2.1. Sirius Code and the Victoria-Nash Asymmetric Equilibrium (VNAE)

The Sirius Code is a statistical methodology grounded in the principles of Game Theory and Decision Theory, encompassing elements of non-cooperative games, zero-sum games, imperfect information, stochastic, and repeated games, as discussed by Aumann (1981), among others. However, it is most directly linked to the Victoria-Nash Asymmetric Equilibrium (VNAE), as introduced by Pereira (2025). At its core, the Sirius Code operationalizes the concept of partial coverage with concentrated density, a strategy that restricts the combinatorial scope of lottery entries to a strategically chosen subset of the number space, within which full coverage is performed.

Furthermore, the term “concentrated density” refers to Feller’s paradox (1968) when analyzing local clustering and global uniformity within a stochastic system given a uniform distribution, for example, as we can see below:

“In this study of lotteries, through the uniform distribution of numbers we can see, as just one example, that although globally all the numbers converge in the long term with the same chances of coming out, in the short term, that is, in each draw, we can see that it is common for results to ‘disregard’ certain groups of numbers (e.g: in an X or Y column) and concentrating on certain groups of numbers, with the characteristic that they come out very close together rather than evenly distributed in each draw, for example resulting in 2, 9, 14, 23, 42, 56 instead of 6, 18, 32, 44, 48, 59 if we consider a lottery design of 6/59, for example” (Pereira, p. 25-26, 2025).

Pereira (2025) also argued that it is important not to confuse concentrated density with a higher probability of events occurring, since no probabilistic principle has been violated, only analyzed through their “architectures”:

“Through the lens of Feller’s Paradox (1991), it may be justifiable to use only certain sub-sets of numbers, focusing on secondary prizes as a way of making consistent profits over the long term (depending, of course, on the payoffs offered by the “Houses”). However, we should not confuse the fact that by employing these statistical regularities we are increasing the probability of the events in the “grouped” sub-set since, in principle, each number has the same probability of coming out” (Pereira, p. 26, 2025).

The Victoria-Nash Asymmetric Equilibrium (VNAE), first introduced in the paper “Victoria: Beating the House Using the Principles of Statistics and Randomness”, builds upon Nash’s (1951) seminal framework of non-cooperative games. VNAE departs from the traditional view by treating the inherent randomness of stochastic games not merely as background noise or an incidental feature of the environment, but as a strategic resource. In this formulation, randomness becomes a source of asymmetric advantage for the player capable of systematically harnessing and “taming” it. In the field of time series analysis, Pereira (2022) demonstrated that part of the noise, random fluctuations in this context, represented by the standard deviation can be applied strategically to improve forecasts by obtaining lower absolute and relative errors.

Historically, scholars have continuously sought methods to simulate randomness as a means of modeling phenomena and supporting decision-making processes. A significant milestone was the emergence of the field of pseudo-random number generation (PRNG), notably marked by the pioneering work of von Neumann (1946), who introduced one of the first algorithmic approaches to synthetic randomness. This was soon followed by a notable contribution from Lehmer (1951), whose development of the Linear Congruential Generator (LCG) laid the groundwork for a lineage of algorithms that would evolve over subsequent decades. More recently, this trajectory has been expanded by conceptual explorations such as the Itamaracá PRNG proposed by Pereira (2022), which introduced a novel “mirroring” mechanism based on the absolute value function as an alternative structural approach to randomness generation. In parallel to the deliberate simulation of randomness, there has also been a longstanding intellectual effort to understand the very nature of randomness itself.

The endeavor to tame randomness has long been a subject of intense discussion within the academic community, with notable prominence in the fields of ergodic theory in pure mathematics and dynamical systems in physics. Itô’s seminal contributions (1941) and (1951) particularly the Itô integral and Itô’s Lemma, established rigorous frameworks for modeling systems influenced by random noise. His work enabled the precise analysis of stochastic differential equations (SDEs), transforming fields such as financial mathematics (e.g., option pricing) and statistical mechanics. By formalizing the interplay between deterministic trends and random fluctuations, Itô’s theory provided tools to decompose, predict, and optimize complex dynamical systems subject to uncertainty.

Potential applications of the Victoria-Nash Asymmetric Equilibrium (VNAE) extend well beyond the domains of entertainment and games of chance, such as sports betting (as explored in the original study) and lottery systems. VNAE may also serve as a valuable framework for modeling complex social dynamics, offering insights into social inequalities, romantic relationships, and cultural behaviors. Its applicability further encompasses corporate environments (e.g., interactions between firms and stakeholders), geopolitical strategies, cybersecurity protocols, artificial intelligence systems, and dynamic systems in physics. In addition, it is promising in other areas within the economic sciences such as behavioral economics, studying how rational players will make decisions given a scenario in which true randomness can be partially predicted and shaped in our favor. In the biological sciences, especially in process optimization and the deliberate identification of disease treatments, among other prospective fields.

We posit that players who possess asymmetric information or conditions regarding a given phenomenon intrinsic to the game as well as advanced knowledge in randomness may, through mathematical, statistical, physical operations, or other cognitive strategies, render part of true randomness partially predictable or even tamed. In this context, randomness ceases to be merely a component of an “optimal strategy” within systems traditionally deemed “unpredictable,” “immutable,” or “untameable.” Rather, it emerges as a proposed function within the portfolio of Game Theory, capable of influencing outcomes in a non-cooperative game.

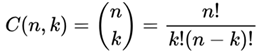

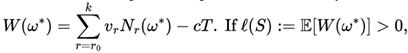

The mathematical formulation according to the Sirius founding paper is summarized below.

Let S⊂Ω ={1,...,

N}, with ∣

S∣=

M, and

k ≤

M. Suppose that in each draw the player bets on all

possible combinations within

S. Let

W(

ω) be the net profit corresponding to a draw ω∈

considering prizes

vj and cost

c. Then:

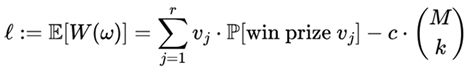

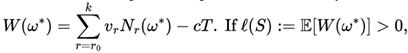

where,

ℓ: is the expected net profit per draw;

vj: is the monetary value of the jth

prize tier;

prize P[win prize vj]: is

the probability of winning prize vj;

c: is the cost per ticket;

is the number of tickets being purchased from the subset

S⊂

Ω of size

M.

Lottery Framework. Let Ω ={1, ...,

N}

be the number space. A player selects

k numbers per ticket. Each draw

uniformly selects

ω*∈

Prizes

vr are awarded for matching

r∈{

r0, ...,

k} numbers.

Definition 1

(Partial Coverage

with Concentrated Density). A strategy choosing a subset

S⊂Ω (∣

S∣=

m <

N) and betting on all T =

combinations within

S.

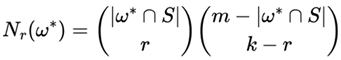

Definition 2

(Winning Tickets Distribution). For a draw

ω*, the number of winning tickets with exactly

r matches is:

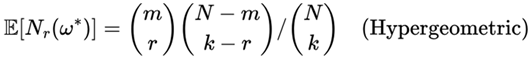

with expectation:

Theorem

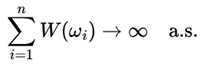

(VNAE-Aligned Long-Term Profitability

). Let

then:

Proof:

I. VNAE connection: The predictable random component fv(Xt) optimizes S*= argmaxS ℓ(S) by exploiting local deviations from uniformity as we can see in Feller’s paradox, and also due to probability convergences that we can verify in different ways from Kolmogorov’s axioms to Chebyshev’s inequalities.

II. SLLN: Apply Strong Law of Large Numbers to i.i.d. W(ωi).

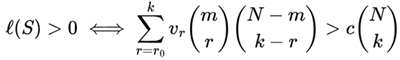

Corollary

(General Profitability Threshold

).

This condition naturally leads to two key implications: first, the Victoria-Nash Asymmetric Equilibrium (VNAE) optimization reduces to finding the optimal subset size m* that maximizes ℓ(S) for given lottery parameters (N, k, vr, c); second, as demonstrated empirically by Pereira (2025) for Lotofácil in Section 4, this framework identifies m* = 19 as the most cost-efficient coverage for balancing ticket expenditure against secondary prize returns.

A comprehensive treatment of the mathematical formulation can be found in

Section 3.2 of Pereira (2025), the foundational publication on the Sirius Code. Furthermore, on specifically obtaining an asymmetric advantage through convergence in probabilities in the sense of “waiting for certain moments” to enter a sequence of draws in a lottery, we recommend reading section 3.5 of this same paper.

Instead of trying to predict the exact winning numbers, the method identifies and exploits local statistical asymmetries, the “architectures” in which Pereira (2025) formalizes through the predictable random component function fv(Xₜ). This function captures latent regularities within the randomness, allowing the bettor to optimize the allocation of tickets to certain randomly chosen regions and, therefore, a level of subjectivism (concentrated density), favoring cost optimization in the acquisition of all possible combinations of tickets in the subset as well as winning secondary prizes. This behavior of “clustering” in certain locations at random, even though in a uniform distribution, was also addressed by Feller (1968).

Crucially, the Sirius Code shifts focus from jackpot-centric strategies to profitability through secondary prize tiers, a move that renders the method both cost-efficient and scalable. The strategy (as presented in the VNAE) is further underpinned by some classical probabilistic guarantees, such as the Kolmogorov’s axioms (1933); Law of Large Numbers, Markov’s processes (1906); Stirling Numbers (1730); Central Limit Theorem by Moivre (1730), Laplace (1812) Lindeberg (1922), and Lévy (1939); Chebyshev’s inequalities (1867), and with Renewal Theory by Cox (1962) ensuring long-term convergence toward a positive expected value under rational and repeatable application.

As an analogy, the conceptual basis of the Sirius Code and the Victoria-Nash Asymmetric Equilibrium (VNAE) resonates with key ideas from ergodic theory. As outlined by Viana and Oliveira (2016) in Foundations of Ergodic Theory, ergodicity characterizes the long-term statistical behavior of dynamical systems through the equivalence between time and space averages. The Sirius Code and VNAE, however, exploit the observation that real-world stochastic systems, such as lotteries or social games, may exhibit weak or partial non-ergodicity, particularly in short-term analyses (e.g., local clustering phenomena). This allows for the identification of structural asymmetries, which can be strategically leveraged over time to achieve sustainable advantages.

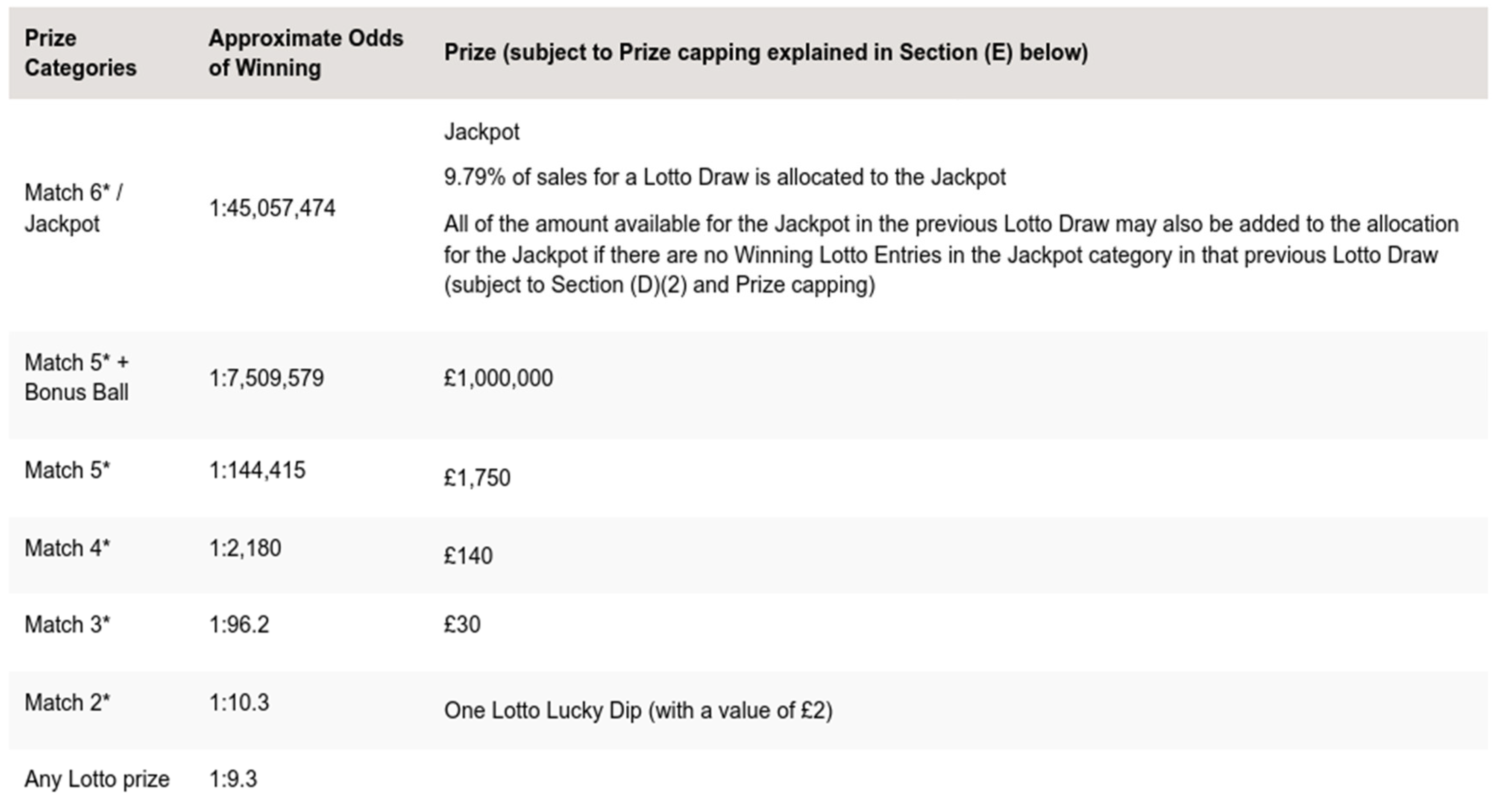

Originally validated on Brazil’s Lotofácil (15/25), where it achieved a net profit of over $190,000 across 100 draws using optimized subsets, the Sirius Code is designed to be generalizable to a wide variety of lottery formats, including 6/59 structures such as the UK Lotto. Its application herein to the UK Lotto seeks to evaluate whether the same strategic asymmetry and cost-benefit dynamics observed in prior implementations hold under a distinct lottery architecture.

possible combinations within S. Let W(ω) be the net profit corresponding to a draw ω∈

possible combinations within S. Let W(ω) be the net profit corresponding to a draw ω∈  considering prizes vj and cost c. Then:

considering prizes vj and cost c. Then:

is the number of tickets being purchased from the subset S⊂Ω of size M.

is the number of tickets being purchased from the subset S⊂Ω of size M. Prizes

vr are awarded for matching r∈{r0, ..., k} numbers.

Prizes

vr are awarded for matching r∈{r0, ..., k} numbers. combinations within S.

combinations within S.

then:

then: