Submitted:

13 June 2025

Posted:

16 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Framework

Portuguese Political Context and Partisanship

Electoral Manifestos

Partisanship and SDGs

3. Materials and Methods

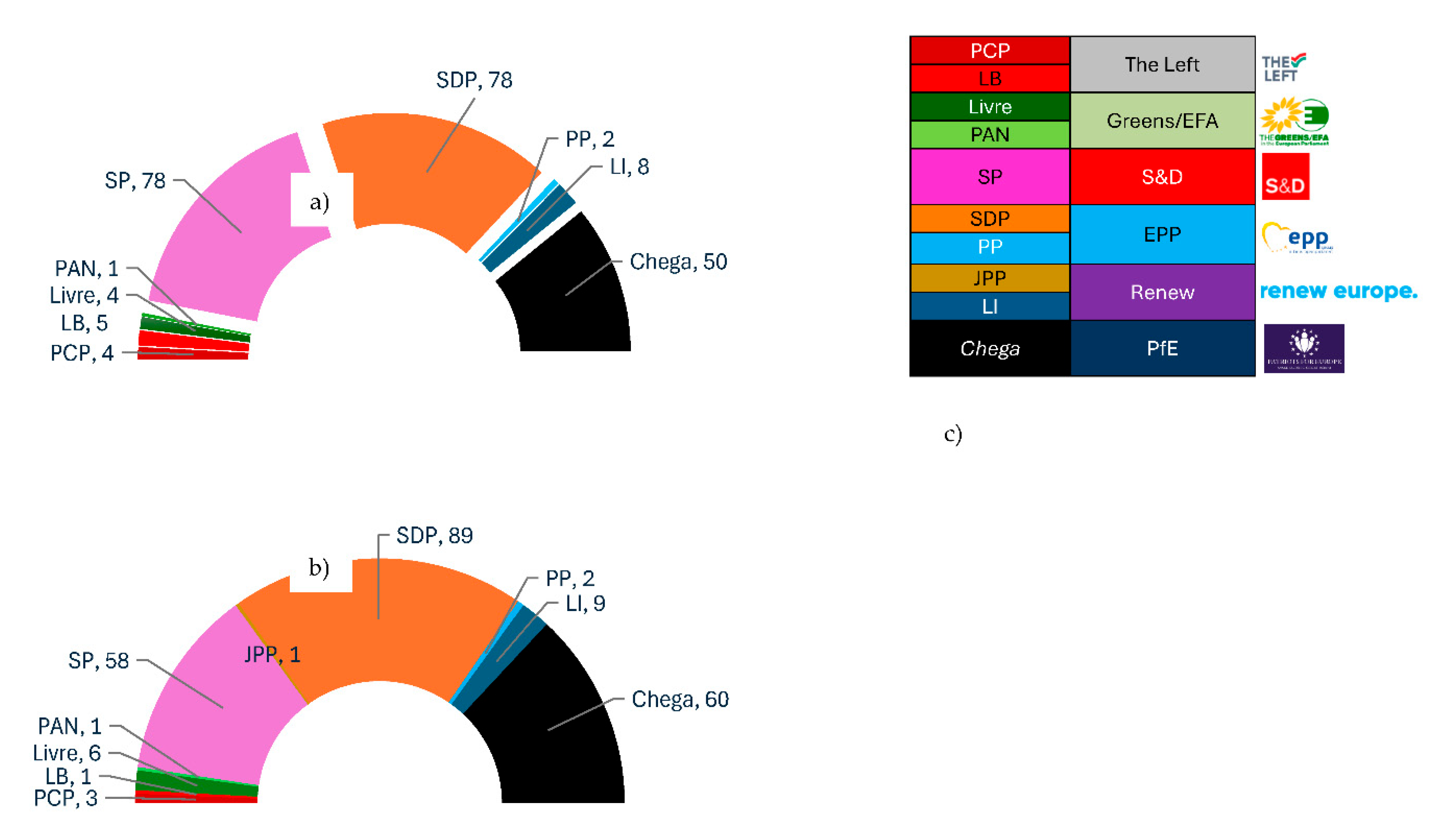

3.1. Sample and Research Design

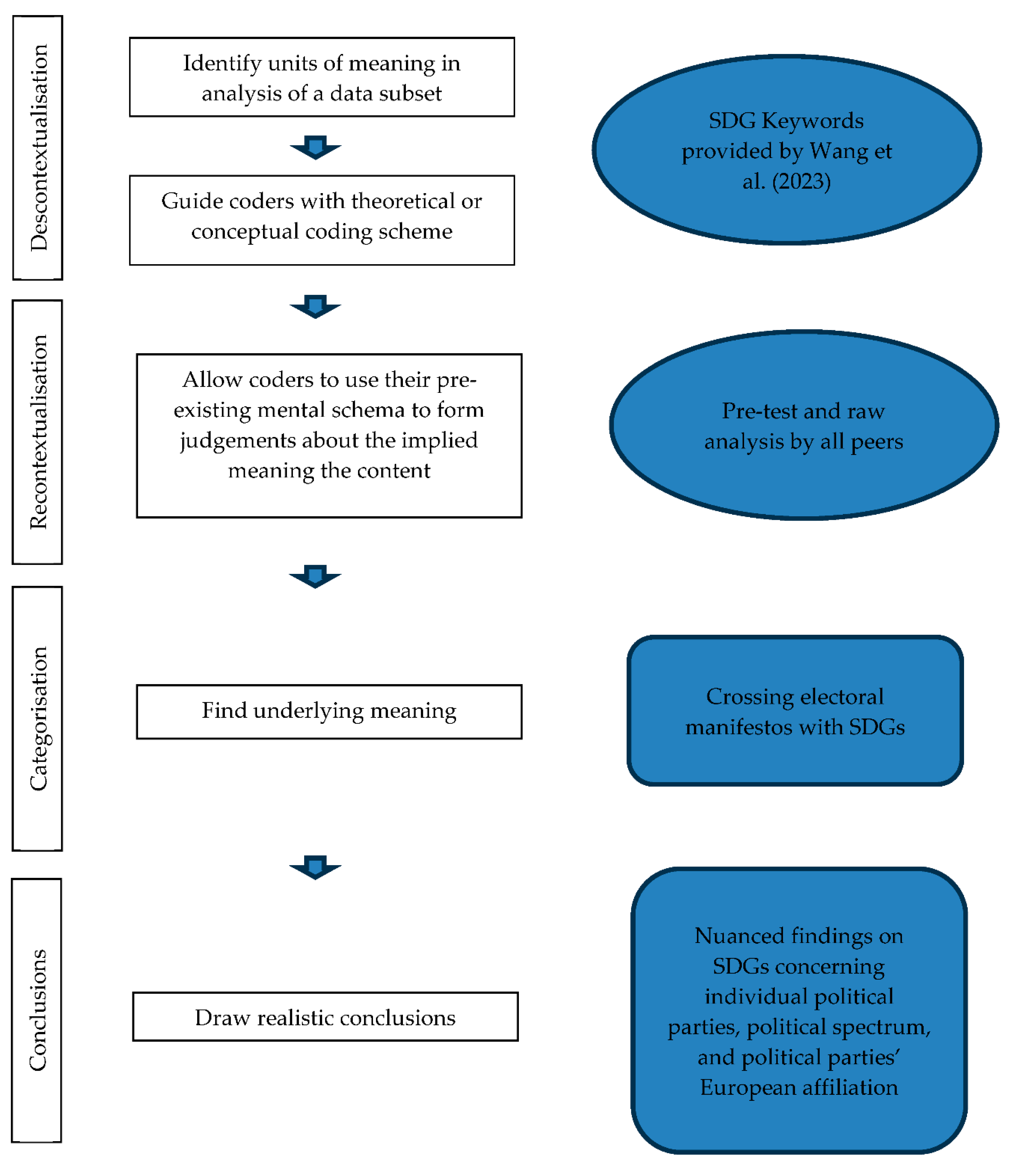

3.2. Coding Scheme

3.3. Data Analysis and Procedures

4. Results

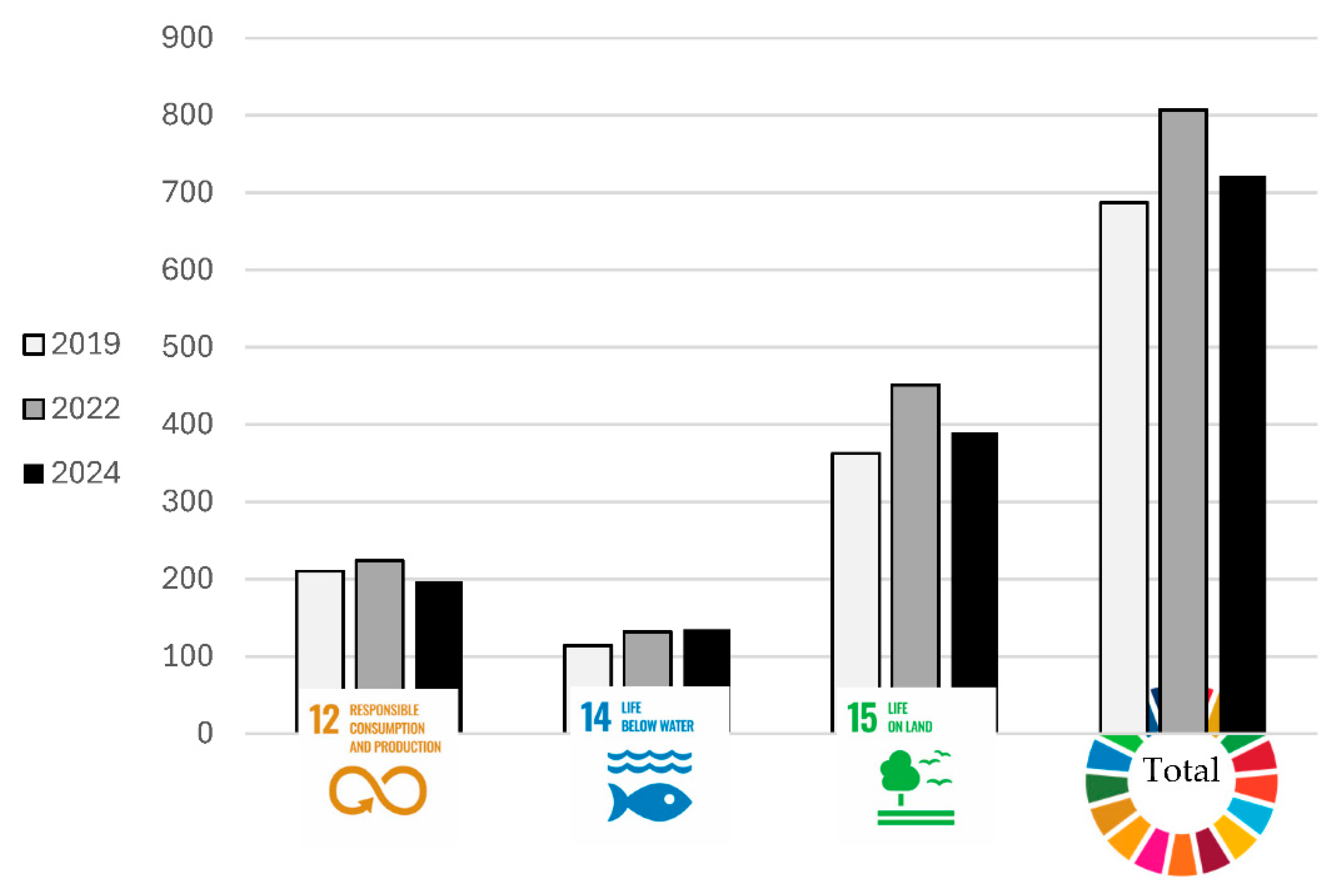

4.1. Aggregate Results

4.2. Micro and Grouped Results

4.2.1. Individual Political Parties

- -

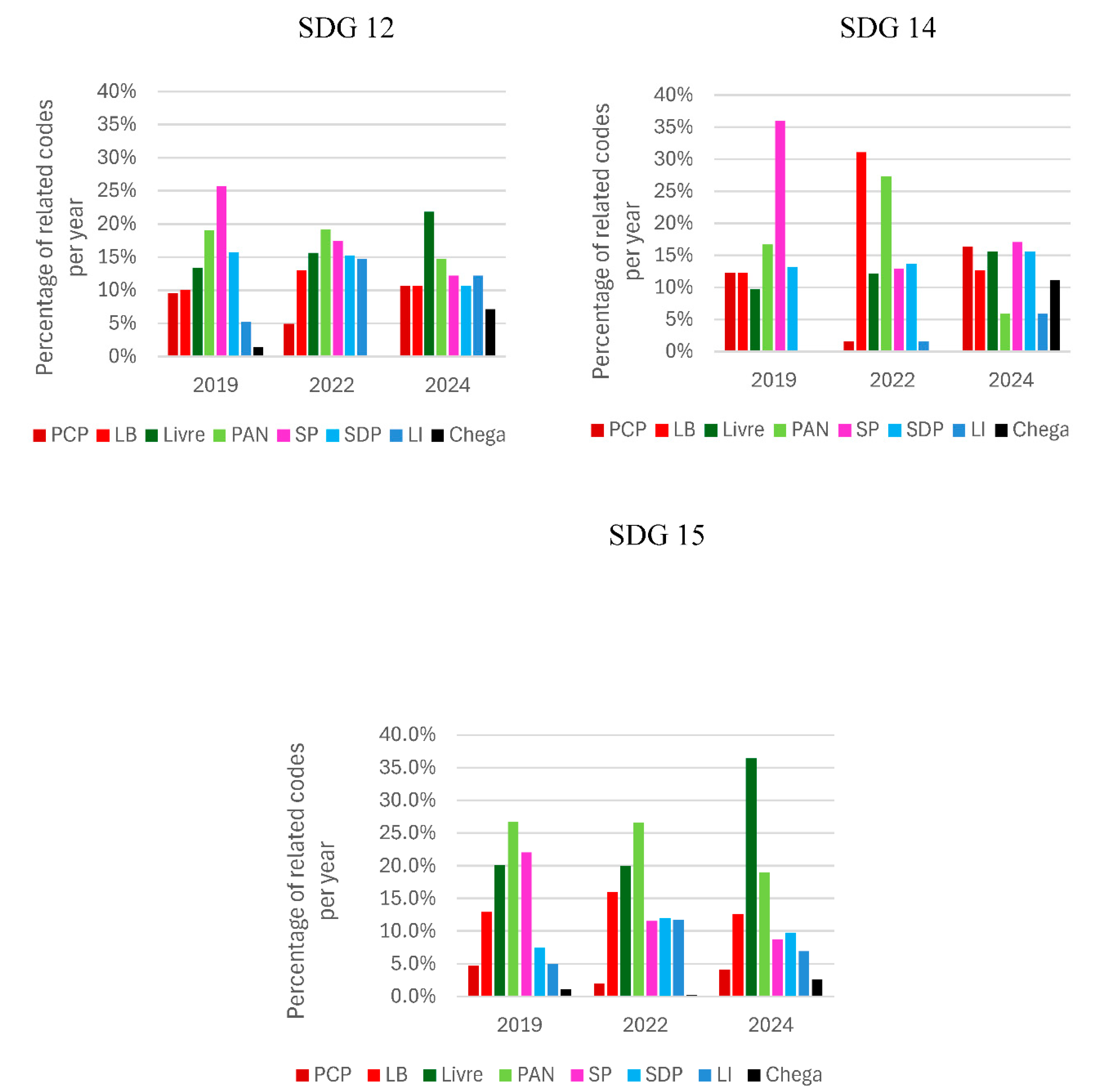

- Livre is the only party showing consistent growth in all SDG-related code frequency across all elections;

- -

- Chega exhibited minimal or no SDG-related codes in 2019 and 2022 but showed an increase for SDG 15 and expressive increases for SDGs 12 and 14 in 2024, albeit still at relatively low frequencies;

- -

- PAN, despite high SDG-related code frequencies (particularly for SDGs 12 and 15) in 2024, recorded fewer codes across all SDGs compared to 2019;

- -

- SP showed a decrease in SDG-related codes from 2019 to 2024 across all SDGs, with a significant downward trend over the three election periods. However, it led in SDG 14 code frequency in 2024;

- -

- SDP demonstrated the most stable frequency of codes across all SDGs, closely aligning with the average number of frequency codes;

- -

- LB exhibited a concave trend, peaking in code frequency for all SDGs in 2022. A decreasing pattern was noted for SDG 12 in 2024, while SDGs 14 and 15 remained stable when comparing 2019 to 2024;

- -

- LI is characterized by relatively high frequency coding in SDG 12, contrasting with low frequencies in SDGs 14 and 15, rather than showing a clear trend;

- -

- PCP displayed a convex trend, with lower frequency codes across all SDGs in 2022, but recovered to or exceeded 2019 levels in 2024 (particularly for SDG 14).

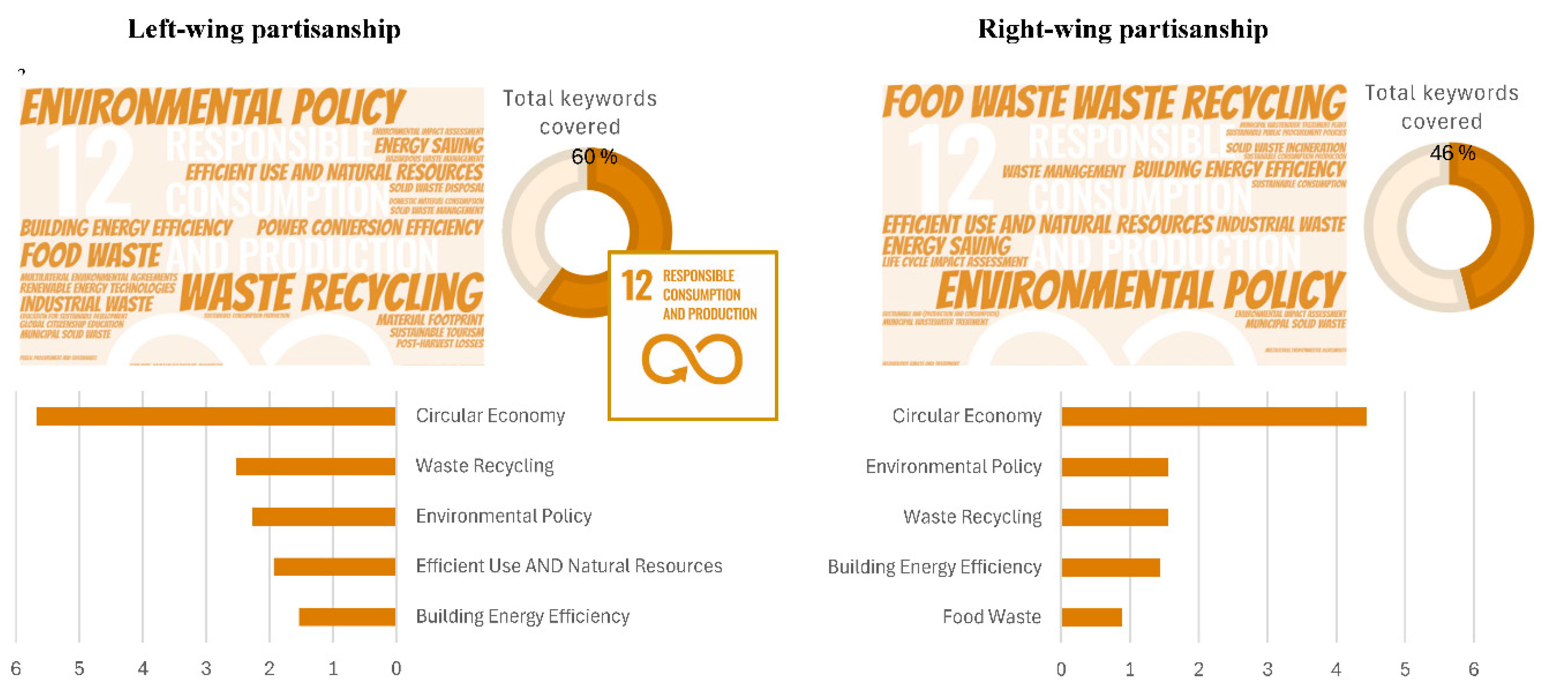

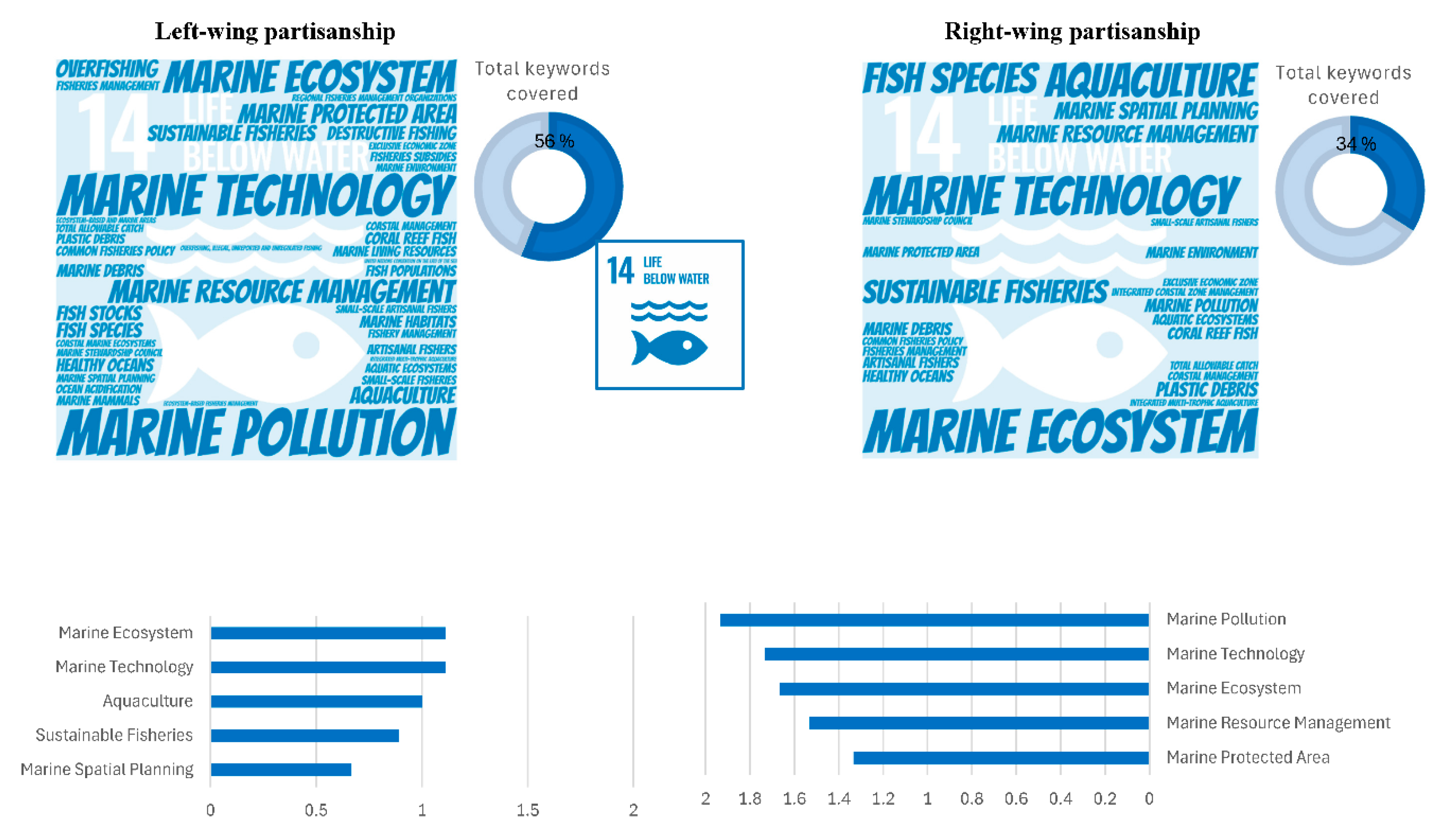

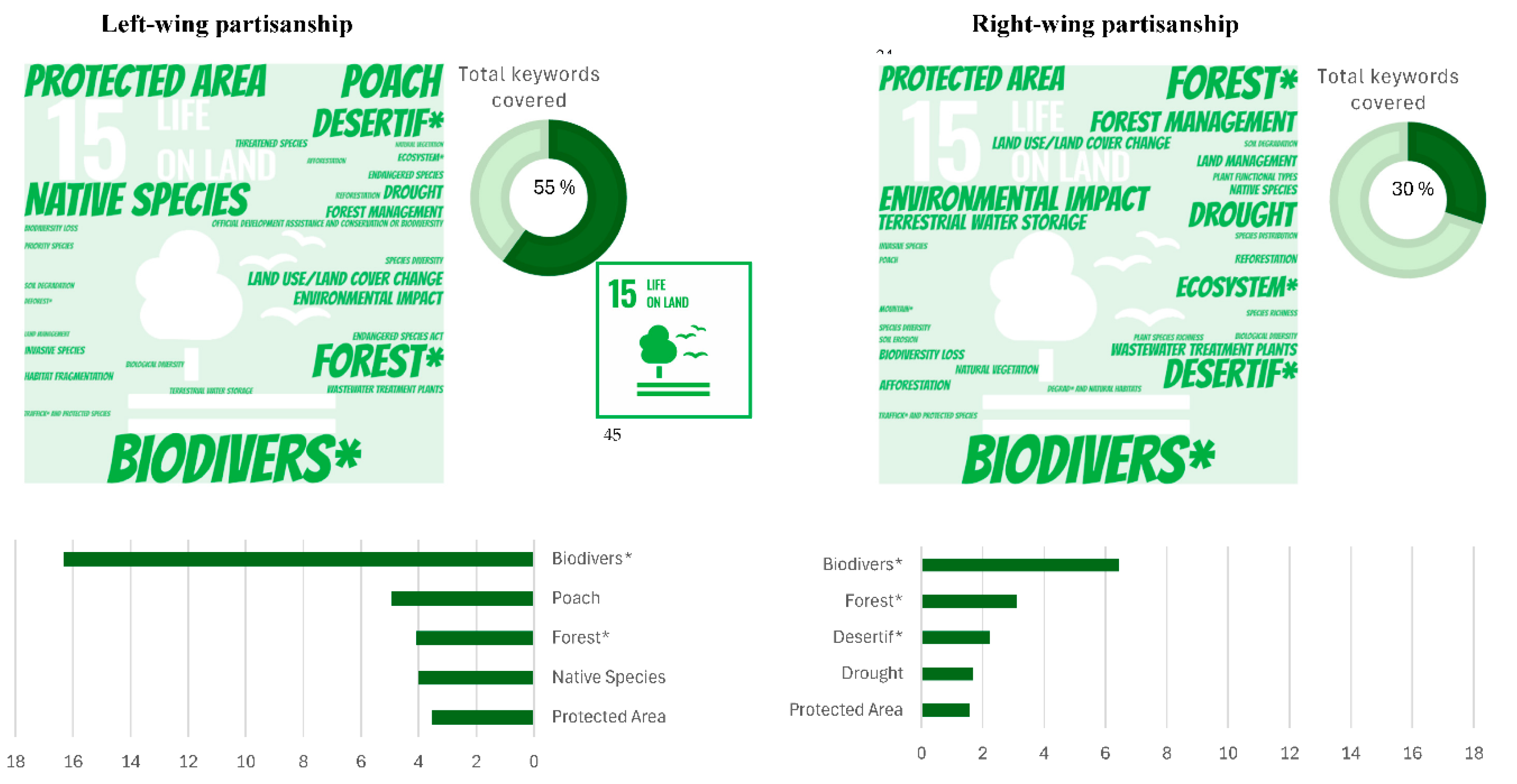

4.2.2. Position on the Political Spectrum

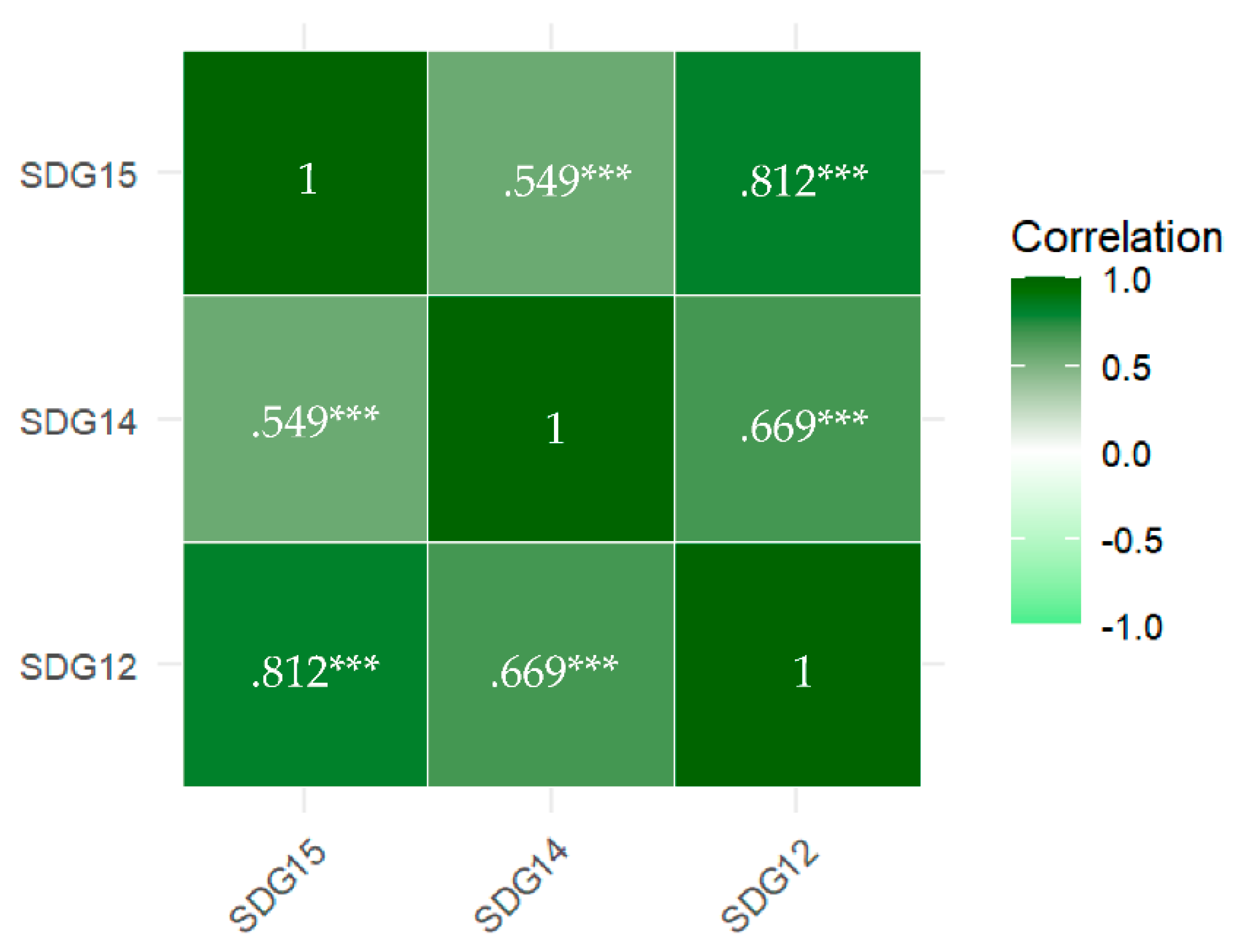

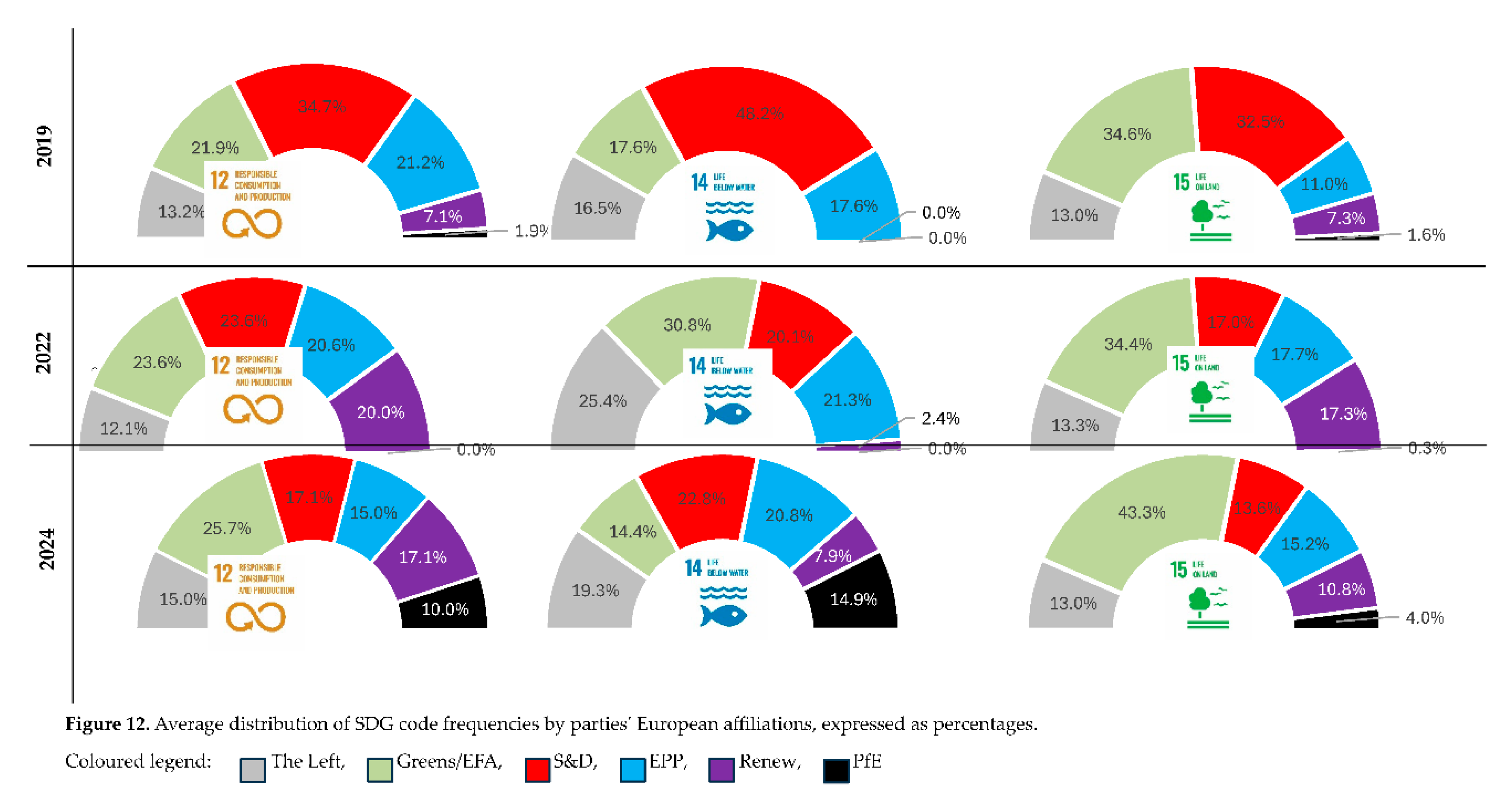

4.2.3. Portuguese Political Parties’ European Affiliation

Discussion

Practical Implications

Concluding Remarks

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| SDG(s) | Sustainable Development Goal(s) |

| SDG 12 | Sustainable Development Goal 12 of the United Nations 2030 Agenda, titled “Ensure sustainable consumption and production patterns.” |

| SDG 14 | Sustainable Development Goal 14 of the United Nations 2030 Agenda, titled “Conserve and sustainably use the oceans, seas and marine resources for sustainable development.” |

| SDG 15 | Sustainable Development Goal 15 of the United Nations 2030 Agenda, titled “Protect, restore and promote sustainable use of terrestrial ecosystems, sustainably manage forests, combat desertification, and halt and reverse land degradation and halt biodiversity loss.” |

Appendix A

| SDG 12 Keywords | UoA Text-Mining Results (global publications) | UN SDG Targets and Indicators |

|---|---|---|

| Building Energy Efficiency | Y | |

| Circular Economy | Y | |

| Combined Heat and Power | Y | |

| Education for Sustainable Development | Y | |

| Energy Efficiency Buildings | Y | |

| Energy Saving | Y | |

| Environmental Impact Assessment | Y | |

| Environmental Impact Categories | Y | |

| Environmental Life Cycle Assessment | Y | |

| Environmental Policy | Y | |

| Environmental Technology | Y | |

| Food Waste | Y | Y |

| Green Supply Chain Management | Y | |

| Hazardous Chemicals | Y | |

| Hazardous Waste | Y | Y |

| Hazardous Waste Management | Y | |

| Heavy Metal AND Pollut* | Y | |

| Heavy Metal Pollution | Y | |

| Household Food Waste | Y | |

| Hydraulic Retention Time | Y | |

| Industrial Waste | Y | |

| Integrated Solid Waste Management | Y | |

| Life Cycle Energy Analysis | Y | |

| Life Cycle Impact Assessment | Y | |

| Low Carbon Economy | Y | |

| Lowcarbon Economy | Y | |

| Material Flow Analysis | Y | |

| Municipal Solid Waste | Y | |

| Municipal Solid Waste | Y | |

| Municipal Solid Waste Generation | Y | |

| Municipal Solid Waste Incineration | Y | |

| Municipal Solid Waste Management | Y | |

| Municipal Wastewater Treatment | Y | |

| Municipal Wastewater Treatment Plant | Y | |

| Organic Fraction of Municipal Solid Waste | Y | |

| Persistent Organic Pollutants | Y | |

| Phase Change Materials | Y | |

| Potential Environmental Impacts | Y | |

| Power Conversion Efficiency | Y | |

| Renewable Energy Technologies | Y | |

| Sewage Sludge | Y | |

| Solid Waste | Y | |

| Solid Waste Disposal | Y | |

| Solid Waste Generation | Y | |

| Solid Waste Incineration | Y | |

| Solid Waste Management | Y | |

| Solid Waste Management System | Y | |

| Sustainable AND (Production AND Consumption) | Y | |

| Sustainable Consumption | Y | Y |

| Sustainable Consumption Production | Y | |

| Sustainable Production | Y | Y |

| Sustainable Supply Chain | Y | |

| Sustainable Tourism | Y | Y |

| Sustainable Tourism Development | Y | |

| The Resource Conservation Recovery Act | Y | |

| Volatile Fatty Acid | Y | |

| Waste Management | Y | |

| Waste Management System | Y | |

| Waste Recycling | Y | |

| Waste Treatment | Y | |

| Wastewater Treatment | Y | |

| Wastewater Treatment Plant | Y | |

| Water Pollutants AND Chemical | Y | |

| Domestic Material Consumption | Y | |

| Efficient Use AND Natural Resources | Y | |

| Food Loss Index | Y | |

| Food Waste Index | Y | |

| Fossil-Fuel Subsidies | Y | |

| Global Citizenship Education | Y | |

| Global Food Waste | Y | |

| Hazardous Waste AND Treatment | Y | |

| Material Footprint | Y | |

| Multilateral Environmental Agreements | Y | |

| National Recycling Rate | Y | |

| Post-Harvest Losses | Y | |

| Public Procurement AND Sustainable | Y | |

| Renewable Energy-Generating | Y | |

| Sustainable Consumption Patterns | Y | |

| Sustainable Development AND Education | Y | |

| Sustainable Production Patterns | Y | |

| Sustainable Public Procurement Policies | Y | |

| The 10-Year Framework of Programmes on Sustainable Consumption and Production Patterns | Y | |

| Waste Generation | Y |

| SDG 14 Keywords | UoA Text-Mining Results (global publications) | UN SDG Targets and Indicators |

|---|---|---|

| Aquatic Ecosystems | Y | |

| Aquatic Food Webs | Y | |

| Baltic Sea Action Plan | Y | |

| Coastal Environment | Y | |

| Coastal Habitat | Y | |

| Coastal Management | Y | |

| Coastal Marine Ecosystems | Y | |

| Common Fisheries Policy | Y | |

| Convention for The Conservation of Antarctic Marine Living Resources | Y | |

| Coral Bleach | Y | |

| Coral Reef | Y | |

| Coral Reef Ecosystem | Y | |

| Coral Reef Fish | Y | |

| Ecosystem-Based Fisheries Management | Y | |

| Exclusive Economic Zone | Y | |

| Fish Populations | Y | |

| Fish Species | Y | |

| Fish Stocks | Y | |

| Fisheries Management | Y | |

| Fishery Management | Y | |

| Fishing Effort | Y | |

| Fishing Pressure | Y | |

| Great Barrier Reef | Y | |

| Harmful Algal Bloom | Y | |

| Integrated Coastal Zone Management | Y | |

| Integrated Multi-Trophic Aquaculture | Y | |

| Large Marine Ecosystem | Y | |

| Marine | Y | |

| Marine Ecosystem | Y | |

| Marine Environment | Y | |

| Marine Fish | Y | |

| Marine Food Web | Y | |

| Marine Habitats | Y | |

| Marine Life | Y | |

| Marine Mammals | Y | |

| Marine Organisms | Y | |

| Marine Protected Area | Y | |

| Marine Protected Area | Y | |

| Marine Resource Management | Y | |

| Marine Spatial Planning | Y | |

| Marine Species | Y | |

| Marine Stewardship Council | Y | |

| No-Take Marine Protected Area | Y | |

| No-Take Marine Reserve | Y | |

| Ocean Acidification | Y | Y |

| Plastic Debris | Y | |

| Regional Fisheries Management Organizations | Y | |

| Seagrass Bed | Y | |

| Species Richness | Y | |

| The Marine Strategy Framework Directive | Y | |

| Total Allowable Catch | Y | |

| United Nations Convention on The Law of The Sea | Y | Y |

| Aquaculture | Y | |

| Artisanal Fishers | Y | |

| Coastal Areas | Y | |

| Coastal Eutrophication | Y | |

| Destructive Fishing | Y | |

| Ecosystem-Based AND Marine Areas | Y | |

| Fisheries Subsidies | Y | |

| Healthy Oceans | Y | |

| Intergovernmental Oceanographic Commission Criteria and Guidelines on the Transfer of Marine Technology | Y | |

| Marine Acidity | Y | |

| Marine Debris | Y | |

| Marine Pollution | Y | |

| Marine Technology | Y | |

| Nutrient Pollution | Y | |

| Overfishing | Y | |

| Overfishing, Illegal, Unreported and Unregulated Fishing | Y | |

| Plastic Density Debris | Y | |

| Productive Oceans | Y | |

| Small-Scale Artisanal Fishers | Y | |

| Small-Scale Fisheries | Y | |

| Sustainable Fisheries | Y |

| SDG 15 Keywords | UoA Text-Mining Results (global publications) | UN SDG Targets and Indicators |

|---|---|---|

| Biodivers* | Y | Y |

| Biodiversity Loss | Y | |

| Biological Diversity | Y | |

| Corine Land Cover | Y | |

| Deforest* | Y | Y |

| Desertif* | Y | Y |

| Dry Season | Y | |

| Dryland* | Y | Y |

| Earth System Model | Y | |

| Ecosystem Function | Y | |

| Ecosystem Service | Y | |

| Ecosystem* | Y | Y |

| Endangered Species | Y | |

| Endangered Species Act | Y | |

| Enhanced Vegetation Index | Y | |

| Environmental Change | Y | |

| Environmental Factor | Y | |

| Environmental Impact | Y | |

| Eu Water Framework Directive | Y | |

| Fire-Fallow Cultivation | Y | |

| Forest Cover | Y | |

| Forest Degradation | Y | |

| Forest Ecosystem | Y | |

| Forest Management | Y | |

| Gross Primary Production | Y | |

| Habitat Fragmentation | Y | |

| Invasive Species | Y | |

| Iucn Red List | Y | |

| Land Cover Change | Y | |

| Land Cover Type | Y | |

| Land Data Assimilation System | Y | |

| Land Degradation | Y | |

| Land Degradation Neutrality | Y | |

| Land Management | Y | |

| Land Use and Land Cover | Y | |

| Land Use/Land Cover Change | Y | |

| Leaf Area Index | Y | |

| Low Impact Development | Y | |

| Mountain* | Y | Y |

| Native Species | Y | |

| Natural Vegetation | Y | |

| Net Ecosystem Exchange | Y | |

| Net Ecosystem Productivity | Y | |

| Normalized Difference Vegetation Index | Y | |

| Palmer Drought Severity Index | Y | |

| Plant Functional Types | Y | |

| Plant Species | Y | |

| Plant Species Richness | Y | |

| Protected Area | Y | |

| Revised Universal Soil Loss Equation | Y | |

| Soil & Water Assessment Tool | Y | |

| Soil and Water Assessment Tool | Y | |

| Soil Degradation | Y | |

| Soil Erosion | Y | |

| Soil Quality | Y | |

| Soil Quality Index | Y | |

| Soil Water Content | Y | |

| Species Distribution | Y | |

| Species Diversity | Y | |

| Species Richness | Y | |

| Terrestrial Ecosystem | Y | |

| Terrestrial Water Storage | Y | |

| Threatened Species | Y | Y |

| Topographic Wetness Index | Y | |

| Trophic Web | Y | |

| Tropical Forests | Y | |

| Tropical Rainfall Measuring Mission | Y | |

| Universal Soil Loss Equation | Y | |

| Vegetation Types | Y | |

| Wastewater Treatment Plants | Y | |

| Wetland | Y | Y |

| Wetland Ecosystem | Y | |

| Wetland* | Y | Y |

| Wetlands | Y | Y |

| Yellow River Delta | Y | |

| Afforestation | Y | |

| Aichi Biodiversity Target 2 | Y | |

| Degrad* AND Natural Habitats | Y | |

| Degraded Forests | Y | |

| Degraded Land | Y | |

| Degraded Soil | Y | |

| Drought | Y | |

| Freshwater Biodiversity | Y | |

| Genetic Resources | Y | |

| Illegal Wildlife Products | Y | |

| Inland Freshwater Ecosystems | Y | |

| Invasive Alien Species | Y | |

| Mountain Biodiversity | Y | |

| Mountain Ecosystems | Y | |

| Mountain Green Cover Index | Y | |

| Official Development Assistance AND Conservation OR Biodiversity | Y | |

| Poach* | Y | |

| Poach* AND Protected Species | Y | |

| Priority Species | Y | |

| Red List Index | Y | |

| Reforestation | Y | |

| Strategic Plan for Biodiversity 2011–2020 | Y | |

| System of Environmental-Economic Accounting | Y | |

| Terrestrial Biodiversity | Y | |

| Terrestrial Freshwater Ecosystems | Y | |

| Traffick* AND Protected Species | Y |

| SDGs | Doornik-Hansen test | Shapiro-Wilk test | Lilliefors Test |

Jarque-Bera Test |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SDG 12 | .318 (p-value = .853) |

.984 (p-value = .957) |

.107 (p-value = .670) |

.122 (p-value = .941) |

| SDG 14 | 2.094 (p-value = .351) |

.913 (p-value =.041) |

.145 (p-value = .200) |

1.574 (p-value = .455) |

| SDG 15 | 3.156 (p-value = .206) |

.940 (p-value = .165) |

.126 (p-value = .410) |

2.096 (p-value = .351) |

| Left-wing parties <----------------> Right-wing parties | |||||||||

| SDGs per year | PCP | LB | Livre | PAN | SP | SDP | LI | Chega | Grand Total |

| 2019 | 51 | 82 | 112 | 156 | 175 | 75 | 29 | 7 | 687 |

| SDG 12 | 20 | 21 | 28 | 40 | 54 | 33 | 11 | 3 | 210 |

| SDG 14 | 14 | 14 | 11 | 19 | 41 | 15 | 0 | 0 | 114 |

| SDG 15 | 17 | 47 | 73 | 97 | 80 | 27 | 18 | 4 | 363 |

| 2022 | 22 | 142 | 141 | 199 | 108 | 106 | 88 | 1 | 807 |

| SDG 12 | 11 | 29 | 35 | 43 | 39 | 34 | 33 | 0 | 224 |

| SDG 14 | 2 | 41 | 16 | 36 | 17 | 18 | 2 | 0 | 132 |

| SDG 15 | 9 | 72 | 90 | 120 | 52 | 54 | 53 | 1 | 451 |

| 2024 | 59 | 87 | 206 | 111 | 81 | 80 | 59 | 39 | 722 |

| SDG 12 | 21 | 21 | 43 | 29 | 24 | 21 | 24 | 14 | 197 |

| SDG 14 | 22 | 17 | 21 | 8 | 23 | 21 | 8 | 15 | 135 |

| SDG 15 | 16 | 49 | 142 | 74 | 34 | 38 | 27 | 10 | 390 |

| Grand Total | 132 | 311 | 459 | 466 | 364 | 261 | 176 | 47 | 2216 |

| SDGs | Groups | Sum of squares | df | Mean square | F | p | Eta squared |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SDG 12 | Between groups | 45.583 | 2 | 22.792 | 0.123 | 0.8848 | 0.012 |

| Within groups | 3,887.375 | 21 | 185.113 | ||||

| Total | 3,932.958 | 23 | |||||

| SDG 14 | Between groups | 32.250 | 2 | 16.125 | 0.110 | 0.8967 | 0.010 |

| Within groups | 3,090.375 | 21 | 147.161 | ||||

| Total | 3,122.625 | 23 | |||||

| SDG 15 | Between groups | 508.083 | 2 | 254.042 | 0.168 | 0.8460 | 0.016 |

| Within groups | 31,717.25 | 21 | 1,510.345 | ||||

| Total | 32,225.33 | 23 |

| SDG 12 Keywords | Left-wing | Right-wing |

| Building Energy Efficiency | 1.533333 | 1.444444 |

| Circular Economy | 5.666667 | 4.444444 |

| Domestic Material Consumption | 0.066667 | 0 |

| Education for Sustainable Development | 0.4 | 0 |

| Efficient Use AND Natural Resources | 1.933333 | 0.777778 |

| Energy Efficiency Buildings | 0.133333 | 0 |

| Energy Saving | 0.666667 | 0.555556 |

| Environmental Impact Assessment | 0.333333 | 0.222222 |

| Environmental Policy | 2.266667 | 1.555556 |

| Environmental Technology | 0.2 | 0 |

| Food Waste | 0.733333 | 0.888889 |

| Global Citizenship Education | 0.2 | 0 |

| Green Supply Chain Management | 0.066667 | 0 |

| Hazardous Waste AND Treatment | 0.4 | 0.222222 |

| Hazardous Waste Management | 0.2 | 0.666667 |

| Heavy Metal Pollution | 0 | 0.111111 |

| Industrial Waste | 0.733333 | 0.333333 |

| Life Cycle Impact Assessment | 0.4 | 0.333333 |

| Low Carbon Economy | 1.133333 | 0.666667 |

| Material Footprint | 0.466667 | 0.111111 |

| Multilateral Environmental Agreements | 0.6 | 0.111111 |

| Municipal Solid Waste | 0.066667 | 0.111111 |

| Municipal Solid Waste Management | 0.133333 | 0.111111 |

| Municipal Wastewater Treatment | 0.066667 | 0.111111 |

| Municipal Wastewater Treatment Plant | 0 | 0.111111 |

| National Recycling Rate | 0.4 | 0 |

| Organic Fraction of Municipal Solid Waste | 0.6 | 0 |

| Persistent Organic Pollutants | 0.066667 | 0 |

| Phase Change Materials | 0.866667 | 0.111111 |

| Post-Harvest Losses | 0.066667 | 0 |

| Potential Environmental Impacts | 0.2 | 0.111111 |

| Power Conversion Efficiency | 1.066667 | 0.333333 |

| Public Procurement AND Sustainable | 0.533333 | 0.222222 |

| Renewable Energy Technologies | 0.8 | 0.333333 |

| Renewable Energy-Generating | 0.933333 | 0.555556 |

| Solid Waste Disposal | 0.066667 | 0 |

| Solid Waste Incineration | 0.466667 | 0.222222 |

| Solid Waste Management | 0.066667 | 0.222222 |

| Solid Waste Management System | 0.066667 | 0.111111 |

| Sustainable AND (Production AND Consumption) | 0.6 | 0.222222 |

| Sustainable Consumption | 0.066667 | 0.111111 |

| Sustainable Consumption Patterns | 0.466667 | 0 |

| Sustainable Consumption Production | 0.066667 | 0.111111 |

| Sustainable Development AND Education | 0.066667 | 0 |

| Sustainable Production | 1.066667 | 0.777778 |

| Sustainable Public Procurement Policies | 0 | 0.222222 |

| Sustainable Supply Chain | 0.2 | 0.222222 |

| Sustainable Tourism | 0.2 | 0.111111 |

| Waste Management | 0.266667 | 0.555556 |

| Waste Management System | 0.066667 | 0 |

| Waste Recycling | 2.533333 | 1.555556 |

| Waste Treatment | 0.2 | 0 |

| Wastewater Treatment | 0.133333 | 0.222222 |

| SDG 14 Keywords | Left-wing | Right-wing |

| Aquaculture | 1.200000 | 1.000000 |

| Aquatic Ecosystems | 0.266667 | 0.111111 |

| Artisanal Fishers | 0.200000 | 0.111111 |

| Coastal Management | 0.266667 | 0.111111 |

| Coastal Marine Ecosystems | 0.333333 | 0 |

| Common Fisheries Policy | 0.466667 | 0.111111 |

| Coral Reef Fish | 0.133333 | 0.111111 |

| Destructive Fishing | 0.733333 | 0 |

| Ecosystem-Based AND Marine Areas | 0.066667 | 0 |

| Ecosystem-Based Fisheries Management | 0.066667 | 0 |

| Exclusive Economic Zone | 0.066667 | 0.111111 |

| Fish Populations | 0.266667 | 0 |

| Fish Species | 0.333333 | 0.333333 |

| Fish Stocks | 0.133333 | 0 |

| Fisheries Management | 0.333333 | 0.111111 |

| Fisheries Subsidies | 0.133333 | 0 |

| Fishery Management | 0.333333 | 0 |

| Healthy Oceans | 0.400000 | 0.111111 |

| Integrated Coastal Zone Management | 0 | 0.333333 |

| Integrated Multi-Trophic Aquaculture | 0.066667 | 0.222222 |

| Marine Debris | 0.133333 | 0.111111 |

| Marine Ecosystem | 1.666667 | 1.111111 |

| Marine Environment | 0.066667 | 0.222222 |

| Marine Habitats | 0.600000 | 0 |

| Marine Living Resources | 0.733333 | 0 |

| Marine Mammals | 0.133333 | 0 |

| Marine Pollution | 1.933333 | 0.333333 |

| Marine Protected Area | 1.333333 | 0.222222 |

| Marine Resource Management | 1.533333 | 0.666667 |

| Marine Spatial Planning | 0.333333 | 0.666667 |

| Marine Stewardship Council | 0.133333 | 0.222222 |

| Marine Technology | 1.733333 | 1.111111 |

| Ocean Acidification | 0.266667 | 0 |

| Overfishing | 0.466667 | 0 |

| Overfishing, Illegal, Unreported and Unregulated Fishing | 0.266667 | 0 |

| Plastic Debris | 0.133333 | 0.222222 |

| Regional Fisheries Management Organizations | 0.400000 | 0 |

| Small-Scale Artisanal Fishers | 0.666667 | 0.111111 |

| Small-Scale Fisheries | 0.400000 | 0 |

| Sustainable Fisheries | 1.133333 | 0.888889 |

| Total Allowable Catch | 0.200000 | 0.111111 |

| United Nations Convention on The Law of The Sea | 0.066667 | 0 |

| SDG 15 Keywords | Left-wing | Right-wing |

| Afforestation | 0.53333 | 0.4444444 |

| Biodivers* | 16.3333 | 6.4444444 |

| Biodiversity Loss | 0.73333 | 0.4444444 |

| Biological Diversity | 0.66667 | 0.1111111 |

| Deforest* | 0.46667 | 0 |

| Degrad* AND Natural Habitats | 0 | 0.1111111 |

| Desertif* | 2.6 | 2.2222222 |

| Drought | 2.4 | 1.6666667 |

| Earth System Model | 0.26667 | 0 |

| Ecosystem Function | 0.26667 | 0 |

| Ecosystem* | 1.26667 | 1.2222222 |

| Endangered Species | 1.2 | 0 |

| Endangered Species Act | 1.06667 | 0 |

| Environmental Impact | 2.26667 | 1.5555556 |

| Forest Cover | 0.2 | 0 |

| Forest Ecosystem | 0.06667 | 0 |

| Forest Management | 2 | 1.3333333 |

| Forest* | 4.06667 | 3.1111111 |

| Freshwater Biodiversity | 0.06667 | 0 |

| Genetic Resources | 0.06667 | 0 |

| Habitat Fragmentation | 1.13333 | 0 |

| Invasive Alien Species | 0.06667 | 0 |

| Invasive Species | 1.06667 | 0.1111111 |

| Iucn Red List | 0.06667 | 0 |

| Land Degradation | 0.13333 | 0 |

| Land Management | 0.33333 | 0.5555556 |

| Land Use/Land Cover Change | 2.6 | 0.6666667 |

| Mountain* | 0 | 0.1111111 |

| Native Species | 4 | 0.4444444 |

| Natural Vegetation | 0.33333 | 0.3333333 |

| Official Development Assistance AND Conservation OR Biodiversity | 0.93333 | 0 |

| Plant Functional Types | 0.13333 | 0.2222222 |

| Plant Species | 0.06667 | 0 |

| Plant Species Richness | 0.33333 | 0.1111111 |

| Poach | 4.93333 | 0.1111111 |

| Poach AND Protected Species* | 0.06667 | 0 |

| Priority Species | 0.73333 | 0 |

| Protected Area | 3.53333 | 1.5555556 |

| Red List Index | 0.2 | 0 |

| Reforestation | 0.73333 | 0.3333333 |

| Soil Degradation | 0.66667 | 0.1111111 |

| Soil Erosion | 0.06667 | 0.1111111 |

| Soil Water Content | 0.06667 | 0 |

| Species Distribution | 0.06667 | 0.1111111 |

| Species Diversity | 0.93333 | 0.1111111 |

| Species Richness | 0.2 | 0.1111111 |

| Strategic Plan for Biodiversity 2011–2020 | 0.13333 | 0 |

| Terrestrial Biodiversity | 0.06667 | 0 |

| Terrestrial Ecosystem | 0.13333 | 0 |

| Terrestrial Freshwater Ecosystems | 0.2 | 0 |

| Terrestrial Water Storage | 0.73333 | 1.2222222 |

| Threatened Species | 1.4 | 0 |

| Traffick* AND Protected Species | 0.6 | 0.1111111 |

| Tropical Forests | 0.2 | 0 |

| Wastewater Treatment Plants | 1.2 | 0.6666667 |

| Wetland | 0.2 | 0 |

References

- Katila, P.; Colfer, C.J.P.; De Jong, W.; Galloway, G.; Pacheco, P.; Winkel, G. Sustainable development goals; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Merino-Saum, A.; Baldi, M.G.; Gunderson, I.; Oberle, B. Articulating natural resources and sustainable development goals through green economy indicators: A systematic analysis. Resources, Conservation and Recycling 2018, 139, 90–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reid, A.J.; Brooks, J.L.; Dolgova, L.; Laurich, B.; Sullivan, B.G.; Szekeres, P.; Wood, S.L.R.; Bennett, J.R.; Cooke, S.J. Post-2015 Sustainable Development Goals still neglecting their environmental roots in the Anthropocene. Environ. Sci. Policy 2017, 77, 179–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calicioglu, Ö.; Bogdanski, A. Linking the bioeconomy to the 2030 sustainable development agenda: Can SDG indicators be used to monitor progress towards a sustainable bioeconomy? N. Biotechnol. 2021, 61, 40–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cernev, T.; Fenner, R. The importance of achieving foundational Sustainable Development Goals in reducing global risk. Futures 2020, 115, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nilsson, M.; Griggs, D.; Visbeck, M. Policy: Map the interactions between Sustainable Development Goals. Nature 2016, 534, 320–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nill, J.; Kemp, R. Evolutionary approaches for sustainable innovation policies: From niche to paradigm? Res. Pol. 2009, 38, 668–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owen, A.L.; Videras, J. Trust, cooperation, and implementation of sustainability programs: The case of Local Agenda 21. Ecolog. Econ. 2008, 68, 259–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karlsson-Vinkhuyzen, S.I.; Groff, M.; Tamás, P.A.; Dahl, A.L.; Harder, M.; Hassall, G. Entry into force and then? The Paris agreement and state accountability. Climate Policy 2018, 18, 593–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bexell, M.; Jönsson, K. Realizing the 2030 Agenda for sustainable development – engaging national parliaments? Pol. Stud. 2022, 43, 621–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borghetto, E.; Belchior, A.M. Party Manifestos, Opposition and Media as Determinants of the Cabinet Agenda. Polit. Stud. 2019, 68, 37–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lafortune, G.; Fuller, G.; Kloke-Lesch, A.; Koundouri, P.; Riccaboni, A. Europe Sustainable Development Report 2023/2024; Dublin University Press: Dublin, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Firoiu, D.; Ionescu, G.H.; Pîrvu, R.; Bădîrcea, R.; Patrichi, I.C. Achievement of the sustainable development goals (SDG) in Portugal and forecast of key indicators until 2030. Technological and Economic Development of Economy 2022, 28, 1649–1683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marino, A.; Pariso, P. Comparing European countries’ performances in the transition towards the Circular Economy. ScTEn 2020, 729, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Almeida, M.A. The use of rural areas in Portugal: Historical perspective and the new trends. Revista Galega de Economía 2020, 29, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huber, L.M. Beyond Policy: The Use of Social Group Appeals in Party Communication. Political Communication 2022, 39, 293–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwörer, J.; Fernández-García, B. Religion on the rise again? A longitudinal analysis of religious dimensions in election manifestos of Western European parties. Party Politics 2020, 27, 1160–1171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swedberg, R. Exploratory research. In The production of knowledge: Enhancing progress in social science; Elman, C., Gerring, J., Mahoney, J., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, 2020; pp. 17–41. [Google Scholar]

- Huntington, S.P. The third wave. In Classes and Elites in Democracy and Democratization; Halevy, E.E., Ed.; Routledge: New York, 1991; Volume 199, pp. 285–292. [Google Scholar]

- Feijó, R.G. Presidents and Governments in Portugal: Variations on a Constitutional Theme (2008–2022). In Portugal Since the 2008 Economic Crisis; Pinto, A.C., Ed.; Routledge: London, 2023; pp. 90–109. [Google Scholar]

- Martins, A. Presidential Elements in Government The Portuguese Semi-Presidential System: About Law in the Books and Law in Action. European Constitutional Law Review 2006, 2, 81–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto, A.C.; de Almeida, P.T. Portugal: the primacy of ‘independents’. In The selection of ministers in Europe; Dowding, K., Dumont, P., Eds.; Routledge: London, 2008; pp. 147–158. [Google Scholar]

- Goes, E.; Leston-Bandeira, C. The role of the Portuguese parliament. In The Oxford handbook of Portuguese politics; Fernandes, J.M., Magalhães, P., Pinto, A.C., Eds.; Oxford Univesity Press: Oxford, 2022; pp. 136–148. [Google Scholar]

- Freire, A. The centre-left and the radical left in Portuguese democracy, 1974–2021. In The Oxford handbook of Portuguese politics; Fernandes, J.M., Magalhães, P.C., Pinto, A.C., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, 2022; pp. 88–101. [Google Scholar]

- Lopes, H.F. An unexpected Socialist majority: the 2022 Portuguese general elections. West European Politics 2022, 46, 437–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, J.M.; Magalhães, P.C. The 2019 Portuguese general elections. West European Politics 2020, 43, 1038–1050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eduardo, M.C.; Santos, M.H.; Teixeira, A.L. Gender and Politics: A Descriptive and Comparative Analysis of the Statutes of Brazilian and Portuguese Political Parties. Social Sciences 2023, 12, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campos, R.; Jatowt, A.; Jorge, A. Text Mining and Visualization of Political Party Programs Using Keyword Extraction Methods: The Case of Portuguese Legislative Elections; Information for a Better World: Normality, Virtuality, Physicality, Inclusivity, Cham, 2023; Sserwanga, I., Goulding, A., Moulaison-Sandy, H., Du, J.T., Soares, A.L., Hessami, V., Frank, R.D., Eds.; Springer Nature Switzerland: Cham, 2023; pp. 340–349. [Google Scholar]

- Santana-Pereira, J.; De Giorgi, E. ‘Your Luck is Our Luck’: Covid-19, the Radical Right and Low Polarisation in the 2022 Portuguese Elections. South European Society and Politics 2022, 27, 305–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lisi, M.; Freire, A. The selection of party leaders in Portugal. In The selection of political party leaders in contemporary parliamentary democracies; Pilet, J.-B., Cross, W., Eds.; Routledge: London, 2014; pp. 144–160. [Google Scholar]

- Marchi, R.; Alves, A.A. The right and far-right in the Portuguese democracy (1974–2022). In The Oxford handbook of Portuguese politics; Fernandes, J.M., Magalhães, P.C., Pinto, A.C., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, 2022; pp. 102–118. [Google Scholar]

- Lobo, M.C. Parties and Leader Effects: Impact of Leaders in the Vote for Different Types of Parties. Party Politics 2008, 14, 281–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garry, J.; Mansergh, L. Party manifestos. In How Ireland Voted 1997; Marsh, M., Ed.; Routledge, 1999; pp. 82–106. [Google Scholar]

- Holroyd, C. Technological innovation and building a ‘super smart’ society: Japan’s vision of society 5.0. Journal of Asian Public Policy 2022, 15, 18–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eder, N.; Jenny, M.; Müller, W.C. Manifesto functions: How party candidates view and use their party’s central policy document. Electoral Studies 2017, 45, 75–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Froio, C.; Bevan, S.; Jennings, W. Party mandates and the politics of attention: Party platforms, public priorities and the policy agenda in Britain. Party Politics 2016, 23, 692–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strøm, K. Minority government and majority rule; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Krauss, S.; Thürk, M. Stability of minority governments and the role of support agreements. West European Politics 2022, 45, 767–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moury, C.; Fernandes, J.M. Minority Governments and Pledge Fulfilment: Evidence from Portugal. Government and Opposition 2018, 53, 335–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belchior, A.M. The effects of party identification on perceptions of pledge fulfilment: Evidence from Portugal. International Political Science Review 2018, 40, 627–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Field, B.N. Minority Government Performance and Comparative Lessons. In Why Minority Governments Work: Multilevel Territorial Politics in Spain; Field, B.N., Ed.; Palgrave Macmillan US: New York, 2016; pp. 209–219. [Google Scholar]

- Thomson, R. Parties’ Election Manifestos and Public Policies. In The Oxford Handbook of Political Representation in Liberal Democracies; Rohrschneider, R., Thomassen, J., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, 2020; pp. 340–356. [Google Scholar]

- Brouard, S.; Grossman, E.; Guinaudeau, I.; Persico, S.; Froio, C. Do Party Manifestos Matter in Policy-Making? Capacities, Incentives and Outcomes of Electoral Programmes in France. Polit. Stud. 2018, 66, 903–921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, N. Greening the mainstream: party politics and the environment. Env. Polit. 2013, 22, 73–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundquist, S. Do Parties Matter for Environmental Policy Stringency? Exploring the Program-to-Policy Link for Environmental Issues in 28 Countries 1990–2015. Polit. Stud. 2022, 72, 612–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunes, W.; Anand, S. Paradox of Sustainable Development: Agenda of Political Parties. In Sustainable Development and India: Convergence of Law, Economics, Science, and Politics; Oxford University Press, 2018; pp. 116–133. [Google Scholar]

- Rakolobe, M. An Analysis of Gender Equality Provisions in Political Parties‘ Manifestos for Lesotho‘s 2022 General Elections. African Journal of Gender, Society and Development 2024, 13, 181–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmid, N. A comparative and dynamic analysis of political party positions on energy technologies. Environmental Innovation and Societal Transitions 2021, 39, 206–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farstad, F.M. What explains variation in parties’ climate change salience? Party Politics 2018, 24, 698–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, N.; Ladrech, R.; Little, C.; Tsagkroni, V. Political parties and climate policy: A new approach to measuring parties’ climate policy preferences. Party Politics 2017, 24, 731–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bendell, J. Replacing Sustainable Development: Potential Frameworks for International Cooperation in an Era of Increasing Crises and Disasters. Sustainability 2022, 14, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obersteiner, M.; Walsh, B.; Frank, S.; Havlík, P.; Cantele, M.; Liu, J.; Palazzo, A.; Herrero, M.; Lu, Y.; Mosnier, A.; Valin, H.; Riahi, K.; Kraxner, F.; Fritz, S.; van Vuuren, D. Assessing the land resource–food price nexus of the Sustainable Development Goals. Science Advances 2016, 2, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fonseca, L.M.; Domingues, J.P.; Dima, A.M. Mapping the Sustainable Development Goals Relationships. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Virto, L.R. A preliminary assessment of the indicators for Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 14 “Conserve and sustainably use the oceans, seas and marine resources for sustainable development”. Mar. Policy 2018, 98, 47–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pradhan, P.; Costa, L.; Rybski, D.; Lucht, W.; Kropp, J.P. A Systematic Study of Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) Interactions. Earth’s Future 2017, 5, 1169–1179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sénit, C.-A. Leaving no one behind? The influence of civil society participation on the Sustainable Development Goals. Environment and Planning C: Politics and Space 2019, 38, 693–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabizon, S. Women’s movements’ engagement in the SDGs: lessons learned from the Women’s Major Group. Gender & Development 2016, 24, 99–110. [Google Scholar]

- Hassan, M.M.; Lee, K.E.; Mokhtar, M. Mainstreaming, Institutionalizing and Translating Sustainable Development Goals into Non-governmental Organization’s Programs. In Concepts and Approaches for Sustainability Management; Lee, K.E., Ed.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2020; pp. 93–118. [Google Scholar]

- Harring, N.; Sohlberg, J. The varying effects of left–right ideology on support for the environment: Evidence from a Swedish survey experiment. Env. Polit. 2017, 26, 278–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Córdoba, P.-J.; Amor-Esteban, V.; Benito, B.; García-Sánchez, I.-M. The Commitment of Spanish Local Governments to Sustainable Development Goal 11 from a Multivariate Perspective. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bick, N.; Keele, D. Sustainability and climate change: Understanding the political use of environmental terms in municipal governments. Current Research in Environmental Sustainability 2022, 4, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeNicola, E.; Subramaniam, P.R. Environmental attitudes and political partisanship. Public Health 2014, 128, 404–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neumayer, E. The environment, left-wing political orientation and ecological economics. Ecolog. Econ. 2004, 51, 167–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noël, A.; Thérien, J.-P. Left and Right in Global Politics; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Blofield, M.; Ewig, C.; Piscopo, J.M. The Reactive Left: Gender Equality and the Latin American Pink Tide. Social Politics: International Studies in Gender, State & Society 2017, 24, 345–369. [Google Scholar]

- Harring, N.; Jagers, S.C. Should We Trust in Values? Explaining Public Support for Pro-Environmental Taxes. Sustainability 2013, 5, 210–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ejelöv, E.; Nilsson, A. Individual Factors Influencing Acceptability for Environmental Policies: A Review and Research Agenda. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sümeghy, D.; Schmeller, D. Giving the green light to sustainability: Key political factors behind the European Green Capital Award applications. J. Urban Affairs 2023, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lalot, F.; Büttner, C.M.; Özkeçeci, H.; Abrams, D. Right and left-wing views: A story of disagreement on environmental issues but agreement on solutions. Translational Issues in Psychological Science 2022, 8, 503–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.-J.; Feng, G.-F.; Chen, Y.E.; Wen, J.; Chang, C.-P. The impacts of government ideology on innovation: What are the main implications? Res. Pol. 2019, 48, 1232–1247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tawiah, V.; Zakari, A. Government political ideology and green innovation: evidence from OECD countries. Economic Change and Restructuring 2024, 57, 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohtar, R.H. The role of the private sector in sustainable development. Water International 2022, 47, 1023–1031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bisogno, M.; Cuadrado-Ballesteros, B.; Rossi, F.M.; Peña-Miguel, N. Sustainable development goals in public administrations: Enabling conditions in local governments. International Review of Administrative Sciences 2023, 89, 1223–1242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moilanen, M.; Østbye, S. Doublespeak? Sustainability in the Arctic—A Text Mining Analysis of Norwegian Parliamentary Speeches. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jordan, A.; Gravey, V. Environmental Policy in the EU: Actors, Institutions and Processes, 4th ed.; Routledge: London, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Kroll, C.; Zipperer, V. Sustainable Development and Populism. Ecolog. Econ. 2020, 176, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forchtner, B. The far right and the environment: Politics, discourse and communication; Routledge: Abingdon, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Forchtner, B.; Lubarda, B. Scepticisms and beyond? A comprehensive portrait of climate change communication by the far right in the European Parliament. Env. Polit. 2023, 32, 43–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krange, O.; Kaltenborn, B.P.; Hultman, M. Cool dudes in Norway: climate change denial among conservative Norwegian men. Environmental Sociology 2019, 5, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Painter, J.; Gavin, N.T. Climate Skepticism in British Newspapers, 2007–2011. Environmental Communication 2016, 10, 432–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Küppers, A. ‘Climate-Soviets,’ ‘Alarmism,’ and ‘Eco-Dictatorship’: The Framing of Climate Change Scepticism by the Populist Radical Right Alternative for Germany. German Politics 2024, 33, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lockwood, M. Right-wing populism and the climate change agenda: exploring the linkages. Env. Polit. 2018, 27, 712–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forchtner, B. Climate change and the far right. WIREs Climate Change 2019, 10, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bulli, G. Environmental Politics on the Italian Far Right: Not a party issue. In The Far Right and the Environment; Forchtner, B., Ed.; Routledge: London, 2019; pp. 88–103. [Google Scholar]

- Vicenova, R.; Oravcova, V.; Mišík, M. What Do Far-Right Parties Talk About When They Talk About Green Issues? ĽSNS in 2016–2020 Parliamentary Debates. Sociológia 2022, 54, 569–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ungureanu, C.; Sanjaume-Calvet, M. The blurred lines between center-right and far-right: “Reverse contamination” and the People’s Party’s environmentalism in Spain. Party Politics 2024, 1–14, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orellana, S.; Bisgin, H. Using Natural Language Processing to Analyze Political Party Manifestos from New Zealand. Information 2023, 14, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayring, P. Qualitative Content Analysis: Theoretical Background and Procedures. In Approaches to Qualitative Research in Mathematics Education: Examples of Methodology and Methods; Bikner-Ahsbahs, A., Knipping, C., Presmeg, N., Eds.; Springer Netherlands: Dordrecht, 2015; pp. 365–380. [Google Scholar]

- Kørnøv, L.; Lyhne, I.; Davila, J.G. Linking the UN SDGs and environmental assessment: Towards a conceptual framework. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2020, 85, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fereday, J.; Muir-Cochrane, E. Demonstrating Rigor Using Thematic Analysis: A Hybrid Approach of Inductive and Deductive Coding and Theme Development. International Journal of Qualitative Methods 2006, 5, 80–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, H.-F.; Shannon, S.E. Three Approaches to Qualitative Content Analysis. Qual. Health Res. 2005, 15, 1277–1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowell, L.S.; Norris, J.M.; White, D.E.; Moules, N.J. Thematic Analysis: Striving to Meet the Trustworthiness Criteria. International Journal of Qualitative Methods 2017, 16, 1609406917733847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleinheksel, A.J.; Rockich-Winston, N.; Tawfik, H.; Wyatt, T.R. Demystifying Content Analysis. American Journal of Pharmaceutical Education 2020, 84, 7113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Villiger, J.; Schweiger, S.A.; Baldauf, A. Making the Invisible Visible: Guidelines for the Coding Process in Meta-Analyses. Organizational Research Methods 2021, 25, 716–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonald, N.; Schoenebeck, S.; Forte, A. Reliability and Inter-rater Reliability in Qualitative Research: Norms and Guidelines for CSCW and HCI Practice. Proceedings of the ACM on Human-Computer Interaction 2019, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neuendorf, K.A. Content analysis and thematic analysis. In Advanced Research Methods for Applied Psychology; Brough, P., Ed.; Routledge: London, 2018; pp. 211–223. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, W.; Kang, W.; Mu, J. Mapping research to the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs); University of Auckland: Auckland, 2023; pp. 1–23. [Google Scholar]

- Erlingsson, C.; Brysiewicz, P. A hands-on guide to doing content analysis. African Journal of Emergency Medicine 2017, 7, 93–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krippendorff, K. Content Analysis: An Introduction to Its Methodology, 4th ed.; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, California, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- George, D.; Mallery, P. SPSS for Windows Step by Step: A Simple Guide and Reference, 17.0 update; Pearson: Boston, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Schober, P.; Boer, C.; Schwarte, L.A. Correlation Coefficients: Appropriate Use and Interpretation. Anesth. Analg. 2018, 126, 1763–1768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taglialatela, J.; Pirazzi Maffiola, K.; Barontini, R.; Testa, F. Board of Directors’ characteristics and environmental SDGs adoption: an international study. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management 2023, 30, 2490–2506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meuleman, L. Public Administration and Governance for the SDGs: Navigating between Change and Stability. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castellnou, M.; Guiomar, N.; Rego, F.; Fernandes, P. Fire growth patterns in the 2017 mega fire episode of October 15, central Portugal. In Advances in forest fire research; Viegas, X., Ed.; ADAI/CEIF University of Coimbra: Coimbra, 2018; pp. 447–453. [Google Scholar]

- Campos, C.; Couto, F.T.; Filippi, J.-B.; Baggio, R.; Salgado, R. Modelling pyro-convection phenomenon during a mega-fire event in Portugal. AtmRe 2023, 290, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camargo, J.; Castro, P. Portugal em Chamas - Como Resgatar as Florestas; Bertrand: Lisbon, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Ramos, A.M.; Russo, A.; DaCamara, C.C.; Nunes, S.; Sousa, P.; Soares, P.M.M.; Lima, M.M.; Hurduc, A.; Trigo, R.M. The compound event that triggered the destructive fires of October 2017 in Portugal. iScience 2023, 26, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pascual, U.; Balvanera, P.; Anderson, C.B.; Chaplin-Kramer, R.; Christie, M.; González-Jiménez, D.; Martin, A.; Raymond, C.M.; Termansen, M.; Vatn, A.; Athayde, S.; Baptiste, B.; Barton, D.N.; Jacobs, S.; Kelemen, E.; Kumar, R.; Lazos, E.; Mwampamba, T.H.; Nakangu, B.; O’Farrell, P.; Subramanian, S.M.; van Noordwijk, M.; Ahn, S.; Amaruzaman, S.; Amin, A.M.; Arias-Arévalo, P.; Arroyo-Robles, G.; Cantú-Fernández, M.; Castro, A.J.; Contreras, V.; De Vos, A.; Dendoncker, N.; Engel, S.; Eser, U.; Faith, D.P.; Filyushkina, A.; Ghazi, H.; Gómez-Baggethun, E.; Gould, R.K.; Guibrunet, L.; Gundimeda, H.; Hahn, T.; Harmáčková, Z.V.; Hernández-Blanco, M.; Horcea-Milcu, A.-I.; Huambachano, M.; Wicher, N.L.H.; Aydın, C.İ.; Islar, M.; Koessler, A.-K.; Kenter, J.O.; Kosmus, M.; Lee, H.; Leimona, B.; Lele, S.; Lenzi, D.; Lliso, B.; Mannetti, L.M.; Merçon, J.; Monroy-Sais, A.S.; Mukherjee, N.; Muraca, B.; Muradian, R.; Murali, R.; Nelson, S.H.; Nemogá-Soto, G.R.; Ngouhouo-Poufoun, J.; Niamir, A.; Nuesiri, E.; Nyumba, T.O.; Özkaynak, B.; Palomo, I.; Pandit, R.; Pawłowska-Mainville, A.; Porter-Bolland, L.; Quaas, M.; Rode, J.; Rozzi, R.; Sachdeva, S.; Samakov, A.; Schaafsma, M.; Sitas, N.; Ungar, P.; Yiu, E.; Yoshida, Y.; Zent, E. Diverse values of nature for sustainability. Nature 2023, 620, 813–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva, I.M.; Santos, C.; Guerreiro, J. Comparative analysis of National Ocean Strategies of the Atlantic Basin countries. Frontiers in Marine Science 2022, 9, 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Burke Thomas, A.; Cascio Wayne, E.; Costa Daniel, L.; Deener, K.; Fontaine Thomas, D.; Fulk Florence, A.; Jackson Laura, E.; Munns Wayne, R.; Orme-Zavaleta, J.; Slimak Michael, W.; Zartarian Valerie, G. Rethinking Environmental Protection: Meeting the Challenges of a Changing World. Environ. Health Perspect. 2017, 125, A43–A49. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Spoon, J.-J.; Hobolt, S.B.; de Vries, C.E. Going green: Explaining issue competition on the environment. Eur. J. Polit. Res. 2014, 53, 363–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rieiro-García, M.; Aibar-Guzmán, C.; Aibar-Guzmán, B. The 2030 Agenda in Spanish local entities: Does the government’s ideological color matter? Politics & Policy 2023, 51, 800–829. [Google Scholar]

- McKinley, E.; Acott, T.; Yates, K.L. Marine social sciences: Looking towards a sustainable future. Environ. Sci. Policy 2020, 108, 85–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Partelow, S.; von Wehrden, H.; Horn, O. Pollution exposure on marine protected areas: A global assessment. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2015, 100, 352–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gustavsson, M.; Morrissey, K. A typology of different perspectives on the spatial economic impacts of marine spatial planning. Journal of Environmental Policy & Planning 2019, 21, 841–853. [Google Scholar]

- Aswani, S.; Basurto, X.; Ferse, S.; Glaser, M.; Campbell, L.; Cinner, J.E.; Dalton, T.; Jenkins, L.D.; Miller, M.L.; Pollnac, R.; Vaccaro, I.; Christie, P. Marine resource management and conservation in the Anthropocene. Environ. Conserv. 2018, 45, 192–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffmann, S. Challenges and opportunities of area-based conservation in reaching biodiversity and sustainability goals. Biodivers. Conserv. 2022, 31, 325–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwilch, G.; Liniger, H.P.; Hurni, H. Sustainable Land Management (SLM) Practices in Drylands: How Do They Address Desertification Threats? Environ. Manage. 2014, 54, 983–1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgera, E. SDG 15: Protect, Restore and Promote Sustainable Use of Terrestrial Ecosystems, Sustainably Manage Forests, Combat Desertification, and Halt and Reverse Land Degradation and Halt Biodiversity Loss. In The Cambridge Handbook of the Sustainable Development Goals and International Law; Ebbesson, J., Hey, E., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, 2022; pp. 376–398. [Google Scholar]

- Seeberg, H.B. Opposition Policy Influence through Agenda-setting: The Environment in Denmark, 1993–2009. Scand. Polit. Stud. 2016, 39, 185–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seeberg, H.B. The power of the loser: Evidence on an agenda-setting model of opposition policy influence. Eur. J. Polit. Res. 2023, 62, 463–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| 1 | JPP (Juntos Pelo Povo) resists a strict left or right-wing label, its policy positions and affiliations suggest a centrist orientation with regionalist priorities. As a new entrant in the anticipated 2025 general elections, JPP falls outside the scope of this study (2019, 2022, and 2024 general elections). |

| 2 | PAN does not strictly identify as either left-wing or right-wing, though various authors often associate it with the left 27. Eduardo, M. C.; Santos, M. H.; Teixeira, A. L., Gender and Politics: A Descriptive and Comparative Analysis of the Statutes of Brazilian and Portuguese Political Parties. Social Sciences 2023, 12, (8), 1-16, 28. Campos, R.; Jatowt, A.; Jorge, A. In Text Mining and Visualization of Political Party Programs Using Keyword Extraction Methods: The Case of Portuguese Legislative Elections, Information for a Better World: Normality, Virtuality, Physicality, Inclusivity, Cham, 2023; Sserwanga, I.; Goulding, A.; Moulaison-Sandy, H.; Du, J. T.; Soares, A. L.; Hessami, V.; Frank, R. D., Eds. Springer Nature Switzerland: Cham, 2023; pp 340-349, 29. Santana-Pereira, J.; De Giorgi, E., ‘Your Luck is Our Luck’: Covid-19, the Radical Right and Low Polarisation in the 2022 Portuguese Elections. South European Society and Politics 2022, 27, (2), 305-327. |

| 3 | In the 2022 and 2024 elections, PEV did not secure any deputies. PP also failed to elect any deputies in 2022 and formed a pre-coalition leaded by SDP in 2024, with both parties sharing the same electoral manifesto. Consequently, PEV and PP are not included in the collected sample and manifesto from coalition leaded by SDP (with PP) was compared with previous SDP manifestos in the 2019 and 2022 elections. |

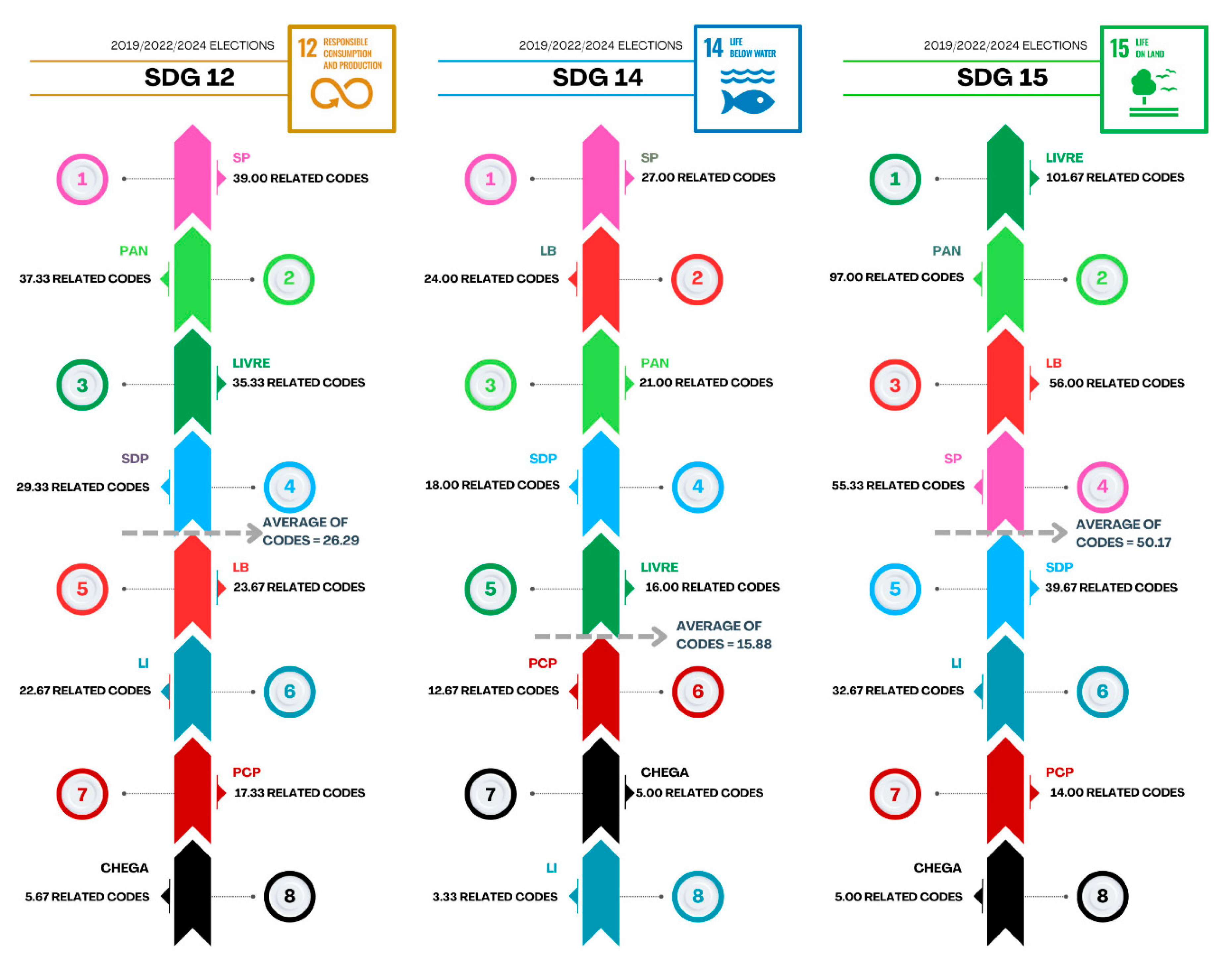

| SDGs | N | Mean | Minimum | Median | Maximum | SD | Skewness | Kurtosis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 12 | 24 | 26.29 | 0 | 26.0 | 54 | 13.08 | -.078 | -.096 |

| 14 | 24 | 15.88 | 0 | 15.50 | 41 | 11.65 | .669 | .362 |

| 15 | 24 | 50.17 | 1 | 48.0 | 142 | 37.43 | .770 | .132 |

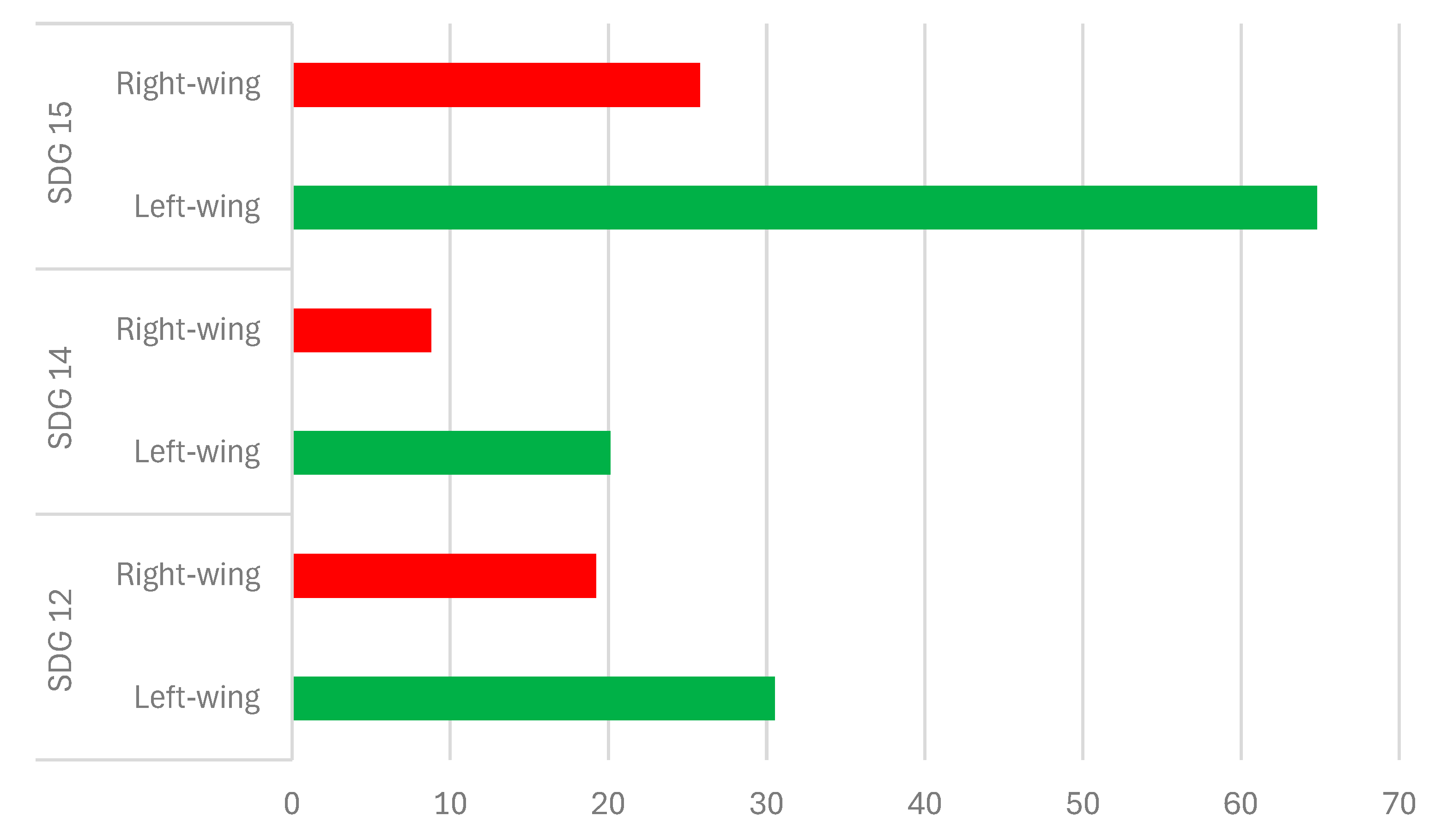

| SDGs | N | Mean | Std. error | Variances | T | df | Sig (1-tailed) | Mean diff. | Std. error |

| SDG 12 | SDG 12 | ||||||||

| Left-wing | 15 | 30.53 | 2.98 | Hom. Variances | 2.220 | 22 | .0185** | 11.361 | 5.799 |

| Right-wing | 9 | 19.22 | 4.33 | Het. Variances | 2.152 | 15.28 | .0239** | 11.361 | 5.863 |

| SDG 14 | SDG 14 | ||||||||

| Left-wing | 15 | 20.13 | 2.93 | Hom. Variances | 2.580 | 22 | .0085*** | 11.356 | 4.401 |

| Right-wing | 9 | 8.78 | 2.86 | Het. variances | 2.771 | 20.63 | .0058*** | 11.356 | 4.098 |

| SDG 15 | SDG 15 | ||||||||

| Left-wing | 15 | 64.80 | 9.89 | Hom. Variances | 2.825 | 22 | .0049*** | 39.067 | 14.200 |

| Right-wing | 9 | 25.78 | 6.55 | Het. variances | 3.291 | 21.68 | .0017*** | 39.067 | 12.138 |

| SDGs | Groups | Sum of squares | Df | Mean square | F | P | Eta squared |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 12 | Between groups | 2,634.13 | 5 | 526.83 | 7.30 | 0.0007*** | 0.670 |

| Within groups | 1,298.83 | 18 | 72.16 | ||||

| Total | 3,932.96 | 23 | |||||

| 14 | Between groups | 1,289.13 | 5 | 257.83 | 2.53 | 0.0666* | 0.413 |

| Within groups | 1,833.50 | 18 | 101.86 | ||||

| Total | 3,122.63 | 23 | |||||

| 15 | Between groups | 23,334.00 | 5 | 4,666.80 | 9.50 | 0.0001*** | 0.709 |

| Within groups | 8,843.33 | 18 | 491.30 | ||||

| Total | 32,177.33 | 23 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).