Submitted:

12 June 2025

Posted:

13 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Framework

- Pervasiveness: GPT should propagate to many sectors.

- Improvement: GPT should reduce costs for its adopters.

- Innovation spawning: disruptive technologies generating new products and processes having problem-driven radical innovations (cf. also, Bresnahan and Trajtenberg, 1995; cf., Coccia, 2017, 2017a, 2017b; Coccia, 2020, 2020a). GPTs often have a long-run period between their initial research in science and eventual introduction into markets with societal impact (Lipsey et al., 1998, 2005; Rosegger (1980). GPTs are instrumental in supporting new architectures of technological trajectories for various families of products/processes, influencing various sectors in economic systems (Bresnahan and Trajtenberg, 1995, p.8; Hall and Rosenberg, 2010). Coccia (2005, pp.123–124) maintains that these revolutionary innovations have the potential to affect almost every branch of the economy generating different technological trajectories. In summary, quantum technologies, like General-Purpose Technologies (GPTs), are complex technologies that drive different technological trajectories, fostering product and process innovations across various sectors, contributing to corporate, industrial, economic, and social change (Coccia, 2017; 2024).

3. Research Design and Models

3.1. Sources

3.2. Search string to gather data

| Keywords | |

| Quantum Optics | 2101 |

| Quantum Computers | 916 |

| Quantum Electronics | 755 |

| Quantum Computing | 572 |

| Quantum Communication | 547 |

| Quantum Cryptography | 498 |

| Semiconductor Quantum Dots | 360 |

| Quantum Emitters | 152 |

- -

- query : (TITLE-ABS-KEY(“quantum optics”))

- -

- query : (TITLE-ABS-KEY(“computers”))

- -

- query : (TITLE-ABS-KEY(“electronics”))

- -

- query : (TITLE-ABS-KEY(“computing”))

- -

- query : (TITLE-ABS-KEY(“communications”))

- -

- query : (TITLE-ABS-KEY(“cryptography “))

- -

- query : (TITLE-ABS-KEY(“semiconductor Quantum Dots”))

- -

- query : (TITLE-ABS-KEY(“emitters”))

3.3. Measures and samples

| Technologies | Publications | Patents |

| Quantum Technologies | 6480 | 8713 |

| Quantum Optics | 66977 | 1288 |

| Quantum Computers | 34311 | 27814 |

| Quantum Electronics | 38764 | 14013 |

| Quantum Computing | 23117 | 25386 |

| Quantum Communication | 12759 | 4923 |

| Quantum Cryptography | 18563 | 5219 |

| Semiconductor Quantum Dots | 98256 | 7354 |

| Quantum Emitters | 3113 | 511 |

3.4. Specification of models and data analysis procedure

- o Model of temporal aspects in quantum technologies

- o Model for technological evolution in quantum technologies

3.5. Assumptions and model specification

- , whether technology Y evolves at a lower relative rate of change than X; the whole system has a slowing down evolution over the course of time.

- has a unit value: , then Y and X have proportional change during their evolution. In short, when B=1, the whole system here has a proportional evolution of its parts (growth).

- , whether Y evolves at a greater relative rate of change than X; this pattern denotes disproportionate advances. The whole system of technology Y has an accelerated evolution over the course of time.

4. Results from Statistical Analyses

| Dependent variable: scientific products concerning fields in quantum research | ||||

| Research fields | Coefficient b1 | Constant a | F | R2 |

| Quantum communications, Log yi,t | .137*** | −269.81*** | 215.2*** | .90 |

| Quantum Computers, Log yi,t | .144*** | −281.72*** | 183.52*** | .88 |

| Quantum Computing, Log yi,t | .147*** | −288.72*** | 81.77*** | .76 |

| Quantum Cryptography, Log yi,t | .129*** | −253.35*** | 191.34*** | .88 |

| Quantum Electronics, Log yi,t | −.025 | 56.78 | .72 | .03 |

| Quantum Emitters, Log yi,t | .258*** | −515.54*** | 339.52*** | .93 |

| Quantum Optics, Log yi,t | .10*** | −190.23*** | 184.78*** | .88 |

| Semiconductor Quantum Dots, Log yi,t | .091*** | −174.48*** | 48.99*** | .66 |

- ▪ Quantum emitters, estimated b=0.26

- ▪ Quantum computing, estimated b=0.15

- ▪ Quantum computers, estimated b=0.144

- ▪ Quantum communication, estimated b=0.137

- ▪ Quantum cryptography, estimated b=0.13

- o Quantum computing, estimated b=0.26

- o Quantum computers, estimated b=0.25

- o Quantum communication, estimated b=0.20

- o Quantum emitters, estimated b=0.16

- o Quantum cryptography, estimated b=0.15

| Dependent variable: patents in fields of quantum science | ||||

| Research fields | Coefficient b1 | Constant a | F | R2 |

| Quantum communications, Log yi,t | .202*** | −402.81*** | 224.72*** | .90 |

| Quantum Computers, Log yi,t | .245*** | −486.79*** | 247.71*** | .91 |

| Quantum Computing, Log yi,t | .258*** | −512.86*** | 282.64*** | .92 |

| Quantum Cryptography, Log yi,t | .153*** | −303.17*** | 127.82*** | .84 |

| Quantum Electronics, Log yi,t | 0.003 | 0.070 | .240 | .01 |

| Quantum Emitters, Log yi,t | .155*** | −309.11*** | 141.66*** | .85 |

| Quantum Optics, Log yi,t | .145*** | −288.19*** | 150.87*** | .86 |

| Semiconductor Quantum Dots, Log yi,t | .136*** | −267.35*** | 114.69*** | .82 |

5. Discussion, Policy and Managerial Implications

- − Quantum Electronics

- − Quantum Emitters

- − Quantum Optics,

- − Semiconductor Quantum Dots

5.1. Theoretical implications

- High interaction with manifold technologies

- Generalist behaviour and adaptation to a variety of industries and sectors generating new and improved products and processes

- Disruption of previous technologies or creation of new ecosystems with the coexistence of technologies. Some new quantum technologies also change dynamic capabilities (the organization’s ability to integrate, build, and reconfigure internal and external competences and digital competences to address rapidly changing environments; Bachmann et al., 2024; Tariq et al., 2024; Teece et al. 1997)

- High economic and social impact that can cause significant economic benefits by affecting different industries and supporting social change.

5.2. Managerial and policy implications

- R&D investments that are directed to innovation development, to the adoption of new technologies and their rapid adaptability to the pace of technological change.

- Involvement of stakeholders, employees, customers, and partners, to understand new problems and needs for improving innovation avenues of new quantum technologies.

- Training programs to keep human resources updated on the latest technological advances and security practices

- Implement security measures to ensure that data are protected through encryption, firewalls, and regular security audits

- I.

- New infrastructure investments to build the necessary innovation ecosystem that supports R&D and the adoption of new quantum technologies.

- II.

- Optimal rate of R&D investments to foster and drive innovation in socioeconomic systems (Coccia, 2018).

- III.

- Public education to train population in new quantum technologies and their potential impacts in practical contexts.

- IV.

- Collaboration and partnerships between different subjects (government, industry, and academia) with a triple helix perspective to leverage know-how and use of resources (Leydesdorff and Etzkowitz, 1998). International collaboration to develop and implement new quantum technologies and to create appropriate regulations by ensuring responsible use in practical contexts (Li et al., 2025).

6. Conclusion and Prospects

6.1. Limitations and ideas for future studies on emerging quantum technologies

Availability of Data and Materials

Ethics Approval and Consent to Participate

Informed Consent

Competing Interests

Funding

References

- Acín, A.; Bloch, I.; Buhrman, H.; Calarco, T.; Eichler, C.; Eisert, J.; Esteve, D.; Gisin, N.; Glaser, S.J.; Jelezko, F.; et al. The quantum technologies roadmap: a European community view. New J. Phys. 2018, 20, 080201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adner, R. When are technologies disruptive? a demand-based view of the emergence of competition. Strat. Manag. J. 2002, 23, 667–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amarlou, A. , & Coccia, M. ( 8(2), 117–121. [CrossRef]

- Anastopoulos, I.; Bontempi, E.; Coccia, M.; Quina, M.; Shaaban, M. Sustainable strategic materials recovery, what’s next? Next Sustain. 2023, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ardito, L.; Coccia, M.; Petruzzelli, A.M. Technological exaptation and crisis management: Evidence from COVID-19 outbreaks. R&D Manag. 2021, 51, 381–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arthur B., W. 2009. The Nature of Technology. What it is and How it Evolves. Free Press, Simon & Schuster.

- Arute, F.; Arya, K.; Babbush, R.; Bacon, D.; Bardin, J.C.; Barends, R.; Biswas, R.; Boixo, S.; Brandao, F.G.S.L.; Buell, D.A.; et al. Quantum supremacy using a programmable superconducting processor. Nature 2019, 574, 505–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atik, J.; Jeutner, V. Quantum computing and computational law. Law, Innov. Technol. 2021, 13, 302–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Núñez-Delgado, A.; Bontempi, E.; Zhou, Y.; Álvarez-Rodríguez, E.; López-Ramón, M.V.; Coccia, M.; Zhang, Z.; Santás-Miguel, V.; Race, M. Editorial of the Topic “Environmental and Health Issues and Solutions for Anticoccidials and Other Emerging Pollutants of Special Concern”. Processes 2024, 12, 1379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bachmann, N.; Rose, R.; Maul, V.; Hölzle, K. What makes for future entrepreneurs? The role of digital competencies for entrepreneurial intention. J. Bus. Res. 2024, 174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batra, K.; Zorn, K.M.; Foil, D.H.; Minerali, E.; Gawriljuk, V.O.; Lane, T.R.; Ekins, S. Quantum Machine Learning Algorithms for Drug Discovery Applications. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2021, 61, 2641–2647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, C. H.; et al. (1992). Experimental Quantum Cryptography. Journal of Cryptology, 5(1), 3-28. [CrossRef]

- Bickley, S.J.; Chan, H.F.; Schmidt, S.L.; Torgler, B. Quantum-sapiens: the quantum bases for human expertise, knowledge, and problem-solving. Technol. Anal. Strat. Manag. 2021, 33, 1290–1302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyack, K.W.; Börner, K.; Klavans, R. Mapping the structure and evolution of chemistry research. Scientometrics 2008, 79, 45–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bresnahan, T. (2010). ‘General purpose technologies’, in Hall, B.H. and Rosenberg, N. (Eds.): Handbook of the Economics of Innovation, Ch. 18, Vol. 2, Elsevier, Amsterdam.

- Bresnahan, T.F.; Trajtenberg, M. General purpose technologies ‘Engines of growth’? J. Econ. 1995, 65, 83–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calabrese, G.; Coccia, M.; Rolfo, S. Strategy and market management of new product development and incremental innovation: evidence from Italian SMEs. Int. J. Prod. Dev. 2005, 2, 170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calvano, E. (2007). Destructive Creation, Working Paper Series in Economics and Finance, No.653, December, Stockholm School of Economics.

- Carberry, D. , Nourbakhsh, A. S. ( 50, 2065–2070.

- Cavallo, E.; Ferrari, E.; Bollani, L.; Coccia, M. Strategic management implications for the adoption of technological innovations in agricultural tractor: the role of scale factors and environmental attitude. Technol. Anal. Strat. Manag. 2013, 26, 765–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavallo, E.; Ferrari, E.; Bollani, L.; Coccia, M. Attitudes and behaviour of adopters of technological innovations in agricultural tractors: A case study in Italian agricultural system. Agric. Syst. 2014, 130, 44–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavallo, E.; Ferrari, E.; Coccia, M. Likely technological trajectories in agricultural tractors by analysing innovative attitudes of farmers. Int. J. Technol. Policy Manag. 2015, 15, 158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.-Y.; Zeng, G.-J.; Lin, F.-J.; Chou, Y.-H.; Chao, H.-C. Quantum cryptography and its applications over the internet. IEEE Netw. 2015, 29, 64–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coccia, M. Sources of technological innovation: Radical and incremental innovation problem-driven to support competitive advantage of firms. Technol. Anal. Strat. Manag. 2017, 29, 1048–1061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coccia, M. 2017a. Sources of disruptive technologies for industrial change. L’industria –rivista di economia e politica industriale, vol. 38, n. 1, pp. [CrossRef]

- Coccia, M. The Fishbone diagram to identify, systematize and analyze the sources of general purpose technologies. J. Soc. Adm. Sci. 2017, 4, 291–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coccia, M. 2019a. Comparative Theories of the Evolution of Technology. In: Farazmand A. (ed.) Global Encyclopedia of Public Administration, Public Policy, and Governance. Springer, Cham. [CrossRef]

- Coccia, M. 2020. Destructive Technologies for Industrial and Corporate Change. In: Farazmand A. (eds), Global Encyclopedia of Public Administration, Public Policy, and Governance. [CrossRef]

- Coccia, M. 2020a. Fishbone diagram for technological analysis and foresight. Int. J. Foresight and Innovation Policy, Vol. 14, Nos. 2/3/4, pp. 225-247. [CrossRef]

- Coccia, M. 2021. Technological Innovation. The Blackwell Encyclopedia of Sociology. Edited by George Ritzer and Chris Rojek. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. [CrossRef]

- Coccia, M. Probability of discoveries between research fields to explain scientific and technological change. Technol. Soc. 2022, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coccia, M. 2023. Innovation Failure: Typologies for appropriate R&D management. Journal of Social and Administrative Sciences - J. Adm. Soc. Sci. - JSAS - vol. 10, n.1-2 (March-June), pp. -30. [CrossRef]

- Coccia, M. New Perspectives in Innovation Failure Analysis: A taxonomy of general errors and strategic management for reducing risks. Technol. Soc. 2023, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coccia, M. Technological trajectories in quantum computing to design a quantum ecosystem for industrial change. Technol. Anal. Strat. Manag. 2022, 36, 1733–1748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coccia, M. Converging Artificial Intelligence and Quantum Technologies: Accelerated Growth Effects in Technological Evolution. Technologies 2024, 12, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coccia, M. The General Theory of Scientific Variability for Technological Evolution. Sci 2024, 6, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coccia, M. 2025. Invasive technologies: Technological paradigm shift in generative artificial intelligence. Journal of Innovation, Technology and Knowledge Economy, 1(1), pp. 1–32. Retrieved from https://journals.econsciences.com/index.php/JITKE/article/view/2522.

- D’aUrelio, S.E.; Bayerbach, M.J.; Barz, S. Boosted quantum teleportation. npj Quantum Inf. 2025, 11, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deshmukh, S. , and Mulay, P. (2021). Quantum Clustering Drives Innovations: A Bibliometric. and Patento metric Analysis, Library Philosophy and Practice, 1.

- Ding, Y.; Chowdhury, G.G.; Foo, S. Journal as Markers of Intellectual Space: Journal Co-Citation Analysis of Information Retrieval Area, 1987–1997. Scientometrics 2000, 47, 55–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dowling, J.P.; Milburn, G.J.; MacFarlane, A.G.J. Quantum technology: the second quantum revolution. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. A: Math. Phys. Eng. Sci. 2003, 361, 1655–1674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Y.; Li, B.-H.; Hua, X.; Cao, X.-Y.; Zhao, Z.; Xie, F.; Zhang, Z.; Yin, H.-L.; Xiao, X.; Wei, K. Chip-integrated quantum signature network over 200 km. Light. Sci. Appl. 2025, 14, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duncan, R. 1976. The ambidextrous organization: Designing dual structures for innovation. Killman, R. H., L. R. Pondy, and D. Sleven (eds.) The Management of Organization. New York: North Holland. 167-188.

- Coccia, M. , Ghazinoori S., Roshani S. 2023. Evolutionary Pathways of Ecosystem Literature in Organization and Management Studies. Research Square. [CrossRef]

- Coccia, M.; Roshani, S.; Mosleh, M. Scientific Developments and New Technological Trajectories in Sensor Research. Sensors 2021, 21, 7803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coccia, M.; Roshani, S.; Mosleh, M. Evolution of Sensor Research for Clarifying the Dynamics and Properties of Future Directions. Sensors 2022, 22, 9419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cozzens, S.; Gatchair, S.; Kang, J.; Kim, K.-S.; Lee, H.J.; Ordóñez, G.; Porter, A. Emerging technologies: quantitative identification and measurement. Technol. Anal. Strateg. Manag. 2010, 22, 361–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glänzel, W.; Thijs, B. Using ‘core documents’ for detecting and labelling new emerging topics. Scientometrics 2011, 91, 399–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, B.H. , and Rosenberg, N. (Eds.) (2010). Handbook of the Economics of Innovation, Vols. 1-2, Elsevier, Amsterdam.

- Harrow, A.W.; Montanaro, A. Quantum computational supremacy. Nature 2017, 549, 203–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hensen, B.; Bernien, H.; Dréau, A.E.; Reiserer, A.; Kalb, N.; Blok, M.S.; Ruitenberg, J.; Vermeulen, R.F.L.; Schouten, R.N.; Abellán, C.; et al. Loophole-free Bell inequality violation using electron spins separated by 1.3 kilometres. Nature 2015, 526, 682–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holter, C.T.; Inglesant, P.; Jirotka, M. Reading the road: challenges and opportunities on the path to responsible innovation in quantum computing. Technol. Anal. Strat. Manag. 2021, 35, 844–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inglesant, P.; Holter, C.T.; Jirotka, M.; Williams, R. Asleep at the wheel? Responsible Innovation in quantum computing. Technol. Anal. Strat. Manag. 2021, 33, 1364–1376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaeger, L. (2018). The Second Quantum Revolution: From Entanglement to Quantum Computing and Other Super-Technologies, Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany.

- Jaffe, A.B. , and Trajtenberg, M. (2002). Patents, Citations, and Innovations: A Window on the Knowledge Economy.

- Jiang, S.-Y.; Chen, S.-L. Exploring landscapes of quantum technology with Patent Network Analysis. Technol. Anal. Strat. Manag. 2021, 33, 1317–1331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jovanovic, B. and Rousseau, P.L. (2005). ‘General purpose technologies’, in Aghion, P. and Durlauf, S.N. (Eds.): Handbook of Economic Growth, Ch. 18, Vol. 1B, Elsevier, Amsterdam.

- Jovanovic, M.; Sjödin, D.; Parida, V. Co-evolution of platform architecture, platform services, and platform governance: Expanding the platform value of industrial digital platforms. Technovation 2022, 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kargi, B. , Coccia M.2025. Lessons learned of COVID-19 containment policies on public health and economic growth: new perspectives to face future emergencies. Discover Public Health 22, 56 (2025). [CrossRef]

- Kargı B., Uçkaç B. C., Coccia, M., (2025). Regional Responses to COVID-19 in Italy: A Comparative Analysis of Public Health Interventions and their Impact. Post-COVID-19 Society and Profound Societal Shifts (pp.1-23), London: IntechOpen.

- Kargı, B.; Coccia, M.; Uçkaç, B.C. ; Rasyidah Determinants Generating General Purpose Technologies in Economic Systems: A New Method of Analysis and Economic Implications. JOIV : Int. J. Informatics Vis. 2024, 8, 1791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kargı, B. Coccia M., 2024. Rethinking the Role of Vaccinations in Mitigating COVID-19 Mortality: A Cross-National Analysis. KMÜ Sosyal ve Ekonomik Araştırmalar Dergisi, KMU Journal of Social and Economic Research 26(47), 1173-1192. [CrossRef]

- Kargi, B.; Coccia, M. Emerging innovative technologies for environmental revolution: a technological forecasting perspective. Int. J. Innov. 2024, 12, e27000–e27000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kargı, B.; Coccia, M.; Uçkaç, B.C. ; Rasyidah Determinants Generating General Purpose Technologies in Economic Systems: A New Method of Analysis and Economic Implications. JOIV : Int. J. Informatics Vis. 2024, 8, 1791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kargı, B.; Coccia, M. The Developmental Routes Followed by Smartphone Technology Over Time (2008-2018 Period). Èkon. Teor. ve Anal. Derg. 2024, 9, 369–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kargı, B.; Coccia, M. The Developmental Routes Followed by Smartphone Technology Over Time (2008-2018 Period). Èkon. Teor. ve Anal. Derg. 2024, 9, 369–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, F.S.; La Torre, D. Quantum information technology and innovation: a brief history, current state and future perspectives for business and management. Technol. Anal. Strat. Manag. 2021, 33, 1281–1289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, I. (2021). “Will Quantum Computers Truly Serve Humanity?” Scientific American 17/02/2021 February 17, 2021. https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/will-quantum-computers-truly-serve-humanity/ Accessed: December 2021.

- Kocher, C.A.; Commins, E.D. Polarization Correlation of Photons Emitted in an Atomic Cascade. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1967, 18, 575–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozlowski, W. , S. (2019). Towards Large-Scale Quantum Networks. In C. Contag, T. Melodia (Eds.), Proceedings of the 6th ACM International Conference on Nanoscale Computing and Communication, NANOCOM 2019. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Awad, A.I.; Sharma, G.; Krishnamurthi, R.; Jain, S.; Srikanth, P.; Sharma, K.; Hedabou, M.; Sood, S. Artificial intelligence and blockchain for quantum satellites and UAV-based communications: a review. Quantum Mach. Intell. 2025, 7, 1–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanzagorta, M. , Uhlmann, J. K. (2009). Quantum Computer Science. Morgan & Claypool Publishers.

- Leydesdorff, L.; Etzkowitz, H. The Triple Helix as a model for innovation studies. Sci. Public Policy 1998, 25, 195–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K. , Jia W., Li Z. 2025. Regulation of Appropriate Prompts for Users in Text-Based Generative Artificial Intelligence Programs. Software - Practice and Experience, 55(4), pp.

- Li, G., Wu, A., Shi, Y., (...), Ding, Y., and Xie, Y. (2021). On the Co-Design of Quantum Software and Hardware. Proceedings of the 8th ACM International Conference on Nanoscale Computing and Communication, NANOCOM 2021, April 15.

- Lipsey, R.G. , Bekar, C.T. and Carlaw, K.I. (1998). What requires explanation? in Helpman, E. (Ed.): General Purpose Technologies and Long-term Economic Growth, pp.15–54, MIT Press, Cambridge, MA.

- Lipsey, R.G. , Carlaw, K.I., and Bekar, C.T. (2005). Economic Transformations: General Purpose Technologies and Long Term Economic Growth, Oxford University Press, Oxford.

- Long, G.L., Mueller, P., and Patterson, J. (2019). Introducing Quantum Engineering. Quantum Eng. 1, e6.

- Coccia, M.; Roshani, S. Evolutionary Phases in Emerging Quantum Technologies: General Theoretical and Managerial Implications for Driving Technological Evolution. IEEE Trans. Eng. Manag. 2024, 71, 8323–8338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- March, J. G. (1991). Exploration and exploitation in organizational learning. Organization Science, 2, 71-87.

- Möller, M.; Vuik, C. On the impact of quantum computing technology on future developments in high-performance scientific computing. Ethic- Inf. Technol. 2017, 19, 253–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosleh, M.; Roshani, S.; Coccia, M. Scientific laws of research funding to support citations and diffusion of knowledge in life science. Scientometrics 2022, 127, 1931–1951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nelson, R.R. Factors affecting the power of technological paradigms. Ind. Corp. Chang. 2008, 17, 485–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, M.A. , and Chuang, I.L. (2010). Quantum Computation and Quantum Information (2nd ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Núñez-Delgado, A.; Bontempi, E.; Coccia, M.; Kumar, M.; Farkas, K.; Domingo, J.L. SARS-CoV-2 and other pathogenic microorganisms in the environment. Environ. Res. 2021, 201, 111606–111606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Núñez-Delgado, A.; Bontempi, E.; Zhou, Y.; Álvarez-Rodríguez, E.; López-Ramón, M.V.; Coccia, M.; Zhang, Z.; Santás-Miguel, V.; Race, M. Editorial of the Topic “Environmental and Health Issues and Solutions for Anticoccidials and Other Emerging Pollutants of Special Concern”. Processes 2024, 12, 1379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Núñez-Delgado, A.; Zhang, Z.; Bontempi, E.; Coccia, M.; Race, M.; Zhou, Y. New Research on Detection and Removal of Emerging Pollutants; MDPI AG: Basel, Switzerland, 2024; ISBN:.

- Núñez-Delgado, A.; Zhang, Z.; Bontempi, E.; Coccia, M.; Race, M.; Zhou, Y. New Research on Detection and Removal of Emerging Pollutants; MDPI AG: Basel, Switzerland, 2024; ISBN:.

- Oh, D.-S.; Phillips, F.; Park, S.; Lee, E. Innovation ecosystems: A critical examination. Technovation 2016, 54, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliver, W.D. Quantum computing takes flight. Nature 2019, 574, 487–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pagliaro, M.; Coccia, M. How self-determination of scholars outclasses shrinking public research lab budgets, supporting scientific production: a case study and R&D management implications. Heliyon 2021, 7, e05998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raisch, S.; Birkinshaw, J. Organizational Ambidexterity: Antecedents, Outcomes, and Moderators. J. Manag. 2008, 34, 375–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramya, R.; Kumar, P.; Dhanasekaran, D.; Kumar, R.S.; Sharavan, S.A. A review of quantum communication and information networks with advanced cryptographic applications using machine learning, deep learning techniques. Frankl. Open 2025, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosegger, G. (1980). The Economics of Production and Innovation, Pergamon Press, NY.

- Coccia, M.; Roshani, S. Evolutionary Phases in Emerging Quantum Technologies: General Theoretical and Managerial Implications for Driving Technological Evolution. IEEE Trans. Eng. Manag. 2024, 71, 8323–8338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coccia, M.; Roshani, S. Path-Breaking Directions in Quantum Computing Technology: A Patent Analysis with Multiple Techniques. J. Knowl. Econ. 2024, 1–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coccia, M.; Roshani, S. Evolution of topics and trends in emerging research fields: multiple analyses with entity linking, Mann–Kendall test and burst methods in cloud computing. Scientometrics 2024, 129, 5347–5371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coccia, M.; Roshani, S. General laws of funding for scientific citations: how citations change in funded and unfunded research between basic and applied sciences. J. Data Inf. Sci. 2024, 9, 71–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coccia, M.; Roshani, S.; Mosleh, M. Evolution of Quantum Computing: Theoretical and Innovation Management Implications for Emerging Quantum Industry. IEEE Trans. Eng. Manag. 2024, 71, 2270–2280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roshani, S.; Bagherylooieh, M.-R.; Mosleh, M.; Coccia, M. What is the relationship between research funding and citation-based performance? A comparative analysis between critical disciplines. Scientometrics 2021, 126, 7859–7874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy R., R. 2025. Artificial Intelligence-Based 6G Networking. Routledge.

- Sahal, D. (1981). Patterns of Technological Innovation, Addison/Wesley Publishing. Reading, Massachusetts.

- Scarfe, L.; Hufnagel, F.; Ferrer-Garcia, M.F.; D’eRrico, A.; Heshami, K.; Karimi, E. Fast adaptive optics for high-dimensional quantum communications in turbulent channels. Commun. Phys. 2025, 8, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheidsteger, T.; Haunschild, R.; Bornmann, L.; Ettl, C. Bibliometric Analysis in the Field of Quantum Technology. Quantum Rep. 2021, 3, 549–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsevier Scopus. Available online: https://www.scopus.com/search/form.uri?display=basic (accessed on ).

- Sun, X.; Kaur, J.; Milojević, S.; Flammini, A.; Menczer, F. Social Dynamics of Science. Sci. Rep. 2013, 3, 1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tariq, A.; Sumbal, M.S.U.K.; Dabic, M.; Raziq, M.M.; Torkkeli, M. Interlinking networking capabilities, knowledge worker productivity, and digital innovation: a critical nexus for sustainable performance in small and medium enterprises. J. Knowl. Manag. 2024, 28, 179–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teece, D. J., Pisano, G., Shuen, A. 1997. Dynamic Capabilities and Strategic Management. Strategic Management Journal, 18(7), 509–533. http://www.jstor.org/stable/3088148.

- Wang, J.; Shen, L.; Zhou, W. A bibliometric analysis of quantum computing literature: mapping and evidences from scopus. Technol. Anal. Strat. Manag. 2021, 33, 1347–1363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, G. 1997. Towards A More Historical Approach to Technological Change, The Economic Journal, vol. 107, September, pp. 1560-1566.

- Yang, J.; Strandberg, I.; Vivas-Viaña, A.; Gaikwad, A.; Castillo-Moreno, C.; Kockum, A.F.; Ullah, M.A.; Muñoz, C.S.; Eriksson, A.M.; Gasparinetti, S. Entanglement of photonic modes from a continuously driven two-level system. npj Quantum Inf. 2025, 11, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coccia, M. Satisfaction, work involvement and R&D performance. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Dev. Manag. 2001, 1, 268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coccia, M. A New Approach for Measuring and Analysing Patterns of Regional Economic Growth: Empirical Analysis in Italy. Sci. Reg. 2009, 8, 71–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coccia, M. The relation between price setting in markets and asymmetries of systems of measurement of goods. J. Econ. Asymmetries 2016, 14, 168–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coccia, M.; Rolfo, S. Project management in public research organisations: strategic change in complex scenarios. Int. J. Proj. Organ. Manag. 2009, 1, 235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coccia, M.; Rajabzadeh, M.; Roshani, S. How research funding AMPS up citations and science diffusion : Insights from Nobel laureates in physics and physiology. COLLNET J. Sci. Inf. Manag. 2024, 18, 119–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Li, D.; Zhou, J.; Tan, Y.; Zheng, Y.; Liu, X. Research on quantum dialogue protocol based on the HHL algorithm. Quantum Inf. Process. 2023, 22, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhan, X.-H.; Zhong, Z.-Q.; Ma, J.-Y.; Wang, S.; Yin, Z.-Q.; Chen, W.; He, D.-Y.; Guo, G.-C.; Han, Z.-F. Experimental demonstration of long distance quantum communication with independent heralded single photon sources. npj Quantum Inf. 2025, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, N. (2021). Quantum Entanglement and Its Application in Quantum Communication. Journal of Physics: Conference Series, Vol.1827, 6th International Conference on Electronic Technology and Information Science (ICETIS 2021) 8-10 January 2021. Harbin, China.

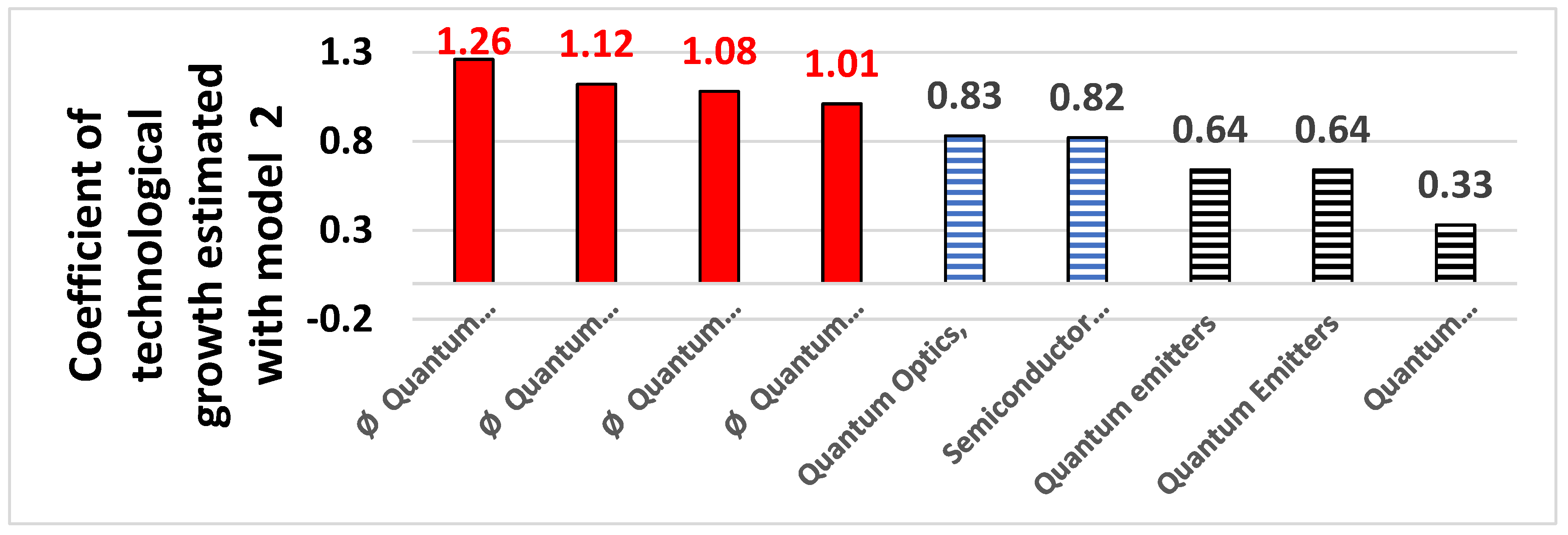

| Dependent variable: patents (Pat) in fields of quantum science | ||||

| Research fields | Coefficient b1 | Constant a | F | R2 |

| Quantum communications, Log Pat yi,t | 1.01*** | −1.34*** | 312.84*** | .90 |

| Quantum Computers, Log Pat yi,t | 1.26*** | −2.61*** | 344.89*** | .92 |

| Quantum Computing, Log Pat yi,t | 1.12*** | −1.26** | 234.21*** | .88 |

| Quantum Cryptography, Log Pat yi,t | 1.08*** | −1.89*** | 127.82*** | .95 |

| Quantum Electronics, Log Pat yi,t | 0.33*** | +3.63*** | 105.25*** | .67 |

| Quantum Emitters, Log Pat yi,t | 0.64*** | −0.08*** | 168.15*** | .88 |

| Quantum Optics, Log Pat yi,t | 0.83*** | −2.89*** | 181.46*** | .83 |

| Semiconductor Quantum Dots, Log Pat yi,t | 0.82*** | −1.35*** | 243.53*** | .88 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).