Introduction

Bipolar disorder (BD) and major depressive disorder (MDD) overlap in terms of clinical symptoms and structural brain abnormalities (especially type II bipolar disorder), particularly involving prefrontal cortex and hippocampal regions. Despite the distinction between the two in terms of diagnostic classification, a growing number of clinical studies have found that a proportion of patients initially diagnosed with depression eventually develop bipolar disorder. Studies have shown that 40-60% of patients with bipolar disorder present with depressive symptoms at first onset (Mitchell et al., 2008), whereas manic or hypomanic symptoms may not appear until years later, leading to early misdiagnosis and delays in treatment, and increasing the risk of relapse and worsening of the condition.

It is critical to explore the neural mechanisms behind this shift. The hippocampus, as a glucocorticoid receptor (GR)-rich brain region, is highly sensitive to stress-induced elevation of GC levels, and prolonged exposure to GC triggers dendritic atrophy, down-regulation of synaptic scaffolding proteins (e.g., PSD-95), and disruption of synaptic plasticity. Progressive damage to hippocampal synapses weakens the inhibitory regulation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis (HPA axis), leading to a vicious cycle of neurotoxicity with elevated cortisol, which in turn triggers disruption of glutamatergic homeostasis and over-activation of NMDA receptors, leading to excitotoxicity and microglial activation.

Recent studies suggest that chronic neuroinflammation may disrupt the normal synaptic pruning mechanism, leading to the mislabeling and removal of active synapses, i.e., the phenomenon of “synaptic mislabeling and mispruning”. This abnormal neural circuit remodeling process, especially in the hippocampal-prefrontal pathway, may play a key role in the progression of MDD to BD.

In this paper, we propose an integrated mechanistic model linking GC-mediated synaptic scaffold disruption, glutamate metabolism disruption, microglial overactivation and neural circuit disconnection, which provides a new theoretical perspective on the mechanism of progression of mood disorders, and a basis for future empirical studies.

While previous studies have independently explored the roles of glucocorticoid-induced synaptic alterations, glutamatergic dysregulation, and microglial activation in mood disorders, an integrative model linking these mechanisms to the progression from major depressive disorder to bipolar disorder remains lacking. This study aims to fill this gap by proposing a comprehensive framework that elucidates the interconnected pathways leading to affective

Background and Mechanistic Overview

Structural and Functional Changes in the Hippocampus and Prefrontal Lobes

Both animal and human studies have shown that elevated GC levels under chronic stress result in diminished hippocampal GR-mediated synaptic plasticity, accompanied by a reduction in synaptic scaffolding proteins such as PSD-95, Syn3, and Synpo (McEwen, 2007). The prefrontal lobe, although slightly less GR-dense, still results in abnormal synaptic remodeling and cortical thinning due to chronic high GC exposure (Radley et al., 2004).

Vulnerability of White Matter Connections

Diffusion tensor imaging (DTI) studies have shown that white matter integrity is reduced in patients with MDD versus BD, particularly in the hippocampal-prefrontal pathway (e.g., fornix, anterior cingulate bundle) (Benedetti et al., 2011).GC may weaken the stability of white matter connectivity through glial cell dysfunction and impaired myelin formation.

Prefrontal Compensatory Mechanisms and Compensatory Failure

Damage to the hippocampus impairs inhibitory regulation of the prefrontal lobes and imbalances prefrontal activity, which may initially manifest as compensatory activation (e.g., enhanced working memory), but chronic high load can induce NMDA receptor overactivation, calcium overload, and synaptic damage (Popoli et al., 2012).

[Chronic Stress] → [↑ Glucocorticoids (GC)] → [Hippocampal Synaptic Scaffolding Loss] → [Microglial & Astrocytic Activation] → [Inflammatory Cytokines (IL-18, TNF-α)] → [Glutamate Dysregulation + NMDA Overactivation] → [Prefrontal Cortex Hyperactivation & Compensation] → [Synaptic Pruning Errors + Excitotoxicity] → [Cognitive & Emotional Dysregulation] → [Progression from MDD to BD]

Discussion

Glycocortisol initiates gray matter pathology via hippocampal GR, and reduction of synaptic scaffolding proteins is a key component of gray matter loss.

Reduced gray matter impairs information exchange and decreased white matter integrity exacerbates dysfunction.

Compensatory overload of the prefrontal lobes provides a potential mechanistic explanation for the conversion of MDD to BD.

Current studies have focused on separate alterations in gray or white matter, and systematic exploration of gray-white matter linkage is lacking.

Theoretical Model

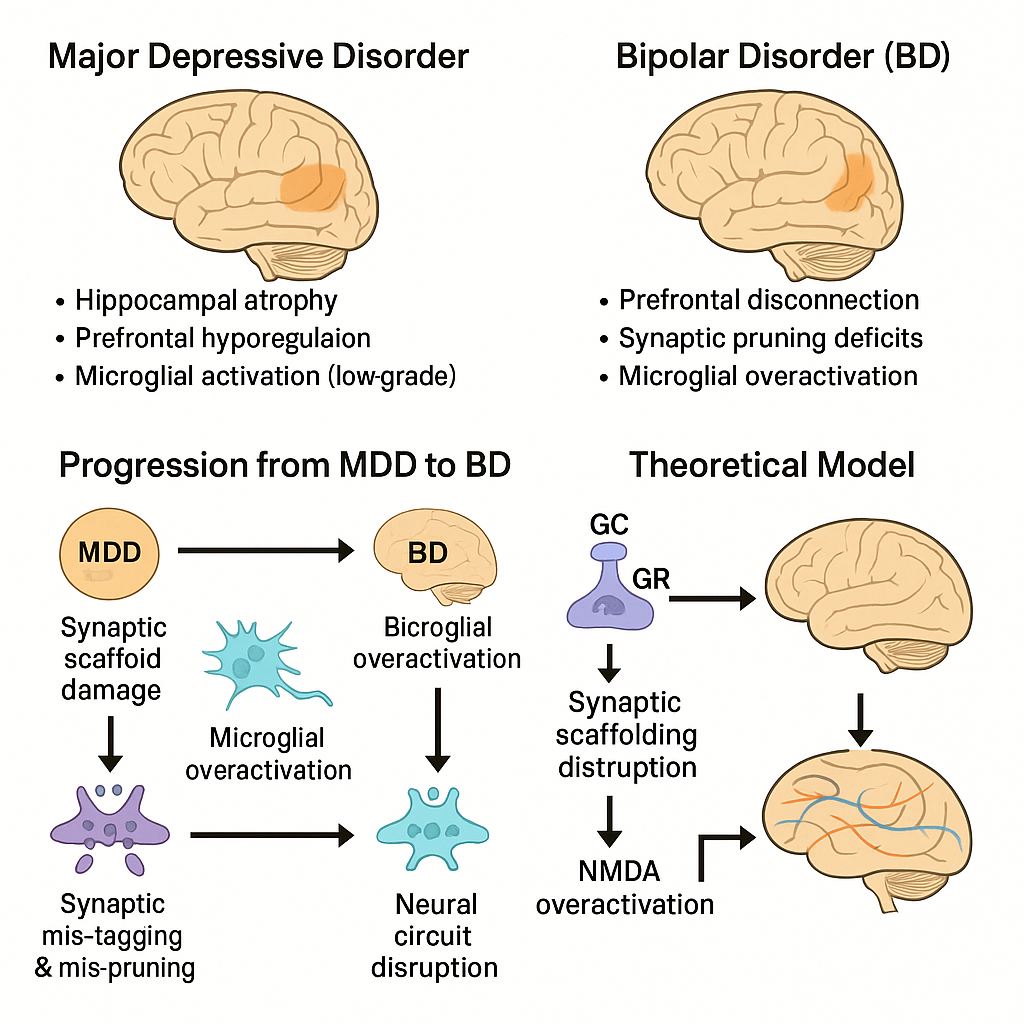

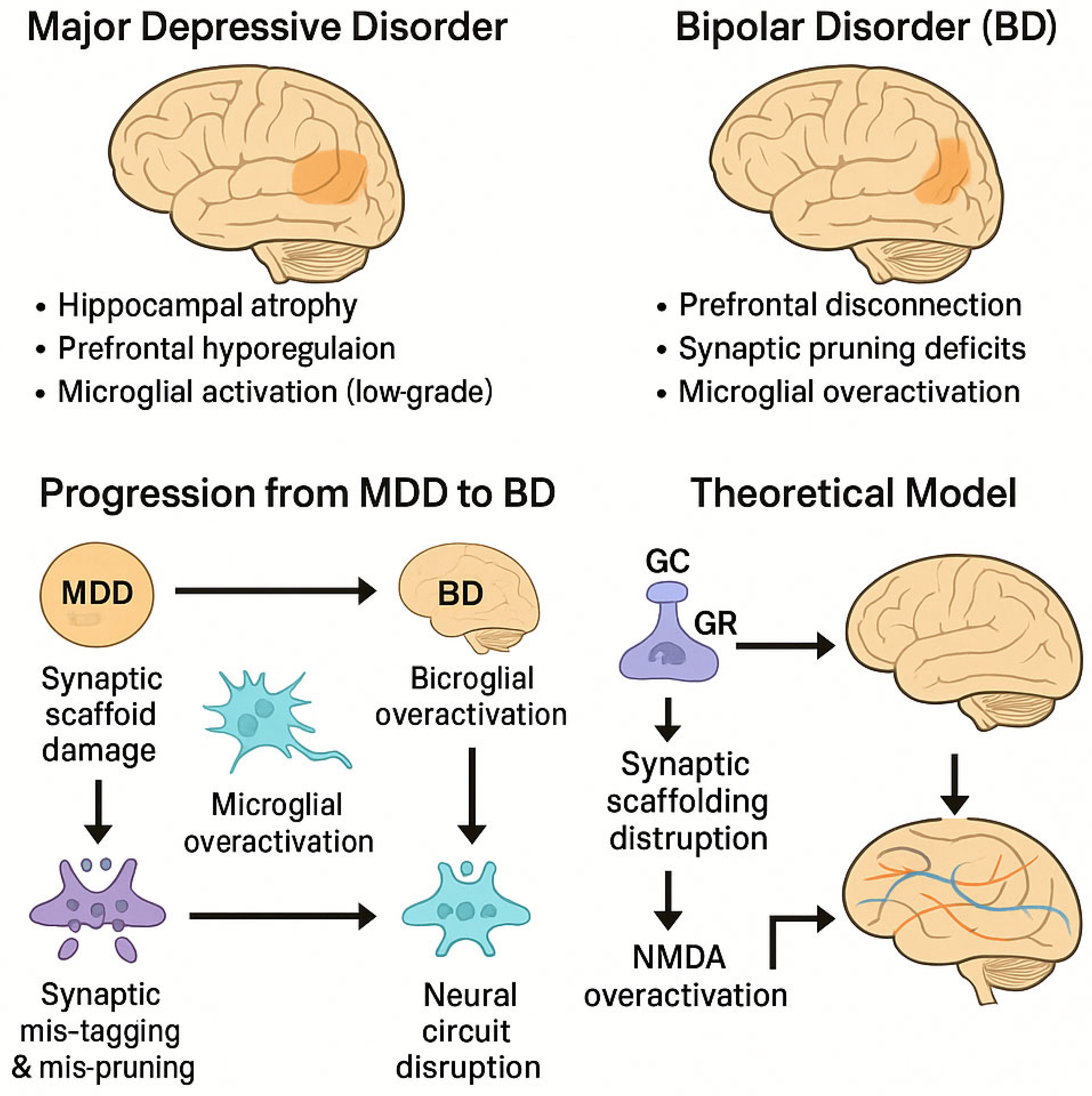

Figure 1.

Mechanistic model linking chronic glucocorticoid exposure and synaptic vulnerability to the progression from major depressive disorder (MDD) to bipolar disorder (BD). Note. GC = glucocorticoid; GR = glucocorticoid receptor; NMDA = N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor; PFC = prefrontal cortex.

Figure 1.

Mechanistic model linking chronic glucocorticoid exposure and synaptic vulnerability to the progression from major depressive disorder (MDD) to bipolar disorder (BD). Note. GC = glucocorticoid; GR = glucocorticoid receptor; NMDA = N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor; PFC = prefrontal cortex.

The proposed model integrates chronic stress-induced neurobiological changes to explain the progression from major depressive disorder (MDD) to bipolar disorder (BD). In this framework, prolonged glucocorticoid (GC) exposure leads to hippocampal synaptic dysfunction through multiple converging mechanisms.

First, elevated GC levels downregulate glucocorticoid receptors (GRs) in the hippocampus, impairing feedback inhibition of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis. This perpetuates further GC release, leading to dendritic atrophy and decreased expression of synaptic scaffolding proteins such as PSD-95. Concurrently, excessive GC exposure destabilizes glutamatergic transmission and enhances NMDA receptor activation, contributing to excitotoxic stress.

Second, microglial activation in response to these synaptic changes initiates maladaptive neuroinflammation, resulting in aberrant synaptic pruning. This mispruning process may mistakenly eliminate functional synapses, particularly within the hippocampal–prefrontal circuitry, and contribute to emotional dysregulation.

Together, these alterations—synaptic scaffold breakdown, glutamate dysregulation, and microglial mispruning—generate a feedback loop that weakens neural circuit integrity. Over time, this may transform the neurofunctional profile of an individual from unipolar depression to bipolar disorder, particularly in genetically or environmentally susceptible individuals.

This model offers a mechanistic basis for understanding why some individuals diagnosed with MDD progress to BD and provides a theoretical target for biomarker identification and early intervention.

Clinical and Research Implications

GC antagonists, GR modulators, and NMDA receptor antagonists (e.g., ketamine) may be used to prevent pathological cascades.

Multimodal imaging combined with animal models is needed to deconstruct the dynamics of synaptic scaffolding-white matter connectivity-network function.

body

1. Hippocampus: stress vulnerability and synaptic scaffold damage

The hippocampus, particularly the CA1 and dentate gyrus regions, is rich in glucocorticoid receptors (GRs) and is highly sensitive to stress-induced elevation of cortisol.Chronic activation of GRs leads to dendritic atrophy, decreased spine synapse density, and ultimately volume loss, as demonstrated in MRI morphologic studies (McEwen, 2007; Sapolsky, 2000). Recent studies have shown that chronic stress disrupts the integrity of synaptic scaffolding proteins (e.g., PSD-95, SYN1) that are critical for maintaining synaptic stability and plasticity (Kallarackal et al., 2013). Progressive impairment of hippocampal synapses weakens their inhibitory regulation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis (HPA axis), leading to persistent elevation of cortisol and a vicious cycle of neurotoxicity.

2. Synaptic scaffolding proteins and network stability

Synaptic scaffolding proteins such as PSD-95 are major markers of postsynaptic density. Synaptic scaffolding proteins act as molecular platforms that anchor neurotransmitter receptors and signaling complexes at postsynaptic density. Chronic stress and glucocorticoid exposure have been found to reduce the expression and aggregation of these scaffolding proteins, disrupting synaptic integrity and plasticity, leading to synaptic instability, loss of spine protrusions, and impaired local communication (Yuen et al., 2011). Disruption of synaptic scaffolds not only weakens local neuronal communication, but also disrupts long-range connectivity by affecting hippocampal output to cortical and subcortical target areas. This scaffold disintegration may be an early event in gray matter reduction and network destabilization

3. White matter destruction and amplification

White matter consists primarily of myelinated axons that facilitate rapid communication between brain regions. Diffusion tensor imaging (DTI) studies have consistently found decreased white matter integrity in patients with major depressive disorder (MDD) and bipolar disorder (BPD) (Versace et al., 2008; Benedetti et al., 2011). As the hippocampus undergoes synaptic and structural degeneration, the associated white matter tracts (e.g., fornix) may also degenerate, further impairing information exchange with the prefrontal lobes. This disconnection exacerbates the failure of regulatory loops between memory and executive centers, potentially pushing the burden of compensation onto prefrontal circuits.

4. Prefrontal Compensation and Collapse

The prefrontal cortex (PFC) plays a central role in emotion regulation, working memory, and executive control. In the early stages of hippocampal dysfunction, the PFC may exhibit compensatory overactivation, as evidenced by increased functional connectivity and heightened metabolic demands (Liston et al., 2006). This hyperactivation may temporarily maintain cognitive stability despite upstream deficits.

However, chronic stress and sustained glucocorticoid exposure also compromise PFC function. Not all “activated synapses” formed under such stress are high-quality or efficient. Many are metabolically burdensome or structurally abnormal, increasing the likelihood of being misidentified as dysfunctional by microglia. This misrecognition leads to erroneous labeling and removal of synapses, even those that are active.

Compensatory activity may thus give rise to inefficient or pathological network configurations within the PFC. These maladaptive circuits, under prolonged stress, become increasingly prone to pruning by overactivated microglia—a phenomenon also observed in models of Alzheimer’s disease (Tremblay et al., 2011; Yirmiya & Goshen, 2011).

Stress-induced inflammation is a critical factor that disrupts the normal “selective protection” of synapses. NMDA receptor overactivation, calcium overload, and mitochondrial dysfunction may compromise synaptic stability, further increasing the risk of erroneous pruning (Arnsten, 2009). Instead of removing only weak synapses, overactivated microglia may mislabel and eliminate even functional synapses.

This progression—from compensatory hyperactivation to synaptic collapse—may explain why patients with depression initially retain cognitive control but gradually develop executive dysfunction and emotional instability, especially after repeated episodes. The extreme anatomical and functional similarity between type II bipolar disorder and major depressive disorder may reflect a pathological transfer from hippocampal to prefrontal circuits, marking the shift in disease phenotype.

Additional Mechanistic Consideration: GABAergic Overactivation

Emerging evidence suggests that excessive activation of GABAergic circuits during adolescence—a sensitive period for synaptic refinement—may independently contribute to prefrontal synaptic degeneration. Optogenetic studies demonstrate that seven days of sustained GABAergic stimulation in adolescent rodents leads to a 28% reduction in dendritic spine density, with corresponding depletion of synaptic vesicle pools and active zone shortening. While some of these changes may exhibit partial reversibility upon stimulus cessation, prolonged inhibitory overload is also linked to persistent epigenetic modifications. For instance, H3K9me3 enrichment at the Grin2a promoter and miR-132 hypermethylation suppress NMDA receptor and BDNF expression, impairing neurogenesis. Additionally, miR-218 has been implicated in stress-induced modulation of GABAergic pruning processes, suggesting a developmental pathway by which environmental stress and pharmacological factors might converge. Of clinical concern, elevated GABAergic tone in adolescent populations—occasionally induced by external agents—raises questions about long-term effects on synaptic architecture and emotional regulation.

Conclusions

We propose that under conditions of chronic stress, damage to hippocampal synapses initiates a cascade of compensatory overactivation in the prefrontal cortex, particularly in regions associated with executive control and affect regulation. While initially adaptive, this sustained activation may foster a localized pro-inflammatory environment, compromising the regulatory role of microglia.

As compensation intensifies, prefrontal synapses formed under stress—often metabolically inefficient—may become targets of aberrant pruning. Microglial overactivation may mistakenly eliminate functional synapses, particularly under stress-induced neuroinflammation. Importantly, glutamate dysregulation, NMDA receptor overactivation, calcium overload, and mitochondrial dysfunction may further destabilize synaptic integrity, promoting erroneous labeling and removal of viable synapses (Arnsten, 2009).

This progression—from compensatory plasticity to synaptic degradation—may help explain why depressed patients initially retain cognitive function but gradually develop executive dysfunction and emotional dysregulation. In some individuals, especially those predisposed genetically or environmentally, this trajectory may culminate in bipolar disorder. The neuroanatomical similarities between type II bipolar disorder and major depression further support this continuum, potentially representing a pathological shift from hippocampal to prefrontal dominance.

This integrative model offers a novel perspective on the neurobiological progression from depression to bipolar disorder, highlighting the interplay between glucocorticoid-mediated synaptic scaffold degradation, glutamate excitotoxicity, and microglial-driven synaptic pruning. Future research should focus on empirical validation of this model through longitudinal studies and exploration of potential therapeutic interventions targeting these interconnected pathways.

Furthermore, this framework may also serve as a theoretical foundation for future investigation into whether anxiety-induced depression—characterized by chronic HPA axis activation and stress-related neuroinflammation—may confer an increased vulnerability to bipolar transition compared to primary depressive syndromes. Clarifying this distinction could help improve early identification and personalized intervention strategies in mood disorders.

Acknowledgments

The author expresses sincere gratitude to Mizuho Mishima for her early guidance and thoughtful feedback during the conceptualization phase of this paper. Although she declined the opportunity to serve as a corresponding author, her mentorship was formative in shaping the author’s research direction. My interest in stress-related psychiatric disorders stems from years of observation and personal experiences in high-pressure educational environments. I also wish to acknowledge the years during which my early scientific curiosity was constrained by a rigid and exam-oriented educational system. This work is, in part, a quiet rebellion and a reaffirmation of my original passion for understanding the brain. The author also wishes to acknowledge the formative experiences that, despite systemic discouragement of independent inquiry during earlier stages of education, laid the groundwork for the questions explored in this paper.These ideas were conceived long before they were allowed to be written. This manuscript also benefited from language and formatting support using AI-based tools, under the full editorial supervision and conceptual direction of the author.

References

- Arnsten, A. F. T. (2009). Stress signaling pathways that impair prefrontal cortex structure and function. *Nature Reviews Neuroscience*, 10(6), 410–422. [CrossRef]

- Chen, J., et al. (2011). Benzodiazepine-induced synaptic remodeling in the prefrontal cortex. *Nature Neuroscience*. [CrossRef]

- Feng, C., et al. (2022). fNIRS study of prefrontal cortical activation in BD patients. *Frontiers in Neuroscience*, 16, 946543. [CrossRef]

- Ghosal, S., et al. (2021). Chronic stress-induced alterations in the prefrontal cortex and their relevance to depression. *Nature Communications*, 12, 24967. [CrossRef]

- Joëls, M., & Baram, T. Z. (2009). The neuro-symphony of stress. *Nature Reviews Neuroscience*, 10(6), 459–466. [CrossRef]

- Khundakar, A. A., et al. (2023). Chronic stress and neuroinflammation: Cross-talk between glial activation and synaptic pathology. *Neuroscience and Behavioral Physiology*, 53(5), 501–510. [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y. K., et al. (2018). Glutamatergic system alterations in BD and schizophrenia: An MRS study. *BioMed Research International*, 2018, 3654894. [CrossRef]

- Maes, M., et al. (2011). Inflammatory and oxidative stress pathways underpinning depression. *Stress*, 14(5), 498–511. [CrossRef]

- McEwen, B. S. (2006). Protective and damaging effects of stress mediators: Central role of the brain. *Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience*, 8(4), 367–381. https://psycnet.apa.org/record/2006-21350-004.

- Popoli, M., et al. (2012). The stressed synapse: The impact of stress and glucocorticoids on glutamate transmission. *Nature Reviews Neuroscience*, 13(1), 22–37. [CrossRef]

- Scangos, K. W., et al. (2023). Structural brain changes in bipolar disorder: Effects of manic episodes. *Molecular Psychiatry*, 28, 720–734. [CrossRef]

- Yuen, E. Y., et al. (2011). Mechanisms for acute stress-induced dendritic remodeling in the prefrontal cortex. *Journal of Neuroscience*, 31(50), 18036–18045.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).