Submitted:

11 June 2025

Posted:

16 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Life Cycle Assessment of Conventional and Bio-Based Lubricants

3. Formulation of MO-Based Blend

4. Experimental Setup

5. Results and Discussion

5.1. Chemical Characterization of Base Oil and Blends

5.2. Rheological Analysis

5.3. Tribological Characteristics

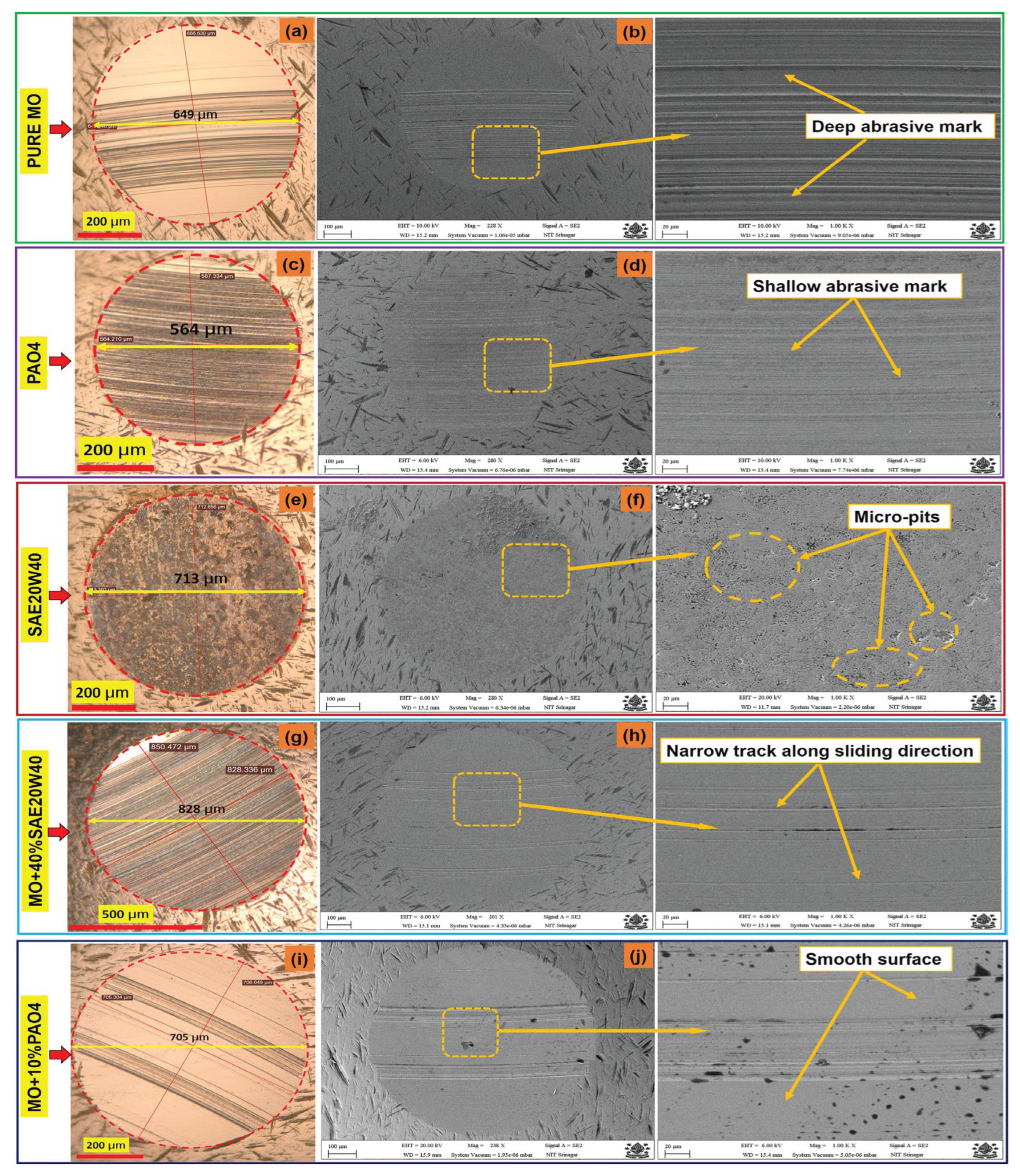

5.4. Worn Surface Analysis

6. Conclusions

- Viscosity measurements indicate that the shear viscosity of MO is significantly higher than that of PAO4 but lower than SAE20W40. The incorporation of SAE20W40 into MO in concentrations ranging from 10 to 40 vol% resulted in a progressive increase in shear viscosity, whereas the addition of PAO4 in MO with the same concentration range led to a reduction in shear viscosity. Despite these variations, the blending of PAO4 and SAE20W40 with MO did not affect its flow characteristics, as all formulations exhibited Newtonian behavior, wherein shear stress maintained a linear relationship with shear rate across all volume concentrations.

- The COF of pure MO was observed to be 52% lower than that of SAE20W40 and 46% lower than PAO4. This reduction in frictional resistance can be attributed to the high concentration of triglyceride fatty acids and naturally occurring polar compounds in MO. These constituents facilitate the formation of a robust protective tribolayer at the contact interface, thereby significantly minimizing friction and enhancing lubrication performance.

- Though the COF of MO+10% PAO4 and MO+40% SAE20W40 was closer to that of pure MO, the addition of 10% PAO4 and 40% SAE20W40 to pure MO demonstrated greater stability in frictional torque and resulted in a smoother wear scar surface, reflecting superior tribological properties in terms of frictional stability and reduced surface damage. Therefore, it can be inferred that these performance improvements are attributed to the combined effects of the interaction between the oil molecules of MO with PAO4 and MO with SAE20W40 as confirmed by FTIR analysis.

- Besides that, it can be also inferred that MO itself acts as an additive for SAE20W40 and PAO4 due to their superior anti-frictional properties according to COF test results. Thus,MO could also serve as an additive (friction modifier) alternative to those chemical additives that are highly toxic to the environment for the formulation of conventional lubricants.These bio-lubricants may be beneficial for several industrial and transportation sectors to contribute the energy savings and pollution reduction.

7. Future Scope

Author Contributions

- ➢

- In the development of lubricants.

- ➢

- Conducted experimental studies to test developed lubricants.

- ➢

- In surface morphological studies and chemical characterization of developed lubricants.

- ➢

- In writing the research paper for publication.

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Holmberg, K.; Andersson, P.; Erdemir, A. Global energy consumption due to friction in passenger cars. Tribol. Int. 2012, 47, 221–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmberg, K.; Andersson, P.; Nylund, N.O.; Mäkelä, K.; Erdemir, A. Global energy consumption due to friction in trucks and buses. Tribol. Int. 2014, 78, 94–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, V.; Gautam, G.; Singh, M.K.; Ji, G.; Katiyar, J.K.; Mohan, S.; Mohan, A. Prediction of frictional behaviour through regression equations: A statistical modelling approach validated with machine learning. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part J J. Eng. Tribol. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, S.K.; Gupta, R.N.; Singh, M.K. Synthesis, fabrication and tribo-mechanical studies of microcapsules filled and Al 2 O 3 /glass fibre reinforced UHMWPE based self-lubricating and self-healing composites. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part L J. Mater. Des. Appl. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shekhar, C.; Wani, M.F.; Sehgal, R.; Saleem, S.S.; Ziyamukhamedova, U.; Tursunov, N. Recent Progress in Particulate Reinforced Copper-Based Composites: Fabrication, Microstructure, Mechanical, and Tribological Properties—A Review. Adv. Eng. Mater. 2025, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, Y.; Sharma, A.; Singla, A. Non-edible vegetable oil–based feedstocks capable of bio-lubricant production for automotive sector applications—a review. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2019, 26, 14867–14882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Randles, S.J. Environmentally considerate ester lubricants for the automotive and engineering industries. J. Synth. Lubr. 1992, 9, 145–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, B.K.; Adhvaryu, A.; Erhan, S.Z. Friction and wear behavior of thioether hydroxy vegetable oil. Tribol. Int. 2009, 42, 353–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erhan, S.Z.; Sharma, B.K.; Perez, J.M. Oxidation and low temperature stability of vegetable oil-based lubricants. Ind. Crops Prod. 2006, 24, 292–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fox, N.J.; Tyrer, B.; Stachowiak, G.W. Boundary lubrication performance of free fatty acids in sunflower oil. Tribol. Lett. 2004, 16, 275–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro, W.; Weller, D.E.; Cheenkachorn, K.; Perez, J.M. The effect of chemical structure of basefluids on antiwear effectiveness of additives. Tribol. Int. 2005, 38, 321–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siniawski, M.T.; Saniei, N.; Pfaendtner, J. Tribological degradation of two vegetable-based lubricants at elevated temperatures. J. Synth. Lubr. 2007, 24, 167–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahim, E.A.; Sasahara, H. Investigation of tool wear and surface integrity on MQL machining of Ti-6AL-4V using biodegradable oil. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part B J. Eng. Manuf. 2011, 225, 1505–1511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNutt, J.; He, Q.S. Development of biolubricants from vegetable oils via chemical modification. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 2016, 36, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loehle, S.; Matta, C.; Minfray, C.; Mogne, T. Le; Martin, J.M.; Iovine, R.; Obara, Y.; Miura, R.; Miyamoto, A. Mixed lubrication with C18 fatty acids: Effect of unsaturation. Tribol. Lett. 2014, 53, 319–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unnamalai, E.E.E. Performance Characteristics of Blended With Vegetable and Mineral Oil. 2023, 8, 428–431.

- Woma, T.Y.; Lawal, S.A.; Abdulrahman, A.S.; Olutoye, M.A.; Ojapah, M.M. Vegetable oil based lubricants: Challenges and prospects. Tribol. Online 2019, 14, 60–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, Y.; Kumar Singh, N.; Sharma, A.; Singla, A.; Singh, D.; Abd Rahim, E. Effect of ZnO nanoparticles concentration as additives to the epoxidized Euphorbia Lathyris oil and their tribological characterization. Fuel 2021, 285, 119148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habibullah, M.; Masjuki, H.H.; Kalam, M.A.; Ashraful, A.M.; Habib, M.A.; Mobarak, H.M. Effect of bio-lubricant on tribological characteristics of stefvel. Procedia Eng. 2014, 90, 740–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, U.C.; Sachan, S. Friction and wear behavior of karanja oil derived biolubricant base oil. SN Appl. Sci. 2019, 1, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agrawal, S.M.; Lahane, S.; Patil, N.G.; Brahmankar, P.K. Experimental investigations into wear characteristics of M2 steel using cotton seed oil. Procedia Eng. 2014, 97, 4–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suhane, A.; Rehman, A.; Khaira, H.K. Tribological Investigation of Mahua Oil Based Lubricant for Maintenance Applications. Int. J. Eng. 2013, 3, 2367–2371. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, S.; Tyagi, H.; Kumar, N.; Yadav, V. Comparative Tribological Investigation of Mahua Oil and its Chemically Modified Derivatives. SAE Int. J. Fuels Lubr. 2014, 7, 360–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, Y.; Singh, N.K.; Sharma, A.; Kishore, C.; Raturi, A. Madhuca Indica (Mahua): A novel feedstock for bio based lubricant application treated with trimethylolpropane and tribological analysis. Aust. J. Mech. Eng. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeevan, T.P.; Jayaram, S.R.; Afzal, A.; Ashrith, H.S.; Soudagar, M.E.M.; Mujtaba, M.A. Machinability of AA6061 aluminum alloy and AISI 304L stainless steel using nonedible vegetable oils applied as minimum quantity lubrication. J. Brazilian Soc. Mech. Sci. Eng. 2021, 43, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, R.; Woydt, M.; Zhang, S. The Economic and Environmental Significance of Sustainable Lubricants. Lubricants 2021, 9, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masnadi, M.S.; El-Houjeiri, H.M.; Schunack, D.; Li, Y.; Englander, J.G.; Badahdah, A.; Monfort, J.-C.; Anderson, J.E.; Wallington, T.J.; Bergerson, J.A.; et al. Global carbon intensity of crude oil production. Science 2018, 361, 851–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menezes, P.L.; Ingole, S.P.; Nosonovsky, M.; Kailas, S. V.; Lovell, M.R. Tribology for scientists and engineers: From basics to advanced concepts. Tribol. Sci. Eng. From Basics to Adv. Concepts 2013, 9781461419, 1–948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, Y.; Farooq, A.; Raza, A.; Mahmood, M.A.; Jain, S. Sustainability of a non-edible vegetable oil based bio-lubricant for automotive applications: A review. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 2017, 111, 701–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahu, F.M.; Suthar, S.H.; Suthar, H.G.; Jena, S. Mahua seed- a Multipurpose Tree-borne oilseeds ( TBOs ) of India. 2022, 9, 536–547.

- Chaurasia, S.K.; Sehgal, A.K.; Singh, N.K. Improved Lubrication Mechanism of Chemically Modified Mahua (Madhuca indica) Oil with Addition of Copper Oxide Nanoparticles. J. Bio- Tribo-Corrosion 2020, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pawar, M.S.; Kadam, A.S.; Yemul, O.S. Development of polyetheramide based corrosion protective polyurethane coating from mahua oil. Prog. Org. Coatings 2015, 89, 143–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, S.; Das, P.; Quadir, M.A.; Thaher, M.; Annamalai, S.N.; Mahata, C.; Hawari, A.H.; Al Jabri, H. A comparative physicochemical property assessment and techno-economic analysis of biolubricants produced using chemical modification and additive-based routes. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dhote Priya, S.; Ganvir, V.N. Methanolysis of High FFA Mahua Oil in an Oscillatory Baffled ( Batch ) Reactor. 2014, 3, 32–39.

- Gupta, A.; Chaudhary, R.; Sharma, S. Potential applications of mahua (Madhuca indica) biomass. Waste and Biomass Valorization 2012, 3, 175–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, H.S.; Sehgal, R.; Wani, M.F. Investigating the Effect of GNP, ZnO, and CuO Nanoparticles on the Tribological, Rheological, and Corrosion Behavior of Bio-based Mahua Oil. Energy Sources, Part A Recover. Util. Environ. Eff. 2023, 45, 9081–9092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baskar, G.; Gurugulladevi, A.; Nishanthini, T.; Aiswarya, R.; Tamilarasan, K. Optimization and kinetics of biodiesel production from Mahua oil using manganese doped zinc oxide nanocatalyst. Renew. Energy 2017, 103, 641–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivyas, P.D.; Charoo, M.S. Effect of lubricants additive: Use and benefit. Mater. Today Proc. 2019, 18, 4773–4781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, Z.; Tao, P. Characteristics of rolling interface lubrication considering contact surface textures in mixed lubrication. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part J J. Eng. Tribol. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malinowska, M. The Full or Partial Replacement of Commercial Marine Engine Oil with Bio Oil, on the Example of Linseed Oil. J. KONES 2019, 26, 129–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shafi, W.K.; Charoo, M.S. Experimental study on rheological properties of vegetable oils mixed with titanium dioxide nanoparticles. J. Brazilian Soc. Mech. Sci. Eng. 2019, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Li, C.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Jia, D.; Yang, M. Grinding temperature and energy ratio coefficient in MQL grinding of high-temperature nickel-base alloy by using different vegetable oils as base oil. Chinese J. Aeronaut. 2016, 29, 1084–1095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| S. No | Peak position | Functional group present | Peak details | class | MO | SAE20W40 | PAO4 | MO+ SAE20W40 |

MO+ PAO4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2500-3300 | O-H stretching | Weak | alcohol | - | - | - | 3004.76 | 3004.76 |

| 2 | 2840-3000 | C-H stretching | medium | alkane | 2919.19,2853.59 | 2920.62, 2855.02 |

2920.62, 2855.02 |

2922.04, 2853.59 | 2922.04, 2853.59 |

| 3 | 2190-2260 | C≡C | Weak | alkyne | - | - | - | - | 2234.76 |

| 4 | 2150 | C=C=O stretching | - | ketene | - | - | - | - | 2167.65 |

| 5 | 1735-1750 | C=O stretching | strong | ester | 1742.67 | - | - | 1744.10 | 1744.10 |

| 6 | 1465, 1450 | C-H bending | medium | alkane | 1456.03 | 1458.88 | 1460.31, 1404.69 |

1458.88 | 1458.86 |

| 7 | 1330-1420 | O-H bending | medium | alcohol | 1367.61 | 1379.02 | - | 1371.89 | 1371.89 |

| 8 | 1300-1350 | S=O stretching | strong | sulfone | - | 1306.29 | - | - | - |

| 9 | 1124-1205 | C-O stretching | strong | tertiary alcohol | 1159.41 | - | - | 1159.41 | 1159.41 |

| 10 | 1020-1250 | C-N stretching | medium | amine | - | 1159.41 | - | 1109.44, 1236.41 |

1109.49, 1234.99 |

| 11 | 960-980 | C=C bending | strong | alkene | - | 974.01 | - | - | - |

| 12 | 665-730 | C=C bending | strong | alkene | 720.17 | 725.88 | 723.02 | 721.60 | 721.60 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).