3.1. Victoria

Just as the Tupi Guarani language, Fort Orange from the Island of Itamaracá, a municipality in the state of Pernambuco, Brazil, inspired the name of the Itamaracá PRNG algorithm, Victoria also had its moments.

The Victoria methodology is named after the city of Victoria in British Columbia, Canada. This city is known for its appreciation of the natural world, as well as its artistic and technological atmosphere. It is named after Queen Victoria of the United Kingdom, who left a strong legacy and commitment to the development of science, marking, for example, a golden age for Statistics through various discoveries that today shape the world around us.

Furthermore, when we're in a game, it is natural to want the ultimate goal, which is victory. So it is a reflection that the player, mathematically and statistically, will always have the advantage over the house in the medium and long run, regardless of any positive or negative results that occur along the way.

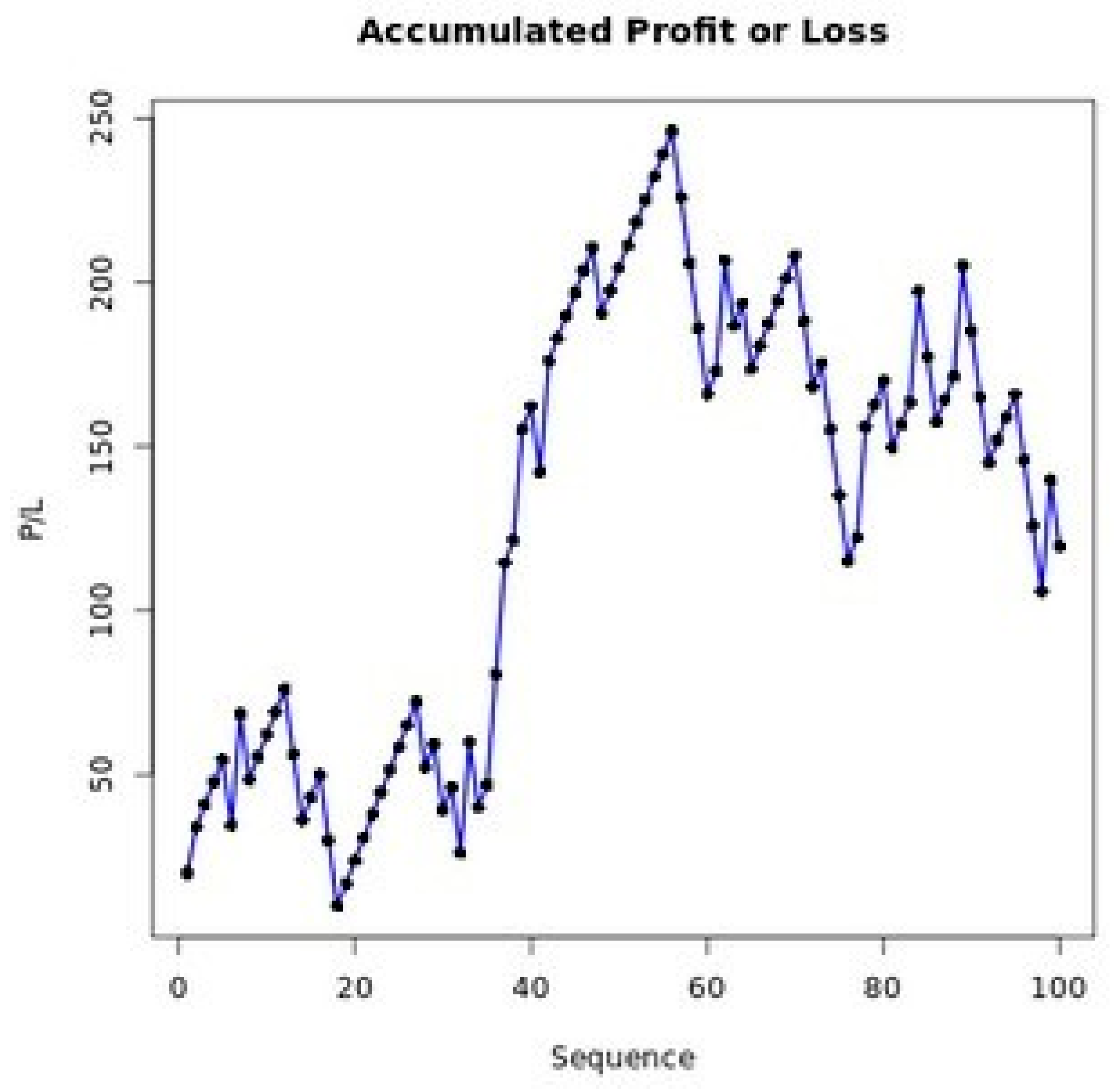

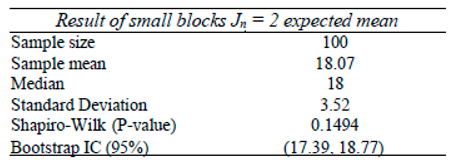

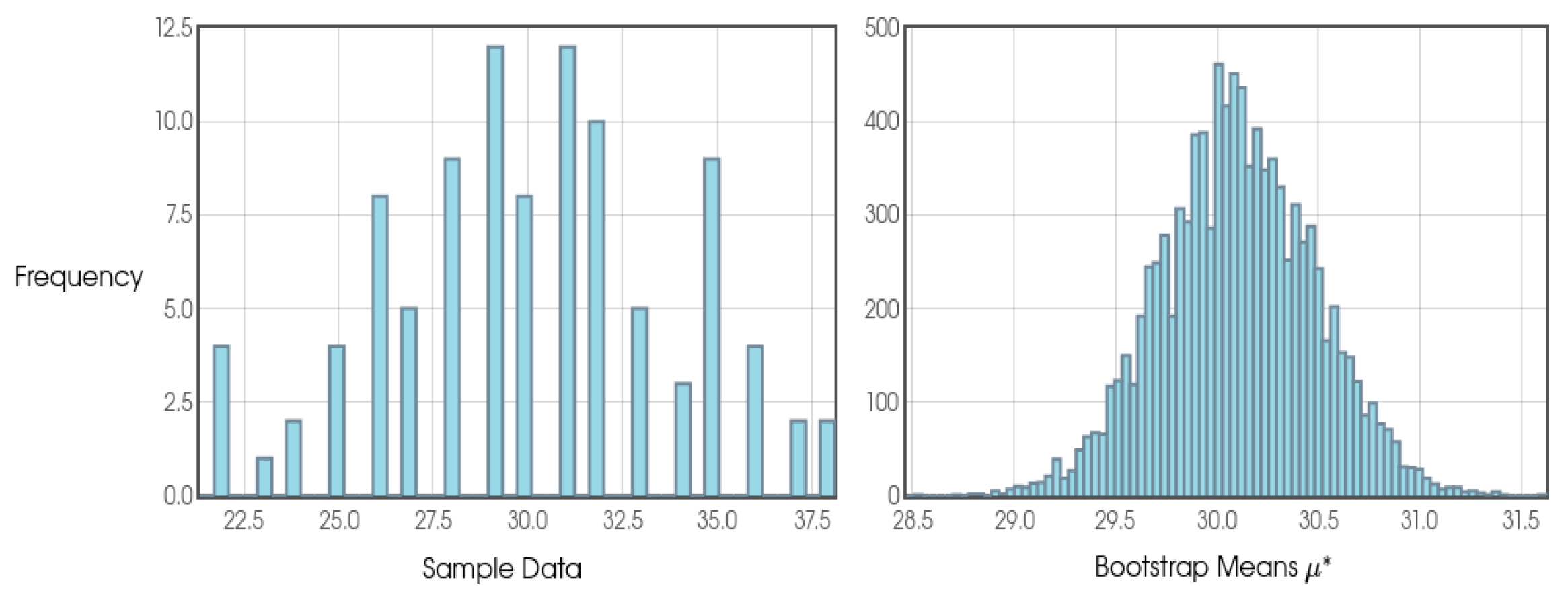

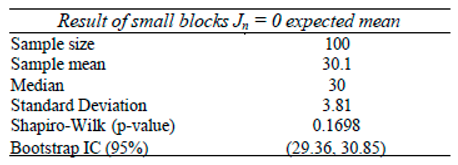

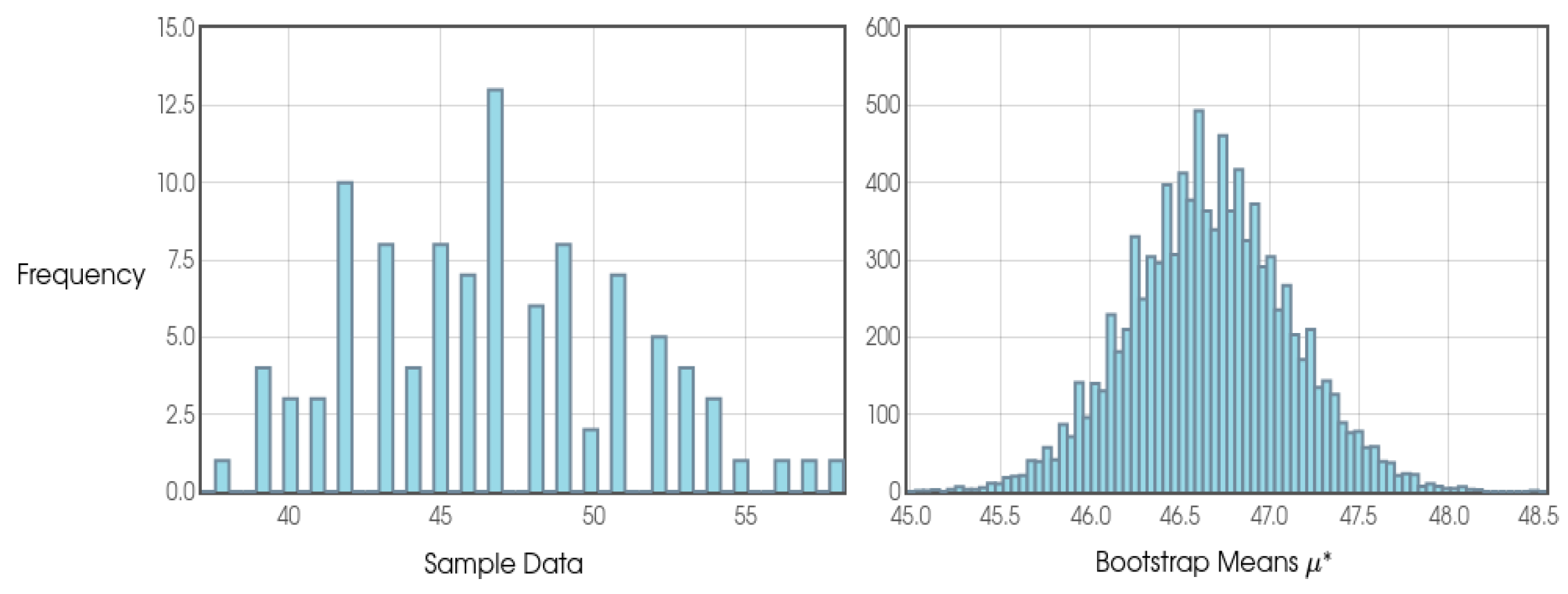

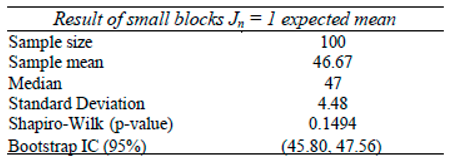

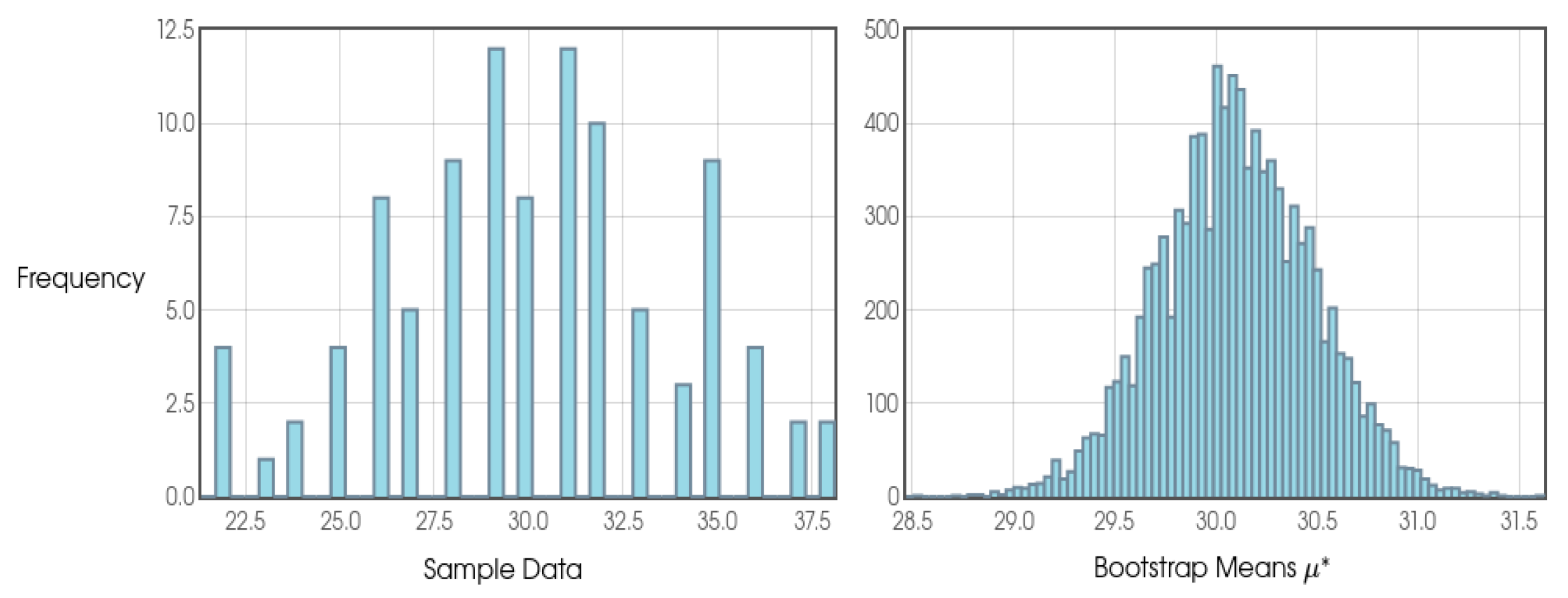

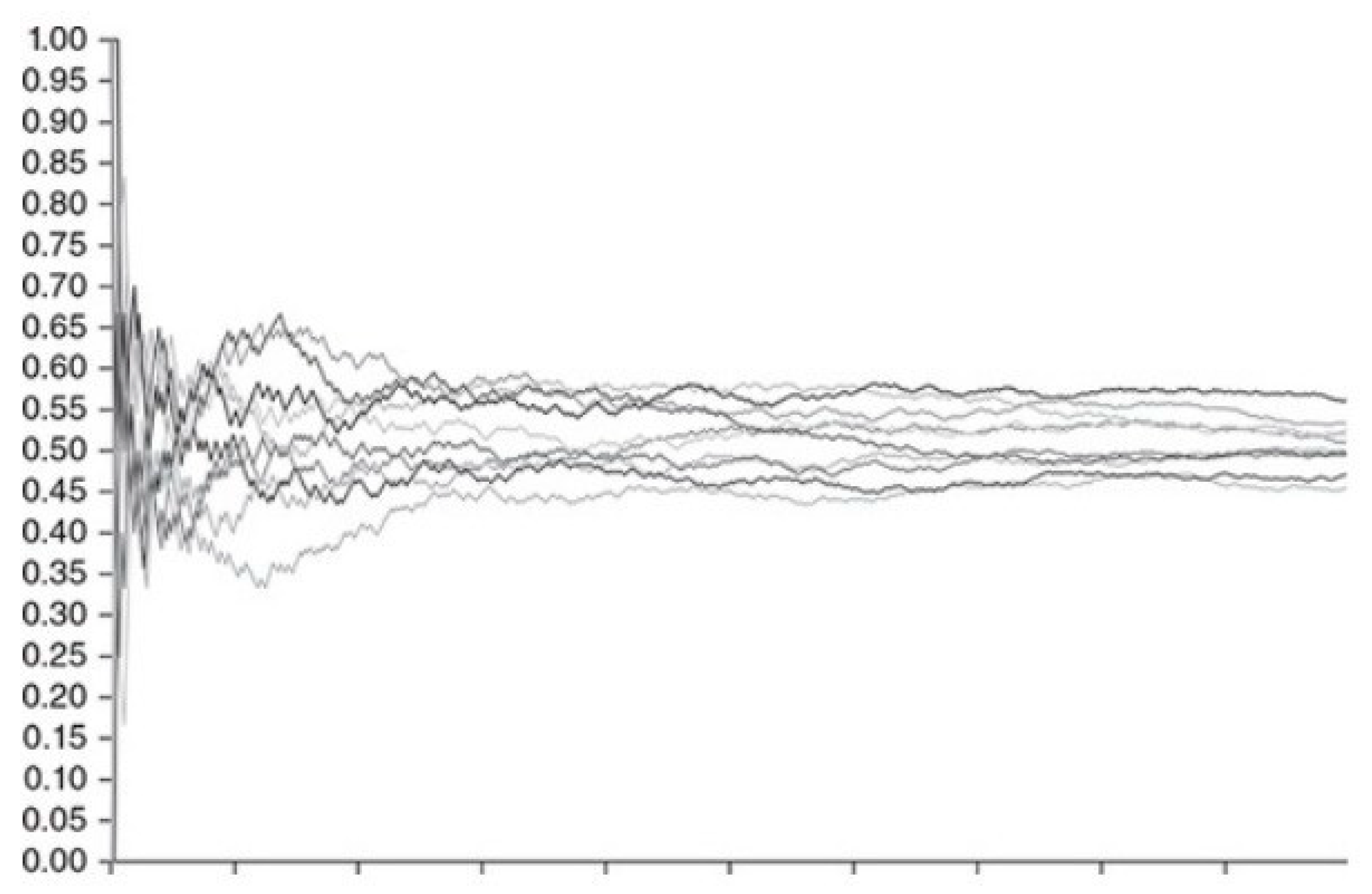

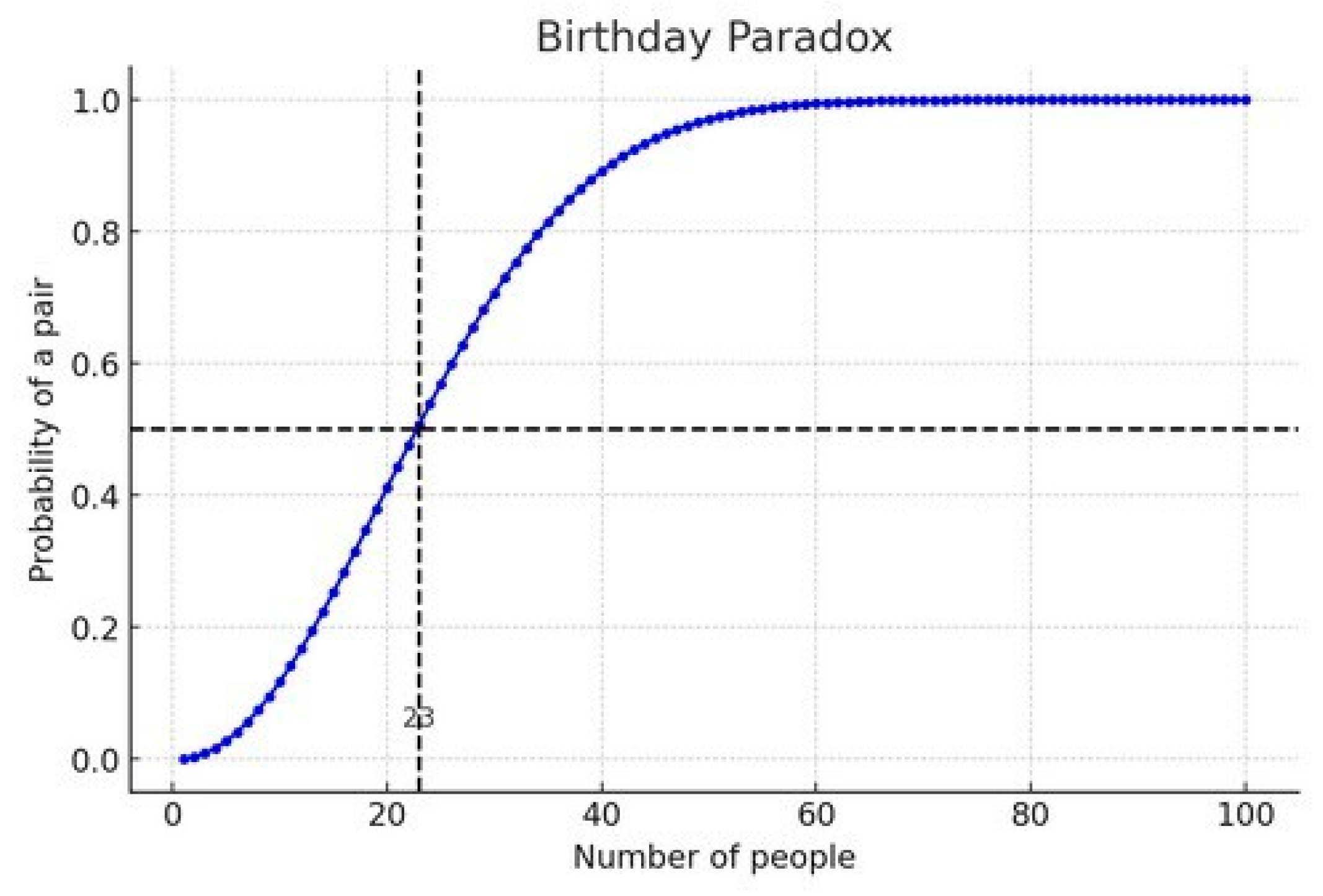

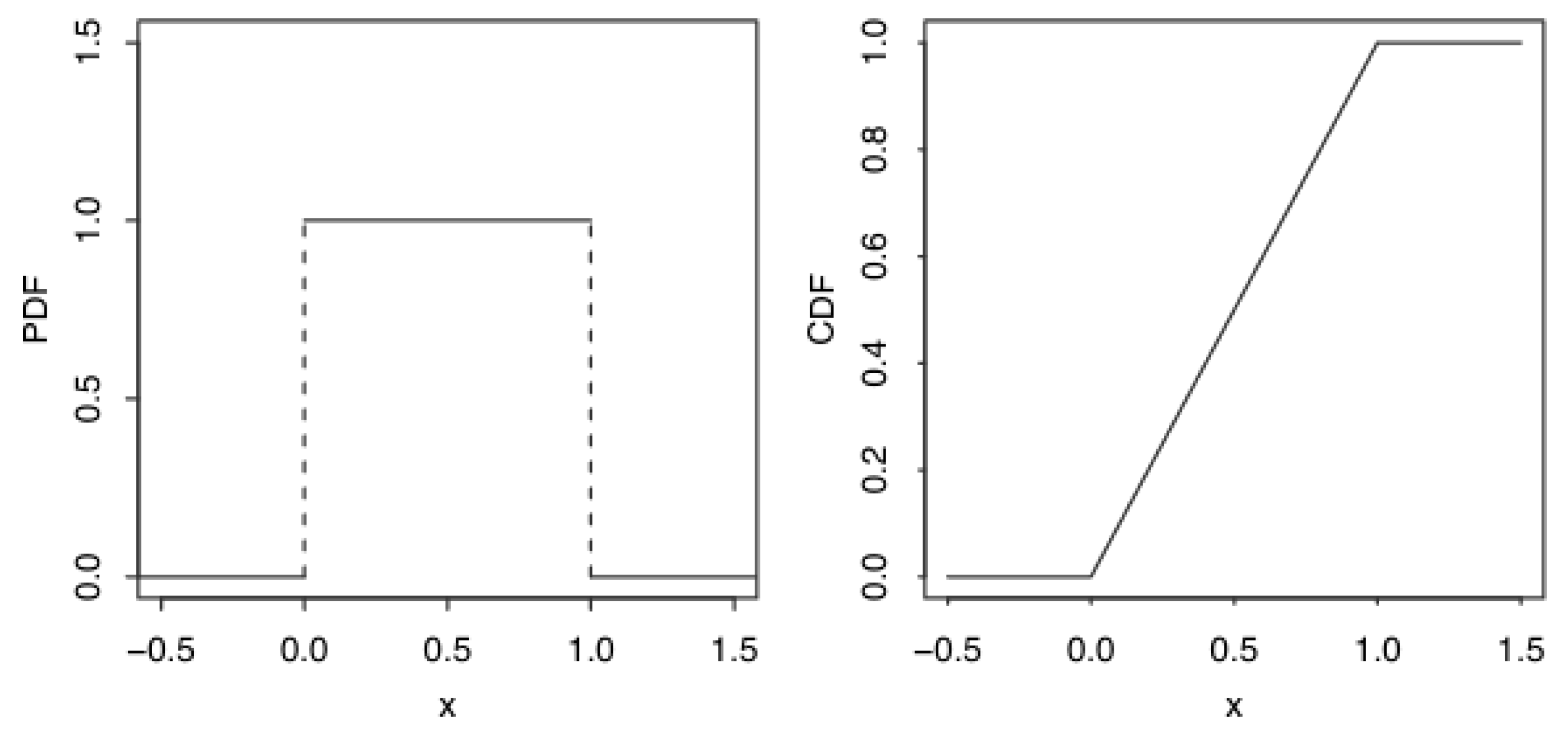

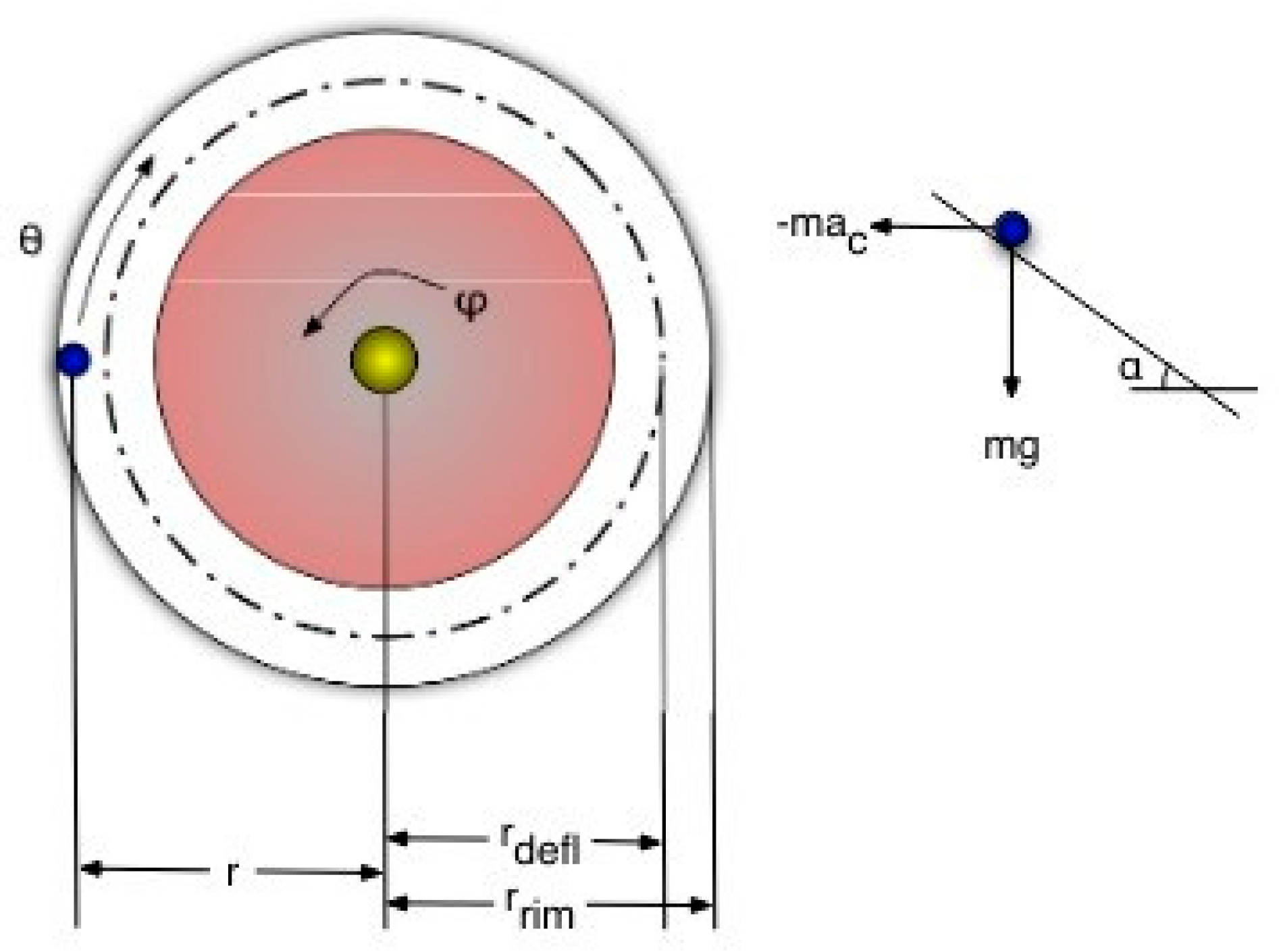

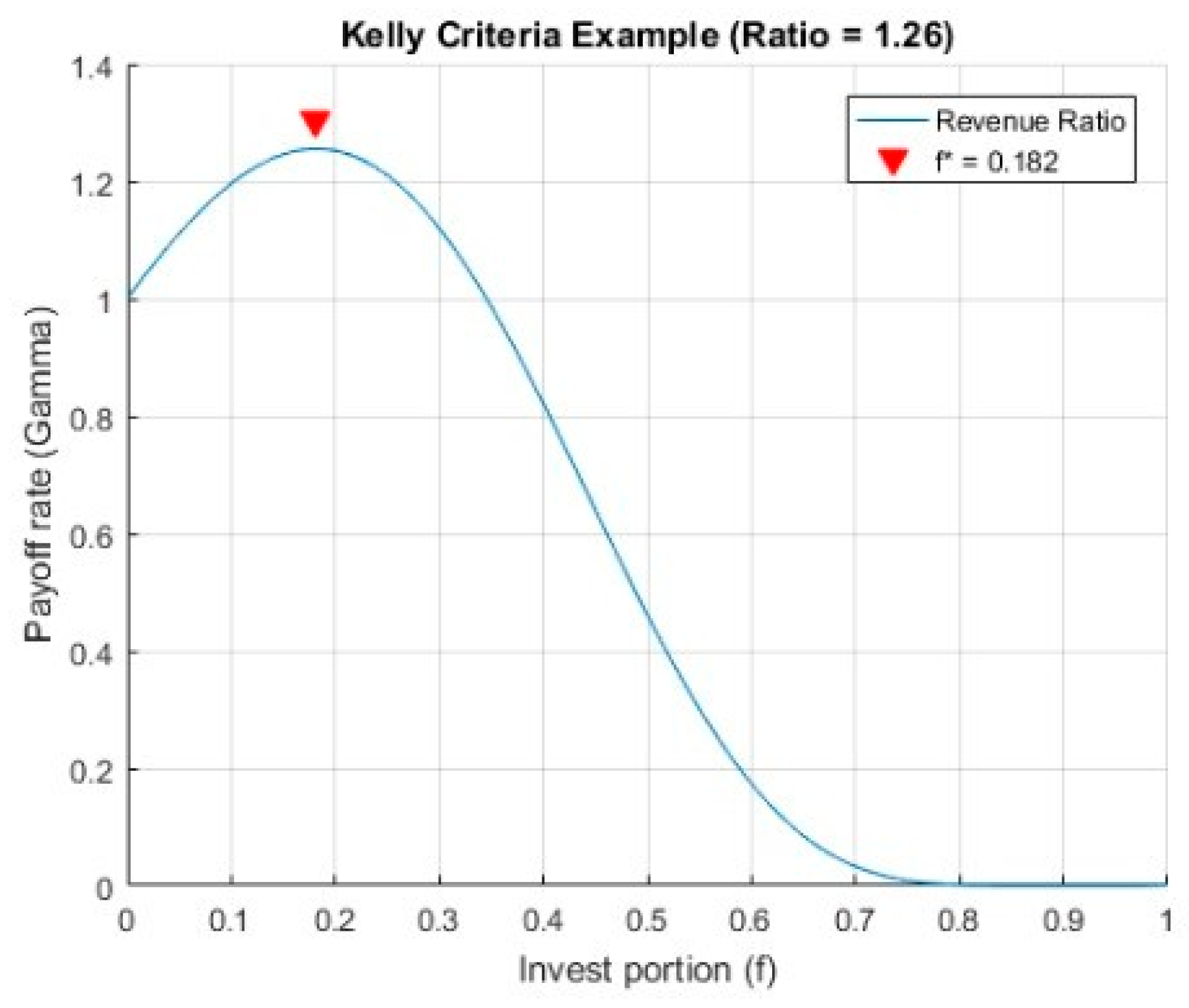

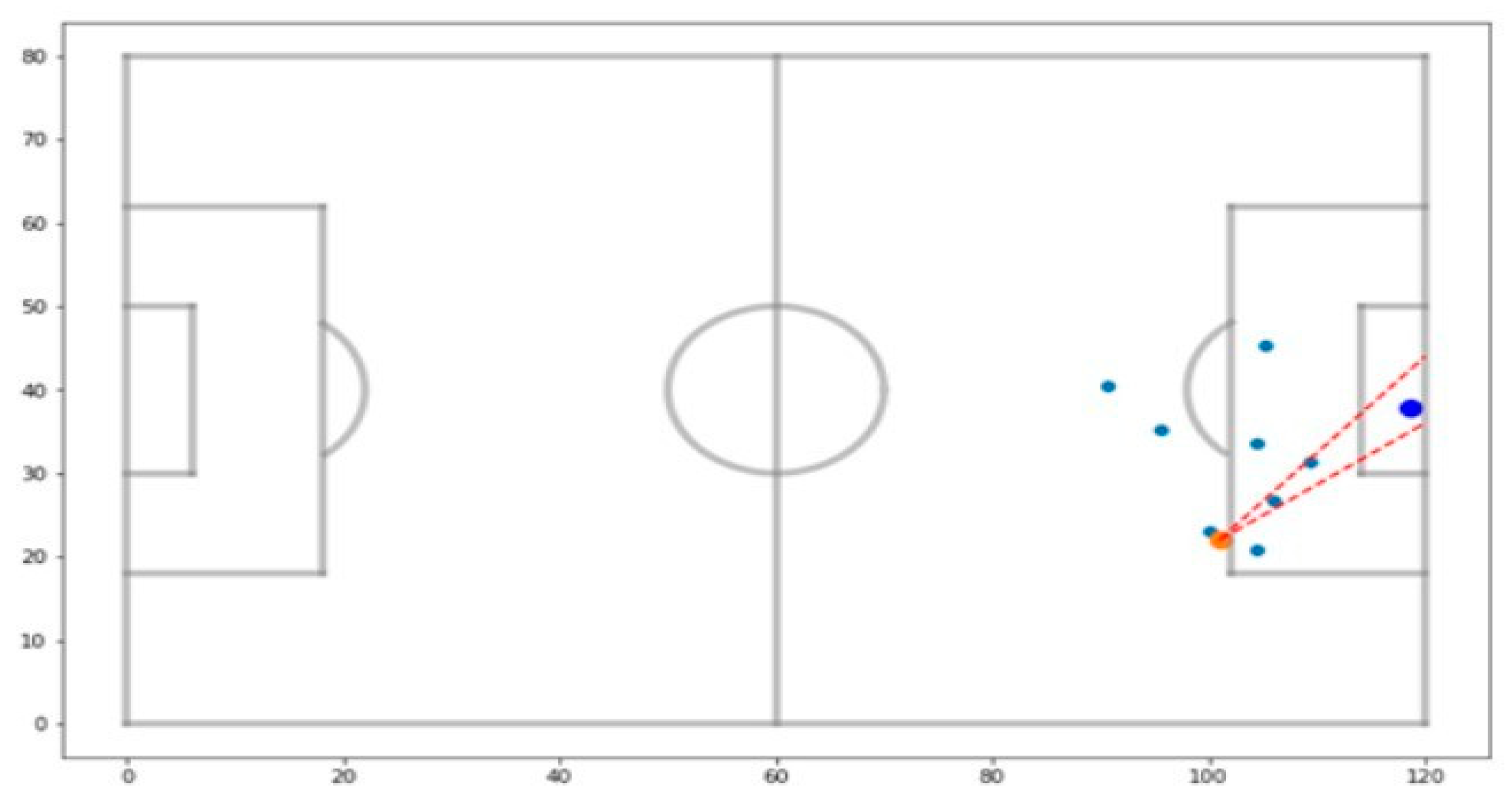

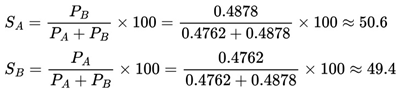

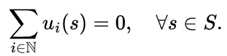

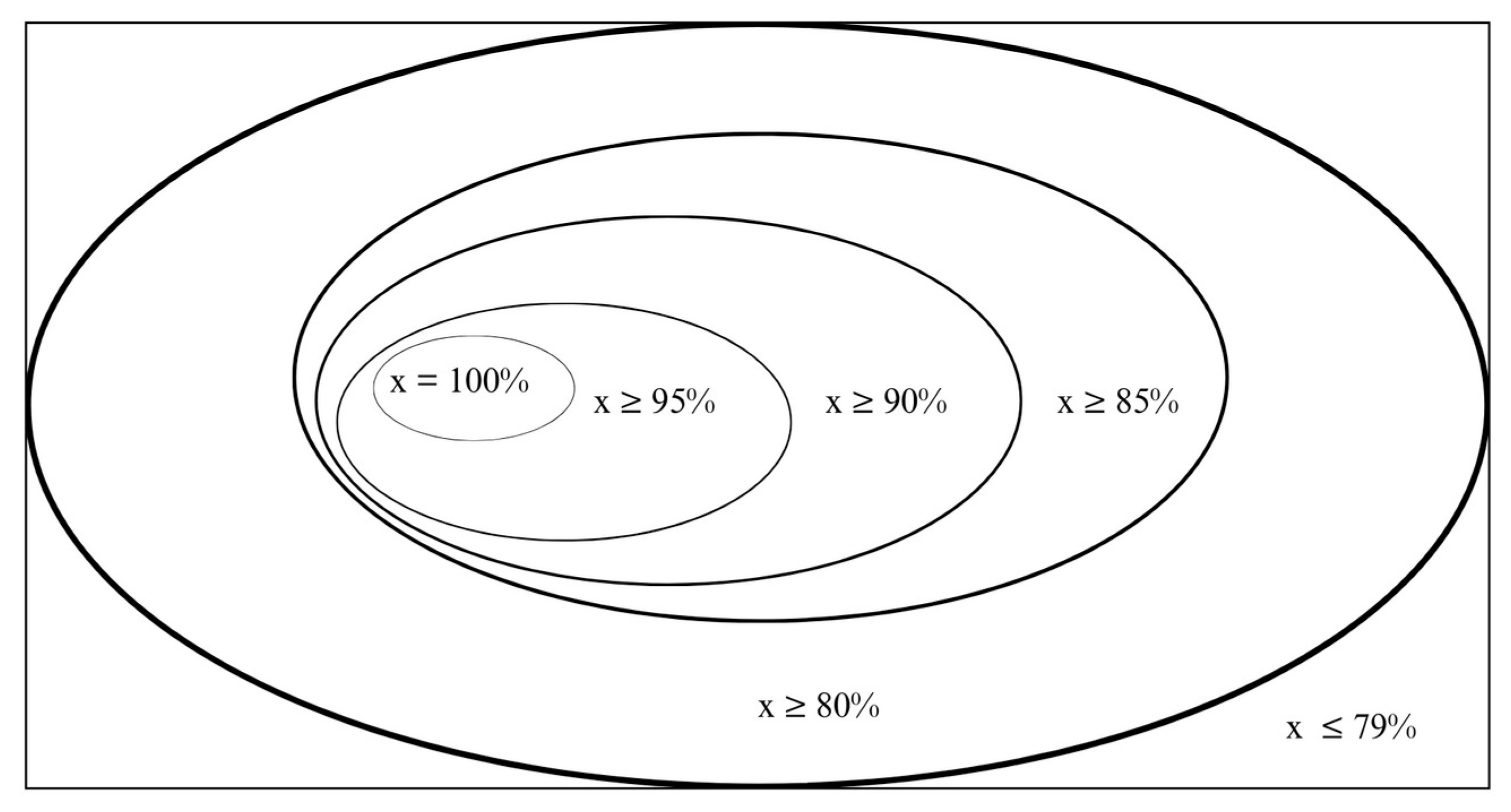

As we can see from

Figure 20, we can find different configurations and different results. We can say a configuration belongs to 94%, for example, if over the course of 100 FVs (Future Values) it has a maximum of 6 FVs with a result that is usually modestly negative over the long term. Therefore, the other 94 FV s contain positive results, indicating profitability in all of them.

Figure 20.

Configurations of φ, j and k separated by different categories.

Figure 20.

Configurations of φ, j and k separated by different categories.

It is known that in each standard Future Value (FV) approximately 10,000 games are theoretically expected. However, in practice, the actual amount of games will probably vary between 4,800 and 7,000 games depending on the settings chosen for a bettor to fulfill a complete FV containing all of his expected 100 Intermediate Blocks (IBs) and Small Blocks (jn).

It is clear to see that the closer to 100% a given configuration is, the less games and, consequently, time the bettor will have to play in order to mathematically eliminate any risks inherent in random noise, meaning that the most desirable thing is to identify a configuration that, if not 100%, is always statistically close to 100%.

Considering that today we have made significant progress in robotization models through machine learning and data mining, configurations that statistically offer us at least 94% positive FVs still seem viable for possible practical projects of this theorizing. In fact, other configurations such as those that converge to at least the 80% and 85% category, for example, could also present interesting costs/benefits, provided that the bettor is willing to take on more risk. All of these definitions will be discussed in more detail throughout this study.

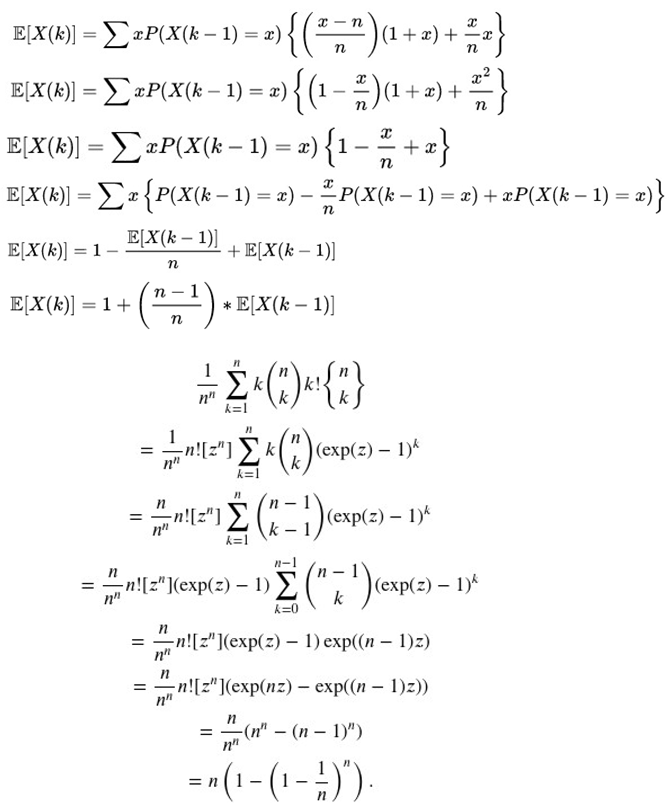

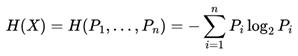

Victoria is based partly on the premise that advanced statistics and part of “tamed” randomness can offer sustained strategic advantage, even in games considered to be zero-sum. Fisher (1955) discusses the role of statistics in rational decision-making and how the correct use of inference can increase the probability of success in random systems.

In addition, the Victoria inspired by Stirling numbers in duplicate data analysis, anchored in the foundations of convergence in probability, also has interesting interconnections with the basic premises of Renewal Theory, specifically through the paper of Cox (1962). This theory is an extension of stochastic processes that studies times between successive events in random systems, especially in contexts such as:

queues and arrivals of customers in waiting processes

failure and maintenance of engineering systems

evolution of patterns over time in Markov chains.

The central idea of renewal theory is that there are statistical patterns in the times between events, allowing partial predictability in systems that, at first glance, may seem purely random, suggesting to us that structurable patterns can emerge from these chaotic processes.

Hubbell (2001) presented “The Unified Neutral Theory of Biodiversity and Biogeography” in which the author sought to explain patterns of biodiversity and biogeography based on principles of neutrality between species, where all species are considered ecologically equivalent (random) in their chances of birth, death, dispersal and speciation, for example.

Despite their randomness, it is noticeable that on a large scale, patterns can emerge due to cumulative interactions. In this sense, while analyzing complex biological and ecological systems, it also leads us down similar paths proposed by Cox (1962) as well as in the theorizing behind Victoria and the Victoria-Nash Asymmetric Equilibrium (VNAE).

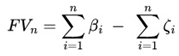

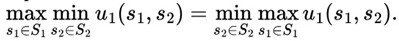

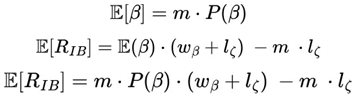

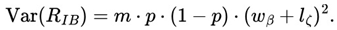

Below is Victoria's general formulation:

where,

φ = odd / probability of success of the event k = Time Period

S0 = Initial Value (fixed value used for each independent event)

β = "Success" blocks. That is, the cost/benefit ratio compared to the investment in each stake in each n game is positive and there is some profit.

ζ = "Failure" blocks. That is, the cost/benefit ratio compared to the investment in each stake iin each n game is negative and there is some loss.

We can say that the Victoria algorithm is based on the perspective of “blocks” and/or “hierarchy” for the sake of clarity. Below are some fundamental definitions:

p : probability, odd

S0 : initial value, stake

m : Number of Small Blocks (jn) in an Intermediate Block (IB)

k : number of k independent events

IB : Intermediate Block

βi : number of successful Small Blocks in an IB. ζi : number of Small Blocks of failure (ζi = m - βi) wβ : gain associated with a successful Small Block

lζ : loss associated with a small block of failure (ζ).

Within an Intermediate Block (IB) the final result of gain or loss will depend on the number of successful (β) or unsuccessful (ζ) blocks.

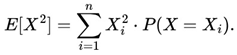

Total gain from successful Small Blocks (

β) can be represented by:

Total loss from Small Blocks of failure (

ζ) can be represented by:

Next, we'll look at the net result of any given Intermediate Block (

IB):

Since in this scenario we are dealing with a binary option, i.e. at the end of an

n sequence with

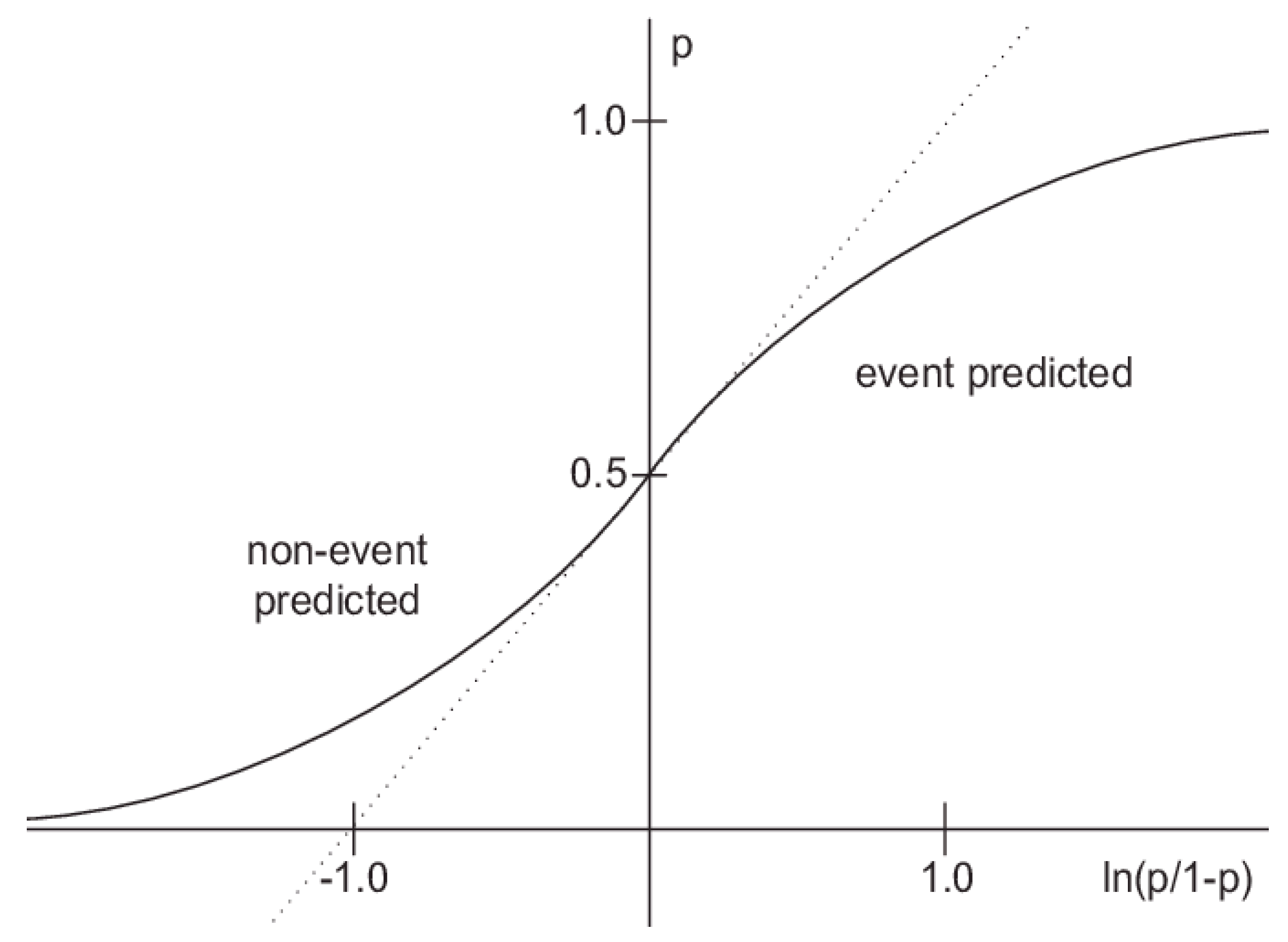

k random events whose outcome will define whether a block will be considered a success (returning some profit) or a failure (returning a negative value), we can consider that they follow a binomial distribution:

We can define the expected value of the result in an IB:

The general formula for the variance of the result of an Intermediate Block (IB) is:

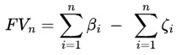

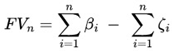

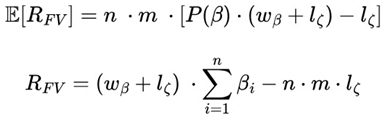

Below, we'll see that the Future Value (FV) consists of the sum of all the results of the Small Blocks of Success (β) or Failure (ζ) present within each Intermediate Block (IB):

Next, we can see the expected value and the general formula that shows the difference between the total sum of gains and losses over a Future Value (FV):

3.1.1. Design of an Intermediate Block (IB)

Table 7 shows the standard design of an Intermediate Block (IB):

Table 7.

Design of an Intermediate Block (IB).

Table 7.

Design of an Intermediate Block (IB).

| j1 |

j2 |

j3 ... jn |

| k1 |

k1 |

k1 k1 |

| k2 |

k2 |

k2 k2 |

| k3 |

k3 |

k3 k3 |

| ... |

... |

... ... ... |

| kn |

kn |

kn kn |

The product of jn and kn must be equal to or something close to 100. Knowing this information, we can say there will be several n possible combinations of jk. However, it should be clear after this first choice of j, and k there will also be the parameter φ considered “optimal”. This is what we'll see in the next topic.

Assuming that, with φ = 1.60 as a reference, we choose the following parameters j =16 and k = 6, we will have the following Intermediate Block (IB):

Table 8.

Example configuration with j = 16 and k =6.

Table 8.

Example configuration with j = 16 and k =6.

| j1 |

j2 |

j3 |

j4 |

j5 |

j6 |

j7 |

j8 |

j9 |

j10 |

j11 |

j12 |

j13 |

j14 |

j15 |

j16 |

| k1 |

k1 |

k1 |

k1 |

k1 |

k1 |

k1 |

k1 |

k1 |

k1 |

k1 |

k1 |

k1 |

k1 |

k1 |

k1 |

| k2 |

k2 |

k2 |

k2 |

k2 |

k2 |

k2 |

k2 |

k2 |

k2 |

k2 |

k2 |

k2 |

k2 |

k2 |

k2 |

| k3 |

k3 |

k3 |

k3 |

k3 |

k3 |

k3 |

k3 |

k3 |

k3 |

k3 |

k3 |

k3 |

k3 |

k3 |

k3 |

| k4 |

k4 |

k4 |

k4 |

k4 |

k4 |

k4 |

k4 |

k4 |

k4 |

k4 |

k4 |

k4 |

k4 |

k4 |

k4 |

| k5 |

k5 |

k5 |

k5 |

k5 |

k5 |

k5 |

k5 |

k5 |

k5 |

k5 |

k5 |

k5 |

k5 |

k5 |

k5 |

| k6 |

k6 |

k6 |

k6 |

k6 |

k6 |

k6 |

k6 |

k6 |

k6 |

k6 |

k6 |

k6 |

k6 |

k6 |

k6 |

As you can see from then on there will be 100 Intermediate Blocks ( IB), each of which will contain 16 Small Blocks (Jn), each containing 6 independent events with a probability of success of 62.5%, giving a total of 96 independent events with equal probability p(x) of running.

Let's take the following data as an example:

φ (Odd) = 1.60

k = 6

j = 16

We got $ 175.54 as a result. In this sense, we can say we have a positive value, with two small blocks of success and 14 small blocks of failure.

In another scenario, as the Monte Carlo simulation has shown to be promising, we can use the following parameters as a reference: φ = 1.04; j = 3 and k = 33. We will then have the following table.

Table 9.

Example configuration with j = 3 and k = 33.

Table 9.

Example configuration with j = 3 and k = 33.

| j1 |

j2 |

j3 |

| k1 |

k1 |

k1 |

| k2 |

k2 |

k2 |

| k3 |

k3 |

k3 |

| k4 |

k4 |

k4 |

| k5 |

k5 |

k5 |

| k6 |

k6 |

k6 |

| k7 |

k7 |

k7 |

| k8 |

k8 |

k8 |

| k9 |

k9 |

k9 |

| k10 |

k10 |

k10 |

| k11 |

k11 |

k11 |

| k12 |

k12 |

k12 |

| k13 |

k13 |

k13 |

| k14 |

k14 |

k14 |

| k15 |

k15 |

k15 |

| k16 |

k16 |

k16 |

| k17 |

k17 |

k17 |

| k18 |

k18 |

k18 |

| k19 |

k19 |

k19 |

| k20 |

k20 |

k20 |

| k21 |

k21 |

k21 |

| k22 |

k22 |

k22 |

| k23 |

k23 |

k23 |

| k24 |

k24 |

k24 |

| k25 |

k25 |

k25 |

| k26 |

k26 |

k26 |

| k27 |

k27 |

k27 |

| k28 |

k28 |

k28 |

| k29 |

k29 |

k29 |

| k30 |

k30 |

k30 |

| k31 |

k31 |

k31 |

| k32 |

k32 |

k32 |

| k33 |

k33 |

k33 |

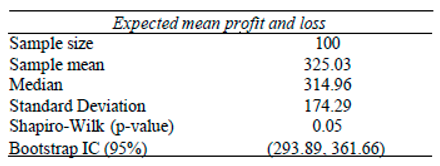

It can be seen, from then on, we will have 100 Intermediate Blocks (IB), each containing 3 Small Blocks (j) with each containing 33 independent events (k) with a probability of success of 96.15%, giving a total of 99 independent events with equal probability p(x) of occurring.

3.1.2. Analysis of the Parameters φ, j, k and the Profit vs. Loss Curve

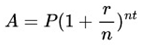

We can say that the parameter φ corresponds to the value of the odds offered by sportsbooks through an expected probability analysis for each independent event k. Therefore, the parameter k is nothing more than the number of n independent events in which the user will repeat using the same odds φ multiplied by the stakes accumulated over time, just as in the general formula for compound interest in the field of financial mathematics.

Through this theorizing, we can expect a great deal of sensitivity regarding the choice of variation in the profit curve as a function of the other variables such as stake, odds containing the probability of success as well as the design of the intermediate blocks through the choice of j and k.

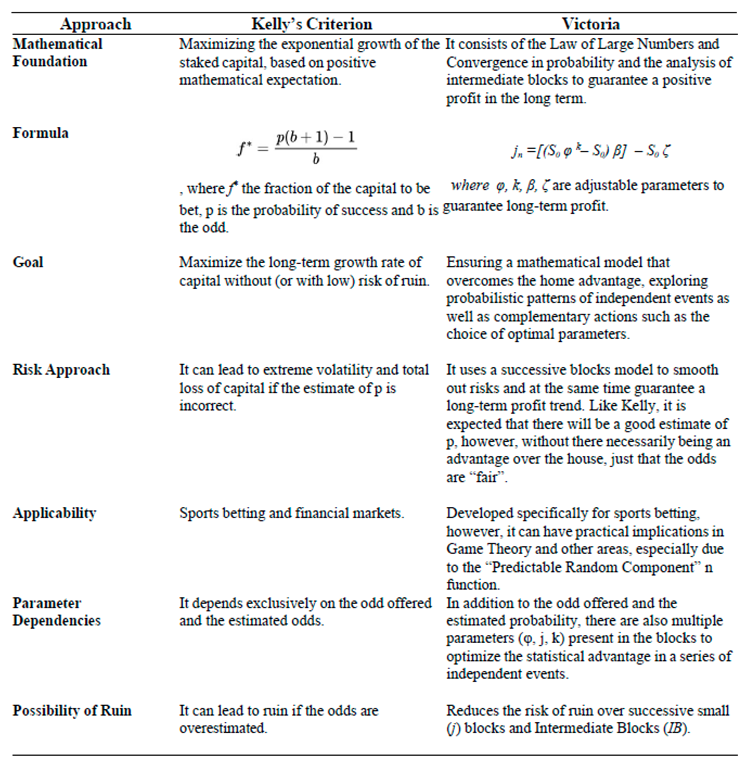

3.1.3. Choosing the Parameters φ, j and k Considered “optimal”

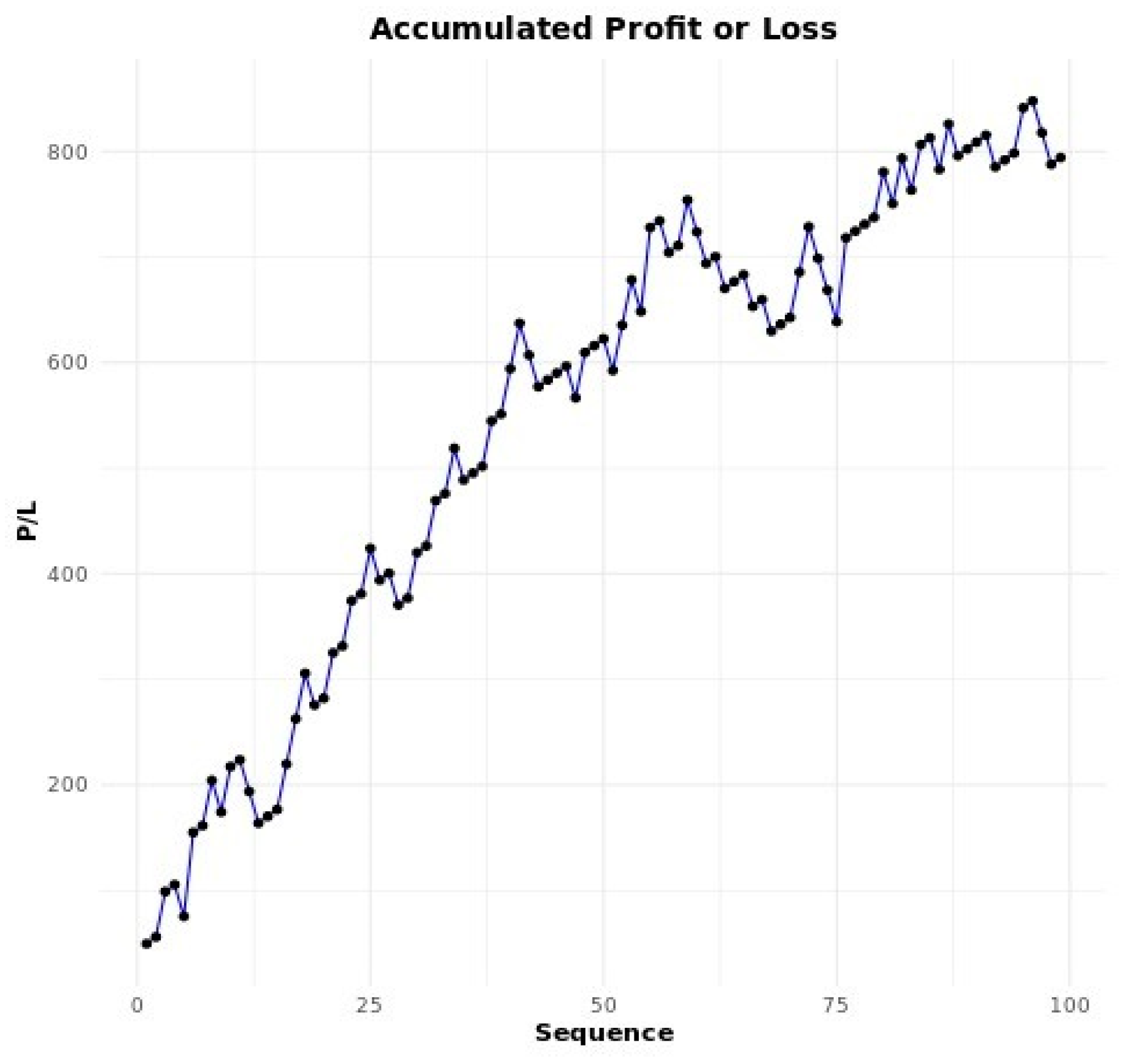

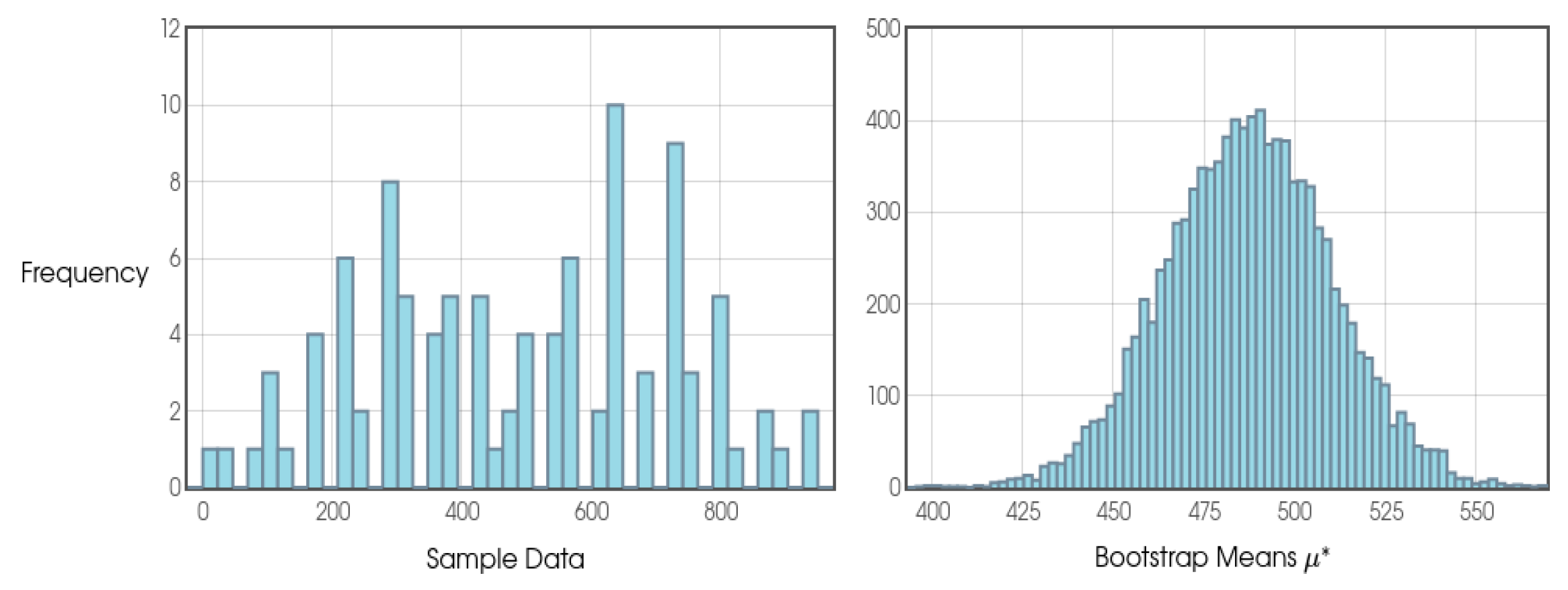

The choice of the parameters φ, j and k considered optimal should be made using trial and error through monte carlo simulation. One way of saying that these parameters have been validated is if the final results from the sum of all the Small Blocks (jn) and Intermediate Blocks (IB), with their cost-benefit ratio compared to all the investment made during the process, show positive final results, i.e. indicating a guaranteed profit for the player regardless of what happens during the sequence.

There are countless possible combinations, even unknown to the author himself at the time of writing this article.

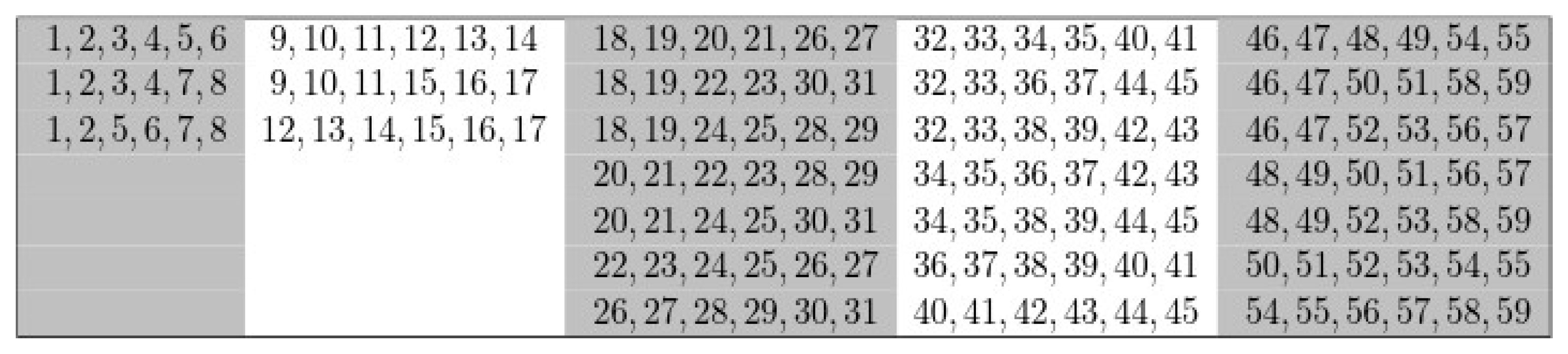

Below are some values of φ, k and j which could be promising for being in the 90%, 95% or even 100% category, regardless of the scenario with n independent event sequences tending to infinity.

Table 10.

Some potential configurations for good long-term results.

Table 10.

Some potential configurations for good long-term results.

| φ |

k |

j |

| 1.02 |

25 |

4 |

| 1.02 |

33 |

3 |

| 1.02 |

50 |

2 |

| 1.03 |

33 |

3 |

| 1.03 |

50 |

2 |

| 1.03 |

100 |

1 |

| 1.04 |

33 |

3 |

| 1.04 |

50 |

2 |

| 1.06 |

33 |

3 |

| 1.07 |

20 |

5 |

| 1.07 |

25 |

4 |

| 1.08 |

25 |

4 |

| 1.10 |

12 |

8 |

| 1.11 |

16 |

6 |

| 1.11 |

20 |

5 |

| 1.12 |

16 |

6 |

| 1.14 |

14 |

7 |

| 1.16 |

12 |

8 |

| 1.4 |

7 |

14 |

| 1.6 |

6 |

16 |

| 1.8 |

5 |

20 |

| 2 |

4 |

25 |

| 3 |

4 |

25 |

| 4 |

3 |

33 |

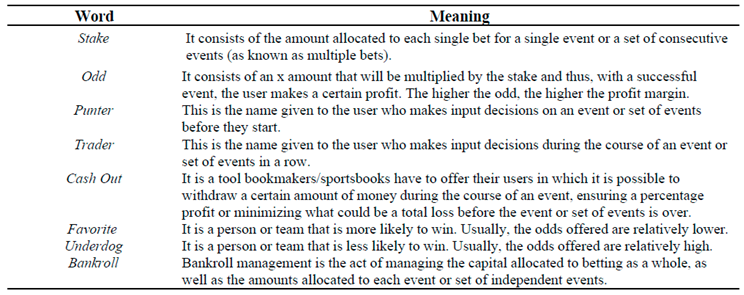

3.3. The Theater of Dreams

Alice and Bob go together to a theater in their city to have some fun. It is known that there are 5 theatrical plays that show how to beat the house using statistics and randomness. Enthusiastic, they are both eager to see not just one but all the performances, no matter if they will stay inside for hours. Below is a list of all the plays that Alice and Bob will be seeing at the Theater of Dreams:

Play I: Beating the house x% of the time and mathematically overcoming any possible losses along the way

Play II: Beating the house x% of the time using some margin of advantage for the player and mathematically overcoming any possible losses along the way.

Play III: Beating the house x% of the time"

Play IV: Beating the house x% of the time using some margin of advantage for the player

Play V “Beacon Hill Park”: Beating the house 100% of the FVs using the Victoria formula (without considering any advantages for the bettor, just that the odds are “fair”) by identifying ideal parameters that always converge to 100%. This is the “singularity point”, an open question in this research.

3.3.1. Play I: Beating the House x% of the Time and Mathematically Overcoming Any Possible Losses Along the Way

The couple realized during this first presentation that the Victoria formula has “almost mathematically perfect” possibilities for gains as there are configurations of φ, j, and k that allow statistical convergence to be greater than or equal to x% close to 100% positive FVs, such as 92%, 94%, and 97%.

In this play, it is presented on stage by the actors that even if it is not always 100% positive, if the category of the configuration is relatively close to this value, we can simply use positive mathematical expectation as well as a time period t and convergence in probabilities to our advantage.

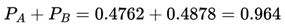

If we consider, for example, that a given configuration of φ, j, and k has a maximum convergence of negative FVs of 4%, we can classify it as belonging to the 96% category, that is, with at least 96 positive FVs out of a total group of 100 FVs, so that in order to mathematically eliminate any possible risk of loss, all Alice and Bob have to do instead of betting a total of 4 FVs is consider betting a total of at least 5 FVs or more. This means that, as we increase the number of k independent events, which results in an increasing number of each Small Block (jn); Intermediate Blocks (IB) and even Future Values (FV), we say that the probability of having FVs with a negative outcome tends to zero.

Still on the previous example, it is known that on average the chosen configuration belonging to the 96% category will have approximately 98 positive FVs and 2 negative FVs. Furthermore, we know that Alice and Bob will have to bet approximately 5,500 games on each Future Value (FV). Based on this information, this means that from k independent event number 22,001, the couple will have mathematically eliminated all possible forms of loss considering the worst possible scenarios, such as having 4 sequences of FVs with negative results, which gives us a probability of (0.04 4 = .000256%) and the profit from that moment on will be ensured by the law of large numbers.

Section 3.4 of this study will present a theorem and a mathematical proof of what was pointed out in Play I presented at the Theater of Dreams.

3.2.1. Play II: Beating the House x% of the Time Using Some Margin of Advantage for the Player and Mathematically Overcoming Any Possible Losses Along the Way

As with Moya's (2012) approach of employing a margin of advantage for the bettor, Alice and Bob realized that by adding this element of advantage instead of simply the ‘fair odds’ offered by the sportsbooks, in rationally logical terms, we can expect that, for example, depending on the advantage established by the bettor over the sportsbook in so-called value bets, a set of configurations that could converge on 94%, for example, could easily get even closer to 100% in terms of the number of FVs with positive results.

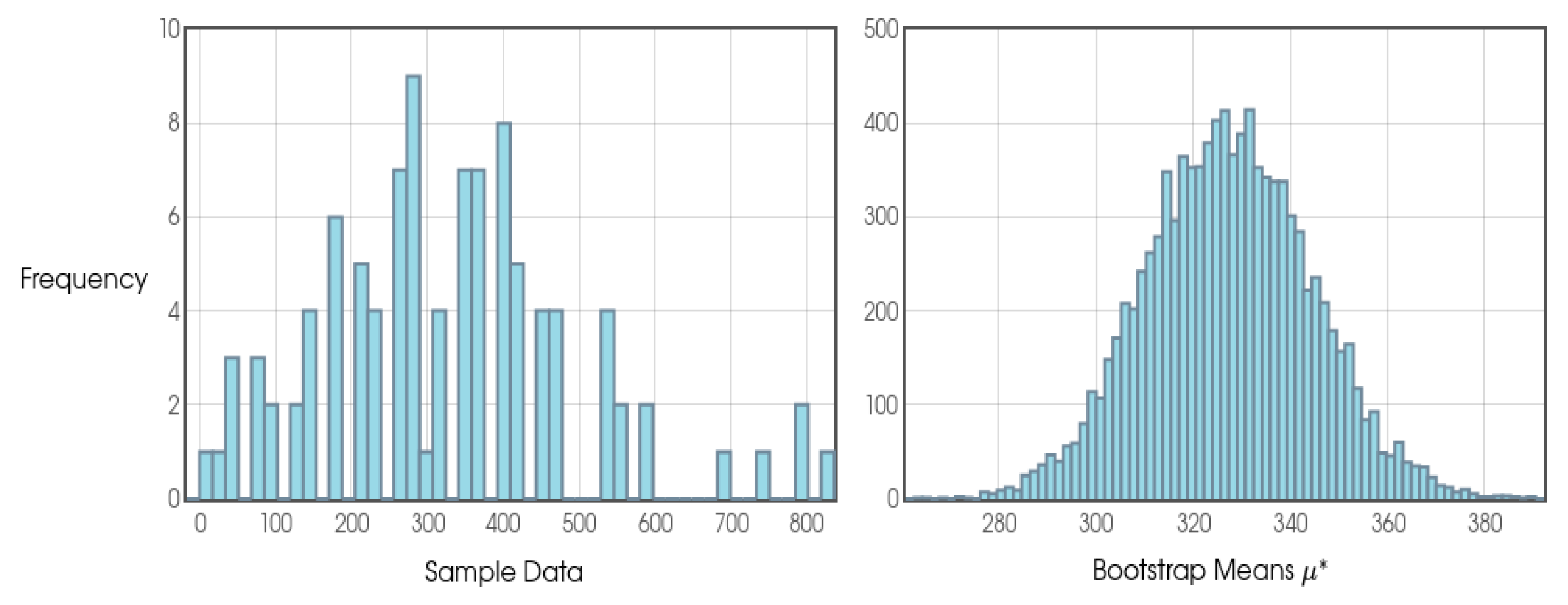

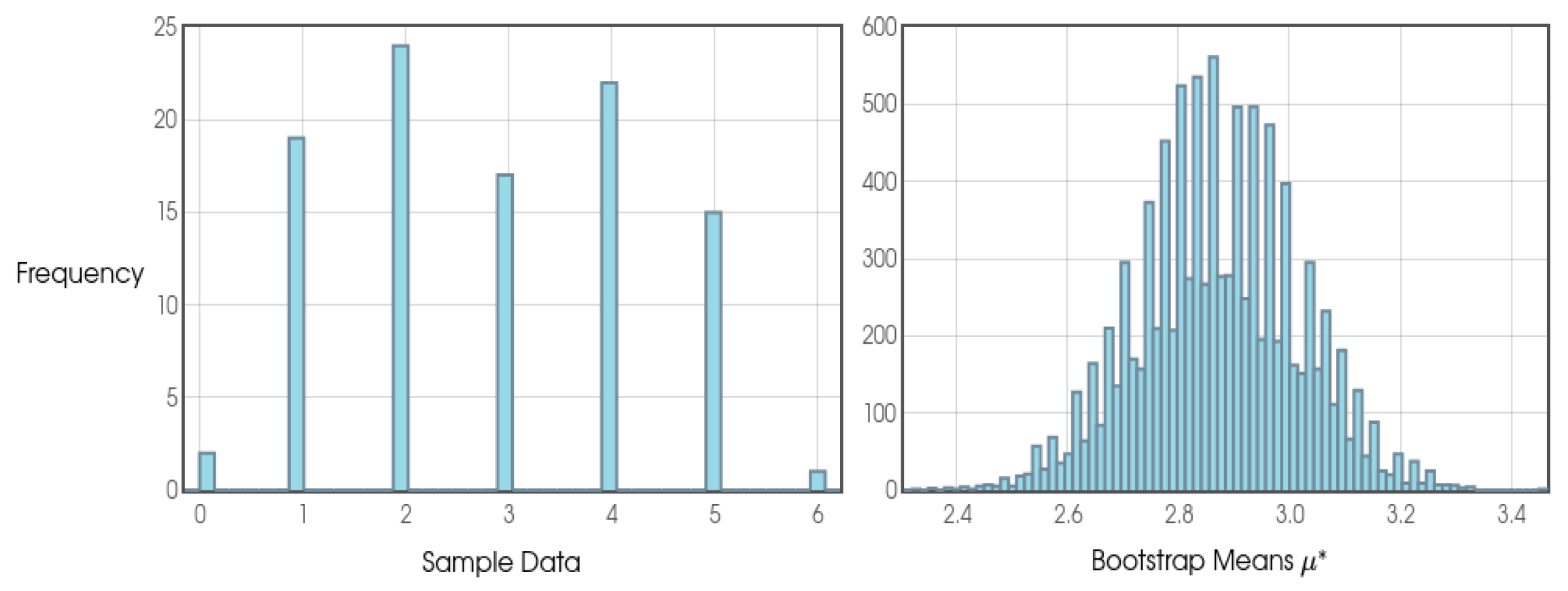

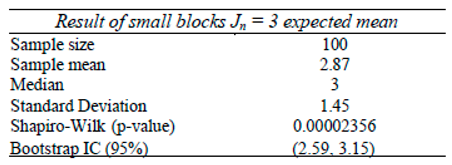

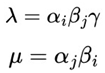

If we take the example of a configuration with φ = 1.04, j = 3, and k = 33, for example, we have a probability of success of 96.15%. Let's also consider that after analyzing market inefficiencies, the odds were “fair” and now Bob would like to apply a margin of advantage over the house by considering φ = 1.03, j = 3, k = 33 as reference values for each Small Block (jn) to be considered successful or not, resulting in a probability of success of 97.09%. This difference of .94% added to the fact that the multiplicative factor of φ = 1.04 will return an even more significant positive net value than would naturally be the case with φ = 1.03, we can say that Bob, as well as being backed by a strong statistical analysis, will also have a small but interesting advantage against the house.

As we can see, if an advantage is placed against the house, it tends to exponentially decrease the time (understood as the number k independent events) needed to make it mathematically possible for the bettor to always make a profit against the house, regardless of all the negative results along the way.

In this sense, if, of course, a certain configuration belongs to the 95% category (understood as 95 out of 100 FVs with positive final values), it could easily come close to always being 100%. Under the same reasoning, if a certain configuration belongs to the 97% category, we could, by applying x% advantage to the bettor, always get a positive result over 100 FVs. In this case, the point of singularity could be reached by using Victoria plus a margin of advantage for the player.

To illustrate the practical impact of a 95% positive convergence configuration in the Victoria methodology, let's consider a hypothetical example in which each Future Value (FV) has a 95% chance of generating a positive result and only a 5% chance (in the worst case scenario) of being negative. In a set of 100 simulated FVs, this implies that, statistically, at least 95 FVs will tend to be positive and, at most, 5 FVs could result in negative values.

We can convert this probabilistic scenario into a design similar to that of a lottery, where the player fills in a ticket with 5 numbers between 1 and 100. In this case, numbers equal to or greater than 96 are considered “losing numbers”, resulting in negative FVs. The probability of the worst-case scenario occurring - that is, getting exactly 5 consecutive negative FVs within a set of 100 FVs - can be calculated as a compound probability:

in other words, the chance of facing a sequence of 5 consecutive losses in a 95% efficient configuration is only .00003125% - an extremely small value, indicating a rare but still possible event.

On the other hand, if we consider a sequence of 5 FVs and we have 3 FVs or 4 FVs with some negative final result, indicating some degree of loss for the bettor, despite this - the other 2 FVs or just one positive FV - still tend to provide final values with profits substantially higher than the losses that occurred, so the bettor can still come out with a profit depending on the configuration of φ, j and k chosen.

3.3.3. Play III: Beating the House x% of the Time"

After the first three plays, Alice and Bob decided to go outside for a while to a kiosk outside the theater and began to reflect on everything they had experienced in that environment full of numbers and statistical magic, above all reflecting on the third play.

Another common scenario for expecting profits and beating the house is through the simple approach of the Victoria model and its respective belonging categories. If a given configuration of φ, j, and k converges to 85%, 90% or 97%, this means that we can expect to obtain, in the worst-case scenario, 15, 10 and 3 negative FVs, respectively, in each group of 100 FVs.

Let's still consider the previous examples. At this point, when the victorian bettor enters the market and puts the Victoria formula into practice, he can expect that the odds of him coming out with a positive FV will probably be something close to an average of 92.5%, 95% and 98.5%, respectively. Under the same reasoning, the bettor is also aware that these certain configurations are “almost perfect” and can present a very interesting cost/benefit ratio.

At this point, unlike plays I and II, where the aim is to mathematically eliminate all possibilities of losses (although this is relatively low and rare), this bettor is willing to take a small risk of getting sequences that could turn negative. As we saw in the previous sections, even if the bettor gets a few sequences of negative FVs, with the remaining positive FVs - depending on the settings chosen - the bettor can still make a satisfactory profit.

3.3.4. Play IV: Beating the House x% of the Time Using Some Margin of Advantage for the Player

The couple return to the Theater of Dreams to watch a new play and look forward to the long-awaited final performance. It is known that in Play IV, the idea is basically the same as in Play II, however, the main difference lies in the fact that in Play II the aim is to mathematically eliminate any possible loss when applying the Victoria model as well as adding any possible margin of advantage if the bettor wishes.

In Play IV, the margin of advantage sought by the bettor does not necessarily aim to always achieve 100 positive FVs out of all possible 100 FVs, but rather to apply that advantage to simply be closer to 100%.

This issue can become clearer if Alice and Bob, for example, find a certain configuration of φ, j and k that always converges to at least a category of 88% which, with an x% advantage applied to the player (if they wish and it is feasible to do so), can mean that instead of converging to this normal value expected by Victoria, it can converge to a new category, such as 94%. As a result, the objective in these cases could be to take advantage of the average cost/benefit presented in each positive FV of this initial category, which with an x% advantage not only increases the average profit expected in each FV, but also tends to considerably reduce the number of expected games.

3.3.5. Play V: Beacon Hill Park (Singularity Point)

In this final play, set in Beacon Hill Park, Alice and Bob are asked to find a “singularity point”, that is, an optimal configuration in the Victoria formula (without taking into account any margins of advantage for the bettor) that mathematically demonstrates that there will always be FVs with 100% positive results out of 100 FVs in a row, regardless of the time lapse. This is probably a question that will remain open when we talk about the Victoria methodology.

Determining these values would be fundamental in the sense that both have a smaller number of possible games to bet on and, consequently, become very viable in practice because they require less time. If we were to find these optimum configurations belonging to the singularity point, a Victorian punter, for example, would only have to hope to play 'only' between 4,800 and 7,000 games at most to mathematically secure some positive value. Surely, if we can prove it in the future, this will be a transcendental event in this theorizing.

Conjecture:

Would it be possible, using the Victoria methodology, to determine optimal configurations of the parametersϕ, j, and k that belong to a possible “singularity point”, where the cost-benefit ratio between the number of successful and failed Small Blocks (jn) within Intermediate Blocks (IBs) would guarantee, in a consistent and invariable way, that 100% of the Future Values (FVs) result in a profit over each set of 100 FVs?

3.6. Victoria and the Game Theory

3.6.1. A Brief Reflection on Some Socio-Economic Aspects and the Proposal for an Economic Model Based on Science and Statistics

Well, throughout this study, it has been a challenging task. I was expected to finish it in just over seven months. However, I have suffered a lot of pain from a deficiency of some vitamins, especially vitamin B12, which was at levels considered very serious to the point of strongly affecting my mind and nervous system. As a result, I had to postpone and complete this study by a little over ten months. I've always been overly curious and thinking about this issue, so when I went home from the medical center comfortably numb, I reflected a little on some socio-economic issues, such as:

Could factors such as the higher the rate of the population with a satisfactory nutritional base (in terms of vitamin balance...) in the body have a positive influence on a higher quality of life, to the point of preventing and minimizing the impact of diseases? How could such a nutritional base influence the process of generating wealth for nations over the years in the medium and long term? Could these countries be more socially and economically developed than others whose populations have a lower percentage of citizens with a satisfactory nutritional base?

Could socio-urban aspects such as countries that have higher rates of sidewalks and other organized and standardized constructions positively influence quality of life indices as well as the process of wealth generation for nations over the years in the medium and long term?

As far as the first question is concerned, Fontaine et al. (2003) carried out an in-depth study on diet as well as other hereditary factors, considering different categories such as age, ethnicity and analyzing how Body Mass Index (BMI) could also influence the metric of Years of Life Lost (YLL). Overall, the study came to the conclusion that overweight has a significant impact on quality of life, especially among younger people.

This premise raised as imagined is not new and I was very excited by the results found through the study by Wang and Taniguchi (2002) which indicate that improving nutritional status has a positive and significant impact on long-term economic growth. In particular, we can estimate that an increase of 500 kcal/day in the average supply of food energy per capita can increase the growth rate of real GDP per capita by approximately 0.5 percentage points. This effect is particularly significant in East and Southeast Asian countries, where the magnitude of the impact can be up to four times greater.

Furthermore, Wang and Taniguchi (2002) also point out that However, for other developing economies, the relationship between nutrition and growth tends to be negative or statistically insignificant in the short term, possibly due to the dynamic interactions between population growth and labor productivity. These findings suggest that policies aimed at reducing malnutrition can generate not only humanitarian benefits in terms of quality of life, but also significant gains in terms of sustainable economic growth. Ogundari and Aromolaran (2017) through their case study in sub-Saharan Africa also found significant results regarding the correlation between better levels of nutrition and an increase in a region's GDP.

With regard to this question about socio-urban aspects, it is assumed that the lack of standardization, for example, of sidewalks and streets, can mean that each citizen, whether on foot or in their vehicle, requires a little extra energy to observe, reflect and act in the face of disorganized environments with too many obstacles in front of them, whether they are commuting to work, going home, or simply going shopping.

The question that remains is what could be the impacts on both the quality of life of each citizen and the economy of a nation, a city that has high rates of disorganization of its public roads could bring over a year, 5 years, 10 years, 30 years?

What should be clear and understandable in this questioning is that these small amounts of energy demanded are nothing more than “human depreciation”. In the long term, these people could have more vitality and time to deal with other issues, whether for their own personal well- being or even with this “saved” energy, they could be in a position to contribute even more to generating wealth for their local community, whether through working more on projects for their own self-realization or developing new technologies and knowledge that could generate added value and be patentable.

During this time, people traveling on public roads in a disorderly manner can lead to higher rates of accidents and even deaths, and consequently tend to increase public spending on the health sector, which is even more sensitive for those countries that have a unified health system. Once again, the sum of these avoidable accidents over the long term could prevent new investments in other sectors.

This relationship between the socio-urban aspects theorized here is not new, but has also been addressed by other authors such as Khalil (2012), who emphasizes that Gross Domestic Product (GDP) should not be seen as the main tool for assessing a population's level of well- being. The author investigates how strategic urban planning can be a tool for increasing the quality of life perceived by citizens.

Another interesting study was by Deng et al. (2018) in which we see that urban planning has a significant effect on controlled urban growth within the Special Economic Zone (SEZ) as was observed in the case study in Shenzhen, China.

The case study observed on Chaharbagh Abbasi Street in Isfahan, Iran, by Shahmoradi et al. (2023) shows that pedestrianization can initially have negative impacts, such as the closure of 27.5% of traditional businesses and the stagnation of sales and job creation. However, in the medium and long term, it has shown promising potential for increasing economic activity, as pedestrian traffic has increased by 64% and new food and beverage outlets have increased by approximately 60%. As the authors emphasized, the results found in this region can be better analyzed in other contexts to see if this practice, considered sustainable, can promote both the health and well-being of citizens and expand the local economy.

In addition to these two questions, there is a third: could countries in which Sportsbooks have lower annual revenues than other countries (in percentage terms) somehow at the same time imply a population that is better educated about personal finance and knowledge of statistics?

Could we measure this and create new economic metrics from this point? In fact, we must also take into account that correlation does not imply causality, but it could be an invitation to analyze variables that deserve to be better investigated in detail.

Furthermore, as Banerjee and Duflo (2011) put it in their study on new economic perspectives for minimizing poverty through the understanding that as human beings interacting with the natural world we result in complex systems, perhaps we should look more at the details and particularities of each place to understand the reasons for “poverty” instead of coming up with economic models with the aim of generalizing across the globe.

Douglass et al. (2024) demonstrated how statistics can be present and impact on results in Olympic Games. Mesquita et al. (2010), using data analysis and statistical techniques, analyzed the climatic properties of extratropical storms in the North Pacific Ocean and the Bering Sea, regions known for their high cyclone activity and storm tracks. Thus, Political decisions should be focused on statistics and science rather than political ideologies which tend to lead us into a game whose payoff will be negative and/or at best a relatively slow growth in human progress. By asking these simple questions and redirecting the way we think about the natural world and our interaction with it, we can surely make relevant discoveries that could lead to a fairer world with a better quality of life for everyone.

3.6.2. Predictable Random Component Function (η(Xt))

Assumptions and definitions:

Consider a game G with N players g1, g2, ..., gN.

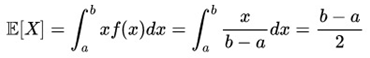

Randomness in the game follows a uniform distribution U(a,b).

The η(Xt) (Predictable Random Component) function represents the factor that connects the player's knowledge to their ability to exploit randomness and other additional actions.

Each player gi has a strategy si and an expected payoff [πi].

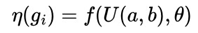

Definition of the η(Xt) function:

where

θ represents statistical parameters derived from observations of the

U(a,b) distribution.

Below are some of the conditions of the problem:

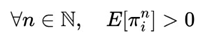

Each player g

i, using his advanced knowledge of randomness and mathematical or physical operations, defines a

strategy that ensures that in the long term his expected payoff will be positive.

After n sequences of moves, the

strategy guarantees that [π

i ] > 0, regardless of the behavior of the other players.

In formal terms,

for gi, we define η:ℝk → ℝ, where η is a function that incorporates:

The player's knowledge of the uniform distribution U(a,b);

Mathematical operations f(x), physical operations h(x) or any other cognitive action.

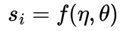

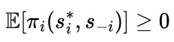

Since the objective is always to guarantee a positive value, the si strategy must satisfy the following condition:

This means that, regardless of the conditions of the game and the strategies of the other players, the application of the η(Xt) function must ensure that the cumulative sum of the returns is never negative.

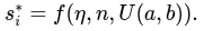

For each player gi, we define a strategy si that depends exclusively on the function η(Xt):

where

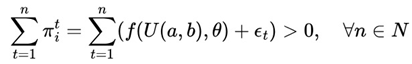

f is a statistical function constructed to guarantee that, for any sequence of

n rounds:

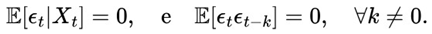

where

ϵt is a random error with E[

ϵt] = 0, which represents short-term fluctuations, but does not affect the positive long-term trend.

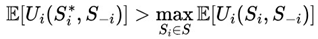

Positive expected payoff condition: For any n∈ℕ:

Dependence on the η function:

The si strategy depends on the η(Xt) function, i.e:

Under these conditions, player gi can guarantee a positive expected payoff in each sequence n, regardless of the opponent's strategies.

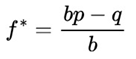

The Predictable Random Component approach redefines the player's strategy by focusing on the sustainability of returns with positive payoffs, unlike approaches such as the Kelly Criterion that seek to optimize the expected gain, the η(Xt) function (or fv(Xt) function in the context of VNAE) establishes a strategy where the rigorous application of the statistical model guarantees that E[πi] > 0 always, providing positive cumulative growth over time.

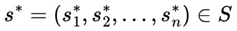

3.6.3. Victoria-Nash Asymmetric Equilibrium (VNAE)

Let a stochastic game be formalized as a tuple: G = (N, S, U, P),

where,

N = {1, 2,..., n} represents the set of players;

Si is the set of strategies available to each player

i;

Ui :

S →

is the utility function of each player;

P is a probability distribution that models the randomness present in the game.

fv(Xt) = The fv(Xt) or η(Xt) function (or simply, η or fv function) refers to the fact that within a game in which the randomness factor in a uniform distribution is crucial to it, any player who has advanced knowledge of randomness added to other additional actions, whether with the support of statistics, mathematical and/or physical operations, will be able to determine an optimal strategy whose results of the expected value of the player's payoff will always be positive regardless of what happens after n sequences determined by the player.

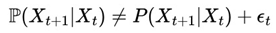

We define a stochastic process Xt associated with the game, where the dynamics of states follows a distribution P(Xt). We assume that:

In “

Predictable Random Component” there is a function

such that:

where

εt is a random residue uncorrelated with

Xt and

fv(

Xt) is a transformation that allows us to predict certain structurable patterns within the randomness.

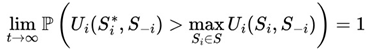

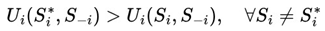

It is important to mention that in the convergence in probability of the optimal strategy there is a strategy

such that:

this implies that player i can maintain a continuous statistical advantage over time.

Theorem: If there is a function

fv(

Xt) such that the randomness of the game shows partial predictability, then there is at least one player

i with a strategy

that allows continuous advantage, shifting the equilibrium to an asymmetric state.

As a way of demonstrating this, we can apply, for example, the fixed point theorem whose references to Brouwer (1911) and Banach (1922) as well as Markov processes.

First, let's approach this proposed model from the perspective of the fixed point theorem.

Let

G = (

N,

S,

π) be a stochastic game, where N represents the set of players,

S1 ×

S2 × ... ×

Sn is the space of available strategies and

πi : S × X →

is the payoff function for each player

i.

It is also assumed that each player can choose a strategy

si∈

Si and that

Xt ~

U(

a,

b) represents a stochastic process with uniform distribution in the interval (

a,

b). A predictable function

fv(

Xt) is defined, representing the structurable component of randomness, so that a player's payoff function is given by:

where

gi(

s,

Xt) is a continuous function and

εt ~

U(

c,

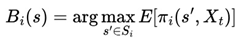

d) represents random noise. We can define the best response function as

B(

s), which returns the optimal strategy for a player, given the strategy of the other players, as

The aim is to demonstrate that there is at least one set of strategies

such that

To establish this result, we use Brouwer's Fixed Point Theorem, which guarantees the existence of at least one fixed point for any continuous function defined over a convex and compact set, since it is a closed and bounded subset of

n

n, and convex, since it allows mixed strategies.

In addition, it should be clear and understandable that the continuity of the best response function

B(

s) follows from the continuity of

gi(

s,

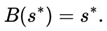

Xt) and the linearity of the mathematical expectation. Since B(s) is a self-mapping function in S, satisfying all the hypotheses of Brouwer's Theorem, it follows that there is at least one

such that

guaranteeing the existence of an asymmetric Victoria-Nash equilibrium where a player can exploit predictable patterns of randomness in a sustainable way.

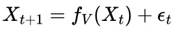

Let’s consider the dynamics of the game as a Markov process where the state Xt evolves according to:

where,

fv(

Xt) captures structurable patterns within randomness, while

εt is the uncorrelated random residual, defined by:

This means that εt is a purely random term and therefore has no temporal correlations.

The maximum “predictability” has already been extracted by fv(Xt), i.e. the entire exploitable and expected pattern of true randomness has been identified. What remains (εt) is truly unpredictable, which we can say is the majority, demonstrating that the advantage exists, but there is a statistical limit to exploiting it.

By hypothesis, fv(Xt) captures part of the random structure of the game, making Xt partially predictable.

If

Xt is partially predictable, then there is a strategy

such that:

This means that player i can adjust his strategy according to exploitable patterns of randomness, ensuring that his expected utility is consistently higher.

We can define the new equilibrium as

a state where:

this means that player i maintains a long-term advantage, even if the other players optimize their strategies.

Since this advantage cannot be neutralized by the other players, the game converges to an asymmetric state in which player i sustains a continuous strategic edge. This result deviates from the classical Nash Equilibrium, which assumes that no individual player can maintain a persistent advantage and that all participants operate under conditions of strategic parity.

As we can see, the VNAE has some implications for Imperfect Information Games, since it modifies the conception of imperfect information games by suggesting that randomness can be partially predictable for certain strategic agents.

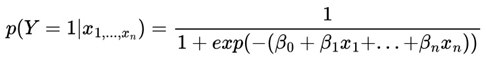

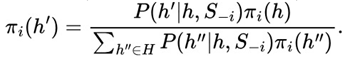

Let G′ be an imperfect information game, where each player i has subjective beliefs πi(h) about the historic h of the game. Traditionally, these beliefs follow the Bayesian updating rule:

However, if P is structurally partially predictable under fV(Xt), then classical Bayesian updating can be replaced by a 'deterministically adjusted' version, where certain events can be anticipated and/or expected in the long term due to factors such as convergences in probabilities, for example. This changes the expected strategic behavior in financial markets, betting and other decision games in different areas in which the randomness factor is an important basis for the system.

Although it still maintains the basic essence of the Nash Equilibrium, in VNAE the idea of a “fair” and symmetrical equilibrium as we can see no longer exists, because exploitable predictability alters the structure of the game in which one of the players tries to respond by minimizing their disadvantage.

Despite its asymmetrical nature, it is also important to think about two possible scenarios:

- I.

the central idea of the VNAE in which one side will always have a structural advantage through the fv function, thus leading to an inevitable and immutable asymmetric state and;

- II.

the response of the players at a disadvantage being able to adopt a minimization strategy and, depending on this, reach a new equilibrium and/or advantage for one of the sides at another point.

In fact, the Victoria methodology redefines the structure of strategic equilibrium by demonstrating that randomness can be exploited for sustainable advantages within stochastic games. The Victoria-Nash Asymmetric Equilibrium proposes an extension of game theory by integrating statistical predictability into games with uncertainty, as opposed to the idea that optimal strategies always converge to stationary states of no advantage.

In the framework of the Victoria-Nash Asymmetric Equilibrium (VNAE), despite the presence of structural asymmetry, a given player can sustain a long-term strategic advantage

without the possibility of complete neutralization by opposing agents. Its equilibrium consists of its transformation into a new state, in which statistical predictability - combined with additional physical and/or cognitive strategic adjustments (such as advanced knowledge of randomness in a uniform distribution and some mathematical and/or physical operations, for example) - fundamentally alters the underlying dynamics of the game.

Victoria through the fv(Xt) function by allowing sustained advantage, then the dynamics of the game change to a state where that player becomes dominant. However, this dominance, as stated above, may not be absolute, since there may be scenarios in which the other participants or external factors may adopt strategies (for the purpose or not) of mitigation, creating (again) a new equilibrium structure and even changing the rules of the game which, in this case, would not only modify Victoria-Nash but also the Nash equilibrium itself in its essence.

The idea presented here is just a simple start for something that needs to be further developed, especially considering practical applications in various other areas of science, from information security to artificial intelligence and biology, for example.

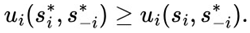

3.6.4. Victoria-Nash Asymmetric Equilibrium (VNAE) in a Nutshell

Let there be a stochastic game G with N rational players, where each player i chooses a strategy si ∈ Si to maximize his expected payoff. In this model, we consider the existence of a predictable random component fv(Xt) within the randomness allowing a player to explore statistical patterns given a uniform distribution and employ complementary actions such as using mathematical operations, physics and/or any other cognitive actions.

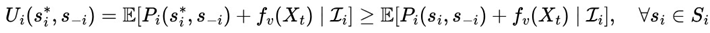

Formally, a set of strategies

constitutes a Victoria-Nash equilibrium (VNAE)

if, for each player

i, there is a predictable random component

fv(

Xt) such that its optimal strategy

maximizes the expected payoff conditional on this predictable structure of randomness. Below is its formulation:

Ui(

) : player

i's expected payoff when choosing the strategy

.

Pi(si, s-i) : Traditional payoff function, based on the interaction between the players' strategies.

fv(Xt) : predictable component within the randomness of the game, allowing statistical patterns to be identified.

: set of information available to player

i at the time of the decision, which influences his/her strategic choice.

This formulation implies that, in a Victoria-Nash Asymmetric Equilibrium, certain players can gain sustainable long-term advantages by identifying predictable patterns within the randomness of the game, which leads them to an asymmetric equilibrium.

As we can see, if fv(Xt) is relatively small or zero, the VNAE can converge to a Nash Equilibrium.

Impacts can be expected in stochastic games, zero-sum games, asymmetric games, repeated games, imperfect information games as well as an extension of Nash Equilibrium and Bayesian Equilibrium, for example.

3.6.5. Victoria-Nash Asymmetric Equilibrium General Applications

As we saw earlier, there is a function fv(Xt) that allows us to extract and partially predict the randomness in a stochastic game, specifically, considering a uniform distribution. In summary, what should be clear and intelligible is that through the function η(Xt) (or fv(Xt) in the context of the Victoria-Nash Asymmetric Equilibrium):

the model expands the classic concept of equilibrium by incorporating partial predictability of randomness as an integral part of strategy,

this scenario leads to one player managing to maintain a sustained strategic advantage over the long term,

this advantage leads us to an asymmetric state in which one side has a structural advantage after applying a dominant strategy through the fv(Xt) function (Predictable Random Component),

It modifies the structure of zero-sum games and imperfect information games, creating new forms of strategic equilibrium.

however, there is the possibility of other players trying to mitigate this advantage as well as leading to a possible new equilibrium and/or an advantage for one side at another given point.

The model departs from the classic Nash Equilibrium, as it allows for a structurally asymmetrical and potentially dynamic state. Even though it is an asymmetric equilibrium, players rationally continue to maximize their strategies within the game, maintaining the basis of the central principle of the Nash Equilibrium.

The η(Xt) function as well as the Victoria-Nash Asymmetric Equilibrium can have practical applications in the biological sciences and ecology through a variety of studies, from modeling bacterial cultures, tumors, to analyzing behavior patterns in animals (based on 'instinctive rationality' through biological reinforcements and survival through natural selection) in which the randomness factor and uniform distribution can be present as a basis for study.

Following the same reasoning, the identification of lottery designs in which there can be positive mathematical expectation for the player. Although the author didn't go into it in depth, I have noticed this issue and the real possibility that some lotteries around the world (especially those whose designs lead to more accessible jackpot odds for a player with a single ticket to win)

- may be theoretically 'vulnerable' to victorian players employing convergence in odds as a decision-making tool, as other colleagues have also presented similar results over time, as in the case of Stefan Mandel and, more recently, by Stewart and Cushing (2023). The same thought applies to other random games such as roulette: probably the only way for a player to be a winner using statistics (and not relying on physical deviations of the roulette wheel and/or PRNG algorithms used in digital roulettes) is to deeply understand the convergences in probabilities added to other complementary actions, as well as counting on the monetary values per bet and returns also being favorable to him.

In the groundbreaking work "Mick Gets Some (The Odds Are on His Side) (Satisfiability)" by Chvátal and Reed (1992), the authors explore probabilistic properties of random Boolean formulas within the k-SAT framework, establishing critical thresholds for satisfiability and demonstrating the probabilistic dynamics underlying solution spaces. By leveraging advanced algorithms such as Unit Clause (UC), Generalized Unit Clause (GUC), and Shortest Clause (SC), the study reveals how structural randomness in clause-variable relationships can lead to high-probability satisfiability outcomes under specific configurations.

As we can see through Chvátal and Reed (1992), the probabilistic approach to satisfiability resonates with the principles underlying Victoria-Nash Equilibrium, particularly in its focus on exploring predictable patterns in stochastic environments. In this sense, we can expect contributions from VNAE to future studies in the area of computing and optimization in this direction.

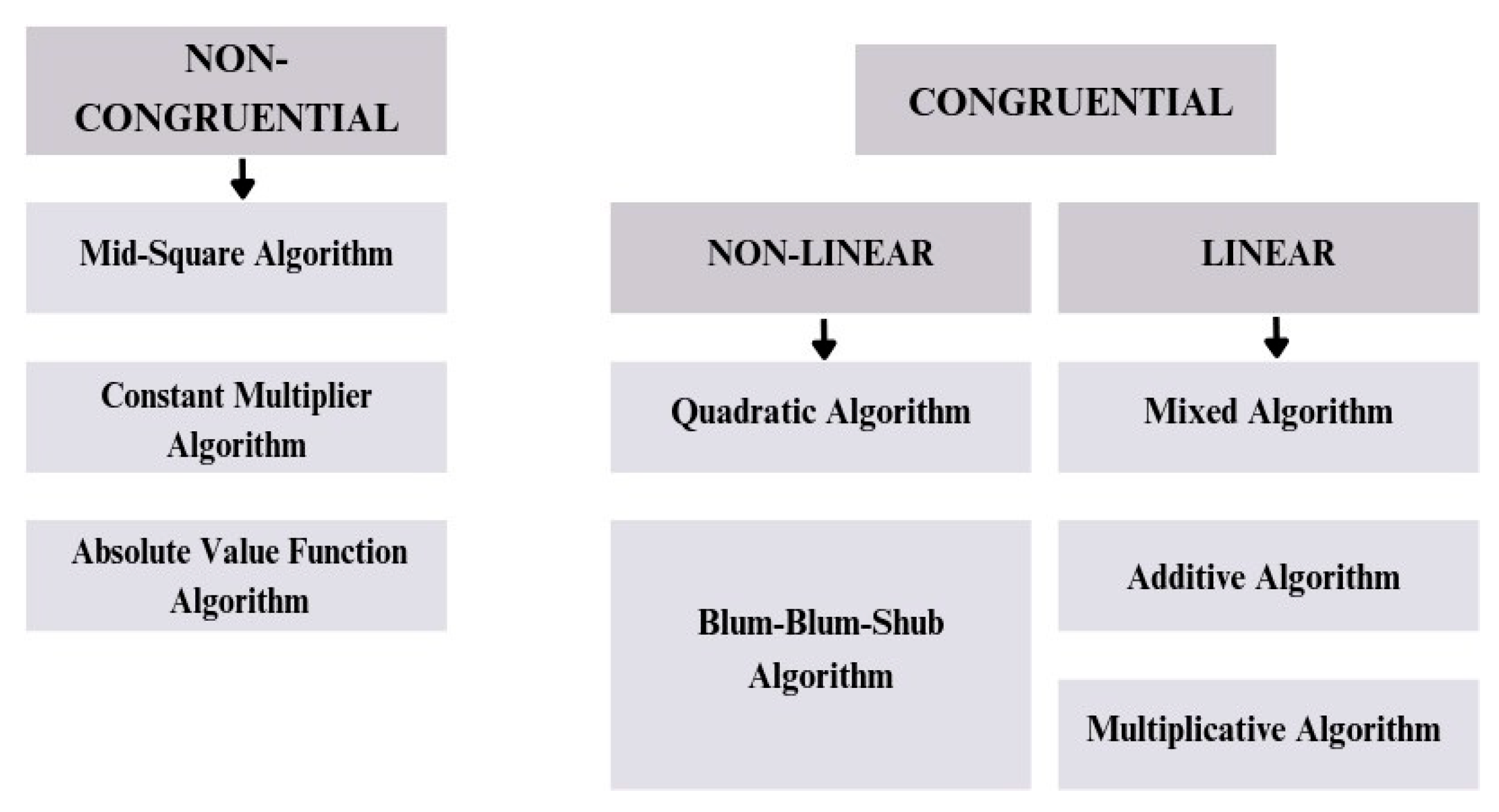

In addition to the aforementioned environments, it is also hoped that, based on the same principle of the η(Xt) function, applications in the field of cryptography may also be possible, to a certain extent, especially in terms of trying to reduce the number of possible combinations in randomization algorithms, which this study can provide as an additional focus for professionals in this field.

In economic systems, especially in financial markets, the existence of the Victoria-Nash Asymmetric Equilibrium may be present in possible applications of hedge funds considering different types of investment markets.

Considering that one of the fundamental bases in areas such as data science and artificial intelligence is the identification of patterns that can result in a descriptive or predictive model, as we can see in the recent paper by Martins and Papa (2023) in which they present a new clustering approach based on the Optimum-Path Forest (OPF) algorithm. In this sense, we can also expect that Victoria and its respective ‘equilibrium’ could provide new perspectives for this field, helping to identify patterns and make decisions.

Furthermore, through the field of study of Neutrosophic Statistics formalized by Smarandache (1999) and Smarandache (2014) as an extension of Classical Statistics that incorporates the indeterminacy factor (I) in probabilistic models, it is also believed that Victoria could also have applications in this sense and, adapting to this emerging field, the predictable random component can be defined as:

“Truth” p(T), ‘Indeterminancy’ p(I), and ‘Falsity’ p(F) represent the neutrosophic components of an uncertainty distribution in a strategic game;

ξ represents an uncertain but partially modelable component and ε represents pure random error.

There is also a positive expectation for practical applications within the field of physics studies, especially in dynamical systems where they have strong approaches to finding patterns in chaotic systems. Furthermore, Victoria-Nash Asymmetric Equilibrium in several other subfields - from meteorology, plasma physics and nuclear fusion control to quantum mechanics and non-linear optics - can help exploit asymmetric advantages and optimize complex systems. It is therefore believed that it can open up new avenues for control, efficiency and innovation in various fields of physics.

Mathematical modeling as well as randomization is very present in studies in the field of biological sciences and ecology, as can be seen from Johnston et al. (2007) when applying mathematical models to model colorectal tumors, for example. As we can see from the study presented by French et al. (2012), in randomised clinical trials the allocation of patients between treatment and control groups is designed to be completely random in order to reduce bias while ensuring statistical validity. However, the VNAE suggests that, even in this context, there may be predictable structures in the response to treatment, which can be explored mathematically.

Convergence in probability tells us that as the number of observations increases, the sample means of a specific subgroup get closer to an expected value. In this way, even in an environment where randomness dominates allocation, certain patients may show predictable patterns in their response to treatment, making it possible to anticipate the behaviour of certain subgroups.

Let Yi be the response to treatment of patient i. We can model this response using the following formulation:

μ : represents the expected mean response to treatment;

ηi : represents a predictable random component within the randomness of the group to which the patient belongs;

εi : represents the random error or ‘random noise’ (the part of the randomness that cannot be tamed)

If convergence in probability is valid, then for a specific subgroup G, we have:

In addition, identifying these predictable patterns can help correct structural biases in randomization. In fact, certain factors such as genetic factors, age and previous medical conditions can influence the response to treatment in a systematic way, creating a bias that can compromise statistical inference. In any case, VNAE can make it possible to model these structural variations, improving the interpretation of results and optimizing decision-making in clinical trials.

The approach proposed in this study may make it possible to adjust statistical analyses to take into account the predictability that exists within randomness, ensuring that conclusions about, for example, the effectiveness of treatment are more robust and representative of reality. Here, instead of using the function fv(Xt) with the aim of the gambler generating consistent profits against other gamblers as well as against the ‘house’, we simply convert it into the mathematical-medical language in which health professionals will ensure that patients obtain additional asymmetrical advantages in dealing with their respective illnesses.

As we can see, this is still a new study and therefore new perspectives for practical applications will emerge over time. In this sense, the entire academic community is invited to discuss and delve deeper into this theorization of Victoria in their respective areas of expertise, especially those in which I do not have relevant knowledge such as physics and biological sciences and that I am unable to draw any assertive conclusions in this regard and that these colleagues will surely do a better study than me.

3.6.6. Social Science Applications of the Asymmetric Victoria-Nash Equilibrium

The presence of randomness in social games can be modeled by a uniform distribution Xt

~U(a, b), representing the uncertainty inherent in human existence and human interactions, such as variations in individual preferences, access to resources and opportunities and the impact of unpredictable external factors. Nevertheless, within this randomness, certain rational agents can exploit predictable patterns, gaining a sustained strategic advantage over time.

The Victoria-Nash Asymmetric Equilibrium (VNAE) describes this asymmetry by incorporating a predictable component fv(Xt) within the stochastic structure of the game, allowing individuals or groups to maintain continuous influence even in environments subject to random fluctuations. This is because, although social decisions have a degree of uncertainty, certain structural attributes - such as economic capital, networks of influence, dominance over communication channels - create a systematic bias that favors agents with a greater capacity for foresight and strategic adaptation.

In this context, elements known as natural gifts, charisma, talent, long periods of training, and structural inequalities act as factors that allow partially predictable patterns to be identified and exploited in social interactions. Individuals with superior communication skills, for example, can 'predict' and influence group behavior, consolidating leadership positions in social networks and negotiation practices. Similarly, in the global economy, nations with industrial and technological superiority have predictable advantages over emerging countries, being able to anticipate strategic positions and reactions and adjust their policies to maximize gains, even in the face of external uncertainties.

As we can see, when applied to social science contexts ranging from psychology and sociology to interpersonal relations and geopolitics, the concept of predictable patterns of randomness consists of the sum of natural advantages (or a person's natural gifts and talents) and structural advantages (in terms of resources and access to opportunities), as well as the ability to identify environmental and social patterns to increase their payoff.

In sociology, for example, sensitive topics such as access to education can become an example of how certain social groups with greater access to information and 'elite education' undeniably tend to have an asymmetrical advantage over other players in the same game. Even if a student from a 'poor education system' comes to be at the same level as others over a period of time, those belonging to the elite education group can still remain with a constant structural advantage over time.

In the social environment, the impression we may have that the positive results of something don't matter, but rather who presents them, can be modelled and explained by a mathematical model that shows asymmetrical advantages for one side.

When analyzing social inequality from the perspective of game theory, it becomes even more necessary to debate how public policy can offer equal opportunities to all rational agents in this game called real life. Other sensitive topics, such as income distribution, the problem of hunger and nutrition, access to health care, among others, also follow this same line of reasoning in which certain individuals tend to have asymmetrical advantages over others even if they are in the same position and carrying out the same activity.

Thus, briefly, VNAE provides a mathematical model to explain how strategic agents can use structural characteristics to transform a stochastic environment into a predictable dynamic, sustaining long-term asymmetric advantages as well as shaping strategic equilibria, including in complex social systems.

3.6.6.1. VNAE Applied to the Battle of the Sexes

Just like the classic version of the game, let's consider that a couple wants to decide between going to two events: Opera (ρ) and Football (τ). The woman prefers to go to the opera, while the man prefers soccer, but they both value being together more than going alone to the event of their choice.

Traditionally, the game features two pure Nash equilibria (ρ, ρ) and (τ, τ) and a mixed equilibrium where players can randomize their choices. However, with the introduction of VNAE, we consider that the woman has a predictable advantage factor fv(Xt), which is interpreted as a social bias, a historical decision pattern and/or a psychological inclination, for example, which means that even when faced with apparently equal decision scenarios, the woman may still have some tendency, a slight advantage in her favor.

In this sense, as a slightly exaggerated hypothetical example, we can also infer that if fv(Xt) is large enough, the equilibrium in which the woman manages to go to the opera becomes the only sustainable one in the long term, characterizing an Victoria-Nash asymmetric equilibrium in which one player maintains a continued strategic advantage by exploiting predictable patterns in social interactions.

3.6.6.2. VNAE Applied to Geopolitical Scenarios

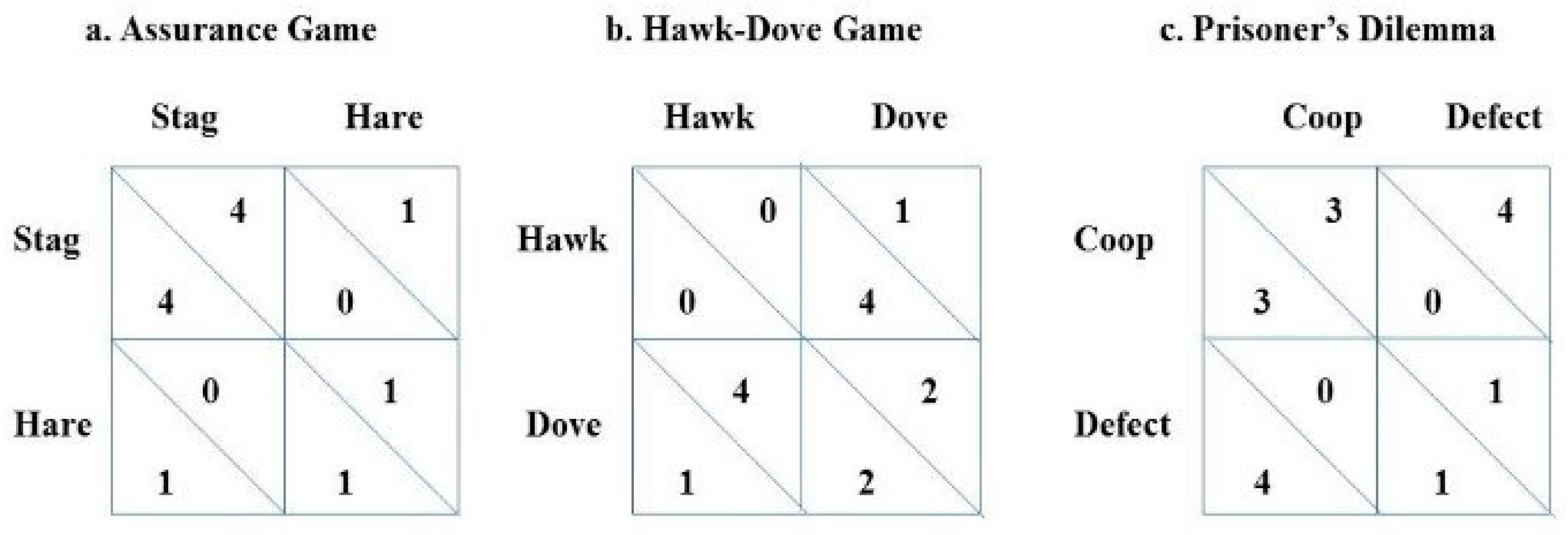

Let's consider a strategic game between Nation A and Nation B in which both compete for geopolitical influence. It is known that Nation A has structural advantages such as greater industrialization, development of new technologies, global media influence, military dominance and dominance over international institutions, for example. On the other hand, Nation B, despite also being competitive in the open-market, has fewer resources but still tries to maximize its interests. Both can opt for two main strategies Cooperation (C) or Conflict (W).

When we consider the effect of Nation A's superior industrialization, global media influence and military power, we can see that it generates a predictable structural advantage in any conflict scenario with Nation B. This factor is represented by the Predictable Random Component fv(Xt), which increases Nation A's payoffs whenever there is competition or confrontation. Below is a table containing the payoff matrix according to the VNAE:

Table 16.

Payoff matrix between two nations according to the Victoria-Nash Asymmetric Equilibrium.

Table 16.

Payoff matrix between two nations according to the Victoria-Nash Asymmetric Equilibrium.

| |

Nation B: C |

Nation B: W |

| Nation A: C |

(3, 3) |

(1, 4) |

| Nation A: W |

(4 + fv(Xt), 1) |

(2 + fv(Xt), 2) |

We can conclude that whenever Nation A opts for W (conflict), its payoff is increased by fv(Xt), as its structural superiority ensures that it loses less and gains more in rivalry scenarios. Consequently, this alters the balance of the game, making the equilibrium asymmetrical and favoring more aggressive strategies on the part of Nation A, which can sustain a dominant stance without suffering proportional losses.

Furthermore, for Nation B, this leads to a lock-in effect, where cooperation (C, C) becomes the only sustainable option in the long term, since any attempt to challenge Nation A's hegemony could lead to disproportionate results. In this way, in the field of international relations, the VNAE can explain how a dominant power can maintain a strong influence on the geopolitical scene even in the face of uncertainty and explicit rivalry.

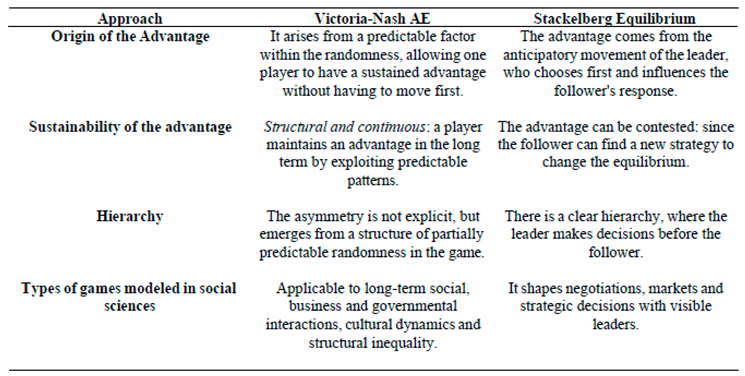

3.6.7. Differences Between Victoria-Nash Asymmetric Equilibrium (VNAE) and Stackelberg Equilibrium

The discussion in the previous section about possible applications of the VNAE within the field of social sciences inevitably leads us to ask about the main differences between the equilibrium proposed in this study and the well-established one called the Stackelberg Equilibrium, above all due to the fact that both deal with asymmetry within a game.

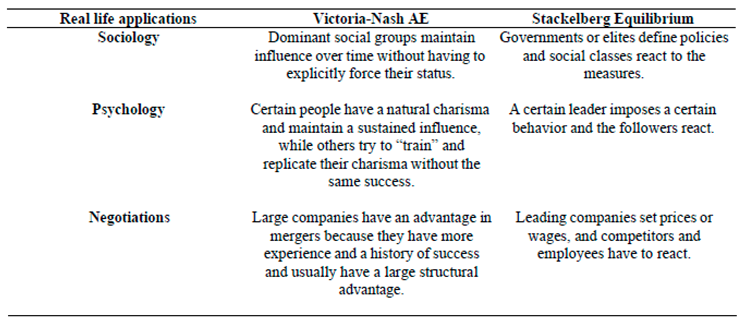

Below, through

Table 17, we will see some of the main differences between the two theories:

Table 17.

Differences between Victoria-Nash Asymmetric Equilibrium (VNAE) and Stackelberg Equilibrium.

Table 17.

Differences between Victoria-Nash Asymmetric Equilibrium (VNAE) and Stackelberg Equilibrium.

As we can see from

Table 17, both have asymmetry as a central focus and one of the players has an advantage over the other, but with different approaches to the origin of the advantage and hierarchy, for example. Next, we'll look at some of the expected practical applications for VNAE and those that usually occur with Stackelberg Equilibrium within the field of social sciences:

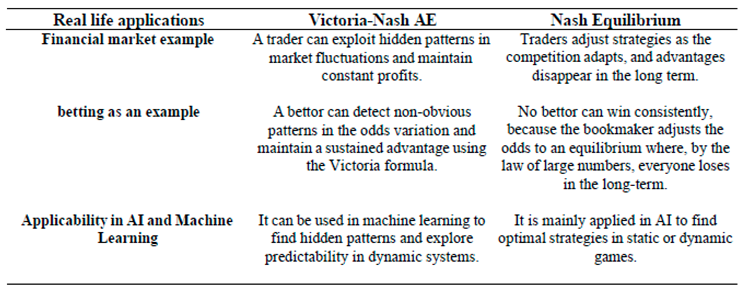

Table 18.

Some real-life applications of Victoria-Nash Asymmetric Equilibrium and Stackelberg Equilibrium.

Table 18.

Some real-life applications of Victoria-Nash Asymmetric Equilibrium and Stackelberg Equilibrium.

3.6.8. Differences Between Victoria-Nash Asymmetric Equilibrium (VNAE) and Bayesian Equilibrium

The Victoria-Nash Asymmetric Equilibrium (VNAE) and the Bayesian Equilibrium differ fundamentally in the way they treat uncertainty and the strategic structure of the players. In Bayesian Equilibrium, agents make rational decisions based on subjective beliefs about the state of the game and the types of opponents, updating these beliefs as new information is observed, using the Bayesian update rule. This equilibrium assumes that, as the game evolves, players adjust their strategies until none of them can unilaterally improve their expected outcome, leading to a state of informationally efficient equilibrium.

In contrast, VNAE proposes that, in stochastic games, part of the randomness may contain structurable patterns that, added to other additional actions such as mathematical or physical operations as well as any other ‘cognitive’ action, an agent can exploit systematically. This implies that a player can maintain a sustained strategic advantage over time, creating an asymmetric equilibrium, where at first, given scenario I, the optimization of opponents is not enough to completely neutralize this advantage.

While Bayesian equilibrium assumes that uncertainty is inherent and ineliminable, VNAE suggests that certain agents can structurally reduce uncertainty, shifting the equilibrium to a state that is persistently favorable to a specific player. Thus, we can begin to see the existence of purely Bayesian players and purely victorian players (those who use the function η(Xt) in their decision-making).

The concept behind the Predictable Random Component function, given the experience I have had in the course of this study as well as drawing on the vast literature of colleagues over time, does not seem absurd to me, but increasingly clear and intelligible as well as realistic within the context of Decision Theory and Game Theory.

As can be seen in the section “Is it Possible to Beat the House?” many scientists and people driven by curiosity in the field of mathematics and statistics have exploited patterns normally expected by the law of large numbers and other types of convergence in probability to beat the house. In fact, in this very study, through the Victoria formula, the PRC (Predictable Random Component) proved to be a more strongly applicable example for positive mathematical expectation and systematic financial gains in the long run.

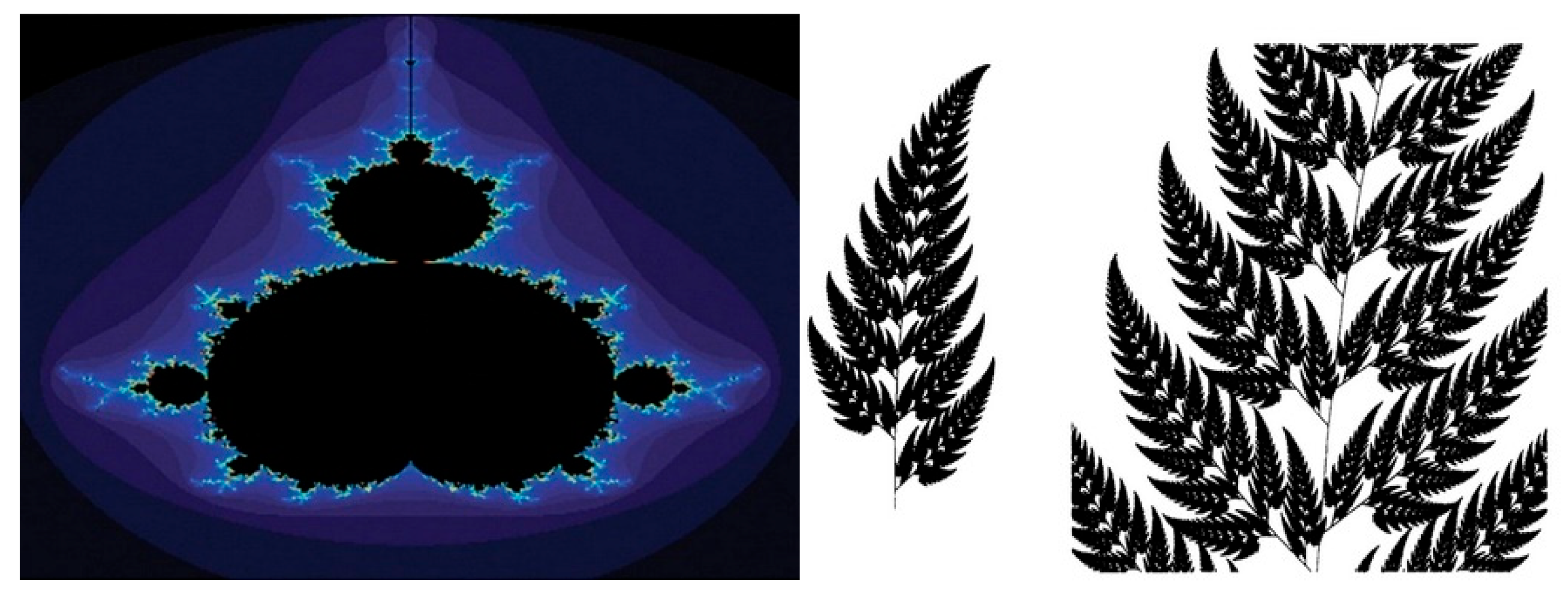

In the case of this study, through Victoria, we note that the predictable random component (PRC) is understood as convergence in probability, however, with the eventual advances in scientific and statistical thinking as well as new disruptive technologies such as those coming from quantum mechanics, paradoxically, they can also lead us to deepen and better understand the true nature of randomness given a probability distribution and why certain numbers/events occur in t period of time and n place. As Poincaré (1908) and many other colleagues throughout history have pointed out, as human beings we consider as random everything in which we are unaware and/or which cannot be fully quantified. But this scenario could be better explored, especially with new generations of academics.

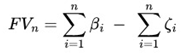

In fact, we can observe a connection between the optimal strategy and the η(Xt) function in which we could perhaps also classify it as simply part of the optimal strategy found by a player. However, since we are taking as examples the very nature of randomness given a probability distribution, in the case of this study the uniform distribution has been used, something inherently immutable, perhaps we should propose a reflection in the sense of extending η(Xt) or fv(Xt) as a basic function in relation to the others that normally constitute a basic game in this field of study. Below, with the table x, we will see more differences between these two theorizations.

Table 19.

Differences between Asymmetric Victoria-Nash Equilibrium and Bayesian Equilibrium.

Table 19.

Differences between Asymmetric Victoria-Nash Equilibrium and Bayesian Equilibrium.

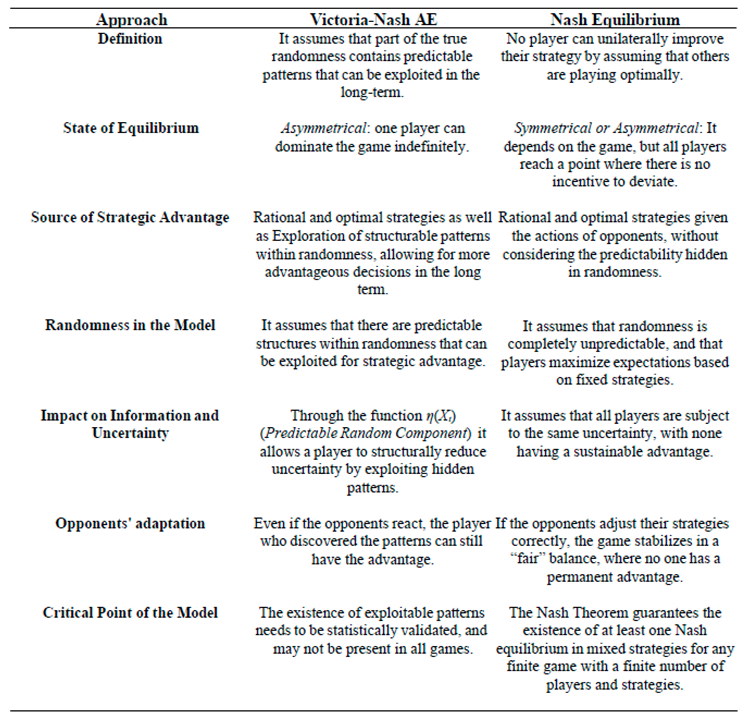

3.6.9. Differences Between Victoria-Nash Asymmetric Equilibrium and Nash Equilibrium

In this part of the study, we will analyze some fundamental differences between the Victoria-Nash Asymmetric Equilibrium and Nash Equilibrium Differences, considering different approaches from their definition to the critical point of these theorizations.

Table 20.

Differences between Asymmetric Victoria-Nash Equilibrium and Nash Equilibrium.

Table 20.

Differences between Asymmetric Victoria-Nash Equilibrium and Nash Equilibrium.

Below, also for better visualization purposes, a table is also used to demonstrate some examples of possible real-life situations involving these two types of equilibrium.

Table 21.

Differences between Asymmetric Victoria-Nash Equilibrium and Nash Equilibrium with real life applications examples.

Table 21.

Differences between Asymmetric Victoria-Nash Equilibrium and Nash Equilibrium with real life applications examples.

As we can see from the tables in this section, the Victoria-Nash Asymmetrical Equilibrium (VNAE) differs from the Nash Equilibrium by allowing a player to sustain a continuous strategic advantage by exploiting predictable patterns (i.e. convergences in probabilities) within the randomness of the game.

While the Nash Equilibrium assumes that all players adopt optimal strategies, leading to a point where no one can unilaterally improve their position, the VNAE suggests that certain players can find predictable structures in uncertainty, which allows them to make more advantageous decisions in the long run. This ability to exploit hidden regularities makes the equilibrium asymmetrical, since one agent can maintain a dominant position even if the others adjust (according to scenario I).

Unlike the traditional Nash model, which assumes a static scenario where strategies converge to a point of mutual equilibrium, the VNAE proposes a dynamic equilibrium, where a player can continue to make structural gains due to the continuous exploitation of patterns in true randomness and/or with actions not completely mitigated by the other players. This challenges the idea that, in the long term, all competitive advantages disappear as players adjust their strategies.

If Sportsbooks were to adopt extreme restrictions such as limiting the amounts wagered, limiting bets on certain sports markets and even banning victorian players, the VNAE equilibrium would still remain unchanged, since Sportsbooks are not only adjusting their strategies within the game, but changing the external rules of the market, which also does not characterize a Nash Equilibrium, since the original game is modified to prevent certain players from fully participating.

Thus, VNAE redefines the notion of equilibrium in Game Theory by including the possibility of persistent advantages for certain players, which has direct implications for financial markets, cybersecurity, biological sciences, artificial intelligence and risk modeling in sports betting, for example.

3.6.10. Sportsbooks' Possible Defensive Reactions to the Victorian Players

As has been seen throughout this study, in the exchange version, regardless of which players win or lose, the house always takes its share of the profit. However, in a scenario where players against the house are considered to be relatively significant in the market, sportsbooks can probably resort to some defensive measures, such as:

Changing the way the odds are calculated by applying a higher vigorish to compensate for any losses;

Offer less favorable odds than they normally do;

Limiting or banning accounts that use advanced statistical strategies.

Implementing new machine learning systems to detect victorian betting patterns.

As we can see, there are indeed some possibilities for sportsbooks to minimize this scenario of an asymmetrical advantage for certain groups of bettors. However, they will probably have to carry out a rigorous study to assess the costs and benefits of adopting measures such as increasing the vigorish as well as offering odds that are less realistic than those that could occur in sporting events. As Bontis (1996) points out and Isnard (2021) corroborates, organizations, in this case sportsbooks, need not only to have large volumes of data, but also good knowledge management, intellectual capital and available technology.

This defensive practice, if overdone, can make the task of “retaining” customers even more difficult, as well as attracting more when you have odds that may reflect reality very poorly and/or when you have a popularized slogan that the bookmaker bans bettors from certain markets or even from the platform. Such measures can discourage current customers as well as driving away potential new ones. The question that remains is to deliberately seek a point of equilibrium in which the bookmaker can still maintain its activities and, at the same time, not make players feel that they have been “probabilistically robbed”.

Sportsbooks, on the other hand, in order to expand into other territories and regulate the market, could delve into the internationalization processes of firms that address the importance of relationship and knowledge management processes, in addition to knowledge of the market itself, as pointed out by Barbosa et al (2014). Furthermore, Sportbooks may be arguing that statistics can also beat them, as presented in the literature discussed above, as well as in this study.

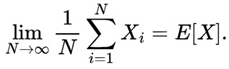

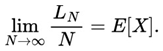

ϵ > 0, and we write Xn

ϵ > 0, and we write Xn Y.

Y.

is the expected utility for player i when choosing action ai, given that the other players choose their actions a-i according to strategies σ-i, and that the probability distribution π-i reflects player i's beliefs about the types of the other players.

is the expected utility for player i when choosing action ai, given that the other players choose their actions a-i according to strategies σ-i, and that the probability distribution π-i reflects player i's beliefs about the types of the other players.

distributed (i.i.d.), as each IB follows the same probabilistic model.

distributed (i.i.d.), as each IB follows the same probabilistic model.

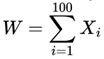

shows a linear trend with N, where:

shows a linear trend with N, where:

and E[X] > 0, we conclude that WN > 0 with high probability for sufficiently large N.

and E[X] > 0, we conclude that WN > 0 with high probability for sufficiently large N.

strategy that ensures that in the long term his expected payoff will be positive.

strategy that ensures that in the long term his expected payoff will be positive. strategy guarantees that [πi ] > 0, regardless of the behavior of the other players.

strategy guarantees that [πi ] > 0, regardless of the behavior of the other players.

is the utility function of each player;

is the utility function of each player; such that:

such that:

such that:

such that: that allows continuous advantage, shifting the equilibrium to an asymmetric state.

that allows continuous advantage, shifting the equilibrium to an asymmetric state. is the payoff function for each player i.

is the payoff function for each player i.

such that

such that

n, and convex, since it allows mixed strategies.

n, and convex, since it allows mixed strategies. such that

such that  guaranteeing the existence of an asymmetric Victoria-Nash equilibrium where a player can exploit predictable patterns of randomness in a sustainable way.

guaranteeing the existence of an asymmetric Victoria-Nash equilibrium where a player can exploit predictable patterns of randomness in a sustainable way.

such that:

such that:

a state where:

a state where:

constitutes a Victoria-Nash equilibrium (VNAE)

constitutes a Victoria-Nash equilibrium (VNAE)

) : player i's expected payoff when choosing the strategy

) : player i's expected payoff when choosing the strategy  .

. : set of information available to player i at the time of the decision, which influences his/her strategic choice.

: set of information available to player i at the time of the decision, which influences his/her strategic choice.