Submitted:

09 July 2025

Posted:

09 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Methodology

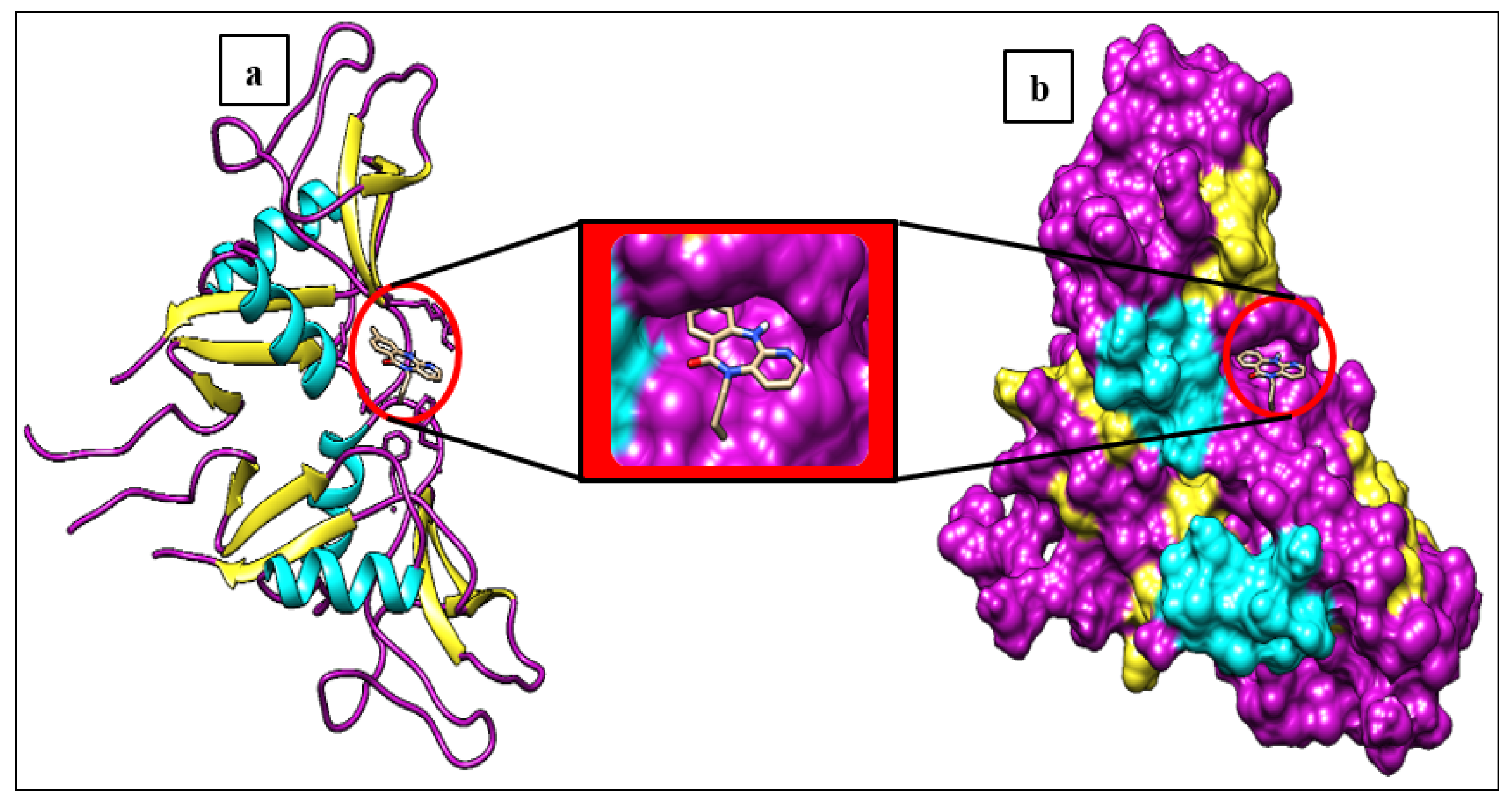

2.1. Protein Preparation

2.2. Ligand Preparation

2.3. Molecular Docking

2.4. Prediction of Drug-like Properties and Bioactivity Scores

2.5. ADME Analysis

2.6. Toxicological Properties

2.7. Molecular Dynamics Simulation

3. Results and Discussion

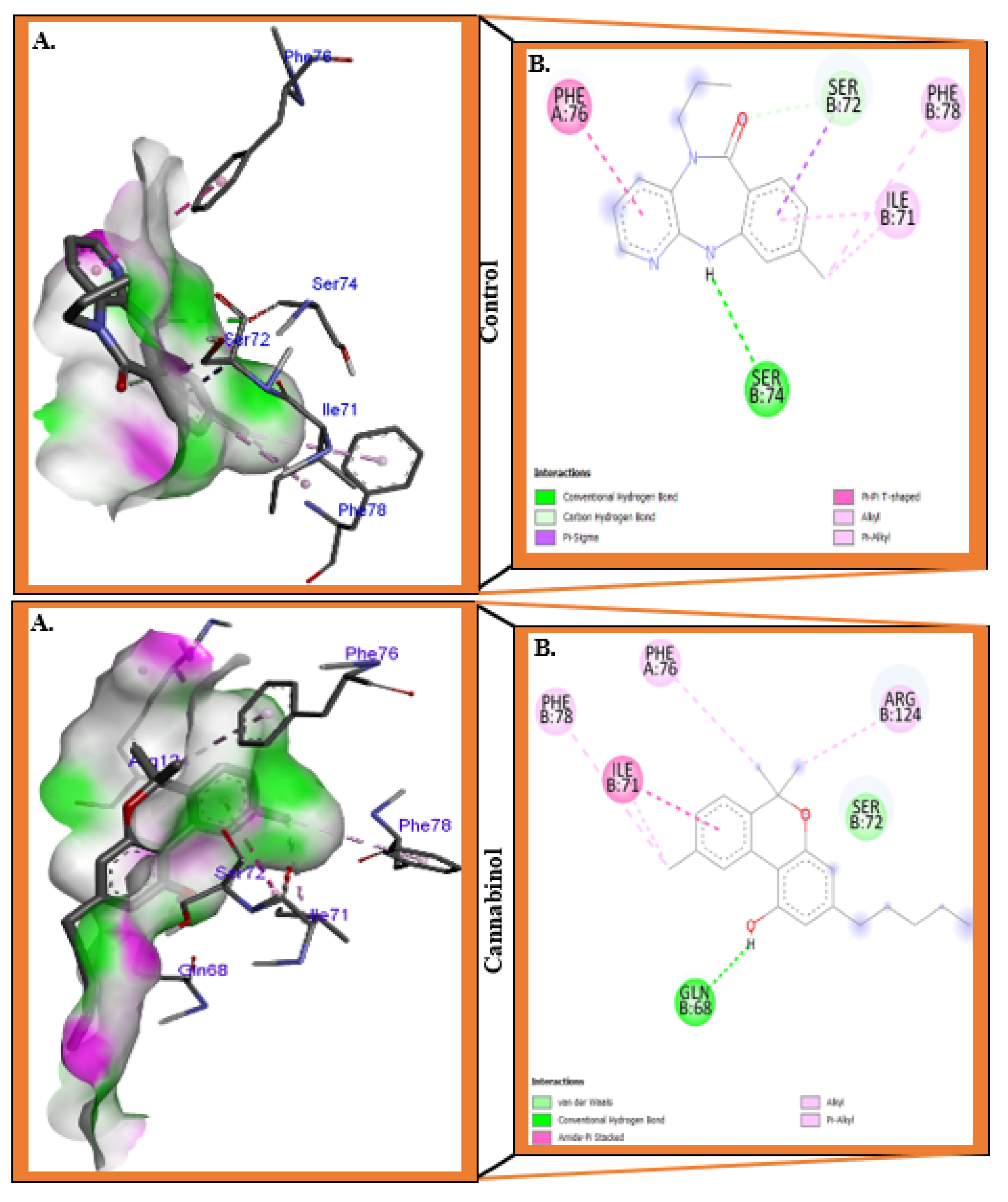

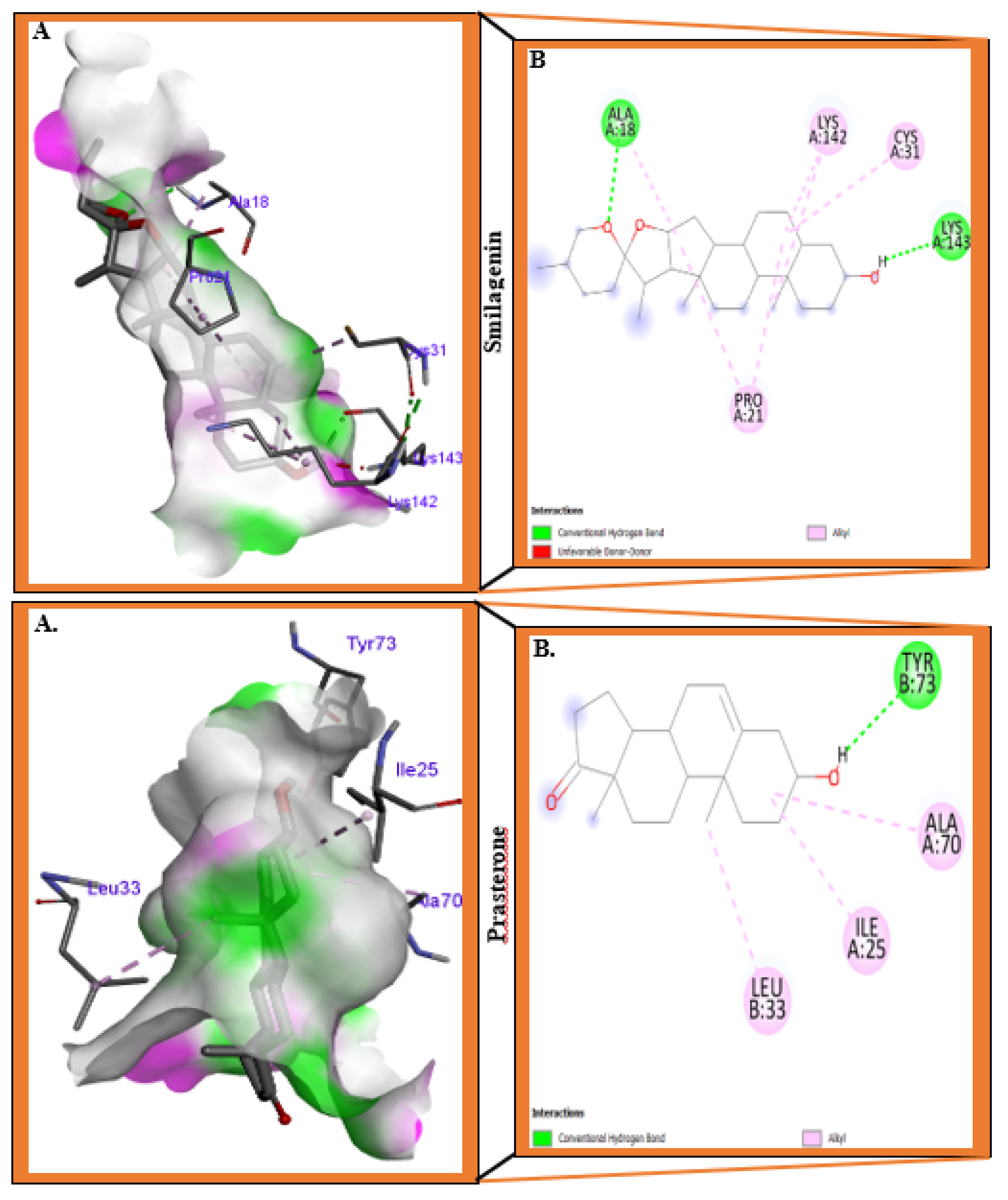

3.1. Molecular Docking Analysis

3.2. Prediction of Drug-like Properties

3.3. ADME Property Analysis

3.4. Toxicological Properties

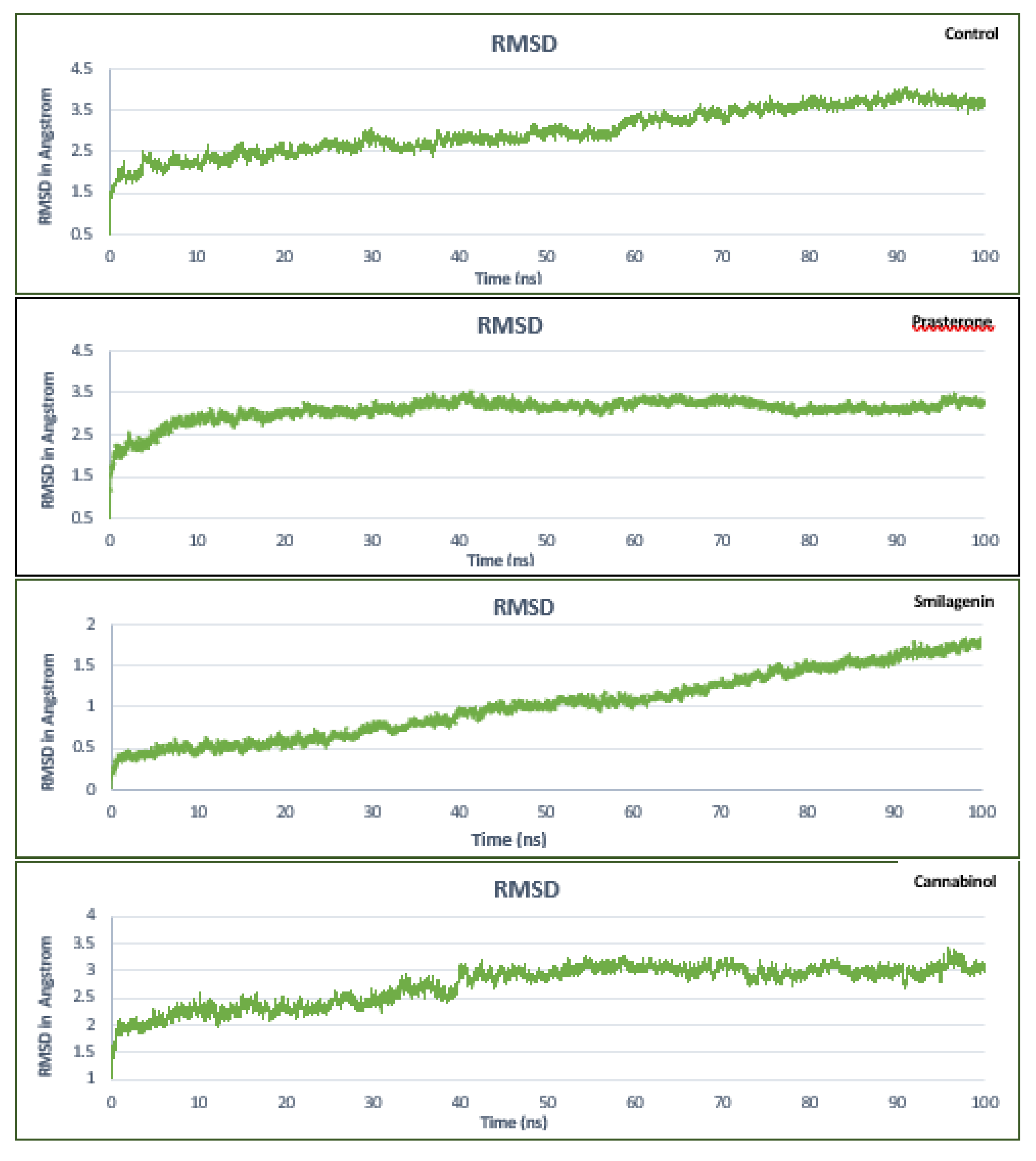

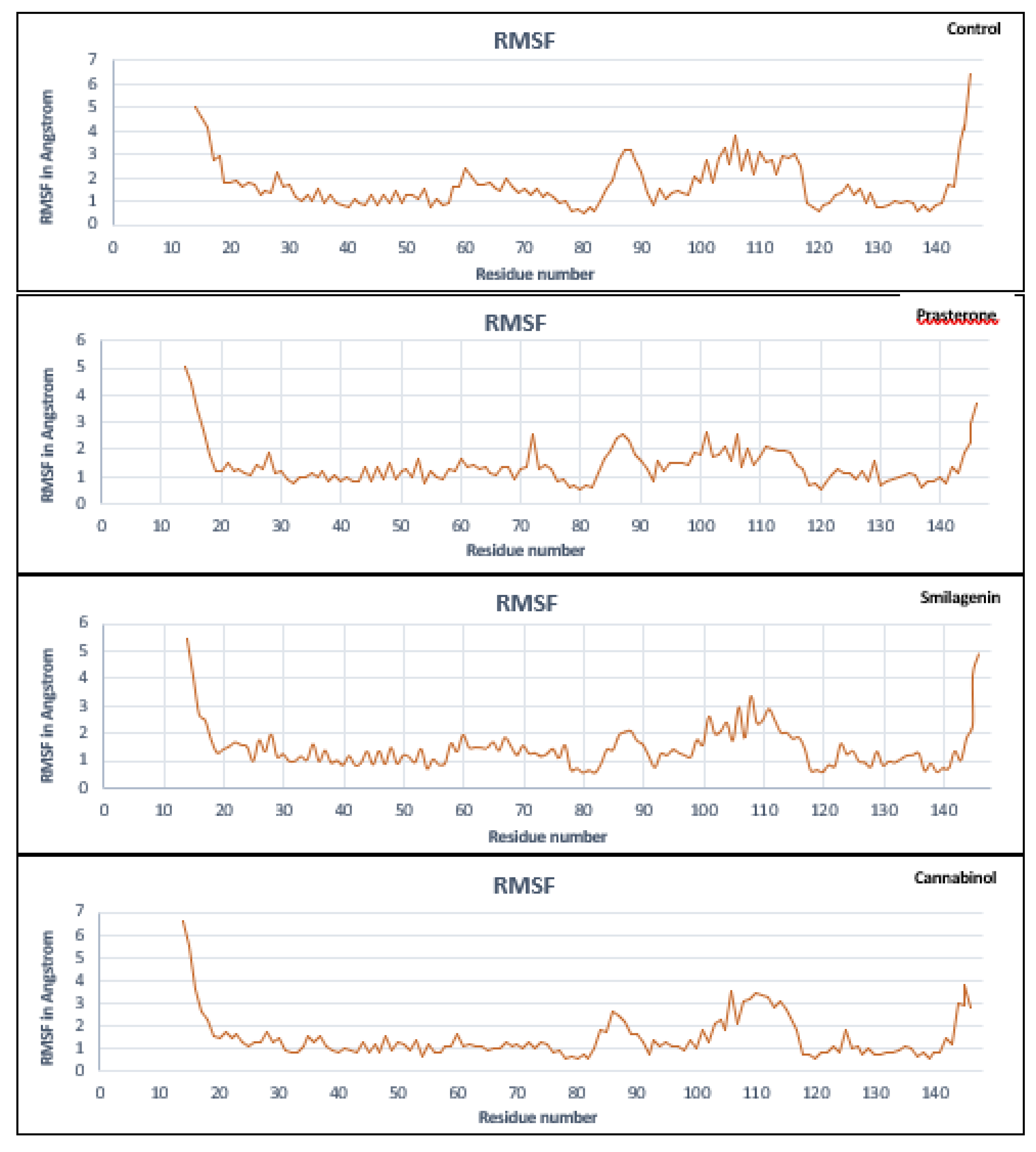

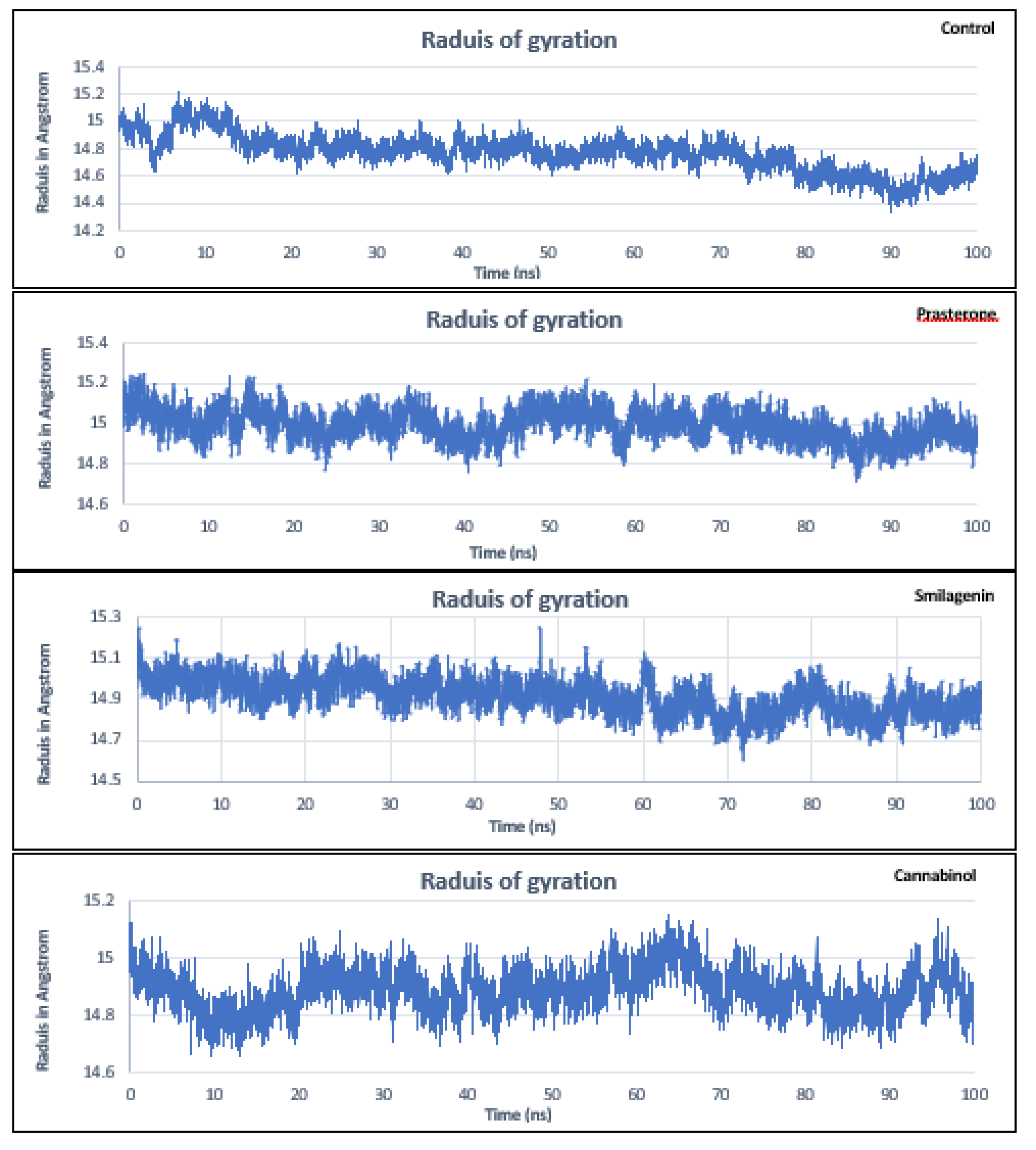

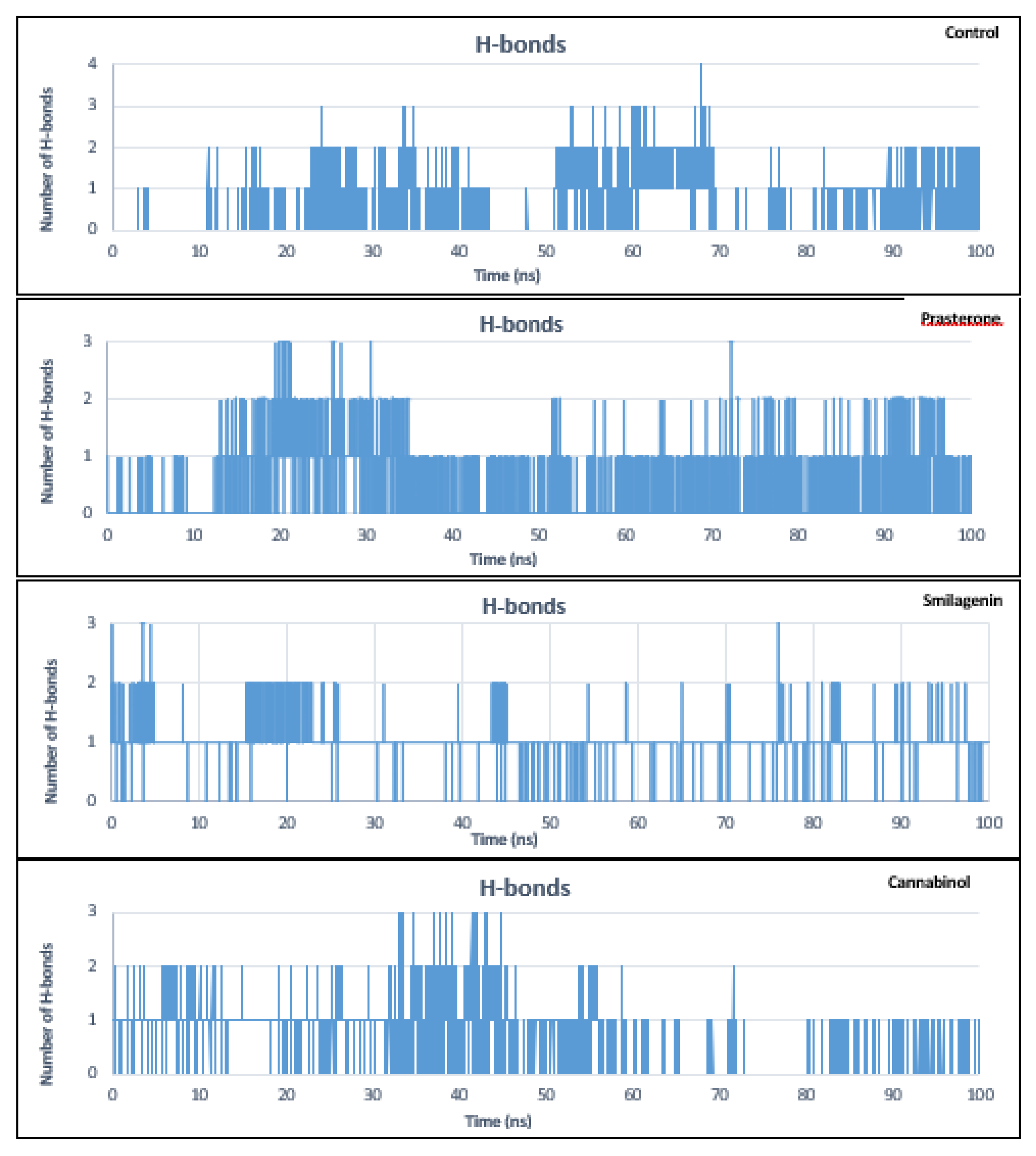

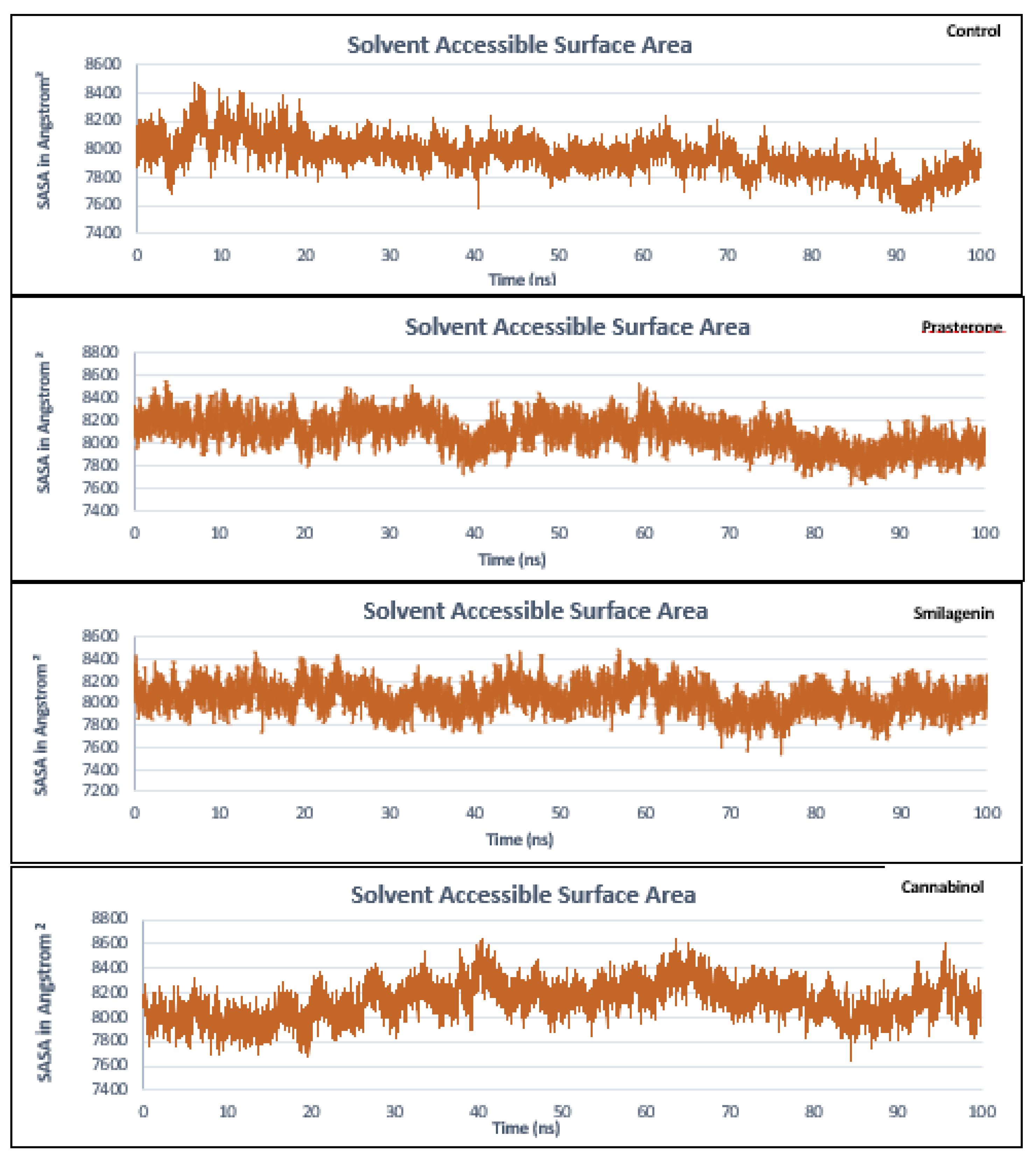

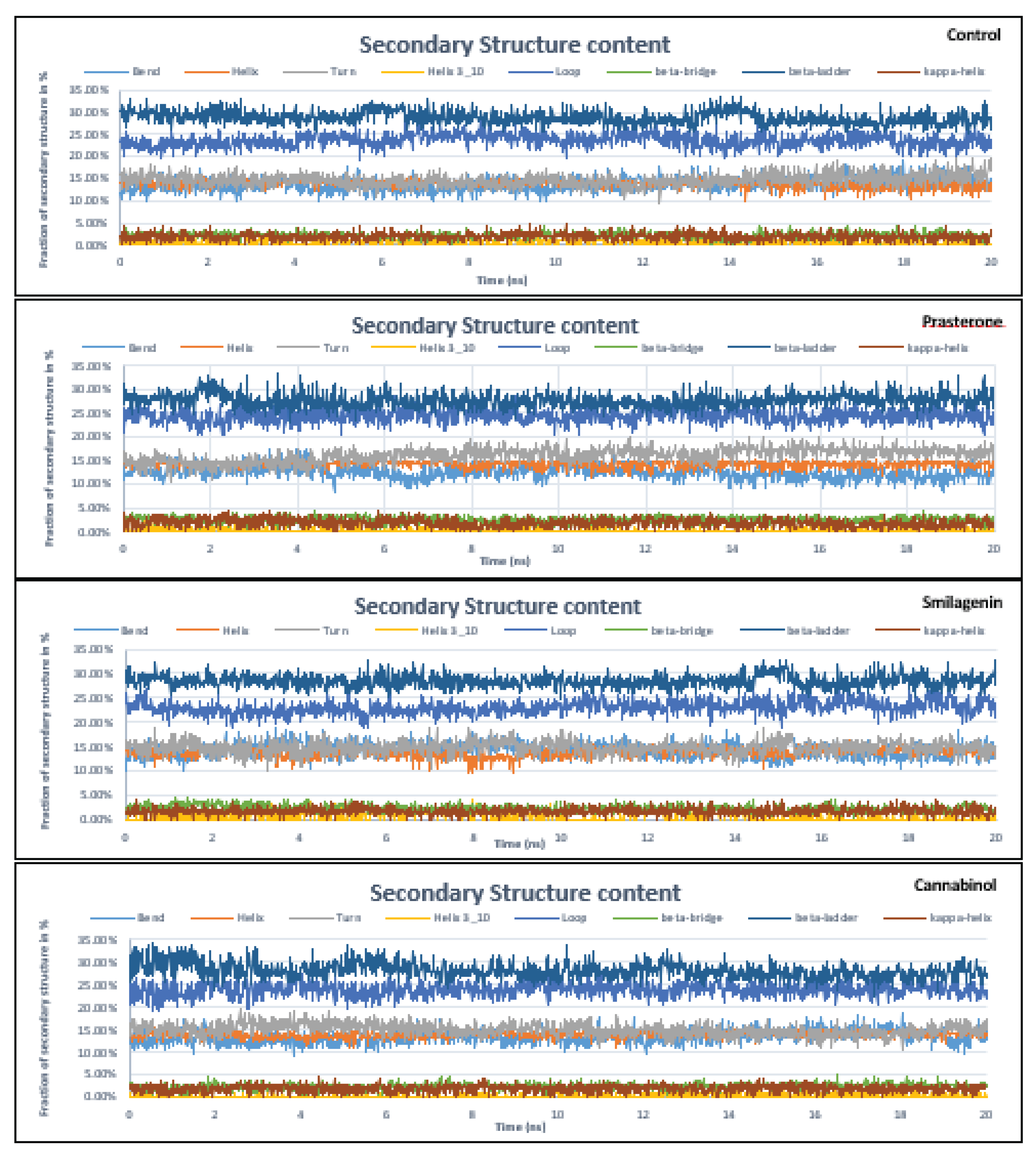

3.5. Molecular Dynamics Simulation Analysis

4. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- T. Sawamura et al., “An endothelial receptor for oxidized low-density lipoprotein,” Nature, vol. 386, no. 6620, Art. no. 6620, 1997. [CrossRef]

- J. L. Mehta and D. Li, “Identification, regulation and function of a novel lectin-like oxidized low-density lipoprotein receptor,” Journal of the American College of Cardiology, vol. 39, no. 9, Art. no. 9, 2002. [CrossRef]

- H. Park, F. G. Adsit, and J. C. Boyington, “The 1.4 Å Crystal Structure of the Human Oxidized Low Density Lipoprotein Receptor Lox-1,” Journal of Biological Chemistry, vol. 280, no. 14, Art. no. 14, 2005. [CrossRef]

- Q. Xie et al., “Human Lectin-Like Oxidized Low-Density Lipoprotein Receptor-1 Functions as a Dimer in Living Cells,” DNA and Cell Biology, vol. 23, no. 2, Art. no. 2, 2004. [CrossRef]

- M. Chen, S. Narumiya, T. Masaki, and T. Sawamura, “Conserved C-terminal residues within the lectin-like domain of LOX-1 are essential for oxidized low-density-lipoprotein binding,” Biochemical Journal, vol. 355, no. 2, pp. 289–296, 2001. [CrossRef]

- I. Ohki et al., “Crystal Structure of Human Lectin-like, Oxidized Low-Density Lipoprotein Receptor 1 Ligand Binding Domain and Its Ligand Recognition Mode to OxLDL,” Structure, vol. 13, no. 6, pp. 905–917, 2005. [CrossRef]

- X. Shi, S. Niimi, T. Ohtani, and S. Machida, “Characterization of residues and sequences of the carbohydrate recognition domain required for cell surface localization and ligand binding of human lectin-like oxidized LDL receptor,” Journal of Cell Science, vol. 114, no. 7, Art. no. 7, 2001. [CrossRef]

- M. Falconi, S. Biocca, G. Novelli, and A. Desideri, “Molecular dynamics simulation of human LOX-1 provides an explanation for the lack of OxLDL binding to the Trp150Ala mutant,” BMC Struct Biol, vol. 7, no. 1, Art. no. 1, 2007. [CrossRef]

- T. Ishigaki, I. Ohki, N. Utsunomiya-Tate, and S. -i. Tate, “Chimeric Structural Stabilities in the Coiled-Coil Structure of the NECK Domain in Human Lectin-Like Oxidized Low-Density Lipoprotein Receptor 1 (LOX-1),” Journal of Biochemistry, vol. 141, no. 6, Art. no. 6, 2007. [CrossRef]

- S. Biocca et al., “Simulative and experimental investigation on the cleavage site that generates the soluble human LOX-1,” Archives of Biochemistry and Biophysics, vol. 540, no. 1–2, Art. no. 1–2, 2013. [CrossRef]

- H. Mitsuoka et al., “Interleukin 18 stimulates release of soluble lectin-like oxidized LDL receptor-1 (sLOX-1),” Atherosclerosis, vol. 202, no. 1, Art. no. 1, 2009. [CrossRef]

- M. Ghazi-Khanloosani, A. R. Bandegi, P. Kokhaei, M. Barati, and A. Pakdel, “CRP and LOX-1: a Mechanism for Increasing the Tumorigenic Potential of Colorectal Cancer Carcinoma Cell Line,” Pathol Oncol Res, vol. 25, no. 4, Art. no. 4, 2019. [CrossRef]

- M. Murdocca et al., “LOX-1 and cancer: an indissoluble liaison,” Cancer Gene Ther, vol. 28, no. 10, Art. no. 10, 2021. [CrossRef]

- F. Spaans et al., “Syncytiotrophoblast extracellular vesicles impair rat uterine vascular function via the lectin-like oxidized LDL receptor-1,” PLoS One, vol. 12, no. 7, Art. no. 7, 2017. [CrossRef]

- B. Rizzacasa, E. Morini, S. Pucci, M. Murdocca, G. Novelli, and F. Amati, “LOX-1 and Its Splice Variants: A New Challenge for Atherosclerosis and Cancer-Targeted Therapies,” Int J Mol Sci, vol. 18, no. 2, Art. no. 2, 2017. [CrossRef]

- M. Murdocca et al., “Targeting LOX-1 Inhibits Colorectal Cancer Metastasis in an Animal Model,” Front. Oncol., vol. 9, p. 927, 2019. [CrossRef]

- J. Barreto, S. K. Karathanasis, A. Remaley, and A. C. Sposito, “Role of LOX-1 (Lectin-Like Oxidized Low-Density Lipoprotein Receptor 1) as a Cardiovascular Risk Predictor: Mechanistic Insight and Potential Clinical Use,” ATVB, 2020. [CrossRef]

- G. Schnapp et al., “A small-molecule inhibitor of lectin-like oxidized LDL receptor-1 acts by stabilizing an inactive receptor tetramer state,” Commun Chem, vol. 3, no. 1, Art. no. 1, 2020. [CrossRef]

- M. M. Matin, P. Chakraborty, M. S. Alam, M. M. Islam, and U. Hanee, “Novel mannopyranoside esters as sterol 14α-demethylase inhibitors: Synthesis, PASS predication, molecular docking, and pharmacokinetic studies,” Carbohydrate Research, vol. 496, p. 108130, 2020. [CrossRef]

- M. I. Q. Tonmoy et al., “Identification of novel inhibitors of high affinity iron permease (FTR1) through implementing pharmacokinetics index to fight against black fungus: An in silico approach,” Infection, Genetics and Evolution, vol. 106, p. 105385, 2022. [CrossRef]

- A. Daina, O. Michielin, and V. Zoete, “SwissADME: a free web tool to evaluate pharmacokinetics, drug-likeness and medicinal chemistry friendliness of small molecules,” Sci Rep, vol. 7, no. 1, Art. no. 1, 2017. [CrossRef]

- C. A. Lipinski, F. Lombardo, B. W. Dominy, and P. J. Feeney, “Experimental and computational approaches to estimate solubility and permeability in drug discovery and development settings,” Advanced Drug Delivery Reviews, vol. 23, no. 1–3, pp. 3–25, Jan. 1997. [CrossRef]

- G. R. Bickerton, G. V. Paolini, J. Besnard, S. Muresan, and A. L. Hopkins, “Quantifying the chemical beauty of drugs,” Nature Chem, vol. 4, no. 2, pp. 90–98, 2012. [CrossRef]

- J. A. Pradeepkiran, K. Konidala, N. Yellapu, and Bhaskar, “Modeling, molecular dynamics, and docking assessment of transcription factor rho: a potential drug target in Brucella melitensis 16 M,” DDDT, p. 1897, 2015. [CrossRef]

- F. Cheng et al., “admetSAR: A Comprehensive Source and Free Tool for Assessment of Chemical ADMET Properties,” J. Chem. Inf. Model., vol. 52, no. 11, pp. 3099–3105, Nov. 2012. [CrossRef]

- M. J. Abraham et al., “GROMACS: High performance molecular simulations through multilevel parallelism from laptops to supercomputers,” SoftwareX, vol. 1–2, pp. 19–25, 2015. [CrossRef]

- I. H. P. Vieira, E. B. Botelho, T. J. de Souza Gomes, R. Kist, R. A. Caceres, and F. B. Zanchi, “Visual dynamics: a WEB application for molecular dynamics simulation using GROMACS,” BMC Bioinformatics, vol. 24, no. 1, Art. no. 1, 2023. [CrossRef]

- J. Wang, R. M. Wolf, J. W. Caldwell, P. A. Kollman, and D. A. Case, “Development and testing of a general amber force field,” J Comput Chem, vol. 25, no. 9, pp. 1157–1174, 2004. [CrossRef]

- L. Kagami, A. Wilter, A. Diaz, and W. Vranken, “The ACPYPE web server for small-molecule MD topology generation,” Bioinformatics, vol. 39, no. 6, p. btad350, 2023. [CrossRef]

- J. Wang, W. Wang, P. A. Kollman, and D. A. Case, “Automatic atom type and bond type perception in molecular mechanical calculations,” Journal of Molecular Graphics and Modeling, vol. 25, no. 2, pp. 247–260, 2006. [CrossRef]

- W. L. Jorgensen, J. Chandrasekhar, J. D. Madura, R. W. Impey, and M. L. Klein, “Comparison of simple potential functions for simulating liquid water,” The Journal of Chemical Physics, vol. 79, no. 2, pp. 926–935, 1983. [CrossRef]

- J.-P. Ryckaert, G. Ciccotti, and H. J. C. Berendsen, “Numerical integration of the cartesian equations of motion of a system with constraints: molecular dynamics of n-alkanes,” Journal of Computational Physics, vol. 23, no. 3, pp. 327–341, 1977. [CrossRef]

- X.-Y. Meng, H.-X. Zhang, M. Mezei, and M. Cui, “Molecular docking: a powerful approach for structure-based drug discovery,” Curr Comput Aided Drug Des, vol. 7, no. 2, pp. 146–157, 2011. [CrossRef]

- G. Bulusu and G. R. Desiraju, “Strong and Weak Hydrogen Bonds in Protein–Ligand Recognition,” J Indian Inst Sci, vol. 100, no. 1, pp. 31–41, 2020. [CrossRef]

- S. Mishra and R. Dahima, “IN VITRO ADME STUDIES OF TUG-891, A GPR-120 INHIBITOR USING SWISS ADME PREDICTOR,” Journal of Drug Delivery and Therapeutics, vol. 9, no. 2-s, Art. no. 2-s, 2019. [CrossRef]

- A. Harvey, “Natural Products in Drug Discovery and Development. 27-28 June 2005, London, UK,” IDrugs, vol. 8, no. 9, pp. 719–721, Sep. 2005.

- A. K. Srivastava, M. Tewari, H. S. Shukla, and B. K. Roy, “In Silico Profiling of the Potentiality of Curcumin and Conventional Drugs for CagA Oncoprotein Inactivation,” Arch Pharm (Weinheim), vol. 348, no. 8, pp. 548–555, 2015. [CrossRef]

- D. Bisht, D. Prakash, and A. Shakya, “Computational Analysis of Pharmacokinetics, Bioactivity and Toxicity Profiling of Some Selected Ovulation-Induction Agents Treating Polycystic Ovary Syndrome (PCOS),” International Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences and Research, vol. 14, p. 2522, 2023. [CrossRef]

- H. A. Zhong, “ADMET Properties: Overview and Current Topics,” in Drug Design: Principles and Applications, A. Grover, Ed., Singapore: Springer, pp. 113–133, 2017. [CrossRef]

- T. Lynch and A. Price, “The Effect of Cytochrome P450 Metabolism on Drug Response, Interactions, and Adverse Effects,” Cytochrome P, vol. 76, no. 3, 2007.

- N. A. Durán-Iturbide, B. I. Díaz-Eufracio, and J. L. Medina-Franco, “In Silico ADME/Tox Profiling of Natural Products: A Focus on BIOFACQUIM,” ACS Omega, vol. 5, no. 26, pp. 16076–16084, 2020. [CrossRef]

- B. T. Priest, I. M. Bell, and M. L. Garcia, “Role of hERG potassium channel assays in drug development,” Channels (Austin), vol. 2, no. 2, pp. 87–93, 2008. [CrossRef]

- S. Wang, H. Sun, H. Liu, D. Li, Y. Li, and T. Hou, “ADMET Evaluation in Drug Discovery. 16. Predicting hERG Blockers by Combining Multiple Pharmacophores and Machine Learning Approaches,” Mol Pharm, vol. 13, no. 8, pp. 2855–2866, 2016. [CrossRef]

- L. Martínez, “Automatic identification of mobile and rigid substructures in molecular dynamics simulations and fractional structural fluctuation analysis,” PLoS One, vol. 10, no. 3, p. e0119264, 2015. [CrossRef]

| No | PubChem ID | Compounds name |

|---|---|---|

| Control | 146676953 | BI-0115/9-chloranyl-5-propyl-11~{H}-pyrido [2,3-b][1,4]benzodiazepin-6-one |

| 1 | 5281718 | Polydatin |

| 2 | 175265433 | Curcumin |

| 3 | 5881 | Dehydroepiandrosterone/Prasterone |

| 4 | 91439 | Smilagenin |

| 5 | 5742590 | Daucosterol |

| 6 | 16078 | Tetrahydrocannabinol |

| 7 | 30219 | Cannabichromene |

| 8 | 644019 | Cannabidiol |

| 9 | 2543 | Cannabinol |

| 10 | 132279092 | 3,5′-Dimethoxy-resveratrol |

| 11 | 72344 | Nobiletin |

| 12 | 96118 | 4′,5,6,7-Tetramethoxyflavone |

| 13 | 96539 | Gardenin’ B |

| 14 | 96892 | 6-(diethylamino)pyridine-3-carboxamide |

| 15 | 97332 | Quercetin pentamethyl ether |

| 16 | 136417 | 5-Hydroxy-3,6,7,8,3′,4′-hexamethoxyflavone |

| 17 | 145659 | Sinensetin |

| 18 | 261592 | 6-(Pyrrolidin-1-yl)pyridine-3-carboxamide |

| 19 | 629965 | Zapotin |

| 20 | 3010100 | 4′-Hydroxy-5,6,7,8-tetramethoxyflavone |

| 21 | 3031415 | 6-(Cyclohexylamino)pyridine-3-carboxamide |

| 22 | 5315263 | Casticin |

| 23 | 5352005 | Retusin |

| 24 | 132228215 | N-(1-(1-(L-alanyl)piperidine-4-yl)ethyl)-6-aminonicotinamide |

| 25 | 9500 | 6-Aminonicotinamide |

| 26 | 5458896 | scirpusinA |

| Molecules | Compounds name | Docking score (Kcal/mol) |

|---|---|---|

| Control | BI-0115 | -6.55 |

| 1 | Polydatin | -5.97 |

| 2 | Curcumin | -7.84 |

| 3 | Dehydroepiandrosterone or Prasterone | -8.37 |

| 4 | Smilagenin | -8.56 |

| 5 | Daucosterol | -7.05 |

| 6 | Tetrahydrocannabinol | -7.15 |

| 7 | Cannabichromene | -7.48 |

| 8 | Cannabidiol | -6.78 |

| 9 | Cannabinol | -8.14 |

| 10 | 3,5′-Dimethoxy-resveratrol | -6.59 |

| 11 | Nobiletin | -6.40 |

| 12 | 4′,5,6,7-Tetramethoxyflavone | -6.29 |

| 13 | Gardenin B | -5.81 |

| 14 | 6-(diethylamino) pyridine-3-carboxamide | -4.89 |

| 15 | Quercetin pentamethyl ether | -6.55 |

| 16 | 5-Hydroxy-3,6,7,8,3′,4′-hexamethoxyflavone | -5.80 |

| 17 | Sinensetin | -6.98 |

| 18 | 6-(Pyrrolidin-1-yl) pyridine-3-carboxamide | -5.75 |

| 19 | Zapotin | -6.70 |

| 20 | 4′-Hydroxy-5,6,7,8-tetramethoxyflavone | -5.86 |

| 21 | 6-(Cyclohexylamino)pyridine-3-carboxamide | -6.58 |

| 22 | Casticin | -6.12 |

| 23 | Retusin | -6.27 |

| 24 | N-(1-(1-(L-alanyl) piperidin-4-yl)ethyl)-6-aminonicotinamide | -5.99 |

| 25 | 6-Aminonicotinamide | -5.88 |

| 26 | ScirpusinA | -7.47 |

| Compounds | Residues | Distance (Å) | Bonds type |

|---|---|---|---|

| Control | Ser72 | 3.89 | Pi-Sigma |

| 3.30 | Carbon | ||

| Ser74 | 3.00 | Conventional hydrogen bond | |

| Phe76 | 5.20 | Pi-Pi T-Shaped | |

| Ile71 | 5.12 | Pi-Alkyl | |

| 3.87 | Alkyl | ||

| Phe78 | 4.99 | Pi-Alkyl | |

| Prasterone | Ile25 | 4.54 | Alkyl |

| Leu33 | 4.52 | Alkyl | |

| Ala70 | 4.58 | Alkyl | |

| Tyr73 | 5.29 | Conventional hydrogen bond | |

| Smilagenin | Cys31 | 5.45 | Alkyl |

| Pro21 | 5.46 | Alkyl | |

| 5.16 | Alkyl | ||

| Lys143 | 2.18 | Conventional hydrogen bond | |

| 2.07 | Donor-donor | ||

| Lys142 | 5.24 | Alkyl | |

| 5.18 | Alkyl | ||

| Ala18 | 3.78 | Alkyl | |

| 2.42 | Conventional hydrogen bond | ||

| Cannabinol | Gln68 | 1.83 | Conventional hydrogen bond |

| Ser72 | 4.47 | Amide Pi-Stacked | |

| Phe78 | 4.99 | Pi-Alkyl | |

| Phe76 | 4.68 | Pi-Alkyl | |

| Arg124 | 4.04 | Alkyl | |

| Ile71 | 4.15 | Alkyl |

| Compounds | MW(g/mol) | iLOGP | H-bonds donors | H-bonds acceptors | TPSA(Å2) | Heavy atoms | Rotatable bonds | Alerts | |

| Pains | Brenk | ||||||||

| Control | 287.74 | 2.74 | 1 | 2 | 50.68 | 20 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| Cannabinol | 310.43 | 3.94 | 1 | 2 | 29.46 | 23 | 4 | 0 | 0 |

| Prasterone | 288.42 | 2.89 | 1 | 2 | 37.30 | 21 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Smilagenin | 416.64 | 4.42 | 1 | 3 | 38.69 | 30 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Compounds | Molinspiration bioactivity score | GCPR ligand | Ion channel modulator | Kinase inhibitor | Nuclear receptor ligand | Protease inhibitor | Enzyme inhibitor |

| Control | v2022.08 | 0.13 | 0.04 | 0.05 | -0.54 | -0.56 | 0.41 |

| Cannabinol | v2022.08 | 0.50 | 0.02 | -0.08 | 0.60 | 0.11 | 0.22 |

| Prasterone | v2022.08 | 0.07 | 0.01 | -0.60 | 0.90 | -0.04 | 0.82 |

| Smilagenin | v2022.08 | 0.13 | 0.15 | -0.41 | 0.50 | 0.11 | 0.59 |

| Compounds | Water solubility (mg/ml) | GI absorption | P-gp substrate | Skin permeation (cm/s) | BBB permeant | CYP1A2 inhibitor | CYP2D6 inhibitor | CYP3A4 inhibitor | CYP2C9 inhibitor |

| Control | -4.15 | High | No | -5.68 | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes |

| Cannabinol | -5.74 | High | Yes | -3.86 | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No |

| Prasterone | -3.66 | High | No | -5.77 | Yes | No | No | No | No |

| Smilagenin | -6.51 | High | No | -4.23 | Yes | No | No | No | No |

| Parameters | Molecules | |||

| Control | Cannabinol | Prasterone | Smilagenin | |

| Ames mutagenesis | No | No | No | No |

| LD50 (mg/kg) | 1500 (Class 4) | 13500 (Class 6) | 8800 (class 6) | 2600 (class 5) |

| Acute Oral Toxicity (c) | II | III | IV | III |

| Carcinogenicity (binary) | No | No | No | No |

| Carcinogenicity (trinary) | Nonrequired | Nonrequired | Warning | Nonrequired |

| Hepatotoxicity | Yes | No | Yes | No |

| hERG inhibition | No | Yes | No | No |

| Skin sensitization | No | No | Yes | No |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).