1. Introduction

In response to the global warming crisis, many countries have committed to reducing greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions by signing the Paris Agreement. Public transport operators are transitioning their bus fleets to electric vehicles to achieve lower GHG emissions [

1,

2,

3]. However, electric buses present new challenges: Battery electric buses have a shorter range compared to their diesel counterparts, necessitating more frequent recharges, sometimes multiple times a day. Moreover, the cost of the batteries required for electric buses is high, with prices increasing based on energy capacity. In many cases, electrifying bus fleets also requires significant investment in new charging infrastructure, which adds to the overall costs [

2,

4].

Trolley bus operators possess certain advantages: They can utilize hybrid trolley buses (HTBs) equipped with additional traction batteries. HTBs can perform in-motion charging (IMC) under the existing catenary grid and can travel some distance without relying on it [

5,

6]. Depending on the specific use case, between 33% and 50% of the overall track may need to be electrified [

5]. With adequate infrastructure, this requirement can sometimes be even less [

7]. HTBs allow operators to expand their network in an emission-free manner without making excessive investments in new infrastructure. Since these buses can charge while in motion, no additional stationary charging time is required.

However, HTBs must sufficiently recharge during their time under the catenary. This can lead to increased power demand per vehicle from the catenary, resulting in higher power losses in the wiring. Naive charging strategies often involve charging as much energy as quickly as possible into the traction battery, which can lead to high power peaks and potentially accelerate battery aging.

This publication aims to quantify the impact of various operating conditions on HTBs, focusing on their effects on both the grid and the vehicles’ batteries. To achieve this, we present a simulation environment that partially utilizes recorded data from a real case study. Ultimately, the authors will identify potential savings for HTB fleet operators and manufacturers which could be realized through smart charging techniques.

1.1. Related Work

Despite being over a century old, trolley buses continue to garner interest in recent publications, particularly due to innovations in lithium battery technology. This subsection provides an overview of relevant literature concerning battery aging, trolley bus grid modeling, and charging electric vehicles.

1.1.1. Battery and Battery Aging Models

Approaches to battery modeling can be broadly categorized into three groups: electrochemical models, heuristic models (mainly equivalent circuit approaches), and data-driven approaches. Electrochemical models tend to represent processes more accurately and enable the analysis of physical parameters (see [

8]). However, obtaining cell-specific parameters requires dedicated testing. In contrast, equivalent circuit models can be easily parameterized by fitting to experimental data (see [

9]). Machine learning approaches have also gained traction, but they require substantial training data to avoid overfitting (see [

10]).

The same categories apply to battery aging models. Aging mechanisms can be described based on physical considerations (see [

11]). Estimating the involved physical parameters accurately proves challenging, leading to a reliance on heuristic models to describe aging under various conditions. Comprehensive overviews can be found in [

12] and [

13]. The limitation of this approach lies in the restricted transferability between different cell types and between laboratory tests and real operations (see [

14]). Baure et al. [

15] compared battery degradation between synthetic and recorded drive cycles. Using real batteries in testing chambers, they conclude that factors such as traffic conditions, which are often overlooked in synthetic drive cycles, significantly affect battery aging. In [

16], it is illustrated how aging models can be pre-parameterized with laboratory test data and fine-tuned using operational data from a vehicle fleet, potentially leading to more accurate state of health (SoH) predictions while reducing the required aging test quantities.

1.1.2. Catenary Grid Models

Several studies have explored catenary grid models, focusing on the interaction between trolley buses and the grid.

Hamacek et al. [

17] conducted a case study in Gdynia, Poland, analyzing regenerative braking from the grid’s perspective. They evaluated potential savings from bilateral power supply systems or supercapacitors using a Monte Carlo simulation but did not consider IMC or battery models.

Stana et al. [

18] examined the kinematic and mechanical parameters of a single vehicle, presenting a physical catenary grid model based on the Škoda 24Tr Irisbus. Their simulation results included voltage drops and power losses without considering IMC or battery models.

Barbone et al. [

19] performed a case study in Bologna using a multi-vehicle motion-based modeling approach in Simulink. This study also did not incorporate IMC or battery models but analyzed various feeder sections, activating current sources for 20m spans.

In a comprehensive review, Barbone et al. [

20] discussed various approaches to modeling trolley bus catenary grids. They compared conventional analytical methods with probability-based calculations, ultimately selecting the model from [

19] as superior for Bologna’s network, without including IMC or battery models.

Paternost et al. [

21] improved grid models by incorporating voltage and current measurements from a substation in Bologna. They considered IMC vehicles, analyzing increased vehicle weight and current limitations at low speeds. Their study utilized a physical vehicle model and estimated the impact of IMC vehicles on the network.

Diab et al. [

22] assessed common simplifications in literature, exploring overhead line impedance and regenerative braking while considering a realistic velocity profile and IMC buses, though without a battery model.

Further improvements by Barbone et al. in [

23] and [

24] developed a continuous model, eliminating discretization and focusing on the trolley bus as a sliding current generator in Bologna.

Lastly, Bartlomiejczyk et al. [

25] provided a multi-faceted view of IMC buses in Gdynia, discussing battery degradation, traffic congestion impacts on charging, and conducting statistical analyses comparing IMC with opportunity charging.

1.1.3. Charging Strategies for Improving Battery Life and Grid Usage

Wang et al. [

26] investigated battery aging in scenarios where vehicles provide vehicle-to-grid (V2G) services. In their simulation environment, they examined peak load shaving, PJM frequency regulation, and net load shaping. Their findings indicate that providing V2G services consistently leads to accelerated battery aging. However, the focus of this publication is on individual electric vehicles rather than city buses.

Charging strategies for HTBs have also been explored to optimize energy usage. Diab et al. [

27] proposed a charging strategy aimed at maximizing the available power capacity of substations for IMC charging during a case study in Arnhem. This approach considered current limitations at low speeds and introduced per-substation IMC charging power based on spare capacity.

Von Kleist et al. [

28,

29] examined both IMC and opportunity charging, focusing on enhancing battery lifespan and predicting vehicle breakdowns. Their self-learning algorithm optimizes charging operations while adhering to vehicle and infrastructure limitations but does not explicitly consider grid constraints. They also do not provide the monetary benefits of applying their charging strategy to a bus fleet.

1.2. Gaps in Research

Despite advancements in the field, several research gaps persist.

As noted by Bartlomiejczyk et al. [

25], there is a lack of literature providing a multi-faceted view of HTBs. Many studies focus solely on either grid impact or battery aging, with only [

25] addressing both simultaneously. Furthermore, there is a scarcity of published simulators that utilize recorded trips for comprehensive power demand analyses throughout the day. Utilizing recorded real-world data as a source for power load on vehicles can be beneficial, as suggested by [

15]. However, few publications, including those by von Kleist et al., have employed recorded real-world data for simulative analysis or to enhance aspects of vehicle operation.

To the best of the author’s knowledge, there have been no publications offering a trolley bus simulator that incorporates recorded high-resolution real-world data to estimate fleet-wide power demand or battery aging; most publications rely on kinematic or stochastic models. Additionally, there are no known publications addressing the savings potential for trolley buses through smart charging strategies, especially those focusing on peak shaving via load shifting.

The authors of this paper present a novel approach by investigating the savings potentials of HTB fleets concerning battery and grid utilization based on recorded real-world data.

2. Materials and Methods

Using a new simulation environment primarily based on recorded data, the authors investigate various aspects of operating HTB fleets, particularly their impact on the grid and the vehicles’ batteries.

The simulation environment will quantify how different charging strategies affect both the batteries and the grid by varying strategy parameters. While it is essential to quantify the impact of the catenary grid within this simulation environment, designing the catenary grid itself is not the primary goal of this study. The main objective of this simulator is to quantify the savings potential of charging strategies and, in the future, evaluate these strategies under different conditions. To draw realistic conclusions, the simulation environment will leverage real-world data whenever possible.

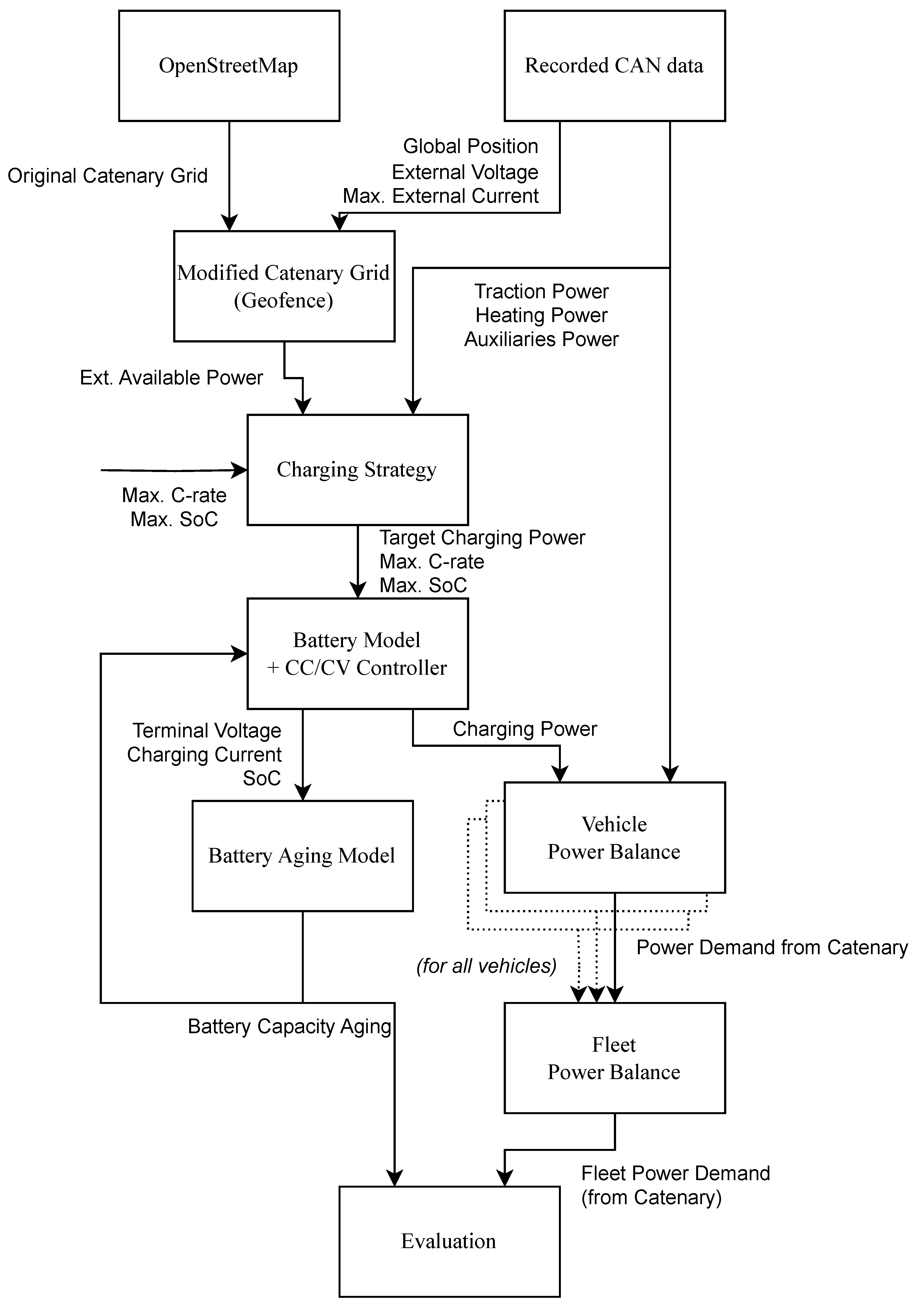

The previous chapter highlighted two entities that may benefit from a smart charging strategy: the catenary infrastructure and the vehicle’s battery. These entities need to be modeled within the simulation environment, alongside the charging strategy itself. Everything is interconnected through a basic vehicle model that performs a power balance using recorded historical data.

In the simulator, each vehicle is modeled using a recorded data set that includes its power demands and a simple customizable battery model. Sub

Section 2.1 provides detailed information on the data set used for the case study. The simulator also features a custom catenary grid for the vehicles, employing simple geofencing techniques. Each vehicle has a time-dependent location and may gain access to the catenary grid depending on its proximity. Sub

Section 2.2 elaborates on how the partial catenary grid is constructed. The vehicle can draw an arbitrary amount of power from the catenary to meet its fixed power demand or charge its traction battery. Sub

Section 2.3 details the battery model used.

With a catenary grid and a battery model available to the vehicle, the simulator retains flexibility regarding how much power to draw from the grid to charge the battery. This is where the charging strategy comes into play: it determines how much energy to charge into the battery to ensure reliable and efficient operation. Of course, this is contingent on the vehicle having access to the catenary grid. If it does not, the charging strategy has limited influence, and the consumed power, as recorded, will be drawn from the battery. While developing an optimal charging strategy is beyond the scope of this paper, a minimal charging strategy is provided. This minimal strategy may reflect the behavior of a basic HTB. Sub

Section 2.4 describes this minimal charging strategy. Based on this strategy, the author will identify opportunities for improving trolley bus operations. Future charging strategies may incorporate additional data, such as historical service trips, or engage in communication with a central service for fleet-wide coordination.

Each vehicle connected to the catenary can draw or provide power from or to the catenary. For each vehicle, this power corresponds to the sum of the recorded consumed power and the charging power. The simulation environment features a simple grid model that accounts for the power demand from the catenary for the fleet. Sub

Section 2.5 provides further insights into the grid model.

Figure 1 illustrates the general architecture of the simulation environment for one vehicle. The following subsections delve into the individual components and their data flows. At the bottom of the figure, battery capacity aging and fleet power demand are highlighted as two metrics to consider for identifying savings potential.

2.1. Recorded CAN Bus Data

Utilizing a recorded Controller Area Network (CAN) data set instead of a synthetic power usage profile can bolster claims derived from simulation results, particularly when applied to a case study.

The author has access to high-resolution CAN logs from two trolley buses spanning over three years. During this period, both vehicles serviced six lines of the transport operator. The data set encompasses various information, including but not limited to the signals listed by

Table 1.

The source of the CAN logs (i.e., the operator) will remain undisclosed, hence no Global Navigation Satellite System (GNSS) data will be presented in this paper. The maximum catenary current depends on the vehicle’s velocity to prevent overheating of the trolley pole when the bus is stationary. The CAN logs are not error-free and require processing before being input into the simulator. Specifically, the GNSS position is subject to noise in tunnels, and the service trip line and destination are not always accurately set.

The CAN logs consist of a large collection of timestamped and compressed comma-separated value (CSV) files.

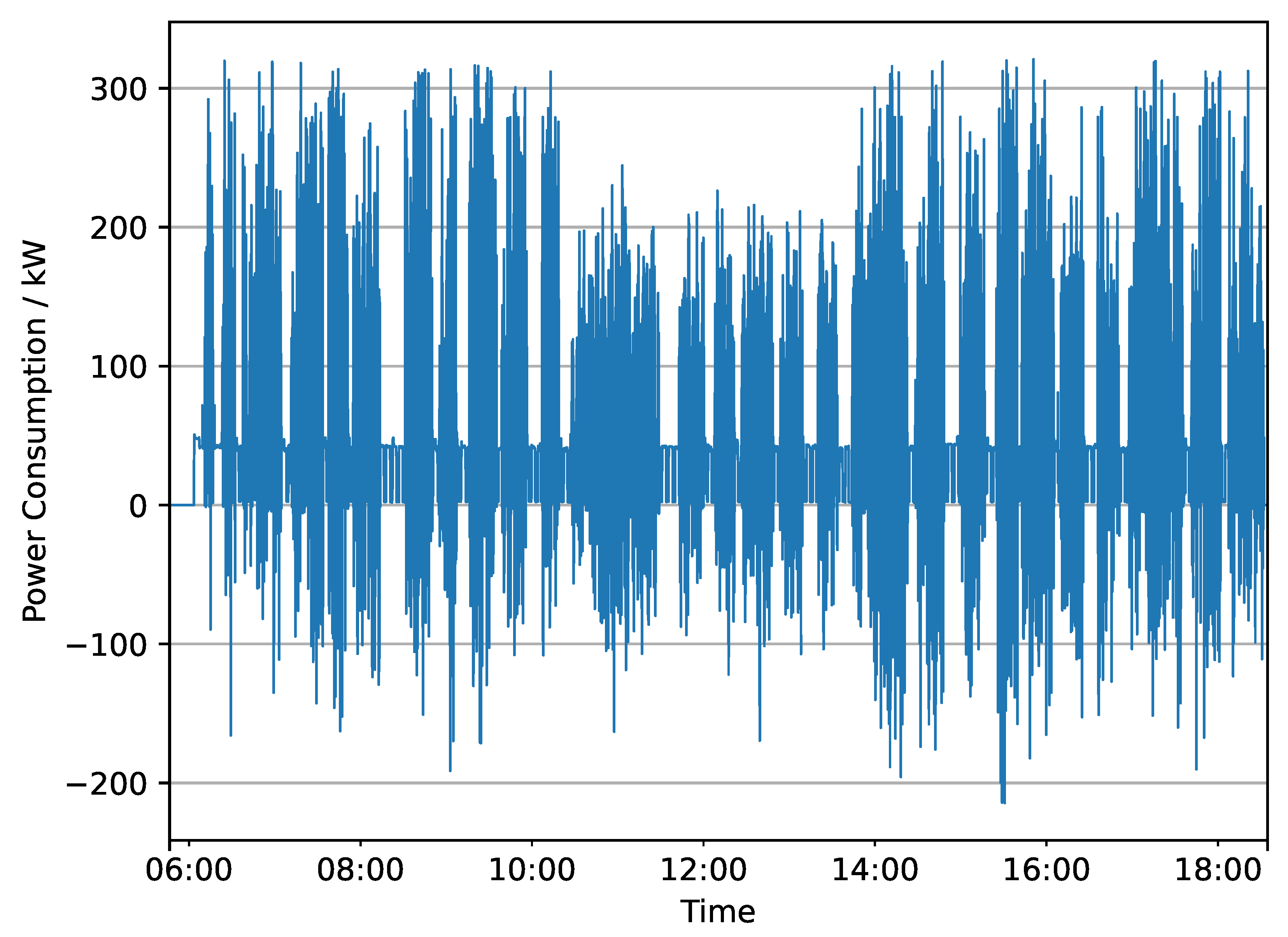

Figure 2 illustrates the vehicle’s power demand for one day in January 2022. The highly variable traction power demand, along with the 40 kW heating requirement, is evident in this figure.

The vehicle’s power demand

comprises its traction power demand

(which may be negative in cases of recuperation), heating power

, and auxiliary systems power

:

The vehicles are equipped with air conditioning systems, which are included in the auxiliary systems power demand.

2.2. Modified Partial Catenary Grid

This subsection explains why and how the simulator provides a synthetic partial catenary grid.

The recorded data set, which is to be replayed in the simulator, includes the vehicle’s global position, catenary voltage

, and maximum catenary current

. The recorded catenary voltage is influenced by many factors which cannot be distinguished at the time of writing. These factors include the output voltage from the next substation, the electric current in the catenary, and nearby recuperating vehicles. The maximum current of the pantograph is velocity-dependent. To prevent overheating of the pantograph contact, the vehicle reduces the maximum current through the pantograph when stationary. Multiplying the recorded voltage by the maximum current yields the maximum available power

at any given time:

Certain cities with trolley bus networks, particularly the city involved in this case study, have yet to exploit the potential of HTBs. The city in question has a catenary grid that fully covers all service lines. Thus, the data recordings assume constant availability of externally supplied power via the catenary grid. There are valid reasons for maintaining existing infrastructure, such as operating older vehicles without an internal traction battery. However, to investigate HTBs partially operating autonomously using recorded data, the catenary grid must be modified.

The simulator applies a partial catenary grid to the recorded data set by filtering the externally available power through a customizable geofence. This method retains the current limitation based on the vehicle’s velocity while also accounting for voltage fluctuations to approximate a realistic power supply. Before simulating, the simulator sets the externally available power to zero when the vehicle is outside the established catenary geofence at the time t.

For the case study, the original catenary grid was obtained from OpenStreetMap and subsequently modified using the software

QGIS [

30]. Catenary power lines shared between multiple lines were retained, while those exclusive to a single line were removed.

2.3. Battery Model and Battery Aging

Although the original data set includes battery data, a battery model is necessary for the simulator to evaluate the impact of charging decisions on the battery.

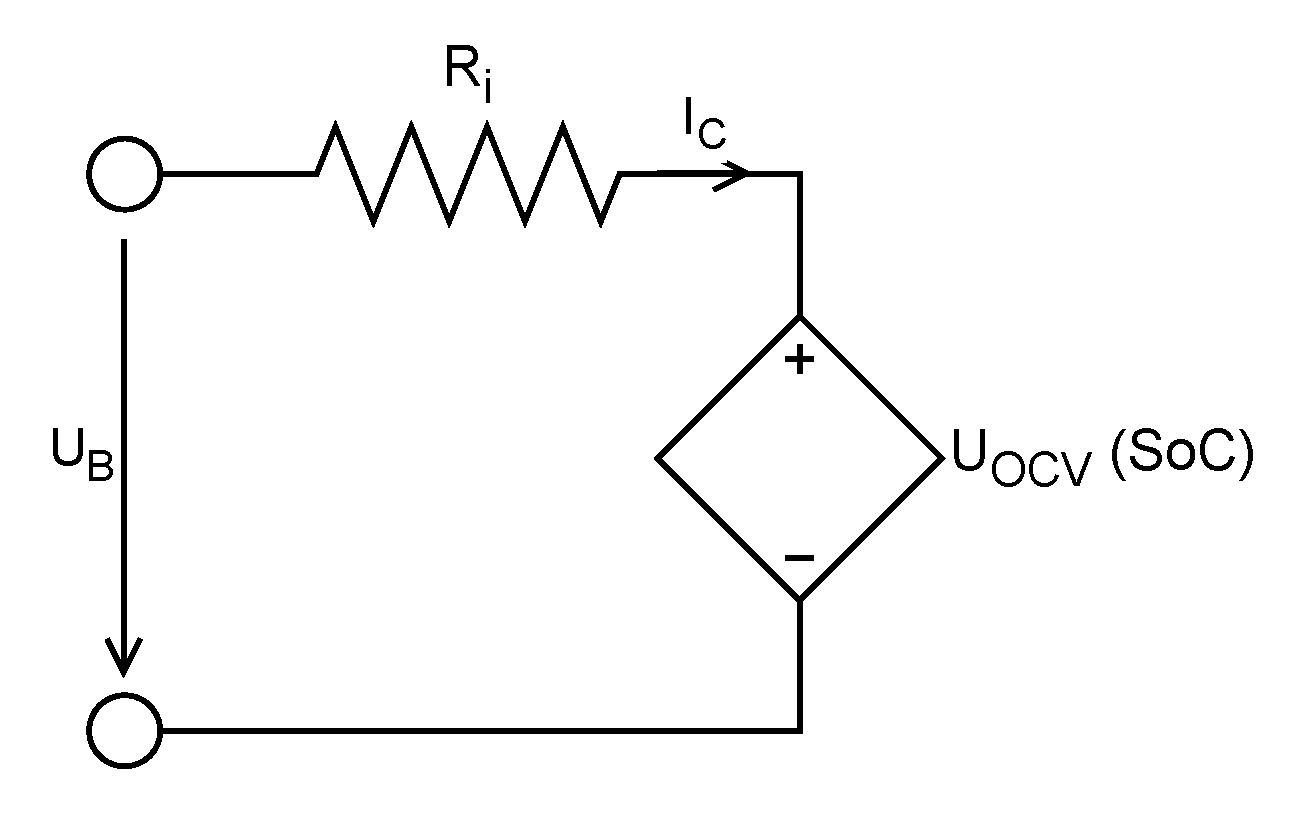

The battery model is simple, comprising a piecewise linear open circuit voltage (OCV) curve and a resistor.

Figure 3 presents the circuit diagram for the battery model used.

Currently, it does not include a temperature model; losses are represented using a simple internal resistor

. Using this model, the simulator estimates voltage, current, and state of charge (SoC) based on the power drawn from or input into the battery. The charging power

can be expressed as:

Here, the open circuit voltage

depends on the SoC, the terminal voltage

, and the charging current

. The charging current

is negative when discharging. The SoC is calculated by integrating the current over time:

where

C is the battery’s capacity, and

is the initial SoC.

The battery model incorporates a constant-current/constant-voltage (CC/CV) charging controller that attempts to apply the desired power to the battery while respecting the maximum charging rate (C-rate), maximum terminal voltage, and maximum SoC. The charging strategy (see sub

Section 2.4) dispatches a target charging power

to the charging controller. The simulator calculates the according voltage

and current

while respecting above equations and the battery’s voltage and current limits for a

. Thus, the actual charging power

may be lower than

if the battery’s maximum voltage or current would have been exceeded.

The battery model terminates the simulation if the SoC falls below zero. This model serves as a sufficient heuristic for estimating power losses, as well as voltage and current at the battery.

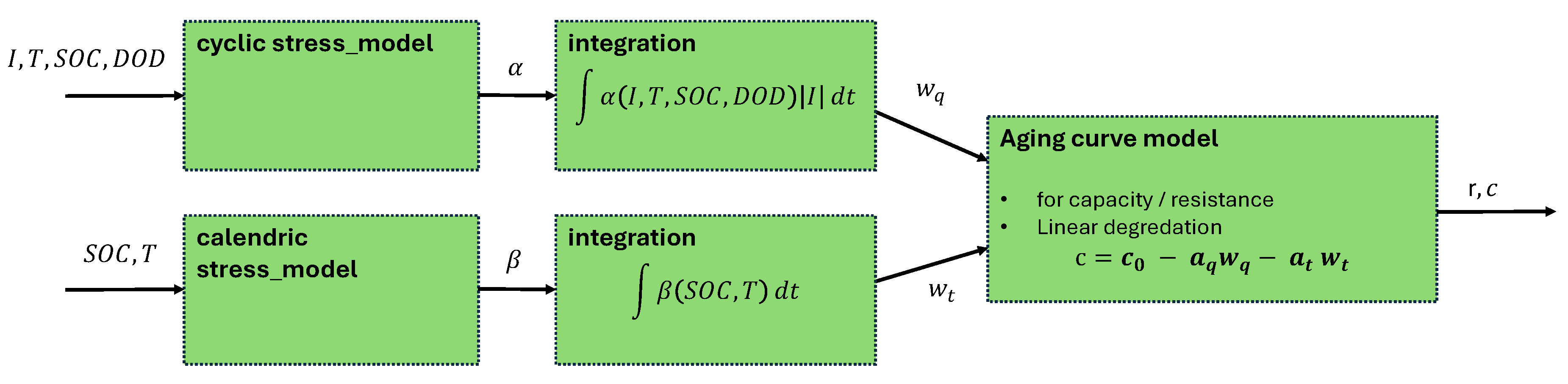

An aging model estimates the degradation of the battery’s capacity based on temperature, current, and SoC. The aging model consists of a linear aging curve and stress maps for calendric and cyclic aging (see

Figure 4).

The stress map parameters are derived from the methodology described in [

16]. The aging data was obtained from an extensive aging test campaign outlined in [

31].

Table 2 summarizes key parameters of the aging campaign.

The primary focus of the Batteries 2020 campaign was a comprehensive design of experiments (DoE), emphasizing the influence of SoC and depth of discharge (DoD). Temperature was only varied within a limited range. Most experiments involved at least three cells to account for anomalies.

2.4. Minimal Charging Strategy

This subsection motivates the need for a basic charging strategy and outlines the minimal charging strategy implemented for this case study.

With a battery electric vehicle operating partially under the catenary, each vehicle has some leeway regarding its power draw. Each HTB may draw power from the catenary to meet its current power demand and charge its traction battery. It may even discharge its battery to partially or completely cover its power demand, or, depending on the vehicle’s design, provide power to the grid. A charging strategy is a set of rules that dictates how much power to draw from the catenary at any given time. These charging strategies can be complex.

For this case study, a minimal charging strategy is assumed. This minimal strategy mimics the behavior of a basic HTB without any dynamic logic to adjust the charging current or target SoC. The strategy does not consider the remaining charging time or the energy demand for the upcoming wireless section. Instead, it conservatively assumes that the bus will leave the catenary momentarily and may not reconnect for an extended period. To avoid running out of battery under these assumptions, it aims to charge as much energy as quickly as possible until a predetermined upper SoC threshold is reached.

The minimal charging strategy relies on the CC/CV charging controller to respect the battery’s limitations, including the maximum C-rate, maximum voltage, and maximum SoC. It always attempts to charge the battery with the maximum available charging power

, which is determined by the externally available power

from the catenary and the vehicle’s current power demand

:

This charging strategy ensures reliable operation of the trolley bus fleet. However, it may be suboptimal regarding battery aging and could result in unnecessary power demand peaks for the operator.

The minimal charging strategy specifies a maximum charging rate and a target SoC, which is forwarded to the CC/CV charging controller. The target SoC can be set individually for catenary and autonomous operations, with the target SoC for autonomous operation set to 100% to minimize energy waste. The maximum charging rate is transmitted to the charging controller unconditionally.

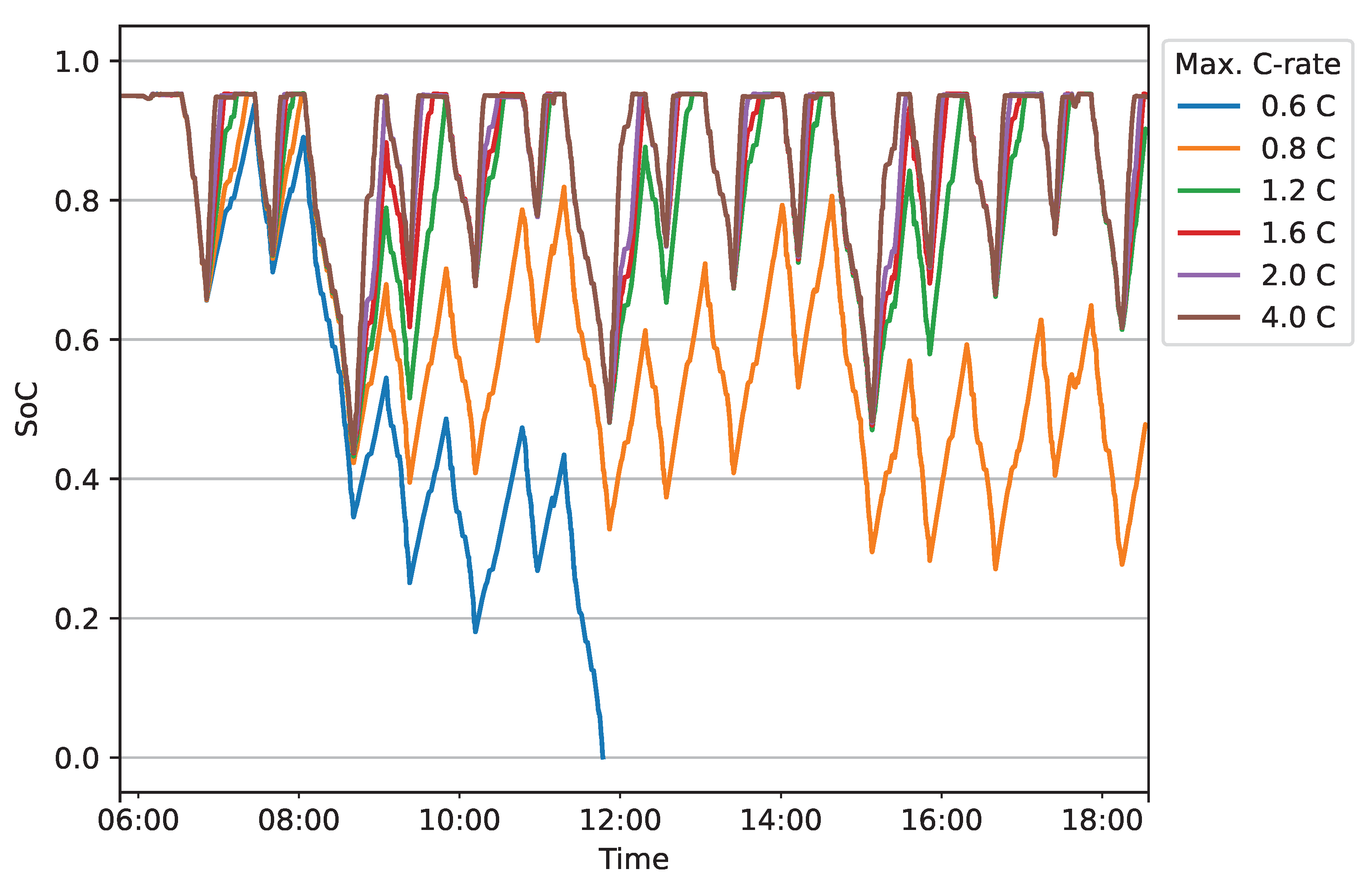

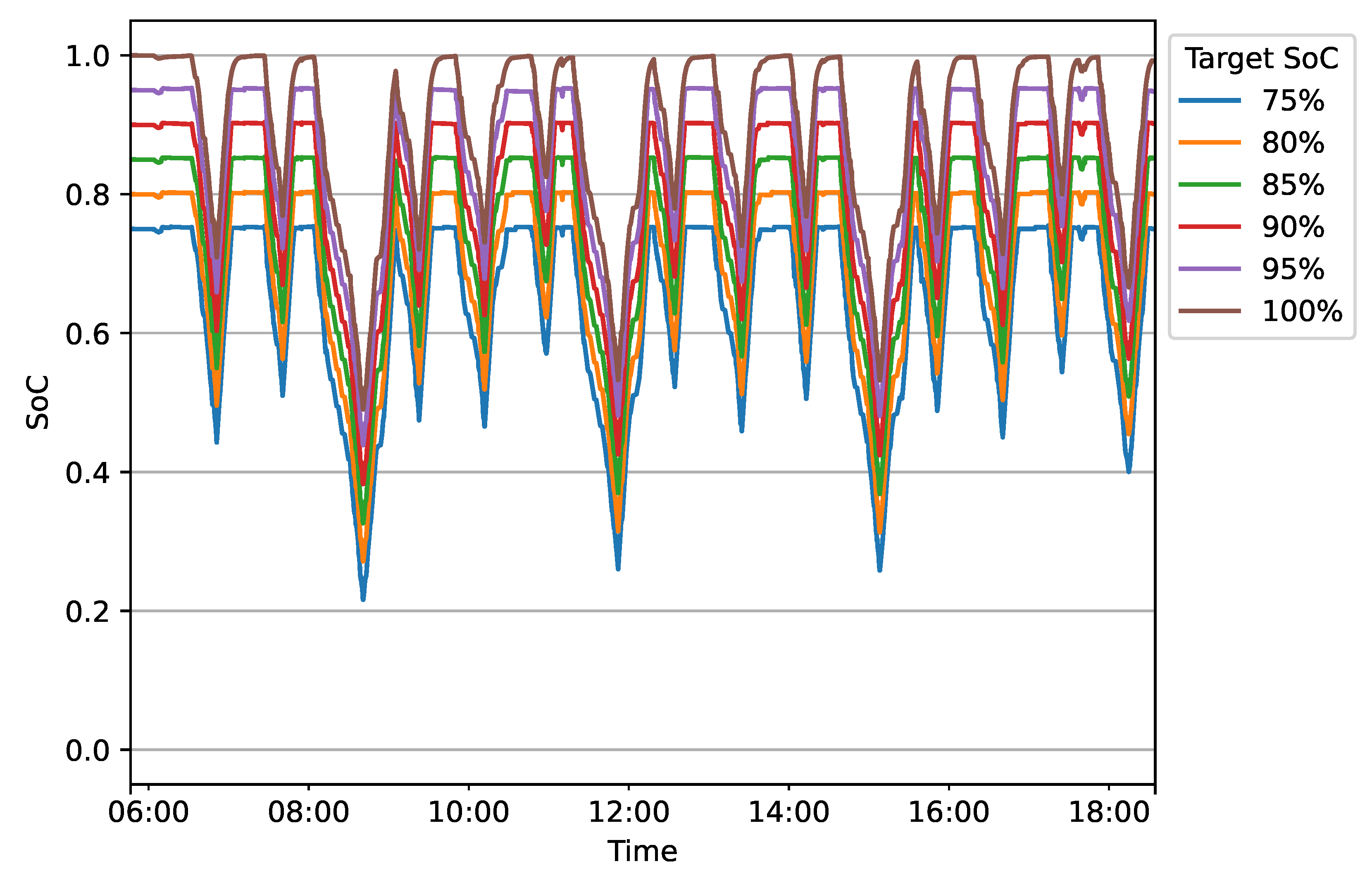

This case study employs the minimal charging strategy to evaluate how the maximum charging rate and target SoC affect battery aging.

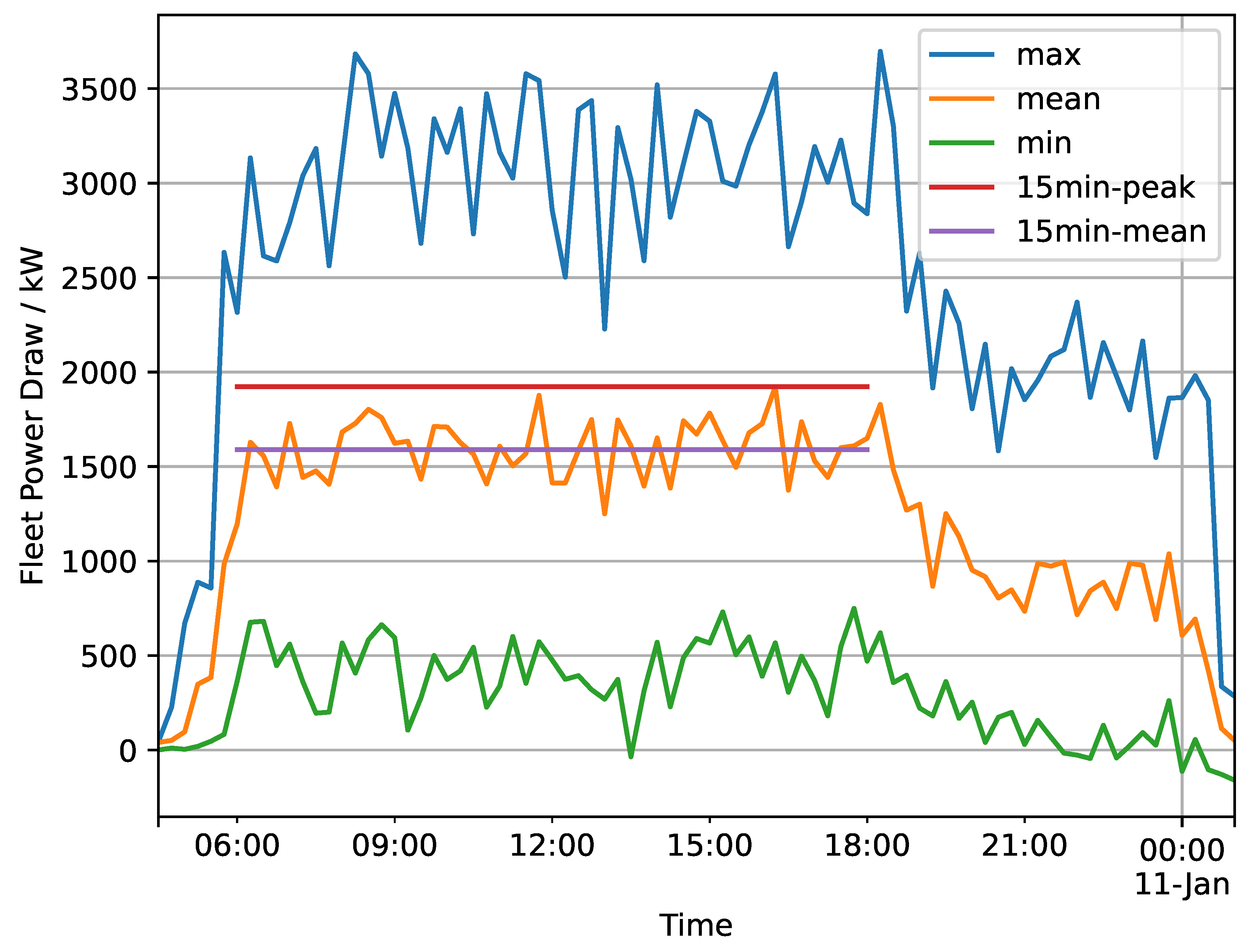

2.5. Fleet Power Demand

To indicate the bus fleet’s power demand, the simulator performs a simple summation of the power drawn from the catenary for all vehicles. While this approach is straightforward, the simulator does not account for losses within the catenary grid. In particular, there will be no increased voltage drop when a vehicle draws high current in its feeder section. Considering the voltage drop across the entire network would necessitate computationally intensive co-simulation of the catenary grid and all vehicles. The resulting fleet power demand serves as a lower bound for the fleet’s actual power requirements. Especially with multiple vehicles in the same feeder section, the voltage drop in the catenary will be highly underestimated. This simple grid model is adequate for identifying power demand peaks and indicating potential savings.

The power demand summation is implemented as a post-processing step after simulating all vehicles in parallel. For practical reasons, co-simulation of the catenary grid and vehicles will be avoided to maintain performance advantages.

The simulator assumes that a vehicle can recuperate any amount of power into the grid when connected. Each vehicle is equipped with a brake resistor, which is only utilized in autonomous sections when recuperated power from the drive train cannot be fed into other consumers or into the traction battery.