3.1. Understanding the Lucky Pick Lottery

The Lucky Pick is a seven-day-a-week Lottery, operated across several Caribbean jurisdictions, is a widely played numerical lottery game characterized by its simple format and broad popular appeal. Each ticket costs $1. The game matrix follows a 5/28 format, meaning players must select 5 numbers from a pool of 28 possible balls. Additionally, the lottery incorporates multipliers ranging from 2x to 5x, which enhance the payout amounts for secondary prize tiers corresponding to matches of r = 3 and r = 4.

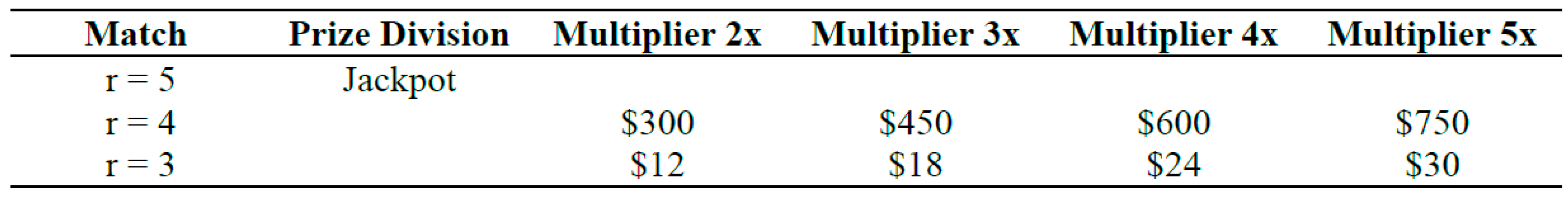

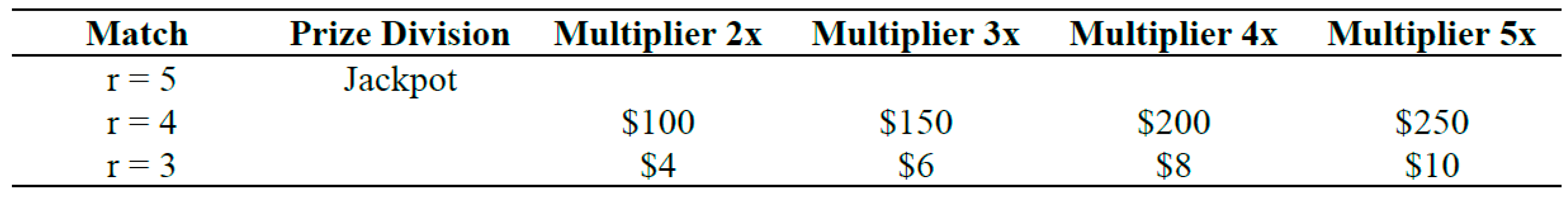

Accordingly, the maximum probability of winning the jackpot is 1 in 98,280 possible combinations. The following tables present the distinct prize structures for two major Caribbean regions, which, for technical and methodological purposes, will be referred to as Box 1 (Anguilla / Antigua / St. Kitts & Nevis) and Box 2 (St. Maarten / US Virgin Islands / Bermuda), respectively.

Table 1.

Anguilla / Antigua / St. Kitts & Nevis Payout.

Table 1.

Anguilla / Antigua / St. Kitts & Nevis Payout.

Table 2.

St. Maarten / US Virgin Islands / Bermuda Payout Table.

Table 2.

St. Maarten / US Virgin Islands / Bermuda Payout Table.

In the context of the Sirius Code, this case study employs the method of partial coverage with concentrated density, using m = 11. That is, all possible combinations of a strategically optimized subset of numbers (from 1 to 11) are generated, with each ticket containing 5 numbers. This fixed set is repeatedly played across multiple draws. Applying basic combinatorial principles, this strategy requires the purchase of only 462 tickets, representing just 0.47% of the total 98,280 possible combinations in the full lottery matrix.

As shown in

Table 3, within the 462 possible tickets derived from the selected subset, a total of 181 tickets would be winning entries assuming that the drawn numbers fall within the chosen range of 1 to 11. The following sections present the cost-benefit analysis, calculated as the aggregate value of prizes minus the total ticket expenses, across the different prize tiers for both Box 1 (Anguilla / Antigua / St. Kitts & Nevis) and Box 2 (St. Maarten / US Virgin Islands / Bermuda).

Table 3.

Expected winner tickets by prize tier (based on number of r matches) with m = 11.

Table 3.

Expected winner tickets by prize tier (based on number of r matches) with m = 11.

| Matches |

N° of Success Tickets |

| 5 |

1 |

| 4 |

30 |

| 3 |

150 |

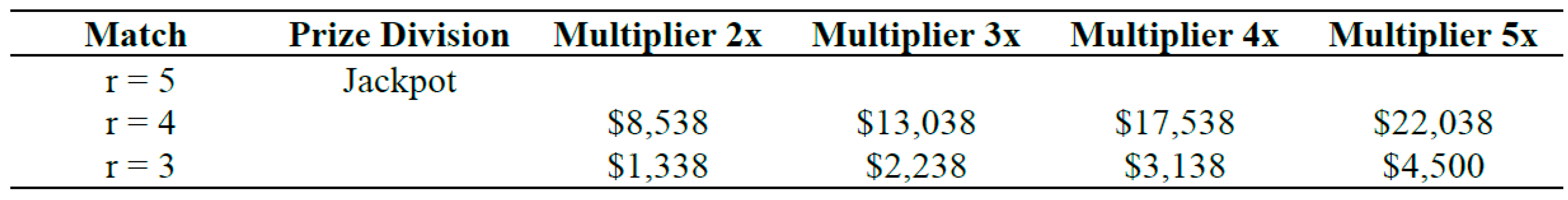

Table 4.

Box 1 Cost-benefit analysis by match category under the partial coverage with concentrated density with m = 11.

Table 4.

Box 1 Cost-benefit analysis by match category under the partial coverage with concentrated density with m = 11.

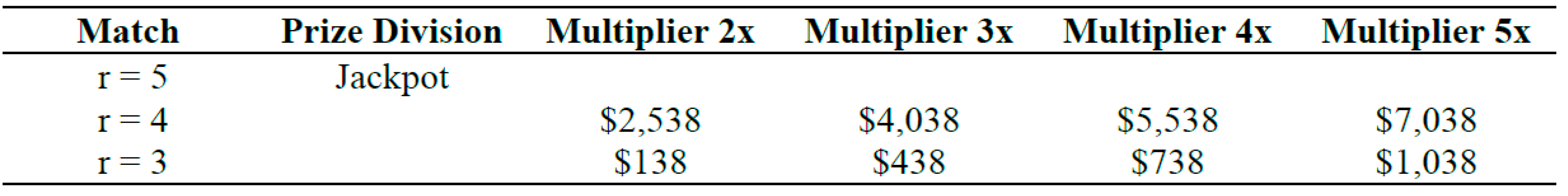

Table 5.

Box 2

Cost-benefit analysis by match category under the partial coverage with concentrated density with m = 11 As a complement to

Table 4 and

Table 5, it is worth noting that for the prize tiers corresponding to

r = 2,

r = 1, and

r = 0 matches, the cumulative result yields a negative balance of -

$462.

Table 5.

Box 2

Cost-benefit analysis by match category under the partial coverage with concentrated density with m = 11 As a complement to

Table 4 and

Table 5, it is worth noting that for the prize tiers corresponding to

r = 2,

r = 1, and

r = 0 matches, the cumulative result yields a negative balance of -

$462.

3.2. An analysis of the Lucky Pick Historical Series

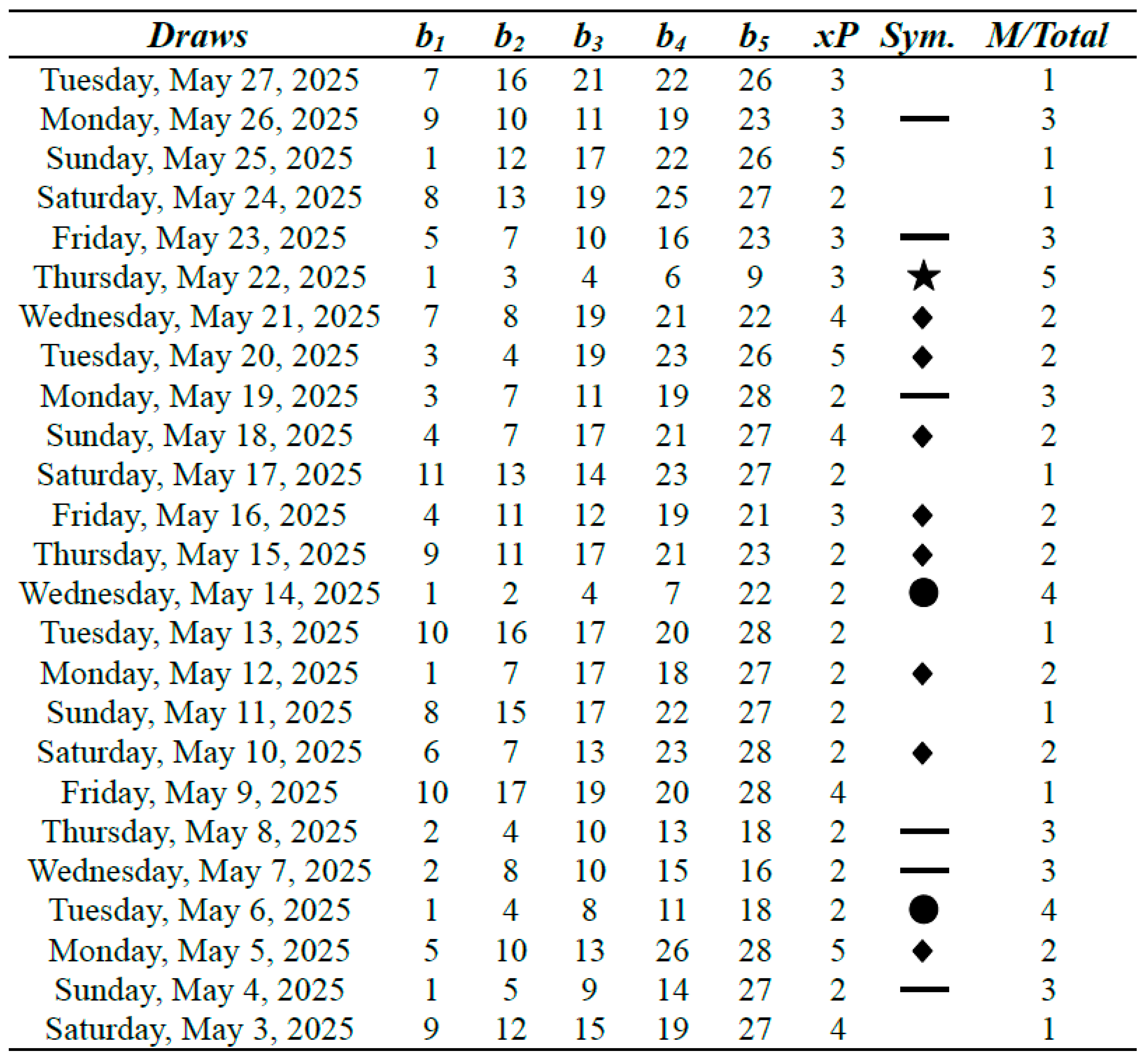

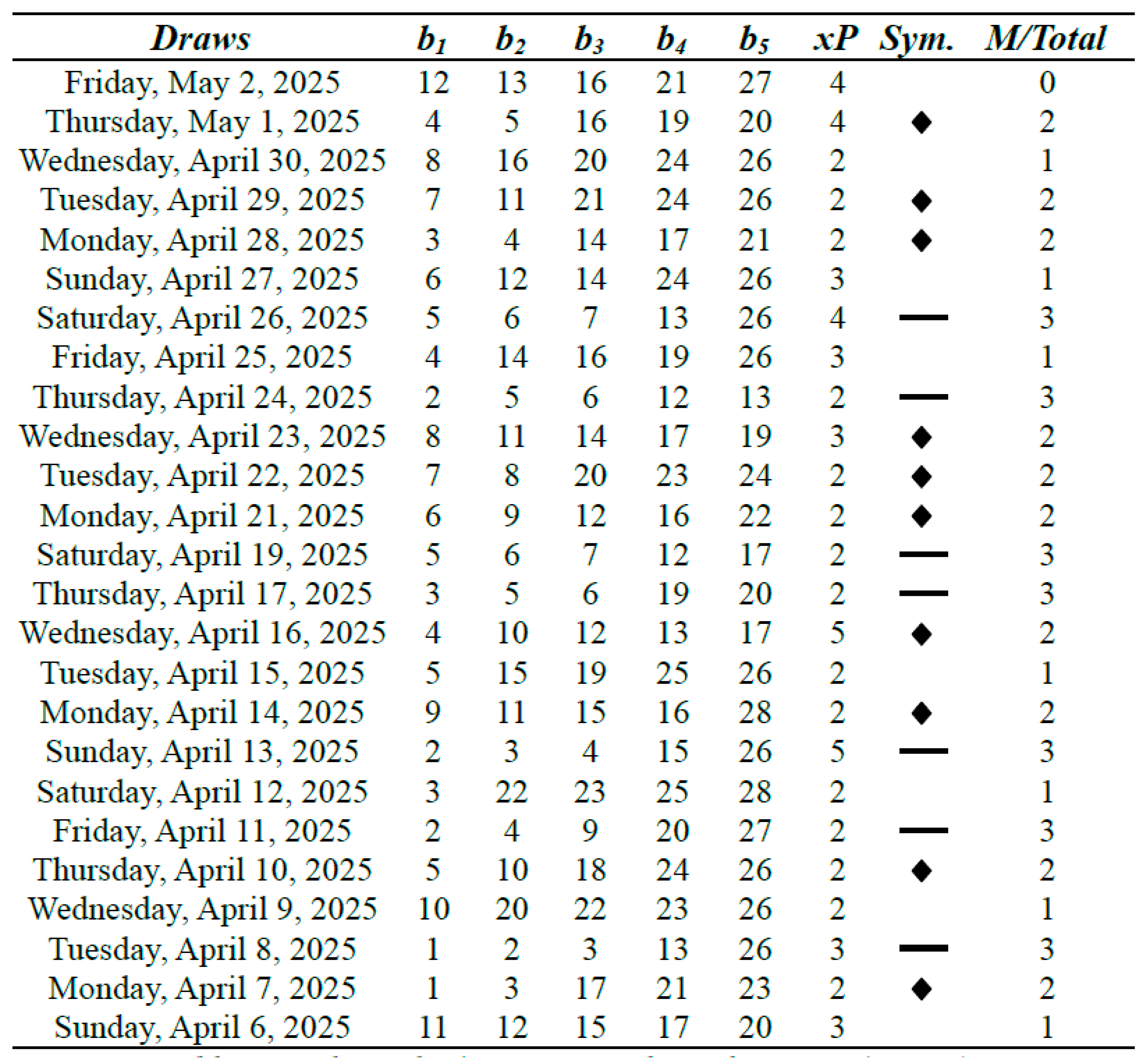

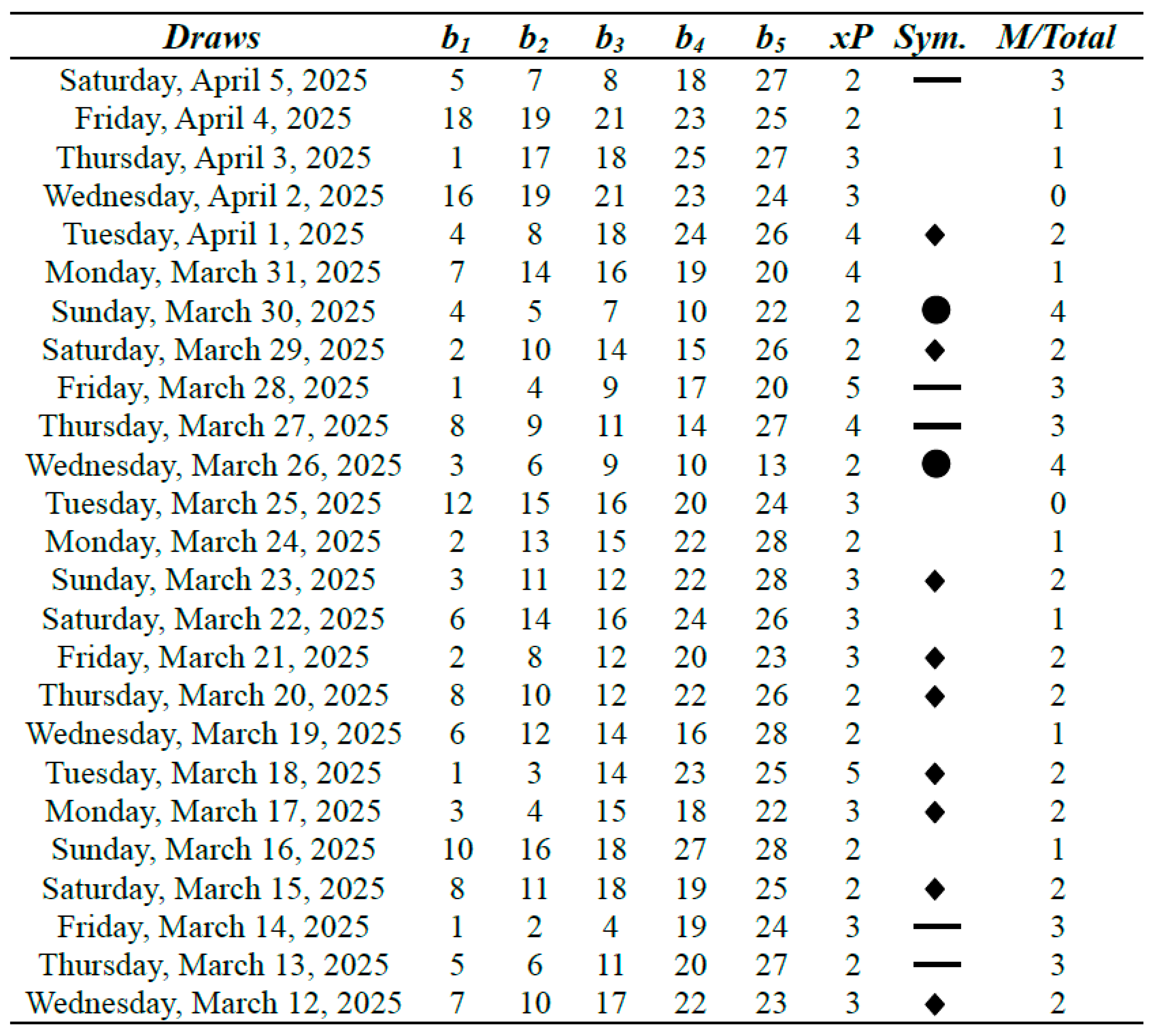

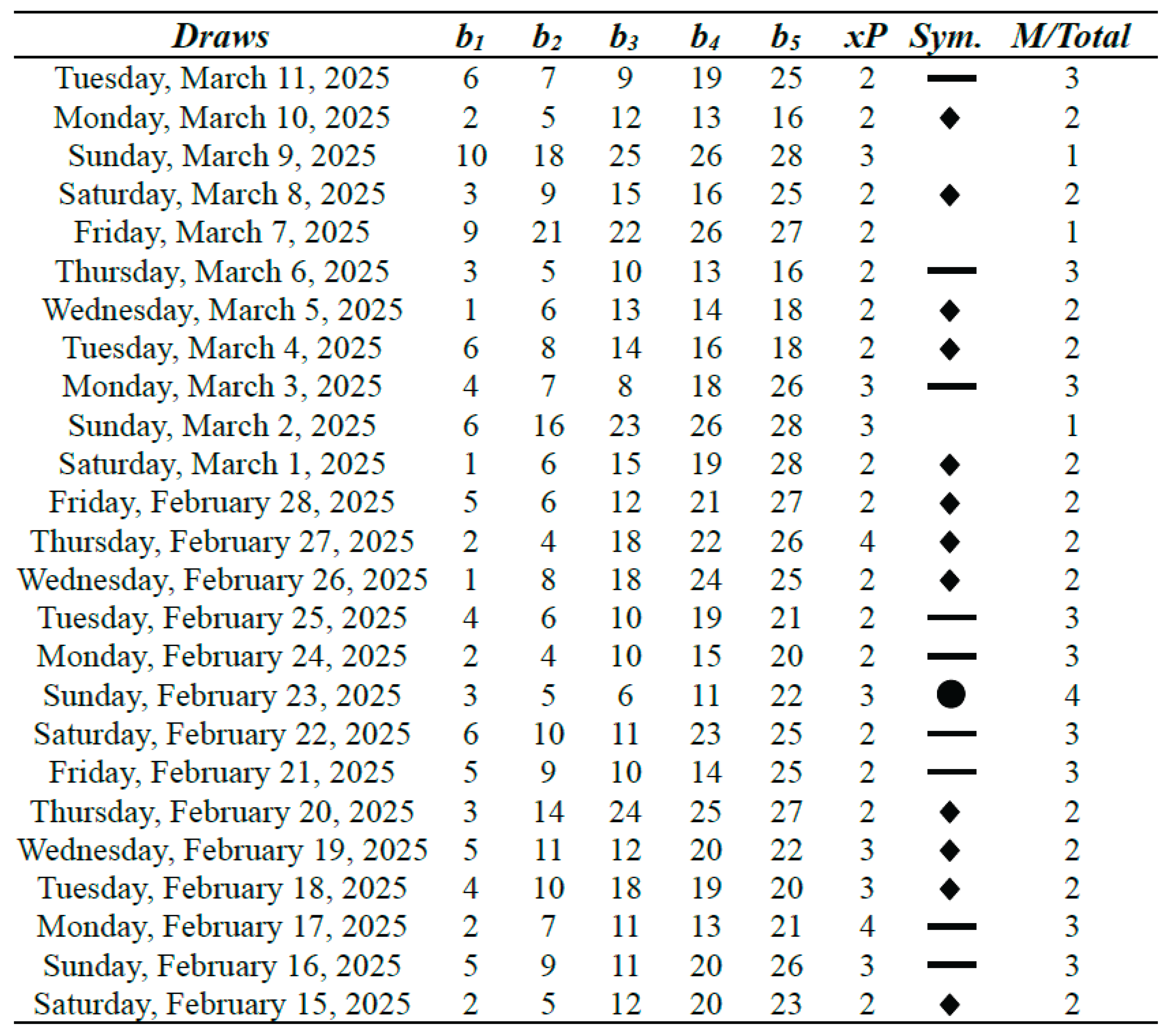

In the tables that follow, we present the historical series of 100 actual lottery draws, spanning from February 15, 2025, to May 27, 2025. In analogy with the Oklahoma Cash 5 example by Pereira (2025a), the use of symbols representing different match outcomes was also recommended and applied here, in order to enhance the visual interpretation of the results through the lens of convergence in probability.

Table 4.

Lucky Pick 5/28 Lotto results with m = 11 (Part I).

Table 4.

Lucky Pick 5/28 Lotto results with m = 11 (Part I).

Table 5.

Lucky Pick 5/28 Lotto results with m = 11 (Part II).

Table 5.

Lucky Pick 5/28 Lotto results with m = 11 (Part II).

Table 6.

Lucky Pick 5/28 Lotto results with m = 11 (Part III).

Table 6.

Lucky Pick 5/28 Lotto results with m = 11 (Part III).

Table 7.

Lucky Pick 5/28 Lotto results with m = 11 (Part IV).

Table 7.

Lucky Pick 5/28 Lotto results with m = 11 (Part IV).

Table 8.

Analysis of 100 Lucky Pick 5/28 Lotto draws considering partial coverage with concentrated density with m = 11 (Box 1).

Table 8.

Analysis of 100 Lucky Pick 5/28 Lotto draws considering partial coverage with concentrated density with m = 11 (Box 1).

| Matches |

100 Last Draws |

P/L |

| 5 |

1 |

$37,000 |

| |

5 |

$47,190 |

4

3

X≤2

|

27 |

$53,250 |

| |

67 |

-$30,954

$106,486 |

Table 9.

Analysis of 100 Lucky Pick 5/28 Lotto draws considering partial coverage with concentrated density with m = 11 (Box 2).

Table 9.

Analysis of 100 Lucky Pick 5/28 Lotto draws considering partial coverage with concentrated density with m = 11 (Box 2).

| Matches |

100 Last Draws |

P/L |

| 5 |

1 |

$37,000 |

| |

5 |

$14,190 |

4

3

X≤2

|

27 |

$10,326 |

| |

67 |

-$30,954 $30,562 |

As observed in Box 1, a total positive return of $106,486 was achieved over the course of 100 Lucky Pick draws, yielding an average profit of $1,064.86 per draw while playing only 462 tickets. Even if the jackpot event were excluded from the calculation, the net result would still remain attractively positive for a game typically classified as one of negative expectation and pure chance.

Should a syndicate or individual player opt to reduce the number of tickets further - for instance, to 46 - it would be theoretically reasonable to anticipate a proportional return of approximately $10,648.60, in line with the linearity of expectation observed in this historical series. However, any such strategy must consider a more conservative assessment, excluding the jackpot from expected values, and account for the increased volatility in standard deviation prior to convergence. Nonetheless, as the number of participations grows and n → ∞, a mathematically secured trend of positive expectation becomes increasingly evident.

Regarding , despite the significantly lower payoffs from secondary prizes compared to those in Box 1, the overall financial outcome was, as expected, impacted. Nevertheless, a net profit of $30,562 was observed over 100 consecutive draws, demonstrating a positive trend and a viable longterm strategy for m = 11, which corresponds to 462 tickets. However, it's crucial to note that in a more conservative application for Box 2, one that disregards the jackpot entirely, this strategy does not tend to be viable for even greater reductions in the number of tickets (e.g., 231 or 46 tickets). In such cases, the positive mathematical expectation is predominantly achieved through the jackpot, rather than solely through secondary prizes, which is typically the core premise of the Sirius Code's proposed method.

Through this study, we can discern that the observed outcomes do not stem from overfitting or a subjective selection of a specific historical data series. It is clear and understandable that despite the natural volatility inherent in profits and losses, there is a strong tendency toward a positive mathematical expectation. This trend is directly attributable to the cost-benefit relationship derived from the partial coverage with concentrated density strategy, the systematic acquisition of tickets, and consequently, the results of the draws and the underlying combinatorial analysis. The academic community is cordially invited to scrutinize this study, as well as to apply the same proposed model to other data intervals and communicate their findings, highlighting both the strengths and any points requiring further attention.

Mathematically, we can confidently state that we have found a winning strategy. However, it is crucial to acknowledge certain limitations of the model. Firstly, access to the intricate details of this model may not be universally available to all players. Secondly, while the cost of ticket acquisition is substantially reduced, it might still present a limiting factor for numerous players. This inherent imbalance ultimately generates an asymmetric advantage for specific groups, which, indeed, lies at the heart of the Victoria-Nash Asymmetric Equilibrium (VNAE).

This aspect of the VNAE, when considered within social contexts, presents considerable ethical delicacy. However, despite the natural and/or created asymmetries within a stochastic environment, the new equilibrium proposed by Pereira (2025d), as the author points out, must not be utilized to justify social inequalities as inherent by nature. On the contrary, the proposed model, precisely by comprehending these disparities and irregularities in the natural world, has emerged as a means of mathematically representing these phenomena. This representation serves not merely as a practical demonstration but rather as a call to action for establishing a world in which the game of life is at least ‘less unjust’ for all, thereby offering improved basic conditions for players currently at a disadvantage to pursue their respective sets of strategies.

Denying these asymmetries means denying our own reality. Therefore, as Pereira discusses in Section 3.6.1 (2025d), new metrics in economic sciences could be developed to analyze these asymmetries and their impacts across various sectors of society. This includes areas such as income distribution, levels of education and opportunity, the quality of life, and economic development of a nation.