Submitted:

12 June 2025

Posted:

16 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

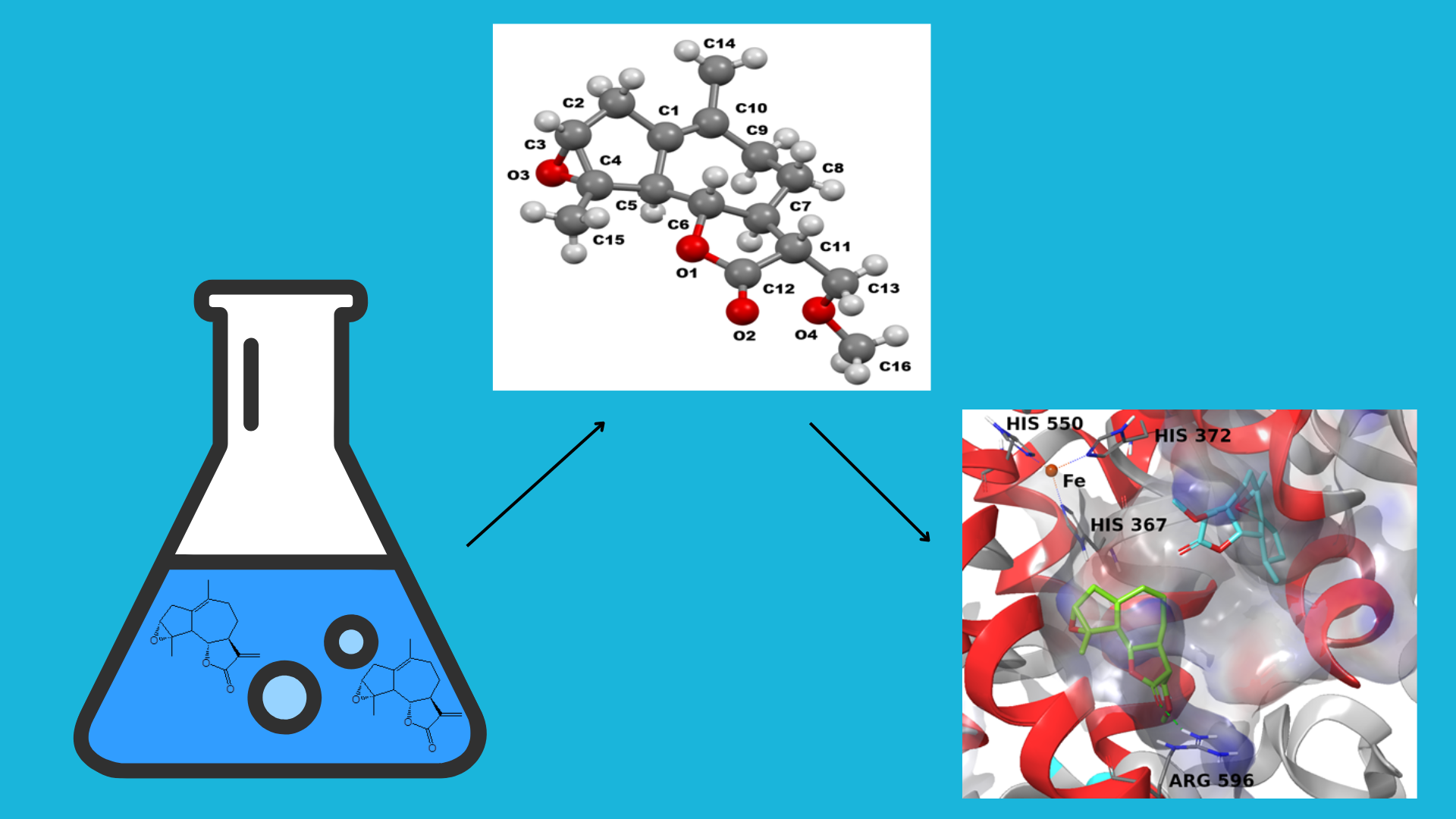

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

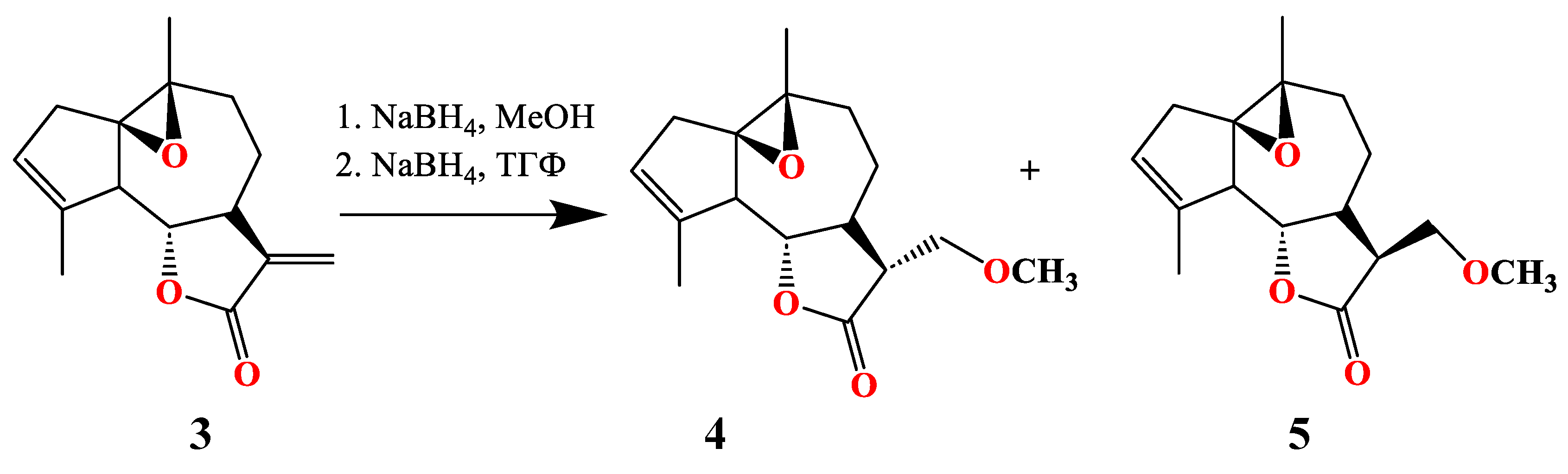

| Torsion angles | Structure | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | 4a | 4b | |

| The cycle A | |||

| C5-C1-C2-C3 | -8.1(2) | 21.5(2) | 23.8(2) |

| C1-C2-C3-C4 | 6.7(2) | -11.9(2) | -13.6(3) |

| C2-C3-C4-C5 | -2.8(2) | -2.9(2) | -2.6(3) |

| C3-C4-C5-C1 | -2.2(2) | 16.3(2) | 17.4(2) |

| C2-C1-C5-C4 | 6.4(2) | -23.0(2) | -25.0(2) |

| The cycle В | |||

| C10-C1-C5-C6 | 58.1(2) | 49.2(2) | 47.7(3) |

| C1-C5-C6-C7 | -75.5(2) | -69.7(2) | -68.3(2) |

| C5-C6-C7-C8 | 71.1(2) | 76.0(2) | 76.2(2) |

| C6-C7-C8-C9 | -67.7(2) | -73.4(2) | -74.6(2) |

| C7-C8-C9-C10 | 76.3(2) | 68.4(2) | 69.7(2) |

| C8-C9-C10-C1 | -62.4(2) | -46.7(3) | -46.8(3) |

| C5-C1-C10-C9 | 1.1(3) | -2.1(3) | -2.4(3) |

| The cycle С | |||

| O1-C6-C7-C11 | -39.7(2) | -37.0(2) | -37.9(2) |

| C12-O1-C6-C7 | 27.2(2) | 26.4(2) | 25.9(2) |

| C6-O1-C12-C11 | -2.8(2) | -4.1(2) | -2.3(2) |

| C7-C11-C12-O1 | -22.6(2) | -19.7(2) | -21.8(2) |

| C6-C7-C11-C12 | 37.2(2) | 34.0(2) | 36.0(2) |

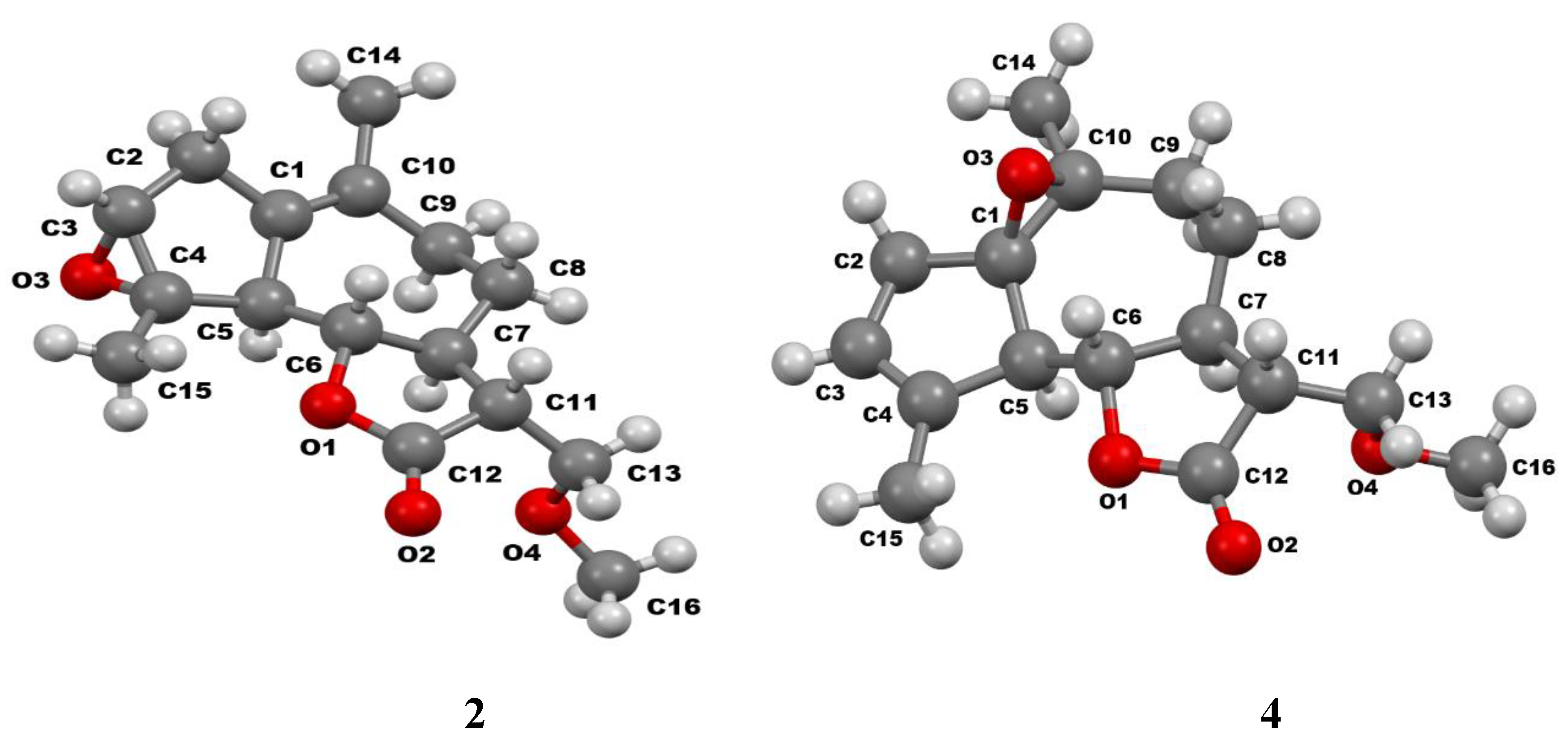

| Ligand | Docking parameters, kcal/mol | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Docking score | LE | Emodel | |

| NDGA | -7.876 | -0.358 | -51.104 |

| compound 4 | -5.892 | -0.295 | -17.585 |

| compound 2 | -5.365 | -0.282 | -37.619 |

4. Materials and Methods

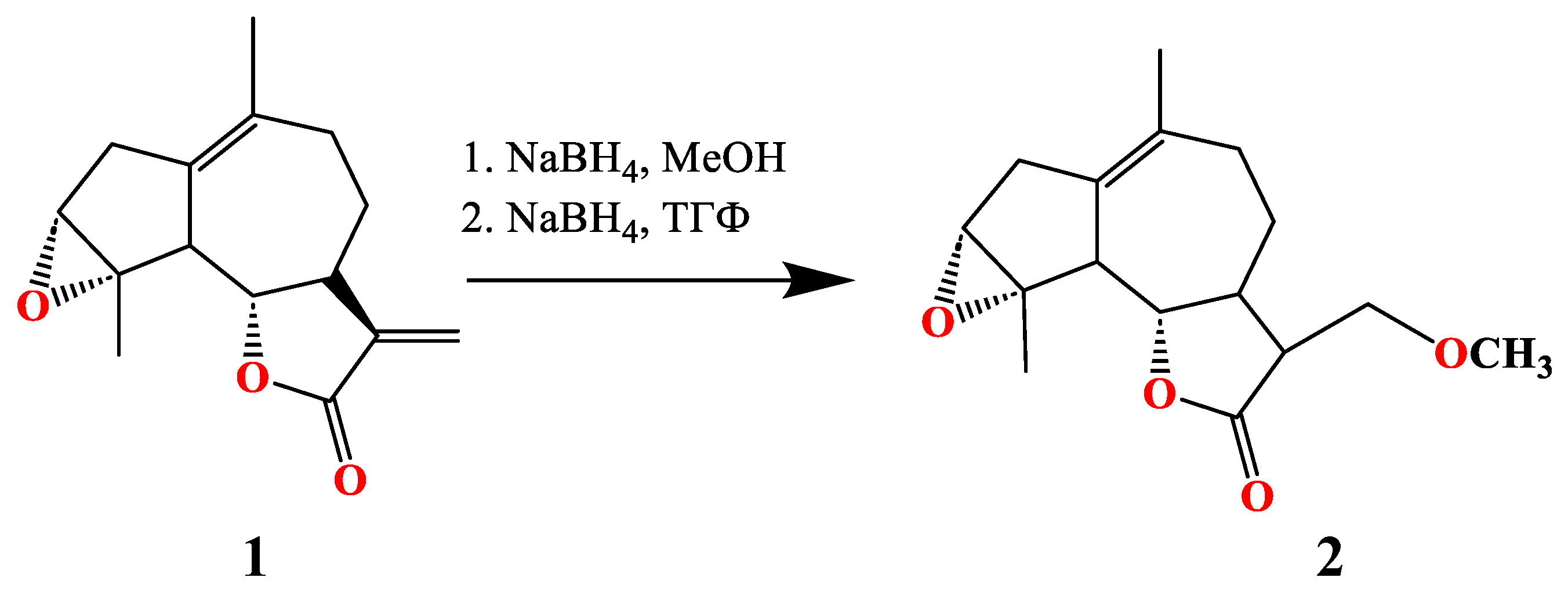

3.1. Synthesis of of 13-Methoxy Derivatives 2,4,5

3.2. Crystallographic Study:

| Compound | 2 | 4 |

|---|---|---|

| Empirical formula | C16H22O4 | C16H22O4 |

| Formula weight | 278.34 | 278.34 |

| T, K | 296 | 173 |

| Wavelength (Å) | 0.71073 | 0.71073 |

| Crystal system | monoclinic | orthorhombic |

| Space group | P21 | P212121 |

| a, Å | 11.2615(4) | 9.4329(8) |

| b, Å | 5.6092(2) | 9.4525(7) |

| c, Å | 12.2180(5) | 33.065(3) |

| β, degree | 106.007(2) | 90 |

| Volume, Å3 | 741.86(5) | 2948.2(4) |

| Z | 2 | 8 |

| Calculated density,g/cm3 | 1.246 | 1.254 |

| Absorption coefficient, mm-1 | 0.088 | 0.089 |

| F(000) | 300 | 1200 |

| Crystal size (mm) | 0.58 × 0.35 × 0.08 | 0.54 × 0.37 × 0.09 |

| Theta range | 1.73 ≤ θ ≤ 27.21 | 1.23 ≤ θ ≤ 25.03 |

| Reflection collected/unique | 15330 / 3269 | 30235 / 5200 |

| R(int) | 0.0216 | 0.0644 |

| Absorption correction | multi-scan | multi-scan |

| Absorption correction, T(min, max) | 0.9535, 0.9920 | 0.9505, 0.9930 |

| Data/restraints/parameters | 3269 / 1 / 184 | 5200 / 0 / 369 |

| Goodness-of-fit on F2 | 1.093 | 1.046 |

| R1, WR2 (I ≥ 2σ(I) | 0.0351, 0.0899 | 0.0356, 0.0752 |

| R1, WR2 (all data) | 0.0456, 0.1046 | 0.0424, 0.0781 |

| Largest diff. peak and hole, е/Å3 | 0.149, -0.118 | 0.261, -0.259 |

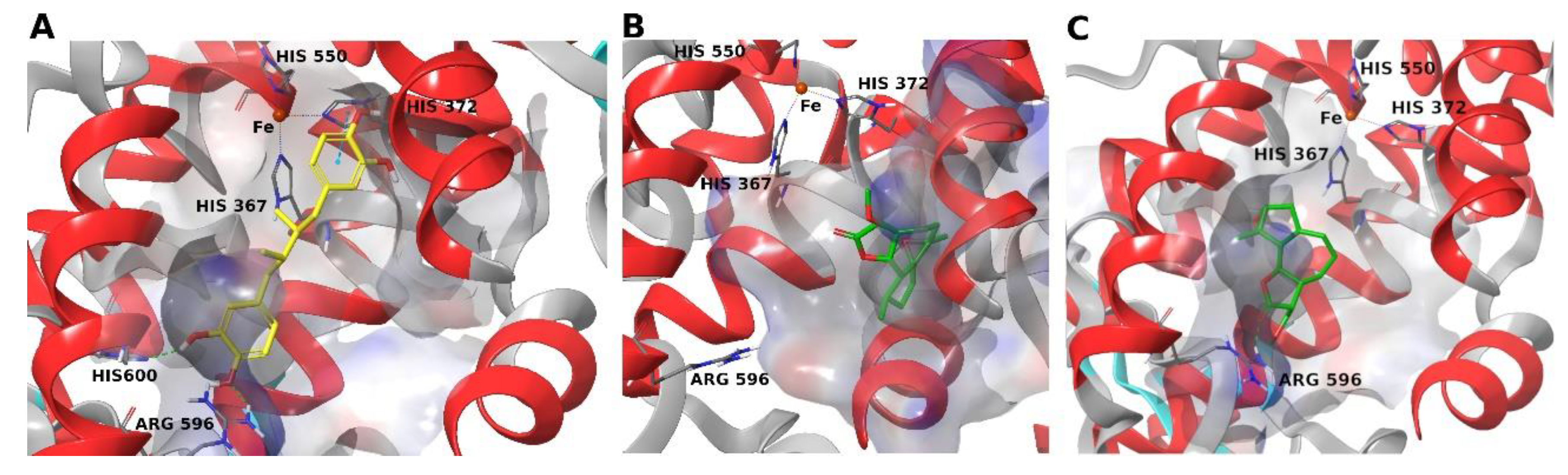

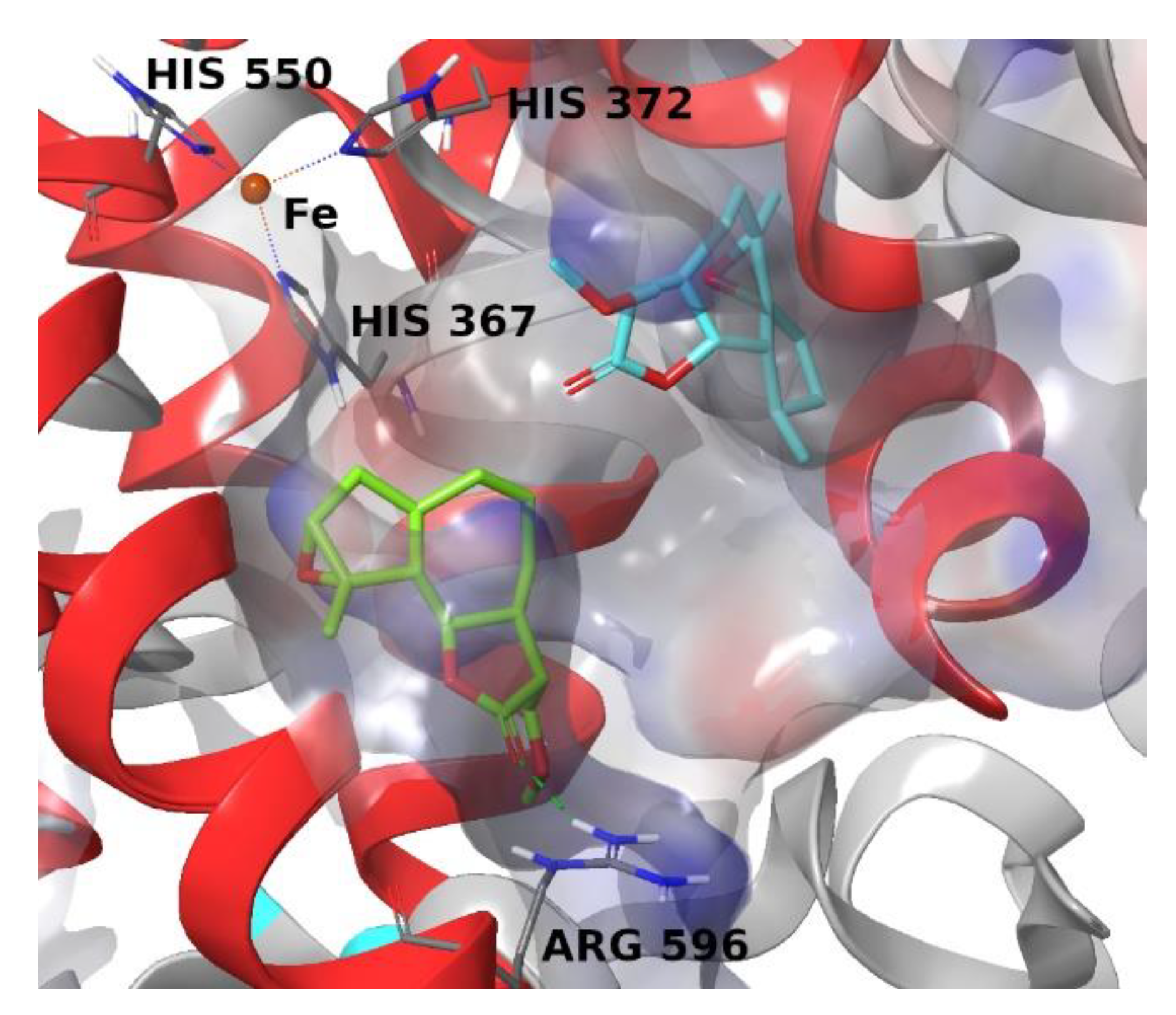

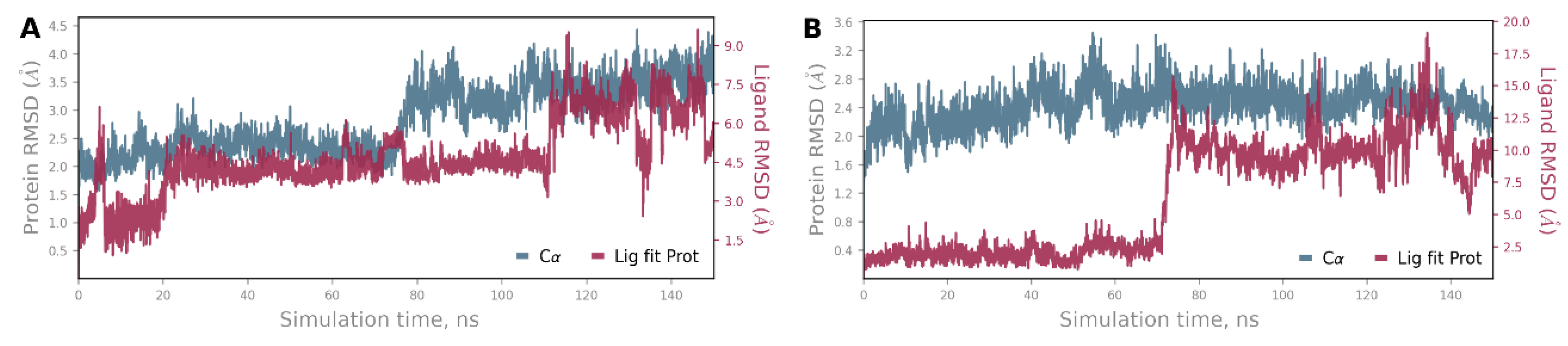

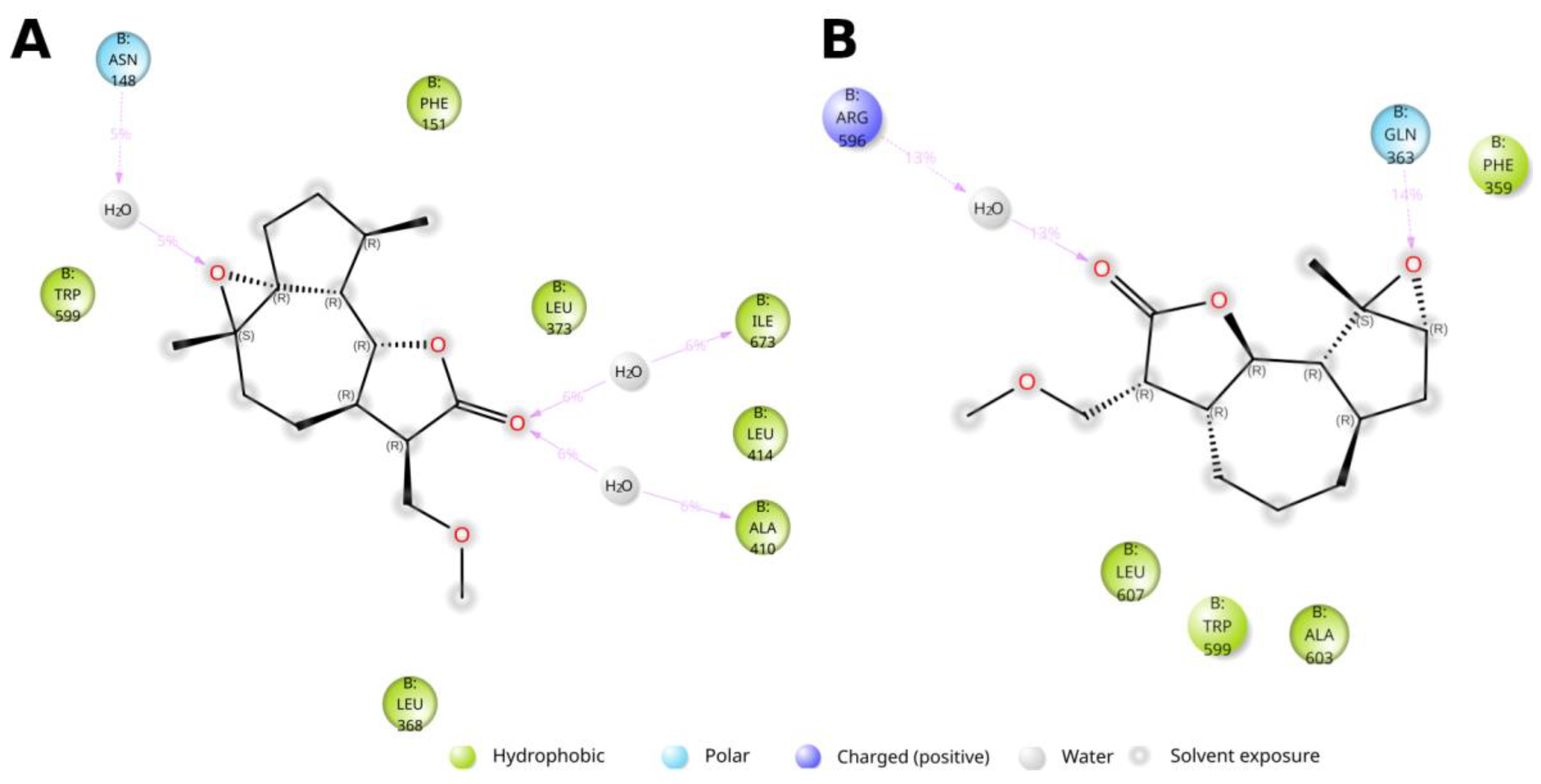

3.3. Molecular Modeling

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Rybalko, K.S. Natural sesquiterpene lactones, Medicine: Moscow, Russia, 1978; p.320.

- Fischer, N.H.; Olivier, E.J.; Fischer, H.D. The biogenesis and chemistry of sesquiterpene lactones. Fortschr. Chem. Org. Naturst. 1979, 38, 47–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kagarlitskii, A.D.; Adekenov, S.M.; Kupriyanov, A.N. Sesquiterpene lactones of plants of Central Kazakhstan, Nauka: Almaty, Kazakhstan, 1987; p.240.

- Seaman, F.C. Sesquiterpene Lactones as Taxonomic Characters in the Asteraceae. The Botanical Review. 1982, 48, 121–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraga, B.M. Natural sesquiterpenoids. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2006, 23, 943–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodriguez, E.; Towers, G.H.N.; Mitchell, J.C. Biological activities of sesquiterpene lactones. Phytochemistry. 1976, 15, 1573–1580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parness, J.; Kingston, D.G.; Powell, R.G.; Harracksingh, C.; Horwitz, S.B. Structure-activity study of cytotoxicity and microtubule assembly in vitro by taxol and related taxanes. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1982, 105, 1082–1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Søhoel, H.; Jensen, A.M.L.; Møller, J.V.; Nissen, P.; Denmeade, S.R.; Isaacs, J.T.; Olsen, C.E.; Christensen, S.B. Natural products as starting materials for development of second-generation SERCA inhibitors targeted towards prostate cancer cells. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2006, 14, 2810–2815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramadan, M.; Goeters, S.; Watzer, B.; Krause, E.; Lohmann, K.; Bauer, R.; Hempel, B.; Imming, P. Chamazulene carboxylic acid and matricin: a natural profen and its natural prodrug, identified through similarity to synthetic drug substances. J. Nat. Prod. 2006, 69, 1041–1045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, T.; Nour, A.; Khalid, S.; Kaiser, M.; Brun, R. Quantitative structure ‒ antiprotozoal activity relationships of sesquiterpene lactones. Molecules. 2009, 14, 2062–2076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mashkovskii, M.D. Lekarstvennye sredstva. New wave: Moscow, Russia, 2024, p. 1216.

- Funk, C.D. Prostaglandins and Leukotrienes: Advances in Eicosanoid Biology. Science 2001, 294, 1871–1875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rådmark, O.; Werz, O.; Steinhilber, D.; Samuelsson, B. 5-Lipoxygenase, a key enzyme for leukotriene biosynthesis in health and disease. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta - Molecular and Cell Biology of Lipids 2015, 1851, 331–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drazen, J.M.; Israel, E.; O’Byrne, P.M. Treatment of Asthma with Drugs Modifying the Leukotriene Pathway. New England Journal of Medicine 1999, 340, 197–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rouzer, C.A.; Ford-Hutchinson, A.W.; Morton, H.E.; Gillard, J.W. MK886, a potent and specific leukotriene biosynthesis inhibitor blocks and reverses the membrane association of 5-lipoxygenase in ionophore-challenged leukocytes. Journal of Biological Chemistry 1990, 265, 1436–1442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fischer, L.; Hornig, M.; Pergola, C.; Meindl, N.; Franke, L.; Tanrikulu, Y.; Dodt, G.; Schneider, G.; Steinhilber, D.; Werz, O. The molecular mechanism of the inhibition by licofelone of the biosynthesis of 5-lipoxygenase products. British Journal of Pharmacology 2007, 152, 471–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kwon, O.S.; Choi, J.S.; Islam, M.N.; Kim, Y.S.; Kim, H.P. Inhibition of 5-lipoxygenase and skin inflammation by the aerial parts of Artemisia capillaris and its constituents. Archives of Pharmacal Research 2011, 34, 1561–1569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pergola, C.; Werz, O. 5-Lipoxygenase inhibitors: A review of recent developments and patents. Expert Opinion on Therapeutic Patents 2010, 20, 355–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koeberle, A.; Werz, O. Multi-target approach for natural products in inflammation. Drug Discovery Today 2014, 19, 1871–1882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adekenov, S.M.; Kagarlitskii, A.D. Chemistry of sesquiterpene lactones, Nauka: Almaty, Kazakhstan, 1990; p.188.

- Dondorp, A.M.; Nosten, F.; Yi, P.; Das, D.; Phyo, A.P.; Tarning, J.; Lwin, K.M.; Ariey, F.; Hanpithakpong, W.; Lee, S.J.; Ringwald, P.; Silamut, K.; Imwong, M.; Chotivanich, K.; Lim, P.; Herdman, T.; An, S.S.; Yeung, S.; Singhasivanon, P.; Day, N.P.J.; Lindegardh, N.; Socheat, D.; White, N.J. Artemisinin resistance in Plasmodium falciparum malaria. N. Engl. J. Med. 2009, 361, 455–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geissman, T.A.; Griffin, T.S. Sesquiterpene lactones of Artemisia carruthii. Phytochemistry. 1972, 11, 833–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adekenov, S.M.; Mukhametzhanov, M.N.; Kagarlitskii, A.D.; Kupriyanov, A.N. Arglabin - A new sesquiterpene lactone from Artemisia glabella. Chem. Nat. Compd. 1982, 18, 623–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, F.H.; Kennard, O.; Watson, D.G.; Brammer, L.; Orpen, A.G.; Taylor, R. Tables of bond lengths determined by X-ray and neutron diffraction. J. Chem. Soc. Perkin Trans. 2. 1987, S1–S19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SMART and SAINT, Area detector control and integration software. 2012, Bruker AXS Inc., Madison, WI-53719, USA.

- Sheldrick, G.M. SADABS. 2012, Bruker AXS Inc., Madison, WI-53719, USA.

- Sheldrick, G.M. A short history of SHELX. Acta Crystaollogr., Sect. A: Found.Crystallogr. 2008, 64, 112–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sheldrick, G.M. Crystal structure refinement with SHELXL. Acta Crystaollogr., Sect. C: Structural Chemistry. 2015, 714, 3–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bochevarov, A.D.; Harder, E.; Hughes, T.F.; Greenwood, J.R.; Braden, D.A.; Philipp, D.M.; Rinaldo, D.; Halls, M.D.; Zhang, J.; Friesner, R.A. Jaguar: A high-performance quantum chemistry software program with strengths in life and materials sciences. International Journal of Quantum Chemistry 2013, 113, 2110–2142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilbert, N.C.; Gerstmeier, J.; Schexnaydre, E.E.; Börner, F.; Garscha, U.; Neau, D.B.; Werz, O.; Newcomer, M.E. Structural and mechanistic insights into 5-lipoxygenase inhibition by natural products. Nature Chemical Biology 2020, 16, 783–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherman, W.; Day, T.; Jacobson, M.P.; Friesner, R.A.; Farid, R. Novel procedure for modeling ligand/receptor induced fit effects. Journal of Medicinal Chemistry 2006, 49, 534–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friesner, R.A.; Murphy, R.B.; Repasky, M.P.; Frye, L.L.; Greenwood, J.R.; Halgren, T.A.; Sanschagrin, P.C.; Mainz, D.T. Extra Precision Glide: Docking and Scoring Incorporating a Model of Hydrophobic Enclosure for Protein−Ligand Complexes. Journal of Medicinal Chemistry 2006, 49, 6177–6196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobson, M.P.; Pincus, D.L.; Rapp, C.S.; Day, T.J.F.; Honig, B.; Shaw, D.E.; Friesner, R.A. A Hierarchical Approach to All-Atom Protein Loop Prediction. Proteins: Structure, Function and Genetics 2004, 55, 351–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowers, K.J.; Chow, D.E.; Xu, H.; Dror, R.O.; Eastwood, M.P.; Gregersen, B.A.; Klepeis, J.L.; Kolossvary, I.; Moraes, M.A.; Sacerdoti, F.D.; et al. Scalable Algorithms for Molecular Dynamics Simulations on Commodity Clusters. In Proceedings of the ACM/IEEE SC 2006 Conference (SC’06); IEEE; 2006; pp. 43–43. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).