Submitted:

09 June 2025

Posted:

13 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

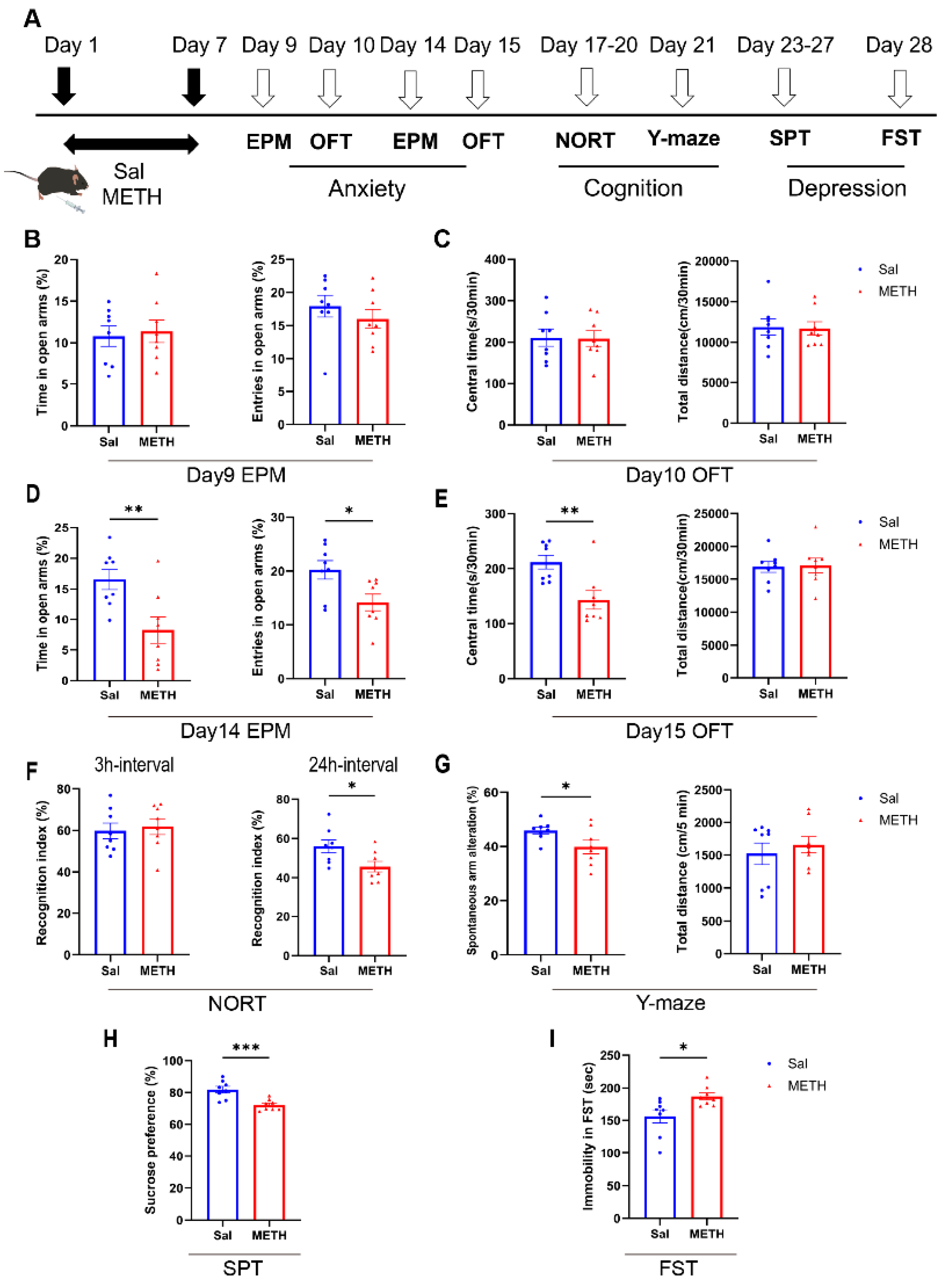

2.1. METH Withdrawal Induces Anxiety and Depressive-Like Behaviors, as Well as Cognitive Deficits

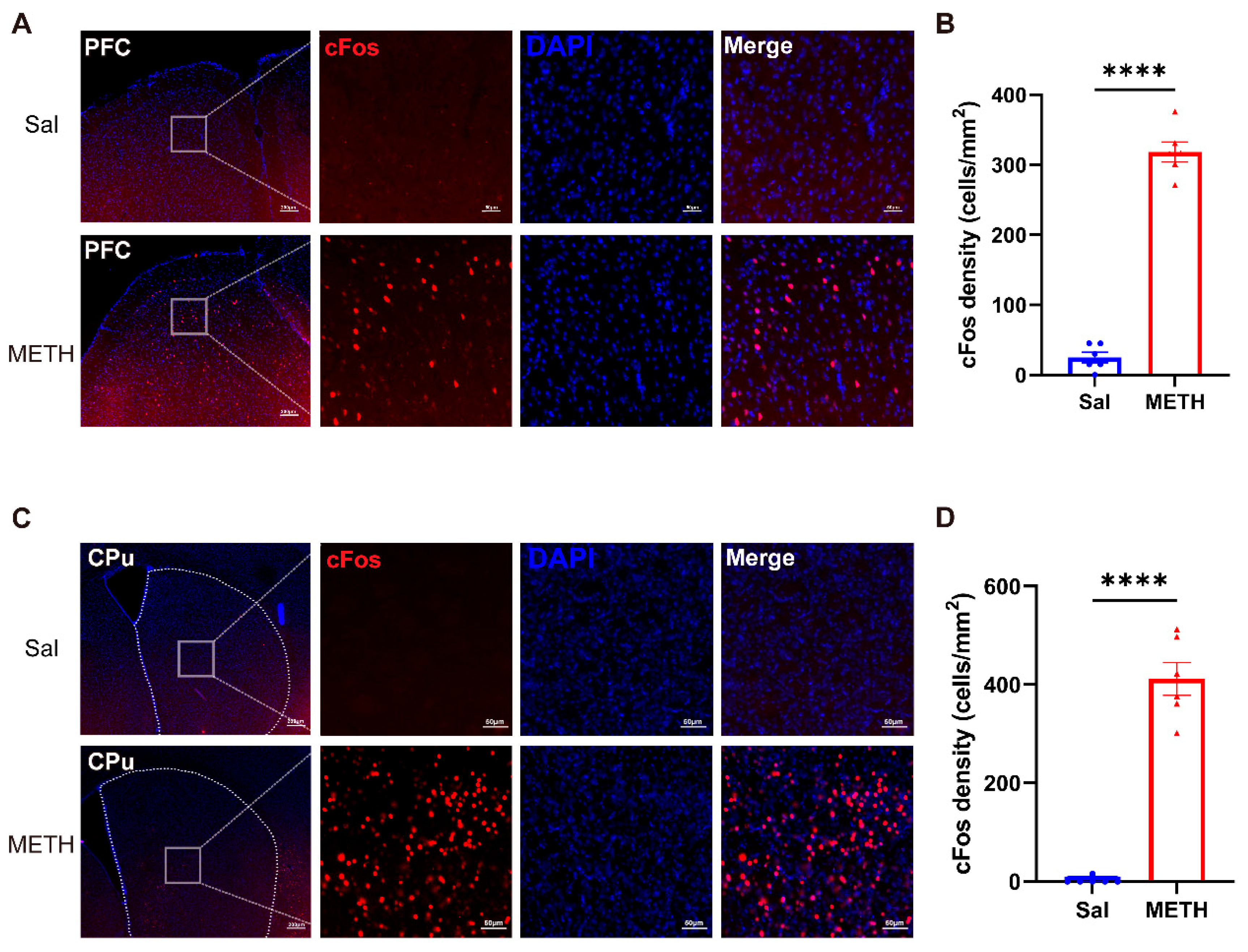

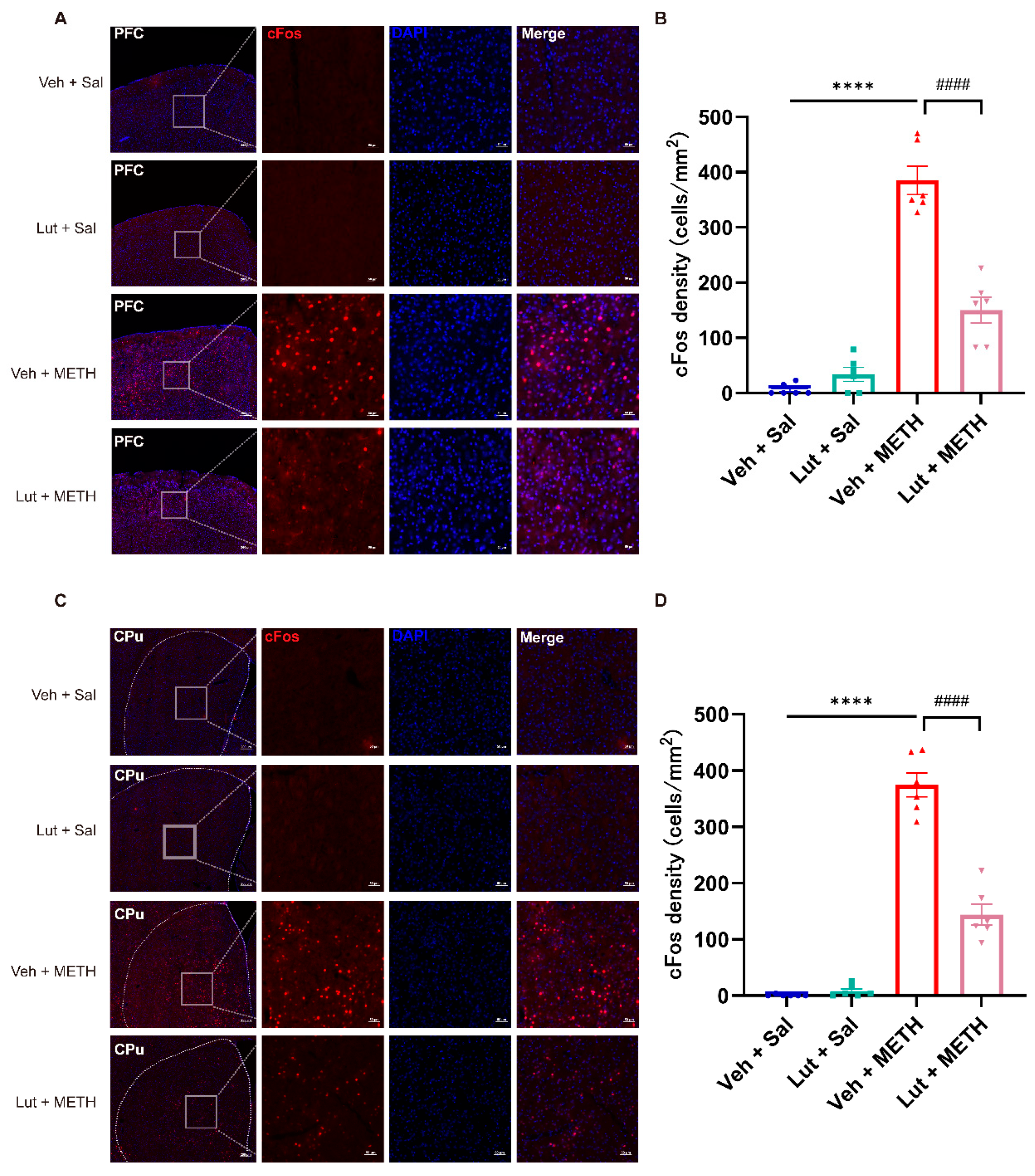

2.2. METH Withdrawal Increases the Neuronal Activity in the PFC and CPu

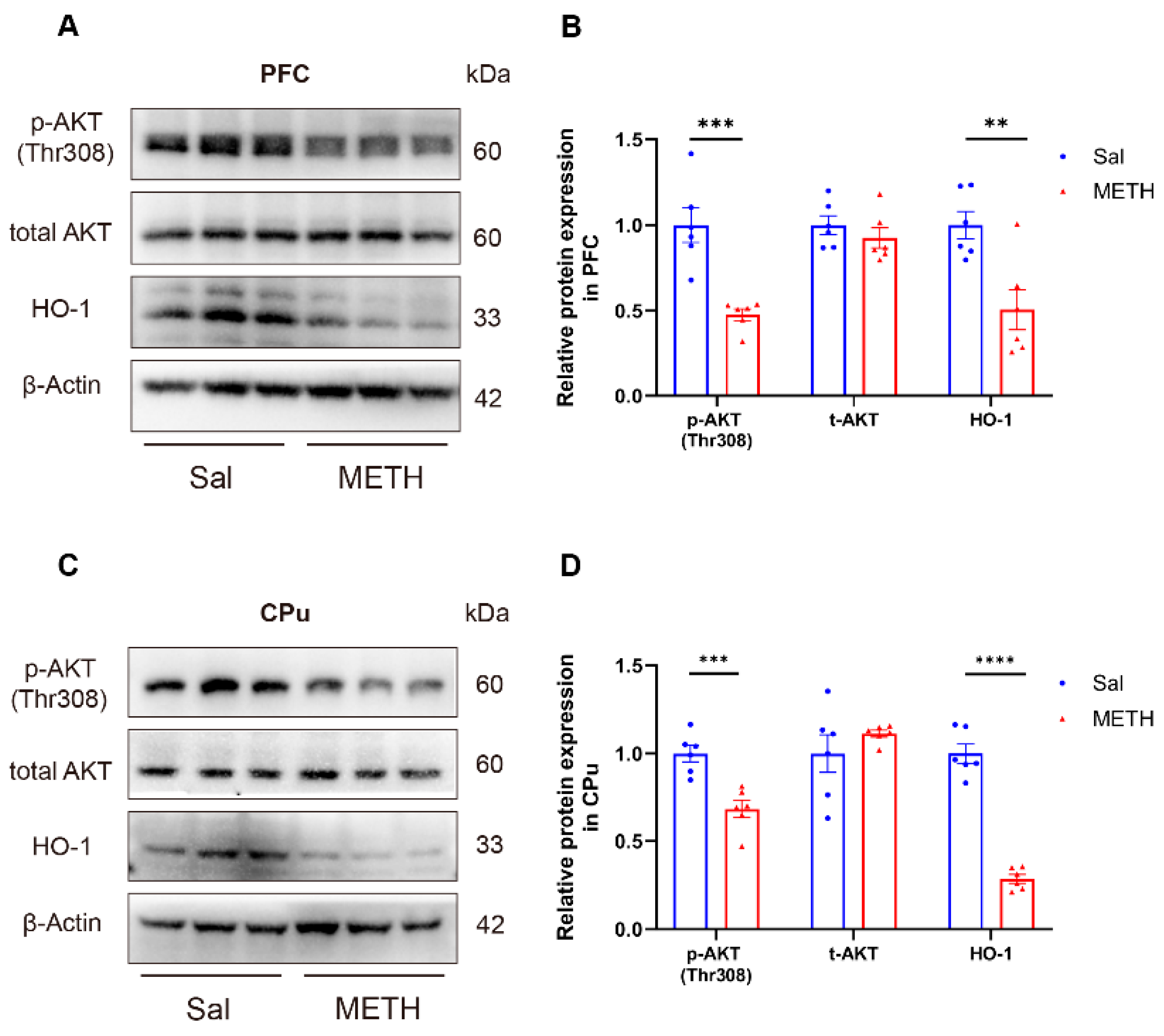

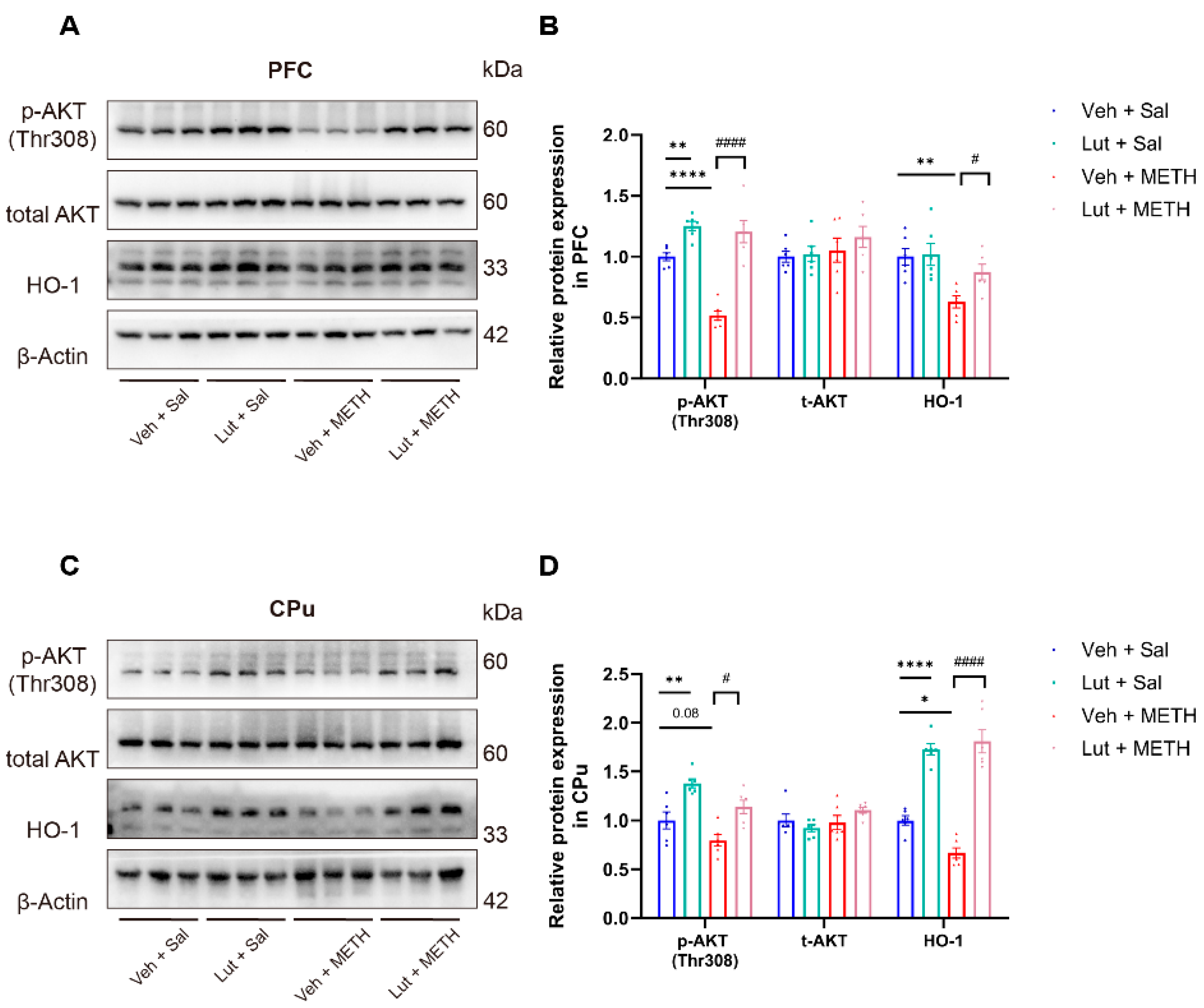

2.3. METH Withdrawal Downregulates p-AKT and HO-1 Expression in the PFC and CPu

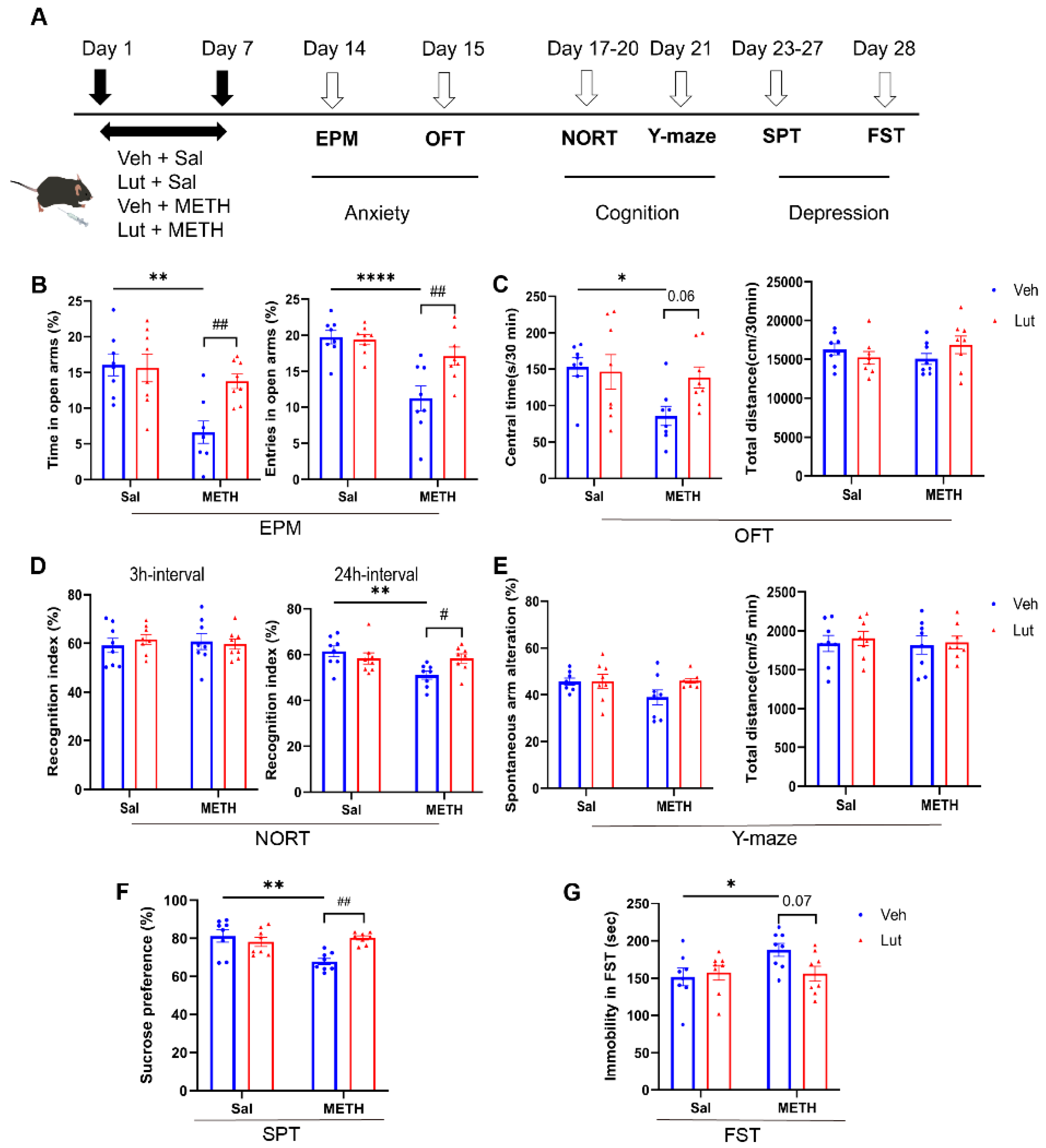

2.4. Luteolin Pretreatment Potentially Alleviates METH Withdrawal-Induced Anxiety and Depressive-Like Behaviors, as Well as Cognitive Deficits

2.5. Luteolin Attenuates METH Withdrawal-Induced Abnormal Activation of Neurons in the PFC and CPu

2.6. Luteolin Prevents METH Withdrawal-Induced Downregulation of p-AKT and HO-1 Expression in the PFC and CPu

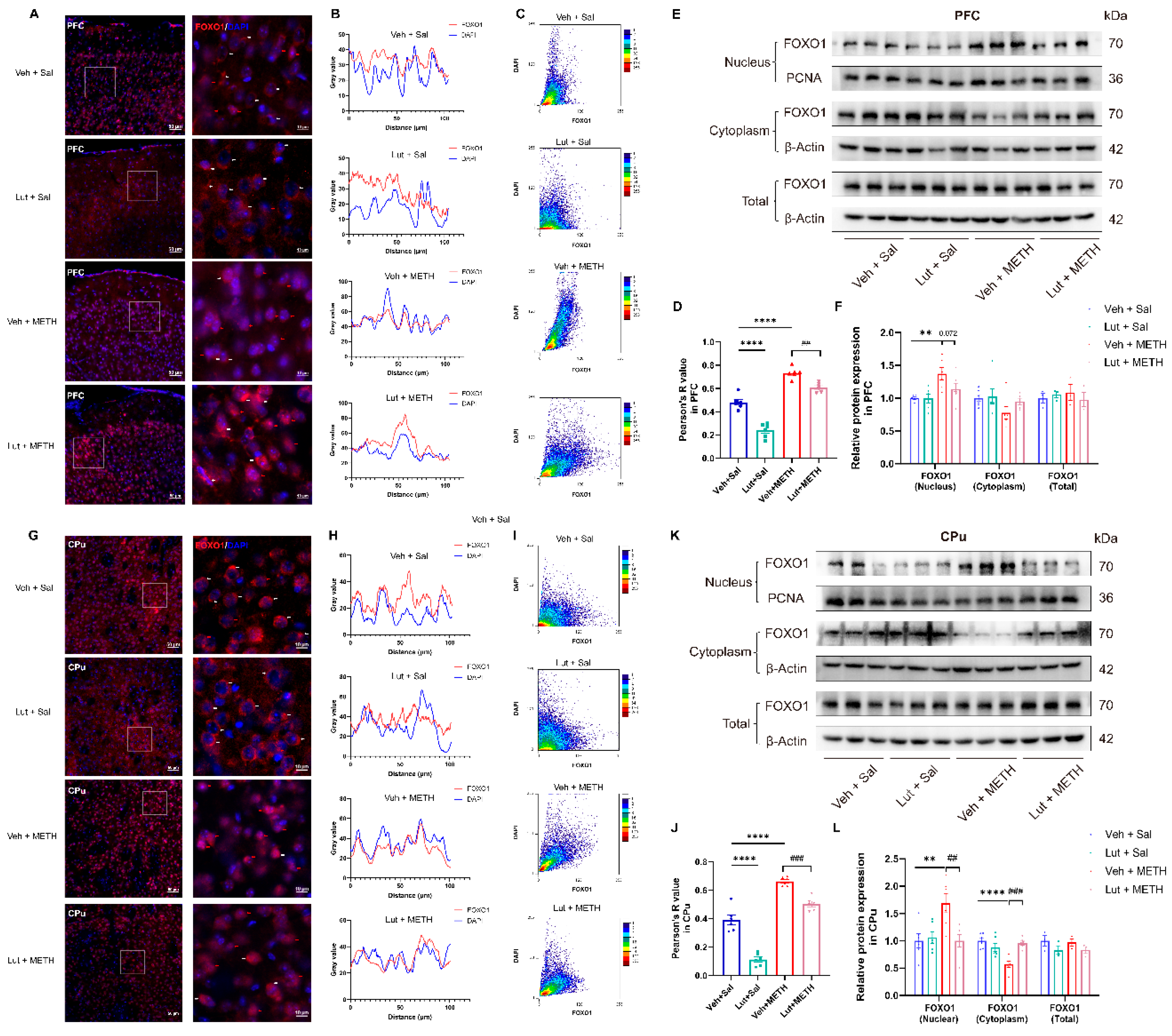

2.7. Luteolin Inhibits METH Withdrawal-Induced Nuclear Translocation of FOXO1

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Animals

4.2. Reagents and Drug Administration Procedure

4.3. Behavioral Tests

4.3.1. Anxiety-Like Behaviors

4.3.2. Cognitive Function Detection

4.3.3. Depressive-Like Behaviors

4.4. Sample Preparation and Western Blotting

4.5. Sample Preparation and Immunofluorescence

4.6. Statistical Analysis

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| BBB | blood-brain barrier |

| PFC | prefrontal cortex |

| CPu | caudate putamen |

| AKT | protein kinase B |

| FOXO1 | forkhead box protein 1 |

| HO-1 | heme-oxygenase-1 |

| PI3K | phosphoinositide 3-kinase |

| EPM | elevated plus maze |

| OFT | open field test |

| NORT | novel object recognition task |

| SPT | sucrose preference test |

| FST | forced swim test |

References

- Zhang B, Yan X, Li Y, Zhu H, Lu Z, Jia Z: Trends in Methamphetamine Use in the Mainland of China, 2006-2015. Frontiers In Public Health 2022, 10:852837.

- Pang L, Wang Y: Overview of blood-brain barrier dysfunction in methamphetamine abuse. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy = Biomedecine & Pharmacotherapie 2023, 161:114478.

- Zhao X, Lu J, Chen X, Gao Z, Zhang C, Chen C, Qiao D, Wang H: Methamphetamine exposure induces neuronal programmed necrosis by activating the receptor-interacting protein kinase 3 -related signalling pathway. Faseb j 2021, 35:e21561. [CrossRef]

- Bellot M, Soria F, López-Arnau R, Gómez-Canela C, Barata C: Daphnia magna an emerging environmental model of neuro and cardiotoxicity of illicit drugs. Environ Pollut 2024, 344:123355. [CrossRef]

- Wang X, Hui R, Li Q, Lu Y, Wang M, Shi Y, Xie B, Cong B, Ma C, Wen D: Gut microbiota-derived trimethylamine N-oxide involved in methamphetamine-induced depression-like behaviors of male mice. Neuropharmacology 2025, 268:110339. [CrossRef]

- Hui R, Xu J, Zhou M, Xie B, Zhou M, Zhang L, Cong B, Ma C, Wen D: Betaine improves METH-induced depressive-like behavior and cognitive impairment by alleviating neuroinflammation via NLRP3 inflammasome inhibition. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry 2024, 135:111093. [CrossRef]

- Wang X, Hu M, Chen J, Lou X, Zhang H, Li M, Cheng J, Ma T, Xiong J, Gao R, et al: Key roles of autophagosome/endosome maturation mediated by Syntaxin17 in methamphetamine-induced neuronal damage in mice. Mol Med 2024, 30:4. [CrossRef]

- Wang X, Hu M, Wu W, Lou X, Gao R, Ma T, Dheen ST, Cheng J, Xiong J, Chen X, Wang J: Indole derivatives ameliorated the methamphetamine-induced depression and anxiety via aryl hydrocarbon receptor along “microbiota-brain” axis. Gut Microbes 2025, 17:2470386. [CrossRef]

- Zhang K, Chen L, Yang J, Liu J, Li J, Liu Y, Li X, Chen L, Hsu C, Zeng J, et al: Gut microbiota-derived short-chain fatty acids ameliorate methamphetamine-induced depression- and anxiety-like behaviors in a Sigmar-1 receptor-dependent manner. Acta Pharm Sin B 2023, 13:4801-4822. [CrossRef]

- Ma J, Sun XJ, Wang RJ, Wang TY, Su MF, Liu MX, Li SX, Han Y, Meng SQ, Wu P, et al: Profile of psychiatric symptoms in methamphetamine users in China: Greater risk of psychiatric symptoms with a longer duration of use. Psychiatry Res 2018, 262:184-192. [CrossRef]

- Zhang J, Xie Y, Su H, Tao J, Sun Y, Li L, Liang H, He R, Han B, Lu Y, et al: Prevalence and correlates of depressive symptoms during early methamphetamine withdrawal in Han Chinese population. Drug Alcohol Depend 2014, 142:191-196. [CrossRef]

- Pratelli M, Hakimi AM, Thaker A, Jang H, Li HQ, Godavarthi SK, Lim BK, Spitzer NC: Drug-induced change in transmitter identity is a shared mechanism generating cognitive deficits. Nat Commun 2024, 15:8260. [CrossRef]

- Shilling PD, Kuczenski R, Segal DS, Barrett TB, Kelsoe JR: Differential regulation of immediate-early gene expression in the prefrontal cortex of rats with a high vs low behavioral response to methamphetamine. Neuropsychopharmacology 2006, 31:2359-2367. [CrossRef]

- Li J, Zhu L, Su H, Liu D, Yan Z, Ni T, Wei H, Goh ELK, Chen T: Regulation of miR-128 in the nucleus accumbens affects methamphetamine-induced behavioral sensitization by modulating proteins involved in neuroplasticity. Addict Biol 2021, 26:e12881. [CrossRef]

- Vilca SJ, Margetts AV, Höglund L, Fleites I, Bystrom LL, Pollock TA, Bourgain-Guglielmetti F, Wahlestedt C, Tuesta LM: Microglia contribute to methamphetamine reinforcement and reflect persistent transcriptional and morphological adaptations to the drug. Brain Behav Immun 2024, 120:339-351. [CrossRef]

- Wang Y, Liu J, Yue S, Chen L, Singh A, Yu T, Calipari ES, Wang ZJ: Prefrontal cortex excitatory neurons show distinct response to heroin-associated cue and social stimulus after prolonged heroin abstinence in mice. Neuropsychopharmacology 2025. [CrossRef]

- Ding J, Huang J, Tang X, Shen L, Hu S, He J, Liu T, Yu Z, Liu Y, Wang Q, et al: Low and high dose methamphetamine differentially regulate synaptic structural plasticity in cortex and hippocampus. Front Cell Neurosci 2022, 16:1003617. [CrossRef]

- Hu YB, Deng X, Liu L, Cao CC, Su YW, Gao ZJ, Cheng X, Kong D, Li Q, Shi YW, et al: Distinct roles of excitatory and inhibitory neurons in the medial prefrontal cortex in the expression and reconsolidation of methamphetamine-associated memory in male mice. Neuropsychopharmacology 2024, 49:1827-1838. [CrossRef]

- Liu M, Mu S, Han W, Tan X, Liu E, Hang Z, Zhu S, Yue Q, Sun J: Dopamine D1 receptor in orbitofrontal cortex to dorsal striatum pathway modulates methamphetamine addiction. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2023, 671:96-104. [CrossRef]

- Barbano MF, Qi J, Chen E, Mohammad U, Espinoza O, Candido M, Wang H, Liu B, Hahn S, Vautier F, Morales M: VTA glutamatergic projections to the nucleus accumbens suppress psychostimulant-seeking behavior. Neuropsychopharmacology 2024, 49:1905-1915. [CrossRef]

- Wang M, Xu L, Zhao D, Wang W, Xu L, Cao Y, Meng F, Liu J, Li C, Jiang S: The glutamatergic projections from the PVT to mPFC govern methamphetamine-induced conditional place preference behaviors in mice. J Affect Disord 2025, 371:289-304. [CrossRef]

- Chen T, Su H, Li R, Jiang H, Li X, Wu Q, Tan H, Zhang J, Zhong N, Du J, et al: The exploration of optimized protocol for repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation in the treatment of methamphetamine use disorder: A randomized sham-controlled study. EBioMedicine 2020, 60:103027. [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee D, Gonzales BJ, Ashwal-Fluss R, Turm H, Groysman M, Citri A: Egr2 induction in spiny projection neurons of the ventrolateral striatum contributes to cocaine place preference in mice. Elife 2021, 10. [CrossRef]

- Wei T, Li JD, Wang YJ, Zhao W, Duan F, Wang Y, Xia LL, Jiang ZB, Song X, Zhu YQ, et al: p-Nrf2/HO-1 Pathway Involved in Methamphetamine-induced Executive Dysfunction through Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress and Apoptosis in the Dorsal Striatum. Neurotox Res 2023, 41:446-458.

- Meng X, Zhang C, Guo Y, Han Y, Wang C, Chu H, Kong L, Ma H: TBHQ Attenuates Neurotoxicity Induced by Methamphetamine in the VTA through the Nrf2/HO-1 and PI3K/AKT Signaling Pathways. Oxid Med Cell Longev 2020, 2020:8787156.

- Yang W, Li Y, Tang Y, Tao Z, Yu M, Sun C, Ye Y, Xu B, Zhao X, Zhang Y, Lu X: Mesenchymal stem cells overexpressing neuropeptide S promote the recovery of rats with spinal cord injury by activating the PI3K/AKT/GSK3β signaling pathway. Stem Cell Res Ther 2025, 16:100.

- Wang L, Chen Y, Sternberg P, Cai J: Essential roles of the PI3 kinase/Akt pathway in regulating Nrf2-dependent antioxidant functions in the RPE. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2008, 49:1671-1678. [CrossRef]

- Deng S, Jin P, Sherchan P, Liu S, Cui Y, Huang L, Zhang JH, Gong Y, Tang J: Recombinant CCL17-dependent CCR4 activation alleviates neuroinflammation and neuronal apoptosis through the PI3K/AKT/Foxo1 signaling pathway after ICH in mice. J Neuroinflammation 2021, 18:62.

- Nageswaran V, Carreras A, Reinshagen L, Beck KR, Steinfeldt J, Henricsson M, Ramezani Rad P, Peters L, Strässler ET, Lim J, et al: Gut Microbial Metabolite Imidazole Propionate Impairs Endothelial Cell Function and Promotes the Development of Atherosclerosis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2025. [CrossRef]

- Koppula S, Wankhede NL, Sammeta SS, Shende PV, Pawar RS, Chimthanawala N, Umare MD, Taksande BG, Upaganlawar AB, Umekar MJ, et al: Modulation of cholesterol metabolism with Phytoremedies in Alzheimer’s disease: A comprehensive review. Ageing Res Rev 2024, 99:102389.

- Singh AA, Katiyar S, Song M: Phytochemicals Targeting BDNF Signaling for Treating Neurological Disorders. Brain Sci 2025, 15.

- Ma HY, Wang J, Wang J, Guo Z, Qin XY, Lan R, Hu Y: Luteolin attenuates cadmium neurotoxicity by suppressing glial inflammation and supporting neuronal survival. Int Immunopharmacol 2025, 152:114406. [CrossRef]

- Li H, Li JX, Zeng YD, Zheng CX, Dai SS, Yi J, Song XD, Liu T, Liu WH: Luteolin ameliorates ischemic/reperfusion injury by inhibiting ferroptosis. Metab Brain Dis 2025, 40:159.

- Luo S, Li H, Mo Z, Lei J, Zhu L, Huang Y, Fu R, Li C, Huang Y, Liu K, et al: Connectivity map identifies luteolin as a treatment option of ischemic stroke by inhibiting MMP9 and activation of the PI3K/Akt signaling pathway. Exp Mol Med 2019, 51:1-11.

- Wang Z, Zeng M, Wang Z, Qin F, Chen J, He Z: Dietary Luteolin: A Narrative Review Focusing on Its Pharmacokinetic Properties and Effects on Glycolipid Metabolism. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry 2021, 69:1441-1454. [CrossRef]

- Kempuraj D, Thangavel R, Kempuraj DD, Ahmed ME, Selvakumar GP, Raikwar SP, Zaheer SA, Iyer SS, Govindarajan R, Chandrasekaran PN, Zaheer A: Neuroprotective effects of flavone luteolin in neuroinflammation and neurotrauma. BioFactors (Oxford, England) 2021, 47:190-197. [CrossRef]

- Jiang P, Sun J, Zhou X, Lu L, Li L, Xu J, Huang X, Li J, Gong Q: Dynamics of intrinsic whole-brain functional connectivity in abstinent males with methamphetamine use disorder. Drug Alcohol Depend Rep 2022, 3:100065. [CrossRef]

- Moulis L, Le SM, Hai VV, Huong DT, Minh KP, Oanh KTH, Rapoud D, Quillet C, Thi TTN, Vallo R, et al: Gender, homelessness, hospitalization and methamphetamine use fuel depression among people who inject drugs: implications for innovative prevention and care strategies. Front Psychiatry 2023, 14:1233844.

- Gooijers J, Pauwels L, Hehl M, Seer C, Cuypers K, Swinnen SP: Aging, brain plasticity, and motor learning. Ageing Res Rev 2024, 102:102569.

- Wang Y, Guo R, Chen B, Rahman T, Cai L, Li Y, Dong Y, Tseng GC, Fang J, Seney ML, Huang YH: Cocaine-induced neural adaptations in the lateral hypothalamic melanin-concentrating hormone neurons and the role in regulating rapid eye movement sleep after withdrawal. Mol Psychiatry 2021, 26:3152-3168. [CrossRef]

- Tanaka T, Ago Y, Umehara C, Imoto E, Hasebe S, Hashimoto H, Takuma K, Matsuda T: Role of Prefrontal Serotonergic and Dopaminergic Systems in Encounter-Induced Hyperactivity in Methamphetamine-Sensitized Mice. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol 2017, 20:410-421. [CrossRef]

- Li X, Xu X, Feng Q, Zhou N, He Y, Liu Y, Tai H, Kim HY, Fan Y, Guan X: Glutamatergic pathways from medial prefrontal cortex to paraventricular nucleus of thalamus contribute to the methamphetamine-induced conditioned place preference without affecting wakefulness. Theranostics 2025, 15:1822-1841. [CrossRef]

- Oladapo A, Deshetty UM, Callen S, Buch S, Periyasamy P: Single-Cell RNA-Seq Uncovers Robust Glial Cell Transcriptional Changes in Methamphetamine-Administered Mice. Int J Mol Sci 2025, 26. [CrossRef]

- Yin Y, Mu F, Zhang L, Zhao J, Gong R, Yin Y, Zheng L, Du Y, Jin F, Wang J: Wedelolactone activates the PI3K/AKT/NRF2 and SLC7A11/GPX4 signalling pathways to alleviate oxidative stress and ferroptosis and improve sepsis-induced liver injury. J Ethnopharmacol 2025, 344:119557.

- Shen S, Zhang M, Ma M, Rasam S, Poulsen D, Qu J: Potential Neuroprotective Mechanisms of Methamphetamine Treatment in Traumatic Brain Injury Defined by Large-Scale IonStar-Based Quantitative Proteomics. Int J Mol Sci 2021, 22.

- Yu H, Peng Y, Dong W, Shen B, Yang G, Nie Q, Tian Y, Qin L, Song C, Chen B, et al: Nrf2 attenuates methamphetamine-induced myocardial injury by regulating oxidative stress and apoptosis in mice. Hum Exp Toxicol 2023, 42:9603271231219488. [CrossRef]

- Yuan J, Zhang K, Yang L, Cheng X, Chen J, Guo X, Cao H, Zhang C, Xing C, Hu G, Zhuang Y: Luteolin attenuates LPS-induced damage in IPEC-J2 cells by enhancing mitophagy via AMPK signaling pathway activation. Front Nutr 2025, 12:1552890. [CrossRef]

- Zhan XZ, Bo YW, Zhang Y, Zhang HD, Shang ZH, Yu H, Chen XL, Kong XT, Zhao WZ, Teimonen T, et al: Luteolin inhibits diffuse large B-cell lymphoma cell growth through the JAK2/STAT3 signaling pathway. Front Pharmacol 2025, 16:1545779.

- Yang S, Duan H, Yan Z, Xue C, Niu T, Cheng W, Zhang Y, Zhao X, Hu J, Zhang L: Luteolin Alleviates Ulcerative Colitis in Mice by Modulating Gut Microbiota and Plasma Metabolism. Nutrients 2025, 17. [CrossRef]

- Mahwish, Imran M, Naeem H, Hussain M, Alsagaby SA, Al Abdulmonem W, Mujtaba A, Abdelgawad MA, Ghoneim MM, El-Ghorab AH, et al: Antioxidative and Anticancer Potential of Luteolin: A Comprehensive Approach Against Wide Range of Human Malignancies. Food Sci Nutr 2025, 13:e4682. [CrossRef]

- Kempuraj D, Thangavel R, Kempuraj DD, Ahmed ME, Selvakumar GP, Raikwar SP, Zaheer SA, Iyer SS, Govindarajan R, Chandrasekaran PN, Zaheer A: Neuroprotective effects of flavone luteolin in neuroinflammation and neurotrauma. Biofactors 2021, 47:190-197.

- Tan XH, Zhang KK, Xu JT, Qu D, Chen LJ, Li JH, Wang Q, Wang HJ, Xie XL: Luteolin alleviates methamphetamine-induced neurotoxicity by suppressing PI3K/Akt pathway-modulated apoptosis and autophagy in rats. Food Chem Toxicol 2020, 137:111179.

- Zhang KK, Wang H, Qu D, Chen LJ, Wang LB, Li JH, Liu JL, Xu LL, Yoshida JS, Xu JT, et al: Luteolin Alleviates Methamphetamine-Induced Hepatotoxicity by Suppressing the p53 Pathway-Mediated Apoptosis, Autophagy, and Inflammation in Rats. Front Pharmacol 2021, 12:641917.

- Wang TJ, Hou WC, Hsiao BY, Lo TH, Chen YT, Yang CH, Shih YT, Liu JC: 2-Hydroxyl hispolon reverses high glucose-induced endothelial progenitor cell dysfunction through the PI3K/Akt/eNOS and AMPK/HO-1 pathways. Br J Pharmacol 2025.

- Guo M, Fu W, Zhang X, Li T, Ma W, Wang H, Wang X, Feng S, Sun H, Zhang Z, et al: Total flavonoids extracted from the leaves of Murraya paniculata (L.) Jack prevents acetaminophen-induced liver injury by activating Keap1/Nrf2 and PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling pathway. J Ethnopharmacol 2025, 344:119562. [CrossRef]

- Gupta P, Srivastav S, Saha S, Das PK, Ukil A: Leishmania donovani inhibits macrophage apoptosis and pro-inflammatory response through AKT-mediated regulation of β-catenin and FOXO-1. Cell Death Differ 2016, 23:1815-1826. [CrossRef]

- Zhou J, Li H, Li X, Zhang G, Niu Y, Yuan Z, Herrup K, Zhang YW, Bu G, Xu H, Zhang J: The roles of Cdk5-mediated subcellular localization of FOXO1 in neuronal death. J Neurosci 2015, 35:2624-2635.

- Zhang Y, Wang M, Tang L, Yang W, Zhang J: FoxO1 silencing in Atp7b(-/-) neural stem cells attenuates high copper-induced apoptosis via regulation of autophagy. J Neurochem 2024, 168:2762-2774.

- Li X, Liu B, Huang D, Ma N, Xia J, Zhao X, Duan Y, Li F, Lin S, Tang S, et al: Chidamide triggers pyroptosis in T-cell lymphoblastic lymphoma/leukemia via the FOXO1/GSDME axis. Chin Med J (Engl) 2024.

- Lee IT, Yang CC, Lin YJ, Wu WB, Lin WN, Lee CW, Tseng HC, Tsai FJ, Hsiao LD, Yang CM: Mevastatin-Induced HO-1 Expression in Cardiac Fibroblasts: A Strategy to Combat Cardiovascular Inflammation and Fibrosis. Environ Toxicol 2025, 40:264-280. [CrossRef]

- Ren Q, Ma M, Yang C, Zhang JC, Yao W, Hashimoto K: BDNF-TrkB signaling in the nucleus accumbens shell of mice has key role in methamphetamine withdrawal symptoms. Transl Psychiatry 2015, 5:e666.

- Kou JJ, Shi JZ, He YY, Hao JJ, Zhang HY, Luo DM, Song JK, Yan Y, Xie XM, Du GH, Pang XB: Luteolin alleviates cognitive impairment in Alzheimer’s disease mouse model via inhibiting endoplasmic reticulum stress-dependent neuroinflammation. Acta Pharmacol Sin 2022, 43:840-849. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).