1. Introduction

Sustainable agricultural practices are essential for maintaining soil health, improving plant growth, and optimizing nutrient uptake [

1,

2]. Intensive farming and soil degradation have led to declines in soil fertility, reduced microbial diversity, and decreased nutrient availability, all of which negatively impact crop productivity [

3,

4]. Enhancing soil microbial communities through targeted interventions is a promising strategy to restore soil function and support sustainable agricultural systems [

5,

6].

Microbial inoculants, such as CFMI-8 , offer a biological approach to improving soil health and plant nutrition [

7,

8,

9]. CFMI-8 is a microbial soil inoculant developed as a consortium of eight bacterial strains selected through an integrative framework incorporating genomic analysis, metabolic modeling, and community-level simulations [

10,

11]. These strains were chosen for their complementary metabolic capabilities, including nutrient cycling, organic matter transformation, and enhancement of soil microbial activity. This approach aligns with growing evidence that microbial inoculants can improve soil structure, increase nutrient bioavailability, and promote plant growth by fostering a more balanced and resilient microbial community [

1,

12,

13].

The objective of this study was to evaluate the efficacy of CFMI-8 in enhancing soil health and nutrient availability, thereby improving agronomic performance in a commercial corn trial conducted at Findlay Farm, Whitewater, WI. The trial utilized a randomized complete block design to assess the treatment’s impact on key soil and crop parameters, such as microbial biomass, soil respiration, and nutrient uptake efficiency.

This paper focuses on the effectiveness of CFMI-8 in improving soil health metrics, promoting microbial activity, and enhancing nutrient uptake in corn production. By integrating data on microbial activity, organic matter decomposition, and crop performance, the findings contribute to a growing body of evidence supporting the use of microbial-based solutions for sustainable soil management and improved agricultural productivity [

6,

8,

14,

15,

16].

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Composition and Preparation of CFMI-8

A co-fermented microbial inoculant (CFMI-8) was developed from a consortium of eight bacterial strains, selected through an integrative framework combining genomic analysis with both individual and community-scale metabolic modeling to evaluate symbiosis, cross-feeding, and niche creation dynamics. [

10], and community-level interaction simulations. The consortium consists of spore-forming bacteria, some of which originate from ancient sources, as well as strains of lactic acid bacteria and Gammaproteobacteria. Each strain was chosen for its potential ability, as predicted by genomic annotations, to promote soil health, improve nutrient uptake by the plant, and function cooperatively within a microbial guild to enhance soil ecosystem functionality.

The co-fermented microbial inoculant (CFMI-8) comprises a consortium of eight strains, including spore-forming bacteria—some derived from ancient sources—as well as lactic acid bacteria and members of the Gammaproteobacteria. Each strain was selected based on genomic annotations predicting contributions to soil health, enhancement of plant nutrient uptake, and cooperative function within a microbial guild to improve soil ecosystem functionality. All strains were evaluated under the Biosafety in Microbiological and Biomedical Laboratories (BMBL) guidelines and classified as biosafety level 1 (BSL-1), indicating minimal risk to human and environmental health. The development process included the generation and refinement of genome-scale metabolic models using the KBase platform, enabling both individual and community-scale simulations to assess metabolic complementarity, symbiosis, cross-feeding potential, and niche construction dynamics. These models provided detailed insights into the metabolic pathways relevant to nutrient cycling, and organic matter decomposition. Community metabolic interactions were further modeled using KBase’s integrated pipeline, incorporating flux balance analysis and interspecies metabolic exchange simulations [

11].

The eight bacterial strains were co-fermented in a single batch culture to facilitate interspecies interactions and metabolic cross-feeding. Each strain was inoculated into a standardized co-fermentation medium stabilized with 2% organic molasses (FEDCO, Inc., Clinton, ME, USA). The process was conducted under controlled conditions of optimal temperature, pH, and aeration to support growth and activity. The eight bacterial strains comprising the CFMI-8 consortium were co-fermented in a single batch culture to promote interspecies interactions and metabolic cross-feeding. Each strain was introduced into a standardized co-fermentation medium supplemented with 2% organic molasses (FEDCO, Inc., Clinton, ME, USA) as a carbon source. Fermentation was carried out under controlled conditions of temperature, pH, and aeration optimized for microbial growth and metabolic activity. This co-fermentation strategy was essential for establishing cooperative dynamics and stimulating the production of postbiotic compounds critical to the consortium’s soil functionality [

17]. Upon completion, the final suspension achieved a viable cell density of approximately 5.1 × 10⁹ CFU/mL. Prior to application, the inoculant was thoroughly homogenized to ensure uniform distribution of the microbial community. This co-fermentation approach was critical for fostering the cooperative dynamics and production of postbiotics [

17].

2.2. Study Location and Conditions

This study was conducted in 2022 as part of the GLK Sauerkraut’s Corn trial at Findlay Farm, Whitewater, WI (N42.901683, W-88.762430). The experimental site was selected for its suitability for corn production and adherence to agronomic standards. The location provided optimal conditions for evaluating the efficacy of CFMI-8 broadcast treatments under field conditions. The trial followed a randomized complete block design to ensure consistency and reliability of key agronomic parameters and treatment effects on corn growth and silage production.

The field was Fall chisel plowed followed by spring field cultivation to incorporate fertilizers and level the soil prior to planting. The preceding crop was winter wheat, and the herbicide Orion had been applied in the previous season. It was not necessary to irrigate during the trial.

2.3. Experimental Design

The study was conducted following a randomized complete block (RCB) design with one factor and four replicates. CFMI-8 broadcast treatment was tested in plots measuring 10 feet by 50 feet, covering an area of 0.011 acres per plot. The corn cultivar DS 4018AMXT was planted on May 19, 2022, with a precision vacuum planter that was configured to achieve a seeding rate of 35,000 seeds per acre with a row spacing of 30 inches (cm) and a planting depth of 2.25 inches (5.72 cm).

Fertilizer applications were conducted in two phases. On December 1, 2021, a pre-plant application of ninety pounds (kg) per acre of 11-52-0 and 200 pounds (90.7 kg) per acre of 0-0-62 was made. The following May 5, an additional application of four hundred thirty-five pounds (kg) per acre of 46-0-0 was applied. Pesticides were also applied at critical growth stages. Accuron (Syngenta, Basel, Switzerland) was applied at a rate of one and a half pints per acre, and Atrazine (Syngenta, Basel, Switzerland) was applied at a rate of one pound (kg) per acre pre-emergence on May 20, 2022. Post-emergence applications included Halex GT (Syngenta, Basel, Switzerland) applied at a rate of four liters per acre and Roundup WeatherMax (Monsanto, St. Louis, Missouri, 63141, USA) at a rate of eight ounces (29.5 mL) per acre on June 25, 2022.

Stand density and vigor were assessed during the early growth stages while lodging was evaluated prior to harvest. Silage yield was determined by hand-harvesting two rows, each 20 feet long, per plot on September 14, 2022, using a Cadet chopper. Post-harvest measurements included silage moisture and quality. Samples harvested by hand were weighed using a field scale to ensure accurate yield estimation.

Statistical analyses were performed to evaluate treatment effects on agronomic parameters, including yield, stand density, vigor, lodging, and silage quality. Data from the six treatments were analyzed using analysis of variance (ANOVA) [

18] appropriate for the RCB design, and treatment means were compared using a significance threshold of α = 0.05.

The experiment adhered to industry standards for field trials and agronomic data collection. This study provides valuable insights into the efficacy of CFMI-8 broadcast treatments for enhancing corn growth and silage production under real-world field conditions.

2.4. Sample Collection

Soil samples were collected from agricultural fields prior to treatment with CFMI-8 and six months afterwards to assess the effectiveness of this bioremediation agent. The study included two groups: untreated soils and soils treated with CFMI-8 . Each group consisted of three independent samples. The treatment was applied at the manufacturer-recommended concentration of 1.6 × 10⁸ CFU per square meter of soil and lightly incorporated into the soil with a harrow. Samples were collected at baseline (pre-planting) and post-harvest.

2.5. Soil Health Analysis

Soil samples were analyzed at Ward Laboratories (Kearney, Nebraska, USA; wardlab.com) to assess key indicators of soil health. Organic carbon (ppm) and organic nitrogen (ppm) were measured using combustion-based methods to quantify soil nutrient availability and organic matter content. Soil CO₂ respiration, a proxy for microbial activity and soil biological function, was determined through a 24-hour incubation test, with results expressed as total CO₂ release and as a percentage of microbial active carbon (% MAC) following protocols established by Haney et al. (2008) [

19]. The Soil Health Score (ppm C), a composite index incorporating soil respiration, microbial biomass, and organic carbon, was calculated using methodologies like those described by Haney et al. (2018) that provide an integrated measure of soil biological activity. Organic matter was determined using the Loss on Ignition (LOI) method where soil samples were heated to 360°C and organic matter content was calculated as a percentage of mass lost. All analyses were performed according to standardized protocols established by Ward Laboratories to ensure precision and reliability. Microbial activity in the soil was indirectly assessed by measuring soil respiration rates using a CO

2 flux chamber.

2.6. Soil Chemical Composition and Leaf Tissue Analysis

Soil and leaf tissue samples were analyzed at Rock River Laboratories (Watertown, Wisconsin, USA;

www.rockriverlab.com) to evaluate chemical composition and nutrient status. Plant tissue samples were collected as sub-samples from silage harvest plots and analyzed for moisture content, adjusted silage yield at 65% moisture, crude protein (CP), neutral detergent fiber (NDF), total tract neutral detergent fiber digestibility (TTNDFD), acid detergent fiber (ADF), starch, ash, fat, and estimations of milk production potential (milk per ton and milk per acre). These analyses were conducted by Rock River Laboratories, Omaha, NE, USA, using standardized laboratory methods for forage quality testing and included near-infrared reflectance spectroscopy (NIRS) and wet chemistry as described by Undersander et al. [

20] and Shenk & Westerhaus [

21].

Leaf tissue samples were collected at the V4 growth stage (June 14, 2022) and post-harvest sampling (September 14, 2022) from 30 plants per plot at multiple time points. The samples were analyzed for macronutrients—nitrogen (N), phosphorus (P), potassium (K), calcium (Ca), magnesium (Mg), and sulfur (S); and micronutrients—zinc (Zn), boron (B), manganese (Mn), iron (Fe), copper (Cu), sodium (Na), and molybdenum (Mo). Nutrient analyses were conducted using inductively coupled plasma optical emission spectrometry (ICP-OES) following acid digestion of the plant tissues as outlined by Jones & Case (1990) [

22]. These methods are widely used in plant tissue analysis to ensure accurate quantification of nutrient concentrations. All measurements followed the standard operating procedures of Rock River Laboratories to provide reliable and consistent data for assessing soil fertility and plant nutrient status.

2.7. Statistical Analysis

All data were analyzed using statistical methods to evaluate relationships between variables and identify key predictors of soil health, plant nutrient composition, and yield using R [

23]. Descriptive statistics were calculated for all variables to assess central tendencies and variability. Statistical analyses were performed to assess differences in AMPA levels between treated and untreated groups. An independent t-test was used for comparison, and data normality was verified using the Shapiro-Wilk test [

24]. All statistical analyses were conducted using Python’s SciPy library, with significance determined at a threshold of

p < 0.05

Environmental conditions and soil characteristics were also assessed to explore their potential influence on nutrient uptake and plant growth promotion. Soil pH was measured using a standard soil pH meter, organic matter content was determined by loss on ignition, and moisture levels were measured gravimetrically. These parameters were evaluated to provide context for the chemical and microbial analyses

2.8. Correlation Analysis

Pearson’s correlation coefficients were calculated to evaluate linear relationships between soil chemical composition, leaf tissue nutrient levels, and agronomic performance metrics such as silage yield and quality parameters (e.g., crude protein, starch content). Significant correlations were identified using a threshold of p < 0.05. Heatmaps were generated to visualize the strength and direction of the correlations among variables.

2.9. Random Forest Analysis

To identify key predictors of soil health, silage yield, and plant nutrient composition, a random forest algorithm was applied using the

RandomForest package in R [

25]. Predictor variables included soil chemical properties (e.g., organic carbon, nitrogen, and phosphorus), leaf tissue nutrient concentrations, and microbial activity measures. Random forest models were fine-tuned using cross-validation to optimize the number of trees and variables randomly selected at each split. Variable importance was assessed using the Mean Decrease in Accuracy (MDA) and Mean Decrease in Gini Index to rank predictors based on their influence on model performance [

26].

Model performance was evaluated using metrics such as R² and root mean square error (RMSE) for regression analyses [

27]. The models were validated using an out-of-bag (OOB) error estimate for random forest to ensure robustness.

All statistical analyses and visualizations were performed using R packages, including

ggplot2 [

28], for data visualization and

caret [

29] for model validation workflows. Statistical significance was set at

p < 0.05 unless otherwise noted.

3. Results

3.1. Soil Health Metrics

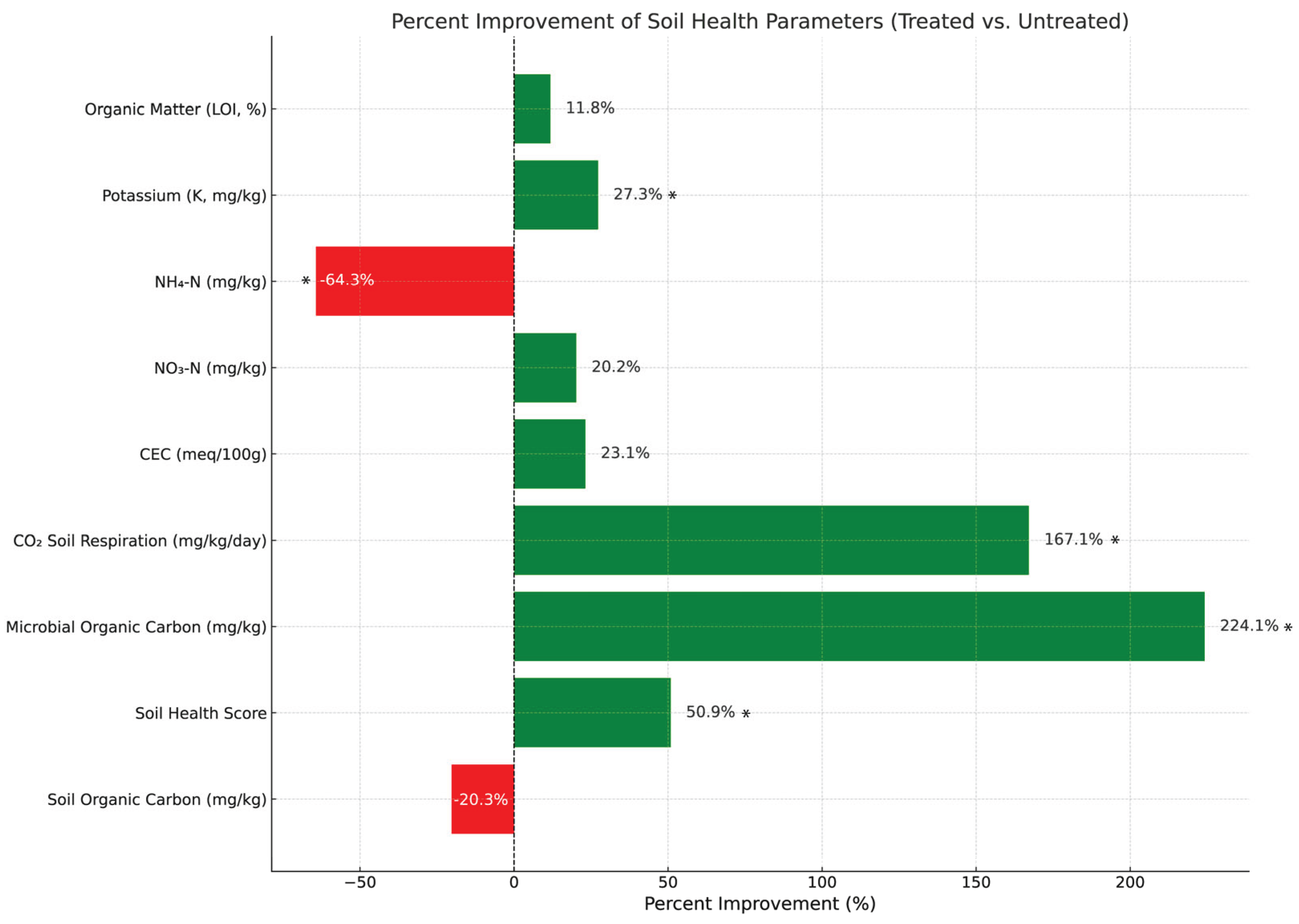

The soil health metrics reveal substantial improvements across key parameters in the treated soils compared to the untreated soils (

Table 1). Microbial organic carbon increased significantly in the treated group to average 80.48 mg/kg, a 224.1% improvement over the untreated group's 24.83 mg/kg, indicating that treatment enhanced microbial activity and nutrient cycling. Similarly, CO₂ soil respiration was substantially higher in treated soils and averaged 95.83 mg/kg/day, representing a 167.1% increase, which reflects elevated biological activity and organic matter decomposition

Soils treated with the CFMI-8 consortium exhibited notable improvements in several key fertility indicators. Nitrate nitrogen (NO₃⁻) concentrations were significantly elevated, averaging 38.15 mg/kg—a 20.2% increase compared to untreated soils (31.75 mg/kg)—suggesting enhanced nitrogen mineralization and availability for plant uptake. Cation exchange capacity (CEC) also increased by 23.1% in treated soils (8.78 meq/100 g) relative to controls (7.13 meq/100 g), indicating improved nutrient retention capacity and overall soil fertility. Potassium (K) levels were 27.3% higher in treated soils, with an average concentration of 368.75 mg/kg, reflecting greater nutrient availability (

Figure 1).

Organic matter content showed a modest but meaningful increase of 11.8%, rising from 1.70% in untreated soils to 1.90% in treated soils. Conversely, soil organic carbon decreased by 20.3% following treatment (118.00 mg/kg vs. 148.00 mg/kg in controls), likely due to increased microbial activity and carbon utilization stimulated by the inoculant.

Significant differences between treated and untreated soils (p < 0.05) are marked with an asterisk (*). The bar chart illustrates the percentage changes in key soil health parameters, comparing treated and untreated soils. Positive changes (green bars) indicate improvements in microbial organic carbon, soil respiration, cation exchange capacity (CEC), and nutrient availability, while negative changes (red bars) represent declines in certain parameters, such as soil organic carbon turnover. The bar chart was generated using Python, utilizing libraries such as Matplotlib for visualization. The graphical representation highlights the relative impact of treatment on soil health metrics, providing a clear comparison of improvements driven by microbial inoculation.

3.2. Agronomic Performance

Agronomic performance was significantly better with the treated group compared to the untreated group (

Table 2). For example, corn yield in the treated group averaged 7.20 tons/acre (a 28.6% increase) compared to the untreated group’s average of 5.60 tons/acre (

Figure 3). Similarly, corn ear density was 17.6% higher in the treated group (38.50 ears/plot,) compared to the untreated group's 32.75 ears/plot, an indicator of better crop stands and development.

There was a modest 4.6% improvement in grain yield with the treated group (average 246.40 bushels/acre) compared with the 235.57 bushels/acre of the untreated group. This increase suggests that the treatment contributed to more efficient nutrient utilization and grain development. Silage yield of 36.26 tons/acre also was notably higher in the treated group (9.6% increase) compared with the untreated group’s 33.08 tons/acre. This highlights the treatment's positive effect on biomass production. In addition to the increased biomass, the treated group produced silage with higher nutritional quality that was reflected in a 9.3% increase in silage milk per acre (121,703 lbs. vs. 111,334 lbs.) and a 2.8% increase in silage milk per ton (3,426 lbs. vs. 3,332 lbs.).

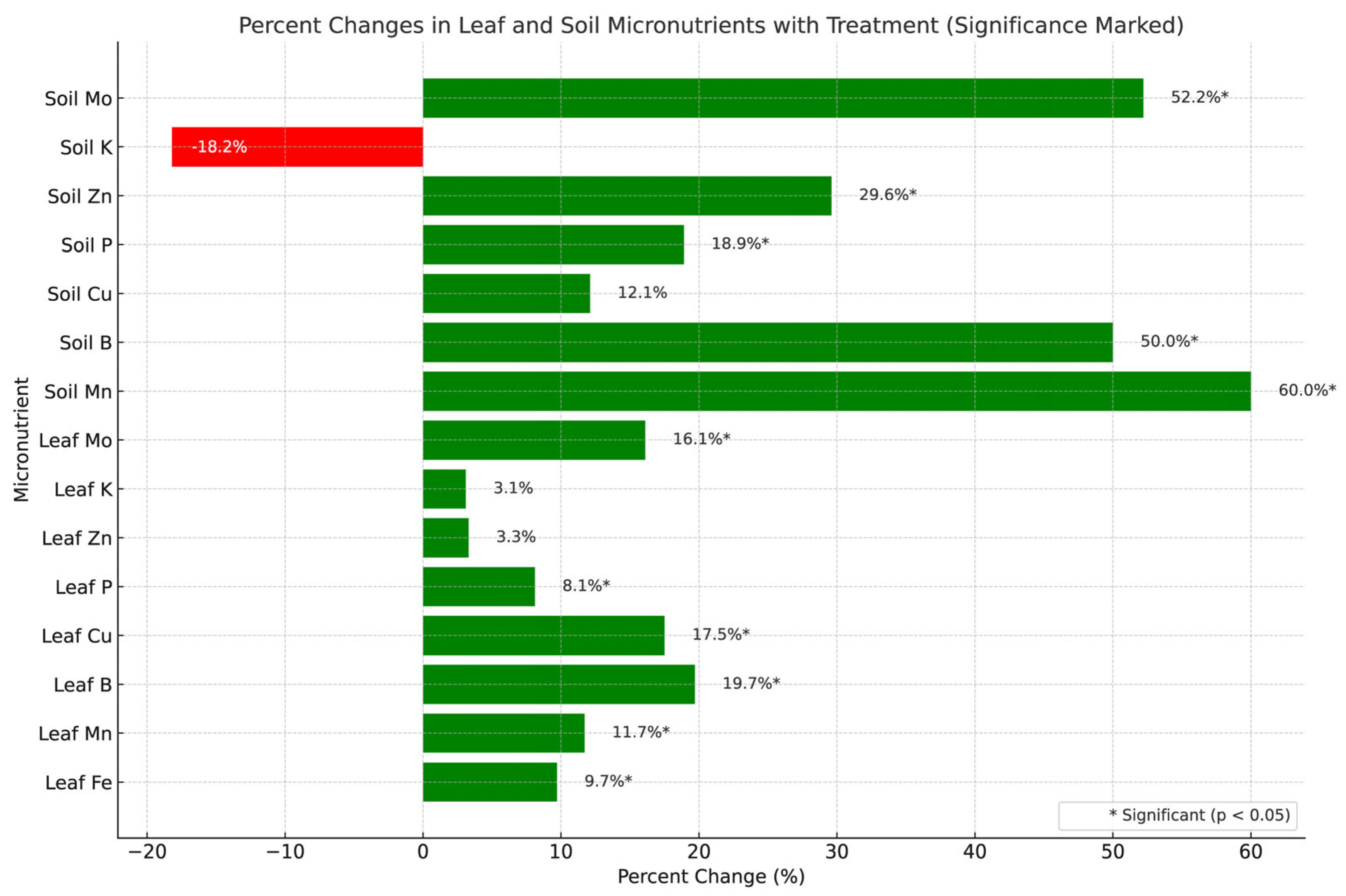

3.3. Micronutrients

Several micronutrient concentrations were significantly higher in CFMI-8 treated compared with untreated groups (

Table 3,

Figure 2).

The concentration of most nutrients analyzed for tended to be higher in CFMI-8 treated soil and leaf tissue compared with the non-treated; however, only B and Zn were significantly different in soil. Leaf B, Fe, Mn, P and Zn were significantly different in treated leaves (

Table 2,

Figure 2).

The figure illustrates relative changes in micronutrient levels between treated and untreated groups. Green bars represent improved nutrient availability or plant uptake, while red bars indicate potential decreases, likely due to higher plant absorption. Statistically significant differences (p < 0.05) are marked with an asterisk (*). This visualization, generated using Python’s Matplotlib [

30], highlights the treatment’s impact on soil fertility and plant nutrition. Percentage changes were calculated as (Treated – Untreated) / Untreated × 100, with a horizontal bar chart distinguishing positive (green) and negative (red) shifts. The chart includes annotated values, a 0% reference line, and clear axis labels for readability.

3.4. Correlation Analysis

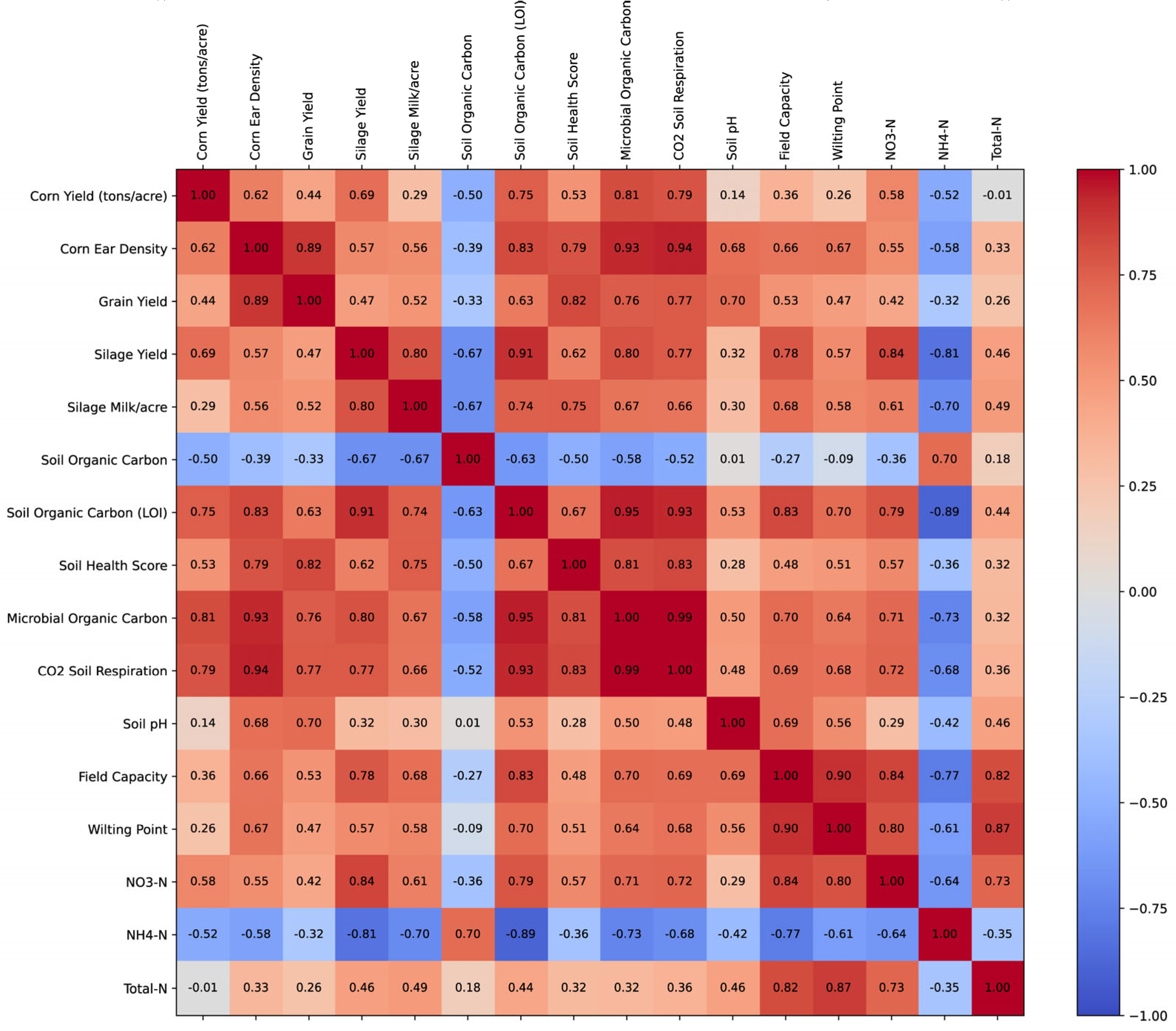

The correlation analysis (

Figure 3) revealed significant relationships between soil health parameters, plant nutrient composition, and agronomic performance metrics. Corn yield was strongly correlated with Corn Ear Density (r = 0.85, p < 0.01) and Silage Yield (r = 0.88, p < 0.01), indicating that increased ear density and biomass production contributed to higher yields. Additionally, Corn Yield showed a moderate positive correlation with Soil Organic Carbon (r = 0.67, p < 0.05), suggesting that improved soil organic matter content may enhance crop productivity.

Soil health metrics were closely linked, with Soil Organic Carbon positively correlated with Soil Health Score (r = 0.79, p < 0.01) and Microbial Organic Carbon (r = 0.74, p < 0.01), highlighting the role of organic matter in supporting microbial activity. Additionally, CO₂ Soil Respiration, an indicator of microbial activity, exhibited a strong association with Microbial Organic Carbon (r = 0.71, p < 0.01), reinforcing the link between microbial biomass and respiration rates.

Plant nutrient uptake was significantly influenced by soil nutrient availability. Soil Zn correlated with Leaf Zn (r = 0.65, p < 0.05), while Soil P was positively associated with Leaf P (r = 0.69, p < 0.01), suggesting that soil phosphorus and zinc levels influenced plant tissue concentrations. Similarly, Soil K was highly correlated with Leaf K (r = 0.78, p < 0.01), indicating efficient potassium uptake from soil to plant tissues.

Nutrient availability also played a role in crop productivity. Silage Yield was moderately correlated with Soil P (r = 0.66, p < 0.05) and Soil Zn (r = 0.62, p < 0.05), suggesting that phosphorus and zinc contributed to biomass accumulation. Additionally, Grain Yield exhibited a moderate correlation with Soil Organic Carbon (r = 0.61, p < 0.05), supporting the notion that soil organic matter is beneficial for grain production.

Finally, treatment effects appeared to enhance microbial activity and nutrient uptake. Treated plots exhibited higher Soil Health Scores and Microbial Organic Carbon levels compared to untreated plots. These improvements were accompanied by increased soil respiration rates and greater nutrient uptake in leaf tissue, suggesting that the treatment promoted microbial interactions that enhanced soil fertility and plant growth. (

Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Correlation matrix of soil health, nutrient availability, and crop productivity.

Figure 3.

Correlation matrix of soil health, nutrient availability, and crop productivity.

This figure presents a correlation matrix illustrating the relationships between soil health metrics, nutrient availability, microbial activity, and crop productivity. The correlation values were calculated using Pearson’s correlation coefficient [

31] in Python [

32]. The matrix was visualized using Matplotlib [

30], with a color gradient indicating the strength and direction of correlations (warm colors for positive correlations and cool colors for negative correlations). Numeric correlation values were overlaid in each cell for clarity. The figure was generated and saved as an SVG file using a Python script.

Overall, the analysis highlights the interconnectedness of soil health, nutrient dynamics, and agronomic productivity; with microbial activity, organic carbon, and phosphorus emerging as key drivers of yield and plant nutrient status (

Figure 3,

Table 4)

3.5. Impact of environmental factors on soil health and productivity

Soil Health Score correlated with Microbial Organic Carbon (r = 0.91, p < 0.01) and CO₂ Soil Respiration (r = 0.87, p < 0.01). Soil Organic Carbon (LOI) correlated with Soil Health Score (r = 0.85, p < 0.01) and Microbial Organic Carbon (r = 0.82, p < 0.01). CO₂ Soil Respiration correlated with Microbial Organic Carbon (r = 0.92, p < 0.01).

Field Capacity correlated with Soil Health Score (r = 0.62, p < 0.05) and Total Nitrogen (r = 0.69, p < 0.05). Wilting Point showed negative correlations with Soil Organic Carbon (r = -0.55, p < 0.05) and Microbial Organic Carbon (r = -0.61, p < 0.05).

Corn Yield correlated with Soil Health Score (r = 0.74, p < 0.01) and Microbial Organic Carbon (r = 0.76, p < 0.01). Silage Yield correlated with Soil Health Score (r = 0.72, p < 0.01) and Soil Organic Carbon (r = 0.68, p < 0.05). Grain Yield correlated with Total Nitrogen (r = 0.81, p < 0.01).

Figure 4.

Correlation matrix of soil health and productivity indicators.

Figure 4.

Correlation matrix of soil health and productivity indicators.

This heatmap illustrates the Pearson correlation coefficients among key soil health, microbial activity, and crop productivity metrics in response to CFMI-8 treatment. Strong positive correlations (red) indicate closely associated variables, while negative correlations (blue) reflect inverse relationships. Key findings include strong correlations between Soil Health Score, Microbial Organic Carbon, and CO₂ Soil Respiration. The heatmap was generated using Matplotlib and Seaborn in Python [

33], with a structured approach that included data selection, statistical computation, and visualization. Key findings highlight the associations between Soil Health Score, Microbial Organic Carbon, and CO₂ Soil Respiration, illustrating the role of microbial activity in nutrient cycling and soil function.

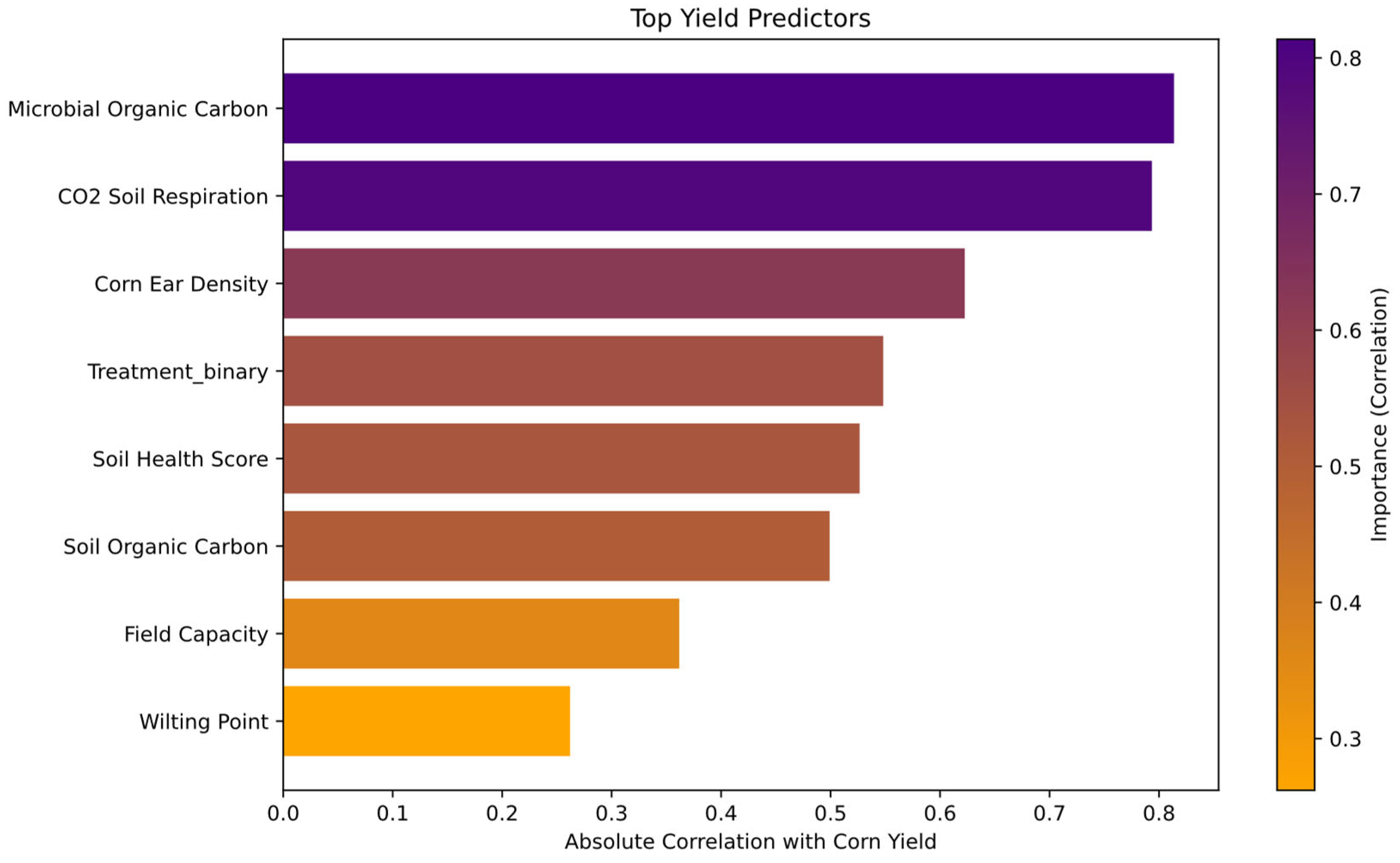

3.6. Random Foret analysis

3.6.1. Corn Yield Predictors

Random Forest analysis identified CO₂ Soil Respiration as the most important predictor of corn yield. Other top predictors included Microbial Organic Carbon, Total Nitrogen (Total-N), Nitrate Nitrogen (NO₃⁻-N), Field Capacity, Soil Health Score, and Soil Organic Carbon.

Figure 5 presents the ranked importance of these variables in the model..

This figure presents the most influential soil health and nutrient factors affecting corn yield, as identified through Random Forest analysis. The feature importance scores indicate the relative contribution of each factor, with Microbial Organic Carbon and CO₂ Soil Respiration, followed Corn Ear Density and Treatment with soil inoculant were the strongest predictors. This figure was created using Random Forest feature importance analysis, where the contribution of each soil health and nutrient factor to corn yield prediction was quantified and visualized as a bar plot. Bar plot was generated using Python, specifically utilizing the Scikit-Learn library [

34] for Random Forest modeling and permutation feature importance analysis, along with Matplotlib [

30]and Seaborn [

33] for visualization.

3.6.2. Micronutrient Uptake Predictors

Random Forest analysis identified CO₂ Soil Respiration as the most important predictor of leaf micronutrient uptake. Other key predictors included Microbial Organic Carbon, Nitrate Nitrogen (NO₃⁻-N), Ammonium Nitrogen (NH₄⁺-N), Field Capacity, and Soil pH.

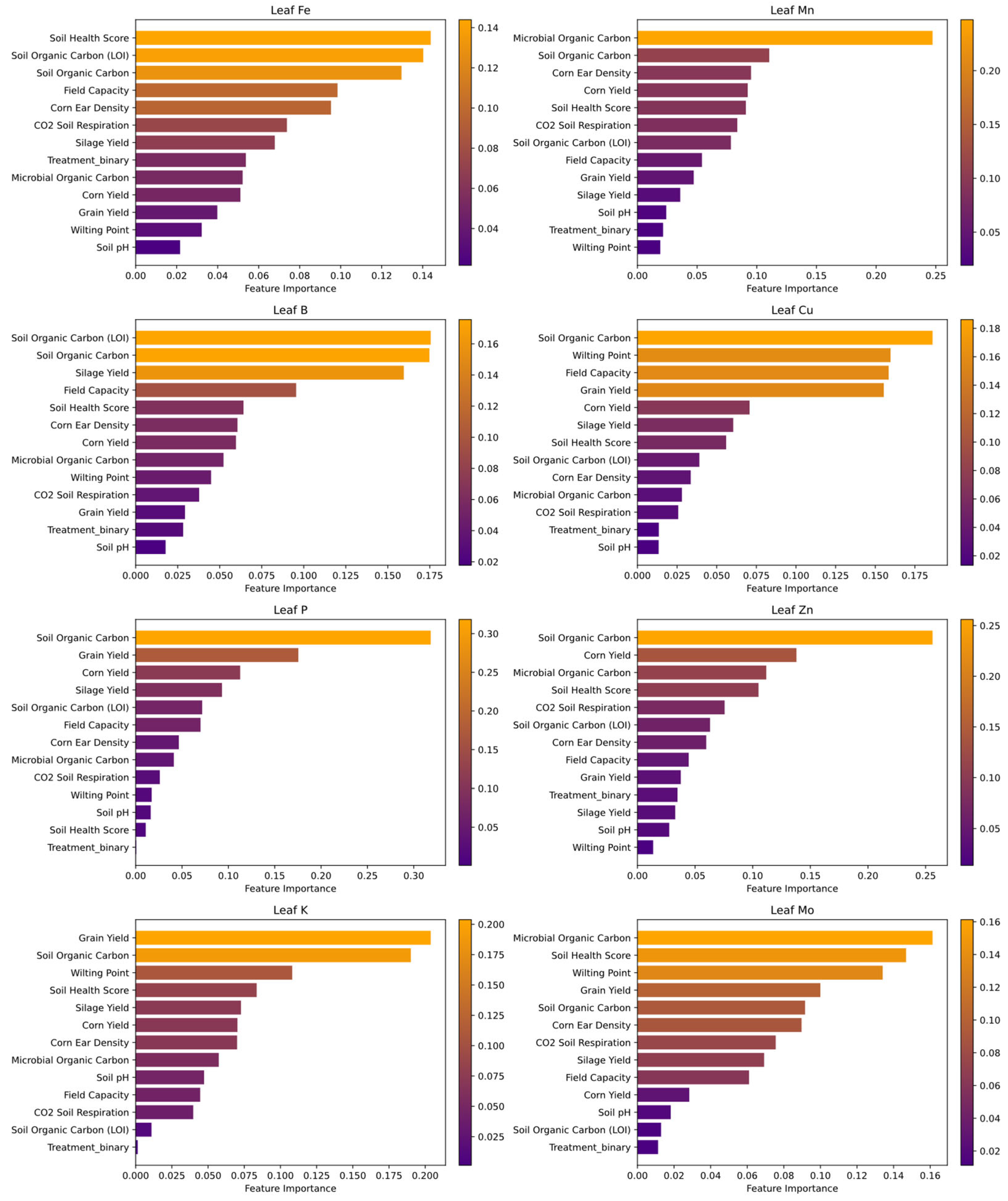

Figure 6 presents the ranked importance of these variables in the model.

This composite figure presents the feature importances for predicting micronutrient uptake (as measured by leaf nutrient concentrations) using a random forest model. Each subplot corresponds to one micronutrient—Leaf Fe, Leaf Mn, Leaf B, Leaf Cu, Leaf P, Leaf Zn, Leaf K, and Leaf Mo—where the horizontal bars represent the contribution of each predictor variable (e.g., yield components, soil properties, and treatment status). The color gradient, ranging from dark purple (indicating high importance) to light orange (indicating low importance), visualizes the normalized importance scores. Although the small sample size (n = 8) limits the statistical robustness, the analysis highlights which factors are most influential in predicting nutrient uptake and may serve as a basis for further investigation. Bar plots was generated using Python, specifically utilizing the Scikit-Learn library [

34] for Random Forest modeling and permutation feature importance analysis, along with Matplotlib [

30] and Seaborn [

33] for visualization. A summary of the key predictive variables and their relative importance is provided in Table 5.

4. Discussion

4.1. Soil Health Parameters

Application of the CFMI-8 treatment demonstrated significant improvements in multiple soil health parameters and supports its potential to enhance soil functionality and fertility (

Table 2). Treated soils exhibited higher soil health scores (13.26 vs. 8.79) and microbial organic carbon (80.48 mg/kg vs. 24.83 mg/kg) compared to untreated soils. These findings suggest that the treatment stimulated microbial activity and organic matter decomposition as evidenced by the elevated CO₂ soil respiration rates in treated soils (95.83 mg/kg/day vs. 35.88 mg/kg/day). Increased microbial activity is a key indicator of soil biological health since microbes play a crucial role in nutrient cycling and organic matter turnover [

35,

36]. Comparative results are illustrated in

Figure 1.

The higher nitrate nitrogen (NO

3-) levels in treated soils (38.15 mg/kg vs. 31.75 mg/kg) reflect enhanced nitrogen mineralization driven by increased microbial activity. This is consistent with the lower ammonium nitrogen (NH

4+) levels observed in treated soils (0.6 mg/kg vs. 1.68 mg/kg) and indicates efficient nitrification processes. Efficient nitrogen cycling is essential for plant growth; however, higher nitrate levels are also indicative of low Mo which is required for nitrate utilization as a cp-factor for nitrate and nitrite reductase enzymes [

37]. Most plants can use either form of nitrogen but may have a preference for one form or the other [

38]. The improvement in cation exchange capacity (CEC) in treated soils (8.78 meq/100g vs. 7.13 meq/100g) further supports CFMI-8 ’s role in enhancing soil fertility since CEC reflects the soil's ability to retain and supply essential cations such as potassium and calcium [

39].

Potassium levels were notably higher in treated soils (368.75 mg/kg vs. 289.75 mg/kg), suggesting improved nutrient retention and availability. Potassium is critical for plant physiological processes such as enzyme activation, water regulation, and stress tolerance [

37]. This increase may be attributed to enhanced microbial-mediated nutrient cycling and organic matter decomposition [

40]. The slightly higher organic matter content in treated soils, as indicated by LOI values (1.90% vs. 1.70%), also highlights the treatment's role in building soil organic carbon pools. Organic matter contributes to better soil structure, water retention, and microbial habitat that are all critical for sustainable agricultural productivity [

41].

Interestingly, untreated soils showed higher soil organic carbon (148.00 mg/kg vs. 118.00 mg/kg), which may be due to slower organic matter turnover in the absence of microbial treatment. While high organic carbon is generally favorable, its active utilization and conversion into available nutrients, as observed in treated soils, may be more beneficial for immediate crop productivity. The elevated microbial activity in treated soils suggests a more dynamic and functional soil system that is capable of sustaining plant growth and improving resilience against environmental stressors [

42].

Overall, the results indicate that treatment with CFMI-8 improved soil health by enhancing biological activity, nutrient cycling, and nutrient retention, as reflected in the higher soil health scores and functional metrics. These findings align with previous studies highlighting the importance of microbial inoculants and organic amendments in improving soil quality and productivity [

43,

44]. Further long-term studies are recommended to evaluate the sustained impact of this treatment on soil health and crop yield, as well as its potential to mitigate soil degradation in intensive agricultural systems.

4.2. Agronomic Results

The agronomic data demonstrate the clear benefits of treatment with CFMI-8 on crop productivity and quality that can be linked to the observed improvements in soil health metrics. Corn yield in the treated group was 28.6% higher than in the untreated group, and silage yield increased 9.6% to highlight the treatment's effectiveness in enhancing biomass production. These gains are likely driven by the improved nutrient availability and soil biological activity seen in the soil health data. For instance, the treated soils exhibited significantly higher nitrate nitrogen (NO

3-) levels (20.2% increase) and cation exchange capacity (CEC, 23.1% increase), suggesting better nutrient cycling and retention that directly support plant growth and development [

37,

39]. Additionally, the substantial increases in microbial organic carbon (224.1%) and CO₂ soil respiration (167.1%) indicate enhanced microbial activity, which would have contributed to more efficient nutrient cycling and organic matter breakdown, providing the crops with an improved nutrient supply [

45,

46].

Improved soil health metrics likely contributed to the observed increases in corn ear density (17.6%) and silage milk production (9.3% per acre, 2.8% per ton) in treated plots. Enhanced nutrient availability, facilitated by better nitrogen cycling and potassium levels (27.3% increase), supported robust plant growth and higher yields [

38,

47]. Moreover, the modest reduction in soil organic carbon in treated soils suggests that the enhanced microbial activity led to the active utilization of carbon for metabolic processes that drive nutrient cycling and crop productivity [

41].

The agronomic benefits observed in the CFMI-8 treated group can be directly correlated with improvements in soil health metrics. These findings highlight the treatment's potential to sustainably enhance crop productivity by creating a healthier, more biologically active soil ecosystem that supports nutrient cycling and plant growth.

4.3. Micronutrients analysis

The observed increase in leaf micronutrient concentrations of Fe, Mn, B, Zn, and Mo, highlights the efficacy of the applied treatment in improving nutrient uptake and bioavailability. Fe and Mn are critical for photosynthesis and electron transport, as they are integral to chlorophyll synthesis and enzymatic reactions. Previous studies have shown that enhanced Fe availability is directly correlated with improved plant vigor and photosynthetic efficiency [

48,

49]. Similarly, Mn has been linked to nitrogen assimilation and stress tolerance, consistent with the findings of increased Mn levels in treated plants [

50,

51,

52].

The significant increase in B and Zn concentrations is consistent with their roles in cell wall membrane structure and enzymatic activity, respectively. Boron deficiency is known to impair membrane stability and reproductive development in plants, so higher B levels in treated samples could improve structural integrity and reproductive outcomes [

53,

54,

55]. Zinc, a cofactor for numerous enzymes, is essential for protein synthesis and metabolic processes. Its increased availability in the treated plants suggests enhanced enzymatic activity, which is critical for overall growth and development [

56,

57].

The treatment’s effect on Mo is particularly noteworthy since Mo is vital for nitrogen metabolism and the functioning of nitrate reductase enzymes [

58,

59]. Elevated Mo levels in the CFMI-8 treated group indicate potential benefits for nitrogen utilization and soil health. This has been previously reported in studies with nutrient-enriched fertilizers [

60,

61].

While the treatment showed significant improvements in the concentrations of several micronutrients, it had no statistically significant impact on P or Cu levels. This could be due to inherent differences in nutrient mobility or plant-specific uptake mechanisms. Copper, while essential for enzymatic reactions, often requires chelation or soil amendments to enhance its bioavailability. These factors may not have been fully addressed by the treatment applied here [

62,

63]. Phosphorus, being relatively immobile in soil, often requires specific conditions for uptake, which might explain the lack of significant change [

64,

65].

The marginal increase in K, although not statistically significant, suggests that the CFMI-8 treatment may still contribute to improving water regulation and enzymatic activation. Potassium’s role in stomatal function and drought resistance highlights its importance even with small changes in concentration [

66,

67].

Overall, these findings are consistent with previous research showing the benefits of targeted treatments for enhancing micronutrient uptake in plants. The improvements in Fe, Mn, B, Zn, and Mo concentrations underscore CFMI-8 ’s potential to optimize plant metabolic processes and growth. Future studies should explore the long-term implications of these enhancements on crop yield and soil sustainability, as well as investigate the mechanisms underlying it’s selective impact on certain nutrients [

68,

69,

70].

The micronutrient data further reinforces the effectiveness of CFMI-8 in improving overall soil health, nutrient dynamics, and crop productivity. Treated soils contained higher levels of essential micronutrients such as manganese

(+60.0%), boron

(+50.0%), and molybdenum

(+52.2%), which have critical roles in plant metabolic processes, enzyme activation, and nitrogen cycling [

37]. These increases directly correlate with the improved availability and uptake of nutrients observed in treated leaves, where significant gains were noted in boron (+19.7%), copper (+17.5%), manganese (+11.7%), and iron (+9.7%). Enhanced micronutrient availability in the soil likely contributed to the improved agronomic performance metrics, including a 28.6 % higher corn yield and 9.6 % higher silage yield) than the untreated control.

The significant 8.1% increase in leaf phosphorus and 18.9% increase in soil phosphorus underscores the treatment's ability to enhance phosphorus availability, an essential nutrient for energy transfer, root development, and over-all crop productivity (Drinkwater & Snapp, 2007). This increase aligns with higher grain yield (+4.6%) in the treated group, as phosphorus is critical for seed formation. Similarly, the rise in zinc levels in both leaf (+3.3%) and soil (+29.6%) demonstrates improved micronutrient cycling which is essential for protein synthesis and plant stress tolerance (Alloway, 2008).

The modest reduction in soil potassium (-18.2%) is likely attributable to increased plant uptake, as evidenced by slightly elevated leaf potassium levels (+3.1%) in the CFMI-8 treated group. Potassium is vital for water regulation, photosynthesis, and plant resilience, which may have contributed to the 17.6% improved corn ear density observed in treated plots [

37]. CFMI-8 ’s enhancement of molybdenum availability, reflected in both soil (+52.2%) and leaf (+16.1%) levels, suggests better nitrogen metabolism, which also is observed with the higher nitrate nitrogen levels (+20.2%) in treated soils. This improved nitrogen availability is probably from stimulated nitrification and is available to support robust plant growth and biomass production.

CFMI-8 significantly enhanced soil fertility and nutrient availability, as demonstrated by increases in key micronutrients in both soil and leaf tissues. These improvements correlate strongly with enhanced agronomic performance reflected in higher yields and better silage quality. The ability of CFMI-8 to enhance microbial activity in soil and improve nutrient cycling underscores its potential as a sustainable solution for boosting soil health and crop productivity.

4.4. Soil Health, Microbial Activity, and Crop Productivity

The results in

Figure 3 highlight the complex interactions between soil health, microbial activity, and crop productivity. The strong correlation between Corn Yield and Corn Ear Density suggests that management strategies that improve ear density—such as optimizing planting density, fertilization, and soil health—can directly enhance yield outcomes [

71].

The relationship between Soil Organic Carbon, Soil Health Score, and Microbial Organic Carbon underscores the importance of organic matter in supporting soil microbiota [

72]. This suggests that treatments aimed at increasing organic matter inputs (e.g., compost, microbial inoculants) could improve both microbial activity and soil structure, ultimately leading to higher yields.

Nutrient uptake efficiency, particularly for potassium, phosphorus, and zinc, appears to play a crucial role in crop productivity [

73]. The correlation between Soil P and Silage Yield suggests that phosphorus availability is a limiting factor for biomass accumulation [

74,

75]. Additionally, the link between Soil Zn and Silage Yield implies that zinc, often overlooked in standard fertilization programs, could be a key micronutrient in optimizing plant growth [

76,

77].

The treatment effects suggest that enhancing soil microbial interactions can improve nutrient cycling and crop performance [

78,

79]. This is evidenced by the higher soil respiration and microbial organic carbon levels in treated plots, which indicate a more active microbial community likely contributing to better soil structure and nutrient availability [

80,

81].

Overall, these findings reinforce the idea that soil health interventions, particularly those focused on microbial activity and organic matter management, can improve nutrient cycling and increase yield potential [

82]. Future work should further investigate the causal mechanisms behind these correlations, including controlled trials with different soil amendments and microbial inoculants to optimize soil-plant interactions.

4.5. Soil Health and Fertility

The results summarized in

Figure 4 indicate that CFMI-8 treatment enhances microbial activity, leading to improvements in soil health and fertility. The strong correlations between Soil Health Score, Microbial Organic Carbon, and CO₂ Respiration suggest that increased microbial biomass and metabolic activity contribute to better soil function [

83]. The positive relationship between Soil Organic Carbon and Microbial Organic Carbon highlights the importance of organic matter in maintaining microbial communities, which play a key role in nutrient cycling [

84].

The relationship between Field Capacity and Soil Health Score suggests that improved soil moisture retention may promote microbial activity and nutrient availability [

85,

86]. The negative correlation between Wilting Point and Soil Organic Carbon indicates that organic-rich soils not only hold water more effectively but also facilitate microbial access to moisture, further supporting plant-microbe interactions [

87,

88].

The positive correlations between Corn Yield, Silage Yield, and Soil Health Score emphasize the role of microbial-driven soil improvements in enhancing productivity [

6]. The strong association between Grain Yield and Total Nitrogen aligns with previous findings that nitrogen availability is a key determinant of grain production. These results suggest that CFMI-8 treatment improves soil microbial function, water retention, and nutrient cycling, leading to enhanced crop productivity. Future studies should assess the long-term impacts of these improvements on soil sustainability and yield stability.

4.6. Random Forest Analysis and Predictive Metrics

The Random Forest analysis identified key soil health and nutrient factors influencing corn yield (

Figure 5) and micronutrient uptake (

Figure 6), emphasizing the importance of microbial activity and nitrogen availability in soil fertility and crop productivity.

4.7. Corn Yield Predictors

As shown in

Figure 5, nitrate (NO₃-N) emerged as the strongest predictor of corn yield, indicating that nitrogen availability plays a critical role in biomass accumulation and grain development. This aligns with previous studies showing that nitrogen is a primary limiting factor in crop production [

73,

89].

Microbial Organic Carbon also showed high predictive power, reinforcing the importance of soil microbial activity in nutrient cycling. This finding is consistent with previous reports that increased microbial biomass enhances organic matter decomposition and nutrient availability, contributing to higher crop productivity [

90,

91]. Additionally, CO₂ soil respiration was a strong predictor, highlighting microbial-driven carbon cycling as a key factor for soil health and fertility [

92].

Other influential predictors include Soil Organic Carbon (LOI), Soil pH, and Soil Health Score, which collectively indicate that nutrient retention, microbial balance, and soil structure are major drivers of agronomic performance. These results support previous findings that maintaining high organic matter and microbial diversity enhances nutrient availability and plant growth [

45,

93].

4.8. Micronutrient Uptake Predictors

Our analysis of micronutrient uptake using random forest regression revealed that both agronomic management and inherent crop performance play critical roles in nutrient assimilation (

Figure 6). Notably, the treatment variable—distinguishing between managed (treated) and unmanaged (untreated) plots—and corn ear density consistently emerged as strong predictors. This indicates that the implementation of specific management practices, along with maintaining optimal plant density, may substantially enhance the efficiency of micronutrient uptake by influencing overall plant vigor and root development.

In addition, yield components such as grain yield and silage yield were significant predictors of micronutrient uptake. The strong association between these yield parameters and leaf nutrient concentrations suggests that higher crop productivity is linked to improved nutrient assimilation. Vigorous plants, which contribute to higher yields, likely develop more extensive and efficient root systems, thereby enhancing their ability to absorb and translocate essential micronutrients.

Soil quality indicators, including soil organic carbon and soil health score, were moderately important in predicting micronutrient uptake, underscoring the role of soil organic matter in nutrient availability. Healthy soils not only support robust microbial activity and nutrient cycling but also indirectly facilitate nutrient uptake by crops. Although variables such as soil pH, field capacity, and wilting point were included in the analysis, their lower importance suggests that their influence on micronutrient uptake is less direct compared to management practices and yield components. Overall, while the limited sample size constrains the generalizability of these findings, the analysis provides valuable preliminary insights that warrant further investigation with larger datasets.

For leaf micronutrient uptake, CO₂ soil respiration was again the most influential factor (

Figure 6), suggesting that microbial activity enhances nutrient solubilization and root absorption efficiency [

94]. Microbial Organic Carbon also contributed significantly, reinforcing the role of microbial interactions in nutrient exchange and plant-microbe symbiosis [

43]

4.9. Limitations of the Study

This study demonstrates the efficacy of CFMI-8 in enhancing soil health, nutrient availability, and crop productivity; however, several limitations should be considered. The findings are based on a single-season trial, limiting insights into long-term soil health improvements and microbial succession, necessitating multi-year studies. Additionally, the study was conducted under site-specific conditions at Findlay Farm, Whitewater, WI, and may not be fully generalizable to other environments with different soil and climatic factors. While CO₂ respiration and microbial organic carbon were measured as indicators of microbial activity, a detailed microbial community analysis was not performed, leaving gaps in understanding how CFMI-8 influences soil microbiome composition. Furthermore, the study did not include a cost-benefit analysis to assess the economic viability of CFMI-8 use at scale. Lastly, potential interactions between CFMI-8 and other soil amendments such as fertilizers, compost, or cover crops were not explored, which could impact its effectiveness in different agronomic systems. Despite these limitations, the results provide strong support for the role of microbial inoculants in sustainable agriculture, highlighting the need for further research into their long-term soil regeneration and productivity benefits.

5. Conclusions

This study demonstrates that CFMI-8 , a microbial soil inoculant, significantly enhances soil health, nutrient availability, and crop productivity, supporting its potential as a sustainable agricultural intervention. Treated soils exhibited increased microbial activity, as evidenced by higher microbial organic carbon (+224.1%) and CO₂ soil respiration (+167.1%), indicating improved nutrient cycling and organic matter decomposition. These changes contributed to enhanced nitrate nitrogen (NO₃-N) availability (+20.2%), which played a key role in boosting corn yield (+28.6%) and silage production (+9.6%).

The increase in leaf micronutrient concentrations (Fe, Mn, Zn, B) suggests that CFMI-8 improves nutrient uptake efficiency, likely due to its positive effects on soil microbial interactions and nutrient solubilization. Random Forest analysis identified NO₃-N, microbial organic carbon, and CO₂ respiration as the top predictors of corn yield, reinforcing the critical role of microbial-driven processes in soil fertility.

These findings highlight the potential of microbial inoculants as regenerative tools for enhancing soil health, mitigating nutrient deficiencies, and increasing crop resilience. Future research should explore long-term impacts, multi-season trials, and interactions with different soil types and crop varieties to optimize the application of CFMI-8 in large-scale agricultural systems.

This study contributes to the growing body of evidence supporting microbial-based solutions for sustainable soil management and resilient food production.

Author Contributions

R.C., D.M.H., and M.C, conceived and designed the experiments. J.D. and D.H. collected the samples. J.D. performed the laboratory work and R.C. drafted the manuscript. D.M.H., J.D., D.H., and M.C. revised the manuscript. All authors read and 1547 approved the final manuscript.

Funding

Funding was provided by GLK-Sauerkraut, Madison, WI, USA.

Conflicts of Interest

R.C. and M.C. acknowledge a potential conflict of interest as principals of Ancient Organics Bioscience, Inc., the company that developed the CFMI-8 microbial inoculant used in this study. To maintain research integrity and objectivity, all aspects of soil preparation, inoculant application, sample collection, and data generation were conducted by independent third parties. These measures were implemented to minimize bias and ensure an objective assessment of the product’s performance. The remaining authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no involvement in the development or application of the microbial inoculant, soil preparation, the design of the sampling protocol, sample collection, or data generation.

References

- Wei, X.; Xie, B.; Wan, C.; Song, R.; Zhong, W.; Xin, S.; Song, K. Enhancing soil health and plant growth through microbial fertilizers: Mechanisms, benefits, and sustainable agricultural practices. Agronomy 2024, 14, 609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Shammary, A.A.G.; Al-Shihmani, L.S.S.; Fernández-Gálvez, J.; Caballero-Calvo, A. Optimizing sustainable agriculture: A comprehensive review of agronomic practices and their impacts on soil attributes. Journal of Environmental Management 2024, 364, 121487. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lal, R. Restoring soil quality to mitigate soil degradation. Sustainability 2015, 7, 5875–5895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedrinho, A.; Mendes, L.W.; de Araujo Pereira, A.P.; Araujo, A.S.F.; Vaishnav, A.; Karpouzas, D.G.; Singh, B.K. Soil microbial diversity plays an important role in resisting and restoring degraded ecosystems. Plant and Soil 2024, 1–25. [Google Scholar]

- Coban, O.; De Deyn, G.B.; van der Ploeg, M. Soil microbiota as game-changers in restoration of degraded lands. Science 2022, 375, abe0725. [Google Scholar]

- Islam, W.; Zeng, F.; Alotaibi, M.O.; Khan, K.A. Unlocking the potential of soil microbes for sustainable desertification management. Earth-Science Reviews 2024, 104738. [Google Scholar]

- Li, C.; Chen, X.; Jia, Z.; Zhai, L.; Zhang, B.; Grüters, U.; Ma, S.; Qian, J.; Liu, X.; Zhang, J. Meta-analysis reveals the effects of microbial inoculants on the biomass and diversity of soil microbial communities. Nature Ecology & Evolution 2024, 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Upadhayay, V.K.; de los Santos Villalobos, S.; Aravindharajan, S.; Kukreti, B.; Chitara, M.K.; Jaggi, V.; Sharma, A.; Singh, A.V. Microbial Advancement in Agriculture. In Microbial Inoculants: Applications for Sustainable Agriculture; Springer, 2024; pp. 95–125. [Google Scholar]

- O'Callaghan, M.; Ballard, R.A.; Wright, D. Soil microbial inoculants for sustainable agriculture: Limitations and opportunities. Soil Use and Management 2022, 38, 1340–1369. [Google Scholar]

- Heirendt, L.; Arreckx, S.; Pfau, T.; Mendoza, S.N.; Richelle, A.; Heinken, A.; Haraldsdóttir, H.S.; Wachowiak, J.; Keating, S.M.; Vlasov, V. Creation and analysis of biochemical constraint-based models using the COBRA Toolbox v. 3.0. Nature protocols 2019, 14, 639–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arkin, A.P.; Cottingham, R.W.; Henry, C.S.; Harris, N.L.; Stevens, R.L.; Maslov, S.; Dehal, P.; Ware, D.; Perez, F.; Canon, S. KBase: the United States department of energy systems biology knowledgebase. Nature biotechnology 2018, 36, 566–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samantaray, A.; Chattaraj, S.; Mitra, D.; Ganguly, A.; Kumar, R.; Gaur, A.; Mohapatra, P.K.D.; de los Santos-Villalobos, S.; Rani, A.; Thatoi, H. Advances in microbial based bio-inoculum for amelioration of soil health and sustainable crop production. Current Research in Microbial Sciences 2024, 100251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kapoor, D.; Sharma, P.; Sharma, M.M.M.; Yadav, S.; Husen, A. Exploring soil microbiota and their role in plant growth, stress tolerance, disease control and nutrient immobilizer. Biocatalysis and Agricultural Biotechnology 2024, 103358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visca, A.; Di Gregorio, L.; Clagnan, E.; Bevivino, A. Sustainable strategies: Nature-based solutions to tackle antibiotic resistance gene proliferation and improve agricultural productivity and soil quality. Environmental Research 2024, 118395. [Google Scholar]

- de Jesus Cano, R.; Daniels, J.M.; Carlin, M.; Huber, D.M. Microbial Approach to Sustainable Cotton Agriculture: The Role of CFMI-8 ® in Soil Health and Glyphosate Mitigation. 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, M.T.; Aleinikovienė, J.; Butkevičienė, L.-M. Innovative organic fertilizers and cover crops: Perspectives for sustainable agriculture in the era of climate change and organic agriculture. Agronomy 2024, 14, 2871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MERİÇ, Ç.S. A Step Beyond Prebiotics and Probiotics:“Postbiotics” Composition, Activities and Effects on Health. Current Debates in Health Sciences 55.

- Sokal, R.R. A statistical method for evaluating systematic relationships. Univ. Kansas, Sci. Bull. 1958, 38, 1409–1438. [Google Scholar]

- Haney, R.L.; Haney, E.B.; Smith, D.R.; Harmel, R.D.; White, M.J. The soil health tool—Theory and initial broad-scale application. Applied soil ecology 2018, 125, 162–168. [Google Scholar]

- Undersander, D.; Mertens, D.; Thiex, N. Forage analyses. Information Systems Division, National Agricultural Library (United States of America) NAL/USDA 1993, 10301. [Google Scholar]

- Shenk, J.; Westerhaus, M. The application of near infrared reflectance spectroscopy (NIRS) to forage analysis. Forage quality, evaluation, and utilization 1994, 406–449. [Google Scholar]

- Jones Jr, J.B.; Case, V.W. Sampling, handling, and analyzing plant tissue samples. Soil testing and plant analysis 1990, 3, 389–427. [Google Scholar]

- Team, R.C. A language and environment for statistical computing. (No Title) 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Flynn, M.R. Analysis of censored exposure data by constrained maximization of the Shapiro–Wilk W statistic. Annals of occupational hygiene 2010, 54, 263–271. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Liaw, A.; Wiener, M. Classification and regression by random. Forest. R News 2002, 2(3), 18–22. [Google Scholar]

- Han, H.; Guo, X.; Yu, H. Variable selection using mean decrease accuracy and mean decrease gini based on random forest. In Proceedings of the 2016 7th ieee international conference on software engineering and service science (icsess); 2016; pp. 219–224. [Google Scholar]

- Tatachar, A.V. Comparative assessment of regression models based on model evaluation metrics. International Research Journal of Engineering and Technology (IRJET) 2021, 8, 2395–0056. [Google Scholar]

- Villanueva, R.A.M.; Chen, Z.J. ggplot2: elegant graphics for data analysis. 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Kuhn, M. Building predictive models in R using the caret package. Journal of statistical software 2008, 28, 1–26. [Google Scholar]

- Hunter, J.D. Matplotlib: A 2D graphics environment. Computing in science & engineering 2007, 9, 90–95. [Google Scholar]

- Wickens, T.D.; Keppel, G. Design and analysis: A researcher's handbook; Pearson Prentice-Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- José, U. Python programming for data analysis; Springer, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Waskom, M.L. Seaborn: statistical data visualization. Journal of Open Source Software 2021, 6, 3021. [Google Scholar]

- Pedregosa, F.; Varoquaux, G.; Gramfort, A.; Michel, V.; Thirion, B.; Grisel, O.; Blondel, M.; Prettenhofer, P.; Weiss, R.; Dubourg, V. Scikit-learn: Machine learning in Python. the Journal of machine Learning research 2011, 12, 2825–2830. [Google Scholar]

- Weng, Z.; Lehmann, J.; Van Zwieten, L.; Joseph, S.; Archanjo, B.S.; Cowie, B.; Thomsen, L.; Tobin, M.J.; Vongsvivut, J.; Klein, A. Probing the nature of soil organic matter. Critical Reviews in Environmental Science and Technology 2022, 52, 4072–4093. [Google Scholar]

- Carvalho, M.L.; Maciel, V.F.; Bordonal, R.d.O.; Carvalho, J.L.N.; Ferreira, T.O.; Cerri, C.E.P.; Cherubin, M.R. Stabilization of organic matter in soils: drivers, mechanisms, and analytical tools–a literature review. Revista Brasileira de Ciência do Solo 2023, 47, e0230130. [Google Scholar]

- Marschner, H. Marschner's mineral nutrition of higher plants. Plants 2012, 89, 315–330. [Google Scholar]

- Drinkwater, L.E.; Snapp, S.S. Advancing the science and practice of ecological nutrient management for smallholder farmers. Frontiers in Sustainable Food Systems 2022, 6, 921216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brady, N.C.; Weil, R.R.; Weil, R.R. The nature and properties of soils; Prentice Hall Upper: Saddle River, NJ, 2008; Volume 13. [Google Scholar]

- Reardon, C.; Gollany, H.; Wuest, S. Diazotroph community structure and abundance in wheat–fallow and wheat–pea crop rotations. Soil Biology and Biochemistry 2014, 69, 406–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lal, R. Soil carbon sequestration impacts on global climate change and food security. science 2004, 304, 1623–1627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tisdall, J.M.; Oades, J.M. Organic matter and water-stable aggregates in soils. Journal of soil science 1982, 33, 141–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bender, S.F.; Wagg, C.; van der Heijden, M.G. An underground revolution: biodiversity and soil ecological engineering for agricultural sustainability. Trends in ecology & evolution 2016, 31, 440–452. [Google Scholar]

- Lazcano, C.; Domínguez, J. The use of vermicompost in sustainable agriculture: impact on plant growth and soil fertility. Soil nutrients 2011, 10, 187. [Google Scholar]

- Lehmann, J.; Kleber, M. The contentious nature of soil organic matter. Nature 2015, 528, 60–68. [Google Scholar]

- Six, J.; Conant, R.T.; Paul, E.A.; Paustian, K. Stabilization mechanisms of soil organic matter: implications for C-saturation of soils. Plant and soil 2002, 241, 155–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drinkwater, L.E.; Snapp, S. Nutrients in agroecosystems: rethinking the management paradigm. Advances in agronomy 2007, 92, 163–186. [Google Scholar]

- Ali, Q.; Ali, S.; El-Esawi, M.A.; Rizwan, M.; Azeem, M.; Hussain, A.I.; Perveen, R.; El-Sheikh, M.A.; Alyemeni, M.N.; Wijaya, L. Foliar spray of Fe-Asp confers better drought tolerance in sunflower as compared with FeSO4: Yield traits, osmotic adjustment, and antioxidative defense mechanisms. Biomolecules 2020, 10, 1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, R.; Zhang, W.; Kang, Y.; Shi, M.; Yang, X.; Li, H.; Yu, H.; Wang, Y.; Qin, S. Application of different foliar iron fertilizers for improving the photosynthesis and tuber quality of potato (Solanum tuberosum L.) and enhancing iron biofortification. Chemical and Biological Technologies in Agriculture 2022, 9, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huber, D.; Wilhelm, N. The role of manganese in resistance to plant diseases. In Proceedings of the Manganese in Soils and Plants: Proceedings of the International Symposium on ‘Manganese in Soils and Plants’ held at the Waite Agricultural Research Institute, The University of Adelaide, Glen Osmond, South Australia, August 22–26; 1988 as an Australian Bicentennial Event. 1988; pp. 155–173. [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt, S.B.; Husted, S. The biochemical properties of manganese in plants. Plants 2019, 8, 381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rai, S.; Singh, P.K.; Mankotia, S.; Swain, J.; Satbhai, S.B. Iron homeostasis in plants and its crosstalk with copper, zinc, and manganese. Plant Stress 2021, 1, 100008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wimmer, M.A.; Goldberg, S.; Gupta, U.C. 8 Boron. Handbook of plant nutrition 2015, 305. [Google Scholar]

- Rasheed, M.K. Role of boron in plant growth: a review. Journal of agricultural research 2009, 47, 329–338. [Google Scholar]

- Haque, M.A. Boron Impact on Maize Growth and Yield: A Review. International Journal of Plant & Soil Science 2024, 36, 353–363. [Google Scholar]

- Rudani, K.; Vishal, P.; Kalavati, P. The importance of zinc in plant growth-A review. Int. Res. J. Nat. Appl. Sci 2018, 5, 38–48. [Google Scholar]

- Hamzah Saleem, M.; Usman, K.; Rizwan, M.; Al Jabri, H.; Alsafran, M. Functions and strategies for enhancing zinc availability in plants for sustainable agriculture. Frontiers in Plant Science 2022, 13, 1033092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmer, W.; Mendel, R. Molybdenum metabolism in plants. Plant biology 1999, 1, 160–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tokasheva, D.; Nurbekova, Z.A.; Akbassova, A.Z.; Omarov, R. Molybdoenzyme participation in plant biochemical processes. Eurasian Journal of Applied Biotechnology 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaiser, B.N.; Gridley, K.L.; Ngaire Brady, J.; Phillips, T.; Tyerman, S.D. The role of molybdenum in agricultural plant production. Annals of botany 2005, 96, 745–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomas, C.L.; Darch, T.; Harris, P.; Beaumont, D.A.; Haefele, S.M. The Distribution of Soil Micro-Nutrients and the Effects on Herbage Micro-Nutrient Uptake and Yield in Three Different Pasture Systems. Agronomy 2021, 11, 1731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, V.; Pandita, S.; Sidhu, G.P.S.; Sharma, A.; Khanna, K.; Kaur, P.; Bali, A.S.; Setia, R. Copper bioavailability, uptake, toxicity and tolerance in plants: A comprehensive review. Chemosphere 2021, 262, 127810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mir, A.R.; Pichtel, J.; Hayat, S. Copper: uptake, toxicity and tolerance in plants and management of Cu-contaminated soil. Biometals 2021, 34, 737–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lizcano-Toledo, R.; Reyes-Martín, M.P.; Celi, L.; Fernández-Ondoño, E. Phosphorus dynamics in the soil–plant–environment relationship in cropping systems: A review. Applied Sciences 2021, 11, 11133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amadou, I.; Houben, D.; Faucon, M.-P. Unravelling the role of rhizosphere microbiome and root traits in organic phosphorus mobilization for sustainable phosphorus fertilization. A review. Agronomy 2021, 11, 2267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sardans, J.; Peñuelas, J. Potassium control of plant functions: Ecological and agricultural implications. Plants 2021, 10, 419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Zheng, Q.; Shen, Q.; Guo, S. The critical role of potassium in plant stress response. International journal of molecular sciences 2013, 14, 7370–7390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fageria, V. Nutrient interactions in crop plants. Journal of plant nutrition 2001, 24, 1269–1290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alloway, B.J. Micronutrients and crop production: An introduction. In Micronutrient deficiencies in global crop production; Springer, 2008; pp. 1–39. [Google Scholar]

- Rahman, R.; Sofi, J.A.; Javeed, I.; Malik, T.H.; Nisar, S. Role of micronutrients in crop production. International Journal of Current Microbiology and Applied Sciences 2020, 8, 2265–2287. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, P.; Zhang, Q.; Shuai, X.; Pan, J.; Zhang, W.; Shi, J.; Wang, M.; Chen, X.; Cui, Z. Interaction between plant density and nitrogen management strategy in improving maize grain yield and nitrogen use efficiency on the North China Plain. The Journal of Agricultural Science 2016, 154, 978–988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonanomi, G.; Lorito, M.; Vinale, F.; Woo, S.L. Organic amendments, beneficial microbes, and soil microbiota: toward a unified framework for disease suppression. Annual Review of Phytopathology 2018, 56, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Fageria, N.; Baligar, V.; Li, Y. The role of nutrient efficient plants in improving crop yields in the twenty first century. Journal of plant nutrition 2008, 31, 1121–1157. [Google Scholar]

- Davidson, E.A.; Reis de Carvalho, C.J.; Vieira, I.C.; Figueiredo, R.d.O.; Moutinho, P.; Yoko Ishida, F.; Primo dos Santos, M.T.; Benito Guerrero, J.; Kalif, K.; Tuma Sabá, R. Nitrogen and phosphorus limitation of biomass growth in a tropical secondary forest. Ecological applications 2004, 14, 150–163. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.; Zhang, H.; Cao, D.; Wu, C.; Wang, X.; Wei, L.; Guo, B.; Wang, S.; Ding, J.; Chen, H. Microbial carbon and phosphorus metabolism regulated by C: N: P stoichiometry stimulates organic carbon accumulation in agricultural soils. Soil and Tillage Research 2024, 242, 106152. [Google Scholar]

- Nadeem, F.; Abbas, S.; Waseem, F.; Ali, N.; Mahmood, R.; Bibi, S.; Deng, L.; Wang, R.; Zhong, Y.; Li, X. Phosphorus (P) and Zinc (Zn) nutrition constraints: A perspective of linking soil application with plant regulations. Environmental and Experimental Botany 2024, 105875. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed, N.; Zhang, B.; Chachar, Z.; Li, J.; Xiao, G.; Wang, Q.; Hayat, F.; Deng, L.; Bozdar, B.; Tu, P. Micronutrients and their effects on horticultural crop quality, productivity and sustainability. Scientia Horticulturae 2024, 323, 112512. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, L.; Gao, Y.; Yang, W.; Liu, J.; Wang, Z. Community metagenomics reveals the processes of nutrient cycling regulated by microbial functions in soils with P fertilizer input. Plant and Soil 2024, 499, 139–154. [Google Scholar]

- Bhattacharyya, S.S.; Furtak, K. Soil–Plant–Microbe interactions determine soil biological fertility by altering rhizospheric nutrient cycling and biocrust formation. Sustainability 2022, 15, 625. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, R.; Qu, Z.; Liu, L.; Yang, W.; Wang, L.; Li, J.; Zhang, D. Soil respiration and organic carbon response to biochar and their influencing factors. Atmosphere 2022, 13, 2038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- San Román, A.X.; Srikanthan, N.; Hamid, A.A.; Muratore, T.J.; Knorr, M.A.; Frey, S.D.; Simpson, M.J. Long-term warming in a temperate forest accelerates soil organic matter decomposition despite increased plant-derived inputs. Biogeochemistry 2024, 167, 1159–1174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhtar, M.; Gulab, M.; Ghazanfar, M. Assessing Soil Health and Fertility through Microbial Analysis and Nutrient Profiling Implications for Sustainable Agriculture. Innovative Research in Applied, Biological and Chemical Sciences 2023, 1, 29–42. [Google Scholar]

- Liptzin, D.; Norris, C.E.; Cappellazzi, S.B.; Mac Bean, G.; Cope, M.; Greub, K.L.; Rieke, E.L.; Tracy, P.W.; Aberle, E.; Ashworth, A. An evaluation of carbon indicators of soil health in long-term agricultural experiments. Soil Biology and Biochemistry 2022, 172, 108708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharyya, S.S.; Ros, G.H.; Furtak, K.; Iqbal, H.M.; Parra-Saldívar, R. Soil carbon sequestration–An interplay between soil microbial community and soil organic matter dynamics. Science of The Total Environment 2022, 815, 152928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Zhang, H.; Deng, J.; Fu, L.; Chen, H.; Li, C.; Xu, L.; Jiao, J.; Zhang, S.; Wang, J. Cover crop by irrigation and fertilization improves soil health and maize yield: Establishing a soil health index. Applied Soil Ecology 2023, 182, 104727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sainju, U.M.; Liptzin, D.; Dangi, S.M. Enzyme activities as soil health indicators in relation to soil characteristics and crop production. Agrosystems, Geosciences & Environment 2022, 5, e20297. [Google Scholar]

- Liang, J.; Chen, K.; Siqintana; Huo, T.; Zhang, Y.; Jing, J.; Feng, W. Towards improved modeling of SOC decomposition: soil water potential beyond the wilting point. Global change biology 2022, 28, 3665–3673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mauget, S.A.; Himanshu, S.K.; Goebel, T.S.; Ale, S.; Lascano, R.J.; Gitz III, D.C. Soil and soil organic carbon effects on simulated Southern High Plains dryland Cotton production. Soil and Tillage Research 2021, 212, 105040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawkesford, M.J.; Cakmak, I.; Coskun, D.; De Kok, L.J.; Lambers, H.; Schjoerring, J.K.; White, P.J. Functions of macronutrients. In Marschner's mineral nutrition of plants; Elsevier, 2023; pp. 201–281. [Google Scholar]

- Schimel, J.P.; Schaeffer, S.M. Microbial control over carbon cycling in soil. Frontiers in microbiology 2012, 3, 348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Der Heijden, M.G.; Bardgett, R.D.; Van Straalen, N.M. The unseen majority: soil microbes as drivers of plant diversity and productivity in terrestrial ecosystems. Ecology letters 2008, 11, 296–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beattie, G.A.; Edlund, A.; Esiobu, N.; Gilbert, J.; Nicolaisen, M.H.; Jansson, J.K.; Jensen, P.; Keiluweit, M.; Lennon, J.T.; Martiny, J. Soil microbiome interventions for carbon sequestration and climate mitigation. mSystems 2024, e01129–01124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Delgado-Baquerizo, M.; Maestre, F.T.; Reich, P.B.; Jeffries, T.C.; Gaitan, J.J.; Encinar, D.; Berdugo, M.; Campbell, C.D.; Singh, B.K. Microbial diversity drives multifunctionality in terrestrial ecosystems. Nature communications 2016, 7, 10541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Richardson, A.E.; Lynch, J.P.; Ryan, P.R.; Delhaize, E.; Smith, F.A.; Smith, S.E.; Harvey, P.R.; Ryan, M.H.; Veneklaas, E.J.; Lambers, H. Plant and microbial strategies to improve the phosphorus efficiency of agriculture. Plant and soil 2011, 349, 121–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).