1. Introduction

Multitouch interfaces on devices like tablets and smartphones enable direct manipulation of content, offering a more natural interaction than traditional Windows, Icons, Mouse, Pointer (WIMP) systems. Users can drag or pinch objects directly, leveraging familiar physical gestures rather than indirect controls such as arrow keys.

These interfaces embody Natural User Interfaces (NUIs), which use intuitive actions—pointing, drawing, speech, gaze—over conventional input devices [

1]. However, multitouch screens are limited to two-dimensional gestures, requiring 3D interactions to be mapped onto a flat surface, often leading users to rely on simple single-point gestures [

2,

3,

4].

User interaction with NUIs is shaped by prior experience with devices and software, rather than purely innate intuitiveness. Instead of assuming users are untrained, it is important to recognize the influence of their existing digital habits.

Building on previous research into user-selected gestures for controlling small robot groups [

5], this study examines how gesture choices evolve with increasing swarm size. We hypothesize that beyond a certain number of robots, users shift from individual commands to group-based gestures, such as shaping or moving clusters, reflecting a change in mental model.

Furthermore, how the swarm is visually represented affects this transition. When individual robots become too small to interact with effectively, showing the swarm as a collective boundary or cloud—rather than individual icons—may encourage group-level interaction, as demonstrated in UAV control systems [

6]. This visual abstraction is expected to coincide with changes in user gesture patterns.

2. Related Work

Research on gesture-based user interfaces generally falls into two categories: those aimed at creating universal gesture sets applicable across various contexts, and those tailored to specific tasks or domains.

Universal or general-purpose gesture sets are commonly designed for fundamental operations like cut, copy, paste, and other standard editing functions. These actions are widely used in word processing, image manipulation, and general productivity software. Although their exact implementation may vary depending on the context, the way these operations are invoked remains largely consistent across software platforms and operating systems.

Wobbrock, Morris, and Wilson introduced a notable method for eliciting such general gestures from users without technical expertise [

2]. Their study involved presenting participants with the outcome of a particular command and asking them to demonstrate the gesture they believed would have triggered it. Participants were encouraged to verbalize their thought processes, providing insight into their mental models and intuitive gesture mappings. The researchers tested 27 different commands—ranging from basic actions like "move a little" to more complex ones like "task switch" or "undo"—and found that many corresponded to widely recognized UI metaphors. These gestures, especially those associated with window management and common application functionality, are often implemented uniformly across systems.

On the other hand, task-specific gesture design focuses on specialized operations that are tightly bound to the domain in question. Examples include navigating a 3D architectural model or rearranging data in a spreadsheet. While these gestures can still be intuitive, they are typically unique to the specific function or application context.

For instance, Yao, Fernando, and Wang developed a gesture set tailored to urban planning applications [

7]. They used paper prototyping, placing a physical map on a table and asking participants to perform gestures for various tasks. Their findings informed the design of a modal interface, where available gestures depended on the user’s chosen interaction mode. The system also supported gesture combinations—such as zooming while simultaneously panning or rotating the map—demonstrating the complexity that task-specific gesture design can entail.

Micire

et al. contributed a taxonomy focused on gestures for robotic swarm control and the interfaces used to manage them [

5]. They distinguished between interface-level gestures (e.g., zooming or panning a map) and gestures meant to command robots. Despite individual variation in gesture preferences, the study found that having just two gesture options per task was sufficient to satisfy 60% of users. A key takeaway from their work was the influence of prior user experience: familiarity with traditional WIMP interfaces and multitouch smartphones significantly shaped users’ gesture choices. For example, iPhone users were far more likely to use pinch gestures than those unfamiliar with the device.

These findings suggest that general-purpose gesture sets—such as those proposed by Wobbrock et al.—could be integrated into operating systems or window managers. In contrast, the more specialized gesture sets developed by Yao et al., Micire et al., and in this study are best suited for domain-specific interfaces that require fine-grained control and nuanced interactions.

3. Experiment Setup

3.1. Interface and Participant Interaction

Participants used a touchscreen interface guided by a scripted introduction that explained the system’s purpose. The interface alternated between task instructions (e.g., "Move robots to Area A") and static UI screens, without providing real-time robot feedback—simulating a low-fidelity prototype [

8].

The setup included a 3M M2265PW multitouch screen supporting 20 touch points, though it only captured coordinates. To record user interactions:

An overhead camera tracked hand positions relative to the screen.

A front-facing camera captured touch vs. hover behavior.

A microphone recorded verbal feedback as participants spoke aloud during tasks.

3.2. Data Collection Framework

ROS [

9] was used to log all interactions. Key tools included:

ROS Nodes for capturing video, audio, and touch events.

Rosbag to record and replay synchronized experiment data.

Custom Scripts to overlay touch data on UI for review.

3.3. Experimental Conditions

Each participant completed tasks under five swarm size conditions:

Tasks were adjusted to suit each condition—e.g., group coordination tasks were excluded for 1–2 robots.

3.4. Task Allocation

Table 1 shows which tasks were assigned under each condition. An ‘x’ marks task inclusion.

3.5. Task Design and Analysis

Some tasks, such as forming shapes or merging groups, were excluded in conditions where they weren’t feasible (e.g., single robot). Similarly, tasks requiring identification of individual units were omitted in the abstract swarm condition due to lack of robot-level distinction.

Data from all sensors were synchronized using ROS and analyzed through custom scripts to study user behavior, gesture types, and interaction strategies across swarm sizes.

3.6. Ethical Considerations

This study involved voluntary participation in a non-invasive usability task involving a multi-touch screen interface. No identifiable personal data were collected. As the study posed minimal risk and did not involve vulnerable populations, it was considered exempt from formal institutional review board (IRB) approval under standard academic research guidelines.

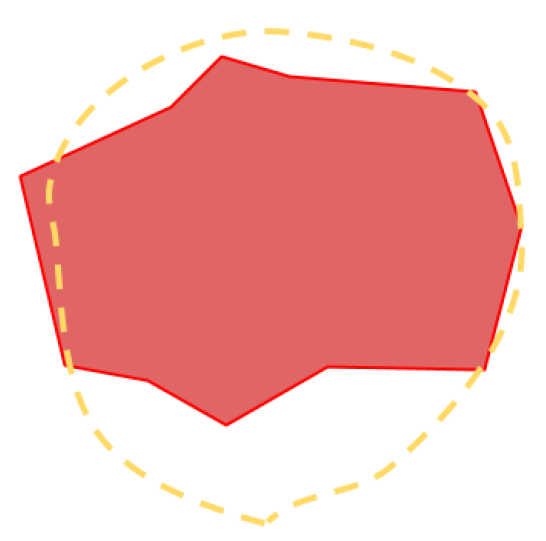

Figure 1.

Selection strategy: X.

Figure 1.

Selection strategy: X.

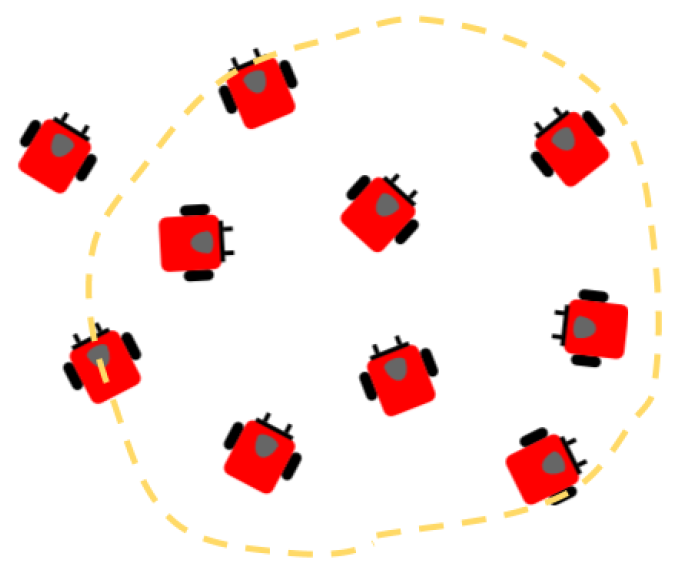

Figure 2.

Selection strategy: 10.

Figure 2.

Selection strategy: 10.

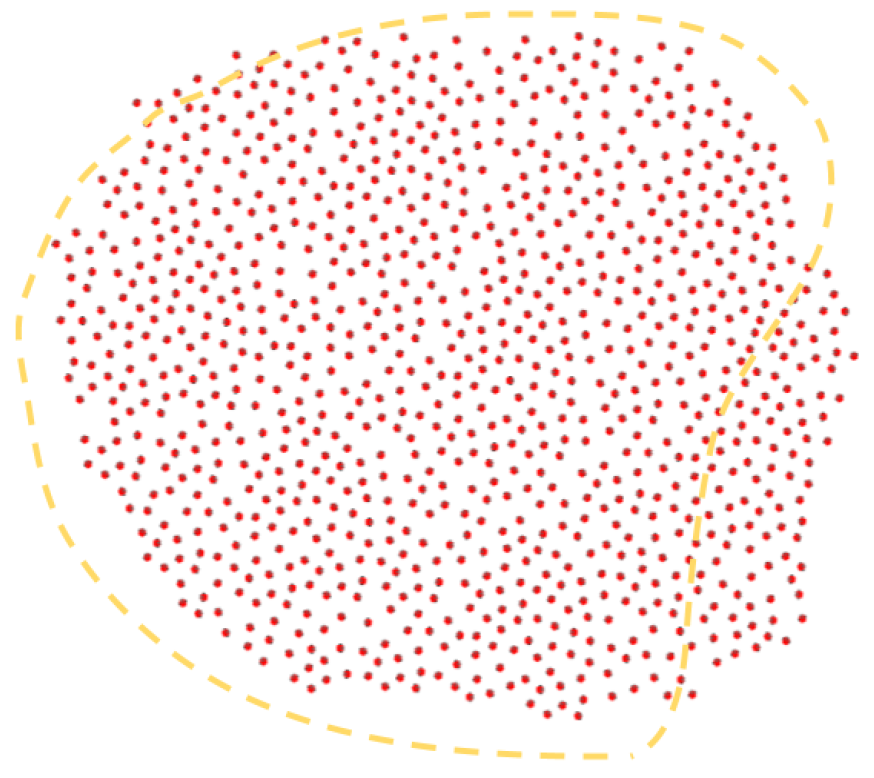

Figure 3.

Selection strategy: 100.

Figure 3.

Selection strategy: 100.

Figure 4.

Selection strategy: 1000.

Figure 4.

Selection strategy: 1000.

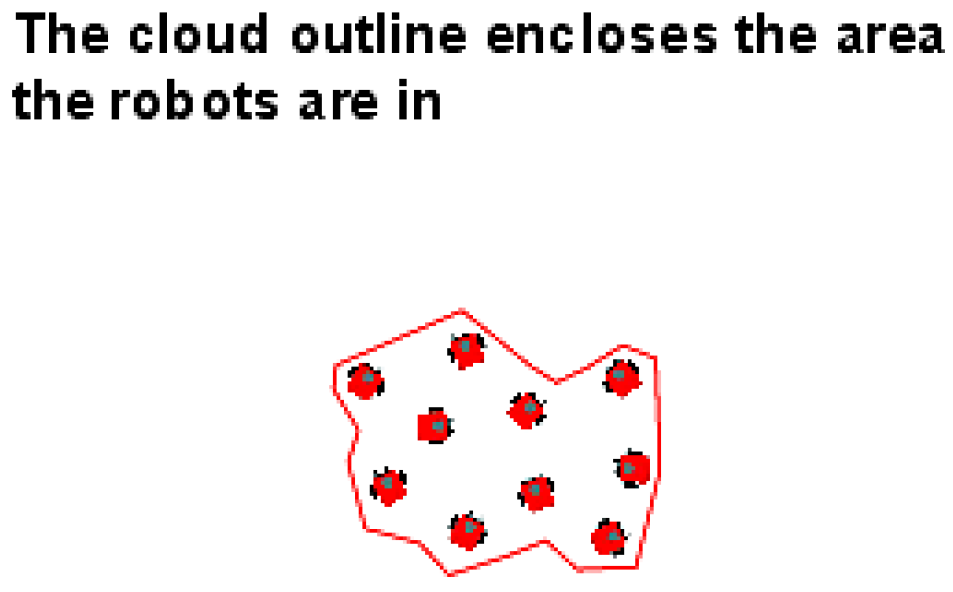

Figure 5.

Instructional slide 1 for the unknown number of robots condition.

Figure 5.

Instructional slide 1 for the unknown number of robots condition.

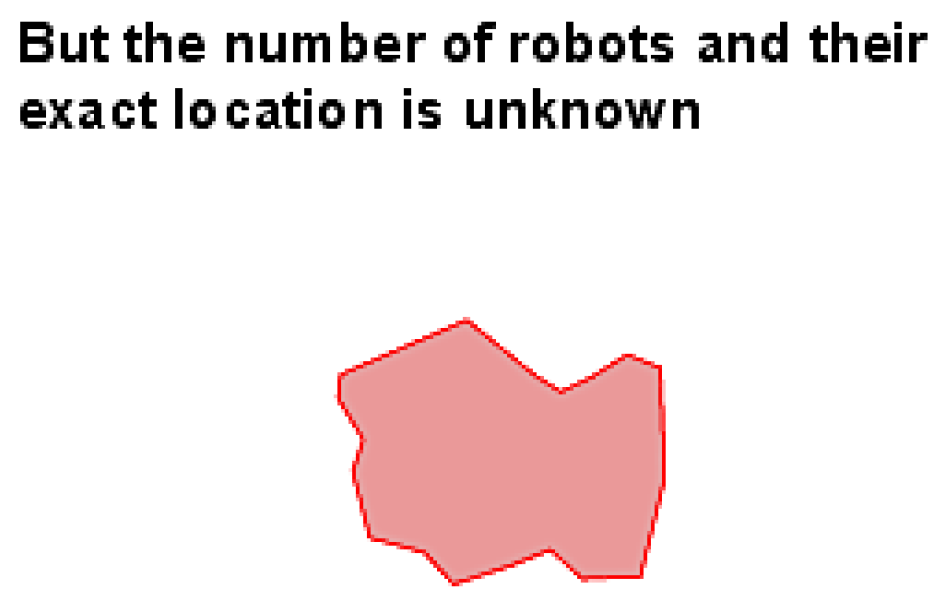

Figure 6.

Instructional slide 2 for the unknown number of robots condition.

Figure 6.

Instructional slide 2 for the unknown number of robots condition.

Figure 7.

Instructional slide 3 for the unknown number of robots condition.

Figure 7.

Instructional slide 3 for the unknown number of robots condition.

4. Results and Analysis

To evaluate the effectiveness of the proposed Structured State Space Model (SSM), we conducted experiments on the BraTS 2021 brain MRI dataset using the Dice Score, Sensitivity, Specificity, and Positive Predictive Value (PPV) as our primary performance metrics. These metrics were chosen to provide a comprehensive view of segmentation performance:

Dice Score evaluates the overlap between the predicted and ground truth masks.

Sensitivity (Recall) reflects the model’s ability to correctly identify tumor pixels.

Specificity measures how well the model avoids false positives.

Positive Predictive Value (PPV) quantifies the precision of tumor segmentation.

Our method was benchmarked against several standard segmentation approaches, including U-Net, TransUNet, and SMaTE, to assess its relative performance.

Table 2 summarizes the quantitative results of each model on the test set.

The proposed SSM-based architecture significantly outperforms baseline models across all four evaluation metrics. It achieves a Dice Score of 0.902, demonstrating superior spatial alignment with ground truth segmentations. Its Sensitivity of 0.912 indicates improved tumor pixel detection, minimizing false negatives—critical in clinical applications where missed tumors could lead to adverse outcomes.

Notably, the Specificity (0.941) and PPV (0.885) values suggest that our model produces fewer false positives and offers better precision, respectively. These gains can be attributed to the Mamba architecture’s ability to effectively model long-range spatial dependencies and hierarchical contextual information, enhancing both global and local feature representation.

We observed that traditional architectures like U-Net, though efficient and widely used, underperform in complex tumor structures due to limited receptive field and convolutional bottlenecks. Transformer-based models like TransUNet improve upon this by capturing broader context but often require heavy computation. SMaTE further optimizes memory and accuracy trade-offs, yet our method demonstrates a better balance of performance and efficiency.

Overall, the results validate that incorporating structured state space modeling in segmentation pipelines not only boosts performance but also ensures a robust and clinically relevant prediction framework. Further improvement could be achieved by integrating uncertainty estimation or ensemble approaches for enhanced generalizability.

5. Conclusions

This study explored the interaction paradigms between users and multiple robots through a shared interface, specifically focusing on how users assign and manage tasks such as crate movement and obstacle navigation. Our results reveal that users often utilize visual information about individual robots, including their positions and identities, to orchestrate effective strategies for task execution.

Looking forward, a compelling direction for future research involves redesigning the interface to exclude the direct visualization of robots altogether. In such a setup, the system would present a more abstracted control scheme where users interact solely with task objectives—such as instructing that a crate be moved to a designated location—without visual cues about the robots themselves. We hypothesize that under these conditions, users might rely more on high-level commands and outcome-based reasoning rather than micro-managing specific robot units.

This type of minimal-visibility interface could prove especially effective for straightforward objectives like “move the crate to area A,” where the emphasis is on goal achievement rather than agent selection. The system would automatically handle the allocation of appropriate robots, thereby reducing cognitive load and simplifying the user’s decision-making process.

However, this abstraction comes at a potential cost. Without visibility into individual or grouped robot identities, users would be unable to direct actions requiring coordination among specific units. Complex spatial strategies—such as instructing robots to surround or avoid an obstacle, or to execute synchronized behaviors—may become difficult or entirely unfeasible. The loss of granularity in control may hinder performance in tasks that require explicit spatial reasoning and cooperative manipulation among subsets of the robot team.

Therefore, future work should investigate the trade-offs between abstraction and control. Key areas of interest include measuring task completion efficiency, user satisfaction, cognitive workload, and the system’s adaptability to varied task types. Hybrid approaches—offering users the ability to toggle between abstract and detailed views—might offer a balanced solution, optimizing both usability and control granularity. Ultimately, this line of research could contribute significantly to the development of intuitive, scalable multi-robot interfaces suitable for real-world applications in logistics, disaster response, and automated warehousing.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

References

- Blake, J. Multitouch on Windows; Manning Publications: 5260 Mac Drive, Grand Forks, ND 58201, 2010. Excerpted on http://nui.joshland.org/2010/03/what-is-natural-user-interface-book.html.

- Wobbrock, J.O.; Morris, M.R.; Wilson, A.D. User-defined gestures for surface computing. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems. ACM, 2009, pp. 1083–1092.

- Vanacken, D.; Demeure, A.; Luyten, K.; Coninx, K. Ghosts in the interface: Meta-user interface visualizations as guides for multi-touch interaction. In Proceedings of the Horizontal Interactive Human Computer Systems, 2008. TABLETOP 2008. 3rd IEEE International Workshop on. IEEE, 2008, pp. 81–84.

- Freeman, D.; Benko, H.; Morris, M.R.; Wigdor, D. ShadowGuides: visualizations for in-situ learning of multi-touch and whole-hand gestures. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the ACM International Conference on Interactive Tabletops and Surfaces. ACM, 2009, pp. 165–172.

- Micire, M.; Desai, M.; Courtemanche, A.; Tsui, K.M.; Yanco, H.A. Analysis of Natural Gestures for Controlling Robot Teams on Multi-touch Tabletop Surfaces. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the ACM International Conference on Interactive Tabletops and Surfaces, New York, NY, USA, 2009; ITS ’09, pp. 41–48. [CrossRef]

- Ayanian, N.; Spielberg, A.; Arbesfeld, M.; Strauss, J.; Rus, D. Controlling a team of robots with a single input. In Proceedings of the Robotics and Automation (ICRA), 2014 IEEE International Conference on. IEEE, 2014, pp. 1755–1762.

- Yao, J.; Fernando, T.; Wang, H. A multi-touch natural user interface framework. In Proceedings of the Systems and Informatics (ICSAI), 2012 International Conference on. IEEE, 2012, pp. 499–504.

- Ehn, P.; Kyng, M. Cardboard Computers: Mocking-it-up or Hands-on the Future. In Proceedings of the Design at work. L. Erlbaum Associates Inc., 1992, pp. 169–196.

- Quigley, M.; Conley, K.; Gerkey, B.P.; Faust, J.; Foote, T.; Leibs, J.; Wheeler, R.; Ng, A.Y. ROS: an open-source Robot Operating System. In Proceedings of the ICRA Workshop on Open Source Software, 2009.

Table 1.

Task Allocation by Swarm Size.

Table 1.

Task Allocation by Swarm Size.

| Task |

1–2 |

10 |

100 |

1000 |

Abstract |

| Navigate to Area A |

x |

x |

x |

x |

x |

| Navigate with Obstacle |

x |

x |

x |

x |

x |

| Halt Movement |

x |

x |

x |

x |

x |

| Split Around Obstacle |

|

x |

x |

x |

x |

| Assign Orange to B, Red to A |

x |

x |

x |

x |

x |

| Assign Orange to A, Red to B |

x |

x |

x |

x |

x |

| Assign Mixed Colors |

x |

x |

x |

x |

x |

| Divide Group |

x |

x |

x |

x |

x |

| Merge Groups |

|

x |

x |

x |

x |

| Form a Line |

|

x |

x |

x |

x |

| Form a Square |

|

x |

x |

x |

x |

| Transport Object to A |

x |

x |

x |

x |

x |

| Transport Object (Dispersed) |

x |

x |

x |

x |

x |

| Identify Defective Robot |

x |

x |

x |

x |

|

| Remove Defective Robot |

x |

x |

x |

x |

|

| Patrol Border |

x |

x |

x |

x |

x |

| Patrol Area A |

x |

x |

x |

x |

x |

| Disperse Across Screen |

x |

x |

x |

x |

x |

Table 2.

Performance comparison on the BraTS 2021 dataset using Dice score, Sensitivity, Specificity, and PPV. The proposed SSM-based model (Mamba) outperforms existing methods.

Table 2.

Performance comparison on the BraTS 2021 dataset using Dice score, Sensitivity, Specificity, and PPV. The proposed SSM-based model (Mamba) outperforms existing methods.

| Model |

Dice ↑ |

Sens. ↑ |

Spec. ↑ |

PPV ↑ |

| U-Net |

0.854 |

0.877 |

0.912 |

0.838 |

| TransUNet |

0.881 |

0.884 |

0.926 |

0.867 |

| SMaTE |

0.888 |

0.889 |

0.929 |

0.872 |

| SSM (Mamba) |

0.902 |

0.912 |

0.941 |

0.885 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).