Submitted:

10 June 2025

Posted:

12 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Maintenance of the JP7 Cell Line

2.2. Establishment, Identification, and Selection of JP7pSer+ and JP7pSer- Cell Lines

2.3. Evaluation of the Effect of Serpina-1 Gene Transfection on Cell Lines in Culture

2.3.1. Cell Proliferation

2.3.2. Gene Expression of Serpina-1, Furin, IL-6 and NSD2

2.3.3. Membrane Expression of the IGF-1 Receptor

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Establishment, Identification, and Selection of JP7pSer+ and JP7pSer- Cell Lines

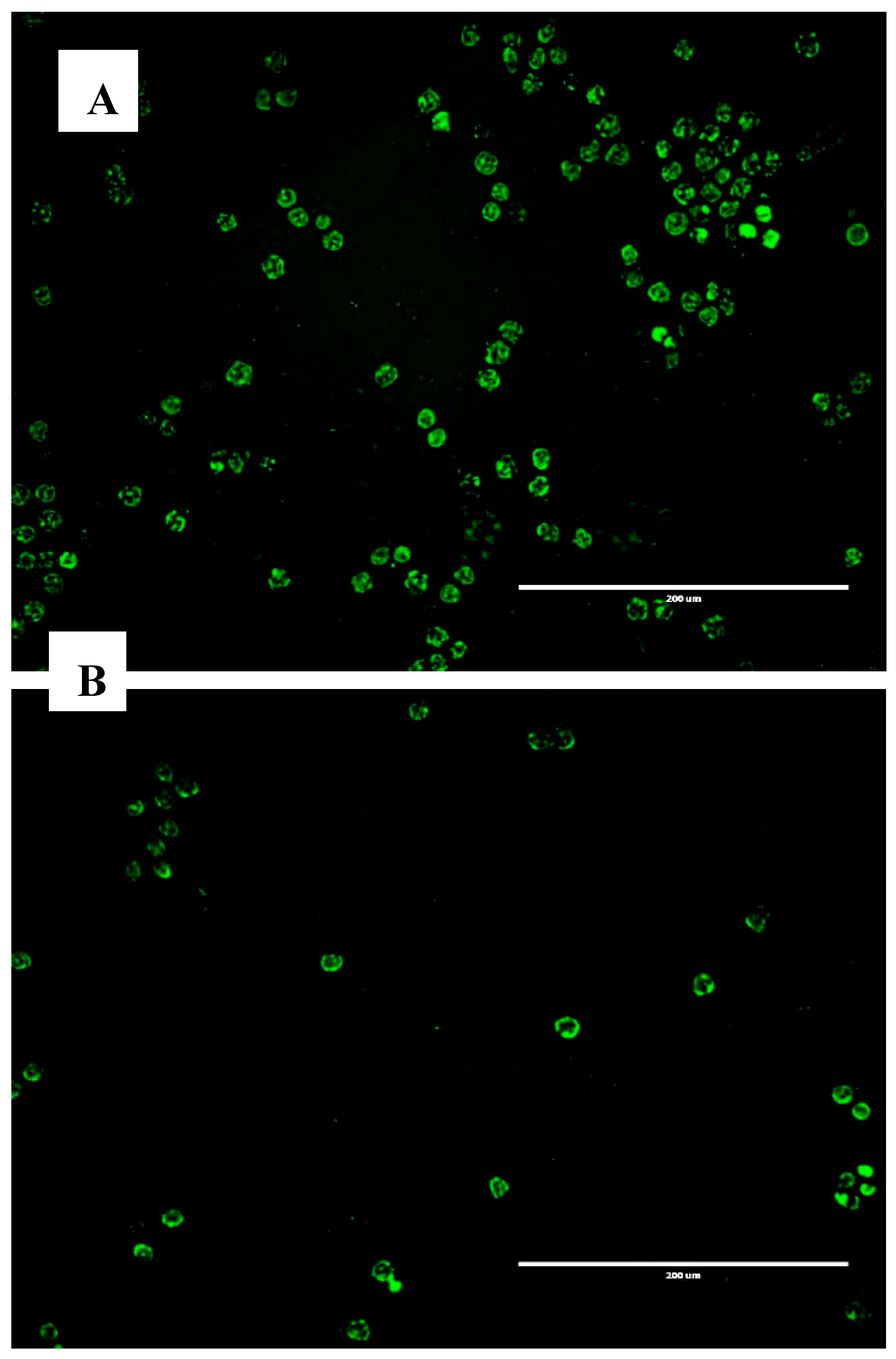

3.1.1. Microscopy

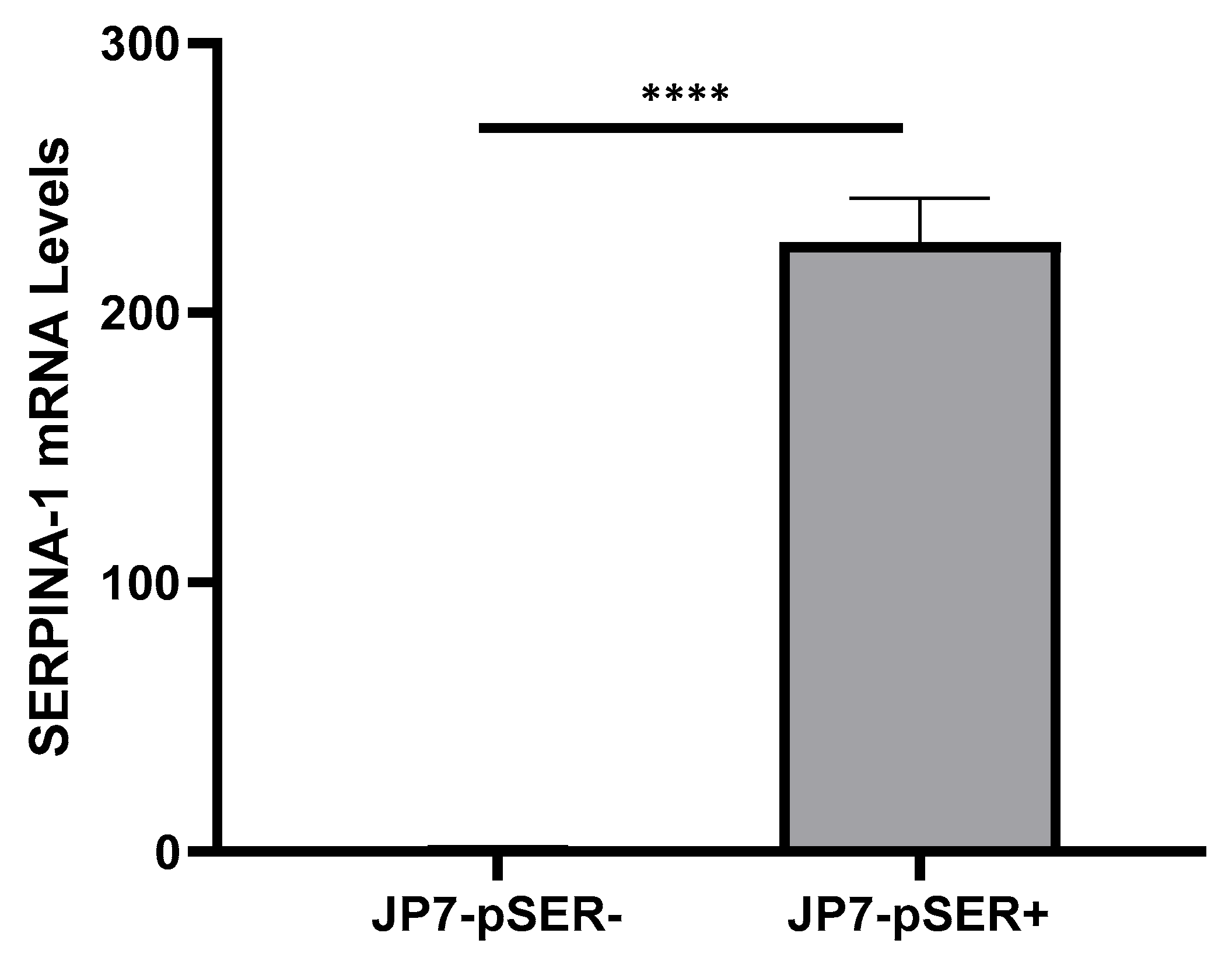

3.1.2. qRT-PCR

3.2. Evaluation of the Effect of SERPINA1 Gene Transfection on Cultured Cell Lines

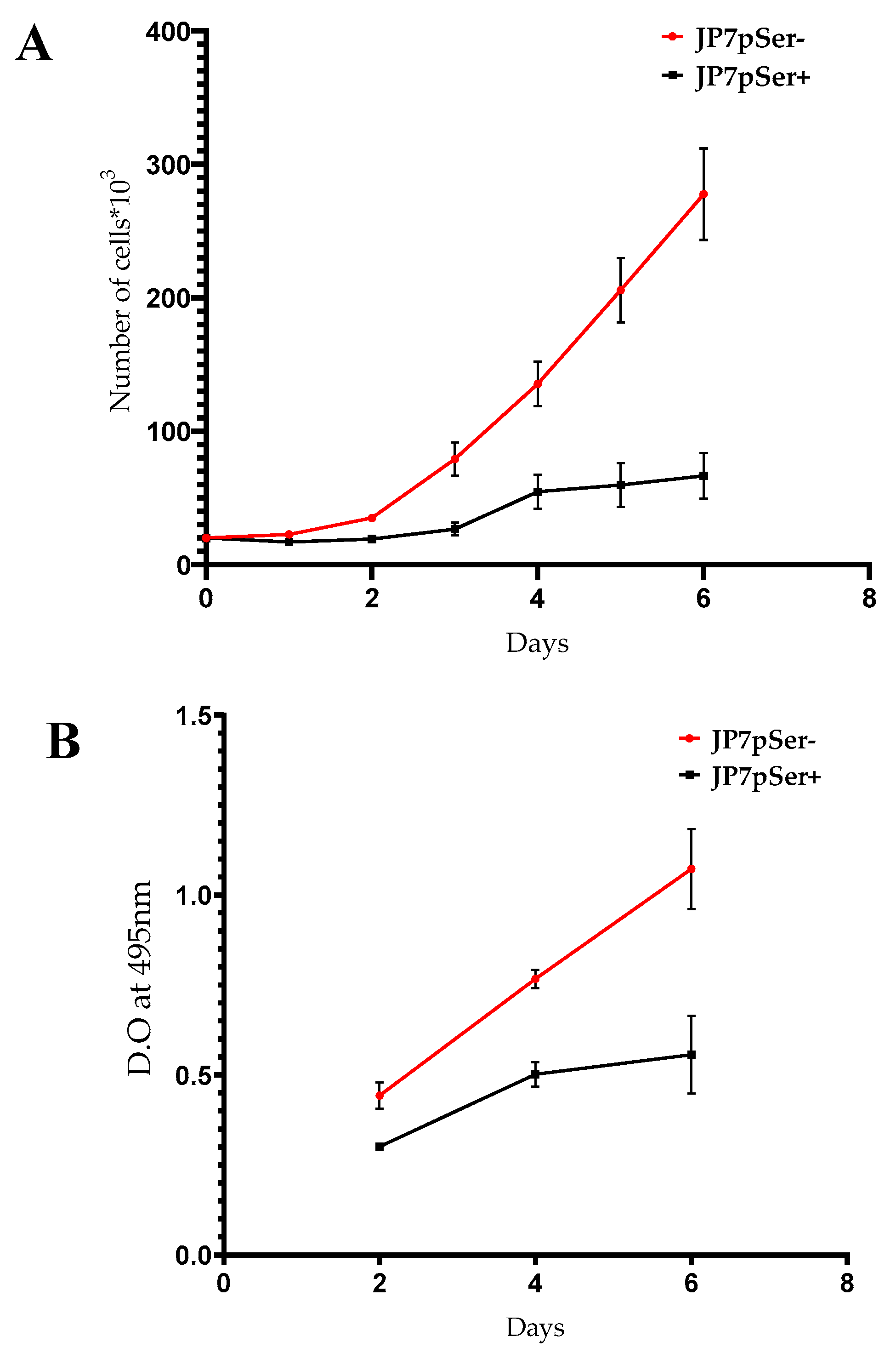

3.2.1. Cell Proliferation

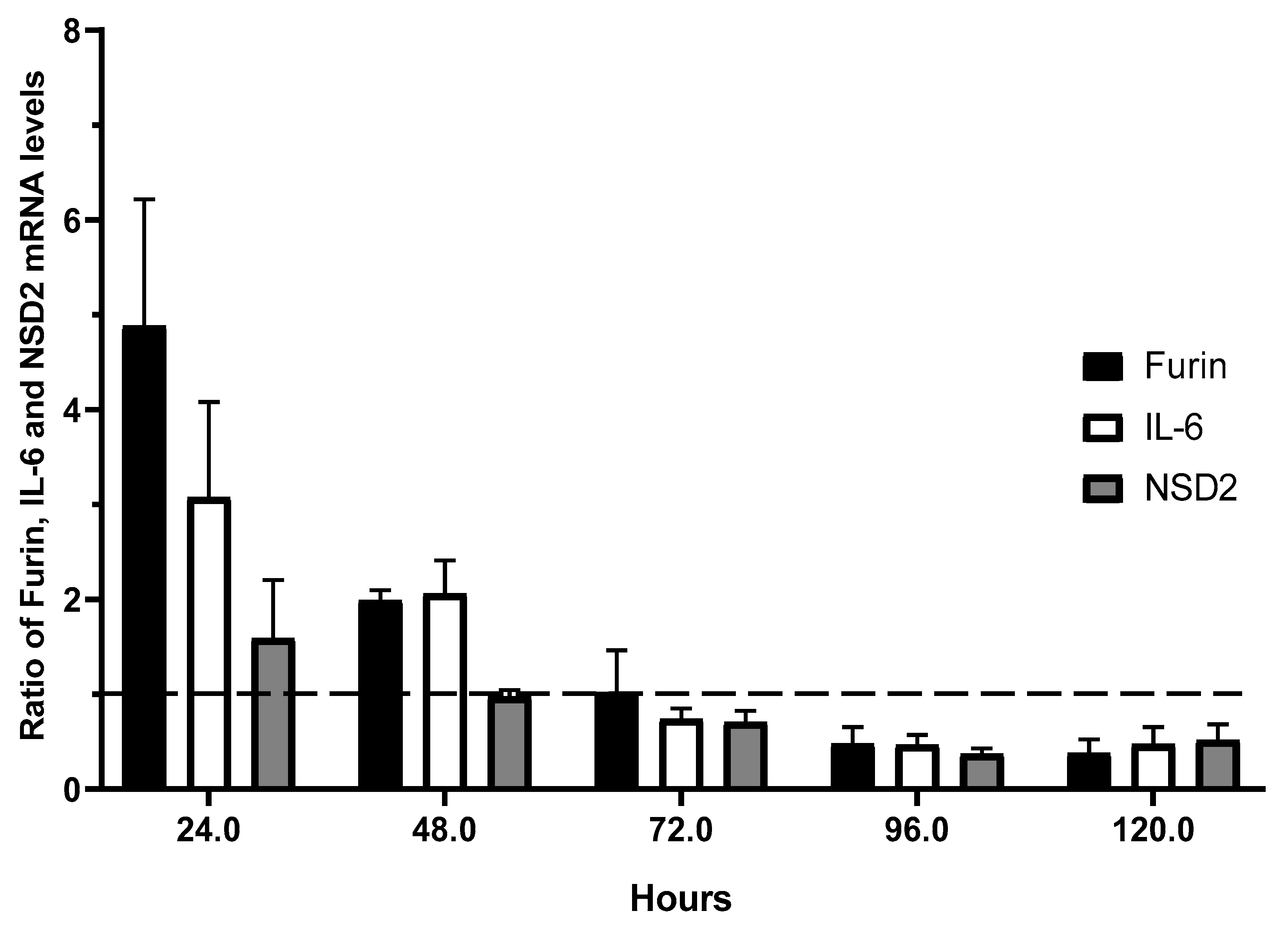

3.2.2. Kinetics of Gene Expression for Furin, IL-6, and NSD2

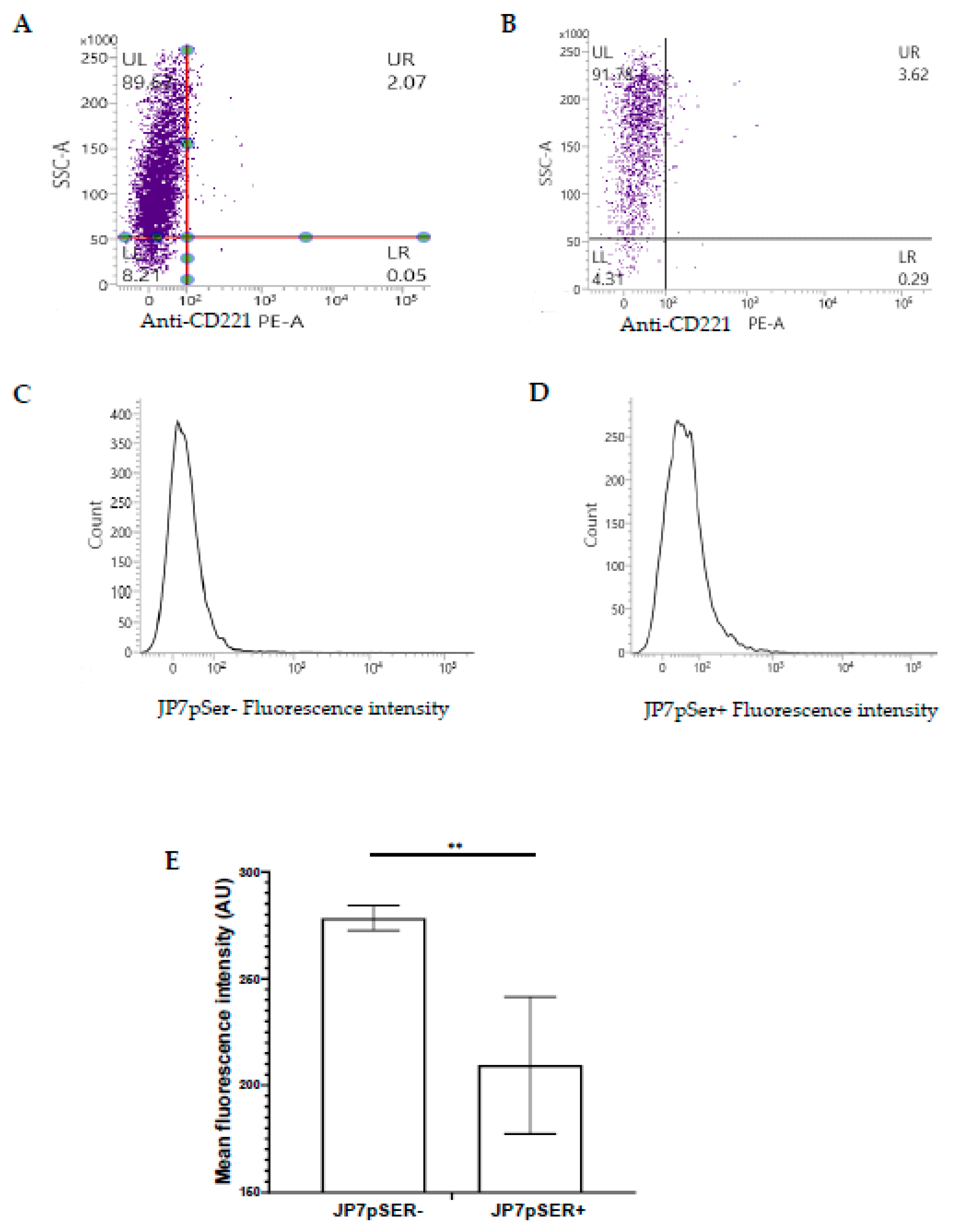

3.2.3. Membrane Expression of the IGF-1 Receptor (IGF-1R, CD221)

4. Discussion

5. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| IGF-1 | Insulin-like growth factor-1 |

| PI3K | Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase |

| AKT | Protein kinase B |

| mTOR | Mammalian target of rapamycin |

| MAPK | Mitogen-activated protein kinase |

| ERK | Extracellular signal-regulated kinases |

| JAK | Janus kinases |

| STAT | Signal transducer and activator of transcription proteins |

| IGF-1R | Insulin-like growth factor-1 receptor |

| IL-6 | Interleukin 6 |

| TNF-α | Tumor necrosis factor |

| NSD2 | Probable histone-lysine N-methyltransferase |

| EBV | Epstein-Barr virus |

| STAT3 | Signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 |

| Lys | Lysine |

| Arg | Arginine |

| TGF-β1 | Transforming growth factor beta 1 |

| PC | Proprotein convertase |

| A1AT | Alpha-1 antitrypsin |

| Alpha- 1PDX | alpha-1 antitrypsin Portland variant |

| PACE4 | Proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 6 |

| PC7 | Proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 7 |

| CMV | Cytomegalovirus |

| GFP | Green fluorescent protein |

| mRNA | Messenger ribonucleic acid |

| qRT-PCR CI mRNA |

Quantitative Reverse Transcription – Poly Chain Réaction confidence interval messenger ribonucleic acid |

References

- M. C. Casotti et al., “Integrating frontiers: a holistic, quantum and evolutionary approach to conquering cancer through systems biology and multidisciplinary synergy,” Frontiers in Oncology, vol. 14. Frontiers Media, Aug. 19, 2024. [CrossRef]

- A. D. Gheorghe et al., “Epigenetic Symphony in Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma: Orchestrating the Tumor Microenvironment,” Biomedicines, vol. 13, no. 4, p. 853, Apr. 2025. [CrossRef]

- T. C. Dakal et al., “Oncogenes and tumor suppressor genes: functions and roles in cancers,” MedComm, vol. 5, no. 6. Wiley, May 31, 2024. [CrossRef]

- S. Wang et al., “Cell death pathways: molecular mechanisms and therapeutic targets for cancer,” MedComm, vol. 5, no. 9. Wiley, Sep. 01, 2024. [CrossRef]

- S. Yuan et al., “Profiling signaling mediators for cell-cell interactions and communications with microfluidics-based single-cell analysis tools,” iScience, vol. 28, no. 1. Cell Press, p. 111663, Dec. 20, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Y. Peng and J. Tan, “The Relationship between IGF Pathway and Acquired Resistance to Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitors in Cancer Therapy,” Frontiers in Bioscience-Landmark, vol. 28, no. 8. IMR Press, Aug. 11, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Q. Luo, R. Du, W. Liu, G. Huang, Z. Dong, and X. Li, “PI3K/Akt/mTOR Signaling Pathway: Role in Esophageal Squamous Cell Carcinoma, Regulatory Mechanisms and Opportunities for Targeted Therapy,” Frontiers in Oncology, vol. 12. Frontiers Media, Mar. 22, 2022. [CrossRef]

- D. Fu, Z. Hu, X. Xu, X. Dai, and Z. Liu, “Key signal transduction pathways and crosstalk in cancer: Biological and therapeutic opportunities,” Translational Oncology, vol. 26, p. 101510, Sep. 2022. [CrossRef]

- B. Huang, X. Lang, and X. Li, “The role of IL-6/JAK2/STAT3 signaling pathway in cancers,” Frontiers in Oncology, vol. 12. Frontiers Media, Dec. 16, 2022. [CrossRef]

- A. Derakhshani et al., “An Overview of the Oncogenic Signaling Pathways in Different Types of Cancers,” Mar. 2020. [CrossRef]

- M. Aprile, S. Cataldi, C. Perfetto, A. Federico, A. Ciccodicola, and V. Costa, “Targeting metabolism by B-raf inhibitors and diclofenac restrains the viability of BRAF-mutated thyroid carcinomas with Hif-1α-mediated glycolytic phenotype,” British Journal of Cancer, vol. 129, no. 2, p. 249, May 2023. [CrossRef]

- F. Rascio et al., “The Pathogenic Role of PI3K/AKT Pathway in Cancer Onset and Drug Resistance: An Updated Review,” Cancers, vol. 13, no. 16. Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute, p. 3949, Aug. 05, 2021. [CrossRef]

- L. Wang, T. Yi, M. Kortylewski, D. M. Pardoll, D. Zeng, and H. Yu, “IL-17 can promote tumor growth through an IL-6–Stat3 signaling pathway,” The Journal of Experimental Medicine, vol. 206, no. 7, p. 1457, Jun. 2009. [CrossRef]

- V. Krajka-Kuźniak, M. Belka, and K. Papierska, “Targeting STAT3 and NF-κB Signaling Pathways in Cancer Prevention and Treatment: The Role of Chalcones,” Cancers, vol. 16, no. 6. Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute, p. 1092, Mar. 08, 2024. [CrossRef]

- J. Liu, X.-F. Geng, J. Hou, and G. Wu, “New insights into M1/M2 macrophages: key modulators in cancer progression,” Cancer Cell International, vol. 21, no. 1. BioMed Central, Jul. 21, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Tanaka T, Narazaki M, Kishimoto T. Interleukin (IL-6) Immunotherapy. Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Biology 2017;10. [CrossRef]

- Harmer D, Falank C, Reagan MR. Interleukin-6 Interweaves the Bone Marrow Microenvironment, Bone Loss, and Multiple Myeloma. Frontiers in Endocrinology 2019;9. [CrossRef]

- Song D, Lan J, Chen Y, Liu A, Wu Q, Zhao C, et al. NSD2 promotes tumor angiogenesis through methylating and activating STAT3 protein. Oncogene 2021;40:2952. [CrossRef]

- Li W, Tian W, Yuan G, Deng P, Sengupta D, Cheng Z, et al. Molecular basis of nucleosomal H3K36 methylation by NSD methyltransferases. Nature 2020;590:498. [CrossRef]

- Liu Q, Wang M. Histone lysine methyltransferases as anti-cancer targets for drug discovery. Acta Pharmacologica Sinica 2016;37. [CrossRef]

- Gao B, Liu X, Li Z, Zhao L, Pan Y. Overexpression of EZH2/NSD2 Histone Methyltransferase Axis Predicts Poor Prognosis and Accelerates Tumor Progression in Triple-Negative Breast Cancer. Frontiers in Oncology 2021;10. [CrossRef]

- Mehranzadeh E, Crende O, Badiola I, García-Gallastegui P. What Are the Roles of Proprotein Convertases in the Immune Escape of Tumors? Biomedicines 2022;10:3292. [CrossRef]

- Pratheeshkumar P, Siraj AK, Padmaja D, Parvathareddy SK, Diaz R, Thangavel S, et al. Overexpression of the pro-protein convertase furin predicts prognosis and promotes papillary thyroid carcinoma progression and metastasis through RAF/MEK signaling. Molecular Oncology 2023;17:1324. [CrossRef]

- Cevenini A, Orrù S, Mancini A, Alfieri A, Buono P, Imperlini E. Molecular Signatures of the Insulin-Like Growth Factor 1-Mediated Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transition in Breast, Lung and Gastric Cancers. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2018;19:2411. [CrossRef]

- Ianza A, Sirico M, Bernocchi O, Generali D. Role of the IGF-1 Axis in Overcoming Resistance in Breast Cancer. Frontiers in Cell and Developmental Biology 2021;9. [CrossRef]

- Zhou B, Gao S. Pan-Cancer Analysis of FURIN as a Potential Prognostic and Immunological Biomarker. Frontiers in Molecular Biosciences 2021;8. [CrossRef]

- Fu J, Bassi DE, Zhang J, Li T, Nicolas É, Klein-Szanto AJ. Transgenic Overexpression of the Proprotein Convertase Furin Enhances Skin Tumor Growth. Neoplasia 2012;14:271. [CrossRef]

- Bassi D, Cicco RL de, Mahloogi H, Zucker S, Thomas G, Klein-Szanto AJ. Furin inhibition results in absent or decreased invasiveness and tumorigenicity of human cancer cells. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2001;98:10326. [CrossRef]

- Seong GJ, Hong S, Jung S, Lee JJ, Lim E, Kim SJ, et al. TGF-beta-induced interleukin-6 participates in transdifferentiation of human Tenon’s fibroblasts to myofibroblasts. PubMed 2009.

- Declercq J, Brouwers B, Pruniau VPEG, Stijnen P, Tuand K, Meulemans S, et al. Liver-Specific Inactivation of the Proprotein Convertase FURIN Leads to Increased Hepatocellular Carcinoma Growth. BioMed Research International 2015;2015:1. [CrossRef]

- He Z, Khatib A, Creemers JWM. Loss of Proprotein Convertase Furin in Mammary Gland Impairs proIGF1R and proIR Processing and Suppresses Tumorigenesis in Triple Negative Breast Cancer. Cancers 2020;12:2686. [CrossRef]

- Werner H, Meisel-Sharon S, Bruchim I. Oncogenic fusion proteins adopt the insulin-like growth factor signaling pathway. Molecular Cancer 2018;17. [CrossRef]

- Ercetin E, Richtmann S, Martínez-Delgado B, Gómez-Mariano G, Wrenger S, Korenbaum E, et al. Clinical Significance of SERPINA1 Gene and Its Encoded Alpha1-antitrypsin Protein in NSCLC. Cancers 2019;11:1306. [CrossRef]

- Izaguirre G, Arciniega M, Quezada A. Specific and Selective Inhibitors of Proprotein Convertases Engineered by Transferring Serpin B8 Reactive-Site and Exosite Determinants of Reactivity to the Serpin α1PDX. Biochemistry 2019;58:1679. [CrossRef]

- A. Tissent, N. Habti, F. Sadiq, N. El Amrani, N. Benchemsi, Production d'un réactif monoclonal anti-B humain pour la détection des groupes sanguins ABO,Immuno-analyse & Biologie Spécialisée,Volume 22, Issue 1, 2007, Pages 68-71,ISSN 0923-2532. [CrossRef]

- K. J. Livak and T. D. Schmittgen, “Analysis of Relative Gene Expression Data Using Real-Time Quantitative PCR and the 2−ΔΔCT Method,” Dec. 01, 2001, Elsevier BV. [CrossRef]

- A. Karadagi et al., “Exogenous alpha 1-antitrypsin down-regulates SERPINA1 expression,” PLoS ONE, vol. 12, no. 5, May 2017. [CrossRef]

- D. A. Dean, B. S. Dean, S. Müller, and L. C. Smith, “Sequence Requirements for Plasmid Nuclear Import,” Experimental Cell Research, vol. 253, no. 2, p. 713, Dec. 1999. [CrossRef]

- J. Vacik, B. S. Dean, W. E. Zimmer, and D. A. Dean, “Cell-specific nuclear import of plasmid DNA,” Gene Therapy, vol. 6, no. 6, p. 1006, Jun. 1999. [CrossRef]

- J. Y. Qin et al., “Systematic Comparison of Constitutive Promoters and the Doxycycline-Inducible Promoter,” PLoS ONE, vol. 5, no. 5, May 2010. [CrossRef]

- C. A. Stuart, R. T. Meehan, L. S. Neale, N. M. Cintrón, and R. W. Furlanetto, “Insulin-Like Growth Factor-I Binds Selectively to Human Peripheral Blood Monocytes and B-Lymphocytes*,” The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, vol. 72, no. 5, p. 1117, May 1991. [CrossRef]

- Y. Ma, W. Fan, S.-M. Rao, G. Li, Z.-Y. Bei, and S. Xu, “Effect of Furin inhibitor on lung adenocarcinoma cell growth and metastasis,” Cancer Cell International, vol. 14, no. 1, May 2014. [CrossRef]

- D. Farhat et al., “Lipoic acid decreases breast cancer cell proliferation by inhibiting IGF-1R via furin downregulation,” British Journal of Cancer, vol. 122, no. 6, p. 885, Jan. 2020. [CrossRef]

- D. Bassi, H. Mahloogi, R. L. de Cicco, and A. J. Klein-Szanto, “Increased Furin Activity Enhances the Malignant Phenotype of Human Head and Neck Cancer Cells,” American Journal Of Pathology, vol. 162, no. 2, p. 439, Feb. 2003. [CrossRef]

- T. Basu, H. Bertrand, N. Karantzelis, A. Gründer, and H. L. Pahl, “Pharmacological Inhibition of Insulin Growth Factor-1 Receptor (IGF-1R) Alone or in Combination With Ruxolitinib Shows Therapeutic Efficacy in Preclinical Myeloproliferative Neoplasm Models,” HemaSphere, vol. 5, no. 5, Apr. 2021. [CrossRef]

- J. Tsui, S. Qi, S. Perrino, M. Leibovitch, and P. Brodt, “Identification of a Resistance Mechanism to IGF-IR Targeting in Human Triple Negative MDA-MB-231 Breast Cancer Cells,” Biomolecules, vol. 11, no. 4, p. 527, Apr. 2021. [CrossRef]

- J. Chen et al., “IL-6: The Link Between Inflammation, Immunity and Breast Cancer,” Frontiers in Oncology, vol. 12. Frontiers Media, Jul. 18, 2022. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).