Submitted:

05 June 2025

Posted:

11 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

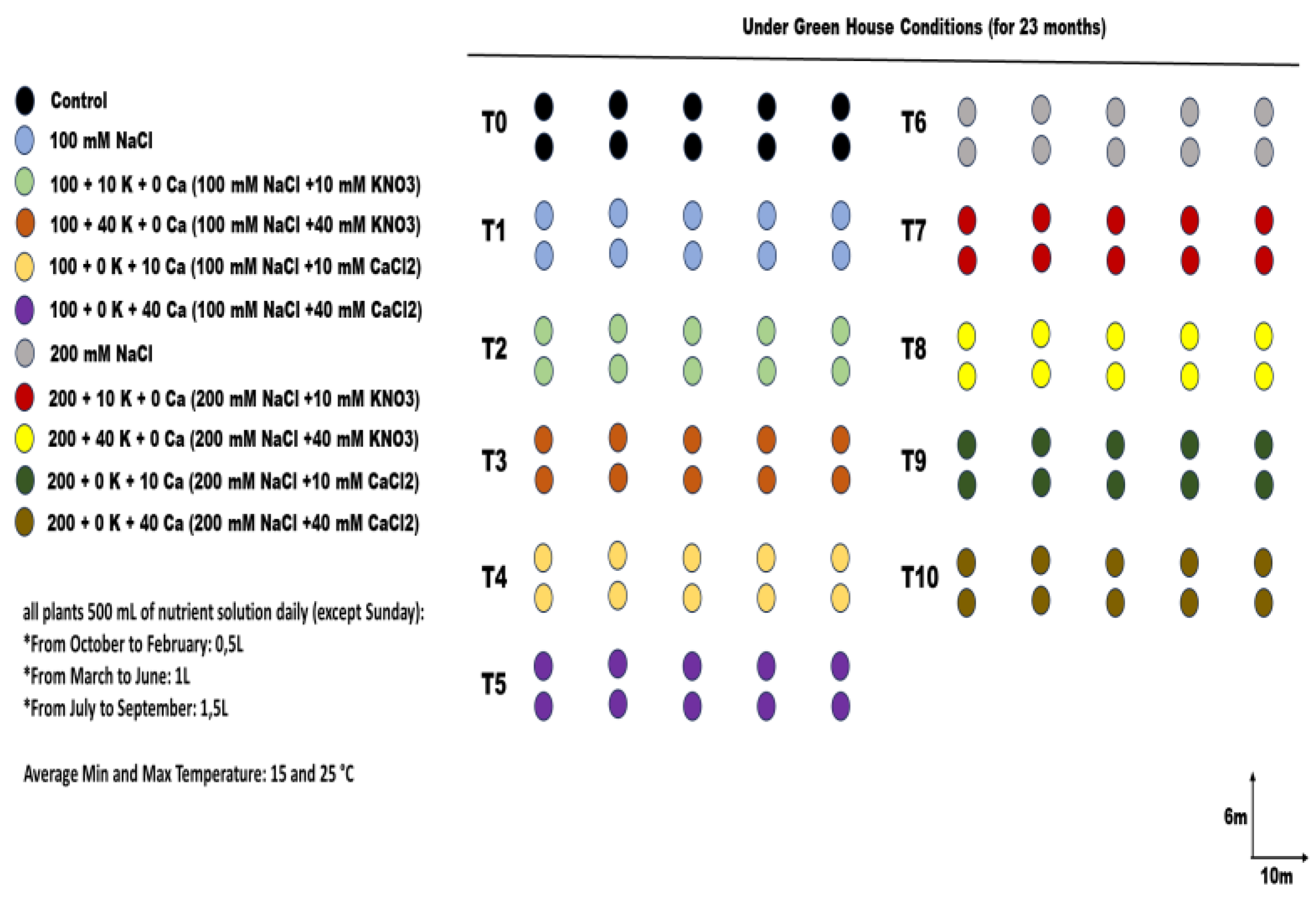

2.1. Plant Material and Experimental Design

2.2. Gas Exchange Measurements and Water Use Efficiency (WUE)

2.3. Modulated Chlorophyll Fluorescence Analyses

2.4. Photosynthetic Pigment Composition

2.5. Soluble Sugar and Proline

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

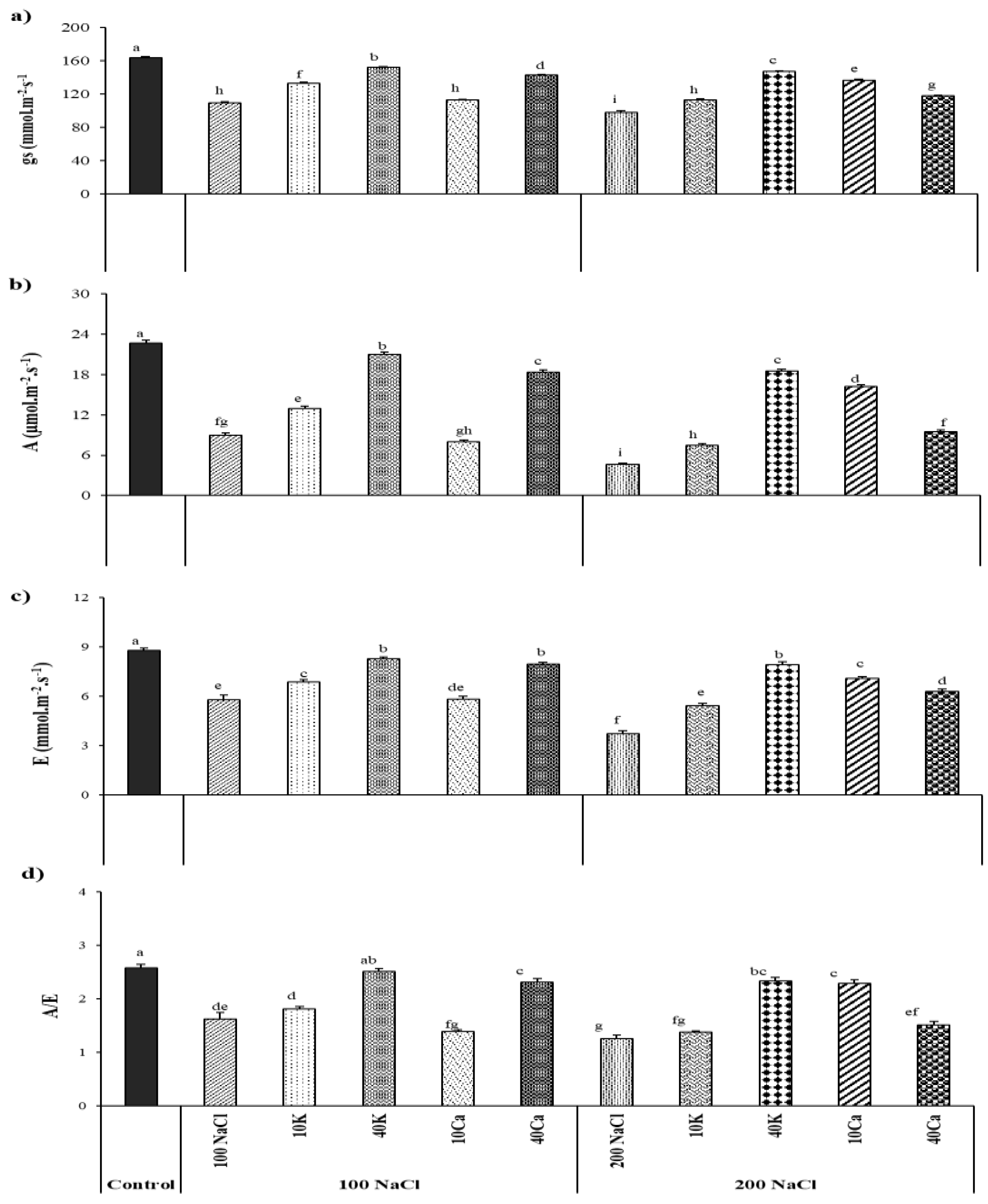

3.1. Gas, Exchange, and Water Use Efficiency

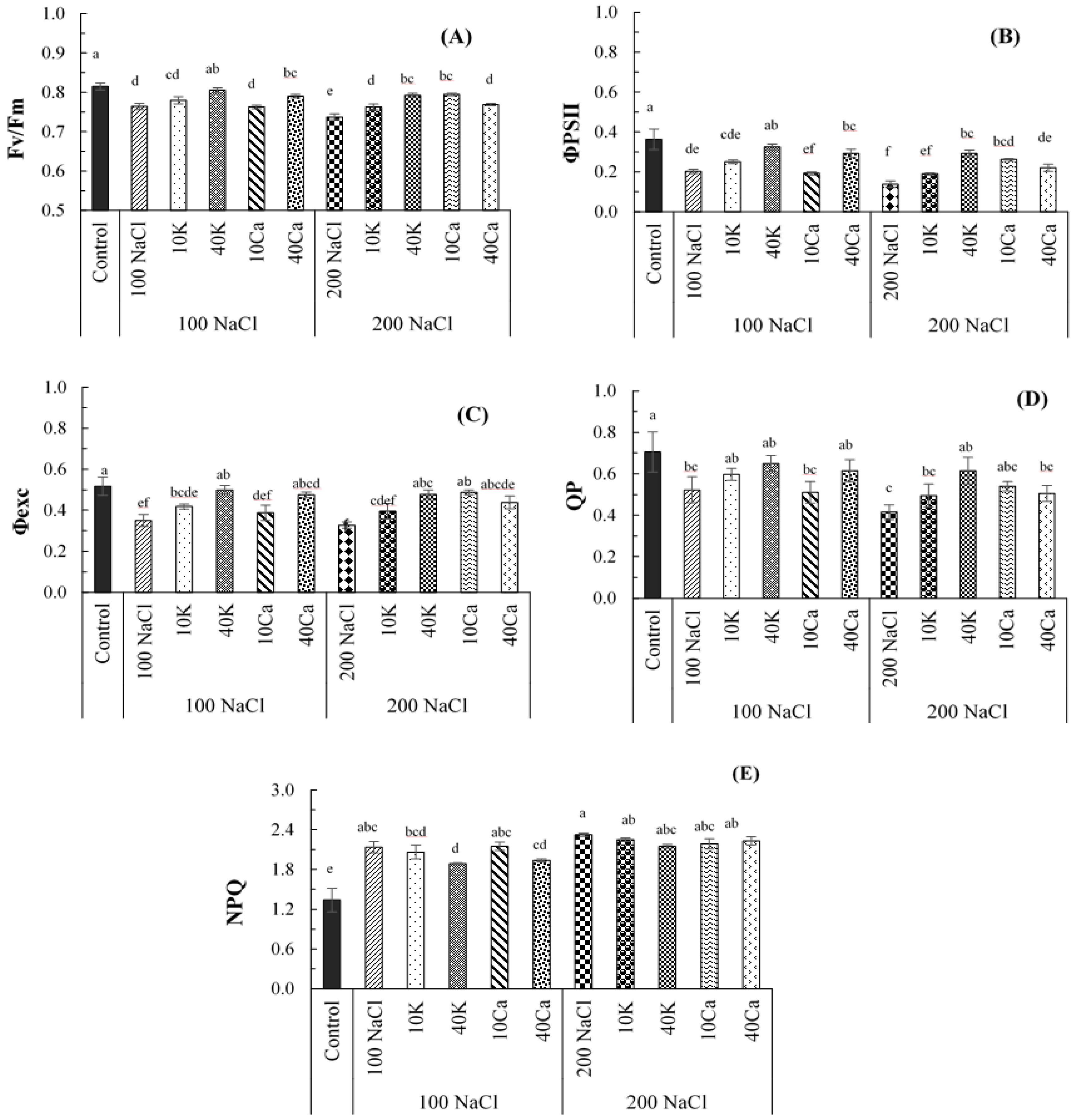

3.2. Impact on Chlorophyll Fluorescence

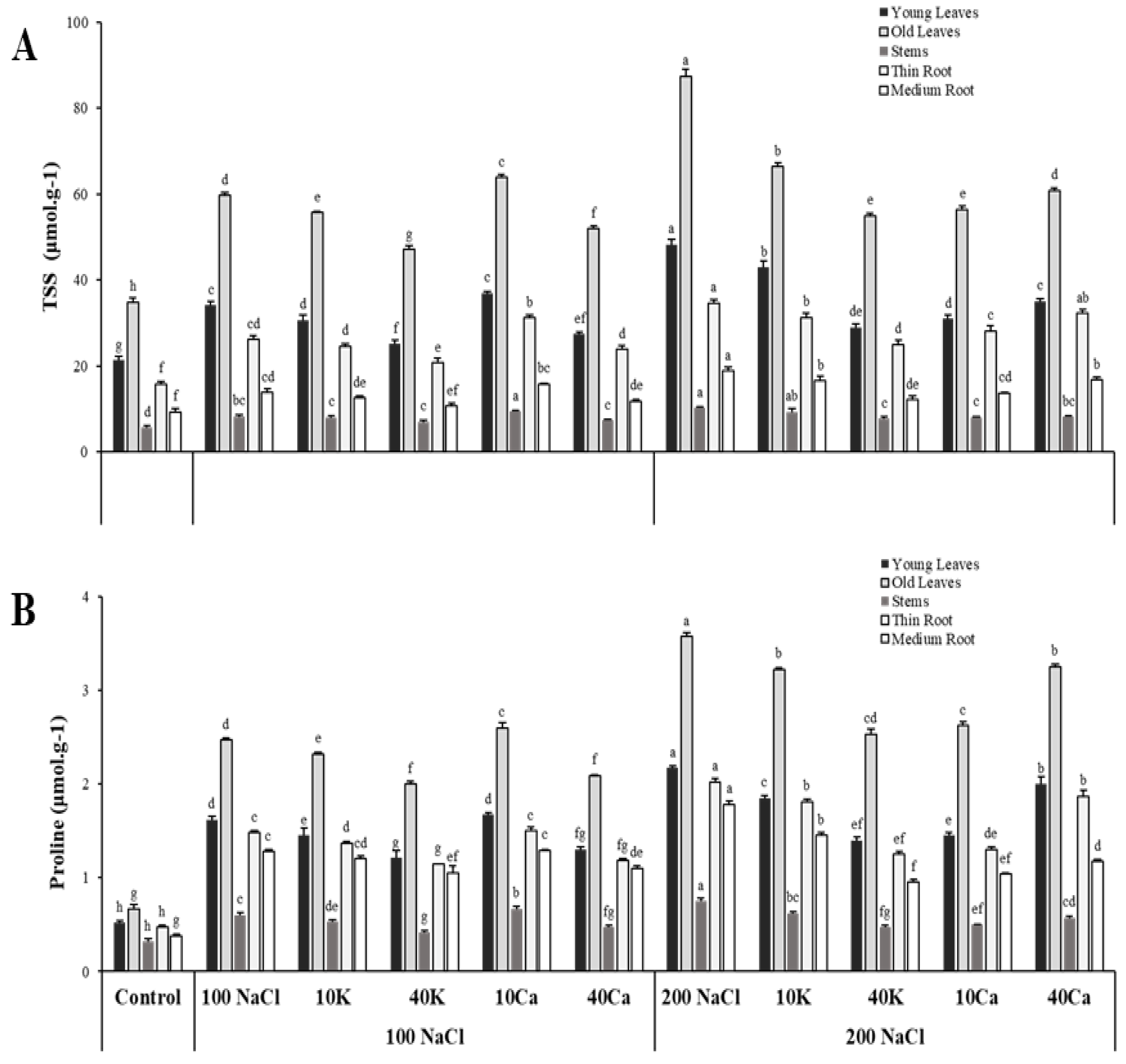

3.3. Soluble Sugar and Proline Accumulation

3.4. Photosynthetic Pigments

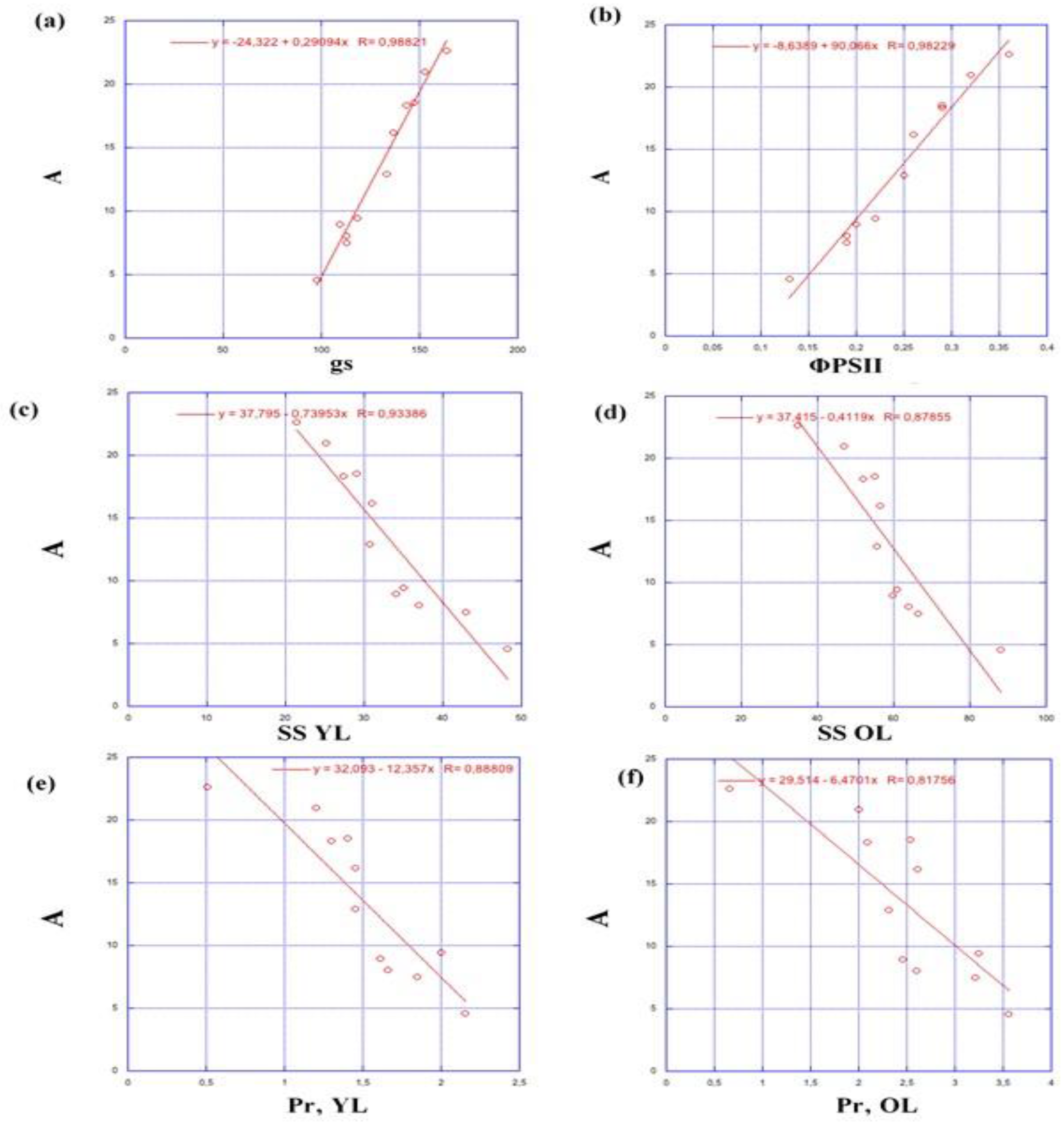

3.5. Physiological and Biochemical Interactions

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Pacifici, M.; Foden, W.B.; Visconti, P.; Watson, J.E.M.; Butchart, S.H.M.; Kovacs, K.M.; Scheffers, B.R.; Hole, D.G.; Martin, T.G.; Akçakaya, H.R.; Corlett, R.T.; Huntley, B.; Bickford, D.; Carr, J.A.; Hoffmann, A.A.; Midgley, G.F.; Kelly, P.P.; Pearson, R.G.; Williams, S.E.; Willis, S.G.; Young, B.; Rondinini, C. Assessing species vulnerability to climate change. Nat. Clim. Chang. 2015, 5, 215–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okur, B.; Orçen, N. Soil salinization and climate change. In Climate change and soil interactions; Prasad, M.N.V., Pietrzykowski, M., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, 2020; pp. 331–350. [Google Scholar]

- Munns, R.; Tester, M. Mechanisms of salinity tolerance. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2008, 59, 651–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azimi, M.; Khoshzaman, T.; Taheri, M.; Dadras, A.R. Evaluation of salinity tolerance of three olive (Olea europaea L.) cultivars. J. Cent. Eur. Agric. 2021, 22, 571–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vigo, C.; Therios, I.N.; Bosabalidis, M. Plant growth, nutrient concentration and leaf anatomy of olive plants irrigated with diluted seawater. J. Plant Nutr. 2005, 28, 1001–1021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapulnik, Y.; Tsror, L.; Zipori, I.; Hazanovsky, M.; Wininger, S.; Dag, A. Effect of AMF application on growth, productivity and susceptibility to Verticillium Wilt of olives grown under desert conditions. Symbiosis 2010, 52, 103–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boussadia, O.; Zgallai, H.; Mzid, N.; Zaabar, R.; Braham, M.; Doupis, G.; Koubouris, G. Physiological responses of two olive cultivars to salt stress. Plants 2023, 12, 1926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vergine, M.; Palm, E.R.; Salzano, A.M.; Negro, C.; Nissim, W.G.; Sabbatini, L.; Balestrini, R.; Pinto, M.C.; Dipierro, N.; Gohari, G.; Fotopoulos, V.; Mancuso, S.; Luvisi, A.; Bellis, L.; Scaloni, A.; Vita, F. Water and nutrient availability modulate the salinity stress response in Olea europaea cv. Arbequina. Plant Stress 2024, 14, 100648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, I.F.; Maybelle, G.; Bedour, A.L.; Proietti, P.; Regni, L. Salinity stress effects on three different olive cultivars and the possibility of their cultivation in reclaimed lands. Plant Arch. 2020, 20, 2378–2382. [Google Scholar]

- Larbi, A.; Kchaou, H.; Gaaliche, B.; Gargouri, K.; Boulal, H.; Morales, F. Supplementary potassium and calcium improves salt tolerance in olive plants. Sci. Hortic. 2020, 260, 108912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taha, R.S.; Seleiman, M.F.; Alotaibi, M.; Alhammad, B.A.; Rady, M.M.; Mahdi, A.H.A. Exogenous potassium treatments elevate salt tolerance and performances of Glycine max L. by boosting antioxidant defense system under actual saline field conditions. Agronomy 2020, 10, 1741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Schmidhalter, U. Drought and salinity: A comparison of their effects on mineral nutrition of plants. J. Plant Nutr. Soil Sci. 2005, 168, 541–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gucci, R.; Lombardini, L.; Tattini, M. Analysis of leaf water relations in leaves of two olive (Olea europaea) cultivars differing in tolerance to salinity. Tree Physiol. 1997, 17, 13–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rugini, E.; Baldoni, L.; Muleo, R.; Sebastiani, L. The Olive Tree Genome; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Loupassaki, M.H.; Chartzoulakis, K.S.; Digalaki, N.B.; Androulakis, I.I. Effects of salt stress on concentration of nitrogen, phosphorus, potassium, calcium, magnesium, and sodium in leaves, shoots, and roots of six olive cultivars. J. Plant Nutr. 2002, 25, 2457–2482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tattini, M.; Melgar, J.C.; Traversi, M.L. Responses of Olea europaea to high salinity: a brief-ecophysiological review. Adv. Hort. Sci. 2008, 22, 159–173. [Google Scholar]

- Genty, B.; Briantais, J.M.; Baker, N.R. The relationship between the quantum yield of photosynthetic electron transport and quenching of chlorophyll fluorescence. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1989, 990, 87–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilger, W.; Björkman, O. Role of the xanthophyll cycle in photoprotection elucidated by measurements of light-induced absorbance changes, fluorescence and photosynthesis in leaves of Hedera canariensis. Photosynth. Res. 1990, 25, 173–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kchaou, H.; Larbi, A.; Chaieb, M.; Sagardoy, R.; Msallem, M.; Morales, F. genotypic differentiation in the stomatal response to salinity and contrasting photosynthetic and photoprotection responses in five olive (Olea europaea L.) Cultivars. Sci. Hortic. 2013, 160, 129–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bates, L.S.; Waldren, R.P.; Teare, I.D. Rapid determination of free proline for water-stress studies. Plant Soil 1973, 39, 205–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robyt, J.F.; White, B.J. Biochemical Techniques: Theory and Practice; Brooks/Cole: Monterey, CA, USA, 1987; p. 217. [Google Scholar]

- Melgar, J.C.; Mohamed, Y.; Ben Yahmed, J.; Abadia, A.; Abadia, J.; Gomez, J.A. Long-term responses of olive trees to salinity. Agric. Water Manag. 2009, 96, 1105–1113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chartzoulakis, K.; Loupassaki, M.; Bertaki, M.; Androulakis, I. Response of two olive cultivars to salt stress and potassium supplement. J. Plant Nutr. 2006, 29, 2063–2078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cha-um, S.; Yooyongwech, S.; Supaibulwatana, K.; Kirdmanee, C. Water relations, pigment stabilization, photosynthetic abilities and growth improvement in salt stressed rice plants treated with exogenous potassium nitrate application. Int. J. Plant Prod. 2010, 4, 187–198. [Google Scholar]

- Jafari, M.H.S.; Abbasi, A.R.; Mousavi, S.F. Interactive effects of NaCl induced salinity, calcium, and potassium on physio-morphological traits of Sorghum (Sorghum bicolor L.). Pak. J. Bot. 2009, 41, 3053–3063. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, M.; Zheng, Q.; Shen, Q.; Guo, S. The critical role of potassium in plant stress response. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2013, 14, 7370–7390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tattini, M.; Traversi, M.L.; Pinelli, P.; Leonardi, C.; Noferini, M.; Faccio, A.; Fini, A. Contrasting response mechanisms to root-zone salinity in three co-occurring Mediterranean woody evergreens: A physiological and biochemical study. Funct. Plant Biol. 2009, 36, 551–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sultana, N.; Ikeda, T.; Kashem, M.A. Effect of foliar spray of nutrient solutions on photosynthesis, dry matter accumulation and yield in seawater-stressed rice. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2001, 46, 129–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebert, G.; Eichert, T.; Fernández, V.; Müller, B.; Römheld, V. Ameliorating effects of Ca(NO₃)₂ on growth, mineral uptake and photosynthesis of NaCl-stressed guava seedlings (Psidium guajava L.). Sci. Hortic. 2002, 93, 125–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaya, C.; Higgs, D. Ameliorative effects of potassium phosphate on salt stressed pepper and cucumber. J. Plant Nutr. 2002, 26, 807–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tzortzakis, N.G. Potassium and calcium enrichment alleviate salinity-induced stress in hydroponically grown endives. Hort. Sci. 2010, 37, 155–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roussos, P.A.; Koubouris, G.C.; Tsantili, E. Intra- and inter-cultivar impacts of salinity stress on leaf photosynthetic performance, carbohydrates and nutrient content of nine indigenous Greek olive cultivars. Acta Physiol. Plant. 2017, 39, 136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buono, D.; Muzzalupo, I.; Perri, E.; Rinaldi, R.; Rinaldi, A.; Caira, S.; Ruggiero, A.; Balestrieri, M.L. Effects of Megafol on the olive cultivar ‘Arbequina’ grown under severe saline stress in terms of physiological traits, oxidative stress, antioxidant defenses, and cytosolic Ca²⁺. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 11, 603576. [Google Scholar]

- Skodra, C.; Pateraki, I.; Madesis, P.; Kalaitzis, P. Unraveling salt-responsive tissue-specific metabolic pathways in olive tree. Physiol. Plant. 2021, 173, 13565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trabelsi, L.; Smaoui, A.; Ksouri, R.; Triki, M.A.; Oueslati, S. The effect of drought and saline water on the nutritional behaviour of the olive tree (Olea europaea L.) in an arid climate. S. Afr. J. Bot. 2024, 165, 126–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Restrepo-Diaz, H.; Benlloch, M.; Navarro, C.; Fernandez, J.E. Potassium fertilization of rainfed olive orchards. Sci. Hortic. 2008, 116, 399–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdolzadeh, A.; Karimi, E.; Sadeghipour, H.R. Increasing salt tolerance in olive, Olea europaea L. plants by supplemental potassium nutrition involves changes in ion accumulation and anatomical attributes. Int. J. Plant Prod. 2009, 3, 49–60. [Google Scholar]

- El Khouni, A.; El Aouni, M.H.; Ghnaya, T.; Abdelly, C.; Gouia, H. Structural and functional integrity of Sulla carnosa photosynthetic apparatus under iron deficiency conditions. Plant Biol. 2018, 20, 415–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Netondo, G.W.; Onyango, J.C.; Beck, E. Sorghum and salinity II. Gas exchange and chlorophyll fluorescence of sorghum under salt stress. Crop Sci. 2004, 44, 806–811. [Google Scholar]

- Chaves, M.M.; Flexas, J.; Pinheiro, C. Photosynthesis under drought and salt stress: Regulation mechanisms from whole plant to cell. Ann. Bot. 2009, 103, 551–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaya, C.; Kirnak, H.; Higgs, D.; Saltali, K. Supplementary calcium enhances plant growth and fruit yield in strawberry cultivars grown at high (NaCl) salinity. Sci. Hortic. 2002, 93, 65–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boualem, S.; Boutaleb, S.; Boukhalfa-Deraoui, N. Effect of salinity on the physiological behavior of the olive tree (variety Sigoise). J. Fundam. Appl. Sci. 2019, 11, 525–538. [Google Scholar]

- Ayaz, M.; Hakki, E.E.; Ercisli, S.; Cakir, O.; Tanyolac, B. Three Turkish olive cultivars display contrasting salt stress-coping mechanisms under high salinity. Trees 2021, 35, 1283–1298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Yamani, M.; Cordovilla, M.P. Tolerance mechanisms of olive tree (Olea europaea) under saline conditions. Plants 2024, 13, 2094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ben Ahmed, C.; Ben Rouina, B.; Sensoy, S.; Boukhris, M.; Abdallah, F.B. Changes in water relations, photosynthetic activity and proline accumulation in one-year-old olive trees (Olea europaea L. cv. Chemlali) in response to NaCl salinity. Acta Physiol. Plant. 2008, 30, 553–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poury, N.; Kholdebarin, B.; Shariati, M. Effects of salinity and proline on growth and physiological characteristics of three olive cultivars. Gesunde Pflanzen 2023, 75, 1169–1111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mozafari, M.R.; Johnson, C.; Hatziantoniou, S.; Demetzos, C. Nanoliposomes and their applications in food nanotechnology. J. Liposome Res. 2008, 18, 309–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Z.; Wang, Z.; Ma, Q.; Sun, L.; Liu, Z.; Zhai, S.; Xu, J.; Cui, X.; Jiang, D.; Cao, W. Potassium supply improves salt tolerance in wheat through better K/Na ratio and enhanced antioxidative metabolism. Plant Sci. 2015, 230, 103–111. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, J.K. Abiotic stress signaling and responses in plants. Cell 2016, 167, 313–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farooq, M.; Nawaz, A.; Chaudhary, H.J.; Rehman, A.; Nadeem, F.; Ali, Q.; Zahoor, R. Morphological, physiological and biochemical aspects of zinc seed priming-induced drought tolerance in faba bean. Sci. Hortic. 2021, 281, 109894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Ma, Q.; Jin, Z.; Wang, Z.; Wang, J.; Jia, H.; Chen, W.; Deng, Q.; Ding, Y. Physiological, proteomic and metabolomic analysis provide insights into Bacillus sp. mediated salt tolerance in wheat. Plant Cell Rep. 2022, 41, 95–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flexas, J.; Bota, J.; Loreto, F.; Cornic, G.; Sharkey, T.D. Keeping a positive carbon balance under adverse conditions: Responses of photosynthesis and respiration to water stress. Physiol. Plant. 2004, 122, 545–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villalobos, F.J.; López-Bernal, Á.; García-Tejera, O.; Testi, L. Is olive crop modelling ready to assess the impacts of global change? Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1249793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karaca, C.; Aslan, G.E.; Kurunc, A.; Baştug, R.; Navarro, A.; Buyuktas, D. Effect of irrigation water salinity on physiological parameters and yield of tomato plants across phenological stages. Earth Sci. Hum. Constr. 2024, 4, 177–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cakmak, I. The role of potassium in alleviating detrimental effects of abiotic stresses in plants. J. Plant Nutr. Soil Sci. 2005, 168, 521–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Yuan, Z.; Wei, Z.; Yan, F.; Liu, X.; Li, X.; Hou, J.; Hao, Z.; Liu, F. Stomatal and non-stomatal regulations of photosynthesis in response to salinity, and K and Ca fertigation in cotton (Gossypium hirsutum L. cv.). Environ. Exp. Bot. 2025, 230, 106092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flexas, J.; Medrano, H. Drought-inhibition of photosynthesis in c3 plants: stomatal and non-stomatal limitations revisited. Ann. Bot. 2002, 89, 183–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guerfel, M.; Baccouri, O.; Boujnah, D.; Chaïbi, W.; Zarrouk, M. impacts of water stress on gas exchange, water relations, chlorophyll content and leaf structure in the two main tunisian olive (Olea europaea L.) cultivars. Sci. Hortic. 2009, 119, 257–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rady, M.M.; Taha, R.S.; Semida, W.M.; Alharby, H.F. Modulation of salt stress effects on Vicia faba L. plants grown on a reclaimed-saline soil by salicylic acid application. Rom. Agric. Res. 2017, 34, 175–185. [Google Scholar]

| Treatment | Total Chl | Chl a/b | β-Carotene | Lutein | Neoxanthin | VAZ | (A+Z)/(V+A+Z) | Lutein/Chl | V+A+Z/Chl |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | 655±10bc | 2.54±0.67a | 54±90a | 91±17a | 31±50abc | 63±16a | 0.17±0.04cd | 0.14±0.01abc | 0.09±0.01ab |

| 100 | 556±44c | 3.18±0.39a | 61±19abc | 98±18a | 26±00abcd | 60±12a | 0.28±0.08abc | 0.18±0.01abc | 0.11±0.02ab |

| 100-10K | 588±73c | 2.87±0.35a | 61±29abc | 109±33a | 27±90abcd | 61±21a | 0.26±0.09bcd | 0.18±0.04abc | 0.10±0.02ab |

| 100-40K | 652±74bc | 2.66±0.82a | 57±50ab | 93±13a | 29±00abcd | 60±90a | 0.24±0.08bcd | 0.14±0.04abc | 0.09±0.02ab |

| 100-10Ca | 894±23ab | 3.05±0.14a | 73±38ab | 98±34a | 21±30cd | 47±21a | 0.11±0.09d | 0.12±0.07bc | 0.06±0.03b |

| 100-40Ca | 627±16c | 2.74±0.71a | 49±11ab | 94±50a | 35±13ab | 60±13a | 0.26±0.08bcd | 0.15±0.05abc | 0.10±0.01ab |

| 200 | 552±98c | 3.32±0.62a | 70±11c | 116±23a | 18±90d | 68±15a | 0.42±0.07a | 0.21±0.07a | 0.13±0.04a |

| 200-10K | 620±87c | 3.10±0.19a | 67±90bc | 105±50a | 31±30abc | 79±59a | 0.25±0.13bcd | 0.17±0.03abc | 0.12±0.07a |

| 200-40K | 961±24a | 3.05±0.13a | 47±16abc | 98±70a | 38±80a | 57±10a | 0.23±0.04bcd | 0.11±0.03bc | 0.06±0.02b |

| 200-10Ca | 1031±11a | 3.08±0.02a | 57±11abc | 103±60a | 35±40ab | 60±10a | 0.25±0.05bcd | 0.10±0.01c | 0.06±0.00b |

| 200-40Ca | 587±10c | 3.22±0.07a | 69±17ab | 105±11a | 23±40bcd | 68±17a | 0.36±0.08ab | 0.18±0.04ab | 0.11±0.01ab |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).