1. Introduction

The survival rate of children and adolescents with acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) has progressively improved in recent decades [

1]. However, this has led to the development of many comorbidities in ALL survivors. In patients with ALL, it has been demonstrated that the treatment has a negative effect on bone health. Glucocorticoids are some of the most potent osteotoxic drugs that are routinely prescribed in pediatric patients with ALL [

1] and are associated with bone morbidities such as osteoporosis. These drugs affect the function of mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs), such as osteoblasts, osteocytes, and osteoclasts, due to their multiple mechanisms of action underlying the changes in several remodeling processes, including PPARγR2 upregulation, increased sclerostin expression, increased Receptor Activator of Nuclear Factor κB Ligand and osteoprotegerin ratio (RANKL/OPG), and altered renal and intestinal calcium handling [

1,

2].

Childhood and adolescence are important periods in the attainment of peak bone mass, which can be impaired by various factors, such as nutritional status, drug use, and the presence of neoplasms, increasing the risk of developing osteoporosis and fractures in adulthood [

3].

In addition, low bone mineral density and fractures have been partly attributed to vitamin D deficiency during treatment for pediatric ALL. This deficiency is due to long inpatient stays; decreased outdoor activities (reducing exposure to sunlight, thus impairing vitamin D synthesis); and a lack of appetite, which results in a decreased dietary intake of vitamin D [

4]. Vitamin D plays an important role in maintaining calcium and phosphorus homeostasis and therefore bone health in childhood and adolescence [

5]; it has direct effects on the main cells involved in bone metabolism, stimulating osteoblast differentiation and the synthesis of proteins involved in calcium deposition, thus increasing bone matrix mineralization [

6].

Previous studies have reported that vitamin D levels decrease in children with leukemia undergoing treatment [

7,

8]. Our group of collaborators recently reported a high frequency of vitamin D deficiency >90% in the early stages of treatment, in addition to an increase in bone resorption markers, showing that these patients experience alterations in bone remodeling [

5]. For this reason, pediatric patients with ALL are candidates for nutritional interventions that reverse bone deterioration, such as vitamin D and calcium supplementation.

However, the ideal dose, time of supplementation, and optimal levels of vitamin D remain controversial [

9,

10,

11,

12]. Previous studies have shown discrepancies in the impact of vitamin D supplementation on bone mineral density and bone formation and resorption markers.

Different studies have demonstrated that omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids (LCPUFAs-ω3), such as docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) and eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA), have great benefits for treating and preventing various diseases, including cardiovascular, neurodegenerative, cancer, and bone diseases. More recently, it has been suggested that they help decrease bone loss and the risk of osteoporosis by inhibiting the production of inflammatory cytokines, such as IL-1, IL-6, and TNF-α. In addition, omega-3 fatty acids have been shown to enhance bone health, as they have been reported to inhibit osteoclast activity Fish oil administration has been found to inhibit the expression of macrophage colony-stimulating factor (M-CSF), Microphthalmia-associated transcription factor (MITF), and Receptor Activator of Nuclear Factor κ B (RANK) and, as a result, inhibit bone resorption Another mechanism by which LCPUFAs-ω3 attenuates osteoclast activity is by decreasing the production of prostaglandin E2, which, at low concentrations, has been shown to favor increased osteoblastogenesis [

13].

In pediatric patients with ALL, omega-3 fatty acid supplementation has been reported to have positive effects, for example, lowering lipid levels, maintaining body composition, and decreasing cardiovascular risk [

14,

15,

16,

17]. In this sense, it has been suggested that LCPUFAs-ω3 play an important role in bone metabolism and may thus represent a non-pharmacological (nutraceutical) means of reducing alterations in bone metabolism. To the best of our knowledge, information about nutritional interventions with vitamin D in pediatric patients with ALL has been limited to reports describing only the changes that occur during the supplementation period, with no reports describing how long the effect of supplementation with omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids, vitamin D, and calcium on vitamin D nutritional status and bone turnover markers lasts after supplementation ends. Therefore, we evaluated the effect of daily LCPUFAs-ω3 supplementation combined with vitamin D and calcium on bone turnover markers and changes in vitamin D concentrations during 6 weeks of supplementation followed by 6 weeks post-intervention follow-up in pediatric patients with acute lymphoblastic leukemia.

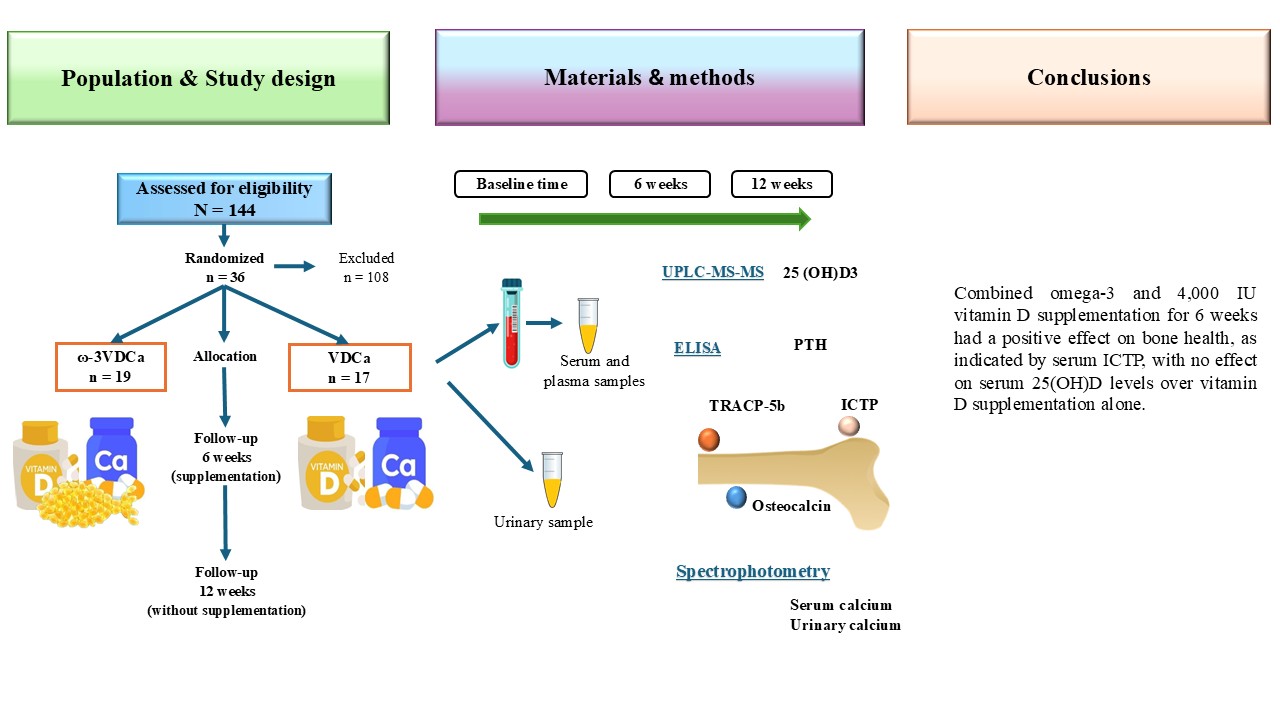

2. Materials and Methods

Study Design

This randomized controlled clinical trial was conducted according to the Declaration of Helsinki [

18] and received approval from the Research and Ethics Committee of the Instituto Mexicano del Seguro Social (IMSS) in Mexico City (Approval # 2019-785-021). This trial was registered at clinicaltrials.gov under trial ID NCT05950204. Data collection began after all parents or legal guardians of the children provided written informed consent following the explanation of the procedures.

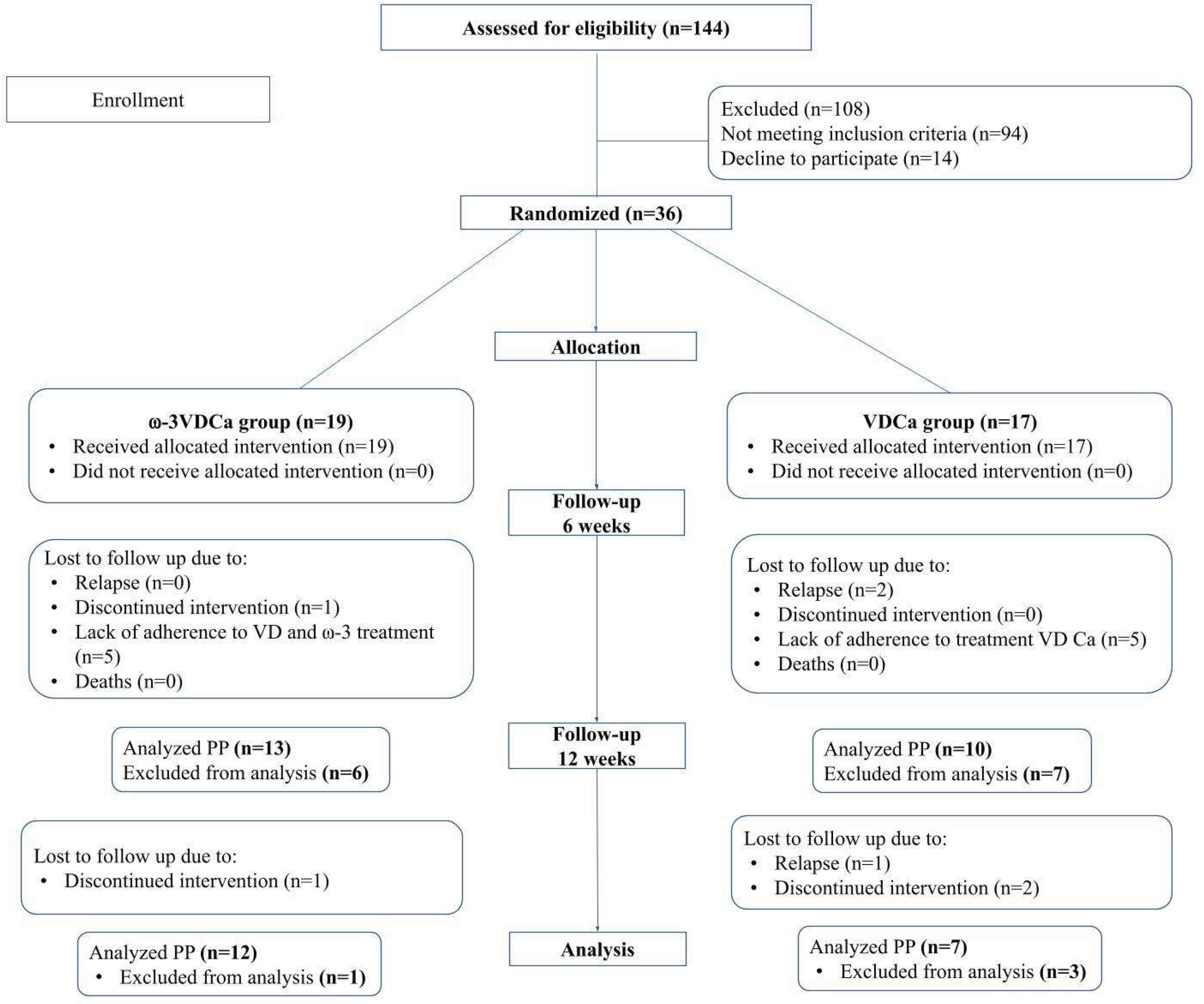

Patients

One hundred and eight patients with ALL in the maintenance phase were eligible for the study, which was conducted at the Pediatric Hospital, Centro Médico Nacional SXXI, Instituto Mexicano del Seguro Social (IMSS) in Mexico City, from September 2022 to August 2024. The exclusion criteria were as follows: children who had fish allergies or those who were unable to swallow capsules (LCPUFAs-ω3); with Down syndrome, hypersensitivity to cholecalciferol or metabolites of vitamin D3; hyperphosphatemia, hypercalcemia, hypercalciuria, or calcium lithiasis; and children who routinely consumed vitamin supplements or LCPUFAs-ω3. A total of 94 patients were excluded because they did not meet the inclusion criteria, and 14 because they refused to participate. Therefore, 36 patients (5.0–17 years) were randomized. Patients were classified into 3 groups according to the next characteristics: SR included good steroid response, age > 1 year < 7 years, initial white blood cell count less than 20,000/mm3, bone marrow in remission at day + 33, no immunophenotype T, no HR criteria; IR comprised age > 7 to < 10 years, initial white blood cell count 20,000/mm3 to < 50,000/mm3, immunophenotype T, no HR criteria, and HR patients with poor response to prednisone, initial white blood cell count > 50,000/mm3, no response to induction on day +33, t (9, 22), t (4,11).

At our Institute, we use the HP09 chemotherapy protocol, based on the BFM95. The patients began treatment with 50 mg/m2 of prednisone monotherapy daily for 7 days. Then, they began the remission induction phase (lasting for 29–33 days), during which they received 60 mg/m2 of prednisone, 1.5 mg/m2 of vincristine, 30 mg/m2 of daunorubicin, 5000 IU/m2 of L-asparaginase, and intrathecal chemotherapy. During the consolidation phase, they received 60 mg/m2 of 6-mercaptopurine, 1000 mg/m2 of cyclophosphamide IV, 75 mg/m2 of ARA-C IV, and intrathecal chemotherapy. Additionally, high-risk patients received 20 mg/m2 of dexamethasone and 25,000 IU/m2 of L-asparaginase. The intensification phase included 60 mg/m2 of prednisone, 1.5 mg/m2 of vincristine, 30 mg/m2 of daunorubicin, and 5,000 IU/m2 of L-asparaginase. Finally, in the maintenance phase, all patients received 50 mg/m2 of 6-mercaptopurine and 20 mg/m2 of oral methotrexate [

19].

Sample Size

The sample size was calculated for the outcomes of bone metabolism markers, such as vitamin D, osteocalcin (OC), and human cross-linked C-terminal telopeptides of type I collagen (ICTP). The sample size was calculated based on the mean and standard deviation, and a z-alpha value of 0.05 and a beta value of 0.80 were considered, using the formula for the mean difference. Considering the potential of 20% attrition, the final sample size was 18 subjects per group.

Recruitment and Allocation

The selected children were recruited, screened, and randomized (1:1) to VDCa group or ω3VDCa group using a computer-generated list of random numbers with software for parallel groups (Random Allocation Software,

http://www.msaghaei.com/ Softwares/dnld/RA.zip) [

20]. Randomization was carried out in balanced blocks of ten children. Physicians, researchers, and nutritionists were blinded to the treatment allocation for the duration of the study. An unblinded technician supervised the randomization. Investigators were blinded to group allocation until the study was concluded.

Intervention

LCPUFAs-ω3 (EPA+DHA) were administered at a rate of 100 mg/kg/d capsules as natural triglyceride soft gels made of gelatin, without any artificial color or flavor, molecularly distilled; with a maximum dose of 3 g/d containing 225 mg of DHA, 325 mg of EPA, and 90 mg of other LCPUFAs-ω3 per capsule (Nordic Naturals, Inc. Watsonville CA, USA). The capsules were swallowed with water. The LCPUFAs-ω3 complied with the principles established for fats according to the European Pharmacopoeia Standard (EPS) and according to the Council for Responsible Nutrition (CRN) and the Global Organization (CRNGO), in which they are considered safe products that do not exceed the maximum allowances for contaminants such as peroxides, heavy metals, dioxins, and PCBs. All capsules contained 30 mg of vitamin E as an antioxidant. Calcium was administered as calcium carbonate (CALCID®) at 1000 mg/day orally in cherry, orange, or lemon flavor and chewed. Vitamin D was administered orally as cholecalciferol at 4,000 IU (100 µg)/day (Histofil®), dissolved in water in advance of offering to the child. The VDCa group received the same doses of vitamin D and calcium. The supplementation duration was 6 weeks, and all children were evaluated again 6 weeks after the intervention. During the study period, supplementation was monitored by phone or in the hospital if necessary for medical reasons. The side effects presented by the children (constipation, vomiting, nausea, diarrhea, burps, or headache) during the intervention were documented and registered by one of the researchers.

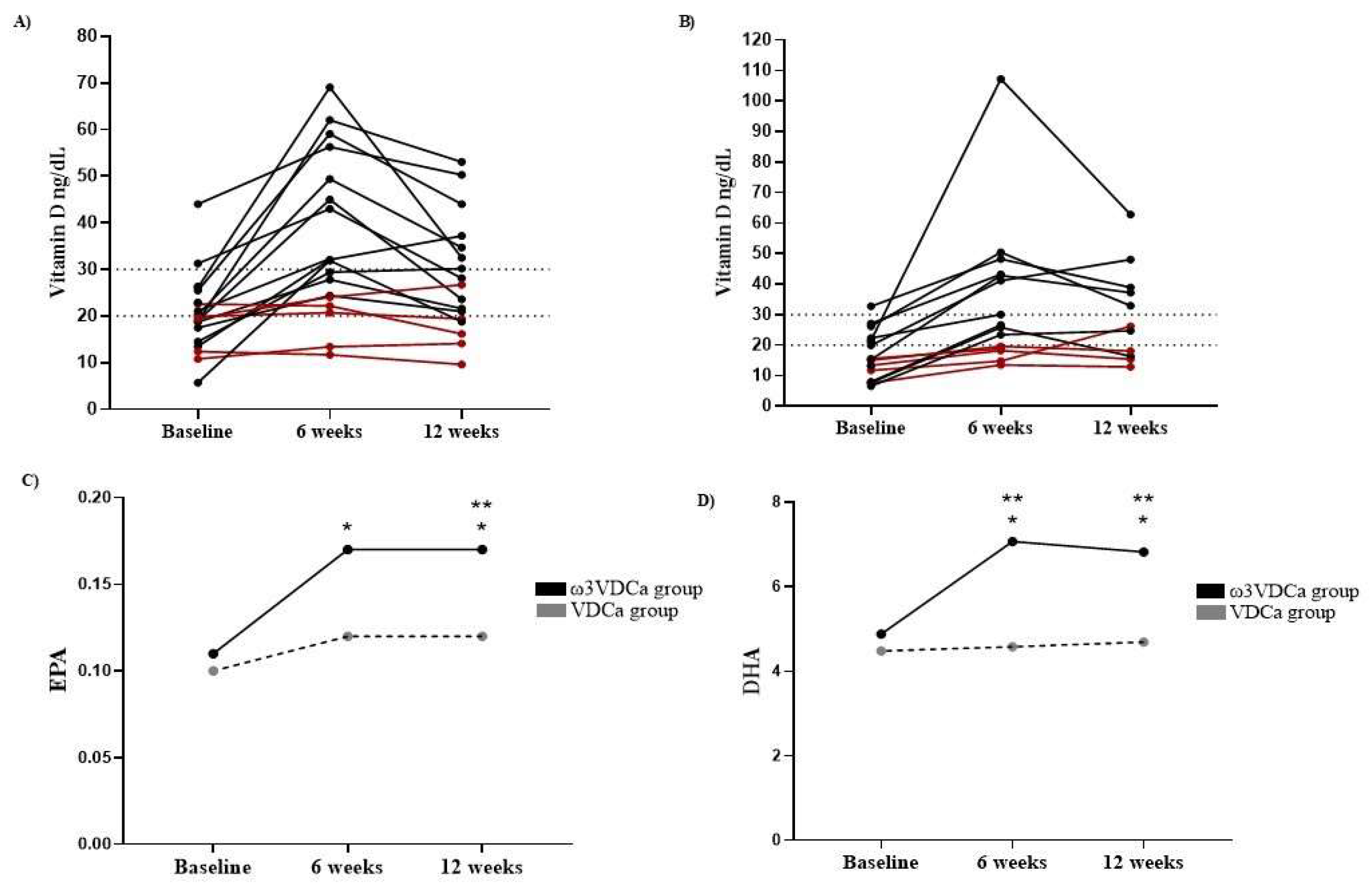

Supplementation Compliance

The children and their parents were instructed to record supplement intake (capsules and pills) in a logbook at the beginning of the intervention. Compliance was monitored by counting the leftover pills and capsules at the next appointment. Only children with an intake equal to or greater than 80% of the LCPUFAs-ω3 capsules were included. In addition, the EPA and DHA contents in erythrocytes were determined before, 6 and 12 weeks after the initiation of supplementation in order to confirm treatment adherence.

Vitamin D adherence was assessed according to changes in the vitamin D nutritional status after supplementation.

Procedures

Anthropometry

The demographic and clinical characteristics of the patients were collected during recruitment (diagnosis) and follow-up (6 and 12 weeks). Body weight (kg) and body composition were measured by impedance using an InBody 230 (InBody USA, Cerritos, CA, USA) while the patients wore lightweight clothing. Height was measured with a wall-mounted stadimeter (Seca 222, Seca Corp., Oakland Center, Columbia, MD, USA). The body mass index (BMI) was calculated as weight (kg) divided by the square of the height (m); BMI scores were obtained from the World Health Organization (WHO) normative curves [

21]. All measurements were made by a nutritionist according to the standard techniques at baseline, 6 and 12 weeks.

Analytical Methods

Peripheral blood samples at baseline, 6 and 12 weeks were collected between 8:00 and 9:00 am after an overnight fast. Clotted blood samples were centrifuged for 15 min at 3500 rpm under cold conditions (4°C). Aliquots of serum and plasma were immediately frozen (-80°C) until analysis. The serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D (25(OH)D) concentration was determined using ultra-high-performance liquid chromatography coupled to a mass spectrometer (UPLC-MS-MS). The UPLC-MS-MS equipment consisted of an ACQUITY UPLC Class H system with a photodiode array detector (PDA) and a mass spectrometer (ACQUITY QD) (Waters, Milford, MA, USA) in electrospray ionization (ESI) mode, in addition to a quaternary eluent management system. The 25(OH)D concentration status was classified according to the Endocrine Society as follows: vitamin D deficiency was defined as 25(OH)D < 20 ng/mL, vitamin D insufficiency was defined as 25(OH)D of 21–29 ng/mL, and vitamin D sufficiency was defined as 25(OH)D ≥ 30 ng/mL [

22]. The parathyroid hormone (PTH) and osteocalcin concentrations were determined using a MILLIPLEX

® Human Bone Magnetic Bead Panel (HBNMAG-51K) (Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany), with an analytical sensitivity of 1.8 pg/mL and a detection range of 5pg/mL-20,000pg/mL for PTH and an analytical sensitivity of 68.5 pg/mL and a detection range of 146pg/mL-600,000pg/mL for osteocalcin. Human tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase 5b (TRAP-5b) was assessed using a commercial kit (MBS045195; MyBiosource Inc., San Diego, CA, USA), with an analytical sensitivity of 0.1 U/L and a detection range of 0.5 U/L–16U/L. Human cross-linked C-terminal telopeptides of type I collagen (ICTP) was assessed in plasma using a commercial kit (MBS040005; MyBiosource INC., San Diego, CA, USA), with an analytical sensitivity of 0.1 ng/mL and a detection range of 0.625 ng/mL–20 ng/mL.

Serum calcium (REF. 1001060, reference values in children were 10 mg/dL–12 mg/dL), phosphorus (REF. 1001156, reference values in children were 4.0 mg/dL–7.0 mg/dL), and creatinine were measured. The calcium in urinary samples was determined by spectrophotometry (SPINREACT 120, Santa Coloma, España). Urinary samples were also obtained for calciuria measurements, which were estimated in isolated urine by determining the calcium/creatinine (Ca/Cr) ratio, expressed in mg/mg or mmol/mmol. In children older than two years, a ratio higher than 0.2 mg/mg or 0.6 mmol/mmol suggests hypercalciuria.

Fatty Acid Analyses Using Gas Chromatography

Analyses were performed with a 7820A gas chromatograph (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA) with a flame ionization detector (FID), as described previously [

14].

Evaluation of Bone Mineral Density

Bone mineral density (BMD) in the lumbar spine vertebral and total body was measured by dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA) using a GE Lunar Prodigy Advance scanner (software version 9.0; GE Medical Systems, Madison, WI, USA) at baseline only due to the short intervention duration. The parameters included the total bone mineral content (BMD) (gr/m2) and the z-score of the BMD at the lumbar spine level and total body. The BMD z-score was adjusted for height and sex. The BMD was considered normal for z-scores > -1 SD, indicative of osteopenia between –1 SD and -2 SD, and indicative of osteoporosis ≤ -2 SD [

10].

Statistical Analysis

A statistical analysis was performed using SPSS Statistics version 21.0 software (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, U.S.). The data distribution was assessed with the Shapiro‒Wilk test, with the coefficients of asymmetry (between -0.5 and + 0.5) and kurtosis (between -2 and + 2). Quantitative data are presented as the means ± standard deviations (SD) when they are normally distributed or as the medians (25th –75th percentiles). Categorical variables are presented as percentages. To analyze changes in 25-hydroxyvitamin D, osteocalcin, TRACP-5B, ICTP, PTH, calcium, and phosphorus levels during the follow-up, we used the Wilcoxon test or the paired Student’s t test according to the data distribution. The differences between groups were evaluated using Student’s t test or the Mann–Whitney U test. The association between changes in vitamin D concentrations, LCPUFAs-ω3 enrichment, and bone turnover markers concentrations was analyzed using a multiple linear regression model.

4. Discussion

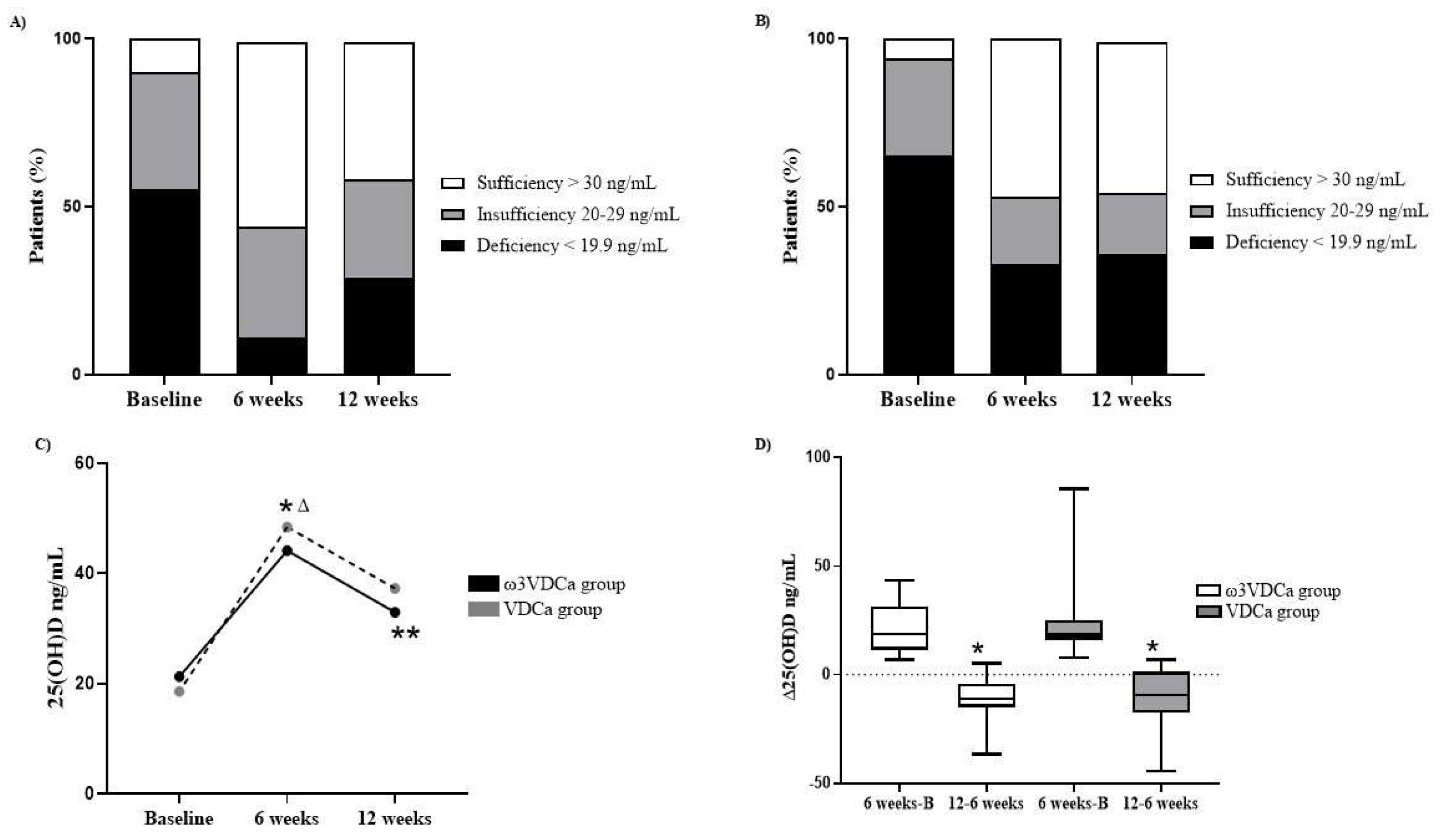

This is the first report demonstrating the effect of combined supplementation with LCPUFAs-ω3, vitamin D, and calcium for six weeks and after the intervention on 25(OH)D concentrations and bone turnover markers in pediatric patients with ALL. We confirmed a high prevalence of vitamin D insufficiency and deficiency in this population, which persisted into the maintenance phase.

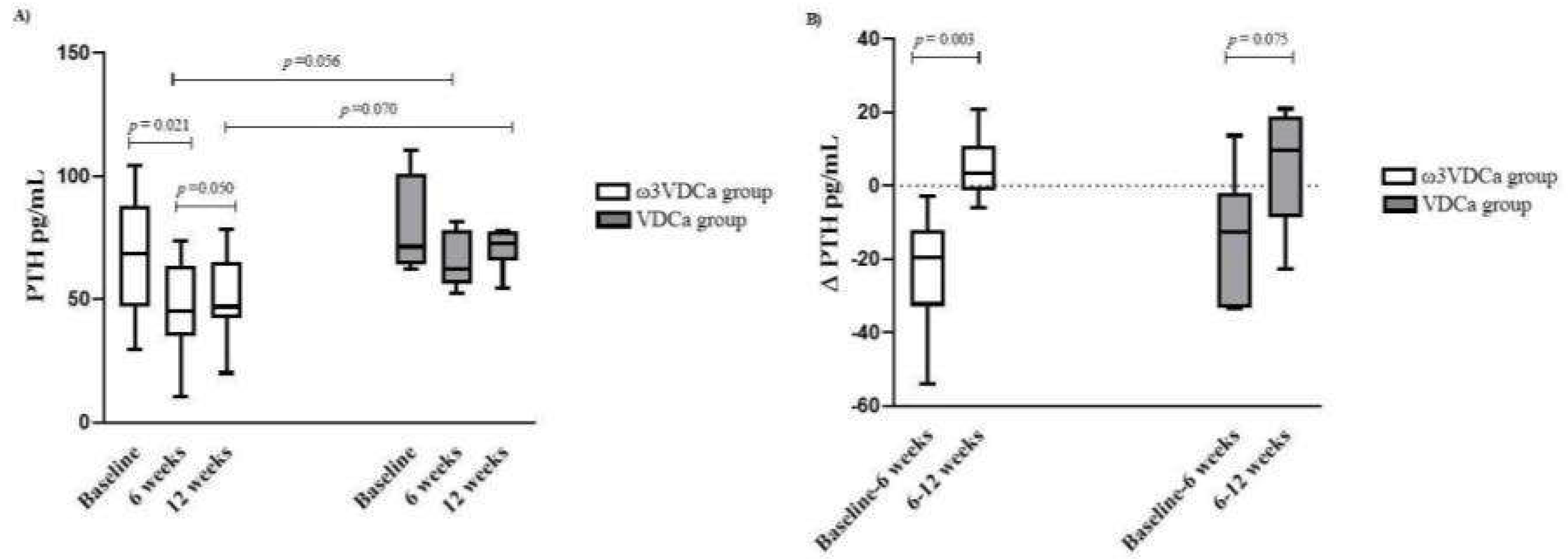

The administered dose of vitamin D was effective in increasing 25(OH)D concentrations at 6 weeks in both groups. We found that, in patients who had adequate adherence, more than 50% maintained sufficient vitamin D levels 12 weeks after receiving supplementation. LCPUFAs-ω3 did not appear to have an effect on 25(OH)D concentrations after supplementation. Similarly, during supplementation with vitamin D and omega-3, no effect was observed on bone formation and resorption markers; however, the ω3VDCa group showed a significant decrease in PTH concentrations after 6 weeks of supplementation and a trend to decrease at 6 weeks after its discontinuation. In addition, in the ω3VDCa group, ICTP concentrations decreased six weeks after discontinuing supplementation. In contrast, there were no differences between the groups in terms of the bone formation marker osteocalcin.

According to ENSANUT 2022, 4.3% and 23.3% of healthy Mexican preschoolers and schoolchildren have vitamin D deficiency [

23]; however, various studies have found that the prevalence of vitamin D deficiency is higher in pediatric patients with ALL than in healthy children [

5,

8]. The high prevalence of vitamin D deficiency in this population has led to a search for therapeutic strategies, as it is necessary to maintain adequate 25(OH)D concentrations in order to regulate calcium homeostasis and maintain bone health [

22,

23]. To date, few studies have evaluated the effect of supplementation on bone health in these patients [

9,

10,

11,

12]. Interventions have focused mainly on administering vitamin D and calcium, and only one study combined vitamin D and K [

12]. These studies reported a significant increase in 25(OH)D concentration after supplementation [

10], with an adequate tolerance of the intervention [

10,

11], thus demonstrating the effectiveness of vitamin D supplementation in improving vitamin D levels and the feasibility of integrating it into hematologic treatment [

11]. Even though all supplementation studies in these patients have focused on the remission induction phase to the intensification phase, it has been suggested that the effect of supplementation should be evaluated during the maintenance phase [

11]. However, at this treatment stage, poor adherence to chemotherapy has been observed, representing a challenge to achieving adequate adherence to supplementation [

24].

When evaluating the adherence of the total sample by counting the calcium, vitamin D, and omega-3 capsules, it was found that the patients apparently complied, with an adherence rate of 90–95%; however, when evaluating adherence based on the change in concentrations from baseline, the adherence percentage was lower (53%), which suggests that determining the changes in the concentrations of these analytes is a more reliable method for evaluating adherence. It is difficult to ensure the consumption of supplements because, in the case of pediatric patients, the parents are responsible for their intake, or, in the case of adolescents, they are responsible themselves. Additionally, as these children receive polypharmacy, it is difficult for them to adhere to the intervention due to the prolonged time of their own treatment and “pill fatigue”. Some authors have suggested strategies to improve adherence to supplementation, such as using chewable calcium tablets [

11], which we implemented in our study to ensure better adherence. Although we used this strategy, one patient in particular presented an increase of 12 ng/mL in vitamin D after supplementation had already been suspended, increasing from 14.8 ng/mL at 6 weeks to 26.2 ng/mL at 12 weeks, which could suggest that the supplements were consumed after the supplementation period ended. Some studies have reported that, for every 100 IU of vitamin D consumed, there is a replacement of 0.75 ng/mL, and it has been suggested that taking a supplement with more than 1,000 IU could ensure sufficient levels [

25]. It should be noted that the vitamin D and calcium intake in these patients was ~ 40% and 70%, respectively, which indicates that none of the patients met the recommended requirements of 400 IU of vitamin D and 1000 mg of calcium.

Previous studies administering vitamin D supplementation have demonstrated its effectiveness in increasing 25(OH)D concentrations at doses between 400 and 800 IU (9,10) or at a high dose of 100,000 IU [

11]. Although vitamin D supplementation has been recommended to prevent osteoporosis and reduce the risk of fractures, the required dose, how it should be administered, and the optimal levels of 25(OH)D required to maintain adequate bone health remain controversial [

6,

26]. Maintaining serum vitamin D levels of 40–60 ng/mL has been described as providing health benefits; to achieve these serum levels, supplementation at doses of 4,000 IU per day has been suggested in subjects at risk of vitamin D deficiency [

26,

27]. Our results showed a significant increase in 25(OH)D concentrations, with sufficient concentrations reached and even maintained 6 weeks after supplementation stopped. Although a decrease in 25(OH)D concentrations was observed when supplementation was stopped in both groups, they were still greater than those at baseline, with sufficient concentrations maintained in more than 50% of patients. In contrast, in a study by Demirsoy et al., 400–600 IU of vitamin D and 500–1000 mg of calcium were administered per day for 8 months in pediatric patients with ALL, from the remission induction phase to the intensification phase. However, despite the supplementation duration, the patients did not reach sufficient vitamin D concentrations, possibly due to the low dose administered [

10]. Conversely, in studies carried out by Orgel et al. and Kaste et al., 100,000 IU and 800 IU of vitamin D were administered, respectively, for a longer period (6 months and 2 years), and the patients managed to reach sufficient concentrations [

9,

11]. However, in our study, we administered a dose of 4,000 IU for 6 weeks, and the patients managed to reach these values in a shorter time than that reported by these authors.

Studies have suggested that omega-3 fatty acid supplementation acts on the metabolism of vitamin D, increasing its concentration. Partan et al. conducted a study in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus in which they administered 500 uL of seluang fish oil (n=16) or a placebo (n=16) for 90 days. The authors reported a significant increase in serum vitamin D concentrations in the intervention group, from 44.8 to 89.8 ng/mL, while there were no significant differences in the placebo group. This increase can probably be attributed to the fact that seluang fish is characterized by its omega-3 and vitamin D content [

28]. However, Salari et al. administered a supplement with 2,700 mg of omega-3 fatty acids to postmenopausal women with osteoporosis for 6 months and included a placebo group. They reported a significant increase in vitamin D concentrations at 2 and 6 months of supplementation in both groups; however, this effect was not attributed to omega-3 because both groups showed an increase in vitamin D [

29]. Likewise, in our study, we did not find any effect of omega-3 on serum 25(OH)D concentrations, as both groups showed an increase at the end of the 6 week supplementation period; however, in the ω3VDCa group, there was a significant decrease in 25(OH)D concentration when supplementation was discontinued compared to the VDCa group, where there were no changes. The difference observed at 12 weeks could be partly explained by the sample size.

In mammals, the de novo synthesis of PTH is regulated in response to alterations in serum calcium, phosphorus, and vitamin D concentrations [

30]. A persistent vitamin D deficiency decreases calcium and phosphorus absorption, activating an acute compensatory mechanism by PTH for the release of calcium through an increase in bone resorption, causing a decrease in BMD and mineralization defects [

31], and a decrease in PTH concentration reflects an increase in vitamin D concentration. At the end of supplementation, we found that the ω3VDCa group showed a significant decrease in PTH concentration, reaching a normal level, and, at 6 weeks, PTH tended to be lower than that in the VDCa group (p=0.056). When supplementation was discontinued, both groups showed an increase in PTH concentration; however, at 12 weeks, the ω3VDCa group tended to maintain a lower concentration than the VDCa group (p=0.070). This result is consistent with that reported by Hutchins-Wiese et al. In their study, they evaluated the effect of supplementation with 800 IU of vitamin D, 1000 mg of calcium, and 4 g of EPA + DHA (2,520 mg of EPA and 1,680 mg of DHA) in postmenopausal women who survived breast cancer (n=17) and a control group that received the same doses of vitamin D and calcium for 3 months (n=17). They also observed a significant decrease in PTH concentrations at the end of supplementation compared to those at baseline in the group that received EPA + DHA [

32]. Even when they administered a higher dose of omega-3 and a lower dose of vitamin D, the effects that they observed were the same as those that we observed regarding the PTH concentrations at 6 weeks (1.5 months), with these effects maintained for another 6 weeks without supplementation; furthermore, our follow-up time was the same as that reported by Hutchins-Wiese.

Bone remodeling is a continuous process involving both bone resorption and formation [

33], during which markers of bone resorption (products of type I collagen degradation) and formation (osteoblastic enzymes) are produced [

34]. Prostaglandin E2 and proinflammatory cytokines, such as TNF-α, IL-1, and IL-6, induce bone resorption by activating osteoclasts and osteoclastogenesis [

35]. In a previous study conducted by our team, we demonstrated a high prevalence of vitamin D deficiency at diagnosis in this population, combined with alterations in bone metabolism, such as an increase in RANKL and a decrease in OPG concentration, which indicates that these patients experience increased bone resorption [

5]. In the search for a nutritional intervention that can influence bone metabolism, the use of nutritional supplements such as vitamin D, calcium, and, more recently, LCPUFAs-ω3 [

33], has been suggested. Due to their anti-inflammatory properties, omega-3 fatty acids have been shown to inhibit osteoclastogenesis, increase osteoblastogenesis and calcium absorption, and decrease proinflammatory cytokines and prostaglandin E2 [

13,

32,

35].

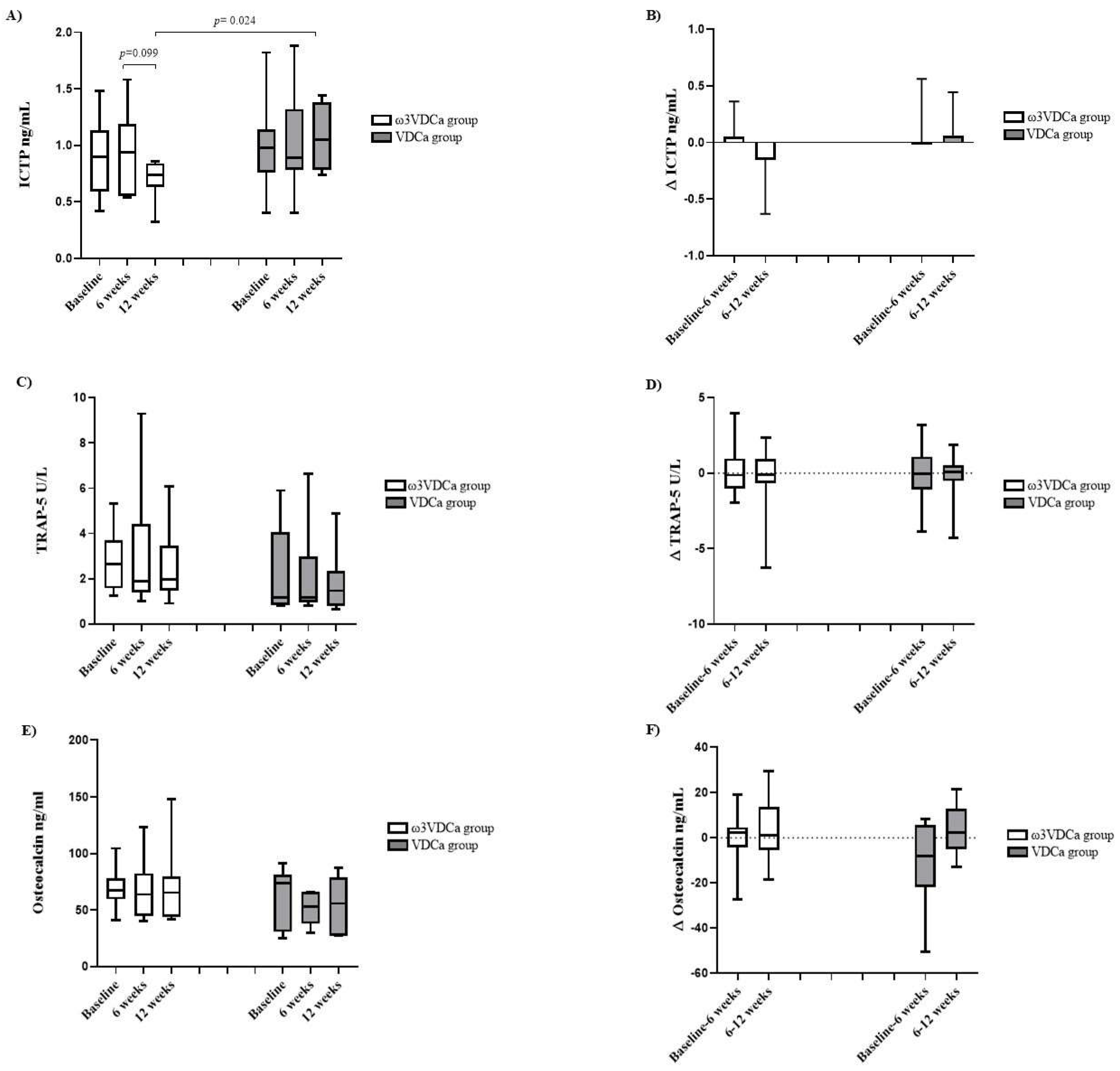

Regarding the bone resorption marker ICTP at 12 weeks after completing supplementation, the ω3VDCa group presented significantly lower concentrations than the VDCa group (p=0.024). LCPUFAs-ω3 have been shown to have an effect on bone resorption markers, in accordance with what was reported by Hutchins-Wiese et al., who also observed a decrease in ICTP concentrations between the LCPUFAs-ω3 intervention group and the placebo group in postmenopausal women who survived breast cancer [

32]. However, there was no follow-up in patients to determine how long after supplementation this bone resorption marker continued to decrease. Similarly, in patients with osteopenia, Vanlint et al. administered supplementation with 400 mg of DHA, 1200 mg of calcium, and 1000 IU of vitamin D daily for 12 months, with a placebo group that received corn oil plus the same doses of calcium and vitamin D (36 women and 4 men). The authors reported a decrease in ICTP at 12 months of supplementation compared to baseline in the group that received DHA; however, they reported no other differences between the groups [

36]. Conversely, our linear regression analysis showed a positive effect of DHA on bone metabolism, reflected in a decrease in ICTP concentration at 12 weeks, which could be explained by the fact that DHA-derived resolvin D1 and neuroprotectin D1 inhibit osteoclastogenesis due to their anti-inflammatory properties [

13].

We did not observe changes in osteocalcin and TRAP-5b concentrations during or after supplementation. Our results are consistent with those of previous studies conducted by Solmaz and Salari [

12,

29]. Solmaz et al. administered supplementation with 10 mcg of vitamin D and 100 mcg of vitamin K for 6 months (n=15), alongside a control group that received only standard treatment (n=14), and they did not observe any changes in TRAP-5b concentrations during follow-up [

12]. Furthermore, Salari et al. administered supplementation with fatty acids for 6 months, and they did not find changes in osteocalcin concentrations [

29]. To date, intervention studies have suggested that LCPUFAs-ω3 only decrease resorption markers without having any effect on bone formation [

29,

32,

36].

This is the first study to report the effects of omega-3, vitamin D, and calcium supplementation on bone metabolism in pediatric patients with ALL, as well as the follow-up of a cohort of patients who received supplementation. The main strengths of our study are that it allows us to begin developing guidelines for the timing of supplementation and the monitoring of 25(OH)D nutritional status, as well as assessing the duration of an intervention’s effects after it is completed. Additionally, in this study, we used the gold standard method (ultra-high-performance liquid chromatography coupled to a mass spectrometer) to quantify 25(OH)D concentrations. In addition to quantifying the concentrations of vitamin D, we also estimated its intake during the supplementation period. Nevertheless, this work has limitations, such as a small sample size due to the lack of adherence to supplementation; a lack of measurement of other markers, in addition to those reported, such as ionic calcium, RANK, RANKL, and OPG; and no long-term follow-up of bone densitometry.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.B.C and S.B.M.M; data curation L.B.C, S.B.M.M, and M.M.A; format analysis, L.B.C, S.B.M.M, M.M.A and S.A.M; funding acquisition L.B.C; investigation L.B.C, S.B.M.M, M.M.A, J.A.M.T, S.A.M., E.J.A., F.I.M.B., V.M.C.B., A.V.H.B, K.A.S.L, J.M.H, B.A.B.M, A.J.M, Z.H.P, J.M.D.S; J.V.M and I.D.C; methodology S.B.M.M; V.M.C.B; E.J.A; A.V.H.B; J.M.D.S, K.A.S.L, A.J.M, Z.H.P, J.M.H, B.A.B.M, J.A.M.T, J.V.M, and I.D.C; project administration L.B.C; resources, L.B.C, J.A,M.T., K.A.S.L, B.A.B.M, A.J.M, and Z.H.P; software S.B.M.M, E.J.A, F.I.M.B, V.M.C.B and A.V.H.B; supervision L.B.C; validation S.B.M.M, M.M.A, E.J.A, F.I.M.B,V.M.C.B, A.V.H.B., J.M.H., J.M.D.S, J.V.M and I.D.C; visualization S.B.M.M and M.M.A; writing + original draft L.B.C, S.B.M.M, M.M.A and S.A.M; writing + review & editing, L.B.C, S.B.M.M, M.M.A, J.A.M.T, S.A.M., E.J.A., F.I.M.B., V.M.C.B., A.V.H.B, K.A.S.L, J.M.H, B.A.B.M, A.J.M, Z.H.P, J.M.D.S; J.V.M and I.D.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.