1. Introduction

Pantoea stewartii subsp.

stewartii (Pss) is a Gram-negative bacterium indigenous of the Americas. The main host for this bacterium is Zea mays (maize), especially sweet corn, but dent, flint, flour, and popcorn cultivars can also be infected. Pss causes a maize disease known as Stewart’s wilt, responsible for serious maize crop losses throughout the world [

1]. Pss has been introduced to other parts of the world through maize seeds: the bacterium has now spread to Africa, North, Central, and South America, Asia, and Ukraine. In the EU, it has been reported in Italy, where it has a restricted distribution and resulted today to be eradicated (

Pantoea stewartii subsp.

stewartii. The bacterium is regulated under Commission Implementing Regulation (EU) 2019/2072 of 28 November 2019 (Annex II) as a harmful organism, prohibiting its introduction and spread in the EU territory on seeds of Z. mays. Other potential host plants include various species of the family Poaceae, such as weeds, rice (

Oryza sativa), oat (

Avena sativa), and common wheat (

Triticum aestivum), as well as jackfruit (

Artocarpus heterophyllus), the ornamental

Dracaena sanderiana, and the palm

Bactris gasipaes [

2].

In the USA, Pss spread largely relies on insect vectors, primarily the corn flea beetle

Chaetocnema pulicaria Melsheimer (Coleoptera, Chrysomelidae), which is currently not present in the EU. In the north-central and eastern regions of the United States, the economic impact of this disease is minimal due to the presence of resistant cultivars and the use of systemic seed-applied insecticides for pest control. It’s worth noting that maize susceptible varieties are severely affected and may be destroyed at the seedling stage [

3].

To prevent the diffusion of Stewart’s wilt, the diagnosis of Pss is an effort supported by EU countries as highlighted by the project financed by EU (Valitest, grant agreement No. 773,139), the activity European EURL-BAC project and Italian project Proteggo 1.4 financed by the Italian Ministry of Agriculture, Food Sovereignty and Forests (MASAF). Various detection methods have been described in literature, utilizing isolation, serology, or molecular biology techniques. Additionally, a diagnostic procedure for Pss has been published by PM 7/60 (2) EPPO [

4].

In the frame of EUROPHYT (European Union Notification System for Plant Health Interceptions), the Italian Plant Protection Organization carried out the surveillance of the territory for possible vector associated to the bacterial pathogen in area where symptoms of Stewart’s wilt were found [

5,

6]. In Italy, within the framework of Pss studies, during entomological surveys in maize fields, some insects were caught feeding on plants and some of them resulted positive to PCR screening: one crysomelid beetle belonged to the genus

Phyllotreta (this genus is similar to the main vector in the country of origin

C. pulicaria), as well as some specimens of the brown marmorated stink bug

Halyomorpha halys (Stål) (Heteroptera, Pentatomidae).

Following the detection of Pss in

Halyomorpha halys (H. halys) in the frame of PROTEGGO 1.3 project financed by the MASAF, a laboratory assay was conducted in 2021 to assess the stink bug’s potential as a vector of the bacterium. Originally from East Asia,

H. halys has become an invasive pest in many parts of the world, including North America, Europe, the Caucasus region, Western Central Asia, and Chile. This polyphagous species feeds on a wide variety of crops, often causing severe damage even at early developmental stages. Injuries caused by

H. halys result in rot, deformities, and unmarketable produce, leading to considerable economic losses [

7]. In addition to its direct damage,

H. halys is also known to act as a vector of plant-associated microorganisms. For instance, it has been shown to transmit

Eremotecium coryli Kurtzman (Saccharomycetaceae) to fruits and vegetables [

8,

9].

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Bacterial Strain

The lyophilized strain of Pss CREA-DC 1775[

6] was revived and cultured in NAG. The bacteria strain has been cultured on nutrient agar 0.25% d-glucose (NAG) [

4] for 48 h at 27–28˚C. Bacterial suspensions have been prepared in phosphate buffer (PB 50 mM, pH = 7). The concentrations are spectrophotometrically (DS-11 Fx+, Spectrophotometer-Fluorometer Denovix Inc., Wilmington, DE, United States) measured at OD660 = 0.05 corresponding to approximately 10

8 colony forming units (CFU)/mL [

6].

2.2. Halyomorpha Halys

Adult specimens of Haliomorpha halys were collected in the field during the 2021 maize growing season and subsequently maintained under controlled laboratory rearing conditions (26°C, 16:8 L:D, 65%RH). Insects were reared in mesh cages and provided with a mixed diet consisting of fruits, vegetables and seeds to ensure adequate nutrition and physiological maintenance prior to experimentation. Before the start of the tests, adults, both females and males, were starved for 5 days with only water supply. Following starvation, the insects were forced to feed on maize plants under controlled conditions. The experimental procedures were conducted according to a stepwise protocol, detailed in the following sections.

2.3. Inoculation of Plant

The artificially inoculation of sweet maize seedlings of 8–14-day-old (1–2 leaf stages) was performed with Pss strain IPV-BO 2766. The maize plants of 14-day-old (1–2 leaf stage), were stem inoculated following the European Plant and Protection Organization [

4] and grown in a quarantine glasshouse at 22–28°C. Negative control plants have been inoculated with sterile distilled water. The disease symptoms appeared after 7 days. Plants have been kept for observation for 30 days. To verify the transmission of Pss throught

H. halys, the plants adopted in step III (see

Section 2.4) were kept for observation for 30 days. After that period the leaves tissues were used to extract the DNA to perform real-time PCR [

10] and to isolate the pathogen potentially transferred by the insects in step III.

2.4. Transmission Experiments

An approximately 100 female and 50 male Halyomorpha halys adults were used in this experiment. Adult specimens were reared in the Quarantine greenhouse in insect cages (BugDorm BD4E4545). The experimental design included three plant treatments: In this experiment we employed: i) healthy (non-inoculated) maize plants; ii) maize plants artificially inoculated with Pss; iii) healthy maize plants inoculated with distilled water as negative control. Each plant—whether inoculated or not—was placed in a rearing cage together with five adult Halyomorpha halys specimens.; in total thirty maize plants were set with H. halys, unless otherwise specified. The experiment was divided in three steps:

step I: all the insects were fed ten days in rearing cages containing healthy maize plants of 4-5 leaf supplemented with apple slices as an additional food source. After 1 week of feeding, 6 insects randomly selected (2 males and 4 females), were collected for molecular analysis. DNA was extracted separately from body and head parts to verify the absence of Pss.

step II: in this phase, the remaining insects were divided into two treatment groups and exposed for one week to either maize plants artificially inoculated with Pantoea stewartii subsp. stewartii (Pss) or to control plants treated with sterile distilled water. A total of 5 males and 25 females were placed in cages with healthy maize plants as negative control, while 40 males and 80 females were housed in cages with Pss inoculated maize plants. After one week of feeding, 26 males and 34 females randomly selected from insects exposed to inoculated maize plants. These individuals were collected and subjected to molecular analysis to assess the potential acquisition of Pss;

step III: the remaining 58 insects previously fed on Pss-inoculated plants, along with 30 insects previously fed on healthy control plants were individually transferred to new insect-rearing cages. Each cage contained one adult insect and one healthy maize plant at the 4–5 leaf development stage. The insects were allowed to feed on the healthy plants for 30 days. At the end of this period, all insects were collected and analyzed to assess the presence of Pss.

The plants used in the step III to feed the insects were observed for the possible development of symptoms of bacterial wilt disease over the next 21 days. At the end of the observation period, the plants were harvested and examined for the presence of Pss using real-time PCR according to Tambong et al. [

10] and an isolation procedure as reported in letterature [

4].

2.5. DNA Extraction

Plant DNA has been extracted from leaves tissue with the DNeasy Plant Mini kit (Qiagen, Venlo, the Netherlands). The DNA concentration is evaluated by Qubit (dsDNA HS Assay kit, Invitrogen, Waltham, MA, United States) and the DNA was stored ≤ − 15◦C until analysis. The bacterial DNA was extracted with the Gentra Puregene Yeast/ Bact Kit (Qiagen, Venlo, the Netherlands).

Insects were stored in 95% ethanol until DNA extraction. Each specimen was dissected with scalpel and forceps in its storage solution to process head and body separately for each sample. Both anatomical parts were ground using seven Ø 2.0 mm glass beads in 2.0 ml tube and Precellys 24 (Precellys) bead beater. DNA was extracted from the homogenized tissues using the DNeasy Blood & Tissue QIAcube Kit (QIAGEN) according to the manufacturer's recommendations. The final elution step was performed in 50 µl of AE buffer provided in the kit.

2.6. Real-Time PCR Method for Plant Tissue and Insect

To confirm the presence of Pss in plant tissue the diagnosis of Pss was performed according to Tambong et al. [

10] and Pal et al. [

11] tests. The Pss re-isolation from symptomatic tissues has been performed. Pss-like colonies were identified by real-time PCR TaqMan and real-time PCR SYBR green protocols [

10,

11]. To evaluate the presence of Pss in insect tissue the real-time PCR of Tambong et al. [

10] has been performed according to the EPPO protocol [

4] employing the Sso Advanced Universal Probes Supermix (Biorad). All the real-time PCR reactions have been carried out using CFX96 Real-Time System, BioRad. For all the real-time PCR, the standard deviation of the cycle threshold (Ct) values is calculated from the arithmetic mean of every sample that has been amplified in two technical replicates.

3. Results

3.1. Transmission Experiments

In step I, from the 100 females and 50 males tested, two males and four females of the insects were used for Pss analysis. Specifically, the head and body were separated, and DNA was extracted independently from each tissue, as described in materials and methods. The DNA was analyzed by real-time PCR [

10] and no signal relative to the presence of Pss was observed during the amplification (data not shown).

The samples used as negative control at step II and III (no opportunity to fed on Pss inoculated plants), consists of 5 males and 25 females. At the end of step III, all the insects were analyzed by DNA extraction as described above. The analysis through the real-time PCR did not show any amplification signal corresponding to the possible presence of Pss.

Simultaneously in phase II, from the 40 males and 80 females that were fed in cages containing maize plants inoculated with Pss and left to feed for 1 week, 34 females and 26 males, respectively, were used for DNA extraction from body and head tissue separately, and analyzed by real-time PCR [

10] to detect the presence of Pss.

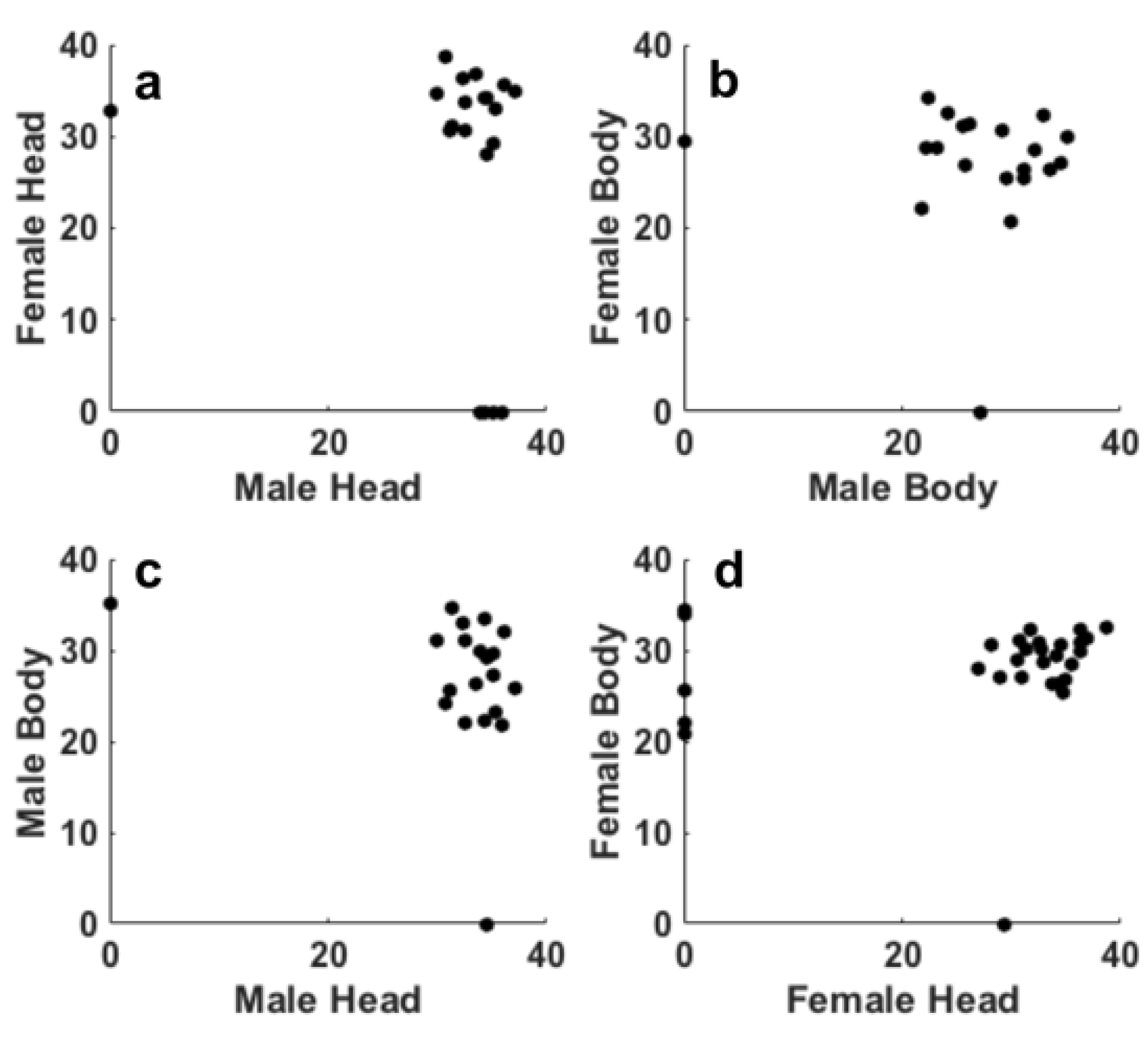

Figure 1 shows the histogramfit (histfit) plot of the data relatives to the threshold cycles (Ct) obtained after the analysis by real-time PCR executed on the extracted DNA from insects after step II. The histfit plots a histogram of values in data using the number of bins equal to the square root of the number of elements in data and fits a normal density function.

Figure 1 suggests that both male and female insects exhibit the presence of Pss, as indicated by the Ct values ranging from 20 to 35. The range of the Ct values (30≤Ct≤35) extracted from the head of males is narrower than that relative to females (25≤Ct≤40) (

Figure 1a,c). On the other hand, the bodies of females (

Figure 1b) and males (

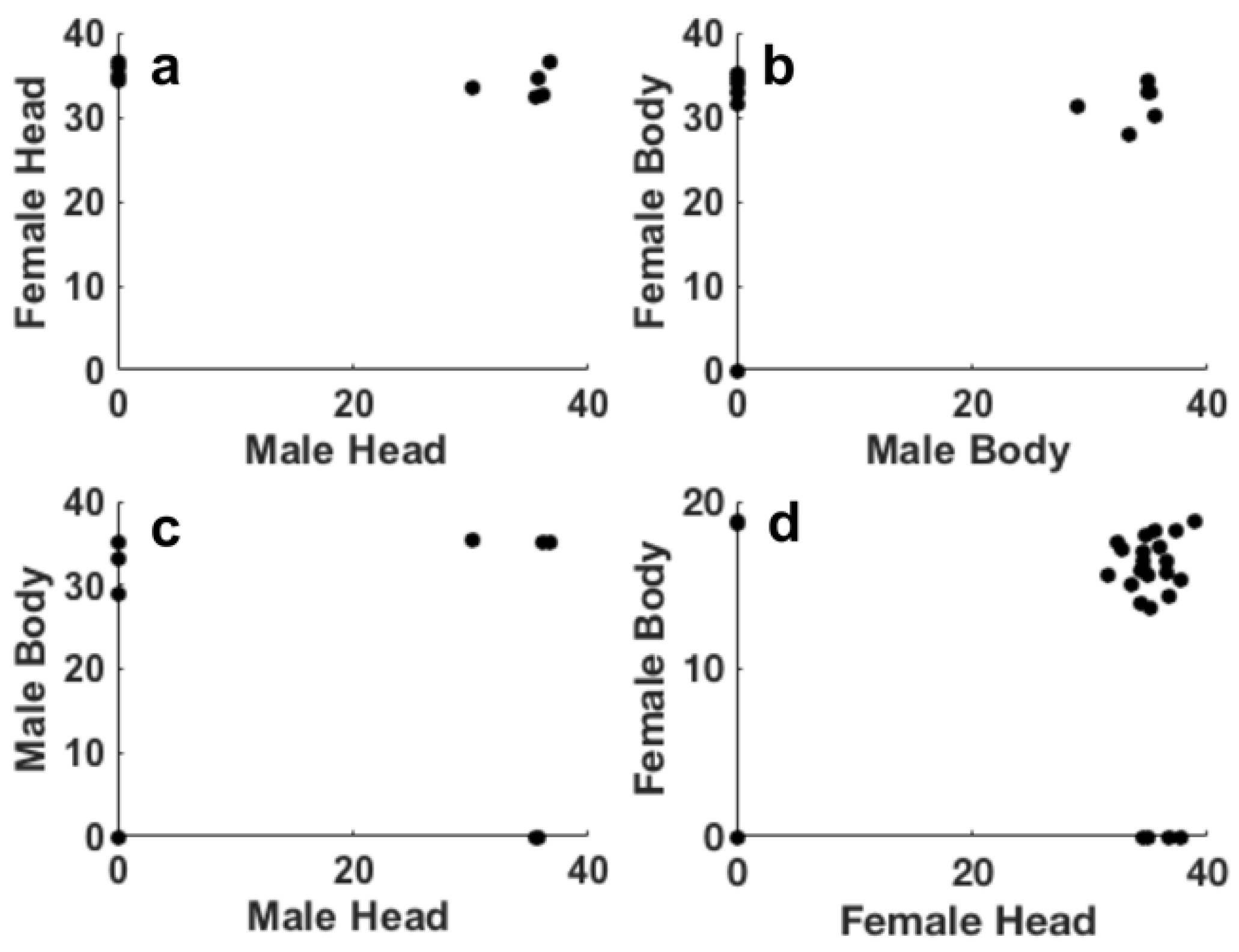

Figure 1d), respectively, showed similar Ct values for the presence of Pss (20≤Ct≤35). The results indicate that after step II, the females were positive to Pss in the 86% and 94% of heads and bodies, respectively. Regarding the males 87% of both head and body were positive to Pss. The scatter correlation between the Ct values of heads male/female and bodies male/female (

Figure 2a,b) and between head/body males and females (

Figure 2c,d) shows the result of the Persons correlation. All the p values obtained for all the correlations showed values higher the 0.05, thus suggesting that the correlation is not statistically significant. This result suggests that the bacterium is distributed randomly in the bodies and heads.

For the step III, 46 females and 14 males were transferred in a cage containing healthy maize plants and left to feed for 30 days. At the end of step III, all the insects were used for DNA analysis aimed to detect the possible presence of Pss.

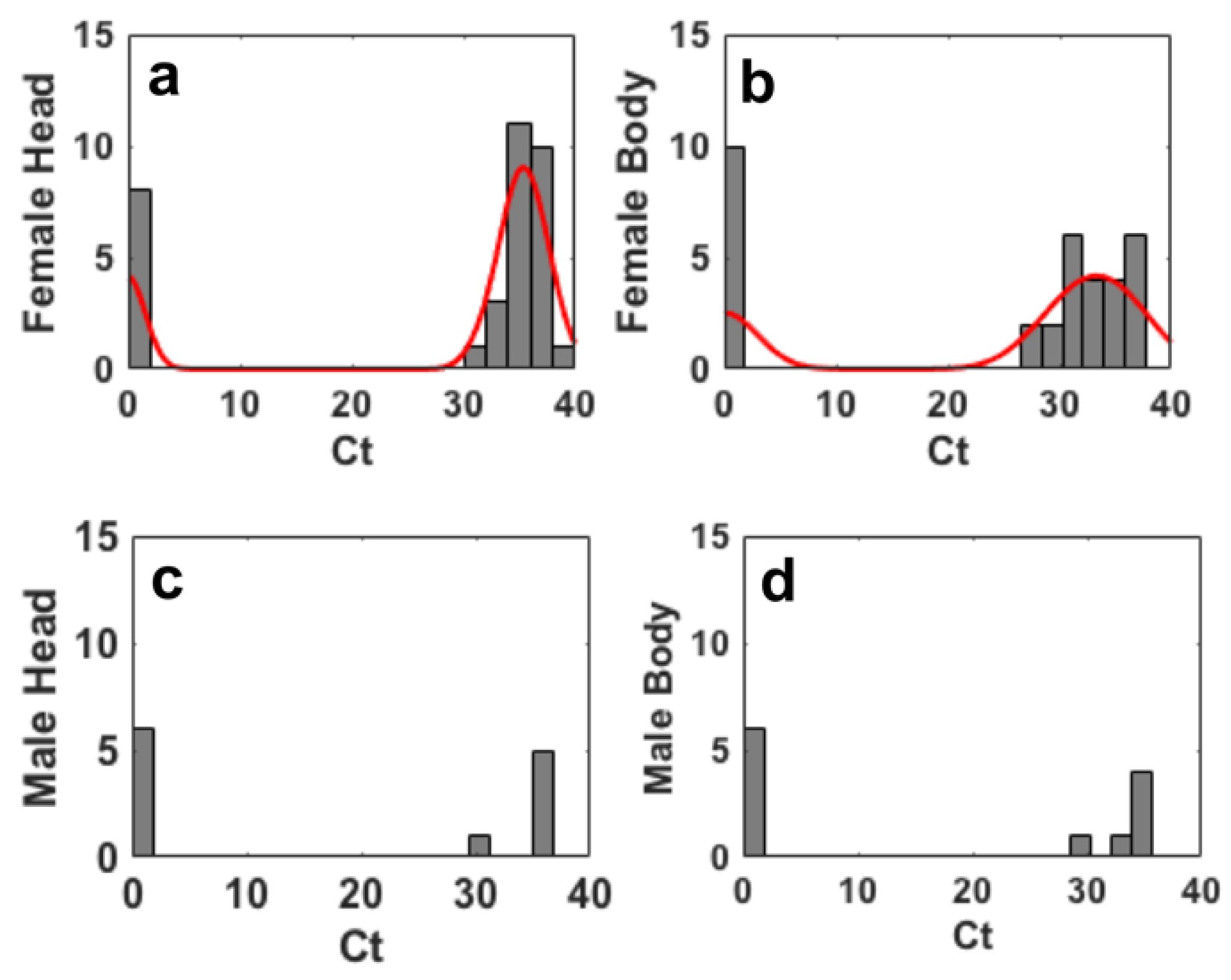

Figure 3 shows the data relative to the threshold cycles (Ct) obtained after the analysis by real-time PCR executed on the extracted DNA from insect in phase III.

Figure 3a,b show the histfit of the Ct values for female heads and bodies.

Figure 3c,d report the histogram of the Ct values for male heads and bodies.

The results in

Figure 3 indicate that after step III the 80.4% of females (pooled data for heads and bodies) were positive to Pss. Regarding the males, they were positive to Pss 57% and 43% of heads and bodies, respectively.

Figure 3 suggests that both female and male insects exhibit Ct values ranging from 30 to 40, although males showed an higher number of insects negative to Pss. Ct values relative to the presence of Pss in heads and bodies of both females (

Figure 3a,b) and males (

Figure 3c,d) displayed similar distribution of these values. The scatter correlation between the Ct values of heads male/female and bodies male/female (

Figure 4a,b) and between head/body males and females (

Figure 4c,d) shows the result of the Persons correlation. All the p-values obtained for all the correlations showed values higher the 0.05, thus suggesting that the correlation is not statistically significant. As already observed in step II, this result confirms that the bacterium is distributed randomly in the bodies and heads of the insect.

3.2. Plants

All the plants that were artificially inoculated were tested positive using molecular methods and pathogen isolations. All the plants of step III were tested negative using molecular methods and isolation procedures.

4. Discussion

Stewart’s wilt on maize, caused by the gram-negative bacterium

Pantoea stewartii subsp.

stewartii (Pss), has been reported as endemic in the mid-Atlantic USA states, the Ohio River Valley and the southern portion of the Corn Belt [

12]. Stewart’s wilt is reported to have declined in prevalence in the USA due to the use of resistant varieties and the widespread use of neonicotinoid seed treatment. Neonicotinoids reduced the population abundance of the vector of Pss, the corn flea beetle

Chaetocnema pulicaria, in which the bacterium overwinters [

13,

14]. In the Americas,

C. pulicaria is the main vector and the main overwintering site of Pss. However, Stewart’s wilt is also transmitted by other chrysomelid beetle, the toothed flea beetle

Chaetocnema denticulata Illiger and by the spotted cucumber beetle

Diabrotica undecimpunctata howardi Barber [

5]and by the larvae of the seed corn maggot

Delia platura Meigen (Diptera, Anthomyidae), the wheat wireworm

Agriotes mancus Say (Coleoptera, Elateridae) and by May beetles

Phyllophaga spp. (Coleoptera, Scarabaeidae). The transmission of bacteria among plants dependent by insect vectors is transmitted during the insect feeding stage. Each contaminated insect vector can infect several healthy plants after feeding on an infected plant [

2]. Insect screening in some of the Italian maize fields symptomatic to Stewart’s wilt were found positive to Pss in on case of

Phyllotreta sp. and a few specimens of

Halyomorpha halys. In this paper. it’s shown for the first time, the potential role of

H. halys in vectoring Pss, due to positive detection of the bacteria in insects parts, although with different percentages, both in the heads and in the rest the bodies of males and females; the results suggest that the insects acquired the bacterium from the plants (artificially inoculated under laboratory conditions). However, analyses failed to detect the successful transmission to healthy plants the insects analyzed in phase III tested positive with molecular tests (

Figure 3), the plants analyzed were negative. These results suggest that the bacterium is acquired by the insect but not transmitted to the plants. This may indicate a mechanical contamination rather than a true biological transmission, or a possible inability of

H. halys to effectively inoculate the bacterium into plant tissues during feeding.

Further studies are needed to clarify the exact mechanisms behind this acquisition and to determine whether certain environmental or physiological conditions could enable transmission.

Considering the wide spread of

H. halys also in corn fields in Italy and the growing issues of Pss on maize, its epidemiological role remains an open question and remain still to be furtherly investigated. Similar outputs were obtained investigating

H. halys in transmission ability of the yeast

E. coryli on hazelnuts, tests conducted failed to prove that successful transmission, notwithstanding that adults resulted positive to acquire the yeast in their mouthparts [

15].

Author Contributions

For research articles with several authors, a short paragraph specifying their individual contributions must be provided. The following statements should be used “Conceptualization, V.S.; methodology, F.C, F.M., L.M., G.S., P.R.; software, F.C.; formal analysis, F.C., V.S.; investigation, F.C., V.S., A.S., L.M., G.S., P.R.; resources, P.R.; data curation, F.C., V.S.; writing—original draft preparation, F.C., V.S.; writing—review and editing, F.C., V.S.,A.S., L.M., G.S., P.R; funding acquisition, P.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by MASAF-DISR5 Proteggo 1.4 – Accordo di collaborazione Finalizzato alla realizzazione delle attività di cui ai punti 5 e 8 del “Piano delle attività strategiche” di cui all’allegato I del decreto ministeriale 4 gennaio 2022.

Data Availability Statement

The authors declare that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the paper. Should any raw data files be needed in another format, they are available upon reasonable request. Source data are provided for this paper at the CREA DC database.

Acknowledgments

The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| Pss |

Pantoea stewartii subsp. stewartii

|

| H. halys |

Halyomorpha halys |

| CFU |

Colony forming units |

| MASAF |

Italian ministry of agriculture, food sovereignty and forests |

| NAG |

Nutrient agar d-glucose |

References

- Roper, M.C. Pantoea stewartii subsp. stewartii: Lessons Learned from a Xylem-Dwelling Pathogen of Sweet Corn. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2011, 12, 628–637. [CrossRef]

- Jeger, M.; Bragard, C.; Candresse, T.; Chatzivassiliou, E.; Dehnen-Schmutz, K.; Gilioli, G.; Grégoire, J.C.; Jaques Miret, J.A.; MacLeod, A.; Navajas Navarro, M.; et al. Pest Categorisation of Pantoea stewartii subsp. stewartii. EFSA J. 2018, 16. [CrossRef]

- Coplin, D.L.; Majerczak, D.R.; Zhang, Y.; Kim, W.S.; Jock, S.; Geider, K. Identification of Pantoea stewartii subsp. stewartii by PCR and Strain Differentiation by PFGE. Plant Dis. 2002, 86, 304–311. [CrossRef]

- Europe, O. PM 7/60 (2) Pantoea stewartii subsp. stewartii. EPPO Bull. 2016, 46, 226–236. [CrossRef]

- Bragard, C.; Dehnen-Schmutz, K.; Di Serio, F.; Gonthier, P.; Jacques, M.A.; Jaques Miret, J.A.; Justesen, A.F.; MacLeod, A.; Magnusson, C.S.; Milonas, P.; et al. Risk Assessment of the Entry of Pantoea stewartii subsp. stewartii on Maize Seed Imported by the EU from the USA. EFSA J. 2019, 17. [CrossRef]

- Scala, V.; Faino, L.; Costantini, F.; Crosara, V.; Albanese, A.; Pucci, N.; Reverberi, M.; Loreti, S. Analysis of Italian Isolates of Pantoea stewartii subsp. stewartii and Development of a Real-Time PCR-Based Diagnostic Method. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14. [CrossRef]

- Leskey, T.C.; Nielsen, A.L. Impact of the Invasive Brown Marmorated Stink Bug in North America and Europe: History, Biology, Ecology, and Management. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 2018, 63, 599–618. [CrossRef]

- Transmission of the Yeast Eremothecium coryli to Fruits and Vegetables by the Brown Marmorated Stink Bug. https://extension.umd.edu/resource/transmission-yeast-eremothecium-coryli-fruits-and-vegetables-brown-marmorated-stink-bug/.

- Brust, G. Brown Marmorated Stink Bug Transmission of Yeast in Fruit and Vegetables. In Proceedings of the 2011 ESA Annual Meetings, Reno, NV, USA, 13-16 November 2011.

- Tambong, J.T.; Mwange, K.N.; Bergeron, M.; Ding, T.; Mandy, F.; Reid, L.M.; Zhu, X. Rapid Detection and Identification of the Bacterium Pantoea stewartii in Maize by TaqMan® Real-Time PCR Assay Targeting the CpsD Gene. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2008, 104, 1525–1537. [CrossRef]

- Pal, N.; Block, C.C.; Gardner, C.A.C. A Real-Time PCR Differentiating Pantoea stewartii subsp. stewartii from P. stewartii subsp. indologenes in Corn Seed. Plant Dis. 2019, 103, 1474–1486. [CrossRef]

- Pataky, J.; Ikin, R. Pest Risk Analysis: The Risk of Introducing Erwinia stewartii in Maize Seed. Int. Seed Fed. Nyon, Switz. 2003, 79.

- Chaky, J.L., Dolezal, W.E., Ruhl, G. E., Jesse, L., A trend study of the confirmed incidence of Stewart’s wilt of corn, Pantoea stewartii subsp. stewartii, in the U.S.A. (2001–2012), In Proceedings of the APS North Central Division meeting in Manhattan, Kansas, USA, 12–14 June 2013.

- Bradley, C.A.; Mehl, K.; Pfeufer, E. Stewart ’ s Wilt of Corn. Plant Pathol. 2017, 4–6.

- Haegi, A., Sabbatini Peverieri, G., De Gregorio, T., Maspero M., Castello, G., Petrucci, M., Marianelli L., Luongo, L., Roversi, P.F., Vitale, S., Rapid detection of Eremothecium coryli from kernel hazelnut and Halyomorpha halys, In Proceedings of the XXVII Congress of the Italian Phytopathological Society (SIPaV), Palermo, Italy, 21-23 September 2022.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).