Submitted:

20 August 2024

Posted:

21 August 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

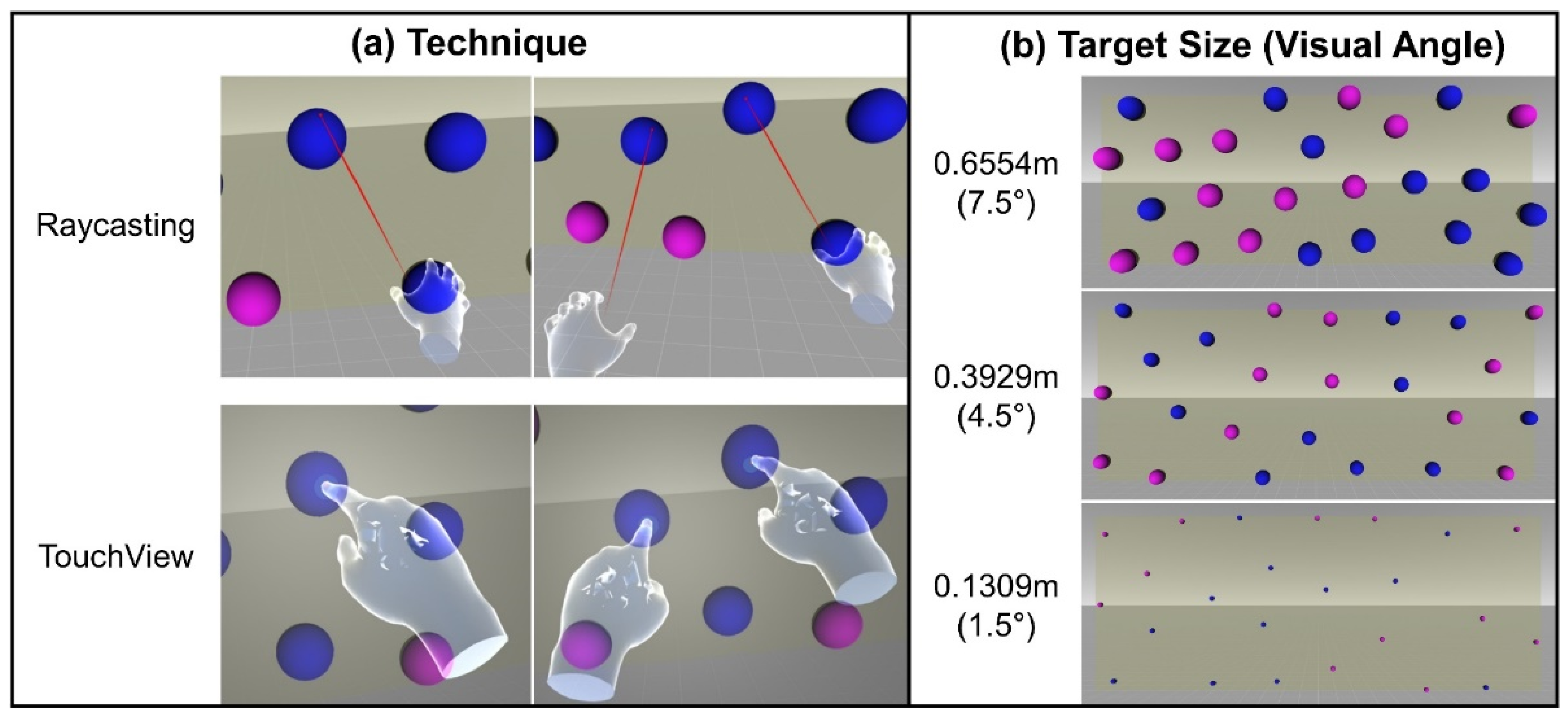

2. Techniques

2.1. Hybrid Ray

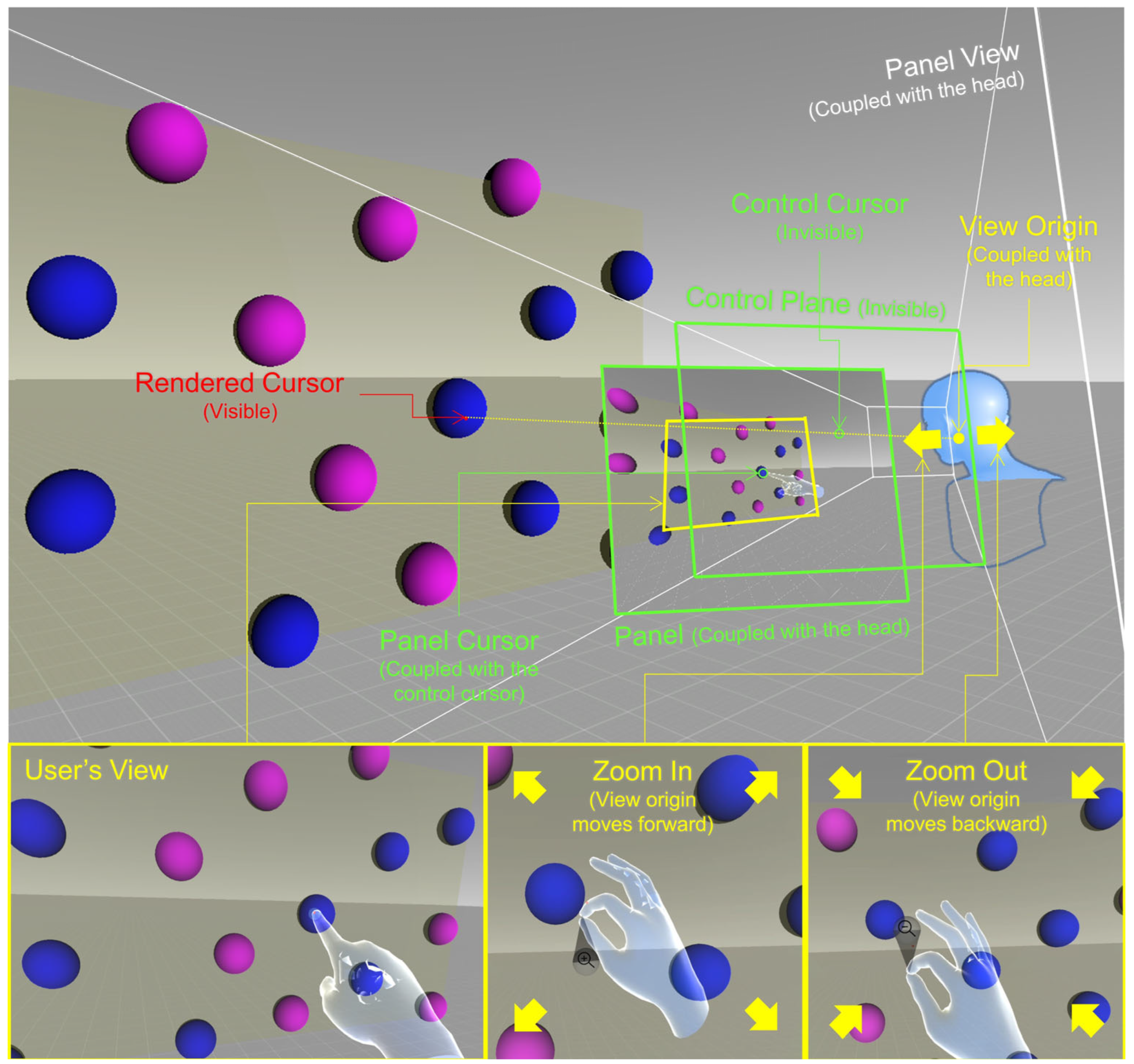

2.2. TouchView

3. User Study and Data Analysis Methods

3.1. Participants

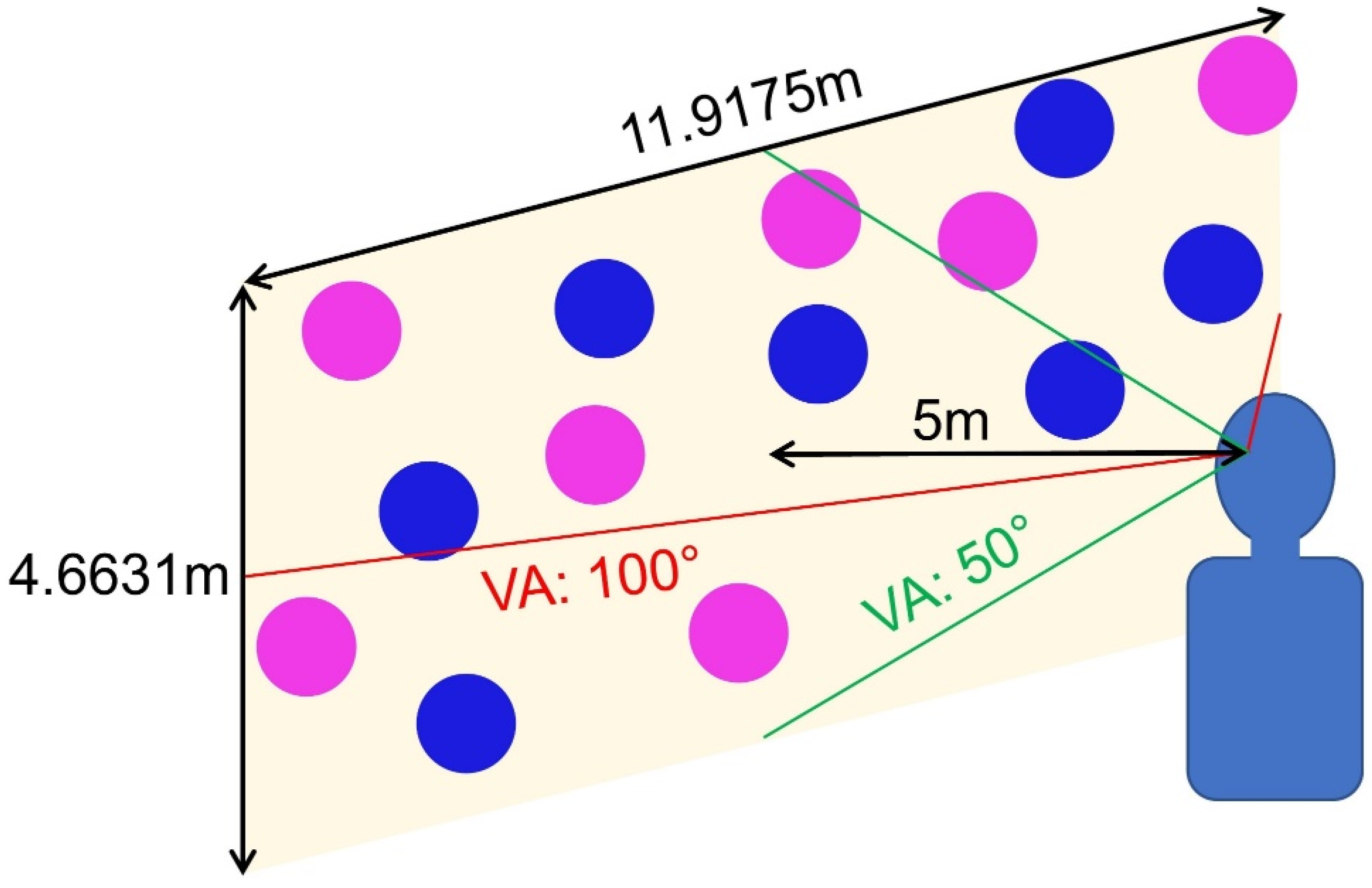

3.2. Experimental Settings

3.3. Experimental Design and Procedure

3.4. Data Analysis

4. Results

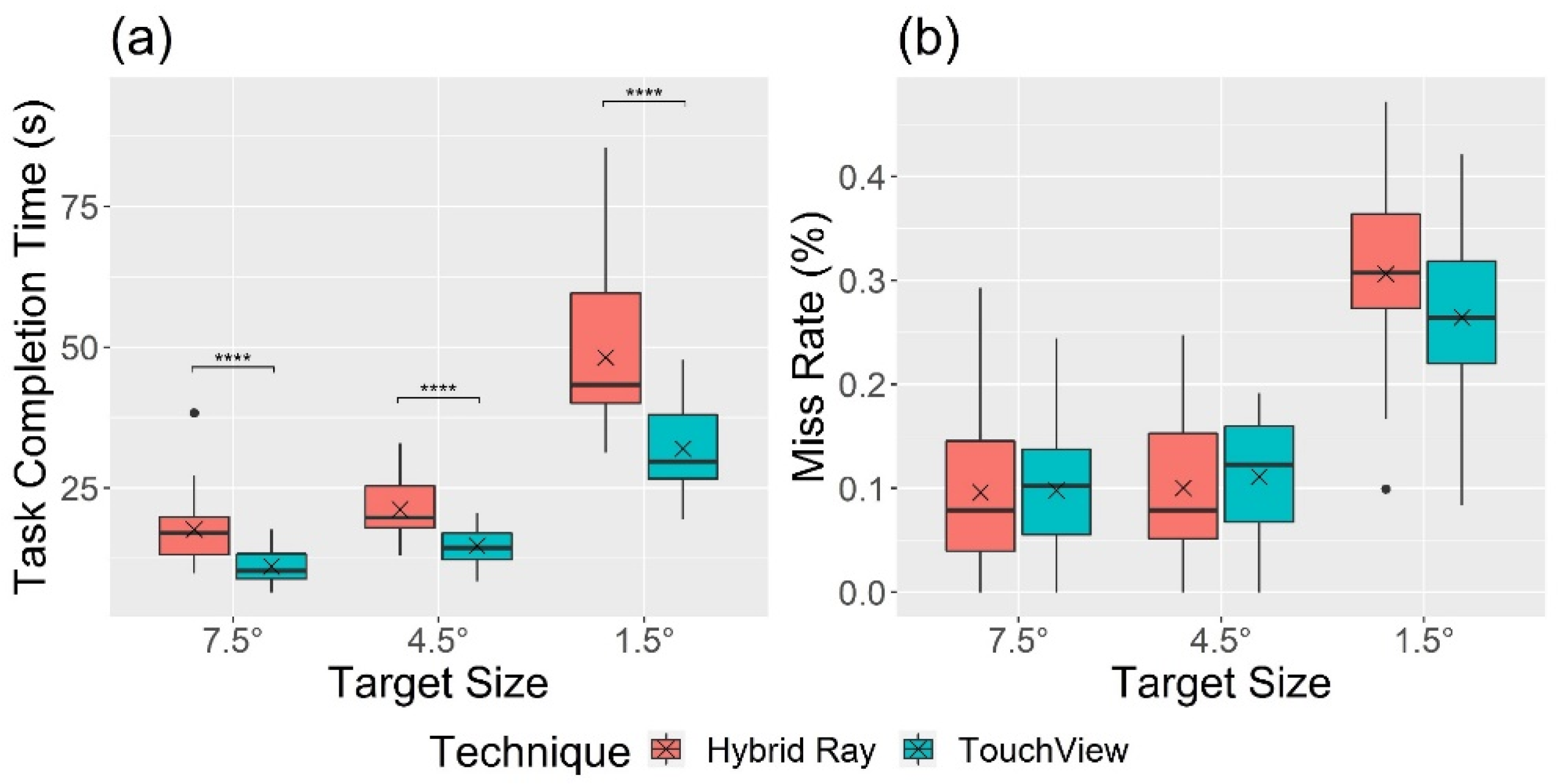

4.1. Performance

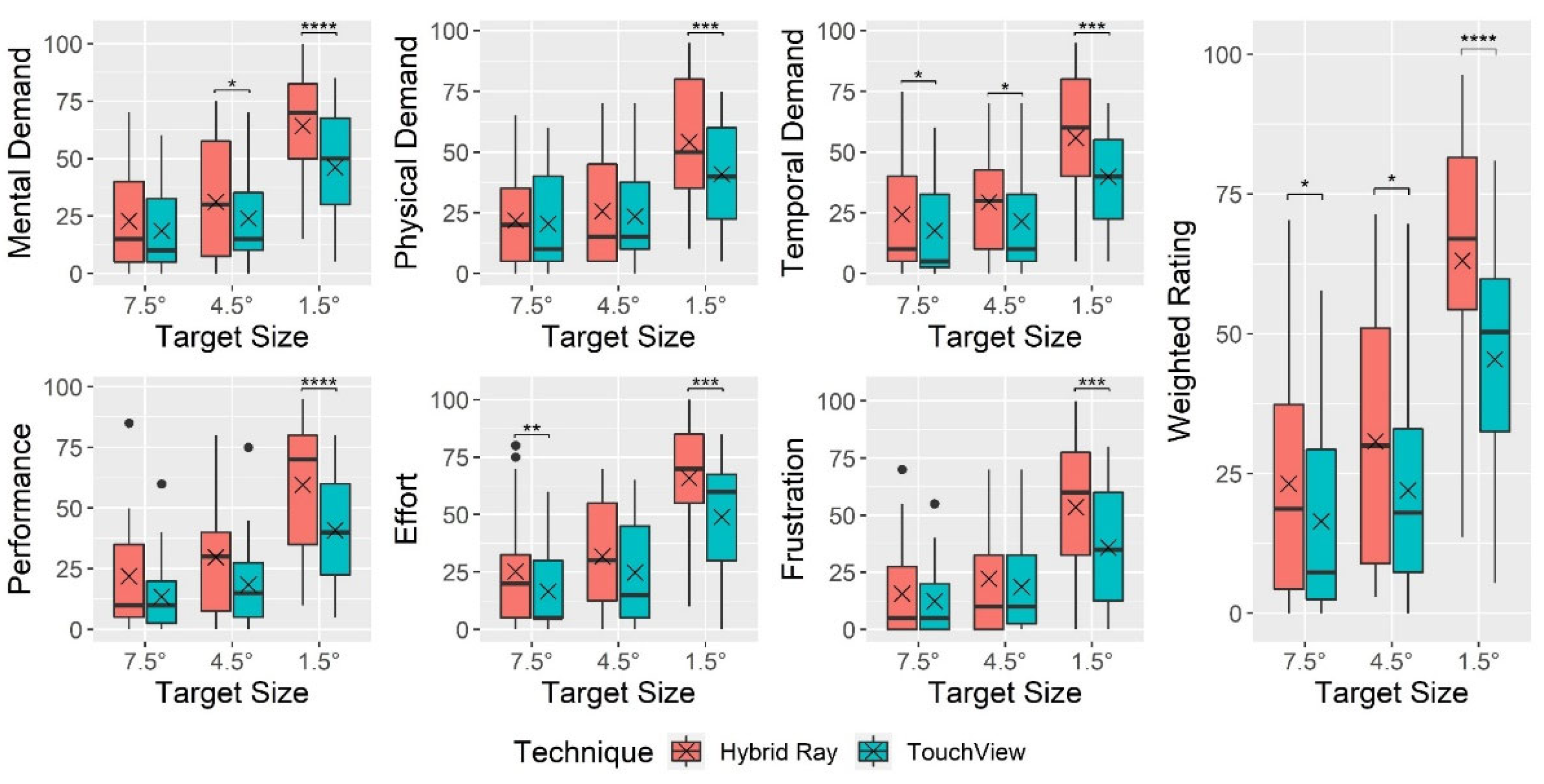

4.2. Perceived Workload

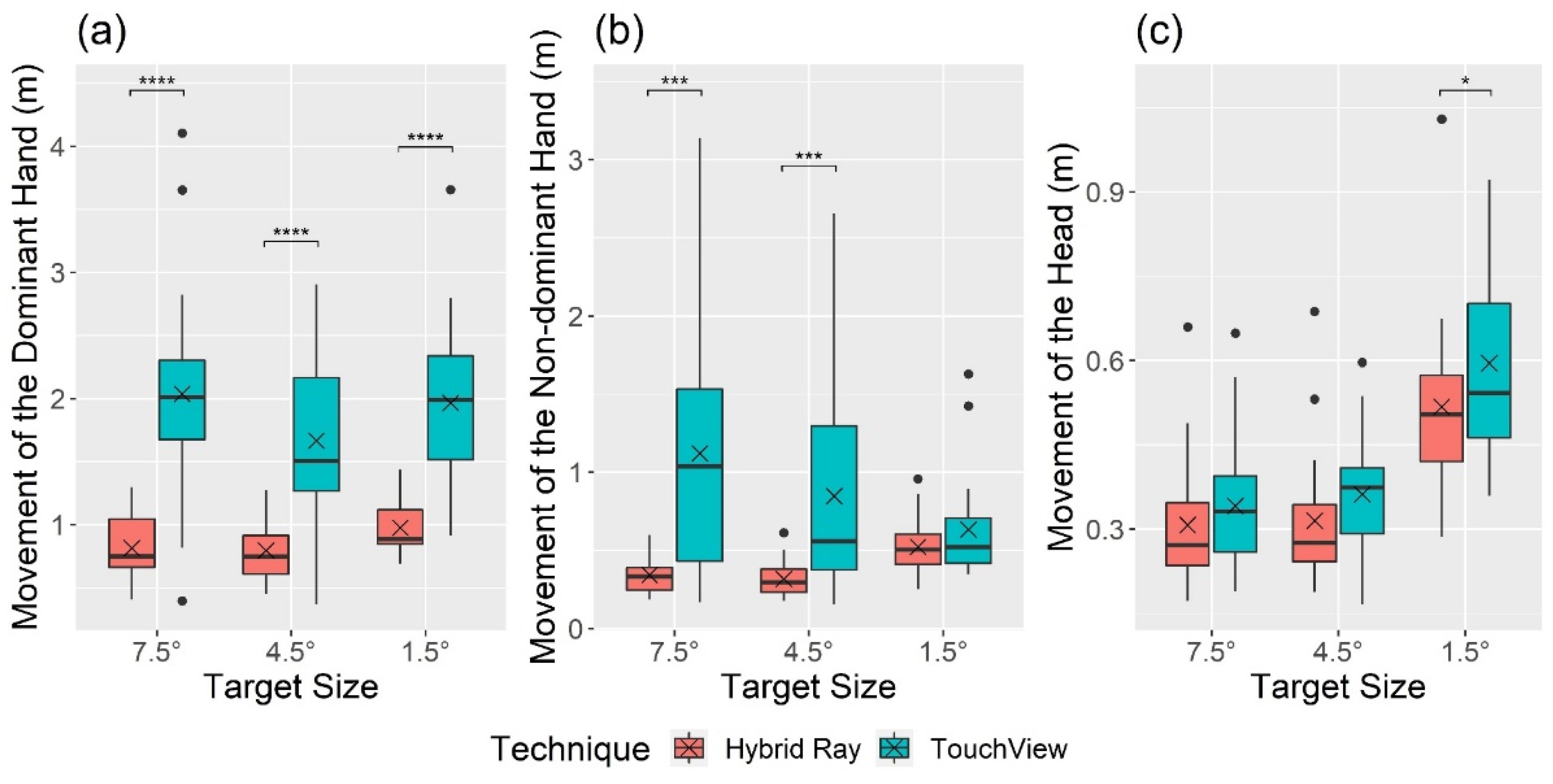

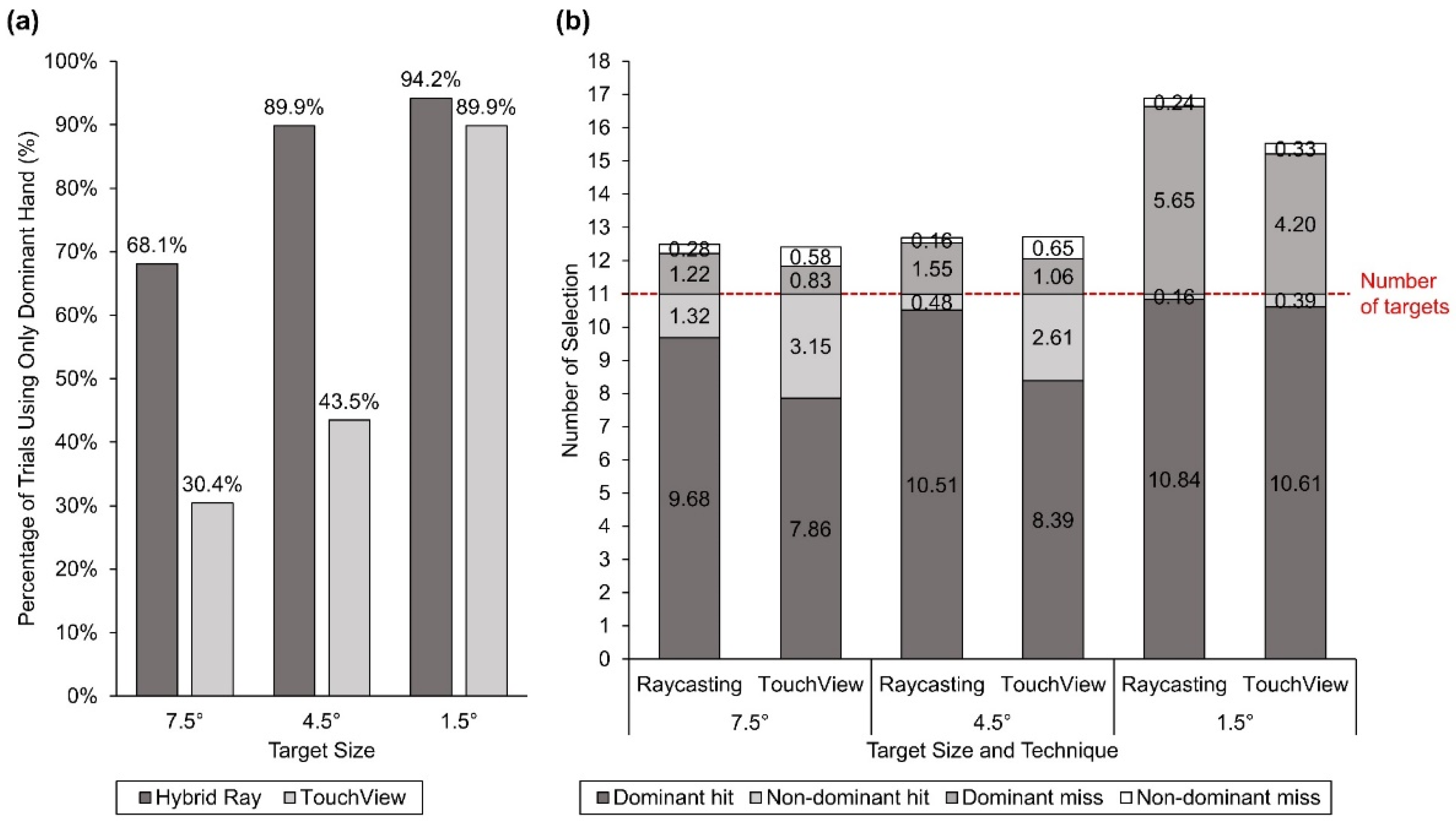

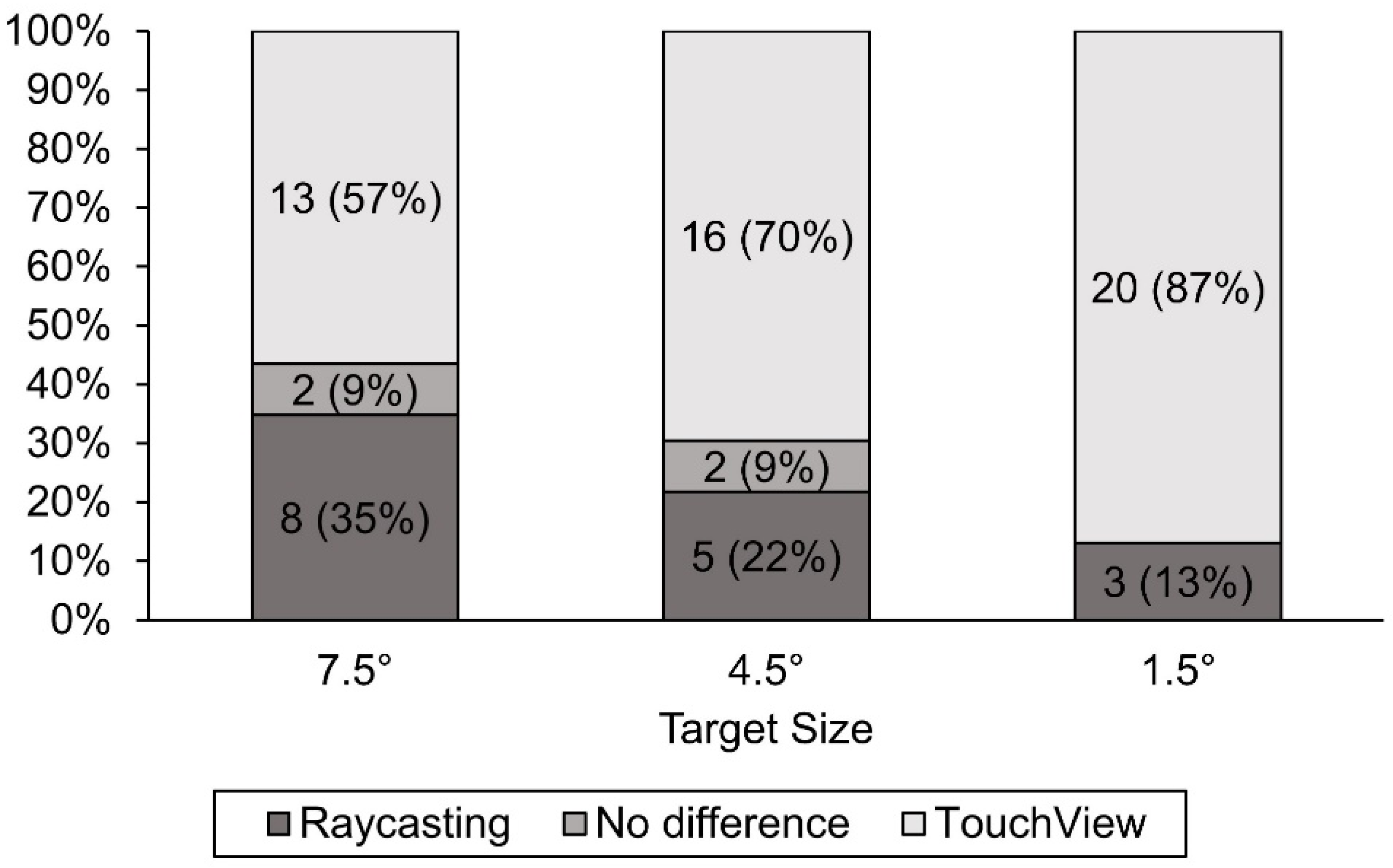

4.3. User Behavior and Preference

5. Discussion

5.1. Main Findings

5.2. Limitations and Future Work

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Measures | Source of variation | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TQ | TS | TQ×TS | |||||||

| F | p | F | p | F | p | ||||

| Task completion time (s) | 45.19 | ***<0.001 | 0.290 | 213.62 | ***<0.001 | 0.689 | 9.88 | **0.003 | 0.082 |

| Miss rate (%) | 0.66 | 0.425 | 0.005 | 175.49 | ***<0.001 | 0.597 | 3.04 | 0.058 | 0.025 |

| Mental demand | 24.24 | ***<0.001 | 0.046 | 59.97 | ***<0.001 | 0.305 | 6.29 | **0.004 | 0.017 |

| Physical demand | 6.45 | *0.019 | 0.016 | 36.80 | ***<0.001 | 0.226 | 5.17 | **0.010 | 0.015 |

| Temporal demand | 20.13 | ***<0.001 | 0.049 | 44.71 | ***<0.001 | 0.213 | 2.81 | 0.071 | 0.008 |

| Performance | 12.74 | **0.002 | 0.082 | 53.48 | ***<0.001 | 0.299 | 2.28 | 0.114 | 0.010 |

| Effort | 15.01 | ***<0.001 | 0.054 | 60.50 | ***<0.001 | 0.324 | 2.32 | 0.110 | 0.009 |

| Frustration | 0.78 | **0.003 | 0.030 | 47.68 | ***<0.001 | 0.245 | 6.66 | **0.003 | 0.021 |

| Weighted rating | 21.74 | ***<0.001 | 0.069 | 77.21 | ***<0.001 | 0.350 | 4.47 | *0.017 | 0.013 |

| D hand movement (m) | 71.68 | ***<0.001 | 0.484 | 3.80 | *0.030 | 0.037 | 2.03 | 0.143 | 0.019 |

| ND hand movement (m) | 23.18 | ***<0.001 | 0.215 | 2.67 | 0.080 | 0.024 | 11.43 | ***<0.001 | 0.084 |

| Head movement (m) | 7.60 | *0.012 | 0.042 | 80.76 | ***<0.001 | 0.413 | 1.04 | 0.364 | 0.005 |

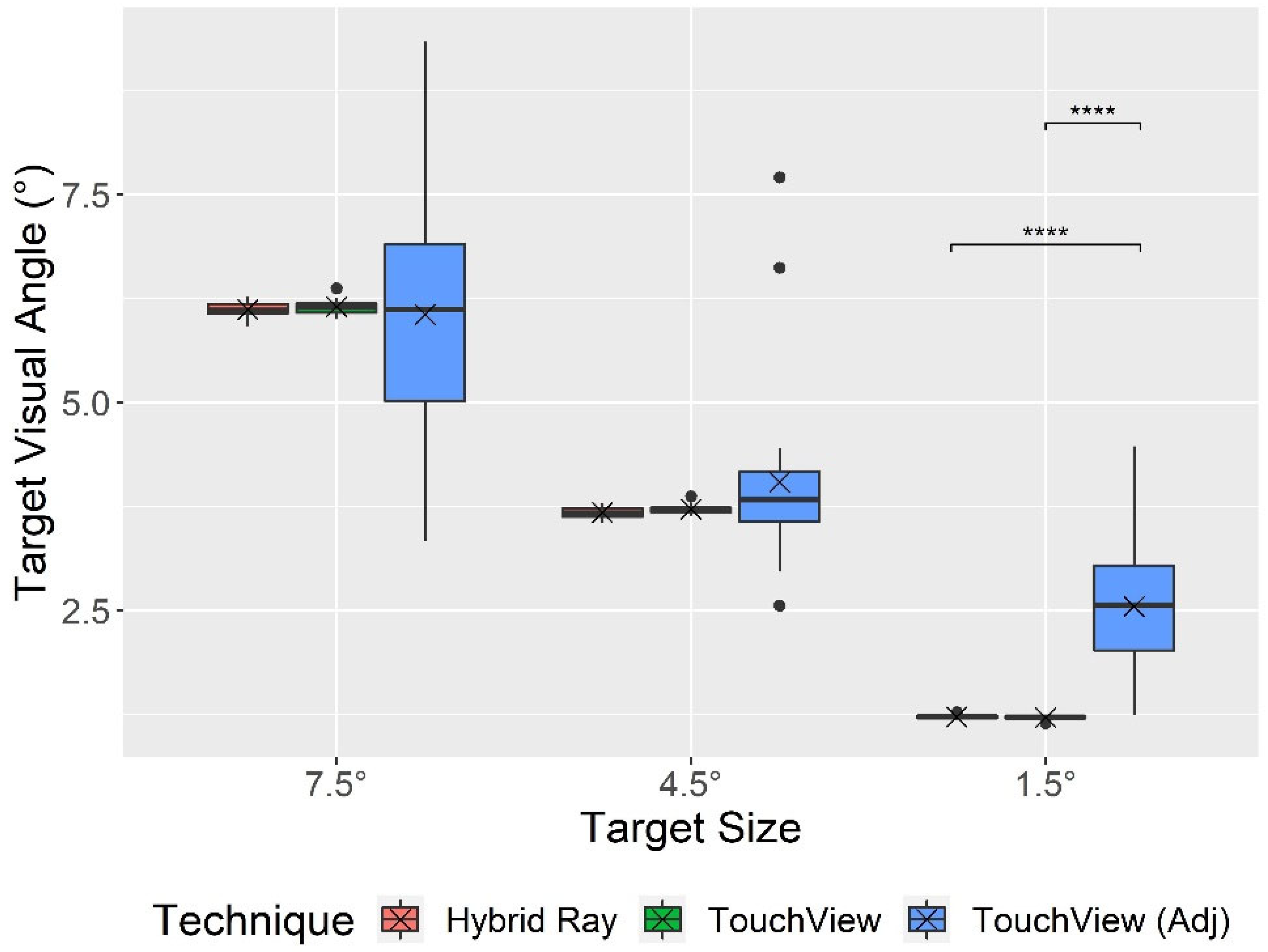

| Target VA (°) | 10.54 | **0.004 | 0.132 | 991.50 | ***<0.001 | 0.888 | 11.40 | ***<0.001 | 0.156 |

| Measures | Hybrid Ray | TouchView | ||||||

| All | 7.5° | 4.5° | 1.5° | All | 7.5° | 4.5° | 1.5° | |

| Task completion time (s) | 29.0 (16.8) |

17.7 (6.58) |

21.2 (5.56) |

48.2 (14.6) |

19.3 (10.5) |

11.1 (3.14) |

14.7 (3.28) |

32.0 (7.64) |

| Miss rate (%) | 16.8 (12.6) |

9.6 (8.0) |

10.0 (7.1) |

30.6 (8.4) |

15.8 (10.0) |

9.8 (6.2) |

11.1 (5.8) |

26.4 (7.8) |

| Mental demand | 39.3 (30.1) |

22.8 (23.2) |

31.1 (25.2) |

64.1 (24.9) |

29.5 (24.3) |

18.5 (19.7) |

23.9 (20.8) |

46.1 (23.5) |

| Physical demand | 33.8 (27.0) |

21.7 (20.9) |

25.7 (21.7) |

54.1 (26.3) |

28.3 (22.9) |

20.4 (20.7) |

23.5 (20.6) |

40.9 (22.5) |

| Temporal demand | 36.5 (28.0) |

24.3 (23.5) |

29.3 (23.4) |

55.9 (26.8) |

26.3 (23.3) |

17.6 (20.4) |

21.5 (22.5) |

39.8 (21.4) |

| Performance | 37.1 (29.5) |

22.0 (21.5) |

29.8 (25.9) |

59.6 (27.0) |

24.3 (21.9) |

13.5 (15.8) |

18.5 (17.8) |

40.9 (21.7) |

| Effort | 40.9 (30.2) |

25.2 (24.3) |

31.7 (24.4) |

65.9 (25.3) |

30.1 (25.6) |

16.5 (18.4) |

24.8 (23.3) |

48.9 (23.4) |

| Frustration | 30.4 (30.2) |

15.7 (21.1) |

22.2 (24.4) |

53.5 (30.5) |

22.3 (23.5) |

12.4 (16.8) |

18.7 (21.3) |

35.9 (25.7) |

| Weighted rating | 39.0 (28.3) |

23.2 (21.6) |

30.7 (22.8) |

63.1 (23.4) |

27.9 (22.4) |

16.4 (17.6) |

22.0 (18.9) |

45.4 (19.8) |

| D hand movement (m) | 0.86 (0.25) |

0.82 (0.27) |

0.80 (0.24) |

0.98 (0.22) |

1.89 (0.74) |

2.04 (0.83) |

1.67 (0.72) |

1.97 (0.62) |

| ND hand movement (m) | 0.39 (0.16) |

0.34 (0.13) |

0.32 (0.11) |

0.52 (0.16) |

0.87 (0.66) |

1.12 (0.85) |

0.85 (0.63) |

0.63 (0.32) |

| Head movement (m) | 0.38 (0.16) |

0.31 (0.12) |

0.32 (0.12) |

0.52 (0.15) |

0.43 (0.17) |

0.34 (0.11) |

0.36 (0.10) |

0.60 (0.17) |

| Original target VA (°) | 3.68 (2.01) |

6.12 (0.09) |

3.68 (0.07) |

1.23 (0.02) |

3.70 (2.03) |

6.15 (0.09) |

3.72 (0.05) |

1.22 (0.03) |

| Adjusted target VA (°) | NA | NA | NA | NA | 4.22 (1.83) |

6.06 (1.43) |

4.04 (1.10) |

2.55 (0.80) |

References

- LaViola, J.J., Jr.; Kruijff, E.; McMahan, R.P.; Bowman, D.; Poupyrev, I.P. 3D User Interfaces: Theory and Practice, 2nd ed.; Addison-Wesley Professional: Boston, MA, 2017; ISBN 0134034325. [Google Scholar]

- Bowman, D.A.; Hodges, L.F. An Evaluation of Techniques for Grabbing and Manipulating Remote Objects in Immersive Virtual Environments. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 1997 symposium on Interactive 3D graphics - SI3D ’97; ACM Press: New York, New York, USA, 1997; p. 35-ff. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, S.; Seo, J.; Kim, G.J.; Park, C.-M. Evaluation of Pointing Techniques for Ray Casting Selection in Virtual Environments. In Proceedings of the Third International Conference on Virtual Reality and Its Application in Industry; Pan, Z., Shi, J., Eds.; 4 April 2003; pp. 38–44. [Google Scholar]

- Andujar, C.; Argelaguet, F. Anisomorphic Ray-Casting Manipulation for Interacting with 2D GUIs. Comput Graph 2007, 31, 15–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bacim, F.; Kopper, R.; Bowman, D.A. Design and Evaluation of 3D Selection Techniques Based on Progressive Refinement. Int J Hum Comput Stud 2013, 71, 785–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindeman, R.W.; Sibert, J.L.; Hahn, J.K. Hand-Held Windows: Towards Effective 2D Interaction in Immersive Virtual Environments. In Proceedings of the Proceedings IEEE Virtual Reality (Cat. No. 99CB36316); IEEE Comput. Soc; 1999; pp. 205–212. [Google Scholar]

- Steed, A.; Parker, C. 3d Selection Strategies for Head Tracked and Non-Head Tracked Operation of Spatially Immersive Displays. In Proceedings of the 8th International Immersive Projection Technology Workshop; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Brasier, E.; Chapuis, O.; Ferey, N.; Vezien, J.; Appert, C. ARPads: Mid-Air Indirect Input for Augmented Reality. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE International Symposium on Mixed and Augmented Reality (ISMAR), IEEE, November 2020; pp. 332–343. [Google Scholar]

- Herndon, K.P.; van Dam, A.; Gleicher, M. The Challenges of 3D Interaction. ACM SIGCHI Bulletin 1994, 26, 36–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cockburn, A.; Quinn, P.; Gutwin, C.; Ramos, G.; Looser, J. Air Pointing: Design and Evaluation of Spatial Target Acquisition with and without Visual Feedback. Int J Hum Comput Stud 2011, 69, 401–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Yu, C.; Shi, Y. Investigating Bubble Mechanism for Ray-Casting to Improve 3D Target Acquisition in Virtual Reality. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE Conference on Virtual Reality and 3D User Interfaces (VR), IEEE, March 2020; pp. 35–43. [Google Scholar]

- Bowman, D.A.; Wingrave, C.; Campbell, J.; Ly, V. Using Pinch Gloves (TM) for Both Natural and Abstract Interaction Techniques in Virtual Environments; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Wolf, D.; Gugenheimer, J.; Combosch, M.; Rukzio, E. Understanding the Heisenberg Effect of Spatial Interaction: A Selection Induced Error for Spatially Tracked Input Devices. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2020 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems; ACM: New York, NY, USA, April 21, 2020; pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Weise, M.; Zender, R.; Lucke, U. How Can I Grab That?: Solving Issues of Interaction in VR by Choosing Suitable Selection and Manipulation Techniques. i-com 2020, 19, 67–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batmaz, A.U.; Seraji, M.R.; Kneifel, J.; Stuerzlinger, W. No Jitter Please: Effects of Rotational and Positional Jitter on 3D Mid-Air Interaction. In Proceedings of the Future Technologies Conference (FTC) 2020, Volume 2. FTC 2020. Advances in Intelligent Systems and Computing, vol 1289; Arai, K., Kapoor, S., Bhatia, R., Eds.; 2021; pp. 792–808. [Google Scholar]

- Liang, J.; Green, M. JDCAD: A Highly Interactive 3D Modeling System. Comput Graph 1994, 18, 499–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forsberg, A.; Herndon, K.; Zeleznik, R. Aperture Based Selection for Immersive Virtual Environments. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 9th annual ACM symposium on User interface software and technology - UIST ’96; ACM Press: New York, New York, USA, 1996; pp. 95–96. [Google Scholar]

- Kopper, R.; Bacim, F.; Bowman, D.A. Rapid and Accurate 3D Selection by Progressive Refinement. In Proceedings of the 3DUI 2011 - IEEE Symposium on 3D User Interfaces 2011, Proceedings; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Cashion, J.; Wingrave, C.; LaViola, J.J. Dense and Dynamic 3D Selection for Game-Based Virtual Environments. IEEE Trans Vis Comput Graph 2012, 18, 634–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baloup, M.; Pietrzak, T.; Casiez, G. RayCursor: A 3D Pointing Facilitation Technique Based on Raycasting. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2019 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2 May 2019; pp. 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Grossman, T.; Balakrishnan, R. The Design and Evaluation of Selection Techniques for 3D Volumetric Displays. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 19th annual ACM symposium on User interface software and technology - UIST ’06; ACM Press: New York, New York, USA, 2006; p. 3. [Google Scholar]

- Wingrave, C.A.; Bowman, D.A.; Ramakrishnan, N. Towards Preferences in Virtual Environment Interfaces. Proceedings of the 8th EGVE 2002, 63–72. [Google Scholar]

- Steinicke, F.; Ropinski, T.; Hinrichs, K. Object Selection in Virtual Environments Using an Improved Virtual Pointer Metaphor. In Computer Vision and Graphics; Kluwer Academic Publishers: Dordrecht, 2006; pp. 320–326. [Google Scholar]

- Cashion, J.; Wingrave, C.; LaViola, J.J. Optimal 3D Selection Technique Assignment Using Real-Time Contextual Analysis. In Proceedings of the 2013 IEEE Symposium on 3D User Interfaces (3DUI), IEEE, March 2013; pp. 107–110. [Google Scholar]

- Grossman, T.; Balakrishnan, R. The Bubble Cursor: Enhancing Target Acquisition by Dynamic of the Cursor’s Activation Area. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the SIGCHI conference on Human factors in computing systems - CHI ’05; ACM Press: New York, New York, USA, 2005; p. 281. [Google Scholar]

- Vanacken, L.; Grossman, T.; Coninx, K. Exploring the Effects of Environment Density and Target Visibility on Object Selection in 3D Virtual Environments. In Proceedings of the 2007 IEEE Symposium on 3D User Interfaces; IEEE; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Krüger, M.; Gerrits, T.; Römer, T.; Kuhlen, T.; Weissker, T. IntenSelect+: Enhancing Score-Based Selection in Virtual Reality. IEEE Trans Vis Comput Graph 2024, 30, 2829–2838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vogel, D.; Balakrishnan, R. Distant Freehand Pointing and Clicking on Very Large, High Resolution Displays. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 18th annual ACM symposium on User interface software and technology - UIST ’05; ACM Press: New York, New York, USA, 2005; p. 33. [Google Scholar]

- Kopper, R.; Bowman, D.A.; Silva, M.G.; McMahan, R.P. A Human Motor Behavior Model for Distal Pointing Tasks. Int J Hum Comput Stud 2010, 68, 603–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frees, S.; Kessler, G.D.; Kay, E. PRISM Interaction for Enhancing Control in Immersive Virtual Environments. ACM Transactions on Computer-Human Interaction 2007, 14, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- König, W.A.; Gerken, J.; Dierdorf, S.; Reiterer, H. Adaptive Pointing – Design and Evaluation of a Precision Enhancing Technique for Absolute Pointing Devices. In Lecture Notes in Computer Science (including subseries Lecture Notes in Artificial Intelligence and Lecture Notes in Bioinformatics); 2009; pp. 658–671. ISBN 3642036546. [Google Scholar]

- Gallo, L.; Ciampi, M.; Minutolo, A. Smoothed Pointing: A User-Friendly Technique for Precision Enhanced Remote Pointing. In Proceedings of the 2010 International Conference on Complex, Intelligent and Software Intensive Systems; IEEE, February 2010; pp. 712–717. [Google Scholar]

- Foley, J.M.; Held, R. Visually Directed Pointing as a Function of Target Distance, Direction, and Available Cues. Percept Psychophys 1972, 12, 263–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, S.; Schwind, V.; Schweigert, R.; Henze, N. The Effect of Offset Correction and Cursor on Mid-Air Pointing in Real and Virtual Environments. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2018 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems; ACM: New York, NY, USA, April 21, 2018; pp. 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Plaumann, K.; Weing, M.; Winkler, C.; Müller, M.; Rukzio, E. Towards Accurate Cursorless Pointing: The Effects of Ocular Dominance and Handedness. Pers Ubiquitous Comput 2018, 22, 633–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoakley, R.; Conway, M.J.; Pausch, R. Virtual Reality on a WIM: Interactive Worlds in Miniature. In Proceedings of the Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems - Proceedings, 1995; Vol. 1, pp. 265–272. [Google Scholar]

- Pierce, J.S.; Stearns, B.C.; Pausch, R. Voodoo Dolls: Seamless Interaction at Multiple Scales in Virtual Environments. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 1999 symposium on Interactive 3D graphics - SI3D ’99; ACM Press: New York, New York, USA, 1999; pp. 141–145. [Google Scholar]

- Wingrave, C.A.; Haciahmetoglu, Y.; Bowman, D.A. Overcoming World in Miniature Limitations by a Scaled and Scrolling WIM. In Proceedings of the 3D User Interfaces (3DUI’06), IEEE; 2006; pp. 11–16. [Google Scholar]

- Bowman, D.A.; Koller, D.; Hodges, L.F. Travel in Immersive Virtual Environments: An Evaluation of Viewpoint Motion Control Techniques. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of IEEE 1997 Annual International Symposium on Virtual Reality; IEEE Comput. Soc. Press; 1997; pp. 45–52. [Google Scholar]

- Pohl, H.; Lilija, K.; McIntosh, J.; Hornbæk, K. Poros: Configurable Proxies for Distant Interactions in VR. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2021 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems; ACM: New York, NY, USA, May 6, 2021; pp. 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Schjerlund, J.; Hornbæk, K.; Bergström, J. Ninja Hands: Using Many Hands to Improve Target Selection in VR. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2021 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems; ACM: New York, NY, USA, May 6, 2021; pp. 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Broussard, D.; Borst, C.W. Tether-Handle Interaction for Retrieving Out-of-Range Objects in VR. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE Conference on Virtual Reality and 3D User Interfaces Abstracts and Workshops (VRW), IEEE, March 2023; pp. 707–708. [Google Scholar]

- Natapov, D.; MacKenzie, I.S. The Trackball Controller: Improving the Analog Stick. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the International Academic Conference on the Future of Game Design and Technology - Futureplay ’10; ACM Press: New York, New York, USA, 2010; p. 175. [Google Scholar]

- Pierce, J.S.; Forsberg, A.S.; Conway, M.J.; Hong, S.; Zeleznik, R.C.; Mine, M.R. Image Plane Interaction Techniques in 3D Immersive Environments. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 1997 symposium on Interactive 3D graphics - SI3D ’97; ACM Press: New York, New York, USA, 1997; p. 39-ff. [Google Scholar]

- Teather, R.J.; Stuerzlinger, W. Pointing at 3d Target Projections with One-Eyed and Stereo Cursors. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems - CHI ’13; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Ware, C.; Lowther, K. Selection Using a One-Eyed Cursor in a Fish Tank VR Environment. ACM Transactions on Computer-Human Interaction 1997, 4, 309–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramcharitar, A.; Teather, R. EZCursorVR: 2D Selection with Virtual Reality Head-Mounted Displays. In Proceedings of the Proceedings - Graphics Interface; 2018; pp. 114–121. [Google Scholar]

- Stoev, S.L.; Schmalstieg, D. Application and Taxonomy of Through-the-Lens Techniques. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the ACM symposium on Virtual reality software and technology - VRST ’02; ACM Press: New York, New York, USA, 2002; p. 57. [Google Scholar]

- Argelaguet, F.; Andujar, C. Visual Feedback Techniques for Virtual Pointing on Stereoscopic Displays. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 16th ACM Symposium on Virtual Reality Software and Technology - VRST ’09; ACM Press: New York, New York, USA, 2009; p. 163. [Google Scholar]

- Clergeaud, D.; Guitton, P. Pano: Design and Evaluation of a 360° through-the-Lens Technique. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE Symposium on 3D User Interfaces (3DUI), IEEE; 2017; pp. 2–11. [Google Scholar]

- Li, N.; Zhang, Z.; Liu, C.; Yang, Z.; Fu, Y.; Tian, F.; Han, T.; Fan, M. VMirror: Enhancing the Interaction with Occluded or Distant Objects in VR with Virtual Mirrors. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2021 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems; ACM: New York, NY, USA, May 6, 2021; pp. 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Surale, H.B.; Gupta, A.; Hancock, M.; Vogel, D. TabletInVR: Exploring the Design Space for Using a Multi-Touch Tablet in Virtual Reality. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2019 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems; ACM: New York, NY, USA, May 2, 2019; pp. 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Mossel, A.; Venditti, B.; Kaufmann, H. DrillSample: Precise Selection in Dense Handheld Augmented Reality Environments. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the Virtual Reality International Conference: Laval Virtual; ACM: New York, NY, USA, March 20, 2013; pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, J.; Fu, C.; Zhang, X.; Liu, T. Precise Target Selection Techniques in Handheld Augmented Reality Interfaces. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 17663–17674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, H.; Lee, G.A.; Billinghurst, M. Freeze View Touch and Finger Gesture Based Interaction Methods for Handheld Augmented Reality Interfaces. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 27th Conference on Image and Vision Computing New Zealand - IVCNZ ’12; ACM Press: New York, New York, USA, 2012; p. 126. [Google Scholar]

- Arshad, H.; Chowdhury, S.A.; Chun, L.M.; Parhizkar, B.; Obeidy, W.K. A Freeze-Object Interaction Technique for Handheld Augmented Reality Systems. Multimed Tools Appl 2016, 75, 5819–5839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergström, J.; Dalsgaard, T.-S.; Alexander, J.; Hornbæk, K. How to Evaluate Object Selection and Manipulation in VR? Guidelines from 20 Years of Studies. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2021 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems; ACM: New York, NY, USA, May 6, 2021; pp. 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Henrikson, R.; Grossman, T.; Trowbridge, S.; Wigdor, D.; Benko, H. Head-Coupled Kinematic Template Matching: A Prediction Model for Ray Pointing in VR. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2020 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems; ACM: New York, NY, USA, April 21, 2020; pp. 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, D.; Liang, H.-N.; Lu, X.; Fan, K.; Ens, B. Modeling Endpoint Distribution of Pointing Selection Tasks in Virtual Reality Environments. ACM Trans Graph 2019, 38, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meta Raycasting. Available online: https://developer.oculus.com/resources/hands-design-bp/#raycasting (accessed on 15 May 2024).

- Kim, W.; Xiong, S. ViewfinderVR: Configurable Viewfinder for Selection of Distant Objects in VR. Virtual Real 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berwaldt, N.L.P.; Di Domenico, G.; Pozzer, C.T. Virtual MultiView Panels for Distant Object Interaction and Navigation in Virtual Reality. In Proceedings of the Symposium on Virtual and Augmented Reality; ACM: New York, NY, USA, November 6, 2023; pp. 88–95. [Google Scholar]

- Jota, R.; Nacenta, M.A.; Jorge, J.A.; Carpendale, S.; Greenberg, S. A Comparison of Ray Pointing Techniques for Very Large Displays. In Proceedings of the Proceedings - Graphics Interface; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Alsop, T. Extended Reality (XR) Headset Vendor Shipment Share Worldwide from 2020 to 2023, by Quarter. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/1222146/xr-headset-shipment-share-worldwide-by-brand/ (accessed on 14 May 2024).

- Shin, G.; Zhu, X. User Discomfort, Work Posture and Muscle Activity While Using a Touchscreen in a Desktop PC Setting. Ergonomics 2011, 54, 733–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penumudi, S.A.; Kuppam, V.A.; Kim, J.H.; Hwang, J. The Effects of Target Location on Musculoskeletal Load, Task Performance, and Subjective Discomfort during Virtual Reality Interactions. Appl Ergon 2020, 84, 103010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, M.Y.; Barbir, A.; Dennerlein, J.T. Evaluating Biomechanics of User-Selected Sitting and Standing Computer Workstation. Appl Ergon 2017, 65, 382–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, S.; Liu, B.; Cabezas, R.; Twigg, C.D.; Zhang, P.; Petkau, J.; Yu, T.-H.; Tai, C.-J.; Akbay, M.; Wang, Z.; et al. MEgATrack: Monochrome Egocentric Articulated Hand-Tracking for Virtual Reality. ACM Trans Graph 2020, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kin, K.; Agrawala, M.; DeRose, T. Determining the Benefits of Direct-Touch, Bimanual, and Multifinger Input on a Multitouch Workstation. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of Graphics Interface 2009 (GI ’09); Canadian Information Processing Society; 2009; pp. 119–124. [Google Scholar]

- Poupyrev, I.; Ichikawa, T.; Weghorst, S.; Billinghurst, M. Egocentric Object Manipulation in Virtual Environments: Empirical Evaluation of Interaction Techniques. Computer Graphics Forum 1998, 17, 41–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, A.G.; Hatch, J.G.; Kuehl, S.; McMahan, R.P. VOTE: A Ray-Casting Study of Vote-Oriented Technique Enhancements. International Journal of Human Computer Studies 2018, 120, 36–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hart, S.G.; Staveland, L.E. Development of NASA-TLX (Task Load Index): Results of Empirical and Theoretical Research. In Advances in Psychology; 1988; pp. 139–183.

- Olejnik, S.; Algina, J. Generalized Eta and Omega Squared Statistics: Measures of Effect Size for Some Common Research Designs. Psychol Methods 2003, 8, 434–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McLaughlin, A.C.; Rogers, W.A.; Fisk, A.D. Using Direct and Indirect Input Devices: Attention Demands and Age-Related Differences. ACM Transactions on Computer-Human Interaction 2009, 16, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Charness, N.; Holley, P.; Feddon, J.; Jastrzembski, T. Light Pen Use and Practice Minimize Age and Hand Performance Differences in Pointing Tasks. Human Factors: The Journal of the Human Factors and Ergonomics Society 2004, 46, 373–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murata, A.; Iwase, H. Usability of Touch-Panel Interfaces for Older Adults. Human Factors: The Journal of the Human Factors and Ergonomics Society 2005, 47, 767–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wickens, C. The Structure of Attentional Resources. In Attention and Performance Viii; Nickerson, R.S., Ed.; Psychology Press: New York, NY, USA, 1980 ISBN 9781315802961.

- Jang, S.; Stuerzlinger, W.; Ambike, S.; Ramani, K. Modeling Cumulative Arm Fatigue in Mid-Air Interaction Based on Perceived Exertion and Kinetics of Arm Motion. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2017 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems - CHI ’17; ACM Press: New York, New York, USA, 2017; pp. 3328–3339. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Z.; Vogel, D.; Wallace, J.R. Applying the Cumulative Fatigue Model to Interaction on Large, Multi-Touch Displays. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 7th ACM International Symposium on Pervasive Displays; ACM: New York, NY, USA, June 6, 2018; pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Hincapié-Ramos, J.D.; Guo, X.; Moghadasian, P.; Irani, P. Consumed Endurance: A Metric to Quantify Arm Fatigue of Mid-Air Interactions. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems; ACM: New York, NY, USA, April 26, 2014; pp. 1063–1072. [Google Scholar]

- Watson, D.; Hancock, M.; Mandryk, R.L.; Birk, M. Deconstructing the Touch Experience. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2013 ACM international conference on Interactive tabletops and surfaces; ACM: New York, NY, USA, October 6, 2013; pp. 199–208. [Google Scholar]

- Sears, A.; Shneiderman, B. High Precision Touchscreens: Design Strategies and Comparisons with a Mouse. Int J Man Mach Stud 1991, 34, 593–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forlines, C.; Wigdor, D.; Shen, C.; Balakrishnan, R. Direct-Touch vs. Mouse Input for Tabletop Displays. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems; ACM: New York, NY, USA, April 29, 2007; pp. 647–656. [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy, D.M.; Wang, C.; Wang, Y.; Shea, C.H. The Influence of Accuracy Constraints on Bimanual and Unimanual Sequence Learning. Neurosci Lett 2021, 751, 135812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, C.; Boyle, J.B.; Dai, B.; Shea, C.H. Do Accuracy Requirements Change Bimanual and Unimanual Control Processes Similarly? Exp Brain Res 2017, 235, 1467–1479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helmuth, L.L.; Ivry, R.B. When Two Hands Are Better than One: Reduced Timing Variability during Bimanual Movements. J Exp Psychol Hum Percept Perform 1996, 22, 278–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Drewing, K.; Aschersleben, G. Reduced Timing Variability during Bimanual Coupling: A Role for Sensory Information. The Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology Section A 2003, 56, 329–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corradini, A.; Cohen, P.R. Multimodal Speech-Gesture Interface for Handfree Painting on a Virtual Paper Using Partial Recurrent Neural Networks as Gesture Recognizer. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2002 International Joint Conference on Neural Networks. IJCNN’02 (Cat. No.02CH37290); IEEE, 2002; pp. 2293–2298.

- Yu, D.; Zhou, Q.; Newn, J.; Dingler, T.; Velloso, E.; Goncalves, J. Fully-Occluded Target Selection in Virtual Reality. IEEE Trans Vis Comput Graph 2020, 26, 3402–3413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sidenmark, L.; Clarke, C.; Zhang, X.; Phu, J.; Gellersen, H. Outline Pursuits: Gaze-Assisted Selection of Occluded Objects in Virtual Reality. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2020 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems; ACM: New York, NY, USA, April 21, 2020; pp. 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, J.-J.; Park, J.-M. 3D Mirrored Object Selection for Occluded Objects in Virtual Environments. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 200259–200274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, D.; Biener, V.; Otte, A.; Gesslein, T.; Gagel, P.; Campos, C.; Čopič Pucihar, K.; Kljun, M.; Ofek, E.; Pahud, M.; et al. Accuracy Evaluation of Touch Tasks in Commodity Virtual and Augmented Reality Head-Mounted Displays. In Proceedings of the Symposium on Spatial User Interaction; ACM: New York, NY, USA, November 9, 2021; pp. 1–11. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).