1. Introduction

Recently, the number of matches and competitions in professional football has increased [

1]. During particularly busy periods, football teams might participate in as many as 60 competitive matches in a season, averaging 5 to 6 matches each month and up to 3 matches per week [

2]. Notably, physical demands (e.g., accelerations, decelerations, high-speed distance, sprint distance and total distance) and technical-tactical exigencies (e.g., number of passes, crosses and shots on target) of match play have also increased [

3]. Thus, training workload has also increased to response to competition requirements. Consequently, optimal recovery strategies turn into a crucial intervention, to prevent long-term fatigue, underperformance or injury [

4]. Furthermore, recovery is viewed as a diverse physiological and psychological restorative process that is related to time [

5].

Recovery is defined as the full set of processes that leads to an athlete’s renewed capacity in order to meet or exceed a preceding performance [

6]. Further, the recovery period is also explained as the time necessary for physiological and psychological parameters, which were affected by exercise, to return to resting values [

5,

6].

Physiologically, exercise imposes stress on athletes, disrupting the homeostasis of various processes such as cardiocirculatory, metabolic, neuromuscular, and central systems, as well as biochemical pathways. In response to this stress, the body initiates adaptive mechanisms post-exercise to counterbalance these changes, highlighting the importance of an adequate recovery period following training [

7].

Recovery practices are designed to enable athletes to resume training and performing more quickly [

5]. Every athlete focus on restoring pre-performance capacities as quickly as possible [

8]. However, many coaches count on their past experiences to implement strategies [

9], not following evidence-based recommendations [

10]. Subjective perception of the football players impacted differently their rate of recovery methods [

11], recognized effectiveness is also impacted by players feelings [

12]. Additionally, athlete’s convictions and their attended behaviors toward recovery are disconnected [

13]. Nonetheless, multiple strategies have been validated [

14]. A recent systematic review with graded recommendations mentioned that sleep, nutrition, cold water immersion, active recovery and massage were the most commonly used strategies in professional football [

1]. Even though, many post-exercise recovery methods exist. It’s admitted that, generally, football players are using them [

15].

To the authors’ knowledge, only 4 studies were conducted exclusively with elite football teams [

15,

16,

17,

18]. Mainly, studies performed in elite football have proven that recovery methods are very important to mitigate fatigue and improve recovery [

15,

16,

17].

The present study aimed to determine post-exercise recovery strategies employed by football teams in Morocco. In addition, we analyzed the frequency of their uses after competition’s games and after training sessions. Also, we studied time of recovery strategies’ use, and if more strategies are used the same time. Therefore, we analyzed the cooperation of multidisciplinary team to conduct recovery process, and the bases taken into consideration to implement the strategies. Individualization of recovery strategies were investigated too. At the last, we analyzed the availability of economics means that can allowed recovery strategies practice.

2. Materials and Methods

Participants

The study involved 32 Moroccan football teams from the “Botola Pro D1” and “Botola Pro D2” leagues during the 2023-2024 season. Participants included technical or medical staff members, contacted through personal networks or official team channels.

Design and Procedure

The study utilized an online ad-hoc questionnaire to evaluate the use of post-exercise recovery strategies among these teams. The survey, based on prior studies [

15,

19,

20], included various question formats and was validated by external practitioners before being distributed online. Data collection spanned from November 27, 2023, to March 31, 2024, with completion taking approximately 15 minutes.

The survey comprised 12 sections, covering team demographics, recovery strategies employed, and their frequency, as well as the individuals responsible for implementing these strategies. Recovery strategies were categorized into natural, nutritional, physical, psychological, and alternative/complementary methods.

Statistical Analysis

The study design was observational and cross-sectional, with data analyzed using Google Forms® and Microsoft® Excel, determining frequencies and measures of central tendency and dispersion. Qualitative terms were used to describe the magnitude of observed frequencies, such as “all,” “most,” and “majority.”

3. Results

Twenty-nine out of thirty-two surveyed football teams, including all teams from Botola Pro D1 and 81% from Botola Pro D2, participated in the study. Botola Pro D1 teams comprised 31 ± 2 players, playing 1.25 ± 0.45 matches weekly and training 6.56 ± 1.15 sessions per week, averaging 88 ± 13.73 minutes per session. Botola Pro D2 teams had 31 ± 4 players, playing one match per week and training 5 ± 0.82 sessions weekly, averaging 90 ± 17.32 minutes per session.

Most teams employed recovery strategies, with only one team not implementing any.

Teams implemented different recovery strategies (

Table 1); Cold therapy, stretching, and massage were the most common strategies (over 85%), followed by active recovery (71%), diet (54%), and supplements (50%). Fewer teams used sleep (32%), heat therapy (29%), medication (21%), and alternative strategies (18%). Strategies like the Mézières method and electrostimulation were also noted.

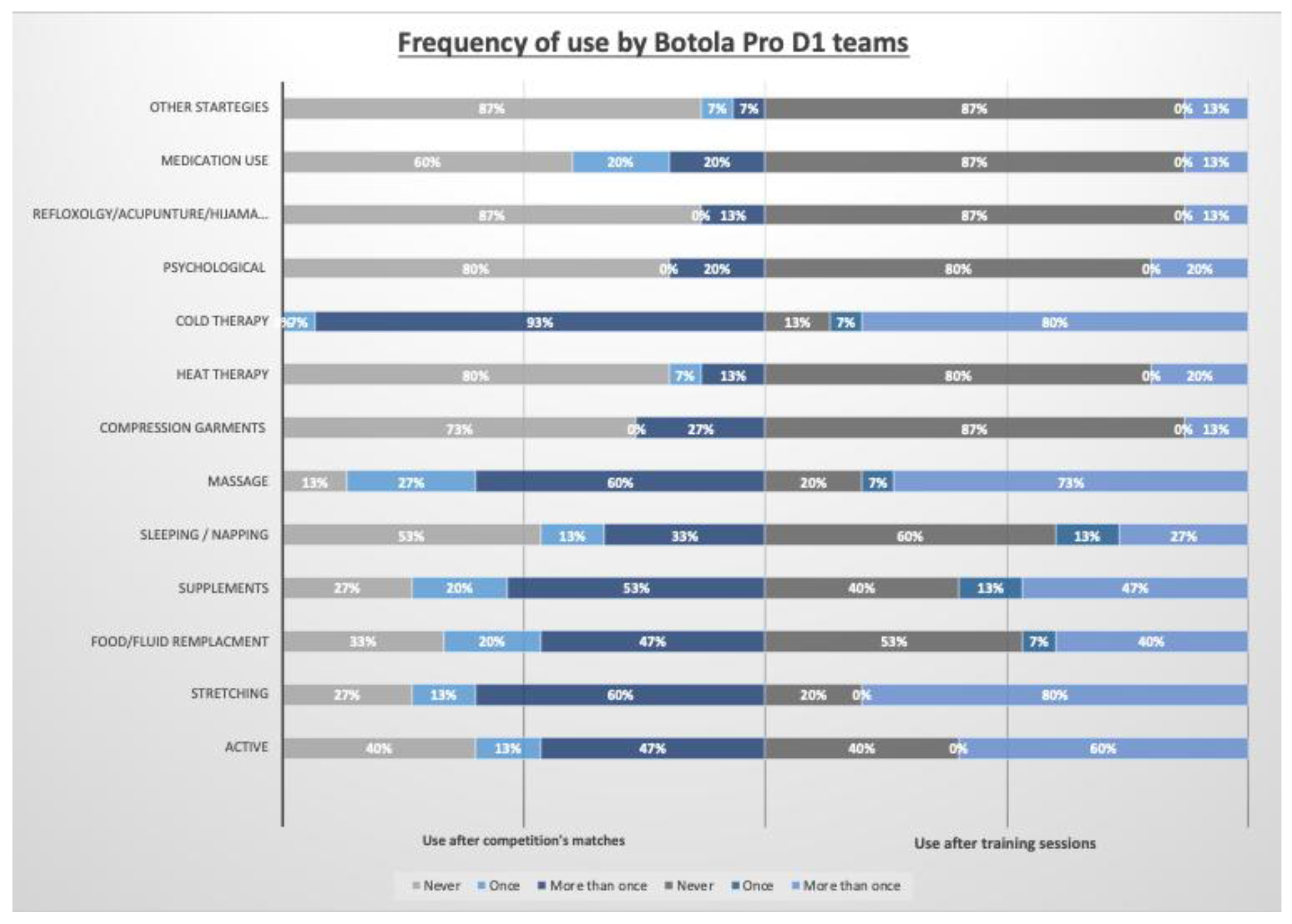

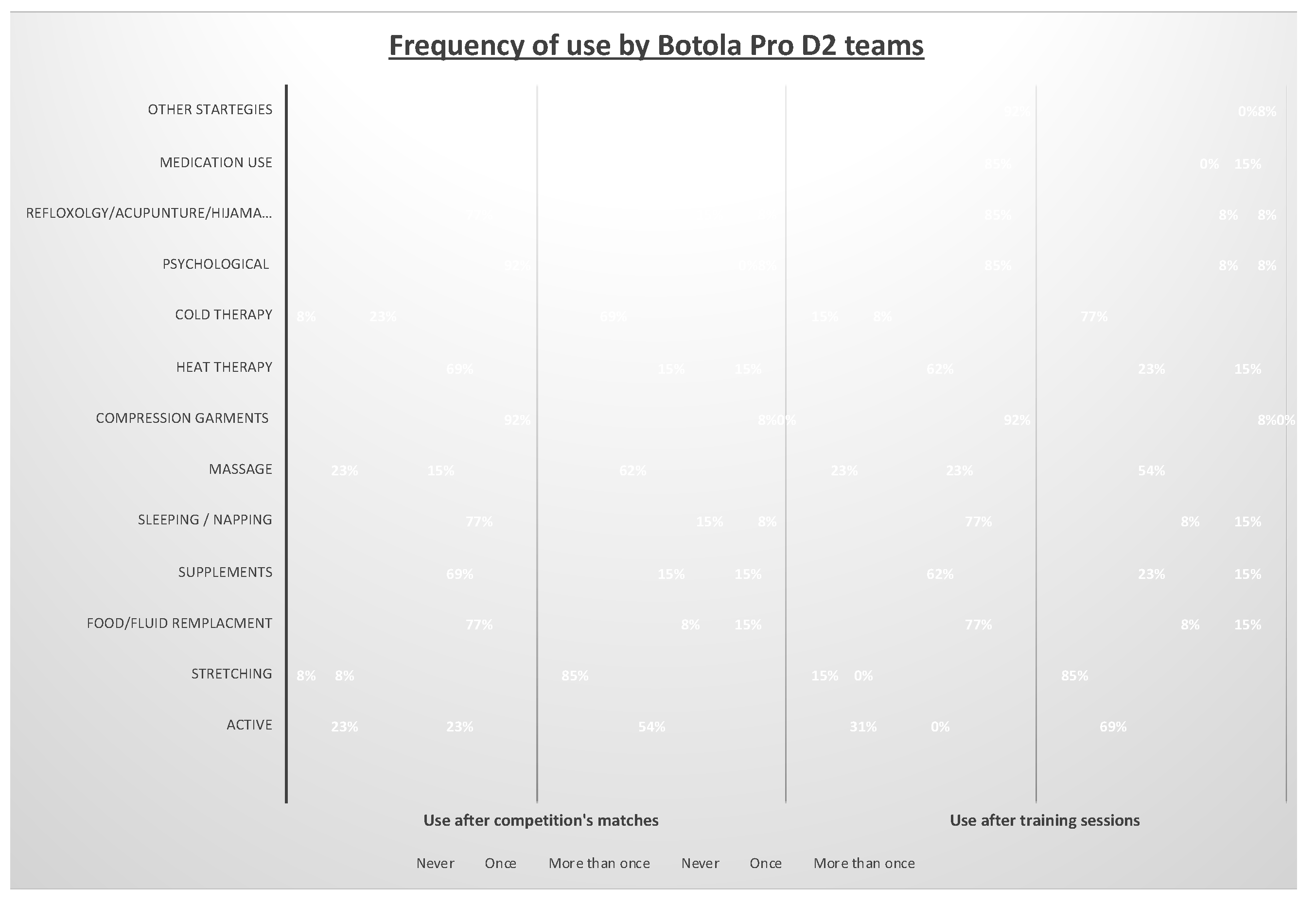

The frequency of use after competition and after training session, for either Botola Pro D1 and Botola Pro D2, are outlined in

Figure 1 and

Figure 2, respectively.

Time of first application, combination of different approaches, individualization, supervision of recovery process and availability of economics means are summarized in (

Table 2).

Most teams (64%) applied recovery strategies immediately post-exercise, with 61% following a specific order and 61% tailoring strategies to individuals. Recovery methods were usually developed by medical and technical staff. A majority (93%) based guidelines on scientific research, while 86% had adequate resources for recovery protocols. Only 14% lacked resources, and 4% based guidelines on available resources.

4. Discussion

Our findings demonstrate that cold therapy, stretching, massage, active recovery, nutritional strategies (supplements and food/fluid replacement), sleep, heat therapy, pharmaceutical drug, compression garment, psychological, alternative strategies, The Mézières method and electrostimulation were commonly used by Moroccan football teams as post-exercise recovery strategies.

Natural Strategies

Despite not necessitating equipment or financial investment, only 54% of the teams implemented natural recovery strategies. Stretching and active recovery were favored by most teams, whereas the incorporation of sleep and napping did not appear to be common practices among Moroccan teams.

Our findings indicate that stretching is among the most commonly employed methods by Moroccan football teams (89%). This approach is likely the preferred option for athletes at all levels given its accessibility and the ability for athletes to engage in stretching exercises collectively as a team [

9]. This finding aligns with earlier studies [

15,

16,

21,

22].

Although widely included into recovery protocols, stretching’s efficacy remains poorly comprehended [

23].

Eventually, the widespread utilization of stretching by athletes at various levels of competition can be explained by a variety of factors. These include its self-administered nature, simplicity, widespread acceptance, equipment-free requirement, adaptability to limited space, and longstanding endorsement as a post-exercise recovery method in mainstream literature and research for many years.

Typically, active recovery methods involve engaging in low-intensity aerobic exercises that target the entire body, such as running, cycling, or swimming. This method employed by the majority of Moroccan football teams (71%), is commonly utilized by athletes globally [

15,

16,

17].

Active recovery outperformed passive recovery in terms of lactate removal and increasing the perspective recovery [

24].

Surprisingly, Most of the Moroccan football teams did not indicate utilizing sleep/napping as a recovery strategy after exercise. The utilization rates for sleep and napping were reported at 32% and 21% respectively among the teams. These results diverge from existing literature, which typically shows widespread adoption of sleep practices among athletes and football teams [

9,

11,

15,

16,

17].

Strategies related to sleep seem to have minimal impact on enhancing recovery in terms of physical, physiological, and perceptual aspects [

1]. Nevertheless, extending sleep duration can positively influence cognitive function and various aspects of well-being [

25], decrease fatigue levels [

26]. Furthermore, a nap protocols had a beneficial impact on muscle soreness (DOMS), sleepiness, rating of perceived exertion (RPE), and physical performance [

27,

28].

Nutritional Strategies

Although nutrition plays a crucial part in aiding athletic recovery and enhancing performance, only 52% of Moroccan football teams incorporated nutritional strategies. Among these, 50% focused on food and fluid replacement, while 54% utilized supplementation.

Food/fluid replenishment is viewed as a crucial means of recovery, widely utilized to a significant extent [

1,

9,

15,

16,

17,

18]. Furthermore, a well-structured nutritional plan is likely to help professionals in replenishing glycogen stores, speeding up muscle repair, and improving hydration [

29].

Dietary supplements are widely used among athletes [

15,

30]. In football, nutritional strategies frequently incorporate dietary supplements to assist players in improving their performance and recovery [

31],

Physical Strategies

The majority of the teams (57%) utilized physical approaches. The study underscores the widespread use of cold therapy and massage as common recovery methods following matches and training sessions.

Cold therapy, a widely utilized strategy for recovery among football players [

15,

17,

18,

32] is one of the most commonly employed methods by Moroccan football teams (96%).

Due to its widespread utilization, This approach was shown to be successful in aiding recovery.

CWI demonstrated advantages in reducing delayed onset muscle soreness DOMS [

33], reducing perceived pain levels and perceived fatigue [

33,

34].

Another frequently used recovery strategy was massage, with 86% of the teams adopting this method. This observation is consistent with findings from earlier research [

15,

16,

17,

22,

35]

Yet, there remains a scarcity of research on the effectiveness of massage in facilitating performance restoration and recovery enhancement.

The utilization of heat therapy was quite low, with only eight teams (29%) adhering to it. A discovery that is consistent with other results [

15]. The use of local heating is more frequently applied in rehabilitation settings to address musculoskeletal injuries or to shield muscles from potential damage [

36].

Compression garments are rapidly becoming a popular recovery technique in sports [

37]. Our results indicate that the use of compression garments (CG) by Moroccan teams is considerably lower, with only five teams (18%) utilizing them, than other studies [

15,

16,

17]. Nevertheless, CG had a significant and positive impact on DOMS and perceived fatigue [

33]. However, any significant changes in the recovery phase of DOMS were observed [

38].

Psychological Strategies

Although matches are known to cause significant mental and physical fatigue, only 18% of the teams employed psychological strategies. Some of the psychological techniques utilized included mental imagery, progressive muscle relaxation, breathing techniques, music, prayer. etc., [

39,

40]. Some teams predominantly employed progressive muscle relaxation techniques [

15], whereas imagery was more commonly utilized by other players [

39].

The evaluation of potential mental recovery strategies indicates that they seem to positively impact mental states, including concentration, attention, and vigilance [

40]. However, there is limited knowledge regarding the application of mental recovery strategies in sports and their beneficial effects [

41].

Alternative/Complementary Strategies

Despite the popularity of alternative medicine [

42], just 18% of the teams utilized acupuncture or reflexology as part of their recovery strategy. However, medications were also used by a minority (8 teams; 29%). [

15,

39]. Urroz et al. demonstrated that acupuncture did not enhance physiological recovery following intense exercise [

43]. Nevertheless, significant improvements in blood lactic acid levels, maximum heart rate (HR max), and VO2max was observed due to acupuncture therapy [

44].

5. Conclusions

To our knowledge, this study is the first to examine the use of post-exercise recovery strategies by male football teams in Morocco.

We concluded that physical approaches were more employed than natural, nutritional, complementary, or psychological ones. This finding could be attributed to the accessibility of these strategies, the subjective perceptions of players and coaches or the impact of media and social network.

In addition, the most frequently employed strategies after matches are the same as those used after training sessions by all teams, regardless of the game or training conditions.

Moreover, the personnel in charge of implementing recovery strategies within their team should actively engage with scientific research to deliver evidence-based practices aimed at optimizing player recovery, overall health and well-being, and performance.

The survey results differ from previous research. Therefore, future studies might consider investigating the specific details of each method’s use (such as intensity and duration), which are important for understanding the scheduling of recovery techniques. Additionally, examining the discrepancies between theoretical approaches and practical application in professional football could provide valuable insights.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.A., A.C., B.Z., A.E. and M.B.; methodology, E.A., B.Z. and M.B.; software, E.A.; validation, B.Z., A.E. and M.B.; formal analysis, E.A.; investigation, E.A.; resources, E.A.; data curation, E.A.; writing—original draft preparation, E.A.; writing—review and editing, A.E. and M.B.; visualization, M.B.; supervision, A.E. and M.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.”

Funding

This study received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

All the details about the study were provided at the beginning of the questionnaire. Participants were invited to participate voluntarily and were given the option to withdraw at any time. Their rights were preserved according to the Law 28-13, of August 4, 2015, relating to the protection of persons participating in biomedical research.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all participants and their legal guardians prior to any data collection as part of the protocol procedures.

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to extend their heartfelt thanks to all the participants in this study. They are particularly grateful to all the teams that took part in the survey and especially to the medical and technical staff of the teams who dedicated their time to complete the questionnaire.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors state that they don’t have any conflicting interests related to the results of this study.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| CWI |

Cold Water Immersion |

| D1 |

1st Division |

| D2 |

2nd Division |

| DOMS |

Delayed Onset Muscle Soreness |

| HR |

Heart Rate |

| RPE |

Rating Perceived Exertion |

| VO2max |

maximal oxygen uptake |

References

- S. M. Querido, R. Radaelli, J. Brito, J. R. Vaz, and S. R. Freitas, ‘Analysis of Recovery Methods’ Efficacy Applied up to 72 Hours Postmatch in Professional Football: A Systematic Review With Graded Recommendations’, Int J Sports Physiol Perform, vol. 17, no. 9, pp. 1326–1342. 2022. [CrossRef]

- L. Anderson et al., ‘Quantification of training load during one-, two-and three-game week schedules in professional soccer players from the English Premier League: implications for carbohydrate periodisation’, J Sports Sci, vol. 34, no. 13, pp. 1250–1259, 2016.

- E. Pons et al., ‘A longitudinal exploration of match running performance during a football match in the Spanish La Liga: a four-season study’, Int J Environ Res Public Health, vol. 18, no. 3, p. 1133, 2021.

- A.Altarriba-Bartes, J. Peña, J. Vicens-Bordas, R. Milà-Villaroel, and J. Calleja-González, ‘Post-competition recovery strategies in elite male soccer players. Effects on performance: A systematic review and meta-analysis’, Oct. 01, 2020, Public Library of Science. [CrossRef]

- M. Kellmann et al., ‘Recovery and performance in sport: Consensus statement’, Int J Sports Physiol Perform, vol. 13, no. 2, pp. 240–245. 2018. [CrossRef]

- C. Hausswirth and I. Mujika, Recovery for Performance in Sport, Human Kinetics. 2013.

- S. Skorski, I. Mujika, L. Bosquet, R. Meeusen, A. J. Coutts, and T. Meyer, ‘The temporal relationship between exercise, recovery processes, and changes in performance’, Int J Sports Physiol Perform, vol. 14, no. 8, pp. 1015–1021. 2019. [CrossRef]

- N. Terrados, J. Mielgo-Ayuso, A. Delextrat, S. M. Ostojic, and J. Calleja-Gonzalez, ‘Dietetic-nutritional, physical and physiological recovery methods post-competition in team sports.’, J Sports Med Phys Fitness, vol. 59, no. 3, pp. 415–428, 2018.

- F. Crowther, R. Sealey, M. Crowe, A. Edwards, and S. Halson, ‘Team sport athletes’ perceptions and use of recovery strategies: A mixed-methods survey study’, 2017, BioMed Central Ltd. [CrossRef]

- D. V Van Wyk and M. I. Lambert, ‘Recovery strategies implemented by sport support staff of elite rugby players in South Africa’, South African journal of physiotherapy, vol. 65, no. 1, pp. 41–46, 2009.

- M. Nédélec, S. Halson, B. Delecroix, A. E. Abaidia, S. Ahmaidi, and G. Dupont, ‘Sleep Hygiene and Recovery Strategies in Elite Soccer Players’, Nov. 01, 2015, Springer International Publishing. [CrossRef]

- M. Simjanovic, S. Hooper, M. Leveritt, M. Kellmann, and S. Rynne, ‘The use and perceived effectiveness of recovery modalities and monitoring techniques in elite sport’, J Sci Med Sport, vol. 12, p. S22, 2009.

- A.Murray, A. Turner, J. Sproule, and M. Cardinale, ‘Practices & attitudes towards recovery in elite Asian & UK adolescent athletes’, Physical Therapy in Sport, vol. 25, pp. 25–33, 2017.

- F. Crowther, R. Sealey, M. Crowe, A. Edwards, and S. Halson, ‘Influence of recovery strategies upon performance and perceptions following fatiguing exercise: a randomized controlled trial’, BMC Sports Sci Med Rehabil, vol. 9, pp. 1–9, 2017.

- A.Altarriba-Bartes, J. Peña, J. Vicens-Bordas, M. Casals, X. Peirau, and J. Calleja-González, ‘The use of recovery strategies by Spanish first division soccer teams: a cross-sectional survey’, Physician and Sports medicine, vol. 49, no. 3, pp. 297–307. 2021. [CrossRef]

- S. M. Querido, J. Brito, P. Figueiredo, F. Carnide, J. R. Vaz, and S. R. Freitas, ‘Postmatch Recovery Practices Carried Out in Professional Football: A Survey of 56 Portuguese Professional Football Teams’, Int J Sports Physiol Perform, vol. 17, no. 5, pp. 748–754. 2022. [CrossRef]

- A. Field et al., ‘The Use of Recovery Strategies in Professional Soccer: A Worldwide Survey’, Int J Sports Physiol Perform, vol. 16, no. 12, pp. 1804–1815. 2021. [CrossRef]

- M. Nédélec, A. McCall, C. Carling, F. Legall, S. Berthoin, and G. Dupont, ‘Recovery in soccer: Part II-recovery strategies’, Jan. 2013. [CrossRef]

- L. Rappelt, S. Javanmardi, L. Heinke, C. Baumgart, and J. Freiwald, ‘The multifaceted nature of recovery after exercise: A need for individualization’, Dec. 01, 2023, Elsevier GmbH. [CrossRef]

- M. Kellmann, Enhancing recovery: Preventing underperformance in athletes. Human Kinetics, 2002.

- R. Braun-Trocchio et al., ‘Recovery strategies in endurance athletes’, J Funct Morphol Kinesiol, vol. 7, no. 1, p. 22, 2022.

- M. Pernigoni, D. Conte, J. Calleja-González, G. Boccia, M. Romagnoli, and D. Ferioli, ‘The Application of Recovery Strategies in Basketball: A Worldwide Survey’, Front Physiol, vol. 13, no. 2022. [CrossRef]

- B. Van Hooren and J. M. Peake, ‘Do We Need a Cool-Down After Exercise? A Narrative Review of the Psychophysiological Effects and the Effects on Performance, Injuries and the Long-Term Adaptive Response’, Sports Medicine, vol. 48, no. 7, pp. 1575–1595. 2018. [CrossRef]

- İ. Özsu, B. Gurol, and C. Kurt, ‘Comparison of the Effect of Passive and Active Recovery, and Self-Myofascial Release Exercises on Lactate Removal and Total Quality of Recovery’, J Educ Train Stud, vol. 6, no. 9a, p. 33, Aug. 2018. [CrossRef]

- C. Leduc et al., ‘The effect of acute sleep extension vs active recovery on post exercise recovery kinetics in rugby union players’, PLoS One, vol. 17, no. 8 August, Aug. 2022. [CrossRef]

- E. Van Ryswyk et al., ‘A novel sleep optimisation programme to improve athletes’ well-being and performance’, Eur J Sport Sci, vol. 17, no. 2, pp. 144–151, 2017.

- Boukhris; et al. , ‘Performance, muscle damage, and inflammatory responses to repeated high-intensity exercise following a 40-min nap’, Research in Sports Medicine An International Journal, vol. 31, Oct. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- H. Hsouna et al., ‘A daytime 40-min nap opportunity after a simulated late evening soccer match reduces the perception of fatigue and improves 5-m shuttle run performance’, Research in Sports Medicine, vol. 30, no. 5, pp.502–515. 2022. [CrossRef]

- M. K. Ranchordas, J. T. Dawson, and M. Russell, ‘Practical nutritional recovery strategies for elite soccer players when limited time separates repeated matches’, Sep. 12, 2017, BioMed Central Ltd. [CrossRef]

- R. Abreu, C. B. Oliveira, J. A. Costa, J. Brito, and V. H. Teixeira, ‘Effects of dietary supplements on athletic performance in elite soccer players: a systematic review’, 2023, Taylor and Francis Ltd. [CrossRef]

- J. Collins et al., ‘UEFA expert group statement on nutrition in elite football. Current evidence to inform practical recommendations and guide future research’, Br J Sports Med, vol. 55, no. 8, p. 416, Apr. 2021. [CrossRef]

- R. Cross, J. R. Cross, J. Siegler, P. Marshall, and R. Lovell, ‘Scheduling of training and recovery during the in-season weekly micro-cycle: Insights from team sport practitioners’, Eur J Sport Sci, vol. 19, no. 10, pp. 1287–1296, Nov. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dupuy, W. Douzi, D. Theurot, L. Bosquet, and B. Dugué, ‘An evidence-based approach for choosing post-exercise recovery techniques to reduce markers of muscle damage, Soreness, fatigue, and inflammation: A systematic review with meta-analysis’, Front Physiol, vol. 9, no. APR, Apr. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- T. R. Higgins, D. A. Greene, and M. K. Baker, ‘Effects of Cold Water Immersion and Contrast Water Therapy for Recovery From Team Sport: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis’, The Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research, vol. 31, no. 5, 2017, [Online]. Available: https://journals.lww.com/nscajscr/

fulltext/2017/05000/effects_of_cold_water_immersion_and_contrast_water.32.aspx.

- E. Bezuglov et al., ‘The prevalence of use of various post-exercise recovery methods after training among elite endurance athletes’, Int J Environ Res Public Health, vol. 18, no. 21, Nov. 2021. [CrossRef]

- P. Rodrigues, G. S. Trajano, L. Wharton, and G. M. Minett, ‘Effects of passive heating intervention on muscle hypertrophy and neuromuscular function: A preliminary systematic review with meta-analysis’, J Therm Biol, vol. 93, p. 102684, 2020.

- E. Rey, A. Padrón-Cabo, R. Barcala-Furelos, D. Casamichana, and V. Romo-Pérez, ‘Practical active and passive recovery strategies for soccer players’, Strength Cond J, vol. 40, no. 3, pp. 45–57, 2018.

- X. Valle et al., ‘Compression garments to prevent delayed onset muscle soreness in soccer players’, Muscles Ligaments Tendons J, vol. 3, no. 4, p. 295, 2013.

- R. R. Venter, J. R. Potgieter, and J. G. Barnard, ‘The use of recovery modalities by elite South african team athletes’, pp. 133–145, 2009, [Online]. Available: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/230582966.

- F. Loch, A. Ferrauti, T. Meyer, M. Pfeiffer, and M. Kellmann, ‘Resting the mind – A novel topic with scarce insights. Considering potential mental recovery strategies for short rest periods in sports’, Jun. 01, 2019, Elsevier B.V. [CrossRef]

- B. Rattray, C. Argus, K. Martin, J. Northey, and M. Driller, ‘Is it time to turn our attention toward central mechanisms for post-exertional recovery strategies and performance?’, Front Physiol, vol. 6, p. 122191, 2015.

- M. M. Cohen, S. Penman, M. Pirotta, and C. Da Costa, ‘The integration of complementary therapies in Australian general practice: results of a national survey’, Journal of Alternative & Complementary Medicine: Research on Paradigm, Practice, and Policy, vol. 11, no. 6, pp. 995–1004, 2005.

- P. Urroz, B. Colagiuri, C. A. Smith, A. Yeung, and B. S. Cheema, ‘Effect of acupuncture and instruction on physiological recovery from maximal exercise: A balanced-placebo controlled trial’, BMC Complement Altern Med, vol. 16, no. 1, Jul. 2016. [CrossRef]

- Z.-P. Lin et al., ‘Effects of Acupuncture Stimulation on Recovery Ability of Male Elite Basketball Athletes’, 2009. [Online]. Available: www.worldscientific.com.

- E. Rey, A. Padró N-Cabo, R. Barcala-Furelos, D. Casamichana, and V. Romo-Pé Rez, ‘Practical Active and Passive Recovery Strategies for Soccer Players’, Jun. 2018. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).