Introduction

Fragrances have long served as a cultural and emotional touchstone, intertwining sensory allure with personal identity, from the myrrh of ancient Egypt to the synthetic musks of modern perfumery [

1]. The global fragrance market, valued at over

$50 billion, thrives on evoking emotion and individuality [

2]. However, a persistent challenge undermines this appeal: the same fragrance performs differently across individuals, varying in longevity, projection, and olfactory character [

3]. This variability frustrates consumers, who often over-apply, switch brands, or discard products, amplifying health risks from chemical exposure and contributing to environmental waste [

3]. Social media, driving nearly 30% of fragrance purchases through influencers, perpetuates this cycle by encouraging trial-and-error buying [

2].

Historically, perfumers attributed fragrance variability to skin chemistry, encompassing pH, sebum, and temperature [

4]. Advances in microbiology highlight the skin microbiome—bacteria such as Staphylococcus epidermidis and Corynebacterium, fungi such as Malassezia, and viruses—as a key modulator of skin physiology [

5]. Research reported that molecules on the skin surface are primarily products of microbial metabolism, including organic compounds processed by enzymes like lipases and esterases [

6]. The skin microbiome produces volatile compounds contributing to body odour [

7]. These enzymes may transform fragrance volatile organic compounds, such as esters and terpenes, potentially altering their scent profiles.

While microbiome science has revolutionized dermatology and nutrition, its application to fragrance personalization remains underexplored [

7,

19]. Consumer demand for biologically tailored beauty is surging, with strong interest in personalized solutions [

9].

This review proposes a framework for fragrance personalization, integrating microbial ecology, fragrance chemistry, and consumer trends. It explores biological drivers of scent variability, microbial VOC modulation, health and environmental implications, and practical personalization strategies, with or without metagenomic testing. Individual physiological differences necessitate personalizing fragrances to optimize their sensory impact [

10]. By aligning fragrances with individual biology and microbiome, this approach may enhance scent performance, reduce health risks, and promote sustainability, redefining fragrances as personalized wellness.

The Skin Microbiome and Fragrance VOC Modulation

The human skin microbiome contributes directly to the production and transformation of volatile organic compounds (VOCs), significantly influencing fragrance performance [

7]. Microbial diversity varies by body site, driven by differences in moisture, sebum, and local skin chemistry [

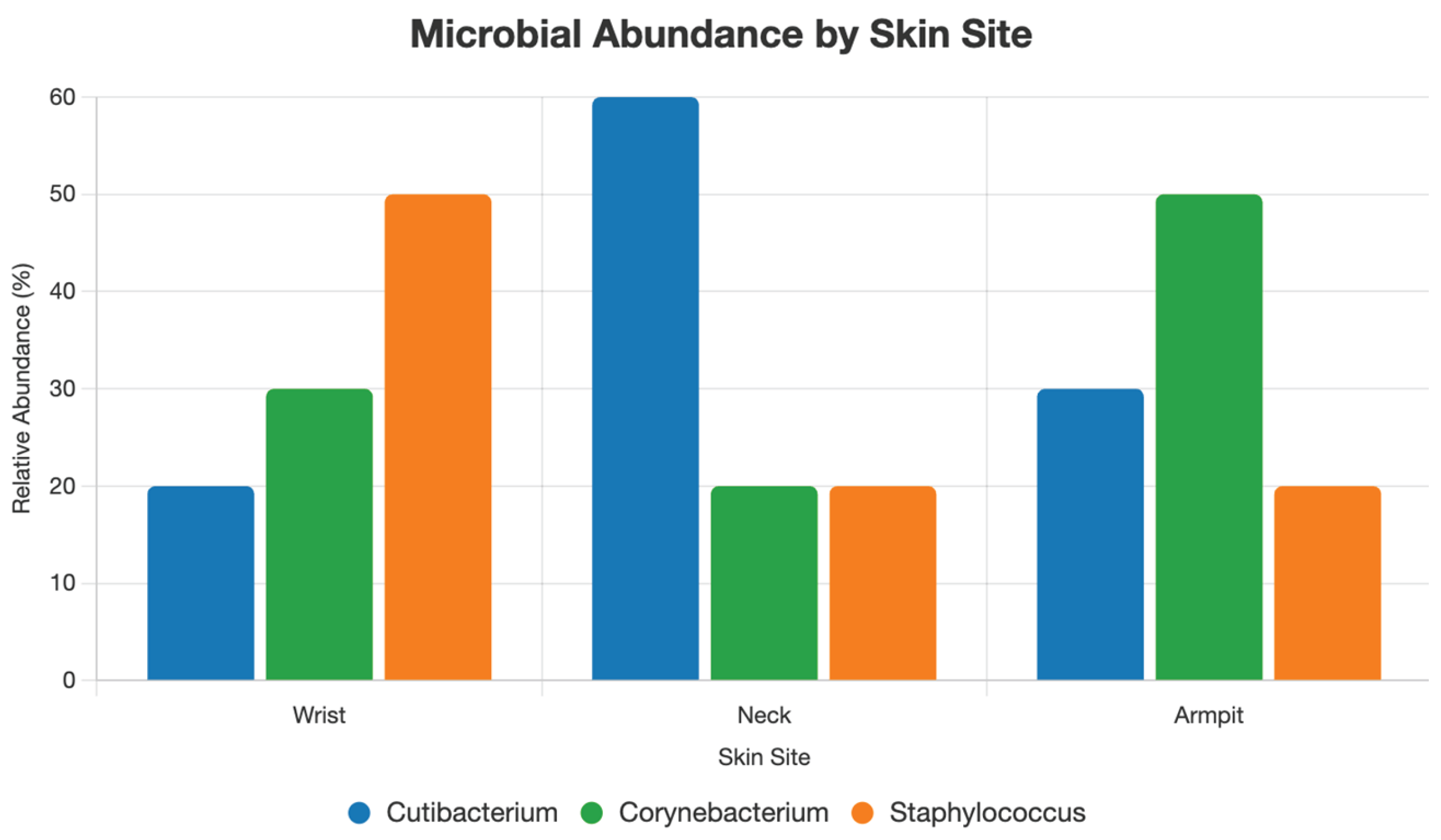

6]. Bacteria such as Cutibacterium acnes produce lipases that metabolize skin lipids, modifying the biochemical environment and indirectly altering fragrance interactions [

5]. Microbial density, particularly of Cutibacterium, varies across skin sites, contributing to odour formation [

23] [

Figure 1].

In the axillary region, Corynebacterium species utilize dehydrogenases to generate sulfur-containing volatiles, a hallmark of body odour [

24,

25,

28]. Other bacteria, like Staphylococcus epidermidis, possess weak esterase activity, resulting in minimal transformation of esters and low odour output [

26]. In contrast, Staphylococcus hominis produces thioalcohols and other volatiles that affect odour intensity and perception [

29]. Collectively, these bacteria metabolize sweat compounds and sebum, contributing to the VOC profile on the skin [

20]. [

Table 1]

Skin pH, which is influenced by microbial metabolic activity, further modulates the reactivity and perception of perfume molecules [

31]. External factors such as hormonal changes also play a role by altering microbial populations and skin secretions, thereby affecting compound transformation [

32]. Studies also confirm that fragrance molecules, including those in iconic formulations like Chanel No. 5, interact with skin substrates and are susceptible to alteration post-application [

10,

27,

30].

The available data strongly support the following extrapolations. Corynebacterium-derived sulfur compounds can degrade aldehydic top notes, shortening their longevity. Staphylococcus hominis volatiles may disrupt floral accord projection. Cutibacterium acnes, through its lipid metabolism, could diminish aldehyde stability in sebaceous regions. Meanwhile, Staphylococcus epidermidis may exert negligible interference with stable compounds like geranyl acetate. Hormonal shifts might enhance microbial enzyme activity, modulating woody note persistence. Collectively, these microbial activities support the concept that skin flora directly impacts perfume outcome and justifies microbiome-based fragrance personalization.

Health Risks of Fragrance Components

Fragrances, when applied excessively or formulated without consideration for an individual’s unique skin biology, present a range of significant health risks that necessitate careful attention to ensure safe usage [

33]. Volatile organic compounds, such as limonene, commonly found in fragrance formulations, undergo chemical reactions with environmental factors, resulting in the formation of formaldehyde, a potent irritant that triggers asthma and rhinitis in susceptible individuals, exacerbating respiratory distress [

34]. The consistent daily exposure to these volatile organic compounds contributes substantially to indoor air pollution, creating respiratory health hazards not only for users but also for others sharing the same environment, thereby amplifying public health concerns [

35]. Fragrances frequently induce allergic contact dermatitis, with specific compounds like cinnamal causing skin irritation and discomfort in approximately 1 to 2% of users, highlighting the allergenic potential of certain fragrance ingredients [

36]. The standardized fragrance mix I, employed in dermatological patch testing, elicits allergic reactions in 10% of patients diagnosed with dermatitis, underscoring the widespread prevalence of fragrance-related skin sensitivities among affected populations [

37]. Sensitive skin, which affects 20 to 30% of adults, exhibits heightened vulnerability to these adverse reactions, often leading to prolonged discomfort and necessitating the use of specially formulated fragrance products to mitigate irritation [

38]. Certain fragrance components, including phthalates and synthetic musks, act as endocrine disruptors, interfering with hormonal balance and potentially causing long-term health consequences across various physiological systems [

39]. Phthalates, in particular, have been directly linked to reproductive toxicity, raising significant concerns about their impact on fertility and developmental health [

40]. Synthetic musks, due to their chemical stability, demonstrate bioaccumulation in both human tissues and environmental ecosystems, posing risks to individual well-being and broader ecological health [

41]. Personalizing fragrance formulations to align precisely with an individual’s skin biology significantly mitigates these health risks by reducing unnecessary exposure to harmful compounds, thereby enhancing user safety and promoting overall well-being [

42].

Environmental and Industrial Microbiology Insights

Environmental microbiology provides critical insights that guide the development of sustainable fragrance design, addressing ecological challenges in production and disposal [

43]. Soil bacteria, such as

Pseudomonas putida, possess enzymatic pathways that efficiently degrade

terpenes, mirroring

Corynebacterium’s metabolism on human skin [

44].

Bacillus subtilis employs

esterase enzymes to metabolize esters, enabling the design of more eco-friendly fragrance components [

45]. Commercial applications such as

Givaudan’s Z-biome™ technology utilize microbial fermentation to synthesize biodegradable volatile organic compounds, reducing the environmental burden of fragrance manufacturing [

46]. Studies in wastewater treatment have shown that

Pseudomonas species can degrade synthetic musks, which supports the formulation of more sustainable fragrance ingredients [

47]. Biodegradable formulations are increasingly recognized for significantly reducing ecological footprints by minimizing persistent chemical waste [

22].

From the existing findings, it is reasonable to extrapolate that the terpene-degrading pathways of Pseudomonas putida may enhance the environmental breakdown of fragrance compounds, supporting more compatible end-of-life degradation in nature. Bacillus subtilis’s esterase activity likely ensures that fragrance esters naturally biodegrade in the environment, promoting long-term ecosystem balance. Microbial fermentation, as applied in commercial platforms, could yield new biodegradable notes that retain olfactory quality while enhancing sustainability. These microbial processes reveal a promising direction for eco-conscious fragrance design—one that balances performance with environmental responsibility and aligns with increasing consumer demand for sustainable and personalized scent experiences.

Barriers to Research

Skin microbiome research has primarily focused on medical applications, including diagnostics and therapeutics for dermatological conditions such as acne and psoriasis, with relatively little attention directed toward cosmetic or fragrance-related investigations [

48]. Analytical study of volatile organic compounds (VOCs), essential to understanding interactions between fragrances and skin microbiota, relies heavily on gas chromatography–mass spectrometry (GC-MS), a high-cost technique requiring specialized infrastructure and trained professionals [

49]. Additionally, the fragrance industry tends to resist acknowledging variability in scent performance, as this challenges the long-standing model of producing universally consistent fragrances [

50].

From the existing findings, it is reasonable to extrapolate that this medical-centric research approach may inadvertently stall progress in developing microbiome-informed fragrance personalization. The prohibitive costs and operational complexity of GC-MS likely restrict broader exploration of individual scent performance, thus slowing innovation in this area. Furthermore, the industry's reluctance to embrace scent variability may prevent meaningful shifts toward personalization. A shift toward interdisciplinary collaboration between microbiologists, analytical chemists, and fragrance manufacturers could help overcome these barriers, unlocking the potential for microbiome-driven fragrance technologies and biologically attuned scent design.

Skin Microbiome Testing

Metagenomic analysis using 16S rRNA sequencing enables accurate identification and profiling of skin-associated microbial taxa, offering detailed insights into bacterial community composition . Studies focused on body odour reveal that microbial testing can pinpoint specific taxa responsible for malodour formation, supporting the understanding of host-microbe-odour interactions. For instance, Corynebacterium species, dominant in moist axillary areas, are associated with production of strong volatile compounds, whereas Cutibacterium species, abundant in sebaceous regions like the neck, contribute different volatile profiles [

16,

25]. The skin microbiome also plays a critical role in health maintenance and immunity, factors which in turn influence odour expression and skin chemistry [

16]. Commercial biotechnology companies now offer consumer-accessible reports detailing individual skin microbiota profiles, though the use of these insights for perfume personalization remains largely exploratory [

46]. Testing remains relatively expensive (approximately

$100–

$200), and further research is needed to validate the predictive value of such data in fragrance-microbiome interactions.

From the existing findings, it is reasonable to extrapolate that metagenomic profiling may evolve into a key tool for advanced fragrance personalization, identifying specific microbial patterns that correlate with better scent performance. Tailoring fragrances to individual microbiota could improve projection, longevity, and user satisfaction, particularly for users who report underperformance with standard perfumes. For example, the sulfur-rich volatiles of Corynebacterium may support deeper, musky scents in axillary regions, while Cutibacterium’s skin chemistry might complement woody or creamy notes like sandalwood, especially on the neck. As the precision of microbial data interpretation improves, customized recommendations could emerge as an effective strategy to match scent chemistry with individual biology. With the available insights from microbiome studies, we can infer meaningful interactions between microbial metabolites and perfume VOCs, and use these insights to enhance current personalization strategies, especially for enthusiasts and individuals experiencing fragrance underperformance. Consumer-oriented reports may empower buyers to choose fragrances optimized for their skin type and microbial signature, paving the way for microbiome-informed olfactory experiences.

Practical Personalization Strategies

Personalization of fragrances significantly improves their performance without requiring advanced microbial testing, offering practical strategies to optimize scent compatibility and user satisfaction, as outlined in

Table 2 [

10]. The lipids present in sebum naturally bind fragrance compounds, substantially extending the longevity of musky notes on dry skin, particularly when enhanced by fatty acid-based moisturizers that reinforce this binding effect [

46]. Oily skin, characterized by elevated

Cutibacterium activity due to its lipid-rich environment, supports the proliferation of skin bacteria, allowing musky scents to maintain stability and persistence without rapid degradation [

18]. Hypoallergenic fragrances, formulated to reduce allergenic potential, effectively minimize the risk of allergic contact dermatitis, making them ideal for individuals with sensitive skin prone to irritation [

36]. The choice of application site critically influences scent expression: wrists, being cooler and drier, optimize the projection of volatile citrus notes; necks, warmer and oilier, enhance the richness of musky scents; and the area behind the ears, with moderate temperature, is well-suited for balanced floral-musk blends, achieving excellent scent diffusion due to optimal warmth [

10,

30].

Corynebacterium-rich armpits produce volatile compounds through robust microbial metabolism, contributing to body odour [

7,

25]. This microbial activity may degrade fragrance aldehydes, suggesting avoidance of aldehyde-based notes in these areas to prevent reduced scent longevity. Cultural preferences, such as the widespread appreciation for oud fragrances in the Middle East, guide fragrance selections to align with regional sensory and aesthetic traditions [

2]. Minimal application of fragrances substantially reduces exposure to volatile organic compounds, mitigating potential health and environmental risks associated with overuse [

6]. Prebiotic moisturizers nurture the skin microbiome, fostering a balanced microbial environment that enhances fragrance performance by supporting optimal skin conditions [

8]. Strategic layering of multiple fragrance notes creates a more enduring and complex olfactory experience, allowing scents to evolve harmoniously over time [

10]. (

Table 1, 180 words)

Health and Sustainability Benefits

Personalizing fragrances substantially reduces exposure to allergens and volatile organic compounds, significantly lowering the risk of allergic contact dermatitis and respiratory conditions such as asthma, thereby enhancing user safety and comfort [

42]. This tailored approach minimizes waste by reducing over-application and product discards, conserving valuable botanical resources essential for fragrance production and promoting environmental stewardship [

22]. Personalization optimizes scent compatibility, enabling consumers to choose well-matched fragrances that satisfy their preferences, thereby reducing purchase frequency, conserving natural resources, and promoting sustainable consumption practices [

2]. Certain fragrance components, such as phthalates and synthetic musks, function as endocrine disruptors, interfering with hormonal regulation and potentially leading to long-term health consequences, including metabolic, reproductive, and developmental disorders across multiple physiological systems [

39,

40]. Personalization aligns fragrance use with wellness principles by ensuring scents complement individual skin biology, while advancing sustainability through eco-conscious consumption practices that mitigate environmental impact [

9].

Integrating Biodegradability, Technology, and Microbiome Insights in Fragrance Innovation

Biodegradable fragrance formulations, designed to decompose naturally, substantially reduce environmental impact by limiting the accumulation of synthetic chemicals in ecosystems [

47]. Digital platforms, including mobile applications, facilitate personalized wellness and beauty experiences, making tailored solutions more accessible to consumers [

9]. Biotechnology partnerships, such as Givaudan’s Z-biome™ initiative, leverage metagenomic technologies to analyse skin microbial compositions for advanced fragrance development [

46]. Educational efforts emphasize the skin microbiome’s influence on wellness and sensory experiences, increasing consumer awareness [

9]. Additionally, fragrance molecules are known to interact with skin chemistry to produce varied olfactory effects, laying the groundwork for biologically optimized scent design [

10].

From these findings, it is reasonable to extrapolate that biodegradable formulations likely enhance sustainability by supporting environmentally safe degradation pathways, contributing to long-term ecological balance. Mobile-based personalization tools may democratize access to microbiome-informed fragrance recommendations, particularly for enthusiasts and individuals experiencing underperformance with standard perfumes. Strategic integration of metagenomics in biotech partnerships could substantially refine fragrance compatibility with an individual's microbial signature, boosting olfactory performance. As education grows around the microbiome's role in sensory experiences, consumer acceptance of microbiome-personalized fragrances is likely to increase. Together, these developments redefine perfumery as a biologically intelligent and eco-conscious discipline.

Conclusions

Fragrance personalization is emerging as a scientifically grounded approach to address the variability in scent performance observed across individuals. By incorporating insights from skin microbiome research, it becomes possible to tailor fragrances to an individual’s biological profile, potentially enhancing olfactory performance, reducing adverse reactions, and aligning with sustainability goals. The skin microbiome, through its enzymatic and metabolic interactions with volatile organic compounds, can play a critical role in modulating the sensory expression of perfumes. Understanding these interactions provides a mechanistic basis for developing more precise and consistent fragrance formulations.

Personalization, long a goal in cosmetics and healthcare, finds a robust scientific foundation in microbiome-based strategies. Integrating metagenomic profiling into fragrance design adds an additional layer of sophistication, allowing for the prediction and modulation of fragrance performance based on microbial diversity and site-specific skin chemistry. Such approaches may be particularly beneficial for individuals who experience poor scent longevity or altered olfactory perception due to microbiome variation.

Advancements in biotechnology, consumer microbiome testing, and computational modelling are likely to facilitate the practical application of these insights. As educational efforts increase public awareness of the biological factors influencing fragrance experience, acceptance of microbiome-guided personalization is expected to grow. Future research should aim to refine the predictive models linking microbial taxa and metabolic pathways to specific fragrance molecule interactions and validate them through controlled human studies.

In summary, microbiome-informed fragrance personalization represents a promising interdisciplinary frontier, combining dermatological science, analytical chemistry, microbial ecology, and perfumery. It holds the potential to redefine how fragrances are developed, selected, and experienced—transitioning from generalized formulations to biologically optimized solutions.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Writing – Original Draft, Writing – Review & Editing: [Dr Abdul Ghafur].

Funding

No funding received.

Ethical Statement

No human or animal studies were conducted; no ethical permission required.

AI Disclosure

AI-assisted tools were used for language polishing, with full author oversight.

Conflicts of Interest

The author is the founder of Fragragenomics Biotech Pvt LTD, a startup focused on microbiome-based fragrance personalization. No other conflicts of interest.

References

- Turin, L., & Sanchez, T. (2006). Perfumes: The Guide. Penguin Books.

- Mintel. (2015). Fragrance trends in the US and EU markets. https://www.mintel.com.

- Steinemann, A. (2016). Fragranced consumer products: Exposures and effects from emissions. Air Quality, Atmosphere & Health, 9, 861–866. [CrossRef]

- Lambers, H., Piessens, S., Bloem, A., Pronk, H., & Finkel, P. (2006). Natural skin surface pH is on average below 5, which is beneficial for its resident flora. International Journal of Cosmetic Science, 28(5), 359–370. [CrossRef]

- Byrd, A. L., Belkaid, Y., & Segre, J. A. (2018). The human skin microbiome. Nature Reviews Microbiology, 16(3), 143–155. [CrossRef]

- Bouslimani, A., et al. (2015). Molecular cartography of the human skin surface. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 112(17), E2120–E2129. [CrossRef]

- Natsch A. What Makes Us Smell: The Biochemistry of Body Odour and the Design of New Deodourant Ingredients. Chimia (Aarau). 2015;69(7-8):414-20. [CrossRef]

- Boxberger, M., Cenizo, V., Cassir, N., & La Scola, B. (2021). Challenges in exploring and manipulating the human skin microbiome. Microbiome, 9(1), 125. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC8166136/.

- McKinsey & Company. (2022). The trends defining the $1.8 trillion global wellness market in 2024. https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/consumer-packaged-goods/our-insights/the-trends-defining-the-1-point-8-trillion-dollar-global-wellness-market-in-2024.

- Sell, C. S. (2014). Chemistry and the Sense of Smell. Wiley. [CrossRef]

- Herz RS. A naturalistic analysis of autobiographical memories triggered by olfactory visual and auditory stimuli. Chem Senses. 2004 Mar;29(3):217-24. [CrossRef]

- Ali SM, Yosipovitch G. Skin pH: from basic science to basic skin care. Acta Derm Venereol. 2013 May;93(3):261-7. [CrossRef]

- Grice, E. A., & Segre, J. A. (2011). The skin microbiome. Nature Reviews Microbiology, 9(4), 244–253. [CrossRef]

- Gallo, R. L. (2017). Human skin is the largest epithelial surface for interaction with microbes. Journal of Investigative Dermatology, 137(6), 1213–1214. [CrossRef]

- Rawlings AV, Matts PJ. Stratum corneum moisturization at the molecular level: an update in relation to the dry skin cycle. J Invest Dermatol. 2005 Jun;124(6):1099-110. [CrossRef]

- Egert, M., Simmering, R., & Riedel, C. U. (2017). The association of the skin microbiota with health, immunity, and disease. Clinical Pharmacology & Therapeutics, 102(1), 62–69. [CrossRef]

- Bouslimani, A., et al. (2015). Lifestyle chemistries from phones for individual profiling. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 112(17), E2120–E2129. [CrossRef]

- Grice, E. A., et al. (2009). Topographical and temporal diversity of the human skin microbiome. Science, 324(5931), 1190–1192. [CrossRef]

- James, A. G., et al. (2013). Microbiological and biochemical origins of human axillary odour. FEMS Microbiology Ecology, 83(3), 527–540. [CrossRef]

- Natsch, A., et al. (2003). A specific bacterial aminoacylase cleaves odourant precursors secreted in the human axilla. Journal of Biological Chemistry, 278(8), 5718–5727. [CrossRef]

- Steinemann, A. C. (2017). Health and societal effects from exposure to fragranced consumer products. Preventive Medicine Reports, 5, 45–47. [CrossRef]

- Rim, K. T., & Lim, C. H. (2014). Biologically hazardous agents at work and efforts to protect workers’ health. Safety and Health at Work, 5(2), 43–52. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC4147232/.

- McGinley, K. J., et al. (1978). Regional variations in density of cutaneous propionibacteria. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 35(1), 62–66. [CrossRef]

- Natsch A, Emter R. The specific biochemistry of human axilla odour formation viewed in an evolutionary context. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2020 Jun 8;375(1800):20190269. [CrossRef]

- Callewaert, C., et al. (2014). Microbial odour profile of polyester and cotton clothes after a fitness session. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 80(21), 6611–6619. [CrossRef]

- Fredrich, E., Barzantny, H., Brune, I., & Tauch, A. (2013). Daily battle against body odour: Towards the activity of the axillary microbiota. Trends in Microbiology, 21(6), 305–312. [CrossRef]

- Curtis, T., & Williams, D. G. (2001). Introduction to Perfumery. Micelle Press.

- Lam TH, Verzotto D, Brahma P, Ng AHQ, Hu P, Schnell D, Tiesman J, Kong R, Ton TMU, Li J, Ong M, Lu Y, Swaile D, Liu P, Liu J, Nagarajan N. Understanding the microbial basis of body odour in pre-pubescent children and teenagers. Microbiome. 2018 Nov 29;6(1):213. [CrossRef]

- Bawdon, D., et al. (2015). Identification of axillary Staphylococcus as producers of malodour. Journal of Investigative Dermatology, 135(10), 2366–2374. [CrossRef]

- Sell, C. S. (2006). The Chemistry of Fragrances. Royal Society of Chemistry.

- Parodi, A., et al. (2010). Hormonal influences on skin odour. Journal of Cosmetic Dermatology, 9(2), 104–108. [CrossRef]

- Misery, L., et al. (2011). Sensitive skin in Europe. Journal of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology, 25(2), 145–151. [CrossRef]

- Buckley DA, Rycroft RJ, White IR, McFadden JP. The frequency of fragrance allergy in patch-tested patients increases with their age. Br J Dermatol. 2003 Nov;149(5):986-9. [CrossRef]

- Nazaroff, W. W., & Weschler, C. J. (2004). Cleaning products and air fresheners: Exposure to primary and secondary air pollutants. Atmospheric Environment, 38(18), 2841–2865. [CrossRef]

- Steinemann, A. C., et al. (2011). Chemical emissions from residential dryer vents during use of fragranced laundry products. Air Quality, Atmosphere & Health, 4(1), 151–156. [CrossRef]

- de Groot, A. C., & Schmidt, E. (2016). Essential oils: Contact allergy and chemical composition. Contact Dermatitis, 74(5), 265–281. [CrossRef]

- Uter, W., et al. (2010). The European baseline series in 10 European countries. Contact Dermatitis, 63(5), 259–267. [CrossRef]

- Farage, M. A. (2019). The prevalence of sensitive skin. Frontiers in Medicine, 6, 98. [CrossRef]

- Dodson, R. E., et al. (2012). Endocrine disruptors and asthma-associated chemicals in consumer products. Environmental Health Perspectives, 120(7), 935–943. [CrossRef]

- Hauser, R., & Calafat, A. M. (2005). Phthalates and human health. Occupational and Environmental Medicine, 62(11), 806–818. [CrossRef]

- Luckenbach, T., & Epel, D. (2005). Nitromusk and polycyclic musk compounds as long-term inhibitors of cellular xenobiotic defense systems. Environmental Health Perspectives, 113(1), 17–24. [CrossRef]

- Basketter, D. A., et al. (2010). Application of a weight of evidence approach to assessing discordant sensitization datasets. Regulatory Toxicology and Pharmacology, 57(1), 90–96. [CrossRef]

- Peck AM. Analytical methods for the determination of persistent ingredients of personal care products in environmental matrices. Anal Bioanal Chem. 2006 Oct;386(4):907-39. [CrossRef]

- Marmulla R, Harder J. Microbial monoterpene transformations-a review. Front Microbiol. 2014 Jul 15;5:346. [CrossRef]

- Krings U, Berger RG. Biotechnological production of flavours and fragrances. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 1998 Jan;49(1):1-8. [CrossRef]

- Givaudan. (2023). Z-biome™: Biotechnology for sustainable fragrance ingredients. https://www.givaudan.com.

- Simonich SL, Federle TW, Eckhoff WS, Rottiers A, Webb S, Sabaliunas D, de Wolf W. Removal of fragrance materials during U.S. and European wastewater treatment. Environ Sci Technol. 2002 Jul 1;36(13):2839-47. [CrossRef]

- Grice EA. The skin microbiome: potential for novel diagnostic and therapeutic approaches to cutaneous disease. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2014 Jun;33(2):98-103. [CrossRef]

- Lubes G, Goodarzi M. Analysis of Volatile Compounds by Advanced Analytical Techniques and Multivariate Chemometrics. Chem Rev. 2017 May 10;117(9):6399-6422. [CrossRef]

- Gilbert, A. N. (2008). What the Nose Knows. Crown Publishers.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).