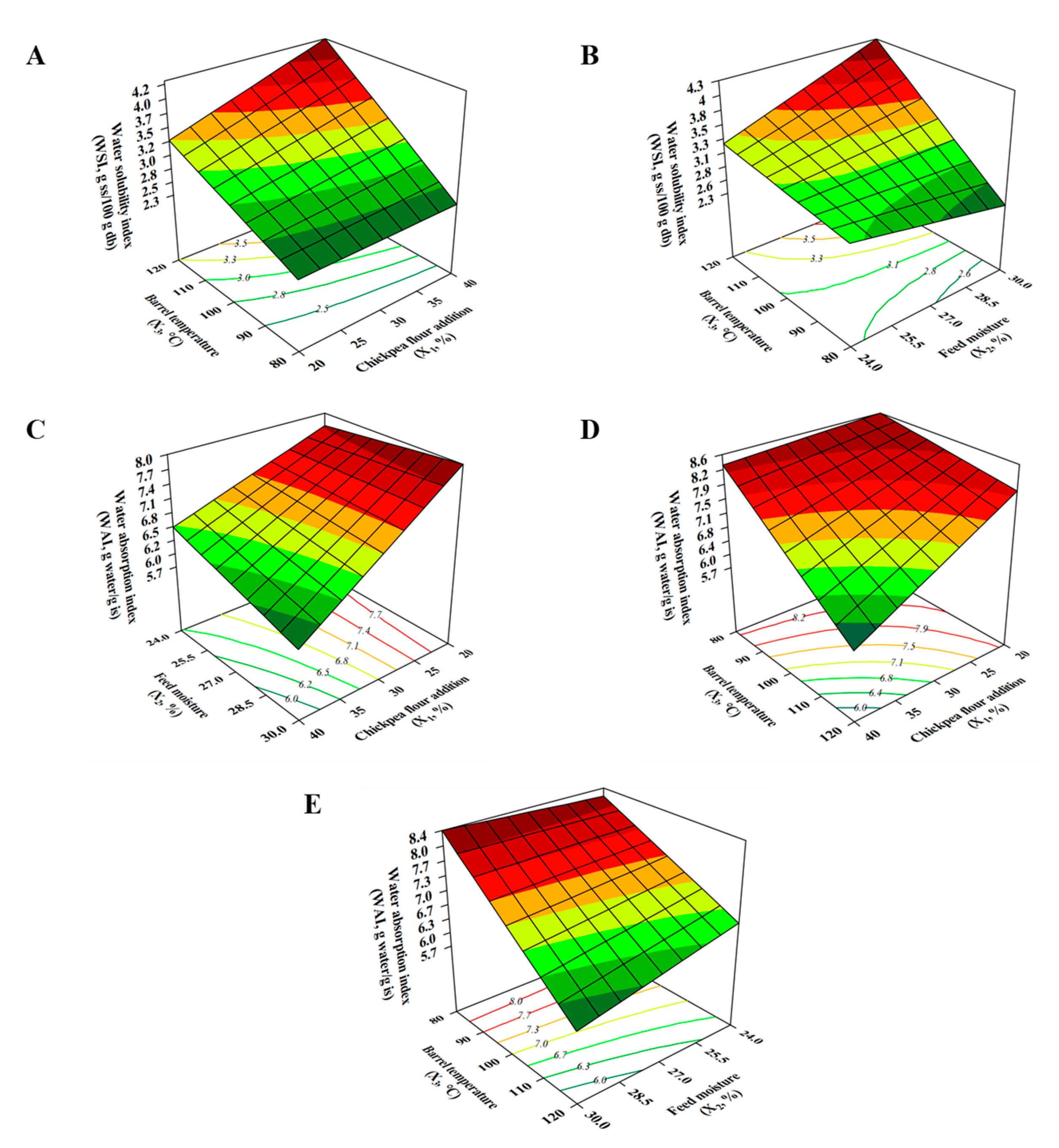

Figures 5A-B show temperature (X₃) significantly impacted the water solubility index (WSI) of extruded flours, particularly at lower moisture levels (20%). Chickpea addition (X₁) influenced WSI significantly at high temperatures (120 °C). Moisture content (X₂) had opposite effects depending on temperature, being direct at high moisture and inverse at low temperature (80 °C). WSI ranged from 6.59 to 9.77 g/g, maximum at 40% chickpea, 30% moisture, 120 °C, and minimum at 20% chickpea, 30% moisture, 80 °C. Solubilization depended on extrusion severity, particularly thermal energy, causing starch breakdown and protein denaturation. Lower moisture increased shear force, enhancing macromolecule breakdown at 80 °C and 24% moisture [

3].

Figures 5C-E indicate water absorption index (WAI) ranged from 5.7 to 8.6 g/g, influenced by chickpea addition, moisture content, and temperature. Lowest WAI occurred at 40% chickpea, 30% moisture, 120°C; highest WAI at 20% chickpea, 30% moisture, 80°C. Chickpea addition inversely affected WAI by introducing insoluble fibers, leading to reduced water absorption. High moisture and temperature exposed hydrophobic protein residues, further decreasing WAI [

17].

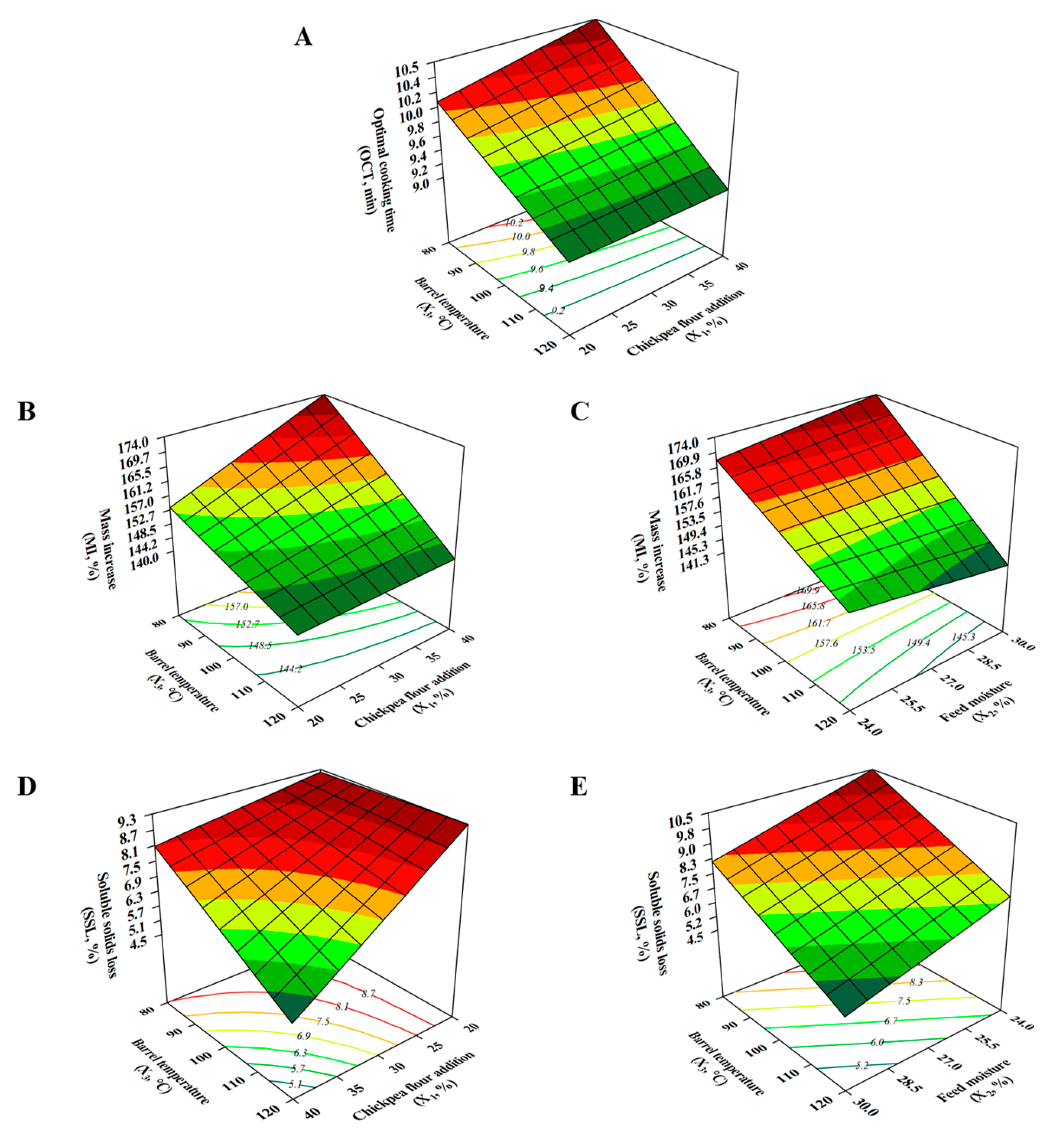

Figure 5B-C highlight that temperature (X₃) directly influenced noodle mass increase (Mi), particularly at higher chickpea levels. Moisture (X₂) directly affected Mi notably at high temperature (120°C) but inversely at lower temperatures (80°C). Mi ranged from 140.4% (20% chickpea, 30% moisture, 80 °C) to 173.5% (40% chickpea, 30% moisture, 120 °C).

Figure 5D-E illustrate chickpea (X₁) significantly affected soluble solids loss (Lss) in noodle, notably at low temperatures (80°C), with an opposite effect at 120°C. Moisture content (X₂) had a direct effect, while temperature (X₃) inversely influenced Lss. Lss ranged from 4.4% (30% moisture, 120°C) to 10.4% (24% moisture, 80°C).

Figure 6A shows optimal noodle cooking time (tc) significantly influenced by chickpea (X₁) and temperature (X₃). Temperature directly impacted tc, whereas chickpea addition inversely affected it. Optimal cooking time ranged between 9 and 11 min, longest at 80 °C, shortest at 120 °C, necessary to eliminate the opaque core of noodle [

10].

These findings demonstrate how optimal gluten-free noodle production involves carefully balancing chickpea addition, moisture levels, and extrusion temperatures to achieve desired cooking and textural properties.

4. Conclusions

The present study aimed to develop gluten-free fusilli-type noodles using extruded Japanese rice and chickpea flours and evaluate their cooking properties, texture parameters, and overall structural characteristics. The results demonstrated that formulation composition, processing conditions (moisture content and extrusion temperature), and ingredient interactions significantly influenced the quality attributes of the final product. The increase in chickpea flour proportion led to darker noodles, attributed to the natural pigments present in chickpeas, which were further intensified by higher moisture and thermal energy during extrusion. The optimal cooking time varied slightly among formulations, ranging from 9 to 11 min. Higher mass and volume increases were observed in treatments with greater chickpea content, likely due to the higher water absorption capacity of legume-derived proteins and starches. However, increased water content during extrusion (30%) led to greater solid losses (Lss), indicating that some formulations exhibited higher starch solubilization and potential loss of structural integrity. An optimal formulation would involve a balanced proportion of rice and chickpea flour, maintaining an extrusion moisture level around 25% to ensure adequate hydration while minimizing excessive solid loss. A two-component mixture composed of 40% chickpea flour and 60% Japanese rice, moistened to 30% and processed by extrusion at 80°C, ensured processing efficiency. These findings highlight the importance of fine-tuning extrusion parameters and formulation compositions to achieve high-quality gluten-free noodles. The study contributes to the growing field of alternative noodle development by demonstrating how ingredient interactions, moisture content, and processing conditions can be manipulated to enhance gluten-free noodle performance with better nutritional quality. Future studies should focus on refining formulation strategies, assessing sensory acceptance, and evaluating long-term storage stability to ensure commercial viability.

Author Contributions

S. S. Fernandes, contributed to the design of the study, data collection and drafting of the article. J.L.R. Ascheri, contributed to the data analysis, interpretation and drafting of the article. C.W.P. Carvalho, contributed to the overall project management, study design and drafting of the article. J.W. Vargas-Solorzano, contributed to the data analysis, interpretation and drafting of the article. All authors were involved in the final approval of the version to be published.

Funding

This work was funded by FAPERJ grant number; 210022/2020 and 201.000/2021.

Data Availability Statement

We encourage all authors of articles published in MDPI journals to share their research data. In this section, please provide details regarding where data supporting reported results can be found, including links to publicly archived datasets analyzed or generated during the study. Where no new data were created, or where data is unavailable due to privacy or ethical restrictions, a statement is still required. Suggested Data Availability Statements are available in section “MDPI Research Data Policies” at

https://www.mdpi.com/ethics.

Acknowledgments

To: Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior – Brasil (CAPES) – Finance Code 001; National Council for Scientific and Technological Development (CNPq), and Grant number: 210022/2020 provided by Carlos Chagas Filho Foundation for Research Support in the State of Rio de Janeiro (FAPERJ). The authors would like also to thank the Postgraduate Program in Food Science and Technology at the Federal Rural University of Rio de Janeiro.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors report there are no competing interests to declare.

References

- Mordor Intelligence Research & Advisory. Tamanho do mercado de alimentos e bebidas sem glúten do Brasil e análise de ações – Tendências e previsões de crescimento (2024–2029) [Internet]. Mordor Intelligence; 2024 [cited 2024 Jun 19]. Available from: https://www.mordorintelligence.com/pt/industry-reports/brazil-gluten-free-foods-beverages-market-industry.

- Blandino, M.; Bresciani, A.; Locatelli, M.; Loscalzo, M.; Travaglia, F.; Vanara, F.; et al. Pulse type and extrusion conditions affect phenolic profile and physical properties of extruded products. Food Chem. 2023, 403, 134369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ascheri, J.L.R. Why Food Technology by Extrusion-Cooking? Discoveries Agric Food Sci. 2024, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouasla, A.; Wójtowicz, A.; Zidoune, M.N. Gluten-free precooked rice noodle enriched with legumes flours: Physical properties, texture, sensory attributes and microstructure. LWT Food Sci Technol. 2016, 74, 67–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suo, X.; Dall’Asta, M.; Giuberti, G.; Minucciani, M.; Wang, Z.; Vittadini, E. The effect of chickpea flour and its addition levels on quality and in vitro starch digestibility of corn–rice-based gluten-free noodle. Int J Food Sci Nutr. 2022, 73, 600–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scarton, M.; Clerici, M.T.P.S. Gluten-free noodles: Ingredients and processing for technological and nutritional quality improvement. Food Sci Technol. 2022, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashim, N.; Ali, M.M.; Mahadi, M.R.; Abdullah, A.F.; Wayayok, A.; Kassim, M.S.M.; et al. Smart farming for sustainable rice production: An insight into application, challenge, and future prospect. Rice Sci. 2024, 31, 47–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Begum, N.; Khan, Q.U.; Liu, L.G.; Li, W.; Liu, D.; Haq, I.U. Nutritional composition, health benefits and bio-active compounds of chickpea (Cicer arietinum L.). Front Nutr. 2023, 10, 1218468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramos, M.J.S.; Rocha, E.B.M.; Gusmão, T.A.S.; Nascimento, A.; Lisboa, H.M.; Gusmão, R.P. Optimizing gluten-free noodle quality: The impacts of transglutaminase concentration and kneading time on cooking properties, nutritional value, and rheological characteristics. LWT Food Sci Technol. 2023, 189, 115485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, M.W.; Jothi, J.S.; Saifullah, M.; Hannan, M.A.; Mohibbullah, M. Impact of drying temperature on textural, cooking quality, and microstructure of gluten-free noodle. In: Gull A, Nayik GA, Brennan C, editors. Development of Gluten-Free Noodle. Amsterdam: Elsevier; 2024. p. 65–110. [CrossRef]

- AOAC. Official methods of analysis of AOAC International. 18th ed. 4th rev. Gaithersburg: AOAC; 2011. 1505 p.

- Bligh, E.G.; Dyer, W.J. A rapid method of total lipid extraction and purification. Can J Biochem Physiol. 1959, 37, 911–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vargas-Solórzano, J.W.; Ascheri, J.L.R.; Carvalho, C.W.P.; Takeiti, C.Y. Impact of the pretreatment of grains on the interparticle porosity of feed material and the torque supplied during the extrusion of brown rice. Food Bioprocess Technol. 2020, 13, 88–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AOAC. Official methods of analysis of the Association of Official Analytical Chemists. 18th ed. Washington (DC): AOAC; 2010.

- Vargas-Solórzano, J.W.; Carvalho, C.W.P.; Takeiti, C.Y.; Ascheri, J.L.R.; Queiroz, V.A.V. Physicochemical properties of expanded extrudates from colored sorghum genotypes. Food Res Int. 2014, 55, 37–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AACC. Approved methods of the American Association of Cereal Chemists. 9th ed. Vols. 1–2. Saint Paul: AACC; 1995.

- Delgado-Murillo, S.A.; Zazueta-Morales, J.J.; Quintero-Ramos, A.; Castro-Montoya, Y.A.; Ruiz-Armenta, X.A.; Limón-Valenzuela, V.; et al. Effect of the extrusion process on the physicochemical, phytochemical, and cooking properties of gluten-free noodle made from broken rice and chickpea flours. Biotecnia 2024, XXVI, 112–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mironeasa, S.; Coţovanu, I.; Mironeasa, C.; Ungureanu-Iuga, M. A review of the changes produced by extrusion cooking on the bioactive compounds from vegetal sources. Antioxidants. 2023, 12, 1453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gremasqui, I.A.; Giménez, M.A.; Lobo, M.O.; et al. Effect of the addition of hydrolyzed broad bean flour (Vicia faba L.) on the functional, pasting and rheological properties of a wheat-broad bean flour paste. Food Meas. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeasmen, N.; Orsat, V. Industrial processing of chickpeas (Cicer arietinum) for protein production. Crop Sci. 2025, 65, e21361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismail, B.B.; Gambo, A.; Garba, U.; Ayub, K.A. Gluten-free noodle’s consumer appeal and qualities. In: Gull A, Nayik GA, Brennan C, editors. Development of gluten-free noodle. Amsterdam: Elsevier; 2021. p. 1–18. [CrossRef]

- Bayomy, H.; Alamri, E. Technological and nutritional properties of instant noodles enriched with chickpea or lentil flour. J King Saud Univ Sci. 2022, 34, 101833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Namir, M.; Iskander, A.; Alyamani, A.; Sayed-Ahmed, E.T.A.; Saad, A.M.; Elsahy, K.; et al. Upgrading common wheat noodle by fiber-rich fraction of potato peel byproduct at different particle sizes: Effects on physicochemical, thermal, and sensory properties. Molecules. 2022, 27, 2868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Altaf, U.; Hussain, S.Z.; Qadri, T.; et al. Investigation on mild extrusion cooking for development of snacks using rice and chickpea flour blends. J Food Sci Technol. 2021, 58, 1143–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cotovanu, I.; Mironeasa, S.; Ungureanu-Iuga, M.; Mironeasa, C. Effect of extrusion parameters on the extruded products features. Int Multidiscip Sci GeoConf SGEM. 2023, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouasla, A.; Wójtowicz, A. Gluten-free rice instant noodle: Effect of extrusion-cooking parameters on selected quality attributes and microstructure. Processes. 2021, 9, 693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

a) RVA viscosity profiles of raw ingredients and feed materials for extrusion based on Japanese rice (JR), as chickpea whole particles (CP) was added. CR: commercial rice and TiR: feed materials (CP-JR, %-%, dry basis). T₁R: 20-80, T₂R: 40-60, and T₀R: 30-70. b) Change in paste parameters: peak viscosity (PV), through viscosity (TV), gelation viscosity (GV), breakdown viscosity (BV), and setback viscosity (SV). Values with different lowercase letters, on a parameter, differ from each other according to the Tukey test.

Figure 1.

a) RVA viscosity profiles of raw ingredients and feed materials for extrusion based on Japanese rice (JR), as chickpea whole particles (CP) was added. CR: commercial rice and TiR: feed materials (CP-JR, %-%, dry basis). T₁R: 20-80, T₂R: 40-60, and T₀R: 30-70. b) Change in paste parameters: peak viscosity (PV), through viscosity (TV), gelation viscosity (GV), breakdown viscosity (BV), and setback viscosity (SV). Values with different lowercase letters, on a parameter, differ from each other according to the Tukey test.

Figure 2.

Scanned images of dried extrudates produced by extrusion cooking and their corresponding noodles shaped by cold extrusion. Image dimension: 4×3 cm.

Figure 2.

Scanned images of dried extrudates produced by extrusion cooking and their corresponding noodles shaped by cold extrusion. Image dimension: 4×3 cm.

Figure 3.

(A) and (B) principal component analysis (PCA) plot and Radar chart based on the cooking and texture parameters, respectively; Ct: optimum cooking time, Mi: mass increase, Vi: volume increase, Lss: loss of soluble solids. HA: Hardness, EL: Elasticity, CO: cohesiveness, GO: gumminess, CW: Chewiness.

Figure 3.

(A) and (B) principal component analysis (PCA) plot and Radar chart based on the cooking and texture parameters, respectively; Ct: optimum cooking time, Mi: mass increase, Vi: volume increase, Lss: loss of soluble solids. HA: Hardness, EL: Elasticity, CO: cohesiveness, GO: gumminess, CW: Chewiness.

Figure 4.

Effect of chickpea rates and feed moisture on the A), B): specific mechanical energy input during extrusion cooking; C), D): Extrudates moisture after extrusion; E) Extrudates moisture after drying.

Figure 4.

Effect of chickpea rates and feed moisture on the A), B): specific mechanical energy input during extrusion cooking; C), D): Extrudates moisture after extrusion; E) Extrudates moisture after drying.

Figure 5.

Effect of chickpea rates and feed moisture on the extruded flour properties. A), B): Water solubility index; C-E): Water absorption index.

Figure 5.

Effect of chickpea rates and feed moisture on the extruded flour properties. A), B): Water solubility index; C-E): Water absorption index.

Figure 6.

Effect of chickpea rates and Feed moisture on the Noodles properties. A): Optimal cooking time; B), C): Mass increase; D), E): Soluble solids loss.

Figure 6.

Effect of chickpea rates and Feed moisture on the Noodles properties. A): Optimal cooking time; B), C): Mass increase; D), E): Soluble solids loss.

Table 1.

Experimental design and properties evaluated in the extrusion-drying processes and in the extruded flours.

Table 1.

Experimental design and properties evaluated in the extrusion-drying processes and in the extruded flours.

| Experimental |

|

Treatment |

|

Process properties |

|

Properties of extruded flour |

| Design |

|

Code |

|

Extrusion |

|

Drying |

|

Hydration |

|

Instrumental color |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Cooking |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| % |

% |

|

|

|

|

Order |

rpm |

kJ/kg |

|

% |

% |

|

g s/g |

g w/g |

|

- |

- |

- |

| 20 |

24 |

80 |

|

T1 |

|

4° |

8 |

255.70 |

|

14.70 |

9.15 |

|

8.90 |

3.45 |

|

90.01 |

0.05 |

15.67 |

| 40 |

24 |

80 |

|

T2 |

|

11° |

10 |

201.45 |

|

17.93 |

13.61 |

|

8.03 |

4.13 |

|

89.27 |

-0.19 |

19.04 |

| 20 |

30 |

80 |

|

T3 |

|

5° |

17 |

173.12 |

|

16.32 |

11.20 |

|

9.15 |

3.44 |

|

87.20 |

1.77 |

24.55 |

| 40 |

30 |

80 |

|

T4 |

|

10° |

19 |

162.44 |

|

20.07 |

15.27 |

|

9.77 |

2.95 |

|

90.44 |

0.15 |

16.65 |

| 20 |

24 |

120 |

|

T5 |

|

2° |

8 |

161.32 |

|

14.55 |

10.01 |

|

8.15 |

3.33 |

|

90.02 |

-0.03 |

17.06 |

| 40 |

24 |

120 |

|

T6 |

|

7° |

10 |

164.95 |

|

16.13 |

11.78 |

|

7.88 |

3.91 |

|

87.51 |

1.05 |

24.22 |

| 20 |

30 |

120 |

|

T7 |

|

1° |

17 |

139.40 |

|

12.44 |

6.90 |

|

9.13 |

3.94 |

|

90.55 |

0.14 |

15.90 |

| 40 |

30 |

120 |

|

T8 |

|

8° |

19 |

142.14 |

|

17.75 |

12.33 |

|

6.57 |

5.15 |

|

88.93 |

0.13 |

20.02 |

| 30 |

27 |

100 |

|

T9 |

|

3° |

14 |

222.42 |

|

14.97 |

10.03 |

|

8.11 |

4.03 |

|

90.13 |

-0.15 |

17.11 |

| 30 |

27 |

100 |

|

T10 |

|

6° |

14 |

169.90 |

|

16.60 |

12.45 |

|

8.40 |

4.15 |

|

89.12 |

-0.17 |

18.92 |

| 30 |

27 |

100 |

|

T11 |

|

9° |

14 |

158.49 |

|

17.91 |

13.07 |

|

8.77 |

4.50 |

|

89.05 |

-0.25 |

18.67 |

| 30 |

27 |

100 |

|

T12 |

|

12° |

14 |

175.77 |

|

17.50 |

12.95 |

|

8.20 |

4.11 |

|

90.14 |

-0.17 |

17.29 |

Table 2.

Average of the noodles cooking tests and texture parameters.

Table 2.

Average of the noodles cooking tests and texture parameters.

| Treatment |

|

Cooking tests1

|

|

Texture parameters 2

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

Min |

% |

% |

% |

|

N |

Mm |

|

N |

N |

| T1 |

|

10 |

146.12 |

155.60 |

6.01 |

|

29.17 |

0.93 |

0.74 |

21.09 |

19.70 |

| T2 |

|

11 |

166.45 |

154.12 |

11.40 |

|

14.04 |

0.88 |

0.73 |

10.17 |

9.54 |

| T3 |

|

10 |

152.21 |

160.02 |

10.15 |

|

19.50 |

1.09 |

0.79 |

15.64 |

14.09 |

| T4 |

|

10 |

173.40 |

205.04 |

8.02 |

|

9.21 |

2.30 |

0.80 |

7.12 |

9.21 |

| T5 |

|

9 |

144.47 |

151.99 |

7.15 |

|

4.56 |

2.05 |

0.75 |

3.45 |

4.49 |

| T6 |

|

9 |

148.16 |

152.40 |

7.50 |

|

6.51 |

2.02 |

0.73 |

5.52 |

5.20 |

| T7 |

|

9 |

140.70 |

147.07 |

9.22 |

|

20.15 |

0.94 |

0.75 |

15.13 |

13.67 |

| T8 |

|

9 |

139.56 |

160.44 |

5.11 |

|

14.11 |

1.07 |

0.84 |

11.47 |

11.19 |

| T9 |

|

9 |

169.90 |

191.59 |

8.09 |

|

4.12 |

2.22 |

0.77 |

3.02 |

3.11 |

| T10 |

|

10 |

156.12 |

175.28 |

9.26 |

|

5.70 |

0.95 |

0.71 |

3.15 |

3.02 |

| T11 |

|

10 |

157.31 |

176.36 |

7.44 |

|

5.11 |

2.21 |

0.79 |

4.17 |

4.14 |

| T12 |

|

10 |

142.02 |

152.55 |

9.25 |

|

18.52 |

0.89 |

0.71 |

12.08 |

10.04 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).