1. Introduction

Improved sanitation and hygiene practices in educational institutions are important for reducing the spread of germs, avoiding diseases, and enhancing general health. In order to prevent and control the transmission of infectious diseases and to promote good health, it is widely acknowledged that encouraging excellent hygiene and sanitation practices is an affordable, practical, and practical public health approach (Kabir et al. 2021). It has been found that the growing prevalence of infectious diseases in emerging nations is largely caused by inadequate sanitation practices [

1].

Acute respiratory infections, diarrheal ailments, and other illnesses associated with poor personal cleanliness are among the communicable diseases th[

1]at students are more prone to contract while attending college classes. College students frequently practice poor hygiene, endangering their health and leading to a number of negative effects. These include major absences from school, the spread of contagious diseases to other pupils, and parental and guardian missed workdays

Sanitation and hygiene habits have a direct impact on health, and students can be readily taught proper habits, which can be an inexpensive and efficient way to prevent sickness and lower absenteeism from school due to diseases [

2]. Most of population in Ethiopia lack access to safe water, which is the lowest percentage on the continent. Poor environmental health conditions resulting from unsafe and inadequate water supplies as well as poor hygienic and sanitation practices are the cause of more than 60% of communicable diseases in Ethiopia [

3]

Since sanitation and hygiene are both related to health, it’s critical to understand their differences because health is wealth. We can’t even imagine being healthy without both. Unsanitary conditions lead to more terrible illnesses, like the present epidemic caused by the Corona virus, which ultimately end the earth [

4].

Access to safe water, adequate sanitation, and proper hygiene practices (WASH) is essential for health, dignity, and development. Globally, an estimated 2.2 billion people lack access to safely managed drinking water services, while 4.2 billion people do not have safely managed sanitation services [

5].

Poor hygiene and sanitation practices among students can lead to increased incidence of waterborne diseases such as diarrhea, cholera, and intestinal parasites, which disproportionately affect school-aged children. These health issues contribute to absenteeism, reduced learning outcomes, and in severe cases, long-term developmental effects. Furthermore, the lack of gender-sensitive sanitation facilities, particularly for menstruating girls, contributes to gender disparities in education ([

5]. In Ethiopia, although there have been significant improvements in expanding WASH infrastructure, challenges remain, especially in rural and semi-urban areas. According to the 2020 Joint Monitoring Programme (JMP), only 54% of schools in Ethiopia had basic drinking water services, and 27% had basic sanitation facilities [

5].

Educational institutions play a pivotal role in promoting WASH practices. Implementing comprehensive WASH programs within schools, including the establishment of hygiene clubs, provision of handwashing facilities, and regular health education sessions, has been shown to improve students’ hygiene behaviours and reduce the incidence of WASH-related diseases [

6].

3. Results

Out of the 143 questionnaires administered, all 143 were also returned although with varying degrees of missing entries in them. The results as presented in the table below covers responses retrieved from the questionnaire in line with the study objective.

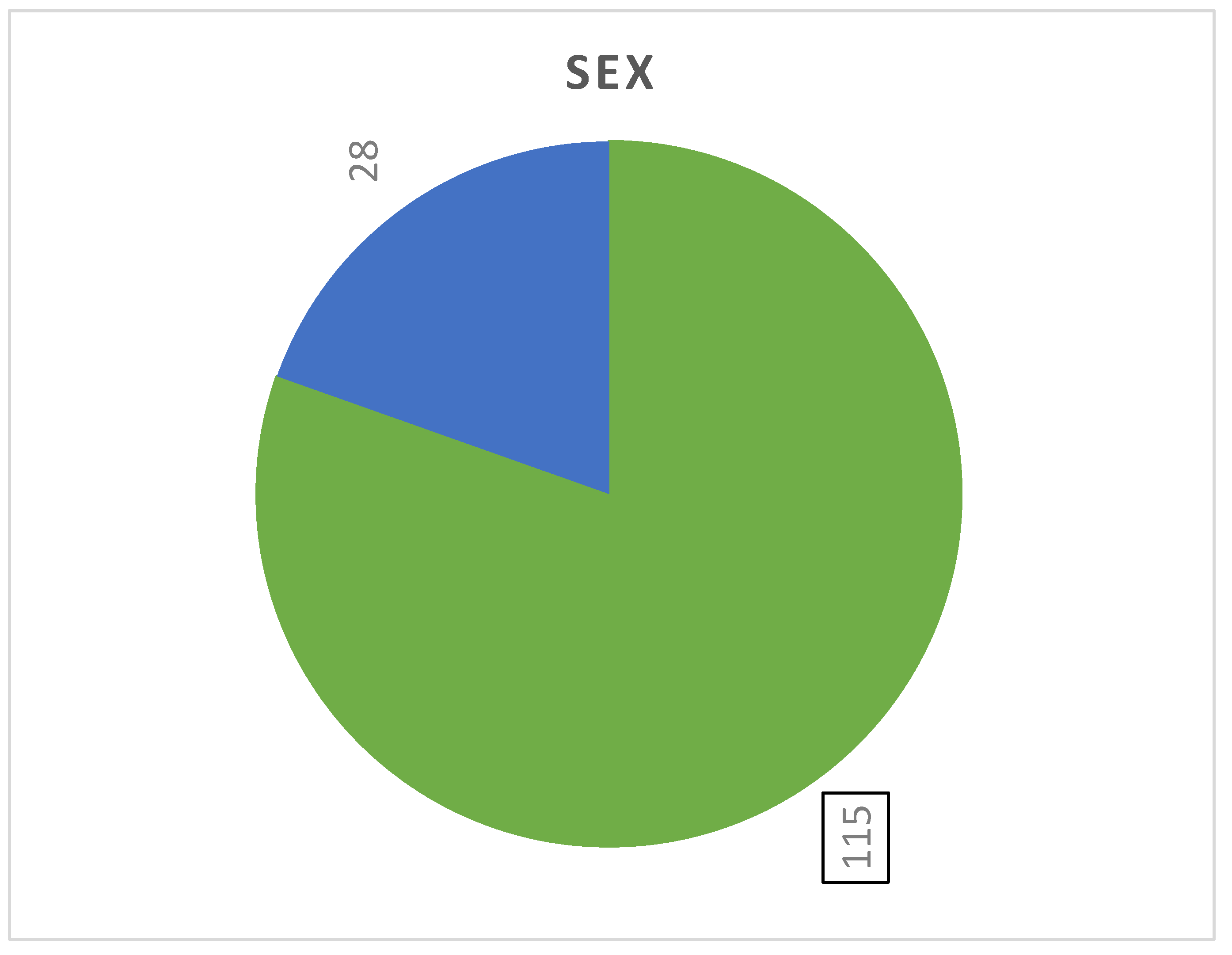

Figure 1.

Study participants by sex.

Figure 1.

Study participants by sex.

3.1. Socio-Demographic Characteristics

A comprehensive Water, Sanitation, and Hygiene (WASH) assessment requires a clear understanding of the socio-demographic background of the target population. Socio-demographic variables provide context to the findings and help identify vulnerable groups or service gaps. The present WASH assessment includes data on the sex, age, academic level, and residence of students of Dr. Abdimajid Hussein College of teacher’s education which is the primary college of teachers training educational college in Somali regional state of Ethiopia.

Among the 143 respondents, 115(78.2%), the majority were male students while female students constituted only 28(19.0%) of the population. This uneven distribution has important implications for WASH services, particularly in ensuring gender-sensitive facilities. A smaller female population does not reduce the importance of adequate, private, and secure hygiene services for women, especially menstrual hygiene management, which is often neglected in male-dominated settings. Planning WASH interventions should take into account the specific needs of female students to promote inclusiveness and equity.

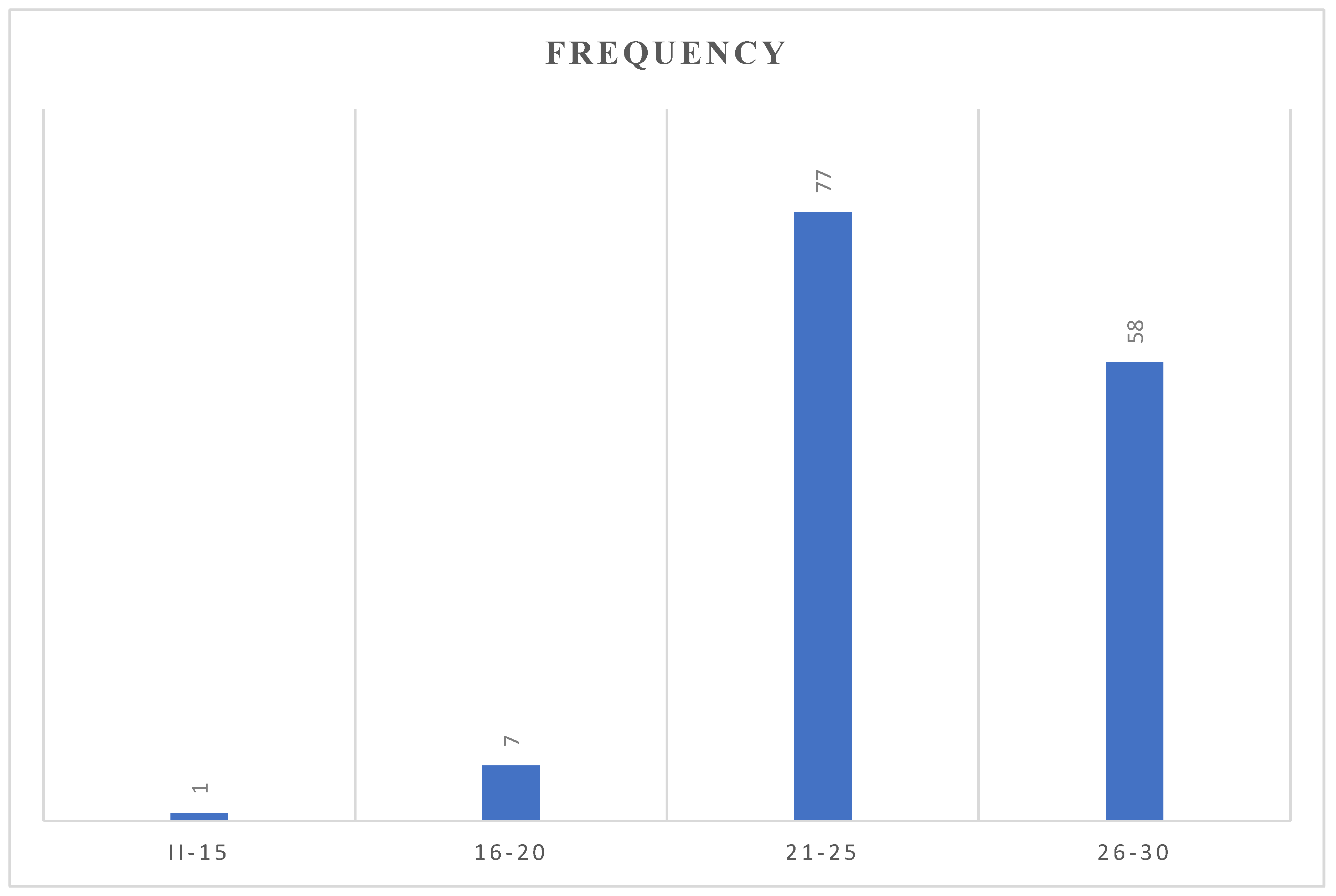

The student population is predominantly composed of young adults aged 21–25; 77(52.4%) and 26–30; 58(39.5%), indicating that the majority of the respondents are likely in the later years of their tertiary education or early professional development stages. Younger age groups, such as those aged 11–15; 1(0.7%) and 16–20; 7(4.8%), are minimally represented. This age profile suggests that students have the capacity to understand and participate in personal hygiene practices and WASH-related awareness programs. Therefore, WASH education and campaigns can be tailored to an adult audience, focusing on behavior change, sustainability, and health outcomes rather than basic hygiene instruction.

Figure 2.

Student age category.

Figure 2.

Student age category.

The study population consists mainly of degree students 105 (71.4%), with diploma students accounting for 38(25.9%). Degree students, possibly spending more years on campus, may have higher exposure to the existing WASH facilities and their quality over time. They may also serve as effective peer educators or focal points for promoting hygiene behavior among the student body. Tailored WASH education programs and leadership roles could be integrated into student activities to reinforce best practices.

The vast majority of respondents 141(95.9%) reside in campus dormitories, with only 2(1.4%) living at home. This is a critical finding for the WASH assessment, as it implies that the students rely heavily on institutional WASH facilities for their daily water usage, sanitation, and hygiene needs. Overcrowding in dormitories may strain available resources and reduce the effectiveness of WASH interventions. This information underscores the need for consistent water supply, clean and adequate toilet facilities, and access to hygiene supplies within student housing. Institutions should also ensure regular maintenance and sanitation services to prevent the spread of disease.

Table 1.

Socio-demographic profile Dr Abdilmajid Hussein CTE study subjects.

Table 1.

Socio-demographic profile Dr Abdilmajid Hussein CTE study subjects.

| Socio-demographic Variables |

Level |

Frequency |

Percentage (%) |

| Students‘ sex |

Male |

115 |

78.2% |

| Female |

28 |

19.0% |

| Age |

11-15 |

1 |

0.7% |

| 16-20 |

7 |

4.8% |

| 21-25 |

77 |

52.4% |

| 26-30 |

58 |

39.5% |

| Student Study years( batch): |

Degree |

105 |

71.4% |

| Diploma |

38 |

25.9% |

| Current residence of the respondents |

Dorm |

141 |

95.9% |

| Home |

2 |

1.4% |

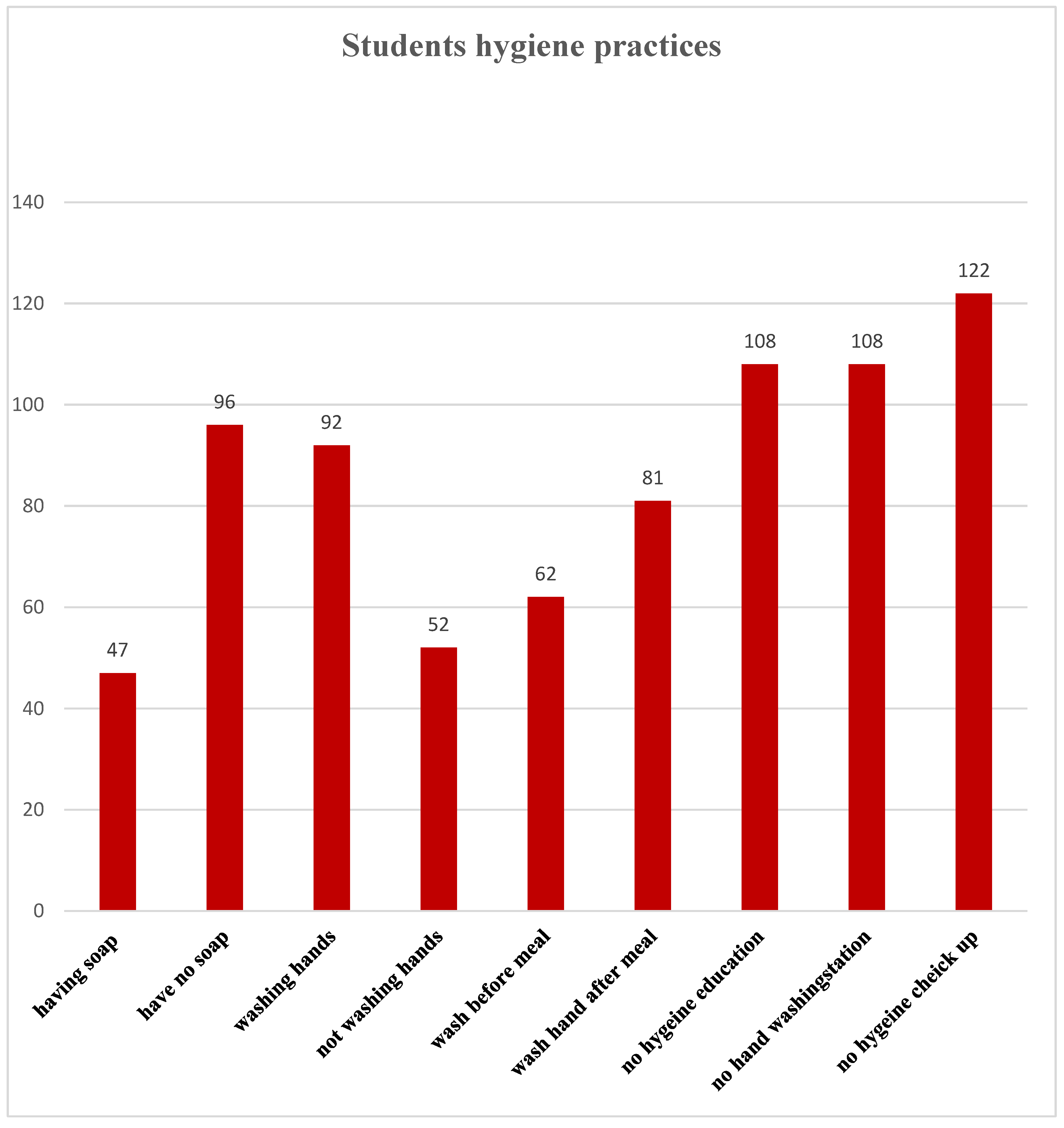

3.2. Assessments of Students Hygiene Practices

Water, Sanitation, and Hygiene (WASH) are essential for safeguarding health and preventing the spread of diseases, particularly in communal settings like colleges. This assessment explores the hygiene-related practices, awareness, and challenges faced by students. The data includes critical indicators such as handwashing behavior, availability of hygiene materials, and personal hygiene habits, providing insight into current conditions and areas for improvement.

Only 47 students (32.0%) reported having soap available at college, while a significantly higher number, 96 students (65.3%), stated that soap was not available. This indicates a major gap in the provision of basic hygiene materials within the institution. The lack of access to soap poses serious health risks, as it directly affects students’ ability to practice effective hand hygiene. One of the simplest and most effective methods of preventing the spread of infectious diseases. This issue should be a top priority for college administrators and health officers aiming to improve WASH standards on campus.

Hand hygiene remains a cornerstone of disease prevention. In this assessment, 91 students (61.9%) reported that they always wash their hands, while 52 students (35.4%) said they do so sometimes. This is encouraging but still leaves room for improvement. 62 students (42.2%) reported washing hands before meals and the rest 81 students don’t wash hands be. 21 students (14.3%) said they brush their teeth twice a day. Only 14 students (9.5%) said they shower daily. 35 students (23.8%) wear clean clothes regularly. Just 11 students (7.5%) reported using deodorant. This shows that while handwashing is somewhat prioritized, other hygiene practices are far less consistently followed.

Good respiratory hygiene helps limit the spread of airborne infections. In this survey, 84 students (57.1%) said they cover their mouth and nose when sneezing or coughing, while 59 students (40.1%) do not. In terms of nail hygiene, 78 students (53.1%) reported that they trim their fingernails and toenails regularly, while 65 students (44.2%) do not.

Education and infrastructure are crucial for sustaining hygienic behavior. However, the majority of students reported gaps in both areas; 108 students (73.5%) said there are not enough hygiene education programs, compared to only 35 students (23.8%) who believed there were sufficient efforts. Similarly, 116 students (78.9%) stated that health education is not incorporated into the curriculum, while only 27 students (18.4%) said it is.In terms of facilities, 108 students (73.5%) indicated there are not enough handwashing stations, and 35 students (23.8%) said the stations were adequate. A striking 122 students (83.0%) reported that there is no personal hygiene check-up system at the college, compared to only 21 students (14.3%) who said there is one.

Figure 3.

Student hygiene practices.

Figure 3.

Student hygiene practices.

Toothbrush replacement habits reveal awareness about oral hygiene.73 students (49.7%) replace their toothbrush only when it looks worn out.35 students (23.8%) replace theirs every 3 months. Another 35 students (23.8%) do so every 6 months. As for bathing habits:64 students (43.5%) reported always bathing regularly.61 students (41.5%) said they bathe sometimes.18 students (12.2%) bathe frequently. None of the respondents reported never bathing.

Over half of the respondents 88 students (59.9%) reported facing barriers to maintaining personal hygiene in college, while 55 students (37.4%) did not. These barriers may include lack of time, or insufficient privacy and facilities.

Sanitation practices are essential for health, particularly handwashing after using the toilet. The responses were as follows: 51 students (34.7%) always wash their hands after defecation.52 students (35.4%) do so frequently.28 students (19.0%) do so sometimes. 12 students (8.2%) never do so.

Table 2.

Assessments of hygiene practices among Dr. Abdilmajid CTE Student.

Table 2.

Assessments of hygiene practices among Dr. Abdilmajid CTE Student.

| Characteristics |

level |

frequency |

Percentage (%) |

| Do you have soap to wash hands at college? |

Yes |

47 |

32.0% |

| No |

96 |

65.3% |

| How often do you wash your hands? |

always |

91 |

61.9% |

| sometimes |

52 |

35.4% |

| Do you use hand sanitizer regularly? |

Yes |

30 |

20.4% |

| no |

113 |

76.9% |

| Which of the following do you do to maintain personal hygiene? |

Shower daily |

14 |

9.5% |

| Brush teeth twice a day |

21 |

14.3% |

| Wash hands before meals |

62 |

42.2% |

| Use deodorant |

11 |

7.5% |

| |

Wear clean clothes |

35 |

23.8% |

| Do you cover your mouth and nose when sneezing or coughing? |

Yes |

84 |

57.1% |

| no |

59 |

40.1% |

| Do you think there are enough hygiene education programs in your school? |

Yes |

35 |

23.8% |

| no |

108 |

73.5% |

| How often do you change your toothbrush? |

Every 3 months |

35 |

23.8% |

| Every 6 months |

35 |

23.8% |

| whenever it looks worn out |

73 |

49.7% |

| Are there enough handwashing stations at your college? |

yes |

35 |

23.8% |

| no |

108 |

73.5% |

| Is there any personal hygiene check up in the college? |

Yes |

21 |

14.3% |

| no |

122 |

83.0% |

| Is health education incorporating in the college curriculum? |

Yes |

27 |

18.4% |

| no |

116 |

78.9% |

| Do you trim your finger and toe nails regularly? |

Yes |

78 |

53.1% |

| no |

65 |

44.2% |

| Is there any barriers do you face in maintaining personal hygiene at college ? |

Yes |

88 |

59.9% |

| no |

55 |

37.4% |

| Washing hands after defecation? |

Always |

51 |

34.7% |

| Frequently |

52 |

35.4% |

| Sometimes |

28 |

19.0% |

| Never |

12 |

8.2% |

| Using soap to wash your hands? |

Always |

66 |

44.9% |

| Frequently |

22 |

15.0% |

| Sometimes |

24 |

16.3% |

| Never |

31 |

21.1% |

| Maintaining regularity in taking a bath? |

Always |

64 |

43.5% |

| Frequently |

18 |

12.2% |

| Sometimes |

61 |

41.5% |

| Never |

0 |

0% |

| Wearing washed clothes? |

Always |

82 |

55.8% |

| Frequently |

40 |

27.2% |

| Sometimes |

20 |

13.6% |

| Never |

1 |

0.7% |

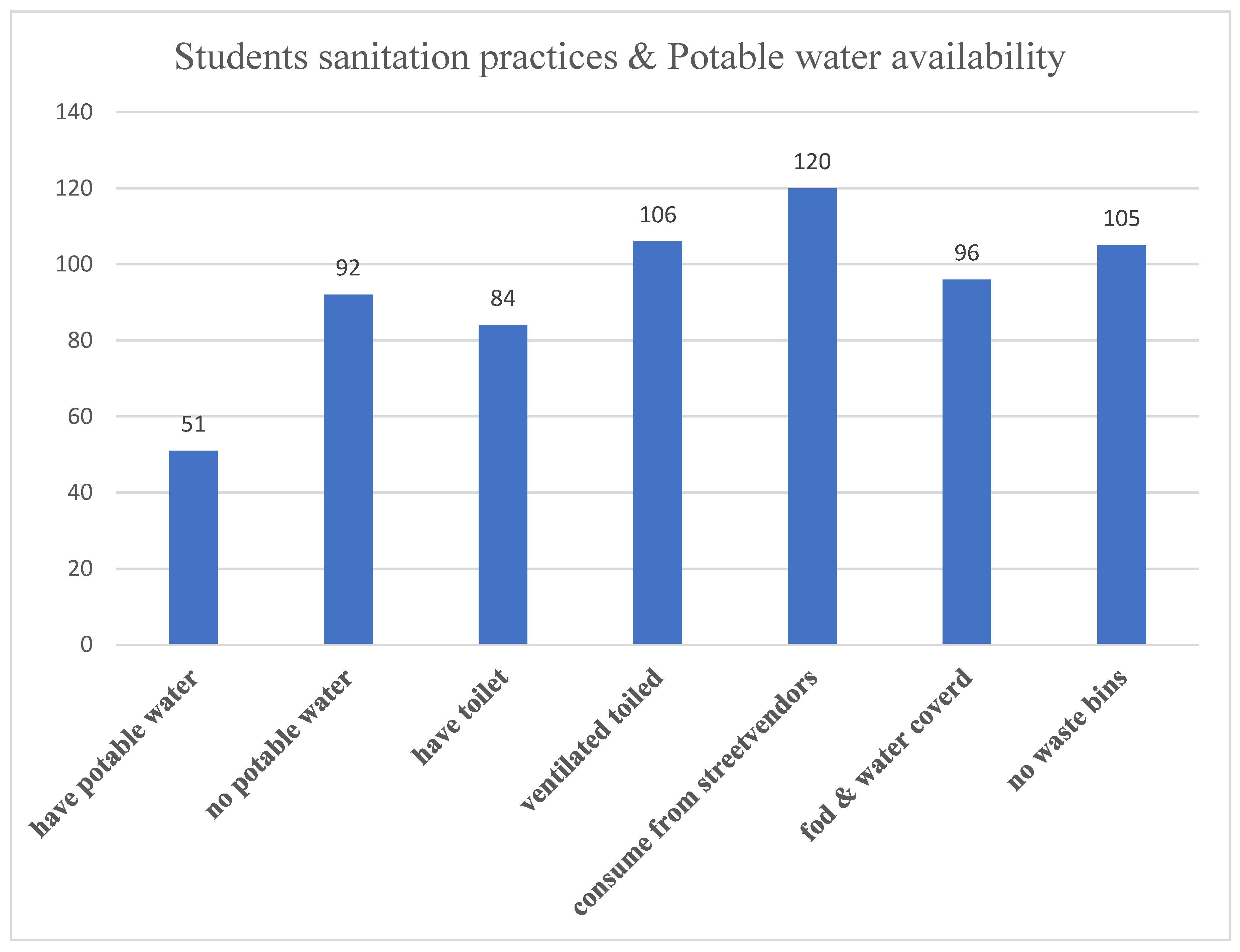

3.3. Assessments of Potable Water and Sanitation Practices among students

A clean and safe college environment is crucial for student health, learning, and overall well-being. This study evaluates the potable water availability, sanitation infrastructure, hygiene practices, and students’ perceptions at Dr. Abdilmajid Hussein College of Teacher Education (CTE). The data reflects important strengths and weaknesses in the institution’s current WASH (Water, Sanitation, and Hygiene) framework.

Only 51 students (34.7%) confirmed having access to potable water at college, while 92 students (62.6%) reported the lack of it, suggesting a serious gap in basic water provision. While 84 students (57.1%) acknowledged the presence of toilet facilities, 59 (40.1%) said they were unavailable. This indicates that a significant proportion of students do not have reliable access to safe water and sanitation. Additionally, while 106 students (72.1%) reported that toilets are ventilated, 37 (25.2%) said they are not, highlighting mixed perceptions of facility quality.

Daily consumption of food and drinks from street vendors is high among students, with 120 students (81.6%) reporting such behavior, which raises concerns about food safety. Encouragingly, 96 students (65.3%) reported keeping food and water covered and protected from flies, which is a positive hygiene behavior. The availability of waste bins near classrooms was poor, with only 38 students (25.9%) indicating they had nearby access, compared to 105 students (71.4%) who did not.

Sanitation facilities were deemed inadequate by 96 students (65.3%), while only 47 (32.0%) felt they were sufficient. Despite the challenges, 89 students (60.5%) felt the college supports sanitation practices, while 54 (36.7%) disagreed. when asked how often they clean their living space: Daily: 52 (35.4%) Weekly: 51 (34.7%) Monthly: 20 (13.6%) Rarely: 20 (13.6%) This shows a fairly strong commitment to dorm hygiene, though regularity varies.

Use of separate sandals for toilet use remains limited;Always 44 (29.9%)Frequently 24 (16.3%)Sometimes (0.7%)Never 74 (50.3%).Study identified key areas in need of improved sanitation:Restrooms: 50 (34.0%)Dorms: 32 (21.8%)Cafeteria: 32 (21.8%)Classrooms: 20 (13.6%)Lockers: 9 (6.1%)Study also expressed the preferences for policy improvements:Better facility maintenance: 46 (31.3%)Increased hygiene education: 33 (22.4%)Student involvement in sanitation: 30 (20.4%)More frequent cleaning: 20 (13.6%) Stricter rule enforcement: 14 (9.5%)In terms of waste disposal methods: Recycling bins: 50 (34.0%)Trash bins: 46 (31.3%)Composting: 37 (25.2%)Don’t know: 10 (6.8%)Study suggest the following as essential elements for sanitation:Trash cans: 41 (27.9%)Hand sanitizing stations: 27 (18.4%)Clean water sources: 26 (17.7%)Proper waste disposal systems: 25 (17.0%) Regular cleaning schedules: 24 (16.3%)

Figure 4.

Students sanitation practices & Potable water availability.

Figure 4.

Students sanitation practices & Potable water availability.

The Study suggested various measures to improve sanitation; Regular sanitation inspections: 33 (22.4%)More cleaning staff; 29 (19.7%)Availability of clean water; 29 (19.7%)Handwashing campaigns; 26 (17.7%)Promotion of hygiene awareness; 26 (17.7%).Regarding good food safety practices, students highlighted Washing fruits and vegetables; 45 (30.6%)Refrigerating perishables; 30 (20.4%)Checking expiration dates;25 (17.0%)Cooking food thoroughly;22 (15.0%)Separating raw/cooked foods: 21 (14.3%).A large majority, 101 students (68.7%), also agreed there should be stricter penalties for littering, showing a strong demand for better enforcement. Finally, when asked about factors contributing to disease spread; Untidy restrooms;55 (37.4%)Poor ventilation; 28 (19.0%)Lack of handwashing; 27 (18.4%)Shared utensils; 21 (14.3%)Overcrowded classrooms; 12 (8.2%).

Table 3.

Assessments of Potable Water and Sanitation Practices among Dr. Abdilmajid Hussein CTE Students.

Table 3.

Assessments of Potable Water and Sanitation Practices among Dr. Abdilmajid Hussein CTE Students.

| Characteristics |

level |

Frequency |

Percentage (%) |

| Do you have potable water at college? |

Yes |

51 |

34.7% |

| no |

92 |

62.6% |

| Do you have a toilet facility? |

Yes |

84 |

57.1% |

| no |

59 |

40.1% |

| Is toilet ventilated? |

Yes |

106 |

72.1% |

| No |

37 |

25.2% |

| Is the waste bin positioned close to your classroom? |

Yes |

38 |

25.9% |

| no |

105 |

71.4% |

| Daily consume edibles/drinks from street vendors |

Yes |

120 |

81.6% |

| no |

23 |

15.6% |

| Keeps water and edibles covered or protected from flies |

Yes |

96 |

65.3% |

| no |

47 |

32.0% |

| Maintaining regularity in cleaning your Dorm? |

Always |

65 |

44.2% |

| Frequently |

42 |

28.6% |

| Sometimes |

24 |

16.3% |

| Never |

12 |

8.2% |

| Where do you think there is a need for improved sanitation in your college? |

Restrooms |

50 |

34.0% |

| Classrooms |

20 |

13.6% |

| Cafeteria |

32 |

21.8% |

| Dorms |

32 |

21.8% |

| Locker |

9 |

6.1% |

| Using separate sandals for toilet? |

Always |

44 |

29.9% |

| Frequently |

24 |

16.3% |

| Sometimes |

1 |

0.7% |

| Never |

74 |

50.3% |

| How often do you clean your living space (room or dorm)? |

daily |

52 |

35.4% |

| weekly |

51 |

34.7% |

| monthly |

20 |

13.6% |

| rarely |

20 |

13.6% |

| Which of the following do you consider essential for maintaining good sanitation in public areas? |

Trash cans for litter |

41 |

27.9% |

| Hand sanitizing stations |

27 |

18.4% |

| clean water sources |

26 |

17.7% |

| Proper waste disposal systems |

25 |

17.0% |

| Regular cleaning schedules |

24 |

16.3% |

| How do you dispose your waste properly? |

Trash bins |

46 |

31.3% |

| Recycling bins |

50 |

34.0% |

| Composting |

37 |

25.2% |

| don’t know |

10 |

6.8% |

| What changes would you like to see in the college sanitation policies? |

more frequent cleaning |

20 |

13.6% |

| Better maintenance of facilities |

46 |

31.3% |

| Increased hygiene education |

33 |

22.4% |

| Strict enforcement of sanitation Rules |

14 |

9.5% |

| Student involvement in sanitation initiatives |

30 |

20.4% |

| Which of the following do you believe are good practices for food safety? |

Washing fruits and vegetables |

45 |

30.6% |

| separating raw and cooked foods |

21 |

14.3% |

| cooking food thoroughly |

22 |

15.0% |

| refrigerating perishable item |

30 |

20.4% |

| Checking expiration dates |

25 |

17.0% |

| Do you think the school should provide more sanitation facilities? |

yes |

96 |

65.3% |

| no |

47 |

32.0% |

| Do the college support students in maintaining good sanitation practices? |

Yes |

89 |

60.5% |

| no |

54 |

36.7% |

| Which of the following do you think can help improve sanitation practices in your college? |

more cleaning staff |

29 |

19.7% |

| Handwashing campaigns |

26 |

17.7% |

| Regular sanitation inspections |

33 |

22.4% |

| Promotion of hygiene awareness |

26 |

17.7% |

| Availability of clean water |

29 |

19.7% |

| Do you think there should be stricter penalties for littering at your college? |

yes |

101 |

68.7% |

| no |

42 |

28.6% |

| Which of the following do you think can contribute to the spread of diseases at your college? |

Lack of handwashing |

27 |

18.4% |

| Shared utensils |

21 |

14.3% |

| Poor ventilation |

28 |

19.0% |

| Overcrowded classrooms |

12 |

8.2% |

| Untidy restrooms |

55 |

37.4% |

Observation Findings

Using a structured observation checklist, the researchers assessed the adequacy andutilization of sanitation facilities at Dr. Abdilmajid Hussein College of Teacher’s Education. Observations revealed several critical issues:

Latrine Conditions: Most latrines lacked proper superstructures, resulting in poor privacy and exposure to external elements. Many latrines were unclean, with visible dirt and waste around the latrine hole and floor areas. Coverage of latrine holes was often missing or damaged, posing health and safety risks.

Handwashing Facilities: Handwashing stations were either insufficient in number or poorly maintained. In many cases, water was not available at the handwashing points, and soap was entirely absent. This severely limited the students’ ability to perform effective hand hygiene.

Compound Sanitation: Overall compound sanitation was poor, with litter and stagnant water observed in various parts of the college premises, which could increase exposure to pathogens.

Water and Utensil Hygiene: Water storage containers and food utensils were often found to be inadequately cleaned or improperly covered, increasing the risk of contamination.

Focus Group Discussions (FGDs)

FGDs conducted with members of the Water, Sanitation, and Hygiene Committees (WASH COMs) provided valuable insights into the challenges and perceptions related to hygiene management on campus:

Infrastructure Challenges: Participants acknowledged the lack of sufficient handwashing stations and the poor maintenance of existing facilities. One committee member remarked, “We often face shortages of soap and water, and the latrines are not cleaned regularly, which discourages students from using them properly.”

Hygiene Education and Awareness: Committee members emphasized that hygiene education is limited and sporadic. They highlighted the need for continuous hygiene promotion activities to improve students’ knowledge and practices.

Resource Constraints: Limited funding and support from the college administration were cited as major barriers to improving sanitation infrastructure and ensuring the availability of hygiene supplies.

Behavioural Factors: WASH COMs noted that some students neglect hygiene practices due to lack of awareness or motivation, and others face practical barriers such as overcrowding and insufficient privacy in sanitation facilities.

Together, these qualitative findings complement the quantitative data, illustrating how infrastructural deficiencies and lack of consistent hygiene education contribute to inadequate personal hygiene practices among students. They also highlight areas for targeted intervention, including infrastructure improvement, resource allocation, and behavioural change programs.

4. Discussion

The findings of this study reveal significant gaps in access to water, sanitation, and hygiene (WASH) infrastructure and practices among students at Dr. Abdimajid Hussein College of Teacher Education in Jigjiga, Ethiopia. This section interprets the results in light of existing literature, highlighting both alignments and contrasts, and identifying implications for policy and future research.

A major concern emerging from the study is the lack of adequate hygiene infrastructure. Only 32.0% of students reported having access to soap on campus, and just 23.8% considered the available handwashing stations to be adequate. These findings are consistent with national studies showing similar inadequacies in Ethiopian schools. For instance Kumie

et.al, 2022 reported that many schools in Addis Ababa had non-functional or overcrowded handwashing facilities, with inconsistent soap availability. Globally, similar WASH challenges are evident in schools in Nepal Adhikari et.al, 2024 and Ghana Abanyie et.al, 2021 where infrastructural deficits hinder hygiene compliance [

10,

11,

12].

Despite some awareness 61.9% of students reported always washing their hands other critical hygiene behaviors were poorly observed, such as daily showering (9.5%) and deodorant use (7.5%). These findings suggest a disconnect between hygiene knowledge and behavior. This pattern has been observed in other Ethiopian contexts. Degefu et.al, 2023 found that although over 85% of urban schools had functional handwashing stations, less than one-third of students washed their hands at critical times. This discrepancy supports the view that physical infrastructure alone is insufficient unless supported by health education and institutional reinforcement Freeman

et.al, 2012 [

13,

14].

Access to safe drinking water and adequate sanitation facilities also emerged as critical issues. Only 34.7% of students reported access to potable water, while 62.6% reported lacking it. Additionally, while 57.1% had access to toilets, nearly 40.1% of students still lacked such basic sanitation. Although 72.1% of those facilities were ventilated, cleanliness and privacy were often cited as concerns. These findings are consistent with the broader literature. Admasie

et.al, 2016 National surveys in Ethiopia have similarly documented struggles in maintaining consistent access to improved water sources in schools Kumie

et.al, 2022. Comparable global data from Ghana Abanyie

et.al, 2021 and India Sharma et al., 2019 reinforce the conclusion that lack of infrastructure directly impacts students’ ability to maintain hygiene [

10,

12,

15].

Another major finding was the high prevalence of unsafe food practices. A large proportion of students (81.6%) reported consuming street food daily. While 65.3% reported covering their food and drinks, waste management on campus was poor, with 71.4% noting the absence of bins near classrooms. These findings mirror those of Admasie

et.al, 2016 who reported poor waste disposal systems in Ethiopian communities. Globally, the lack of structured hygiene promotion and food safety education has been linked to increased risk of foodborne illnesses WHO/UNICEF, 2021 [

5].

Students demonstrated awareness and willingness to improve WASH conditions, with 65.3% stating that more sanitation facilities were needed and 68.7% supporting penalties for littering. However, 78.9% reported that hygiene education was not part of the curriculum, underscoring a key institutional gap Eshetu

et.al, 2020 found similar results in Miralem Town, where despite positive attitudes toward hygiene, only 39.1% of students practiced handwashing regularly. This highlights the need for structured hygiene education alongside infrastructural improvements [

16].

Contrary to the findings of this study, research at Bahir Dar Tabor

et.al, 2011 showed that more than 80% of students consistently practiced hand hygiene. This discrepancy was attributed to active WASH promotion and recent infrastructure investment, demonstrating the effectiveness of institutional support. Comparable findings have emerged from Kenya KATHUNI,

et.al, 2021 and Ghana Abanyie

et.al, 2021, where hygiene behaviors improved significantly following targeted WASH interventions [

12,

17,

18].

5. Conclusion and Recommendations

The dominance of male students, the young adult age group, and the high number of dormitory residents highlight the need for targeted and context-sensitive WASH services. Institutions should prioritize inclusive planning, address female needs, ensure cleanliness, and engage students in sustainable hygiene practices to create a healthier, safer, and more equitable environment.

The WASH assessment highlights critical gaps in hygiene practices, resource availability, and educational support among students. While some students demonstrate good handwashing habits, others struggle with consistent personal hygiene due to barriers and lack of infrastructure. The absence of hygiene education in the curriculum and the shortage of handwashing stations exacerbate the problem.

The WASH assessment highlights gaps in hygiene practices, resource availability, and educational support among students. While some students demonstrate good handwashing habits, others struggle with consistent personal hygiene due to barriers and lack of infrastructure. The absence of hygiene education in the curriculum and the shortage of handwashing stations exacerbate the problem.

5.1. Conclusion

The findings of this study highlight significant challenges in the Water, Sanitation, and Hygiene (WASH) conditions at Dr. Abdilmajid Hussein College of Teacher Education. Despite some positive behaviours among students such as covering food and maintaining personal dorm hygiene the overall WASH infrastructure remains inadequate. Limited access to potable water, insufficient and poorly maintained sanitation facilities, and a lack of proper waste disposal systems are major concerns. A substantial number of students also rely on street food and do not consistently follow basic hygiene practices like using separate sandals for toilet use.

To foster a safe and healthy learning environment, the college should prioritize investment in reliable water access, upgrade sanitation infrastructure, and implement consistent hygiene promotion campaigns. Collaborative efforts involving administration, staff, and students are essential to transform current WASH conditions and support students’ well-being, academic success, and quality of life.

5.2. Recommendations

College administrations should prioritize the provision of adequate hygiene facilities, including the consistent availability of soap and sufficient handwashing stations.

Regular hygiene monitoring and check-up systems should be established to reinforce good practices and identify areas needing improvement.

Hygiene education must be integrated into the college curriculum to raise awareness and encourage consistent personal hygiene practices among students.

Future interventions should address identified barriers such as lack of privacy and time constraints to ensure effective hygiene behavior change.

Further research is recommended to evaluate the impact of these interventions and to explore contextual factors influencing student hygiene in diverse educational settings.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Abas Mahammed Abdi methodology, Abas Mahammed Abdi validation, Abas Mahammed Abdi And Kafi Hassen; formal analysis, Abas Mahammed Abdi.; data curation, Abas Mahammed Abdi and Kafi Hassen; writing original draft preparation, Abas Mahammed Abdi.; writing review and editing, Abas Mahammed Abdi., Kafi Hassen, Alemayo Aschalew, Abdilahi Dill and Mohamed Arab visualization, Abas Mahammed Abdi, Kafi Hassen, Abdilahi Dill, Alemayo Aschalew and Mohammmed Arab.; supervision, Abas Mahammed Abdi, Kafi Hassen, Abdilahi Dill, Alemayo Aschalew and Mohamed Arab. Review and editing, Abas Mahammed Abdi project administration, Abas Mahammed Abdi and Kafi Hassen.; funding acquisition, Abas Mahammed. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.