1. Introduction

Wind gustiness is important in piloting for many fixed-wing and rotorcraft operations. Aircraft accidents in mountainous or high elevation locations with impactful gusts include both mountain wave-related and on-airport crosswind cases [

1]. The gust factor in aviation, also referred to as the gust spread, is defined as the difference between the sustained wind and the gust [

2]. An often-recommended technique for fixed-wing aircraft pilots during the short final approach is to add one-half the gust factor to the normal approach speed [

2,

3,

4].

The subset of gusty conditions that may impact aviators at low altitude can include those created by mechanical turbulence caused by local terrain, land-cover, and obstructions such as buildings [

5]. Documented aircraft incidents that specifically include mention of mechanical turbulence in the vicinity of airports are infrequent though there are many in which gusts are a factor. National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) reports, which note mechanical turbulence from terrain or buildings in fixed-wing aircraft incidents on takeoff or landing are included in

Table 1. An incident at the Hutchinson County Airport (BGD), Borger, Texas, for example, notably included reference to "strong updrafts from unusual landforms” on short final approach on runway 21 [

6]. The NASA Aviation Safety Reporting System (ASRS) [

7] additionally has reports which include references to mechanical and orographic turbulence in the vicinity of airports and are included in

Table A1 for fixed-wing aircraft, though such references do not necessarily indicate the mechanical turbulence was a contributing factor to the reported event.

The meteorological usage of the gust factor, particularly when characterizing surface roughness, is formulated as a ratio between the gust and the sustained wind and is applied to many applications, ranging from tropical cyclone winds to fire weather forecasting [

8,

9,

10,

11]. Natural or human-made obstructions can significantly impact the representativeness of observed sustained winds and gusts. When local obstructions affect wind measurements, the World Meteorological Organization (WMO) and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) recommend siting the wind sensor higher than the standard level of approximately 10 m [

12,

13]. Gust factors in this context have been used to filter out unrepresentative observations [

14]. Additionally, gust reporting from ASOS systems differ in terms of what is transmitted via Aviation Routine Weather Reports in METAR and SPECI formats versus the higher temporal resolution one-minute ASOS observations. The METAR/SPECI reports gust reporting has, amongst other criteria, a minimum allowable gust report of 14 knots [

15], whereas the one-minute ASOS wind gust reports the mean wind and gust without restriction at 1 kt resolution. Additionally, the one-minute ASOS reports the wind directions at 1 deg resolution versus the 10 deg resolution in METAR/SPECI reports.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. ASOS Data

Analysis of gustiness was achieved using six years (2019-2024) of one-minute ASOS observations of average and peak 3-s wind from 20 stations arbitrarily selected from across the contiguous U.S. (

Table 2). 2023 National Land Cover Database (NCLD) data was obtained via the Multi-Resolution Land Characteristics (MRLC) Consortium (

https://www.mrlc.gov/data) and was used to calculate the percentage of land cover that was the combined low, medium, and high-intensity developed regions, as well as the combined percentage of forested areas within 3 km of the ASOS location. These values , included in

Table 2, are meant to give a general impression of the roughness in the vicinity of the ASOS. The one-minute ASOS data were accessed from the National Centers for Environmental Information (NCEI,

https://www.ncei.noaa.gov/pub/data/asos-onemin/).

1 NLCD land cover values are for the combined low, medium, and high intensity developed areas and the combined areas defined as forested within 3km of the ASOS location.

2.2. Aviation and Meteorological Gust Factors

Aviation gust factors (GF

avn) and meteorological gust factors (GF

met) were determined from the sustained and peak wind. A traditional approach was used to defining the GF

avn as the difference between the peak (U

max) and average wind (

U).

For GF

met, a modified approach was taken beginning with an expression in Yu and Chowdhurdy [

16] where a peak factor (g), wind speed standard deviation (SD

u), and average wind (U)are used to obtain the difference between the peak and average wind:

Dividing Equation (2) by the average wind and defining GF

met the ratio of the peak wind to average wind minus one, we obtain the following:

With these definitions, GFmet is simply GFavn normalized by the average wind. Additionally, each gust factor will approach zero as the difference between the peak wind and average wind approach 0, whereas in a traditional formulation the meteorological gust factor limit is 1. Gust factors were averaged by direction in 10-degree bins only if the number of observations were greater than or equal to 10. Also, gust factor estimates were also filtered by minimum gust values (1, 5, 10, 15, 20, and 25 kt) to test the impact of filtering out lower gusts, progressively, akin to the filtered gusts that appear in METAR reports.

3. Results

SOME KIND OF INTRO

3.1. Unfiltered Average Gust Factors by Direction

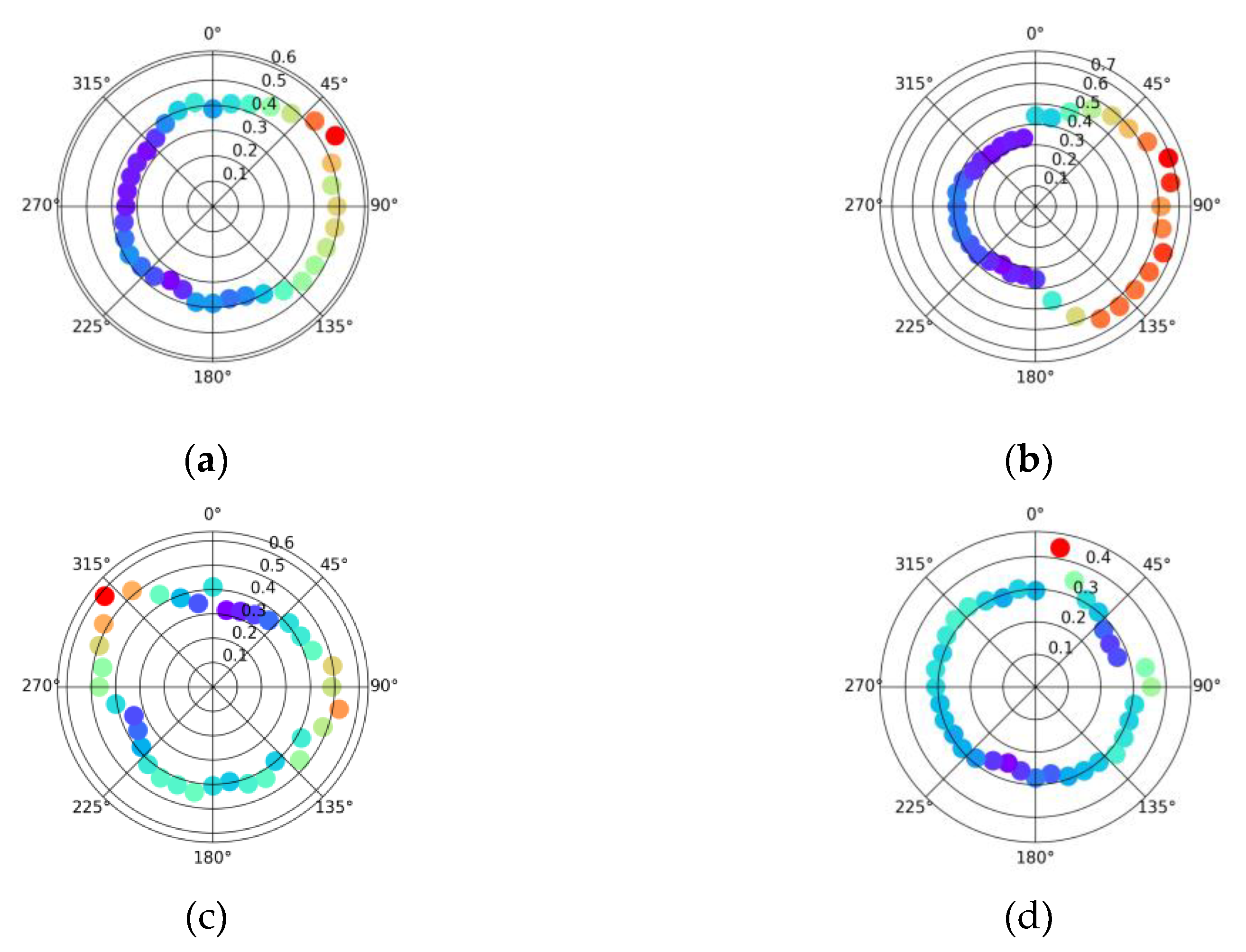

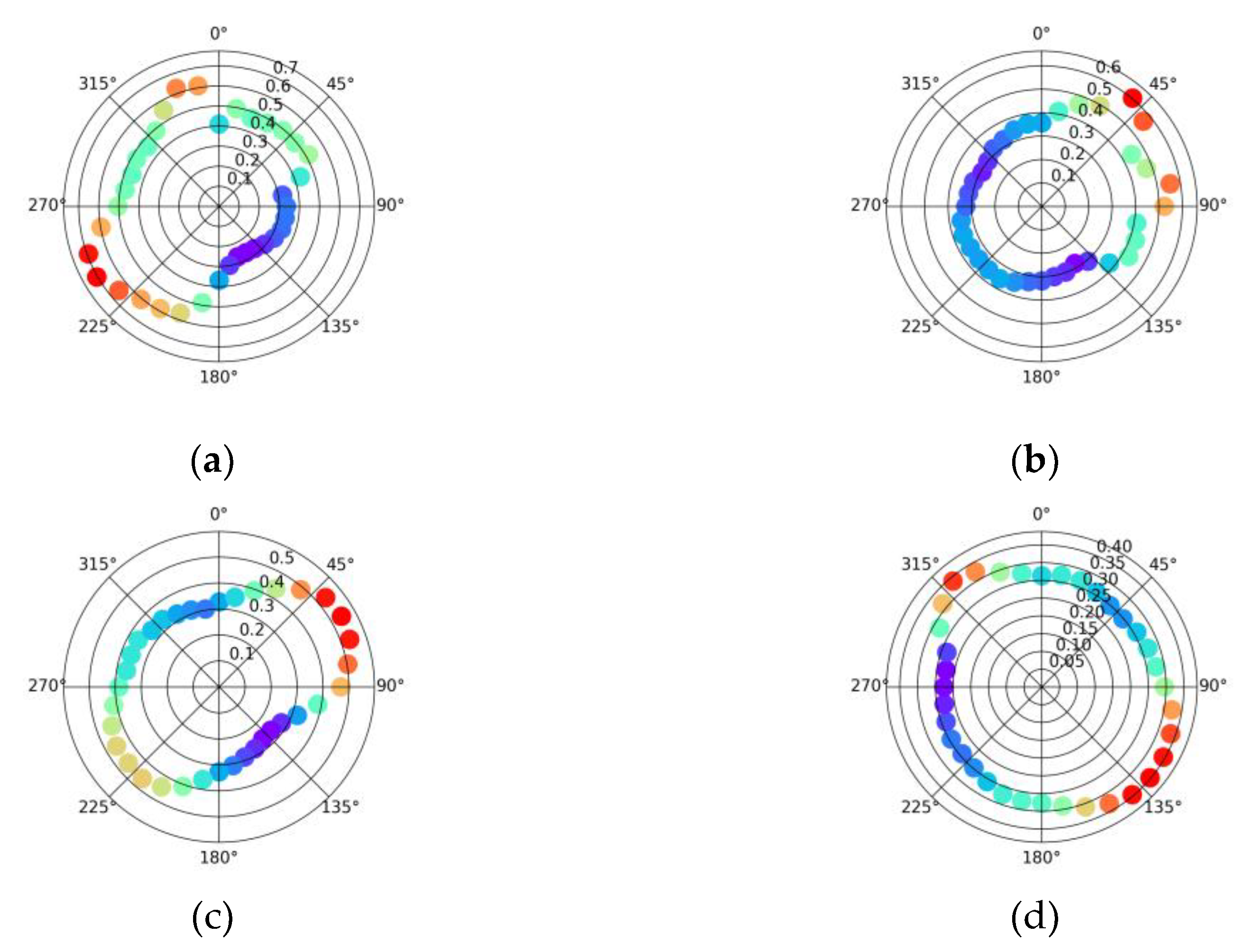

Four locations, three of which have notable impacts from nearby obstacles, are used as a first examination of the differences between average GF

met and GF

avn: KABQ, KDFW, KGLS, and KPAE (Fig. 1). The DFW East Air Traffic Control Tower is about 290 m east of the ASOS. KGLS, which is less developed than KDFW (

Table 2), has a VOR located about 345 m to the west/southwest of the ASOS. KPAE has a large fencing structure 80 m to the southeast of the ASOS. The average GF

met is relatively high (Fig. 2) in each of those directions at each airport because of those obstructions. KABQ has a grouping of hangars and other buildings to the southwest of the ASOS and another zone of buildings to the northeast that account for the broader directions of high GF

met. The lowest values of GF

met at each airport are in directions where the upwind flow has a significant fetch along a runway. A full listing of isolated and/or impactful siting issues are included in

Table A2. Figures depicting GF

met at the remaining locations are included in

Appendix B.

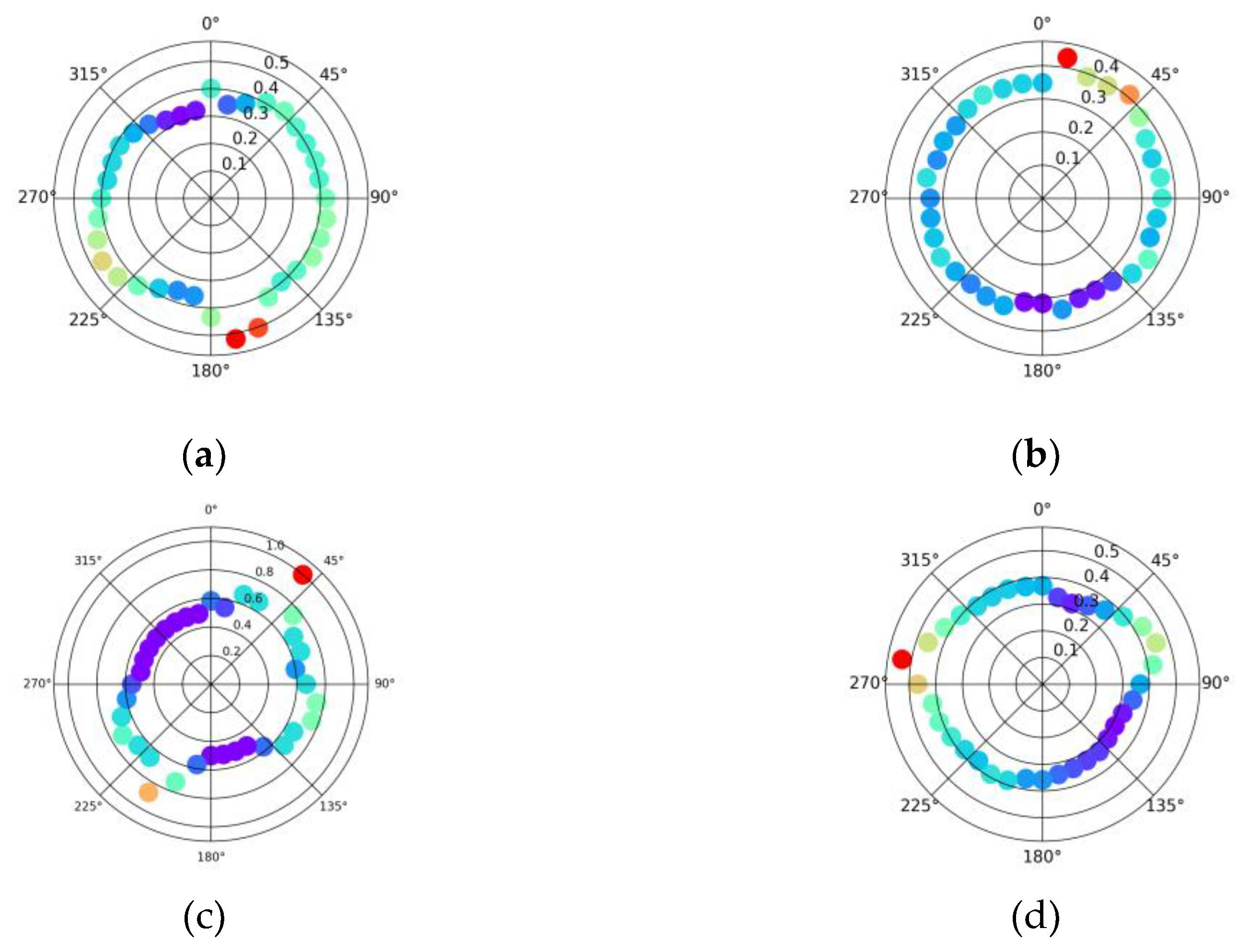

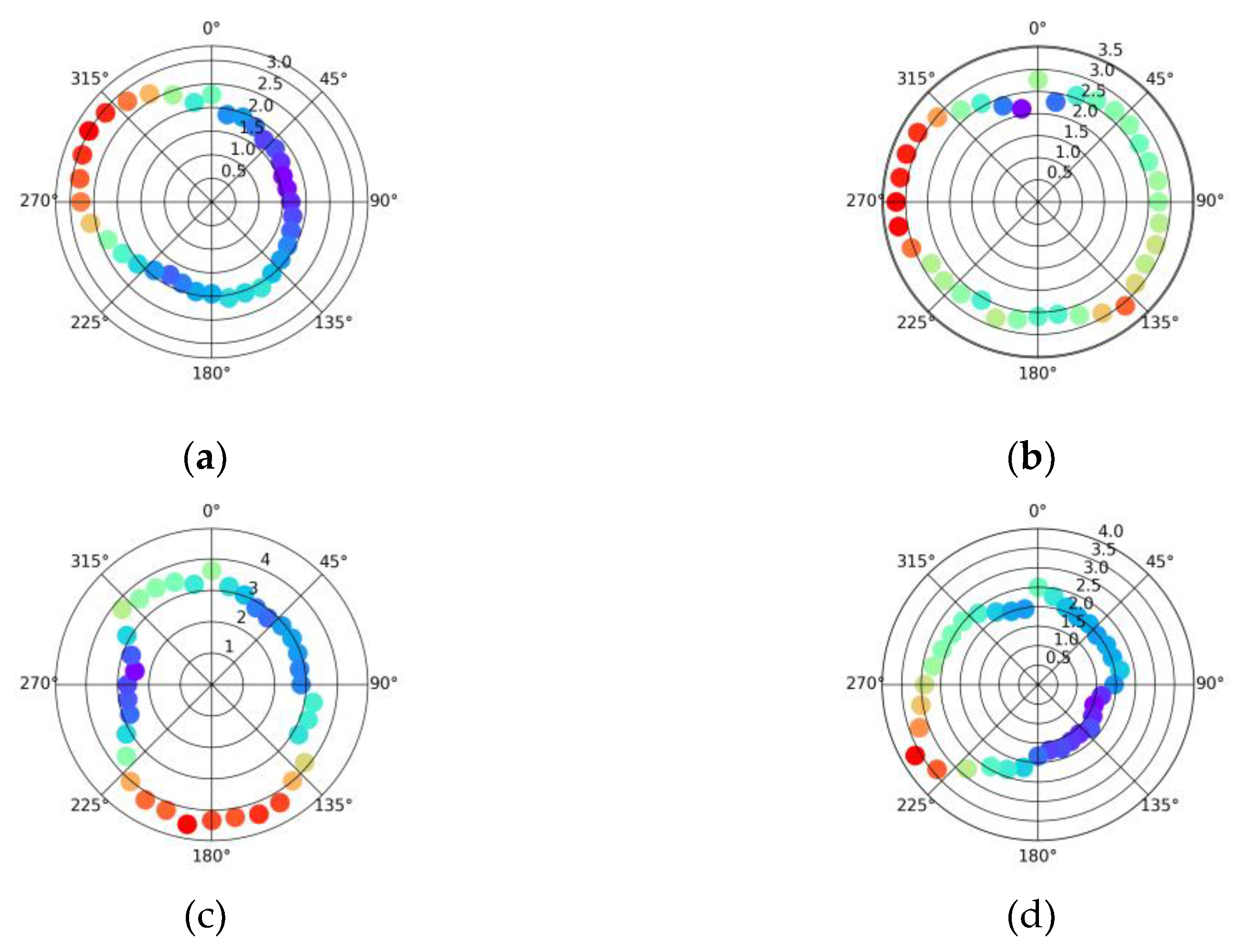

The GF

avn is quite different, directionally, at each airport compared to the GF

met (Fig. 3). KABQ has an exceptionally dramatic increase in GF

avn directly to the east. This enhanced gustiness is presumed to occur from gap winds that flow from Tijeras Canyon [

17]. The highest GF

avn values at the other locations are in line with prevailing wind patterns (unshown). Indications of increased GF

avn in the directions with obstructions are noted for KGLS and KPAE. Figures depicting GF

met at the remaining locations are included in

Appendix C. KONT is another location in which the GF

avn has high values in a specific direction, from the northeast, which is likely due to infrequent Santa Ana wind events (Fig. C.3).

Figure 1.

Satellite views of ASOS locations at a) KABQ, b) KDFW, c) KGLS, and d) KPAE. Map data: Google. Created with QGIS:

http://qgis.osgeo.org.

Figure 1.

Satellite views of ASOS locations at a) KABQ, b) KDFW, c) KGLS, and d) KPAE. Map data: Google. Created with QGIS:

http://qgis.osgeo.org.

Figure 2.

Average GFmet by direction [2019-2004] for a) KABQ, b) KDFW, c) KGLS, and d) KPAE.

Figure 2.

Average GFmet by direction [2019-2004] for a) KABQ, b) KDFW, c) KGLS, and d) KPAE.

Figure 3.

Average GFavn by direction [2019-2004] for a) KABQ, b) KDFW, c) KGLS, and d) KPAE.

Figure 3.

Average GFavn by direction [2019-2004] for a) KABQ, b) KDFW, c) KGLS, and d) KPAE.

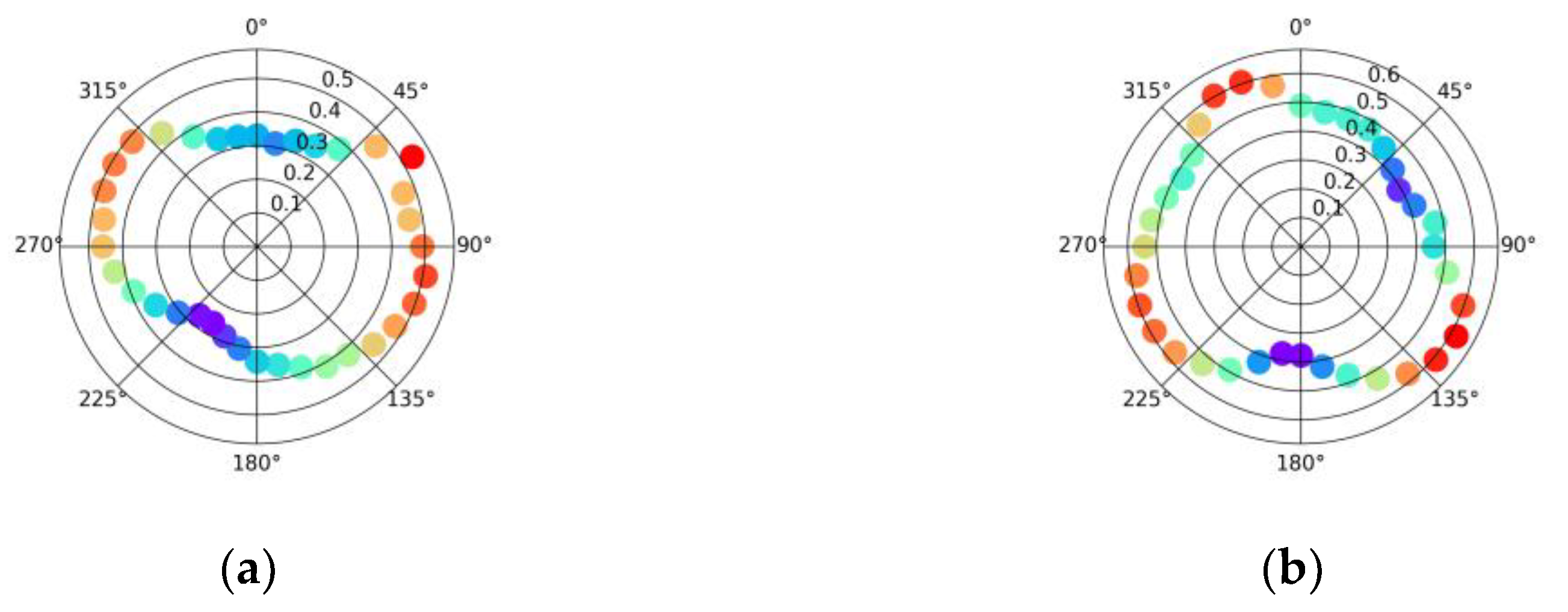

3.2. Filtered Average Gust Factors by Direction

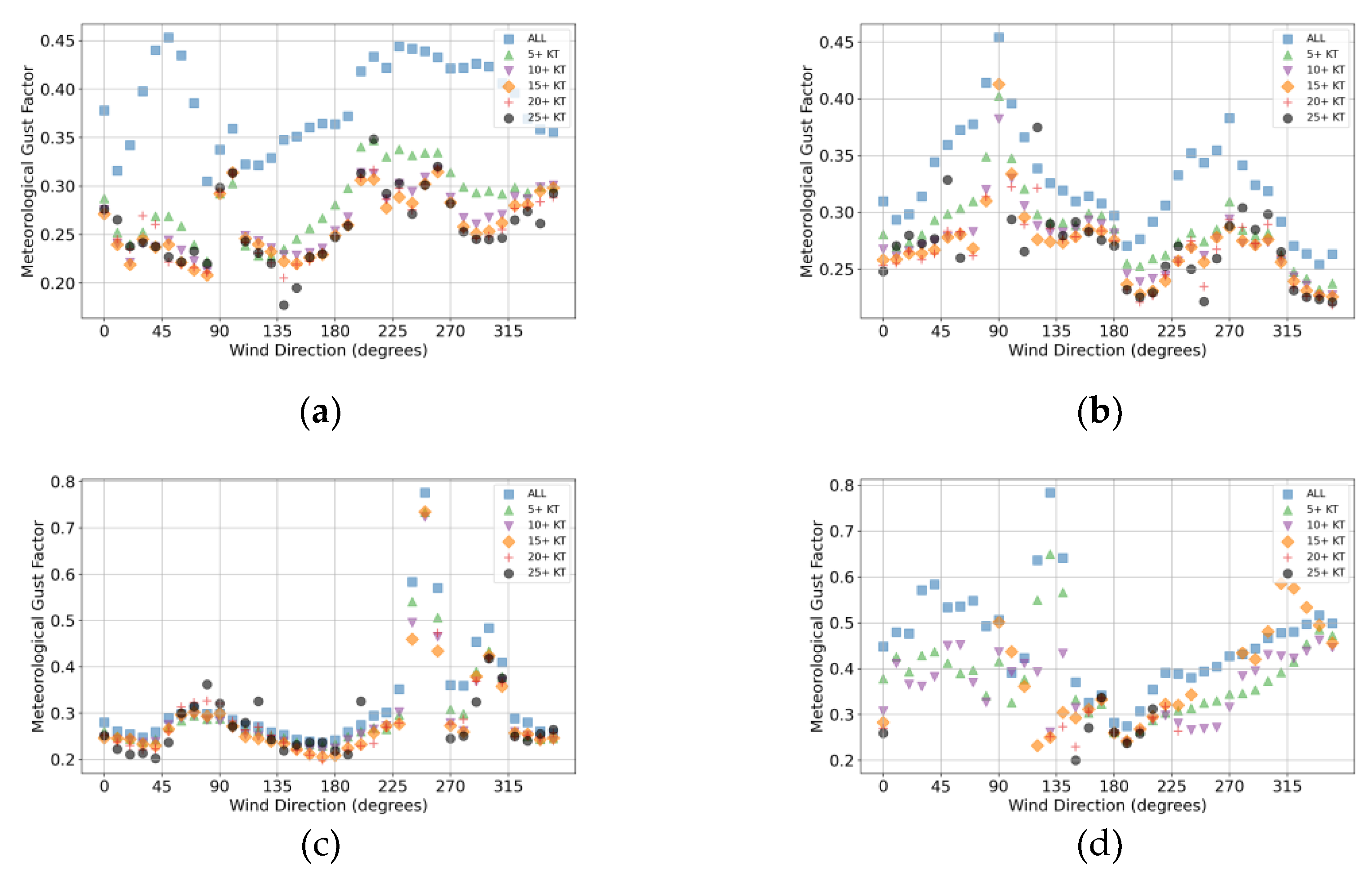

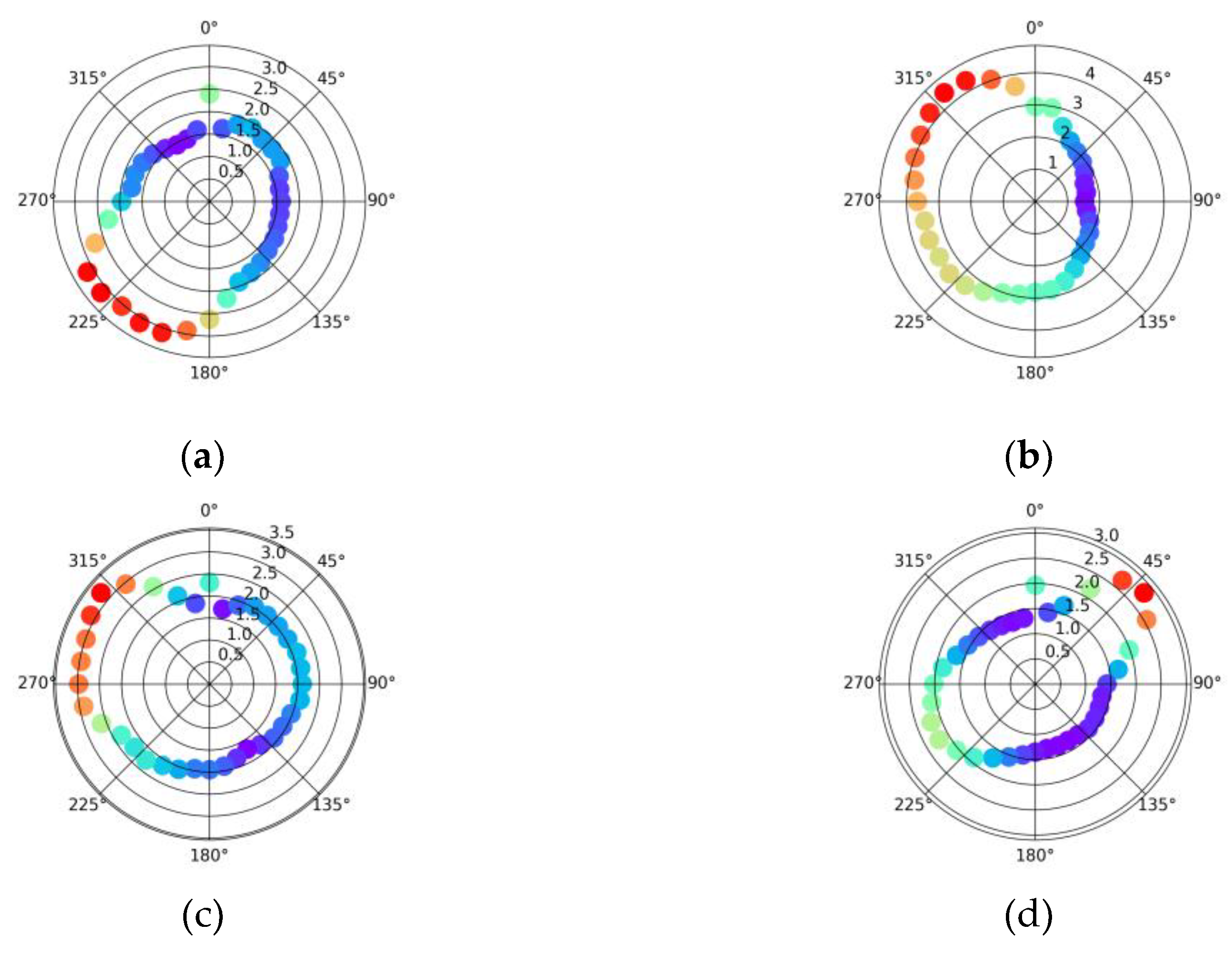

Given that the impact of the obstructions near the ASOS units is less noticeable with GFavn and that the overall gustiness patterns are dissimilar between the two gust factors, filtering of the gusts was conducted by removing gusts under threshold values of 1, 5, 10, 15, 20, and 25 kt. A threshold value of 1 is equivalent to no filtering. A threshold near 15 kt is near the 14 kt minimum gust value in ASOS-generated METAR reports. The impact of filtering of GFmet by 5 kt and greater produced significant differences to the unfiltered estimates, particularly in the direction of developed land cover (Fig. 4). KABQ had large reductions in GFmet, for example, from broad portions of the northeast and southwest sectors. KDFW also has noticeable reductions in GFmet from the west in the direction of terminal development. On the other hand, some of the GFmet values in the direction of prominent obstructions at KDFW, KGLS, and KPAE are still noticeable, and as the filtered value of gusts is increased, GFmet values are not available and are indicative of the obstructions both increasing gustiness but also reducing wind speeds.

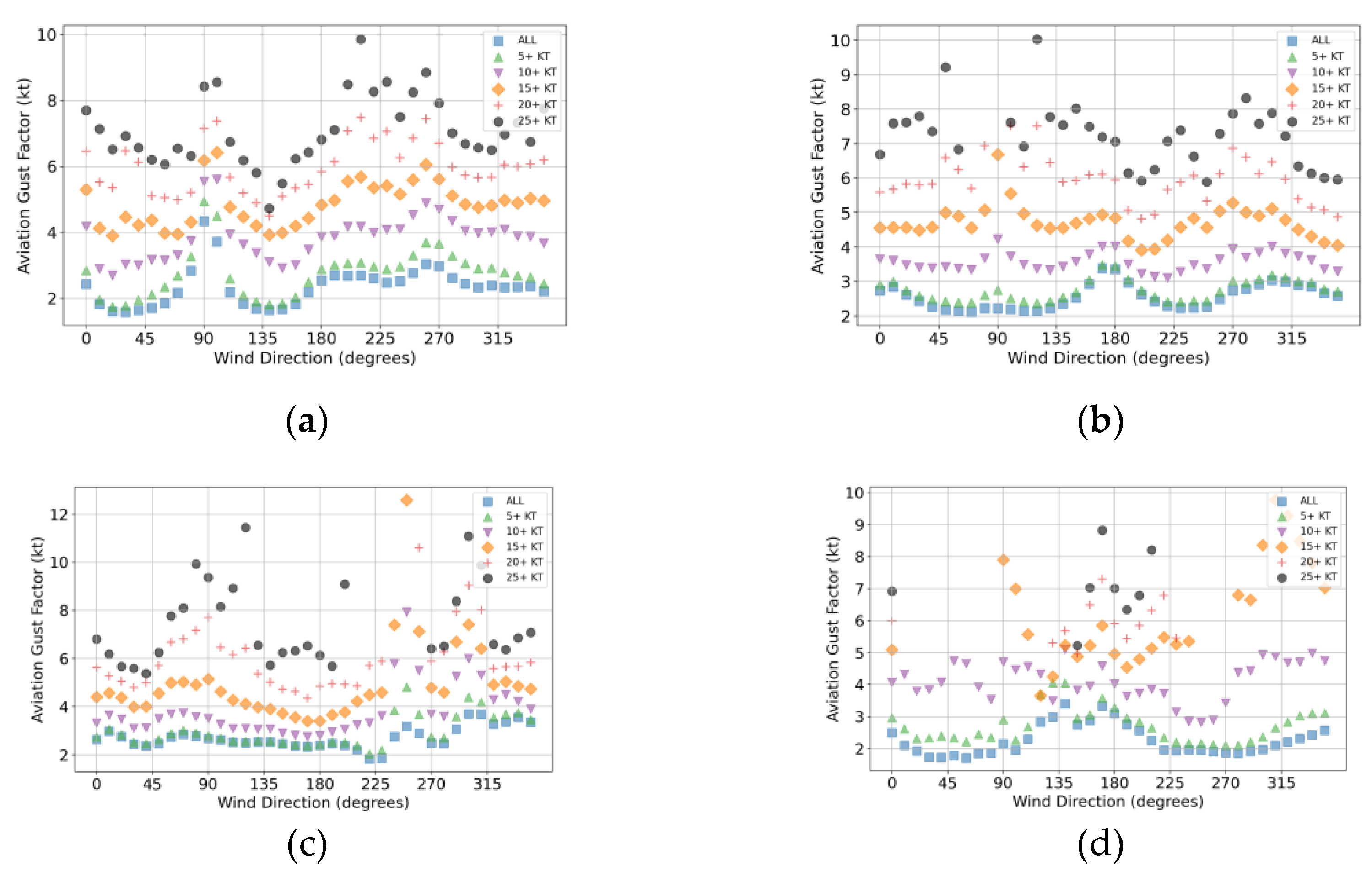

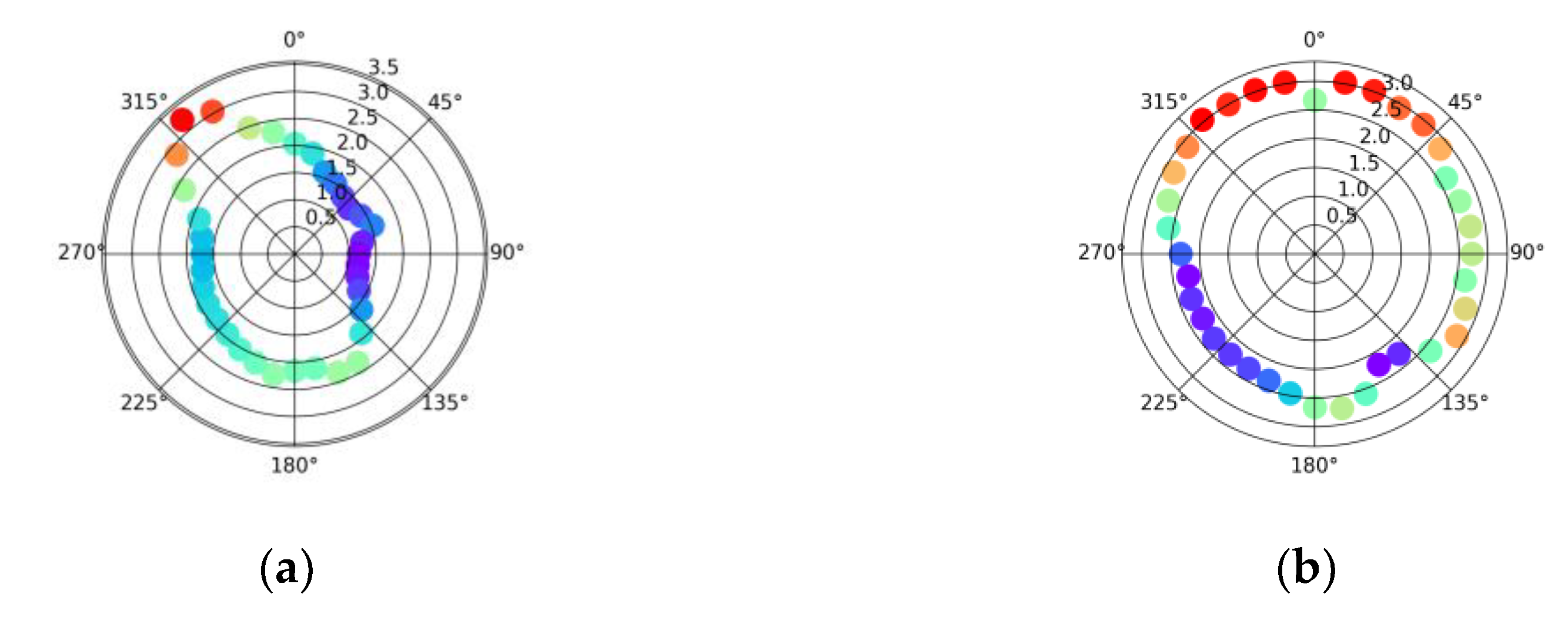

Filtering of GFavn by gust speeds (Fig. 5) produces less dramatic changes in values compared to GFmet. Given that GFavn values aren’t normalized, the values increase as the gust filter value is increased. At KABQ, the gustiness in association with gap winds from the east are noticeable in all levels of filtering. At KDFW, the gustiness associated with the ATC tower to the east becomes more noticeable with increased filtering until gust values stop being reported.

Figure 4.

Average GFmet by direction [2019-2004] for a) KABQ, b) KDFW, c) KGLS, and d) KPAE filtered by gust values: no filtering (blue box), 5+ kt (green triangle), 10+ kt (purple downward triangle), 20+ kt (red plus), and 25+ kt (black circle).

Figure 4.

Average GFmet by direction [2019-2004] for a) KABQ, b) KDFW, c) KGLS, and d) KPAE filtered by gust values: no filtering (blue box), 5+ kt (green triangle), 10+ kt (purple downward triangle), 20+ kt (red plus), and 25+ kt (black circle).

Figure 5.

Average GFavn by direction [2019-2004] for a) KABQ, b) KDFW, c) KGLS, and d) KPAE filtered by gust values: no filtering (blue box), 5+ kt (green triangle), 10+ kt (purple downward triangle), 20+ kt (red plus), and 25+ kt (black circle).

Figure 5.

Average GFavn by direction [2019-2004] for a) KABQ, b) KDFW, c) KGLS, and d) KPAE filtered by gust values: no filtering (blue box), 5+ kt (green triangle), 10+ kt (purple downward triangle), 20+ kt (red plus), and 25+ kt (black circle).

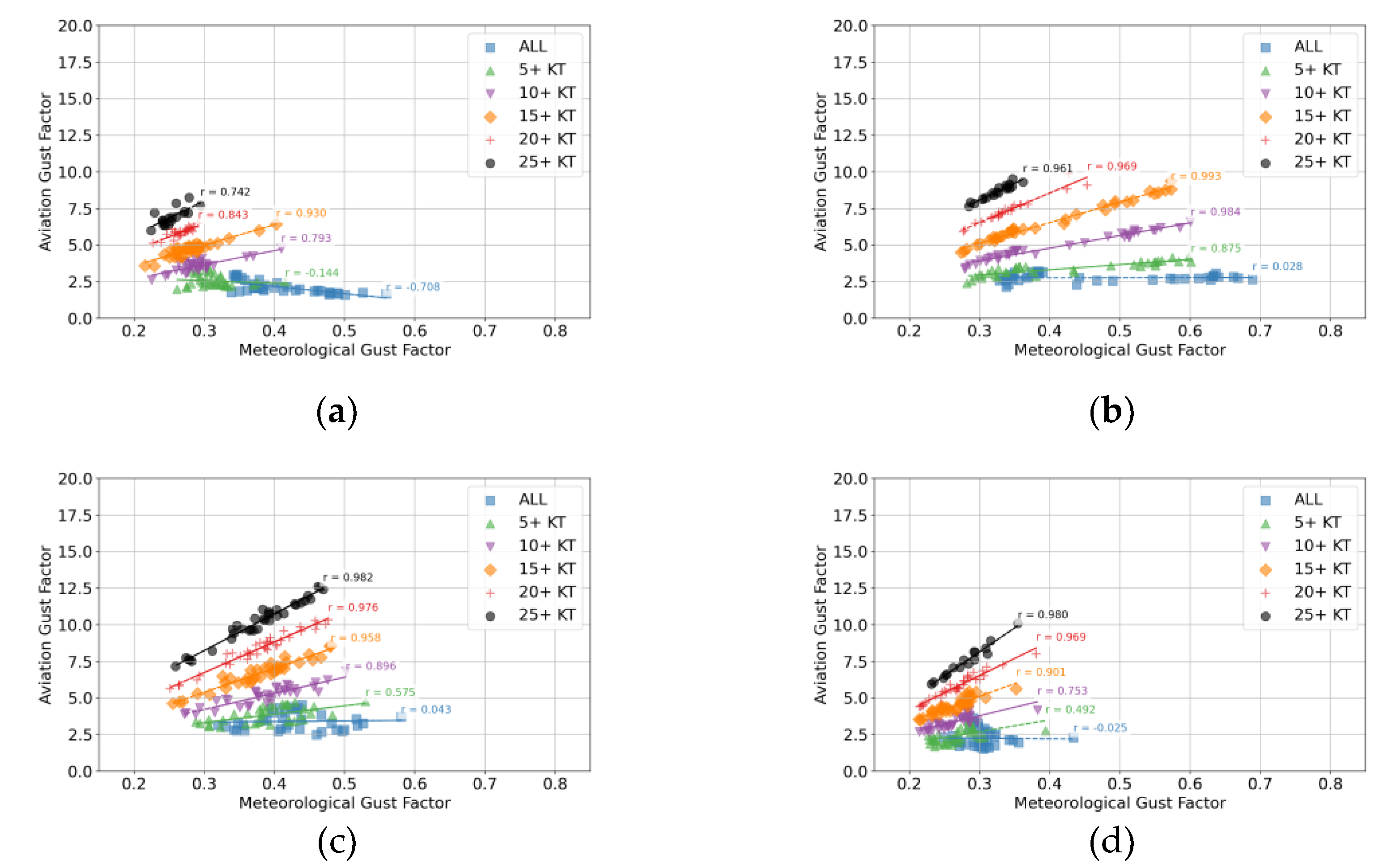

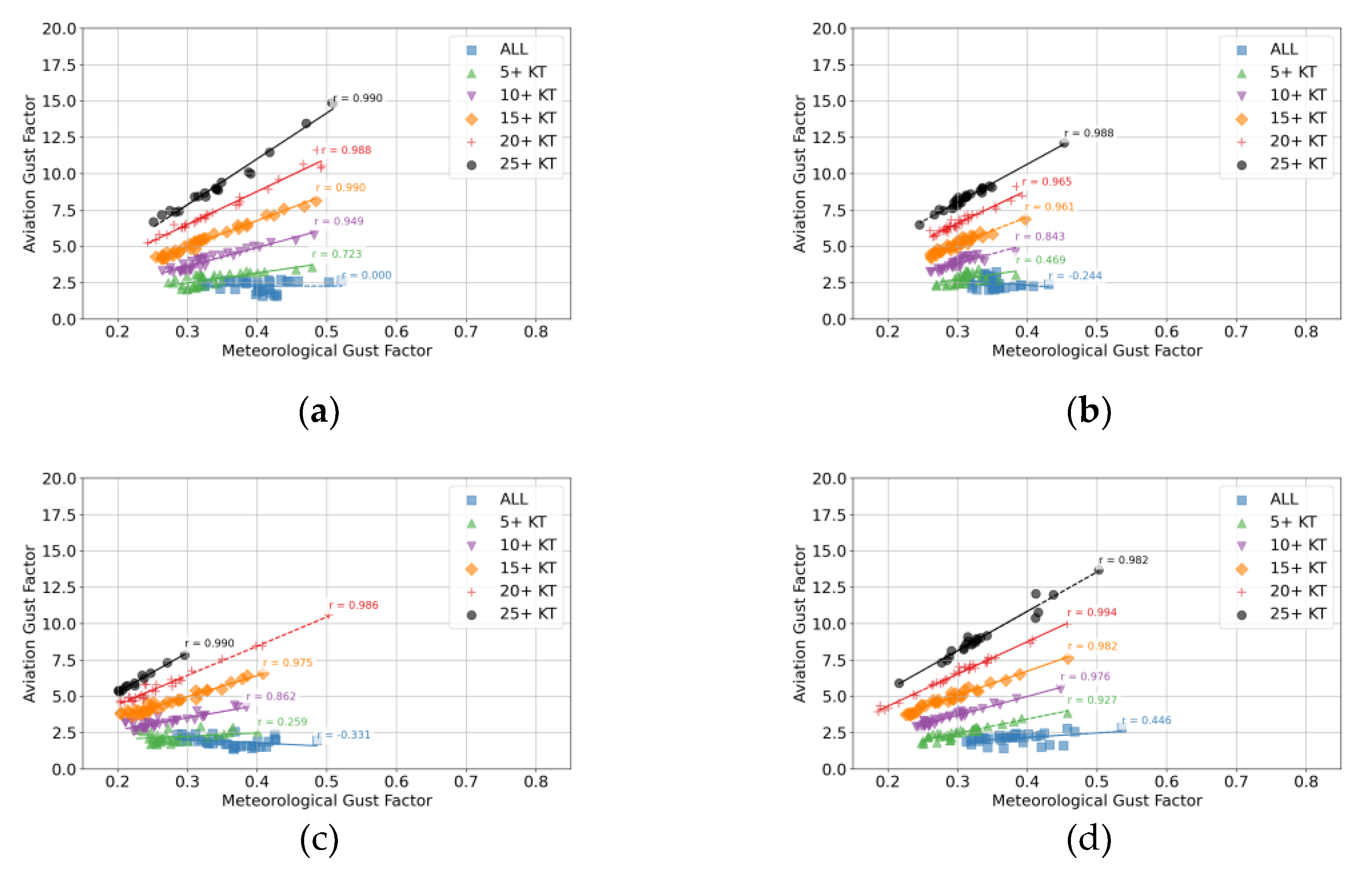

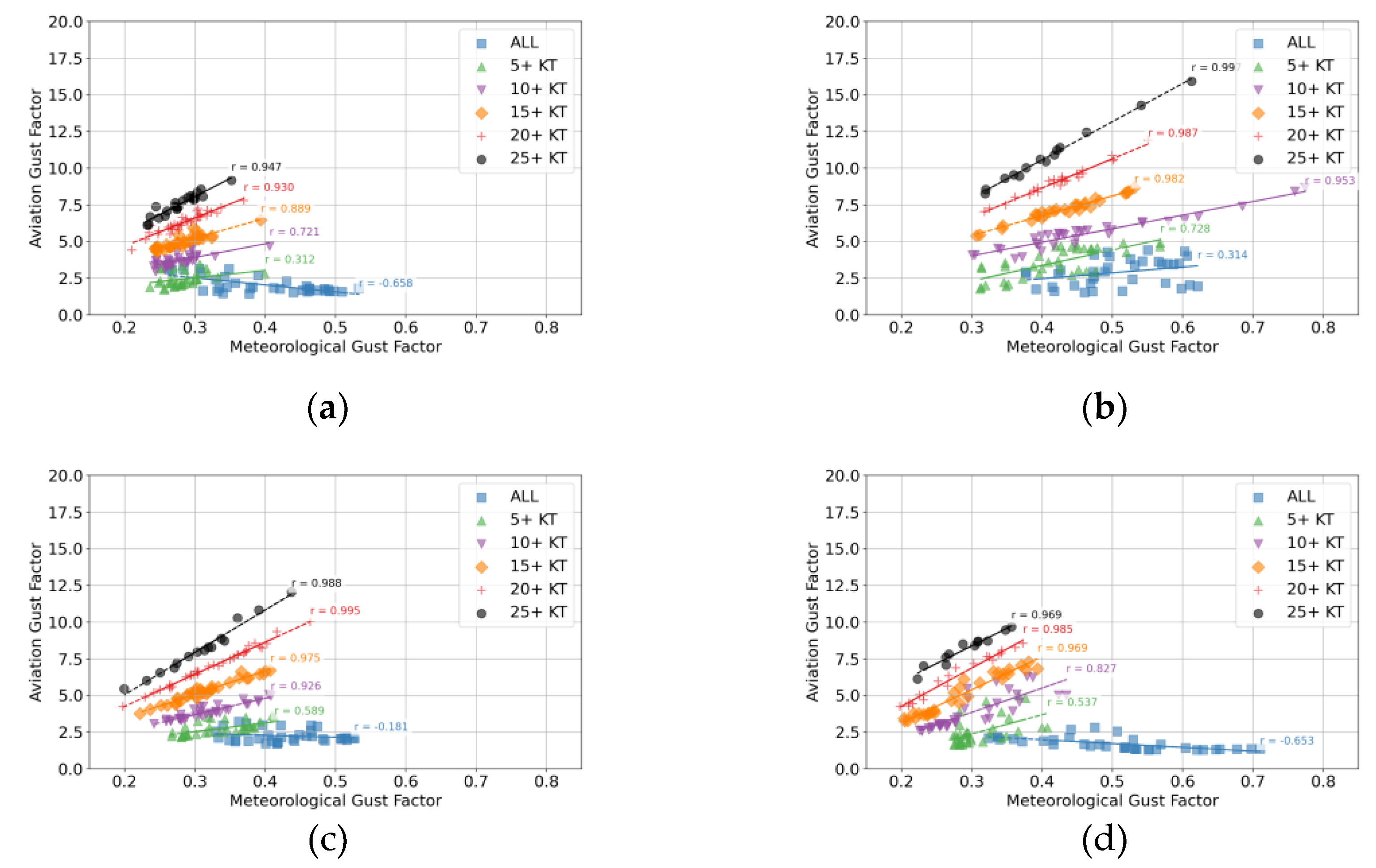

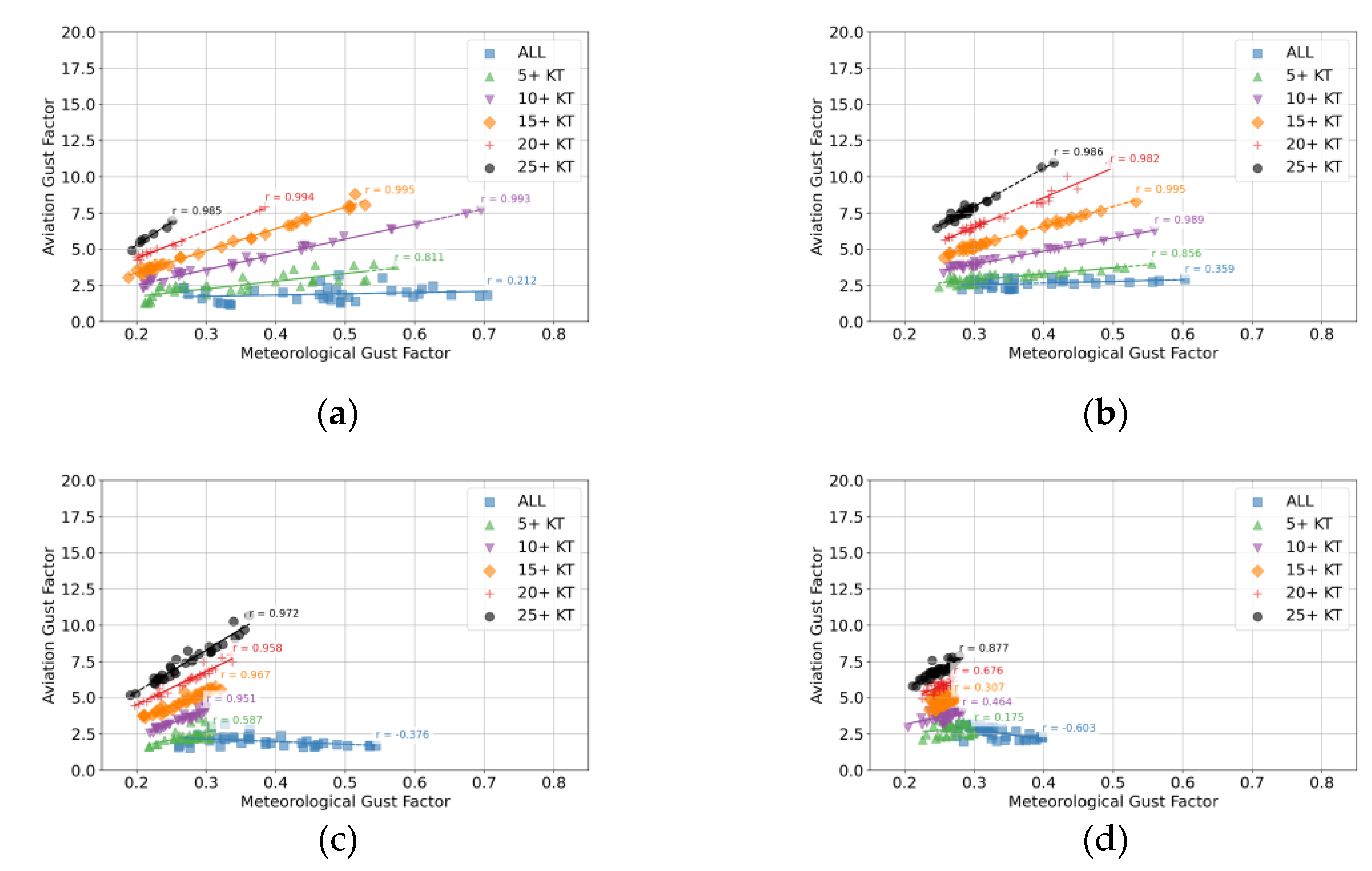

3.3. Correlation Between GFmet and GFavn as a Function of Gust Filtering

Given the impacts of filtering on gust factor values, the correlation between GF

met and GF

avn was assessed using the Pearson correlation coefficient for all locations. Results for KABQ, KDFW, KGLS, and KPAE are included in

Figure 6 and the remaining locations are included in

Appendix D. As the level of filtering is increased, the correlations trend more positive. Peak correlation coefficents for all locations occur with filtering of at least 15 kt or greater with 17 locations having peak correlations coeffients greater than +0.95. The slopes of the best fit lines are also noted to increase with the increased filterng of gusts. This may be simple result of Equation 3, when rearranged, shows that the ratio of GF

avn to GFmet would be equal to the mean wind and which would increase with increased filtering of lower gusts.

Five of the locations (KAOO, KDFW, KIDA, KONT, and KTCC), with no filtering, have robust negative correlations (between -0.5 and -0.7). We speculate that the cause of this negative correlation stems from the following scenario. ASOS systems are typically sited near the landing zone of the primary instrumented runway. This runway will often be well aligned with the prevailing winds, which is often the direction of larger gusts and would produce high GFavn in the directions that the ASOS has a long upwind fetch along the runway and in which GFmet would be minimal. If there is significant development and/or forests to the sides of the runway, the GFmet would be large with fetches perpendicular to the runway. Thus, as GFmet increases, GFavn would decrease in this scenario.

3.4. NTSB Case CEN18LA172 Borger, Texas

The NTSB report for the incident at KBGR on 11 May 2018, which was classified as a loss of control on ground, included the following text:

During a visual approach to runway 21 (3,897 feet by 100 feet, dry asphalt), the pilot stated that he flew an upwind pattern entry and on short final, experienced "strong updrafts from unusual landforms". The pilot landed the tailwheel equipped airplane on runway 21, near the intersection of runway 17/35 (about 1,650 feet down runway 21), and "experienced strong wind gusts causing swerving".

The report also indicated winds were from 220° (southwest) between 23 and 32 kt. Topographic features in the vicinity of the airport in

Figure 7, including to the west and southwest of the intersection of the two runways. Unfiltered GF

met (Fig. B.1) and GF

avn (Fig. C.1) do not indicate high values from the southwest, but GF

met is high from the northwest, which is in the general direction of the terrain features that might have been producing the mechanical turbulence in this incident. The problem is that the high GF

met values observed by the ASOS form the northwest are due to the hangars only 50 m in that direction. Thus, ASOS siting issues can limit the utility for assessing mechanical turbulence for natural obstruction in the vicinity of the airport.

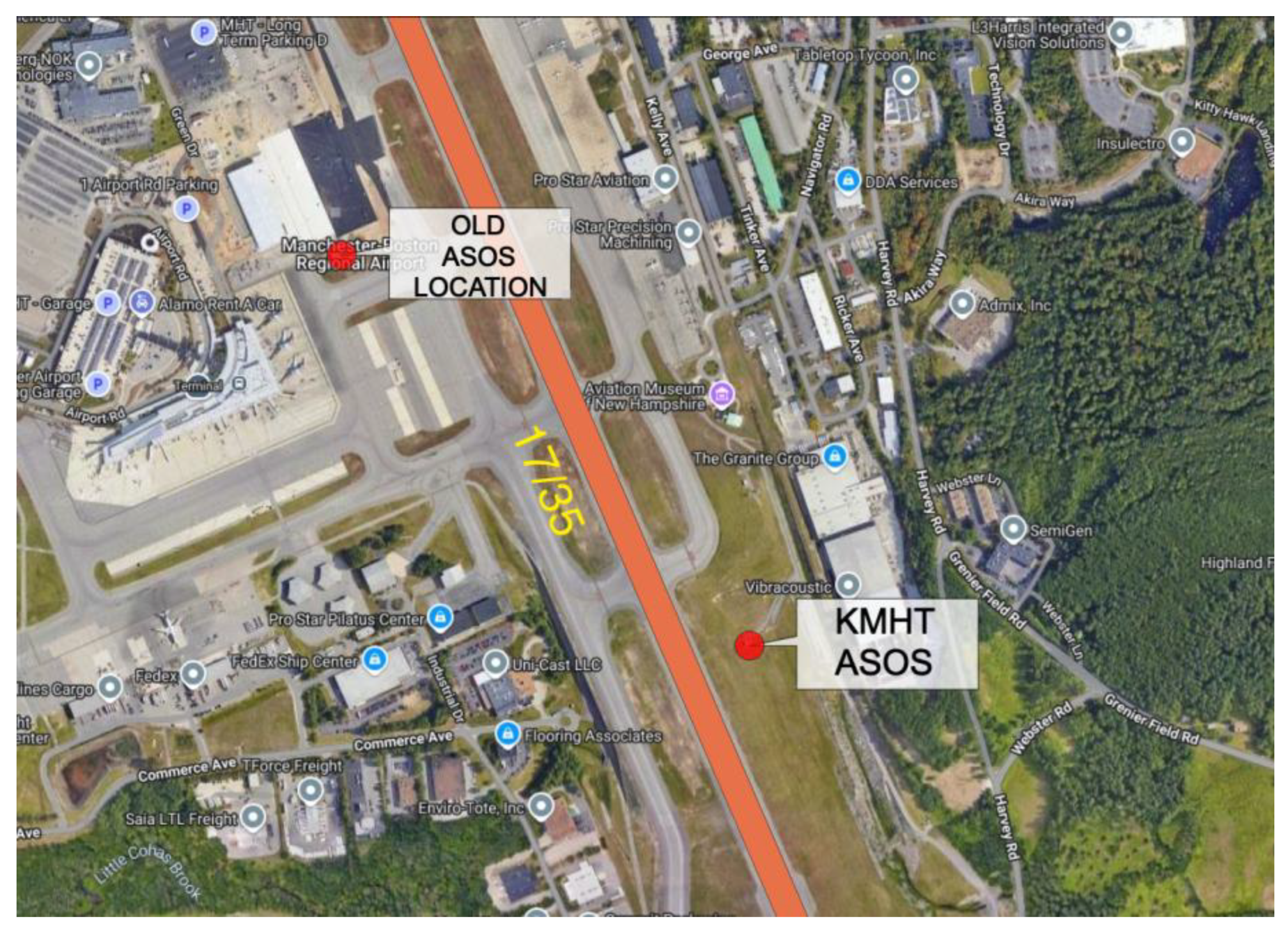

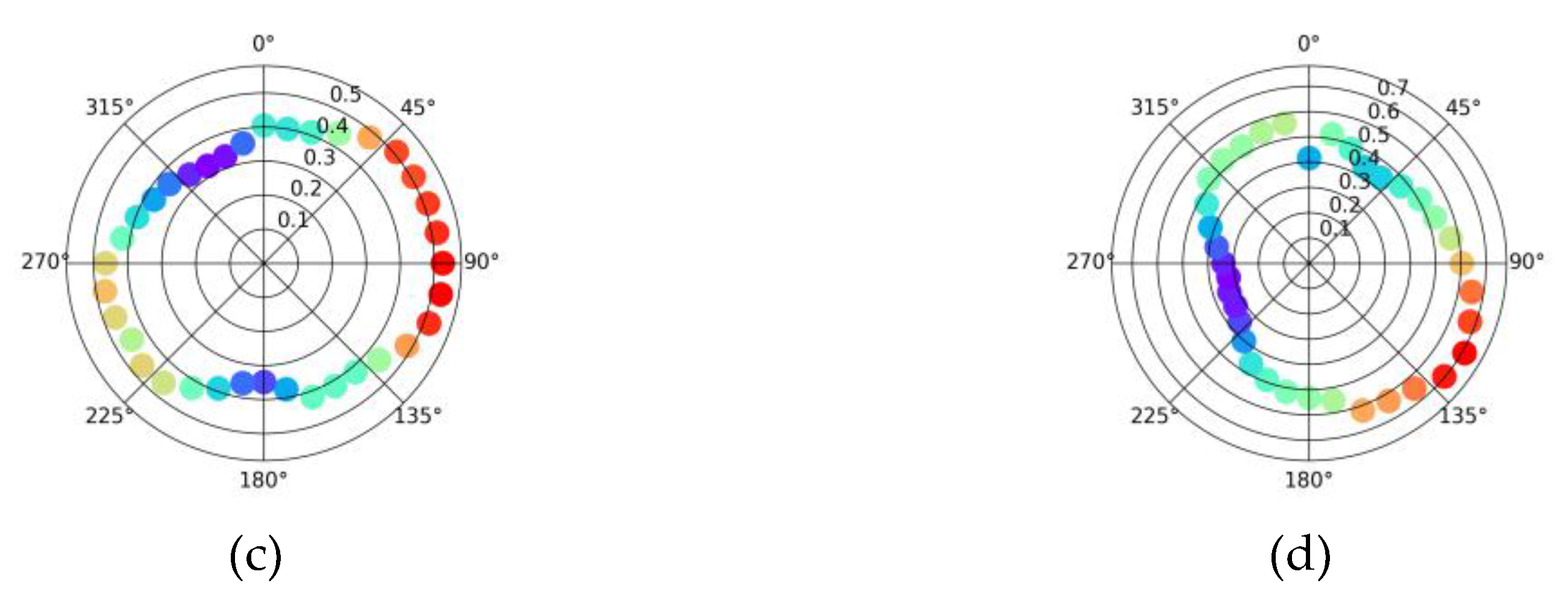

3.4. ASOS Location Change at Manchester-Boston Regional Airport (KMHT)

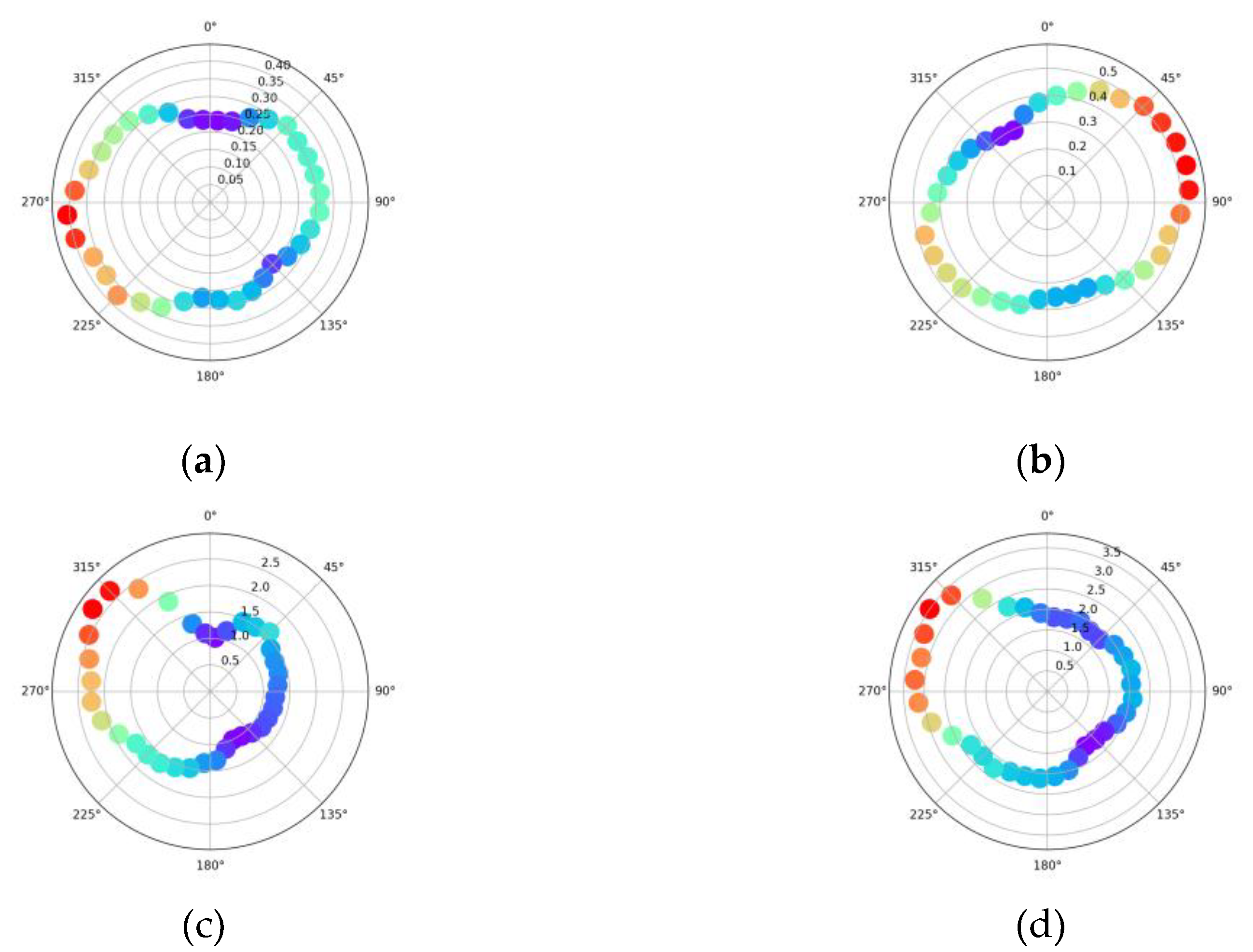

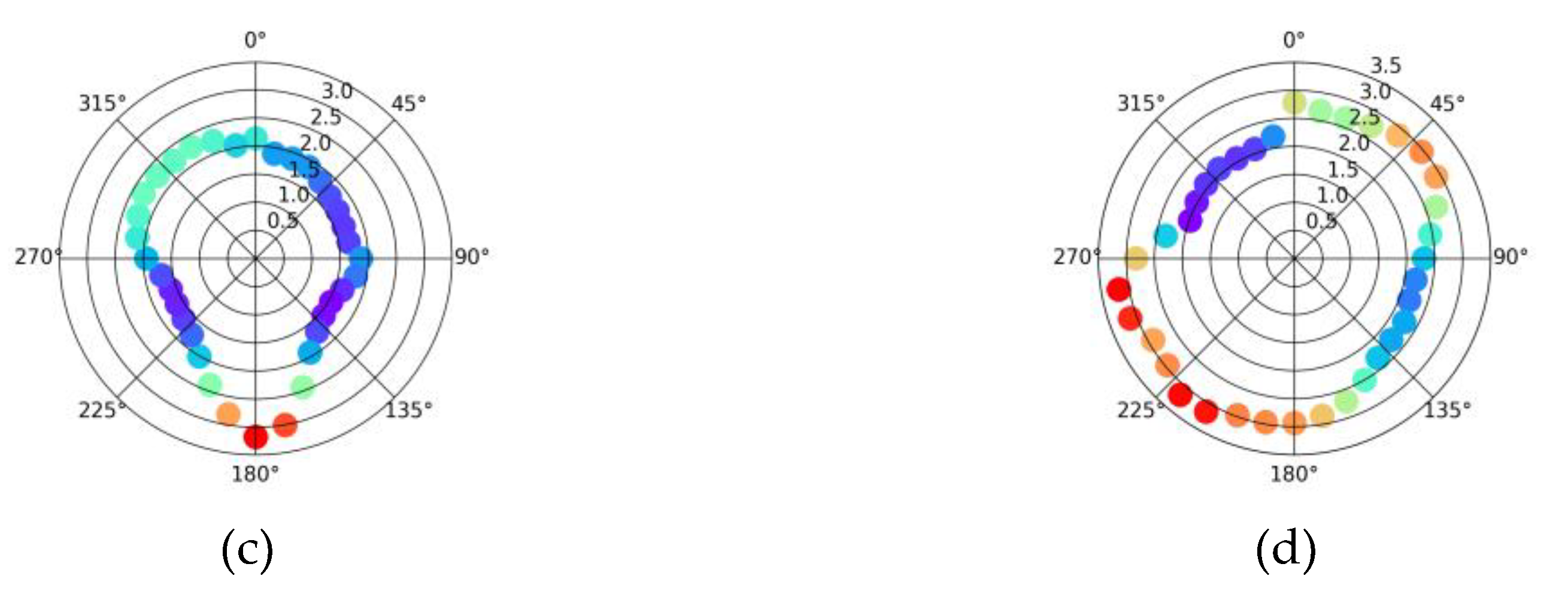

The ASOS unit at KMHT was relocated as part of airport facilities construction in 2022. The old location was positioned on the west side of runway 17/35 with the terminal just to the west, while the new location is positioned further south on the east side of runway 17/35 with major obstructions just to the east (Fig. 8). Analysis of the gustiness in 2021, before the relocation, and in 2025 after the relocation was conducted to test the impacts on the two gust factors. GFmet shows a significant change between the two years with high gustiness values shifting from the west to the east consistent with the change in direction of significant obstructions relative to the ASOS (Fig. 9). On the other hand, GFavn is much less impacted by the relocation with the directional patterns in gustiness largely preserved.

Figure 9.

KMHT gustiness changes due to an ASOS relocation: a) average GFmet by direction for 2021, b) average GFmet by direction for 2024, c) average GFavn by direction for 2021, d) average GFavn by direction for 2024.

Figure 9.

KMHT gustiness changes due to an ASOS relocation: a) average GFmet by direction for 2021, b) average GFmet by direction for 2024, c) average GFavn by direction for 2021, d) average GFavn by direction for 2024.

4. Discussion

Gust factors are used in piloting, in particular by fixed-wing aircraft on final approach, and large values may be caused by mechanical turbulence produced by natural and/or human-made obstructions. Meteorological gust factors are often used to estimate surface roughness conditions for providing standardized wind speed and gusts, for example, in tropical cyclones. Meteorological (GFmet) and aviation gust factors (GFavn) were analyzed from six years of one-minute ASOS observations at 20 airports, including small, medium, large, and non-hub facilities.

A modified version of the meteorological gust factor is used and is shown to be the aviation gust factor normalized by the sustained wind speed. This version allows both gust factors to have minimum values of zero when the gust speed approaches the sustained wind speed.

The averaged GFmet, by direction, is sensitive to local obstructions ranging from smaller nearby airport equipment and small buildings to larger generalized areas of airport development. The averaged GFavn, by direction, is not as responsive to local obstructions, but cases of severe obstruction impact on GFavn are observed to occur. Local obstructions in the vicinity of the ASOS Unit can make the evaluation of mechanical turbulence by natural features of airport development difficult.

GFmet and GFavn, without filtering by gust values, are often poorly correlated, but a subset of airport locations have substantive negative correlations that may be caused by a specific ASOS siting scenario. GFmet and GFavn, when filtered by including only gusts of at least 15 knots, have a generally high correlation.

A case of an ASOS relocation indicated that GFmet directional variation was significantly impacted, but the GFavn directional variation was largely preserved and supports the notion that the GFavn is more representative of larger-scale roughness and/or meteorologically driven gust events.

These findings may be important to the climatological analysis and interpretation of gustiness at aerodromes to advise aviators, attribution of gusts for specific aviation incidents, and assessment of ASOS equipment siting issues.

Author Contributions

Michael Splitt had the main responsibility for all the work in this article. Steven Lazarus contributed to the planning and commenting of the manuscript with a focus on the interpretation of the results.

Funding

This paper was prepared the at Florida Tech with partial funding under Project No. 36: Weather Information Representativeness and Uncertainty Resolution for Low Altitude Operations, the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) Air Transportation Center of Excellence Cooperative Agreement 12-C-GA-FIT-030 for the Partnership to Enhance General Aviation Safety, Accessibility and Sustainability (PEGASAS). The FAA neither endorses nor rejects the findings of this research.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Florida Tech student Cole Niewohner for focusing attention on the ASOS equipment relocation at KMHT as part of a term project for Aviation Meteorology 2.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ASOS |

Automated Surface Observing System |

| FAA |

Federal Aviation Administration |

| ICAO |

International Civil Aviation Organization |

| METAR |

Meteorological Aerodrome Report |

| MRLC |

Multi-Resolution Land Characteristics |

| NASA |

National Aeronautics and Space Administration |

| NLCD |

National Land Cover Database |

| NOAA |

National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration |

| SPECI |

special meteorological report |

| VOR |

Very High Frequency (VHF) Omnidirectional Range |

| WMO |

World Meteorological Organization |

Appendix A

Table A1.

NASA ASRS reports related to mechanical turbulence.

Table A1.

NASA ASRS reports related to mechanical turbulence.

| ASRS Report Number |

Location |

Date |

Relevant report text |

| 1960621 |

Unknown |

12/2022 |

“This airport is known for rogue gusts as it sits on a hill with the south side of the runway having rising terrain, which seems to create gusts at the numbers on [the] Runway XY approach.” “Much of the time AWOS reports variable wind instead of a direction because it is varying anywhere from 20 – 40 degrees.” |

| 1911945 |

Unknown |

06/2022 |

“There are buildings (and the helicopter pad) to the immediate north-east of the runway. Given wind direction, it is likely that the first part of the runway had stable winds, but the later part of the runway had more abnormal gusts and eddies caused by wind at the time flowing over those structures.” |

| 1910295 |

Unknown |

06/2022 |

“The gusty conditions interacting with the large buildings of the city led to downdrafts and mechanical turbulence that kept sucking us down as we tried to climb.” |

| 1887173 |

Unknown |

03/2022 |

“I think it's possible that the wind that we experienced was higher than what was reported; or possibly the direction of the wind, coming through the hangers and other airport buildings, might have introduced wind shear at the worst possible point in our landing.” |

| 1864945 |

Unknown |

12/2021 |

“The east side of the airport is where the control tower, some hangers, and trees are. With the winds being out of the east it makes me wonder if we had a weird gust of wind mixed with some mechanical turbulence.” |

| 1760076 |

Unknown |

08/2020 |

“I wonder if there could be a connection between the CRJ holding short, perpendicular to the numbers and the easterly, variable winds--possibly generating a unique mechanical turbulence which caused the rapid decay in descent so close to the runway” |

| 1509079 |

Unknown |

12/2017 |

“Rather than return to the airport of departure, which was beyond some hills creating orographic turbulence that could have added to the load factor, I elected to return to a nearby airport that had long, wind-aligned runways” |

| 1420057 |

Unknown |

01/2017 |

“Trees, hills, and the open area probably produced gusts and directional changes in the wind.” |

| 1383903 |

Unknown |

08/2016 |

“I believe the combination of the small amount of ice, aileron deflection and mechanical turbulence from buildings on the upwind side of the runway caused the left wing to stall at a higher than normal airspeed, resulting in the uncommanded left roll.” |

| 1363436 |

Alturas, California (AAT) |

06/2016 |

“In the flare, the aircraft dropped suddenly due to mechanical turbulence created from the wind flowing over the hangars/FBO/trees on the NW side of the airport.” |

| 1340662 |

Unknown |

02/2016 |

“During the landing, I encountered a gusting wind and mechanical turbulence from the building and terrain on the west side of runway 14” |

| 1071503 |

Unknown |

03/2013 |

“The crosswind component was 25 KTS and the tailwind component 9 KTS. We chose Runway XX to avoid mechanical turbulence associated with terrain south of the airport.” |

| 1050984 |

Alaska |

11/2012 |

“At this airport moderate or greater mechanical turbulence can be expected below 1,500-2,000 feet when there are strong winds out of the northwest or northeast quadrants” |

| 1045076 |

Melbourne, FL (MLB) |

10/2012 |

“There are buildings (and the helicopter pad) to the immediate north-east of the runway. Given wind direction, it is likely that the first part of the runway had stable winds, but the later part of the runway had more abnormal gusts and eddies caused by wind at the time flowing over those structures.” |

| 1016862 |

Unknown |

06/2012 |

“I thought this must have been due to mechanical turbulence associated with the gusty winds (approximately 150 degrees) coming over the terminal.” |

| 989017 |

Unknown |

01/2012 |

“The wind was gusty and there was some mechanical turbulence from a large hangar across the runway.” |

| 944692 |

Unknown |

04/2011 |

“The reported winds, later verified with airport operations, were 180 degrees at four knots. However, the winds were coming from the side of the airport where buildings are relatively close to the runway.” |

| 919797 |

Unknown |

11/2010 |

“We were high as there was orographic turbulence and we were asked by Tower to turn an early base because there was inbound traffic on long final.” |

| 713739 |

LaGuardia, NY (LGA, East River Exclusion Zone) |

10/2006 |

“4) THE HT AND PLACEMENT OF THE BUILDINGS AND LCL GEOGRAPHY CREATE UNPREDICTABLE LCL WIND AND WX CONDITIONS.” |

| 497557 |

Buffalo, NY (BUF) |

01/2001 |

“RPTR CLAIMS WINDSHEAR EQUIP AT BUF DOES NOT GIVE ACCURATE READINGS BECAUSE IT IS AMONGST SURROUNDING VEGETATION AND BUILDINGS.” |

| 485620 |

Mammoth Lakes, California (MMH) |

09/2000 |

“THE RWY IS SURROUNDED BY EXTREMELY RUGGED AND HIGH TERRAIN AND HAS ASSOCIATED TURB AND GUSTS.” |

| 137899 |

Marquette, MI (MQT) |

02/1990 |

“THE LCL TERRAIN INCLUDES A LARGE ROCK HILL JUST TO THE N OF RWY 08-26 IN MARQUETTE. THIS HILL CREATES MECHANICAL TURBULENCE AROUND IT WHICH MAKES THE WIND VARIABLE ACROSS THE ARPT PROPERTY, AND CREATING SITUATIONS SUCH AS THE "WHITE OUT" WE ENCOUNTERED.” |

Table A2.

Isolated obstructions and/or other impactful siting issues.

Table A2.

Isolated obstructions and/or other impactful siting issues.

| ICAO Airport Code |

Isolated obstructions or siting issues |

| KABQ |

None noted |

| KAOO |

House 90 m northeast of ASOS |

| KAZO |

None noted |

| KBGD |

Hangars 50 m northwest of ASOS |

| KBUF |

Airport structure 75 m north-northeast of ASOS |

| KCKV |

House 160 m south-southeast of ASOS |

| KDFW |

ATC tower 290 m east of ASOS |

| KGEZ |

Farm silos 260 m north-northeast of ASOS |

| KGLS |

VOR 345 m west-southwest of ASOS |

| KHGR |

Airport terminal 115 m south-southwest of ASOS |

| KHSV |

Patch of trees 115 m west of ASOS |

| KIDA |

Glide slope equipment 15 m northeast of ASOS |

| KLXV |

ASOS locate next to large area of trees |

| KMHT |

Buildings 165 m east-northeast of ASOS |

| KONT |

None noted |

| KOVE |

Road with trees 20 m west of ASOS |

| KPAE |

Large airport structure 80 m southeast of ASOS |

| KPKD |

Hangars 25 m northeast of ASOS |

| KSLC |

None noted |

| KTCC |

None noted |

Appendix B

Figure A1.

Average GFmet by direction [2019-2004] for a) KAOO, b) KAZO, c) KBGD, and d) KBUF.

Figure A1.

Average GFmet by direction [2019-2004] for a) KAOO, b) KAZO, c) KBGD, and d) KBUF.

Figure A2.

Average GFmet by direction [2019-2004] for a) KCKV, b) KGEZ, c) KHGR, and d) KHSV.

Figure A2.

Average GFmet by direction [2019-2004] for a) KCKV, b) KGEZ, c) KHGR, and d) KHSV.

Figure A3.

Average GFmet by direction [2019-2004] for a) KIDA, b) KLXV, c) KMHT, and d) KONT.

Figure A3.

Average GFmet by direction [2019-2004] for a) KIDA, b) KLXV, c) KMHT, and d) KONT.

Figure A4.

Average GFmet by direction [2019-2004] for a) KOVE, b) KPKD, c) KSLC, and d) KTCC.

Figure A4.

Average GFmet by direction [2019-2004] for a) KOVE, b) KPKD, c) KSLC, and d) KTCC.

Appendix C

Figure A5.

Average GFavn by direction [2019-2004] for a) KAOO, b) KAZO, c) KBGD, and d) KBUF.

Figure A5.

Average GFavn by direction [2019-2004] for a) KAOO, b) KAZO, c) KBGD, and d) KBUF.

Figure A6.

Average GFavn by direction [2019-2004] for a) KCKV, b) KGEZ, c) KHGR, and d) KHSV.

Figure A6.

Average GFavn by direction [2019-2004] for a) KCKV, b) KGEZ, c) KHGR, and d) KHSV.

Figure A7.

Average GFavn by direction [2019-2004] for a) KIDA, b) KLXV, c) KMHT, and d) KONT.

Figure A7.

Average GFavn by direction [2019-2004] for a) KIDA, b) KLXV, c) KMHT, and d) KONT.

Figure A8.

Average GFavn by direction [2019-2004] for a) KOVE, b) KPKD, c) KSLC, and d) KTCC.

Figure A8.

Average GFavn by direction [2019-2004] for a) KOVE, b) KPKD, c) KSLC, and d) KTCC.

Appendix D

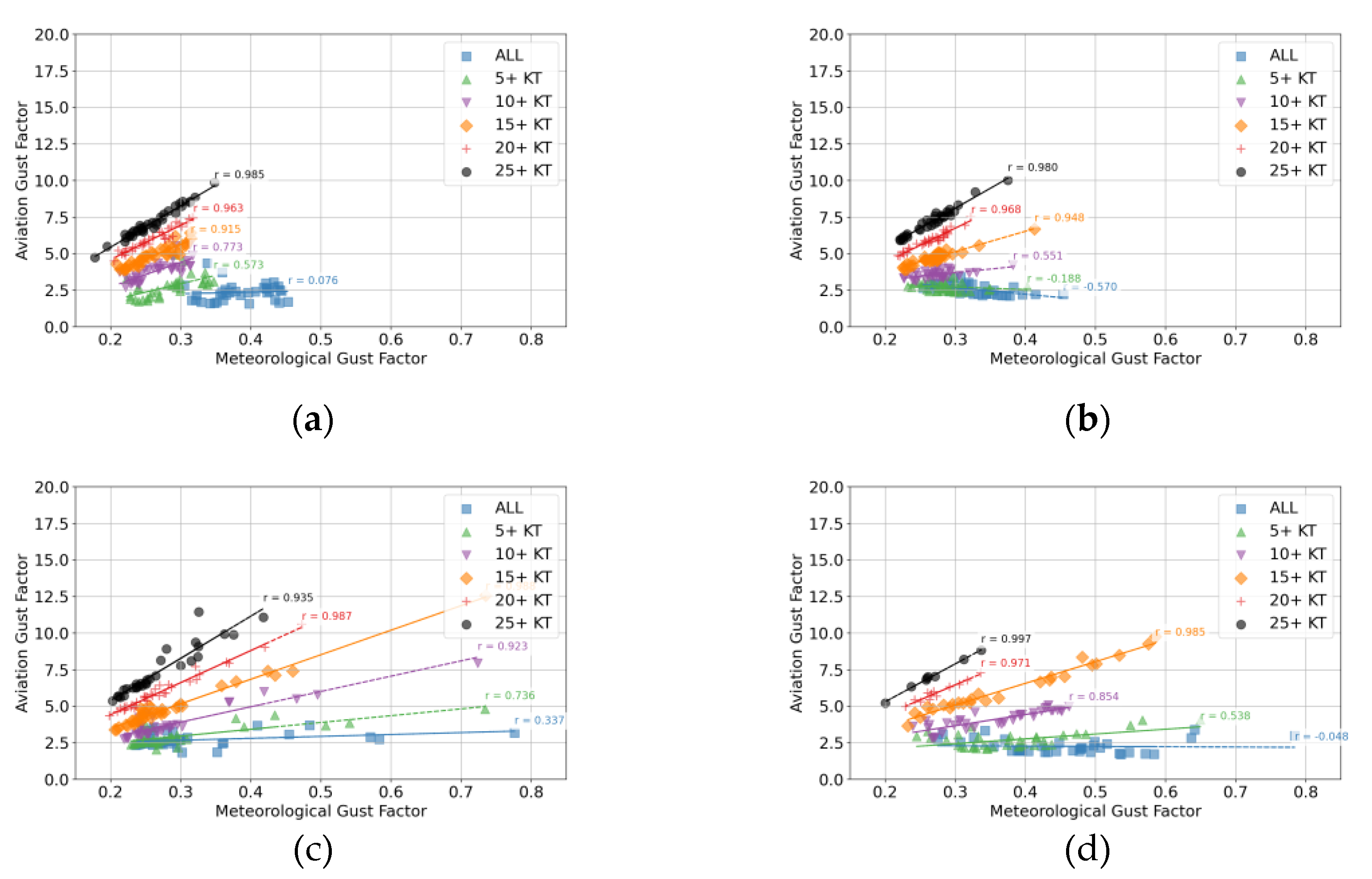

Figure A9.

Average GFavn vs. GFmet by direction [2019-2004] for a) KAOO, b) KAZO, c) KBGD, and d) KBUF filtered by gust values: no filtering (blue box), 5+ kt (green triangle), 10+ kt (purple downward triangle), 20+ kt (red plus), and 25+ kt (black circle).

Figure A9.

Average GFavn vs. GFmet by direction [2019-2004] for a) KAOO, b) KAZO, c) KBGD, and d) KBUF filtered by gust values: no filtering (blue box), 5+ kt (green triangle), 10+ kt (purple downward triangle), 20+ kt (red plus), and 25+ kt (black circle).

Figure A10.

Average GFavn vs. GFmet by direction [2019-2004] for a) KCKV, b) KGEZ, c) KHGR, and d) KHSV filtered by gust values: no filtering (blue box), 5+ kt (green triangle), 10+ kt (purple downward triangle), 20+ kt (red plus), and 25+ kt (black circle).

Figure A10.

Average GFavn vs. GFmet by direction [2019-2004] for a) KCKV, b) KGEZ, c) KHGR, and d) KHSV filtered by gust values: no filtering (blue box), 5+ kt (green triangle), 10+ kt (purple downward triangle), 20+ kt (red plus), and 25+ kt (black circle).

Figure A11.

Average GFavn vs. GFmet by direction [2019-2004] for a) KIDA, b) KLXV, c) KMHT, and d) KONT filtered by gust values: no filtering (blue box), 5+ kt (green triangle), 10+ kt (purple downward triangle), 20+ kt (red plus), and 25+ kt (black circle).

Figure A11.

Average GFavn vs. GFmet by direction [2019-2004] for a) KIDA, b) KLXV, c) KMHT, and d) KONT filtered by gust values: no filtering (blue box), 5+ kt (green triangle), 10+ kt (purple downward triangle), 20+ kt (red plus), and 25+ kt (black circle).

Figure A12.

Average GFavn vs. GFmet by direction [2019-2004] for a) KOVE, b) KPKD, c) KSLC, and d) KTCC filtered by gust values: no filtering (blue box), 5+ kt (green triangle), 10+ kt (purple downward triangle), 20+ kt (red plus), and 25+ kt (black circle).

Figure A12.

Average GFavn vs. GFmet by direction [2019-2004] for a) KOVE, b) KPKD, c) KSLC, and d) KTCC filtered by gust values: no filtering (blue box), 5+ kt (green triangle), 10+ kt (purple downward triangle), 20+ kt (red plus), and 25+ kt (black circle).

References

- Aguiar, M.; Stolzer, A.; Boyd, D. D. Rates and causes of accidents for general aviation aircraft operating in a mountainous and high elevation terrain environment. Accident Analysis & Prevention 2017, 107, 195–201. [Google Scholar]

- Federal Aviation Administration (2008). On Landings, Part II. FAA-P-8740-49.

- Federal Aviation Administration. (2022). Airplane Flying Handbook: FAA-H-8083-3C (2025). Simon and Schuster.

- Rooney, H. (2023). Utilizing Flight Data Monitoring at a Part 141 Flight School to Determine Predictors for Unstabilized Approaches and Go-arounds.

- Federal Aviation Administration; US Department of Transportation. Turbulence. In Aviation Weather Handbook; Academics, A.S., Ed.; Aviation Supplies & Academics, Inc.: Newcastle, WA, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- National Transportation Safety Board Aviation Database (2025), https://www.ntsb.gov/Pages/AviationQueryv2.aspx, Last accessed. 24 May.

- Aviation Safety Reporting System: ASRS Database Online. (2025). https://asrs.arc.nasa.gov/search/database.html. Last accessed. 26 May.

- Fang, P.; Huo, T.; Pan, J.; Luan, G. Variations in gust factor with wind direction and height based on the measurements from a coastal tower during three landfalling typhoons. Tropical Cyclone Research and Review 2024, 13(3), 187–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paulsen, B. M.; Schroeder, J. L. An examination of tropical and extratropical gust factors and the associated wind speed histograms. Journal of Applied Meteorology 2005, 44(2), 270–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, A. R.; Kahl, J. D. Gust factors: Meteorologically stratified climatology, data artifacts, and utility in forecasting peak gusts. Journal of Applied Meteorology and Climatology 2017, 56(12), 3151–3166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coen, J. Some requirements for simulating wildland fire behavior using insight from coupled weather—wildland fire models. Fire 2018, 1(1), 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Meteorological Organization (WMO). Guide to Meteorological Instruments and Methods of Observation, 2014 ed.; Updated in 2017; WMO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017; p. 1165. [Google Scholar]

- NOAA, 1994: Federal standards for siting meteorological sensors at airports. Office of the Federal Coordinator for Meteorological Observations and Supporting Research, FCM-S4-1994. [Available online at http://www.ofcm.gov/siting/text/a-cover.htm].

- Fovell, R. G.; Gallagher, A. Winds and gusts during the Thomas fire. Fire 2018, 1(03), 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NOAA, 1998: Automated Surface Observing System (ASOS) user’s guide. NOAA Tech. Doc.; 72 pp.; https://www.weather.gov/media/asos/aum-toc.pdf.

- Yu, B.; Gan Chowdhury, A. Gust factors and turbulence intensities for the tropical cyclone environment. Journal of Applied Meteorology and Climatology 2009, 48(3), 534–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seastrand, S. R. (2018). The Seasonal Predictability of Extreme Wind Events in the Southwest United States (Doctoral dissertation, The University of Arizona).

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).