1. Introduction

Pine wilt disease (PWD) mainly caused by pine wood nematode (PWN) has been considered as one of the most serious pine forest diseases in the world [

1,

2]. Because of the huge economic and ecological losses caused by PWD, the prevention and control of the disease has become urgent [

3]. Up to now, one of the most effective and sustainable methods for the control of PWD is injecting insecticides into the trunk which can avoid spray drift of chemical pesticides and reduce environmental pollution [

4,

5]. However, prolonged use of the same insecticide may cause biological resistance resulting from single drug target, hence it is important to find new drug targets for developing novel nematicides to control PWN [

6,

7].

Thaumatin-like proteins (TLPs), a complex gene family product with amino acid sequence highly homologous to that of the sweet protein thaumatin from the West African plant

Thaumatococcus danielli, widely exist in plants and involve in plant defense and extensive development process [

8,

9,

10]. TLPs from watermelon, Emperor bananas, chestnut and wheat had anti-fungal function and could be used as botanical fungicide or as a potential gene in the engineering of disease-resistant plants [

9,

11,

12,

13,

14]. In addition, Fierens et al found a TLP from wheat (

Triticum aestivum) had a unique inhibition specificity on xylanase [

15]. Bormann et al and Osmond et al suggested that TLP may have β-1, 3-glucanase activity and be able to interact with β-1, 3-glucan to disrupt the synthesis of fungal cell walls [

16,

17]. Plant TLPs played important roles in response to abiotic stresses including cold [

18], drought [

19] and salinity [

20]. Animal TLPs were first reported in

Caenorhabditis elegans (Maupas) Kitajima and Sato (1999) [

21]. Brandazza et al. reported a TLP in the desert locust

Schistocerca gregaria with glucanase activity played a defense role against pathogens [

22].

RNA interference (RNAi) technology is an effective method to explore gene function, which can down-regulate the expression of specific genes through degrading homologous mRNA induced by double-stranded RNA [

23,

24,

25,

26]. Cheng et al. found that PWN cellulase had important influence on its parasitism and penetration in host plants, feeding, development and propagation by knockdown of a cellulase gene (

Bx-eng-1) of

B. xylophilus using RNAi [

27]. Zhao et al. assessed the function of

BxSapB2 gene in PWN by RNAi and confirmed that BxSapB2 silencing affected the virulence of PWN [

28].

At present, there are few reports on the function of tlp in PWN. The data from this study will support the understanding of the action mode of Bxtlp on PWN, which may be an important pathogenic factor of B. xylophilus and can be used as a new target for developing potential nematocides to control PWD.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Materials

PWNs were isolated from forests in Yantai city, Shandong, China, by Baermann funnel technique, and cultured on

Botrytis cinerea in Potato Dextrose Agar (PDA) plates at 25°C in darkness [

29,

30]. Mixed-stage PWNs were placed in Petri dishes at 25°C and cultured in darkness for 2 h to collect the eggs. The PWN eggs developed into J2 larvae after 24 h, and J4 larvae were obtained from J2 ones cultured for 48 h [

31,

32,

33,

34,

35].

2.2. Cloning of Bxtlp and Construction of Expression Vector

Total RNA was extracted from mixed-stage PWNs by using Trizol reagent [

36], and cDNA was synthesized with reverse transcription kit (Takara, Dalian, China).

The

Bxtlp without putative signal sequence was amplified by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) using a pair of primers designed according to the sequence of

Bxtlp (Forward: 5’-AAACATATGAAGACCCTCATTC-3’; Reverse: 5’-AAAGGATCCTTAAGGACAGTAG). The amplified products were ligated into pET-15b using T4-DNA ligase to construct the expression vector pET-15b-

Bxtlp (Takara, Dalian, China) [

35].

2.3. Bioinformatics Analysis of Bxtlp and BxTLP

The amino sequences of BxTLP were deduced according to the nucleotide sequences by using the Basic Local Alignment Search Tool (

https://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi). The open reading frame (ORF) of BxTLP from PWN was analysed by the ORF Finder program (NCBI, Bethesda, MD, USA;

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/gorf/gorf.html). The structure of PWN

Bxtlp was analyzed using WormBase ParaSite (

http://paras ite.wormbase.org/index.html). Multiple comparisons were conducted using DNAMAN software, and the phylogenetic tree was constructed using MEGA-X software. Signal peptides and transmembrane helices of BxTLP were predicted on the websites of

http://www.cbs.dtu.dk/services/SignalP-5.0/and http://www. cbs.dtu.dk/services/TMHMM/, respectively. SWISS-MODEL (

https://swissmodel.expasy.org/) was used to predict the structures of BxTLP and further analyzed using the PyMOL 2.3.2 software.

2.4. Expression and Purification of Recombinant BxTLP

Escherichia coli BL21 (DE3) (Takara, Dalian, China) was transformed with the pET-15b-

Bxtlp then cultured on LB medium. A single colony was then cultured in LB broth, after 4 h, 0.5 mM isopropyl-beta-D-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) was added to the broth to induce expression of recombinant BxTLP at 28°C [

37]. The engineering bacteria collected by centrifugation at 10,000 rpm for 25 min were suspended in 25 mL binding buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl, 0.5 M NaCl, 5 mM imidazole, pH 8.0), and lysed by ultrasonic processor (400 W, 4 s, 12 s, 120 cycle), followed by centrifugation at 10,000 g for 30 min. The recombinant BxTLP was purified by Ni-NTA affinity chromatography [

38].

2.5. Synthesis of Bxtlp dsRNA

T7 promotor was added to the RNA interference fragment (441bp) including the full-length ORF of Bxtlp through PCR with T7-labeled gene-specific primers (Forward: 5’-GATCACTAATACGACTCACTATAGGGCATATGAAGACCCTCAT TC-3’; Reverse: 5’- GATCACTAATACGACTCACTATAGGGGGATCCTTAAGGA CAGTAG-3’).

A pair of T7-labeled gene-specific primers (forward: 5’-GATCACTAATAC GACTCACTATAGGGAACGGCCACAAGTTCAGC-3’; reverse: 5’-GATCACTAAT ACGACTCACTATAGGGAAGTCGATGCCCTTCAGC-3’) with pET-15b-

gfp as the template was used to amplify the 323 bp DNA fragment of the green fluorescent protein gene. The double-stranded RNA (dsRNA) was synthesized with aforementioned amplified products as the templates by using the MEGscript RNAi Kit (Invitrogen, Vilnius, Lithuania) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. RNAi was carried out by soak method previously described by Xu et al [

38]. Briefly, approximately 3,000 PWNs were soaked in 50 µL solution containing

Bxtlp dsRNA (1.0 µg/µL) at 20°C for 72 h. PWNs soaked in 50 µL sterilized water and

gfp dsRNA solution (1.0 µg/µL) were used as double negative controls.

2.6. Effects of Bxtlp dsRNA on the Vitality of PWNs

Approximately 3,000 mixed-stage PWNs were soaked in 50 µL buffer containing

Bxtlp dsRNA (1.0 µg/µL) and incubated at 20°C in the darkness for 72 h. The vitality indexes including motility, feeding, reproduction, oviposition and hatching were investigated according to the methods reported previously [

39,

40].

100 PWNs were observed under a microscope (Motic, ECO-SZ-745, China) to evaluate the motility ability of PWN by counting head oscillation times in 30 seconds [

33].

100 PWNs were cultured in the dark at 25°C on a PDA plate covered with B. cinerea to investigate the effect of Bxtlp dsRNA on PWN feeding.

Fifty PWN couples were cultured in the dark at 25°C on a PDA plate covered with

B. cinerea for 9 days, and the nematodes isolated from the PDA plate were counted under the optical microscope to evaluate the reproductive capacity of PWNs [

39].

Fifteen PWN couples were cultured in 96-well plate containing sterilized water in the darkness at 25°C for 48 h, and the eggs was counted under an optical microscope. The same number of nematodes were soaked in the buffer containing sterilized water and gfp dsRNA as the negative control.

PWNs soaked in buffer solution containing sterilized water and gfp dsRNA were used as controls.

2.7. Effects of Bxtlp dsRNA on ROS Levels, Life Span and Female-Male Ratio in PWNs

Reactive oxygen species (ROS) levels in PWN treated with Bxtlp dsRNA were determined using the Reactive Oxygen assay kit (Nanjing Jiancheng Bioengineering Institute, Nanjing, China) according to the user manual. The fluorescence intensity was detected at an excitation wavelength of 485 nm and an emission wavelength of 528 nm under a fluorescence microscope (Olympus IX73, Tokyo, Japan).

In order to investigate the effect of Bxtlp dsRNA on the life span of PWN, 100 PWNs were cultured in 48-well plates to observe the survival of PWNs using a microscope (Motic, ECO-SZ-745, China). The PWNs were considered dead if the nematodes were stiff and did not move even by physical stimuli with a dissection needle.

Approximately 100 PWNs were cultured in a petri dish covered with Botrytis cinerea at 25°C in the darkness for 24 h to investigate the effect of Bxtlp dsRNA on the female-male ratio of PWN. The male and female individuals of PWN were counted under a microscope (Motic, ECO-SZ-745, China) and the female-male ratio was calculated.

2.8. Effect of Recombinant BxTLP on PWN

After soaked in the recombinant BxTLP solution (40 µg/mL) for 24 h, the five indexes of motility, feeding, reproduction, oviposition and hatching of PWN were determined according to the methods described in 2.6 section.

2.9. Determination of Antioxidant Activity of Recombinant BxTLP

2 mL solution A (1.25×10

−4 M recombinant BxTLP in 20 mM tris-HCl buffer, pH 8.0) was mixed with 2 mL of DPPH ethanolic solution (1×10

−4 M) to react for 30 min in dark, and then absorbance of the mixture was determined at 517 nm using microplate reader (Tecan, Spark, Shanghai, China) to be marked as A

BxTLP [

41,

42]. A0 was the absorbance of the reaction mixture without BxTLP.

The DPPH clearance rate (R%) was calculated according to formula (1):

At the same time, The DPPH clearance rate of Vc solution (1.25×10−5 M) was used as positive control.

2.10. The Effect of dsRNA and Recombinant BxTLP on the Pathogenicity of PWN

Approximately 2,000 mixed-stage PWNs were immersed in a 50 µL buffer (1.0 µg/µL) containing

Bxtlp dsRNA and incubated at 20°C in dark for 72 h [

39]. Then, the nematodes were inoculated into 1-year-old Pinus thunbergii saplings. PWNs treated with sterilized water and

gfp dsRNA were used as controls [

43]. The inoculated P. thunbergii saplings were cultured in a greenhouse at 25°C with 16 h of light and 8 h of darkness. The wilting symptoms of the saplings were monitored and photographed.

The effect of recombinant BxTLP on the pathogenicity of PWN was determined using the same method decribed above. PWNs soaked in Tris-HCl buffer and BSA solution, respectively were used as the controls.

2.11. Data Analysis

For all biological tests, each experiment was performed twice with three replications for each treatment. All values of repeated experiments were expressed as mean ± standard deviation (S.D.), and SPSS 25.0 software (SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA) was used for statistical analysis. Independent sample t-test and one-way analysis of variance were used among different groups. P value < 0.05 indicated statistical significance.

3. Results

3.1. Cloning and Sequence Analysis of Bxtlp in PWN

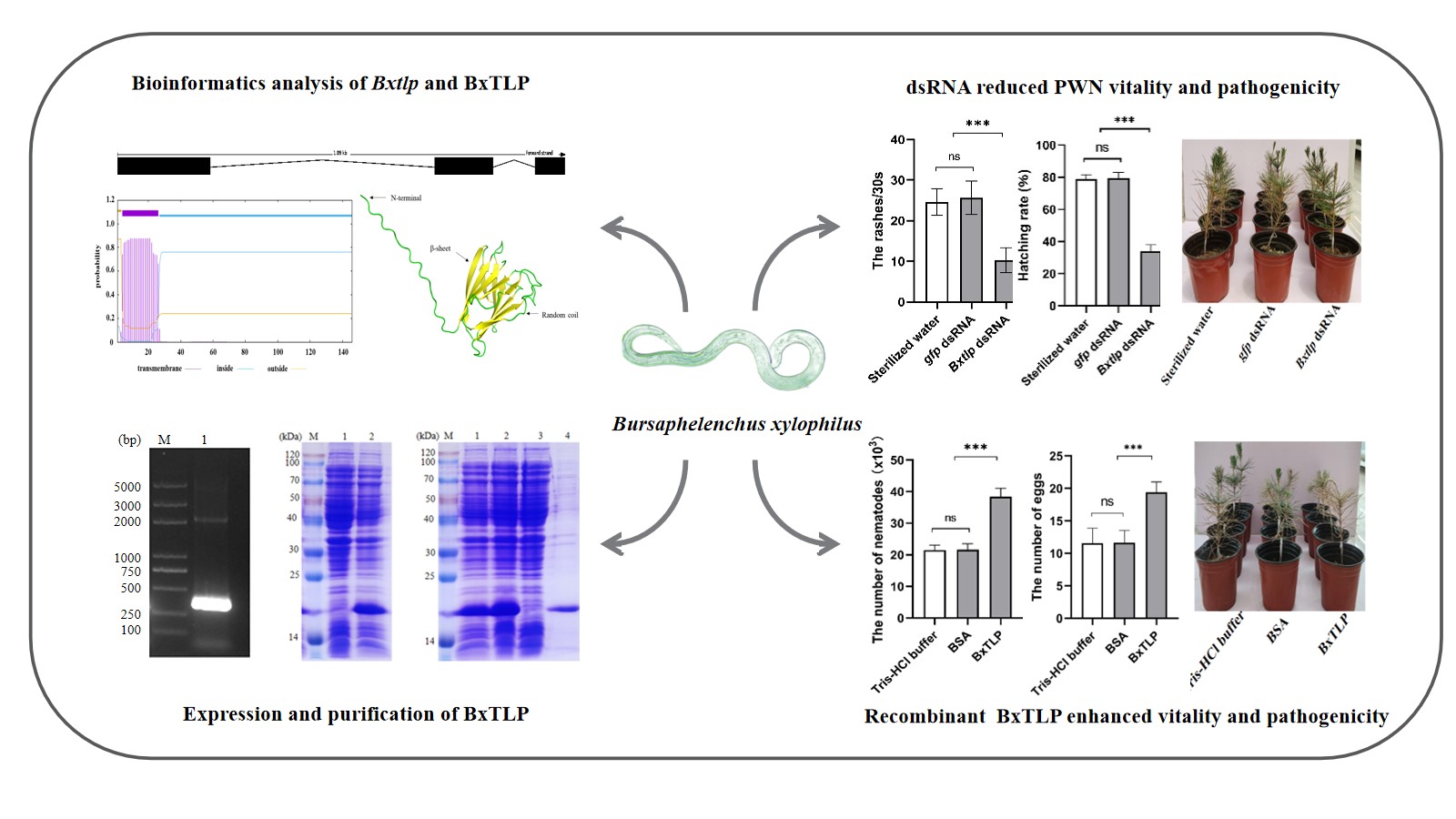

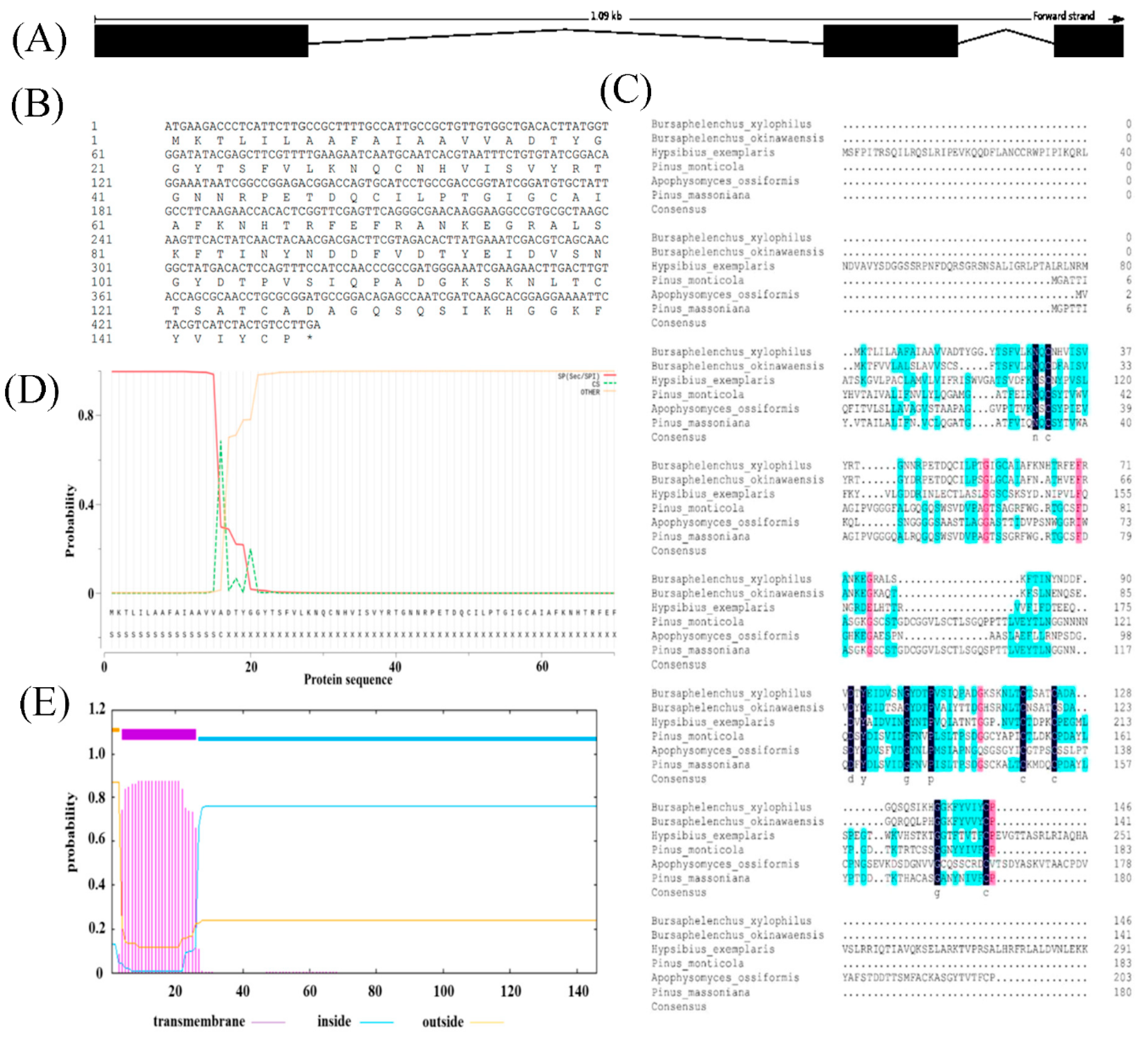

Sequence analysis of the

Bxtlp showed that the

Bxtlp (BXY_0431000.1) gene with 1,090 bp was composed of 3 exons and 2 introns (

Figure 1A), and the

Bxtlp ORF with 441 bp encoded a protein with 146 amino acids residues including 49 metal ion-chelating residues which were 9 lysine residues, 9 aspartate residues, 8 asparagine residues, 6 cysteine residues, 5 arginine residues, 5 glutamine residues, 4 glutamic acid residues, and 3 histidine residues (

Figure 1B). The amino acid sequence similarity of BxTLP to that of

Bursaphelenchus okinawaensis,

Hypsibius exemplaris,

Pinus monticola,

Apophysomyces ossiformis, and

Pinus massoniana was 64%, 28%, 32%, 23% and 31%, respectively (

Figure 1C). Further bioinformatic analysis revealed the presence of a signal peptide containing 16 amino acids in the amino acid sequence of BxTLP, suggesting that BxTLP may be a secreted protein (

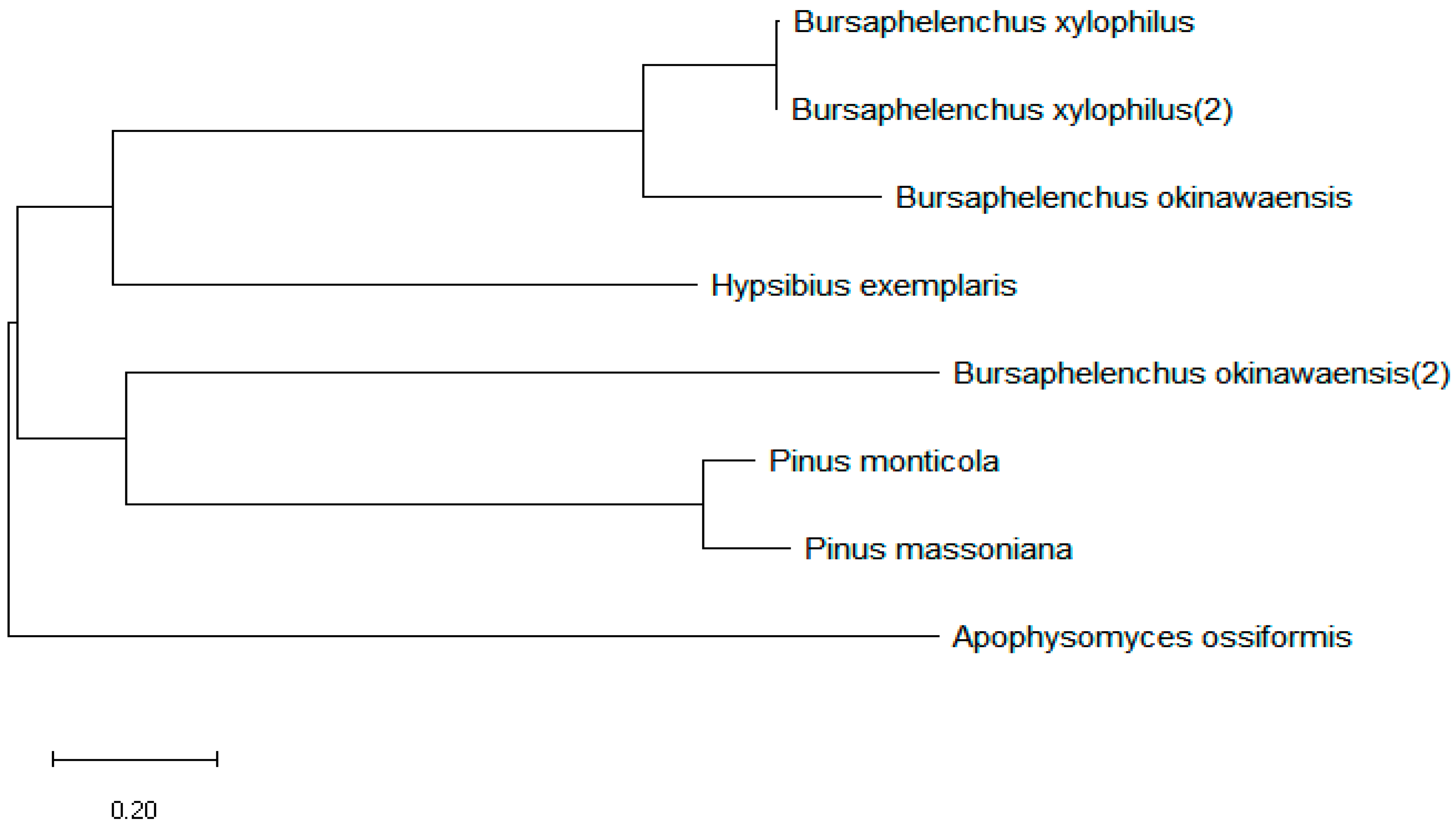

Figure 1D,E). The phylogenetic tree of the primary structure of this protein showed that the protein had high homology with that of

B. okinawaensis and

H. exemplaris, as well as

P. monticola and

P. massoniana (

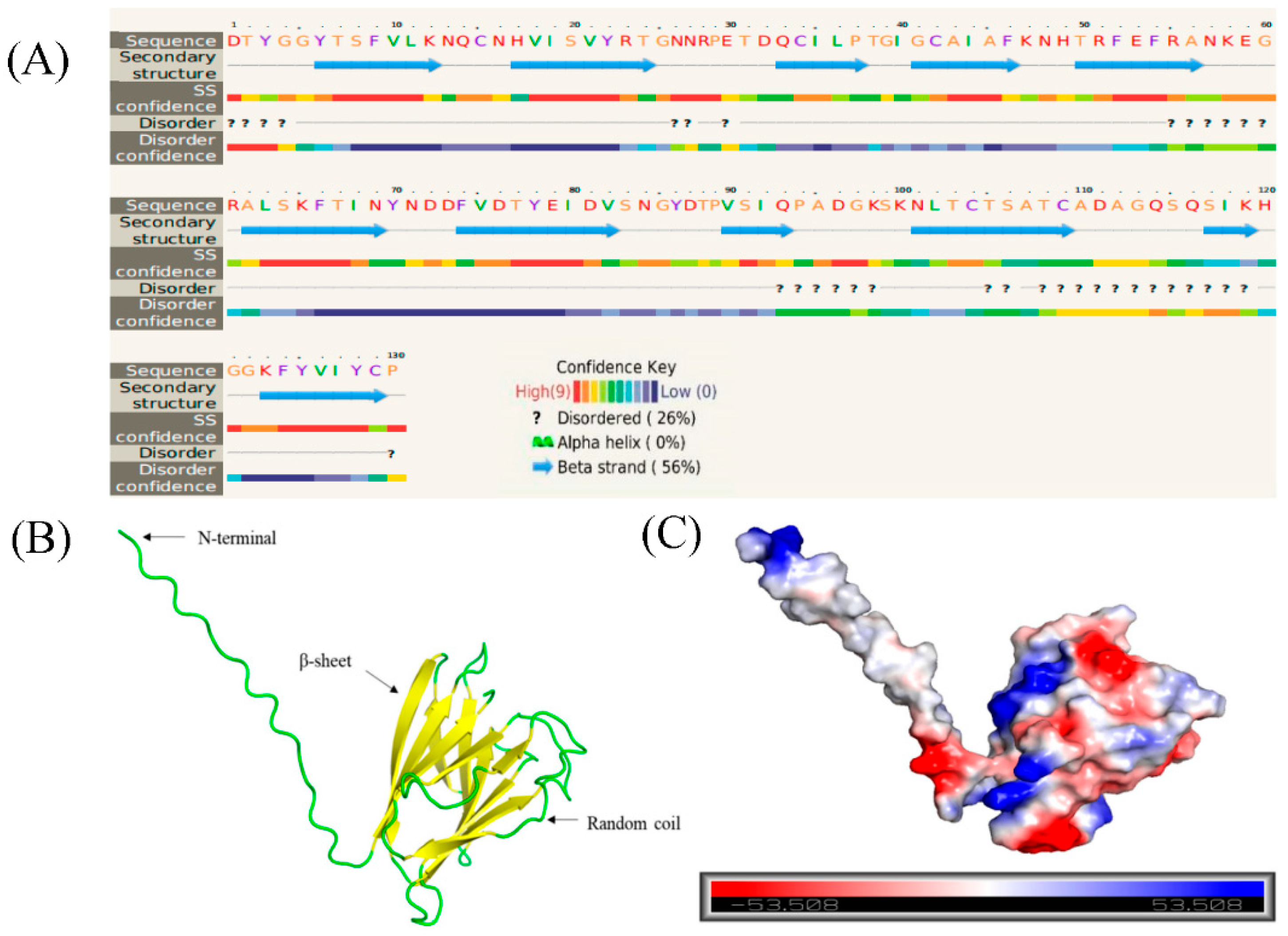

Figure 2). The advanced structure prediction of BxTLP showed that β-pleated sheet accounted for 56% of the secondary structure, and random curling accounted for 26% (

Figure 3A). The GMQE value of the modeling result was 0.88, and the similarity was 99.32%, which proved that the tertiary structure prediction was highly reliable. BxTLP consisted of 12 β-folded structures contributing to its stablility and had strong hydrophilicity (

www.novopro.cn/tools/protein-hydrophilicity-plot.html). Molecular surface modeling revealed mainly the presence of white patches, the electrostatic potential surface prediction results show that the surface of the molecule was mainly neutral, and a part of charged regions (

Figure 3B,C).

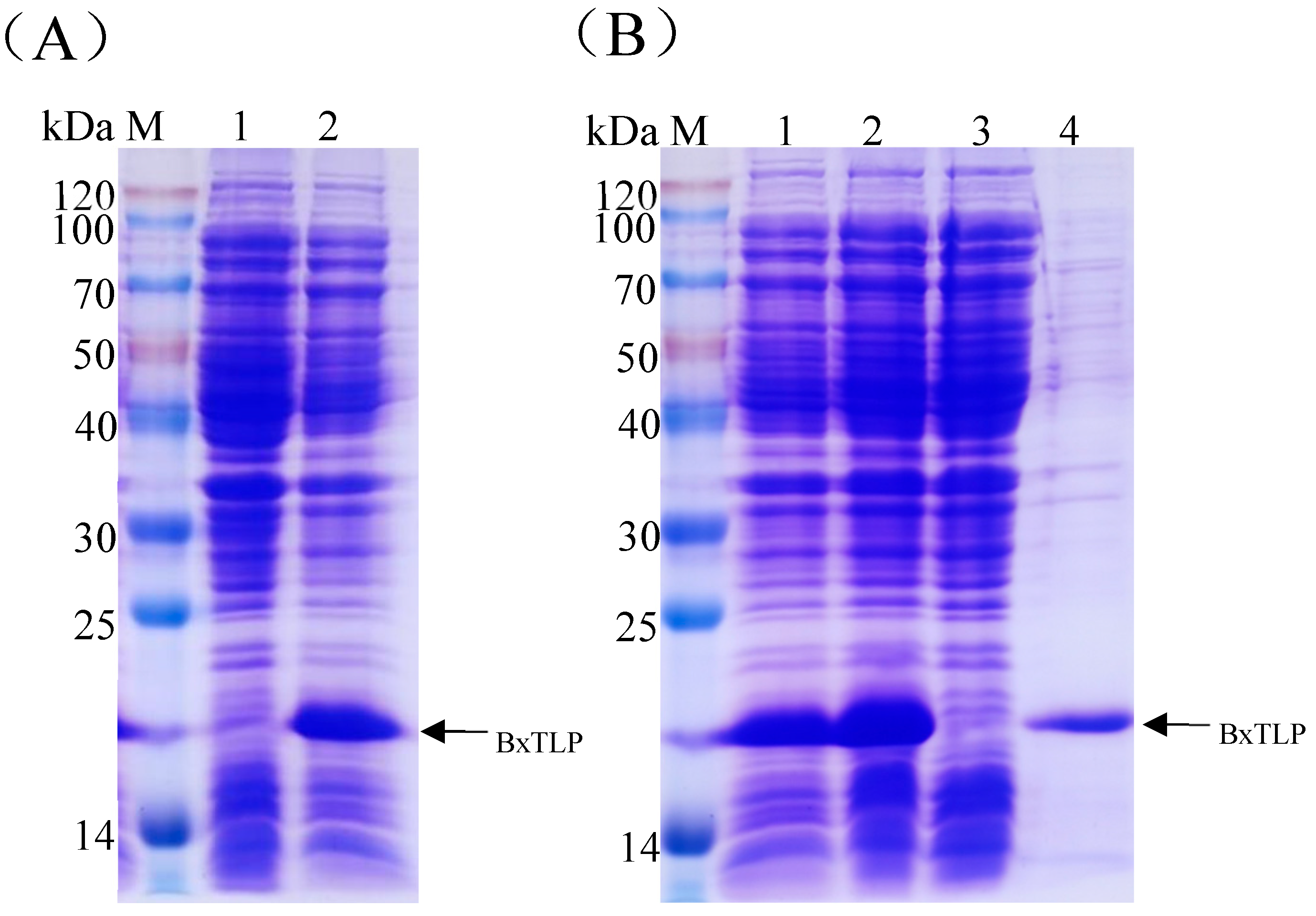

3.2. Expression and Purification of Recombinant BxTLP Protein

According to the sequence of

Bxtlp, a pair of primers were designed to amplify

Bxtlp gene from the cDNA of PWN by PCR. The PCR product was cloned into pET-15b to construct the recombinant vector PET-15B-

Bxtlp which was transformed into

E. coli BL21 (DE3) to construct engineered bacteria. The recombinant BxTLP was overexpressed in the engineering bacteria induced by IPTG (

Figure 4A) and mainly existed in soluble form (

Figure 4B). The recombinant protein was purified by Ni

2+ affinity chromatography to homogeneity with a relative molecular weight of 16 kDa based on SDS-PAGE analysis (

Figure 4B), which was consistent with that of BxTLP without the putative signal peptide.

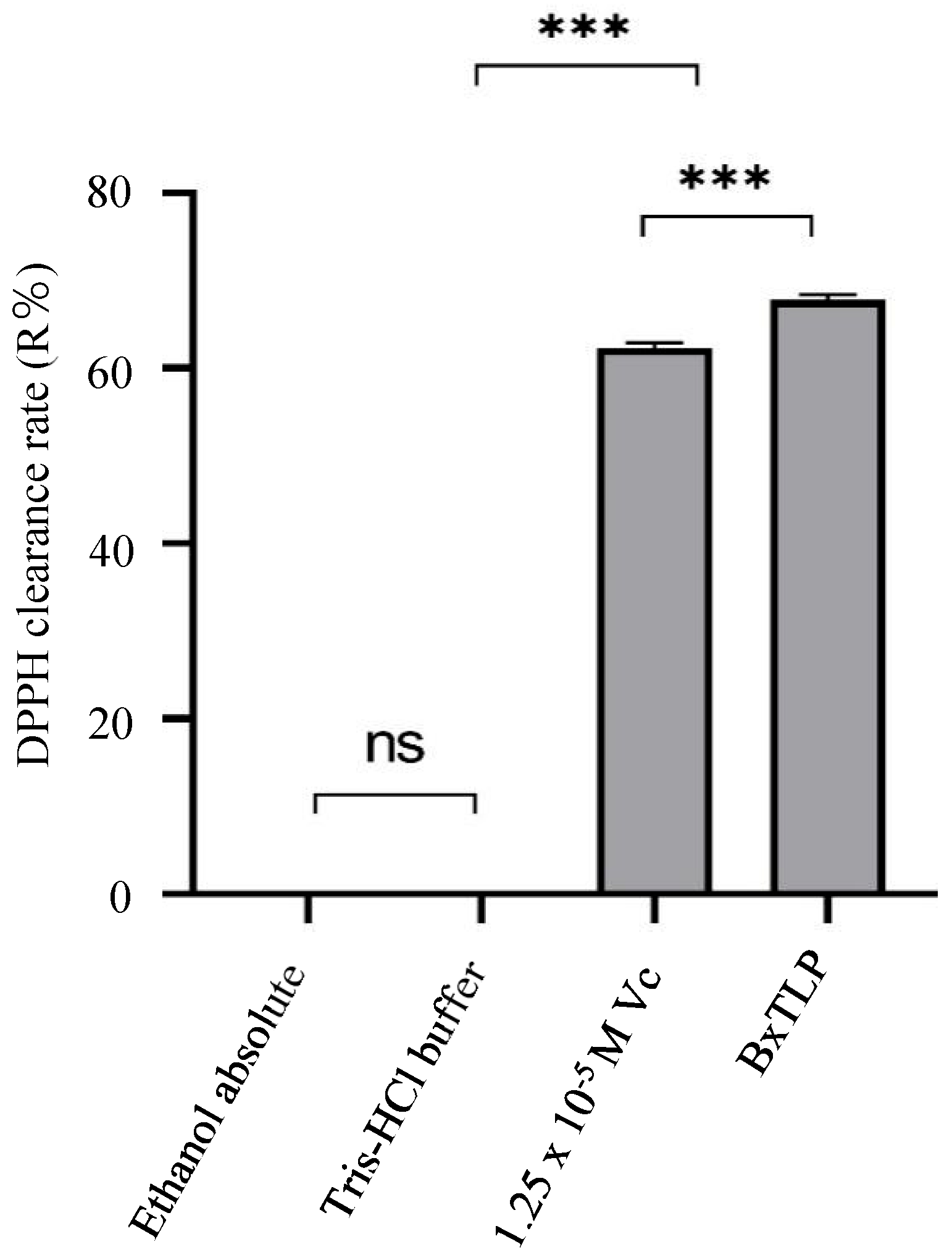

3.3. Determination of Antioxidant Activity of Recombinant BxTLP

The DPPH clearance rate of the recombinant BxTLP was 67.9%, similar to that of 12.5μM Vc (61.71%) (

Figure 5), which indicated that the recombinant protein had strong antioxidant activity and could effectively remove free radicals [

44].

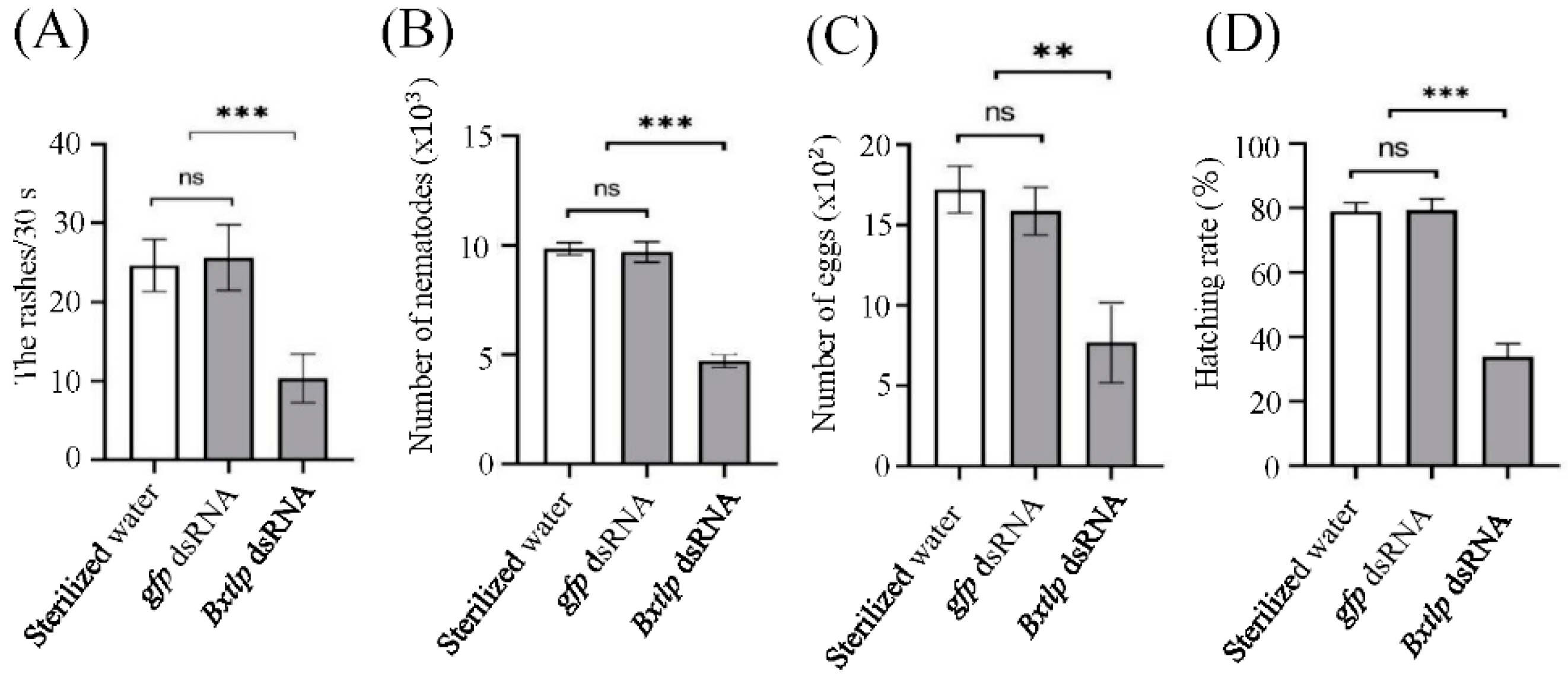

3.4. Bxtlp dsRNA Can Effect PWN Vitality

The head oscillation times of PWNs treated by

Bxtlp dsRNA solution was 10.87 ± 3.45 per 30 s, while the ones treated by sterilized water and

gfp dsRNA solution were 25.41 ± 3.58 and 25.63 ± 4.13 per 30 s, respectively (

Figure 6A). The results showed that

Bxtlp dsRNA could significantly reduce the motility ability of PWN.

After 9 d, the collected nematodes in

Bxtlp dsRNA, sterilized water and gfp dsRNA groups were 4,713± 270, 9,839 ± 249, and 9,696± 412, respectively (

Figure 6B), which indicated

Bxtlp played an import role on the PWN reproduction.

After 48 h, the eggs laid by the PWNs treated by the

Bxtlp dsRNA, sterilized water and

gfp dsRNA were 7.69 ± 2.16, 17.21 ± 1.25 and 15.86 ± 1.29, respectively (

Figure 6C). In addition, the hatching rates of the PWNs soaked in

Bxtlp dsRNA, sterilized water and

gfp dsRNA were 33.81%, 78.98% ± 2.66% and 79.29% ± 3.61%, respectively (

Figure 6D). The results showed that

Bxtlp dsRNA markedly decreased the oviposition and hatching ability of PWN.

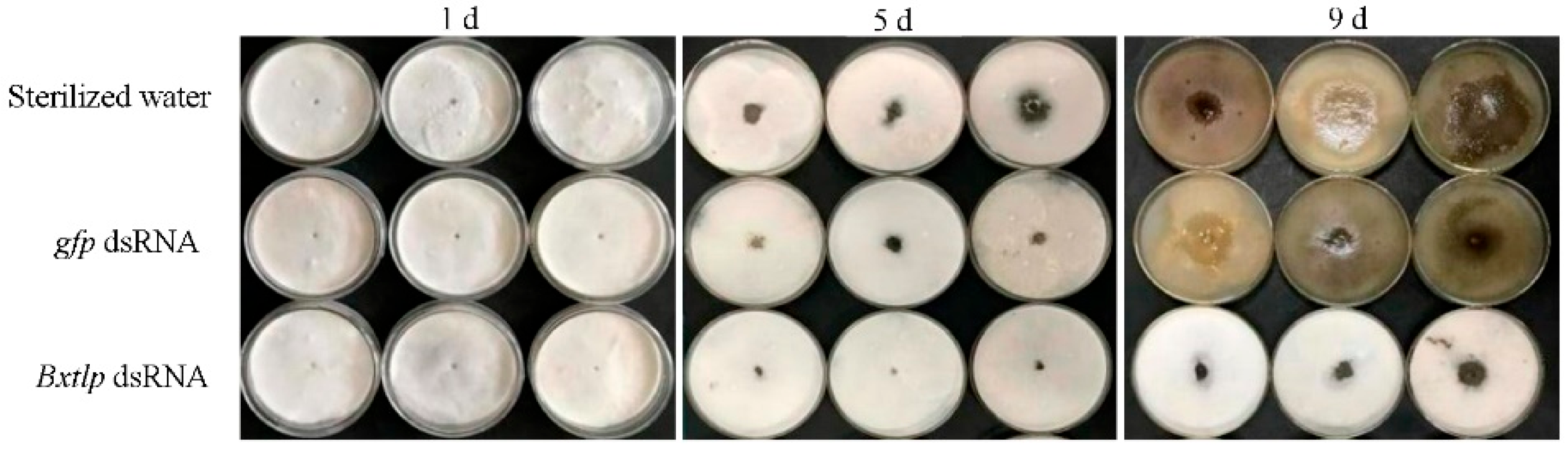

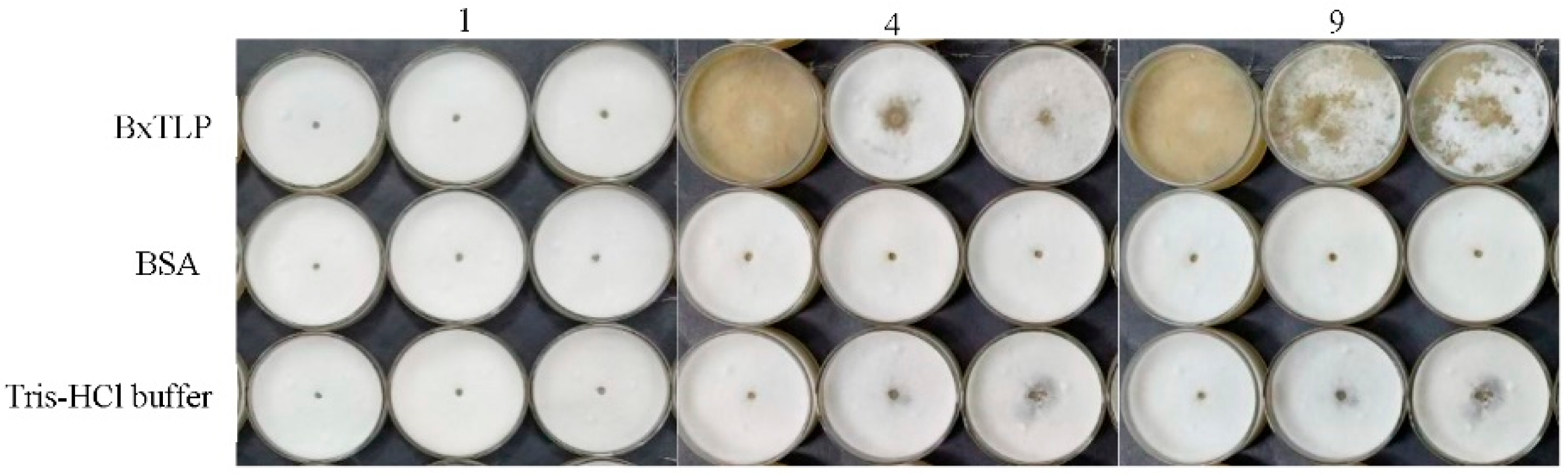

PWNs treated by

Bxtlp dsRNA,

gfp dsRNA and sterilized water for 72 h were cultured on PDA plate covered with

B. cinerea. The feeding ability of the

Bxtlp dsRNA group was significantly lower than those of the control groups. On the 9th day, almost all of

B. cinerea in the sterilized water and

gfp dsRNA group had been consumed, while only a little of

B. cinerea in the

Bxtlp dsRNA group had been consumed (

Figure 7).

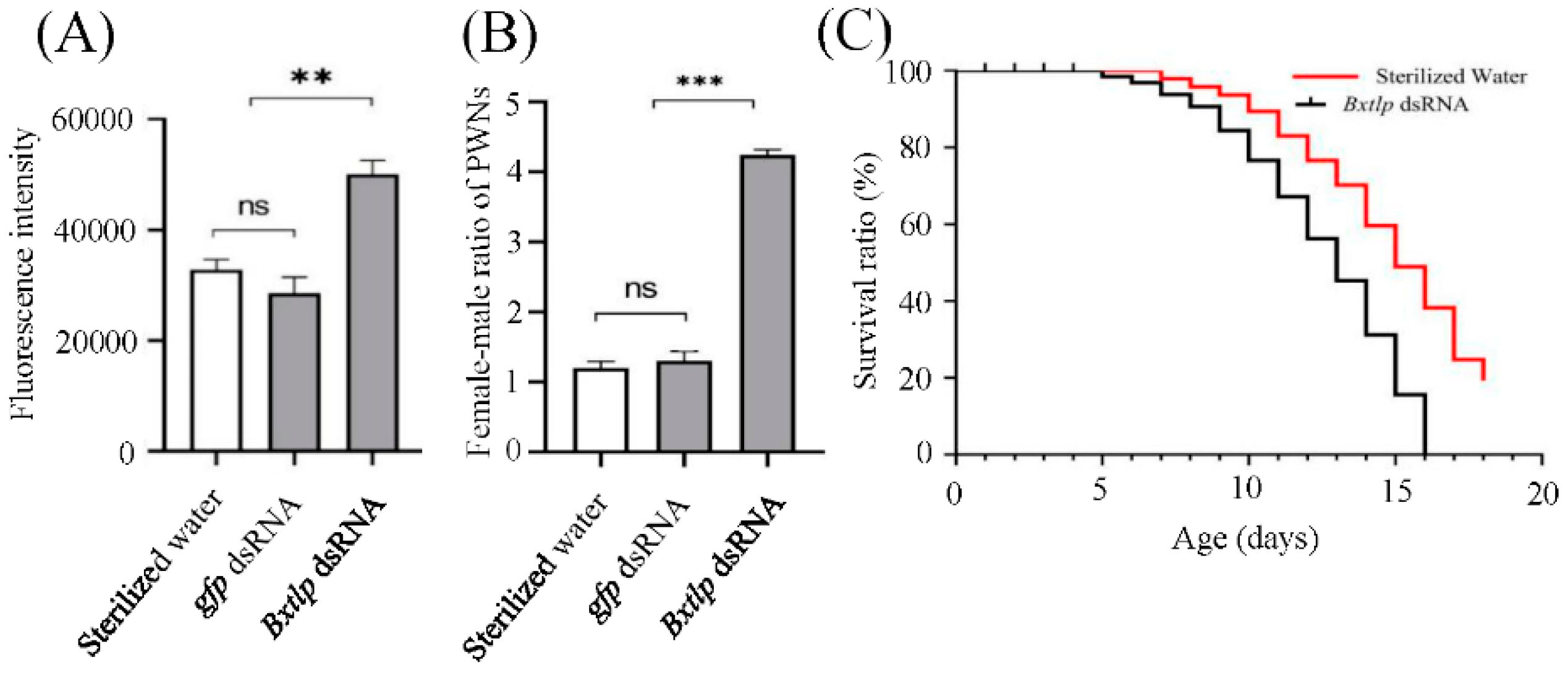

3.5. Effects of Bxtlp dsRNA on ROS Content, Life-Span and Female-Male Ratio of PWN

The fluorescence intensity of ROS in PWNs after

Bxtlp dsRNA immersion was higher than those in the control groups (

Figure 8A). The female-male ratio of PWNs in the

Bxtlp dsRNA treatment group was 5, while the ratios of

gfp dsRNA and sterilized water in the control group were 1.3 and 1.5, respectively (

Figure 8B). Furthermore, the life span of PWN was investigated, and the results showed it took 15 days for the PWNs soaked in

Bxtlp dsRNA solution to reach the mortality of 80%, while it took 19 days for the ones soaked in sterilized water to reached the same mortality, which demonstrated that the life span of PWN was shortened after

Bxtlp interference (

Figure 8C).

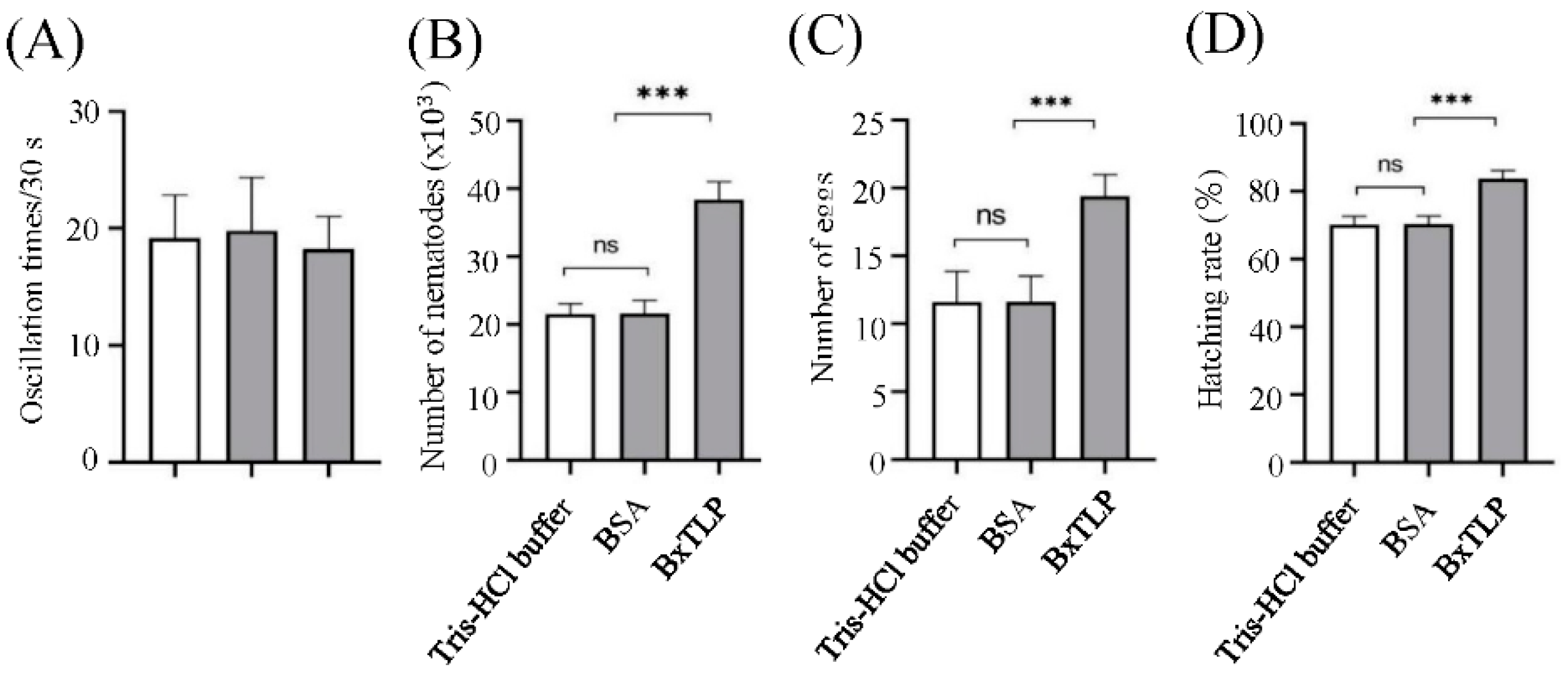

3.6. Effect of Recombinant BxTLP on PWN

The recombinant BxTLP had no significant effect on the motility ability of PWN (

Figure 9A). After 9 d, the collected PWNs from

Bxtlp dsRNA, sterilized water and

gfp dsRNA groups were 38400, 21,540 and 21600, respectively (

Figure 9B), indicating that recombinant BxTLP could significantly enhance the reproductive capacity of PWN. The eggs collected from Tris-HCl buffer group, BSA group and recombinant BxTLP group were 10, 11 and 19, respectively (

Figure 9C), and the corresponding hatching rates were 70.14%, 70.28% and 83.74%, respectively (

Figure 9D). The feeding assays demonstrated that recombinant BxTLP could enhance the feeding capacity of PWN (

Figure 10).

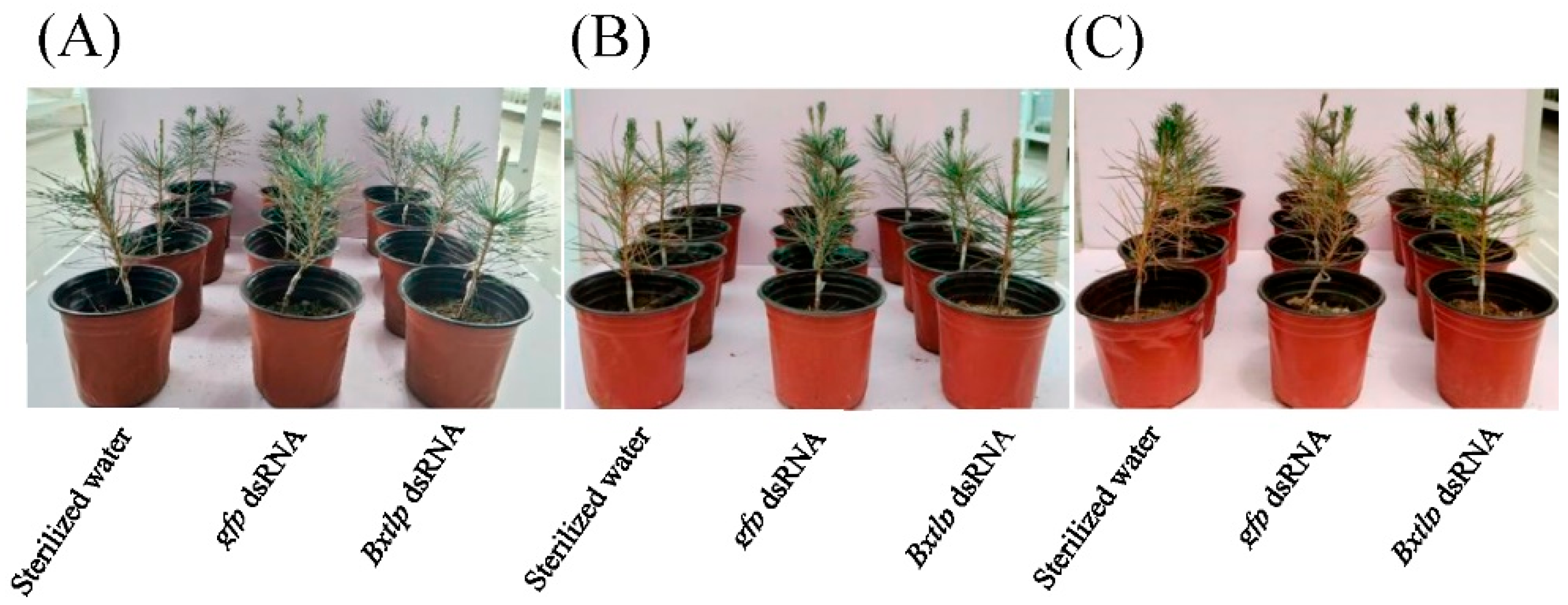

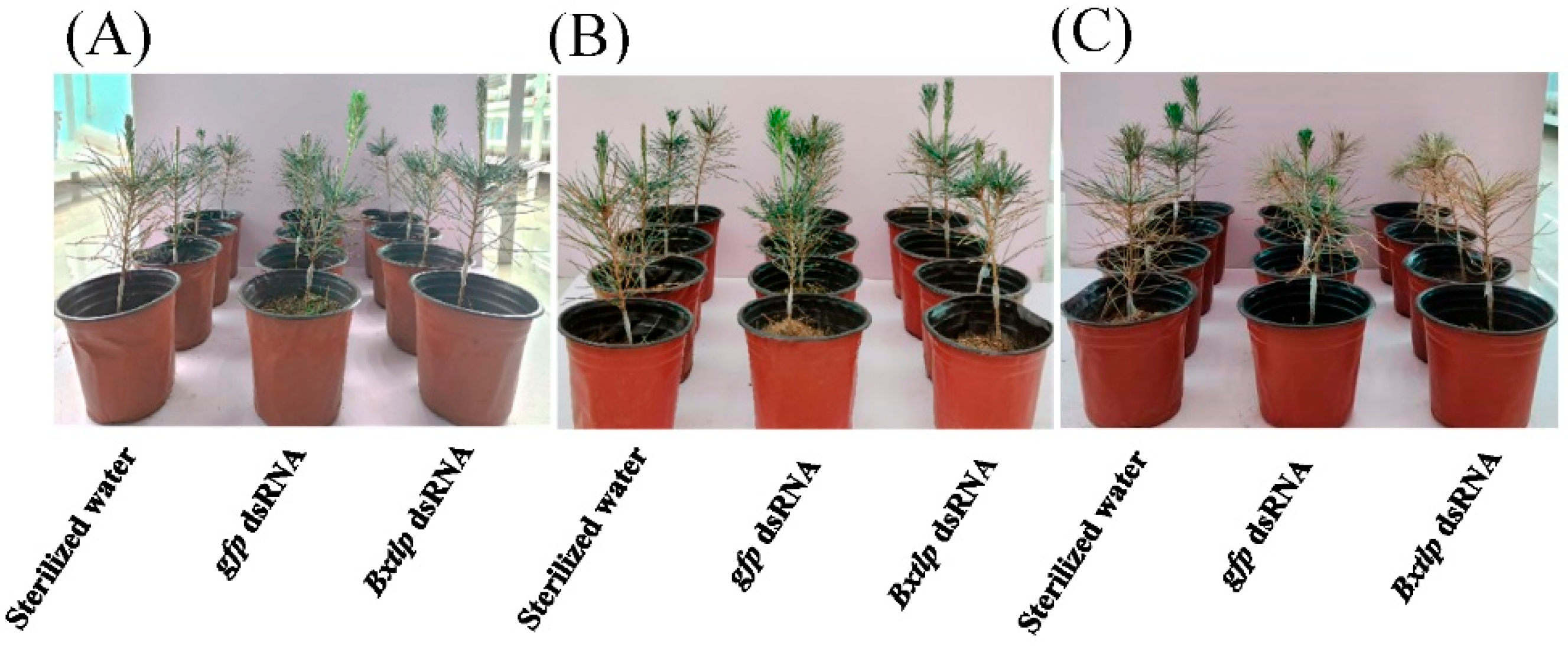

3.7. Bxtlp Affects the Pathogenicity of PWN

PWNs soaked in

Bxtlp dsRNA solution, sterilized water and

gfp dsRNA solution for 72 h were inoculated into 1-year-old saplings to determine the pathogenicity of PWN. The virulence of the PWNs treated with

Bxtlp dsRNA was significantly weaker than those of the control PWNs treated with sterilized water and

gfp dsRNA. Specifically, the saplings in the sterilized water group and

gfp dsRNA group started wilting 10 days post inoculation (dpi), while the ones of

Bxtlp dsRNA group had no wilt symptom (

Figure 11). On 20 dpi, the saplings in both control groups had severely withered, whereas saplings treated with

Bxtlp dsRNA began to show slight wilt symptom.

PWNs treated by recombinant BxTLP solution, Tris-HCl buffer and BSA solution for 24 h were inoculated into 1-year-old saplings. On 5 dpi, the saplings inoculated with recombinant BxTLP-treated PWNs began to wilt. At the same time, the Tris-HCl buffer and BSA treated groups had no wilt symptoms. On 11 dpi, the Tris-HCl buffer and BSA treated groups began to show slight wilt symptoms. Most of the saplings in the recombinant BxTLP-treated group had completely withered at 14 days, while the ones in the Tris-HCl buffer and BSA treatment groups were still alive (

Figure 12).

The aforementioned results indicated that Bxtlp could significantly affect the pathogenicity of PWNs.

4. Discussion

PWD management has been increasingly urgent because of its rapid spread and difficult control, and nematicide treatment is considered as one of the most effective methods to prevent PWD [

43]. Finding novel target gene for the development of high-effciency nematicides against PWN has become a prospective research focus due to occurrence of drug resistance. Wang et al. reported that three cytochrome P450 genes played a critical role in the low-temperature resistance mechanism of PWN [

45]. In our previous study,

sft-4 was found to affect the pathogenicity of PWN by influencing the motility, reproduction and development of PWN [

46].

TLP widely exists in plants and has various biological activities including antifungal activity, glucanase activity and anti-abiotic stresses [

8,

47]. In this study, amino acid sequence prediction showed that the recombinant BxTLP contained 6 cysteine residues with reducing ability and 50 metal ion-chelating residues, accounting for 4.62% and 38.46% of total amino acid residues, respectively. We speculated the metal ion-chelating amino acid residues maybe decrease free Fe

2+ ions to inhibit the Harber-Weiss reaction and reduce hydroxyl radical content [

48,

49]. Coincidentally, ROS content in

Bxtlp dsRNA-treated PWNs was higher than controls, and the recombinant BxTLP had antioxidant activity

in vitro by DPPH assay. Furthermore, the results of

Bxtlp RNAi and BxTLP overexpression in PWNs showed that the BxTLP could significantly enhance the reproductive capacity, lifespan, feeding ability and pathogenicity of PWN. Herein, we speculated that BxTLP could strengthen PWN vitality and pathogenicity by scavenging free radical to improve anti-stress of PWN.

Overall, Bxtlp was a key pathogenic gene and could be used as a potential drug target to develop new nematicides to PWN control.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.L., R.L., and G.D.; Methodology, S.L., R.L., G.D. and Q.G.; Software, S.L.; Validation, R.L., G.D. and Q.G.; Formal Analysis, S.L.; Investigation, S.L., Y.Z., W.F.; Resources, R.L., G.D. and Q.G.; Data Curation, S.L., R.L., G.D. and Q.G.; Writing - Original Draft Preparation, S.L.; Writing - Review & Editing, R.L., G.D. and Q.G.; Visuali-zation, S.L., W.Z.; Supervision, R.L., G.D. and Q.G.; Project Administration, R.L., G.D. and Q.G.; Funding Acquisition, R.L. and Q.G.

Funding

This work was financially supported by Qingdao Natural Science Foundation (24-4-4-zrjj-183-jch) and Qingdao Municipal Pepole-benefitting Demonstration Project of Science and Technology, China (23-2-8-cspz-7-nsh).

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no new data were created or analyzed in this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- J.M. Rodrigues. Pine Wilt Disease: A Worldwide Threat to Forest Ecosystems. Springer Netherlands, 2008.

- L.S. Wang, T.T. Zhang, Z.S. Pan, L.L. Lin, G.Q. Dong, M. Wang, R.G. Li. The alcohol dehydrogenase with a broad range of substrate specificity regulates vitality and reproduction of the plant-parasitic nematode Bursaphelenchus xylophilus. Parasitology 2019, 146(4), 497-505. [CrossRef]

- K. Futai. Pine wood nematode, Bursaphelenchus xylophilus. Annu Rev Phytopathol 2013, 51, 61-83.

- K. Takai, T. Suzuki, K. Kawazu. Development and preventative effect against pine wilt disease of a novel liquid formulation of emamectin benzoate. Pest Management ence 2003, 59(3), 365-370.

- S.C. Lee, H.R. Lee, D.S. Kim, J.H. Kwon, M.J. Huh, I.K. Park. Emamectin benzoate 9.7% SL as a new formulation for a trunk-injections against pine wood nematode, Bursaphelenchus xylophilus. Journal of Forestry Research 2020, 31 (4), 1399-1403. [CrossRef]

- S. Gnanendra, L. Sun, J. Junhyun. Identification of Potential Nematicidal Compounds against the Pine Wood Nematode, Bursaphelenchus xylophilus through an In Silico Approach. Molecules 2018, 23(7), 1828.

- M.i. Liu, B.o. Hwang, C.h. Jin, W.u. Li, D.i. Park, S.a. Seo, C.i. Kim. Screening, isolation and evaluation of a nematicidal compound from actinomycetes against the pine wood nematode. Pest Management Science 2019, 75(6), 1585-1593.

- J.J. Liu, R. Sturrock, A.K.M. Ekramoddoullah. The superfamily of thaumatin-like proteins: its origin, evolution, and expression towards biological function. Plant Cell Reports 2010, 29(5), 419-436.

- V.S.M. Ho, J.H. Wong, T.B. Ng. A thaumatin-like antifungal protein from the emperor banana. Peptides 2007, 28(4), 760-766. [CrossRef]

- H. Wel, K. Loeve. Isolation and characterization of thaumatin I and II, the sweet-tasting proteins from Thaumatococcus daniellii Benth. European Journal of Biochemistry 2010, 31(2), 221-225.

- M. Zhang, J.H. Xu, G. Liu, X.P. Yang. Antifungal properties of a thaumatin-like protein from watermelon. Acta Physiologiae Plantarum 2018, 40(11), 186.

- C. Garcia-Casado, C. Collada, I. Allona, A. Soto, R. Casado, E. Rodriguez-Cerezo, L. Gomez, C. Aragoncillo. Characterization of an apoplastic basic thaumatin-like protein from recalcitrant chestnut seeds. Physiologia Plantarum 2000, 110(2), 172-180.

- K.T. Chu, T.B. Ng. Isolation of a large thaumatin-like antifungal protein from seeds of the Kweilin chestnut Castanopsis chinensis. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications 2003, 301(2), 364-370. [CrossRef]

- S. Jayasankar, Z.J. Li, D.J. Gray. Constitutive expression of Vitis vinifera thaumatin-like protein after in vitro selection and its role in anthracnose resistance. Functional Plant Biology 2003, 30(11), 1105-1115.

- E. Fierens, S. Rombouts, K. Gebruers, H. Goesaert, K. Brijs, J. Beaugrand, G. Volckaert, S. Van Campenhout, P. Proost, C.M. Courtin, J.A. Delcour. TLXI, a novel type of xylanase inhibitor from wheat (Triticum aestivum) belonging to the thaumatin family. Biochemical Journal 2007, 403, 583-591.

- C. Bormann, D. Baier, I. Hörr, C. Raps, J. Berger, G. Jung, H. Schwarz. Characterization of a novel, antifungal, chitin-binding protein from Streptomyces tendae Tu901 that interferes with growth polarity. Journal of Bacteriology 1999, 181(24), 7421-7429.

- R.I.W. Osmond, M. Hrmova, F. Fontaine, A. Imberty, G.B. Fincher. Binding interactions between barley thaumatin-like proteins and (1,3)-β-D-glucans -: Kinetics, specificity, structural analysis and biological implications. European Journal of Biochemistry 2001, 268(15), 4190-4199.

- X.M. Yu, M. Griffith, Antifreeze proteins in winter rye leaves form oligomeric complexes. Plant Physiology 1999, 119(4), 1361-1369.

- V. Parkhi, V. Kumar, G. Sunilkumar, L.M. Campbell, N.K. Singh, K.S. Rathore. Expression of apoplastically secreted tobacco osmotin in cotton confers drought tolerance. Molecular Breeding 2009, 23(4), 625-639. [CrossRef]

- A.M. Husaini, M.Z. Abdin. Development of transgenic strawberry (Fragaria x ananassa Duch.) plants tolerant to salt stress. Plant Science 2008, 174(4), 446-455.

- S. Kitajima, F. Sato. Plant pathogenesis-related proteins: Molecular mechanisms of gene expression and protein function. Journal of Biochemistry 1999, 125(1), 1-8.

- A. Brandazza, S. Angeli, M. Tegoni, C. Cambillau, P. Pelosi. Plant stress proteins of the thaumatin-like family discovered in animals. Febs Letters 2004, 572(1-3), 3-7.

- A. Fire, S.Q. Xu, M.K. Montgomery, S.A. Kostas, S.E. Driver, C.C. Mello. Potent and specific genetic interference by double-stranded RNA in Caenorhabditis elegans. Nature 1998, 391(6669), 806-811. [CrossRef]

- C.L. Chi-Ham, K.L. Clark, A.B. Bennett. The intellectual property landscape for gene suppression technologies in plants. Nature Biotechnology 2010, 28(1), 32-37.

- J.H. Niu, H. Jian, J.M. Xu, Y.D. Guo, Q.A. Liu. RNAi technology extends its reach: Engineering plant resistance against harmful eukaryotes. African Journal of Biotechnology 2010, 9(45), 7573-7582.

- M. Wang, D.D. Wang, X. Zhang, X. Wang, W.C. Liu, X.M. Hou, X.Y. Huang, B.Y. Xie, X.Y. Cheng. Double-stranded RNA-mediated interference of dumpy genes in Bursaphelenchus xylophilus by feeding on filamentous fungal transformants. International Journal for Parasitology 2016, 46(5-6), 351-360. [CrossRef]

- X.Y. Cheng, S.M. Dai, L. Xiao, B.Y. Xie. Influence of cellulase gene knockdown by dsRNA interference on the development and reproduction of the pine wood nematode, Bursaphelenchus xylophilus. Nematology 2010, 12, 225-233.

- Q. Zhao, L.J. Hu, X.Q. Wu, Y.C. Wang. A key effector, BxSapB2, plays a role in the pathogenicity of the pine wood nematode Bursaphelenchus xylophilus. Forest Pathology 2020, 50(3), e12600. [CrossRef]

- D.R. Viglierchio, R.V. Schmitt. On the methodology of nematode extraction from field samples: baermann funnel modifications, Journal of nematology 1983, 15(3), 438-44.

- Q.Q. Guo, G.C. Du, H.T. Qi, Y.A. Zhang, T.Q. Yue, J.C. Wang, R.G. Li. A nematicidal tannin from Punica granatum L. rind and its physiological effect on pine wood nematode (Bursaphelenchus xylophilus). Pesticide Biochemistry and Physiology 2017, 135, 64-68.

- L. Xu, B.J. Liu, Z.Y. Liu, Q. Lu, X.Y. Zhang. Behavioural features of Bursaphelenchus xylophilus in the matingprocess. Nematology 2014, 16(8), 895-902.

- N.J. Zhu, L.Q. Bai, S. Schütz, B.J. Liu, Z.Y. Liu, X.Y. Zhang, H.S. Yu, J.F. Hu. Observation and Quantification of Mating Behavior in the Pinewood Nematode, Bursaphelenchus xylophilus. Jove-Journal of Visualized Experiments 2016, (118), e54842.

- J. Tang, R.Q. Ma, N.J. Zhu, K. Guo, Y.Q. Guo, L.Q. Bai, H.S. Yu, J.F. Hu, X.Y. Zhang. Bxy-fuca encoding α-L-fucosidase plays crucial roles in development and reproduction of the pathogenic pinewood nematode, Bursaphelenchus xylophilus. Pest Management Science 2020, 76(1), 205-214. [CrossRef]

- R. Shinya, Y. Takeuchi, N. Miura, K. Kuroda, M. Ueda, K. Futai. Surface coat proteins of the pine wood nematode, Bursaphelenchus xylophilus: profiles of stage- and isolate-specific characters. Nematology 2009, 11, 429-438.

- M. Wang, G.C. Du, J.N. Fang, L.S. Wang, Q.Q. Guo, T.T. Zhang, R.G. Li. UGT440A1 Is Associated With Motility, Reproduction, and Pathogenicity of the Plant-Parasitic Nematode Bursaphelenchus xylophilus. Frontiers in Plant Science 2022, 13, 862594. [CrossRef]

- X.L. Zhang, X.L. Huang, J. Li, M. Mei, W.Q. Zeng, X.J. Lu. Evaluation of the RNA extraction methods in different Ginkgo biloba L. tissues. Biologia 2021, 76(8), 2393-2402.

- X. Zhou, S.N. Chen, F. Lu, K. Guo, L.L. Huang, X. Su, Y. Chen. Nematotoxicity of a Cyt-like protein toxin from Conidiobolus obscurus (Entomophthoromycotina) on the pine wood nematode Bursaphelenchus xylophilus. Pest Management Science 2021, 77(2) 686-692.

- X.L. Xu, X.Q. Wu, J.R. Ye, L. Huang. Molecular Characterization and Functional Analysis of Three Pathogenesis-Related Cytochrome P450 Genes from Bursaphelenchus xylophilus (Tylenchida: Aphelenchoidoidea). International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2015, 16(3), 5216-5234. [CrossRef]

- L. Huang, P. Wang, M.Q. Tian, L.H. Zhu, J.R. Ye. Major sperm protein BxMSP10 is required for reproduction and egg hatching in Bursaphelenchus xylophilus. Experimental Parasitology 2019, 197, 51-56.

- J.E. Park, K.Y. Lee, S.J. Lee, W.S. Oh, P.Y. Jeong, T. Woo, C.B. Kim, Y.K. Paik, H.S. Koo. The efficiency of RNA interference in Bursaphelenchus xylophilus. Molecules and Cells 2008, 26(1), 81-86. [CrossRef]

- X.C. Li, Y.X. Gao, F. Li, A.F. Liang, Z.M. Xu, Y. Bai, W.Q. Mai, L. Han, D.F. Chen. Maclurin protects against hydroxyl radical-induced damages to mesenchymal stem cells: Antioxidant evaluation and mechanistic insight. Chemico-Biological Interactions 2014, 219, 221-228.

- L.I. Xuanjun, C.U.I. Shengyun. DPPH Radical Scavenging Mechanism of Ascorbic Acid. Food Science 2011, 32(1), 86-90.

- X.W. Qiu, X.Q. Wu, L. Huang, J.R. Ye. Influence of Bxpel1 Gene Silencing by dsRNA Interference on the Development and Pathogenicity of the Pine Wood Nematode, Bursaphelenchus xylophilus. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2016, 17(1), 125.

- X.C. Li. Comparative Study of 1,1-Diphenyl-2-picryl-hydrazyl Radical (DPPH•) Scavenging Capacity of the Antioxidant Xanthones Family. Chemistryselect 2018, 3(46), 13081-13086.

- B.W. Wang, X. Hao, J.Y. Xu, B.Y. Wang, W. Ma, X.F. Liu, L. Ma. Cytochrome P450 metabolism mediates low-temperature resistance in pinewood nematode. Febs Open Bio 2020, 10(6), 1171-1179.

- S.S. Liu, L.S. Wang, R.G. Li, M.Y. Chen, W.J. Deng, C. Wang, G.C. Du, Q.Q. Guo. Cloning of sft-4 and its influence on vitality and virulence of pine wood nematode, Bursaphelenchus xylophilus. Journal of Forestry Research 2024, 35(1), 43.

- C. Kuwabara, D. Takezawa, T. Shimada, T. Hamada, S. Fujikawa, K. Arakawa. Abscisic acid- and cold-induced thaumatin-like protein in winter wheat has an antifungal activity against snow mould, Microdochium nivale. Physiologia Plantarum 2002, 115(1), 101-110. [CrossRef]

- J.P. Kehrer. The Haber-Weiss reaction and mechanisms of toxicity. Toxicology 2000, 149(1), 43-50.

- S.I. Liochev, I. Fridovich. The Haber-Weiss cycle - 70 years later: an alternative view. Redox Report 2002, 7(1), 55-57.

Figure 1.

Bioinformatic analysis of Bxtlp. (A) Genomic DNA structure of Bxtlp. The lines represent introns, and the black parts represent to exons. (B) Nucleotide and deduced amino acid sequence of Bxtlp from pine wood nematodes (PWNs). (C) Alignment of the amino acid sequences of BxTLP from Bursaphelenchus xylophilus, Bursaphelenchus okinawaensis, Hypsibius exemplaris, Pinus monticola, Apophysomyces ossiformis,and Pinus massoniana. Colors indicate conserved amino acid residues. (D) Predicted BxTLP signal peptide. (E) Predicted BxTLP transmembrane structure.

Figure 1.

Bioinformatic analysis of Bxtlp. (A) Genomic DNA structure of Bxtlp. The lines represent introns, and the black parts represent to exons. (B) Nucleotide and deduced amino acid sequence of Bxtlp from pine wood nematodes (PWNs). (C) Alignment of the amino acid sequences of BxTLP from Bursaphelenchus xylophilus, Bursaphelenchus okinawaensis, Hypsibius exemplaris, Pinus monticola, Apophysomyces ossiformis,and Pinus massoniana. Colors indicate conserved amino acid residues. (D) Predicted BxTLP signal peptide. (E) Predicted BxTLP transmembrane structure.

Figure 2.

Unrooted phylogenetic analysis of BxTLP protein. The scale bar indicates the.evolutionary distance (0.2 substitutions per position).

Figure 2.

Unrooted phylogenetic analysis of BxTLP protein. The scale bar indicates the.evolutionary distance (0.2 substitutions per position).

Figure 3.

Predicted structure of BxTLP. (A) Secondary structure prediction of BxTLP. (B) Three-dimensional structure of BxTLP. (C) The electrostatic potential surface of BxTLP. The color gradient ranging from red to blue corresponds to negatively charged regions (−5KBT/e) to positively charged regions (+ 5 KBT/e), and white color indicates neutral regions.

Figure 3.

Predicted structure of BxTLP. (A) Secondary structure prediction of BxTLP. (B) Three-dimensional structure of BxTLP. (C) The electrostatic potential surface of BxTLP. The color gradient ranging from red to blue corresponds to negatively charged regions (−5KBT/e) to positively charged regions (+ 5 KBT/e), and white color indicates neutral regions.

Figure 4.

SDS-PAGE analyses of expression and purification of recombinant BxTLP. (A) Expressed recombinant BxTLP. Lane 1: Total proteins of E. coli BL21 (DE3); lane 2: Total proteins of E. coli BL21 (DE3) harboring pET-15b-Bxtlp. () SDS-PAGE analysis of purified recombinant BxTLP. Lane 1: Total proteins of E. coli BL21 (DE3) harboring pET-15b-Bxtlp; lane 2: supernatant; lane 3: cell lysate precipitation; lane 4: purified recombinant protein.

Figure 4.

SDS-PAGE analyses of expression and purification of recombinant BxTLP. (A) Expressed recombinant BxTLP. Lane 1: Total proteins of E. coli BL21 (DE3); lane 2: Total proteins of E. coli BL21 (DE3) harboring pET-15b-Bxtlp. () SDS-PAGE analysis of purified recombinant BxTLP. Lane 1: Total proteins of E. coli BL21 (DE3) harboring pET-15b-Bxtlp; lane 2: supernatant; lane 3: cell lysate precipitation; lane 4: purified recombinant protein.

Figure 5.

Antioxidant activity of recombinant BxTLP.

Figure 5.

Antioxidant activity of recombinant BxTLP.

Figure 6.

Effects of Bxtlp dsRNA on motility (A), reproduction (B), oviposition (C) and percentage of eggs that hatched (D) of pine wilt nematodes (PWNs). Control treatments: gfp dsRNA and Sterilzed water.

Figure 6.

Effects of Bxtlp dsRNA on motility (A), reproduction (B), oviposition (C) and percentage of eggs that hatched (D) of pine wilt nematodes (PWNs). Control treatments: gfp dsRNA and Sterilzed water.

Figure 7.

Effect of Bxtlp dsRNA on feeding of Botrytis cinerea in petri dishes by pine wilt nematodes (PWNs) at 1, 5 and 9 days after treatment. Control treatments: gfp dsRNA and Sterilzed water.

Figure 7.

Effect of Bxtlp dsRNA on feeding of Botrytis cinerea in petri dishes by pine wilt nematodes (PWNs) at 1, 5 and 9 days after treatment. Control treatments: gfp dsRNA and Sterilzed water.

Figure 8.

Effects of Bxtlp dsRNA on ROS levels (A), lifespan (B), and female-male ratio (C) of pine wilt nematodes (PWNs). Control treatments: gfp dsRNA and Sterilzed water. level of significance: **P < 0.005, ***P < 0.001.

Figure 8.

Effects of Bxtlp dsRNA on ROS levels (A), lifespan (B), and female-male ratio (C) of pine wilt nematodes (PWNs). Control treatments: gfp dsRNA and Sterilzed water. level of significance: **P < 0.005, ***P < 0.001.

Figure 9.

Effect of recombinant BxTLP on motility (A), reproduction (B), oviposition(C) and egg hatching (D). Control treatments: Tris-HCl buffer, BSA. Means were tested for significant differences using Student’s t- test; bars on means are standard errors; level of significance: ***P < 0.001, ns, not significant.

Figure 9.

Effect of recombinant BxTLP on motility (A), reproduction (B), oviposition(C) and egg hatching (D). Control treatments: Tris-HCl buffer, BSA. Means were tested for significant differences using Student’s t- test; bars on means are standard errors; level of significance: ***P < 0.001, ns, not significant.

Figure 10.

Effects of recombinant BxTLP on feeding of Botrytis cinerea in petri dishes by pine wilt nematodes (PWNs) on 1, 4 and 9 days after treatment. Control treatments: BSA and Tris-HCl.

Figure 10.

Effects of recombinant BxTLP on feeding of Botrytis cinerea in petri dishes by pine wilt nematodes (PWNs) on 1, 4 and 9 days after treatment. Control treatments: BSA and Tris-HCl.

Figure 11.

Pathogenicity of PWNs treated with Bxtlp dsRNA on saplings of Pinus thunbergii at different days post inoculation (dpi). (A) 1 dpi, (B) 10 dpi, (C) 20 dpi. Control treatments: Sterilized water and gfp dsRNA.

Figure 11.

Pathogenicity of PWNs treated with Bxtlp dsRNA on saplings of Pinus thunbergii at different days post inoculation (dpi). (A) 1 dpi, (B) 10 dpi, (C) 20 dpi. Control treatments: Sterilized water and gfp dsRNA.

Figure 12.

Pathogenicity of PWNs treated with recombinant BxTLP on saplings of Pinus thunbergii at different days post inoculation (dpi). (A) 1 dpi, (B) 5 dpi, (C) 14 dpi. Control treatments: Sterilized water and gfp dsRNA.

Figure 12.

Pathogenicity of PWNs treated with recombinant BxTLP on saplings of Pinus thunbergii at different days post inoculation (dpi). (A) 1 dpi, (B) 5 dpi, (C) 14 dpi. Control treatments: Sterilized water and gfp dsRNA.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).