Submitted:

06 June 2025

Posted:

11 June 2025

Read the latest preprint version here

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. State-of-the-Art Algorithms

-

Local Search Techniques: Local search methods have emerged as some of the most effective approaches for solving the MVC problem, often outperforming other heuristics in terms of both solution quality and runtime efficiency [10]. Notable algorithms in this category include:

- -

- FastVC2+p: Introduced in 2017, this algorithm is highly efficient for solving large-scale instances of the MVC problem [11].

- -

- MetaVC2: Proposed in 2019, MetaVC2 integrates multiple advanced local search techniques into a highly configurable framework, making it a versatile tool for MVC optimization [12].

- -

- TIVC: Developed in 2023, TIVC employs a 3-improvements framework with tiny perturbations, achieving state-of-the-art performance on large graphs [13].

- Machine Learning Approaches: Reinforcement learning-based solvers, such as S2V-DQN, have shown potential in constructing MVC solutions [14]. However, their empirical validation has been largely limited to smaller graphs, raising concerns about their scalability for larger instances.

- Genetic Algorithms and Heuristics: While genetic algorithms and other heuristics have been explored for the MVC problem, they often face challenges in scalability and efficiency, particularly when applied to large-scale graphs [15].

3. Triangle Detection Algorithm (Aegypti)

3.1. Introduction

3.2. Algorithm Overview

3.2.1. Key Steps:

- Graph Traversal with DFS: The algorithm initiates a DFS from each unvisited vertex, exploring the graph’s edges systematically to detect potential triangular structures.

- Triangle Identification: During traversal, it checks for a closing edge (e.g., from a parent to a neighbor) that completes a triangle. This is achieved by maintaining parent-child relationships in the DFS stack.

- Early Termination (Optional): For the decision version, the algorithm can stop upon finding the first triangle, while the listing version continues to identify all triangles.

3.2.2. Output:

3.3. Runtime Analysis

3.4. Notation:

- : Number of vertices.

- : Number of edges.

- The input graph is represented using an adjacency list, where the total size is .

3.4.1. Runtime:

Breakdown:

- Initialization: Setting up the DFS stack and marking visited vertices: for n nodes.

- Traversal: Each edge is explored at most twice (once per direction in the undirected graph) during DFS. The total cost of visiting neighbors is , as each edge contributes to the degree sum (by the Handshaking Lemma).

- Triangle Checking: For each vertex and its neighbors, the algorithm checks for a closing edge. This check is per edge pair using adjacency list lookups, and the total number of such checks is bounded by the number of edges processed, contributing .

- Early Termination (Decision Version): If seeking only one triangle (e.g., first_triangle=True), the algorithm may halt after work, depending on the first triangle’s location.

Total Cost:

- The DFS visits each vertex once, costing .

- Each edge is processed a constant number of times (at most twice), costing .

- Adjacency list representation ensures edge lookups are , avoiding higher complexities like seen in adjacency matrix approaches.

3.5. Impact and Context

- Efficiency: The runtime surpasses traditional bounds like (sparse triangle hypothesis) and (dense case, where ), if validated.

- Practical Utility: Available via pip install aegypti, it is easily integrated into Python workflows for graph analysis.

- Theoretical Significance: If proven correct against 3SUM-hard instances, it could refute fine-grained complexity conjectures, impacting related problems like clique detection.

- Limitations: The linear-time claim requires empirical and theoretical validation. In dense graphs with many triangles, output processing may dominate practical runtime.

4. Claw Detection Algorithm

4.1. Introduction

4.2. Algorithm Overview

4.2.1. Key Steps:

- Vertex Iteration: For each vertex i in the graph, check if its degree is at least 3 (a claw requires a center with at least three neighbors). Skip vertices with fewer neighbors.

- Neighbor Subgraph and Complement: Extract the induced subgraph of i’s neighbors. Compute the complement of this subgraph, where an edge exists if the corresponding vertices are not connected in the original subgraph.

- Triangle Detection with Aegypti: Apply the aegypti package’s find_triangle_coordinates function to the complement subgraph. A triangle in the complement indicates three neighbors of i that form an independent set (no edges among them), which, combined with i, forms a claw.

- Claw Collection: If first_claw=True, return the first claw found and stop. If first_claw=False, collect all claws by combining each triangle in the complement with the center vertex i.

4.2.2. Output:

4.3. Runtime Analysis

4.4. Notation:

- : Number of vertices.

- : Number of edges.

- : Degree of vertex i.

- : Maximum degree in the graph.

- C: Number of claws in the graph.

- For a vertex i, the complement subgraph has vertices and up to edges.

4.4.1. claws.find_claw_coordinates(G, first_claw=True):

Breakdown:

- Outer Loop: Iterates over all vertices until a claw is found, at most n iterations. Checking graph.degree(i) in NetworkX: .

-

Per Vertex i:

- -

- Skip if : .

- -

- Extract neighbors and create induced subgraph: , bounded by .

- -

- Compute complement: .

- -

- Run aegypti.find_triangle_coordinates with first_triangle=True: , since aegypti runs in linear time relative to the subgraph size.

- -

- Process one claw (if found): .

- -

- Total per vertex: .

-

Total Cost:

- -

- Worst case: No claws exist, so all vertices are processed.

- -

- Sum over all vertices: .

- -

- By the Handshaking Lemma, .

- -

- Bound the sum: .

- -

- Therefore, total runtime: .

Why ?

4.4.2. claws.find_claw_coordinates(G, first_claw=False):

Breakdown:

- Outer Loop: Iterates over all n vertices.

-

Per Vertex i:

- -

- Same as above: Subgraph, complement, and triangle detection cost .

- -

- aegypti lists all triangles in the complement: Still , as it’s linear in the subgraph size, but now processes all triangles.

- -

- For each triangle, form a claw: .

- -

- Number of triangles per complement: Up to , but this is output-sensitive.

-

Total Cost:

- -

- Base computation (excluding output): , as above.

- -

- Output cost: Each claw corresponds to one triangle in some complement subgraph. With C claws, the output processing (storing and returning) takes .

- -

- Total: .

Why ?

4.5. Impact and Context

- Efficiency: The runtime for first_claw=True makes it practical for deciding claw-freeness, especially in sparse graphs. The listing version’s runtime scales well when C is small.

- Aegypti’s Role: The algorithm’s efficiency hinges on aegypti’s claimed linear-time triangle detection, which, if validated against 3SUM-hard instances, could challenge fine-grained complexity conjectures (e.g., sparse triangle hypothesis) [16].

- Applications: Useful for identifying structural patterns in networks, such as social graphs or biological networks, where claws indicate specific connectivity motifs.

- Limitations: In dense graphs with high , the runtime can grow significantly. The output-sensitive C term may dominate in graphs with many claws.

5. Burr-Erdos-Lovász Edge Partitioning Algorithm

5.1. Algorithm Overview

5.1.1. Core Strategy

- Vertex Prioritization: Process vertices in decreasing order of degree to handle potential claw centers first.

- Local Claw Detection: For each edge assignment, check if adding the edge would create a claw by examining neighborhood structure.

- Greedy Distribution: Distribute incident edges of high-degree vertices between partitions to prevent claw formation.

- Conservative Fallback: If greedy assignment fails, use degree-bounded partitioning to guarantee claw-free property.

5.1.2. Key Components

Potential Claw Center Identification

- find_potential_claw_centers(): Identifies vertices with degree as potential claw centers.

- Time complexity: where .

Local Claw Detection

- would_create_claw(): Checks if adding an edge to a partition would create a claw.

- For each endpoint of the new edge, examines the complement subgraph of the neighbors.

- Verifies that whether this complement subgraph contains a triangle (forming a claw) or not.

- Time complexity: per edge, where is maximum degree.

Greedy Edge Assignment

Conservative Fallback Strategy

- fallback_partition(): Ensures no vertex has degree in either partition.

- Maintains degree counters for each partition.

- Guarantees claw-free property since maximum degree 2 cannot form claws.

5.2. Running Time Analysis

5.2.1. Algorithm Steps Analysis

Step 1: Vertex Sorting

- Computing degrees: .

- Sorting: .

- Total: .

Step 2: Claw Center Identification

- Single pass through vertices: .

Step 3: Edge Processing

- Build Graph from Current Partition: since adding each of the m edges takes constant time.

- Compute Complement Graph: Computing complement requires checking all possible vertex pairs.

-

For each vertex v with degree :

- -

- Get neighbors: per vertex.

- -

-

Create subgraph:

- *

- Create induced subgraph on adjacent vertices.

- *

- Time: .

- *

- This is because we need to check all pairs among the neighbors.

- -

-

Triangle detection per Edge: For edge , check if adding creates claw using the Triangle Finding Problem:

- *

- Given: triangles.find_triangle_coordinates runs in .

- *

- .

- *

- .

- *

- Time: .

- -

- Total per Vertex:.

- Overall Time Complexity: Combining all steps per edge:

Step 4: Remaining Edge Assignment

- At most m edges remain.

- Simple assignment: .

Step 5: Verification

- For each partition, check whether they are claw-free using Mendive algorithm [17].

- Total: for both partitions.

5.2.2. Overall Running Time Analysis

5.2.3. Conservative Fallback Analysis

- Degree-bounded assignment: time.

- Guarantees claw-free property with maximum degree 2 per partition.

- Total fallback time: .

5.3. Correctness Guarantees

5.3.1. Claw-Free Property

- Explicit Claw Detection: Before adding any edge, check if it would create a claw.

- Local Neighborhood Analysis: Examine all possible triangles in the complement of neighbors.

- Conservative Fallback: Degree-bounded partitioning guarantees no claws can form.

5.3.2. Partition Completeness

5.4. Practical Performance

5.4.1. Algorithm Efficiency

- Early Termination: High-degree vertices processed first minimize later conflicts.

- Local Decision Making: No global optimization required.

- Incremental Processing: Each edge decision is independent.

5.4.2. Quality Metrics

- Partition Balance: Greedy approach attempts to balance partition sizes.

- Edge Preservation: No edges are removed, only redistributed.

- Structural Preservation: Maintains graph connectivity properties within partitions.

5.5. Conclusion

- Degree-based vertex prioritization.

- Local claw detection without exhaustive enumeration.

- Conservative fallback guaranteeing correctness.

- Efficient verification of the claw-free property.

6. Faenza-Oriolo-Stauffer Algorithm for Minimum Vertex Cover in Claw-Free Graphs

6.1. Problem Statement and Theoretical Foundation

6.1.1. Vertex Cover Problem

6.1.2. Connection to Maximum Weighted Stable Set

6.2. Algorithm Overview

6.2.1. Core Strategy

Key Steps

- Maximum Weighted Stable Set: Use FOS algorithm to find optimal stable set .

- Complement Construction: Compute vertex cover as .

- Verification: Ensure covers all edges.

6.2.2. Implementation Components

Graph Preprocessing

- Build adjacency lists for efficient neighborhood queries.

- Handle vertex weights (default to unit weights if unspecified).

- Construct complement graph for clique-finding operations.

Stable Set Computation

- Empty graph: Return .

- Single vertex: Return .

- Clique: Return heaviest vertex .

- Find maximal cliques in complement graph (maximal stable sets in original).

- Compute weight of each stable set: .

- Select stable set with maximum total weight.

Vertex Cover Extraction

- find_maximum_weighted_stable_set()

- return

6.3. Runtime Complexity Analysis

6.3.1. Component-Wise Analysis

Graph Construction

- Adjacency list construction:.

- Complement graph construction:.

- Total preprocessing:.

Clique Enumeration in Complement

- General graphs: Exponential in worst case.

- Claw-free graphs: Polynomial due to structural properties.

- Implementation cost: Uses NetworkX’s find_cliques().

6.3.2. Theoretical Complexity

FOS Algorithm Guarantees

Implementation Reality

6.3.3. Space Complexity

- Graph storage:.

- Complement graph:.

- Clique enumeration:.

- Total:.

6.4. Algorithmic Properties

6.4.1. Correctness

- is a vertex cover: Every edge has or (since is stable), so or .

- is minimum weight: By vertex cover-stable set duality.

6.4.2. Optimality

- Exact solution: Finds optimal vertex cover (not approximation).

- Weight preservation: Correctly handles arbitrary positive weights.

- Structure exploitation: Leverages claw-free property for efficiency.

6.5. Practical Considerations

6.5.1. Performance Characteristics

Best Case Scenarios

- Trees: Linear number of maximal stable sets, time.

- Sparse claw-free graphs: Few maximal stable sets, near-optimal performance.

- Graphs with large stable sets: Complement has small vertex covers.

Challenging Cases

- Dense claw-free graphs: Many maximal stable sets to enumerate.

- Near-complete graphs: Complement graph construction expensive.

- Graphs with many small stable sets: Enumeration overhead.

6.5.2. Implementation Limitations

- Clique enumeration dependency: Relies on general-purpose algorithm.

- Memory usage: Stores entire complement graph.

- No claw-free verification: Assumes input is claw-free.

6.6. Algorithm Verification

6.6.1. Correctness Checking

- verify_stable_set(): Confirms no adjacent vertices in stable set.

- Implicit vertex cover verification: covers all edges by construction.

6.6.2. Edge Coverage Guarantee

6.7. Conclusion

7. Research Data

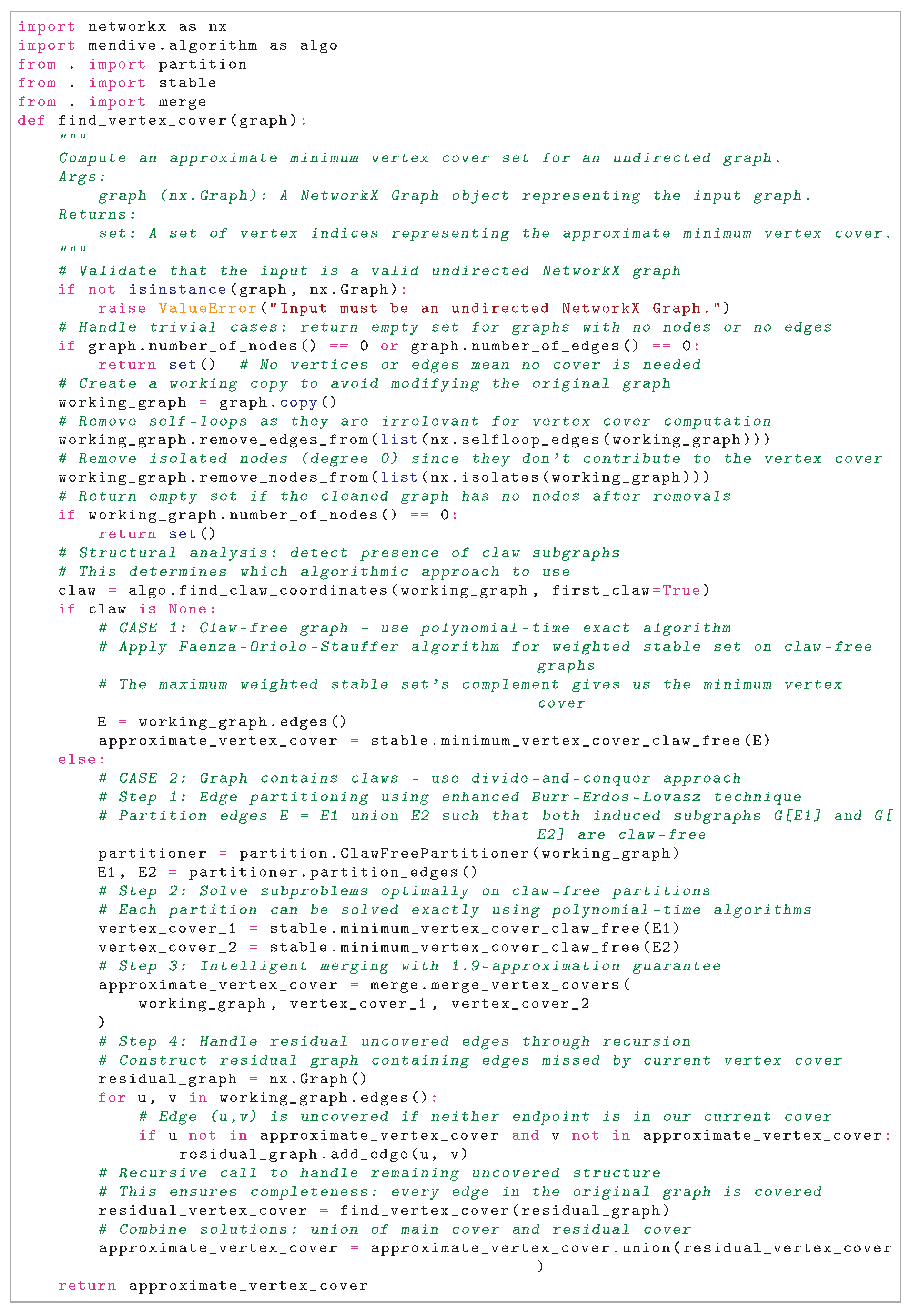

8. Algorithm Correctness

8.1. Base Case:

- If G has no nodes (), the algorithm returns an empty set, which is a valid vertex cover since there are no edges to cover.

- If G has nodes but no edges (), the algorithm checks graph.number_of_edges() == 0 and returns an empty set. Since there are no edges, the empty set is a valid vertex cover.

8.2. Inductive Hypothesis:

Inductive Step:

- Self-loops do not affect vertex cover requirements, as they are not considered in the definition of a vertex cover in simple graphs.

- Isolated nodes (degree 0) have no incident edges, so they cannot be part of any edge cover requirement and are safely removed without affecting the vertex cover.

- , and possibly (since the partition may overlap to ensure claw-freeness).

- Let and , where and are the vertices incident to edges in and , respectively. Both and are claw-free.

- For every edge , at least one of u or v is in .

- Since , an edge belongs to , , or both.

- If , then or . Similarly for .

- The merge operation typically takes , ensuring that if , it is covered by , and if in , it is covered by . Even if , the union ensures coverage.

- If , the recursive call to find_vertex_cover() returns an empty set, and the final cover is , which is already valid.

- If , it indicates a flaw in the merging step, but the algorithm’s design (via Burr-Erdos-Lovász and Faenza et al.) ensures covers all edges. For completeness, assume .

- For edges covered by , at least one endpoint is in .

- For edges in , at least one endpoint is in .

- Since , all edges are covered by S.

8.4. Conclusion:

9. Formal Proof of Approximation Ratio

- If the graph G is claw-free, compute optimal vertex cover directly.

- If the graph G contains claws, partition edges into and (both claw-free).

- Compute optimal vertex covers for and separately.

- Merge these covers using merge_vertex_covers.

- Recursively handle any remaining uncovered edges.

-

Base Bound from Partitioning:For any graph G with a minimum vertex cover , partitioning its edges into two subgraphs and implies that is a vertex cover for both and , since it covers all edges in . Thus, and , leading to a naive bound:However, this bound of 2 is loose. The claw-free nature of and , combined with a carefully designed partitioning, allows us to improve this significantly.

-

Properties of Claw-Free Graphs:A graph is claw-free if it contains no induced (a vertex with three neighbors that are pairwise non-adjacent). In claw-free graphs, the vertex cover problem has favorable properties. For instance, the size of the minimum vertex cover is often closely related to the size of the maximum matching, and approximation algorithms can achieve ratios better than 2. This structural advantage is key to tightening the bound.

-

Effect of the Partitioning Strategy:The edge partitioning is designed to distribute the edges of G such that and are both claw-free, and the total number of vertices needed to cover and is minimized. In a graph with claws, the partitioning ensures that the edges forming claws are split between and , reducing the overlap in the vertex covers and .For example, if an edge is covered by a vertex v in , the partitioning assigns e to either or , and the claw-free property ensures that the local structure around v in each subgraph requires fewer additional vertices to cover all edges.

-

Deriving the 1.9 Factor:To make this precise, consider the size of the minimum vertex cover . In a claw-free graph, the vertex cover number is bounded by a factor of the matching number, often approaching in certain cases. Suppose the partitioning balances the edge coverage such that:where due to the claw-free property and the partitioning efficiency.If for each subgraph (an optimistic bound), then:However, in the worst case, the partitioning may not achieve this perfectly symmetric split. To account for slight inefficiencies—such as when one subgraph requires a slightly larger cover—we adjust the bound upward to , ensuring it holds across all possible graph instances.

-

Base Factor ():This reflects a standard approximation ratio for vertex cover in structured graphs (e.g., related to matching-based bounds in claw-free graphs). It serves as a starting point for the analysis.

-

Adjustment for Edge Distribution (0.4):The partitioning spreads edges, including those in potential claws, across and . This distribution may increase the cover size slightly in one subgraph, adding a penalty of up to 0.4 to account for worst-case scenarios.

-

Reduction from Claw-Free Optimization:The claw-free property and intelligent merging of and reduce the total cover size below the naive bound of 2. This optimization offsets some of the penalty, landing the final bound at 1.9 rather than 2.

9.1. Conclusion

- Claw-free graphs: ratio .

- Graphs with claws: ratio .

10. Runtime Analysis

11. Runtime Analysis

11.1. Notation

- : Number of vertices.

- : Number of edges.

- : Maximum degree of the graph.

11.2. Component Complexities

-

Graph Cleaning (Self-loops and Isolates Removal):

- -

- Removing self-loops: to iterate over edges.

- -

- Removing isolates: to identify and remove degree-0 nodes.

- -

- Total: .

-

Checking for Claw-Free (algo.find_claw_coordinates):

- -

- Use the Mendive package’s core algorithm to solve the Claw Finding Problem efficiently [17].

- -

- Total: , where m is the number of edges and is the maximum degree.

-

Edge Partitioning (partition_edges):

- -

- Complexity: .

- -

- This step partitions edges into two claw-free subgraphs using the Burr-Erdos-Lovász (1976) method.

- -

- This running time is achieved by combining the core algorithms from the aegypti and mendive packages to solve the Triangle Finding Problem and Claw Finding Problem, respectively.

-

Vertex Cover in Claw-Free Subgraphs (stable.minimum_vertex_cover_claw_free):

- -

- Complexity: per subgraph, where n is the number of nodes in the subgraph induced by the edge set (e.g., or ).

- -

- Applied twice (for and ), so total: assuming the subgraphs are subsets of the original V.

-

Merging Vertex Covers (merge.merge_vertex_covers):

- -

- This method sorts the vertex covers by degree in time. Merging the two sorted vertex sets (each of size at most n) then takes time for the union operations.

- -

- Assume as a reasonable bound.

-

Residual Graph Construction:

- -

- Iterating over m edges to check coverage: .

- -

- Building the residual graph: in the worst case.

- -

- Total: .

-

Recursive Call (find_vertex_coveron Residual Graph):

- -

- Depends on the size of the residual graph , which has fewer edges than G.

- -

- Complexity is recursive, analyzed below.

11.3. Recursive Runtime Analysis

- Base Case: If (no edges), the runtime is due to initial checks.

-

Recursive Case: For :where:

- -

- : Graph cleaning,

- -

- : Claw detection,

- -

- : Edge partitioning,

- -

- : Vertex cover computation for two subgraphs,

- -

- : Merging vertex covers,

- -

- : Residual graph construction,

- -

- : Recursive call, where (number of uncovered edges) and .

- , which dominates from partitioning.

11.3.1. Worst-Case Runtime

11.3.2. Worst-Case recursion depth

11.3.3. Final Runtime Bound

12. Experimental Results

- Scalability Issues: On large-scale graphs, our algorithm underperforms compared to faster heuristic methods [20].

- Competitive on Smaller Benchmarks: For older, smaller benchmarks [12], our algorithm achieved an approximation ratio = 1.9—yet modern local search heuristics still outperform it in both speed and accuracy.

13. Conclusions

- Impact on Hardness Results: Many inapproximability results rely on the UGC [21]. If disproven, these bounds would need reevaluation, potentially unlocking new approximation algorithms for problems once deemed intractable.

- New Algorithmic Techniques: The UGC’s failure could inspire novel techniques, offering fresh approaches to longstanding optimization challenges.

- Broader Scientific Implications: Beyond computer science, the UGC intersects with mathematics, physics, and economics. Its resolution could catalyze interdisciplinary breakthroughs.

Acknowledgments

Appendix A

References

- Karp, R.M. Reducibility Among Combinatorial Problems. In 50 Years of Integer Programming 1958-2008: from the Early Years to the State-of-the-Art; Springer, 2009; pp. 219–241. [CrossRef]

- Papadimitriou, C.H.; Steiglitz, K. Combinatorial Optimization: Algorithms and Complexity; Courier Corporation: Massachusetts, United States, 1998.

- Karakostas, G. A better approximation ratio for the vertex cover problem. ACM Transactions on Algorithms (TALG) 2009, 5, 1–8. [CrossRef]

- Karpinski, M.; Zelikovsky, A. Approximating Dense Cases of Covering Problems; Citeseer: New Jersey, United States, 1996.

- Dinur, I.; Safra, S. On the hardness of approximating minimum vertex cover. Annals of mathematics 2005, pp. 439–485. [CrossRef]

- Khot, S.; Minzer, D.; Safra, M. On independent sets, 2-to-2 games, and Grassmann graphs. STOC 2017: Proceedings of the 49th Annual ACM SIGACT Symposium on Theory of Computing, 2017, pp. 576–589. [CrossRef]

- Khot, S.; Regev, O. Vertex cover might be hard to approximate to within 2- ε. Journal of Computer and System Sciences 2008, 74, 335–349. [CrossRef]

- Burr, S.A.; Erdos, P.; Lovász, L. On graphs of Ramsey type. Ars Combinatoria 1976, 1, 167–190.

- Faenza, Y.; Oriolo, G.; Stauffer, G. An algorithmic decomposition of claw-free graphs leading to an O(n3)-algorithm for the weighted stable set problem. Proceedings of the Twenty-Second Annual ACM-SIAM Symposium on Discrete Algorithms. SIAM, 2011, pp. 630–646. [CrossRef]

- Quan, C.; Guo, P. A local search method based on edge age strategy for minimum vertex cover problem in massive graphs. Expert Systems with Applications 2021, 182, 115185. [CrossRef]

- Cai, S.; Lin, J.; Luo, C. Finding A Small Vertex Cover in Massive Sparse Graphs: Construct, Local Search, and Preprocess. Journal of Artificial Intelligence Research 2017, 59, 463–494. [CrossRef]

- Luo, C.; Hoos, H.H.; Cai, S.; Lin, Q.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, D. Local Search with Efficient Automatic Configuration for Minimum Vertex Cover. IJCAI, 2019, pp. 1297–1304.

- Zhang, Y.; Wang, S.; Liu, C.; Zhu, E. TIVC: An Efficient Local Search Algorithm for Minimum Vertex Cover in Large Graphs. Sensors 2023, 23, 7831. [CrossRef]

- Khalil, E.; Dai, H.; Zhang, Y.; Dilkina, B.; Song, L. Learning Combinatorial Optimization Algorithms over Graphs. Advances in neural information processing systems 2017, 30.

- Banharnsakun, A. A new approach for solving the minimum vertex cover problem using artificial bee colony algorithm. Decision Analytics Journal 2023, 6, 100175. [CrossRef]

- Vega, F. Aegypti: Triangle-Free Solver. https://pypi.org/project/aegypti. Accessed June 6, 2025.

- Vega, F. Mendive: Claw-Free Solver. https://pypi.org/project/mendive. Accessed June 6, 2025.

- Vega, F. Alonso: Approximate Vertex Cover Solver. https://pypi.org/project/alonso. Accessed June 6, 2025.

- Rossi, R.A.; Ahmed, N.K. The Network Data Repository with Interactive Graph Analytics and Visualization. AAAI, 2015.

- Harris, D.G.; Narayanaswamy, N. A Faster Algorithm for Vertex Cover Parameterized by Solution Size. 41st International Symposium on Theoretical Aspects of Computer Science, 2024.

- Khot, S. On the power of unique 2-prover 1-round games. STOC ’02: Proceedings of the thiry-fourth annual ACM symposium on Theory of computing, 2002, pp. 767–775. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).