1. Introduction

The global aviation market, which had been stagnant due to COVID-19, is expected to experience a rapid recovery in passenger traffic following the declaration of the end of the COVID-19 emergency. According to the Sustainability and Economics, Tourism Economic Report by the International Air Transport Association (IATA), the number of air passengers in the Asia-Pacific region is projected to grow at an annual rate of 4.5%, surpassing 4 billion by 2040 (World Health Organization, 2023; International Air Transport Association, 2023). Likewise, Global demand for tourism, which gradually belongs among the largest and fastest growing economic sectors in the world, is growing along with the growth of living standards and globalization of national economies (Zýka & Děkan, 2017).

Improving the security and efficiency of airports is one of the most important strategic objectives of the International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO) and airports (Janssen et al., 2019). Against this backdrop, the recovery of air travel demand and the enhancement of competitiveness in the global aviation market are expected to revitalize the overall aviation industry. However, this resurgence is also accompanied by an increased risk of security threats, including terrorism.

The rapidly recovering global aviation industry following COVID-19 presents new opportunities while simultaneously facing various challenges. Consequently, security threats are becoming increasingly complex. Furthermore, the proliferation of terrorism and the diversification of attack methods necessitate enhanced response capabilities in airport security.

Recent concern over aviation security has focused interest on the role of airport security screeners in keeping weapons and other potential threats off aircraft (McCarley et al., 2004). Many real threats are captured nationwide: in 2018, for example, 4,239 firearms were found in carry-on bags, and more than 80% of these were loaded. These numbers have steadily grown in recent years as air traffic has continued to increase nationally (Liang et al., 2019).

However, it should not be overlooked that the development in technologies has been moving the invention of terrorists and it is, therefore, important to be ahead of terrorists in the way that they are not able to deceive (Zýka & Děkan, 2017).

These changes and emerging issues make the role of Airport security screening officers absolutely essential and even more critical. Airport security screening officers play a decisive role in responding to ever evolving threats while ensuring the safety of travelers and airport users.

To uphold the fundamental rights of air travelers while preventing security threats such as incidents involving live ammunition or bladed weapons, security screening officers must possess extensive expertise.

After the devastating September 11 attacks, airport security has changed considerably. More and more measures were implemented, making the airport a more secure place. At the same time, passenger numbers have increased significantly since then as well. With this increase in passenger numbers, as well as increased security measures per passenger, a large increase in costs occurred. Where the United States spent $2.2 billion on airport security in 2002, they spent almost $8 billion in 2013. About a quarter of the operating costs of an airport is allocated to security nowadays (Janssen et al., 2020).

The security of air travel is a significant focus of the aviation industry, and x-ray security screening is a key factor in guaranteeing this security. Different types of technologies and devices have emerged to help screeners find security threats. While these tools assist the threat detection process, ultimate security decisions will always be made by human operators. This human factor results in a failure to detect many threats. This is especially the case with novice screeners, who do not have enough knowledge and experience in working with security devices. This unveils the need to take a novice from beginner to expert level in a short period (Hoghooghi, 2022). Moreover, Airport security officers (screeners) analyze X-ray images of passenger bags at the checkpoints where they are exposed to noise and social stress from passengers (Latscha & Schwaninger, 2024).

In such a complex environment, the need for a systematic and effective approach to developing and managing the core competencies of Airport security screening officers has become increasingly evident. In particular, without continuous monitoring of their capabilities and performance, there are limitations in preventing human error and responding swiftly and accurately to security threats.

To address these challenges, this study proposes a “Security Screening Training Programs (SSTP)”, designed to systematically educate, assess, and enhance the job competencies of newly recruited Airport security screening officers. By implementing a structured curriculum, this program aims to improve and validate their capabilities, ultimately fostering highly skilled Airport security screening officers.

Despite the increasing importance of security screening officers, existing training programs often lack a structured approach to systematically assess and improve their competencies. This issue will be further discussed in the theoretical background.

2. Background

2.1. Airport Security Screening

Airport security screening constitutes a systematic process designed to identify and detect weapons, explosives, and other hazardous materials that could compromise aviation security. To achieve this, diverse technologies and methodologies, including X-ray imaging, explosive trace detection (ETD), and manual inspection techniques, are employed. These measures aim to safeguard passengers, crew members, aircraft, and airport infrastructure from acts of unlawful interference, thereby ensuring the secure operation of aviation systems.

Airport security is broadly classified into two main categories based on the area where security operations are conducted: passenger terminal security screening and the protection of critical infrastructure within both airside and landside areas.

Among these measures, security screening is a fundamental component of airport security, aimed at safeguarding passengers, crew members, ground personnel, and airport facilities from acts of unlawful interference that may occur both on the ground and in-flight.

Specifically, airport security screening is a systematic procedure involving the identification and detection of hazardous materials, including weapons, explosives, firearms, and other prohibited objects, that could endanger aviation security.

Security screening at airports is specifically defined as the process of identifying and detecting hazardous items—such as dangerous materials, firearms, and other prohibited objects—that may compromise the safe operation of aircraft.

This process involves thorough personal inspections and baggage screenings of departing passengers to ensure compliance with aviation security regulations and mitigate potential security threats.

Therefore, the primary purpose of conducting security checks can be defined as identifying and detecting prohibited hazardous items, such as weapons or explosives, that could be used to commit unlawful interference, as well as other objects that pose security threats. This process safeguards the safe operation of aircraft while protecting the lives and property of passengers.

X-Ray screening of passenger bags is an essential component of airport security. Large investments into technology have been made in recent years. However, the most expensive equipment is of limited value, if the humans who operate it are not selected and trained appropriately. Scientific studies have shown that human performance in x-ray image interpretation depends critically on individual abilities and visual knowledge acquired through experience on the job and training (Michel et al., 2007).

Screeners who are operating an x-ray machine are essentially performing an object recognition and visual search task. Object recognition is a key function of human perception and the cognitive system (Halbherr et al., 2013).

The last decision is always taken by a human operator (screener) who often has only a few seconds to decide whether a bag contains a prohibited item or not. Therefore, as long as humans are the last entity in the security process at an airport, research should focus on the question how humans can be trained appropriately, in order to assure a high quality of their work (Schwaninger et al., 2007).

While many governments and airport operators have emphasized the importance of security training and committed a large amount of budget to security training programs, the implementation of security training programs was not proactive but reactive (Shim et al., 2013).

Research on appropriate training methods and enhancements of the human factor are essential to achieve and maintain high levels of security (Michel et al., 2014).

2.2. Security Screening Officers Training Programs

2.2.1. Training Mandated by National Regulations

Airport security screening represents a fundamental process in aviation security, aimed at preventing prohibited items that pose potential threats from being brought into restricted areas or onboard aircraft prior to departure. To ensure passenger safety, security screening employs advanced equipment such as X-ray machines, body scanners (walk-through detectors, hand-held metal detectors), and explosive detection equipment (Explosive Trace Detectors). Airports across South Korea, including Incheon International Airport, rigorously adhere to both national and international aviation security regulations to maintain the highest standards of security compliance.

As outlined in

Table 1 fulfilling the duties of a security screening officer necessitates the successful completion of the training program mandated by the ‘National Civil Aviation Security Education and Training Guidelines,’ as well as passing the final evaluation to obtain official certification as a qualified security screening officer.

Table 1 outlines the mandated training components for security screening officers, detailing a structured learning progression. The Security Screening Basic Course (ASTP123/Basic) consists of 40 hours of foundational instruction, culminating in a formal evaluation. Subsequently, On-the-Job Training (OJT) provides 80 hours of practical, hands-on experience without formal assessment. The program concludes with a Final Test, a 4-hour comprehensive evaluation designed to assess the officers’ job performance and X-Ray Screening performance competency.

2.2.2. Specialized Training Professional Competency Development

Security screening officers at Incheon International Airport participate in not only the mandatory training programs prescribed by international regulations and the National Civil Aviation Security Education and Training Guidelines but also specialized in-house training programs aimed at enhancing their professional expertise. These training programs typically include theoretical knowledge of aviation security regulations, practical training on X-ray image interpretation, simulation-based exercises, and performance evaluations. Designed to strengthen the ability of security screening officers to effectively identify potential threats, the programs focus on developing key competencies. Additionally, as outlined in

Table 2 the training programs adopt a level-based customized curriculum design to maximize learning outcomes and efficiently foster professional growth through a comprehensive and structured approach.

2.2.3. X-Ray Screening Rating System (XRS)

The Incheon International Airport Security Screening Rating System (XRS) is a structured evaluation framework designed to objectively assess the core competencies of security screening officers. It aim to enhance personnel management efficiency, improve reading screening and detection capabilities, and mitigate human errors. The system regularly assesses the screening proficiency of security officers, assigns competency grades based on evaluation outcomes, and defines work scopes accordingly. This approach maximizes workforce efficiency, fosters motivation through competency-based recognition, and facilitates the early identification and targeted training of underperformers, thereby functioning as an effective preventive mechanism against security breaches.

To ensure the reliability and validity of the evaluation process, the XRS incorporates multiple assessment components, including on-the-job X-ray screening performance, results from X-ray screening simulator evaluations, and scores from regular computer-based training (CBT) programs for security officers. Furthermore, it employs a weighted scoring method that varies according to the significance of each component. Through this comprehensive and differentiated evaluation system, Incheon International Airport has established a customized competency management approach for its security screening personnel.

Skorupski & Uchronski(2015) As a result of this analysis a recommendation was made that comprehensive training sessions should be organised every 12 months, whereas ongoing training sessions should be held every 6 months (Skorupski & Uchronski, 2005). Furthermore, in Europe, a minimum of six hours of mandatory training and testing is required every six months (Hättenschwiler 2018). Based on previous research findings, Incheon International Airport Security has also designed and implemented a six-month evaluation cycle for its Security Screening Rating System (XRS).

2.2.4. Security Screening Training Program (SSTP)

The Security Screening Training Program (SSTP) at Incheon International Airport Security is a systematically designed educational program aimed at fostering the independent operational capabilities of newly recruited security screening officers. As outlined in

Table 3 the program is operated with the objective of strengthening professional expertise and enhancing job competencies through step-by-step tailored training and evaluation.

The SSTP is broadly divided into two areas: carry-on baggage screening and checked baggage screening. To reinforce screening officers’ competencies at each stage, the curriculum is structured into Basic, Intermediate, and Intensive courses. Furthermore, functional education is introduced to provide more specialized training customized to each job position, thereby operating a more segmented and targeted educational framework.

2.3. Preceding study

Various countries have conducted prior research on the training and education of security screening officers. In particular, studies in the 2000s focused on the evaluation of Computer-Based Training (CBT) (Schwaninger & Hofer, 2004; Koller et al., 2008) and the effectiveness of computer-based training (CBT) using the X-Ray Tutor (XRT) (Schwaninger et al., 2007). During the 2010s, research examined the evaluation of airport security training programs (Shim et al., 2013) and the relevance of training to enhance the efficiency of X-ray screening in airport security. More recently, in the 2020s, studies have explored ‘targetless’ search training (Muhl-Richardson, 2021) and the development of MOOC-based aviation security X-ray simulator learning media (Yuniar et al., 2023).

Previous studies have predominantly focused on standardized training approaches, despite the necessity for differentiated learning strategies tailored to the distinct needs of novice and experienced security screening officers. Therefore, future research should focus on developing customized training models that account for varying levels of experience and competency. Additionally, empirical studies are required to assess the impact of these tailored training models on the performance and decision-making accuracy of security screening officers.

3. Methodology

3.1. Research Design

This study analyzed the training program currently implemented for security screening officers at Incheon International Airport by evaluating the outcomes of program participants. Statistical analyses, including Levene’s test and t-test, were conducted to examine correlations and differences in screening competencies based on demographic variables such as gender and age.

3.2. Study Paricipants

This study included total of 142 newly recruited security screening officers with less than one year of experience participated, comprising 57 males and 85 females.

Table 4 provides a concise overview of the demographic characteristics of the Incheon International total Airport Security officers, while

Table 4 presents the demographic distribution of the training program participants.

Table 5 presents the demographic distribution of participants in the training program based on age and gender. The total sample includes 142 newly hired security screening officers, comprising 57 males and 85 females. The majority of participants are concentrated in the 22 to 26 age range, accounting for a substantial portion of the sample. Notably, females outnumber males across most age groups, particularly between ages 22 and 26. The table highlights the relatively young and predominantly female composition of the trainee cohort.

3.3. Data Collection and Analysis

Data collection was conducted by gathering performance results from 142 newly recruited employees who participated in the Security Screening Training Program (SSTP). Statistical analyses, including Levene`s test and t-test, were performed to examine differences in competencies based on gender and age. All analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS Statistics to ensure the accuracy and reliability of the results.

4. Results

4.1. Total Undetected Distribution

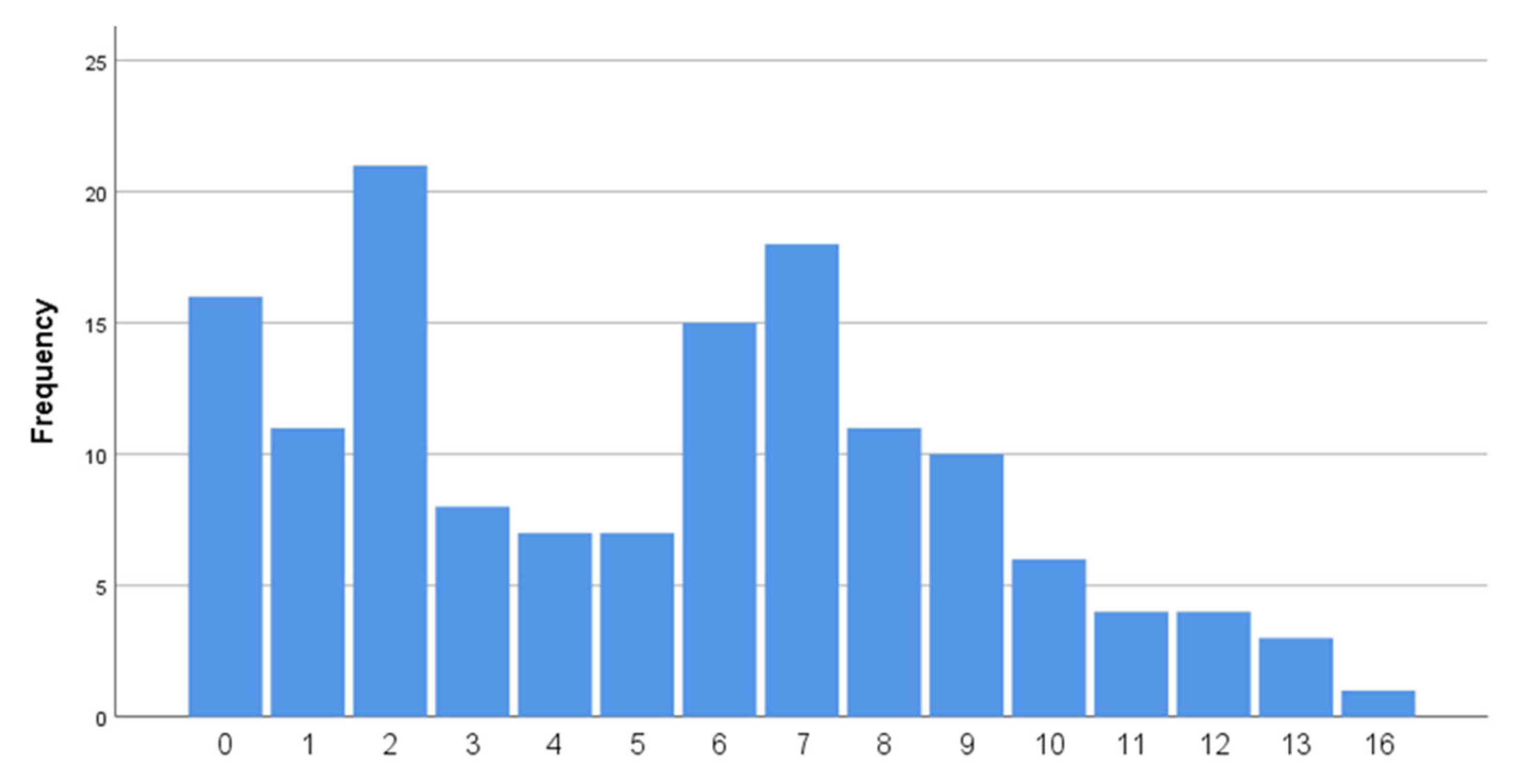

Table 6 displays the distribution of total undetected threats among the security screening officers in the sample (N = 142). The most frequently observed number of undetected threats was 2, reported by 21 participants (14.8%). This was followed by 7 undetected threats (12.7%), and 0 undetected threats (11.3%). The distribution gradually decreases at both ends of the scale. Notably, a small number of officers exhibited particularly high undetected counts, including 4 participants with 11 or 12 undetected threats, 3 with 13, and 1 officer with as many as 16 undetected threats. This indicates that while the majority of participants had moderate levels of undetected items, a few exhibited outliers on the higher end, which may be of concern from a security performance standpoint. The cumulative percentages in

Table 6 illustrate that approximately 60% of the participants had six or fewer undetected threats, suggesting that the bulk of the sample performed within an acceptable range. However, the long tail of the distribution highlights the need for targeted intervention or retraining for underperforming officers.

Figure 1 illustrates the frequency distribution of total undetected threats identified during the final assessment phase. As shown in the figure, undetected counts ranged from 0 to 16, with higher frequencies observed at scores of 2, 6, and 7. This distribution provides a visual representation of performance variation among newly recruited security screening officers.

4.2. Gender Differences in Undetected Threats

To examine whether there are statistically significant gender differences in the number of undetected threats, an independent samples t-test was conducted.

Table 7 presents the descriptive statistics for the total number of undetected threats categorized by gender. Group 1 (male) consists of 57 participants, with a mean undetected count of 5.65 (SD = 3.91), while Group 2 (female) includes 85 participants, with a mean of 4.93 (SD = 3.57). The standard error of the mean was 0.518 for males and 0.387 for females. These results indicate a slightly higher average of undetected threats among male screeners; however, further analysis is required to determine whether this difference is statistically significant.

As shown in

Table 8 Levene’s Test for Equality of Variances indicated that the assumption of equal variances was not violated (F = 0.176, p = 0.675). Therefore, the t-test results assuming equal variances were interpreted. The t-test revealed no significant difference in the mean number of undetected threats between male and female security screening officers (t(140) = 1.133, p = 0.259). The mean difference was 0.720 with a standard error of 0.635, and the 95% confidence interval for the difference ranged from -0.537 to 1.976. Even when equal variances were not assumed, the results remained statistically non-significant (t(112.642) = 1.112, p = 0.268). These findings suggest that gender does not significantly influence the likelihood of failing to detect prohibited items during security screening procedures.

4.3. Age Differences in Undetected Threats

This section investigates the distribution of undetected threats based on the age of airport security screening officers.

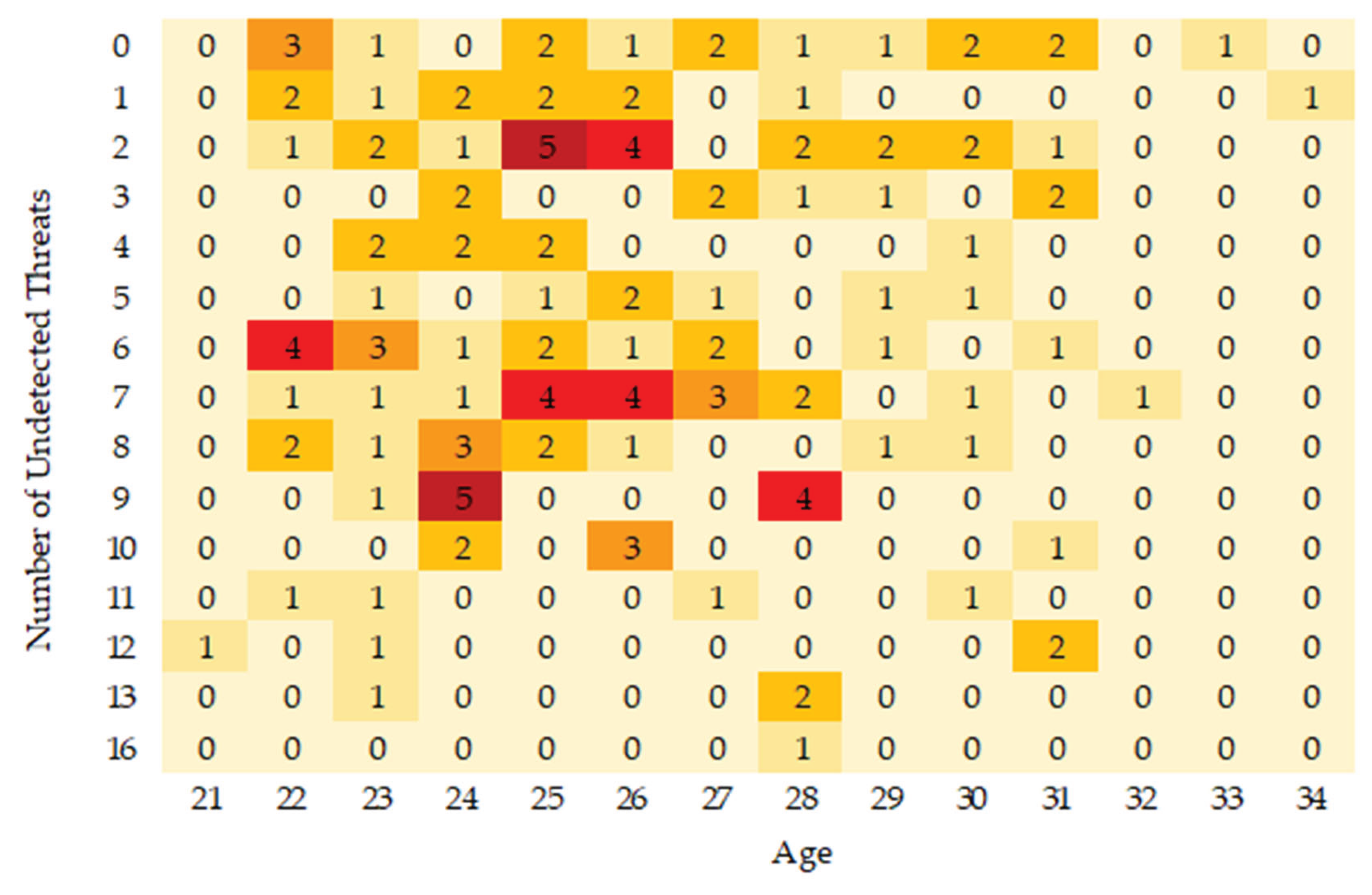

Figure 2 presents the frequencies of undetected threats across a range of age groups, illustrating variations in performance across experience and age related cohorts.

The total sample included 142 security screeners, ranging in age from 21 to 37 years old. The age group with the highest representation was age 25 (n = 20), followed by age 24 (n = 19) and age 26 (n = 18). These three age groups alone account for over 40% of the total sample, providing a robust basis for comparing detection performance.

An analysis of the

Figure 2 reveals that certain age groups are more frequently associated with higher numbers of undetected threats. For example, screeners aged 22 to 26 demonstrated the most frequent occurrences of mid to high level undetected counts. Specifically:

Age 22: 4 participants failed to detect 6 items, and 1 participant missed 11.

Age 23: Showed a broad distribution, including 3 participants missing 6 items and one each missing 11, 12, and 13 items.

Age 24: Had the highest number of screeners missing 9 items (5 participants), and multiple instances in the 3–8 item range.

These observations suggest that while this age range may correspond with an early or intermediate career stage, it is also associated with a relatively higher rate of missed threats. This could be due to a variety of factors, including limited on-the-job experience, lower exposure to diverse threat items, or cognitive overload during high pressure screening situations.

Conversely, participants over the age of 30—although fewer in number—tended to report lower undetected threat counts. For example, the majority of screeners aged 31 to 34 had low detection failure frequencies, with no individual missing more than 2 threats in most cases. A similar trend is seen in ages 33–37, where most screeners showed no instances of missing more than 1 item.

Interestingly, the youngest age group (age 21) showed only 1 individual, who missed 12 items, which may indicate either an anomaly or a performance risk associated with newly recruited or minimally trained screeners.

Overall, these findings suggest a potential nonlinear relationship between age and detection performance. While mid-20s screeners had more cases of undetected threats, older screeners, particularly those in their 30s, demonstrated lower miss rates. This may reflect the benefits of accumulated experience and better-developed threat recognition skills among more seasoned officers.

The results underscore the importance of tailored training interventions for different age groups. For younger or less experienced screeners, enhanced simulation-based training and real-time feedback may help reduce high miss rates. For older screeners, maintaining performance through refresher courses and updated threat libraries may help preserve their high accuracy rates.

4.4. Distribution of Undetected Threats by Termanal Type

To determine whether the number of undetected threats differed by terminal type, descriptive statistics and an independent samples t-test were conducted.

Table 9 presents the means and standard deviations of undetected threat counts for two terminal groups. Terminal 1 had 70 participants with a mean of 8.16 (SD = 2.49), while Terminal 2 had 72 participants with a significantly lower mean of 2.36 (SD = 2.15). The standard errors of the means were 0.297 and 0.253, respectively, indicating relatively precise estimates for both groups.

Levene’s Test for Equality of Variances was not significant (F = 1.242, p = 0.267), suggesting that the assumption of equal variances holds

Table 10 Accordingly, the results of the t-test assuming equal variances were used for interpretation. The independent samples t-test showed a statistically significant difference in the number of undetected threats between the two terminal groups (t(140) = 14.880, p < 0.001). The mean difference was 5.796 with a standard error of 0.390. The 95% confidence interval for the difference ranged from 5.026 to 6.566, indicating that the number of undetected threats was significantly higher in Terminal 1 than in Terminal 2. These findings suggest that terminal type is a significant factor affecting the performance of security screeners in detecting prohibited items.

4.5. Distribution of Undetected Item by Prohibited Carry-on Type

This section presents an in-depth analysis of the undetected distribution of prohibited carry-on items as discovered during airport security screening processes.

Table 11 provides a comprehensive breakdown of each item’s total undetected count and the corresponding undetected rate, offering insights into the relative detection difficulties across various prohibited objects. Considering the potential exposure of vulnerabilities within the security screening process at Incheon International Airport, the specific item names have been withheld to maintain operational security and prevent misuse of the findings.

Among the wide array of items assessed, Item-001 emerged as the most frequently undetected item, with a total of 51 instances and an undetected rate of 33.1%, indicating a high failure rate in identifying this particular threat. Similarly, Item-002 and Item-003 ranked second and third, with undetected rates of 22.7% and 18.2%, respectively. These results are significant considering that such items could pose substantial safety risks if brought onboard undetected.

Other commonly missed items included Item-004 (17.5%), Item-005 (16.9%), and Item-006 (15.6%). Notably, several bladed tools and small firearms-related objects had relatively high undetected rates, such as Item-007 (14.9%), Item-008 (13.0%), and Item-010 (10.4%). These findings suggest that metallic items with concealable forms, or those resembling household tools, present unique challenges in x-ray screening, particularly when partially obscured or disguised within cluttered bags.

Interestingly, a number of items categorized as Improvised Explosive Devices (IEDs)—such as laptop IEDs, stick fireworks, tumbler IEDs, and cigarette pack IEDs—also appeared with measurable undetected counts. Although their individual rates ranged from 3.2% to 7.1%, the collective presence of these fabricated or disguised devices highlights the increasing sophistication of threats that screeners must be prepared to recognize.

Further down the list, items like scalpels, plastic cutters, ceramic knives, and multi-tools were also frequently overlooked. The presence of such items on the list may point to challenges in distinguishing between benign tools and potential threats, especially when visual interpretation is constrained by operator fatigue or high passenger volume.

While many items were identified with low undetected rates—such as bracelet knives, draft knives, and various types of BBs—what remains noteworthy is the long tail of the distribution, encompassing a variety of customized, camouflaged, or less-common items like Swiss knives, plasma lighters, or pen-shaped blades. These were either undetected in small numbers or not at all, yet their very inclusion demonstrates the evolving tactics of individuals attempting to bypass security measures.

At the bottom of the distribution, a substantial number of items reported zero undetected instances. These included common dangerous items like military knives, kitchen knives, fireworks, and mock grenades, which are likely easier to detect due to their distinctive shapes, materials, or high recognition rates among experienced screeners.

In summary, the data illustrate that detection performance varies significantly depending on item type, complexity, and potential for concealment. These findings emphasize the necessity of enhancing both technological support systems and human training to address specific weaknesses in screening. A targeted approach to screening education, especially focused on commonly missed items, may lead to a substantial improvement in aviation security outcomes.

5. Discussion

First, the analysis revealed no statistically significant differences in X-ray image interpretation capabilities based on gender. This suggests that factors other than gender—such as age, training duration, and learning environment—may play a more influential role in detection performance. Interestingly, among experienced screeners at Incheon International Airport, females showed slightly higher average scores in the X-ray Screening Rating System (XRS). This implies that while gender may not initially affect performance among newly hired screeners without formal training, it could become a factor following structured training and skill development. The results therefore indicate that differences in cognitive or learning styles between genders during training, rather than gender itself, may influence screening performance. To support this interpretation, future research should incorporate a broader analysis of variables such as gender, training methodology, learning attitude, and the effectiveness of instructional techniques.

Second, the analysis of detection capability across different age groups also showed no statistically significant differences. This suggests that age alone does not directly influence X-ray interpretation performance. However, the data exhibited a tendency for older screeners to have lower miss rates. This trend may be influenced by several interrelated factors:

Motivation: Screeners who begin their careers later in life may demonstrate a stronger desire to quickly master job responsibilities, enhancing their focus and learning efficiency.

Social experience and cognitive maturity: Older individuals may leverage accumulated life experience and higher levels of cognitive development, resulting in more accurate and cautious threat identification.

Responsibility and awareness: Older employees may take their duties more seriously and approach the task with greater caution, increasing their accuracy in object identification and decreasing error likelihood.

Shim’s research has emphasized the influence of employee attitudes and workplace conditions on training outcomes, noting that these variables have not received adequate attention (Shim, 2013). Therefore, the relationship between age and detection performance is likely shaped by a complex set of factors beyond mere biological age, including motivational, experiential, and psychological components. Although no direct statistical correlation was observed, the lower miss rates among older screeners indicate that a multi-variable analysis, incorporating career experience and job attitudes, is warranted in follow-up studies.

Third, the comparison of detection capabilities between security screeners at Terminal 1 (T1) and Terminal 2 (T2) showed a statistically significant difference. Notably, T1 screeners exhibited higher miss rates than their T2 counterparts. Several possible factors may account for this disparity:

- 4.

Initial capabilities of newly hired screeners: Data suggest that those assigned to T2 tended to have higher evaluation scores during the recruitment process, potentially reflecting stronger foundational competencies before participating in formal training. This indicates that pre-employment assessment scores might be predictive of actual on-the-job performance, offering practical insights for improving recruitment strategies and training program design.

- 5.

Screening environment: T1 typically handles a higher passenger volume than T2. This workload may limit the amount of time and resources available for training new employees, thereby hindering skill development. Moreover, elevated cognitive load and fatigue associated with higher screening demands may contribute to reduced interpretation accuracy.

McCarley has emphasized the importance of aligning screener training and job design with human perceptual and cognitive limits (McCarley, 2004). Skorupski and Uchronski have similarly noted that the effectiveness of airport screening relies on numerous human and subjective factors, many of which defy objective measurement (Skorupski, Uchronski, 2015). Therefore, the variation in detection performance between terminals is not merely a matter of location but likely results from a combination of environmental factors, passenger characteristics, and differences in training and experience. Follow-up research involving field observations and screener perception surveys will be essential for a more nuanced understanding of how terminal-specific conditions affect performance.

Lastly, the analysis of undetected items by prohibited carry-on type revealed particularly high miss rates for certain items. As shown in

Table 11. the top 10 item types accounted for the majority of undetected cases. This finding suggests that new security screeners consistently struggle with identifying specific types of items during X-ray interpretation.

The data indicate that the complexity, material composition, and size of items significantly affect detection rates. Biggs and Mitroff have argued that while technological advancements may improve search accuracy, the human element remains the strongest or weakest link in security screening (Biggs, Mitroff, 2014; Yu 2018). This underscores that X-ray screening accuracy depends less on the technology itself and more on the cognitive capabilities of the screener. According to Swann, the successful identification of target objects depends on whether the screener has a stored mental representation of the item in working memory (Swann, 2016). This highlights the necessity of repetitive and systematic training to strengthen visual recognition skills.

Michel has further asserted that well-designed computer-based training (CBT) programs can significantly enhance detection performance if used consistently for recurrent training (Michel, 2007). In line with this, the Security Screening Training Program (SSTP) at Incheon International Airport utilizes customized, step-based instruction and CBT to build visual recognition and interpretation skills through repetition and practice. The effectiveness of SSTP suggests that targeted training focusing on commonly missed items can improve detection accuracy. Future iterations of the program should incorporate data-driven modules specifically designed to address high-miss items, thereby enhancing the overall visual and interpretive competency of newly hired screeners.

In conclusion, the discussion reveals that factors such as training, cognitive load, prior experience, and item complexity influence detection performance more profoundly than demographic characteristics like age or gender. These findings underscore the importance of targeted training and operational adjustments to improve security screening effectiveness across diverse terminal environments.

Newly Added Discussion

The analysis of undetected threats among airport security screening officers reveals several key factors influencing detection performance, notably age, gender, terminal assignment, and the nature of prohibited items. Each of these factors contributes uniquely to the overall efficacy of security operations.

The data indicates that officers aged 22 to 26 exhibit higher instances of undetected threats, with notable peaks at ages 24 and 25. This trend may be attributed to the relative inexperience of individuals in this age bracket, as they are likely in the early stages of their careers. Limited exposure to diverse threat scenarios and developing proficiency in interpreting complex X-ray images could contribute to this performance gap. Conversely, officers over the age of 30 demonstrate lower counts of undetected threats, suggesting that accumulated experience and familiarity with screening protocols enhance detection capabilities. This observation aligns with findings that highlight the positive correlation between experience and detection performance in security screening contexts (Michel 2007; Hoghooghi 2022).

The analysis reveals a marginal difference in detection performance between male and female officers, with males exhibiting a slightly higher mean of undetected threats. However, this disparity is not statistically significant, indicating that gender does not substantially influence detection efficacy. This finding is consistent with prior research suggesting that, while minor variations may exist, gender is not a decisive factor in screening performance (Riegelnig & Schwaninger, 2006). It underscores the importance of focusing on training and experience rather than inherent demographic characteristics when addressing performance improvements.

A significant discrepancy in detection performance is observed between officers assigned to different terminals. Officers at Terminal 1 report a higher mean of undetected threats compared to their counterparts at Terminal 2. This variation could be influenced by factors such as differences in passenger volume, the complexity of screening procedures, or the availability and condition of screening equipment. Terminals with higher traffic may impose greater cognitive loads on officers, potentially leading to decreased vigilance and increased error rates. This aligns with studies indicating that increased task demands and time pressure can negatively affect threat detection performance (Riegelnig & Schwaninger, 2006). Addressing these disparities may require targeted resource allocation and workflow optimization to ensure consistent performance across terminals.

Certain categories of prohibited items have exhibited relatively higher undetected rates during security screening procedures, indicating item-specific identification challenges in the screening process. These items may be more challenging to detect due to their size, shape, or composition, which can make them less conspicuous in X-ray images. Additionally, if such items are infrequently encountered, X-Ray Screening officers may have less familiarity with their appearance, leading to higher miss rates. This observation is supported by research indicating that low target prevalence can result in decreased detection rates (Mitroff et al., 2015). Enhancing training programs to include a broader range of threat items and employing threat image projection systems could improve recognition and detection of these less common threats.

The findings underscore the critical role of continuous, targeted training in enhancing detection performance. Regular exposure to a diverse array of threat items through simulated scenarios can bolster officers’ visual recognition skills and decision-making abilities. Implementing adaptive computer-based training systems has been shown to significantly improve detection rates by providing individualized feedback and progressively challenging tasks (Koller et al., 2009 Schwaninger, 2008). Such training initiatives can mitigate the impact of factors like inexperience and task difficulty, leading to overall improvements in security screening efficacy.

The disparities in detection performance across age groups and terminals highlight the need for operational adjustments and policy interventions. Allocating more experienced officers to high-traffic terminals or pairing less experienced officers with seasoned mentors could balance the workload and enhance overall performance. Additionally, regular performance evaluations and feedback mechanisms can help identify specific areas where officers may require additional support or training. Policies that promote a culture of continuous learning and adaptability are essential in maintaining high-security standards.

The variation in detection performance between terminals suggests that equipment differences may play a role. Ensuring that all terminals are equipped with up-to-date, standardized screening technology can provide officers with reliable tools necessary for effective threat detection. Investing in advanced imaging technologies and integrating artificial intelligence to assist in identifying potential threats can further augment human capabilities and reduce the likelihood of undetected items passing through security checkpoints (Schwaninger et al., 2008).

High workloads and prolonged periods of vigilance can lead to cognitive fatigue, adversely affecting detection performance. Implementing structured break schedules and rotating assignments can help alleviate fatigue and maintain high levels of alertness among officers. Research indicates that strategic breaks and workload management are effective in sustaining optimal performance levels in tasks requiring sustained attention (Lyubykh et al., 2022). By prioritizing officer well-being, security agencies can enhance both job satisfaction and operational effectiveness.

The analysis highlights the multifaceted nature of factors influencing detection performance among airport security screening officers. Age, terminal assignment, and the characteristics of prohibited items each contribute to the observed variations in undetected threat rates. Addressing these issues requires a comprehensive approach that includes targeted training, operational adjustments, technological enhancements, and policies aimed at promoting continuous improvement and adaptability. By focusing on these areas, security agencies can strengthen their screening processes, thereby enhancing overall aviation security.

6. Conclusions

6.1. Academic Contribution

First, this study represents the first empirical analysis of X-ray interpretation competencies among newly recruited airport security screening officers in South Korea. Departing from prior qualitative approaches, it employs quantitative data to systematically analyze differences in screening performance based on gender, age, and terminal assignment. By objectively evaluating the professional competencies of screening officers, the study addresses a significant gap in the literature, offering empirical evidence that supports and enriches existing knowledge on screening personnel’s job performance. These findings provide a foundational dataset that can inform the development of future training programs and competency management systems in aviation security.

Second, this study challenges the limitations of traditional standardized training programs by highlighting the need for differentiated, target-specific education strategies. In particular, the Security Screening Training Program (SSTP) applied in this research includes level-specific curricula and structured evaluation processes that account for differences in competency between novices and experienced officers. The empirical demonstration of this competency gap substantiates the argument for customized training programs tailored to individual skill levels. The study thus makes an academic contribution by offering a concrete framework for establishing differentiated training and assessment systems, which can be used to enhance the effectiveness of education and evaluation across various professional tiers within airport security.

Third, the research underscores the need to prioritize human factors over technological solutions in efforts to strengthen the capabilities of security screening officers. Although technological advancements can improve detection accuracy, the study provides empirical support for the assertion that human operators remain the most critical—and potentially vulnerable—link in the screening process. Accordingly, it proposes the development of a systematic training and evaluation system focused on enhancing cognitive and perceptual competencies. The study also emphasizes the potential of the Object Recognition Test (ORT) as a recruitment tool to identify high-potential candidates with strong visual recognition skills. By proposing the incorporation of ORT into the recruitment pipeline, the research offers practical implications for more effective workforce selection and competency monitoring.

Furthermore, this study contributes to academic discourse on human resource development in aviation security by suggesting specific pathways for optimizing personnel training and recruitment. The findings can serve as a basis for refining future research agendas and guiding policy formulation in the field of airport security screening. Ultimately, the study not only advances scholarly understanding but also holds practical relevance for improving operational effectiveness and safety in airport environments.

6.1. Practical Implication

First, although no statistically significant differences were observed in X-ray interpretation performance based on gender, the findings imply that individual experience, the quality of training, and cognitive ability are more critical factors than gender itself. The interpretation and recognition of X-ray images appear to be more closely tied to individual knowledge and perceptual capabilities, underscoring that the effectiveness of security screening equipment is ultimately limited by the competencies of the human operators. As noted by Hofer and Schwaninger, “The fact that image- and knowledge-based factors strongly influence detection performance points out that the effectiveness of aviation security technology is limited by the abilities and expertise of the humans that operate it” (Hofer, Schwaninger, 2005). Accordingly, a tailored training and assessment system based on individual ability—rather than demographic attributes—is needed. There is broad consensus that computer-based training (CBT) is an effective tool for enhancing X-ray interpretation skills. “CBT is a very effective tool for increasing effectiveness and efficiency in aviation security screening” (Schwaninger, Hofer, 2004). CBT enables repeated practice in realistic simulation environments, making it highly effective for improving operational performance. This supports the need to systematically implement CBT-based training programs across screening operations.

Second, although age did not demonstrate statistically significant differences in detection performance, the data suggested a trend of decreasing miss rates among older screeners. This may reflect stronger motivation among those who enter the job later in life, as well as the benefits of greater life experience and cognitive maturity. Older screeners may perform more carefully and responsibly, demonstrating enhanced situational awareness and risk sensitivity. Therefore, these tendencies suggest that individual psychological and experiential factors may mediate the relationship between age and screening performance. Training strategies may need to consider the motivational and behavioral traits associated with age to support more effective learning outcomes for diverse age groups.

Third, the analysis showed that a disproportionately high number of missed detections occurred for certain types of prohibited items. The top ten item types accounted for the majority of all missed cases, indicating consistent difficulty among new screeners in accurately identifying specific categories of threats. This highlights the need for focused and repetitive training on high-miss-rate items, especially through CBT programs that enhance visual perception skills. Such training can improve intuitive understanding of item shapes and materials while helping screeners distinguish between visually similar objects. In this context, the use of X-ray Object Recognition Tests (ORTs) is highly recommended. X-ray ORTs are effective not only in the initial assessment of item recognition ability but also in strengthening the visual differentiation skills needed to distinguish everyday items from potential threats. Implementing ORT-based training and evaluation prior to on-the-job deployment can ensure that new hires are both prepared and validated in terms of screening competency. This targeted approach will not only enhance detection accuracy but also contribute to the overall operational efficiency and safety of airport security screening.

Fourth, the results indicate that incorporating X-ray ORT as a key component of the hiring process can significantly improve the screening performance of newly recruited officers. “Compared to the screeners of the control group, who were not selected using the X-ray ORT, job applicants who were hired based on the results in the X-ray ORT as a pre-employment assessment tool performed significantly better in the PIT one year after employment” (Hofer, Schwaninger, 2006). This suggests that strengthening the role of ORT in candidate selection can improve overall screening effectiveness by enabling the recruitment of personnel who already possess high visual recognition aptitude. In the U.S., the TSA has demonstrated the efficacy of this approach through the use of the X-ray Screener app. “X-ray Screener was administered to over 3,000 Transportation Security Officers and performance was compared to their on-job metrics of performance (e.g., accuracy at covert test and speed to process bags at the checkpoint)” (Mitroff, Sharpe, 2021). The application has already been adopted across various airports in Australia, where it provides objective data to support hiring decisions (Mitroff, Sharpe, 2021).

The essential role of competent personnel in aviation security cannot be overstated. “Having competent workers is important in any industry, but particularly so in airport security. Since certain visual abilities are essential to become a good x-ray screener, preemployment testing needs to form a staple part of screener employment procedures” (Schwaninger, Wales, 2009). While technological innovation can enhance detection capabilities, it remains critical to recognize that human operators are the most decisive variable in the success—or failure—of screening systems. “Technology may improve search accuracy, but the human element is ultimately the weakest—or the strongest—link in security screening” (Biggs, Mitroff, 2015). Therefore, developing and implementing comprehensive training and evaluation systems that focus on human capabilities is an operational necessity.

Based on these findings, it is clear that enhancing the capabilities of airport security screeners requires improvements not only in training content and delivery but also in recruitment processes. Strengthening pre-employment assessment tools such as ORT and expanding CBT-based training modules can significantly improve both the accuracy and efficiency of security screening. These insights offer practical value for the future development of screening officer training programs and can contribute meaningfully to national efforts to establish standardized competency management systems for aviation security personnel.

6.3. Limitations and Future Research Directions

This study is limited in scope as it exclusively examined 142 newly hired security screeners at Incheon International Airport. As such, it does not fully account for broader variations in training environments, prior experience, or educational background, which may affect generalizability to other airports or to experienced personnel. Moreover, the findings are closely tied to the Security Screening Training Program (SSTP) implemented at Incheon, limiting the applicability of results to nationwide screening operations.

Future research should expand its focus to include experienced screeners to systematically examine how accumulated field experience influences X-ray interpretation capabilities. Comparative analyses between novice and veteran screeners could provide insights into performance growth over time and inform differentiated training strategies. Additionally, studies validating the effectiveness and scalability of the X-ray Screening Rating System (XRS) used in conjunction with SSTP are necessary to evaluate its utility as a competency management tool. Research should also explore the development of a Korean version of an Object Recognition Test (ORT)-based application for use during recruitment. Validating such a tool would enable early identification of high-potential candidates and improve personnel selection. Together, these directions would support the development of standardized and data-driven approaches to training, evaluation, and recruitment in aviation security.

References

- Zýka, J., & Děkan, T. (2017). AIRPORT SECURITY DETECTION C HECK WHAT ARE THE REAL LIMITS?. Perner’s Contacts, 12(4), 40-50. https://ojs.upce.cz/index.php/perner/article/view/476.

- Janssen, S., Sharpanskykh, A., & Curran, R. (2019). Agent-based modelling and analysis of security and efficiency in airport terminals. Transportation research part C: emerging technologies, 100, 142-160. [CrossRef]

- Liang, K. J., Sigman, J. B., Spell, G. P., Strellis, D., Chang, W., Liu, F., ... & Carin, L. (2019). Toward automatic threat recognition for airport X-ray baggage screening with deep convolutional object detection. arXiv preprint arXiv:1912.06329. https://arxiv.org/pdf/1912.06329.

- Janssen, S., van der Sommen, R., Dilweg, A., & Sharpanskykh, A. (2020). Data-driven analysis of airport security checkpoint operations. Aerospace, 7(6), 69. [CrossRef]

- Hoghooghi, S. (2022). Novice-to-expert knowledge transition in airport x-ray security screening (Doctoral dissertation, Queensland University of Technology). [CrossRef]

- Latscha, M., Schwaninger, A., Sauer, J., & Sterchi, Y. (2024). Performance of X-ray baggage screeners in different work environments: Comparing remote and local cabin baggage screening. International Journal of Industrial Ergonomics, 102, 103598. [CrossRef]

- Michel, S., Koller, S. M., De Ruiter, J. C., Moerland, R., Hogervorst, M., & Schwaninger, A. (2007, October). Computer-based training increases efficiency in X-ray image interpretation by aviation security screeners. In 2007 41st Annual IEEE international Carnahan conference on security technology (pp. 201-206). IEEE. [CrossRef]

- Halbherr, T., Schwaninger, A., Budgell, G. R., & Wales, A. (2013). Airport security screener competency: a cross-sectional and longitudinal analysis. The international journal of aviation psychology, 23(2), 113-129. [CrossRef]

- Schwaninger, A., Hofer, F., & Wetter, O. E. (2007, October). Adaptive computer-based training increases on the job performance of x-ray screeners. In 2007 41st annual IEEE international Carnahan conference on security technology (pp. 117-124). IEEE. [CrossRef]

- Shim, W., Massacci, F., De Gramatica, M., Tedeschi, A., & Pollini, A. (2013, September). Evaluation of airport security training programs: Perspectives and issues. In 2013 International Conference on Availability, Reliability and Security (pp. 753-758). IEEE. https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/document/6657316.

- Michel, S., Mendes, M., de Ruiter, J. C., Koomen, G. C., & Schwaninger, A. (2014). Increasing X-ray image interpretation competency of cargo security screeners. International journal of industrial ergonomics, 44(4), 551-560. [CrossRef]

- Skorupski, J., & Uchroński, P. (2015). A fuzzy model for evaluating airport security screeners’ work. Journal of Air Transport Management, 48, 42-51. [CrossRef]

- Hättenschwiler, N., Merks, S., & Schwaninger, A. (2018, October). Airport security X-ray screening of hold baggage: 2D versus 3D imaging and evaluation of an on-screen alarm resolution protocol. In 2018 International Carnahan Conference on Security Technology (ICCST) (pp. 1-5). IEEE. [CrossRef]

- Schwaninger, A., & Hofer, F. (2004). Evaluation of CBT for increasing threat detection performance in X-ray screening. WIT Transactions on Information and Communication Technologies, 30. https://www.witpress.com/elibrary/wit-transactions-on-information-and-communication-technologies/30/12657.

- Koller, S. M., Hardmeier, D., Michel, S., & Schwaninger, A. (2008). Investigating training, transfer and viewpoint effects resulting from recurrent CBT of X-Ray image interpretation. Journal of Transportation Security, 1, 81-106. [CrossRef]

- Muhl-Richardson, A., Parker, M. G., Recio, S. A., Tortosa-Molina, M., Daffron, J. L., & Davis, G. J. (2021). Improved X-ray baggage screening sensitivity with ‘targetless’ search training. Cognitive research: principles and implications, 6, 1-20. [CrossRef]

- Yuniar, D. C., Munir, M. S., Febiyanti, H., & Anwar, S. (2023). Development of X Ray Simulator Learning Media in Junior Aviation Security Course Based on MOOCS. JMKSP (Jurnal Manajemen, Kepemimpinan, dan Supervisi Pendidikan), 8(1), 50-60. [CrossRef]

- McCarley, J. S., Kramer, A. F., Wickens, C. D., Vidoni, E. D., & Boot, W. R. (2004). Visual skills in airport-security screening. Psychological science, 15(5), 302-306. [CrossRef]

- Biggs, A. T., & Mitroff, S. R. (2014). Improving the efficacy of security screening tasks: A review of visual search challenges and ways to mitigate their adverse effects. Applied Cognitive Psychology, 29(1), 142-148. [CrossRef]

- Yu, C. (2018). The role of human factors in airport baggage screening. ANU Undergraduate Research Journal, 9, 146-155. https://studentjournals.anu.edu.au/index.php/aurj/article/view/175.

- Swann, L. E. (2016). The role of intuitive expertise in airport security screening (Doctoral dissertation, Queensland University of Technology). https://eprints.qut.edu.au/98051/.

- Riegelnig, J., & Schwaninger, A. (2006). The influence of age and gender on detection performance and the criterion in x-ray screening. https://irf.fhnw.ch/server/api/core/bitstreams/b9531f86-c136-4433-b216-d58766fb5486/content.

- Mitroff, S. R., Biggs, A. T., & Cain, M. S. (2015). Multiple-target visual search errors: Overview and implications for airport security. Policy Insights from the Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 2(1), 121-128. [CrossRef]

- Koller, S. M., Drury, C. G., & Schwaninger, A. (2009). Change of search time and non-search time in X-ray baggage screening due to training. Ergonomics, 52(6), 644-656. [CrossRef]

- Schwaninger, A., Bolfing, A., Halbherr, T., Helman, S., Belyavin, A., & Hay, L. (2008). The impact of image-based factors and training on threat detection performance in X-ray screening. https://irf.fhnw.ch/server/api/core/bitstreams/cce4e6c4-1781-4d44-aea1-108b0d46bbea/content.

- Lyubykh, Z., Gulseren, D., Premji, Z., Wingate, T. G., Deng, C., Bélanger, L. J., & Turner, N. (2022). Role of work breaks in well-being and performance: A systematic review and future research agenda. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 27(5), 470-487. [CrossRef]

- Hofer, F., & Schwaninger, A. (2005). Using Threat Image Projection Data Forassessing Individual Screener Performance. WIT Transactions on the Built Environment, 82, 417-426. [CrossRef]

- Hofer, F., Hardmeier, D., & Schwaninger, A. (2006). Increasing airport security using the x-ray ort as effective pre-employment assessment tool. https://irf.fhnw.ch/server/api/core/bitstreams/5cda1317-3f4c-4287-9b5a-31cfc9b93c08/content.

- Mitroff, S. R., & Sharpe, B. (2021). Informing aviation security workforce assessment and selection amidst the COVID-19 pandemic. In 68th International Symposium on Aviation Psychology (p. 385). https://corescholar.libraries.wright.edu/isap_2021/64/.

- Schwaninger, A., & Wales, A. W. J. (2009). One year later: how screener performance improves in X-ray luggage search with computer-based training. In Contemporary Ergonomics 2009 (pp. 393-402). Taylor & Francis. [CrossRef]

- Biggs, A. T., & Mitroff, S. R. (2015). Improving the efficacy of security screening tasks: A review of visual search challenges and ways to mitigate their adverse effects. Applied Cognitive Psychology, 29(1), 142-148. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).