1. Introduction

Organic chemistry has significantly shifted toward sustainable and environmentally friendly approaches, collectively known as green chemistry. These principles aim to minimize or eliminate the use and generation of hazardous substances throughout the design, manufacturing, and application of chemical processes [

1]. Microwave-assisted (MW) synthesis has emerged as an effective strategy for implementing green chemistry, offering shorter reaction times and reduced energy consumption compared to conventional heating methods [

2]. Within this context, the synthesis of novel hydroxychloroquine (HCQ) derivatives has gained increasing attention due to HCQ’s notable therapeutic applications [

3]. These advancements align with green chemistry principles, addressing the growing demand for new pharmaceuticals and promoting sustainable methodologies for drug synthesis.

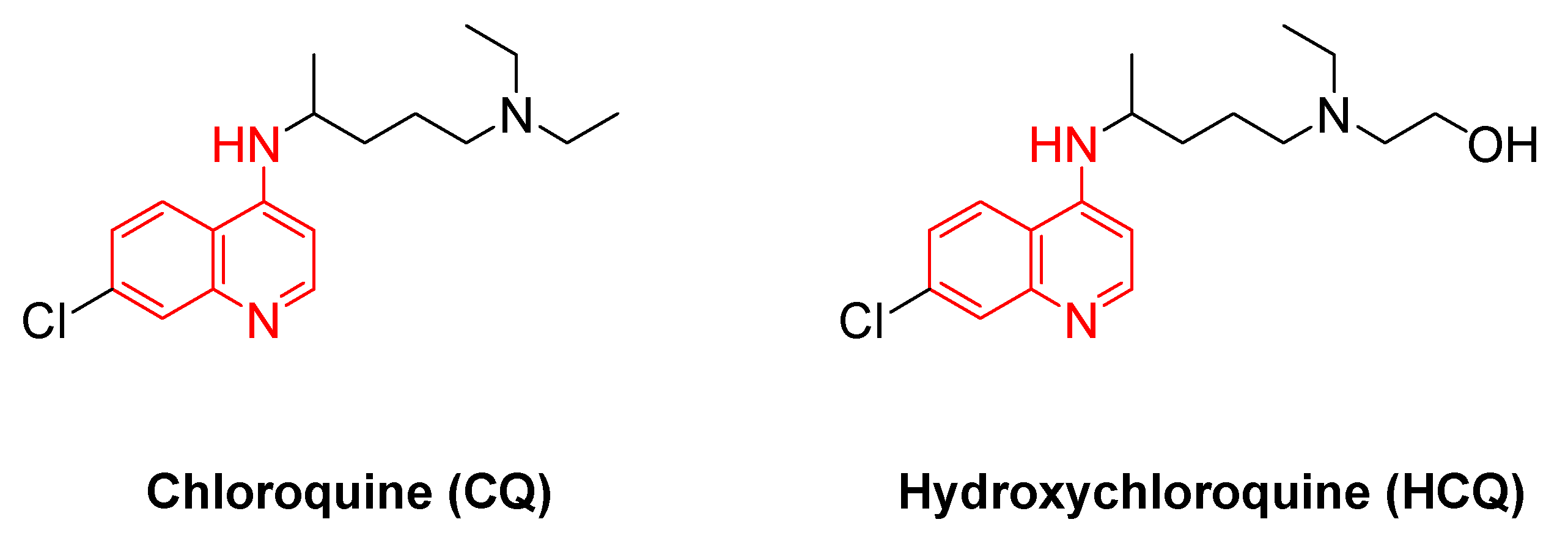

The quinoline scaffold is considered to be the main core of the synthesis of HCQ and its derivatives (

Figure 1). Quinoline was first isolated from coal tar by Runge (1834) [

4]. The quinoline ring system appeared in various natural products, particularly in alkaloids as reported by Gerhardt (1842) [

5]. It is intensively used to plan many synthetic compounds with pharmacological effects [

6]. Quinolines were employed as the most significant antimalarial drugs ever known. In the past century, the intensive use of chloroquine (CQ), the most well-known drug within this family, created a strong optimism for eliminating malaria (

Figure 1) [

7]. Quinoline is an ideal starting point for medicinal chemistry efforts. 4-aminoquinoline derivatives were first synthesized in 1934 by Andersag [

8]. The CQ is recommended as an effective treatment for almost all malarial strains [

9]. Clinical trials, that took place have provided measurable evidence of the effects of CQ as a potent novel drug for fighting tumors [

10]. In the COVID-19 pandemic, CQ has shown significant inhibition effects of the growth of coronavirus, and several clinical studies have demonstrated the positive impacts of CQ on COVID-19 patients. These trials have exposed that CQ reveals significant value in clinical results and viral prohibition, beating the control groups [

11].

HCQ is a derivative of 4-aminoquinolines (

Figure 1), that was synthesized in 1946 and found as a safer substitute for chloroquine in 1955 [

12]. The replacing of an ethyl group in CQ with a hydroxyethyl group was taken place to create HCQ, which resulted in a higher capacity of spreading and lower toxicity in humans [

13]. HCQ has been recorded as a potent antimalarial drug [

14]. Besides its antiparasitic activity, HCQ has shown a wide range of acceptable clinical properties including immunomodulatory and anti-inflammatory activities, these characteristics have encouraged researchers to examine its potent in treating many autoimmune diseases, such as rheumatoid arthritis and lupus erythematosus [

15]. During the recent COVID-19 pandemic, the researchers discussed using HCQ for treating coronavirus patients [

16]. The exceptional pharmacological profile of both HCQ and CQ has promoted researchers to synthesize novel 4-aminoquinolines derivatives to increase their efficiency, minimize side effects, and expand their therapeutic applications [

17,

18,

19]. Zhao et.al. have recently reported the synthesis of some 4-aminoquinolines using conventional reflux methods in aromatic solvents for several hours [

20].

The purpose of this study is to synthesize and emphasize the importance and the impact of 4-aminoquinolines derivatives through the utilization of microwave-assisted reactions, without requiring reaction solvent or needing of further purification method of products, applying the principles of green chemistry.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Chemicals and Materials

All the starting materials and solvents were purchased from Scharlau, Fluka and Sigma-Aldrich. They were used without further purification. Thin Layer Chromatography (TLC) silica gel sheets (F254; 20 x 20 cm, Merk aluminum, Germany) were used to test the completion of the reactions. A UV-lamp of 354 nm was used to visualize the TLC plates. The spectra were recorded at room temperature using (AVANCE-III 400MHz), FT-NMR NanoBay spectrometer (Bruker, Switzerland). All spectra were made in Dimethyl Sulfoxide (DMSO-d6) with Tetramethylsilane (Me)4Si (TMS) as an internal standard. 13C-NMR spectra were recorded at 101.00 MHz, calibrated at 39.52 ppm, while 1H-NMR spectra were measured at 400.00 MHz instrument and calibrated at 2.5 ppm. The Fourier-Transform InfraRed spectra (FTIR spectra) were recorded in neat form using a Bruker Vertex 70-FT-IR Spectrometer (Bruker, Switzerland) at room temperature in the 4000-400 cm-1 region. Melting points (m.p) were obtained on Stuart Scientific Melting Apparatus (Stuart, UK), and were reported in °C. The High-resolution mass spectroscopy was achieved using a Bruker Daltonik (Bremen, Germany) Impact II ESI-Q-TOF System equipped with Bruker Dalotonik (Bremen, Germany). It was used for screening compounds of interest, using direct injection. Biotage® Initiator+, Fourth Generation Microwave Synthesizer was used to carry out all MW-assisted reactions.

2.2. Synthesis

General Procedure (GP)

Substituted 2-aminobenzonitrile (1.0 eq., 1a-e) was mixed in neat form with an excess amount of the ketones 2, 3, and 6a-d. Anhydrous ZnCl2 (1.0 eq.) was added to the mixture in a sealed tube. The tube was inserted into the MW instrument and heated for 90 min. at 90-140 ºC as indicated. The mixture was washed with dichloromethane several times to remove the rest of the starting materials and possible side products. Zn-bound product was isolated and dried for the next step. The Zn-bound solid was dissolved in isopropanol as indicated and treated with NaOH (40%) solution to obtain the Zn-free product in highly pure form as solid products in good yields as indicated. (Synthesis, structure and Spectral data, All spectral data and spectra are listed in the Sup. Info.)

2.3. Antibacterial Antifungal Determination Method

2.3.1. Microorganisims

The microorganisms used in this study are gram-negative bacteria, gram-positive bacteria, and yeast obtained from ATCC (Bacillus spizizenii ATCC 6633, Staphylococcus aureus ATCC 6538, methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) ATCC 33591, Streptococcus pyogenes ATCC 19615, Escherichia coli ATCC 8739, Proteus mirabilis ATCC 12453, Klebsiella pneumoniae ATCC 13883, Salmonella typhimurium ATCC 14028, and Candida albicans ATCC 10231) and from clinical laboratories (MRSA, Streptococcus pyogenes, Klebsiella pneumonia, Salmonella typhimurium, and Candida albicans). The bacterial strains and yeast were grown at 37°C and maintained on Nutrient Agar.

2.3.2. Well Diffusion Method

Compounds listed in

Table S1 (Sup. Info.) were tested in vitro for their antimicrobial activity against gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria by Kirby-Bauer method [

21]. The media used for bacteria was Mueller-Hinton agar. Bacterial colonies were prepared in 5 mL Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS) at 0.5 McFarland standard (1×108 CFU/mL), then 100 µL of bacterial culture were inoculated on fresh Mueller-Hinton agar using a cotton swab. Next, wells were filled with 50 µL of each tested compound at the concentration of 2 mM, suspended previously in DMSO 5%. Imipenem and Fluconazole have been used as positive antibacterial and antifungal controls, respectively, and DMSO 5% as a negative control. The inoculated plated with different bacteria were incubated at 37°C for 18 hours. Antimicrobial activity was evaluated by measuring the inhibition zone against the tested organism. All tests were held as triplicates.

2.3.3. Minimum Inhibitory Concentration (MIC)

A broth microdilution method was employed to determine the minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) [

21]. The microorganisms used in this test are (MRSA ATCC 33591, S. aureus ATCC 6538, S. pyogenes ATCC 19615, MRSA Clinical). Bacterial suspensions were prepared to 0.5 McFarland standard. A serial doubling dilution of the compounds was prepared in 96-well microtiter plate [

22]. Mueller-Hinton broth was used as a diluent. The concentrations were 2 mM for the compounds recorded. Two-fold serial dilution was done in this experiment to get the concentration range of the derived compounds (1 – 0.00195). For every experiment, a sterility check (medium), negative control (medium), and positive control (medium and inoculum) were included, 96-micro well plates were prepared by dispensing 100 µL of an appropriate medium into each well, then 100 µL of the tested compounds were added into the first well and diluted to well ten, next, 100 of bacterial inoculums were added into each well [

23]. The contents of each well were mixed thoroughly with a multi-channel micropipette, and the micro-well plates were covered with a sterile sealer and incubated at 37 ℃ for 24 h. The absorbances of the wells were read at 570 nm using a microtiter plate reader.

2.3.4. Minimum Bactericidal Concentration (MBC)

After MIC determination of the compound, 10 µL from all the wells that showed no visible bacterial growth (no turbidity) were seeded on Mueller-Hinton agar plates and incubated for 24 h at 37 ℃. When 99.9% of the bacterial population is killed at the lowest concentration of an antimicrobial agent, it is termed as MBC endpoint. This assay was done by observing pre and post-incubated agar plates for the presence or absence of bacteria [

23]

2.4. Molecular Docking Methodology

2.4.1. Software Packages

BIOVIA Discovery Studio® 4.1 (DS 4.1) implemented with Standalone Application,

https://www.3dsbiovia.com for ligand docking protocols.

2.4.2. Ligand Preparation and Molecular DockingProtein Preparation

The receptor structures used in this study were retrieved from the Protein Data Bank (PDB). Two proteins were targeted: the MRSA-Penicillin Binding Protein 2a (PBP2a) (PDB code: 4DKI, resolution = 2.9 Å) and the MRSA integrase enzyme (PDB code: 3NKH, resolution = 2.5 Å). Both proteins were prepared by adding hydrogens and ensuring all-atom valencies were satisfied to enable accurate docking simulations. The proteins were standardized for docking by using the Define Site from PDB Site Records protocol in Discovery Studio 4.1 (BIOVIA), which identified the binding pockets based on the PDB site records.

Ligand Preparation

The ligands were prepared using the Prepare Ligands protocol in Discovery Studio 4.1. This protocol standardized the charges for common groups, represented the ligands in Kekulé form, and fixed their ionization states at physiological pH (pH=7) to ensure consistency in ligand representation. The prepared ligands were then docked into the defined binding pockets of the two proteins.

Binding Site Definition

The binding sites for the receptors were defined using the following parameters:

The binding site of MRSA-Penicillin Binding Protein 2a (PBP2a) was centered at coordinates X = 27.060575, Y = 25.812963, and Z = 80.608915, with dimensions of 2.034884 Å in length, 1.547685 Å in width, and 0.838396 Å in height. The orientation of the binding site was described by the following three vectors: (-0.187688, -0.291828, 2.005084), (-0.910866, 1.247547, 0.096310), and (-0.673394, -0.481387, -0.133097).

The binding site of the MRSA integrase enzyme was centered at coordinates X = 4.660522, Y = 7.027135, and Z = 39.349048, with dimensions of 3.368529 Å in length, 0.990695 Å in width, and 0.692630 Å in height. The orientation of the binding site was described by the following three vectors: (-0.367956, -1.454230, 3.016092), (-0.980396, -0.037196, -0.137540), and (0.064797, -0.624219, -0.293066).

2.5. Docking Procedure

Docking experiments were conducted using the LigandFit Docking Protocol in Discovery Studio 4.1 (BIOVIA). Ligands were docked into the predefined binding sites using a multi-stage process. First, the site was partitioned by matching the ligand and site shapes. Then, the selected ligand conformation was positioned within the binding site. A rigid-body energy minimization step followed, utilizing the DockScore energy function to refine the ligand pose within the binding site. Finally, a pose-saving algorithm was applied to compare the candidate pose with previously stored poses, ensuring that redundant (similar) poses were excluded from further analysis.

The Monte Carlo trials were employed during the docking process to explore the conformational and positional space of the ligands within the binding site. This stochastic method allowed for efficient sampling of ligand poses and ensured a thorough exploration of the binding site. The Deriding energy grid was used for energy calculations during the docking process, providing accurate results based on the molecular mechanics force field. Additionally, a RMS threshold of 2 was applied for pose convergence to ensure that only high-confidence poses were considered for analysis.

2.5.1. Scoring and Evaluation

The docked ligand poses were evaluated using a variety of scoring functions integrated into the LigandFit protocol. These included CDOCKER Scores, which utilize the CHARMm forcefield for physics-based evaluations,[

24]. and empirical scoring functions such as LigScore1 and LigScore2 [

25]. The PLP1 and PLP2 scoring functions[

26]. were used for their piecewise linear potential approximations, while the Jain scoring function[

27]. evaluated hydrophobic, polar, and steric interactions. Knowledge-based scoring functions, including PMFand PMF04, were also applied,[

28]. using statistical potentials derived from the Protein Data Bank (PDB).

2.5.2. Ligand Pose Analysis

Following the docking step, the Analyze Ligand Poses protocol in Discovery Studio 4.1 was employed to calculate and enumerate the non-bond receptor-ligand interactions for the ligand poses generated in the docking run. This protocol identifies various interaction types, including favorable, unfavorable, charge, halogen, hydrophobic, and hydrogen bond interactions.

Table S2 (Sup. Info.) provided a summary of these interactions.

3. Results and Discussion

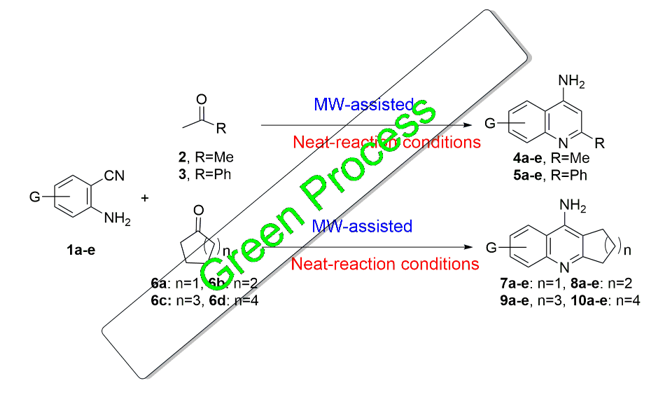

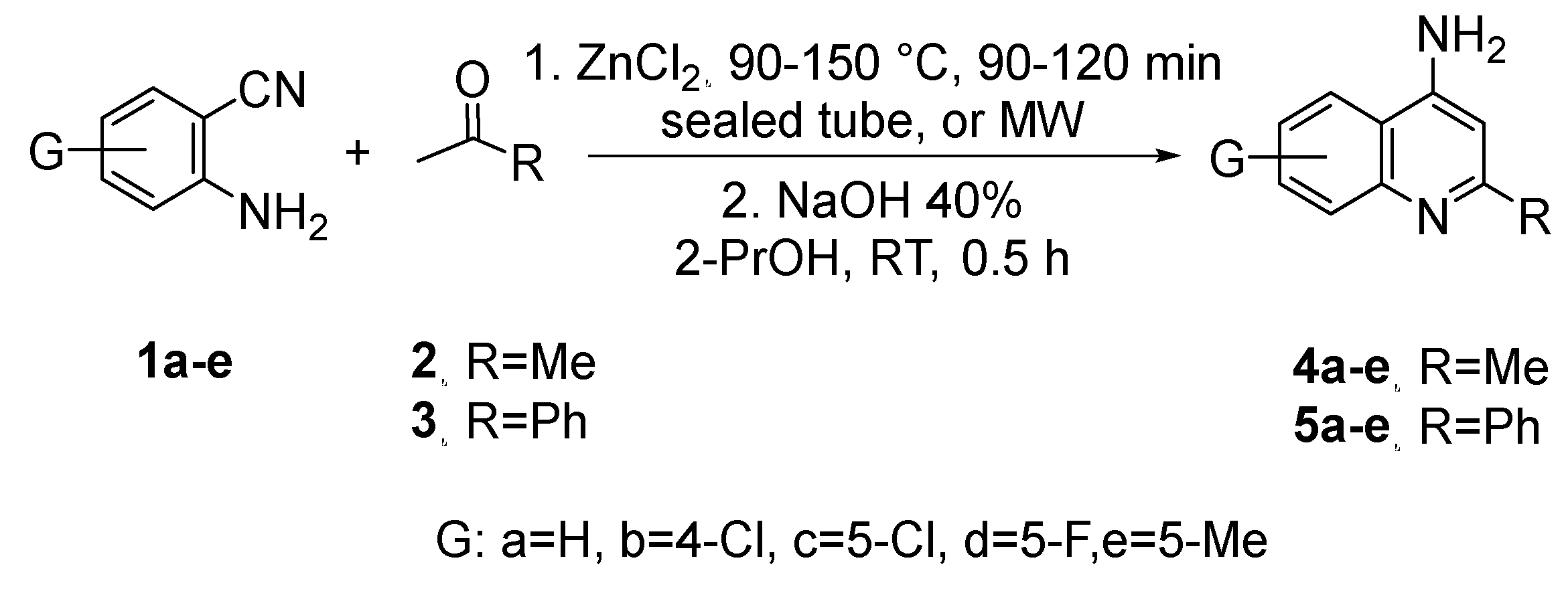

3.1. Synthesis and Characterization

This synthesis was carried out using different substituted 2-aminobenzonitriles

1a-e on the 4-, and 5-positions, to achieve different quinoline derivatives. As the cyclization was achieved with methyl ketones

2 and

3, which have -hydrogen, the 2-substituted quinoline-4-amine derivatives

4a-e and

5a-e were obtained in good to excellent yields of 70-95% (

Scheme 1).

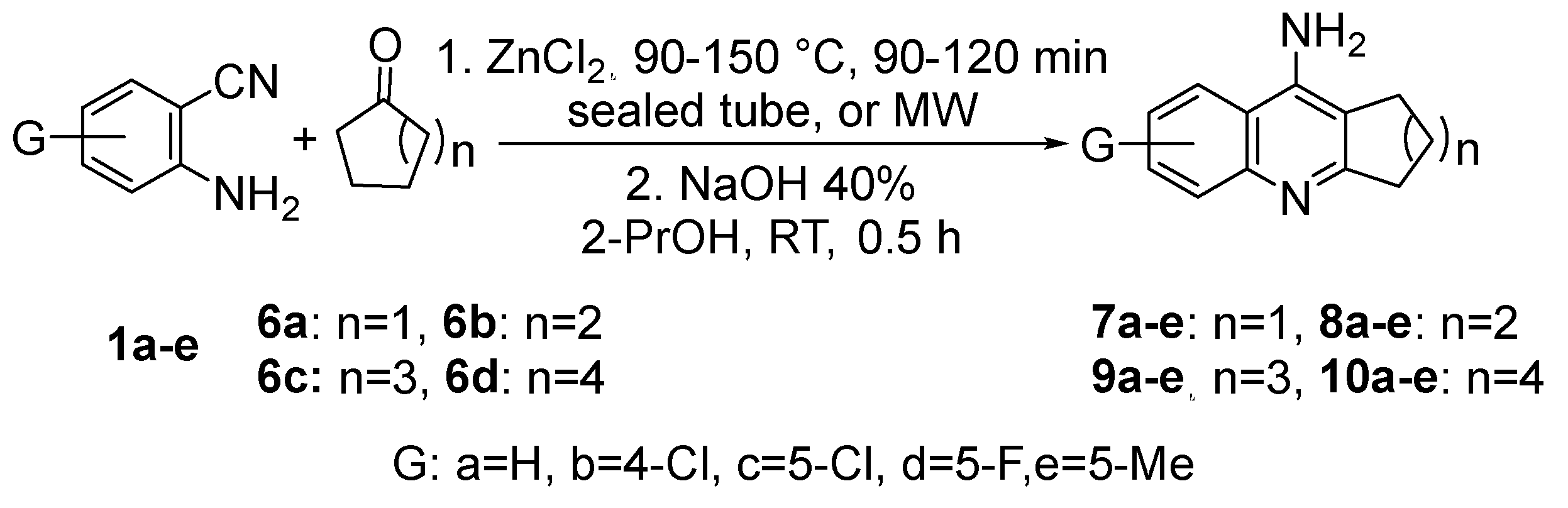

The reaction of 2-aminobenzonitriles

1a-e with symmetrical cyclic ketones

6a-d and ZnCl

2 gave tetrahydroacridines

8a-e, and cycloalka[b]quinolines

7a-e,

9a-e, and

10a-e in good to excellent yields of 65-90% (

Scheme 2).

Green synthesis principles guided the development of these promising small molecules. The reaction of 2-aminobenzonitriles 1a-e with ketones bearing α-hydrogens was performed under solvent-free, MW-assisted conditions using ZnI₂ as a catalyst. To improve cost-effectiveness, the reaction was also conducted with the more affordable and safer anhydrous ZnCl₂, yielding comparable results. Due to the volume limitations of microwave vessels, the reactions were successfully scaled up in sealed tubes heated at 90–150 °C for 1–2 h, achieving similar yields to those obtained under microwave conditions.

The Zn-bound products were washed three times with dichloromethane (DCM) to remove excess starting materials and any side products, taking advantage of the low solubility of the products in DCM. The purity of the Zn-bound products was supported using NMR analysis. In the second step, the Zn-bound solids were dissolved in isopropanol and treated with 40% NaOH solution at RT for 30 min, yielding the Zn-free final products in highly pure form, as confirmed by NMR and HRMS (see Supplementary Information). No further purification methods were required.

FT-IR spectra of all products were recorded to observe two to three weak broad peaks in the region of 3500-3300 cm-1 belonging to the NH2 stretching. At the same time, all compounds showed strong to medium peaks between 1650-1450 cm-1 proving the C=N and C=C stretching bands of the quinoline rings (see Supplementary Information).

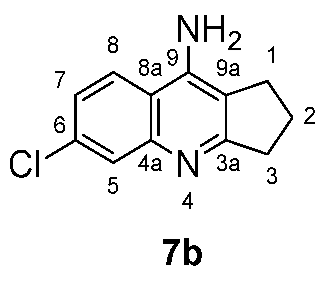

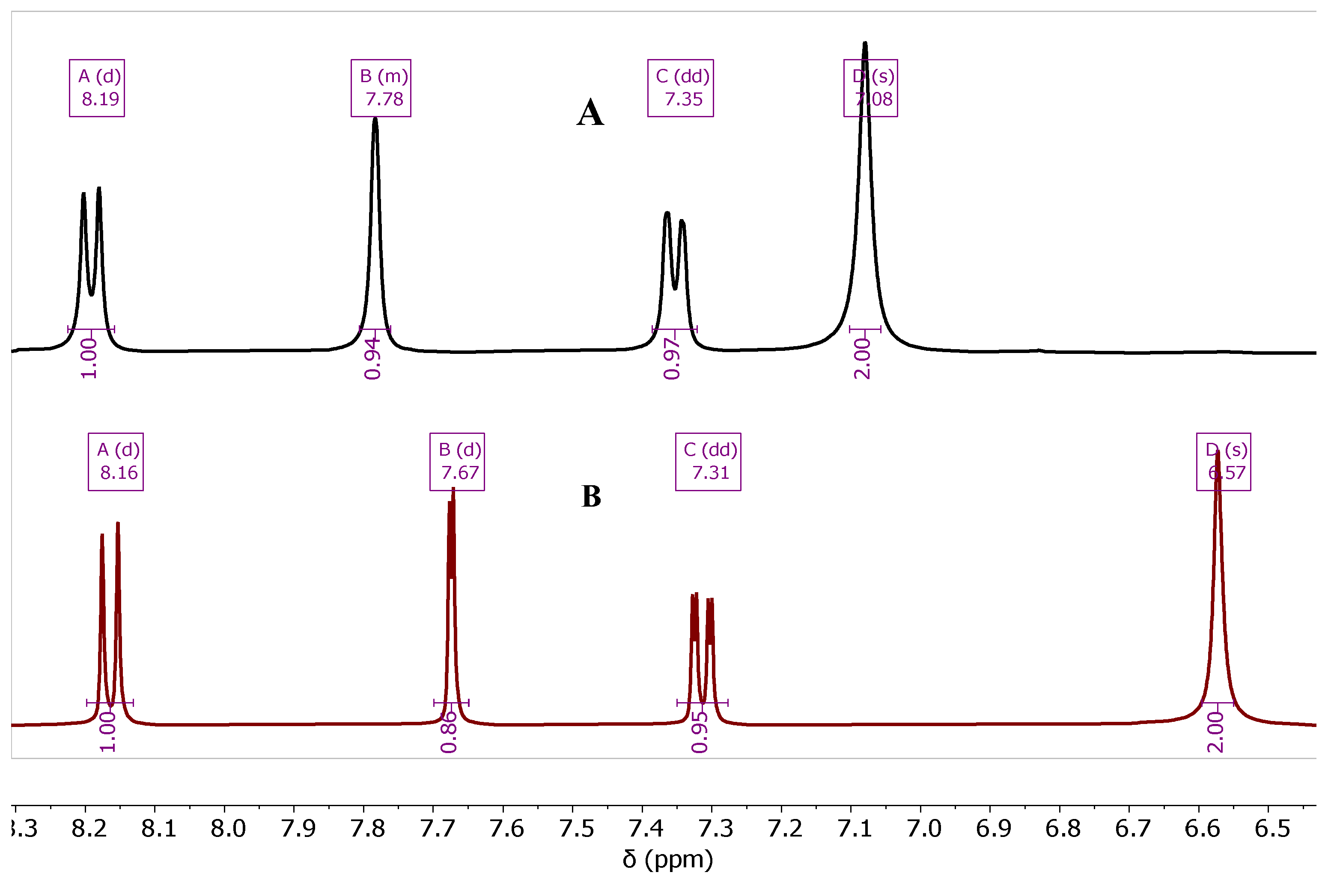

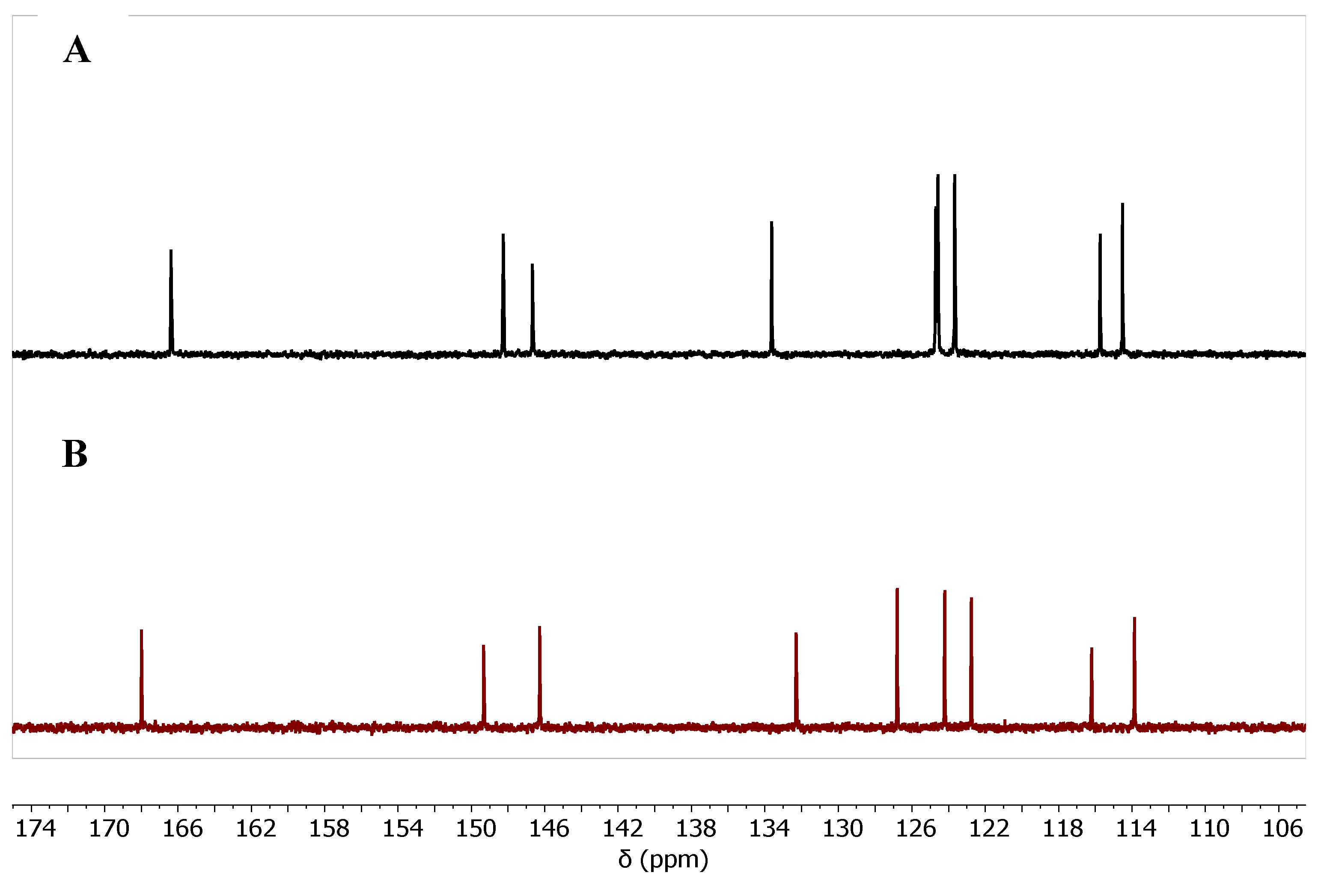

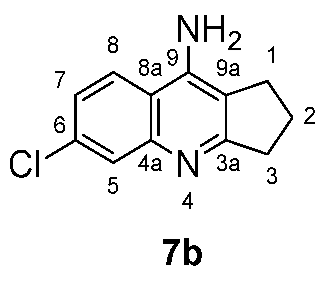

The presence of Zn

2+ ion combined with the product after the MW-step showed an effect on the shape and the chemical shift of the

1H-and

13C-NMR peaks especially the peak of NH

2 protons. The protons of the aromatic ring as same as the NH

2 ones appeared broader with slightly higher chemical shift in the presence of Zn ion (

Figure 2a), and sometimes the C-H peaks lost their multiplicity, as compared with the Zn-free product after the treatment of the Zn-bound product with the NaOH (40%) solution,

Figure 2b, of compound

7b. The chemical shift values of the

1H-NMR of compound

7b are summarized in

Table 1.

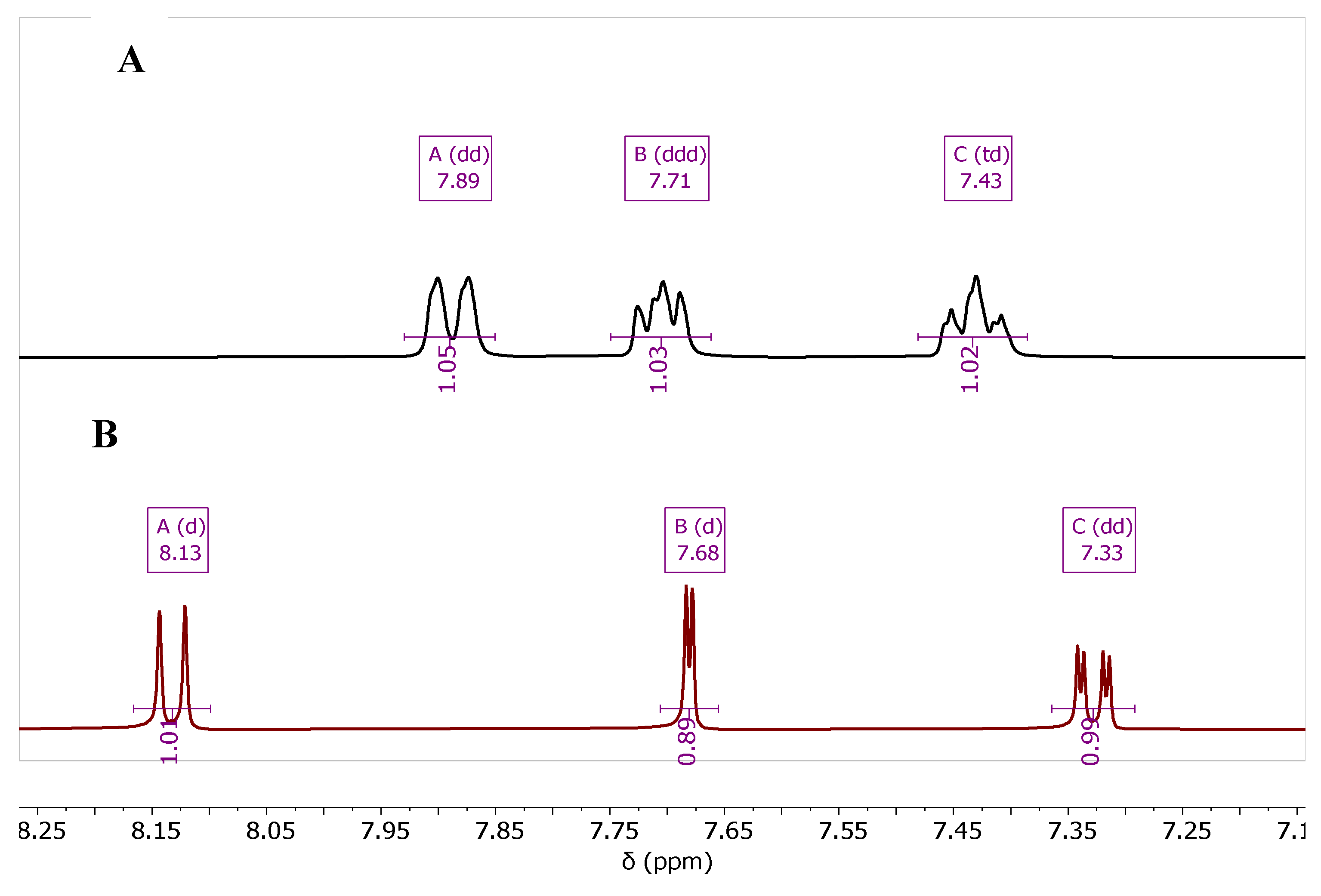

In the aromatic region of the

13C-NMR, nine peaks were observed for the quinoline moiety, e.g., compound

7b,

Figure 3. The Zn-free product shows a slight difference in the chemical shift compared with the Zn-bound one. The chemical shifts of the nine aromatic carbons are summarized in

Table 2.

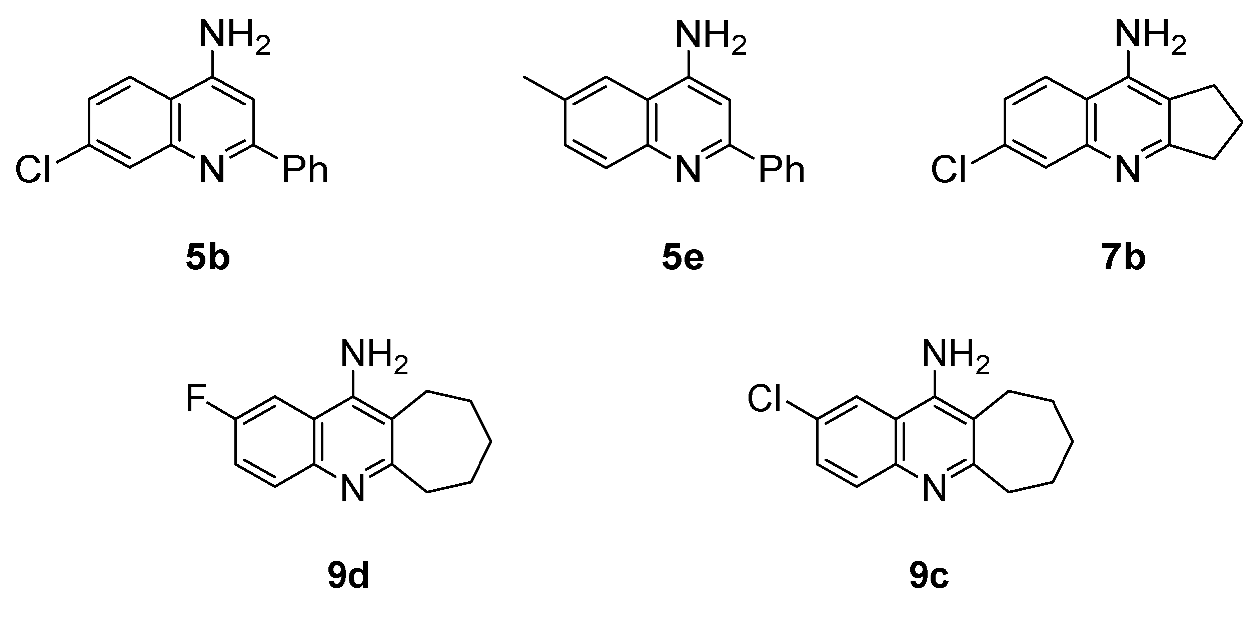

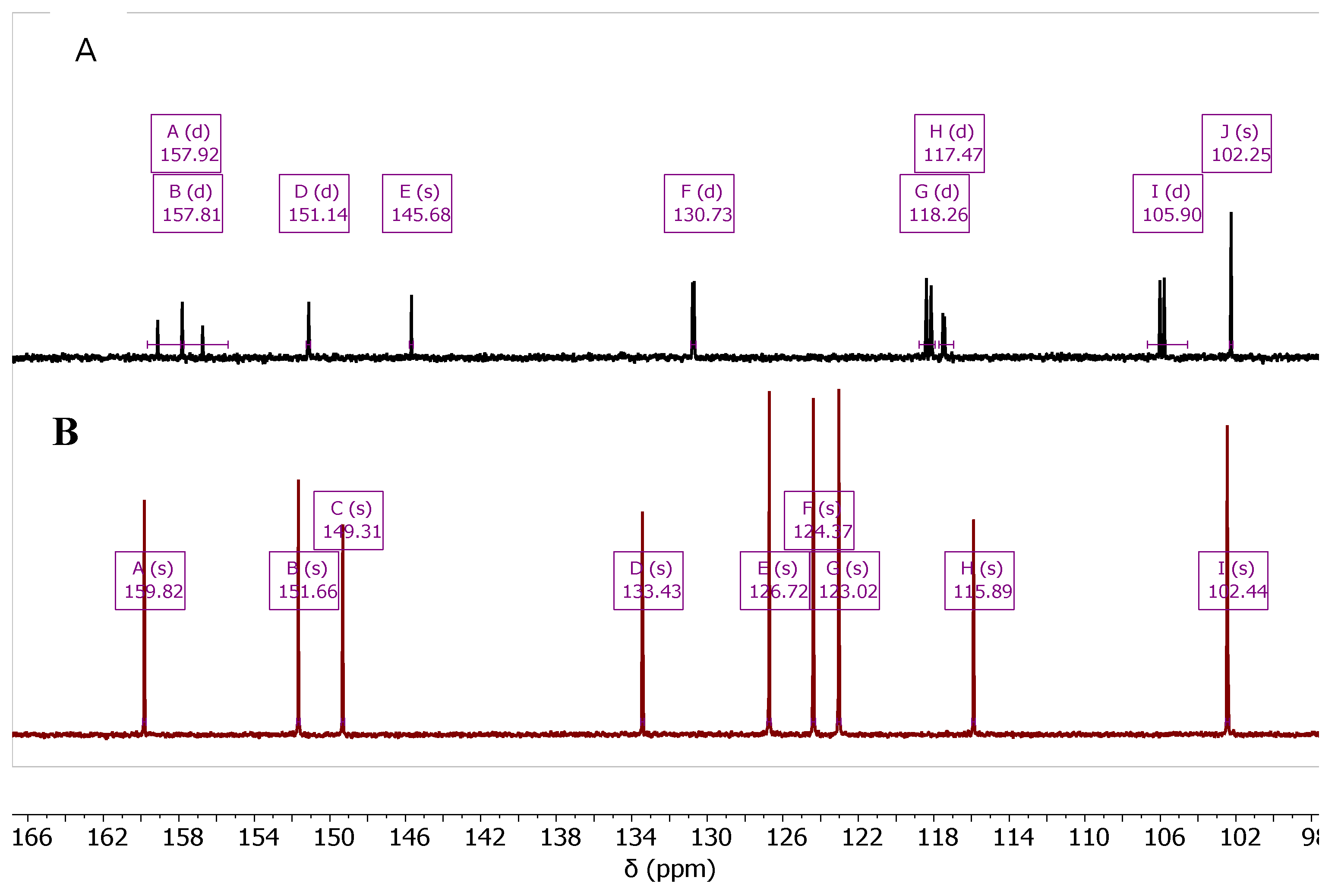

The synthesis of the fluorinated quinoline derivatives 4d, 5d, and 7d-10d was conducted using the same chemical procedure except the reaction temperature was applied to 90 ºC, which is around the melting point of the starting material, 2-amino-5-fluorobenzonitrile (1d).

As the reaction was carried out over this temperature, decomposition of

1d in the reaction tube was observed. The fluorinated products

4d,

5d, and

7d-

10d showed characteristic

1H- and

13C-NMR, according to the coupling behavior of

19F-atom with both

1H and

13C. The effect of the

19F-

1H (

Figure 4) and

19F-

13C (

Figure 5) coupling is represented for compounds

4b and

4d.

High-resolution mass (HRMS) of all compounds were recorded to prove the purity of final products, in order to carry out the biological studies.

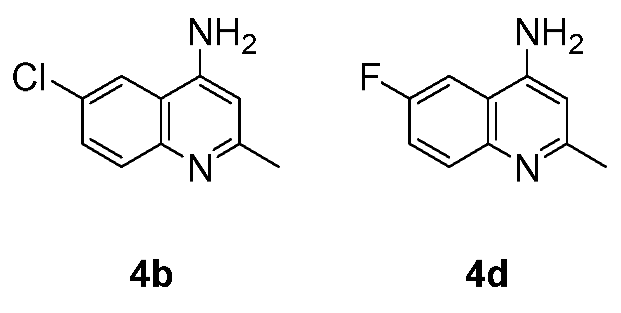

3.2. Antibacterial and Antifungal Activity

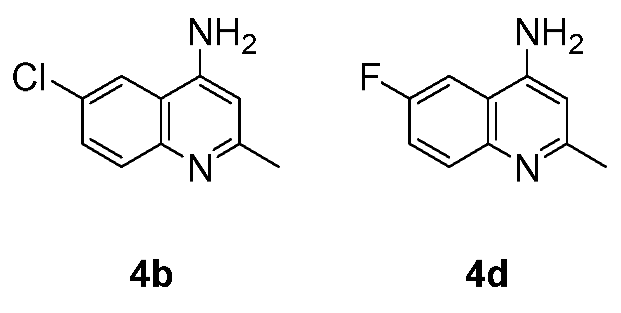

The new synthesized compounds

4-10 were evaluated adopting the well diffusion method, for their antibacterial activity using many gram-negative and gram-positive bacterial strains [

21]. Also the compounds were tested for their antifungal activity using

Candida albicans. Only four compounds;

5b,

5e,

7b, and

9d were found to exhibit antibacterial activity, and no compound was found to have any antifungal effect. Compounds;

5b,

5e, and

7b were found to have a modest inhibition effect against methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (

MRSA), with

7b being the best (

Table 3).

Compound

9d exhibited good activity against three bacteria strains;

Staphylococcus aureus,

Streptococcus pyogenes, and Clinical

MRSA. The best activity of this compound was against

Streptococcus pyogenes (

Table 3).

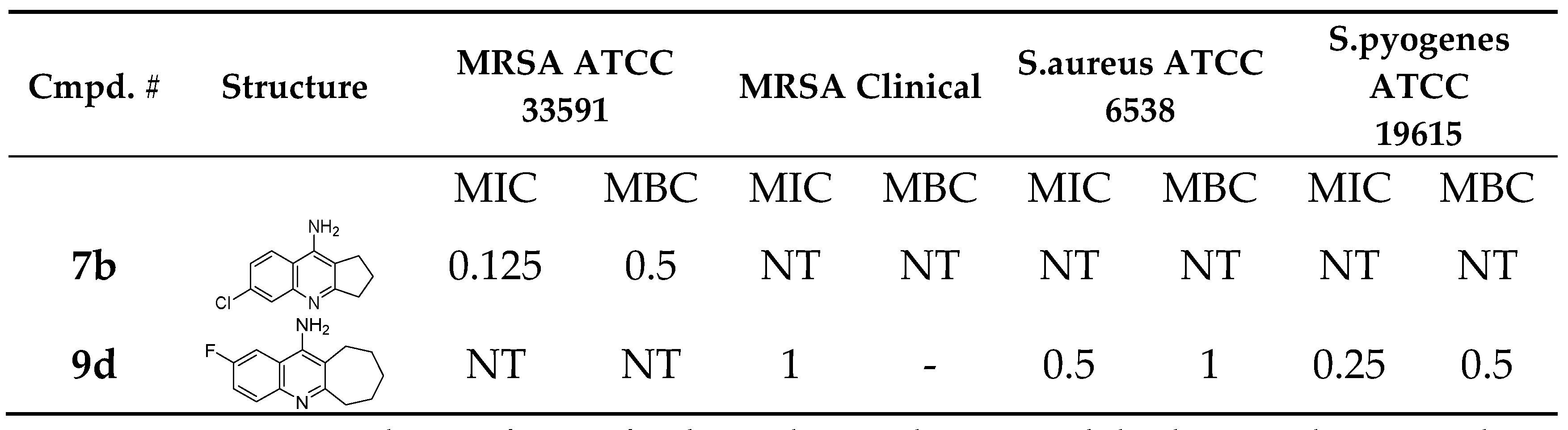

The Minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) and minimum bactericidal concentration (MBC) were determined as shown in

Table 4. Compound

7b exhibited good MIC against

MRSA, found to be 0.125 mM, also compound

9d exhibited good MIC against

S. pyogenes, found to be 0.25 mM (

Table 4).22,23

Imipenem was used as a reference for the antibacterial activity while Fluconazole was used as a reference for the antifungal activity.

3.3. Results of the Molecular Docking Experiment

Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (

MRSA) is a strain of

S. aureus that has developed resistance to the Beta-lactam antibiotics [

29]. Results in

Table 3 indicate that compounds

5b,

5e, and

7b have clear antibacterial effect on the

MRSA ATCC 33591 strains with inhibition zones of 12.5, 8.0, and 20 mm respectively (

Table 3). Simultaneously, compounds

5b,

5e, and

7b showed no activity against the clinical

MRSA strains (

Table 3). Meanwhile, compound

9d has an antibacterial effect on the clinical

MRSA strains (inhibition zone = 22 mm,

Table 3, MIC = 1 mM,

Table 4) and no inhibitory activity is shown against the non-clinical

MRSA strains. This variation in activity between these compounds suggests different mechanisms of action in inhibiting the different

MRSA strains.

In general, the inhibition of the

MRSA activity happens through two different mechanisms. Firstly, through inhibiting the transpeptidase enzymes also known as Penicillin-Binding Proteins (PBPs) [

30]. The PBPs are responsible for crosslinking the bacterial cell wall and so protecting the bacteria from the osmotic pressure and ultimately cell lysis and bursting. Secondly, is through inhibiting the integrase enzyme [

30]. The integrase enzyme is a nucleic acid processing enzyme found in bacteriophages [

31]. Integrase is responsible for inserting the DNA resistance genome into the MRSA genome. Integrase enzymes aid in the movement of specific DNA fragments from one DNA molecule to another, and hence help in developing resistance in clinical and nosocomial bacterial strands [

31].

To clarify the molecular mechanism of action of our anti-

MRSA active compounds we investigated the protein databank database (

https://www.rcsb.org) for the

MRSA targets and fortunately, we found two different crystals for the two different targets, namely; the crystallographic structure of

MRSA PBP2a (PDB code: 4DKI) which a resolution of 2.9 Å. And as for the

MRSA integrase enzyme we found the structure (PDB code: 3NKH) with a resolution of 2.5 Å. And these two proteins were used to dock our active synthesized compounds in two different docking experiments: the PBP docking experiment and the Integrase enzyme docking experiment.

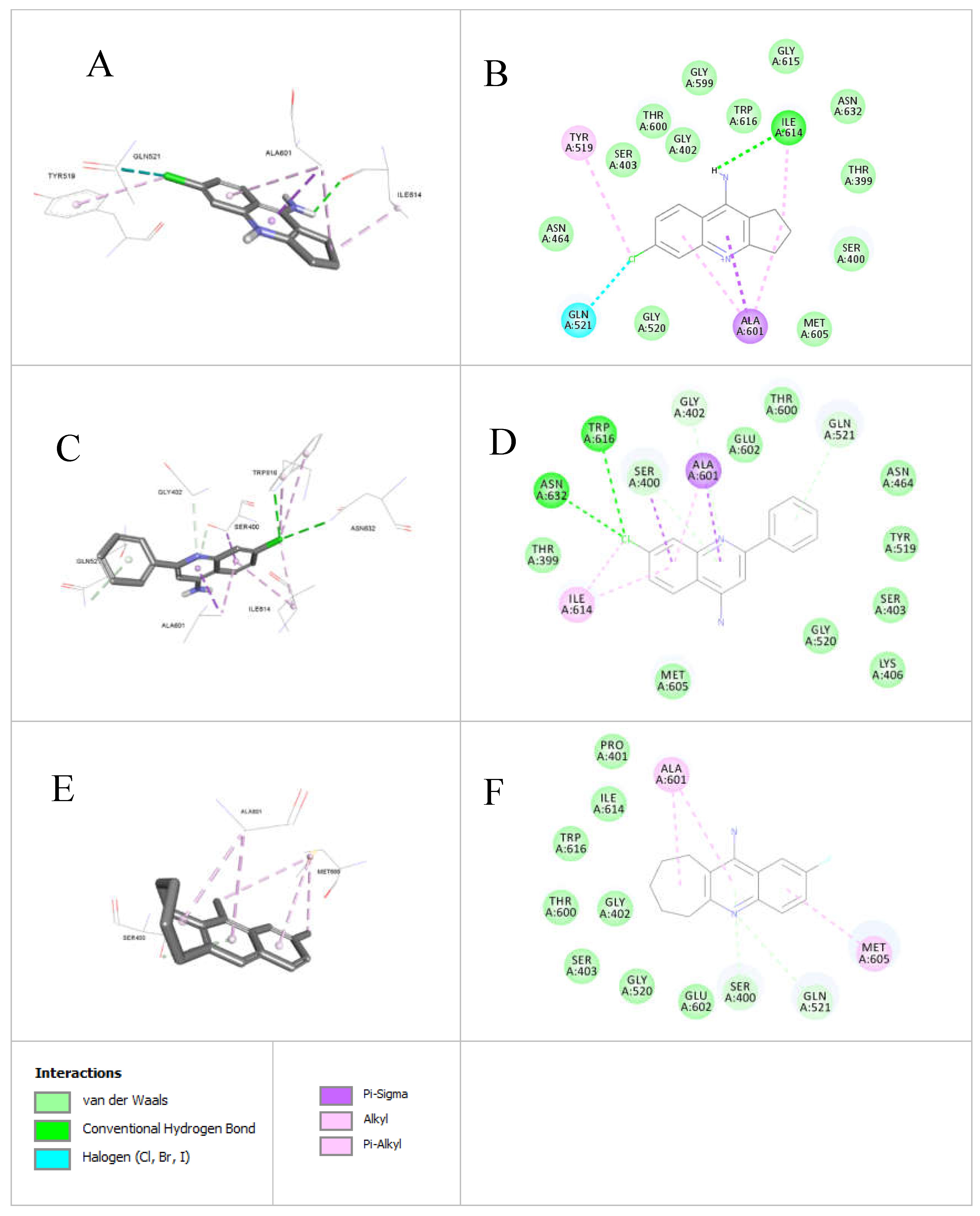

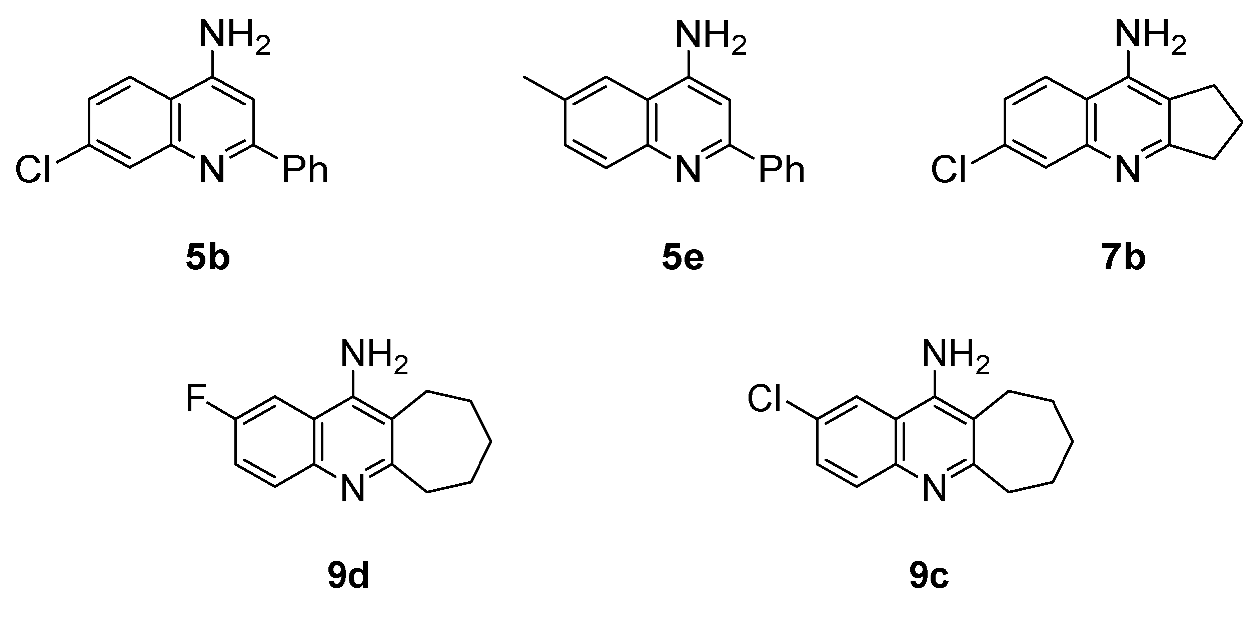

3.3.1. Docking of Anti-MRSA Active Compounds into the Binding Pocket of MRSA PBP2a Discussion

Both

5b (

MRSA ATCC 33591 inhibitory zone = 12.5mm,

Table 3) and

7b (

MRSA ATCC3 3591inhibitory zone = 20mm,

Table 3, MIC = 0.125 mM,

Table 4) can accommodate clear interactions with Gln521,

Figure 6. Nevertheless, compound

7b can accommodate extra Pi-alkyl interaction with Tyr519 (

Figure 6A and 6B), this extra interaction can explain the anti

-MRSA superiority of compound

7b over compound

5b. Moreover, compounds

5b and

7b show several Pi-alkyl, Pi-sigma, and alkyl interactions with the amino acidic Ala601. Although the binding modes of compounds (

5b and

7b) are different and are positioning the chlorine atom in opposite directions but still in both compounds the chlorine atom was able to make critical interactions inside the Penicillin-Binding Proteins (PBP2a) enzyme structure (PDB code: 4DK1) so that the chlorine atom was able to accommodate halogen interaction and Pi-alkyl interactions with Gln521 and Tyr519. On the other side, the chlorine atom in compound 5b was able to make several bonding interactions with the amino acids Try616 and Asn632 (

Figure 6C and 6D).

Compound

9d failed to accommodate properly inside the PBP2a binding pocket due to the huge heptacyclic ring and the lack of chlorine atom within its structure. The only interactions that compound

9d was able to make inside the

MRSA Penicillin-Binding Proteins (PBP2a) enzyme structure (PDB code: 4DK1) were the Van Der Waal and the alkyl interactions (

Figure 6E, and 6F).

The docking results (

Table 5) highlight distinct differences in the performance of

7b and

9d.

7b demonstrates good binding affinity with a docking score of -1.916, indicating a more stable interaction with the target compared to

9d, which has a score of -1.148. Furthermore,

7b exhibits stronger polar interactions, reflected by higher PLP1 (59.15), compared to

9d, which achieved PLP1 value of 51.16 and. Additionally,

7b shows favorable internal energy (-0.3) and higher steric complementarity (9.93) versus

9d, which had an internal energy of 2.15 and lower steric complementarity (-16.25). These findings suggest that

7b has stronger binding potential and maybe a more promising candidate for further investigation.

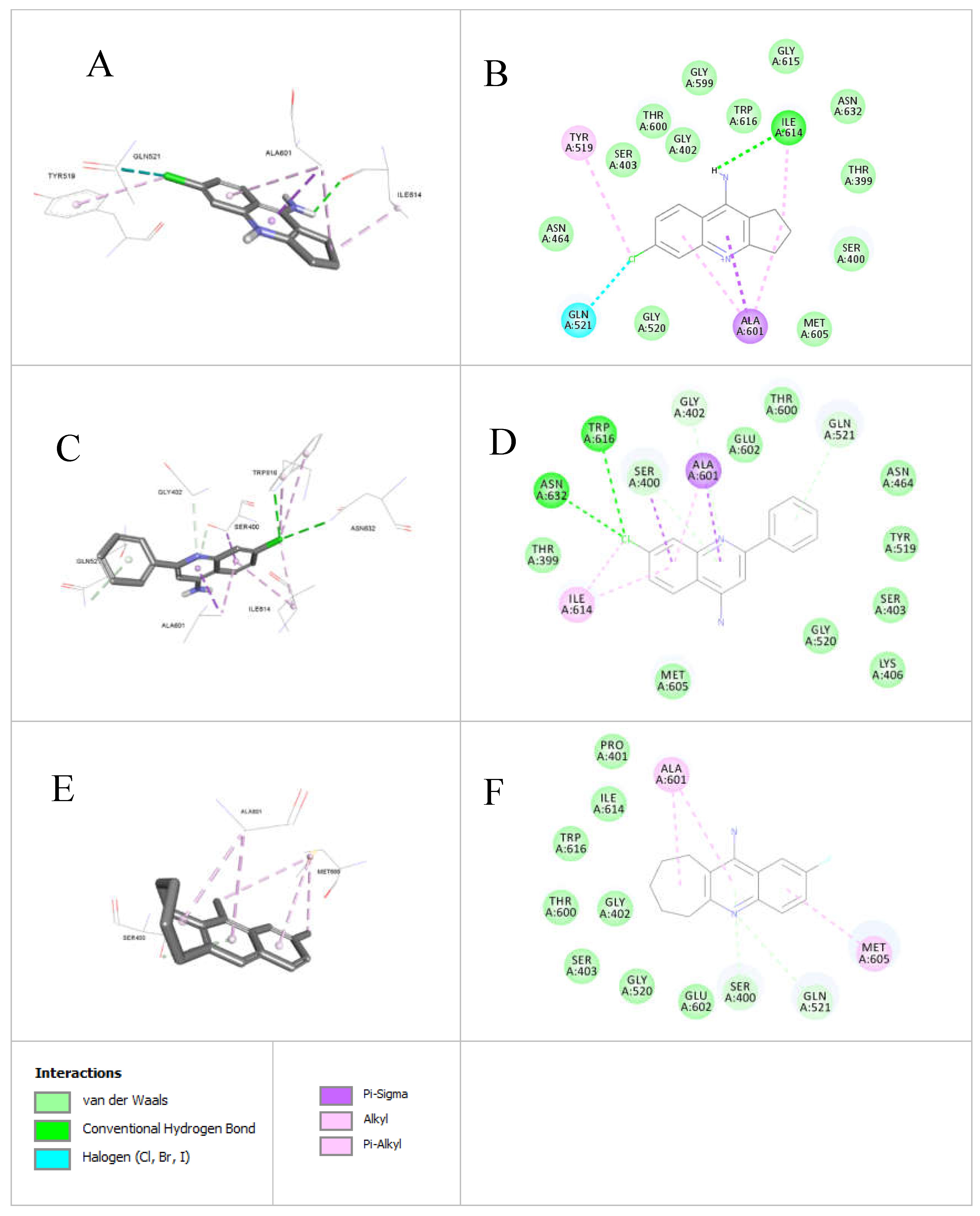

3.3.2. Docking of the Anti-MRSA Active Compounds Into the Binding Pocket MRSA Integrase

According to the obtained results in

Table 3, it was clear that compound

9d is showing a noticeable inhibitory activity against

MRSA clinical (inhibition zone =14 mm,

Table 3, MIC = 1 mM,

Table 4). Meanwhile, no other compound showed any activity against this strain of bacteria. Remarkably, compound

9c also showed no activity against the resistant MRSA clinical strain of bacteria although both

9c and

9d compounds represent very similar isosteres that differ only in the halogen atom on position 6; where compound

9d acquire the fluorine atom and compound

5e acquire the chlorine atom.

Upon investigation the

MRSA pathogenicity and its underlying molecular mechanisms, we found that nearly all

S. aureus strains can acquire up to four bacteriophages, classified into eight families based on the integrase gene and integration site [

31]. Briefly, the integrase enzyme is a nucleic acid processing enzyme found in bacteriophages. Integrase is responsible for inserting the DNA genome into the

MRSA genome. The genetic modification caused by the integrase enzyme is related to the resistance properties of the

MRSA and other virulent pathogenic processes caused by this bacterium.

A

MRSA integrase enzyme crystal was found in the protein databank database (

https://www.rcsb.org) (PDB code: 3NKH) with a resolution of 2.5 Å. And this crystal was used to dock compound

9c and compound

9d inside the previously reported binding site.

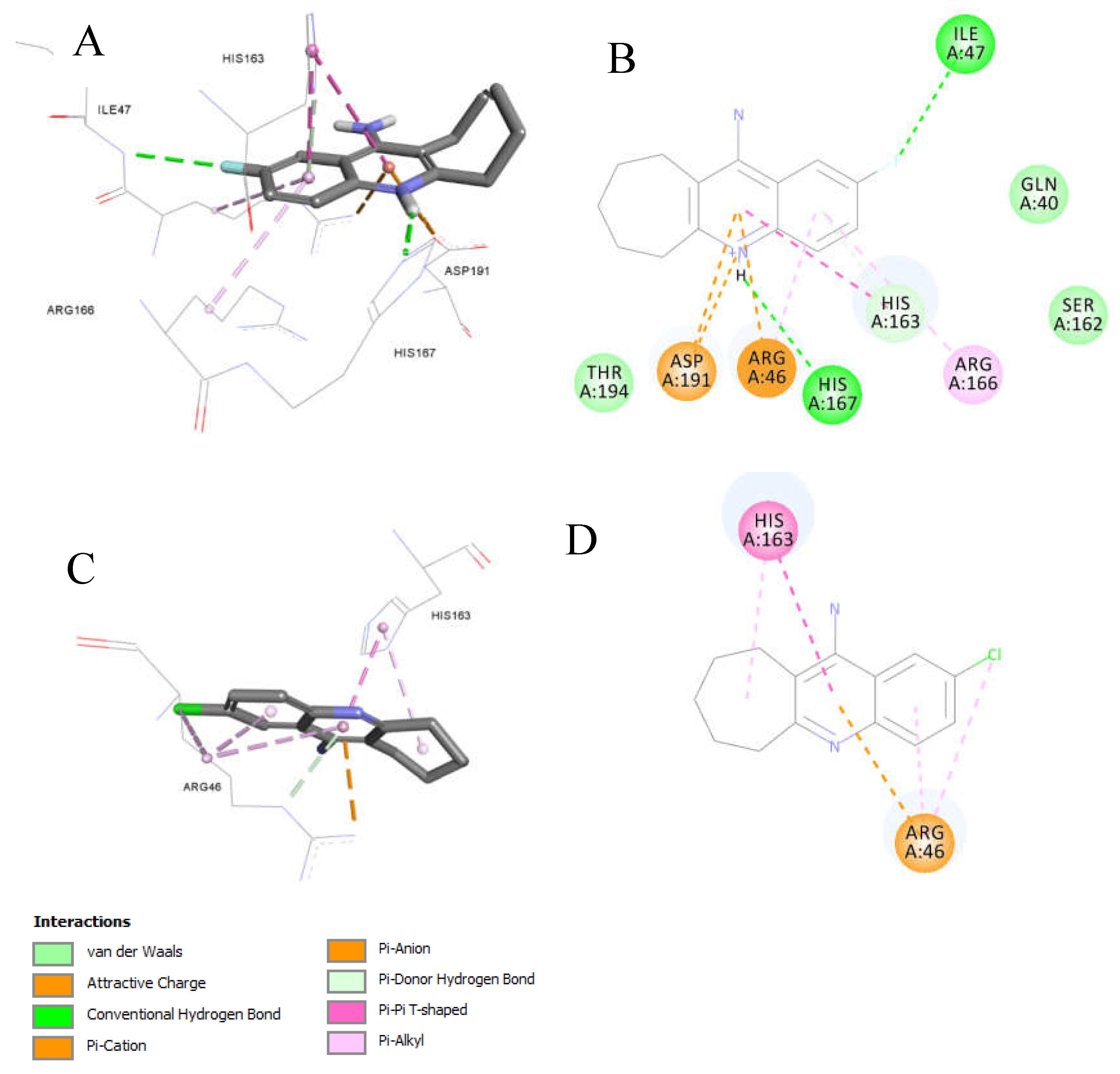

Compound

9d (MIC = 1 mM against clinical MRSA) laid freely inside the

MRSA integrase binding site (

Figure 7). Several interactions were observed, most interesting are the strong Pi-cation and charge interactions between

9d and

Arg46 and

Asp191. In addition, hydrogen bonding with His167. Moreover, the fluorine atom was able to act as a hydrogen bond acceptor and make a hydrogen bonding interaction with Ile47 (

Figure 7A and 7B). The fluorine-Ile47 hydrogen bonding interaction seems to be very critical since

9c (the chlorine isostere of

9d) failed to acquire this specific interaction and hence showed no inhibitory activity against the clinical

MRSA strains (Figure7C and 7D),

9d demonstrated good binding properties, as reflected in its docking scores (

Table 6). Specifically,

9d had a Ligscore1 of 2.42, Ligscore2 of 3.09, PLP1 of 24.22, and PLP2 of 42.31, significantly outperforming 9c, which scored 0.78, 2.4, 16.85, and 20.76, respectively.

9d's higher DockScore of 20.617 compared to 9c's 13.094 highlights its stronger binding affinity.

Notably, 9d exhibited critical Pi-cation and charge interactions with Arg46 and Asp191, hydrogen bonding with His167, and a unique fluorine-mediated hydrogen bond with Ile47, which appears to be vital for its activity. The inability of 9c to form this specific interaction with Ile47 likely accounts for its lack of inhibitory activity.

3.3.3. Ligand Pose Analysis Inside the Binding Pocket of MRSA-Penicillin Binding Protein 2a (PBP2a)

Our docking run resulted in 110 poses for our docked compounds inside the binding pocket of the MRSA PBP2A (PDB code: 4DK1).

Table S2 (Supp. Info.) shows the statistical residue analysis for the non-bond receptor-ligand interactions. Clearly, the interaction analysis reveals a strong binding profile characterized by a mix of hydrophobic and hydrogen-bond interactions. Hydrophobic interactions dominate, particularly from residues

ALA601and

ILE614, which contribute significantly to the binding affinity with 110 and 101 interactions, respectively. Polar residues like

SER400 and

THR399 enhance specificity through numerous hydrogen bonds (59 and 31, respectively), while halogen bonds from

THR399 and others add unique stabilizing features.

This combination of strong hydrophobic and specific polar interactions indicates a robust and well-balanced binding mechanism. Key residues such as ALA601, ILE614, and SER400 could serve as focal points for further optimization in drug design or structural studies, given their critical roles in stabilizing the interaction.

The statistical residue analysis aligns with the docking data of anti-MRSA compounds 5b, 7b, and 9d in the MRSA PBP2a binding pocket, highlighting key interactions critical to their activity.

Both

5b and

7b interact significantly with

Gln521, a residue shown in the statistical data to form 29 hydrogen bonds, emphasizing its role in stabilizing ligand binding.

7b’s additional Pi-alkyl interaction with

Tyr519 explains its superior MRSA inhibition (20 mm zone vs. 12.5 mm for

5b, Table 3).

Ala601, which forms the highest number of hydrophobic interactions (110 in the statistical data), is crucial for the binding of both compounds, as indicated by their Pi-alkyl, Pi-sigma, and alkyl interactions with this residue.

The chlorine atom in both 5b and interacts 7b with Gln521 and Tyr519, facilitating halogen and Pi-alkyl interactions, consistent with the statistical finding of halogen bonding for Tyr399, Asn632, and Trp616 (8-30 interactions). 5b additionally forms halogen bonds with Trp616 and Asn632, residues identified as minor contributors in the analysis. Conversely, 9d’s lack of a chlorine atom and bulky heptacyclic ring limits its interactions to weaker van der Waals and alkyl interactions, which explains its failure to properly bind and its reduced activity.

4. Conclusions

A series of 4-aminoquinolines was green synthesized using the MW-assisted method and scaled up in a sealed tube to get the same yields. Different substituted 2-aminobenzonitriles were reacted with some methylketones and cyclic ketones that possess -hydrogen to achieve different quinoline derivatives. All reactions occurred at 90-150 ºC and a 90-120 min reaction time which yields up to 95% of products. The purity of all products was approved using different spectroscopic methods. All compounds were tested for antibacterial and antifungal activity, and four substances were found to exhibit moderate antibacterial activity. 7b showed a good MIC against MRSA, found to be 0.125 mM and, 9d exhibited a good MIC against S. Pyogenes of 0.25 mM. Furthermore, a Structure Activity Relationship (SAR) docking study was performed inside the Penicillin Binding Protein (PBP). Docking analysis of our synthesized anti-MRSA compounds 5b, 7b, and 9d inside the MRSA PBP2a binding pocket (PDB: 4DK1) shows that 7b and 5b exhibit binding through hydrophobic (ALA601, ILE614), hydrogen bonding (GLN521), and halogen (TYR519, THR399) interactions, with 7b showing good MRSA inhibition (20 mm zone vs. 12.5 mm for 5b) due to additional Pi-alkyl interactions and favorable docking parameters, including a higher Ligscore2 (4.03), PLP1 (59.15), and Dock Score (34.31). Compound 9d showed weaker activity due to its bulky structure, limited interactions, and less favorable scores.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at:

www.mdpi.com/xxx/s1, Figure S1-S6: Spectral data (

1H-,

13C-NMR, Dept135, FTIR and HRMS; Table S1: Antimicrobial activity of various chemical compounds by agar diffusion method, the diameter of zones of inhibition measured in mm.; Table S2: Statistical Residue Analysis of Receptor-Ligand Interactions inside MRSA-Penicillin Binding Protein 2a (PBP2a).

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Koutentis, and Al-Momani; methodology, Abu Shawar, Abu Sarhan, Abu-Sini, and Mohammad; software, Shahin; formal analysis, Al-Momani, Abu Shawar, and Abu Sarhan;; resources, Al-Momani; data curation, Abu Shawar, Abu Sarhan, and Mohammad; writing—original draft preparation, Al-Momani; writing—review and editing, Koutentis, Shahin, and Abu-Sini; supervision, Koutentis, and Al-Momani; project administration, Al-Momani; funding acquisition, Al-Momani. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by The Hashemite University (HU) for the research grant No. 113/2022

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the Hashemite University (HU) for research grant No. 113/2022 and Al-Zaytoonah University of Jordan (ZU) for the biological studies. Many thanks also go to the NMR and IR unit at HU and Naba Hikma Labs for the high-resolution mass spectrometry (HR-MS).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Sheldon, R.A. E Factors, Green Chemistry and Catalysis: An Odyssey. Chemical Communications 2008, 3352–3365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Polshettiwar, V.; Varma, R.S. Microwave-Assisted Organic Synthesis and Transformations Using Benign Reaction Media. Acc Chem Res 2008, 41, 629–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Praet, S.; Preegel, G.; Rammal, F.; Sels, B.F. One-Pot Consecutive Reductive Amination Synthesis of Pharmaceuticals: From Biobased Glycolaldehyde to Hydroxychloroquine. ACS Sustain Chem Eng 2022, 10, 6503–6508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nainwal, L.M.; Tasneem, S.; Akhtar, W.; Verma, G.; Khan, M.F.; Parvez, S.; Shaquiquzzaman, M.; Akhter, M.; Alam, M.M. Green Recipes to Quinoline: A Review. Eur J Med Chem 2019, 164, 121–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ray, R.L. Alkaloids—The World’s Pain Killers. J Chem Educ 1960, 37, 451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matada, B.S.; Pattanashettar, R.; Yernale, N.G. A Comprehensive Review on the Biological Interest of Quinoline and Its Derivatives. Bioorg Med Chem 2021, 32, 115973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, K.; Jain, M.; Reddy, R.P.; Jain, R. Quinolines and Structurally Related Heterocycles as Antimalarials. Eur J Med Chem 2010, 45, 3245–3264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Browning, D.J. Pharmacology of Chloroquine and Hydroxychloroquine. In Hydroxychloroquine and Chloroquine Retinopathy; Browning, D.J., Ed.; Springer New York: New York, NY, 2014; ISBN 978-1-4939-0597-3. [Google Scholar]

- PANDEY, A. V; BISHT, H.; BABBARWAL, V.K.; SRIVASTAVA, J.; PANDEY, K.C.; CHAUHAN, V.S. Mechanism of Malarial Haem Detoxification Inhibition by Chloroquine. Biochemical Journal 2001, 355, 333–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kimura, T.; Takabatake, Y.; Takahashi, A.; Isaka, Y. Chloroquine in Cancer Therapy: A Double-Edged Sword of Autophagy. Cancer Res 2013, 73, 3–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gautret, P.; Lagier, J.-C.; Parola, P.; Hoang, V.T.; Meddeb, L.; Mailhe, M.; Doudier, B.; Courjon, J.; Giordanengo, V.; Vieira, V.E.; et al. Hydroxychloroquine and Azithromycin as a Treatment of COVID-19: Results of an Open-Label Non-Randomized Clinical Trial. Int J Antimicrob Agents 2020, 56, 105949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tzekov, R. Ocular Toxicity Due to Chloroquine and Hydroxychloroquine:Electrophysiological and Visual Function Correlates. Documenta Ophthalmologica 2005, 110, 111–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verbaanderd, C.; Maes, H.; Schaaf, M.B.; Sukhatme, V.P.; Pantziarka, P.; Sukhatme, V.; Agostinis, P.; Bouche, G. Repurposing Drugs in Oncology (ReDO) - Chloroquine and Hydroxychloroquine as Anti-Cancer Agents. Ecancermedicalscience 2017, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, W.; Wang, H.; Yang, Y.; Chen, Z.-S.; Zou, C.; Zhang, J. Chloroquine against Malaria, Cancers and Viral Diseases. Drug Discov Today 2020, 25, 2012–2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lei, Z.-N.; Wu, Z.-X.; Dong, S.; Yang, D.-H.; Zhang, L.; Ke, Z.; Zou, C.; Chen, Z.-S. Chloroquine and Hydroxychloroquine in the Treatment of Malaria and Repurposing in Treating COVID-19. Pharmacol Ther 2020, 216, 107672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nardi, N.; Baumgarten, L.G.; Dreyer, J.P.; Santana, E.R.; Winiarski, J.P.; Vieira, I.C. Nanocomposite Based on Green Synthesis of Gold Nanoparticles Decorated with Functionalized Multi-Walled Carbon Nanotubes for the Electrochemical Determination of Hydroxychloroquine. J Pharm Biomed Anal 2023, 236, 115681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abumansour, H.; Abusara, O.H.; Khalil, W.; Abul-Futouh, H.; Ibrahim, A.I.M.; Harb, M.K.; Abulebdah, D.H.; Ismail, W.H. Biological Evaluation of Levofloxacin and Its Thionated Derivatives: Antioxidant Activity, Aldehyde Dehydrogenase Enzyme Inhibition, and Cytotoxicity on A549 Cell Line. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, N.; Xie, H.; Lu, W.; Li, F.; Li, J.; Guo, Z. Chloroquine Sensitizes Hepatocellular Carcinoma Cells to Chemotherapy via Blocking Autophagy and Promoting Mitochondrial Dysfunction; 2017; Vol. 10;

- Latarissa, I.R.; Barliana, M.I.; Meiliana, A.; Lestari, K. Potential of Quinine Sulfate for Covid-19 Treatment and Its Safety Profile: Review. Clin Pharmacol 2021, 13, 225–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.; Song, J.; Shang, Y.; Shan, M.; Tang, L.; Pang, T.; Ye, Q.; Cheng, G.; Jiang, G. Design, Synthesis, Biological Evaluation and Docking Study of A New Series of 9-Aminoacridine Derivatives as Anti-Inflammatory Agents. ChemistrySelect 2024, 9, e202302387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauer, A.W.; Kirby, W.M.M.; Sherris, J.C.; Turck, M. Antibiotic Susceptibility Testing by a Standardized Single Disk Method. Am J Clin Pathol 1966, 45, 493–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gedam, V.; Punyapwar, S.; Raut, P.; Chahande, A. Rapid In Vitro Proliferation of Tinospora Cordifolia Callus Biomass from Stem and Leaf with Phytochemical and Antimicrobial Assessment: 7th IconSWM—ISWMAW 2017, Volume 2. In; 2019; pp. 421–431 ISBN 978-981-13-2783-4.

- Ibrahim, A.I.M.; Abul-Futouh, H.; Bourghli, L.M.S.; Abu-Sini, M.; Sunoqrot, S.; Ikhmais, B.; Jha, V.; Sarayrah, Q.; Abulebdah, D.H.; Ismail, W.H. Design and Synthesis of Thionated Levofloxacin: Insights into a New Generation of Quinolones with Potential Therapeutic and Analytical Applications. Curr Issues Mol Biol 2022, 44, 4626–4638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, G.; Robertson, D.H.; Brooks III, C.L.; Vieth, M. Detailed Analysis of Grid-Based Molecular Docking: A Case Study of CDOCKER—A CHARMm-Based MD Docking Algorithm. J Comput Chem 2003, 24, 1549–1562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krammer, A.; Kirchhoff, P.D.; Jiang, X.; Venkatachalam, C.M.; Waldman, M. LigScore: A Novel Scoring Function for Predicting Binding Affinities. J Mol Graph Model 2005, 23, 395–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gehlhaarl, D.K.; Verkhivkerl, G.M.; Rejtol, P.A.; Sherman, C.J.; Fogel, D.B.; Fogel, L.J.; Freer’, S.T. Molecular Recognition of the Inhibitor AC-1343 by HIV-l Protease: Conformationally Flexible Docking by Evolutionary Programming. Chem Biol 1995, 2, 317–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jain, A.N. Scoring Functions for Protein-Ligand Docking. Curr Protein Pept Sci 2006, 7, 407–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muegge, I.; Martin, Y.C. A General and Fast Scoring Function for Protein-Ligand Interactions: A Simplified Potential Approach. J Med Chem 1999, 42, 791–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bæk, K.T.; Gründling, A.; Mogensen, R.G.; Thøgersen, L.; Petersen, A.; Paulander, W.; Frees, D. β-Lactam Resistance in Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus Aureus USA300 Is Increased by Inactivation of the ClpXP Protease. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2014, 58, 4593–4603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lovering, A.L.; Gretes, M.C.; Safadi, S.S.; Danel, F.; De Castro, L.; Page, M.G.P.; Strynadka, N.C.J. Structural Insights into the Anti-Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus Aureus (MRSA) Activity of Ceftobiprole. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2012, 287, 32096–32102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purrello, S.M.; Daum, R.S.; Edwards, G.F.S.; Lina, G.; Lindsay, J.; Peters, G.; Stefani, S. Meticillin-Resistant Staphylococcus Aureus (MRSA) Update: New Insights into Bacterial Adaptation and Therapeutic Targets. J Glob Antimicrob Resist 2014, 2, 61–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

The structure of chloroquine (CQ) and hydroxychloroquine (HCQ), 4-aminoquinoline moiety in red.

Figure 1.

The structure of chloroquine (CQ) and hydroxychloroquine (HCQ), 4-aminoquinoline moiety in red.

Scheme 1.

Reaction of substituted 2-aminobenzonitriles 1a-e and methylketones 2 and 3.

Scheme 1.

Reaction of substituted 2-aminobenzonitriles 1a-e and methylketones 2 and 3.

Scheme 2.

Reaction of substituted 2-aminobenzonitriles 1a-e and cycloketones 6a-d.

Scheme 2.

Reaction of substituted 2-aminobenzonitriles 1a-e and cycloketones 6a-d.

Figure 2.

(a) 1H-NMR of the aromatic region of Zn-bound 7b; (b) 1H-NMR of the aromatic region of Zn-free 7b.

Figure 2.

(a) 1H-NMR of the aromatic region of Zn-bound 7b; (b) 1H-NMR of the aromatic region of Zn-free 7b.

Figure 3.

(A) 13C-NMR of the aromatic region of Zn-bound 7b; (B) 13C-NMR of the aromatic region of Zn-free 7b.

Figure 3.

(A) 13C-NMR of the aromatic region of Zn-bound 7b; (B) 13C-NMR of the aromatic region of Zn-free 7b.

Figure 4.

A) 1H-NMR of the aromatic region of 4d; B) 1H-NMR of the aromatic region of 4b.

Figure 4.

A) 1H-NMR of the aromatic region of 4d; B) 1H-NMR of the aromatic region of 4b.

Figure 5.

A) 13C-NMR of the aromatic region of 4d; B) 13C-NMR of the aromatic region of 4b.

Figure 5.

A) 13C-NMR of the aromatic region of 4d; B) 13C-NMR of the aromatic region of 4b.

Figure 6.

Active compounds docked into the Penicillin-Binding Proteins (PBPs) enzyme structure (PDB code: 4DK1): a) Docked structure of

7b (diameter of zones of inhibition. = 20 mm,

Table 3) into the crystal structure of PBP from MRSA strain Staphylococcus aureus structure (PDB code: 3DK1, 2.9 Ǻ); b) 2D Docked structure of

7b (diameter of zones of inhibition. = 20 mm,

Table 3) into the crystal structure of integrase from MRSA strain Staphylococcus aureus structure (PDB code: 34DK1, 2.9 Ǻ); c) Docked structure of

5b (diameter of zones of inhibition. = 12.5 mm,

Table 3) into the crystal structure of PBP from MRSA strain Staphylococcus aureus structure (PDB code: 4DK1, 2.9 Ǻ); d) 2D Docked structure of

5b (diameter of zones of inhibition. = 12.5 mm,

Table 3) into the crystal structure of PBP from MRSA strain Staphylococcus aureus structure (PDB code: 4DK1, 2.9 Ǻ); e) Docked structure of

9d (diameter of zones of inhibition. = NZ,

Table 3) into the crystal structure of PBP from MRSA strain Staphylococcus aureus structure (PDB code: 3DK1, 2.9 Ǻ); f) 2D Docked structure of

9d (diameter of zones of inhibition. = NZ,

Table 3) into the crystal structure of integrase from MRSA strain Staphylococcus aureus structure (PDB code: 34DK1, 2.9 Ǻ).

Figure 6.

Active compounds docked into the Penicillin-Binding Proteins (PBPs) enzyme structure (PDB code: 4DK1): a) Docked structure of

7b (diameter of zones of inhibition. = 20 mm,

Table 3) into the crystal structure of PBP from MRSA strain Staphylococcus aureus structure (PDB code: 3DK1, 2.9 Ǻ); b) 2D Docked structure of

7b (diameter of zones of inhibition. = 20 mm,

Table 3) into the crystal structure of integrase from MRSA strain Staphylococcus aureus structure (PDB code: 34DK1, 2.9 Ǻ); c) Docked structure of

5b (diameter of zones of inhibition. = 12.5 mm,

Table 3) into the crystal structure of PBP from MRSA strain Staphylococcus aureus structure (PDB code: 4DK1, 2.9 Ǻ); d) 2D Docked structure of

5b (diameter of zones of inhibition. = 12.5 mm,

Table 3) into the crystal structure of PBP from MRSA strain Staphylococcus aureus structure (PDB code: 4DK1, 2.9 Ǻ); e) Docked structure of

9d (diameter of zones of inhibition. = NZ,

Table 3) into the crystal structure of PBP from MRSA strain Staphylococcus aureus structure (PDB code: 3DK1, 2.9 Ǻ); f) 2D Docked structure of

9d (diameter of zones of inhibition. = NZ,

Table 3) into the crystal structure of integrase from MRSA strain Staphylococcus aureus structure (PDB code: 34DK1, 2.9 Ǻ).

Figure 7.

Active compounds docked into the integrase enzyme structure (PDB code: 3NKH): a) Docked structure of

9d (diameter of zones of inhibition. = 14 mm,

Table 3) into the crystal structure of integrase from MRSA strain Staphylococcus aureus structure (PDB code: 3NKH, 2.5 Ǻ); b) 2D Docked structure of

9d (diameter of zones of inhibition. = 14 mm,

Table 3) into the crystal structure of integrase from MRSA strain Staphylococcus aureus structure (PDB code: 3NKH, 2.5 Ǻ); c) Docked structure of

9c (No inhibition zone,

Table 3) into the crystal structure of integrase from MRSA strain Staphylococcus aureus structure (PDB code: 3NKH, 2.5 Ǻ); d) 2D Docked structure of

9c (No inhibition zone,

Table 3) into the crystal structure of integrase from MRSA strain Staphylococcus aureus structure (PDB code: 3NKH, 2.5 Ǻ).

Figure 7.

Active compounds docked into the integrase enzyme structure (PDB code: 3NKH): a) Docked structure of

9d (diameter of zones of inhibition. = 14 mm,

Table 3) into the crystal structure of integrase from MRSA strain Staphylococcus aureus structure (PDB code: 3NKH, 2.5 Ǻ); b) 2D Docked structure of

9d (diameter of zones of inhibition. = 14 mm,

Table 3) into the crystal structure of integrase from MRSA strain Staphylococcus aureus structure (PDB code: 3NKH, 2.5 Ǻ); c) Docked structure of

9c (No inhibition zone,

Table 3) into the crystal structure of integrase from MRSA strain Staphylococcus aureus structure (PDB code: 3NKH, 2.5 Ǻ); d) 2D Docked structure of

9c (No inhibition zone,

Table 3) into the crystal structure of integrase from MRSA strain Staphylococcus aureus structure (PDB code: 3NKH, 2.5 Ǻ).

Table 1.

The chemical shift ( = ppm) of the NH2 and aromatic protons of Zn-bound and Zn-free compound of 7b.

Table 1.

The chemical shift ( = ppm) of the NH2 and aromatic protons of Zn-bound and Zn-free compound of 7b.

| Cmpd. # |

NH2 |

H-5 |

H-7 |

H-8 |

| 7b Zn-bound |

7.08 |

7.78 |

7.35 |

8.18 |

| 7b Zn-free |

6.57 |

7.67 |

7.31 |

8.16 |

Table 2.

The chemical shift ( = ppm) of the aromatic 13C of Zn-bound and Zn-free compound of 7b.

Table 2.

The chemical shift ( = ppm) of the aromatic 13C of Zn-bound and Zn-free compound of 7b.

| Cmpd. # |

C3a |

C4a |

C5 |

C6 |

C7 |

C8 |

C8a |

C9 |

C9a |

| 7b Zn-bound |

166.37 |

146.68 |

124.69 |

133.64 |

115.73 |

123.65 |

114.51 |

148.26 |

114.51 |

| 7b Zn-free |

168.00 |

146.28 |

126.79 |

132.29 |

122.76 |

124.21 |

116.20 |

149.33 |

113.86 |

Table 3.

Antimicrobial activity of compound 5b, 5e, 7b, 9c and 9d by agar diffusion method, the diameter of zones of inhibition measured in mm.

Table 3.

Antimicrobial activity of compound 5b, 5e, 7b, 9c and 9d by agar diffusion method, the diameter of zones of inhibition measured in mm.

Table 4.

Minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) and minimum bactericidal concentration (MBC) results for the synthesized compounds 7b and 9d. Concentrations were measured in mM.

Table 4.

Minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) and minimum bactericidal concentration (MBC) results for the synthesized compounds 7b and 9d. Concentrations were measured in mM.

Table 5.

Docking results for 7b and 9d inside the binding pocket of MRSA-Penicillin Binding Protein 2a (PBP2a) (PDB code: 4DKI, resolution = 2.9Å), showing key binding parameters including Ligscore (1 and 2), PLP1, PLP2, Jain score, PMF, Docking Score, and Ligand Internal Energy.

Table 5.

Docking results for 7b and 9d inside the binding pocket of MRSA-Penicillin Binding Protein 2a (PBP2a) (PDB code: 4DKI, resolution = 2.9Å), showing key binding parameters including Ligscore (1 and 2), PLP1, PLP2, Jain score, PMF, Docking Score, and Ligand Internal Energy.

| Cmpd. # |

Ligscore1 dreiding |

Ligscore2 dreiding |

PLP1 |

PLP2 |

Jain |

PMF |

Dock Score |

Ligand Internal energy |

| 7b |

1.5 |

4.03 |

59.15 |

60.01 |

-0.3 |

9.93 |

34.317 |

-1.916 |

| 9d |

0.69 |

2.05 |

51.16 |

65.23 |

2.15 |

-16.25 |

8.764 |

-1.148 |

Table 6.

Docking results for 5e and 9d inside the binding pocket of MRSA integrase enzyme (PDB code: 3NKH, resolution = 2.5Å), showing key binding parameters including Ligscore (1 and 2), PLP1, PLP2, Jain score, PMF, Docking Score, and Ligand Internal Energy.

Table 6.

Docking results for 5e and 9d inside the binding pocket of MRSA integrase enzyme (PDB code: 3NKH, resolution = 2.5Å), showing key binding parameters including Ligscore (1 and 2), PLP1, PLP2, Jain score, PMF, Docking Score, and Ligand Internal Energy.

| Cmpd. # |

Ligscore1 dreiding |

Ligscore2 dreiding |

PLP1 |

PLP2 |

Jain |

PMF |

DockScore |

Ligand Internal energy |

| 5e |

0.78 |

2.4 |

16.85 |

20.76 |

-1.18 |

56.81 |

13.094 |

-0.294 |

| 9d |

2.42 |

3.09 |

24.22 |

42.31 |

2.44 |

78.12 |

20.617 |

-1.148 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).