Submitted:

10 June 2025

Posted:

11 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

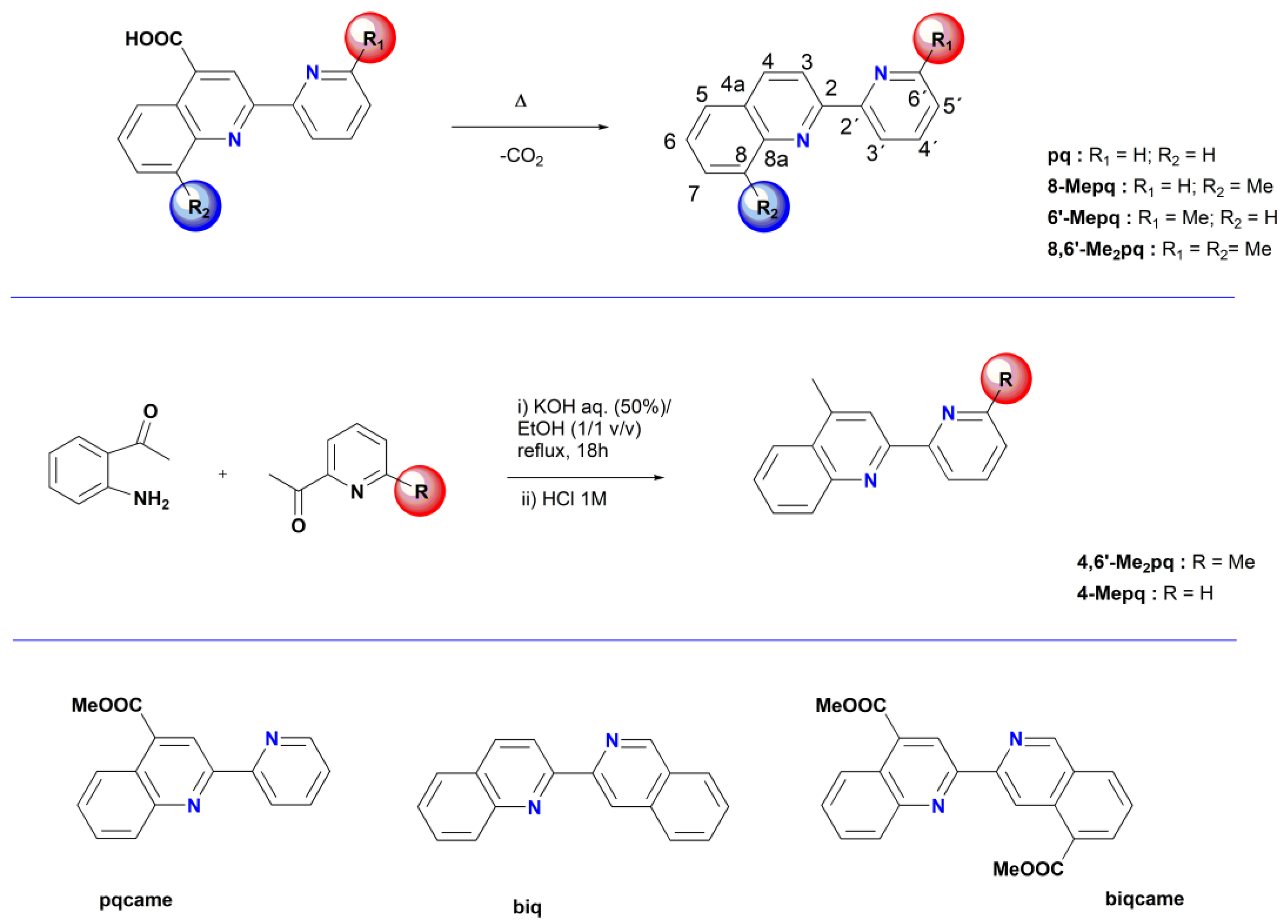

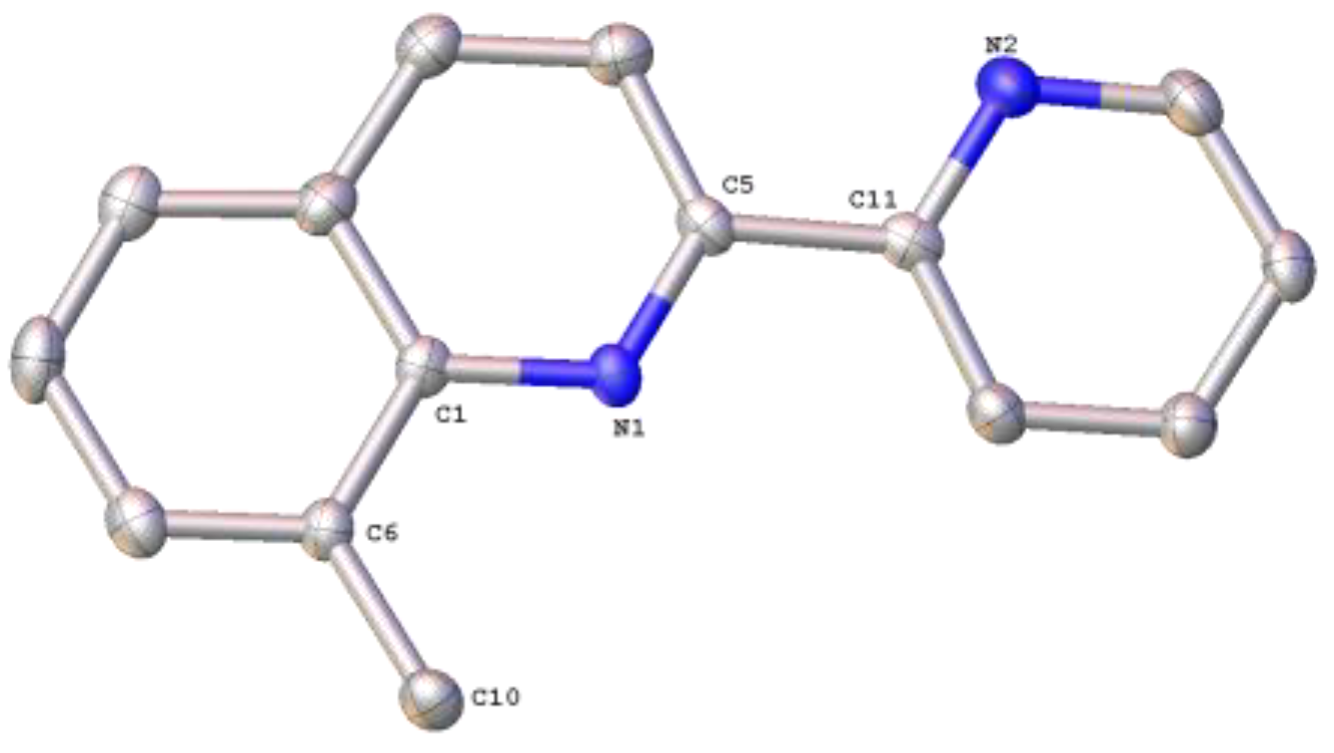

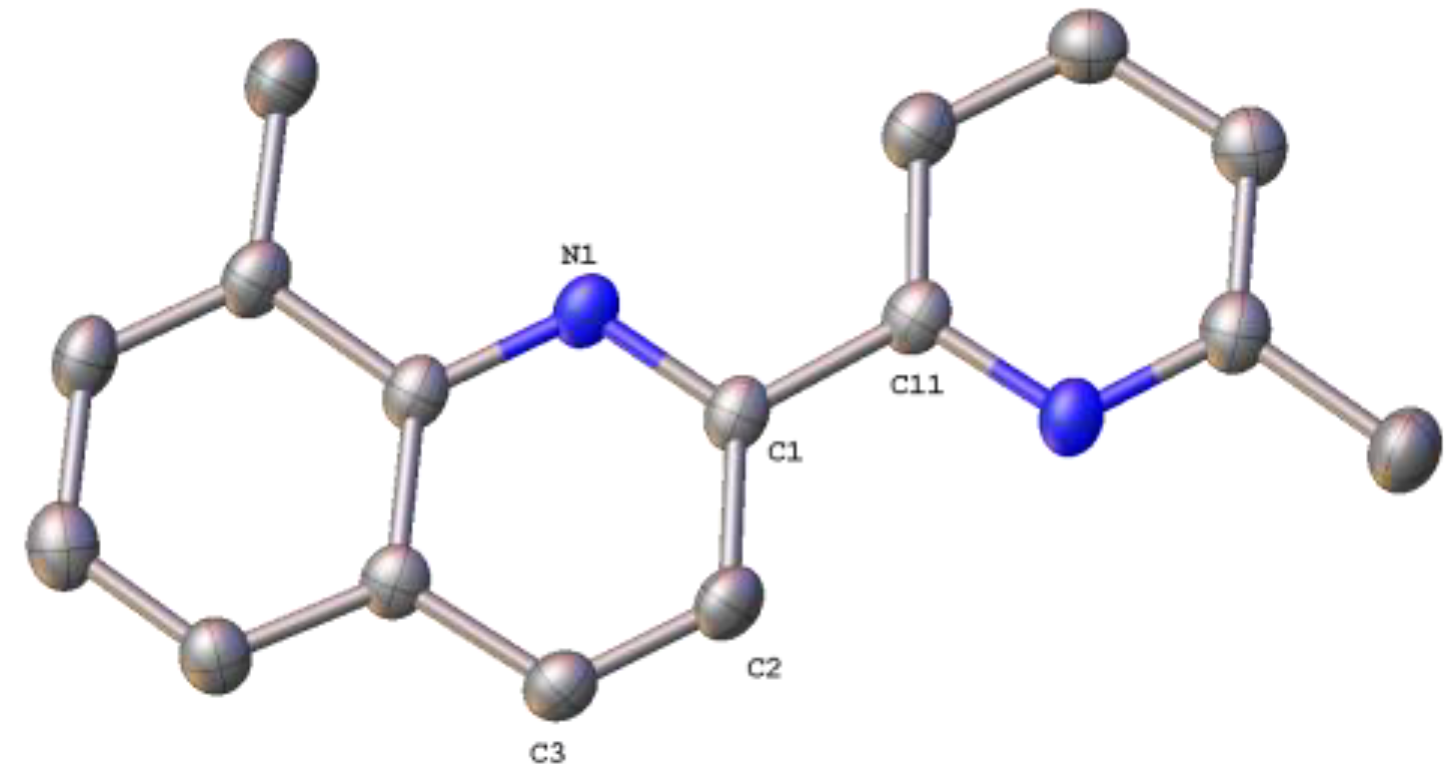

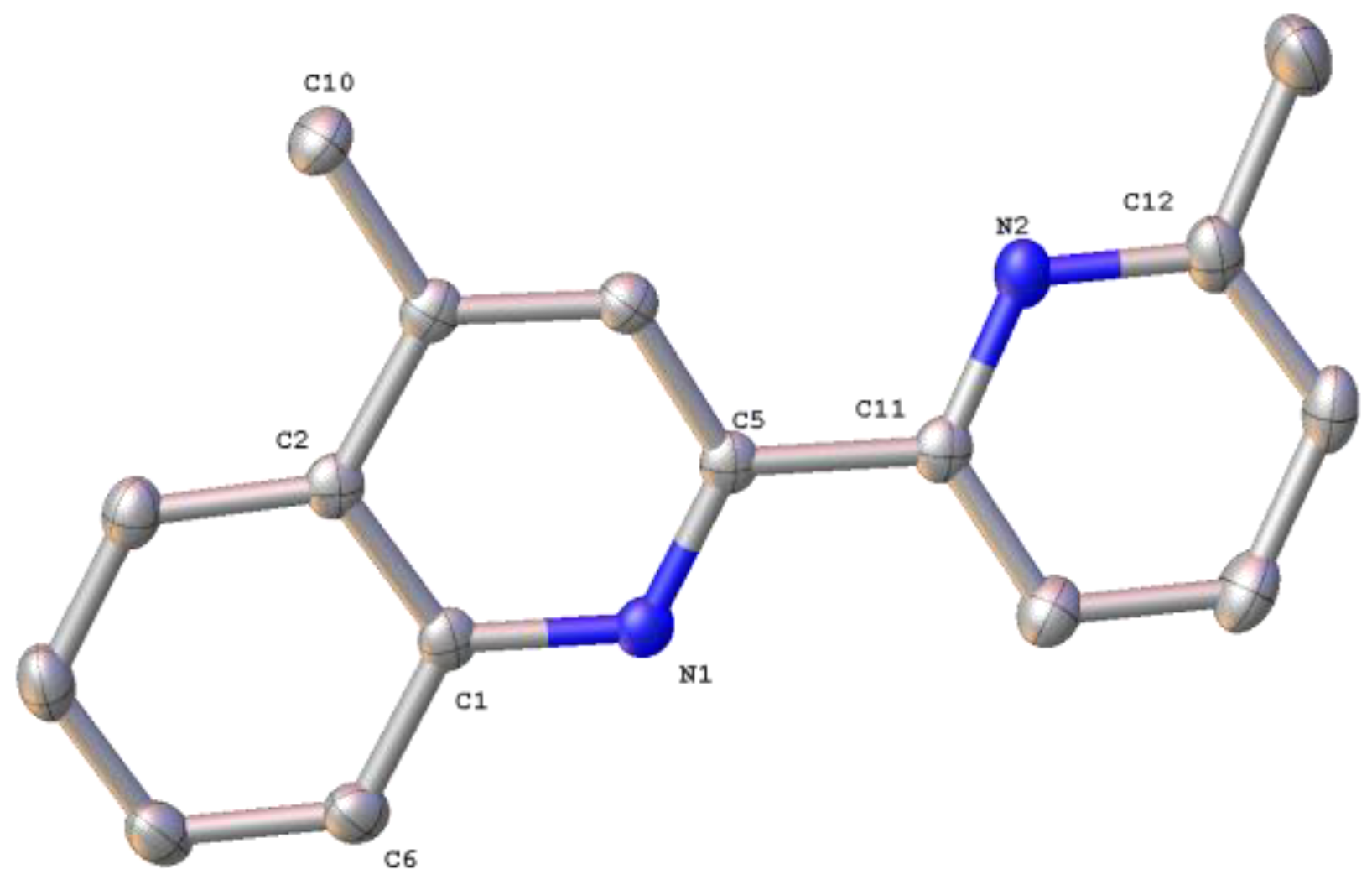

2.1. Synthesis, Spectroscopic and Structural Characterization of the Organic Ligands

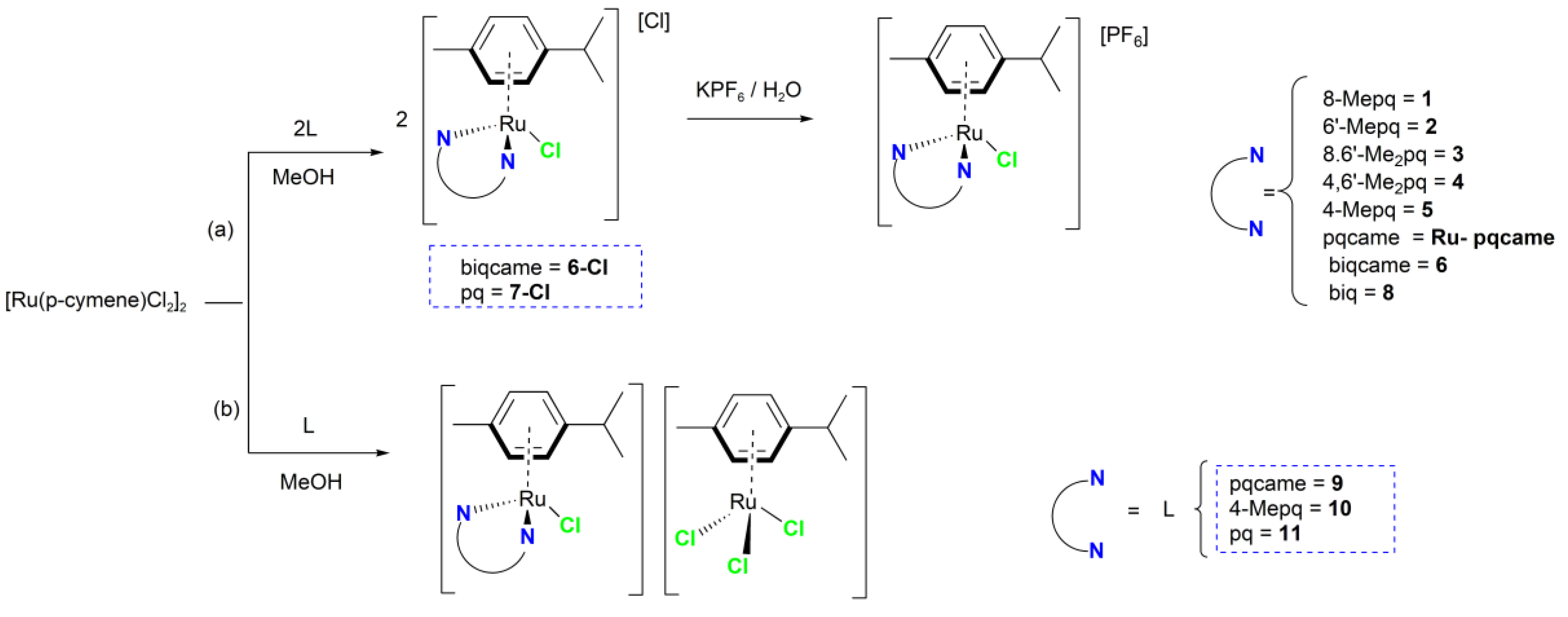

2.2. Synthesis and Characterization of the Ruthenium(II) Complexes 1–8

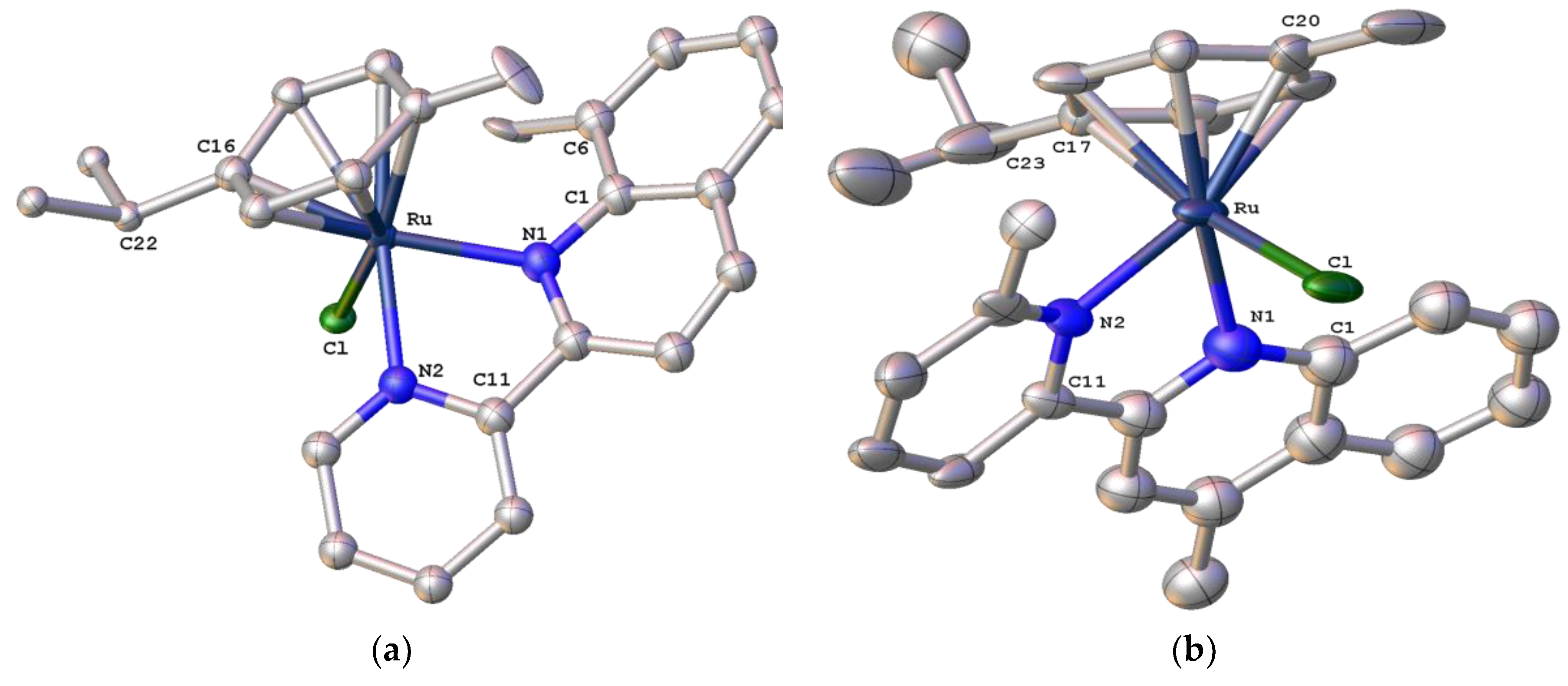

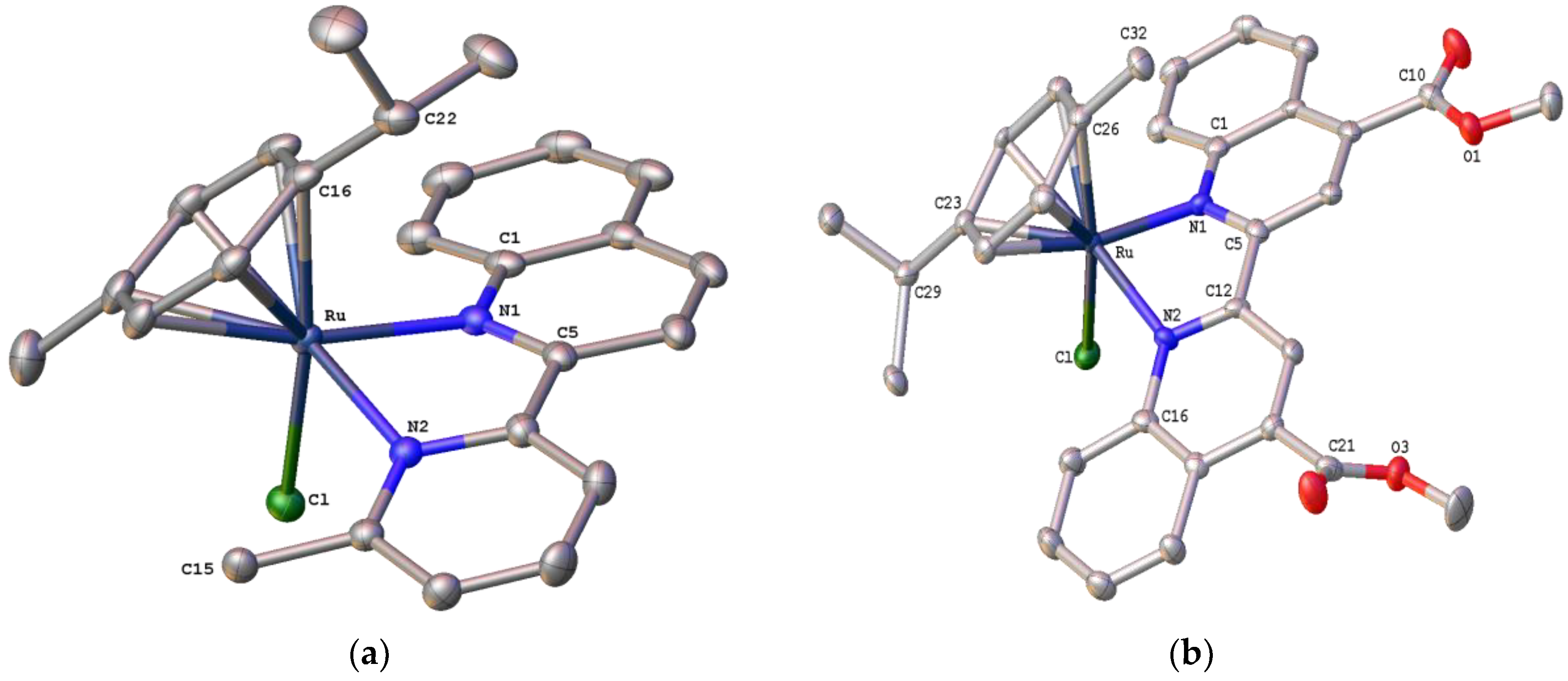

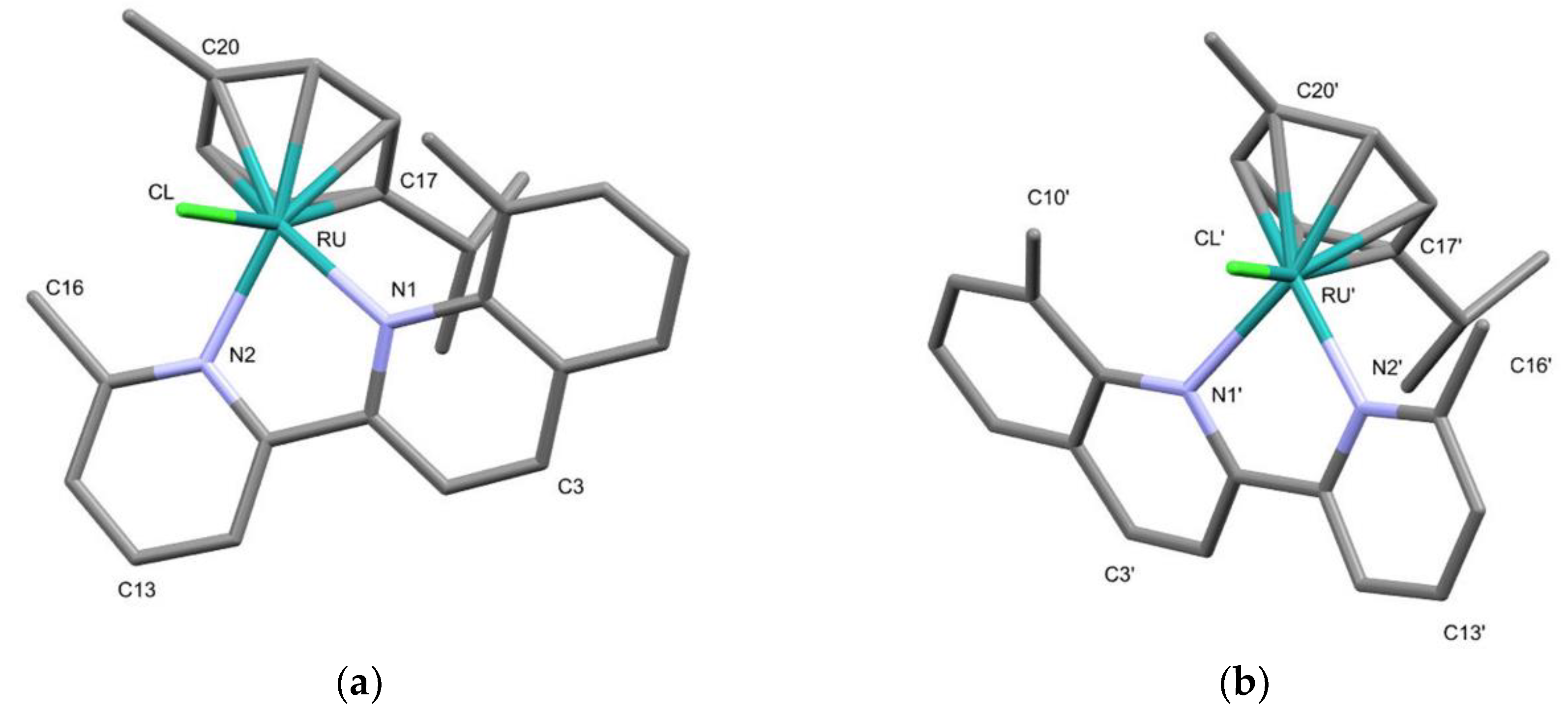

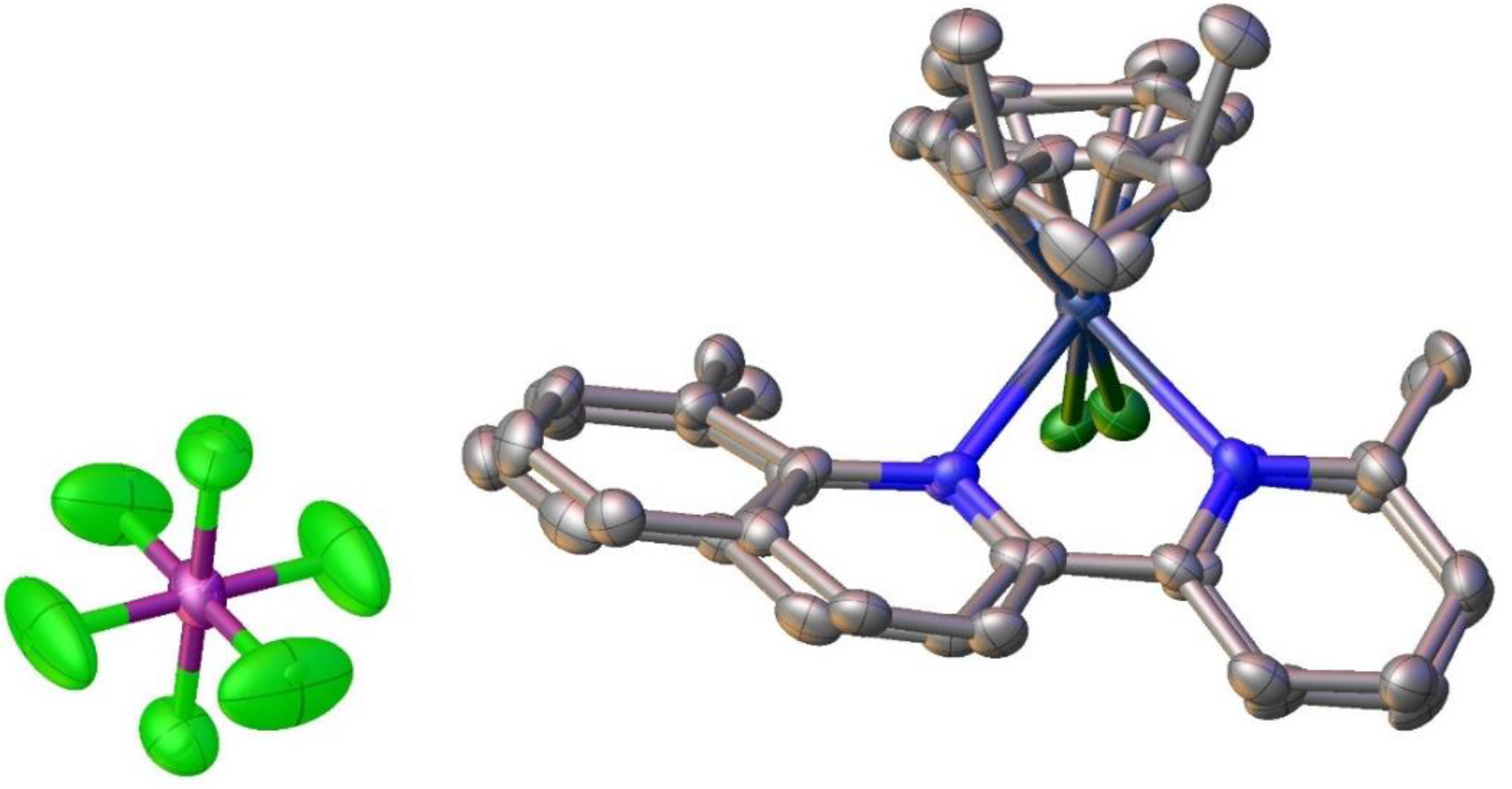

2.3. Structural Characterization of Complexes 1–4 and 6

2.4. Synthesis and Characterization of the Ruthenium(II) Complexes 9–11

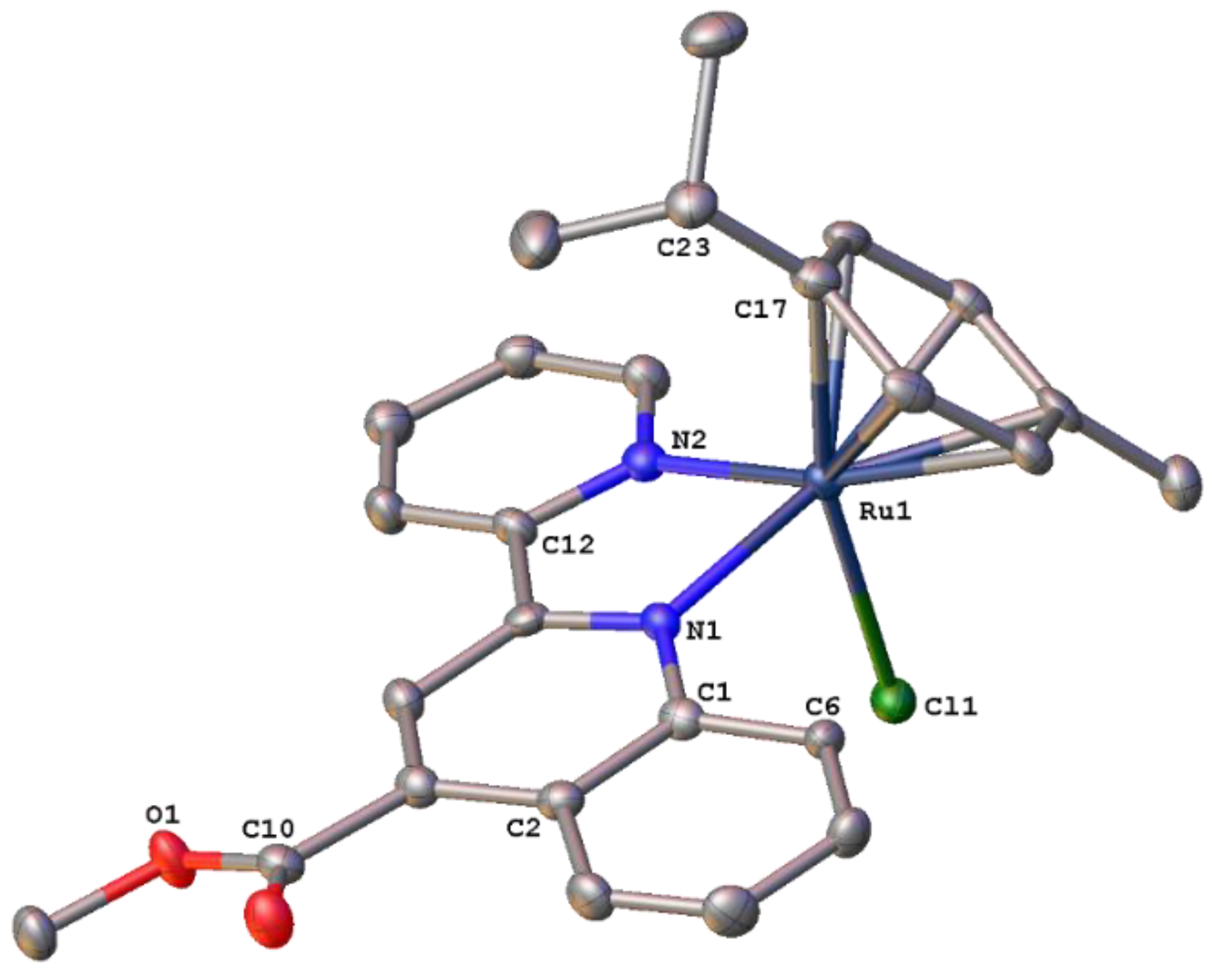

2.5. Structural Characterization of Complex [Ru(η6-p-cymene)(pqcame)Cl][Ru(p-cymene)Cl3]• CH2Cl2 (9)

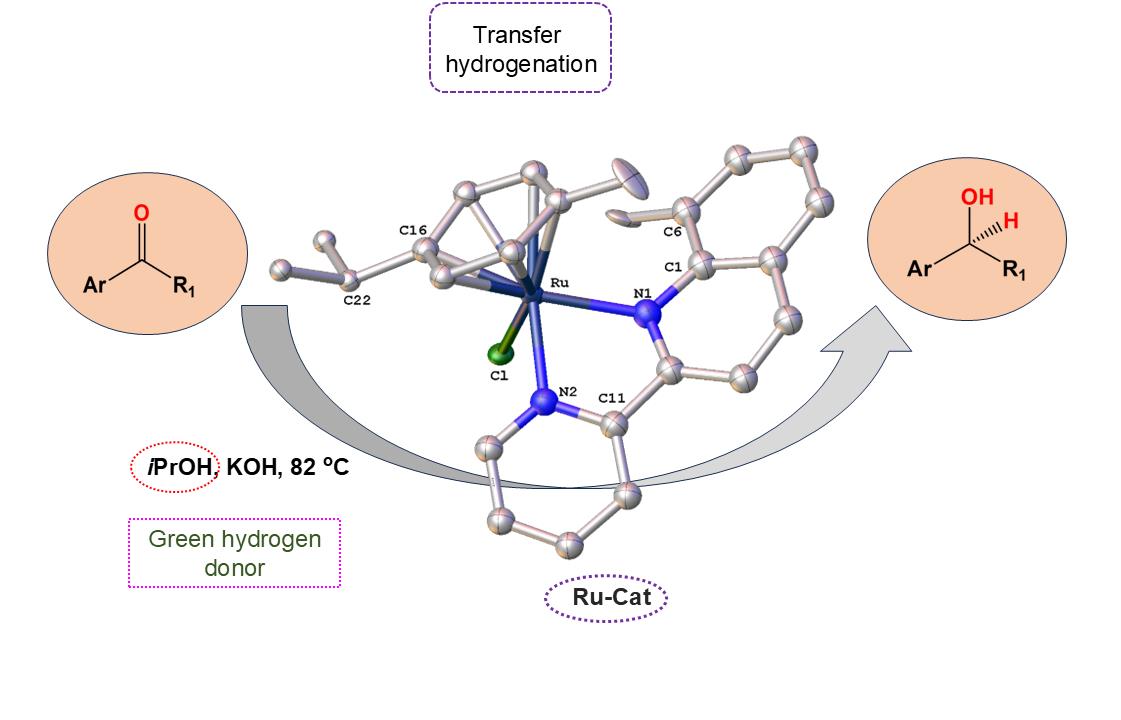

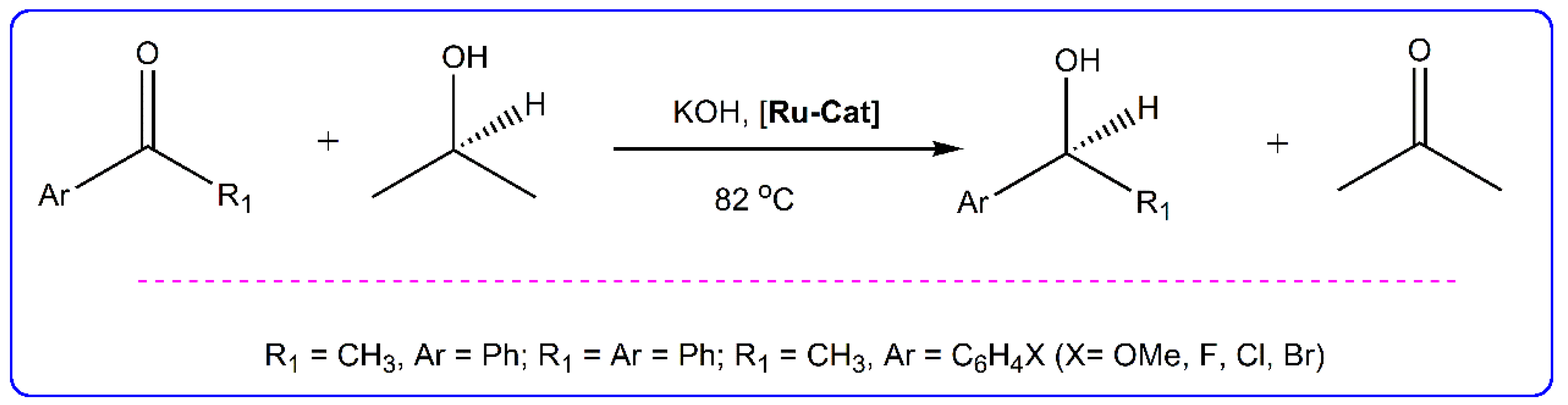

2.6. Catalytic Transfer Hydrogenation Studies

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Synthesis and Characterization

3.1.1. Synthesis of the Organic Ligands 8-Mepq, 6′-Mepq, 8,6′-Me2pq and pq

3.1.2. Synthesis of the Organic Ligand 4,6′-Me2pq

3.1.3. General Synthetic Procedure of Complexes 1–8

3.1.4. Data for Complexes 1–8

3.2. General Synthetic Procedure of Complexes 9–11

Data for Complexes 9–11

3.3. Single-Crystal X-Ray Structural Determination

3.4. Catalytic Transfer Hydrogenation Experiment

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Blaser, H.U.; Malan, C.; Pugin, B.; Spindler, F.; Steiner, H.; Studer, M. Selective Hydrogenation for Fine Chemicals: Recent Trends and New Developments. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2003, 345, 103–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taleb, B.; Jahjah, R.; Cornu, D.; Bechelany, M.; Al Ajami, M.; Kataya, G.; Hijazi, A.; El-Dakdouki, M.H. Exploring Hydrogen Sources in Catalytic Transfer Hydrogenation: A Review of Unsaturated Compound Reduction. Molecules 2023, 28, 7541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Astruc, D. The Golden Age of Transfer Hydrogenation. Chem. Rev. 2015, 115, 6621–6686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baidilov, D.; Hayrapetyan, D.; Khalimon, A.Y. Recent advances in homogeneous base-metal-catalyzed transfer hydrogenation reactions. Tetrahedron 2021, 98, 132435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Y.-F.; Liang, Y.; Luo, R.; Ouyang, L. Recent advances of Cp*Ir complexes for transfer hydrogenation: focus on formic acid/formate as hydrogen donors. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2023, 21, 7484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cocker, J.D.; Henbest, H.B.; Phillipps, G.H.; Slater, G.P.; Thomas, D.A. 2. Reactions of ketones with oxidising agents. Part II. Acetoxylation of 11- and 20-oxo-steroids with lead tetra-acetate in the presence of boron trifluoride. J. Chem. Soc 1965, 6–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sasson, Y.; Albin, P.; Blum, J. Effect of a Ru (II) catalyst on the rate of equilibration of carbinols and ketones. Tetrahedron Lett. 1974, 15, 833–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowdhury, R.L.; Bäckvall, J.-E. Efficient ruthenium-catalysed transfer hydrogenation of ketones by propan-2-ol. J.Chem. Soc. Chem. Commun. 1991, 16, 1063–1064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noyori, R. Asymmetric Catalysis: Science and Opportunities (Nobel Lecture). Angew Chem. Int Ed. 2002, 41, 2008–2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, R.H. Asymmetric hydrogenation, transfer hydrogenation and hydrosilylation of ketones catalyzed by iron complexes. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2009, 38, 2282–2291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, N.B.; Lennon, I.C.; Moran, P.H.; Ramsden, J.A. Industrial-Scale Synthesis and Applications of Asymmetric Hydrogenation Catalysts. Acc. Chem. Res. 2007, 40, 1291–1299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fovanna, T.; Campisi, S.; Villa, A.; Kambolis, A.; Peng, G.; Rentsch, D.; .Kröcher, O.; Nachtegaal, M.; Ferri, D. Ruthenium on phosphorous-modified alumina as an effective and stable catalyst for catalytic transfer hydrogenation of furhfural. RSC Adv. 2020, 10, 11507–11516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soldevila-Barreda, J.J.; Romero-Canelón, I.; Habtemariam, A.; Sadler, P.J. Transfer hydrogenation catalysis in cells as a new approach to anticancer drug design. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 6582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Banerjee, S.; Sadler, P.J. Transfer hydrogenation catalysis in cells. RSC Chem. Biol. 2021, 2, 12–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comas-Vives, A.; Ujaque, G.; Lledós, A. Inner- and Outer-Sphere Hydrogenation Mechanisms: A Computational Perspective. In Theoretical and Computational Inorganic Chemistry; van Eldik, R., Harvey, J., Eds.; Academic Press, 2010; pp. 231–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Yue, X.; Luo, C.; Zhang, L.; Lei, M. Mechanisms of Ketone/Imine Hydrogenation Catalyzed by Transition-Metal Complexes. ENERGY Environ. Mater. 2019, 2, 292–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khusnutdinova, J.R.; Milstein, D. Metal–Ligand Cooperation. Angew. Chem. Int Ed. 2015, 54, 12236–12273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Guillet, S.G.; Liu, Y.; Cazin, C.S.J.; Nolan, S.P. Simple synthesis of [Ru(CO3)(NHC)(p-cymene)] complexes and their use in transfer hydrogenation catalysis. DaltonTrans. 2021, 50, 13012–13019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mannu, A.; Grabulosa, A.; Baldino, S. Transfer Hydrogenation from 2-propanol to Acetophenone Catalyzed by [RuCl2(η6-arene)P] (P = monophosphine) and [Rh(PP)2]X (PP = diphosphine, X = Cl−, BF4−) Complexes. Catalysts 2020, 10, 162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandiarajan, D.; Ramesh, R. Ruthenium(II) half-sandwich complexes containing thioamides: Synthesis, structures and catalytic transfer hydrogenation of ketones. J. Organomet. Chem. 2013, 723, 26–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hounjet, L.J.; Ferguson, M.J.; Cowie, M. Phosphine–Amido Complexes of Ruthenium and Mechanistic Implications for Ketone Transfer Hydrogenation Catalysis. Organometallics 2011, 30, 4108–4114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alonso, D.A.; Brandt, P.; Nordin, S.J.M.; Andersson, P.G. Ru(arene)(amino alcohol)-Catalyzed Transfer Hydrogenation of Ketones: Mechanism and Origin of Enantioselectivity. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1999, 121, 9580–9588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romain, C.; Gaillard, S.; Elmkaddem, M.K.; et al. New Dipyridylamine Ruthenium Complexes for Transfer Hydrogenation of Aryl Ketones in Water. Organometallics 2010, 29, 1992–1995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Türkmen, H.; Kani, İ.; Çetinkaya, B. Transfer Hydrogenation of Aryl Ketones with Half-Sandwich RuII Complexes That Contain Chelating Diamines. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2012, 4494–4499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nieto, I.; Livings, M.S.; Sacci, J.B.; Reuther, L.E.; Zeller, M.; Papish, E.T. Transfer Hydrogenation in Water via a Ruthenium Catalyst with OH Groups near the Metal Center on a bipy Scaffold. Organometallics 2011, 30, 6339–6342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matveevskaya, V.V.; Pavlov, D.I.; Sukhikh, T.S.; Gushchin, A.L.; Ivanov, A.Y.; Tennikova, T.B.; Sharoyko, V.V.; Baykov, S.V.; Benassi, E.; Potapov, A. S Arene–Ruthenium(II) Complexes Containing 11H-Indeno[1,2-b]quinoxalin-11-one Derivatives and Tryptanthrin-6-oxime: Synthesis, Characterization, Cytotoxicity, and Catalytic Transfer Hydrogenation of Aryl Ketones. ACS Omega 2020, 5, 11167–11179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matveevskaya, V.V.; Pavlov, D.I.; Samsonenko, D.G.; Ermakova, E.A.; Klyushova, L.S.; Baykov, S.V.; Boyarskiy, V.P.; Potapov, A.S. Synthesis and Structural Characterization of Half-Sandwich Arene–Ruthenium(II) Complexes with Bis(imidazol-1-yl)methane, Imidazole and Benzimidazole. Inorganics 2021, 9, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erdem, A.; Kılınçarslan, R.; Şahin, Ç.; Dayan, O.; Özdemir, N. Synthesis, thermal, electrochemical and catalytic behavior toward transfer hydrogenation investigations of the half-sandwich RuII complexes with 2-(2′-quinolyl)benzimidazoles. J. Mol. Struct. 2020, 1220, 128556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dayan, S.; Ozpozan Kalaycioglu, N.; Daran, J.-C.; Labande, A.; Poli, R. Synthesis and Characterization of Half-Sandwich Ruthenium Complexes Containing Aromatic Sulfonamides Bearing Pyr id inyl Rings: Catalysts for Transfer Hydrogenation of Acetophenone Derivatives. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2013, 3224–3232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zacharopoulos, N.; Koukoulakis, K.; Bakeas, E.; Philippopoulos, A.I. A 2-(2’-pyridyl)quinoline ruthenium(II) complex as an active catalyst for the transfer hydrogenation of ketones. Open Chem. 2016, 14, 308–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zacharopoulos, N.; Kolovou, E.; Peppas, A.; Koukoulakis, K.; Bakeas, E.; Schnakenburg, G.; Philippopoulos, A.I. Pyridyl based ruthenium(II) catalyst precursors and their dihydride analogues as the catalytically active species for the transfer hydrogenation of ketones. Polyhedron. 2018, 154, 27–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolovou, E.; Peppas, A.; Zacharopoulos, N.; Koukoulakis, K.; Bakeas, E.; Schnakenburg, G.; Philippopoulos, A.I. Facile synthesis of a 2-(2′-pyridyl)-4-(methylcarboxy)quinoline ruthenium (II) based catalyst precursor for transfer hydrogenation of aromatic ketones. Inorg. Chem. Commun. 2018, 92, 64–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kokkosi, A.; Garofallidou, E.; Zacharopoulos, N.; Tsoureas, N.; Diamanti, K.; Thomaidis, N.S.; Cheilari, A.; Machalia, C.; Emmanouilidou, E.; Philippopoulos, A.I. Ruthenium p-Cymene Complexes Incorporating Substituted Pyridine–Quinoline-Based Ligands: Synthesis, Characterization, and Cytotoxic Properties. Molecules 2024, 29, 3215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsolis, T.; Ypsilantis, K.; Kourtellaris, A.; Garoufis, A. Synthesis, characterization and interactions with 9-methylguanine of ruthenium(II) η6-arene complexes with aromatic diimines. Polyhedron 2018, 149, 45–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lalrempuia, R.; Kollipara, M.R. Reactivity studies of η6-arene ruthenium (II) dimers with polypyridyl ligands: isolation of mono, binuclear p-cymene ruthenium (II) complexes and bisterpyridine ruthenium (II) complexes. Polyhedron 2003, 22, 3155–3160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zucca, A.; Cordeschi, D.; Maidich, L.; Pilo, M.I.; Masolo, E.; Stoccoro, S.; Cinellu, M.; Galli, S. Rollover Cyclometalation with 2-(2′-Pyridyl)quinoline. Inorg. Chem. 2013, 52, 7717–7731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atwell, G.J.; Baguley, B.C.; Denny, W.A. Potential antitumor agents. 57. 2-Phenylquinoline-8-carboxamides as minimal DNA-intercalating antitumor agents with in vivo solid tumor activity. J. Med. Chem. 1989, 32, 396–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haginiwa, J.; Higuchi, Y.; Kawashima, T.; Goto, T. Reactions concerned in tertiary amine N-oxides. V. A new method for the preparation of asymmetric 2,2'-dipyridyl, 2,2'-pyridylquinoline and pyridylphenanthroline derivatives (author's transl). Yakugaku Zasshi. 1975, 95, 204–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Chen, F.; He, Y.-M.; Li, C.; Fan, Q.-H. Enantioselective synthesis of tunable chiral pyridine–aminophosphine ligands and their applications in asymmetric hydrogenation. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2019, 17, 50995105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iyoda, M.; Otsuka, H.; Sato, K.; Nisato, N.; Oda, M. Homocoupling of Aryl Halides Using Nickel(II) Complex and Zinc in the Presence of Et4NI. An Efficient Method for the Synthesis of Biaryls and Bipyridines. Bull. Chem. So.c Jpn. 1990, 63, 80–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verniest, G.; Wang, X.; De Kimpe, N.; Padwa, A. Heteroaryl Cross-Coupling as an Entry toward the Synthesis of Lavendamycin Analogues: A Model Study. J.Org. Chem. 2010, 75, 424–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez, R.; Ramón, D.J.; Yus, M. Transition-Metal-Free Indirect Friedländer Synthesis of Quinolines from Alcohols. J. Org. Chem. 2008, 73, 9778–9780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peppas, A. Synthesis and characterization of homoleptic Copper (I) complexes. Application in third generation solar cells (Gratzel type). Master's thesis, National and Kapodistrian University of Athens, Athens, Greece, 10 October 2015. Available online: https://pergamos.lib.uoa.gr/uoa/dl/object/1320032 (accessed on 10 October 2024).

- Pucci, D.; Crispini, A.; Ghedini, M.; Szerb, E.I.; La Deda, M. 2,2′-Biquinolines as test pilots for tuning the colour emission of luminescent mesomorphic silver(i) complexes. Dalton Trans. 2011, 40, 4614–4622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Milton, A.; Benial, F.; Ramakrishnan, V.; Murugesan, R. Spectrochimica Acta Part A: Molecular and Biomolecular Spectroscopy. Spectrochim. Acta Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2002, 58, 1703. [Google Scholar]

- Stanghellini, P.L.; Cognolato, L.; Bor, G.; Kettle, S.F.A. Identification of the IR frequencies of the interstitial carbon atom in some M6C (M = Fe, Ru) carbonyl clusters by 13 C-enrichment. J. Chem. Crystallogr. 1983, 13, 127–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peacock, A.; Melchart, M.; Deeth, R.; Habtemariam, A.; Parsons, S.; Sadler, P. Osmium(II) and Ruthenium(II) Arene Maltolato Complexes: Rapid Hydrolysis and Nucleobase Binding. Chem. Eur. J. 2007, 13, 2601–2613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bugarcic, T.; Habtemariam, A.; Stepankova, J.; Heringova, P.; Kasparkova, J.; Deeth, R.J.; Johnstone, R.D.L.; Prescimone, A.; Parkin, A.; Parsons, S.; Brabec, V.; Sadler, P.J. The Contrasting Chemistry and Cancer Cell Cytotoxicity of Bipyridine and Bipyridinediol Ruthenium(II) Arene Complexes. Inorg. Chem. 2008, 47, 11470–11486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández, R.; Melchart, M.; Habtemariam, A.; Parsons, S.; Sadler, P.J. Use of chelating ligands to tune the reactive site of half-sandwich ruthenium(II)-arene anticancer complexes. Chem. Eur. J. 2004, 10, 5173–5179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Q.; Li, P.; Lu, R.; Lu, R.; Qian, Q.; Lei, X.; Huang, S.; Liu, L.; Huang, C.; Su, W. Synthesis, X-ray Diffraction Study, and Cytotoxicity of a Cationic p-Cymene Ruthenium Chloro Complex Containing a Chelating Semicarbazone Ligand. Z. Anorg. Allg. Chem. 2013, 639, 943–946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vock, C.A.; Scolaro, C.; Phillips, A.D.; Scopelliti, R.; Sava, G.; Dyson, P.J. Synthesis, Characterization, and in Vitro Evaluation of Novel Ruthenium(II) η6-Arene Imidazole Complexes. J. Med. Chem. 2006, 49, 5552–5561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zacharopoulos, N. Synthesis and characterization of Ru complexes suitable for transfer hydrogenation and α,β alkylation reactions. Doctoral Dissertation, National and Kapodistrian University of Athens, Athens, Greece, 2023. Persistent URL: https://pergamos.lib.uoa.gr/uoa/dl/object/2973928. [Google Scholar]

- Erdem, A.; Kılınçarslan, R.; Şahin, Ç.; Dayan, O.; Özdemir, N. Synthesis, thermal, electrochemical and catalytic behavior toward transfer hydrogenation investigations of the half-sandwich RuII complexes with 2-(2′-quinolyl)benzimidazoles. J. Mol. Struct. 2020, 1220, 128556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mercan, D.; Çetinkaya, E.; Şahin, E. Ru(II)–arene complexes with N-substituted 3,4-dihydroquinazoline ligands and catalytic activity for transfer hydrogenation reaction. Inorg. Chim. Acta 2013, 400, 74–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Yang, Q.; Fu, H.-Y.; Chen, H.; Yuan, M.-L.; Li, R.-X. Ru–η6 -benzene–phosphine complex-catalyzed transfer hydrogenation of ketones. Appl. Organometal. Chem. 2011, 25, 626–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Standfest-Hauser, C.; Slugovc, C.; Mereiter, K.; et al. Hydrogen-transfer catalyzed by half-sandwich Ru(ii) aminophosphine complexes. J. Chem. Soc. Dalton Trans. 2001, 20, 2989–2995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Araujo, M.P.; de Figueired, A.T.; Bogado, A.L.; et al. Ruthenium Phosphine/Diimine Complexes: Syntheses, Characterization, Reactivity with Carbon Monoxide, and Catalytic Hydrogenation of Ketones. Organometallics 2005, 24, 6159–6168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çalık, H.S.; Ispir, E.; Karabuga, Ş.; Aslantas, M. Ruthenium (II) complexes of NO ligands: Synthesis, characterization and application in transfer hydrogenation of carbonyl compounds. J. Organomet Chem. 2016, 801, 122–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dritsopoulos, A.; Zacharopoulos, N.; Peyret, A.-E.; Karampella, E.; Tsoureas, N.; Cheilari, A.; Machalia, C.; Emmanouilidou, E.; Andreopoulou, A.K.; Kallitsis, J.K.; et al. Ruthenium-p-Cymene Complexes Incorporating Substituted Pyridine–Quinoline Ligands with –Br (Br-Qpy) and –Phenoxy (OH-Ph-Qpy) Groups for Cytotoxicity and Catalytic Transfer Hydrogenation Studies: Synthesis and Characterization. Chemistry 2024, 6, 773–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bäckvall, J.E. Transition metal hydrides as active intermediates in hydrogen transfer reactions. J. Organomet. Chem. 2002, 652, 105–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joseph, M.C.; Swarts, A.J.; Mapolie, S.F. Cationic half-sandwich ruthenium (II) complexes ligated by pyridyl-triazole ligands: Transfer hydrogenation and mechanistic studies. Polyhedron 2022, 212, 115579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, M.A.; Huang, T.N.; Matheson, T.W.; Smith, K. Inorganic Synthesis; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheldrick, G.M. SHELXT—Integrated space-group and crystal structure determination. Acta Cryst. 2015, A71, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheldrick, G.M. Crystal structure refinement with SHELXL. Acta Crystallorg. C. Struct Chem. 2015, 71, 3–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

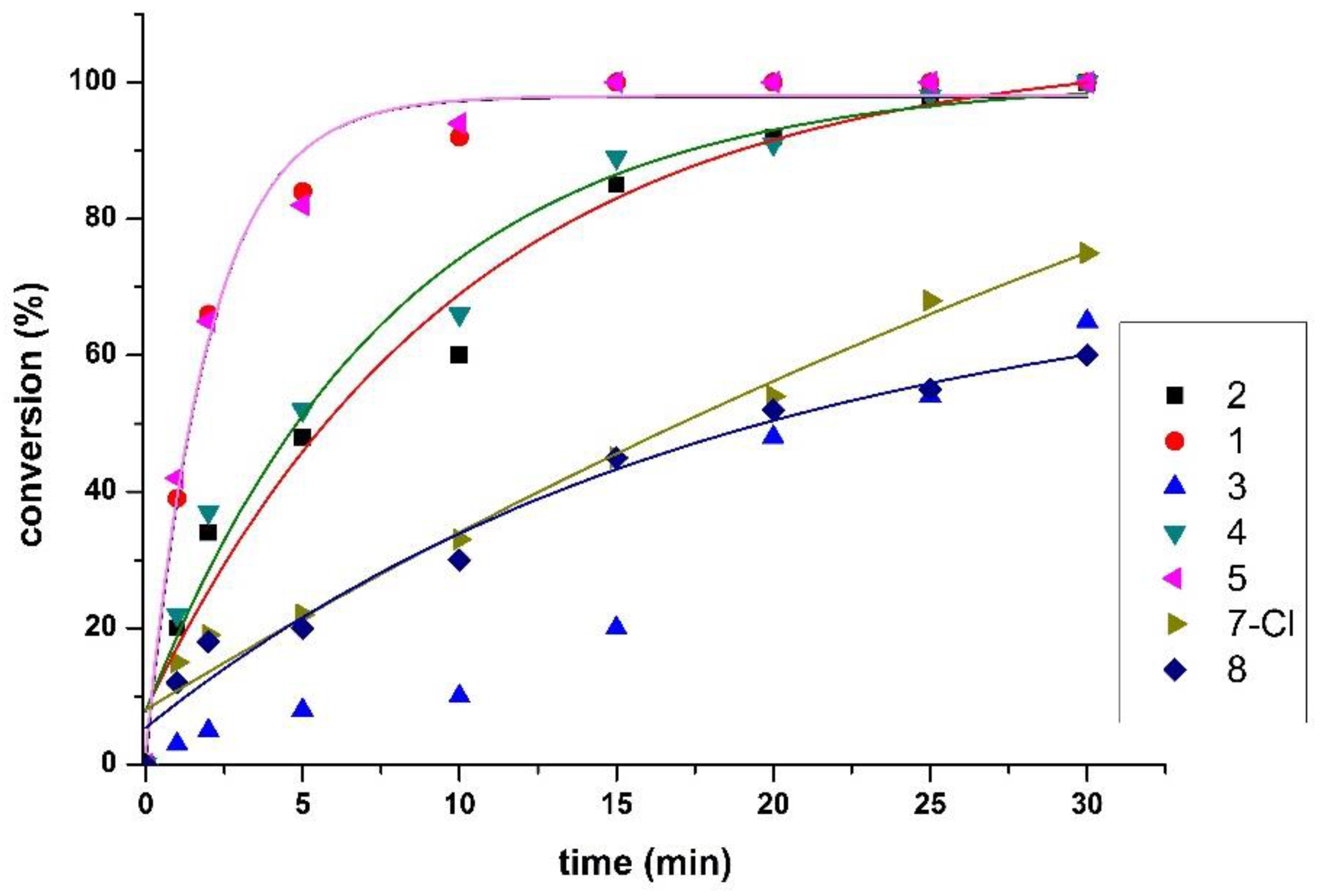

| Entry | Complex* | Time (min) | Conversion (%)a | ΤOΝb | TOF (h–1)c |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1 | 15 | 100 | 400 | 1600 |

| 2 | 2 | 15 | 85 | – | – |

| 3 | 2 | 30 | 100 | 400 | 800 |

| 4 | 3 | 15 | 20 | – | – |

| 5 | 3 | 60 | 100 | 400 | 400 |

| 6 | 4 | 15 | 90 | – | – |

| 7 | 4 | 30 | 100 | 400 | 800 |

| 8 | 5 | 15 | 100 | 400 | 1600 |

| 9 | Ru-pqcame | 60 | 38 | – | – |

| 10 | Ru-pqcame | 180 | 95 | 380 | 127 |

| 11 | 6 | 180 | 100 | 400 | 133 |

| 12 | 7-Cl | 60 | 95 | 380 | 380 |

| 13 | 8 | 60 | 90 | 360 | 360 |

| 14 | 9 | 60 | 30 | – | – |

| 15 | 9 | 180 | 90 | 360 | 120 |

| 16 | 10 | 15 | 90 | 360 | 1440 |

| 17 | 11 | 60 | 90 | 360 | 360 |

| Entry | Substrate* | Complex | Time (min) | Conversion (%)a | TONb | TOF (h–1)c |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

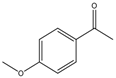

| 1 |  |

1 | 15 | 99 | 396 | 1584 |

| 2 | 2 | 30 | 95 | 380 | 760 | |

| 3 | 3 | 60 | 70 | 280 | 280 | |

| 4 | 4 | 30 | 99 | 392 | 792 | |

| 5 | 5 | 15 | 95 | 380 | 1520 | |

| 6 | Ru-pqcame | 180 | 85 | 340 | 113 | |

| 7 | 6 | 180 | 87 | 348 | 116 | |

| 8 | 7-Cl | 60 | 92 | 368 | 388 | |

| 9 | 8 | 60 | 82 | 328 | 328 | |

| 10 | 9 | 180 | 85 | 340 | 113 | |

| 11 | 10 | 60 | 88 | 352 | 352 | |

| 12 | 11 | 60 | 83 | 332 | 332 | |

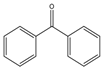

| 13 |  |

1 | 15 | 99 | 396 | 1584 |

| 14 | 2 | 30 | 98 | 392 | 784 | |

| 15 | 3 | 60 | 90 | 360 | 360 | |

| 16 | 4 | 30 | 98 | 392 | 784 | |

| 17 | 5 | 15 | 98 | 392 | 1568 | |

| 18 | Ru-pqcame | 180 | 95 | 380 | 127 | |

| 19 | 6 | 180 | 98 | 392 | 131 | |

| 20 | 7-Cl | 60 | 95 | 380 | 380 | |

| 21 | 8 | 60 | 90 | 360 | 360 | |

| 22 | 9 | 180 | 90 | 360 | 120 | |

| 23 | 10 | 60 | 97 | 388 | 388 | |

| 24 | 11 | 60 | 82 | 328 | 328 | |

| 25 |  |

1 | 30 | 66 | 264 | 528 |

| 26 | 2 | 30 | 72 | 288 | 576 | |

| 27 | 3 | 60 | 55 | 220 | 220 | |

| 28 | 4 | 30 | 75 | 300 | 600 | |

| 29 | 5 | 30 | 72 | 288 | 676 | |

| 30 | Ru-pqcame | 180 | 72 | 288 | 96 | |

| 31 | 6 | 180 | 88 | 336 | 117 | |

| 32 | 7-Cl | 60 | 65 | 260 | 260 | |

| 33 | 8 | 60 | 66 | 264 | 264 | |

| 34 | 9 | 180 | 60 | 240 | 80 | |

| 35 | 10 | 60 | 73 | 292 | 292 | |

| 36 | 11 | 60 | 66 | 264 | 264 | |

| 37 |  |

1 | 30 | 89 | 356 | 712 |

| 38 | 2 | 30 | 85 | 340 | 680 | |

| 39 | 3 | 60 | 65 | 260 | 260 | |

| 40 | 4 | 30 | 96 | 386 | 772 | |

| 41 | 5 | 30 | 96 | 384 | 768 | |

| 42 | Ru-pqcame | 180 | 78 | 312 | 104 | |

| 43 | 6 | 180 | 94 | 376 | 126 | |

| 44 | 7-Cl | 60 | 75 | 300 | 300 | |

| 45 | 8 | 60 | 70 | 380 | 280 | |

| 46 | 9 | 180 | 75 | 300 | 100 | |

| 47 | 10 | 60 | 79 | 316 | 316 | |

| 48 | 11 | 60 | 78 | 312 | 312 | |

| 49 |  |

1 | 60 | 99 | 396 | 396 |

| 50 | 2 | 60 | 95 | 380 | 380 | |

| 51 | 3 | 60 | 80 | 320 | 320 | |

| 52 | 4 | 60 | 90 | 360 | 360 | |

| 53 | 5 | 60 | 96 | 364 | 364 | |

| 54 | Ru-pqcame | 180 | 85 | 340 | 113 | |

| 55 | 6 | 180 | 82 | 328 | 109 | |

| 56 | 7-Cl | 60 | 96 | 384 | 384 | |

| 57 | 8 | 60 | 88 | 352 | 352 | |

| 58 | 9 | 180 | 82 | 328 | 109 | |

| 59 | 10 | 60 | 88 | 352 | 352 | |

| 60 | 11 | 60 | 99 | 396 | 396 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).